2. A Philological Study of Old Uyghur Buddhist Texts: Edition and Linguistic Investigation of the Abhidharmakośabhāṣya-ṭīkā Tattvārthā

Amongst the philological works published in the 21st century in Japan, M. Masahiro Shōgaito’s 庄垣内正弘 monograph,

Uigurubun Abidaruma ronsho no bunkengaku teki kenkyū ウイグル文アビダルマ論書の文献学的研究 [Old Uyghur Abhidharma texts: A Philological study], published in 2008 by Shohkado in Kyoto, is representative. It presents an improved edition of the London manuscript Or. 8212-75A, which is the most comprehensive Old Uyghur Buddhist commentary text,

Abhidharmakośabhāṣya-ṭīkā Tattvārthā. Additionally, it offers a comprehensive linguistic investigation of all known Old Uyghur Abhidharma texts, including the Old Uighur translations of Vasubandhu’s

Abhidharmakośabhāṣya and

Abhidharmakośakārikā, as well as Saṃghabhadra’s

Abhidharma-vatāra-śastra, which are of particular importance for the study of the Old Uyghur language and Central Asian Buddhism. Of these, the Old Uyghur translation of the

Abhidharmakośabhāṣya-ṭīkā Tattvārthā was first published by M. Shōgaito in a three-volume monograph between 1991 and 1993 (see

Shōgaito 1991–1993). To the best of my knowledge, two comprehensive reviews have been published after the publication of the book, one in Japanese (

Yoshida 2009) and one in German (

Yakup 2010); unfortunately, no review has been published in English. In the following lines, we will consult with both.

The edition of the Old Uyghur fragments of the

Abhidharmakośabhāṣya was pioneering until the publication of all Old Uyghur fragments of the texts preserved in the Hedin collection of the Museum of Ethnography in Stockholm in 2014 by M. Shōgaito in English. In recognition of this contribution to scholarship, M. Shōgaito was bestowed with the Japan Academy Prize in 2011, the most esteemed academic accolade in Japan. In reaching its decision to award him the prize, the Japan Academy offers the following conclusive remarks (translated from the text on the website of Japan Academy (

https://www.japan-acad.go.jp/pdf/youshi/101/shogaito.pdf, accessed on 15 April 2025):

“This book presents an edition and systematic analysis of the Abhidharmakośabhāṣya-ṭīkā Tattvārthā, the most voluminous text in Old Uyghur literature, which is considered the most difficult to understand, in the most accurate and ideal way. It represents a significant achievement that should be called a pyramid in the field of Old Uyghur language research in Japan, which was originally initiated by Tachibana Zuicho and Haneda Toru. The book is regarded as a landmark work in Japanese Uyghur language research and represents a peak achievement in this field of research. In light of the above, we conclude that Masahiro Shōgaito’s research merits the Japan Academy Prize.”

M. Shōgaito’s monograph is comprised of five sections. The first section, entitled ‘Studies of the Old Uyghur Tattvārthā and the other Abhidharma texts’ (pp. 1–134), is followed by the second section, the edition of two Abhidharma texts other than the Tattvārthā (pp. 135–163). The third section presents the edition of the London manuscript Or. 8212–75A of the Tattvārthā (pp. 165–465). The fourth section consists of an analytic list of words attested in all manuscripts of the Tattvārthā (pp. 467–745), and the fifth section includes a list of abbreviations and a bibliography (pp. 746–750).

In the opening part of the initial section (pp. 1–2), M. Shōgaito provides a comprehensive description of the Old Uyghur fragments of various Abhidharma texts, including those from well-known texts such as

Tattvārthā,

Abhidharmakośabhāṣya and

Abhidharmakośakārikā, along with other relevant commentary texts. An updated version of this part in English can be found in

Shōgaito (

2014, pp. 9–11).

The first part of this section begins with a detailed description of the London manuscript of the

Tattvārthā, followed by an analysis of two colophons to the London manuscript and the Old Uyghur names of the

Tattvārthā (pp. 6–10). In M. Shōgaito’s opinion, the two London manuscripts, like the three

Avadānas, which are known as the

‘Three Avadānas suitable to the Avalokeiteśvara-sūtra and the Āgama-sūtra’ (Or. 8212-75, for edition, see

Shōgaito (

1982;

1988, pp. 56–99), were very probably copied by the same scribe, namely Tükäl Tämür Tu Qya in the middle of the 14th century (p. 8). The evidence for the dating is the colophon itself, which reads:

Tükäl Tükäl Tämür Tu Qya čïzïndïm qoyn yïl onunč ay beš otuzqa saču balïqta, 善哉 ‘I Tükäl Tämür Tu Qya have written for myself, on the 25th of the tenth month of the sheep year, in the city of Shazhou, Sādhu!’. The name of the scribe is recorded as Tükäl Tämür on an empty page at the end of the manuscript as the owner of the manuscript:

Bu čaγši m(ä)n Tükäl Tämürningol tep bir käzigkiyä bitimiš boldum čïn ‘I have written once, stating that this volume is of mine, Tükäl Tämir. (This is) true’. Another long colophon with the quotation from the main text reads:

luu yïl ikinti ay beš yegirmikä män Tükäl Tämür bo nomï bitigäli tägindim yanu sadu bolzun ‘On the fifteenth day of the second month of the Dragon Year, I Tükäl Tämür have ventured to write this doctrine. It may be Sādhu!’ M. Shōgaito therefore assumes that the writing of the text took three years. Since the text comes from the same cave as the Old Uighur

Book of the Dead (for edition, see

Zieme and Kara 1978), which was written in the tenth year of Zhizheng 至正, i.e., 1350; the date of the London manuscript should be around that time (pp. 7–8). In the following pages (pp. 8–10), M. Shōgaito engages with the Old Uyghur title of the text, namely

abidarim šastrtaqï čïnkertü (tözlüg) yörüglärning kengürü ačdačï tikisi baštïnqï küün, which is also referred to as

abidarim qïïnlïγ košavarti šastrtaqï čïnkertü (tözlüg) yörüglärning kengürüsi baštïnqï tägzinč. Indeed, both render the preceding Chinese title

Apidamo jushelun shiyishu juan diyi 阿毘達磨倶舎論實義疏巻第一 which can be translated as ‘

Abhidharmakośabhāṣya-ṭīkā Tattvārthā, volume one’, or ‘Aśvaghosha’s Exegesis on the Dharmakośa: An Exposition on the First Tattvārthā, volume one’.

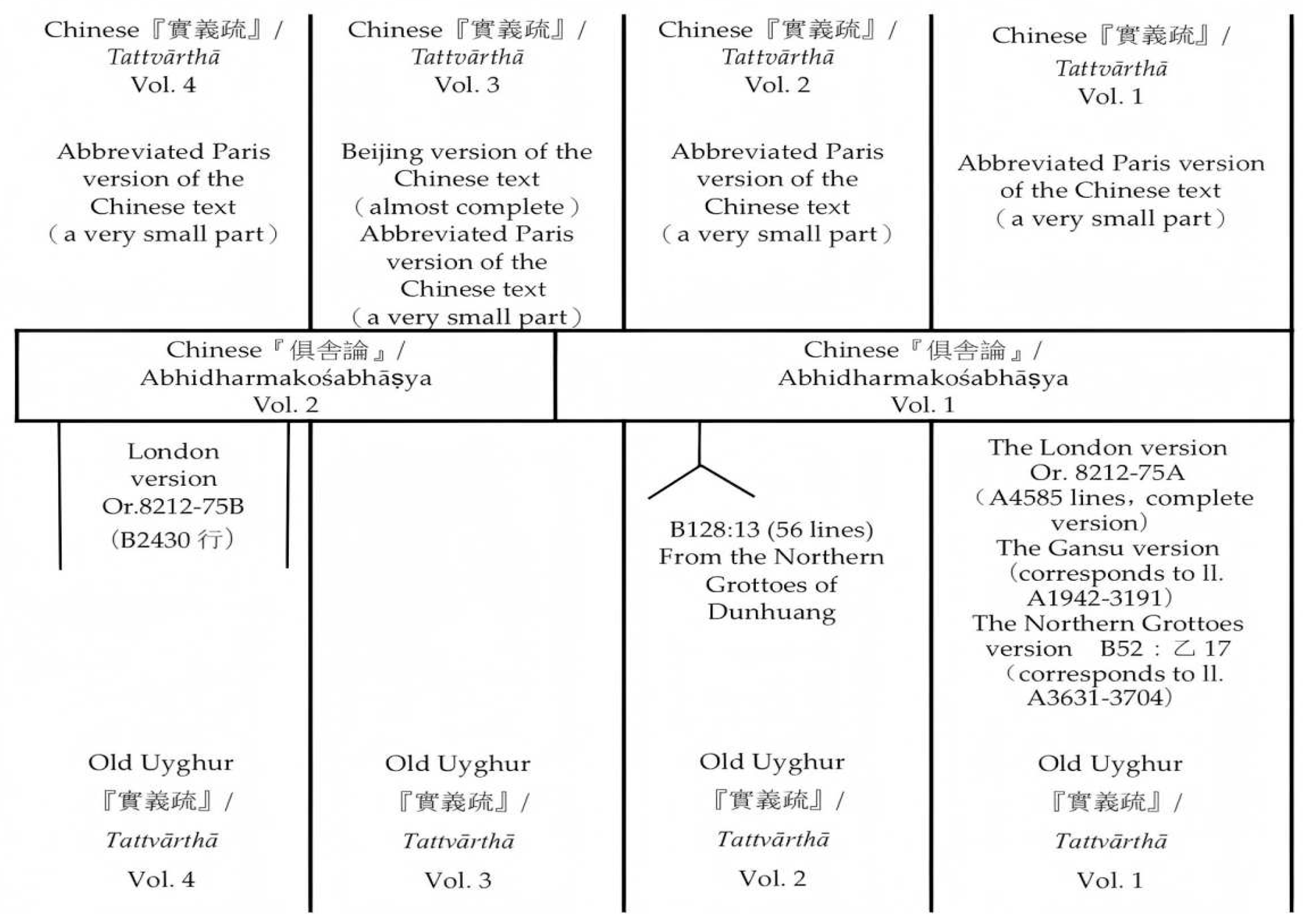

In the pages dedicated to the analysis of the content of the Tattvārthā (pp. 10–40), M. Shōgaito’s careful comparative analysis demonstrates clearly how the long quotations from the Abhidharmakośabhāṣya were divided into smaller units in the Tattvārthā and annotated step by step (pp. 11–12). However, due to the unavailability of the primary text of the Abhidharmakośabhāṣya, specifically the manuscript held in the Hedin collection at the Museum of Ethnography in Stockholm and edited by M. Shōgaito in 2014, he was unable to conduct a direct comparison with potential parallels in the Hedin manuscript of the Abhidharmakośabhāṣya. M. Shōgaito asserts that the quotations correspond to Xuanzang’s Chinese translation of the Tattvārthā, citing the Chinese characters that have been inserted into the Old Uyghur version of the Tattvārthā as evidence. These characters, which include the Apidamo shunzhengli lun阿毘達磨順正理論 (pp. 15–16), are part of the Old Uyghur text. The subsequent section will present a comparison of the Tattvārthā with its Tibetan and Mongolian versions (pp. 17–31). In this study, M. Shōgaito sets out to elucidate the characteristics of the Old Uyghur Tattvārthā. This undertaking is precipitated by the paucity of research on the Sanskrit version of the text at the time. The author’s approach is multifaceted, encompassing a thorough examination of the text’s structure, quotations from the Abhidharmakośabhāṣya, and the manner in which inquiries are addressed. In doing so, M. Shōgaito rightly rejects E. D. Ross’s view that the Old Uyghur Tattvārthā is a ‘super-commentary’, since the changes observed in the Old Uyghur are also found in the Tibetan and Mongolian versions of the text. In a substantial section, Shōgaito examines the relationship between the various manuscripts of the Old Uyghur Tattvārthā and the Chinese text, concluding that the discrepancies are negligible and that they all stem from a single text.

In the part devoted to the examination of corrections (pp. 40–48), M. Shōgaito provides a comprehensive illustration of typical methods for rectifying or offering alternative interpretations in the text, for example, by employing the Chinese character 又

you (again) in conjunction with the Old Uyghur expression

ymä ter (is also said), providing letters on the left side of words or phrases, corrections to the quotations. This is followed by an analysis of mistranslations and misspellings (pp. 48–50). Here he only mentions some translation mistakes at the sentence and word level. The subsequent part (pp. 50–86) presents an edition and comparative study of the fragment of the text preserved at Gansu Museum and two fragments from the Northern Mogao Grottoes of Dunhuang (B52乙: 17 and B128: 13), discovered by Chinese archaeologists between 1988 and 1995 (for a description of the Old Uyghur texts discovered in this excavation, see (

Yakup 2006)). Through a comparative analysis, M. Shōgaito has demonstrated that certain units that are identified as corrections in the London manuscript are not present in the fragment preserved in the Gansu Museum but rather constitute an integral part of the text (see also

Yakup 2010). He illustrates the relationship between the different manuscripts of the text in the following chart (

Figure 1):

The discussion of the orthographic, phonological, morphological, terminological and syntactic features of the Old Uyghur Tattvārthā is the central issue of the last part of the first section (pp. 87–134). In his remarks on orthography, M. Shōgaito mentions some characteristic peculiarities of the text, such as the special spelling of <‘>, unusual word breaks as seen in <p’q-šy> (baxšï ‘teacher’), the use of double dots to distinguish γ or q from a, ä, n, r, etc. (pp. 87–88). A very long discussion is devoted to illustrating the so-called d/t confusion (pp. 88–90). In the analysis of phonology, he focused on the illustration of insertion vowels between some connected consonants, as seen in asïra ‘below’ (from asra) and uturu ‘concerning’ (from utru). In the analysis of morphology, he focuses on the description of rare elements such as tüšüt ‘accustomed’ and yïd yuq ‘a behavioural tendency’, the analysis of rare morphological elements such as {-mtï} expressing diminutive, conjunctive u, and so on (pp. 90–95). In his analysis of Buddhist terms, M. Shōgaito identifies calques, global copies (from both Chinese and Sanskrit), and concludes the main types of each group and the ways in which they were copied from Chinese and Sanskrit into Old Uyghur (pp. 95–111). According to M. Shōgaito, the majority of Old Uyghur Buddhist terms attested in Old Uyghur Abhidharma texts are translations from Chinese, or calques. As examples, he mentions amtï yorïyu turur ‘running straight’ (translates Chin. 正行 zhengxing and corresponds to Skt. gacchat), atqaɣ atlɣ basutčï ‘auxiliary cause called object of consciousness’ (translates Chin. 所縁縁 suo yuanyuan and corresponds to the Skt. ālambana-pratyaya), közünür üd ‘seeing time’ (translates Chinese 現在世 xianzai shi ‘present’ and corresponds to the Skt. pratyutpanna), nïng vibakti (translates Chin. 属格 shuge ‘genitive case’ and corresponds to Skt. ṣaṣṭhī vibhakti), etc. (pp. 95–96). According to him, these terms faithfully represent the syntactic structure of Chinese terms, but they are correct in terms of Old Uyghur grammar.

A particularly important part of this section is the one in which the syntactic properties of

Tattvārthā are analyzed (pp. 112–122). The focus is on syntactic phenomena strongly influenced by Chinese, which M. Shōgaito calls Chinese-imitating syntax (擬漢構文), and which he has extensively researched in his book

Studies on Uighur Language and Literature I, published in 1982 (pp. 112–115). In this part, M. Shōgaito examines clauses that follow Chinese word order (pp. 112–116), characterizing them as those that have been constructed within the framework of Old Uyghur grammar, despite following Chinese word order. He then goes on to discuss certain modal constructions that have been overlooked in previous research. Recently, some of these modal constructions have been described in detail in

Yakup (

2022), using M. Shōgaito’s materials and analysis. In the last part of this section (pp. 123–134), the author explains the readings and functions of the Chinese characters that appear in the

Tattvārthā and other Abhidharma texts as part of the Old Uyghur text that M. Shōgaito believes were read in Uyghur, namely the

Kundoku 訓読 (Uyghur Reading of Chinese Characters). M. Shōgaito has written extensively on this subject in

Shōgaito (

1982, pp. 101–12;

2003,

2004), of which

Shōgaito (

2003) is the most representative and is now available in English translation (see

Shōgaito 2021).

The second section of the text presents an edition of fragments of two Old Uyghur Abhidharma texts, comprising some fragments. The first text comprises six fragments of a commentary on the

Abhidharma-avatāra-prakraṇa (Chin.

Ru Apidamo lun 入阿毘達磨論), which is preserved in the Serindia collection at St Petersburg, namely at the Institute of Oriental Manuscripts of Russian Academy of Sciences (pp. 135–154). The text has been reconstructed based on the Chinese text on the recto. M. Shōgaito’s meticulous examination of the fragments encompasses not only transliteration, transcription and a Japanese translation, but also a thorough comparison with the

Tattvārthā, with a particular focus on pivotal Buddhist terminology and distinctive expressions. Previously, three leaves of the text preserved in the Stockholm Ethnographic Museum (1935-21-23) and photographs of four leaves of the commentary on the

Abhidharma-avatāra-prakraṇa were published by K. Kudara in 1980. The second text consists of two fragments of a verse commentary of the

Abhidharmakośabhāṣya, and both are preserved in the Berlin Turfan collection (pp. 155–163). In addition to providing the transliteration, transcription and Japanese translation of the Berlin fragments of the text, M. Shōgaito presents the text in verse form, which is followed again by an analysis of some Buddhist terms. In recent years, some Old Uyghur Abhidharma texts have been published (

Kasai and Hirotoshi 2017). The texts contain Brāhmī elements that are inserted into the text as an integral part of it, just like the Chinese characters inserted into the

Tattvārthā and other Old Uyghur Buddhist texts, although their characteristics are somewhat different.

The third part of the studies is dedicated to the edition of the London manuscript Or. 8212-75A, which constitutes the core of the book and is of the utmost importance. In conjunction with the index, this section constitutes the most substantial portion of the monograph. It comprises the transcription of the complete London manuscript Or. 8212-75A of the

Tattvārthā, accompanied by its Japanese translation, along with a philological commentary on the text. He arranges the transcription and its Japanese equivalent on facing pages, while the commentaries are arranged as footnotes below the transcription and translation. The transcription is fundamentally consistent with the phonematic principle, as previously delineated on page 165, with the exception of the dental consonants

d and

t, which are rendered in accordance with the text’s spelling. A notable feature is the presentation of the numerous corrections in the original manuscript, which have been placed in angle brackets in the transcription. This feature distinguishes the edition from the typical publications of Old Uyghur texts, where corrections are typically reproduced in the form of footnotes. The translation does not always adhere to the sentence structure of the original Old Uyghur text, but it is presented in a form comprehensible to Buddhologists and scholars engaged in Central Asian philology (see

Yakup 2010). In the process of translating the quotations from the

Abhidharmakośabhāṣya, the author first presents the Old Uyghur text in the Japanese translation in bold font, followed by the quoted original Chinese text in round brackets. This offers readers a valuable opportunity to comprehend the Old Uyghur text accurately in comparison with the Chinese original and to discern the differences between the Uyghur text and the Chinese original (

Shōgaito 2008, pp. 173, 209, 227, 281). The inclusion of the Sanskrit equivalents of the most significant Buddhist terms and personal names, presented in round brackets directly after the Japanese translations, is undoubtedly beneficial to readers. The commentaries on the text and translation are mostly precise and avoid unnecessary quotations of explanations and examples from available publications, which are common in some publications. The commentaries present not only the spelling, etymology and meaning of the individual words and the differences between the various versions of the

Tattvārthā, but also analyze in detail the linguistic characteristics of the text, focusing on important phonological processes, specific Buddhist terms and phrases and interesting syntactic phenomena. Furthermore, the content-related and terminological relationship of the Old Uyghur text to the Chinese original is thoroughly discussed, and the textual relationship between the London manuscript and the other manuscripts of the

Tattvārthā is explained. This distinguishes the commentaries in this monograph from the concise endnotes of the edition of the same London manuscript published by the same author in 1991 and 1993.

A significant component of this monograph is the analytic index of words, which encompasses nearly 300 pages (pp. 467–745). As elucidated in the notes on the structure of the index (p. 467), the entries in the word list are presented in the phonemic transcription, while the examples of their usage are presented in a form closer to the original spelling. This approach facilitates a direct comparison between the phonemic interpretation of the entries and the variations present in the original manuscript. The index incorporates a substantial lexical database, encompassing not only the word material from the London manuscript Or. 8212-75A of the

Tattvārthā, which has been edited in this volume, but also the lexical content of the other London manuscript, Or. 8212-75B. The latter has already been published in 1993 as the second volume of (

Shōgaito 1991–1993). The index has been expanded to include the word material from the Stockholm manuscript of the Old Uyghur translation of the

Abhidharmakośabhāṣya (

Shōgaito 2014) and the Gansu and Dunhuang versions of the

Tattvārthā. This constitutes the first instance in which the comprehensive vocabulary of the significant Old Uyghur Abhidharma texts has been meticulously compiled and presented to the scholarly community in an optimal form. Each entry comprises not only the Old Uyghur form and its Japanese translation, but also the Chinese equivalents. The Chinese equivalents of the phrases and example sentences elucidating the usage of the entries have been meticulously catalogued. This is not a rudimentary word index, but rather a bilingual lexicon of Old Uyghur and Chinese. In conjunction with the analytical word list provided in

Shōgaito (

2014), it presents the more or less complete lexical material of the Old Uyghur Abhidharma texts and will always accompany scholars interested in the study of Abhidharma texts as well as those conducting research in the fields of Old Uyghur philology and Old Uyghur Buddhism.

A marked difference is evident between this monograph and the 1991–1996 edition previously referenced. Nevertheless, given the absence of facsimiles in the present volume, users are advised to refer to the third volume of the 1991–1996 edition, the facsimile of the London manuscript. Scholars can also benefit from the high-resolution photographs of the entire text on the International Dunhuang Project website.

It is evident that there are aspects of the transcription and translation that require refinement, and that some printing errors must be rectified. The majority of these have been highlighted in

Yoshida (

2009) and

Yakup (

2010). There are other minor errors to be mentioned. On p. 1, footnote 3, we find

Kudara (

1981), but this work was not listed in the bibliography; on p. 746,

näčuk must be a typing error for

näčük; some words that were listed under some entries can be listed as independent entries, e.g.,

örtüg-lüg ‘covered’ on p. 609 and

sïmlïγ ‘limited’ on p. 638. Nevertheless, this does not alter the fundamental reality that this monograph represents the most substantial and inspiring outcome of over three decades of unrelenting effort by a preeminent Japanese linguist and expert on Old Uyghur philology. The monograph demonstrates the comprehensive and meticulous research that can be conducted on an Old Uyghur text when approached from the perspectives of Old Uyghur philology, Sinology, Mongolian Studies and Buddhology, leveraging the systematic philological and linguistic expertise of the author.

3. New Investigation on the Historical Buddhist Inscription: Re-Examination of the Sino-Uyghur Bilingual Inscription on the Restoration of the Mañjuśrī Temple in Suzhou 肃州 in 1326

The Old Uyghur corpus of texts includes four inscriptions engraved in stone, which deal with a range of historical events. In addition to the so-called Tudum Šäli Inscription from Tuyoq, which is from the West Uyghur kingdom, the remaining three inscriptions date from the Yuan period. One such inscription is the Sino-Uyghur bilingual inscription on the restoration of the Mañjuśrī temple in Suzhou 肃州, engraved in 1326. The inscription was discovered in the Mañjuśrī Grottoes, i.e., Wenshu Shan Shiku 文殊山石窟, located on Jiayushan 嘉峪山 Mountain, which is situated 15 km to the southwest of Jiuquan 酒泉 City in Gansu Province, People’s Republic of China. It is currently housed in the Ethnic Museum of the Sunan Yugu Autonomous County 肃南裕固族自治县. The inscription indicates that the monument was erected to commemorate the restoration of the Mañjuśrī Temple in the Wenshu Mountain Grottoes in Suzhou by Nom Taš in the 3rd year of the Taiding 泰定 Period (1326). The inscription comprises 26 lines of text in both Chinese and Old Uyghur. It is 1.24 meters in height, 0.74 meters in width and 0.25 meters in thickness. The Japanese historian Kentarō Nakamura 中村健太郎’s extensive paper, ‘Re-examination of the Uighur version Mañjuśrī Temple in 1326’ (

Nakamura 2023), is dedicated to the philological and historical investigation of the inscription.

As K. Nakamura writes in the introduction to the paper, the inscription was first introduced to the scholarly community by the eminent French Orientalist Paul Pelliot (1878–1945). Although he did not offer an interpretation of the Old Uyghur inscription, he made several references to the presence of an Old Uyghur text, in addition to the Chinese inscription. Subsequent to this, Zhang Wei 張維 incorporated the Chinese component of the inscription into

Longyou jinshi lu 隴右金石錄 (

W. Zhang 1982), albeit erroneously identifying the text on the reverse as Mongolian. It is noteworthy that among the results of historiographical research on the inscription, the work of the Japanese historian Masaaki Sugiyama 杉山正明 (

Sugiyama 2004, pp. 242–370) merits particular attention. Utilizing Chinese and Persian historical sources from the same period as the inscription, he conducted an investigation into the origin of the royal family of the Eastern Chaghatai. His findings demonstrated that Čübaī 出伯, the son of Algū 阿鲁浑, had departed Central Asia. He subsequently joined Kublai’s banner and was granted a fief in the Hexi 河西 region. During the first half of the 14th century, he became the leader of the Chaghatai tribes in the aforementioned region. He was succeeded by his grandson, Nomtash 诺姆塔什, who was also closely related to the Qomul/Hami royal family of the Ming dynasty that was formed later. Sugiyama’s study, although limited to the Chinese side of the inscription, had a significant impact on the study of Mongolian history after that date. In 1986, the Chinese scholars Geng Shimin 耿世民and Zhang Baoxi 張宝璽 first provided an interpretation of the Old Uyghur side of the inscription (henceforth referred to as the ‘first translation’) (

Geng and Zhang 1986). This text was subsequently included by Zhang Teishan 張鐵山 without significant alteration (see

T. Zhang 2015, pp. 137–42).

The paper by Nakamura comprises three sections, in addition to an introduction (pp. 68–69) and a final remark (pp. 102–103). The initial section presents an interpretation and translation of the Old Uyghur inscription (pp. 69–74), followed by notes to some words and expressions (pp. 74–92). The subsequent section offers a philological analysis of the inscription, accompanied by an initial historical examination of the text (pp. 92–101). The concluding section provides a translation and commentary on the Chinese side of the inscription (pp. 101–102).

The first section of the paper serves as the foundation and key reference point for this study. In this section, Nakamura provides a transcription and translation of the inscription, accompanied by over 90 annotations on the words and phrases in the inscription (pp. 69–92). These annotations revise and supplement the transcriptions and interpretations in the ‘first translation’, greatly improving the accuracy and reliability of the document. The annotations are divided into the following four types:

(1) Corrections to the transcription of the ‘first translation’. For example, 6f (p. 79) is read as

padma aγïrlïγ in the ‘first translation’. Nakamura argues that the <r> in

aγïrlïγ does not exist in the inscription, so he suggests that the phrase should be read as

padma aγïlïq. The word

aγïlïq not only means ‘treasure’ but is also the Old Uighur translation of the Sanskrit word

garbha. For this reason, Nakamura interprets

padma aγïlïq as ‘the world of the lotus flower collection’ (=Skt. padma-garbha-loka-dhātu), as it appears in the Chinese translation of the Buddhist texts. In Old Uyghur, there is another expression with the same meaning,

lenxua aγïlïqï (

Wilkens 2021, p. 452). Judging from this,

padma aγïlïq is possible;

padma aγïlïqï is desirable. The other example is the transcription of

cwnklwq discussed in 21 h (p. 88). It is transcribed as

čongluγ in the ‘first translation’ and is taken to be a phonetic translation of the Chinese 钟楼 ‘bell tower’. In his study of the Chinese loanwords in the

Xuanzang Biography, M. Shōgaito rejects the interpretation in the ‘first translation’, pointing out that the word 楼

lou is transliterated as L’W in the Old Uyghur language, and

luγ cannot be considered a transcription of 楼; it is an adjective ending attached to

čong. K. Nakamura confirms M. Shōgaito’s view that

-luγ is not a phonetic translation of 楼

lou, but he does not agree with M. Shōgaito’s transcription

čongluγ bi taš and his interpretation of it as ‘the inscription with a bell tower’. K. Nakamura, on the basis of the phrase 钟楼碑楼 in the Chinese side of the inscription, postulates that there should be two buildings called 钟楼

zhonglou and 碑楼

bilou. Consequently, it is not reasonable to consider

čongluγ as a modifier of

bi taš, since there are two buildings or towers, namely the ‘bell tower’ and the ‘stele tower’. Consequently, K. Nakamura transcribes

-luγ as

-luq, which, according to the explanation, all forms derived with this ending have in common the relational element ‘purpose, designation’ or, if one prefers, the sememe ‘for’ (

Nakamura 2023, p. 88). Thus, he transcribes the phrase as

čongluq bi taš and interprets

čongluq as ‘a place for the bell,’ or ‘a bell tower.’ However, the question here is whether the Old Uyghur word ‘čong’ can take the suffix ‘-lXk’. Note that there is no attestation of a Chinese word taking this suffix. The function of the suffix basically does not allow such a derivation. On the other hand, it cannot be completely excluded that the Old Uyghur scribe understood 钟楼 and 碑楼 as a bell tower, rather than two separate towers, as K. Nakamura understands.

(2) A revised interpretation of certain words in the ‘first translation’. The word

čoγsïramaq-sïz in 7c (p. 79) was previously interpreted in the ‘first translation’ as ‘very much’ according to the context. However, upon consulting the Russian translation of the word in the

DTS (

Nadeljajev et al. 1969, where it is rendered as неме́ркнущий (=to shine with undying light)), Nakamura posits that the original meaning of

čoγsïramaq-sïz is ‘not to let

čoγ (=light) disappear’. On the basis of this, Nakamura believes that there is no need to deviate from the original meaning and that the word should be translated as 永遠に輝く, which might be rendered as ‘to shine forever’.

(3) The transcription and explanations of selected words in the ‘first translation’ have undergone comprehensive correction. The word qabčïγay in 13c (p. 82) was transcribed as qapučuγay in the ‘first translation’ and was explained as ‘“analyzed from the etymology of Old Uyghur, it must be derived from qap ‘sack’ by adding the diminutive suffix -čuq, and then -ay, and the word means ‘small sack’”. Nakamura, however, has restored the word as X’PČYX’Y and transcribed it as qabčïγay. It is noted that the qabčïγay in the Old Uyghur inscription is derived from the Mongolian word qabčiγai, which denotes a ‘ravine; cliff’. The place name Jiagushan 嘉谷山 that occurs in the Chinese part of the inscription was called in Mongolian Kägü qabčiγai. The assumption is made that this name would have been recognized and utilized in Suzhou 肃州 and neighboring regions, including by the members of the Chagatai family and the Old Uyghur Buddhist community.

(4) Addition of readings of words that were not deciphered in the ‘first translation’. The word which was commented on in 5i (p. 78) was not deciphered in the ‘first translation’. Nakamura restored it as Č’R’MP’βYKY and transcribed it as čarambavike, identifying it as the copy of Skt. caramabhavika which came into Old Uyghur via the intermediary of Tocharian B caramabhhavike. As Nakamura elucidates, caramabhavika is a reference to the ‘final body’, more specifically the final body of the bodhisattva, as well as the ‘final body’ taken in the world of saṃsāra, which is understood to refer to the body of an arhat 阿羅漢, who has extinguished all afflictions and will not be reborn (Skt. antima-deha, antima-sarīra). In a similar vein, it can be used more loosely to refer to the final body of a Buddha, or an enlightened sage such as a ‘pratyekabuddha or bodhisattva’ (DDB, entry 最後身, accessed on 10 September 2024). In this instance, Nakamura aligns with P. Pelliot’s prior assessment and identification.

The second section of the paper provides a more detailed examination and analysis of the inscription, drawing on the notes from the first chapter and offering a number of significant arguments. The subsequent analysis is divided into two distinct aspects: philology and historiography, with the aim of introducing the respective viewpoints.

With regard to the orthographic characteristics of the inscription, Nakamura concurs with the summary and generalization of the ‘first translation’ concerning these characteristics, with the exception of the two points in the photographs that can distinguish the letters q and γ. He asserts that further examination of the original inscription is required (p. 93).

Nakamura’s endorsement is given to the finding in the ‘first translation’ that the inscription was written in the form of a poem in alliteration. However, he suggests that, on the basis of the fact that the alliteration quatrains in the inscription begin with the phrase kim ol in line 5, and not in line 6, as the ‘first translation’ suggests. The ‘first translation’ highlights the presence of two dots (:) and four dots (⁘) in the text, yet no explanation is provided for their relationship to the poem. Nakamura reasonably elucidates these as a characteristic of alliterative quatrains in Old Uyghur literature, which are typically comprised of four stanzas, with two dots (:) at the conclusion of each line and four dots (⁘) at the culmination of each stanza (pp. 93–94). This is the prevailing paradigm for the poems ascertained in the Old Uyghur prints and a substantial number of manuscripts. Nevertheless, it should be noted that there are a number of exceptions to this generalization. The topic deserves careful study.

In this section, Nakamura addresses the more contentious issue of the provenance of the alliterative verse. The ‘first translation’ has indicated that the alliteration represents the earliest manifestation of Old Uyghur poetry. The alliterative verse form was utilized in certain Manichaean poems, and it gained popularity during the Yuan period. However, some scholars have suggested that the alliterative verse was introduced into Old Uyghur culture from Mongolian during the Yuan dynasty (

Doerfer 1996, p. 123). Nakamura’s earlier research (

Nakamura 2007, pp. 84–96) had already indicated the presence of alliterative verse not only in Manichean texts but also in Early Buddhist texts from the West Uyghur Kingdom. Subsequent research by T. Moriyasu (

Moriyasu 2015, pp. 522–23) has identified alliterative verse in the colophon of the Qomul (Hami) version of the

Maitirisimit, dated to 1067, and several instances of this style in the earlier Sängim version of the

Maitirisimit. These findings serve to reinforce the conclusion that alliteration constitutes a distinctive poetic style of the Old Uyghurs. However, Nakamura does not consult subsequent discussions on this topic in

Zieme (

1991, pp. 292–93),

Laut (

2002),

Yakup (

2015) and

Wilkens (

2016b). Indeed, the findings in

Wilkens (

2016b, pp. 134–35) are very important. In this work, J. Wilkens reconstructs several alliterative verses from the introduction and other chapters of the Buddhist story collection

Daśakarmapathāvadāna-mālā (Garland of Legends Pertaining to the Ten Courses of Action, henceforth DKPAM); below, we quote only two stanzas:

ayuvipaklıg Y Y NY tokun köni kertü yašıklıg

altı y(e)g(i)rmi taŋda

azk(ı)ya öŋtün örläp agıp yoklayu körüšü turur

amrakı t(ä)rkän kunčuy t(ä)ŋrim kutılıg

ay t(ä)ŋri tilgäni birlä birgärü birikip

öŋlüg mäŋizlig tavarlar üzä ukıtgul[u]k:

ulug küč[lü]g: üč törlüg öčmäk tözlärintin:

üč üdlärtä iš išlämäkig körüp

ülgüsüz üküš törlüg adrokların örtämiš.

The first is from the introduction and the second is from the Tömürti version of the DKPAM. As we can see, they not only show alliteration at the beginning of lines, but also between words in some lines (all marked in bold as in

Wilkens (

2016b). Note that

Laut (

2002) has discussed the similar types of verses of the Qomul (Hami) version of the

Maitrisimit that

Wilkens (

2016b, p. 135) mentions. Nevertheless, this clearly shows that alliteration existed in the early period of Old Uyghur Buddhism, as both the

Maitrisimit and the DKPAM are representative texts of Early Uyghur Buddhism.

Nakamura’s discussion encompasses the parallels observed between the inscription and the Old Uyghur colophon U345 to a printed text. As J. Wilkens noted (

Wilkens 2016a, p. 246), the Old Uyghur section of the inscription and the printed colophon manifest analogous characteristics in all respects, including structure, vocabulary and expression. This assertion is corroborated by numerous examples. Subsequently, Nakamura proceeds to offer his own insights into the reasons for the prevalence of these similarities, proposing that the Old Uyghur Buddhists in the Hexi region, who were responsible for the erection of the Mañjuśrī Temple Inscription, and the Old Uyghur Buddhists under the Yuan dynasty, were in close contact with each other. This proximity, it is argued, enabled them to readily access a significant number of Buddhist concepts that were shared by both groups. This topic is of significant importance and necessitates further research in order to achieve a more comprehensive understanding.

Nakamura’s examination of the honorific expressions reveals that both the Chinese side and the Old Uyghur side of the inscription partially, though not completely, adhere to the Yuan tradition. In the Chinese side, when addressing the kings of the Yuan, including Genghis Khan, the Great Khan, and the Holy King of the Wheel of Fortune, they are all written with two characters on their heads (the head of the line is raised by two characters compared to the previous line). However, when addressing the Chagatai khans of all generations, they are all written in the form of one character on their heads. However, there are instances of inconsistency in expression, for example, Mangkhuli is written in a flat manner in the 11th line, but in the 18th line, it is written in the form of one character head. Furthermore, instances of respect are expressed through the utilization of a space preceding the address, eschewing the head-up or flat form. In the Old Uyghur text, the address to express respect is fundamentally written in a flat form, without using the head-up form. A more detailed analysis reveals that, with the exception of Genghis Khan and the Great Yuan Khan, all other khans, including the Chaghatai Khan, are written in the flat form. However, when addressing the Chaghatai Khan specifically, the flat form is not employed for every khan. Nevertheless, the Sino-Uyghur inscription employs the Great Yuan Khan to the Chaghatai Khan above to express respect. According to Nakamura, this is because Nom Taš, the donor of the inscription, has taken his ancestor, the Great Kaghan of the Kubilay family, into consideration (p. 97).

When Nakamura examines the inscriptions from a historical perspective (pp. 97–101), his primary focus is on the rationale behind the utilization of Old Uyghur language for the back side of the inscription, as opposed to other scripts, such as Mongolian. This view is analogous to the argument posited by the ‘first translation’ and

Moriyasu (

2015), who contend that Old Uyghurs inhabited diverse regions of the Hexi area from the early to mid-14th century. They further posit that Old Uyghur emerged as an official language of the region, thereby rendering the utilization of Old Uyghur on the back side of the inscription a logical consequence. However, in this period, that is, in 1362, in order to highlight the glory of the Old Uyghur Hindu (Chin. Xindu 忻都) and his family, the

Dayuan chici Xinjingwang bei 大元敕赐西寕王碑 ‘Great Yuan Royal Edicts of the Xining Wang Stele’ was written in the Sino-Mongolian bilingual. Yongchang 永昌 served as the base of the Gaochang 高昌 royal Idiqut family when they fled from the eastern part of the Tianshan Mountains to the Hexi region. Nakamura’s argument is that factors other than population ratio were determining factors in the choice of language other than Chinese for the composite tablet during this period.

To substantiate this claim, Nakamura’s analysis is based on Professor Dai Matsui 松井太’s study of B163:42 (

Matsui 2008a,

2008b), a Mongolian document unearthed in the Northern Grottoes of Dunhuang. This document shows that after the 14th century, both the Chaghatai Ulus and the Eastern Chaghatai in the Hexi region were in close contact and practiced Tibetan Buddhism. Under their patronage and support, a vast area of religious and economic activity developed for the Old Uyghur Buddhist transmitters from the Eastern Tianshan Mountains to the Hexi region and into northern China. This Buddhist tradition had existed for a considerable period of time. Accordingly, Nakamura revisits line 15 of the inscription, which describes how Nom Taš’s accession to the throne prompted him to undertake a major renovation of the Mañjuśrī Temple after being informed of the ‘great merit of repairing the dilapidated monastery’. According to him, it was the Old Uyghurs who advised him to use the Old Uyghur script on the back of the inscription. This is why, as the ‘first translation’ and T. Moriyasu suggest, the Old Uyghur script was chosen for the back of the inscription. However, the following issue was not addressed in this discourse: the linguistic knowledge of Nom Taš and his personal attitude towards the use of the Old Uyghur language.

In the following examination, Nakamura analyses the impact of Tibetan Buddhist ideology on the East Chaghatay family during the Yuan dynasty. This analysis is conducted in three distinct subsections. In the initial subsection, Nakamura delves into the Tibetan perspective on kingship, exploring how the notion of kingship was interpreted through a Buddhist lens. Utilizing Tibetan Buddhism, the Yuan dynasty successfully achieved its objective of fortifying and legitimizing royal authority by integrating the royal family into the historical narrative of Buddhism. Nakamura’s analysis is further enriched by the use of the term č(a)kravrt qan uγuš-luγ (belonging to the clan of the wheel-turning saint king) in line 5 of the inscription, and the praise of Nom Taš as altun tilgän-lig qan (khan with a golden wheel) in line 15. He suggests that the Eastern Chaghatai clan, following the example of the Yuan dynasty, adopted the view and image of kingship based on Tibetan Buddhism as a way of maintaining royal power. In the second subsection, Nakamura explores the reasons for the reconstruction of Mañjuśrī Temple. Based on lines 12–20 of the inscription, Nakamura first suggests that the dilapidated Mañjuśrī Temple was probably rebuilt to commemorate Nom Taš’s accession to the throne. According to Nakamura, if this assumption is correct, then a grandiose reconstruction such as that depicted in line 21 could have visually created a festive atmosphere to celebrate Nom Taš’s accession and served to imbue the area with a Buddhist atmosphere. In the third subsection of his analysis, Nakamura builds on this by discussing the possibility that Mañjuśrī Temple was rebuilt as a Tibetan Buddhist monastery. In this passage, Nakamura discusses the word bumba, which has been erroneously interpreted as bimba (< Skt. bimba) in the ‘first translation’. The word bumba goes back to Tibetan bum-pa, signifying ‘precious vase’. This finding is of significant importance in analyzing the rationale and objective behind the reconstruction of the monastery. The ‘precious vase’, an indispensable Dharma vessel enshrined in Tibetan Buddhist monasteries, is of particular significance in this context. The presence of this vase suggests that, following the reconstruction of Mañjuśrī Temple, it was utilized for the performance of Tibetan Buddhist rituals at the site. This ceremony, held before the beam’s erection, is believed to have been performed to pray for the longevity of the Great Khan of the Yuan Dynasty and his clan. Although there is an absence of contemporary historical material to substantiate this hypothesis, Nakamura hypothesizes that, Nom Taš must have rebuilt Mañjuśrī Temple as a Tibetan Buddhist temple as a religious facility to pray for the longevity of the Great Khan, as East Chaghatai adopted the Yuan Dynasty’s perspective on kingship, which was informed by Tibetan Buddhist ideology.

Following a detailed examination of the reasons for the reconstruction of Mañjuśrī Temple, Nakamura ascertains that Mañjuśrī Temple was originally intended as a place of worship for the purpose of praying for the longevity of the Yuan dynasty khan and his clan. This conclusion is based on the Old Uyghur part of the inscription, i.e., lines 4 and 22, which is absent in the Chinese side of the inscription. In particular, line 4 proves that Mañjuśrī Temple was a religious facility for ‘His Highness the Great Khan, the Empress and the Crown Prince and his clan’. From line 22, it is stated that the monks were given land ‘for the longevity of His Highness, the Great Khan, and for the giving of lamps and joss sticks’. This suggests that the East Chagatai family of the Hexi region, as one of the kings who constituted the Yuan dynasty, would permit the monks residing in the Mañjuśrī Temple to conduct Buddhist ceremonies to pray for the longevity of the Great Khan of the Kublai clan. This finding lends further credence to the hypothesis that the Mañjuśrī Temple functioned as a Buddhist monastery, where the aforementioned ceremonies were held. From the point of view of the history of the Mongol period, the discovery of this in the Old Uighur part of the inscription is of great significance.

The third section of the paper presents a reconstruction of the Chinese side of the inscription, accompanied by a commentary. The transcription of the text was conducted on the basis of topographies provided by Jinghua 菁華 and P. Pelliot, in addition to Zhang Wei 張維’s Longyou jinshi lu 隴右金石錄. Subsequent to this, Nakamura appended eleven notes, some of which address the revision of Chinese character radicals in the ‘first translation’. For instance, the character 總 in the ‘first translation’ is actually 摠. Additionally, there are corrections to the misreading of Chinese characters in the ‘first translation’, for example, the character restored as 伯 in the ‘first translation’ should actually be 罷. Additions have been made to parts of the ‘first translation’ that were not restored, for example, 叉合歹金位後倶昇天矣喃荅失 太子見登’, and so on.

The inscription under scrutiny, as per the examination conducted by K. Nakamura, holds significance in enhancing our comprehension of the religious status of the Hexi region during the initial phase of the Yuan dynasty. Moreover, it serves as a pivotal source for the study of Late Old Uyghur. Notably, the first-person optative formed by means of –{-(A)lI} is unique to the text, as evidenced by examples such as bol-alï (lets become) and yasa-lï (lets restore) in 18–19. The words bumba and qabčïγay are also known from this text. In conclusion, K. Nakamura’s paper has made a significant contribution to the study of this text, illustrating many important historical facts related to it. However, it should be noted that the reconstruction of the text still deserves progress, and certain readings, for instance, kälülärüp in 20, remain enigmatic. The final interpretation of cwnklwq remains to be concluded.

It is important to note that this is not the only Old Uyghur inscription from the region that has been the subject of investigation by Japanese scholars. The Yulin 榆林inscriptions, first brought to wider attention by the publication of Professors James Russel Hamilton and Niu Ruji in 1998 (

Hamilton and Ruji 1998), have been the subject of further investigation by D. Matsui in 2008 (

Matsui 2008b). D. Matsui has rectified numerous misconceptions in earlier research and proffered his solutions, drawing on notes he took during his visit to the Yulin Caves 榆林窟. The Wenshushan 文殊山 inscriptions, previously published by Chinese scholars, have undergone a re-investigation by

K. Kitsudō (

2024). He rectified certain misconceptions that had arisen as a consequence of his observations during his visit to the Wenshu-shan Caves 文殊山石窟 in 2023. D. Matsui’s paper is written in English, while K. Kitshudō’s paper unfortunately became known to me after the deadline for submission of this paper.

The Corpus of Multilingual Inscriptions from the Dunhuang Caves, edited by D. Matsui and Sh. Arakawa (

Matsui and Arakawa 2017), is a monumental undertaking. Undoubtedly, a thorough investigation of all these inscriptions, encompassing the inscriptions in other scripts and languages unearthed in the region, has the potential to illuminate numerous significant questions concerning the language, religion, history and culture of the Hexi 河西 region.

4. Influence of the Old Uyghur Buddhism on the Mongolian Buddhism: The Transition from Buddhist Scriptures in the Old Uyghur Language to Mongolian Buddhist Scriptures

It is a widely accepted view that Mongolian Buddhism and the Mongol language was heavily influenced by the Old Uyghur Buddhism and Old Uyghur literary language in the early stages of its formation (

Shōgaito 2003a). A seminal paper on this topic is ‘Uigur contribution to the Early Buddhist Mongolian texts’, published by K. Nakamura (

Nakamura 2007). In this study, K. Nakamura employs a historical perspective by integrating these scriptures with relevant documents from the same period. The central themes explored in this study include the contributions of Old Uyghur individuals to the development of Mongolian Buddhism, the role of Old Uyghurs in shaping Mongolian Buddhism, and the influence of Old Uyghurs on the formation of Mongolian Buddhism. The analysis goes beyond the utilization of Buddhist terminology, delving into the role of the Old Uyghurs in shaping Mongolian Buddhism. This study demonstrates that the ‘Old Uyghur Buddhism’ that emerged in the West Uyghur Kingdom has laid a solid foundation for the development of Mongolian Buddhism (pp. 71–72).

With the exception of the introduction, final remarks and bibliography, Nakamura’s paper is divided into two sections. The initial section pertains to the translation and publication of Chinese–Old Uyghur Buddhist scriptures at the inception of Kublai’s era (pp. 72–83). The second section of the paper pertains to the argument that the alliterative quatrains were introduced into Mongolian from Old Uyghur literature (pp. 84–109).

In the first section, Nakamura’s primary focus is on two historical sources written at the time of Kublai’s accession to the throne, i.e., the establishment of the Yuan dynasty. At that time, in parallel with the establishment of new political order, Kublai organized the translation and publication of a large number of Buddhist scriptures which have been mainly carried out by Old Uyghur officials, particularly by Antsang 安藏, *Qïtay ~ Qatay Šäli 合台萨哩, Karunadas 迦鲁纳答思and Tanyasin 弹压孙. However, there is no consensus among scholars regarding the language to which the 畏吾字 and 畏兀兒文字 mentioned in the documents refer. 小林

Kobayashi (

1954) hypothesizes that the word 畏吾字 refers to the Mongolian language, while

G. Kara (

1981, p. 233) and

T. Moriyasu (

1983, p. 223) posit that it refers to the Old Uyghur language. Herbert Franke (

Franke 1994, p. 59), conversely, suggests that 畏兀兒文字, in this context, refers to the Old Uyghur language.

Nakamura’s argument posits that the question pertains to the existence of Buddhist scriptures in the Mongolian language during the period of Kublai’s accession, marking the inception of the Yuan dynasty. The earliest known translator of Buddhist scriptures into Mongolian is Cosgi Odsir (tib. Chos-kyi ’od-zer), but he does not belong to this period, being a monk belonging to the 14th century. Consequently, Nakamura meticulously examined the Buddhist scriptures translated by the four renowned Old Uyghur translators of Buddhist scriptures, namely, Antsang 安藏, *Qïtay ~ Qatay Šäli 合台萨哩, Karunadas 迦鲁纳答思 and Tanyasin 弹压孙. This analysis revealed that both Chinese and Tibetan scriptures were translated into Old Uyghur, and there was an absence of any evidence of 13th-century Mongolian scriptures in other historical sources from the same period.

Nakamura’s conclusion is consistent with that of Franke’s study of the Buddhist scripture, which was produced at the Daxingjiaoji Temple 大都大興教寺 in Dadu 大都 between Zhiyuan 至元 22 (1285) and Zhiyuan 至元 24 (1287). Specifically, the Buddhist scriptures in Mongolian were not yet extant in the thirteenth century. In contrast, W. Heissig hypothesizes that the Mongolian translation of the Sheng jiudu fomu ershiyi zhong lichen jing 聖救度佛母廿一種禮讃經 ‘Twenty-One Praises of Tārā’ (Skt. Tāre Ekaviṃśatistotra) printed in 1431 was translated from the Tibetan by Antsang 安藏. If this inference is valid, it would mean that the Mongolian translation of the text already existed in the second half of the 13th century. However, Nakamura rejects Heissig’s conjecture for the following reasons. Firstly, while the possibility that the text dates back to the first half of the 14th century cannot be denied, there is no basis for proving that Antsang 安藏 had translated it into Mongolian in the second half of the 13th century. Secondly, there is also doubt as to whether Antsang 安藏 was capable of translating the Tibetan scriptures into the Old Uyghur or Mongolian languages. On the one hand, H. Franke (as mentioned above) suggests that the Mongolian sūtras appeared after the 14th century, while on the other hand, Heissig’s view is inconsistent with Franke’s argument. To summarize, according to the existing historical data, Nakamura still thinks that the Buddhist scriptures in Mongolian did not exist in Kublai’s period. Following a thorough examination, Nakamura concluded that the scriptures translated by the Uyghur officials at the inception of Kublai’s reign, marking the establishment of the Yuan Dynasty, were in the Old Uyghur language, and that the likelihood of Old Uyghur language and script being utilized was deemed to be highly probable.

Nakamura’s research contributes to our understanding of the reasons why the Mongol rulers did not employ translators to translate the Buddhist scriptures into Mongolian in the 13th century, opting instead to use Old Uyghur. The West Uyghur kingdom underwent a conversion from Manichaeism to Buddhism after the 10th century, and due to their geographical location, they established a distinctive Buddhist cultural region where Eastern and Western elements coalesced. The Old Uyghur language underwent a transformation, evolving into a medium capable of articulating the sophisticated tenets and conceptualizations of Buddhism, as evidenced by its rich vocabulary, which incorporates numerous Buddhist loanwords from languages such as Tocharian, Sogdian, and Chinese. It is highly probable that the lingua franca of the eastern regions of the Mongol Empire during that period was also Old Uyghur. Consequently, it would have been a logical decision to translate Buddhist texts into Old Uyghur rather than into Mongolian, which has no Buddhist tradition. Nakamura also hypothesizes that the language of the Buddhist scriptures used at court was not Mongolian, but Old Uyghur.

According to Nakamura, Kublai’s aim in translating the Tibetan and Sanskrit scriptures and the writings of Pag’spa into the Old Uyghur language, and publishing and distributing them in large quantities, was to plant the idea of Tibetan Buddhism deeply in the minds of the people, to immerse the whole country in a Buddhist atmosphere, and thus to achieve the goal of consolidating royal power. Nakamura further contends that the translation of Buddhist scriptures from Tibetan into Old Uyghur language, as well as the printing of Old Uyghur Buddhist scriptures, commenced during the Kublai period. Conventional wisdom has hitherto held that the translation of Buddhist scriptures from Tibetan into the Old Uyghur language occurred during the Mongol period, i.e., from the 13th to 14th centuries. However, Nakamura, based on the aforementioned historical perspective, contends that this is highly improbable. The appearance of Old Uyghur Buddhist scriptures in the original Tibetan language was in the first half of the 13th century, and the translation of these texts was completed in the second half of the 13th century and continued until the middle of the 14th century.

Alliterative verse is a common feature of Buddhist literature from the Old Uyghur period, with the majority of surviving documents of this nature being Buddhist texts written in cursive or block prints. This is the major objection of the second section of Nakamura’s paper (pp. 92–109). A significant proportion of alliterative verses originate from the period of Mongol rule. Two predominant perspectives emerge concerning the genesis of dating. The first perspective, advanced by

Doerfer (

1996), posits that the practice of alliterative verse was adopted into the Old Uyghur language from the Mongolian language during the Mongol rule. Conversely, P. Zieme’s viewpoint asserts that the tradition of alliterative poetry emerged during the period of the Western Uyghur Kingdom and persisted until the Mongol rule (

Zieme 1991, p. 23). Nakamura’s position aligns with that of P. Zieme; however, to date, no Buddhist texts in alliterative verse from the pre-Mongolian period have been identified.

Utilizing the following four indicators as criteria for dating (see

Table 1), Nakamura screened all Buddhist texts in the alliterative form published to date, and from these, he selected two texts whose dating can be traced back to before the period of Mongol rule, namely (1) U 3269 (TIIIM 168.500) and (2) Mainz 219 (TIIIM 186.500).

Following a preliminary examination of the documents according to their form, Nakamura proceeded to analyze them from the perspective of their content. This analysis revealed that the recto of Text (1) is in prose, and its content is basically similar to that of the Chinese translation of the

Fumu Enzhong jing 父母恩重經 (Parental Benevolence Sūtra). Moriyasu’s research indicates that during the 10th century, Old Uyghur Buddhism was more influenced by Dunhuang Buddhism than by Tocharian Buddhism. This perspective suggests that the

Fumu Enzhong jing 父母恩重經 was imported from Dunhuang to the West Uyghur Kingdom and translated into the Old Uyghur language. The verso of Text (1) displays alliteration, a feature not reflected in the Chinese translation of the

Fumu Enzhong jing 父母恩重經. P. Zieme proposes that the rhyming section of the text was independently created by the Old Uyghurs of the West Uyghur Kingdom and incorporated into the prose section, ultimately forming a unified text (

Zieme 1985, pp. 69–70). Nakamura argues that the alliterative verses in Text (1), comprising a variable number of lines ranging from two to six, did not undergo standardization into a four-line stanza. The remaining characteristics of these verses are found to align with those observed in the alliterative verses of the Mongol period. Conversely, Text (2) deviates from Text (1) due to its incorporation of an alliterative quatrain, a structural element that mirrors the alliterative quatrains characteristic of the Mongol period.

A thorough examination of the extant evidence indicates that Nakamura’s assertion concerning the existence of Buddhist scriptures in the alliterative verse form prior to the Mongol period is substantiated. Moreover, Text (1) comprises multiple fragments of both written and printed texts, with instances where the content of the printed fragments corresponds to the rhyming portion of Text (1). Conversely, if the printed version of the text is determined to be from the Mongol period, it can be deduced that the alliterative verses extant in the Fumu Enzhong jing 父母恩重經, created in the 10th-11th centuries, were transmitted through successive generations of Buddhists in the Western Uyghur Kingdom until the Mongol period. This finding serves to refute G. Doerfer’s argument and further substantiates P. Zieme’s perspective.

The tradition of Manichaean and Buddhist literature was inherited and carried forward in the Western Uyghur period, and by the Mongolian period, the alliterative quatrains were prevalent. In the Yuan Dynasty, the Old Uyghur government officials played an important role. They translated the original Buddhist texts from Chinese or Sanskrit into the Old Uyghur language in the form of alliterative verse, or extracted the gāthās (skt. gāthā) from the original texts and rewrote them into Old Uyghur alliterative poems. The composition of these poems was undertaken in accordance with the original text, while also allowing for a significant degree of liberty. Additionally, there are instances where Buddhist scriptures in prose underwent a transformation into alliterative poems. In summary, the introduction of Old Uyghur alliterative quatrains into the Mongolian language occurred during the production of the Mongolian Buddhist scriptures in the first half of the 14th century.

In the following pages, Nakamura shifted his focus to alliterative verse in the Mongolian Buddhist texts from Turfan, noting that the alliterative verses in the Mongolian Buddhist texts from Turfan differed from the traditional alliterative verses in the

Secret History of the Yuan Dynasty. It was concluded that by the end of the thirteenth century, Mongolian alliterative poetry was influenced by Sanskrit

śloka (gāthā) and developed a four-line stanzaic structure (

Cerensodnom and Manfred 1993, p. 24). Although

G. Kara (

1981) does not explore this aspect in great detail, he notes the presence of the same form of alliterative stanzas as in the Old Uyghur Buddhist texts. These texts are characterized by a substantial presence of borrowings of Old Uyghur Buddhist terminology (

Shōgaito 1991). G. Kara hypothesizes that the alliterative verse, in conjunction with Buddhist terminology, was introduced into the Mongolian language from Old Uyghur sources (

Kara 1981). Nakamura supports Kara’s perspective, and to further substantiate his claim. The author cites additional compelling evidence beyond the alliterative verse. This includes the presence of Old Uyghur loanwords in the Mongolian scriptures, which are presented under the guise of alliterative verse. Furthermore, the punctuation mirrors that employed by the Old Uyghurs (two dots at the end of a line and four at the end of a stanza). Additional corroborating elements are provided in the form of the scriptures themselves, the use of Chinese characters in the pagination and the use of Brāhmī characters in the transliteration of Sanskrit-derived words. One potential indicator of the Mongolian alliterative versification found in the texts being of Old Uyghur origin is the utilization of borrowed expressions in the colophon. Nakamura’s discussion of the Secret History of the Yuan Dynasty (1271–1368) is also of particular interest. This text is notable for its absence of alliterative verse, a feature that is otherwise prevalent in Mongolian literature of the period. Moreover, with the exception of Buddhist literature, Mongolian literature of the 13th and 14th centuries does not contain alliterative verses. On the basis of these characteristics, Nakamura puts forward the hypothesis that the alliterative verses that appear in Mongolian Buddhist scriptures were influenced by the Old Uyghur language.

Finally, Nakamura discusses the identity of Čosgi Odsir (pp. 106–109), who is known as the earliest translator of Buddhist scriptures into Mongolian, and the historical background of his translation of Buddhist scriptures. The author suggests that during the thirteenth century in the Mongol Empire, Buddhism was only present among the ruling class. During this period, the Old Uyghur language became the dominant lingua franca in the eastern regions of the Mongol Empire. The aristocracy, which constituted the ruling class, predominantly used the Old Uyghur language, which facilitated the direct translation of Buddhist scriptures. This facilitated the articulation of Buddhist concepts and ideas through the medium of the Old Uyghur language. In the context of this historical analysis, Nakamura proposes a hypothesis concerning the authorship of the Mahākālī hymns by Čosgi Odsir. The hypothesis suggests that these hymns were composed using both Old Uyghur Buddhist terminology and alliteration, elements which were not part of the Mongolian tradition. Furthermore, the hypothesis extends to the colophon of the commentary on the Bodhicaryāvatāra, which is presented in the form of alliterative verses.

According to Nakamura (pp. 109–110), the Old Uyghur Buddhist scriptures played a pivotal role in the genesis of the Mongolian Buddhist classics in the first half of the 14th century. In the broader context of discussions of Mongolian Buddhist beliefs in the Yuan dynasty, the relationship between Mongolian Buddhism and Tibetan Buddhism is often emphasized. However, analysis of the Mongolian Buddhist literature excavated at Turfan reveals a paucity of Tibetan elements, with the characteristics of Old Uyghur Buddhist scriptures reflected in Buddhist terminology, alliterative verses, punctuation, colophons, and so on. While the introduction of Tibetan Buddhism into the Yuan dynasty was undoubtedly driven by political motivations, particularly the consolidation of royal power, it was not Tibetan Buddhism itself that provided the cultural foundation for Mongolian Buddhist beliefs. Instead, the development of ‘Old Uyghur Buddhism’ in the Western Uyghur region played a central role in this process.

5. Study of the Toponomy as Seen in Old Uyghur Buddhist Texts and Documents: Ningrong 寧戎 and Bezeklik in Old Uyghur Literature

Dai Matsui is one of the leading historians in Japan who has worked extensively on the history of Central Asia, with particular emphasis on Old Uighur documents and inscriptions. His research also includes extensive studies of Old Uyghur toponomy as seen in Buddhist texts, documents and inscriptions. His paper ‘Old Uyghur toponyms in Turfan oasis’ published in English (

Matsui 2015) is well known. However, the details of his paper ‘

Ning-rong 寧戎 and Bezeklik in Old Uigur texts’ published in Japanese (

Matsui 2011) are not known to Western scholars in much detail, although the main results of the paper have been summarized in

Matsui (

2015, pp. 283–88). In the following, I will try to introduce the paper in more detail.

In this paper, Matsui’s discussion focuses on the toponym Ning-rong 寧戎 referring to the Bezeklik Grottoes in Old Uyghur. The Bezeklik Grottoes are the closest Buddhist shrine to the Buddhist inhabitants of the ancient city of Qocho 高昌, located in the Turfan Basin of Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, China.

In the corpus of texts spanning from the 10th to the 14th centuries, the term ‘Bezeklig’ or ‘Bezeklik’ is observed in an alliterative poem inscribed in cursive script. In the verse under consideration, the word Bezeklig was transcribed as

bäṣäk-lig or

bäzäk-lik, and was translated as ‘(in ihrer) Pracht’ (=(in their) splendor) by Gabain and as ‘harem’ (=Harem) by Arat (see

Matsui 2011, p. 141). Despite these explanations, the connection between the name of the cave,

Bezeklig, and the word in the aforementioned poem remained unclear. In

Matsui (

2011), D. Matsui explores the connection between these words and the cave by examining the forms NYZWNK, NYSWNK, LYSWNK, which are present in various periods of Old Uyghur literature. He argues that these forms are actually the words

Nižüng,

Nišüng,

Lišüng, which are the Old Uyghur forms of the Chinese name of the Bezeklik Caves, Ningrong 寧戎. Concurrently, Matsui undertakes an analysis of related materials from the perspective of historical geography.

Matsui examines and analyzes four inscriptions from Bezeklik and five secular documents in relation to the Bezeklik Caves, based on their transcription and Japanese translation. The paper consists of two sections. The initial section (pp. 142–153) is an analysis and interpretation of the four inscriptions (A–D), with the primary objective being to demonstrate that

Nižüng,

Nišüng and

Lišüng are the Old Uyghur transcriptions of the word Ningrong 寧戎. The subsequent section (pp. 154–71) focuses on the five secular documents (E–I), which contain the aforementioned words,

Nižüng,

Nišüng and

Lišüng. As

Matsui (

2015, pp. 284–86) has provided a full transcription and English translation of these inscriptions and documents, we will refrain from repeating them here. The key commonality among these texts is that they all contain one of the aforementioned words. According to

Matsui (

2015, pp. 284–86), all of these word forms are, in fact, the names of the Bezeklik Cave.

In this section, D. Matsui also examines Old Uyghur words denoting cave or monastery, such as

qïsïl and

aryadan ~

aranyadan, which are attached to the respective names. In the Bezeklik Cave inscriptions A, B and C, according to D. Matsui, NYSWNK

aryadan ~

aranyadan in the inscription refers to the Bezeklik Cave monastery located in the Murtuq valley along the Flaming Mountains of the Tianshan Mountains. D. Matsui argues that the Bezeklik Caves were known as the Ningrong 寧戎 Caves before the Tang Dynasty. This claim is supported by the seminal works of 柳洪亮

Hongliang Liu (

1986, p. 58) and 百濟

Kudara (

1994, p. 4). Using the Uyghur pronunciation of Chinese characters proposed by M. Shōgaito, he transcribes NYSWNK as

Nišüng in the inscriptions A to C. As they were written in cursive script, he dates the inscriptions to the Yuan dynasty, from the 13th to the 14th century. He also suggests that 寧戎was known as

Nižüng during the Western Old Uyghur period. After the introduction of

Nižüng into Old Uyghur and its subsequent popularisation among the local population, the ž sound, which did not exist in Old Uyghur, was replaced by the

š sound, which is inherent to the Old Uyghur language.

It is evident that the majority of Old Uyghur inscriptions in Buddhist caves in Central Asia are pilgrim inscriptions. Consequently, Matsui posits that the LYSWNK in the phrase ‘“stopped at LYSWNK’ inscribed in source D corresponds to the same Buddhist site that the scribe visited, namely, the Bezeklik Caves. This claim is supported by Matsui’s transcription of the phrase as Lišüng, in which the l sound at the beginning of the word is assumed to be a variant of n-.

After a series of discussions on the pronunciation of ‘Bezeklik Caves’ and its variants in Old Uyghur based on the inscriptions in the first part of the section, Matsui then focuses on the secular documents, examining the sources E ~ I, taking the appearance of Ningrong 寧戎 as a clue. He explores the contents of the documents, their orthography, and the places where they were excavated.

Of particular importance is his discussion of Document E. This is, in fact, the famous Manichaean text known as the

Official Decree of the Manichaean Monastery, first published in facsimile in Huang Wenbi 黄文弼’s

Tulufan Kaoguji 吐魯番考古記 (Turfan Archaeological Records) in 1954 (

Huang 1954) and edited first by Geng Shimin in 1979. Geng Shimin’s paper was published in a revised English version (

Geng 1991) and then by

T. Moriyasu (

1991), and recently by

Larry Clark (

2017, pp. 325–58). D. Matsui proposes the transcription

Niž̤üng for the word transliterated by Moriyasu as NYZ̤WNK. According to him, this is the oldest form of transliteration for Ningrong 寧戎, in which two dots were added to <z> in the original text to make the

ž sound clearer. The reference to

Niž̤üng in the text seems to correlate with a large area of taxed farmland, which is unlikely to have existed in the ravine near the Bezeklik cave. Consequently, Matsui proposes the hypothesis that the term Ningrong 寧戎 does not refer exclusively to monasteries, as evidenced by the existence of names such as Ningrong 寧戎 Caves, Ningrong 寧戎 Cave Temple; and Ningrong Monastery 寧戎阿阑若, but may also include administrative counties or villages, including Ningrong County 寧戎县 and Ningrong Township 寧戎鄉. To further substantiate this hypothesis, Matsui provides a comprehensive list of leased farmlands belonging to Manichaean monasteries in several locations, including Buqapčï, Tura suzaq, Qongḍsir, and others. Through careful study of these sites and their contemporary counterparts, D. Matsui ultimately hypothesizes that the Manichaean monasteries in Yar-khoto or Qocho (Gaochang 高昌) were located in places such as Ningrong 寧戎 (Nižüng), Hengjie 横截 (Qongtsir) and other places north of Flaming Mountain. This provides a solid reference point for studying the economic scale and actual situation of Manichaean monasteries in the Western Old Uyghur period.

The other document (Document F, U 5288 (T M 77, D 51)) is thought to date from the mid- to late-14th century. However, due to the incomplete nature of the document, in particular the missing second half, the exact dating remains uncertain. Matsui proposes a revised interpretation of Lišüng vaxar in line 13, a term that had previously proven challenging to decipher. This interpretation is presented as a crucial clue, suggesting that the document in question is of an administrative nature, specifically an administrative record, relating to the taxation of distilled wine on Uyghur residents and vineyards associated with Taicang Monastery 太倉寺 and Ningrong Monastery 寧戎寺. The document’s function as an administrative record is clear, as it refers to the taxation of distilled spirits on the Uyghur population and the vineyards belonging to Taicang Temple and Ningrong Temple. The phrase Lišüng vaxar mentioned in the document is more likely to refer to the Bezeklik Caves. However, if Ningrong 寧戎 is indeed the name of an administrative district, then it is possible that all the monasteries in the area were collectively called Ningrong Monastery 寧戎寺. Matsui considers the term Lišüng vaxar as a clue to the location of the vineyard to which it belongs. Although he does not offer a definitive conclusion, he presents two hypotheses regarding the location of the vineyard: one near the temple and the other far from the town of Qocho (Gaochang 高昌). The geographical information contained in the term Lišüng vaxar provides important insights into the economic foundations of the Old Uyghur Buddhist monasteries during the Mongol period, as well as the operational dynamics of the system for collecting public goods and taxes.

Matsui’s analysis of another source (Document G), Ch/U 6245v (T III M 117), is also of particular importance. This is an Old Uyghur letter written in cursive script on the verso of a Chinese text. It is currently preserved in the Berlin Turfan Collection. A brief summary of the document has been given by

P. Zieme (

1975, p. 248), but a comprehensive study has yet to be undertaken. Matsui’s contribution includes the transcription, translation and annotation of the document. Matsui then discussed the provenance of the document, concluding that the M=Murtuq in the document’s find signature probably refers to the Bezeklik Cave, or alternatively to the document’s acquisition by the German expedition from the local population in Murtuq. The analysis also revealed two other tax-free privileges with the find signature ‘Murtuq’, namely, U 5317 (T III M 205) and U 5319 (T III M 205c). These contain the phrase

Murutluq aryadan, which lends further credence to the hypothesis that Bezeklik Cave is the site in question. The site was a very influential Buddhist monastery, to the extent that it was granted tax-exempt status by the Western Uyghur Kingdom.

Another text that was used to support Matsui’s thesis is a fragment of a mural painting of the Bodhisattva of Sacrifice, currently kept in the National Museum of Korea (No. 4049, = Document H in Matsui’s article). This fragment was retrieved from Cave 4 of Bezeklik by the Ōtani Expedition and bears an inscription in cursive script on the right side.

Matsui’s discussion (

2011, pp. 165–68) identifies two primary reasons for the discrepancy between

Murutluq aryadan and Ningrong Cave 寧戎峡谷, i.e., Bezeklik Cave Monastery. According to Matsui, the sources A, G and H, in which these two names appear, belong to the same period, i.e., the 13th–14th centuries. It is implausible that the people of that era would have referred to the Bezeklik Caves by two distinct names, such as Ningrong Cave and Muruḍtuq Cave, and the name Bezeklik Caves is not synonymous with Muruḍtuq Cave.

It is noteworthy that in the text currently housed in the Museum of Korea (Document H), the word for

Muruḍtuq Cave exhibits the accusative ending

-tïn. This is interpreted by Hiroshi Umemura and Min Byung-hoon (

Umemura and Min 1995) as an indication of the scribe’s place of origin. Conversely, Matsui interprets it as an ending denoting the place of departure, i.e., ‘I went from Muruḍtuq Cave to Bezeklik Cave’. With regard to the

Murutluq aryadan monastery, Matsui advances the argument that A. Stein’s proposition that the Murtuk Ruins are synonymous with the contemporary location of

ujan? = b

ulaq? Indicates the presence of a substantial Buddhist community in the region extending to the time of the Yuan dynasty, and that the

Murutluq aryadan monastery constituted a significant element of this community. It is highly probable that the

aryadan monastery was situated within this area.

The most significant contribution of Matsui’s analysis of Document I (*U 9053) is the new transcription and interpretation of the text. Firstly, Matsui revises the word originally transcribed by O. Sertkaya as lešük to lišüng, which he interprets as the place name referring to Ningrong 寧戎. Secondly, Matsui challenges Sertkaya’s assertion that lines 1–3 of the document are legal documents, proposing instead that it is a memorial inscription created by a pilgrim residing in Lišüng, specifically in Ningrong 寧戎 Monastery.

Since the publication of D. Matsu’s article, several new sources have been published that are directly related to the toponymic and monastic illustrations discussed in D. Matsu’s article. In

Shōgaito et al. (

2015, p. 65) we find

nyswnk q’dwn ṅy sy, which has been reconstructed as 寧戎 qadun 尼師. As it occurs together with several monastery names, it is important in determining the place of Ningrong 寧戎 in the region.

It is evident that D. Matsui’s contributions to the field of Old Uyghur philology have been significant. His work has not only advanced our understanding of the subject but has also led to the identification of several significant Buddhist sites in the Turfan region.