The Declining Sense of Belonging to the Church and Vocation Among Young Catholic Women in Lebanon: A Qualitative Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Sense of Belonging to the Church

2.2. Vocational Commitment

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Design

3.2. Participants and Data Collection

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Theme 1: Sense of Belonging to the Church

4.1.1. Family, Upbringing, and Socialization

“Growing up in a Christian family increased my belonging”;(Participant 12)

“Growing up in fraternities [and parishes] increased my belonging”(Participant 12)

4.1.2. Faith, Values, and Belonging

4.1.3. Community, Engagement, and Active Participation

4.1.4. Challenges, Critiques, and Demotivators

4.1.5. Women Leadership and Belonging

4.2. Theme 2: Perception of Vocation

4.2.1. Divine Calling and Relationship with God

“Vocation is a call to be in the image of God, nothing more”;(Participant 1)

“I live my vocation by thinking what Jesus or Mary would do in my place in a particular situation”(Participant 5)

4.2.2. Universal Nature of Vocation

“There is also a particular vocation that the person has to find out”;(Participant 16)

“[There is a] vocation for everyone, because God loves everyone”;(Participant 8)

“We all have a vocation, not only consecrated people”(Participant 17)

4.2.3. Personal Identity and Self-Development

4.2.4. Components of Vocation

4.2.5. Family and Background Influences

4.3. Theme 3: Factors Influencing the Choice of a Consecrated Life

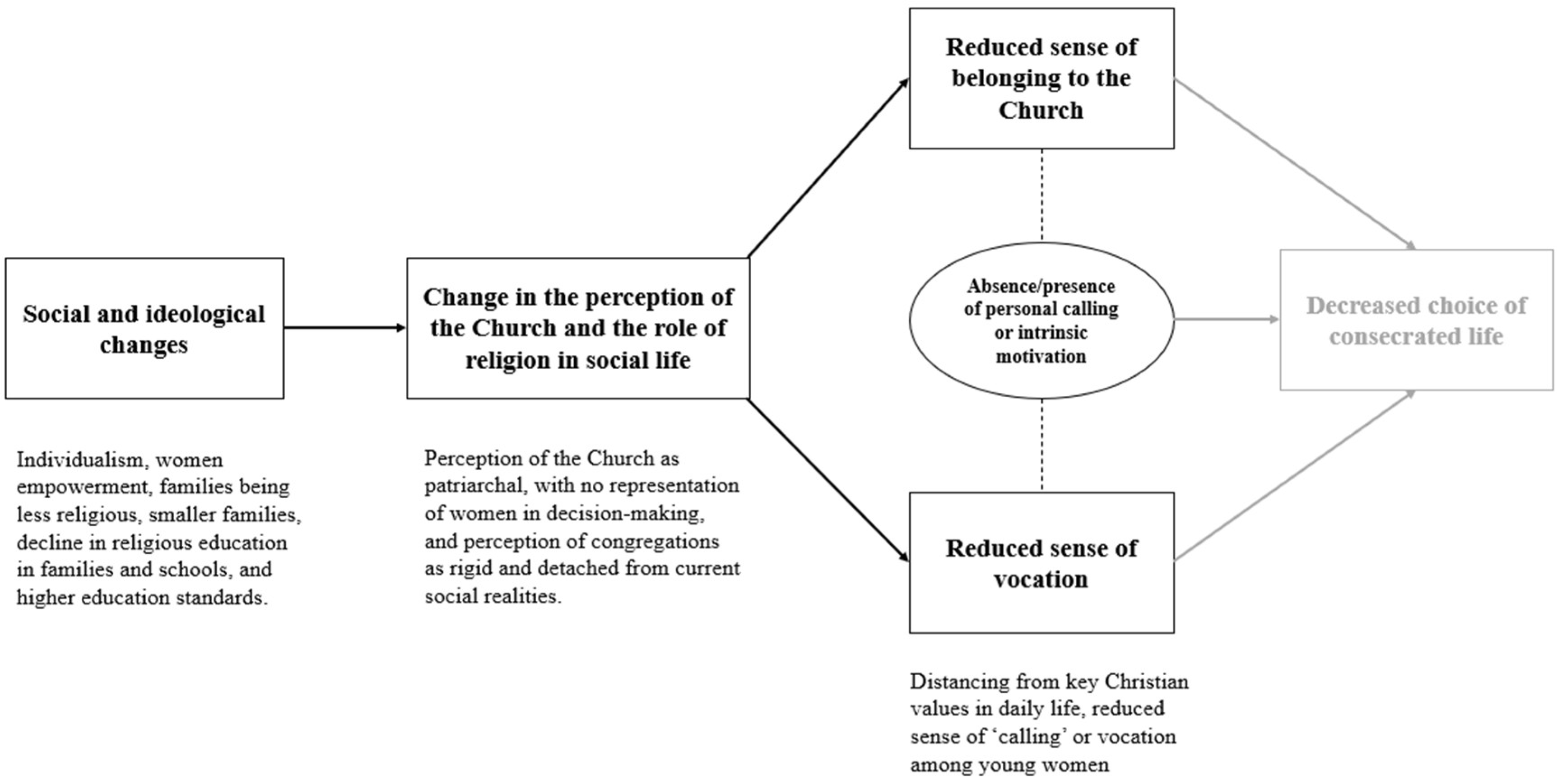

4.4. Theme 4: Decreasing Vocational Commitment and Belonging to the Church

4.4.1. Changing Social, Cultural, and Familial Contexts

4.4.2. Educational and Socio-Economic Factors

4.4.3. Desire for Personal Freedom, Autonomy, and Alternative Lifestyles

4.4.4. Perceptions of Consecrated Life and Institutional Issues

“The pressure and restrictions in consecrated life weigh heavily on young women, which does not attract them”(Participant 10)

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abboud-Mzawak, Mirna. 2012. Les jeunes catholiques du Liban: Enjeux et perspectives. Assemblée Générale des Patriarches et des Evêques Catholiques au Liban. Bkerke: Maronite Patriarchate. [Google Scholar]

- Abboud-Mzawak, Mirna. 2018. L’engagement chrétien entre conception et vécu. Jounieh: PUSEK. [Google Scholar]

- Abboud-Mzawak, Mirna, and Chantale Ibrahim. 2025. The Maronite Women: A Socio-Ecclesial Perspective on their Contribution to Religious and Social Life. Journal of Literature and Translation 23: 207–30. [Google Scholar]

- Abboud-Mzawak, Mirna, and Rudy Younes. 2025. Women Consecrated Life in Lebanon: Identity and Perspectives. In Femmes Missionnaires en Terres D’islam: Enracinements, Limites, Mutations. Lyon: Centre de Recherche et d’Echanges sur la Diffusion et l’Inculturation du Christianisme. [Google Scholar]

- Abboud-Mzawak, Mirna, Rudy S. Younes, and Clara Moukarzel. 2025. The Socio-Ecclesial Identity Components of the Maronite Church: A Comprehensive Study. Church, Communication and Culture 9: 83–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, Kelly-Ann, Margaret L. Kern, Christopher S. Rozek, Dennis M. McInerney, and George M. Slavich. 2021. Belonging: A review of conceptual issues, an integrative framework, and directions for future research. Australian Journal of Psychology 73: 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arab Barometer. 2023. MENA Youth Lead Return To Religion. Available online: https://www.arabbarometer.org/2023/03/mena-youth-lead-return-to-religion/ (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Bardin, Laurence. 1977. L’Analyse du Contenu. Paris: PUF. [Google Scholar]

- Barón, María García-Nieto. 2023. La incorporación de las mujeres a la organización de la Iglesia: Un proceso abierto. Church, Communication and Culture 8: 184–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, Roy F., and Mark R. Leary. 1995. The Need to Belong: Desire for Interpersonal Attachments as a Fundamental Human Motivation. Psychological Bulletin 117: 497–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertrand, Catherine, and Laurent Bourdeau. 2010. Research interviews by Skype: A new data collection method. In Proceedings of the 9th European Conference on Research Methods, Madrid, Spain, 24–25 June 2010. Edited by Jorge Esteves. Madrid: IE Business School, pp. 70–79. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/256117370_Bertrand_C_Bourdeau_L_2010_Research_interviews_by_Skype_A_new_data_collection_method_In_J_Esteves_Ed_Proceedings_from_the_9th_European_Conference_on_Research_Methods_pp_70-79_Spain_IE_Business_School (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Davis, Lewis S., and Claudia Williamson. 2019. Does Individualism Promote Gender Equality? World Development 123: 104627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, Abby. 2011. Believing in Belonging: Belief and Social Identity in the Modern World. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dib, Pierre. 1971. History of the Maronite Church. Bkerke: Maronite Apostolic Exarchate. [Google Scholar]

- Dik, Bryan J., Ryan D. Duffy, Blake A. Allan, Maeve B. O’Donnell, Yerin Shim, and Michael F. Steger. 2014. Purpose and Meaning in Career Development Applications. The Counseling Psychologist 43: 558–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorr, Donal. 2019. Women in the Church—Or out of It. The Furrow 70: 387–394. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/45210261 (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Durand, Jean-Paul. 2004. Nation et religions: Le Liban Ouverture du 5e colloque, Beyrouth, le 8 novembre 2003. L’Année Canonique 46: 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erikson, Erik H. 1994. Identity Youth and Crisis. Washington, DC: National Geographic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Errázuriz, Carlos. 2020. Il Diritto e la Giustizia Nella Chiesa: Per Una Teoria Fondamentale del Diritto Canonico. Lombardia: Lefebvre Giuffre. [Google Scholar]

- Ertl, Bernhard, Florian G. Hartmann, and Jörg-Henrik Heine. 2020. Analyzing Large-Scale Studies: Benefits and Challenges. Frontiers in Psychology 11: 577410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fédou, Michel. 2018. The Christian Vision of the Universal. Études 3: 71–74. Available online: https://shs.cairn.info/journal-etudes-2018-3-page-71?lang=en (accessed on 15 July 2025). [CrossRef]

- Gregor, Margo A., and Karen M. O’Brien. 2015. Understanding Career Aspirations Among Young Women. Journal of Career Assessment 24: 559–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, Yvonne, and Rahel Fischbach. 2015. Interfaith Dialogue in Lebanon: Between a Power Balancing Act and Theological Encounters. Islam and Christian-Muslim Relations 26: 423–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagerty, Bonnie M.K., Judith Lynch-Sauer, Kathleen L. Patusky, Maria Bouwsema, and Peggy Collier. 1992. Sense of Belonging: A Vital Mental Health Concept. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing 6: 172–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holy See. 1992. Catechism of the Catholic Church. Available online: https://www.vatican.va/archive/ENG0015/_INDEX.HTM (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Hughes, Gerard J. 2013. On Modernising the Church. The Furrow 64: 142–52. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/24635587 (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- John Paul II. 1988. Christifideles Laici: On the Vocation and the Mission of the Lay Faithful in the Church and in the World. Post-Synodal Apostolic Exhortation. Available online: https://www.vatican.va/content/john-paul-ii/en/apost_exhortations/documents/hf_jp-ii_exh_30121988_christifideles-laici.html (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Join-Lambert, Arnaud. 2022. Les ministères par des femmes dans l’Église catholique Un problème de chœur? Revue Lumen Vitae LXXVII: 285–95. Available online: https://shs.cairn.info/revue-lumen-vitae-2022-3-page-285?lang=fr (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Kasselstrand, Isabella. 2015. Nonbelievers in the Church: A Study of Cultural Religion in Sweden. Sociology of Religion 76: 275–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoury, Nay. 2018. La vie Monastique des Femmes Maronites au Liban: Réalité et Perspectives Pratiques. Jounieh: Holy Spirit University of Kaslik. [Google Scholar]

- Lefeuvre, G. 1999. Vocation. In Catholicisme, Hier, Aujourd’hui et Demain. Paris: Letouzey & Ané. [Google Scholar]

- Leszczyńska, Katarzyna. 2019. Between Womanhood as Ideal and Womanhood as a Social Practice: Women’s Experiences in the Church Organisation in Poland. Journal of Contemporary Religion 34: 311–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobkowicz, Nicholas. 1991. Christianity and Culture. The Review of Politics 53: 373–89. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1407759 (accessed on 15 July 2025). [CrossRef]

- Lummis, Adair T. 2004. A Research Note: Real Men and Church Participation. Review of Religious Research 45: 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, Terese Jean, Belle Liang, Jonathan Sepulveda, Allison E. White, Kira Patel, Angela M. DeSilva Mousseau, and Renée Spencer. 2021. Parenting and Youth Purpose: Fostering Other-Oriented Aims. Youth 1: 2–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandes, Sławomir, and Maria Rogaczewska. 2013. ‘I Don’t Reject the Catholic Church—The Catholic Church Rejects Me’: How Twenty- and Thirty-somethings in Poland Re-evaluate Their Religion. Journal of Contemporary Religion 28: 259–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maronite Patriarchate. 2023. The Vocation and Mission of Women in the Economy of God, the Life of the Church, and Society: A Foundational Document for the Synodal Journey in the Antiochene Syriac Maronite Church. Bkerke: Maronite Patriarchate. [Google Scholar]

- Olcoń, Katarzyna, Yeonwoo Kim, and Lauren E. Gulbas. 2017. Sense of Belonging and Youth Suicidal Behaviors: What Do Communities and Schools Have to Do With It? Social Work in Public Health 32: 432–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Opdenakker, Raymond. 2006. Advantages and Disadvantages of Four Interview Techniques in Qualitative Research. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung 7: 11. [Google Scholar]

- Patsch, Ferenc. 2022. Secularization, models of the church, and spirituality. Studia Nauk Teologicznych PAN 17: 151–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pew Research Center. 2016. The Gender Gap in Religion Around the World. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2016/03/22/the-gender-gap-in-religion-around-the-world/ (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Pew Research Center. 2018. Young Adults Around the World Are Less Religious by Several Measures. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2018/06/13/young-adults-around-the-world-are-less-religious-by-several-measures/ (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Pope Francis. 2022. Praedicate Evangelium. Vatican City: The Holy See. Available online: https://www.vatican.va/content/francesco/en/apost_constitutions/documents/20220319-costituzione-ap-praedicate-evangelium.html (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Pope Paul VI. 1964. Lumen Gentium. Vatican City: Holy See. Available online: https://www.vatican.va/archive/hist_councils/ii_vatican_council/documents/vat-ii_const_19641121_lumen-gentium_en.html (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Pospíšil, Jiří, and Pavla Macháčková. 2021. The Value of Belongingness in Relation to Religious Belief, Institutionalized Religion, Moral Judgement and Solidarity. Religions 12: 1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Přibyl, Stanislav. 2021. Human person in the Code of Canon Law of John Paul II. Philosophy and Canon Law 7: 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raman, Shibu. 2014. Sense of Belonging. In Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research. Edited by Alex C. Michalos. Dordrecht: Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruether, Rosemary R. 2014. Sexism and Misogyny in the Christian Tradition: Liberating Alternatives. Buddhist-Christian Studies 34: 83–94. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/24801355 (accessed on 15 July 2025). [CrossRef]

- Saunders, Benjamin, Jenny Kitzinger, and Celia Kitzinger. 2015. Anonymising interview data: Challenges and compromise in practice. Qualitative Research 15: 616–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiotz, Fredrik A. 1944. A Christian Concept of Vocation. Christian Education 28: 39–47. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/41175057 (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Smith, Susan. 1995. Made in God’s Image: A Report on Sexism Within the Catholic Church in New Zealand. Feminist Theology 4: 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stratton, Samuel J. 2021. Population Research: Convenience Sampling Strategies. Prehospital and Disaster Medicine 36: 373–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaughan, Kenneth. 2018. Who Benefits From Consociationalism? Religious Disparities in Lebanon’s Political System. Religions 9: 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Bingbing. 2007. Secularism and secularization in the Arab world. Journal of Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies 1: 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Yih, Caroline. 2022. Theological Reflection on Silencing and Gender Disenfranchisement. Practical Theology 16: 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Themes | Questions |

|---|---|

| Theme 1: Vocation | How do you perceive the Christian vocation in general? In your opinion, what are its main components? |

| How would you describe your own vocation? How do you live this vocation in your daily life? | |

| Theme 2: Consecrated life | How would you describe the way of life in consecrated life? What are the enriching aspects of consecrated life, and what are its main challenges? |

| In your opinion, what are the main differences between consecrated life and secular life? | |

| Why do you think more young women are choosing secular life instead of consecrated life? | |

| Theme 3: Belonging to the Church | To what extent do you feel that you belong to the Catholic Church? What are the main challenges of belonging to the Church? |

| What drives or motivates you to take on your current role within the Catholic Church? And what demotivates you in your role within the Church? | |

| What aspects of the Catholic Church do you find most meaningful for your personal identity? Are there specific principles, values, practices, or rituals of the Catholic Church that hold particular significance for you? |

| Participant | Profile Description |

|---|---|

| 1 | Young consecrated woman in the Congregation of Our Lady of Perpetual Help. She is a missionary involved in social action. |

| 2 | Responsible for the novitiates and a missionary within the Antonine Congregation, with a primary focus on apostolate, especially for future consecrated individuals. |

| 3 | Responsible for the novitiates and a social worker with 22 years of consecrated life. She has participated in various missions, including social services to support families, apostolate in mixed communities in Beirut, and social work in a school. |

| 4 | Young consecrated missionary in the Congregation of the Daughters of Charity. |

| 5 | Young consecrated woman in the Congregation of Our Lady of the Rosary and serving in a school in Beirut. |

| 6 | Young consecrated woman in the Antonine Congregation, engaged in social and healthcare services. |

| 7 | Young consecrated woman, a member of the Lebanese Maronite Order. |

| 8 | Member of the Congregation of Saint Thérèse of Lisieux, serving as secretary and general counselor in her congregation. Her mission focuses on healthcare services and social action. |

| 9 | Young consecrated woman of Our Lady of Charity of the Good Shepherd. She is also a social worker involved in addressing social and family issues. |

| 10 | Consecrated woman of Our Lady of Charity of the Good Shepherd for 34 years. Her mission is focused on addressing social and family issues. |

| 11 | General Mother with over 30 years of experience in missions. |

| 12 | Young Christian woman not engaged in the Church and without a statutory affiliation. |

| 13 | Young Christian woman with a statutory role in her parish and diocese. |

| 14 | Young consecrated woman who joined a congregation less than a year ago. |

| 15 | Young Christian woman not engaged in the Church and without a statutory affiliation. |

| 16 | Young consecrated laywoman. |

| 17 | Young Christian woman with a statutory role in her parish and diocese. |

| 18 | Young Christian woman without a statutory role in her parish, who was engaged in the Church when she was younger. |

| 19 | Young Christian woman with a statutory role in her parish and diocese. |

| 20 | Young Christian woman with a statutory role in her parish and diocese. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Younes, R.S.; Mzawak, M.A.; Zalaket, N. The Declining Sense of Belonging to the Church and Vocation Among Young Catholic Women in Lebanon: A Qualitative Study. Religions 2025, 16, 1143. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16091143

Younes RS, Mzawak MA, Zalaket N. The Declining Sense of Belonging to the Church and Vocation Among Young Catholic Women in Lebanon: A Qualitative Study. Religions. 2025; 16(9):1143. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16091143

Chicago/Turabian StyleYounes, Rudy S., Mirna Abboud Mzawak, and Nadine Zalaket. 2025. "The Declining Sense of Belonging to the Church and Vocation Among Young Catholic Women in Lebanon: A Qualitative Study" Religions 16, no. 9: 1143. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16091143

APA StyleYounes, R. S., Mzawak, M. A., & Zalaket, N. (2025). The Declining Sense of Belonging to the Church and Vocation Among Young Catholic Women in Lebanon: A Qualitative Study. Religions, 16(9), 1143. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16091143