A Study of Spiritual Expression in Totemic Art: Based on a Multidimensional Analysis of Sublime Beauty, Humanistic Beauty and Artistic Beauty

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Totemism, Totemic Art and Spiritual Expression

2.1. Totemism

1. Primitive peoples’ social groups give names to specific animals and plants because they think they are the group’s ancestors or are blood relatives. 2. The group’s members hold the animals and plants that represent the totem ancestors in high regard, and nobody dares to kill, maim, or otherwise damage them. There is a specific penalty for breaking this regulation. 3. People who belong to the same totem group share the same views about the totem and can be considered a full community. The same totem beliefs are expressed in the same way via body ornaments, everyday kitchenware, and cemetery and home decorations. 4. After reaching a certain age, men and women participate in a totem initiation rite. Furthermore, an absolute exogamy system is in place, and marriage between men and women in the same totem group is forbidden.

2.2. Totemic Art

Totemism, on the one hand, promoted the emergence of artistic forms and standardized existing ones, thereby enhancing their expressiveness and appeal. On the other hand, it gradually freed primitive people from their natural state and led them to transition to a social state, creating the preconditions for human aesthetic activities.

Totems and taboos significantly impact the evolution of aesthetics. This influence can be categorized into two components. The initial aspect is practical: totemism directly contributed to the development of various art forms linked to this belief system, or to the standardization of pre-existing art forms. The alternative is spiritual. If totem taboos were the earliest legal codes for humanity, they would undoubtedly have a significant impact on the human spirit. This initial code of laws transformed barbarians from a natural condition into a moral condition, facilitating the progression to an aesthetic condition.

2.3. The Spiritual Expression of Totemic Art

3. The Sublime Beauty of Totemic Art: Reverence for Life and the Sacred

3.1. The Beast-Face Patterns on Chinese Bronze Ware

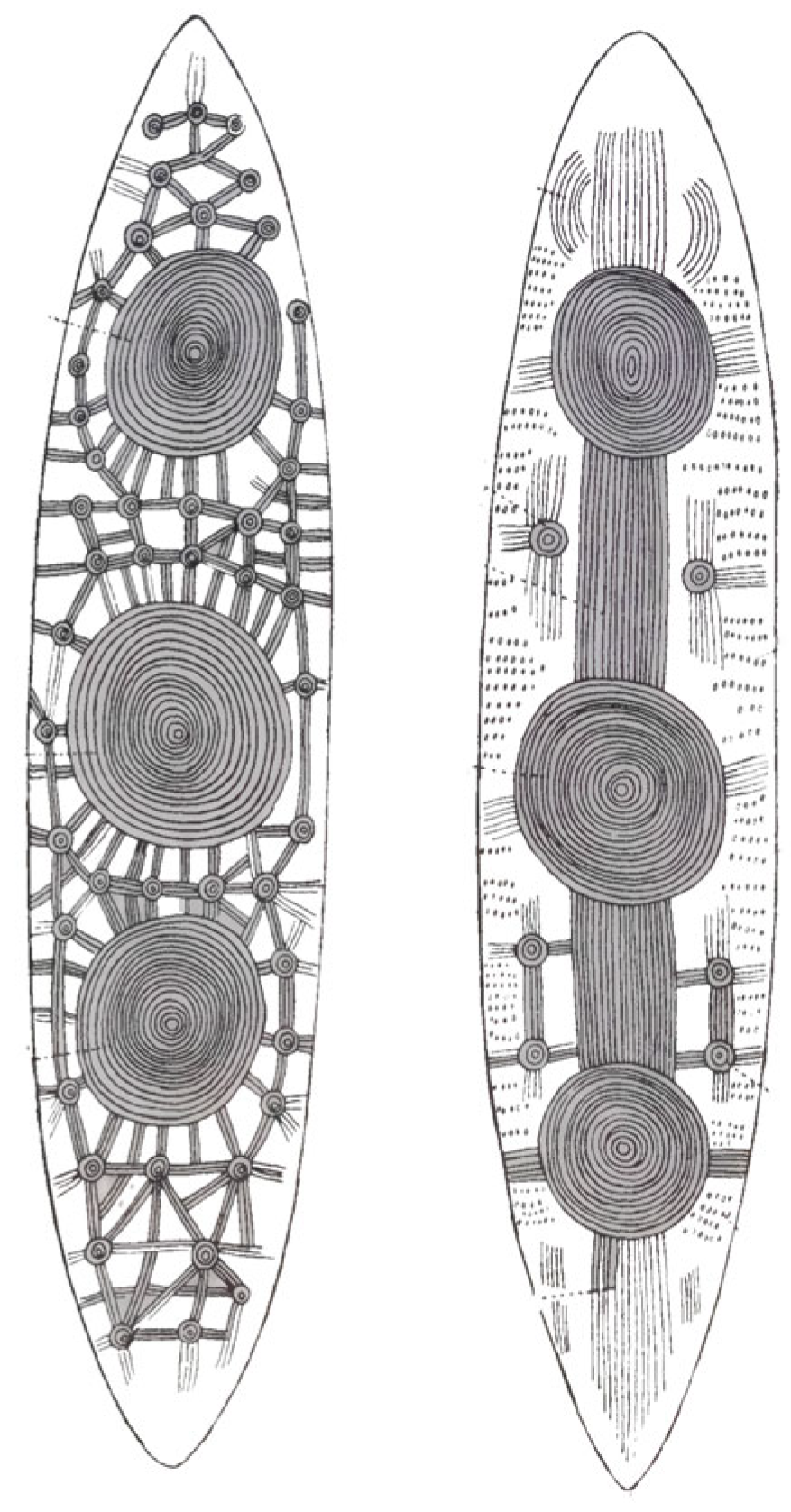

3.2. The Churinga, a Sacred Object of the Australian Aborigines

3.3. Sublime: Presenting the Unpresentable

4. The Humanistic Beauty of Totemic Art: The Awakening and Transcendence of Individual and Collective Consciousness

4.1. Three Expressions of Humanistic Beauty in Totemic Art

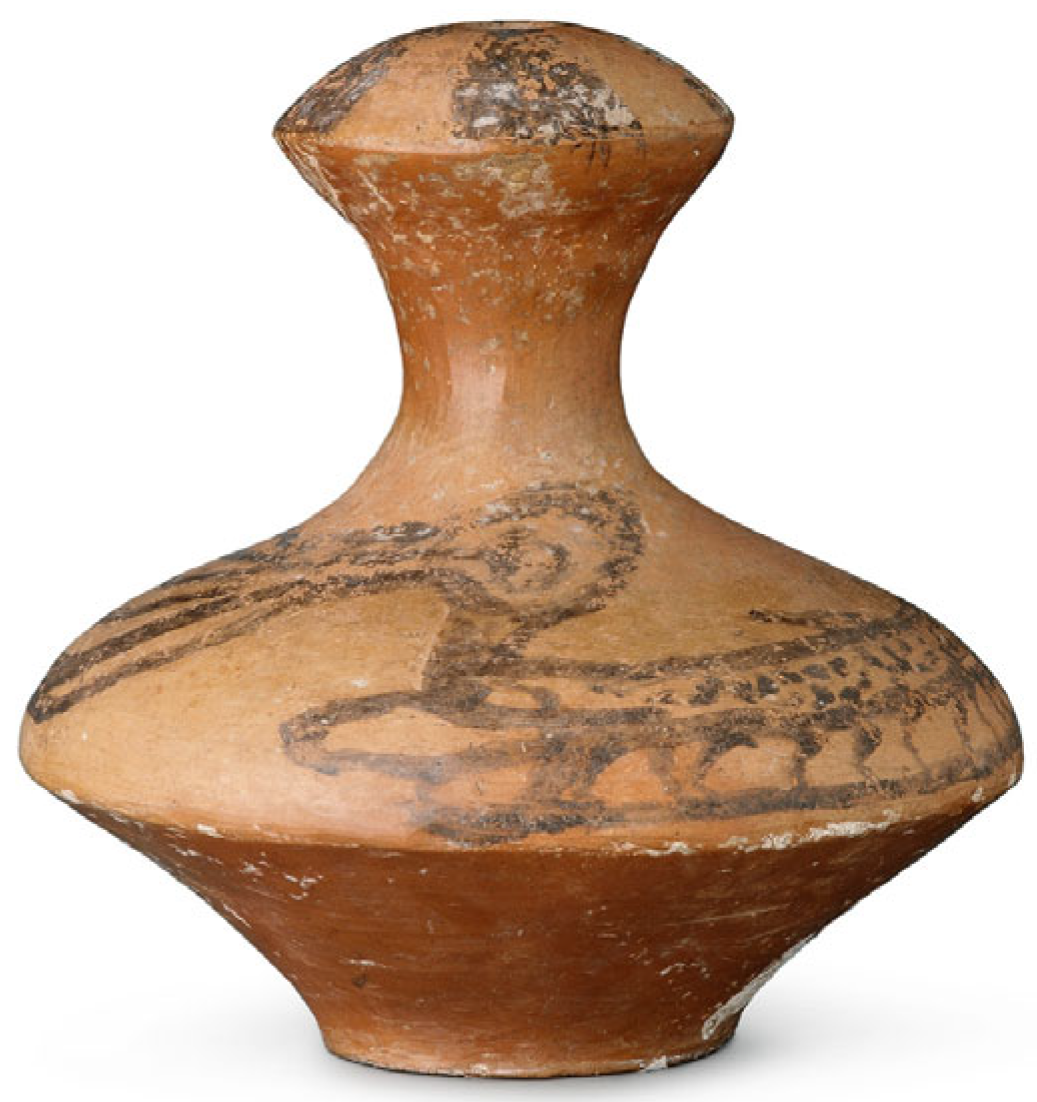

4.2. Human-Faced Fish Pattern Painted Pottery Basin

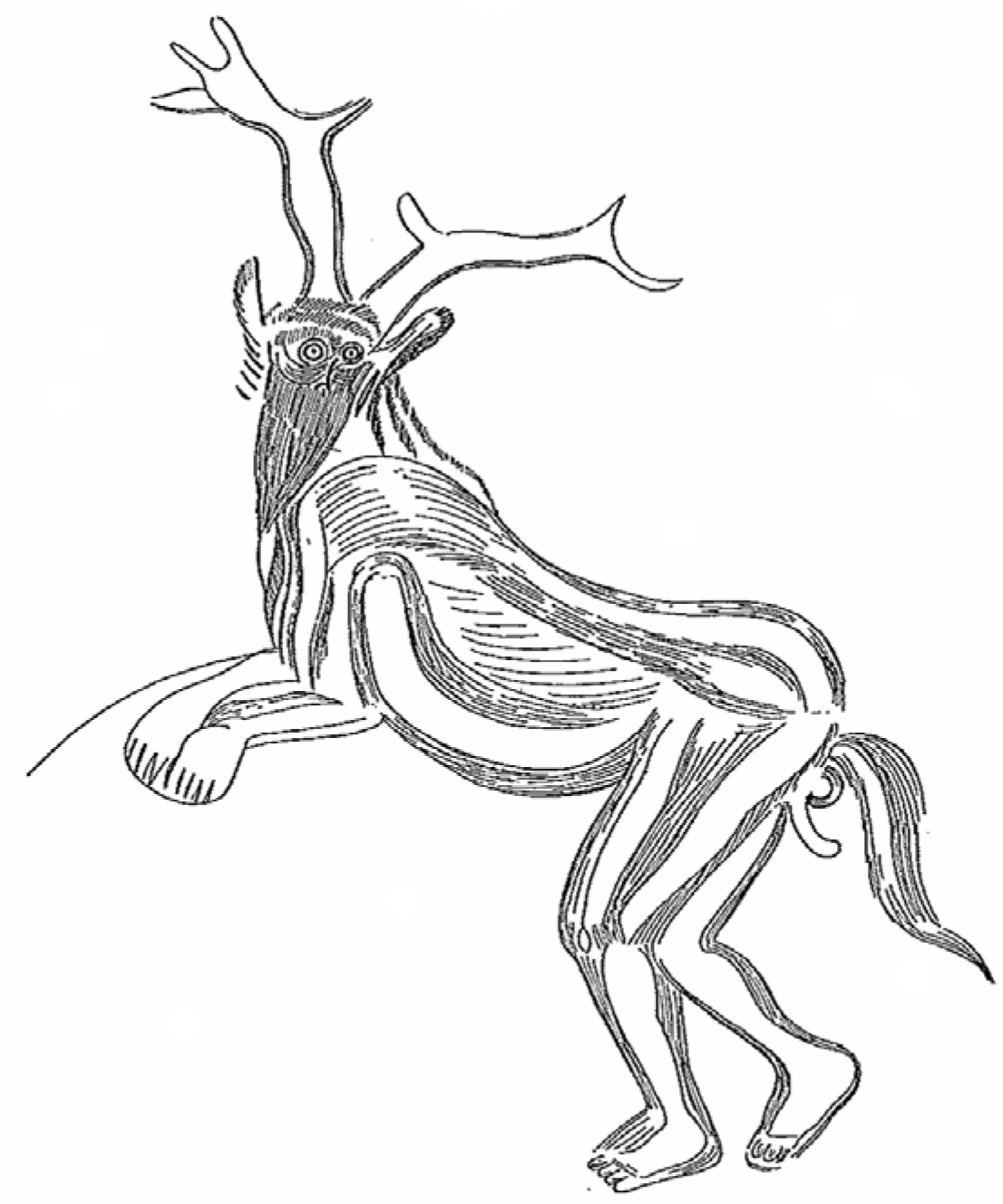

4.3. Sorcerer Rock Paintings in the Trois Frères Caves in France

5. The Artistic Beauty of Totemic Art: The Spiritual Essence Behind Totemic Artistic Style and Anti-Aesthetic Tendencies

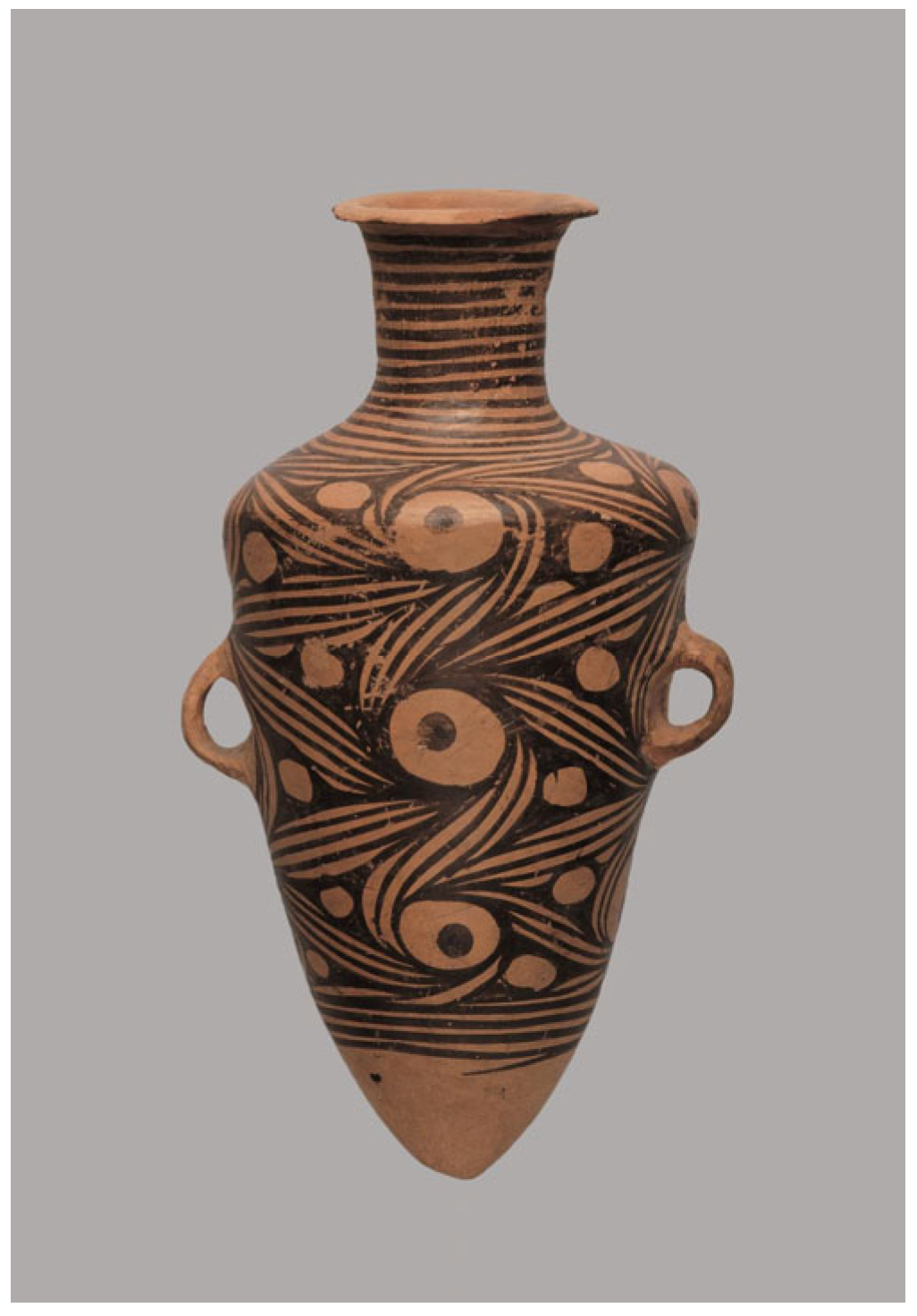

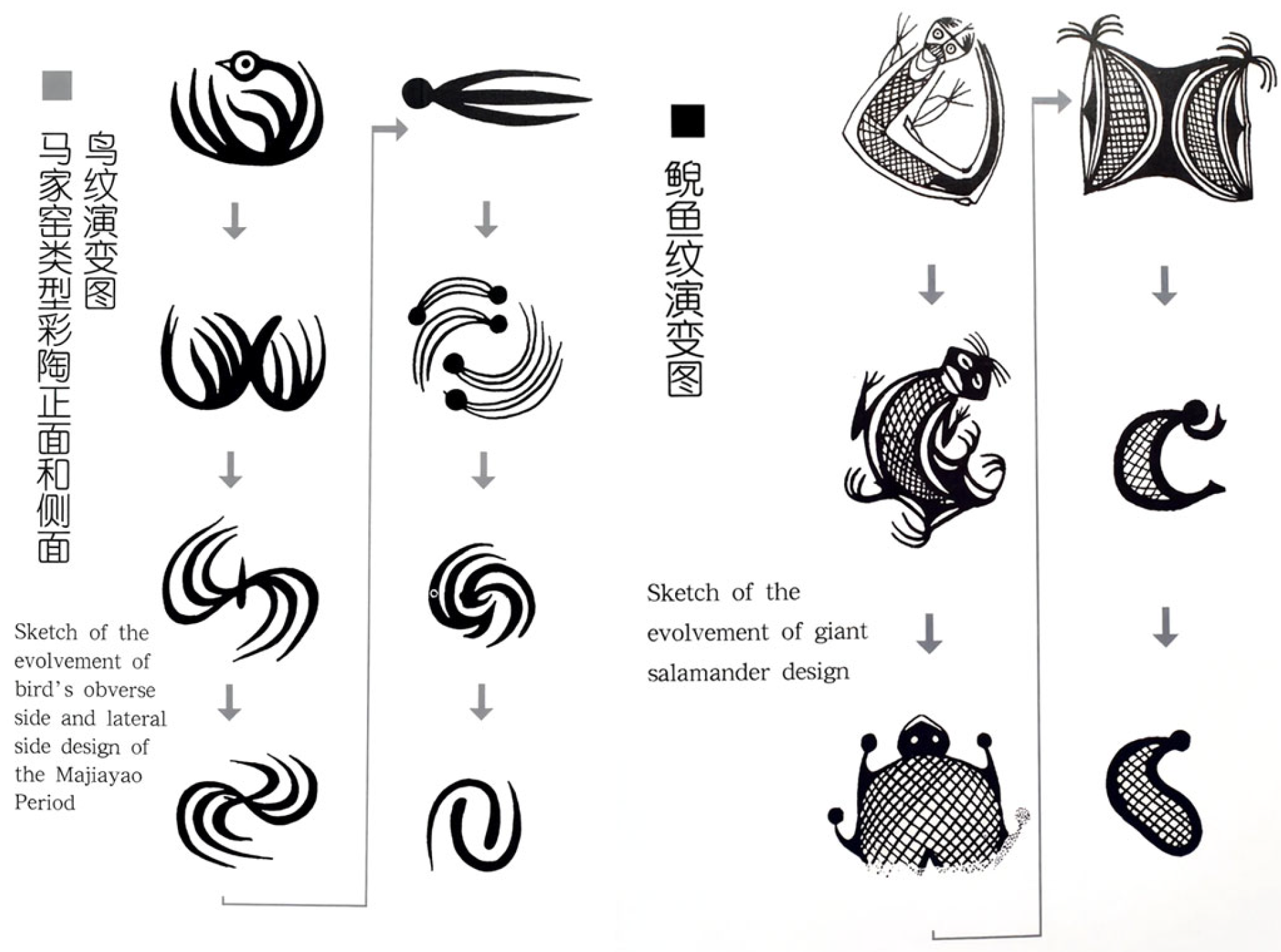

5.1. Style Evolution: From Concrete Imitation to the Spiritual Ascension of Abstract Symbols

5.2. Utilitarianism and “Anti-Aesthetics”: The Functional Construction of Sacred Systems

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | In Chinese academics, “tu teng chong bai 圖騰崇拜” is translated in a variety of ways; the most common translations are “totemism,” “totem system,” “totem culture,” “totem worship,” The term “totemism” is the more widely used translation. See (He 1991, p. 16). |

| 2 | The exogamy system forbids both sexual relations and marriages between men and women in the same clan. |

| 3 | Different opinions are held by the ethnologists represented by Rivers and Frazer, who see totemism as a system of social organization, the Soviet anthropologists represented by Zolotarev, who see it as a form of religion, and the ethnologists represented by Rivers, who see totemism as a semi-social and semi-religious system. See (Khaytun 2004, pp. 2–4). |

| 4 | The source of the text is the website of the National Museum of China: http://www.chnmuseum.cn (accessed on 27 June 2025). |

| 5 | https://www.chnmuseum.cn/zp/zpml/kgfjp/202008/t20200824_247218.shtml (accessed on 27 June 2025). |

| 6 | https://www.chnmuseum.cn/zp/zpml/kgfjp/202107/t20210719_250709.shtml (accessed on 27 June 2025). |

| 7 | The Majiayao Culture is named after the village of Majiayao in Linxian County, Gansu Province, where it was first discovered in 1923. It is primarily distributed along the tributaries of the Yellow River, including the Tao River, Daxia River, and Huangshui River. The Majiayao Culture was first discovered by Swedish archaeologist Johan Gunnar Andersson in Majiayao Village, Linxian County, Gansu Province, in 1923. Based on modern scientific dating methods, the Majiayao Culture dates back approximately 5000 years and is generally considered to be a late Neolithic culture. A prominent feature of the Majiayao culture is the highly developed painted pottery found among its ceramics. Painted pottery is the most representative artifact of the Majiayao culture. The painted decorations are intricate and varied, and the painting techniques have reached a high level of maturity. In the Majiayao cultural sites, numerous pottery-making remains have been discovered. The painted pottery of the Majiayao type is predominantly orange, yellow, and black in color, with animal motifs such as birds, fish, and frogs painted on bowls, basins, bottles, and jars. Additionally, geometric patterns such as hanging curtains, swirls, water waves, grass leaves, and triangles are also present. The pottery of the Majiayao culture features richly painted patterns and various engraved symbols. The interpretation of these patterns and symbols is also a hot topic in academic circles today. The content of these patterns may reflect the religious beliefs, spiritual emotions, and aspirations of ancient people toward real life in many ways. For example, do frog patterns reflect the ancient people’s worship of fertility and concern for human reproduction? Natural motifs like landscapes may reflect the ancient people’s understanding, reverence, and worship of the natural world; the depictions of groups of people dancing on pottery—were these ordinary recreational activities or ritualistic ceremonies to entertain the gods? In summary, the discovery of the Majiayao Culture is a landmark event in Chinese archaeological history, filling a significant gap in China’s early history. See (Du 2003). |

| 8 | http://www.gansumuseum.com/detailsPage?nav=0-0&id=1670 (accessed on 27 June 2025). |

References

- Abadía, Oscar Moro. 2006. Art, crafts and Paleolithic art. Journal of Social Archaeology 6: 119–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balfour, Henry. 1893. The Evolution of Decorative Art: An Essay upon Its Origin and Development as Illustrated by the Art of Modern Races of Mankind. London: Percival & Company. [Google Scholar]

- Bataille, Georges. 1955. Prehistoric Painting: Lascaux or the Birth of Art. Geneva: Editions D’Art Albert Skira. [Google Scholar]

- Boas, Franz. 1922. Primitive Art. New York: Dover Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Cen, Jiawu 岑家梧. 1986. Tu Teng Yi Shu Shi 圖騰藝術史 (History of Totemic Art). Shanghai: Xue Lin Chu Ban She 學林出版社 (Xue Lin Publishing House). [Google Scholar]

- Central Academy of Fine Arts, Department of Chinese Art History 中央美術學院美術史系中國美術史教研室. 2002. Zhong Guo Mei Shu Jian Shi 中國美術簡史 (A Brief History of Chinese Art). Beijing: Zhong Guo Qing Nian Chu Ban She 中國青年出版社 (China Youth Press). [Google Scholar]

- Du, Doucheng 杜鬥城. 2003. Yuan Gu Wen Ming Zhi Guang—Ma Jia Yao Wen Hua遠古文明之光——馬家窯文化 (The Light of Ancient Civilization: The Majiayao Culture). Gan Su Ri Bao 甘肅日報 (Gansu Daily). Available online: https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s?__biz=MjM5MjUzMjQ3Ng==&mid=2651850883&idx=1&sn=3447878339866ff599a8874ae641d250&chksm=bd407a108a37f306b4b3bd85a431bb26196214ecf3e67cc6738823a410e677171c34394d0a04&scene=27 (accessed on 27 June 2025).

- Durkheim, Emile. 1995. The Elementary Forms of Religious Life. Translated by Karen E. Fields. New York: The Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dutton, Denis. 1995. The Aesthetics of Primitive Art. The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 53: 321–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Errington, Shelly. 1994. What Became Authentic Primitive Art? Cultural Anthropology 9: 201–26. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/656240 (accessed on 27 June 2025). [CrossRef]

- Feuerbach, Ludwig. 2019. Das Wesen der Religion (The Essence of Religion). Leipzig: Evangelische Verlagsanstalt GmbH (Gospel Publishing House Ltd.). [Google Scholar]

- Frazer, James George. 1887. Totemism. Edinburgh: Adam & Charles Black. [Google Scholar]

- Frazer, James George. 1913. The Golden Bough: A Study of Magic and Religion Part VII Balder the Beautiful VOL. II. London: Macmillan and Co., Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Qiang 高強. 1984. Jiang Zhai Shi Qian Ju Min Tu Teng Chu Tan 姜寨史前居民圖騰初探 (A Preliminary Study of the Totems of the Prehistoric Residents of Jiangzhai). Shi Qian Yan Jiu 史前研究 (Prehistoric Studies) 1: 63–67. [Google Scholar]

- Grosse, Ernst. 1996. Yi Shu De Qi Yuan 藝術的起源 (The Beginnings of Art). Translated by Muhui Cai. Beijing: Shang Wu Yin Shu Guan 商務印書館 (The Commercial Press). [Google Scholar]

- Hang, Chunxiao 杭春曉. 2009. Shang Zhou Qing Tong Qi Zhi Tao Tie Wen Yan Jiu 商周青銅器之饕餮紋研究 (A Study of Beast-Face Patterns on Shang and Zhou Bronze Ware). Beijing: Wen Hua Yi Shu Chu Ban She 文化藝術出版社 (Cultural Arts Publishing House). [Google Scholar]

- Harrison-Buck, Eleanor, and David A. Freidel. 2021. Reassessing Shamanism and Animism in the Art and Archaeology of Ancient Mesoamerica. Religions 12: 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Xingliang 何星亮. 1991. Tu Teng Wen Hua Yu Ren Lei Zhu Wen Hua De Qi Yuan 圖騰文化與人類諸文化的起源 (Totem Culture and the Origin of Human Cultures). Beijing: Zhong Guo Wen Lian Chu Ban Gong Si 中國文聯出版公司 (China Federation of Literary and Art Circles Publishing Company). [Google Scholar]

- He, Xingliang 何星亮. 2008. Tu Teng Yu Zhong Guo Wen Hua 圖騰與中國文化 (Totem and Chinese Culture). Nanjing: Jiang Su Ren Min Chu Ban She 江蘇人民出版社 (Jiangsu People’s Publishing House). [Google Scholar]

- Hegel, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich. 1975. Aesthetics: Lectures on Fine Art Volume I. Translated by Thomas Malcolm Knox. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kant, Immanuel. 1987. Critique of Judgment. Translated by Werner S. Pluhar. Indianapolis and Cambridge, MA: Hackett Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Khaytun, David Efimovich. 2004. Tu Teng Chong Bai 圖騰崇拜 (Totemism). Translated by Xingliang He. Guilin: Guang xi Shi Fan Da Xue Chu Ban She 廣西師範大學出版社 (Guangxi Normal University Press). [Google Scholar]

- Langer, Susanne K. 2006. Yi Shu Wen Ti 藝術問題 (Problems of Art). Translated by Shourao Teng. Nanjing: Nan Jing Chu Ban She 南京出版社 (Nanjing Publishing House). [Google Scholar]

- Lévi-Strauss, Claude. 1962. Totemism. Translated by Rodney Needham. London: Merlin Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lévy-Bruhl, Lucien. 1966. How Natives Think. Translated by Lilian A. Clare. New York: Washington Square Press, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Dunyuan 劉敦願. 2001. Liu Dun Yuan Wen Ji 劉敦願文集 (Collected Works of Liu Dunyuan). Beijing: Ke Xue Chu Ban She 科學出版社 (Science Press). [Google Scholar]

- Lyotard, Jean-Francois. 1991. The Inhuman: Reflections on Time. Translated by Geoffrey Bennington, and Rachel Bowlby. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Marx, Karl, and Frederick Engels. 1969. Karl Marx and Frederick Engels Selected Works in Three Volumes. Vol. 1. Moscow: Progress Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- McLennan, John Ferguson. 1869. The Worship of Animals and Plants. The Fortnightly Review 7: 194–216. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, Lewis Henry. 1964. Ancient Society. Chicago: Charles H. Kerr & Company. [Google Scholar]

- Ochoa, Blanca. 2018. From Totems to Myths: Theorising about Rock Art. Antiquity 92: 816–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacio-Pérez, Eduardo. 2012. The Origins of the Concept of “Palaeolithic Art”: Theoretical Roots of an Idea. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory 20: 682–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plate, S. Brent. 2005. Walter Benjamin, Religion, and Aesthetics: Rethinking Religion Through the Arts. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Plekhanov, Georgi Valentinovich. 1962. Pu Lie Han Nuo Fu Zhe Xue Zhu Zuo Xuan Ji 普列漢諾夫哲學著作選集 (Selected Philosophical Works of Plekhanov). Translated by Xin Ru, Kuang He, and Ruoshui Liu. Shanghai: Sheng Huo·Du Shuo·Xin Zhi San Lian Shu Dian 生活·讀書·新知三聯書店 (Life-Reading-New Knowledge Triad Bookstore). [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, Zhensheng 丘振聲. 1994. Tu Teng Chong Bai Yu Shen Mei Yi Shi 圖騰崇拜與審美意識 (Totemism and Aesthetic Consciousness). Min Zu Yi Shu 民族藝術 (Ethnic Art) 4: 73–91. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer, Baldwin, and Francis James Gillen. 1904. The Northern Tribes of Central Australia. New York: The Macmillan Company. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer, Baldwin, and Francis James Gillen. 1968. The Native Tribes of Central Australia. New York: Dover Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Tănase, Alexandru. A. 1984. Wen Hua Yu Zong Jiao 文化與宗教 (Culture and Religion). Translated by Weida Zhang. Beijing: Zhong Guo She Hui Ke Xue Chu Ban She 中國社會科學出版社 (China Social Sciences Press). [Google Scholar]

- Tylor, Edward Burnett. 1871. Primitive Culture: Researches into the Development of Mythology, Philosophy, Religion, Art, and Custom. Vol. 1. London: John Murray. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Wenjin 王文錦. 2016. Li Ji Yi Jie 禮記譯解 (Interpretation of the Rituals). Beijing: Zhong Hua Shu Ju 中華書局 (Zhonghua Book Company). [Google Scholar]

- Worsley, Peter Maurice. 1955. Totemism in a Changing Society. American Anthropologist 57: 851–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Zhongtian 易中天. 1992. Yi Shu Ren Lei Xue 藝術人類學 (Art Anthropology). Shanghai: Shang Hai Wen Yi Chu Ban She 上海文藝出版社 (Shanghai Literary Publishing House). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Shengbing 張勝冰. 2004. Cong Tu Teng Yi Shu Kan Mei Xue Guan Nian De Yan Bian 從圖騰藝術看美學觀念的演變 (The Evolution of Aesthetic Concepts from Totemic Art). Zhong Guo Hai Yang Da Xue Xue Bao (She Hui Ke Xue Ban) 中國海洋大學學報(社會科學版) (Journal of Ocean University of China ‘Social Science Edition’) 2: 62–65. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Shiying 張世英. 2007. Jing Jie Yu Wen Hua: Cheng Ren Zhi Dao 境界與文化——成人之道 (Realm and Culture: The Way of Adulthood). Beijing: Ren Min Chu Ban She 人民出版社 (People’s Publishing House). [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Chunqing 趙春青. 2000. Cong Yu Niao Xiang Zhan Dao Yu Niao Xiang Rong: Yang Shao Wen Hua Yu Niao Cai Tao Tu Shi Xi 從魚鳥相戰到魚鳥相融──仰韶文化魚鳥彩陶圖試析 (From Fish-Bird War to Fish-Bird Integration: A Study of Fish-Bird Painted Pottery Patterns in Yangshao Culture). Zhong Yuan Wen Wu 中原文物 (Cultural Relics of the Central Plains) 2: 13–15. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Yuanzhe 鄭元者. 1992. Tu Teng Mei Xue Yu Xian Dai Ren Lei 圖騰美學與現代人類 (Totemic Aesthetics and Modern Humanity). Shanghai: Xue Lin Chu Ban She 學林出版社 (Xue Lin Publishing House). [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Cunming 朱存明. 2002. Tu Teng·Tu Xiang·Fang Xiang—Lun Shi Jue Wen Hua De Li Shi Fan Xing 圖騰·圖像·仿像——論視覺文化的歷史範型 (Totem–Image–Imitation–On the Historical Paradigm of Visual Culture). Wen Xue Qian Yan 文學前沿 (Literary Frontiers) 1: 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Di 朱狄. 1988. Yuan Shi Wen Hua Yan Jiu-Dui Shen Mei Fa Sheng Wen Ti De Si Kao 原始文化研究——對審美發生問題的思考 (Primitive Cultural Studies—Reflections on the Problem of Aesthetic Occurrence). Shanghai: Sheng Huo·Du Shuo·Xin Zhi San Lian Shu Dian 生活·讀書·新知三聯書店 (Life-Reading-New Knowledge Triad Bookstore). [Google Scholar]

- Zuo, Qiuming 左丘明. 2012. Zuo Zhuan Xia Ce 左傳 下冊 (Zuo Zhuan Volume II). Translated by Dan Guo, Xiaoqing Cheng, and Binyuan Li. Beijing: Zhong Hua Shu Ju 中華書局 (Zhonghua Book Company). [Google Scholar]

| Performance Dimensions | Chinese Archaeological Evidence | Western Archaeological Evidence | Common Essence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nature worship | Records of mountain and river worship in oracle bone inscriptions | Stonehenge healing worship, Greek Dionysus natural rituals | Personification and ritualization of natural phenomena |

| Ancestral spirits | Human sacrifice system in Yinxu, ancestor worship in bronze inscriptions of the Zhou dynasty | Mycenaean shaft grave burial goods, Roman household guardian altar | The soul of the deceased continues to exist and influence the living |

| Witchcraft practices | Shang Dynasty bronze vessel casting rituals, oracle bone divination system | Cave hunting witchcraft ruins, Mediterranean harvest rituals | Interaction between humans and spirits through rituals |

| Spirit vessels | Bronze ritual vessels from the Shang and Zhou dynasties as mediums for communication with the spirits | As a sacred object, the Churinga Flint as the “stone of the soul” | Certain substances contain spiritual power |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yan, Z.; Su, Z. A Study of Spiritual Expression in Totemic Art: Based on a Multidimensional Analysis of Sublime Beauty, Humanistic Beauty and Artistic Beauty. Religions 2025, 16, 1148. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16091148

Yan Z, Su Z. A Study of Spiritual Expression in Totemic Art: Based on a Multidimensional Analysis of Sublime Beauty, Humanistic Beauty and Artistic Beauty. Religions. 2025; 16(9):1148. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16091148

Chicago/Turabian StyleYan, Zhilong, and Zhiheng Su. 2025. "A Study of Spiritual Expression in Totemic Art: Based on a Multidimensional Analysis of Sublime Beauty, Humanistic Beauty and Artistic Beauty" Religions 16, no. 9: 1148. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16091148

APA StyleYan, Z., & Su, Z. (2025). A Study of Spiritual Expression in Totemic Art: Based on a Multidimensional Analysis of Sublime Beauty, Humanistic Beauty and Artistic Beauty. Religions, 16(9), 1148. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16091148