1. Introduction

The twentieth century witnessed Toru Takemitsu’s emergence as a major Japanese composer whose works blend Western avant-garde elements with traditional Japanese aesthetics. Scholars agree that Takemitsu found deep spiritual meaning in Kenzaburō

Ōe’s (

1980) short story “

The Clever Rain Tree”

1, which reshaped his understanding of sacred creation in the piano work

Rain Tree Sketch (

Burt 2001;

Enomoto 1995;

Wang,

2024). Ōe’s short story uses a single image—the rain tree whose leaves store water and drip slowly—to stage care, renewal, and continuity; this is the metaphor Takemitsu draws on.

According to our research, the transformation of Ōe Kenzaburō’s literary vision into Takemitsu’s sacred soundscape represents one of the most compelling examples of cross-media spiritual expression in contemporary music. The term sacred soundscape, as used here, means a musical environment that combines natural images with meditative temporal elements and symbolic transcendence to produce spiritual awareness and contemplative states. Spiritual practice denotes a repeatable pattern of listening and performance that cultivates inward attention and ethical calm. Transcendental experience refers to an episode of heightened awareness of silence, time, and relation that cannot be reduced to concepts. The sacred names the set-apart quality of that experience in which ordinary sound takes on more-than-ordinary meaning. According to most scholars of his music, Takemitsu achieved two important things: he developed sophisticated compositional techniques and created sacred spaces that facilitated spiritual connection and self-reflection. These spaces evoke fundamental spiritual experiences through their connection to Japanese aesthetic traditions (

Koozin 2002;

Burt 2001;

Hara 2020).

The work uses the “rain tree” image as a cosmic metaphor to convey its central message. The tree functions as a spiritual bridge between earth and heaven, demonstrating the ongoing cycle of spiritual development. According to Ōe’s literary understanding, the “clever” tree uses its many leaves to collect water and drip it down, maintaining a continuous cycle of moisture that symbolizes the never-ending flow of spiritual energy (

Enomoto 1995). The imagery offered an ideal metaphorical medium for Takemitsu to explore the interplay of musical abstraction with spiritual experience, of sound with silence, and of time with eternity.

This research begins with an examination of Takemitsu’s spiritual foundations through his aesthetic philosophy and continues with an analysis of how Ōe’s literary images become musical metaphors. It then studies the specific compositional methods that bear transcendent meaning and finally examines how modern multimedia visualization, used only as a supportive medium, can either heighten or distract from those spiritual aspects. The goal is to understand how abstract musical elements can convey deep spiritual meaning and transformative power for individual listeners. This article employs three analytical frameworks to investigate how spiritual content travels between artistic forms.

Section 2 and

Section 3 establish the first framework by moving from Ōe’s literary symbolism to Takemitsu’s musical language and showing how Zen aesthetics and

shizen act as philosophical connectors for cross-media spiritual transformation.

Section 4 and

Section 5 analyze Takemitsu’s musical composition through a systematic investigation of techniques that materialize spirituality, focusing on the use of

ma (emptiness) as temporal organization and on the development of water imagery through motivic progression and textural change.

Section 6 is based on the software Synesthesia-2 (2014 version) to propose and design a visualization concept for

Rain Tree Sketch. By translating the acoustic characteristics of different passages in

Rain Tree Sketch into specific visual logic, it establishes simulation techniques to concretize the imagery of water and

ma. The conclusion and discussion section presents the core findings of this study regarding Toru Takemitsu’s

Rain Tree Sketches, and then illustrates its theoretical contribution to cross-media aesthetic communication through comparative analysis with existing research, and further discusses the potential and risks of digital visualization technology. Finally, the study’s limitations are systematically identified, and future research directions are proposed details perspectives.

2. “Nature” (Shizen) as Sacred Principle

Toru Takemitsu positions the concept of “nature” (shizen) as the cornerstone of his musical aesthetics, functioning both as a spiritual foundation for creation and as an aesthetic principle. The meaning of “nature” in Takemitsu’s music emerges when one understands the Japanese cultural sense of the concept and how it acquires modern musical significance.

The traditional Japanese cultural framework, while transformed by modernization, maintains a distinctive approach to the relationship between humans and nature that differs from Western post-Enlightenment perspectives (

Karatani 1993). In contemporary Japan,

shizen is rooted in the country’s aesthetic and philosophical heritage. The Japanese framework forms a continuous bond between human beings and their natural surroundings that contrasts with Western traditions that tend to separate these elements. The Daijisen Dictionary (

Matsumura,

1998) defines the term as follows:

The world of mountains, rivers, grasslands, trees, all those things that do not include humans, and those things that are not created by humans.

Everything between heaven and earth, including humans. The universe.

In

shizen, the artist treats nature as a partner in making. The artist works with the given behavior of materials rather than forcing them. In music, this means following resonance, decay, and timbre instead of steering sound toward a fixed goal. This stance resists a strict subject to object split (

Hayakawa 1973). It can support contemplative experience because it reduces the felt gap between maker, medium, and world and directs attention to how sound arises and fades. Nature functions as a fundamental principle in Zen art, according to the Zen scholar Shin’ichi Hisamatsu, because it includes both the natural environment that lacks human-made elements and the entire universe that contains humanity. The seemingly contradictory perspective directs people toward spiritual awakening by dissolving distinctions between artists and their artwork (

Hisamatsu 1971).

Japanese garden design offers a clear example of shizen aesthetics. It establishes a natural environment that appears as if nature itself had opened the space, although it is human-made. This gardening philosophy represents the central meaning of “nature” as an aesthetic principle. Architect Masao Hayakawa explains in his foundational study:

“Japanese gardens are places where the human heart can come into direct, pure contact with the world of plants and flowers. One of their fundamental intentions is to inspire the emotion of rejoicing with these creations of nature and of figuratively blooming when they bloom”.

Shizen aesthetics aims for artless art. This requires advanced technique to make something look completely natural.

The “nature” principle reaches its highest philosophical level in Zen temple gardens (such as Ryōan-ji), which serve as the ultimate manifestation of Japanese garden art. Dry-landscape gardens use minimal components such as white sand and stones to generate images of mountains, rivers, and seas that reveal boundless possibilities within limited space. The spiritual essence of this form uses abstract signs to help viewers grasp the core of nature. The garden avoids exact reproduction of natural scenes (

Ronnen 2013).

Through the technique of “borrowed scenery,” Japanese gardens demonstrate a unique relation to nature. Designers incorporate mountains and trees by using strategic arrangements to unite human-made structures with natural elements. The artistic significance of this method lies in its refusal to possess nature as a physical object; instead, it builds a dialogical connection with nature through artistic interpretation. In this sacred domain, human beings encounter nature in a space that transcends the notion of human domination over the natural world.

Japanese garden aesthetics deeply inspired Takemitsu’s composition through his knowledge of these gardens. He viewed shizen as more than an aesthetic concept; it represented a spiritual approach within the process of musical composition. His widely cited musical metaphor offers insight:

“My music is like a garden, and I am the gardener. Listening to my music can be compared to walking through a garden and experiencing the changes in light, pattern, and texture”.

Through this garden metaphor, composing and listening work as repeatable acts of focused attention. These acts shape meditative listening spaces. Here, sacred denotes a set-apart attentional space in which ordinary sound takes on more-than-ordinary meaning. The garden–music concept manifests at three levels.

First, the creative process unfolds “naturally,” like a living organism. The gardener avoids mechanical, predetermined blueprints and instead follows the natural growth of plants; the garden takes shape through interaction with nature. By “natural,” Takemitsu means that he lets sound’s own properties—resonance, decay, and timbre—suggest the next event. He follows local relations instead of steering toward a fixed goal. In this sense, development arises from listening into the material rather than forcing it. As he wrote,

“My music aims to exist as the natural law... I refuse to handle sound to lead it toward a singular objective. Instead I strive to release the sound to its maximum potential.”

Second, the structure is nonlinear. The strolling layout of Japanese gardens provides visitors with multiple paths and perspectives. Takemitsu developed this spatial design concept into an art that unfolds over time. The musical development in Rain Tree Sketch avoids the teleological structures of Western classical music, offering listeners multiple possible paths through the music. Each musical segment attains some independence while maintaining an organic relation to the whole.

Third, with limited elements, Japanese gardens produce limitless artistic conception that encourages imagination and exploration. Takemitsu’s music explores the territory of words that have been used up but whose meanings remain open. In Rain Tree Sketches, the combination and development of basic musical elements yield layered sound imagery and a quiet, attentive listening space shaped by sustained tones, registral gaps, and rests.

3. Sacred Symbolism of the Cosmic Tree

“The Clever Rain Tree” by Kenzaburō Ōe articulates a spiritual cosmology that underlies Toru Takemitsu’s musical composition. The literary image functions beyond its narrative role to establish a spiritual bridge between music and literature. The rain tree thus operates as an archetypal cosmic tree, or axis mundi, with deep cosmological meaning within Ōe’s literary universe.

According to Oe’s novel description the “ingenious tree” contains “hundreds of thousands of tiny leaves—finger-like” that “store up moisture while other trees dry up at once” (

Ōe 1980, p. 4). The botanical description serves as a metaphor for spiritual strength, showing that the rain tree remains connected to transcendent nourishment sources when material and spiritual resources become depleted. The rain tree imagery draws on mythological archetypes across cultures. Literary scholars view it as a contemporary World-Tree representation that connects the underworld with the earth and heaven (

Burt 2001;

Enomoto 1995). The three-level cosmic framework represents both vertical spiritual order and the active linkages between spatial realms.

Peter Burt notes that Takemitsu found inspiration in the rain tree as a “poetic metaphor of fertility and growth,” a way of evoking the “eternal recurrence” of natural cycles in musical form (

Burt 2001, p. 205). The rain tree functions as a dynamic spiritual entity mediating between planes of existence; this is its symbolic power.

The creative partnership between Takemitsu and Kenzaburō Ōe demonstrates a distinctive mode of artistic communication rooted in shared aesthetic philosophy rather than literal interpretation. Their collaboration operates through intuitive perception that allows artists to grasp essential meanings without analytical mediation. When Takemitsu encountered Ōe’s rain tree metaphor, he responded not through systematic literary analysis but through immediate recognition of its contemplative essence.

In an interview with musicologist Jimmie W. Finnie, Takemitsu acknowledged the difficulty of explaining the relationship between

Rain Tree and his own pieces: “It is hard to say, because I have not read it,” he noted; nevertheless, “no relationship has to be established with the entire story of Clever Rain Tree” to explain the significance of the metaphor for his works (

Finnie 1995, p. 67). The apparent paradox reveals a fundamental cognitive process in artistic creation. The Zen tradition’s direct pointing appears in Takemitsu’s natural comprehension of the rain tree symbol, allowing him to access essential truths without textual mediation. Artistic communication thus takes place beyond rational understanding through immediate spiritual perception of the image; complete textual reading is not required.

The transformation from Ōe’s literary symbol to Takemitsu’s musical metaphor constitutes a form of spiritual transduction: it converts visual and conceptual elements into auditory experiences while maintaining—and in some ways intensifying—the original contemplative power through the change in medium. Takemitsu’s music translates the rain tree’s cyclical collection and release of moisture into recurring thematic patterns that acoustically model natural cycles. Recurrence, spacing, and decay act as listening cues that help performers and audiences sustain steady attention. Through the temporal unfolding of sound, Takemitsu creates an acoustic environment that allows listeners to connect with natural rhythms through musical progression.

Takemitsu converts the rain tree’s spiritual qualities into specific musical language in his solo piano compositions

Rain Tree Sketch and

Rain Tree Sketch II. The repeated, relatively static harmonic structures, using modal pitch collections and unresolved dissonances, and produce audible impressions of raindrops falling on leaves. Irregular rhythmic structures together with extended silences simulate natural processes that are asymmetrical and nonlinear (

Koozin 2002). The opening marking “celestial light” calls for a pale, floating tone color. It guides touch, pedaling, and decay. Rather than demanding any particular spiritual state from the performer, it primarily shapes the intended sonority so the section sounds coherent; at the same time, it can implicitly cue a calm mental focus.

4. The Sacred Void of Ma

The spiritual aspects of Takemitsu’s Rain Tree Sketch require understanding the traditional Japanese aesthetic idea of ma as the primary key to its musical structure. Takemitsu transformed the spatial–temporal concept of ma found in East Asian philosophy into a musical–spiritual method that turns abstract sound patterns into vehicles for transcendent experience.

According to the Iwanami Dictionary of Ancient Terms’ definition:

“ma refers to the natural distance between two or more things existing in a continuity or the natural pause or interval between two or more phenomena occurring continuously.”

(Iwanai Dictionary of Ancient Terms. quoted in

Isozaki 1979)

However, such a dictionary entry offers only a basic explanation. In traditional Japanese culture,

ma is an active void filled with possibility. Modern architectural theorist Arata Isozaki explains that ma functions as “the place where life is experienced,” shaping the living environments of observers of this aesthetic (

Isozaki 1979, p. 69).

The essential nature of

ma becomes apparent through this explanation: it is a pregnant void filled with potential. Although the concept may initially seem foreign to Western thought, it resonates with several Western philosophical and mystical traditions. Apophatic theology, particularly in the works of Pseudo-Dionysius and Meister Eckhart, approaches the divine through negation, finding fullness in apparent emptiness (

Robert 2012). Takemitsu’s achievement lies in making this productive emptiness directly experiential through musical structure, allowing listeners from any cultural background to encounter the generative potential of silence without philosophical training. This cross-cultural resonance suggests that Takemitsu’s use of

ma operates on broadly human rather than narrowly culture-specific principles of consciousness. The musical implementation of

ma in

Rain Tree Sketches therefore offers a practical demonstration of contemplative principles that philosophy has long theorized but has rarely made directly experiential. Through precise compositional techniques, Takemitsu turns abstract concepts into lived acoustic experience.

Takemitsu understood ma with both depth and originality. In a 1988 interview, he remarked:

“Ma cannot be dominated by a person, or by a composer. Of course, ma can never be determined. Ma is the mother of sound and should be very vivid. Ma is living space, more than actual space.”

This statement reveals both his philosophical understanding of ma and how he transformed the concept into concrete compositional practices.

The various levels of ma become evident in the structure of Rain Tree Sketch. First, the composition relies on intervallic structures. Its deliberately constructed contemplative architecture emerges through Takemitsu’s strategic deployment of silences and pauses. These silences serve specific compositional functions that extend beyond mere cessation of sound.

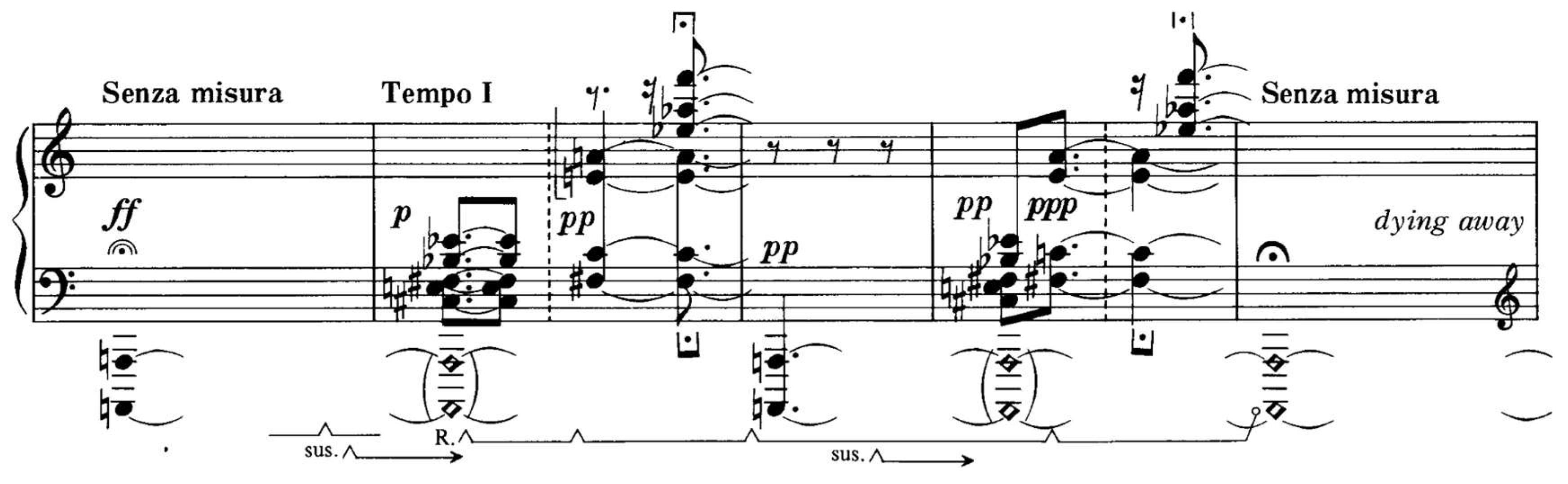

For instance, in

Figure 1 (

MM. 45–51), static soprano parts appear every two measures (mm. 45, 48, 51); together with the bass’s sustained repetition of A, they create a unique temporal experience. The passage looks still yet holds built-up psychological energy that prepares the start of the next section. This is what Takemitsu termed “living space.”

Second,

ma operates at the timbral level. Internal sound variation within traditional Japanese music receives utmost attention, and this concept finds contemporary expression in

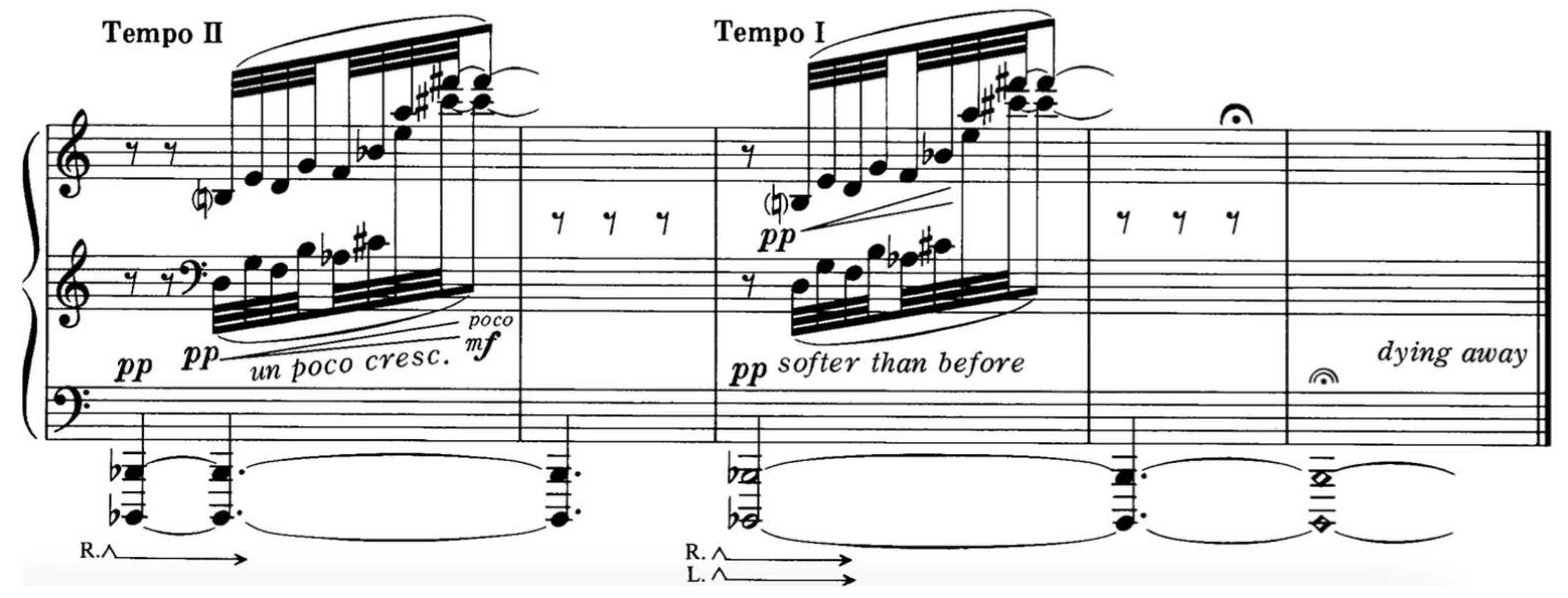

Rain Tree Sketch I. The phrase consisting of two identical sections in

Figure 2 (

MM. 80–84) demonstrates Takemitsu’s deliberate approach to timbral development. The composer instructs performers to play the second occurrence “softer than before,” together with detailed pedal directions. To achieve proper muting during the second repetition, the performer must use both the right pedal and the soft pedal. The technical support enables each sound to become a spiritual moment that listeners can experience deeply.

In Rain Tree Sketch, ma shapes attention and the sense of time by translating Ōe’s depiction of temporal suspension in the rain tree’s moisture cycles into musical space. The same cues that work aesthetically may also support a quieter, more focused mode of listening. This is an invitation, not a guarantee, for every listener. The method produces an exceptional temporal encounter that helps people slip free of everyday time awareness and reach heightened states of attention.

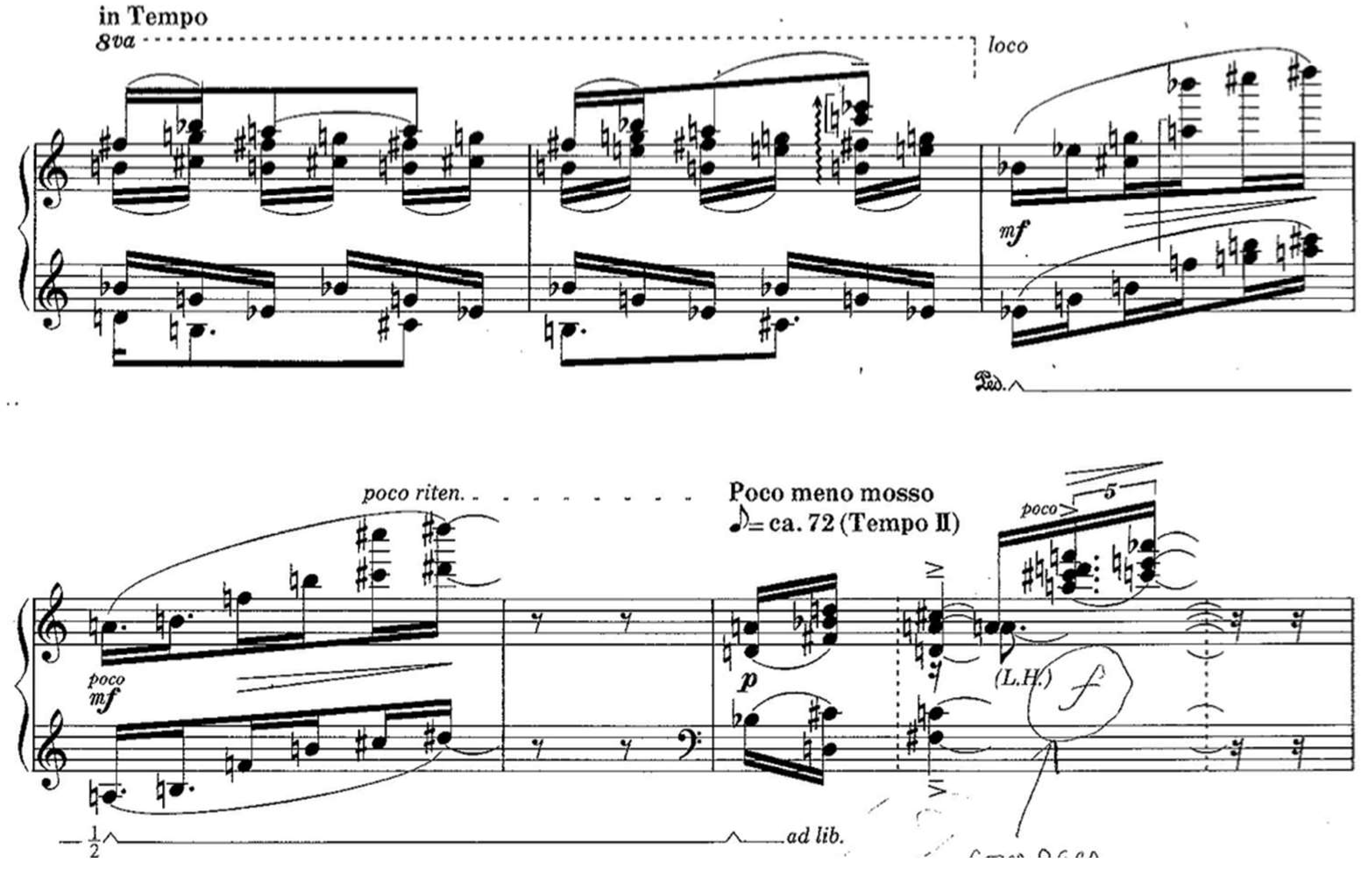

This spiritual function is realized through several mechanisms. The combination of sonic sequences and silent intervals functions as a breathing rhythm, an organic wave that aligns with human mental patterns. The reappearance of textures in

Rain Tree Sketch II from

MM. 4–8 at

MM. 6–7 (

Figure 3) creates a dual experience of familiarity and novelty through registral expansion, leading listeners toward advanced listening and preparing sectional transformation.

Ma invites participatory listening. In many concert settings, listeners are observers of a fixed score. Here, ma invites active listening because it asks the listener to supply attention. Each rest opens a small space for reflection.

Through his use of

ma, Takemitsu develops a musical language with broad spiritual reach. The piece includes no liturgical text, ritual frame, or confessional symbols. It relies on timing, color, and silence, which travel across settings. The design represents Takemitsu’s spiritual vision by representing Japanese tradition while reaching beyond cultural boundaries. The achievement of universality occurs through the retention of cultural characteristics because it engages fundamentals of human consciousness. The silences generated by

ma reveal the shared insight of many contemplative traditions: deeper awareness can arise in the gaps between thoughts. Whether Buddhist “śūnyatā” (emptiness), Christian mysticism’s “sacred darkness,” or Islamic Sufism’s fanā (self-annihilation), these traditions testify to similar experiences (

Taufiqurrohman 2024). Through his musical use of

ma, Takemitsu invites contemporary audiences toward this shared contemplative dimension. Whether a listener attains it depends on context and practice.

5. The Metaphor of Water: Musical Transformation from Natural Phenomenon to Spiritual Symbol

Water constitutes an essential thematic element throughout Toru Takemitsu’s aesthetics, directly inspired by Ōe’s rain tree metaphor in which collected rainwater becomes the medium of memory and spiritual continuity. Throughout his career, from Water Music through the late “Rain” pieces, Takemitsu used water as a spiritual symbol that transcends mere depiction to convey philosophical meanings. Burt’s discussion of the “sea of tonality” highlights Takemitsu’s cultural grounding in Japanese water symbolism, which he used to develop his distinctive approach to musical fluidity (

Burt 2001).

In Japanese spiritual tradition, water bears multiple layers of meaning. It is sacred in Shinto because it purifies and regenerates. Water basins (temizuya) at shrine entrances and waterfall ascetic practices (takigyō) show water as a means of purification extending beyond the physical to the spiritual. Water’s flowing nature represents life’s continual transformation.

According to Kōji Matsunobu, the musical practice of otodamaho teaches the purification of body and mind through natural sounds—including waterfalls, streams, and rain—and it deeply shaped Takemitsu’s approach (

Matsunobu 2007). Within Japanese aesthetics, water functions as an emotional symbol: tranquil surfaces signify peace, while moving surfaces suggest shifting emotion. With the arrival of Buddhism in Japan, water’s formlessness came to exemplify emptiness.

Takemitsu built his musical representation of water through sustained philosophical study. He candidly acknowledged that “music has always had a connection to water, even from the early days” (

Takemitsu 2000, pp. 454–56). Water and sound share physical traits: both are wave phenomena that display fluidity and permeability. Takemitsu drew technical inspiration from this similarity to develop musical techniques that replicate water’s natural flow. He was also fascinated by water’s transformations of state. Water exists as solid (ice), liquid (water), or gas (vapor), yet its molecular structure remains unchanged. The essential nature of music parallels this: music transforms through time while its inner structure persists. His finest works demonstrate that water-like surface changes can maintain deep unity beneath.

Among water’s features, its capacity for “memory” particularly struck Takemitsu. According to Noriko Ohtake, water functions both as physical phenomenon and as a spiritual medium that transports memories and dreams. This poetic insight led him to explore sonic memory through musical development, allowing earlier sounds to leave traces that persist in later stages and create continuous temporal relationships (

Ohtake 1993).

The water symbolism in

Rain Tree Sketch exists through different musical approaches which demonstrate subtle implementation. Through his work on sound design Takemitsu developed a liquid sonority. The sustain pedal combined with una corda techniques through continuous use enables different pitch sounds to combine in the piano resonance chamber thus achieving water-like sonic effects. At

M. 53 (

Figure 4) the entire sound organization shows no full serial pattern while the combined hand-generated sounds emerge from physical mixing rather than rapid scales or arpeggios. Every note enters this sound pool to produce waves before becoming part of the whole.

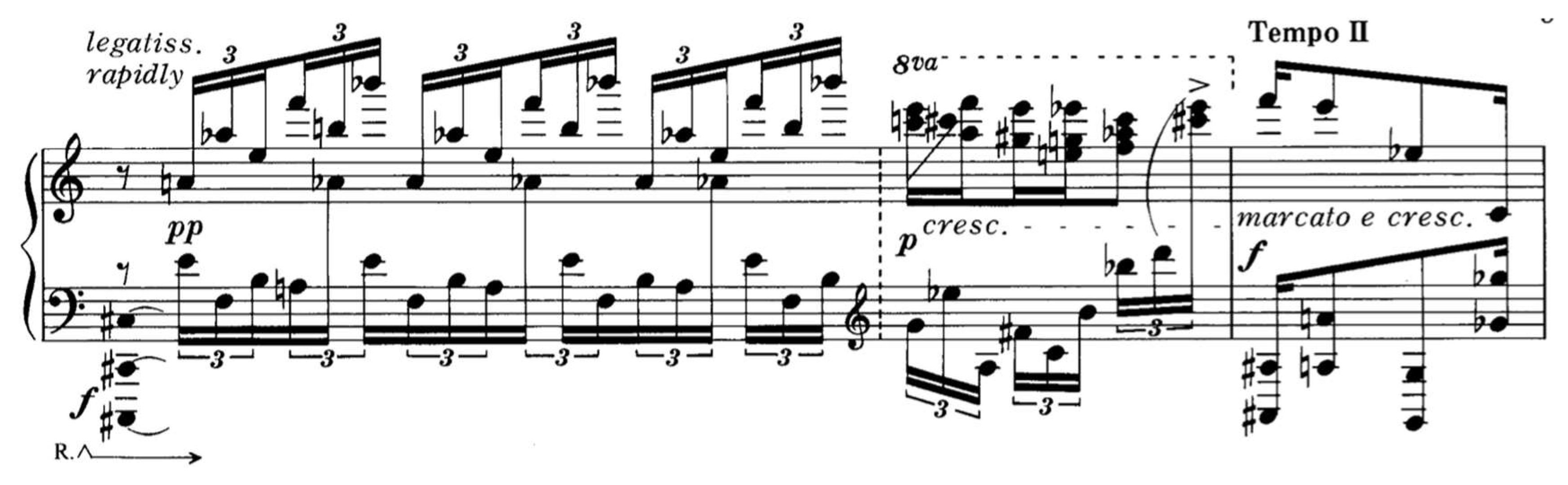

Rhythmically, Takemitsu created dropping patterns. The rhythmic structure takes its direct origin from Japanese traditional music which emulates natural sounds. Notes drop like water droplets which maintain balanced patterns between expected patterns and unexpected occurrences. Takemitsu gives explicit instructions at

MM. 42–44 (

Figure 5) to “leggerissimo rapidly” while instructing players to keep sustain pedal pressed until the phrase ends thus producing a controlled yet natural sound.

Formally, the work employs a ripple-like design. Through pitch-class set analysis, Koozin shows how Takemitsu used octatonic collections and referential set complexes to produce motifs that ripple through time like stones cast into water (

Koozin 2002). The sound waves transform subtly as they travel before fading into silence. Overall,

Rain Tree Sketches I and II consist of fragmented sections that alternate between Tempo I and Tempo II while maintaining organic connection through

ma, dropping rhythms, and liquid sonority.

Water’s temporal nature helped Takemitsu develop an original approach to musical time perception. According to Takemitsu, traditional Japanese music presents a perception of time that differs from Western norms: it is complex and multidimensional rather than linearly goal-directed (

Takemitsu 1987). The returns in

Rain Tree Sketch function as transformed repetitions that show water’s ability to recollect new experiences with each cycle. The result is a spiral-shaped temporal experience. Philosopher Henk Oosterling connects the Japanese concept of

ma to contemporary Western thought by demonstrating parallels with post-structuralist ideas of spacing or interval (

Oosterling 2000). In this analysis,

ma is not static emptiness but an active pause that generates meaning through what it holds apart. When Takemitsu places a silence between two phrases, it creates a charged space between sounds.

Performance of Rain Tree Sketch demands water-like thinking as the primary interpretive approach. Performers require specific technical training to achieve liquid sonority. The pedal functions beyond sustaining sound to blend attacks into continuous flow. Touch must adapt to the water state the musician aims to express.

At a spiritual level, performers cultivate a state of consciousness that resembles water’s qualities: internally stable yet flexible in response to each sonic situation. As Christopher I. Lehrich argues, performance is a living process that goes beyond score reproduction; each performance flows like water along the same riverbed yet produces distinct variations (

Lehrich 2014). Takemitsu turns the water image into method: droplet-like figures and sustained-pedal accumulations let multiple pitches overlap and blend, creating the acoustic equivalent of ripples on a surface. These techniques restructure temporal perception to mirror properties of flow, accumulation, and dispersion.

6. Digital Sacred Art: Technology as Spiritual Medium

Through the imagery of water and the temporality of ma, Toru Takemitsu elevates natural phenomena into spiritual symbols in music. However, this aesthetic often presents comprehension barriers in contemporary listening contexts. Not all listeners can directly grasp abstract sonic imagery and temporal blank space. Therefore this section proposes a visualization concept based on Synesthesia-2 to explore how this aesthetic might be presented in contemporary settings. The software can precisely map acoustic parameters to abstract geometric forms. It avoids narrative or excessive symbolic interference, aligning better with the aesthetic of emptiness in ma. Visual presentation can provide a pathway of understanding for listeners who struggle to perceive abstract sonic imagery directly. In our design, technology is used as a medium to assist music, which demonstrate how visualization can help audiences more intuitively experience the water symbolism and ma spacing in Rain Tree Sketch without disrupting its contemplative nature.

Educational research further indicates that visualization aids musical understanding. MIDI visualization helps identify subtle patterns difficult to detect through hearing alone (

Heyen and Sedlmair 2020). Real-time keyboard visualization enhances learners’ grasp of complex parameters (

Bauer 2020). While these findings originate from educational contexts, their conclusions apply equally to

Rain Tree Sketch. The water droplet imagery and temporal organization of ma in the work are precisely the type of structures that require additional visual cues yet must avoid over-interpretation, which means only describe what the music actually contains.

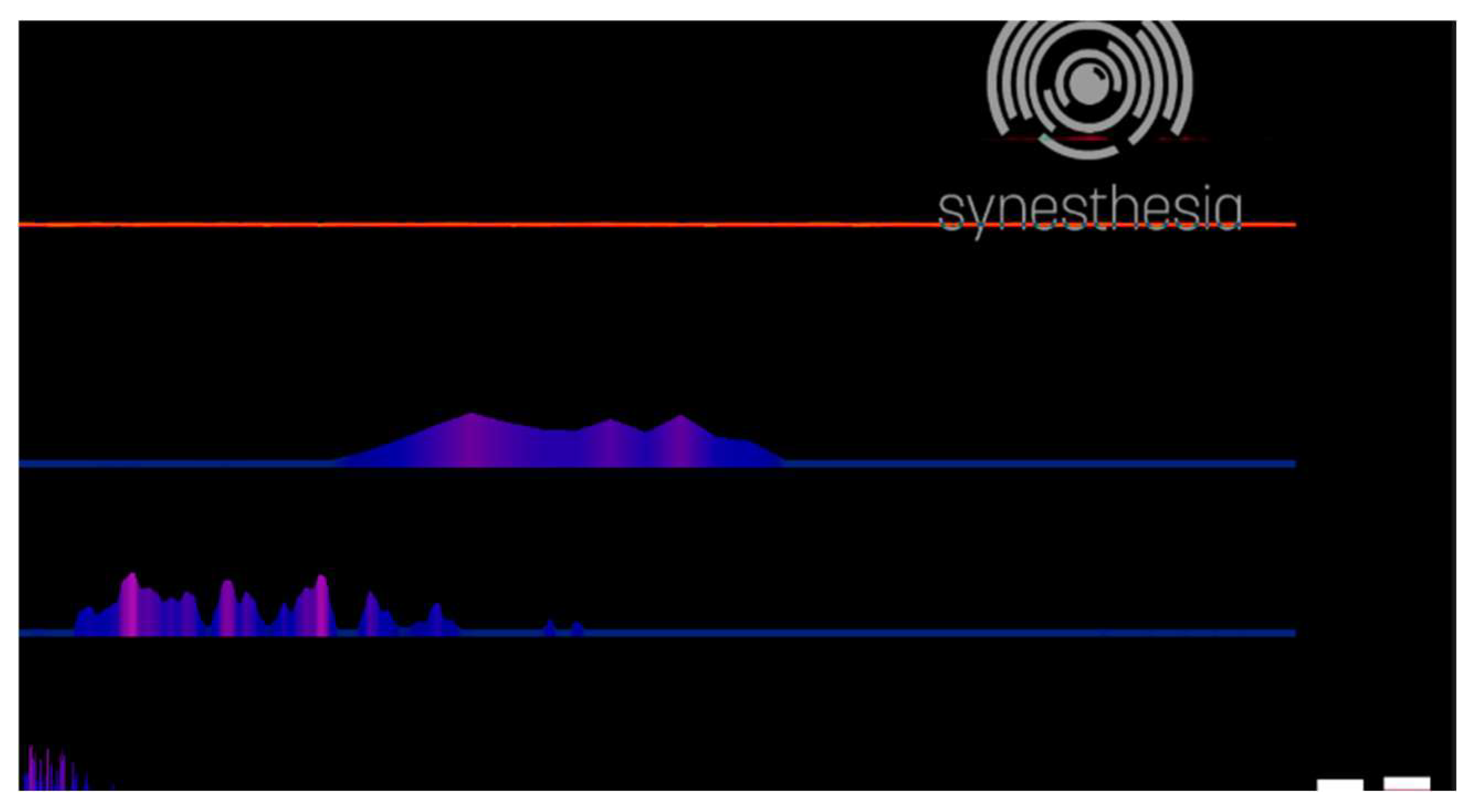

Against this background, we designed a visualization concept for Rain Tree Sketch based on Synesthesia-2. It directly converts acoustic parameters like pitch, loudness, timbre, and rhythm into simple geometric movements. Synesthesia-2 eliminates the need for complex programming, freeing researchers to focus on debugging technical issues.

This allows them to focus on calibrating the visuals and ensuring they align with the musical soundscapes, such as water and ma. Compared to TouchDesigner, which requires complex programming, it is more accessible. Unlike Magic Music Visuals, which favors figurative patterns, its abstract output does not steal attention or introduce additional narratives and symbols. More crucially, its decay control allows visual elements to disappear at the same rate as sound, preventing visual afterimages from filling the negative space of ma. Therefore, Synesthesia-2 naturally aligns technically with water’s fluidity and ma’s gaps, suitable for presentation without disturbing the musical subject.

In the specific design, we transform acoustic characteristics of different sections into corresponding visual logic. The opening (measures 1–6) employs a vertical particle waterfall design (

Figure 6). High-frequency notes are mapped as cool-colored light points slowly falling from the screen’s top. As frequency decreases, light points transition to dark green or black, eventually disappearing as afterimages. This design simulates raindrops seeping into soil. We strictly control afterimage duration to completely synchronize with the piano sound’s natural decay. This ensures

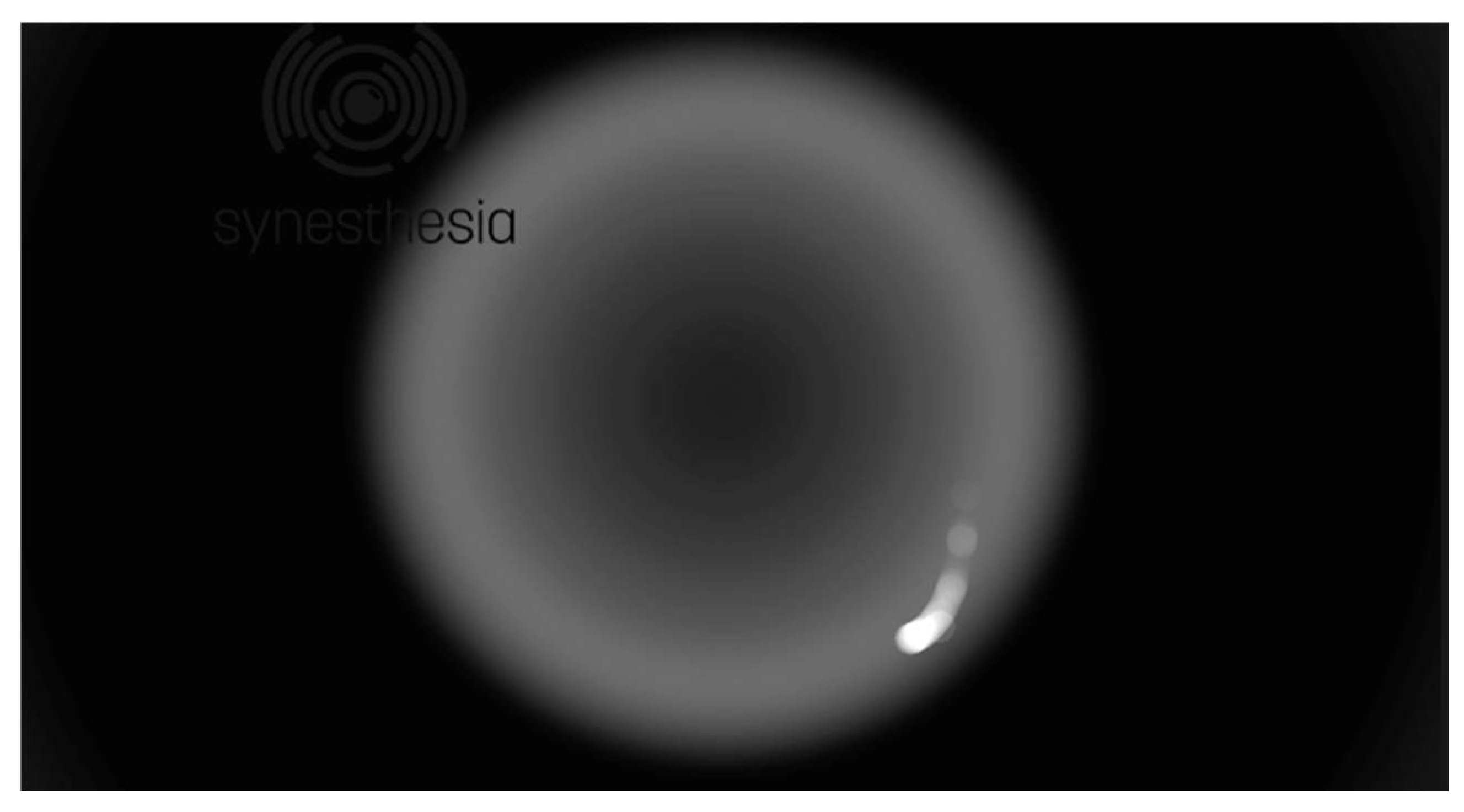

ma’s silence is not filled by visual afterimages. The middle section (measures 45–51) employs breathing halo diffusion (

Figure 7). The treble appears every two measures in this passage, combined with the sustained bass A, creating a unique floating sensation. We transform this musical structure into slowly diffusing concentric halos. When the treble appears, a pale blue light point generates at screen center, then expands outward at an extremely slow speed. The halo’s transparency decreases as the diffusion radius increases, completely disappearing before the next treble note. The lbass A appears as a deep blue horizontal line at the screen bottom, its brightness subtly fluctuating with volume. This design reinforces Takemitsu’s concept of

ma. The visual elements’ diffusion speed is precisely calculated to ensure the screen returns to stillness exactly when the music pauses. The repetition section (measures 80–84) employs mirrored projection with gradient transparency (

Figure 8). This passage contains two identical musical materials, but the composer requires the second performance to be softer. We reflect this timbral difference through changes in visual transparency. During the first performance, visual elements appear at normal brightness, forming clear ripple patterns. When entering the second repetition, the same visual patterns reappear but with transparency reduced to 40% of the original. The ripple diffusion speed also slows accordingly. By reducing visual intensity, we maintain ma’s negative space in repetition, avoiding visual interference with auditory meditation.

At the overall level, we establish a simple mapping between register and color. Low register notes appear as deep blue or dark green forms, evoking earth and deep sea imagery. High register notes appear as silver-white or pale gold light points, similar to starlight or morning dew. Middle register notes appear as cyan and sky blue. This color scheme maintains register recognizability while avoiding additional symbolic meaning. Additionally, we reinforce water imagery through fluid dynamics simulation. Each note produces concentric ripples that interfere with each other. Ripple size, diffusion speed, and duration depend on note characteristics. Greater volume produces more prominent ripples. Pedal layering creates more complex textures, echoing Takemitsu’s pursuit of liquid sound. During rests, diffusion is strictly limited, allowing visuals to naturally dissipate in silence, preserving ma’s emptiness. Audiences thus experience both the water surface as a note-mapping system and the dynamic presentation of rain washing ancient trees (

Figure 9).

Accordingly, we summarize three design principles for visualization. First, visual decay must synchronize with acoustic decay. Second, ripple propagation speed gradually decreases until completely stopping when sound ceases. Third, projection brightness remains at appropriate levels, allowing audiences to equally clearly distinguish the disappearance of both sound and light.

Finally, we must emphasize technology’s transparency. Visualization’s responsibility is helping listeners notice music’s inherent structure and imagery, not creating additional interpretations or effects. Visual presentation provides a path to understanding for listeners who have difficulty directly perceiving abstract sound images. Its purpose is to assist rather than replace the spiritual and structural experience of listening to music.

7. Discussion and Conclusions

This study examines the spiritual expression and visual presentation of Takemitsu’s Rain Tree Sketch, proposing an integrated perspective combining literary symbolism, Japanese aesthetics, and digital technology. First, it clarifies the unique transformation of literary symbols into musical language, specifically how Takemitsu converts Kenzaburō ōe’s rain tree imagery into sonic experience. Second, it systematically analyzes the concrete application of ma in the work, demonstrating how this Japanese aesthetic concept creates contemplative space through musical techniques. Third, it proposes visualization design principles based on Synesthesia-2 software, exploring the possibilities and boundaries of digital visualization in presenting spiritual content.

Regarding the transformation between literature and music, this study identifies a more direct path of artistic communication. Previous research has interpreted Takemitsu’s water imagery through cultural context and biographical events (

Burt 2001). However, this study finds that Takemitsu’s understanding of the rain tree metaphor derives from intuitive perception rather than rational textual interpretation. The dynamic imagery of the rain tree in the literature is translated into the piano’s collection and release of sound. Thus, symbolic meaning continues through acoustic processes rather than additional narrative. The work’s original meditative quality is thereby preserved.

Additionally, while existing research focuses primarily on compositional techniques or performance traditions, with Timothy Koozin emphasizing the octatonic system’s role in harmonic organization (

Koozin 2002) and Rui Hara exploring performance traditions and interpretive methods (

Hara 2020). Our study takes a different path. It focuses on how digital media can assist in conveying Takemitsu’s aesthetic thought. In contrast, this study concerns neither the pitch system itself nor performance operations alone. Instead, it explores how the abstract structure of ma can be perceived through digital visualization. To this end, we propose design principles based on Synesthesia-2: visual decay must synchronize with acoustic decay, the screen must return to stillness during rests, and brightness must remain moderate without exceeding boundaries. This methodology makes visualization a transparent aid. It allows listeners to more intuitively perceive water imagery and temporal negative space without weakening music’s original contemplative quality.

However, visual assistance may also produce negative effects. Some listeners might develop dependence on visuals. Once accustomed to visual music, their patience and immersion in pure listening environments might decrease. The boundary between assistance and interference thus becomes subtle. Excessive visual stimulation easily fills the emptiness of ma. What was originally a meditative experience might become entertainment performance. Technology overshadowing the main subject would destroy music’s essence. Furthermore, cultural differences deserve attention. While the design principles proposed in this study draw on Japanese aesthetics, particularly the emphasis on intentional white space in ma and the continuity symbolized by water, their core lies in cross-cultural multimodal symbolism. This parallels the universal conventions of classical musical notation, highlighted earlier in this article. Classical notation relies on shared codes that transcend cultural boundaries, and our Svnesthesia-2 visualization extends this logic, serving as a graphical form of musical notation. This visualization transforms acoustic parameters into abstract visual signals that draw on shared sensory norms rather than specific cultural references, ensuring its core utility is not limited to the Japanese context. However, audience familiarity with Japanese aesthetic concepts may influence interpretation. Listeners unfamiliar with the concept of ma as active white space may interpret the corresponding visual representation as simply empty space. Therefore, further research on how Western or non-Japanese audiences perceive this visualization is valuable.

Overall, this study tracked the spiritual concept of ma through its expression in various media. The article began with the literary symbolism of the rain tree in Kenzaburō Ōe’s story. It then analyzed how Tōru Takemitsu translated this image and its underlying spiritual principles into the musical language of Rain Tree Sketch. Finally, it explored how digital visualization can represent the music’s structure, offering a contemporary method for perceiving its contemplative qualities.