1. Introduction—Biographical Sketch

Marcelina Darowska, née Kotowicz

1 (1827–1911), was a figure whose activities in support of women can be compared to the contributions of Stanisław Konarski

2 in the field of work for men (

Rokoszny 1928, p. 31). She created a coherent, thoroughly original educational system in the period following the January Uprising (1863–1864), when Polish society was subject to strong denationalisation efforts and was largely deprived of its moral elites. Darowska founded the Congregation of the Sisters of the Immaculate Conception of the Blessed Virgin Mary, whose mission was to serve Poland by working to rebuild the family. At that time, the family was the core of Polish identity and preserved the national identity. Darowska believed that the renewal of society could only take place through the revitalisation of the family, and, in her opinion, this could be achieved through the education of women, which is why the pedagogical concept she created serves the comprehensive development of women. Marcelina opened convent schools and took care of the education of both the sisters (most of whom were teachers) and the girls entrusted to their care. She also paid attention to the ideological continuity of her work, seeking, on the one hand, to preserve the immutability of the core of the concept, while on the other hand, remaining open to new scientific achievements (

Anuncjata 2010, pp. 89–90). In this context, she summarised her pedagogical considerations and also allowed her fellow sisters to record their own comments and advice. In this way, four fundamental sources were created that outlined her educational system: “Statute on Science and Education”, “Pedagogy”, “Four Retreat Talks”, and “Letters”.

3It should be emphasised that Marcelina, who had no professional training in the field of education, created an educational system based on Christian personalism “supported only by her self-developed pedagogical talent” (

Jabłońska-Deptuła 1996, p. 32).

Christian personalism treats the human being as a quiddity of supreme importance. The existence of each person has a deep, individual meaning, but in relation to the other(s) and to God. The representatives of this current (John Paul II, Jacques Maritain, and Emmanuel Mounier) emphasise the dignity and autonomy of each person, like Darowska, who sees the value of the human being as the result of fraternity with Jesus Christ. Her concept is therefore not only rooted in a personalistic view of humanity but is also an expression of Christian humanism (

Doyle 2011;

Fransen 2024).

The development of Darowska’s pedagogical concept was influenced by several important factors:

Her family background. Marcelina was born the fifth of seven children of Jan Kotowicz and Maksymilia Jastrzębska, in a family of landowners, and grew up in that environment. At that time, the rich landed gentry formed an enclave of Polishness—one that was destroyed by the partitioning powers in all areas of public life. However, family ties were a guarantee for the survival of national identity. Moreover, as a young woman, Marcelina acquired administrative skills by helping her father manage the estate and became sensitised to the social problems of the village. At home, she developed her organisational skills as well as a sense of responsibility for the country.

The historical context in which she lived. On the one hand, Romanticism: freedom movements, the belief in the mission of nations, the appreciation of the role of women in the work of social renewal. A woman was entrusted with a special mission. She not only bore the burden of running the home and bringing up children, but also had responsibility for people in the broader community. On the other hand, the idea of caring for people was influenced by positivism with an emphasis on working at the grassroots level. Many women from landed gentry families secretly taught the Polish language, founded orphanages, and organised household courses.

Natural motherhood. Before founding the Congregation, Mother Marcelina married Kazimierz Weryha-Darowski, with whom she had two children. After a short time, her husband died of typhoid fever. Soon afterwards Marcelina buried her son Józef and was left alone with her daughter Karolina. Her experience of natural motherhood was an important factor in shaping the spirituality of the Congregation and her understanding of the role of marriage and the greatness of motherhood. It also caused a frequent split between fidelity to her vocation and her duties as a mother.

Patriotism. Marcelina writes in her autobiography: “From childhood, I loved my country above all else; this feeling was the predominant one in me” (

Sołtan 1982, p. 9). As a girl, she prayed to God that she would be useful to her country, and she was. Pope Pius IX confirmed that the Congregation she founded was “for Poland” (

Jabłońska-Deptuła 1993, p. 83). and that one of its main tasks was the Christian education of women.

Religious experiences, including reading the letters of St Paul with commentaries by St Thomas Aquinas. The year 1854 was a turning point in Marcelina’s spiritual life. Two Polish priests—Aleksander Jełowiecki and Hieronim Kajsiewicz—entered her life and played an important role in her biography. They created an intellectual world that differed from the one she had known until then and exerted a great influence on Darowska. It is safe to say that Marcelina’s work was part of the great programme of social renewal designed by Bogdan Jański

4. It was a time of mystical experiences, which, according to Chmielewski—an expert in this field—became the direct source of both the form of Marcelina Darowska’s spiritual life and the structure of the work she created (

Chmielewski 2024).

2. Review of Literature

2.1. Marcelina Darowska’s Pedagogical Concept and Approach to Education in Her Time

Although Mother Marcelina Darowska worked at the intersection of three socio-cultural epochs, there are elements in her pedagogical system that fundamentally contradict the prevailing ideas of her time.

Naturalism, which was important during the Romantic era, coincided with the first part of Darowska’s life. This movement was based on respect for the nature of the child and encouraged the development of their innate resources. These assumptions are also close to Marcelina’s concept, though they differ from her views concerning the role of the teacher and thus the student. The romantic concept of education emphasises the tasks of the educator in connection with the protection of the child—to support but not hinder the natural development process of a young person, to nourish but not disturb it.

Marcelina Darowska clearly emphasises that it is not enough to merely protect a child from evil; rather, the child must be consistently encouraged through sensible discipline: “But remember that without regulations for reason and will, for nature, there can be no order. Dissoluteness in education is terrible, immoral, deadly (...). The consequence of this: lack of labour, lack of obedience, refusal of duty, domination of nature” (

Anuncjata 2010, p. 36). Darowska’s understanding of discipline differs completely from the view that most of her contemporaries had of this category, but comes quite close to Maria Montessori’s view (

Bhat 2021;

Saha and Adhikari 2023). Both wanted to educate independent people and perceived self-discipline as the path to the goal of human happiness in their holistic education (teaching and upbringing). In their opinion, people are able to achieve this through freedom. For Montessori and Darowska, as well as for other Christian pedagogues, e.g., Jan Bosko (

Stańkowski 2025), a person is free when his actions are guided by a balance of will, reason and emotion (“heart”). Although these three categories are innate in every human being, they must also be developed and trained, initially with the support of the educator, and later independently by the person with the help of self-discipline.

The understanding of the nature of a human being in Christian pedagogy is clearly different from the romantic notion of a person’s good inclinations. Darowska treats a person with respect, which for her is linked to the truth about a human being. She perceives the resources but also the limitations of the student, which is why the main feature of her concept is to categorise the educator’s activities into three basic tasks:

Education of the will;

Education of the heart;

Education of the mind.

The greatest emphasis in this conception falls on the first of the above-mentioned: the will. She wrote: “This is what human is, what his(her) will is (…) We must pay special, most careful, most focused attention to it” (

Anuncjata 2010, p. 31). Darowska was characterised by her ability to make demands, but also to maintain moderation in this area, which is clearly expressed in her words to educators: “Don’t demand too much so that you don’t get too little. Set the necessary rules, but stick strictly to them” (

Anuncjata 2010, p. 34). Darowska recognises the role of principles and rules in education, but recommends that educators should be guided by the love that leads to understanding. Marcelina considers the introduction to the conscientious fulfilment of duties to be the best method of educating the human will and describes duties as “railings on the path of life” (

Grażyna 1997, p. 15), emphasising their function of providing direction to action and protecting against deviating from the right path.

The second human disposition that Darowska recommended educating is the “heart”. It is important to remember that psychology was only just emerging when she developed her pedagogical concept (it had previously been a branch of philosophy)

5. Many years were to pass before the first results of scientific research reached Poland. Nevertheless, Marcelina demonstrated a remarkable understanding of human dispositions. She recognised the importance of the emotional sphere for human functioning, referring to this area as the “heart”. This was not a foreign approach in Poland during Marcelina’s time; similar views can be found in the work of Jan Władysław Dawid, who described the same disposition as the “soul” of a person—i.e., his psyche, not just the mental components of his personality (

Dawid 1927).

In Marcelina Darowska’s reflections on emotional skills, balance is paramount: “Strive to ensure that your will is always in harmony with your heart, recognised by the reason,” she says. The mother therefore does not diminish the importance of affectivity; in a letter to one of the teaching sister, she writes: “Do not neglect the heart” (

Anuncjata 2010, p. 55). However, she pays particular attention to proper upbringing, and even to the “taming” of this sphere. Thus, she writes to one of her sisters: “Let us love the children, but in God’s way, by hardening and educating them, not coddling and belittling them” (

Anuncjata 2010, p. 59).

The education of the emotional sphere should lead to a comprehensive development of the human being, but also to self-discipline that results not only in the absence of evil, but also in the active pursuit of doing good: “But that is not enough: we must work on ourselves so that we do not let evil into our hearts ... to bring into it all that is good and noble. And good deeds will then necessarily follow” (

Anuncjata 2010, p. 55). For Marcelina, then, action is a practical effect, a proof of the labour of the heart, and the root cause of such action is love. Darowska’s definition of love is very different from the one we find in the literature and art of Romanticism. For her, love is a decision of reason that is strengthened by the will; however, this does not mean that she underestimates the involvement of the “heart”, i.e., the emotional sphere of the human being. Darowska explains her point of view as follows: “Love is happiness. In moments of consolation, it radiates outwards with joy; in times of trial, it holds with faith and will and gives serenity” (

Darowska 1997, p. 71).

The intellectual sphere is another area that Darowska describes as a human competence that she recommends developing, though, again, not to the full extent prescribed by the spirit of the epoch during the second part of her life. The main differences lie not so much in the content of education—since, like the Positivists, Marcelina advocated a comprehensive education on the one hand and a pragmatic education on the other (

Taylor and Medina 2013;

Lutz 2009;

Peca 2000). Like the leading representatives of that epoch, Darowska focused her teaching on proven facts and not imaginary ideas: “Teach children to think, to think logically, by basing their conclusions and judgements not on hypotheses but on recognised truths, on established experiments” (

Anuncjata 2010, p. 75).

The greatest discrepancies between Positivist ideas and Marcelina Darowska’s concept relate to the aims of education. While she sought to raise the dignity of every person and to improve his condition, she also saw his original destiny and ultimate goal: “God is our end, the beginning and the end” (

Darowska 1997, p. 11). In the Positivists’ assumptions, education is anthropocentric. It should serve the elevation of human—his development and well-being are the ultimate goal of all action, especially educational activities. The basis of a Positivist education was biologism and utilitarianism; the basis of Darowska’s teaching was Christian humanism.

It seems that, for Marcelina, the mind of human being is a kind of buckle that holds together the other components of his personality. Perhaps this is why the rule “Teach the children to think” (

Grażyna 1997, p. 15) concludes and in a way summarises the set of assumptions of Darowska’s educational system.

2.2. The Person of the Pupil in Marcelina Darowska’s Four Basic Pedagogical Assumptions

In 1872, Darowska presented her pedagogical concept in a concise and synthetic form and summarised it in four pedagogical principles. The first of them simultaneously points to the main goal of the teacher’s actions and even of human life in general: “God to all, through all to God” (

Grażyna 1997, p. 14). It is worth mentioning that this rule was proclaimed by Marcelina to all groups that she felt responsible for both the sisters and the teachers, the parents and, the children and young people—the pupils of the sisters’ schools.

So, who is the student in light of this rule? This is best expressed in Darowska’s own words to the graduates: “You are God’s. God has created you—with the blood of his Son he has redeemed you—he has predestined you for himself for eternity” (

Darowska 1997, p. 11). This does not mean that people are lost somewhere in this concept, that their dignity is forgotten. Marcelina understands this dignity precisely in relation to the person of God: in Him she sees both the origin and the destiny of man. According to Darowska, human life, i.e., each individual biography, is a different, individual path of a disciple towards the Creator.

Marcelina derives individualisation as the most important educational principle from this rule: “Every person has his own individuality, his own character, his own abilities, his own type (...) the thought of God is reflected in him, and he is strictly oriented towards the destiny and task that this thought has given him...” (

Anuncjata 2010, p. 120); however, this perception of the individual, which separates him from the collective, does not elevate him above God.

The idea of individualisation in pedagogy emerged at the turn of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries with the birth of progressivism and the concept of “new education”. However, as already mentioned, Marcelina’s views—although attentive to the discoveries of the time in the field of human psychology—emerged from her for completely different reasons. Darowska’s motivation was to lead her pupils to a relationship with God in an individualised way, one that did justice to each child, taking into account their predispositions and even their life history.

Individualisation, according to the principles of “new education”, emphasises needs, not obligations, promoting activity based on creativity and self-motivation. Its aim is to educate an independent person. Darowska also wants to raise a person who thinks critically, but simultaneously takes responsibility—for others as well. It can therefore be said that individualisation, in the context of working with the student, is a pedagogical method for Marcelina, whereas for the progressives, it serves more as the actual goal of education.

The second principle, “God created us Poles” (

Grażyna 2007, p. 13), shows how important patriotism was for Darowska, which she understood as a task. She wrote to her former students: “It is not just about your personal well-being and happiness, but about you in relation to society: so that you are not a zero in it, not parasites, but co-workers” (

Darowska 1997, p. 16). The author of these words draws attention to the obligation to actively take responsibility for the country.

Marcelina Darowska’s views could give the impression of national megalomania. However, her own words are an indication of how her principle of patriotism should be interpreted: “and everywhere we will educate in the spirit and character of their nation. Polish women should be brought up to be Polish, German women to be German and French women to be French” (

Grażyna 1997, p. 27). This idea, written nearly 150 years ago, still seems relevant in light of the migration processes and multiculturalism of today’s nations.

Patriotism is not the only component associated with responsibility in Darowska’s concept. The third educational principle, “Loyalty to the duties of one’s own state, one’s own place” (

Grażyna 2007, p. 13) surprisingly points to the connection between responsibility and independent thinking: “Awaken a sense of duty in the child: love, respect for it. Awaken a love of work—insight into its necessity, perseverance in it, accuracy, order and deliberation—search for usefulness in it” (

Anuncjata 2010, p. 32). The sentence quoted above fully reflects the mother’s educational plan—the meaning and purpose of duty must also be understood by the pupil in order to fulfil this task conscientiously and, amazingly, even to love it. Both order as well as thinking are important, so there is no room for mindless obedience to orders, which is all the more evident in the fourth, already mentioned crowning rule: “Teach the children to think” (

Grażyna 2007, p. 13). The intention of the Congregation founder is to educate women who think independently, who are partners to their husbands, who consciously shape their own lives and who are also able to educate future generations, which Darowska sees as an important task for women. Marcelina placed importance on students’ ability to think logically and to use this ability in everyday life. For this reason, her schools teach the structure of specific topics, avoiding the method of merely transferring and memorising material. A similar approach can be found, for example, in the teachings of Polish pedagogues such as Kazimierz Sośnicki (structuralism) or Bogdan Suchodolski (problem-complex concept); however, these theories on the selection of educational content appeared in Polish pedagogy almost a century later.

To summarise, Marcelina Darowska’s pedagogy is founded on the integration of the teaching and upbringing process with the aim of forming a responsible, independent thinker. Graduates of the schools run by the sisters should be shaped by faith and its practical application. Students are prepared to be patriots, which is connected with the conscientious fulfilment of duties, including professional and parental ones, in the future. Above all, Darowska wants her students to be happy people, and she is convinced that this happiness comes from a life of faith and the love that is its result, which is expressed in service to others.

2.3. The Role of the Teacher in Marcelina Darowska’s Pedagogical Concept

Marcelina Darowska was aware of how difficult the task of education is, hence the numerous letters left by her to educate future generations of teachers at her schools. She calls education “a labour of love” (

Grażyna 1997, p. 93) and points out that this is the main task of the Congregation she founded.

For Marcelina, the teacher is the second most important educator after the parents, which is why she places special demands on their attitude to life: “It would need examples that speak (...) So let us live according to our theory ourselves” (

Anuncjata 2010, p. 93). First and foremost, she writes about being self-demanding: “We have to demand a lot from ourselves—less from others” (

Anuncjata 2010, p. 97). Moreover, the educator’s personal contact with God is particularly important to her, because: “You don’t have enough God in yourself, and therefore you can’t give him enough (...) to the others” (

Anuncjata 2010, p. 96). We can therefore say that there is a certain triangle of influences in Marcelina’s views: God—educator—student, and this mutual relationship is to be built on the foundation of truth. Darowska speaks of the existence of three “shades”: “The truth with God is faith. Truth with yourself is humility. Truth with others is honesty” (

Grażyna 2007, p. 15). These dispositions are required of both the teacher and the student, but it is the educator who is responsible for moulding this attitude in the pupil. How can the educator fulfil this task? The answer can be found in the first of the four educational guidelines written down by Darowska, which is called the rule of truth and trust (

Grażyna 1997, p. 16). According to her own addition, this principle is realised thanks to the family spirit cultivated within the sisters’ educational institutions. Like a boomerang, Marcelina’s desire to teach her children to think returns, because only through such reflection, she assumes, will they be able to properly evaluate themselves and their relationships with others—including, or above all, their relationship with God. Trust is created through mutual relationships, whereby Darowska demands that the educator also maintains a necessary distance from the students. It is therefore important that the teacher does not appropriate the child in terms of their personal affiliation with God.

As already mentioned, Marcelina Darowska’s individualisation in education is based on the awareness of the unique dignity and identity of each person. For this reason, the dominance of individualisation and long-thinking (

Grażyna 1997, p. 16) appears in her writings as a further indication of the demands placed on the teacher. An individualised approach to each student allows the child to feel the teacher’s care, creating a friendly bond between them, thereby fostering trust. Nevertheless, the feelings and needs of both (and especially the pupil, due to the age-related incomplete maturity of their emotional sphere) are variable, which can lead to difficulties and misunderstandings. Marcelina recommends “long-thinking” in children’s education, which is more than just patience. This far-sighted approach to the pupil—from the point of view of preparation for a righteous life, understood as a useful, active and honest existence—also takes into account the salvation of the student.

All these actions must be performed selflessly by the teacher (the dominant element of purity of intention and selflessness): “It is necessary that the children regard us as their best friends and rely on us as such. And so it will be if they never see in us the slightest hint of personal interest, but only one thing: concern for their well-being” (

Grażyna 1997, p. 22). For Darowska, experience—both professional and personal (motherhood)—is a source of insight into the fact that a young person carefully observes others and learns their attitudes and behaviours, often through imitation. While this reflection may inspire gratitude towards the teacher, it should not be the goal of the educator’s work. Similar observations can be found in old Polish texts on pedagogical topics (e.g.,

Dawid (

1927),

Rowid (

1937),

Kwiatkowska (

2005)). Yet, nowadays, the issue of selflessness in teaching is less frequently addressed in pedagogical literature.

The primacy of upbringing over educating is not a popular trend in 21st-century pedagogy either. In Marcelina’s conception, this principle concludes her list of requirements for the teacher’s pedagogical activity (the dominant element of upbringing in the teaching process) (

Grażyna 2007, p. 20). While she certainly demanded the reliable transmission of knowledge and the cultivation of independent thinking, she emphasised the importance of education: “We educate children not to teach them history, music, etc., but to develop in them eternal life and at the same time to give them a spiritual education (...)” (

Grażyna 2007, p. 20). She further clarifies: “Education ... not only from the intellectual and external side, but above all from the moral side” (

Anuncjata 2010, p. 18).

This position stands in contrast to the anti-pedagogical currents of the 20th century, which view education as an oppressive act and the teaching of norms and values as an attack on the freedom of the pupil. Nevertheless, Darowska’s concept does not seem to completely negate the idea of anti-authoritarian pedagogy, whose Polish representative was Janusz Korczak. The mother advises the sisters to explain the rules to their children, to individualise interactions and to negate coercion in education: “Show us [Poles] the beautiful, the good and leave us freedom—and we will fly towards it, we will jump into the fire for it; if we are forced, we will freeze in resistance” (

Anuncjata 2010, p. 133).

Marcelina valued the freedom of the pupils, yet she considered education to be the main task of teachers because it leads to responsibility, which in turn leads to rational freedom. Darowska, with her far-sighted view of humanity and deep patriotism, was convinced that a human being (and especially a woman) is educated in order to mould future generations. She believed that entire societies can be built and even restored in this way.

3. Materials and Methods

The aim of the study described in this article is to explore and compare the opinions of participants about Marcelina Darowska’s pedagogical concept. The high school graduates and this year’s leavers of the schools run by the Congregation of the Sisters of the Immaculate Conception of the Blessed Virgin Mary not only expressed their views, but also their own knowledge and level of satisfaction in this area. They also had the opportunity to express their opinion on the contemporary relevance of Darowska’s pedagogical system.

The research conducted provided answers to the following research questions:

How do school leavers and graduates assess their own knowledge of Marcelina Darowska’s pedagogical concept?

What role do the teacher and the student play in the sisters’ schools according to the participants?

How do participants assess the validity of Darowska’s pedagogical concept and the consistency between the approach to students in the analysed schools and Darowska’s concept?

The survey method was used in the study because it is suitable for collecting information, understanding opinions and attitudes, and describing the characteristics of a particular group (

Ali et al. 2022). The questionnaire to be completed online contained 6 choice questions, 4 of which contained a scale, and two open-ended questions.

The respondents (n = 67) were selected using the purposive sampling method based on specific criteria relevant to the research questions. We needed the students’ opinion in order to obtain an objective assessment of the validity and consistency of the Darowska’s concept and the teachers’ approach to the students at the Sisters’ schools. The educators employed in the mentioned institutions were not a suitable research group because they could give declarative answers on the topic.

The participants were divided into two groups in order to recognise and compare the opinions of respondents who are currently involved in the educational process and those who evaluate it from a certain time perspective. The first group of 31 students in their final year of three high schools belonging to the Congregation of the Sisters of the Immaculate Conception of the Blessed Virgin Mary:

Our Lady of Czestochowa Private High School in Szymanów;

Technical School of Hotel and Catering Industry in Nowy Sącz;

Blessed Marcelina Darowska Private High School in Wałbrzych.

The second group of respondents (n = 36) are graduates of the same schools belonging to the Jazłowiecki Collegiate Association (KZJ). The respondents were selected in the belief that a comparison of the opinions of current students and graduates of sisters’ schools would reveal the coherence and purposefulness (or lack thereof) of Marcelina Darowska’s teaching with the necessary objectivity. In addition, it would allow us to show whether and how the participants’ beliefs differ according to age and thus life experience.

The survey was conducted in January 2023. The data were analysed using mixed methods. The collected material was subjected to quantitative analysis (scaling questions, response options) and qualitative interpretation of the data (open-ended questions) in order to deepen the understanding of the topic under study.

Descriptive statistics (namely percentages) were employed to describe the frequency of responses to the closed-ended survey questions, and that coding of data was used to identify key words/themes for the open-ended survey questions.

4. Results

The pedagogical concept of Marcelina Darowska serves as the basis and reference for the educational work in the sisters’ schools. In a way, this statement can be seen as the basic hypothesis of the research described in this article. Accordingly, the aim is to determine whether the students and graduates confirm this assumption, especially with regard to the roles of the teacher and the pupil in these schools. An additional aim was to assess whether the concept examined is (generally) perceived by the respondents as relevant and applicable today.

The analysis of the collected data began with addressing the following question: how did the participants assess their own knowledge of Marcelina Darowska’s didactic and pedagogical programme? This question was closely related to the subsequent inquiry, which is why the potentially declarative nature of the answers received does not undermine the objectivity of the results obtained.

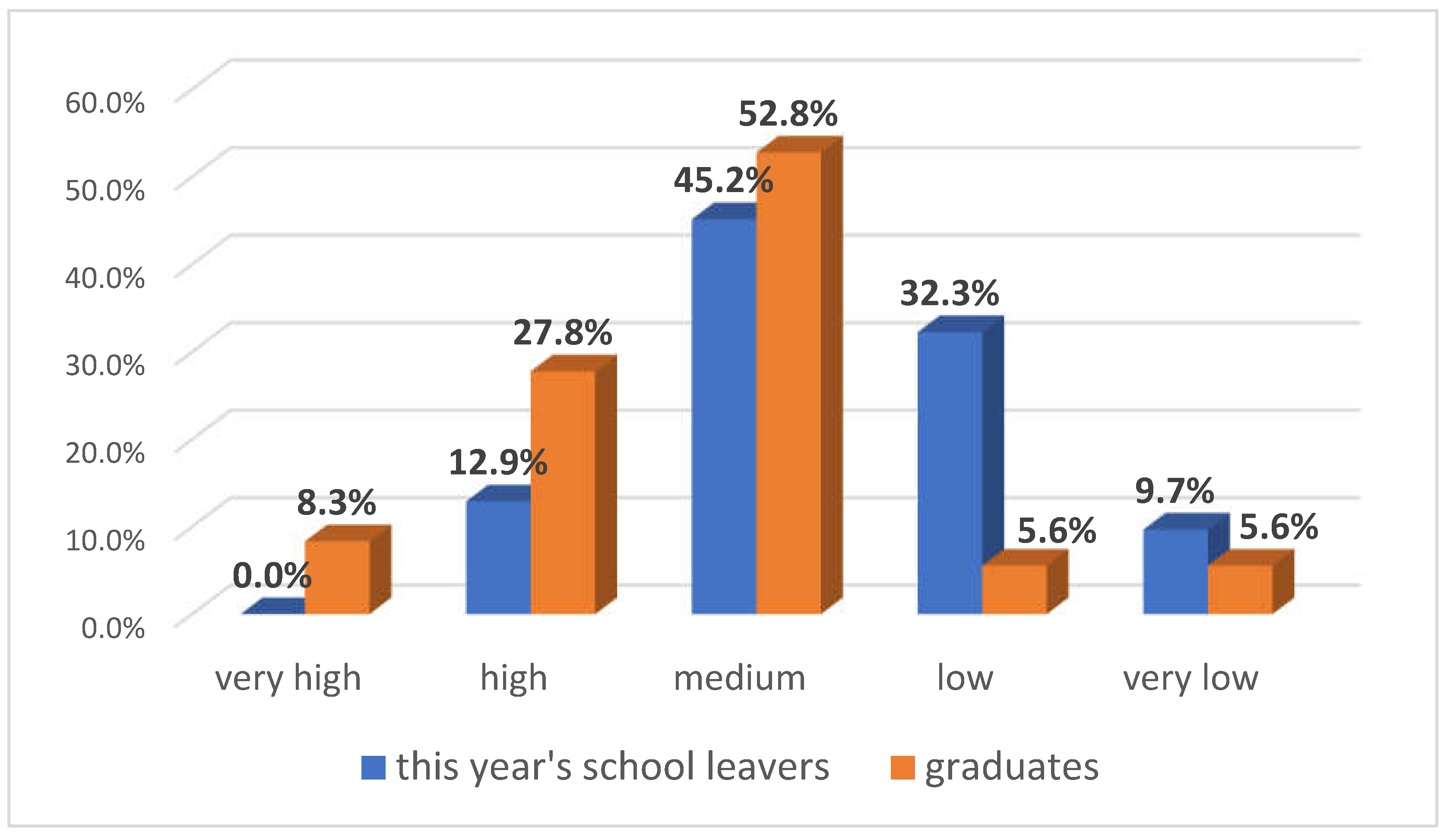

It is difficult to predict the extent to which this question reflects the tendency of participants to choose middle-scale options when rating (central tendency bias); nevertheless, responses such as “high” and “low” show a clear diversity of views (

Figure 1). Female graduates were more likely to rate their own knowledge of the pedagogical concept positively (the difference is 8.3% for “very good” and 14.9% for “good” knowledge).

This observation is further supported by the results in the “low” category, where a substantial difference of 26.7% emerges—it is this year’s high school leavers who, in their own opinion, assess their own knowledge of Darowska’s educational background lower. What could be the reason for this? The sisters’ schools offer a good level of education, and many parents choose these institutions for their children in the expectation of high educational results. This may lead to similar demands being placed on the students themselves, who focus their efforts on cognitive development and attach much less importance to the pedagogical approach they apply in the course of their own education. Moreover, Marcelina Darowska’s views are largely a system of educational principles, and students under the sisters’ care are in the phase of adolescence, where rules must first be subverted before they can be internalised or rejected (

Gerrig et al. 2012).

The next step in the research described was to ask respondents about their level of satisfaction with their own knowledge of the topic analysed in this article.

As

Table 1 shows, a significant percentage of all participants believe that they possess sufficient knowledge of Marcelina Darowska’s pedagogical concept. It should be noted that this group may include both individuals who highly appraise their knowledge in the described area and respondents who underestimate their knowledge. We can learn more about the motivation to broaden knowledge about Darowska and her educational programme by analysing the second column of

Table 1. Interest in further education on this topic is similar among both groups of respondents (the difference is only 7.1%); so, about 32.8% of all respondents would like to expand their familiarity with this concept. One graduate’s comment, categorised under “Other”, can help explain the motivation for continuous improvement in the described subject area: “I remembered some important thoughts from school, especially the climate of support for the development of strong femininity—I recall them regularly and repeat them often. Marcelina was a feminist in the good sense of the word”. From the statements of this participant, it can be concluded that what interests her most about Darowska’s views are the aspects that emphasise the empowerment of women.

The motivation to broaden one’s knowledge of Darowska’s concept can also stem from the desire—and even the habit—of self-education acquired in her schools. One of her students notes: “A teacher (in the sisters’ school—author’s note) was a guide who motivated, encouraged us to acquire and expand our own knowledge”.

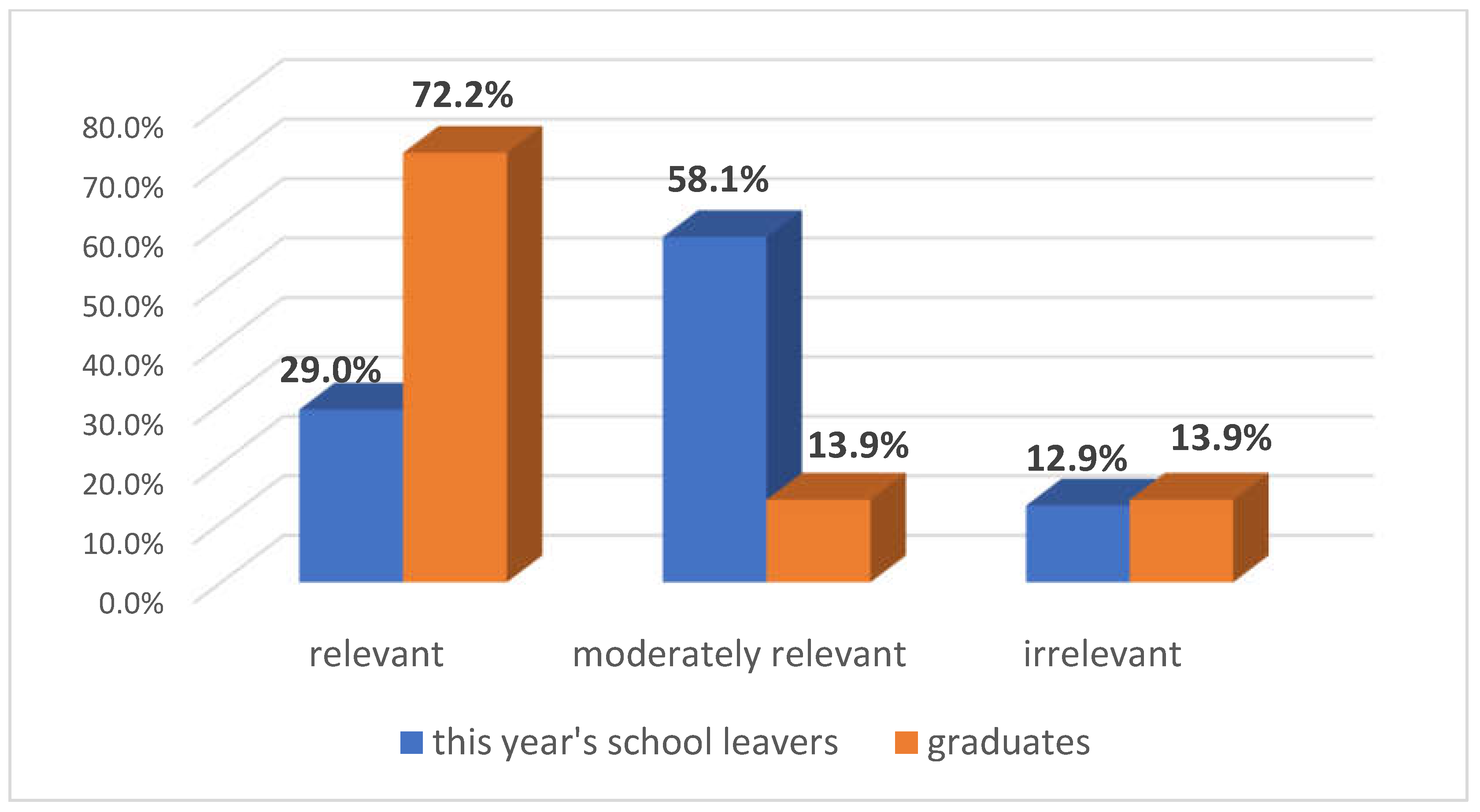

Despite the slightly unclear differences in the areas described above, as shown in

Figure 2, the issue of the relevance of Darowska’s educational assumptions divides the respondents considerably.

For the graduates, the content taught by Darowska is much more relevant than for this year’s school leavers (

Figure 2). It seems that current students at the sisters’ schools tend to evaluate the relevance of Darowska’s concept in close connection with their chosen educational institution. However, it appears that it is the former students who generally estimate her conception more highly. It can be concluded that evaluations made from a distance are much more positive (although there are also two negative opinions in this group about both the concept and its validity and practical implementation) than evaluations given by the current students. Presumably, the life experience of graduates allows them to recognise the usefulness of Marcelina Darowska’s teaching. It seems (and this is also confirmed by the opinions of the participants) that interest in the programme of the foundress of the Congregation grows after students complete their training due to their own newfound needs; for example, from seeking inspiration for the education of their own children. However, it can be assumed that for much younger women—who are living in times of digitalisation and breaking taboos, with diverse and even antinomic understandings of freedom—Darowska’s teachings are simply less attractive.

The answers to the next question relate to the theme addressed in the previous topics and to some extent help to further explain the decisions made earlier. The subject of this analysis was the roles of the teacher and the student in the schools founded by Marcelina Darowska.

As can be seen from the list above (

Table 2), the teacher was most frequently associated with the transmission of knowledge and education in general. In many of the statements, respondents referred to the high standard of teaching. Respondents were also very positive about the methods and the approach itself, as well as the choice of educational content. They also pointed out that they were introduced to self-education: “The teacher was a guide who motivated and encouraged us to acquire and expand our knowledge on our own”. A high level of teaching and appropriate requirements in this area are important elements of Darowska’s educational programme.

One participant’s opinion about the quality of education in the sisters’ schools differs from the others. When addressing this specific question, she speaks negatively about the educational level of the school, while in an earlier answer, she stated that teaching—in the sense of imparting knowledge—was the only advantage of the institution she attended. On the one hand, this could be interpreted as, a lack of consistency on the part of the respondent throughout the assessment, but on the other hand, it could also be a comparative judgement in relation to other, even more negative aspects of the school.

The participants also spoke about the involvement of teachers not only in education, but also in the upbringing and life of the students in general. However, upbringing was rated negatively by the aforementioned graduate, who referred to experiences of coercion in interactions with students. The other respondents viewed the teacher as a mentor and a friend, although high demands were placed on them. This is confirmed by one respondent’s statement: “The teacher was a kind, caring, supportive and trustworthy educator in everything, almost like a parent”.

Respondents’ answers often referred to teachers in other (mainly public) schools, and this is where an interesting observation emerged. Respondents felt that the teaching sisters were more committed than the few lay teachers in their schools. They concluded that the latter did not differ much from educators employed in regular, public institutions.

When discussing the roles of the teacher and the student in the pedagogical practice of Darowska’s schools, the personal commitment of the teaching sisters is undoubtedly at the forefront. This seems to align with Marcelina’s concept, as mentioned in the theoretical part of this text, in which she recognises the primacy of the upbringing process over teaching.

Table 3 also contains other elements of key importance in Marcelina Darowska’s system, such as patriotism and faith, about which one of the graduates wrote: “(A student—author’s note) should be religious, a patriot without blinkers, intelligent (...) and willing to help.” This participant’s statement not only underlines the attachment to the country that she learned at school, but also the ability to make independent judgments and live out the values taught.

An interesting observation concerns two key words: “community” and “child” or “daughter”. The former was used exclusively by students in the context of belonging to a unique community. Graduates, on the other hand, emphasised that they felt at home in the school and boarding schools of the sisters and compared the care they received from them to parental care. The “family spirit” recommended by Darowska was thus confirmed by the respondents; however, it appeared more frequently in the statements of graduates rather than current students. An insightful explanation for this can be found in a former pupil’s statement about the school: “I was a rebellious snot and only after years did I understand how much the fact that I was brought by sisters gave me for the future”.

A few individual statements (n = 2) concerned the overprotection or excessive control by the sisters as teachers. One of these was formulated by a present student, while the other came from a graduate whose negative opinion has already been quoted.

The last part of the study addresses the extent to which teaching practices in the sisters’ high schools align with Marcelina Darowska’s pedagogical concept.

As shown in

Figure 3, this year’s school leavers most frequently chose “ high” and “medium” ratings, while graduates most frequently chose “very high” and “high”. In general, it can be concluded that the adherence of the teachers’ approach to the ideas proclaimed by the founder of the Congregation of the sisters was rated highly. A total of 14 present students and 20 graduates chose the two highest rating options, accounting for 50% of all choices, and the “medium” rating was chosen by 14 respondents (another 20% of respondents). The weighted average calculations for both groups of respondents confirm that graduates tend to rate the alignment more highly (7.73 compared to 5.86 for present students), reflecting a similar pattern of differences observed in previous questions.

The “I have no opinion” category also appears to play a significant role—it was slightly more prevalent among current students, who also rated their knowledge of the concept under discussion lower. A more limited amount of information in relation to the topic described may have an impact on a lower assessment of its value, although other influences can also be found. Graduates attended the sisters’ institutions even up to 50 years earlier than current students, meaning that their needs and requirements were different. Their teachers may also have had a slightly different set of values and work ethics, as research in this area confirms (

Toker Gökçe 2021;

Mustafa and Shafeeq 2019). Regardless of the educators’ status represented (lay or clerical), the overall generational difference is undoubtedly related to differing lifestyles and thus the way in which an individual—in this case a teacher—was brought up and has lived.

5. Discussion and Limitations

The analysis of the research material obtained revealed differences between the evaluations of graduates and current students at high schools run by the Congregation of the Sisters of the Immaculate Conception of the Blessed Virgin Mary. Graduates rated their own knowledge of Darowska’s pedagogical concept and the relevance of Marcelina Darowska’s teaching. The assessments of satisfaction in terms of knowledge of the described pedagogical and didactic system, as well as the perceived importance of the founder, do does not differ much in the two groups of respondents. Further research confirmed the assumption that education in the sisters’ schools aroused curiosity about Darowska’s views in a significant proportion of graduates; therefore, the motivation to deepen knowledge in this area arises in students after completing the school, rather than during the time of education. According to the young people, preparation for the final examination is of the utmost importance during their time at the sisters’ schools and in the boarding schools.

For the former students, the teacher is an educator, a friend, and a “second parent”, while the student is an independent-minded patriot, a believer with plans for the future. More than half of the graduates are of the opinion that this image of an educator corresponds to the teachings of Mother Marcelina. Current students evaluate the teacher through the prism of the information they impart, believing them to be an engaging mentor to students, who are both in the process of acquiring knowledge and fostering their own sense of belonging as members of a unique community in the school. Graduates were much more likely to notice differences between teachers who follow Darowska’s approach and other educators they know. Low cohesion scores (6–7%) and the number of generally negative teacher evaluations (2 respondents) were similar in both groups.

Like most studies that focus on a single area of investigation, this work has some limitations in terms of the generalisability of the results (even within other Catholic schools). In addition, the study does not provide insight into teachers’ attitudes and needs, which could be the subject of future research. The respondents did not provide information on their age, education and religious commitment—this could be crucial for understanding the differences in opinion. In future studies, the results of the open questions could also be analysed in more detail using other methods of analysis.