Abstract

Sacred choral music continues to hold a significant place in contemporary concert settings, with historical and newly composed works featuring in today’s choral programmes. Contemporary choral composers have continued to engage with the longstanding tradition of setting sacred texts to music, bringing fresh interpretations through their innovative compositional techniques and fusion of styles. Irish composer Rhona Clarke’s (b. 1958) expansive choral oeuvre includes a wealth of both sacred and secular compositions but reveals a notable propensity for the setting of sacred texts in Latin. Her synthesis of archaic and contemporary techniques within her work demonstrates both the solemn and visceral aspects of these texts, as well as a clear nod to tradition. This article focuses on Clarke’s choral work O Vis Aeternitatis (2020), a setting of a text by the medieval musician and saint Hildegard of Bingen (c. 1150). Through critical score analysis, we investigate the piece’s melodic, harmonic, and textural frameworks; the influence of Hildegard’s original chant; and the use of extended vocal techniques and contrasting vocal timbres as we articulate core characteristics of Clarke’s compositional style and underline her foregrounding of the more visceral aspects of Hildegard’s words. Clarke’s fusion of creative practices from past and present spotlights moments of dramatic escalation and spiritual importance, and exhibits the composer’s distinctive compositional voice as she reimagines Hildegard’s text for the twenty-first century.

1. Introduction: Rhona Clarke (b. 1958)

Rhona Clarke is one of Ireland’s foremost contemporary composers. Her compositional career spans four decades and encompasses choral, chamber, orchestral, and electronic music. Her engagement with choral music has remained a consistent factor throughout her life, from premieres of her early works at Cork International Choral Festival in the 1980s to State Choir Latvija’s 2022 choral portrait album Sempiternam. Clarke has noted how her interest in choral music ‘was always there’, and how the physicality of the human voice is irreplaceable in terms of sound (The Contemporary Music Centre 2022). She has stated that, when composing, she sets herself ‘the challenge to create what I’ve not heard or am not hearing yet […] I want whatever is coming off my scores to be now’ (The Contemporary Music Centre 2022). However, this desire for innovation is balanced with influences drawn from earlier musical eras, and she summarises her compositional style as ‘a mix of the traditional with some innovative aspects, as in innovative of our time, of the twentieth, twenty-first century. There’s always a nod to the tradition’ (R. Clarke 2025). In this article, we examine Rhona Clarke’s choral piece O Vis Aeternitatis (2020) as a means of articulating core characteristics of her compositional style and approach, primarily in the areas of melodic and harmonic language, textural organisation, allusion, and extended vocal techniques. In particular, we investigate how this striking work merges elements from prior compositional eras with innovative contemporary techniques to create a distinctive reimagination of an ancient sacred text.

2. O Vis Aeternitatis

An overview of Rhona Clarke’s choral oeuvre reveals a propensity for continuing the long-established choral tradition of setting Latin texts. The composer has noted her attraction to the sounds of this ancient language, stating that it ‘allies superbly with the singing voice’ (R. Clarke 2022). Many of her Latin settings, such as Salve Regina (2007), Requiem (2020), and O Vis Aeternitatis (2020), are influenced by liturgical chant, paraphrasing existing melodies or featuring new phrases reminiscent of chant. Clarke attributes her Latin-based works and allusion to plainchant to ‘learning plainchant and studying Latin at school’ (R. Clarke 2022). It could also be posited that her settings of ancient texts have been informed by her experiences of performing Renaissance music with the Dublin-based choirs The Lindsay Singers and Gaudete Chamber Choir (Wright 1996), her own score study, and, as Barbara Lamont observes, her exploration of plainchant and sixteenth-century polyphony with Dr Hans Waldemar Rosen and Fr Sean Lavery during her undergraduate studies at University College Dublin (Lamont 2016, p. 8). These encounters may also be a contributing factor in her prevalent use of modes throughout her oeuvre. However, although her melodies are influenced by ancient traditions, she manipulates and embeds them in harmonically complex textures. Clarke’s combination of past and contemporary techniques can be clearly observed in O Vis Aeternitatis (2020),1 her choral setting of a text by Hildegard of Bingen (1098–1179), which the medieval composer also set as a chant melody.

The original responsory forms the opening of Hildegard’s song cycle, Symphonia (c. 1150).2 The text celebrates the Creator as the ‘power of eternity’, opening with a prayer to God, before focusing on the Incarnation, which the saint believed to be ‘the pivotal moment in which creation reached its perfect and predestined trajectory’ (Campbell and Lomer 2014). Religious historian Barbara Newman summarises the ‘grandiose and simple theme’ of the text as ‘the fulfilment of God’s eternal design through creation by the Word and recreation by the Word-made-flesh’ (Newman 1988, p. 267). The refrain, which focuses on the cleansing of ‘his garments’ (‘indumenta ipsius’), from ‘greatest suffering’ (‘maximo dolore’), can be interpreted as the spiritual cleansing of the body (Newman 1988, p. 268). As Campbell and Lomer note, Hildegard cleverly positions the repetition of the refrain to move from initially contemplating ‘the cleansing of Adam’s flesh from the suffering of sin to the cleansing of Christ’s flesh by his own human suffering’ (Campbell and Lomer 2014). The final verse presents a joyful celebration of faith in the Trinity, praising the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit (‘Gloria Patri et Filio et Spiritui Sancto’).

| O Vis Aeternitatis text3 | |

| O Vis Aeternitatis que omnia ordinasti in corde tuo, per Verbum tuum omnia creata sunt sicut voluisti, et ipsum Verbum tuum induit carnem in formatione illa que educta est de Adam. R. Et sic indumenta ipsius a maximo dolore abstersa sunt. V. O quam magna est benignitas Salvatoris, qui omnia liberavit per incarnationem suam, quam divinitas exspiravit sine vinculo peccati. R. Et sic indumenta ipsius a maximo dolore abstersa sunt. Gloria Patri et Filio et Spiritui sancto. R. Et sic indumenta ipsius a maximo dolore abstersa sunt. Hildegard of Bingen | O Power of Eternity By all things in order in your heart, and through your Word, all was created according to your will; and your very Word dressed as flesh, in that same shape which was drawn from Adam. R. And so his garments, through greatest suffering, were cleansed. V. O how great is the goodness of the Saviour, who has freed all beings by his own Incarnation, which divinity breathed into being without the chains of sin. R. And so his garments, through greatest suffering, were cleansed. Glory be to the Father and to the Son and to the Holy Spirit. R. And so his garments, through greatest suffering, were cleansed. Translation: Rhona Clarke |

Clarke’s a cappella setting (SATB) of Hildegard’s text consists of two verses, each followed by a refrain, and a finale comprising an exuberant fugal treatment of the doxology ‘Gloria Patri et Filio et Spiritui Sancto’ (‘Glory be to the Father, and to the Son, and to the Holy Spirit’). O Vis Aeternitatis was commissioned by the arts organisation Music for Galway to form part of their Abendmusik concert series, and was premiered by the Irish ensemble Resurgam in November 2020. This series was inspired by concerts of the same name in Lübeck, Germany, during the seventeenth century, which provided the German town’s audiences with the ‘opportunity to hear vocal music on religious themes but in a non-liturgical context’ (Music for Galway n.d.). It is significant that a connecting thread throughout the 2020 concert series was ‘Sacred meets secular, old meets new’, which resonates with Clarke’s writing.

For this commission, Clarke sought a Latin text that did not feature in Mass settings but that could be performed in either liturgical or concert contexts (R. Clarke 2025). In her search for a suitable text, she explored the work of Hildegard and found O Vis Aeternitatis to be particularly ‘dramatic’ and ‘a very strong text’ (Music for Galway 2020a). She explains how the ‘visceral’4 power of Hildegard’s words appealed to her ‘rather than any theological aspect’ (Music for Galway 2020a).5 O Vis Aeternitatis formed the focal point of the concert ‘Resounding Landscape’, which took place on the feast of St Cecilia. The programme was inspired by the joining of heaven and earth (Music for Galway 2020b, p. 51), and Clarke’s piece featured alongside Henry Purcell’s Welcome to all the Pleasures (1683) and George Frederic Handel’s Dixit Dominus (1707).6 O Vis Aeternitatis was subsequently selected as one of three Irish works to be performed at the International Society for Contemporary Music’s World New Music Days festival in the Faroe Islands in June 2024, highlighting the international recognition for Rhona Clarke and her choral music.7

3. Score Analysis

3.1. Melodic, Harmonic, and Textural Structures

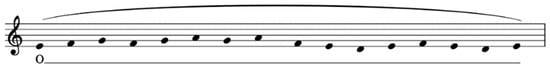

It is evident from the opening bars of the music that the powerful character of the text is a commanding factor in Clarke’s O Vis Aeternitatis. The composer foregrounds the visceral spirit of Hildegard’s words through her textural and harmonic organisation of the music. She uses the gradual expansion of texture, antiphonal techniques, dissonant harmonic language, and contrasting vocal timbres to spotlight moments of dramatic escalation and spiritual importance in the text. The measured intensification of musical parameters is immediately apparent in the introduction of the work, which sets the titular text ‘O Vis Aeternitatis’ (‘O Power of Eternity’; bb. 1–9). Clarke draws closely on Hildegard’s Phrygian melody, opening the piece with a four-bar melisma that begins and ends on a unison E, reflecting the original chant (Figure 1). The composer has overtly acknowledged how Hildegard’s melody, with the ‘beautiful melisma on ‘O’ […] very definitely influenced the opening of this particular setting’ (Music for Galway 2020a). Quotation of chant is a common feature of sacred choral composition across the ages and continues to serve as a stimulus for contemporary composers in the formulation of content and structure. As Scottish composer James MacMillan asserts in relation to plainchant and other historical music, composers ‘have always taken fragments of material […] from elsewhere and breathed new life into them, creating new forms, new avenues and structures of expression’ (MacMillan 2000, p. 22). Clarke explains how the opening ‘O’ is a form ‘of expressing wonder […] This power that’s beyond our comprehension. A reverence in it for something that is far greater than human beings’ (R. Clarke 2025). Clarke’s interpretation calls to mind Jonathan Arnold’s assertion that music can ‘help us to perceive the reality and mystical truth of something greater’ than ourselves (Arnold 2019, p. 335).

Figure 1.

Opening of Hildegard of Bingen’s O Vis Aeternitatis.8

The ‘O’ vowel enables a fluid melismatic line, reflecting Clarke’s attraction to the sound of the Latin words and ‘how well their open vowels suit the voice’ (Fitzgerald 2022). The soprano and tenor present the opening phrase in unison, accompanied by the alto and bass’s E drone, a further emulation of early music and establishment of E as the tonal centre (Figure 2). The Phrygian quality of the melody generates an intense, otherworldly sound through its minor second beginning, effectively capturing the mystery of the beyond. Furthermore, as Jeremy Begbie describes, the presence of a drone in music represents ‘the eternal’; with chant, this sustained sound forms ‘an umbilical cord’ to the sacred’ (Begbie 2000, p. 136). Clarke’s use of Hildegard’s opening chant, accompanied by a drone, evokes a sense of the spiritual and eternal, drawing the listener into her compelling sound-world.

Figure 2.

Rhona Clarke, O Vis Aeternitatis introduction, bb. 1–4. © 2020 Rhona Clarke. Reprinted with permission.

Following the unison E in bar 4, each voice ascends with Clarke’s characteristic use of glissando to form a fortissimo E–B harmony, maintaining a sense of the archaic through the open fifth.9 The voices proceed homophonically, with the phrase’s penultimate harmony creating a dissonance of two stacked fourths, B–E–C–F#, the soprano–alto tritone increasing the tension. Tenor and bass descend with glissandi to the E–B fifth, while the upper voices resolve to an octave on E, avoiding a definitive tonality with the open harmony (bb. 8–9). Clarke employs vocal glissandi to conjure an ‘otherworldly feeling’, further accentuating the power of the Divine in the text (R. Clarke 2025). The introductory piano melismatic phrase and succeeding fortissimo homophony heard in the initial nine bars are restated at the beginning of the second verse (bb. 56–64), on a similar statement of veneration (O quam magna est benignitas Salvatoris—‘O how great is the goodness of the Saviour’). According to Newman, a salient feature of Hildegard’s style ‘is her fondness for the grand gesture’, with the majority of her songs beginning with the ‘solemn apostrophe’—‘O virga ac diadema’ or ‘O victoriosissimi triumphatores’, for example, expressing awe at God’s power and grace (Newman 1988, p. 40). Clarke’s repetition of the opening musical material highlights her manipulation of form and texture to indicate a new musical section, creating a sense of coherence, as well as to underline Hildegard’s continued influence on her setting, and moments of significance, most notably text that directly exalts the Divine.

A consistent harmonic feature throughout the work is the conclusion of phrases and sections with open chords, preserving the modal framework and avoiding conventional cadence points (Table 1). The composer’s evasion of definitive tertian chords is a common trait throughout her oeuvre, with the use of open dyads particularly prevalent in her lower textures and in settings of medieval texts, such as Hildegard’s, and Christmas carols.10 The intensification of dynamics from piano to fortissimo; the expansion of vocal register (E2–G5); and the contrasting open and dissonant harmonies, with glissandi, in the introduction to both verses suggest that Clarke endeavoured to create an emotive, powerful sonority, highlighting the potency of the Divine, while foregrounding the Abendmusik theme of combining the old and the new.

Table 1.

O Vis Aeternitatis, harmonic conclusions (Bar numbers in yellow; Refrain in purple).

A significant aspect of Clarke’s textural approach in O Vis Aeternitatis, as well as her other recent works such as Ave Atque Vale (2017) and It Matters (2021), is the barren, discordant tapestry of repeated and sustained notes, combined with Sprechstimme, which gradually augments to align with the text’s dramatic development. Following the rousing Phrygian introduction, a textural shift occurs with a recitative-like phrase unfolding in the alto at a piano dynamic, centred on E, with Sprechstimme in the tenor and bass (bb. 10–12, Figure 3). The cross-headed notation within the work alternates between recitation of repeated E tones and minor third undulations between E and G, which should be ‘varied […] as per natural speech inflections’ (R. Clarke 2020). The sudden reduction in dynamics and texture to the alto’s unison singing, with timbral contrast provided by the lower voices’ Sprechstimme, distinguishes this section of text from the powerful introduction of adoration. While the syllabic recitation reflects the rhythm of plainchant, maintaining a sense of the past and an impression of prayer, the use of the contemporary vocal technique Sprechstimme ensures the piece ‘sounds of our time’ (R. Clarke 2025). Additionally, Clarke’s shift to unadorned unison singing engenders what Levy calls an ‘aura of authoritative control’ (Levy 1982, p. 507)11, highlighting her respect for ‘the sound of the words’, ensuring textual clarity throughout (R. Clarke 2025).

Figure 3.

O Vis Aeternitatis, bb. 8–14. © 2020 Rhona Clarke. Reprinted with permission.

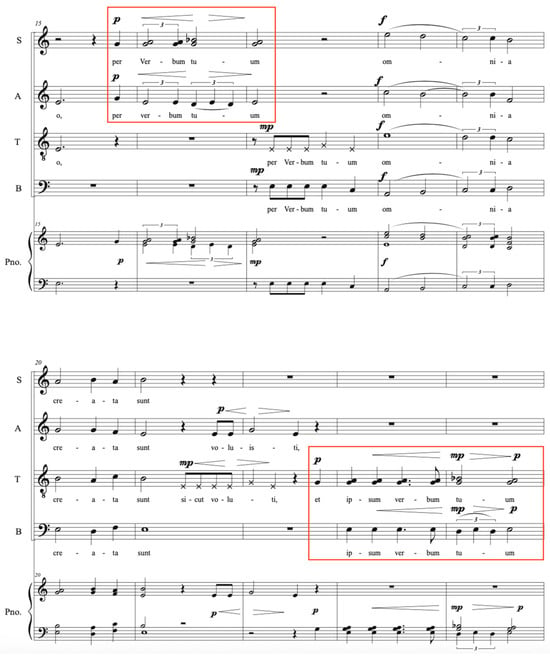

Minimal alterations transpire in the melodic statement of ‘que omnia ordinasti in corde tuo’ (‘By all things order in your heart’), with chromatic movement to neighbour tones, and alto and tenor conclusion on E in bar 15. This is followed by antiphonal dialogue between the upper and lower voices on the text ‘per Verbum tuum’ (‘by your Word’) in bars 15 to 17 (Figure 4), a common feature in Clarke’s wider output, creating timbral contrast within the bare texture. Clarke effectively expands the harmonic framework in the upper SSA texture with the sopranos’ unison G extending to a major second, and then a minor third interval, before contracting to a major second (G–A), with minimal melodic motion in the alto’s triplet undulation between E and D. This harmonic passage is imitated by the tenors and bass on the same text, ‘Verbum tuum’, in bars 23 and 24, creating symmetry within the work and connecting the motif directly with the text, as well as generating a distinctive ‘Clarke’ sound with sung and spoken text in close proximity.

Figure 4.

O Vis Aeternitatis, bb. 15–24 (repeated motif in red). © 2020 Rhona Clarke. Reprinted with permission.

A return to SATB homophony occurs in bars 18 to 21 on ‘omnia creata sunt’ (‘all was created’), the extension of the voices’ ranges and forte dynamic accentuating the modification of texture. The contrary motion between the bass and upper voices on the melismatic first syllable of ‘omnia’ demonstrates Clarke’s idiomatic choral writing, with each part moving predominantly by step. The elongation of the open vowel is a further indication of Clarke’s understanding of the inflection of the Latin language and her attraction to its natural sounds. The medieval choral sonority re-emerges in the conclusion of the phrase in bars 20 to 21, the tenor and bass moving in parallel open fifths (E–B; D–A; F–C), and concluding with a return to the open E–B harmony with soprano and alto, maintaining the E Phrygian modality. Clarke’s manipulation of the texture, from the preceding stark, almost monophonic framework to denser homophony at ‘omnia creata sunt’ calls to mind Wallace Berry’s observation on the significance of such textural shifts: ‘Within structural segments both large and small, the rate at which texture changes in the course of progression and recession is a vital aspect of expressive effect’ (Berry 1987, p. 201). All voices unite and progress in a homorhythmic manner, reflecting the declaration that ‘all’ was created by God. In a compositional era where, as composer Andrea Ramsey notes, ‘perhaps too great a percentage of our works comprise slow homophony’ (Denney 2019, pp. 13–14), Clarke exhibits a continuous manipulation of texture, preserving complete homophony or busier counterpoint for significant moments in the text and music.

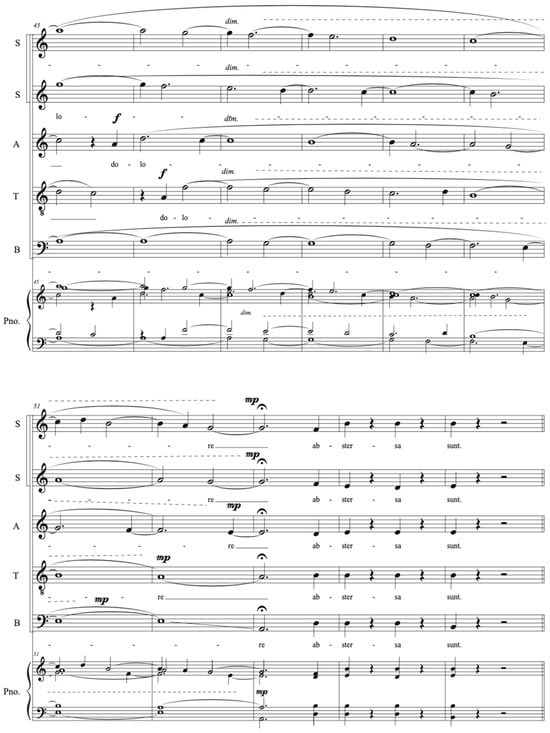

Mark Fitzgerald contends that ‘[S]inging out a word or phrase within the larger text for expressive expansion is a common compositional strategy’ in Clarke’s choral work (Fitzgerald 2022). The composer herself asserts that ‘[W]hen you are setting a text, you cannot bring out every single thing […], so you must focus on very particular aspects’ (Music for Galway 2020a). Within O Vis Aeternitatis, Clarke states that she chose to spotlight the power of the opening line and the aspect of suffering in the refrain (Music for Galway 2020a). The most literal communication of text in the work materialises on the phrase ‘a maximo dolore, abstersa sunt’ (‘through greatest suffering, were cleansed’), outlining ‘the sorrow introduced by Adam’s sin’ (Campbell and Lomer 2014), which was subsequently redeemed through Jesus’s human suffering (bb. 40–55; 87–101; Figure 5). Following the dissonant, bare texture of repeated and sustained tones and Sprechstimme, the piano legato alto and tenor ascend melismatically in sixths on ‘maximo’, gradually broadening the melodic range, in preparation for the impassioned, five-part discordant outburst on ‘dolore’. Forte octave leaps (A–A’) in quick succession in the first soprano and bass (bb. 43–44) instigate similar leaps across the texture,12 embodying a cry of pain, with each voice’s subsequent stepwise descent at independent rhythmic intervals creating harsh suspensions that similarly evoke pain and suffering. Major and minor seconds between the sopranos, and soprano 2 and alto, create a jarring tone, before resolving to major and minor thirds. According to Clarke, her setting of the refrain is ‘very definitely an expression of pain […] The whole impetus there is on […] the idea of pain as a very visceral thing’ (Music for Galway 2020a).

Figure 5.

O Vis Aeternitatis, bb. 45–55. © 2020 Rhona Clarke. Reprinted with permission.

This dramatic display of dissonance, which gradually diminishes in dynamics to mezzo-piano, concludes in bars 52 to 53, with the bass’s descending glissando from E3 to A2 forming a sustained open A seventh chord at the end of the phrase. The lack of the third is a further indication of Clarke’s evasion of definitive tonality, preferring a modal sound world. A striking harmonic and textural contrast follows, with the homophonic utterance of ‘abstersa sunt’ (‘cleansed’) disjointed by crotchet rests between the chords. Tenor and bass repeat a major sixth (D–B) interval below the alto and sopranos’ minor third (D–F), which expands to a fifth (E–B), and then a tense D–E–B chord, before returning to the fifth, all voices forming an open B–E–B harmonic conclusion. The tenor and first soprano’s repeated B, and alto’s repeated E, with minimal movement in the other voices, create a sense of melodic stasis, the stark harmonies patently contrasting with the previous texturally dense dissonance. The wider intervals and crotchet rest punctuation may be interpreted as illustrating the cleansing of Jesus’s ‘garments’, or body, purifying the tonal palette following the jarring suspensions in the choir’s expression of ‘greatest suffering’. The subsequent three-beat silence intensifies the conclusion of this section and the emotive weight of the text. Theorist Robert Hines contends that ‘[t]he importance of silence should not be underestimated; it is a strong, malleable ally when developing musical ideas’ (Hines 2001, p. 69). Clarke’s application of extended rests prolongs the tense atmosphere of the preceding discordant outburst, while also allowing respite before the beginning of a new section. Furthermore, the silence is imbued with a spiritual quality, not unlike the sacred music of Arvo Pärt (b. 1935), who employed rests between phrases and sections to allow the listener to ‘absorb the aural and spiritual impact of the moment’ (Muzzo 2008, p. 30).

3.2. Self-Allusion: Connecting Sound and Emotion

In addition to Clarke’s paraphrasing of Hildegard of Bingen’s chant within O Vis Aeternitatis, it can be argued that the composer has alluded to her own previous writing, specifically in the first verse. The melodic, harmonic, and textural structures of another of Clarke’s pieces, Ave Atque Vale (2017), exhibit distinct similarities to O Vis Aeternitatis, most notably the sparse tonal and textural framework, as well as the inclusion of Sprechstimme. Whether this self-allusion is deliberate or mere coincidence is uncertain, but an analysis of her compositional approaches in both works can help to elucidate this matter. In bars 29 to 36 of O Vis Aeternitatis, the soprano repeats A, rising and falling through B♭ and C through ‘que educta est’ (‘drawn from’), before culminating in a stepwise ascent to a secundal C–D interval on ‘Adam’. This ascent is accompanied by a fragmented pattern of G–D fifths in the tenor and alto, supported by an E♭ moving to D in the bass. The apex of this section features a cluster of B♭, C, and D in the alto and sopranos with F in the bass, descending through glissandi to a unison D with Sprechstimme B in the bass (Figure 6). This section relates to the Incarnation of Jesus, culminating in the upper tone cluster and descending glissandi through the first syllable of ‘Adam’, which is followed by undulating seconds (E4–D4) in the alto on ‘educta est’, echoed by the bass in wider intervals (C3–A3–D3–A3–E3). According to Campbell and Lomer, Hildegard’s ‘pairing of Adam—the first human, whose Fall broke […] creation—and Christ—the God-human, whose Incarnation restored it—is commonplace in Christian thought, rooted in the writings of St. Paul (e.g., Romans 5:12–21 and 1 Corinthians 15:21–50)’ (Campbell and Lomer 2014). Although Clarke has stated that she was not drawn to the theological or doctrinal aspects of the text (Music for Galway 2020a), the gradual stepwise ascent to a tone cluster and subsequent glissando descent are highly dramatic and could be interpreted as a depiction of Adam’s Fall.

Figure 6.

O Vis Aeternitatis, bb. 29–39. © 2020 Rhona Clarke. Reprinted with permission.

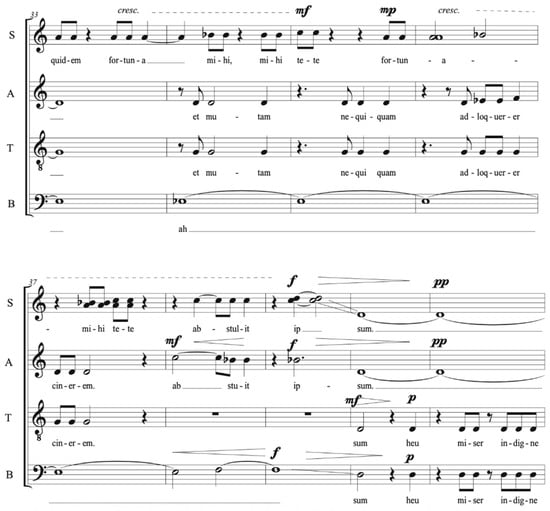

It is striking that in the piece Ave Atque Vale,13 Clarke uses notably similar textural and harmonic language to that in the above passage from O Vis Aeternitatis. The text of Ave Atque Vale, by the Roman poet Catullus (c. 84–54 BCE), is an elegy addressed to his brother, who was killed in war. In Clarke’s setting, she pursues a minimalist approach to developing intensity while capturing the despondent mood of the text. Textural density and dynamics gradually expand in tandem with the increasingly dissonant language, conveying the growing despair of Catullus as he bids farewell to his brother. The music thus reflects Peter Sacks’s interpretation of an elegy as having ‘a measured pace and direction’, like a funeral procession (Sacks 1987, p. 19). At bar 29, the soprano follows an almost identical trajectory to O Vis Aeternitatis, gradually ascending from A to D, supported by the fragmented open G–D fifths in the tenor and alto, and an E♭ pedal tone in the bass (‘Quandoquidem fortuna mihi tete abstulit ipsum’—‘Inasmuch as fate takes you, even you, from me’). The climax of this subsection is signalled by the shift to a sustained F in the bass, while the sopranos ascend to a secundal divisi (C–D), creating a tone cluster with the alto’s B♭ on ‘ipsum’ at a forte dynamic (b. 40). This tense sonority of close intervals in the upper texture, creating a B♭ ninth in second inversion, dissipates in a descending glissando in the soprano and bass, perhaps representing Catullus’s outpouring of grief, with all voices then resolving to D (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Ave Atque Vale, bb. 33–41. © 2017 Rhona Clarke (R. Clarke 2017). Reprinted with permission.

The texture and harmonic language are practically indistinguishable in the above excerpts, and both gradually build in intensity through rising dynamics and pitch. While the respective moments in question differ greatly in text and narrative content, both convey a notably dramatic character, which likely prompted Clarke to use almost identical musical elements. These moments of heightened drama demonstrate how Clarke’s compositional palette is applied to diverse texts and in different contexts to create an emotive, impassioned sound. Considering the timeframe within which these works were composed, Ave Atque Vale was one of Clarke’s first choral works to feature extended vocal techniques, which, she says, followed from similar approaches in her instrumental work SHIFT (2013) (The Contemporary Music Centre 2022), and O Vis Aeternitatis was one of the first choral pieces she wrote after Ave Atque Vale. While she has not referred specifically to the excerpts highlighted above, Clarke has stated that her setting of Hildegard’s text ‘came out of the experience with Ave Atque Vale’ (R. Clarke 2025). Her utilisation of strikingly similar harmonic and textural elements across these diverse sacred and secular works reveals a coherence of compositional voice, as she employs similar intensifying sonorities at emotionally powerful points in each piece.

3.3. Extending the Timbral Palette

Both O Vis Aeternitatis and Ave Atque Vale feature extensive use of Sprechstimme and glissandi, intensifying their dramatic sound worlds. Their application of contemporary choral techniques reflects Clarke’s desire to ‘create something that I have not heard before, either as a listener or as a composer’ (Chamber Choir Ireland 2023). An overview of Clarke’s choral output since 2016 reveals an increased exploration of vocal timbre, highlighting further development of her compositional voice. These extended techniques in themselves are not new within contemporary choral music, with ‘Sprechgesang, shouting and whispering, laughter and crying, glissandi, […] sound production through inhalation and exhalation, vowel morphing, […] and nonsense syllables or phonemes’ being used by composers as a means of word painting and emotional expression (Crump 2008, pp. 3–4). Irish contemporaries such as Siobhán Cleary and Michael Holohan, as well as international composers such as Jaakko Mäntyjärvi, Jake Runestad, Katerina Gimon, and Caroline Shaw, incorporate extended vocal techniques into their choral works, continuing to diversify the performances of choral ensembles. These contemporary devices are used in a variety of ways, expanding composers’ creative and expressive toolkits while evoking the atmosphere of the texts that they set. However, their presence in sacred repertoire is relatively rare, particularly with regard to Sprechstimme.

Following brief forays into the use of extended techniques in Gloria (1989) and A Song for St Cecilia’s Day (1991, rev. 2020), Clarke began to integrate these devices consistently into her choral language after her instrumental work SHIFT (2013), which experimented with extending the parameters of instruments’ sounds and contrasting orchestral colours as ‘blocks of sound’ (R. Clarke 2014).14 In the period surrounding SHIFT, Clarke observed how ‘[A] ‘shift’ in language and style has emerged gradually in my own work resulting from, amongst other things, a return to electro-acoustic processes’ (R. Clarke 2014). In addition, she professes her attraction to ‘visual and musical works, which are bold and have confident strokes’, thus seeking to achieve this in her own musical language (R. Clarke 2014). As Clarke regularly composes for choirs of a high technical and expressive standard, such as Resurgam, which premiered O Vis Aeternitatis, and State Choir Latvija, opportunities to expand the timbral palette and textural complexity within her music are extensive. However, Clarke’s judicious compositional decisions, particularly in integrating extended vocal techniques, render her works accessible across a range of technical levels.

Having previously been reluctant to explore extended techniques in her choral settings, with minimal use of Sprechstimme only evident in A Song for St. Cecilia’s Day, Clarke began to combine ‘more speech patterns […], almost half-sung patterns’ with conventional vocals in pieces such as The Old Woman (2016), Ave Atque Vale, and It Matters (2021) (The Contemporary Music Centre 2022). As well as the aforementioned influences on her shift in choral writing, Clarke has also attributed this combination of different sounds to an increased confidence in her work as she has become older, no longer caring ‘what people think’ (RTÉ Lyric FM 2022). She further explains: ‘my thoughts on making something very definitely sound ‘of now’ might have triggered the use of extended techniques from […] 2016’ (R. Clarke 2025). Her synthesis of diverse timbres and techniques has resulted in innovative sound worlds that effectively capture the tone of the set texts and demonstrate her distinct compositional voice, underlining her established reputation as ‘an original and integer composer’ (Klein 2017).

The first instance of Sprechstimme in O Vis Aeternitatis occurs in the tenor and bass accompaniment of the alto’s almost monotone phrase ‘per omnia ordinasti’ (‘by all things in order’) at a piano dynamic in bars 10 to 12 (Figure 8). This exposed texture occurs after the homophonic fortissimo declamation of ‘O Vis Aeternitatis’, offering a distinct contrast in terms of dynamics, timbre, and textural density. As is the case with her orchestral work SHIFT, ‘[T]he concentration is on blocks of sound’ and opposites, which is apparent in the diverse, contrasting timbres within O Vis Aeternitatis (R. Clarke 2014). Following the presentation of the ‘old’—the traditional chant from Hildegard’s responsory addressing the ‘Power of Eternity’—the combination of the alto’s monotone syllabic text on E with the tenor and bass’s Sprechstimme establishes the reverent tone in a contemporary light. As this was a commission for Music for Galway’s ‘Resounding Landscape’ concert, it is possible that Clarke wished to include sounds reflecting the concert’s theme through her use of different vocal timbres, as opposed to simply painting specific words or phrases within the text. The power of the Divine is illustrated through traditional compositional means, with the elaborate melismatic chant and fortissimo homophonic declamation of praise, as well as the concluding fugal texture. In a more contemporary manner, Clarke combines extended vocal techniques with the chanting of text, reminiscent of psalm tone singing, in a stark texture that could be deemed to represent the mortal, earthly aspect of the text—those praising the Saviour (Salvatoris) through prayer.

Figure 8.

Sprechstimme in O Vis Aeternitatis (bb. 8–12). © 2020 Rhona Clarke. Reprinted with permission.

An effective use of aleatoric Sprechstimme in the setting of the responsory occurs in the basses’ expression of ‘sine vinculo peccati’ (‘without the chains of sin’) in bars 81 to 83. While the tenor undulates in crotchet triplets between E and D, the basses enunciate the words at ‘individual entries and durations’, the pitch direction and intensity indicated by a dense triangular graphic (Figure 9). As is common with sectional conclusions in the work, Clarke has reduced the texture and dynamics, closing with a fermata. This ending allows the spoken text to resound before the return of the refrain’s more structured, yet initially bare, texture of a unison E and Sprechstimme. The contrasting timbres and independent expression of text at the end of this verse effectively convey one uninhibited by the bondage of sin; the tenor and bass voicing likely representing the figure of Jesus. This significant moment is further underlined given its occurrence immediately after a homophonic SATB declamation of the same text. The prolonged rest that follows the indeterminate spoken text also allows the voices to echo before proceeding to the new phrase, creating a distinction between the verse and response. The use of surging collective speech at individual tempi for ‘sine vinculo peccati’ could be interpreted as the sound of chains, and then those chains falling away (mf reducing rapidly to pp), thus freeing all from sin (‘omnia liberavit’). Clarke reserves this swelling aleatoric spoken text, solely in the lowest voices, for this extraordinarily literal and significant moment expressing the core Christian belief that Jesus was born without sin in order to save humanity (2 Corinthians 5:21; 1 John 3:5).

Figure 9.

Aleatoric spoken text, O Vis Aeternitatis, bb. 79–83. © 2020 Rhona Clarke. Reprinted with permission.

3.4. Polyphonic Expression of Devotion

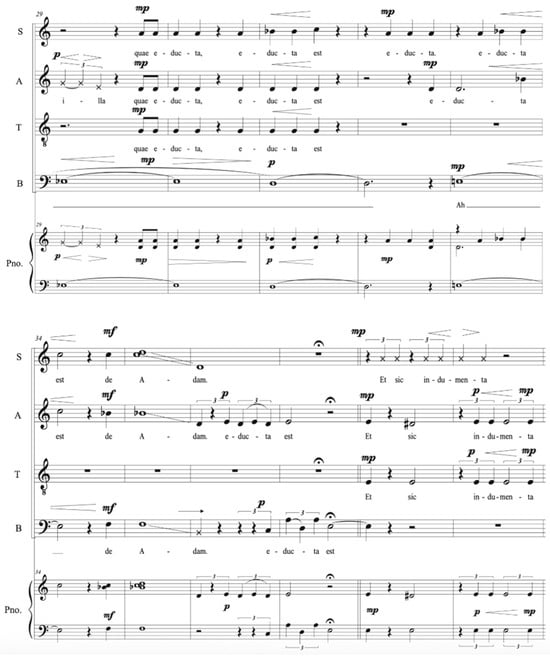

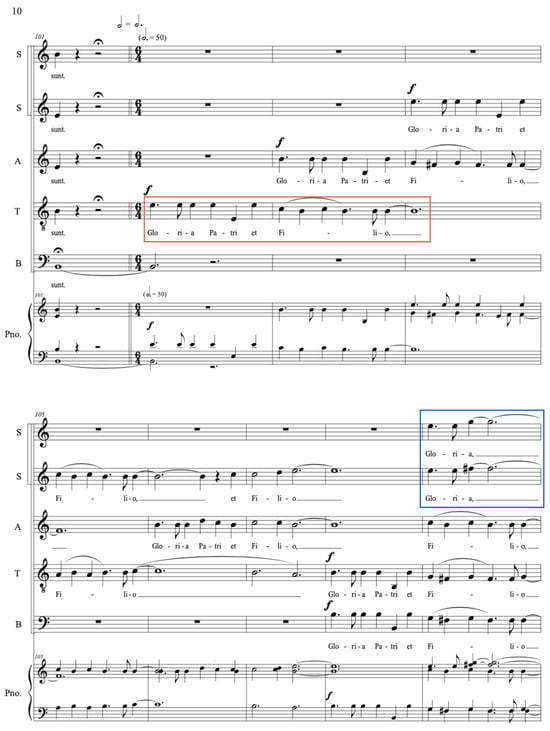

In what could be deemed a significant change of character from the preceding refrain, the culmination of Clarke’s manipulation of texture occurs in the final section of O Vis Aeternitatis, with the fugal setting of the doxology ‘Gloria Patri et Filio’ (‘Glory be to the Father and to the Son’; bb. 102–132). The tenor introduces the forte E Aeolian subject in 6/4, fluctuating across the octave between E4 and E3 on ‘patri et’, before oscillating a semitone between C and B on ‘Filio’ (‘Son’). The alto presents the answering phrase a bar later on the dominant B, reflecting the conventions of fugue writing (Figure 10). The melodic undulation in minor (and major) seconds is a compositional trait applied frequently across Clarke’s oeuvre, the composer acknowledging her fondness for the tense, clashing sound of the adjacent notes (R. Clarke 2025).15 More broadly, musicologist William Kimmel notes how the minor second interval in music ‘possesses greater energy and intensity and consequently internal momentum which in melodic progression accelerates in the direction of the second tone’ (Kimmel 1980, p. 46). Within the fugue of Clarke’s piece, the melodic oscillation embellishes the first syllable of ‘Filio’, recalling the melismatic introduction of both verses. This feature also helps to propel the unceasing melodic motion and exultant character of the fugue, a striking contrast to the predominant chant-style recitation and dissonant tension of the preceding exposed homophony.

Figure 10.

Fugal subject (red) and counter-subject (blue), O Vis Aeternitatis, bb. 101–109. © 2020 Rhona Clarke. Reprinted with permission.

The contrapuntal texture continues to expand with the second soprano and bass entries in bars 104 and 108, respectively. Unlike the previous sections of prolonged rests, there is no respite within the fugue, with an incessant progression of interweaving phrases across the five-part texture. Both sopranos introduce a rising ‘Gloria’ counter-subject in bar 109, increasing the complexity of the counterpoint and spirited atmosphere of the fugue. Both voices begin on E5, before sustaining a minor second dissonance of F#–G on the final syllable for seven beats. This motif is repeated in the same voices in bars 110 and 111, with the discord maintained for six beats. The secundal interval conveys a sense of coherence and tension throughout the work, with Clarke establishing the second as a salient harmonic and melodic feature from the outset.

Clarke has recalled how her decision to set this text of praise as a fugue was ‘intuitive’ and naturally suited the structure of the piece (R. Clarke 2025). In composing her contemporary setting, Clarke recognised the doxology as a separate component of Hildegard’s text (R. Clarke 2025). From a theological perspective, the doxology is a separate prayer, not originally composed by Hildegard; the doctrine of the Trinity is a central facet of the Christian faith, formally articulated in the Nicene Creed of 325 CE. Clarke effectively demonstrates this textual distinction through the transition to a lively contrapuntal framework that contrasts with the predominantly homophonic textures of the preceding music. The textural transformation, as well as the shift in mood, modality, and metre at this point, imply the composer’s sensitivity to the distinction between Hildegard’s text and the pre-existing doxology. The religious and historical significance of the doxology is well known, certainly to someone of Clarke’s cultural milieu, and it is plausible that her awareness of its distinct theological identity impacted her compositional and structural decisions in this section. In any case, the juxtaposition of the historical fugal form with the harmonic and timbral boldness of Clarke’s more contemporary characteristics points to the eclectic nature of her compositional style.

Clarke’s decision to include a fugue may also have been influenced by the commission’s context. As Music for Galway’s Abendmusik series was inspired by its seventeenth-century German counterpart, and the premiere performance of O Vis Aeternitatis featured alongside Baroque sacred works by Purcell and Handel, Clarke may have intended to reflect this era through her intricate polyphonic counterpoint. While fugues are occasionally used by contemporary composers such as James MacMillan (b. 1959), John Rutter (b. 1945), and Eoghan Desmond (b. 1989), such writing is not a prevalent feature in Clarke’s overall choral writing, which makes its use here all the more noteworthy. However, her fugal setting of the satirical text ‘Dear Santa’, the first movement of A Bit of Nonsense (2020), in the same year as O Vis Aeternitatis, suggests that Clarke could have been exploring this formal technique at the time. This contrapuntal approach, in tandem with Clarke’s modal writing, allusion to plainchant, and synthesis of dissonant and archaic harmonic palettes, is a notable reflection of the concert series’ theme of old meeting new. She draws on the old, but in a distinctly contemporary style, for a modern, non-liturgical context. As Clarke states.

I feel free to take anything from the past, any part of the past, from early Middle Ages right down [to the present] and see what can be done with that. […] The tradition is always there. In what results, there is always some aspect of historical music’ (R. Clarke 2025).

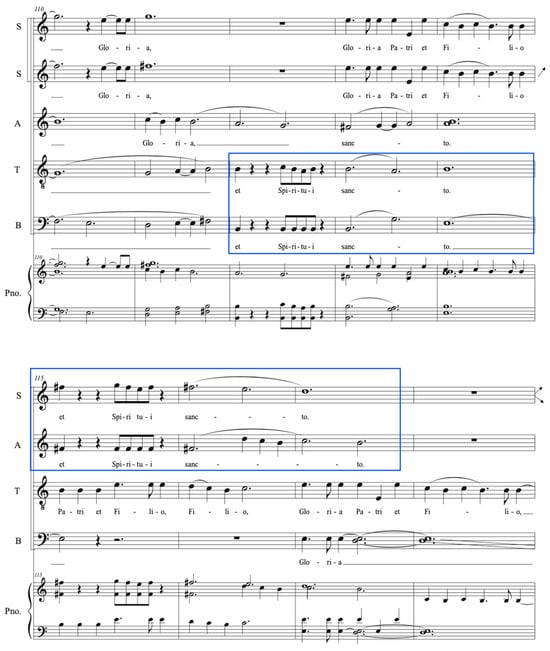

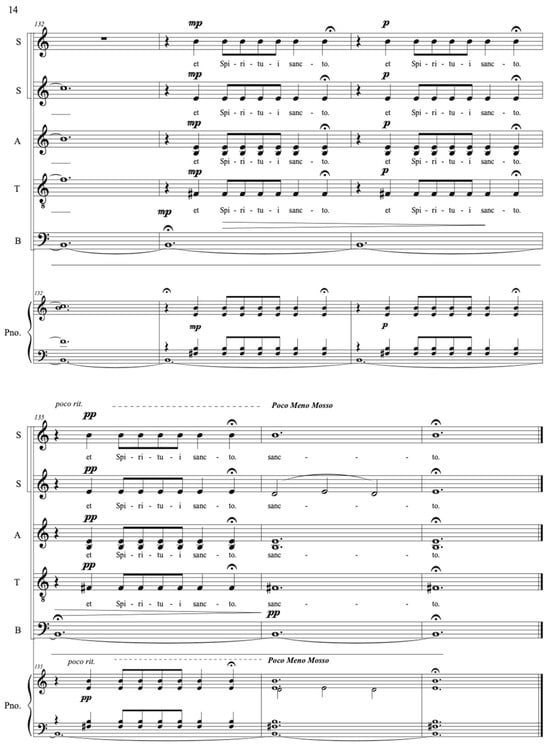

For the final segment of the doxology, the tenor and bass introduce a new theme in bar 112 on ‘et Spiritui sancto’ (‘and the Holy Spirit’), with a two-beat and one-beat rest fragmenting the text on each appearance. While the bass repeats B, the tenor ascends a semitone from B to C before falling by step to A and resolving to B. The static motion of one voice as the other moves incrementally is a common harmonic trait in this work, and in Clarke’s overall choral output, highlighting her proclivity for alternating dissonances and consonances.16 The steady repeated notes, most often in an inner voice, convey a chant-like quality, which is effective in this setting of a medieval religious text. ‘sancto’ is elongated as dotted minims and semibreves, moving from an octave to a secundal interval (G–A) and resolving on the characteristic open fifth (E–B), as the sopranos reinstate the E Aeolian subject in the upper texture (bb. 113–14; Figure 11). This brief motif is imitated on F# by the soprano and alto in bars 115 to 117, with slight melodic and rhythmic variation of the ‘sancto’ idiom, as the lower voices continue their independent lines.

Figure 11.

O Vis Aeternitatis, bb. 110–118 (‘et Spiritui sancto’ motif in blue). © 2020 Rhona Clarke. Reprinted with permission.

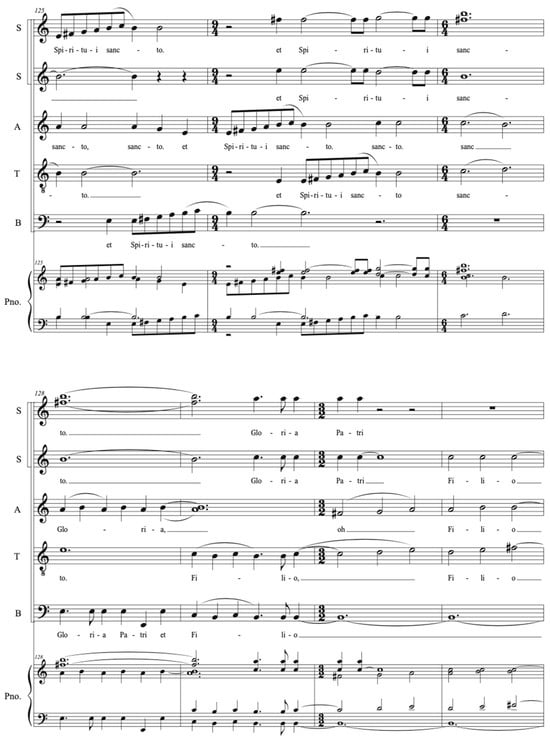

An increased sense of urgency unfolds from bar 119 with the first soprano’s new imitative rising quaver countersubject in E Aeolian (‘et Spiritui sancto’), echoed across the texture at a three-beat distance (Figure 12). The stretto is counterbalanced with the tenor and bass’s inverted declamation of the ‘Gloria’ countersubject, which was initially presented by the sopranos in bar 109. Rather than the expected secundal dissonance at the close of the phrase, the bass’s F#3 forms a minor seventh with the tenor’s E4 (b. 120); the immediate repetition concludes with a minor second in divided tenors (B–C). The climactic point of the work coincides with the final presentation of the original subject in bar 128 in the bass, while the sopranos sustain an open B–F#–B harmony, and the alto and tenor engage in secundal undulations (A–B; C–B; Figure 13). Clarke indicates a shift in tone in bar 130 with the metrical change to 3/2, a return to reduced four-part homophony with augmented minim rhythms rising by step in the alto and tenor, and the B drone in the bass, which is sustained for the remainder of the piece. Clarke skilfully alters the rhythmic, textural, and harmonic elements at the close of the fugue, restoring the more reserved tone for the work’s conclusion.

Figure 12.

O Vis Aeternitatis, bb. 119–121. © 2020 Rhona Clarke. Reprinted with permission.

Figure 13.

O Vis Aeternitatis, bb. 125–131. © 2020 Rhona Clarke. Reprinted with permission.

Chant-style recitation characterises the final five bars of O Vis Aeternitatis (bb. 133–37) on the words ‘et Spiritui sancto’. Following the vigorous polyphonic exaltation of the Trinity, the bass sings a B2 drone, establishing a more meditative, spiritual atmosphere. Clarke’s use of the drone in this section calls to mind James MacMillan’s stance on drones in choral music:

There’s something about the suspension of time with the use of a drone which can bring about a clearing of the ears, a new impetus to listening, a new way of listening to what is to come, a heightening of the tension, which opens the possibilities again to listen anew (MacMillan and McGregor 2010, p. 89).

The bass’s drone announces a new section in the music, ceasing the exuberant fugue and urging the listener to concentrate on the words, the Holy Spirit within the Trinity. The sustained quintal harmony of B–F#–C in bar 132 leads to the static SSAAT homophonic recitation of the prayer above the drone. The choir repeats ‘et Spiritui sancto’ three times syllabically as the bass continues to sustain an ‘o’ vowel on B, each statement diminishing in dynamics from mezzo-piano to pianissimo (Figure 14). The bass’s drone, forming an open fifth with the tenor’s F#, creates a sense of tonal stability and is redolent of medieval harmony; yet the stacked intervals of fifths and fourths (B–F#–B–E–B) are characteristic of contemporary choral writing, with the lack of resolution, particularly the conspicuous avoidance of a conventional triad, preserving a sense of mystery in the work’s conclusion.

Figure 14.

O Vis Aeternitatis, bb. 132–137. © 2020 Rhona Clarke. Reprinted with permission.

The notes of the final chord could be deemed a synthesis of the tonic (E) and dominant (B) in E Aeolian, the harmonic basis of the preceding fugue. Taking a semantic approach to analysis, the ambiguous harmony could be interpreted as expressing the synthesis of the divine and human aspects within the Christian Trinity and the Incarnation, the focal point of Hildegard’s text. The syllabic chanting on an unchanged chord, which notably lacks the definitive third, recalls the stripped sound of previous sections of the work’s verses, unifying its overall thematic and modal outline. The ambiguity of the closing section is further underscored by Clarke’s rhythmic treatment of the three iterations of ‘et Spiritui sancto’ (b. 133, b. 134, b. 135): having changed the time signature from 6/4 to 3/2 in bar 130, the composer in effect removes the expected potency of the triple metre by inserting a fermata that extends the final syllable of each homophonic expression of this closing text. The inconclusive harmonic and rhythmic treatment of the text at this point—underpinned by the drone—offers a significant distinction from the exuberance and rigour of the previous polyphony, demonstrating Clarke’s effective alteration of texture and melody to manifest a change of character, a lingering sense of mystery, and perhaps a bold divergence from traditional, less ambiguous representations of the Holy Trinity. By concluding enigmatically, leaving the work unresolved, Clarke puts her individual, contemporary stamp on this medieval sacred text.

4. Conclusions

O Vis Aeternitatis encapsulates Rhona Clarke’s distinct compositional voice and superlative craftsmanship, offering a compelling reimagination of an ancient sacred text for the twenty-first century. At a time when, as Libby Larson observes, ‘the current choral trend is in homophonic settings that allow for a beautiful color from the choir’ (Zeeman Rugen 2013, p. 88), Clarke’s compositional approach often creates a stark, visceral sound that prioritises direct expression over beauty. Colin Clarke contends that ‘Clarke’s achievement is to present something that is modern yet simultaneously ancient’ (C. Clarke 2022). The composer effectively synthesises past and contemporary techniques through her use of plainchant, modal inflections, open chords, dissonant language, extended vocal techniques, and amplified textural contrasts, which evoke the origins and essence of Hildegard’s responsory. The work incorporates the influences of older music, but does not sound traditional, instead generating and combining with contemporary harmonies and timbres in a carefully expanding textural framework that progresses with the drama of the text. The integration of extended vocal techniques such as Sprechstimme and glissandi in O Vis Aeternitatis exemplifies Clarke’s penchant for exploring diverse timbres and conveying the visceral quality of texts, and also demonstrates her assertion that, while using traditional elements, ‘it’s very important that a work sounds of our time’ (R. Clarke 2025). The composer’s use of chant-like tones combined with half-sung/half-spoken phrases, expanding to dense homophonic dissonance and polyphonic counterpoint at key moments, embodies the dramatic spirit of Hildegard’s devout text, portraying both the potency of the Divine and the human suffering of Jesus.

In reflecting a ‘power that’s beyond our comprehension, a reverence […] for something that is far greater than human beings’ (R. Clarke 2025), O Vis Aeternitatis demonstrates how, in the words of Jonathan Arnold, ‘sacred choral music is as powerful [and] compelling […] as it has ever been’ (Arnold 2014, p. xiv). With this captivating work, Rhona Clarke breathes new life into a medieval text not commonly set in contemporary choral music and finds a distinctive directness of expression that stands out from prominent trends in contemporary sacred composition, as noted by Larson above. She brings both her eclectic compositional style and her particular cultural background to bear on the piece, with her combination of harmonic language, old and new compositional approaches, and extended techniques standing as a model for composers in engaging with the reimagination of ancient source materials and with diverse and nuanced expressions of sacred words more broadly. Ultimately, her compositional style as evident in O Vis Aeternitatis results in a distinct and innovative sound world that contributes to her reputation as ‘one of Ireland’s most original contemporary composers’ (Verdino-Süllwold n.d.).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.S. and R.B.; methodology, L.S.; formal analysis, L.S. and R.B.; investigation, L.S. and R.B., resources, L.S.; data curation, L.S.; writing—original draft preparation, L.S. and R.B.; writing—review and editing, L.S. and R.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data was created or analysed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | State Choir Latvija. O Vis Aeterntatis [sic]. 2022. YouTube. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a5qM7PTZsxI (accessed on 9 June 2025). |

| 2 | Sequentia. O vis eternitatis. Hildegard von Bingen. 2017. YouTube. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_Vcv2HdApcs&list=RD_Vcv2HdApcs&start_radio=1 (accessed on 6 May 2025). |

| 3 | Rhona Clarke. 2020. O Vis Aeternitatis. Unpublished music score. |

| 4 | From interviews with the composer and our readings of the available sources on her piece O Vis Aeternitatis, we understand ‘visceral’, in this context, to mean expressing a deep, instinctive human emotion. According to our analysis, Clarke achieves a visceral character through compositional techniques such as clashing seconds and other dissonances, piercing suspensions (in the refrain), glissandi, and her distinctive combination of spoken and sung tones. |

| 5 | Despite the composer’s claim that ‘she is not a theologian and not knowledgeable in that area’ (R. Clarke 2025), Christian dogma within Hildegard’s text is highlighted by Clarke within the music. Given the composer’s Catholic education (Clarke attended Scoil Mhuire (Our Lady’s National School), Marlborough Street, in Dublin City Centre (1962–1970), followed by Maryfield College of the Cross and Passion Convent on the city’s north side until 1975 (Wright 1996)) and Irish context, where ‘being Catholic was part of the cultural air’ and ‘[R]eligious references were part of everyday communication’ (Inglis 2017, p. 24), it is highly probable that the composer has at least a general knowledge of the principal theological references found in O Vis Aeternitatis. |

| 6 | Purcell’s work is a setting of Christopher Fishburn’s text that celebrates music as divinely inspired. Dixit Dominus is a setting of psalm 110, which underlines the supremacy of Jesus, the Son of God. It is interesting that both Handel and Clarke’s works conclude with the doxology ‘Gloria Patri, et Filio, et Spiritui Sancto’. Clarke omitted the final refrain, perhaps to end on a more joyful, lively note as opposed to contemplating the great suffering of Jesus. |

| 7 | Clarke’s O Vis Aeternitatis was chosen to represent Ireland alongside Eric Egan’s in some or other Oasis (2014) for string chamber ensemble, and Francis Heery’s Towards A Soteriological Theory Of Bog Bodies (2023), for prepared piano, electric guitar, and fixed audio. |

| 8 | Transcribed by the author from the recording ‘O vis eternitatis’. Sequentia. 2017. YouTube. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_Vcv2HdApcs&list=RD_Vcv2HdApcs&start_radio=1 (0:10–0:20) (accessed on 6 May 2025). |

| 9 | Clarke has used glissando extensively in her choral works; for example, The Old Woman (2016), Ave Atque Vale (2017), Requiem (2020), It Matters (2021), Navigatio (2023), and Epitaph (2024). |

| 10 | Open harmonies at the ends of phrases are evident in Clarke’s Rorate Caeli (1994), Make We Merry (2014), and Glad and Blithe (2014). An open fifth (B–F#) in the tenor and bass on ‘Skin and bone’ also pervades the opening of The Old Woman (2016), a setting of a nursery rhyme. |

| 11 | Janet Levy refers to the use of unison, particularly within otherwise polyphonic contexts, as ‘laden with semantic significance […]. Unisons are often used to announce or to mark other structural moments or to rouse us from a kind of musical action to which we may have grown accustomed’ (Levy 1982, pp. 507, 509). |

| 12 | Soprano 2 ascends a minor seventh from A4 to G5, alto ascends a fourth from A4 to D5, tenor ascends a minor sixth from A3 to F4 (bb. 43–45). The melodic, harmonic, and textural structures of the refrain (a maximo dolore) are somewhat reminiscent of Allegri’s Miserere (1638), which Clarke acknowledges as an influence (R. Clarke 2025). |

| 13 | State Choir Latvija. Ave Atque Vale. 2022. YouTube. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=08c2cn3C9d8 (accessed on 17 June 2025). |

| 14 | Spoken tones are used minimally in Clarke’s choral work A Song for St Cecilia’s Day (1991); however, Clarke has acknowledged a lack of confidence in using extended techniques at that point in her compositional career, tending to shy away from these devices (Rhona Clarke’s Sempiternam|Culture File, RTÉ Lyric FM, 14 April 2022 (3:19–3:23). Available online: https://www.rte.ie/radio/podcasts/22087792-rhona-clarkes-sempiternam-culture-file/ (accessed on 6 May 2025)). |

| 15 | Melodic undulations, most commonly as major and minor seconds, also feature in The Old Woman, Ave Atque Vale, Navigatio, Requiem, ‘III. Multitasking’ (A Bit of Nonsense; 2020), It Matters, Veni Creator Spiritus (2010), The Kiss (2008), Salve Regina (2007), and Rorate Caeli. |

| 16 | See Ave Atque Vale, Requiem, ‘II. Busy’ (A Bit of Nonsense), Veni Creator Spiritus, The Kiss, Salve Regina, and A Song for St. Cecilia’s Day. |

References

- Arnold, Jonathan. 2014. Sacred Music in Secular Society. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold, Jonathan. 2019. Sacred Music in Secular Spaces. In Annunciations: Sacred Music for the Twenty-First Century. Edited by George Corbett. Cambridge: Open Book Publishers, pp. 325–35. [Google Scholar]

- Begbie, Jeremy S. 2000. Theology, Music, and Time. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, Wallace. 1987. Structural Functions in Music. New York: Dover Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, Nathaniel M., and Beverly Lomer. 2014. O vis eternitatis: Commentary. International Society of Hildegard von Bingen Studies. Available online: https://www.hildegard-society.org/2014/06/o-vis-eternitatis.html (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Chamber Choir Ireland. 2023. Instagram. Available online: https://www.instagram.com/p/CpiEmP3jvIR/ (accessed on 9 May 2025).

- Clarke, Colin. 2022. Meeting the Music of Rhona Clarke. Classical Explorer. Available online: https://www.classicalexplorer.com/meeting-the-music-of-rhona-clarke/ (accessed on 25 October 2024).

- Clarke, Rhona. 2014. Catching Fire. RTÉ National Symphony Orchestra Horizons Contemporary Music Series 2014. Available online: https://www.rte.ie/documents/orchestras/14-01-14-rhona-clarke.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Clarke, Rhona. 2017. Ave Atque Vale. Unpublished Music Score. Available online: https://www.cmc.ie/shop/ave-atque-vale (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Clarke, Rhona. 2020. O Vis Aeternitatis. Unpublished Music Score. Available online: https://www.cmc.ie/music/o-vis-aeternitatis (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Clarke, Rhona. 2022. The Music—Notes by the composer. In Sempiternam: Choral Music by Rhona Clarke. Edited by Māris Sirmais and State Choir Latvija. Vermont: Divine Art Recordings Group. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, Rhona. 2025. Interview by author with the composer Rhona Clarke. Zoom, January 10. [Google Scholar]

- Crump, Melanie Austin. 2008. When Words Are Not Enough: Tracing the Development of Extended Vocal Techniques in Twentieth Century America. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of North Carolina, Greensboro, NC, USA. Available online: https://libres.uncg.edu/ir/uncg/listing.aspx?id=204 (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- Denney, Alan. 2019. OURS TO SEE: Emerging Trends in Today’s Choral Compositions. The Choral Journal 60: 8–21. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26870101 (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Fitzgerald, Mark. 2022. Rhona Clarke: The power and physicality of the voice. In Sempiternam: Choral Music by Rhona Clarke. Vermont: Divine Art Recordings Group. Available online: https://divineartrecords.com/recording/sempiternam-choral-music-by-rhona-clarke/ (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- Hines, Robert Stephan. 2001. Choral Composition—A Handbook for Composers, Arrangers, Conductors and Singers. Westport: Greenwood Press. [Google Scholar]

- Inglis, Tom. 2017. Church and Culture in Catholic Ireland. Studies: An Irish Quarterly Review 106: 21–30. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/90001071?seq=1 (accessed on 17 June 2025). [CrossRef]

- Kimmel, William. 1980. The Phrygian Inflection and the Appearances of Death in Music. College Music Symposium 20: 42–76. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/40374079 (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Klein, Axel. 2017. Rhona Clarke: Stepping out of the Shadow. In A Different Game. The Fidelio Trio. Metiér. Available online: https://divineartrecords.com/recording/a-different-game-piano-trios-by-rhona-clarke/ (accessed on 3 April 2025).

- Lamont, Barbara. 2016. The Choral Music of Rhona Clarke. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, TX, USA. Available online: https://ttu-ir.tdl.org/items/c478fe37-b895-45e9-9443-f0015e071335 (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Levy, Janet M. 1982. Texture as a Sign in Classic and Early Romantic Music. Journal of the American Musicological Society 35: 482–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacMillan, James. 2000. God, Theology, and Music. New Blackfriars 81: 16–26. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/43250342 (accessed on 13 July 2025). [CrossRef]

- MacMillan, James, and Richard McGregor. 2010. James MacMillan: A conversation and commentary. The Musical Times 151: 69–100. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/25759502 (accessed on 9 May 2025).

- Music for Galway. 2020a. ABENDMUSIK 2 “Resounding Landscape” Zoom Interview with Rhona Clarke. YouTube. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m-R13qH3MPI (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Music for Galway. 2020b. Soundscapes. Available online: https://musicforgalway.ie/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/MfG1920_Brochure.pdf (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- Music for Galway. n.d. Abendmusik. Available online: https://musicforgalway.ie/abendmusik/ (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Muzzo, Grace Kingsbury. 2008. Systems, Symbols, & Silence: The Tintinnabuli Technique of Arvo Pärt into the Twenty-First Century. The Choral Journal 49: 22–35. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/23557279 (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Newman, Barbara. 1988. Saint Hildegard of Bingen: Symphonia—A Critical Edition of the Symphonia armonie celestium revelationum [Symphony of the Harmony of Celestial Revelations]. New York: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- RTÉ Lyric FM. 2022. Rhona Clarke’s Sempiternam|Culture File. Available online: https://www.rte.ie/radio/podcasts/22087792-rhona-clarkes-sempiternam-culture-file/ (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Sacks, Peter M. 1987. The English Elegy: Studies in the Genre from Spencer to Yeats. Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- The Contemporary Music Centre. 2022. Amplify #64: Rhona Clarke on Her New Choral Album ‘Sempiternam’. Available online: https://www.cmc.ie/amplify/episode-64 (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Verdino-Süllwold, Carla Maria. n.d. Fanfare. Divine Art Recordings Group. Available online: https://divineartrecords.com/review/fanfare-reviews-rhona-clarke-a-different-game/ (accessed on 13 May 2025).

- Wright, David C. F. 1996. Rhona Clarke. Available online: https://www.musicweb-international.com/rclarke/index.htm (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Zeeman Rugen, Kira. 2013. The Evolution of Choral Sound: In Professional Choirs from the 1970s to the Twenty-First Century. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ, USA. Available online: https://keep.lib.asu.edu/items/151792 (accessed on 24 June 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).