Abstract

This study provides a comprehensive philological analysis of ten Old Uyghur manuscript fragments of the Saddharmapuṇḍarīka-sūtra (Lotus Sutra) in the Berlin Turfan Collection, while systematically examining all extant Old Uyghur Lotus Sutra manuscripts to establish a complete corpus for comparative analysis. By collating this complete corpus with Kumārajīva’s Chinese translation, this research demonstrates a typology of Old Uyghur Lotus Sutra fragments. It identifies at least two distinct translation lineages: (1) early translations (pre-10th century) exhibiting lexical and structural divergences indicative of Sogdian mediation or hybrid source traditions, and (2) late translations (11th–14th centuries) directly derived from the Chinese version, characterized by syntactic fidelity and a standardized terminology. Through comparative textual analysis, orthographic scrutiny, and terminological cross-referencing, this paper aims to reconstruct the historical trajectory of the Lotus Sutra’s transmission. In addition, it discusses some facts indicating linguistic and cultural contact between the Sogdians and the progressive alignment of Uyghur Buddhist texts with Chinese Buddhist traditions.

1. Introduction

The manuscripts of major Mahāyāna sūtras, including the Vimalakīrtinirdeśa, Suvarṇaprabhāsa-sūtra, and Buddhāvataṃsaka-sūtra, are extant in Old Uyghur translations and have been edited (see, for example, Yakup 2021). In contrast, the Old Uyghur translation of the Saddharmapuṇḍarīka-sūtra (hereafter referred to as the Lotus Sutra), one of the most popular Mahāyāna sūtras in Central Asia, is known from a relatively small number of fragments and has not yet been fully edited. The extant material consists of several fragments of the sūtra, corresponding to different chapters.

A substantial proportion of extant Uyghur fragments of the Lotus Sutra derive from chapter 25 of Kumārajīva’s Chinese version, which also circulated independently as the 觀音經 guānyīn jīng. These fragments have been the subject of study by F. W. K. Müller (1910), W. Radloff (1911), T. Haneda (1915), S. Tekin (1960), G. Hazai (1970), P. Zieme (1985), Zhang (1990), J. Oda (1991, 1996, 2000, 2008), M. Shōgaito (1988), Özcan (2020), and U. Uzunkaya (2023, 2024).

Other fragments of the Old Uyghur Lotus Sutra are extant from various other chapters, including the 3rd, 4th, 5th, 9th, 12th, 15th, 16th, 17th, 23rd, 24th, 26th, 27th, and 28th. However, it should be noted that none of these fragments are in a state of complete preservation.

The Turfan Museum holds the fragment 80TBI: 527, which belongs to the 9th chapter and is a pustaka fragment. This was edited by Zhang (2010). Another fragment has been identified as belonging to the 12th chapter of the Old Uyghur Lotus Sutra. The initial editing of this fragment was undertaken by Tachibana (1913). In 1989, P. Zieme identified two additional fragments of the Old Uyghur Lotus Sutra, which separately belong to the 23rd and 26th chapters (Zieme 1989). In 2000, P. Zieme identified another fragment, U 1511, from the Berlin Turfan Collection, which belongs to the 24th chapter of the Lotus Sutra (Zieme 2000). Two further fragments, Mainz 225 (T D/T M 409) and Mainz 309 (T M 257-6), which belong to the 27th chapter of the Old Uyghur Lotus Sutra, were first edited by D. Fedakâr, along with two other fragments, Mainz 170, and Mainz 183. However, the precise locations of these fragments have not been specified (Fedakâr 1991, 1994, 1996). Mainz 225 and Mainz 309 were re-edited by P. Zieme (1998), who also identified the exact locations of these two fragments. Moreover, two extant fragments, designated MIK III 195 and MIK III 199 from the Museum für Asiatische Kunst, are recognized as part of the 28th chapter of the Lotus Sutra. These fragments were edited by Maue and Röhrborn (1980).

Most recently, P. Zieme (2025) has made a significant contribution to the field by analyzing two Old Uyghur block-printed fragments from the Berlin Turfan Collection: U 4780 (TM 31) and Mainz 490 (T III D). These fragments constitute a special concertina booklet that presents chapter titles and representative quotations from chapters 11–24 of the Lotus Sūtra. This discovery is very important as it provides evidence of a systematic guide or overview of the Lotus Sutra used by Uyghur Buddhists, demonstrating the extent to which they studied this text. The booklet appears to be based on Kumārajīva’s Chinese translation, consistent with the predominant textual tradition in Central Asia, and represents a unique bibliographical tool that allows quick reference to different chapters of the Lotus Sutra (P. Zieme 2025).

Despite these important contributions, significant gaps remain in our understanding of the Old Uyghur Lotus Sutra transmission, particularly in chapters 3, 4, 5, 16, and 17, which have not been subjected to a full systematic textual analysis.

Building on this foundation of previous scholarship, this paper presents a comprehensive textual edition of Old Uyghur Lotus Sutra fragments from chapters 3, 4, 5, 16, and 17, which have not been previously subjected to systematic textual analysis. While some of these manuscript fragments have been noted in earlier scholarship, they have not undergone comprehensive philological examination or been properly identified in terms of their specific textual correspondence with the original sutra. There are also fragments of the text from Chapter 15, and further analysis of this particular chapter is currently underway.

These manuscript fragments are currently housed in the Berlin Turfan Collection at the Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences and Humanities in Germany. The basic physical characteristics of fragment U 1872 and the composite text U 2112 + U 2113 + U 2114 + U2115 were briefly catalogued by Z. Özertural (2012). Moreover, P. Zieme’s preliminary identification of these two fragments (Zieme 2005) contained inaccuracies, notably in the placement of the verso of U 1872. A further 27 fragments correspond to chapters 15–17 of the Lotus Sutra, referenced in P. Zieme’s conference report (2005) and subsequently presented with specific manuscript numbers in J. Oda’s footnotes (Oda 2008), have yet to be systematically investigated. They were not included in Özertural’s catalogues published in 2012 and 2021 (Özertural 2012, 2021). The present edition also constitutes an initial investigation of these fragments. It classifies them according to their locations in Kumārajīva’s Chinese translation and linguistic characteristics within the typological framework presented at the end of this work, providing a complete overview of the textual corpus and its chronological development.

2. Texts: Description and Text Edition with Commentaries

2.1. A Brief Description

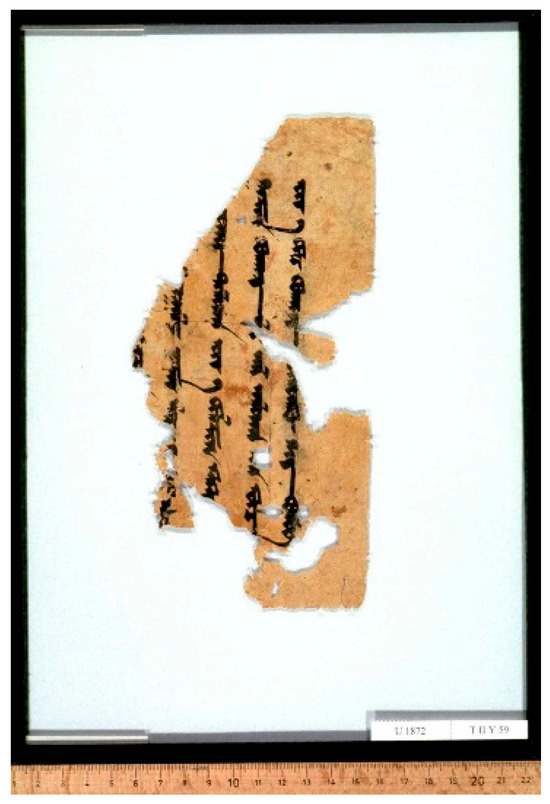

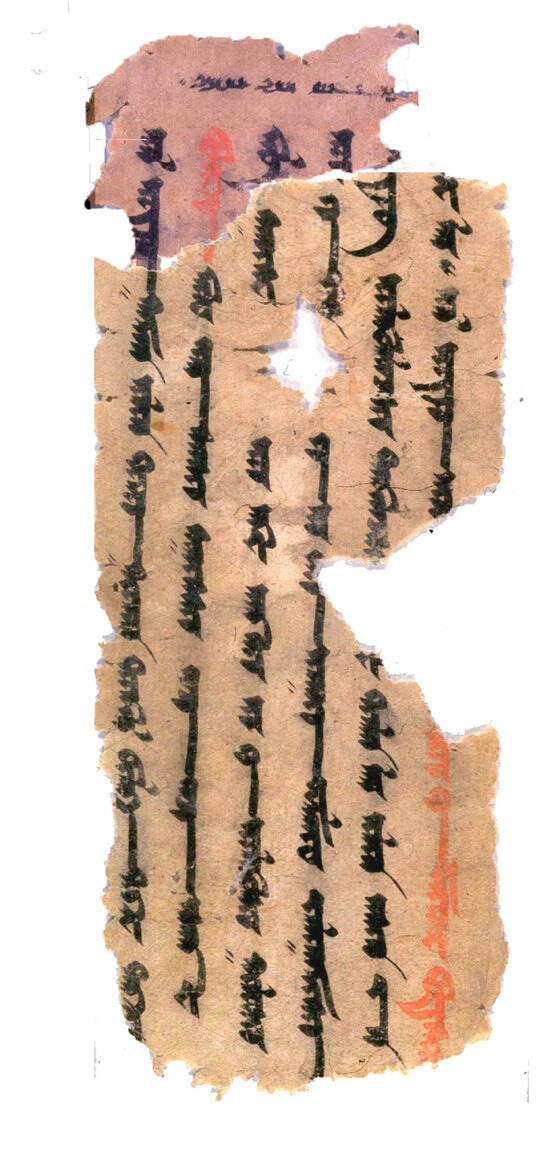

- A. U 1872

The physical characteristics and dimensions of fragment U 1872 have been documented by Özertural (2012, p. 83, Nr. 79); therefore, these details will not be repeated here. The content of the fragment corresponds to Chapter 3 of the Chinese version of the Lotus Sutra, translated by Kumārajīva.

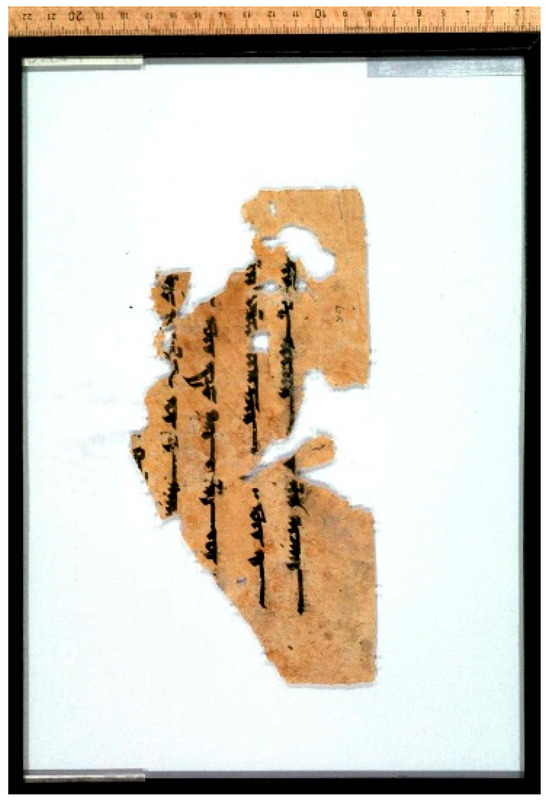

- B. U 2112 + U 2113 + U 2114 + U 2115

The physical characteristics of the composite text U 2112 + U 2113 + U 2114 + U 2115 are also documented by Özertural (2012, pp. 83–85, Nr. 80). The recto text is derived from Chapter 4 of the Lotus Sutra, with the verso introducing Chapter 5.

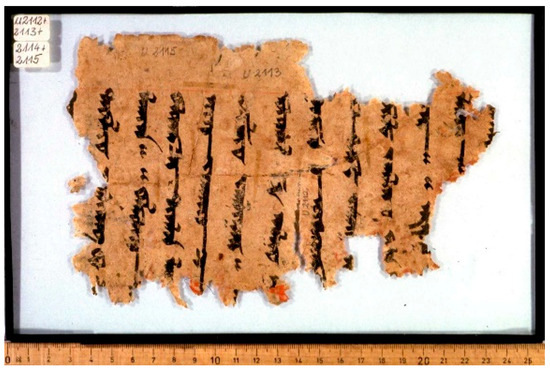

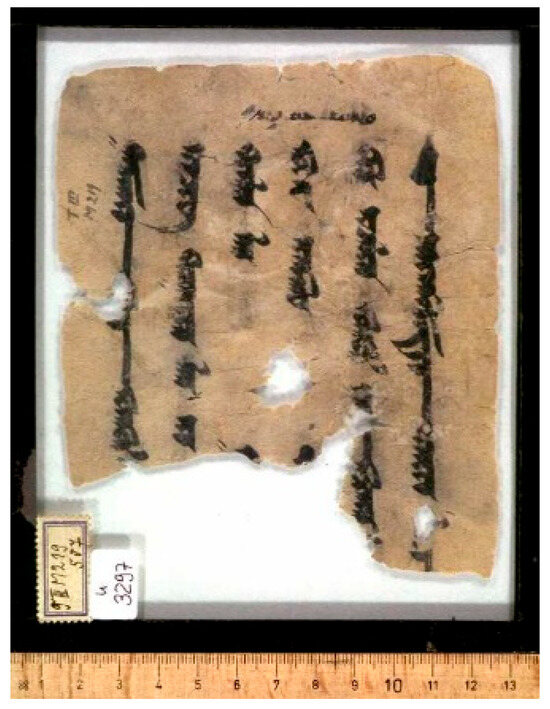

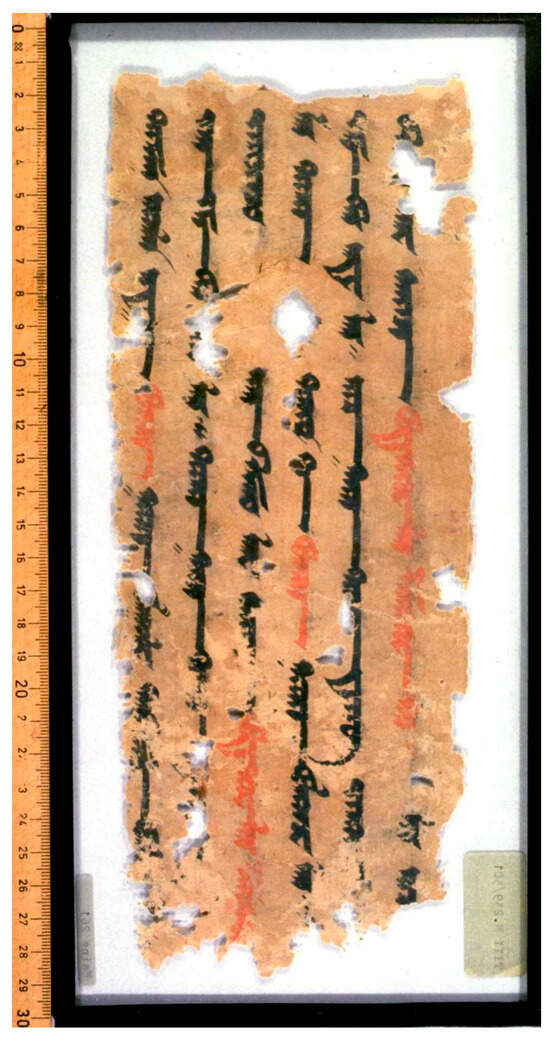

- C. U 3297

This bifolio fragment (recto and verso) retains six lines of Old Uyghur script on each side in black ink. Only the upper half of the sheet survives, with the lower half missing. It lacks red ruling, color annotations, or corrections, distinguishing it from U 1872 and U 2112 +. The text is from Chapter 16 of the Lotus Sutra, translated by Kumārajīva.

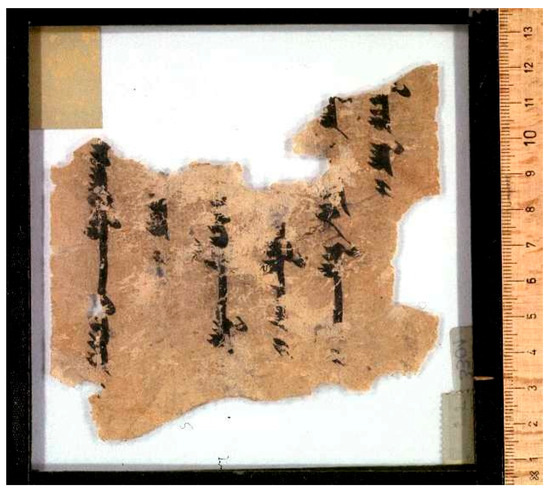

- D. U 3301

Part of the U 3297 group, this bifolio fragment preserves only the lower 20% of the original leaf, with the upper 80% missing. Both sides contain six lines of black-ink Old Uyghur script adhering to the manuscript’s standardized format. No red rules or annotations were present. Severe fragmentation obscures the margins, but the surviving text aligns stylistically with U 3297. Similar to U 3297, it originates from Chapter 16 of the Lotus Sutra.

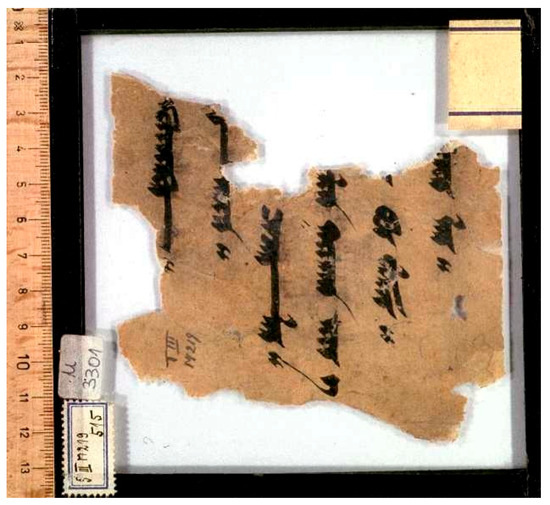

- E. U 3314 + U 2422

These digitally reconstructed fragments formed a complete leaf–with six lines per side. The recto concludes chapter 16 of the Lotus Sutra, while the verso begins chapter 17. The names of Buddhas and Bodhisattvas are highlighted in red ink, emphasizing their sacredness. The script style and red annotations align with the U 3301/U 3279 group, confirming their shared manuscript series.

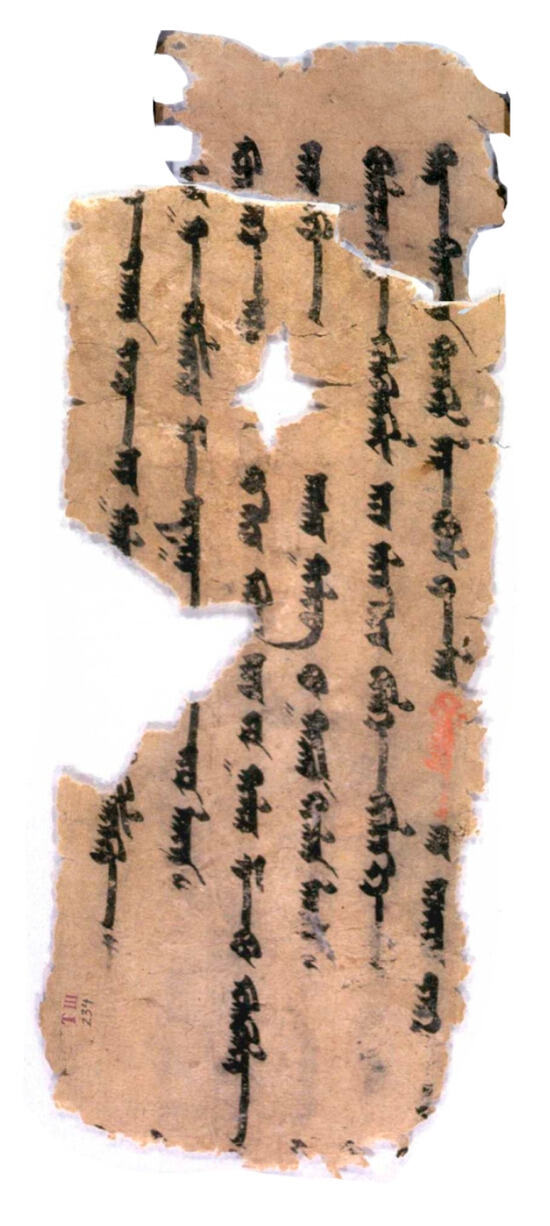

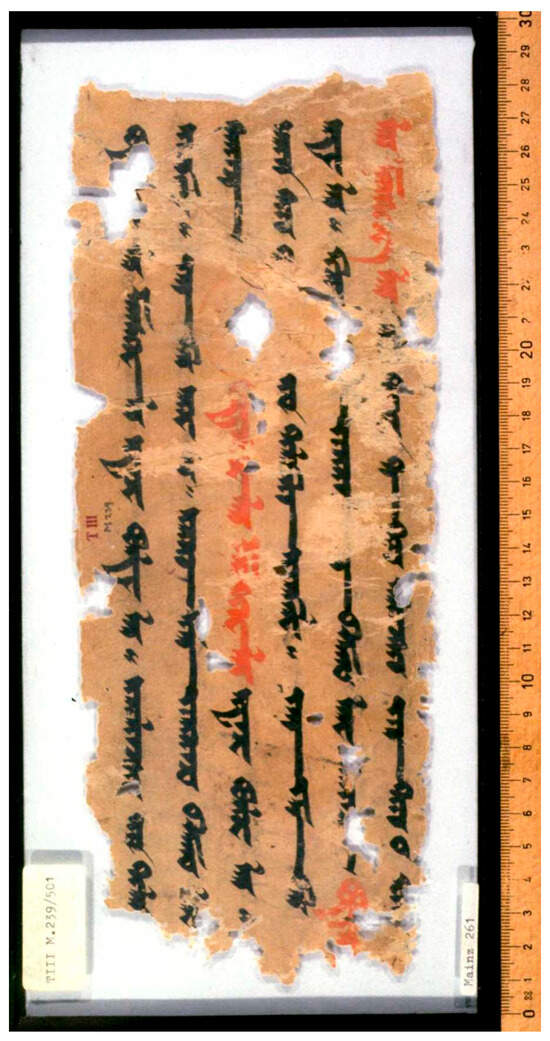

- F. Mainz 261

This bifolio fragment (recto and verso) preserves six lines of Old Uyghur script per side in black ink, with the names of Buddhas and Bodhisattvas highlighted in red. Approximately 95% of the text remains legible despite margin damage and scattered small holes, none of which obscure the critical content. The prose text is derived from Chapter 17 of the Lotus Sutra.

2.2. Edition: Transcription, Transliteration, Parallel Text, Translation, and Commentaries

- A. U 1872

- Recto (see Figure 1)

| 01 | 1 | […………………………………………..] |

| ////////////////////m////////////////////////////// | ||

| 02 | 2 | [………….]galı umazl(a)r. š[ariput]re |

| ////////////////qʾly ʾwmʾz lr ,, s//////////ry | ||

| 03 | 3 | [……a]vant tıltag üzä bilmiš k(ä)rgä[k] |

| /////////vʾnt tyltʾq ʾwyz ʾ pylmys krkʾ/// | ||

| 04 | 4 | kamag burhanl[a]r al altag ok küč[in] |

| qʾmʾq pwrqʾn l///r ʾʾl ʾʾltʾq ʾwq kwyc/// | ||

| 05 | 5 | üzä bir burhan [k]ölüngüsin bölüp |

| ʾwyz ʾ pyr pwrqʾn ///wylwnkw syn pwlwp |

Figure 1.

U 1872 Recto. © Depositum der BERLIN-BRANDENBURGISCHEN AKADEMIE DER WISSENSCHAFTEN in der STAATSBIBLIOTHEK ZU BERLIN—Preußischer Kulturbesitz Orientabteilung.

Verso: (see Figure 2)

| 06 | 1 | [……………………t……………………] |

| //////////////////////////t/////////////////////// | ||

| 07 | 2 | [……]l(a)rı [……] uzun sak[al………] |

| //////// lry /////l///// ʾwz wn sʾq/////////// | ||

| 08 | 3 | [….] küzädči k(a)ra y[ı]lan yüz [adak] |

| ////// kwyz ʾdcy qrʾ y///lʾn ywz //////////// | ||

| 09 | 4 | l(ı)g ulug örümčik. küzen |

| lq ///wlwq ///wyrymcyk,, kwyz yn | ||

| 10 | 5 | miškič süčig […]zl(ı)k sıčgan |

| myskyc swycyk ///z lq sycqʾn |

Figure 2.

U 1872 Verso. © Depositum der BERLIN-BRANDENBURGISCHEN AKADEMIE DER WISSENSCHAFTEN in der STAATSBIBLIOTHEK ZU BERLIN—Preußischer Kulturbesitz Orientabteilung.

何以故?如來有無量智慧、力、無所畏諸法之藏,能與一切眾生大乘之法,但不盡能受。舍利弗,以是因緣,當知諸佛方便力故,於一佛乘分別說三。佛欲重宣此義,而說偈言:“如長者,有一大宅,其宅久故,而複頓弊,堂舍高危,柱根摧朽,梁棟傾斜,基陛隤毀,牆壁圮坼,泥塗褫落,覆苫亂墜,椽梠差脫,周障屈曲,雜穢充遍。有五百人,止住其中。鴟梟雕鷲,烏鵲鳩鴿,蚖蛇蝮蠍,蜈蚣蚰蜒,守宮百足,狖狸鼷鼠,諸惡蟲輩,交橫馳走。”(T0262_.09.0013c14-26)

Translation of the Old Uyghur text:

(1–5) [...] can not [...] Śāriputra […] For this reason, you should understand that all Buddhas have used the power of expedient means to divide this unique Buddha vehicle [...]

(6–10) [………] long beard [………] guard, which is a black snake, a big spider with a hundred [feet], a polecat, a cat, and a little […] mouse [...]

Commentary:

bölüp (line 05) is written as pwlwp.

uzun sak[al………] (line 07) is the Old Uyghur translation of the Chinese 蚰蜒 yóuyán “scutiger”. Based on the translation characteristics of this fragment, the translator often uses descriptive vocabulary to translate content for which there are no corresponding words in Old Uyghur. Therefore, uzun sakal might be describing the long segmented legs of a scutiger, and there should be a name for an insect familiar to the translator following sakal, similar to “scutiger”.

küzädči k(a)ra y[ı]lan (line 08) is the Old Uyghur translation of the Chinese 守宮 shǒugōng “gecko”. The Chinese 守宮, when taken literally, translates to “guardian of the palace.” In the Old Uyghur text, küzädči corresponds to the translation of “guard” or “protector” and k(a)ra y[ı]lan (black snake) seems to be a further description of the “gecko.”

yüz [adak]l(ı)g ulug örümčik (lines 08–09) is the Old Uyghur translation of the Chinese 百足 bǎizú “centipede”. The “Centipede,” also known as “myriapoda,” is an arthropod with many body segments. The translator’s expression here, when taken literally, is “a larg spider with a hundred feet,” which is a description of a “centipede.” In the fragment, only the translation of “hundred” remains as yüz, and based on the context, it should be supplemented with the translation of “foot” as adak. örümčik is written as ‘wyrymčyk.

küzen miškič süčig […]zlık sıčgan (line 10) is the Old Uyghur translation of the Chinese 狖狸鼷鼠 yòulí xīshǔ. The character 狖 yòu refers to a mythical creature resembling a “fox” as described in ancient texts, and 狸 lí is a member of the cat family. Therefore, the translator might have used küzen miškič (polecat, cat) to translate 狖狸 yòulí. The origin of küzen is explained by Clauson as “a very old word, a First Period loan word in Mong. as küreme and Hungarian as görény. This suggests that this word is connected to a Mong word. küren/küreñ ‘brown’, which later became a loanword in some Turkish languages, is improbable on phonetic grounds, but not impossible” (Clauson 1972). miškič derives from Sogdian mwškyšc ~ mwškyc ‘cat’ (Wilkens 2021), demonstrating linguistic contact in Buddhist text transmission. Following this, 鼷鼠 xīshǔ refers to the smallest type of rodent, and süčig […]zlık sıčgan seems to be a descriptive phrase for 鼷鼠 xīshǔ. The compound […]zlık sıčgan likely contains an adjective with the suffix -lık modifying sıčgan ‘mouse/rat’, creating, together with süčig, a descriptive phrase for the Chinese term.

- B. U 2112 + U 2113 + U 2114 + U 2115

- Recto (see Figure 3)

| 11 | 1 | […………………………………………….] |

| //////////////////////////////////////////////////////// | ||

| 12 | 2 | taplayu y[a]rlıkap bo č[ …………………] |

| tʾplʾyw y///rlyqʾp pw c////////////////////////// | ||

| 13 | 3 | larıg. b(ä)lgüsin [………………………….] |

| lʾryq,, ,, plkwsyn /////////////////////////////// | ||

| 14 | 4 | prtagčan tınl(ı)gl(a)r [………………………] |

| prtʾkcʾn tynlq lr ///////////////////////////////// | ||

| 15 | 5 | eyin yaragınča […………………………....] |

| ʾyyyn yʾrʾqyn cʾ ////////////////////////////////// | ||

| 16 | 6 | nomlayu y(a)rlıkar. [………………..…atı] |

| nwmlʾyw yrlyqʾr,, ,, /////////////////////////// | ||

| 17 | 7 | kötrülm[i]š alku [burhanlar……………..] |

| kwytrwl m///s ʾʾlqw ////////////////////////////// | ||

| 18 | 8 | kamag[t]a üstünk[i .................ärksinmäk] |

| qʾmʾq ///ʾ ʾwystwnk//////////////////////////// | ||

| 19 | 9 | kä tägi y(a)rlık[ar……………………........] |

| kʾ tʾky yrlyq/////////////////////////////////////// | ||

| 20 | 10 | gäli y(a)rlık[a]p kim [……………………..] |

| kʾly yrlyq///p kym //////////////////////////////// | ||

| 21 | 11 | [...]äk. adrok [adrok…………………….....] |

| ////ʾk,, ,, ʾʾdrwk ///////////////////////////////////// | ||

| 22 | 12 | lärig. [………………………………………] |

| lʾryk,, ///////////////////////////////////////////////// | ||

| 23 | 13 | [………………………………………………] |

| ////////////////////////////////////////////////////////// |

Figure 3.

U 2112 + U 2113 + U 2114 + U 2115 Recto. © Depositum der BERLIN- BRANDENBURGISCHEN AKADEMIE DER WISSENSCHAFTEN in der STAATSBIBLIOTHEK ZU BERLIN—Preußischer Kulturbesitz Orientabteilung.

Verso: (see Figure 4)

| 24 | 1 | [………....]čä ö[......] tep teyü |

| //////////////cʾ ʾwy///// typ tyyw | ||

| 25 | 2 | . . . |

| ,, ,, ,, | ||

| 26 | 3 | […………….] nom čäčäki atl(ı)g |

| ///////////////// nwm cʾcʾky ʾʾtlq | ||

| 27 | 4 | [sudur……………..] bešinč ot |

| ///////////////////////// pysync ʾwt | ||

| 28 | 5 | [yaš yöläšürüg] bölük bašlantı. |

| /////////////// pwylwk pʾslʾnty,, ,, | ||

| 29 | 6 | [ol üdün tü]käl bilgä t(ä)ŋri |

| /////////////////kʾl pylkʾ tnkry | ||

| 30 | 7 | [t(ä)ŋrisi burhan] m(a)hakašip[e] arhant |

| //////////////////////////// mqʾkʾsyp/// ʾrqʾnt | ||

| 31 | 8 | [ka……………….]mak m(a)has(a)t(a)vka |

| ////////////////////////mʾq mqʾstvkʾ | ||

| 32 | 9 | [……………………………………in]čä tep |

| ///////////////////////////////////////////////cʾ typ | ||

| 33 | 10 | […………….ädg]ü ädgü m(a)hakašipe |

| ////////////////////////w ʾdkw mqʾkʾsypy | ||

| 34 | 11 | [………………………….………..]sidin |

| ////////////////////////////////////////////sydyn | ||

| 35 | 12 | […………………………………………...ä]d[g]ülärig |

| //////////////////////////////////////////////////////d///w lʾryk |

Figure 4.

U 2112 + U 2113 + U 2114 + U 2115 Verso. © Depositum der BERLIN- BRANDENBURGISCHEN AKADEMIE DER WISSENSCHAFTEN in der STAATSBIBLIOTHEK ZU BERLIN—Preußischer Kulturbesitz Orientabteilung.

諸佛稀有,無量無邊,不可思議,大神通力!無漏無為,諸法之王,能為下劣,忍於斯事,取相凡夫,隨宜為說。諸佛於法,得最自在,知諸眾生,種種欲樂,及其志力,隨所堪任,以無量喻,而為說法。隨諸眾生,宿世善根,又知成熟,未成熟者,種種籌量,分別知已,於一乘道,隨宜說三。第五 藥草喻品爾時,世尊告摩訶迦葉及諸大弟子:“善哉!善哉!迦葉,善說如來真實功德。誠如所言,如來複有無量無邊阿僧祇功德,汝等若於無量億劫說不能盡。”(T0262_.09.0019a05-07)

Translation of the Old Uyghur text:

(11–23) [………] willingly announce these [….] appearance [….] ordinary beings [….] according to […….], teach […….], the world-honored all [Buddhas….] teach to achieve the great [omnipotence], teach [……] various kinds of [……]

(24–35) [……] said that. [……] the Dharma called Lotus [Sutra….]. Fifth chapter, [medicinal] herbs’ [metaphors] begin. [At that time], the all-knowing, [god of the] gods, [Buddha …… to] Mahākāśyapa, all great disciples [………] said that “Excellent! Excellent! Mahākāśyapa” [……] from [………] merits.

Commentary:

b(ä)lgü (line 13) is the Old Uyghur translation of Chinese 相 xiàng. The term means “figure, appearance, form, or shape.” The Chinese相xiàng has many corresponding terms in Sanskrit, such as lakṣaṇa, nimitta, ākāra, and liṅga, etc. (Chen 2021). In Old Uyghur Buddhist texts, the related terms are translated as follows: 惡相 yavız b(ä)lgülär/yavlak b(ä)lgü.

prtagčan (line 14) is the Old Uyghur translation of the Chinese 凡夫 fánfū “ordinary being”. The term derives from the Sanskrit pṛthagjana (Wilkens 2021, p. 562). In the Buddhist context, it refers to a sentient being who is still bound by the ten fetters (saṃyojana) and has not yet attained the status of a noble person (Buswell and Lopez 2014).

nom čäčäki atl(ı)g [sudur…..] (lines 26–27) is the Old Uyghur translation of the Chinese 法華經 fǎhuájīng “Lotus Sutra”. The Sanskrit title is Saddharma-puṇḍarīkasūtra. There are various versions of the translation of the title of the Lotus Sutra into Old Uyghur. For detailed information, see the work presented by Abdurishid Yakup (2011).

ot [yaš yöläšürüg] bölük (lines 27–28) is the Old Uyghur translation of the Chinese 藥草喻品 yàocǎoyùpǐn “Chapter of the Parable of Medicinal Herbs” (Chapter 5 of the Lotus Sutra). The compound ot [yaš] translates Chinese 藥草 yàocǎo “medicinal herbs/plants”. The term yöläšürüg is a deverbal noun derived from the verb yöläšür- “to resemble” with the nominal suffix -(X)g (Clauson 1972, p. 933a; Yakup 2011). In this context, yöläšürüg corresponds to Chinese 喻 yù “parable, metaphor, simile”. Although the complete chapter title is not preserved in our fragment, it can be reconstructed based on the textual content and its usage in other Old Uyghur Lotus Sutra manuscripts.

- C. U 3297

Recto (see Figure 5)

| 36 | 1 | m(ä)n [ü]rüg uzatı mäŋün [………………...] |

| mn ///yrwk ʾwz ʾty mʾnkwn //////////////////// | ||

| 37 | 2 | kamag küü-kälig äd[rä]mlik [......................] |

| qʾmʾq kww kʾlyk ʾd////mlyk /////////////////// | ||

| 38 | 3 | tätrülm[ä]k (P) [.....................................................] |

| tʾtrwlm///k (P) /////////////////////////////// | ||

| 39 | 4 | yakın kälsär (P) l(ä)[r……………………….........] |

| yʾqyn kʾlsʾr (P) l//////////////////////////////// | ||

| 40 | 5 | kamag kuvrag körsärl(ä)r [.............................] |

| qʾmʾq qwvrʾq kwyrsʾr lr ////////////////////////// | ||

| 41 | 6 | keŋürü tapıg udug kıl [……………………....] |

| kynkwrw tʾpyq ʾwdwq qyl/////////////////////// |

Figure 5.

U 3297 Recto. © Depositum der BERLIN-BRANDENBURGISCHEN AKADEMIE DER WISSENSCHAFTEN in der STAATSBIBLIOTHEK ZU BERLIN—Preußischer Kulturbesitz Orientabteilung.

Verso: (see Figure 6)

| 42 | 0 | bešinč y(e)tmiš |

| pysync ytmys | ||

| 43 | 1 | kamagun b[arč]a köŋül [………………………] |

| qʾmʾqwn p//////ʾ kwnkwl ////////////////////////// | ||

| 44 | 2 | inčip turkarurl(a)r uz[…………………………..] |

| ʾyncyp twrqʾrwr lr ʾwz /////////////////////////////////// | ||

| 45 | 3 | tınl(ı)gl(a)r k[……………………………………....] |

| tynlq lr (P) q/////////////////////////////////////////// | ||

| 46 | 4 | köni oŋaru y[…………………………………………] |

| kwyny ʾwnkʾrw (P) y////////////////////////////// | ||

| 47 | 5 | bir učlug köŋül üz[ä] körük […………………….] |

| pyr ʾwclwq kwnkwl ʾwyz /// kwyrwk//////////////////// | ||

| 48 | 6 | [...] äsirkämätin ät’özl(ä)[ri]n [.......................................] |

| ///? ʾsyrkʾmʾdyn ʾtʾwyz l///n///////////////////////////////// |

Figure 6.

U 3297 Verso. © Depositum der BERLIN-BRANDENBURGISCHEN AKADEMIE DER WISSENSCHAFTEN in der STAATSBIBLIOTHEK ZU BERLIN—Preußischer Kulturbesitz Orientabteilung.

我常住於此,以諸神通力。令顛倒衆生,雖近而不見。衆見我滅度,廣供養舍利。鹹皆懷戀慕,而生渇仰心。衆生既信伏,質直意柔軟。一心欲見佛,不自惜身命。(T0262_.09.0043b18-23)

Translation of the Old Uyghur text:

(36–41) I always and forever […] various spiritual powers […] delude […] if they come close […], If all beings see […], they make extensive offerings […]

(42) fifth seventy

(43–48) all feelings […], such longing […], beings […], true […], with single-mind see […], not sparing their own bodies […]

Commentary:

küü-kälig äd[rä]mlik (line 37) is the Old Uyghur translation of the Chinese 神通 shéntōng “supernormal powers”. The etymology of küü is debated: Zieme suggests links to Chinese 氣 qì “energy” or Mongolian kü (power), while Geng proposes links to modern Kazakh kiyeli “holy” (Geng 2003, p. 438). The compound kälig äd[rä]mlik reinforces the supernatural aspect.

- D. U 3301

Recto (see Figure 7)

| 49 | 1 | [..................................] äsängülüg [.....]tar. |

| ///////////////////////////// ʾsʾnkwlwk ////tʾr,, | ||

| 50 | 2 | […………………………………………]ar. |

| /////////////////////////////////////////////////ʾr,, | ||

| 51 | 3 | [……………………………………]kal(a)r |

| ///////////////////////////////////////////////qʾ lr | ||

| 52 | 4 | [.................................................eti]glik[......]. |

| //////////////////////////////////////////klyk /////,, | ||

| 53 | 5 | [...............................................k ye]mišlik. |

| ///////////////////////////////////////q ///mys lyk,, | ||

| 54 | 6 | […………………………………] yıgl(a)r. |

| ////////////////////////////////////////// yyq lr,, |

Figure 7.

U 3301 Recto. © Depositum der BERLIN-BRANDENBURGISCHEN AKADEMIE DER WISSENSCHAFTEN in der STAATSBIBLIOTHEK ZU BERLIN—Preußischer Kulturbesitz Orientabteilung.

Verso: (see Figure 8)

| 55 | 1 | [...............................................] küvrügüg. |

| //////////////////////////////////// kwyvrwkwk,, | ||

| 56 | 2 | [………………………........oyu]nlarıg. |

| ///////////////////////////////////////////n lʾryq,, | ||

| 57 | 3 | [……………………mandarik] čäčäkl(ä)r. |

| //////////////////////////////////////////// cʾcʾk lr,, | ||

| 58 | 4 | [...................................................]lıg kuvrag üzä |

| //////////////////////////////////////lyq qwvrʾq ʾwyz ʾ | ||

| 59 | 5 | [...................................................] buzulmaz. |

| ///////////////////////////////////////// pwz wlmʾz,, | ||

| 60 | 6 | [……………………………………]rurl(a)r. |

| ///////////////////////////////////////////// rwr lr,, |

Figure 8.

U 3301 Verso. © Depositum der BERLIN-BRANDENBURGISCHEN AKADEMIE DER WISSENSCHAFTEN in der STAATSBIBLIOTHEK ZU BERLIN—Preußischer Kulturbesitz Orientabteilung.

我此土安隱,天人常充滿。園林諸堂閣,種種寶莊嚴。寶樹多花菓,眾生所遊樂。諸天撃天鼓,常作眾伎樂。雨曼陀羅花,散佛及大眾。我淨土不毀,而眾見燒盡。(T0262_.09.0043c07-12)

Translation of the Old Uyghur text:

(49–54) [……] peaceful […], [……] adornments, [……] fruits […]

(55–60) [……] drums, [……] music, […… mandārava] flowers, upon [……] assembly, [……] will not be destroyed, [……].

Commentary:

[mandarik] čäčäkl(ä)r (line 57) is the Old Uyghur translation of the Chinese 曼陀羅花 màntuóluóhuā “mandārava flowers”. Although the translation of 曼陀羅 màntuóluó is missing in the text, it can be reconstructed as mandarik, derived from Sanskrit mandāraka through typical phonetic adaptation patterns.

- E. U3314+U2422

Recto (see Figure 9)

| 61 | 1 | […......] yaragınča iz kal[…………………k…m…]likig. |

| /////////// yʾrʾq yncʾ ʾyz qʾl//////////////////k////m///lykyk,, | ||

| 62 | 2 | […] l[a]rka nomlayurm(ä)n adrok [adrok] noml(a)rıg. |

| /// l///r qʾ nwmlʾywr mn ʾʾdrwq ////////// nwm lryq,, | ||

| 63 | 3 | kün[i]ŋä üz (P) üksüz k(ä)nt[ü] özüm kılurm(ä)n bo köŋülüg. |

| kwyn///nkʾ ʾwyz (P) wkswz knt/// ʾwyz wm qylwr mn pw kwnkwlwk,, | ||

| 64 | 4 | nät[ä]gin (P) ärsär kılıp bo kamag tınl(ı)gl(a)r[ıg]. |

| nʾt///kyn (P) ʾrsʾr qylyp pw qʾmʾq tynlq lr///,, | ||

| 65 | 5 | bulturay[ı]n kigürgäli üzäliksiz bilgä biligkä. |

| pwltwrʾy///n kykwrkʾly ʾwz ʾlyksyz pylkʾ pylykkʾ,, | ||

| 66 | 6 | t(ä)rk tav[ra]k tükällig bolzunl(a)r burhanl(a)r ät’öziŋä. |

| trk tʾv///////q twykʾl lyk pwlz wn lr pwrqʾn lr ʾtʾwyz ynkʾ,, |

Figure 9.

U 3314 + U 2422 Recto. © Depositum der BERLIN-BRANDENBURGISCHEN AKADEMIE DER WISSENSCHAFTEN in der STAATSBIBLIOTHEK ZU BERLIN—Preußischer Kulturbesitz Orientabteilung.

Verso (see Figure 10)

| 67 | 0 | beš[in]č yüz iki y(i)g(i)rmi. |

| pys///c ywz ʾyky ykrmy,, | ||

| 68 | 1 | ol üdün kamag ulug terin kuvrag tükäl bilgä t(ä)ŋri t(ä)ŋri[si] |

| ʾwl ʾwydwn qʾmʾq ʾwlwq tyryn qwvrʾq twykʾl pylkʾ tnkry tnkry//// | ||

| 69 | 2 | burhan k(ä)ntüning sansız sakıšsız näčä näčä asanke |

| pwrqʾn kntw nynk sʾnsyz sʾqyssyz nʾcʾ nʾcʾ ʾsʾnky | ||

| 70 | 3 | k(a)lp sakıšı (P) üzäki aŋsız uzun ülgüsüz kolusuz |

| klp sʾqysy (P) ʾwyz ʾky ʾʾnksyz ʾwz wn ʾwylkwswz qwlwswz | ||

| 71 | 4 | özin yaš (P) ın uzunın ırakın nomlayu y(a)rlıkamıšın |

| ʾwyz yn yʾs (P) yn ʾwz wnyn ʾyrʾqyn nwmlʾyw yrlyqʾmysyn | ||

| 72 | 5 | [äši]dip ülgülänčsiz täŋlänčsi[z asank]e tınl(ı)gl(a)r ulug asıgıg |

| /////dyp ʾwylkwlʾncsyz tʾnklʾncsy////////y tynlq lr ʾwlwq ʾʾsyq yq | ||

| 73 | 6 | [bul]tıl(a)r. ol üdün atı [kötrülmiš t]özün maitre bodis(a)t(a)[v] |

| /////ty lr,, ʾwl ʾwydwn ʾʾty ///////////wyz wn mʾytry pwdyst///// |

Figure 10.

U 3314 + U 2422 Verso. © Depositum der BERLIN-BRANDENBURGISCHEN AKADEMIE DER WISSENSCHAFTEN in der STAATSBIBLIOTHEK ZU BERLIN—Preußischer Kulturbesitz Orientabteilung.

隨所應可度,為說種種法。每自作是意,以何令眾生。得入無上慧,速成就佛身。妙法蓮華經分別功德品第十七

爾時大會,聞佛說壽命劫數長遠如是,無量無邊阿僧祇眾生得大饒益。于時世尊告彌勒菩薩(T0262_.09.0044a02-08)

Translation of the Old Uyghur text:

(61–66) according to […] trace […]. I expound various kinds of Dharmas to these [……]. Every day, I continuously think to myself: How can I make these beings achieve super wisdom and quickly attain the Buddha-body?

(67) fifth, one hundred and twelve

(68–73) At that time, the great assembly [heard] the all-knowing, god of the gods, Buddha expound how his lifespan extends for such a long, immeasurable time, through these incalculable and immeasurable kalpas, and the immeasurable, uncountable, and [innumerable] beings [received] great benefits. At that time, the world-[honored] noble Maitreya Bodhisattva…

Commentary:

asanke k(a)lp (line 69–70) is the Old Uyghur translation of the Chinese 阿僧祇劫 āsēngqí jié “incalculable eons”. The term asanke represents “innumerable” or “an extremely large number” in Indian numerical systems, derived through Tocharian A asaṃkhe or Sogdian ʾʾsʾnky from Sanskrit asaṃkhyeya (Wilkens 2021, p. 71). k(a)lp refers to cosmic periods, derived through Tocharian A kalp or Sogdian klp ~ krp ~ krph ~ kδph from Sanskrit kalpa (Wilkens 2021, p. 324). This phrase expresses an immeasurable temporal duration.

[asank]e tınl(ı)gl(a)r (line 72) is the Old Uyghur translation of the Chinese 阿僧祇眾生 āsēngqí zhòngshēng. Although the part where [asank]e was written is missing, we can restore it based on the context and the final letter, y.

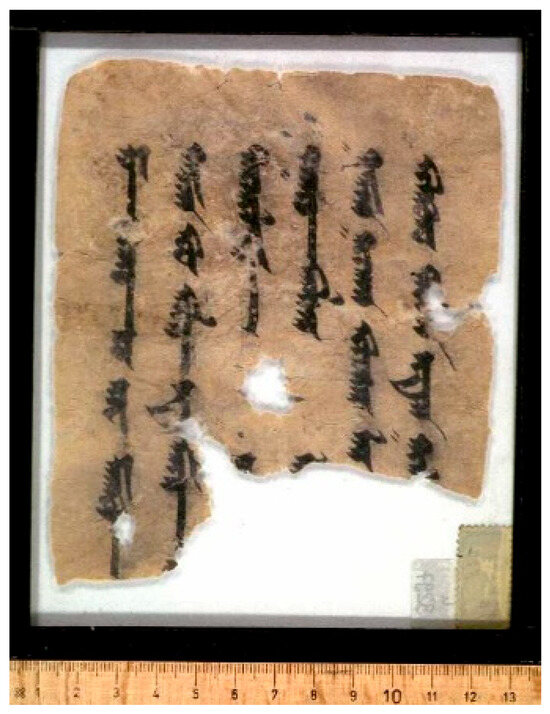

- F. Mainz 261

- Recto (see Figure 11)

| 74 | 1 | bod[is(a)t(a)v]l(a)r m(a)has(a)t(a)vl(a)r udačı boltıl(a)r. ävrilinčziz nom tilg[änin] |

| pwd//////////lr mqʾstv lr ʾwdʾcy pwldy lr ,, ʾvrylyncsyz nwm tylk///// | ||

| 75 | 2 | ävirgä[li]. yana bar ärti[l](ä)r. ortun miŋ yertinčü p(a)r(a)manul[a]rı |

| ʾvyrkʾ//// ,, yʾnʾ pʾr ʾrty ///r ,, ʾwrtwn mynk yyrtyncw prmʾnw l///ry | ||

| 76 | 3 | sanınča (P) [bo]dis(a)[t](a)vl(a)r m(a)has(a)t(a)vl(a)r udačı boltıl(a)r. |

| sʾnyncʾ (P) ///dys///v lr mqʾstv lr ʾwdʾcy pwlty lr ,, | ||

| 77 | 4 | arıg süzük (P) nom tilg[ä]nin ävirgäli. yana ymä bar |

| ʾʾryq swyz wk (P) nwm tylk///nyn ʾvyrkʾly ,, yʾnʾ ymʾ pʾr | ||

| 78 | 5 | ärtil(ä)r. kičik [miŋ] yertin[čüniŋ] p(a)r(a)manul(a)rı [san]ınča bodis[(a)t(a)v] |

| ʾrdy lr ,, kycyk////// yyrtyn/////k prmʾnw lry ////yncʾ pwdys//////////////////// | ||

| 79 | 6 | l(a)r m(a)has(a)t(a)vl(a)r [säkiz] t[ugum]ta tüzgärinčsiz yeg tüzü kö[ni] |

| lr mqʾstv lr //////////////////t///////////m tʾ twyz kʾryncsyz yyk twyz w kwy/// |

Figure 11.

Mainz 261 Recto. © Depositum der BERLIN-BRANDENBURGISCHEN AKADEMIE DER WISSENSCHAFTEN in der STAATSBIBLIOTHEK ZU BERLIN—Preußischer Kulturbesitz Orientabteilung.

Verso (see Figure 12)

| 80 | 1 | tuymak atl(ı)g ıd[o]k burhan kutın bulgalı täg[……..] bul[…...] |

| twymʾq ʾʾtlq ʾyd///q pwrqʾn qwtyn pwlqʾly tʾk///// pwl////// | ||

| 81 | 2 | yana ymä bar [är]til(ä)r. tört kata t[ört divip] |

| yʾnʾ ymʾ pʾr/////ty lr ,, twyrt qʾtʾ t////////////////// | ||

| 82 | 3 | yertinčü (P) niŋ p(a)r(a)manul(a)rı sanın[ča] bodis(a)t(a)vl(a)r m(a)has[(a)t(a)v] |

| yyrtyncw (P) nynk prmʾnw lry sʾnyn///// pwdystv lr mqʾs///// | ||

| 83 | 4 | l(a)r tört (P) tugumta burhan kutın bultačıl(a)r [yana] |

| lr twyrt (P) twqwm tʾ pwrqʾn qwtyn pwltʾcy lr ///////////// | ||

| 84 | 5 | ymä bar ärtil(ä)r üč kata tö[rt] divip yerti[nčüniŋ] |

| ymʾ pʾr ʾrdy lr ,, ʾwyc qʾtʾ twy///// dyvyp yyrty//////////////// | ||

| 85 | 6 | p(a)r[(a)manu]l(a)rı sanınča bodis(a)t(a)vl(a)r m(a)has(a)t(a)vl(a)r […]li üč |

| pr//////////////////lry sʾnyncʾ pwdystv lr mqʾstv lr /////ly ʾwyc |

Figure 12.

Mainz 261 Verso. © Depositum der BERLIN-BRANDENBURGISCHEN AKADEMIE DER WISSENSCHAFTEN in der STAATSBIBLIOTHEK ZU BERLIN—Preußischer Kulturbesitz Orientabteilung.

菩薩摩訶薩,能轉不退法輪;復有二千中國土微塵數菩薩摩訶薩,能轉清淨法輪;復有小千國土微塵數菩薩摩訶薩,八生當得阿耨多羅三藐三菩提;復有四四天下微塵數菩薩摩訶薩,四生當得阿耨多羅三藐三菩提;復有三四天下微塵數菩薩摩訶薩,三生當得阿耨多羅三藐三菩提;復有二四天下微塵數菩薩摩訶薩,二生當得阿耨多羅三藐三菩提;復有一四天下微塵數菩薩摩訶薩,一生當得阿耨多羅三藐三菩提;復有八世界微塵數眾生,皆發阿耨多羅三藐三菩提心。(T0262_.09.0044a14-25)

Translation of the Old Uyghur text:

(74–81) Bodhisattva-mahāsattvas can turn the irreversible Dharma wheel. Moreover, there were Bodhisattva-mahāsattvas equal in number to the dust particles of a medium thousand-world, who will be able to turn the pure Dharma wheel. Moreover, there were Bodhisattva-mahāsattvas equal in number to the dust particles of a small thousand-world, who will attain the holy Buddhahood, which is called unfathomable, best, and perfect enlightenment, within eight lifetimes.

(82–85) There were Bodhisattva-mahāsattvas equal in number to the dust particles of four sets of four continents, who would attain Buddhahood within four lifetimes. Furthermore, there were Bodhisattva-mahāsattvas equal in number to the dust particles of the three sets of four continents who […] three […].

Commentary:

ävrilinčziz nom (line 74) is the Old Uyghur translation of the Chinese 不退法 bùtuìfǎ “irreversible Dharma”. The translation calques Chinese morphosyntax (ävrilinčziz = non-turning, nom = Dharma).

ortun miŋ yertinčü (line 75) is the Old Uyghur translation of the Chinese phrase 二千中國土 èrqiān zhōng guótǔ, which corresponds to the Sanskrit term madhyamakalokadhātu “medium thousand-world.” This translation demonstrates the complex, multilingual transmission of Buddhist cosmological terminology. Kumārajīva employed different translation strategies for the same Sanskrit Buddhist content depending on whether it appeared in prose or verse sections, rendering the concept of madhyamakalokadhātu as 二千中國土 èrqiān zhōng guótǔ in prose and 中千界 zhōngqiān jiè in verse (Huang 2018, p. 620). The Old Uyghur phrase ortun miŋ yertinčü precisely translates the Chinese versified form 中千界 zhōngqiān jiè rather than the prose equivalent 二千中國土èrqiān zhōng guótǔ. This pattern is also evident in line 78, where kičik [miŋ] yertin[čü] translates 小千国土 xiǎoqiān guótǔ, which appears as 小千界 xiǎoqiān jiè in the verse portions. These correspondences suggest that the Old Uyghur translator possessed not only intimate familiarity with Kumārajīva’s translation techniques but also likely had access to Sanskrit versions of the Lotus Sutra, enabling sophisticated cross-referencing between multiple textual traditions.

tüzgärinčsiz yeg tüzü kö[ni] tuymak atl(ı)g ıdok burhan kutı (line 79–80) is the Old Uyghur translation corresponding to Kumārajīva’s Chinese transliteration 阿耨多羅三藐三菩提 ānòuduōluó sānmiǎo sānpútí, which is from Sanskrit anuttarā-saṃyak-saṃbodhi “supreme perfect enlightenment.” The Sanskrit term anuttarā-saṃyak-saṃbodhi is also translated as 无上正等觉 wúshàng zhèngděng jué or 无上正等菩提 wúshàng zhèngděng pútí in different places in the Chinese Sutra (Huang 2018, p. 6). Here, the Old Uyghur tüzgärinčsiz yeg tüzü kö[ni] tuymak corresponds to the Chinese 无上正等觉 wúshàng zhèngděng jué. The Old Uyghur translator employed varying translation strategies for translating 阿耨多羅三藐三菩提 ānòuduōluó sānmiǎo sānpútí in this text. When it first appeared, the translator provided a complex full version tüzgärinčsiz yeg tüzü kö[ni] tuymak atl(ı)g ıdok burhan kutı (the holy Buddhahood called unfathomable, best, and perfect enlightenment), and when the same term appeared subsequently, the translator used the simplified version burhan kutı (Buddhahood) in line 83. This demonstrates the translator’s awareness of textual economy and stylistic variation while maintaining the doctrinal precision.

3. Source of Translation and Relationship Between Different Versions of the Text

3.1. Source of Translation

The Old Uyghur versions of the Lotus Sutra have a complex transmission history that reflects multiple phases of Central Asian Buddhist translation practices. While the majority of extant fragments demonstrate a clear dependence on textual sources transmitted in the Chinese language, particularly Kumārajīva’s authoritative 5th-century translation, emerging evidence suggests a stratified textual tradition involving both direct translation and cultural mediation.

The transmission pathways of these texts reveal considerable complexity, with several unresolved questions regarding the exact routes and intermediary languages involved. This complexity arises primarily from the diverse writing systems used in extant fragments. The majority of the Old Uyghur fragments of the Lotus Sutra are written in the Uyghur script, but three identified fragments are in the Sogdian script. This variation in the script has led to scholarly debates about the translation process and the possible existence of intermediary versions.

Some scholars, such as Maue and Röhrborn (1980) and J. Elverskog (1997), have proposed that the Uyghur translation may have been made in the 10th century from a Sogdian intermediary version of the Chinese text. This hypothesis is based on the presence of Sogdian loanwords and the influence of Sogdian grammatical structures in Uyghur fragments. However, no Sogdian version of the Lotus Sutra has been discovered to date, leaving this theory open to further investigation.

In addition to Old Uyghur and Sogdian script fragments, other manuscripts related to the Lotus Sutra are believed to have been created by the Old Uyghur people. For instance, P. Zieme (1991) studied a manuscript known as the Essenz-Śloka, which consists of 72 lines based on the second chapter of the Lotus Sutra. This manuscript provides valuable insights into the Uyghur interpretation and adaptation of texts.

Furthermore, A. Yakup (2011) identified a new fragment containing the name of the Lotus Sutra. However, it remains unclear whether this fragment represents a unique composition by the Old Uyghurs or is a translation of an unknown similar Chinese text. This uncertainty highlights the need for further research to clarify the relationship between these texts and their Chinese counterparts.

Additionally, Mirkamal and Raschmann (2022) examined Old Uyghur fragments (GT15-64) preserved in the National Library of China, Beijing, along with their parallel fragments (Ch/U 6005 + Ch/U 6411 + Ch/U 7287) from the Berlin Turfan collection, which represent different copies of the same text. This manuscript consists of two distinct parts: an adhyeṣaṇā verse that extols the merit of good deeds, emphasizing the immeasurable benefits of imploring the Buddha to turn the dharma wheel, and a colophon. While the adhyeṣaṇā section contains numerous quotations from the Lotus Sutra, the colophon reveals that this is an original literary work composed by Buddhist monks who praise the Lotus Sutra.

These findings demonstrate the creative adaptation of Buddhist literature by Old Uyghur religious communities, showing how they incorporated elements from multiple canonical sources while creating new devotional compositions centered on the Lotus Sutra. Since the topic of this study is the Lotus Sutra itself, we will focus on the actual sutras and reserve the analysis of these commentary texts for future studies.

Based on a systematic analysis of these textual variants and their distinctive characteristics, our research reveals two distinct translation traditions that can be differentiated through linguistic and chronological analyses.

3.2. Relationship Between Different Versions of the Texts and Their Characteristics

To examine the relationships between the different Uyghur versions and their Chinese sources. We employ a comparative textual analysis involving three key approaches:

Identifying and categorizing fragments: Systematically categorizing fragments based on scripts, linguistic features, and thematic content.

Comparative analysis: Uyghur texts are compared with their Chinese counterparts to identify similarities and differences in terminology, phrasing, and doctrinal emphasis.

Chronological analysis: Proposing a tentative timeline for the development of different Uyghur versions by analyzing the linguistic features and historical context.

This methodology reveals two distinct translation traditions with fundamentally different approaches and chronological developments:

Version I: Our analysis indicates that this version was likely formed before the 10th century and shows a clear influence from Sogdian intermediary sources and early Chinese Buddhist scriptures. The language of Version I is closer to Old Turkic and Manichaean texts and is characterized by free translation strategies, including omissions and paraphrasing. This version is represented by the most complete manuscript studied and published by Radloff in 1911, and Sogdian script texts like MIK III 195 and MIK III 199.

Version II: This version was likely popular from the 11th to the 14th centuries, reflecting the linguistic changes of the Uyghur Buddhist golden age. Version II shows the influence of later Sanskrit Buddhist texts and is associated with the spread of Mongolian Buddhism during the Yuan Dynasty. It demonstrates sophisticated translation techniques that balance fidelity to the source text with cultural adaptation, suggesting that the translators had a deep understanding of Buddhist doctrines and their cultural implications. This period also saw the emergence of new grammatical forms and the use of Tocharian loanwords, with more detailed annotations on the 33 manifestations of Avalokiteśvara. J. Oda (2008), which transcribes a fragment belonging to Version II, further supports the distinction between the two versions.

The following sections present concrete textual evidence demonstrating the characteristic features of each version.

3.2.1. Characteristics of Version I

Version I exhibits distinctive translation strategies, characterized by frequent omissions and paraphrasing, suggesting a reliance on intermediary traditions or incomplete comprehension. These characteristics are evident in fragments such as U3542, U2376, and 80BTI:527, and some texts that belong to Chapter 25. For instance, in 80BTI:527 verso, which corresponds to chapter 9 of the Lotus Sutra, we can find that there are lots of omissions compared with Kumārajīva’s translation:

[Chinese source] 爾時佛告阿難:「汝於來世當得作佛,號山海慧自在通王如來、應供、正遍知、明行足、善逝、世間解、無上士、調御丈夫、天人師、佛、世尊。當供養六十二億諸佛,護持法藏,然後得阿耨多羅三藐三菩提。教化二十千萬億恒河沙諸菩薩等,令成阿耨多羅三藐三菩提。國名常立勝幡,其土清淨,琉璃為地。劫名妙音遍滿。(T0262_.09.0029c03-11)

[Old Uyghur Text] (05) ötrü (06) äŋ ilki anant toyınka inčä t[e]p (07) y(a)rl(a)g y(a)rlıkadı. anant siz sans(a)z t[ümän] (08) ažun ta ken bo yertinčü yer suv d[akı............] (09) altmıš koti sanı burhanlarka t[apıg] (10) ın tapınıp tag ögüz täg b[ilgä biliglig] (11) ärkligin elänür atl(a)g[ ] burhanıg [...........] (12) bulursız. burhan kutın bulmıš[ ]t[a ötrü] (13) yana y(e)g(i)rmi miŋ tümän koti [sanı gaŋ] (14) ögüz ičintäki kum sanınča tınl[glar(a)g] (15) bodis(a)v(a)t ornınga tägürüp burhan [kutın] (16) orunantur g(a)ysız. ulušuŋuz turkaru y[eg?] (17) örüngü turgurur atl(a)g[….] bolgay. yeriŋiz (18) suvuŋuz ärtingü körtlä, vaiduri ärdini (19) [bol]mıš bolgay. [sizin]g üdüŋüz tözün [...................]tılar.(Zhang 2010)

Beyond the prevalent omissions and paraphrasing observed in prose sections, Version I’s approach to translating the metrical verse portions (gāthās) of the Lotus Sutra further exemplifies its methodology of free translation. This corpus of texts demonstrates that when translating verse sections, the translators appear to have directly rendered them into prose format without attempting to preserve the poetic structure, as seen in Version II texts, which strove to maintain rhythmic and metrical patterns wherever possible. This distinctive approach is clearly illustrated in the translation of Chapter 25 of the Lotus Sutra, which contains famous verses about Avalokiteśvara. The Chinese source presents these lines in a structured verse (form SI 3158 D/2):

| [Chinese source] | 爾時無盡意菩薩以偈問曰: |

| 世尊妙相具,我今重問彼, | |

| 佛子何因緣,名為觀世音? | |

| 具足妙相尊,偈答無盡意。 | |

| (T0262_.09.0057c07-11) |

[Old Uyghur Text] (171) alkınčsız kögüz[lüg] bodis(a)v(a)t šlok takšutın t(ä)ŋri burhan (172) ka inčä tep ayıtu täginti [...] sokančıg körkiŋä tükällig (173) im t(ä)ŋrim [...] ekiläyü ayıtu täginür män bo bodis(a)v(a)t [...] nä (174) üčün nä tıltagın kuanšiim pusar tep atantı [...] t(ä)ŋri (175) burhan ymä šlok takšutın inčä tep [...] kekinč yarlıkadı.(Özcan 2020)

The Uyghur translation renders these verses as a continuous prose narrative, completely abandoning the metrical structure of the original. While the translator acknowledges the verse format through the phrase “šlok takšutın” (from the śloka), the actual translation proceeds in prose form, prioritizing semantic content over poetic form. This approach contrasts sharply with Version II’s sophisticated attempts to recreate rhythmic patterns and maintain poetic structure in the target language, suggesting that Version I translators either lacked the technical skill to reproduce verse forms or deliberately chose a more accessible prose rendering for their intended audience.

3.2.2. Characteristics of Version II

Version II demonstrates unparalleled adherence to Kumārajīva’s Chinese text, exhibiting near-verbatim correspondence in lexical choices and syntactic structures. For instance, in Mainz 366 recto, line 1, which belongs to chapter 15 of the Lotus Sutra, the Old Uyghur phrase inčip ötrü ulug üč y(a)vlak yolta tüškäy translates the Chinese 即當墮惡道 jí dāngduò èdào. The Uyghur rendering of Chinese 惡道 èdào as üč yavlak yol (three evil paths) reveals not only lexical precision but also doctrinal integration, explicitly incorporating the Mahāyāna concept of triduḥkha, which is absent in the source text.

Additionally, there are free alternations between t and d, which is one of the characteristics of late texts (Erdal 2004, p. 18). For instance, ärti is written as ʾrdy or ʾrty ( Mainz 261, recto lines 2, 5, verso lines 2, 5). boltı is written as pwldy or pwlty (in Mainz 261, recto, lines 1 and 3).

Moreover, in Version II, we can also observe that the translator attempted to adopt traditional Old Uyghur poetic forms characterized by alternating alliteration or end rhyme. For instance, in U3314+U2422, which we discussed above, the translator tried to end each line with the same syllable ending, creating a consistent rhythmic pattern throughout the text. For instance, the following example illustrates this technique (rhymed elements are marked with underline):

- […......] yaragınča iz kal[…………………….]likig.

- […]l(a)rka nomlayurm(ä)n adrok [adrok] noml(a)rıg.

- kün[i]ŋä üzüksiz k(ä)nt[ü] özüm kılurm(ä)n bo köŋülüg.

- nät[ä]gin ärsär kılıp bo kamag tınl(ı)gl(a)r[ıg].

- bulturay[ı]n kigürgäli üzäliksiz bilgä biligkä.

- t(ä)rk tav[ra]k tükällig bolzunl(a)r burhanl(a)r ät’öziŋä.

3.2.3. Terminological Evolution

The two versions also display distinct terminological preferences that reflect their different historical contexts. In Version I, the term corresponding to the popular Chinese Buddhist expression 世尊 shìzūn appears as ulušta ulugı-ya (in U2376 recto line 3 and TM 257a line 3), and täŋri burhan is used in a mixed way to translate both 世尊shìzūn and 佛fó (in 80bti:527 recto lines 3–4, verso lines 10–11; SI 3158 D/2, lines 97, 213). In Version II, the term became standardized as atı kötrülmiš, with burhan exclusively used to translate the Chinese character 佛 fó (in U3169 recto lines 1, 4; verso lines 4, 6; U3549+2377+U3300a recto line 2; U2760 [=U2274] verso line 3), thus clearly separating their usage.

Additionally, the numerical translations showed progressive standardization from Version I to Version II, becoming increasingly accurate and consistent. For example, the Old Uyghur phrase corresponding to the Chinese Buddhist term 六十二亿 liùshíèryì appeared as “altmıš koti sanı” (in 80bti:527 recto line 9), omitting the number two, and as “altmıš iki koti sanı” (in SI 3158 D/2, line 84) following the Chinese number order. However, in Version II, the translation of this number appears as iki yetmiš kolti sanı (in SI 1470 Kr. II 11/1, recto line 6), which follows the standard numbering conventions of the Old Uyghur language.

These systematic differences between the two versions provide clear evidence of the chronological development and evolving translation methodologies in Old Uyghur Buddhist literature. By comparing all available Old Uyghur texts of the Lotus Sutra and using the above classification principles, we can initially categorize all extant Old Uyghur Lotus Sutra texts as follows (see Table 1):

Table 1.

Old Uyghur fragments of the Lotus Sutra.

4. Conclusions

This study provides a detailed edition and analysis of Old Uyghur fragments from chapters 3–5 and 16–17 of the Lotus Sutra preserved in the Berlin Turfan Collection. Using a systematic comparative analysis, this research identifies two distinct types of Old Uyghur Lotus Sutra translations, each with different linguistic features and translation strategies.

Version I, likely from before the 10th century, shows closer links to Old Turkic and possibly Sogdian intermediary sources, with frequent omissions and paraphrasing compared to the original Chinese text. Version II, common from the 11th to 14th centuries, aligns more closely with Kumārajīva’s Chinese translation, using standardized terminology and more consistent translation methods.

This study also documents the linguistic and cultural contacts between the Sogdians and the Old Uyghurs through textual analysis, contributing to our understanding of Buddhist text transmission in medieval Central Asia. These findings advance our knowledge of Uyghur Buddhist literature and provide valuable insights into the multilingual and multicultural nature of Buddhist textual practices on the Silk Road.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Buswell, Robert E., Jr., and Donald S. Lopez, Jr. 2014. The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Yibiao 陈一标. 2021. Dasheng zhuangyan jinglun hanyi zuo ‘xiang’ de lakṣana he nimitta de yanjiu—yi sanxing shuo he huanyu wei zhongxin [《大乘庄严经论》汉译作「相」的lakṣana和nimitta的研究——以三性说和幻喻为中心] (A study of the meaning of lakṣana and nimitta translated into the Chinese character ‘xiang’ (相) in Mahāyānasūtrālaṃkāra—based on the theory of Three Natures and the metaphor of phantom). Zheng Guan Zazhi = Satyabhisamaya: A Buddhist Studies Quarterly [正觀雜誌] 99: 5–62. [Google Scholar]

- Clauson, Sir Gerard. 1972. An Etymological Dictionary of Pre-Thirteenth-Century Turkish. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Elverskog, Johan. 1997. Uygur Buddhist Literature. Silk Road Studies I. Turnhout: Brepols. [Google Scholar]

- Erdal, Marcel. 2004. A Grammar of Old Turkic. Handbook of Oriental Studies. Section 8: Uralic & Central Asian Studies 3. Leiden and Boston: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Fedakâr, Durdu. 1991. Das Alttürkische in sogdischer Schrift. Textmaterial und Orthographie (Teil I). UAJb N.F. 10: 85–98. [Google Scholar]

- Fedakâr, Durdu. 1994. Das Alttürkische in sogdischer Schrift. Textmaterial und Orthographie (Teil II). UAJb N.F. 13: 133–157. [Google Scholar]

- Fedakâr, Durdu. 1996. Das Alttürkische in sogdischer Schrift. Textmaterial und Orthographie (Teil III). UAJb N.F. 14: 187–205. [Google Scholar]

- Geng, Shimin 耿世民. 2003. Weiwu’er Gudai Wenxian Yanjiu [维吾尔古代文献研究] (Research on Ancient Uyghur Literature). Beijing: Zhongyang Minzu Daxue Chubanshe [中央民族大学出版社]. [Google Scholar]

- Haneda, Toru 羽田亨. 1915. Uiguru-go Hokke-kyō Fumon-hin danpen [ウイグル語法華経普門品断片] (Fragment of the Samantamukha Chapter of the Uyghur Saddharmapuṇḍarīka-sūtra). In Haneda Hakushi Shigaku Ronbunshū [羽田博士史学論文集]. Kyoto: Dōhōsha Shuppanbu [同朋舎出版部], pp. 143–47. [Google Scholar]

- Hazai, György. 1970. Ein buddhistisches Gedicht aus der Berliner Turfan-Sammlung. Acta Orientalia Hungarica 23: 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Baosheng 黄宝生. 2018. Fanhan duikan Miaofa Lianhua Jing [梵汉对勘妙法莲华经] (Sanskrit-Chinese Comparative Lotus Sutra). In Fanhan Fojing Duikan Congshu [梵汉佛经对勘丛书]. Beijing: Zhongguo Shehui Kexue Chubanshe [中国社会科学出版社]. ISBN 978-7-5203-1304-9. [Google Scholar]

- Maue, Dieter, and Klaus Röhrborn. 1980. Zur alttürkischen Version des Saddharmapuṇḍarīka-Sutra. Central Asiatic Journal 24: 251–73. [Google Scholar]

- Mirkamal, Aydar, and Simone-Christiane Raschmann. 2022. Turning the Wheel of Dharma: Adhyesana Fragments in Old Uighur Referring to the Saddharmapundarkasutra and the Suvarpaprabhasasutra. Acta Orientalia Hungarica 75: 231–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, Friedrich Wilhelm Karl. 1910. Uigurica II. Abhandlungen der Königlich Preußischen Akademie der Wissenschaften. Philosophisch-historische Klasse, Nr. 3. Berlin: Königlich Preußische Akademie der Wissenschaften, [Reprint in: Sprachwissenschaftliche Ergebnisse der deutschen Turfan-Forschungen (SEDTF) 1: 61–168]. [Google Scholar]

- Oda, Juten 小田壽典. 1991. Toruko-go ‘Kan′non-kyō’ shahon no kenkyū-tsuihen kyūshō ‘Sobun chinzō’ shahon danpen shikichū [トルコ語「観音経」写本の研究 付編旧称「素文珍蔵」写本断片識注] (Some Remarks on the Turkish Quan-shi-im Sūtra with an Appendix on a Fragment formerly called Su-wen zhengcang). Seinan Ajia Kenkyū [西南アジア研究] 34: 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Oda, Juten 小田壽典. 1996. A Fragment of the Uyghur Avalokitesvara-Sutra with Notes. In Turfan, Khotan und Dunhuang. Vorträge der Tagung “Annemarie v. Gabain und die Turfanforschung”, veranstaltet von der Berlin-Brandenburgischen Akademie der Wissenschaften in Berlin (9–12. 1994). Edited by R. E. Emmerick, W. Sundermann, I. Warnke and P. Zieme. Berlin: Akademie Verlag, pp. 229–43. [Google Scholar]

- Oda, Juten 小田壽典. 2000. Toruko-go bukkyō shahon ni kansuru nendai-ron: Hachiyō-kyō to Kan′non-kyō [トルコ語佛教寫本に關する年代論:八陽經と觀音經] (The Chronology of the Sakiz yukmak yaruq and the Quan-si-im pusar Sūtras). Tōyōshi Kenkyū [東洋史研究] 59: 114–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oda, Juten 小田壽典. 2008. Toruko-go ‘Kan’non-kyō’ shahon no kenkyū zokuhen-Quan-si-im pusar to Quan-si-im bodistv [トルコ語『観音経』写本の研究続編--Quansi-im pusarとQuansi-im bodistv] (A Supplemental Study of the Buddhist Sūtra Called Kuan-si-im pusar or Kuan-si-im bodistv in Old Turkic). Seinan Ajia Kenkyū [西南アジア研究] 68: 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özcan, Devrez. 2020. Eski Uygurca Kuanşi im Pusar incelemesi. Metin-çeviri-açıklamalar-sözlük. Ankara: Türk Dili Kurumu Yayınları. [Google Scholar]

- Özertural, Zekine. 2012. Alttürkische Handschriften. Teil 16: Mahāyāna-Sūtras und Kommentartexte. VOHD 13,24. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Özertural, Zekine. 2021. Alttürkische Handschriften. Teil 4: Varia Buddhica: Buddhistische Gedichte und Kleinere Sūtra-Texte. VOHD 13,12. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff, W. 1911. Kuan-si-im Pusar. Eine türkische Übersetzung des XXV. Kapitels der Chinesischen Ausgabe des Saddharmapundarika. St.-Pétersbourg: Bibliotheca Buddhica XIV. [Google Scholar]

- Shōgaito, Masahiro 庄垣内正弘. 1988. Drei zum Avalokitesvarasutra passende Avadanas. In Der türkische Buddhismus in der Japanischen Forschung. Edited by J. P. Laut and K. Röhrborn. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, pp. 59–73. [Google Scholar]

- Tachibana, Zuicho 橘瑞超. 1913. Hokke-kyō Daibadatta-hon [法華経提婆達多品] (The Devadatta Chapter of the Saddharmapuṇḍarīka-sūtra). In Ni-raku sōsho [二楽叢書] 4. Zuicho Tachibana: Motoyama-mura (Hyōgo-ken). [Google Scholar]

- Tekin, Şinasi. 1960. Uygurca Metinler I- Kuanşi İm Pusar (Ses İşiten İlah) Vap hua ki atlıg nom çeçeki sudur (saddharmapuṇḍarika-sūtra). Erzurum: Atatürk Üniversitesi Yayınları Araştırmaları Serisi Edebiyat Filoloji 2. [Google Scholar]

- Uzunkaya, Uğur. 2023. Eski Uygurca Saddharmapuṇḍarīka-Sūtra’ya ilişkin fragmanlar. Selçuk Türkiyat 57: 371–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzunkaya, Uğur. 2024. Saddharmapuṇḍarīka-sūtra’nın XXV: Bölümüne Dair Eski Uygurca Fragmanlar. Türk Dilleri Araştırmaları 34: 243–64. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkens, Jens. 2021. Handwörterbuch des Altuigurischen. Eski Uygurcanın El Sözlüğü. Altuigurisch-Deutsch-Türkisch. Eski Uygurca-Almanca-Türkçe. Edited by Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Göttingen. Göttingen: Universitätsverlag Göttingen. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakup, Abdurishid. 2011. An Old Uyghur Fragment of the Lotus Sutra from the Krotkov Collection in St. Petersburg. Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 64: 411–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakup, Abdurishid. 2021. Buddhāvataṃsaka literature in Old Uyghur. (Berliner Turfantexte XLIV). Turnhout: Brepols, 506p + 26 Plates. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Tieshan 张铁山. 1990. Huihuwen ‘Miaofa Lianhua Jing Pumen Pin’ jiaokang yu yanjiu [回鹘文《妙法莲华经·普门品》校勘与研究] (Collation and Research on the Uyghur ‘Lotus Sutra: Universal Gate Chapter’). Kashi Shifan Xueyuan Xuebao [喀什师范学院学报] 3: 13. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Tieshan 张铁山. 2010. Tulufan Baizikeli ke chutu Huihuwen “Miaofa Lianhua Jing” canye yanjiu [吐鲁番柏孜克里克出土回鹘文《妙法莲花经》残叶研究] (Research on Uyghur “Lotus Sutra” Fragment Leaves Excavated from Bezeklik, Turpan). In Shouijie Zhongguo Shaoshu Minzu Guji Wenxian Guoji Xueshu Yantaohui Lunwenji [首届中国少数民族古籍文献国际学术研讨会论文集] (Proceedings of the First International Academic Symposium on Ancient Books and Documents of Chinese Ethnic Minorities). Edited by Zhongyang Minzu Daxue, Beijing Shi Minzu Shiwu Weiyuanhui, Xinan Minzu Daxue and Zhongguo Minzu Guwenzi Yanjiuhui. Beijing: Zhongyang Minzu Daxue Zhongguo Shaoshu Minzu Yuyan Yanjiusuo, pp. 361–70. [Google Scholar]

- Zieme, Peter. 1985. Buddhistische Stabreimdichtungen der Uiguren. Berliner Turfantexte XIII. Berlin: Akademie Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Zieme, Peter. 1989. Zwei neue alttürkische Saddharmapuṇḍarīka-Fragmente. Altorientalische Forschungen 16: 370–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zieme, Peter. 1991. Der Essenz-Śloka des Saddharmapuṇḍarīka-Sūtras. In Varia Eurasiatica. Festschrift für Professor András Róna-Tas. Szeged: József Attila University, pp. 249–69. [Google Scholar]

- Zieme, Peter. 1998. The Conversion of King Subhavyuha: Further Fragments of an Old Turkish Version of the Saddharmapundarika. In Surya-candraya: Essays in Honour of Akira Yuyama on the Occasion of His 65th Birthday. Edited by Paul Harrison and Gregory Schopen. Swisttal: Indica et Tibetica, Volume 35, pp. 257–65. [Google Scholar]

- Zieme, Peter. 2000. Der Bodhisattva Gadgadasvara: Ein alttürkisches Fragment aus dem XXIV. Kapitel des Saddharmapundarikasutra. In Vostok. Istorija i Kul’tura. Professoru Yu. A. Petrosjanu k 70-letiju So Dnja Rozdenija. The East. History and Culture. To Professor Yu. A Petrosyan on the Occasion of His 70th Birthday. Sankt-Peterburg: Peterburgskoe Vostokovedenie, pp. 271–86. [Google Scholar]

- Zieme, Peter. 2005. Uyghur Versions of the Lotus Sutra with Special Reference to Avalokitesvara’s Transformation Bodies. Kyoto: Publikation im Internet. Available online: https://www.bun.kyoto-u.ac.jp/archive/jp/projects/projects_completed/hmn/eurasia/newsletter/13.pdf (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Zieme, Peter. 2025. Divisions and Chapter Titles of the Lotus Sūtra in Central Asia. In Bugu-Bujin-Buzhong-Buxi zhi xue: Jinian Chen Yinke xiyu yu Fojiao yuwen xue yanjiu wenji [不古不今不中不西之学:纪念陈寅恪西域与佛教语文学研究文集] (Neither Ancient nor Modern, Neither Chinese nor Western Learning: A Collection of Essays on Western Regions and Buddhist Philological Studies in Memory of Chen Yinke). Edited by Shen Weirong 沈卫荣 and Hou Haoran 侯浩然. Shanghai: Shanghai Century Publishing Group. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).