1. Introduction

Western families have undergone profound transformations in recent decades—changes that became noticeable as early as the late 1960s (

Blake 1966). However, this transformation did not signify its decline, contrary to the predictions of some works at the time (

Bane 1976;

Lasch 1979;

Popenoe 1993). This supposed decline was associated with phenomena such as shifting gender roles, declining marriage rates, cohabitation outside of marriage, rising divorce rates, and a reduction in the number of children. According to this perspective, the family was losing its relevance as a traditional institution of early modernity, which was based on a nuclear structure with a clear division of roles between spouses (

Popenoe 1993). This diminishing importance of the family institution implied the erosion of the moral and normative frameworks that had sustained and guided its members throughout the first phase of modernity up until the 1960s (

Illouz 2020). What, then, changed with the shift from the modern family to that of

late modernity?

Modern families were structured around marriage and children, combining traditional and modern elements. From a traditional standpoint, it was an institution based on a clear division of roles between spouses: the man was the breadwinner and provider, while the woman was responsible for child-rearing and education. The structure remained hierarchical and disciplinary, with the man holding authority over both wife and children. Nevertheless, alongside these traditional traits, early modern families also incorporated more modern elements. Marriage was no longer a result of a family’s arrangements with economic, social, and moral implications, but rather the outcome of a romantic and emotional choice made by the partners themselves. Thus, early modern families merged a structural, hierarchical, and disciplinary dimension with a more affective, emotional, and community-oriented one (

Illouz 2012;

De Singly 2007;

Beck and Beck-Gernsheim 2001;

Stone 1990;

Anderson 1988;

Ariès 1987;

Shorter 1977).

For a significant period—corresponding to the first phase of modernity—these two dimensions of the family coexisted with limited conflict, in the sense that few contradictions emerged between the productive and reproductive spheres (

Beck and Beck-Gernsheim 2001). In the reproductive sphere, the woman managed the household and raised the children, while the man worked. These spheres, with their respective temporalities, remained clearly separated and functioned with minimal interference. This arrangement was underpinned by a specific moral and normative order: the “good mother” was the caregiver and manager of the home, while the “good father” was the working provider and figure of authority. This moral order was further legitimized by religion: most marriages were celebrated in church, and children born within wedlock were baptized (

Bruce and Voas 2023;

Storm and Voas 2012;

Crockett and Voas 2006).

However, this familial universe—characteristic of the first phase of modernity—also had its weaknesses. From the father’s perspective, his authority began to decline. It was no longer based on his exemplary role, as salaried labor made him increasingly absent. Moreover, his authority could no longer rely on intergenerational transmission of assets, as children became increasingly dependent on opportunities arising from education and employment. As a result, paternal authority came to be perceived as mere imposition (

Lasch 1979,

1999). While the father became a more distant and less authoritative figure, the mother remained present—offering support, advice, and affection—and was especially remembered during reflections on childhood and adolescence (

Durán and Duque 2025;

Duque and Durán 2023).

Nevertheless, children still aspired to improve their social status, which maintained a certain intergenerational bond. This was expressed through a meritocratic spirit focused on work and education (

Costa et al. 1990;

Pais 1989;

Andrade 1989), and a sense of rootedness in families’ origins (

Almeida 1986). These aspirations implied accepting certain sacrifices in anticipation of future rewards in the form of upward mobility (

Ramos 2014;

Estanque and Mendes 1999;

Cabral 1998;

Barreto 1995). Members of this generation—who came of age in the 1980s and 1990s—combined hedonistic, expressive, and self-fulfillment values with others that were meritocratic, positional, sacrificial, and integrative. Personal fulfillment required first fulfilling obligations associated with hierarchical and disciplinary structures of education and work. However, this fulfillment was incomplete without the possibility of free participation among equals in the spheres of leisure and consumption.

For the women of this generation, the desire for autonomy was especially linked to integration into education and the labor market. By the 1990s, women were the majority enrolled in nearly all higher-education degrees except engineering (

Ferreira 1999), and by the mid-1990s, female employment represented 45% of the active population—one of the highest rates in Europe for the 25–49-year-old age group (

Ferreira 1999;

Cardoso and Pedro 1993). These women would confront most acutely the contradictions stemming from the need to reconcile work and family time, in a context of an underdeveloped welfare state (

Ferreira 1999).

In the Portuguese case, we are thus dealing with the so-called bridge generation—those who experienced the transition from a traditional to a modern society and raised the next generation in smaller, more diverse, and open family structures, instilling values and attitudes shaped by their own biographical experiences. This was also the first generation to experience religion in a more individual and reflective way. Although they were socialized in traditional communities where religion was taken for granted, their lives unfolded in a democratic, secularized society. This did not lead them to abandon religion, but rather to adopt a more distanced and critical stance, aligning with increasingly secular and pluralistic attitudes and values (

Durán and Duque 2025;

Duque 2014,

2022). These values no longer referred to a religious tradition or to the fulfilment of obligations grounded in such tradition, but rather to fully secularized spheres—work, education, consumption, and leisure—through which individuals projected their aspirations for advancement and recognition (

Durán and Duque 2018). For these individuals, life derived meaning primarily from these immanent spheres, relegating the universe of transcendence to the background (

Kasselstrand et al. 2023;

Stolz et al. 2016;

Taylor 2015).

Nevertheless, integration into these spheres entailed, as mentioned earlier, the acceptance of disciplinary institutional norms and a certain ethic of effort, in order to achieve the desired autonomy and recognition. Indeed, this was one of the core messages this generation sought to transmit to their descendants (

Durán and Duque 2018). However, their children would receive this message differently. Having grown up in a fully democratic society with greater material well-being, they were more attuned to expressive individualist values, which they projected in a meritocratic way, along with hedonistic and civic values (

Durán and Duque 2025;

Duque and Durán 2023).

The aforementioned changes did not lead, as previously suggested, to the weakening of the family as an institution. The family continues to be one of the most highly valued institutions, although the reasons for this valuation have changed in recent decades (

Ramos and Magalhães 2023). Today, people value the family more for sentimental, material, and emotional reasons than for moral ones linked to intergenerational duties. These moral reasons have moved to the background. Fewer people, for example, feel a duty to care for their elders or to have children for the sake of family continuity or the perpetuation of a collective identity (

Ramos and Magalhães 2023). The increasing emotional closeness of modern families has been accompanied by the decline of the moral norms and values that once made individuals feel part of a higher order destined to endure. As Tocqueville presciently observed—anticipating the development of the modern families—“I think that as mores and laws become more democratic, the relationship between father and son becomes more intimate and gentler; there is less etiquette and authority, but greater trust and affection. The natural bond tightens, while the social bond loosens” (

De Tocqueville 1993, II, pp. 166–67).

Modern families’ increase in intimacy, individualism, pluralism, and tolerance has also resulted in more personalized and less ritualized family relationships. Yet this transformation is not without contradictions. As individuals pursue personal goals—especially in education, work, leisure, and consumption—they often struggle to attain them within collective and institutional frameworks that both enable and constrain such pursuits.

Portuguese families are no exception, as we shall demonstrate. In the following sections, we present the results of a study on Portuguese values and attitudes regarding family life, which we will subsequently discuss. Before doing so, we will describe the methodology used to carry out this research.

2. Materials and Methods

This study employed a quantitative methodological approach, operationalized through a structured questionnaire survey, with the aim of examining contemporary transformations in families’ values in Portugal, particularly the influence—or erosion—of religion within the family sphere. The research design was informed by a sociological perspective attentive to both structural patterns and subjective meanings, and the instrument was developed to ensure internal consistency with the overarching analytical objectives.

The questionnaire was structured around four core thematic axes. The first focused on respondents’ current relationship with their family, assessing the perceived quality of familial ties, frequency of interaction, shared practices and activities, and the importance ascribed to emotional and relational dimensions of family life. The second axis addressed changes in the transmission of families’ values, exploring perceived intergenerational shifts, the influence of technology and social media, and contrasts in value orientations between generations. The third examined the role of the family in contemporary society, including its perceived social relevance, emerging family configurations, current challenges, and the role of religion in the domestic sphere. Lastly,

Section 4 gathers sociodemographic data, including age, gender, marital status, educational attainment, employment status, religious affiliation, and frequency of religious participation.

The questionnaire consisted predominantly of closed-ended questions, facilitating statistical treatment and enabling cross-tabulation of variables. Its structure ensured analytical coherence, allowing for a robust examination of the evolving contours of families’ values and the role of religion in the domestic domain amid broader societal transformations.

The survey was disseminated online via the Google Forms platform, from mid-November 2024 to early March 2025. Distribution was carried out digitally using a non-probability convenience sampling strategy, complemented by snowball sampling. Initial participants were invited to circulate the questionnaire within their personal and professional networks, expanding reach across diverse segments of the Portuguese population.

This methodological strategy was considered appropriate given the exploratory and descriptive nature of this study, which aimed not at statistical representativeness but at capturing the diversity of subjective experiences and value orientations within contemporary Portuguese society. Although convenience sampling does not allow for probabilistic generalization, it is widely accepted in the sociological literature as a suitable approach in exploratory social research (

Duque and Calheiros 2017), especially when the objective is to access emerging cultural trends, evolving practices, and dynamic processes of value reconfiguration.

The final sample comprised 3634 valid responses from individuals residing in Portugal, with considerable variation in sociodemographic characteristics. Descriptive statistics indicate that the majority of respondents were aged between 30 and 64 years (86%) and possessed a bachelor’s degree (51%) or master’s degree (23%), reflecting a relatively high educational profile. Regarding employment status, 69% were employed full time, 14% were self-employed, and 7% were retired. In terms of marital status, 63% were married, 17% single, 10% in cohabiting relationships, and 8% divorced. Religious engagement revealed marked heterogeneity: 29% reported attending religious ceremonies weekly, while 8% never did so, illustrating the pluralism of religious practices within the sample.

This dataset enabled comparative analysis between sociodemographic groups, particularly with respect to the adherence to—or distancing from—traditional religion-based values, and provided a critical lens through which to understand the ongoing reconfiguration of the family institution in Portugal’s late-modern social context.

4. Discussion

We now turn to a discussion of the findings previously presented. As shown, the results reveal a broad consensus among the Portuguese population surveyed regarding the value attributed to the family institution. This aligns with patterns observed in surveys over recent decades—not only in Portugal, but also in neighboring Spain and other European countries (

Ramos and Magalhães 2023;

Durán and Duque 2018;

EVS 2008;

Pais 2005). However, the reasons behind this valuation have changed substantially over the past few decades, a shift that began to be noticeable in Portugal from the mid-1980s onward (

Durán and Duque 2018;

ICS 1987).

Whereas values previously tied to a moral sense of duty, community belonging, and religiously legitimized tradition—along with hierarchical and positional norms—have increasingly been pushed into the background, more democratic, expressive, and convivial values—such as equality, freedom, and tolerance—have gained prominence. So too have values linked to personal development and performance (

Ramos and Magalhães 2023;

Durán and Duque 2018;

EVS 1990,

2008;

Pais 1998,

2003,

2005;

ICS 1987).

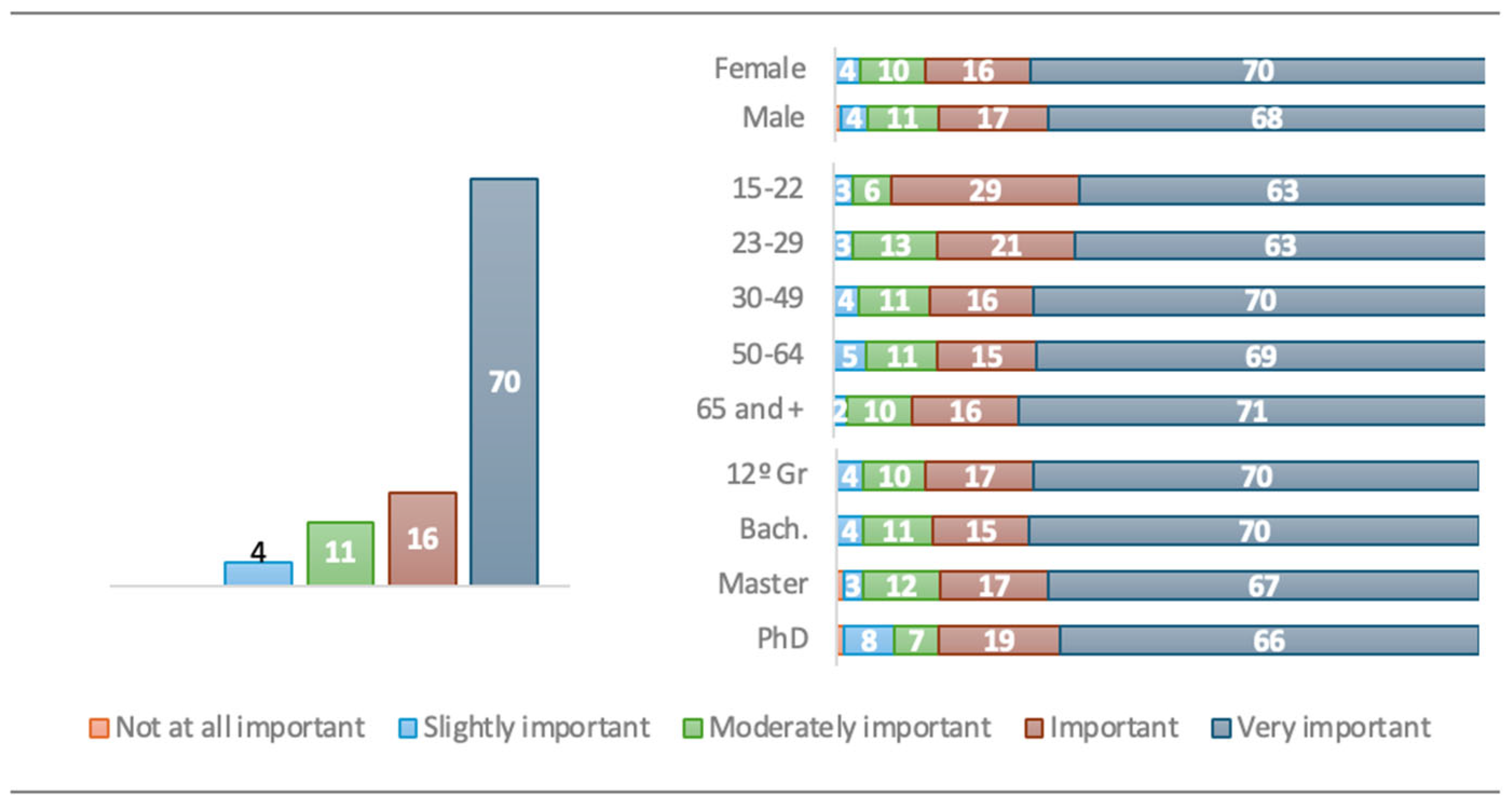

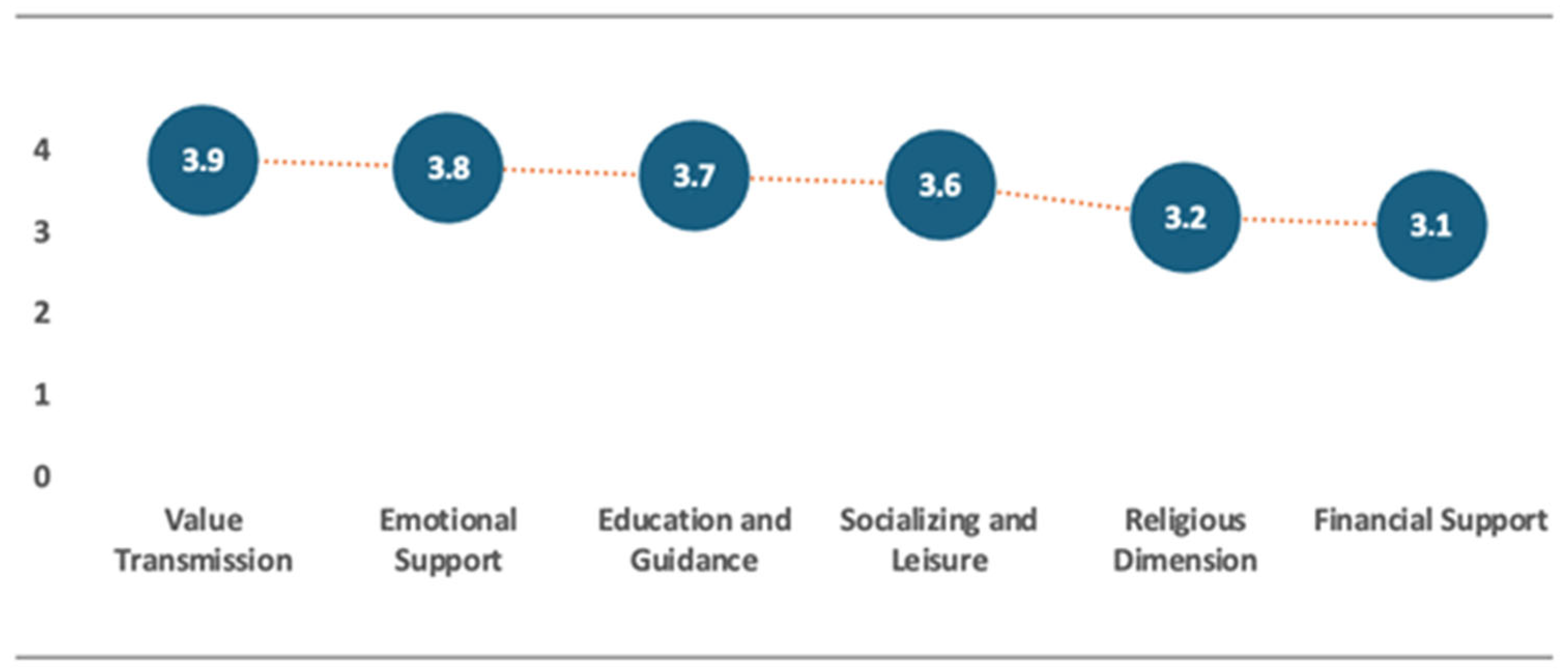

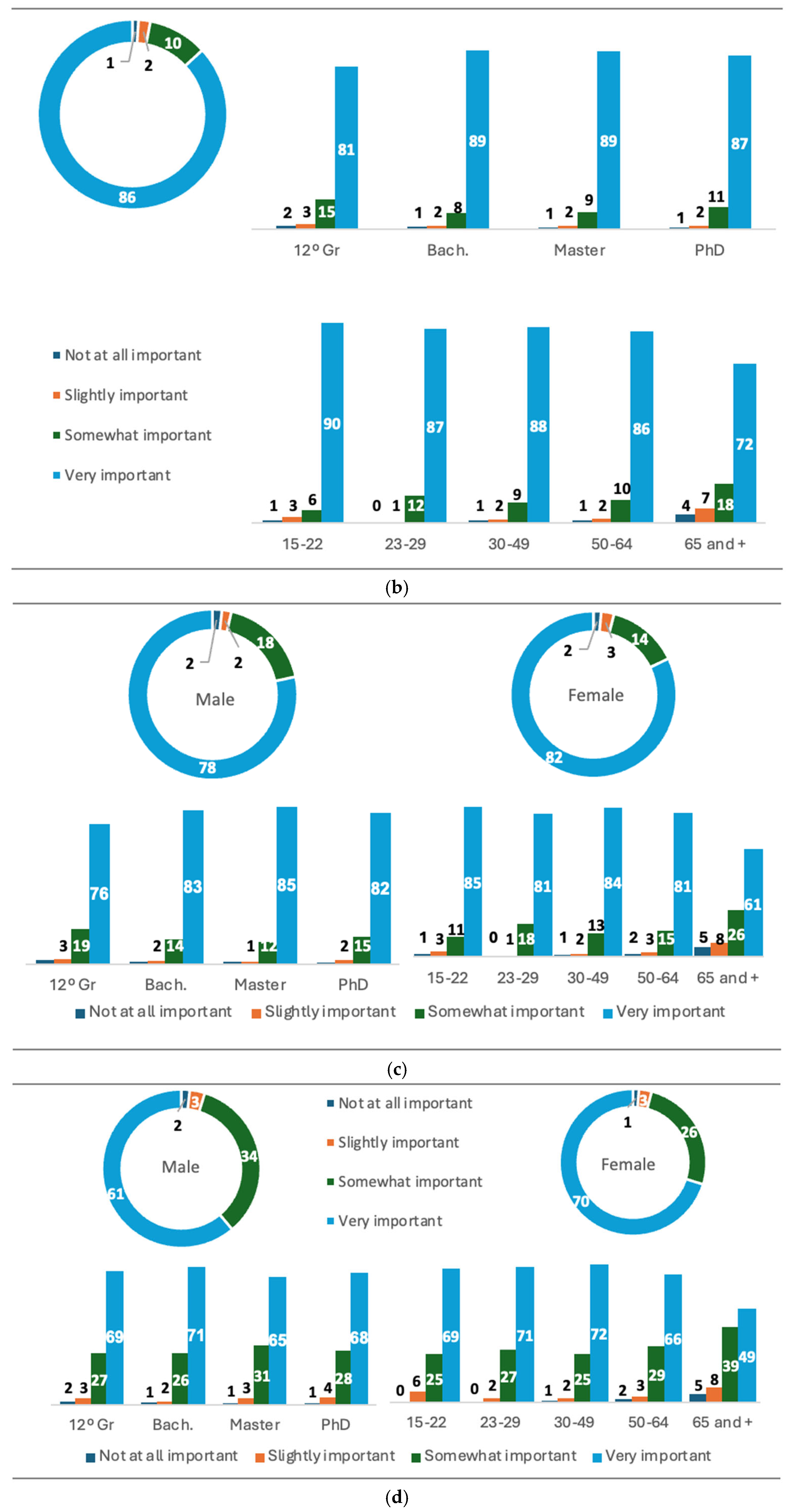

Our survey reflects this shift. The

transmission of values, emotional support, guidance, and education emerge as the most valued aspects of family life, followed (at a distance) by

leisure, cohabitation, and

financial support (

Figure 4). The fact that financial support is valued by relatively fewer respondents—though still more than half—might stem from the assumption that material assistance from family is a given. Perhaps this explains why people over 65 years old value it more, as they experienced greater material hardship in their youth compared to the younger generation (15–22 years old), who did not face such struggles (

Ramos 2014;

Costa et al. 2000), and who have been socialized in more post-materialist values (

Inglehart 2008).

The other family aspects most widely valued are the

transmission of values, emotional support, and guidance and education. The

transmission of values is more highly valued by women, likely because they are more involved in childrearing (

Montañés and Moreno 2022;

Ramos et al. 2019). It is less valued by both younger (15–22 years old) and older (65+ years old) respondents compared to adults (30–64 years old), likely because the latter are in the stage of active parenting, while the others are either not yet parents or have transitioned into grandparenting, focusing more on emotional than educational roles.

Emotional support is more appreciated by younger individuals (15–22 years old) and those with higher educational attainment—people who have been raised in more egalitarian and emotionally expressive families. Conversely, those over 65 years old, raised in more hierarchical family settings with greater generational distance, place less importance on emotional dimensions of family life. These findings are consistent with other studies we have conducted in recent years (

Duque and Durán 2023,

2024,

2025;

Durán and Duque 2019,

2025).

Another key area of family life identified as highly important by respondents is

education and guidance. Initially, this emphasis reflects the modern belief in education as a crucial tool for personal advancement and liberation (

Durán and Duque 2019). Yet, this perception has also evolved in recent decades. The meritocratic ideal of achievement has diminished in relative importance or has become conditioned by expressive values associated with personal fulfillment (

Ramos and Magalhães 2023;

Durán and Duque 2019;

De Singly 2016;

EVS 2008). Still, this shift does not imply the rejection of meritocratic values; rather, they have been redefined in more expressive and individualistic terms. Families continue to value education as a means of empowerment, but now primarily in the service of each individual’s aspirations and interests.

These two dimensions—the meritocratic (achievement-focused) and the expressive (self-realization)—often coexist in tension (

Gauchet 2002). The first implies institutional recognition, which can conflict with the more personal goals families set for their children (

Durán 2021). This context helps explain why such a large majority values education and guidance in family life. However, to explore this more fully, future research should include more targeted questions.

Our data also show that women value education and guidance more than men, consistent with their stronger involvement in caregiving and educational roles (

Montañés and Moreno 2022;

Ramos et al. 2019). Additionally, younger respondents (15–22 years old) assign less importance to this dimension than adults (30–64 years old), perhaps because they are not yet in the parenting stage, or because contemporary youths are less invested in meritocratic values (

Duque and Durán 2024).

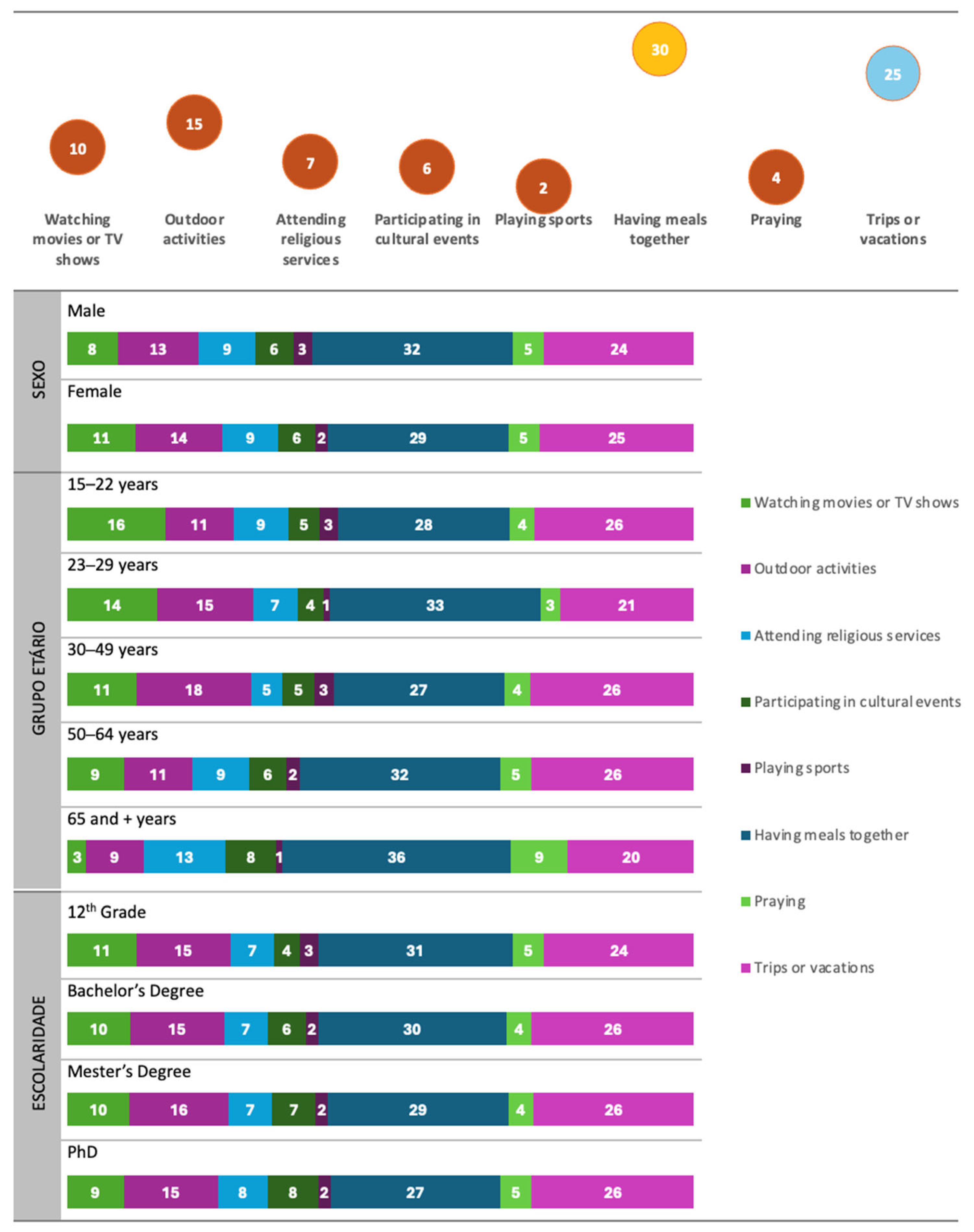

Although to a lesser extent, but still with majority support (

Figure 4), respondents also consider

cohabitation and leisure important aspects of family life. This shift aligns with the family’s transformation over recent decades from a more disciplinary and sacrificial institution into one that is more relational, hedonistic, and liberating (

De Singly 2007,

2016;

Illouz 2012;

Beck and Beck-Gernsheim 2001). Members of younger generations, having been socialized in this new familial culture, particularly value this transformation. Conversely, individuals over 65 years old, raised in more hierarchical and austere families, are less inclined to value leisure and conviviality.

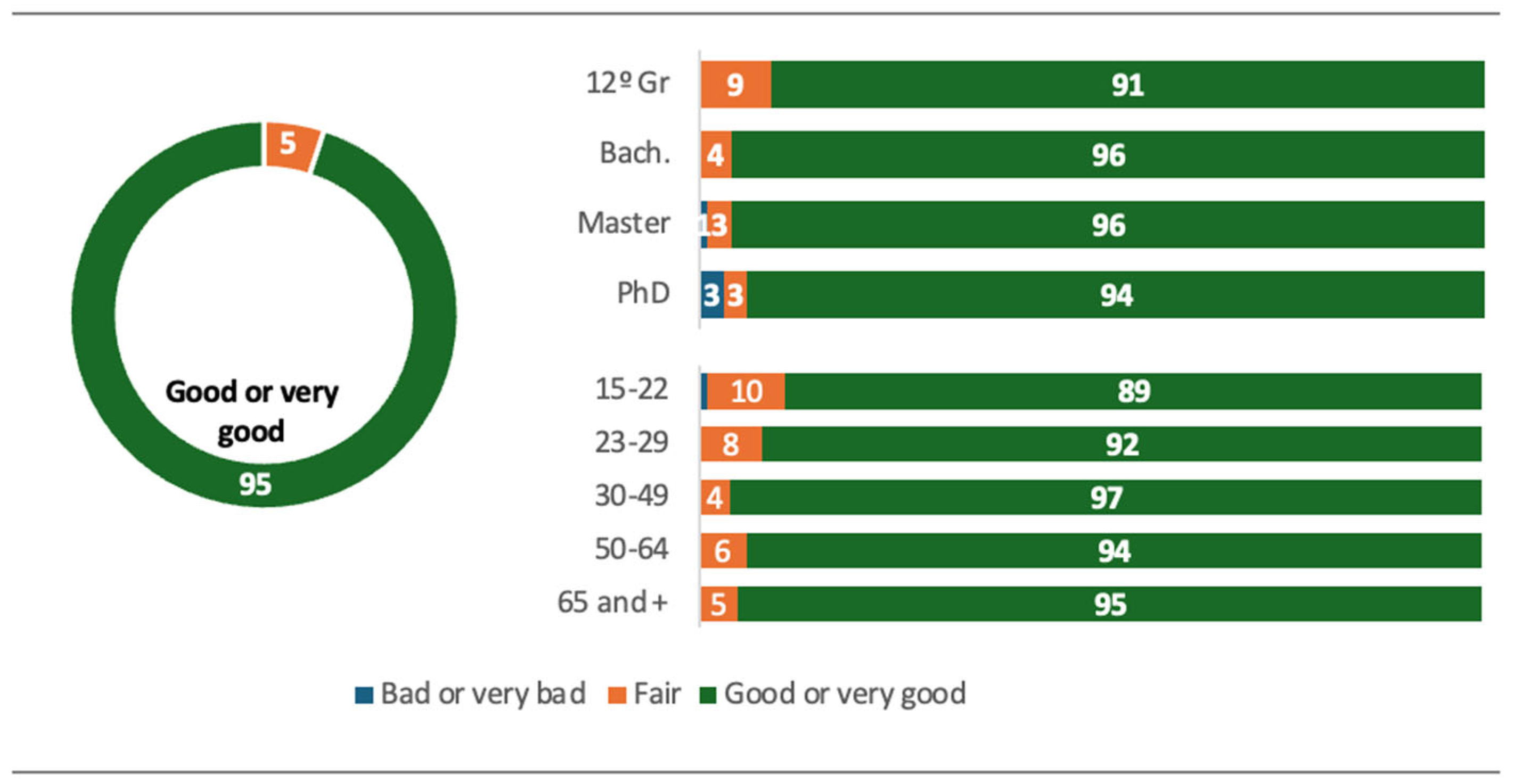

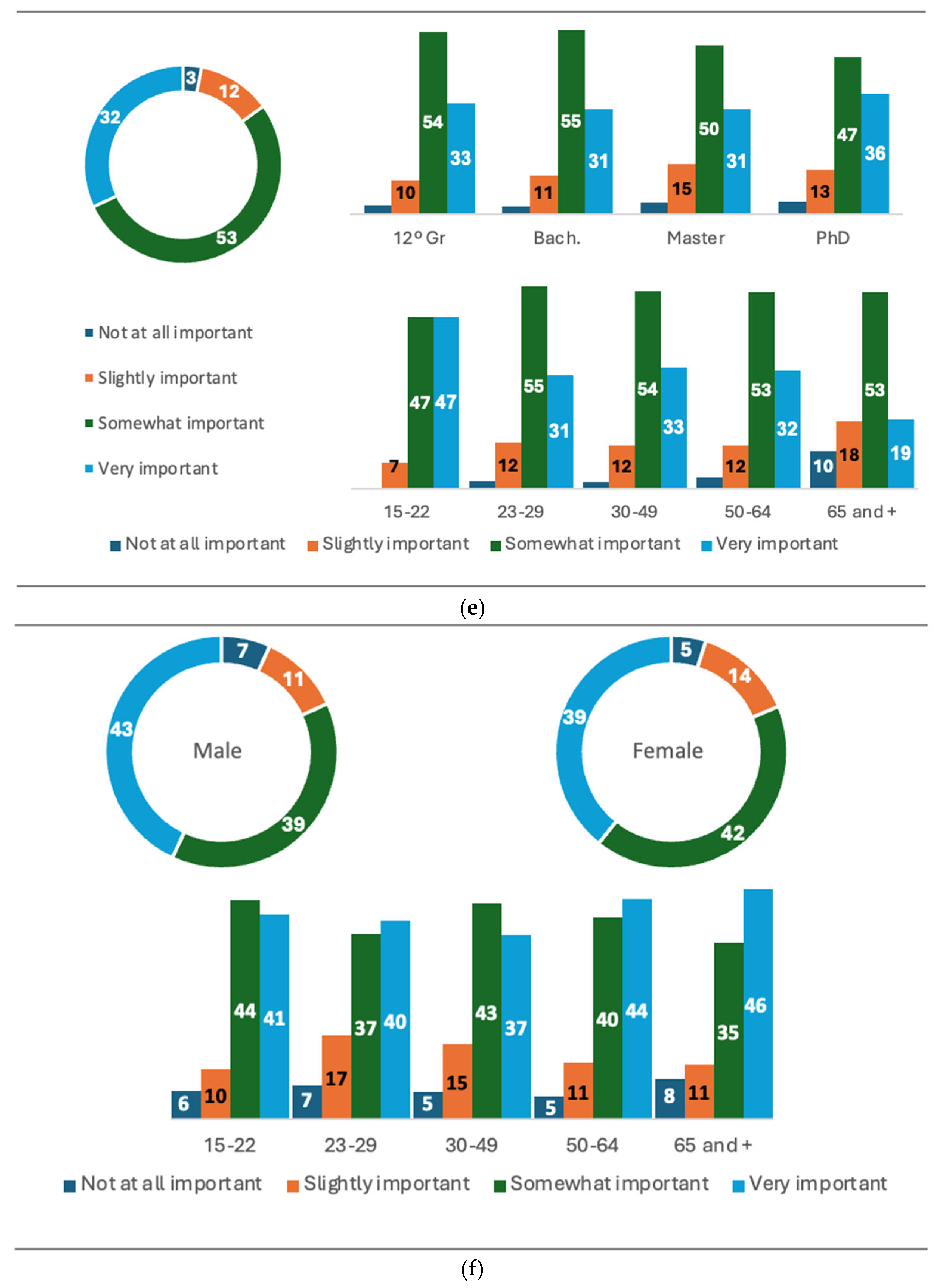

However, how can we explain the significant value that the vast majority of respondents attribute to the religious dimension in family life (40.1% consider it very important and 41.2% important)? First, it should be noted that this valuation is relative: when these results are compared with the number of people who rate other aspects of family life as very important—also presented in the survey—it becomes clear that religion receives a much lower rating (3.2) than “transmission of values” (3.9), “emotional support” (3.8), “education and guidance” (3.7), and “socializing and leisure” (3.6) (

Figure 3). Similarly, when the preferences of the respondents in the domain of family practices are analyzed, only 4% state that praying as a family is one of the activities they value most—a percentage only slightly higher than that of those who value doing sports together (

Figure 6).

From this perspective, it becomes evident that the Portuguese families has undergone a clear process of secularization (

Ramos and Magalhães 2021,

2023;

Duque 2014,

2022), a process that is less pronounced among those over 50 years old, and particularly among those over 65 years old, as our survey shows (

Figure 4f). These are the individuals who were most strongly socialized in a religious environment (

Durán and Duque 2025). Nonetheless, one of the clearest manifestations of this secularization process is the growing decline in the importance of religion in the transmission of families’ values and in religious practices, as shown both in our survey and in larger-scale surveys, such as the EVS (

Ramos and Magalhães 2023).

The latter survey, for instance, reveals that although a majority of people declare themselves religious, only 14% say they attend religious services weekly, compared to 19% who do so rarely and 31% who never or almost never attend. It also shows that while 24% report praying daily, 30% say they never pray, and 11% do so once a week. The same survey also highlights a clear decline in religious practices compared to participants’ childhood and adolescence (

Ramos and Magalhães 2023).

This undeniable process of secularization in Portuguese society has, however, been less pronounced than in other European countries (

Bruce and Voas 2023;

Kasselstrand et al. 2023;

Ramos and Magalhães 2023;

Luijkx et al. 2022;

Ruíz Andrés 2022;

Coutinho 2019;

Bréchon 2018;

Duque 2014,

2022;

Crockett and Voas 2006), and it has instead aligned more closely with what Grace Davie has termed “believing without belonging” (

Davie 2006,

2015). That is, although a majority claim to hold religious beliefs, only a minority report attending religious ceremonies regularly. Furthermore, those who do believe tend to do so in an increasingly individualistic, pluralistic, and flexible manner (

Ramos and Magalhães 2023). Religion has thus become a progressively less ritualized experience.

In any case, this secularization of Portuguese society has also clearly impacted the realm of family life. As shown in our survey, religion no longer figures among the aspects of family life that respondents consider most important, and almost no one values praying together as a family anymore. The most valued aspects of family life, therefore, lack a religious foundation, indicating that religion no longer guides people’s lives within the family domain—it is no longer part of their horizons of meaning (

Taylor 1996, p. 42), nor of the narratives that provide coherence to the goals they seek to pursue and attain in life.

More concretely, neither the transmission of values, nor emotional support, nor education and guidance—those aspects that the majority of respondents regard as most important—are justified in religious terms anymore, but rather in strictly secular and immanent ones. Other values that were once particularly esteemed and grounded in religion have been relegated to the background. These values, which formerly assigned individuals a position within the community, entailed the internalization of duties and obligations, were associated with a certain sense of respect, and connected people to a commonly shared order that transcended them and exercised a certain moral authority (

Storm 2016), are now barely considered.

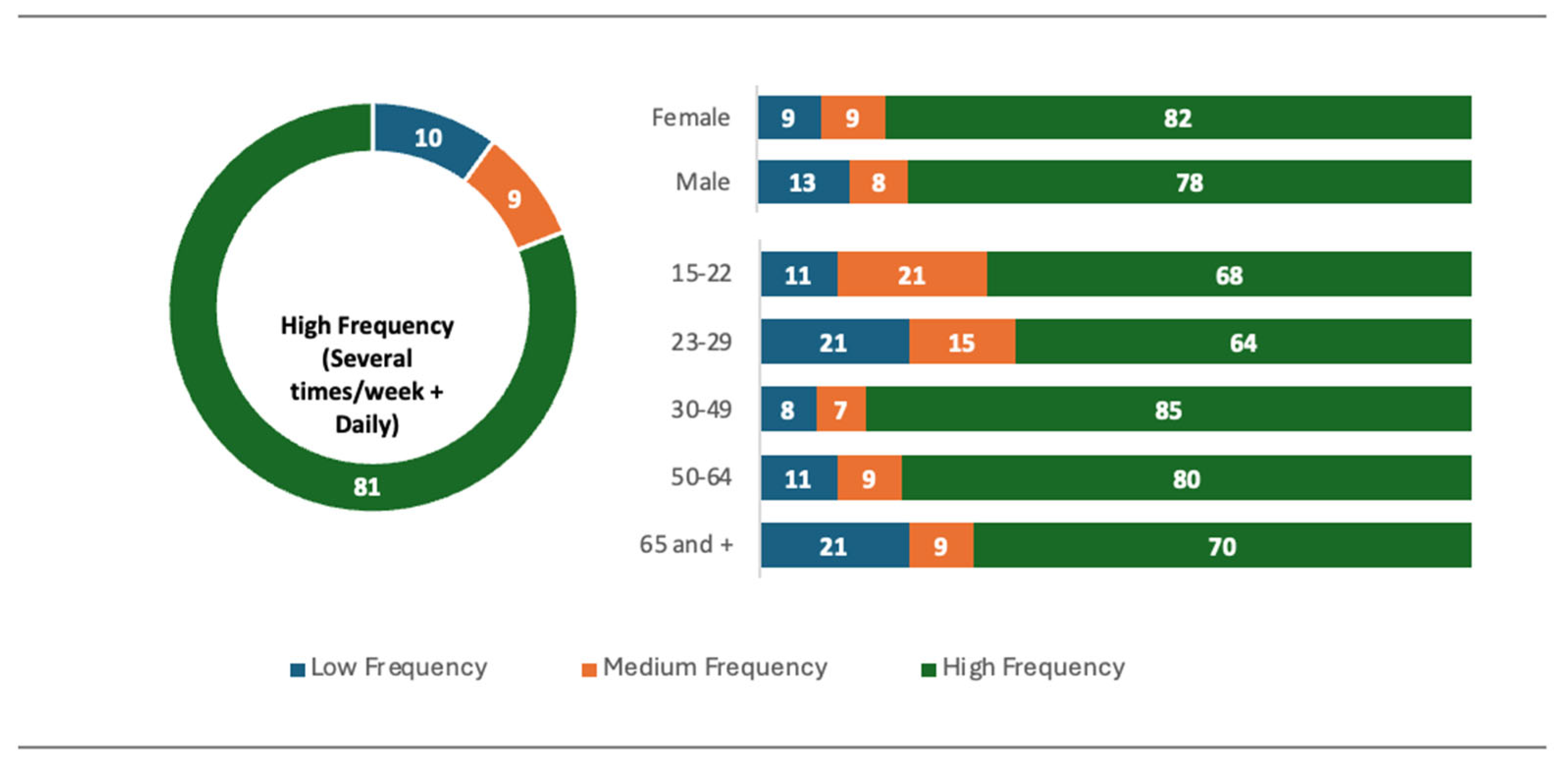

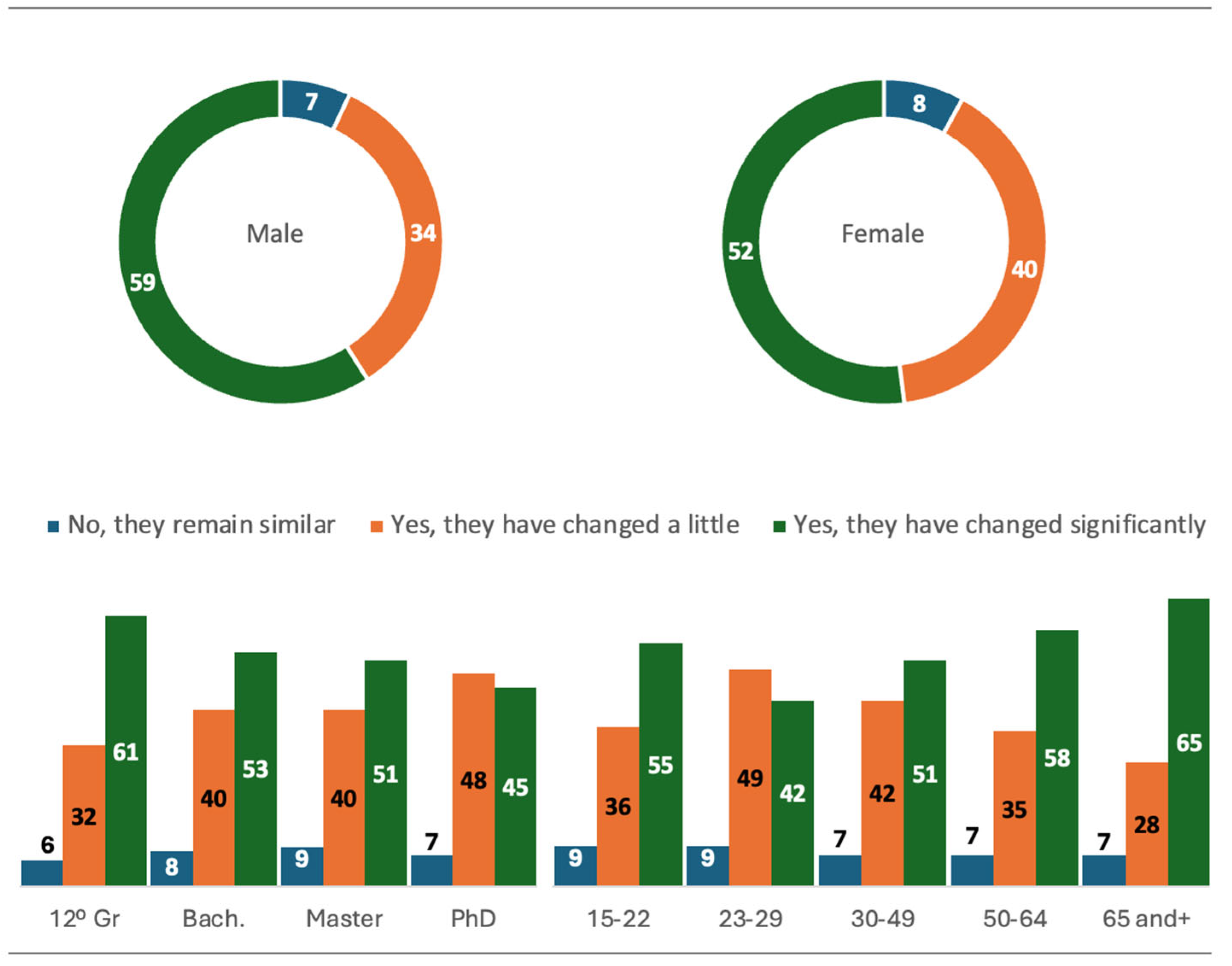

In recent decades, we have witnessed a shift in values, which has become clearly manifest in the domain of family life. The respondents are fully aware of this, and the vast majority believe that there has been a change in the transmission of families’ values over time (

Figure 8). However, certain generational differences emerge here: individuals over the age of 65 years—most of whom were socialized during childhood and early youth in pre-industrial communities and traditional value systems that significantly shaped their identities (

Duque and Durán 2023;

Ramos 2014)—are those who most strongly emphasize this transformation in values. Conversely, those with higher educational attainment tend to perceive the change in families’ values as less significant.

This latter observation aligns with other recent studies we have conducted in northern Portugal, which also show that individuals with greater academic education are those who have most deeply internalized modern values, and therefore adopt them more naturally (

Duque and Durán 2023,

2025;

Durán and Duque 2025). This can be explained by two factors: they belong to generations that were socialized in a democratic, more pluralistic and open society, and they are also the most educated (

Braga da Cruz et al. 1984), having prolonged their youth within environments that reinforced modern value systems (

Costa et al. 1990). For these individuals, the shift in values has thus meant the surpassing of more traditional ones—a transition which, for younger individuals, especially those with higher levels of education, has translated into the naturalization of modern values, as their identity has been built in close connection with them (

Ferreira et al. 2017;

Pais 2003). This explains why they are less sensitive to the perception of change.

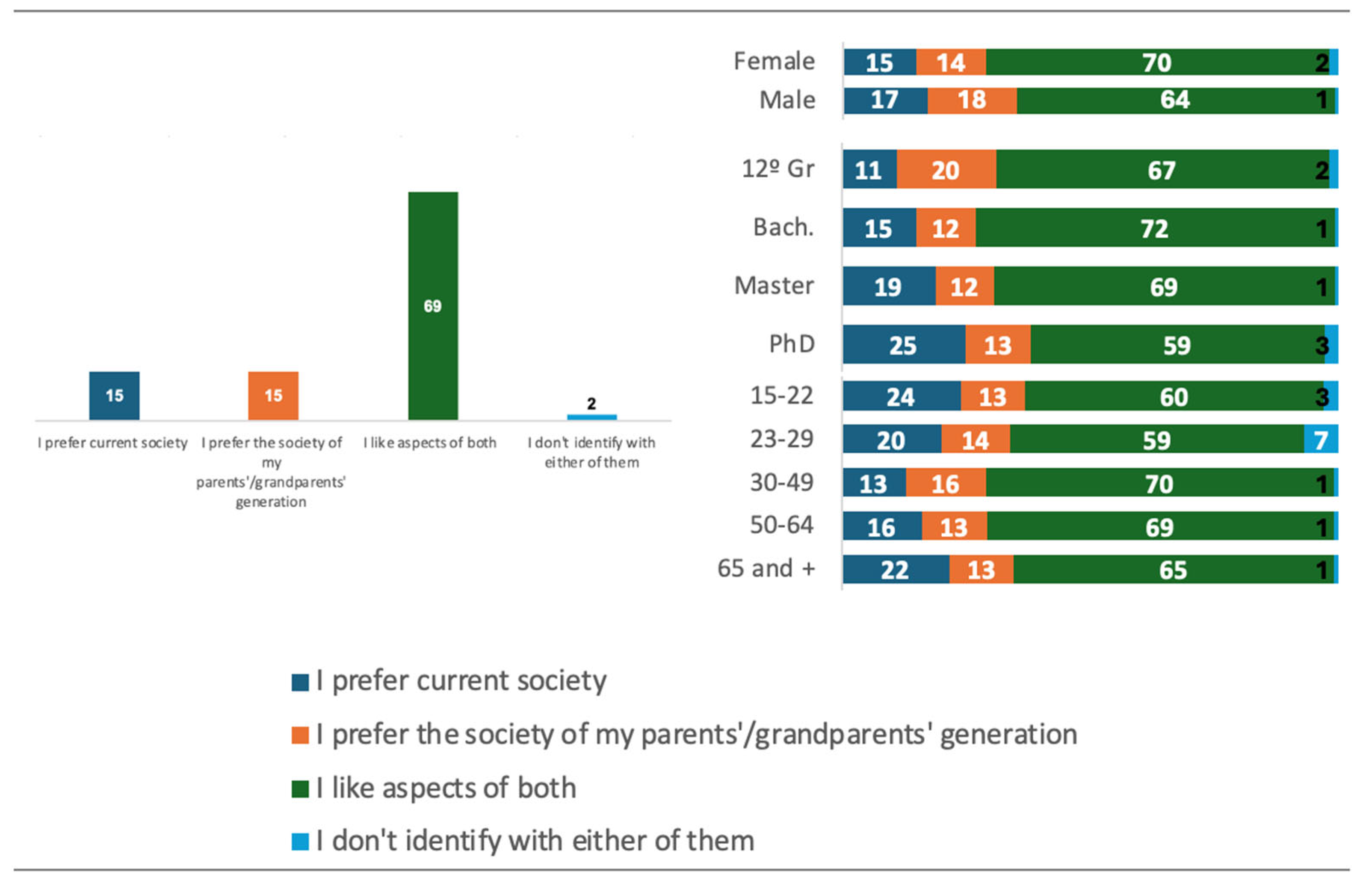

However, individuals belonging to intermediate generations—those who have experienced a transition throughout their lifetime from a traditional society, in which they were socialized during childhood and early youth, to a modern, democratic one—tend to hold a more critical view of the values of both societies, though they lean more toward modern values. While a majority of respondents (68.6%) say they appreciate aspects of both societies, it is those in the intermediate generations who most frequently express this preference (

Figure 9). Indeed, they are the ones who have most vividly retained the importance of these values—both modern and some traditional—within their frameworks of memory (

Halbwachs 2004). In the case of traditional values, because they were raised in communities where respect for such values was emphasized; and in the case of modern values, because they later shaped their identities within the context of a modern and democratic society.

As such, they adopt a more distanced and critical stance than both the oldest (those over 65 years old) and the youngest (aged 15–22 years) respondents in relation to the values of both societies. While the latter have largely taken either traditional or modern values for granted, intermediate generations retain both value systems within their frameworks of meaning. This enables them to be critical of traditional values from a modern perspective—or vice versa. Nonetheless, they tend to be more critical of traditional values, having experienced democratic modernity as a means of overcoming the authoritarian and traditional society in which they were raised. At the same time, they have also had sufficient time to become disillusioned with certain aspects of the modern values they once embraced with hope and enthusiasm in their youth.

These findings are consistent with the qualitative research we also conducted in northern Portugal (

Durán and Duque 2025;

Duque and Durán 2023,

2025). These studies show that members of the intermediate generations adopt a more reflective attitude toward the values of both traditional and modern societies than either their parents or their children. Precisely because of this, they interpret one set of values through the lens of the other, based on their own life experiences, thus creating new attitudes and new values as a result of these reconfigurations.

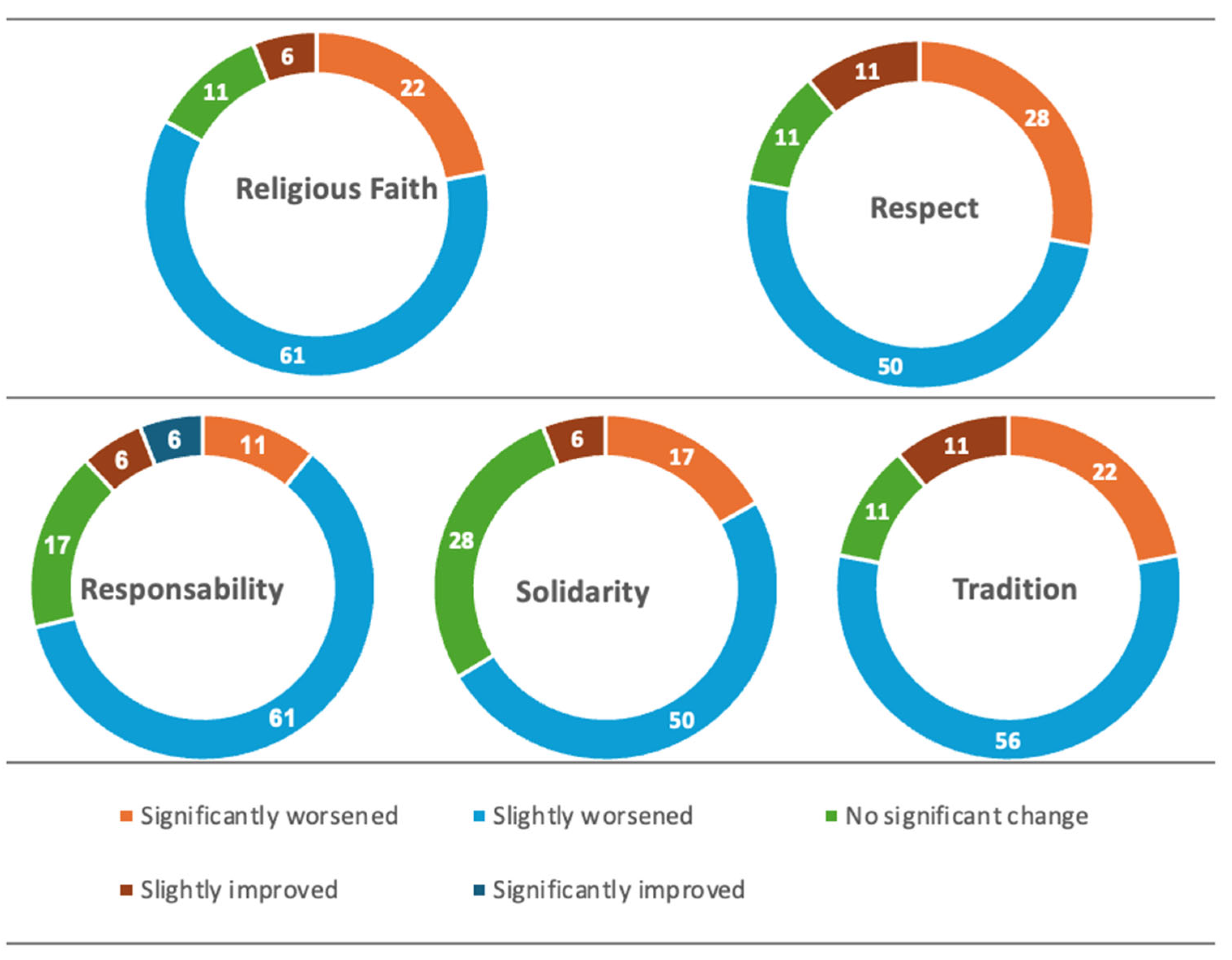

Taking all of this into account helps explain the data from our survey, in which a majority of respondents report that there has been a negative change in values such as

respect,

religious faith,

responsibility,

solidarity, and

tradition—values more strongly associated with traditional societies (

Figure 7). At the same time, 69% state that they prefer aspects of both the current society and that of their parents and grandparents (

Figure 9).

In this context, we might say that while younger generations do not truly experience a conflict of values—having been almost entirely socialized within modern value frameworks—older and intermediate generations relate to the values of both worlds in a more reflective and problematic way. While the former tend to respond to this conflict by leaning more toward traditional values, the latter adopt a more reflective stance toward the values of both societies. Thus, they experience the shift in values as problematic: on one hand, they are more critical of traditional values, though not wholly rejecting them; on the other, while they lean toward modern values, they do so with a degree of skepticism. From this skeptical vantage point, they regard traditional values not so much with nostalgia but rather as a potential source of stability in a rapidly changing world—one in which some of the values they once embraced in youth have lost the meaning and solidity they previously held.

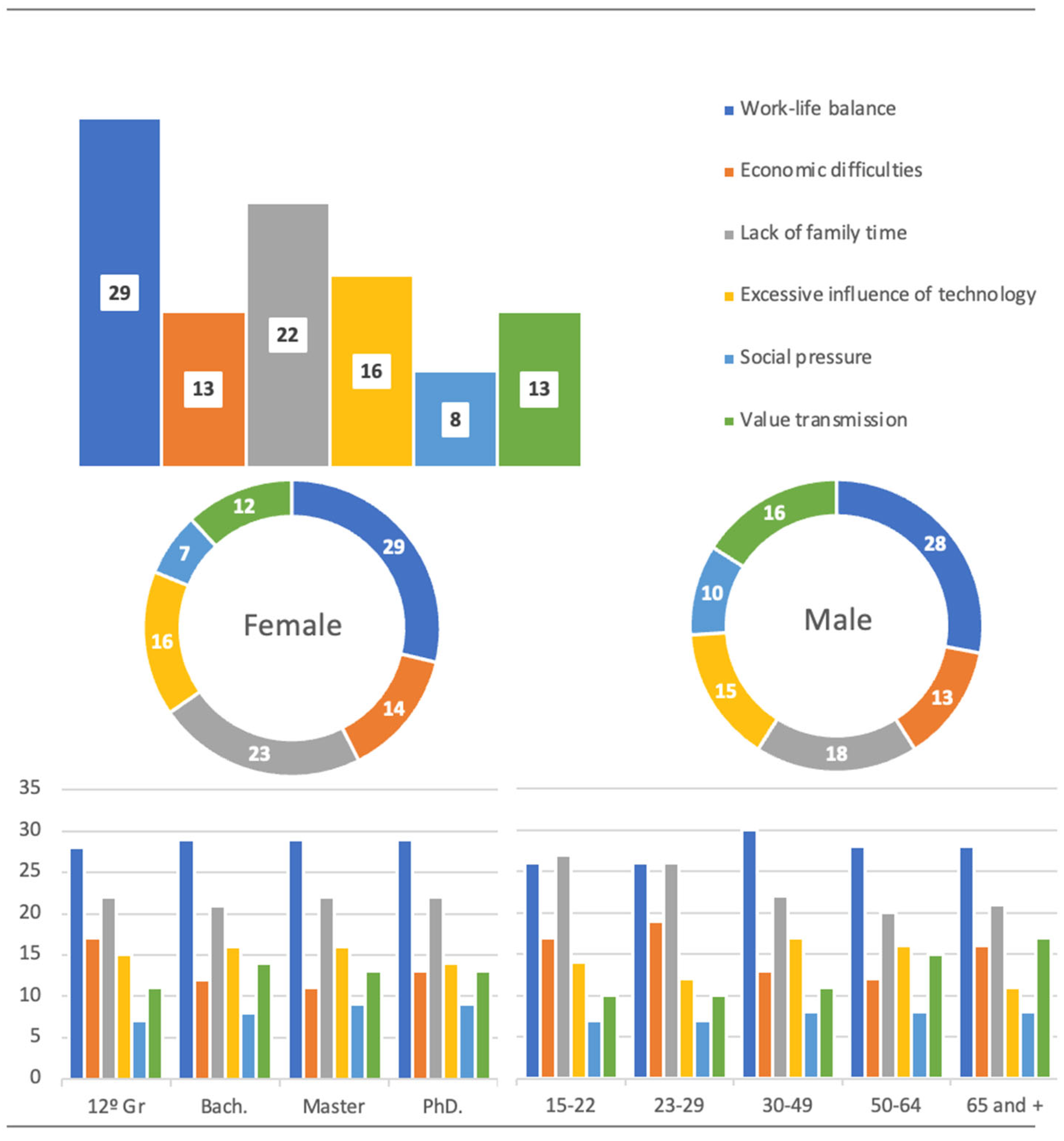

What, in this context, are the main challenges facing today’s families, according to the survey respondents? The most frequently identified challenge was “reconciling personal and professional life” (29%) (

Figure 10). This opinion reflects the difficulties families currently face in integrating the productive and reproductive spheres. These difficulties stem from the way women’s integration into the workforce has occurred—without effective measures that would make such integration compatible with the shared dedication of both partners to childcare and childrearing. Market society has absorbed this change without freeing up productive time in favor of reproductive time. To put it in the stark and incisive words of those who called attention to this issue decades ago: “the subject of the market,” they wrote, “is ultimately the single individual, unencumbered by romantic, marital or family relationships. A fully market-driven society is, consequently, also a childless society, unless children grow up with single, mobile mothers and fathers” (

Beck and Beck-Gernsheim 2001, p. 60, italics and quotation marks in the original).

Nevertheless, people are unwilling to give up having children and are thus forced to confront the contradictions involved in combining the family and work spheres, often with minimal institutional support (

Mendes and Tulumello 2022;

Nobre de Deus and Branco 2022). The labor and productive functions have been socialized by market society, whereas the reproductive function has largely been left to families—and primarily to women. Despite men’s increasing involvement in childcare and education, women still bear the greater burden in this area (

Ramos et al. 2019;

Perista et al. 2016;

Casaca 2013;

Ferreira 2010). It is therefore unsurprising that 22% of respondents state that a key challenge for contemporary families is the

lack of time (

Figure 10). This is also why, although there is a clear preference expressed for families’ rituals—especially shared meals (

Figure 3)—in reality, such rituals have been in steady decline for some time (

Costa 2014).

Despite the fact that, as seen, a large majority of respondents perceive the reconciliation of personal and professional life as one of the most pressing challenges facing families today, this has not led to significant conflict (

Perista et al. 2016;

Ferreira 2010). This may be because work has been conceptualized throughout modernity as a fundamentally liberating activity (

Durán 2011;

Castel 2001;

Méda 1998;

Gorz 1997;

Offe 1992)—first for men, and much later for women (

Arendt 1998). Yet, in the case of women, this liberation implied being freed from the reproductive sphere in which they had long been confined. Consequently, all institutions that promoted this emancipation were seen as being on the “right side” of history, without necessarily doing much to balance the reproductive and productive spheres—without which, such liberation could only ever be partial.

Since productive time continued to dominate—as it had before—this generated few contradictions initially, because women still largely handled the socialization function. Thus, reproductive time continued to be managed within families, mostly by women, and supported by the market (

Beck and Beck-Gernsheim 2001, p. 45). In this context, the families—especially women—became caught in the paradox whereby the long-desired liberation from the reproductive sphere through productive labor ultimately led to the desire to be liberated from productive labor itself, in order to redirect that emancipation toward family life.

This tension is perceptible in surveys such as the European Values Study (EVS). In one wave of the survey, respondents were asked whether they agreed with statements like: “When the mother has a professional activity, children suffer as a result” and “Family life suffers when the woman works full time.” In Portugal, 6% of respondents strongly agreed with the first statement, 40% agreed, and 46% disagreed. For the second statement, 4% strongly agreed, 41% agreed, and 47% disagreed (

Ramos and Magalhães 2023). As can be seen, the proportions of agreement and disagreement were fairly balanced.

At first glance, these results might suggest that a significant segment of Portuguese society still holds traditionalist attitudes regarding the family. However, upon closer examination, this interpretation seems overly simplistic, as it contradicts responses to other questions in the same survey—such as “It is the man’s responsibility to earn money; the woman should take care of the home and family” and “Men are better managers than women.” In these cases, 76% and 89% of respondents disagreed with such statements. Additionally, only 11% agreed with the statement: “When jobs are scarce, men have more right to employment than women” (

Ramos and Magalhães 2023).

These findings align with other studies conducted in Portugal, which indicate that a large majority reject the traditional division of labor—where the man is the breadwinner and the woman is the caregiver and household manager—and instead favor equal participation of men and women in the labor market (

Ramos et al. 2019).

In short, we interpret the finding that most respondents in our survey believe the main challenge facing today’s families is the reconciliation of personal and professional life as having little to do with the persistence of traditional values in Portuguese society. Rather, it reflects the difficulty families face in integrating these two spheres within societies where work time dominates, and where individuals are left to manage family time through their own personal and economic resources. This occurs in a context where family networks are weakening—even in traditionally families-oriented societies, such as Portugal (

Azevedo 2020;

Cordeiro 2016;

Wall et al. 2013)—and where the state has proven unable to compensate for this situation through effective families’ policies (

Matos and Sabariego 2022;

Silva 2016;

Monteiro and Portugal 2013).

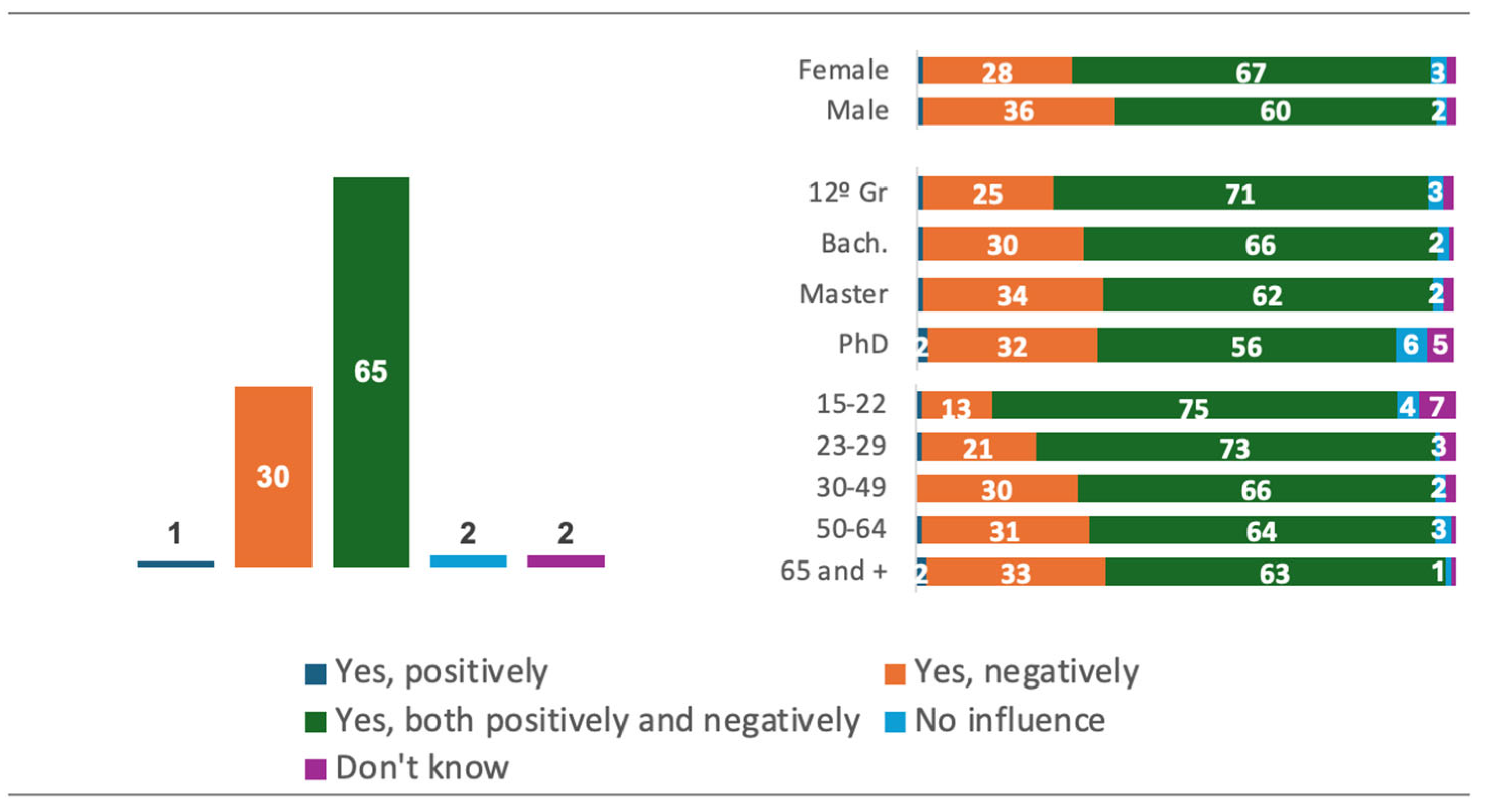

A total of 16% of those surveyed identified another major challenge for contemporary families as being related to

new technologies (

Figure 10). A vast majority (95%) believe that social media influences how families’ values are transmitted; 65% think this influence is both positive and negative, 30% believe it is solely negative, while very few (1%) consider it solely positive (

Figure 11).

These data reveal that, with the accumulated experience of social media use, people are increasingly aware of its influence across various social domains, particularly within the family. For this reason, social media no longer provokes merely suspicion, as it might have at the time of its initial emergence in social life. After several decades of experience, individuals now recognize both its benefits and drawbacks and do not adopt extreme views in either direction.

It is therefore unsurprising that those with the most nuanced views regarding the role of social media in the transmission of families’ values are members of the intermediate generations (aged 30–64 years). Unlike younger individuals (aged 15–22 years), who are digital natives and thus take new communication technologies for granted, and those over 65 years old, who tend to view them more externally and unfamiliar—and therefore more negatively—members of the intermediate generations encountered this reality later in life. Their relationship with technology is neither wholly foreign nor entirely natural. Their perspective is more complex, situated between the closeness of youths and the distance of old age.

This cultural “middle distance” (

Simmel 2001) enables a more complex perspective than that available to other age groups, one that allows for meaningful comparison of life before and after the advent of social media. Their viewpoint is ultimately more critical: they have not been entirely colonized by the technological objective culture that has more heavily influenced the younger population, yet they are not entirely outside it, as many older individuals are. Precisely for this reason, they are more capable of interpreting the world of social media.

Accordingly, the highest proportion of respondents who believe that social media’s influence on the transmission of families’ values is both positive and negative belongs to this intermediate age group. It is also worth noting that people in this age range are more likely to hold educational responsibilities, allowing them to observe more clearly the effects of new communication technologies not only in their own lives but also in the lives of their children.

Nonetheless, when asked specifically about the influence of social media on families’ relationships, more than half of respondents (62%) consider it to be negative or very negative, while 30% say it is neither negative nor positive (

Figure 12). Those with higher levels of education tend to be the most critical, expressing more negative views—likely a result of a more reflective stance. This majority opinion likely reflects growing societal awareness of the impact of social media, particularly its role in fragmenting family spaces and times, fostering individualization, and weakening family bonds and forms of regulation (

Barnwell et al. 2023;

Casimiro and Barbosa 2021;

Silva et al. 2021;

Neves and Casimiro 2018;

Dias and Brito 2016;

Feixa 2005).

Thus, the respondents appear well aware of the major challenges facing families today—first and foremost the reconciliation of personal and professional life, but also those related to the digital and technological realm, particularly social media.

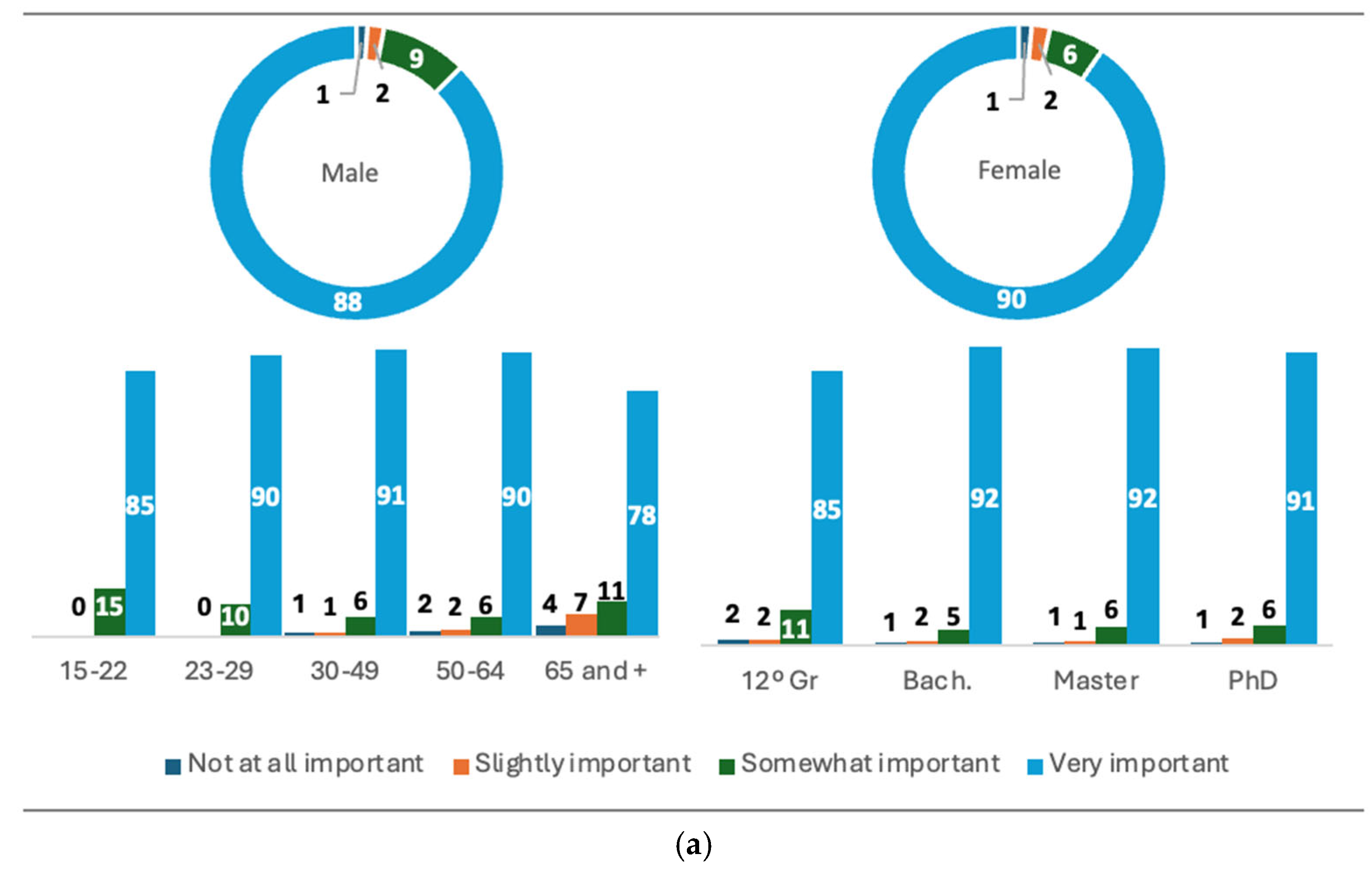

Surprisingly, however, considerably fewer respondents (13%) believe that the

transmission of values is one of the main challenges currently facing the family (

Figure 10), despite the fact that 90% consider it one of the most important aspects of family life (

Figure 4a). For the majority, then, this dimension of family life does not appear to represent a real problem.

How can this result be explained? From our perspective, the less the families are oriented toward transmitting a sense of duties and obligations—that is, the less hierarchical and disciplinary it is—and the more it seeks the fulfilment and emancipation of its members as a path toward the achievement of specific life goals (as shown in this and other studies, such as Ramos and Magalhães 2023), the less likely it is for value conflicts to emerge between generations. Such conflicts were more common in earlier times, when what one generation sought to transmit often clashed with the beliefs and values of their descendants (

Durán and Duque 2018,

2025;

Duque and Durán 2023).

In this context, it becomes easier to understand why a large majority of respondents assign great importance to the transmission of values in family life, while at the same time, fewer than half believe that this constitutes a major challenge for families today.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we have shown that the family remains one of the most highly valued institutions among the individuals surveyed—consistent with what the previous research has indicated, both in the Portuguese context and in other surrounding countries. However, the reasons behind this valuation have shifted over time. In earlier periods—extending up to the late 1980s in Portugal—this valuation was primarily grounded in meritocratic ideals related to social mobility and achievement. These ideals presupposed familial relationships that were more sacrificial, positional, and hierarchical, as well as more integrative. Since that time, however, other motives have gained prominence—ones that are more convivial and expressive in nature, though still associated with personal development and achievement. These motives emerge within the context of closer, more affective, hedonistic, and liberating families’ relationships that are also increasingly individualistic and egalitarian. This shift explains the contemporary valuation of the family, as demonstrated in this research, in which respondents particularly appreciate these newer aspects of family life.

Although respondents still consider religion an important component of family life, they do so at significantly lower rates compared to the importance attributed to other dimensions, such as the transmission of values, emotional support, education and guidance, or cohabitation and leisure. This represents a clear illustration of the secularization process in Portuguese society, highlighting that families’ values and relationships are increasingly less mediated by the religious sphere.

All of this indicates the significant value shift that Portuguese society has experienced over recent decades—a shift recognized by the vast majority of respondents. However, this transformation tends to elicit moderate responses: most people believe that the change in families’ values has not necessarily resulted in the improvement of all social conditions. They tend to appreciate aspects of both present-day and past societies. Members of intermediate generations are the most likely to hold this view. While they lean more toward modern values—having been socialized in a fully democratic society since their youth—their memories also contain traces of a childhood and early adolescence spent in traditional communities. As a result, these individuals have been more involved in the reconfiguration of traditional values in light of modern ones—and vice versa. Unlike those over 65 years old, for whom traditional values play a greater role in shaping this reconfiguration, and unlike younger generations, whose identities have been shaped exclusively by modern values, members of these intermediate generations face value change with greater reflection and critical distance. This critical awareness is also evident in how they perceive the concrete, practical challenges confronting contemporary families.

When asked to identify “the three biggest challenges families face today,” respondents’ concerns are clearly prioritized. Work-life balance emerges as the most significant challenge, followed by a lack of family time and the excessive influence of technology. These three concerns are cited more frequently than economic difficulties and the transmission of values, or social and cultural pressures.

The prominence of work-life balance points to a structural tension in contemporary Portuguese society. The increasing demands of the labor market—in terms of hours, flexibility, and performance—often clash with the time, care, and attention required by the family sphere. This reveals a widespread difficulty in harmonizing these two fundamental aspects of daily life. Closely related to this is the lack of family time. This finding suggests that even when responsibilities are managed, a persistent feeling of insufficient quality time together remains, a problem exacerbated by daily commutes, multiple extracurricular activities, and household chores that erode available time.

The third most cited challenge, the excessive influence of technology, is a relatively recent phenomenon with a considerable impact. It is frequently identified as an obstacle to interpersonal communication and family cohesion, with particular concern for its effects on the healthy development of younger generations.

These challenges are perceived most strongly by individuals with caregiving and educational responsibilities, who have observed how the technological realm has disrupted the temporal and spatial structures that once supported family life and enabled socialization processes. These individuals are especially aware of the increasing complexity of such processes.

Our research also demonstrates that the family remains one of the most valued institutions because it continues to serve as a fundamental structure for education and socialization—without which the reproduction of society would not be possible. However, these processes currently face significant challenges, particularly those stemming from the dominance of productive life over reproductive life. This imbalance has led to the outsourcing of the family’s socializing functions, even though such functions inherently require dedicated time and space for cohabitation and shared experience.

In this context, new communication technologies pose additional challenges, as they further fragment the times and spaces that structure family life and enable the reproduction of society. Respondents are aware of these difficulties because they confront them in their daily lives.

In short, this research shows that the family remains a fundamental and irreplaceable institution for the continuity of societies. However, it is now confronted by serious challenges—challenges that cannot be adequately addressed without the necessary support and collaboration of public institutions.