Abstract

Alongside historical narratives, there exists, in Old Kalmyk literature, a lesser-known corpus of travel writing that documents pilgrimages to major religious and political centers such as China, Tibet, and Mongolia. One notable and extant example of this genre is the travel account of Baaza Menkedjuev, a Gelung from the Maloderbetovskiy Ulus, more widely known as Baaza Bagshi. His first-person narrative was translated into Russian by A. M. Pozdneev in 1897 under the name “Skazanie o khozhdenii v Tibetskuiu stranu malo-dörbötskago Baaza Bagshi” [Narrative of the travel to Tibet by the Maloderbet Baaza Bagshi] and offers valuable ethnographic insights into a Kalmyk pilgrim’s journey to Tibet in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Until recently, scholarship on Baaza Bagshi’s Tibetan sojourn has been confined to his own account, with no corroborating evidence found in Tibetan-language sources. This study addresses that lacuna by examining references to Baaza Bagshi in the Tibetan-language biography (Tib. rnam thar) of the 13th Dalai Lama, Thubten Gyatso (Tib. thub bstan rgya mtsho, 1876–1933). The significance of these references lies not only in the information provided about the number of audiences with the Dalai Lama Baaza Bagshi received, the dates of his visits, and the content of their meetings, but also in the fact that they demonstrate how the Kalmyks—despite living in the European part of Russia, the furthest from the Mongolian Buddhist world—did not lose their religious ties with Tibet. The corroboration of Baaza Bagshi’s visit in both Kalmyk and Tibetan sources allows for a more integrated understanding of Kalmyk–Tibetan relations and contributes to the study of interregional Buddhist networks. Methods of historical contextualization, historiographical critique, and comparative source analysis were used for this research.

1. Introduction

The Kalmyks are a Mongolian people of the Oirat group. Being descendants of the Oirat tribes that migrated in the late 16th–early 17th centuries from Central Asia to the Lower Volga and the Northern Caspian region of Russia, they are the only people in Europe whose main religion is Tibetan Buddhism. They predominantly follow the Gelugpa school of Tibetan Buddhism. Strong religious and cultural ties connected the Kalmyks with the Tibetan Dalai Lamas.

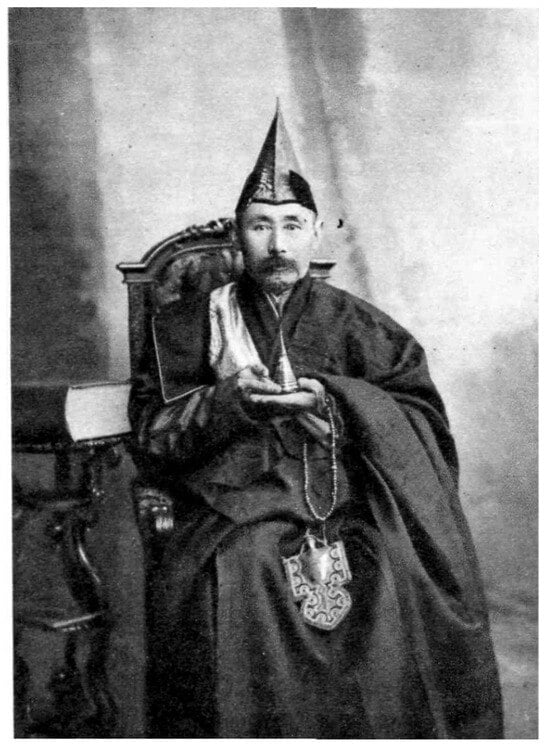

This article investigates the transregional pilgrimage of Baaza Menkedjuev (Figure 1)—better known as Baaza Bagshi1—a Gelung2 from the Maloderbetov Ulus3, by examining both Kalmyk and Tibetan sources. His travelog, Skazanie o khozhdenii v Tibetskuiu stranu malo-dörbötskago Baaza Bagshi [Narrative of the Travel to Tibet by the Maloderbet Baaza Bagshi], translated into Russian by A. M. Pozdneev in 1897, is one of the earliest Kalmyk-language travel accounts documenting a Buddhist pilgrimage to Tibet. Until recently, this narrative stood alone, with no confirmation from Tibetan-language sources. This study addresses that gap by identifying references to Baaza Bagshi in the Tibetan-language biography (rnam thar) of the 13th Dalai Lama, Thubten Gyatso (1876–1933), composed by Phurchok Thubten Jampa Tshultrim Tendzin.

Figure 1.

Baaza Menkedjuev. Photo from G. J. Ramstedt. Seven Journeys Eastward, 1898–1912: Among the Cheremis, Kalmyks, Mongols, and in Turkestan, and to Afghanistan.

The research presented here is guided by three questions: What do Tibetan sources reveal about Baaza Bagshi’s visit to Tibet? How do the Tibetan and Kalmyk narratives compare in their portrayals of this journey? And what broader insights can be drawn about Kalmyk–Tibetan relations and Buddhist diplomacy at the turn of the 20th century?

Drawing on Pozdneev’s Russian translation of Baaza Bagshi’s travelog, archival Kalmyk materials, and the Tibetan biography of the Dalai Lama, the article offers a comparative analysis of these accounts. The first section introduces Baaza Bagshi’s background and situates his journey within the context of Kalmyk Buddhism. The second section analyzes the travelog itself, while the third examines corroborating passages in the Dalai Lama’s biography. A final section compares the two narratives, highlighting omissions, discrepancies, and possible motivations. Through this source-critical approach, the article contributes to the study of interregional Buddhist networks and re-centers Kalmyk agency in the religious history of Inner Asia.

Baaza Menkedjuev was born in 1846 in Maloderbetovskiy Ulus, into a Kalmyk family affiliated with the Dundu Khurul4 aimak5. As the eldest son in a large household—his father fathered ten children from two wives—Baaza came from a lineage that, while lacking formal aristocratic titles such as zaisang or noyon6, nonetheless held considerable religious prestige within the region. His family’s prominence was rooted not in political authority, but in clerical distinction, particularly through their longstanding involvement with the Dundu Khurul monastery (Bembeev 2013, p. 9).

The Menkedjuev household enjoyed widespread respect among the Maloderbetovsky Kalmyks and beyond, due in large part to the spiritual and scholarly accomplishments of Baaza’s forebears. His grandfather, Djaltsan Bagshi, had served as an esteemed abbot of the Dundu Khurul monastery, establishing a lineage of clerical leadership. Likewise, Baaza’s uncle, Balchir Bagshi, gained a reputation for exceptional erudition; his exegeses and teachings attracted khuvaraks (monks or clergy) from neighboring uluses, underscoring his status as a regional authority in Buddhist doctrine. (Ibid.)

Dundu Khurul itself functioned not only as a religious center but also as a cultural and artistic hub. It was particularly renowned as a focal point for the zurachi (painters)—a tradition of Kalmyk religious artistry. The monastery’s altars were famously adorned with painted wooden tables, known in the Kalmyk language as shirya, exemplifying the synthesis of religious function and visual devotion that characterized this important monastic institution. (Ibid.)

From the “List of Khuruls in the northern part of the Maloderbetovsky Ulus”, we know that, beginning from 23 October 1879, he held the spiritual rank of manji.7 Thus, at the age of seven, Baaza Menkedjuev was formally introduced to monastic life at the Dundu Khurul monastery. There, he began his religious education, rapidly advancing in his studies. His training was not limited to scholasticism; in his youth, Baaza also undertook specialized instruction in Tibetan medicine, studying under the renowned emchi (physician) Jamtso Gelung. This engagement with medical knowledge—rooted in canonical texts and empirical practice—was a common complement to religious education among higher-ranking clergy, especially those expected to serve both spiritual and therapeutic roles in their communities.

Family ties allowed Baaza to use the treasures of the Dundu Khurul library, and he eagerly read all the works preserved in Tibetan and Kalmyk languages stored in it: historical records, letters, and so on. It was here that he became familiar with materials attesting to the long-standing connection between the Kalmyks and Tibet. In the preface to the “Skazanie o khozhdenii v Tibetskuiu stranu malo-dörbötskago Baaza Bagshi” [Narrative of the travel to Tibet by the Maloderbet Baaza Bagshi], Baaza Bagshi recounts that among the written historical monuments kept in the Dund Khurul was a charter from the Dalai Lama, issued to the Kalmyks during the embassy of Galdan Tseren in 1756 (Pozdneev 1897, p. VI). In fact, this charter was issued to the envoy of the Derbet8 noyon Galdan Tseren9—Tabka Getsul—who visited Tibet as part of the Kalmyk embassy sent by Khan Donduk Dashi to the 7th Dalai Lama, Kelsang Gyatso (Tib. bskal bzang rgya mtsho; 1708–1757) in 175610. From that moment onward, the aspiration to undertake a pilgrimage to the sacred sites of Tibet and to offer reverence before the Dalai Lama became a persistent and deeply internalized spiritual objective. The vision of such a journey increasingly occupied Baaza’s thought, shaping both his religious imagination and future ambitions.

In the List of Khuruls in the northern part of the Maloderbetovsky Ulus, Baaza Bagshi is named Baaza/Badma/Menkedzhenov, the senior Bagshi of the 1st Greater Sangak Chonkhorling Khurul, who was 52 years old in 1898. By the decree dated 4 April 1895 (outgoing charter No. 2411), he was officially confirmed in the rank of senior Bagshi of Dundu Khurul.

This entry provides the Tibetan name of the Khurul in which Baaza Bagshi served—Sangak Chonkhorling (Tib. gsang sngags chos ‘khor gling). From the preface to the Russian translation of his Narrative of the Journey to the Tibetan Country, we learn that Baaza Bagshi’s monastic name was Lobsang Sharab12 (Tib. blo bzang shes rab). This information has enabled the identification of references to Baaza Bagshi in the biography of the Dalai Lama.

Baaza Bagshi realized his lifelong dream—a pilgrimage to the distant and little-known land of Tibet—in July 1891, accompanied by his companions: Manji Liji Iderunov and the Kalmyk layman Dorji Ulanov. Substantial material and financial support for this demanding journey was provided by the ruling noyon of the Maloderbetovsky ulus, Tseren-David Tundutov, who not only subsidized the expedition but also organized an elaborate send-off and later a celebratory reception upon their return. The travelers spent more than two years on the road, facing numerous hardships, including “atmospheric influence” or “blood congestion disease”—terms referring to what is now known as altitude sickness—as well as difficulties with hiring riding and pack animals, finding reliable guides, and obtaining provisions.

Near Lhasa, Baaza Bagshi fell seriously ill. According to his own account: “My chest swelled, my breathing became labored, as if gases were rising from below; my liver suffered; there was no place in my body, in my bones, in my flesh that did not hurt.” (Pozdneev 1897, p. 190). Baaza Gelung could no longer walk. Believing he was dying, he gave his companion Dorji Ulanov all his things and entrusted him to the soibon13 of the Tibetan Baridu14 Gegen15 and the Tibetan monk Jinba.

Having diagnosed himself, Baaza Gelung began treating the illness on his own. He brewed black tea, poured some cognac into it, and induced sweating. After consuming a broth made from fresh mutton, he took a medicine called suruktszan dzujik16. Then, he fried salt in butter and applied it overnight to his liver. Following these procedures, he awoke the next morning almost completely recovered (Pozdneev 1897, p. 191).

In his travel notes, Baaza writes that the cause of his illness was not only environmental (“atmospheric influence”) but also dietary: “Living in our nomadic camps, we could not endure such hardships as eating black tea, dried chopped beef, and millet, while at the same time traveling daily.”(Ibid.). It was common practice among the Kalmyks to consult a zurkhachi (astrologer) before undertaking any important task—whether digging a well, building a house, arranging a marriage, or embarking on a long journey. Thus, in Urga, one of Baaza Bagshi’s companions, Liji Iderunov, was advised by the Bogdo Gegen17 and high lamas to continue his journey: “If he goes on a long journey, he will fall ill.” (Pozdneev 1897, p. 138). Iderunov heeded this warning and remained in Urga.

During his stay in Ikh Khüree18, Baaza Bagshi received several initiations from Yonzon Khambo:19 the Initiation of the five deities of Mañjuśrī (Tib. ‘jam dbyangs lha lnga’i dbang), the Life Force Entrustment and Permission Ritual of the Protector with Five Bodies (Tib. sku lnga’i srog gtad rjes gnang), the Oral Transmission of Gurupūjā (Tib. bla ma mchod pa’i lung), and the Long Life Initiation of Amitāyus (Tib. tshe dpag med kyi tshe dbang) (Pozdneev 1897, pp. 133–34).

It is necessary to note that A. M. Pozdneev mistakenly corrects Baaza Bagshi in the note ”’Ayukayin tseban’ is a strange—although quite often encountered in literature—combination of the Kalmyk word “Ayukayin” with the Tibetan “tsevan”. Analyzing this last tshe dbang, we find that the second half, dbang, is the already explained word “van”, i.e., a well-known religious rite, equated by us with initiation; the first half, tshe, is the initial syllable of the name tshe dpag med denoting the same Ayuka (Schmidt, Tibetan Works, p. 459). The author obviously should have said ayukayin abišiq if he wanted to speak in Mongolian, and if he wanted to use the Tibetan name, the word čebang would have been sufficient.”(Ibid., p. 134).

In fact, the Tibetan term tsewang/tsebang (Tib. tshe dbang) refers to any long life empowerment, of which there are many. This empowerment aims to prolong the life of the recipient through the blessings of a long life deity, which may include Amitāyus, White Tārā, Uṣṇīṣavijayā, White Cakrasaṃvara, Yellow Vajrabhairava, and others. Therefore, in the expression Ayukayin tsebang, the syllable tshe (Tib. tshe) denotes “longevity” in general—not specifically Amitāyus (Tib. tshe dpag med) nor “Ayuka” in the Kalmyk language, as interpreted by A. M. Pozdneev. Thus, Ayukayin tsebang should be understood as “the long life empowerment of Amitāyus.”

On the 26th day of the month of Horse20 in 1892, Baaza Bagshi reached Lhasa. After paying homage at many shrines, he received the blessing of the Dalai Lama himself. In addition, he visited major monastic centers, including Ganden21 and Kumbum22, traveled to Lake Ökön Tengri23, and toured the monastery of Narthang, which housed the renowned printing house responsible for producing the Kangyur and Tengyur24.

After spending the winter in Lhasa, Baaza Bagshi began his return journey and, in the month of the Hen25 in 1893, arrived back at his home monastery, Dundu Khurul. There, in seclusion, he began to write a detailed account of his long journey. He concludes his work with the following words: “May the salvation of Buddha descend, may all sentient beings enjoy peace, may the spirit of virtue be reborn” (Pozdneev 1897, p. 119).

The truthful account of his completed pilgrimage to Tibet generated considerable interest not only among the Kalmyk public but also within the scholarly community. In 1896, the manuscript—written in the Kalmyk language using the “clear script”—was acquired by the renowned Russian Mongolist A. M. Pozdneev. He translated it into Russian and, just a year later in 1897, published the manuscript along with his translation and commentary under the title The Narrative of the Journey to the Tibetan Country of Maloderbet’s Baaza Bagshi, in St. Petersburg. Pozdneev’s translation, based on direct collaboration with Baaza Bagshi, represented a significant scholarly contribution and helped shape Russian academic discourse on Tibetan and Mongolian Buddhism. The Faculty of Oriental Languages at St. Petersburg University even dedicated this publication (Vol. XI) to the International Congress of Orientalists in Paris. The present analysis is based on Pozdneev’s Russian translation.

Baaza Bagshi’s route to Tibet led through Urga (modern-day Ulaanbaatar) in Mongolia, Kumbum in Amdo, Dulan-Baishin, and Nakchu in Central Tibet. It is known that, following in his footsteps, several other Kalmyk pilgrims—including P. Dzhungruev, L. Arluev, D. Ulyanov, and N. Ulanov—also journeyed to Tibet, some of whom met the Dalai Lama as well. They left written accounts of their travels, which were later published in Russian. However, identifying references to these pilgrims in Tibetan sources remains challenging, as their monastic Tibetan names—under which they may have been mentioned in the Tibetan biography of the 13th Dalai Lama—are unknown.

Undoubtedly, Baaza Menkedjuev’s visit to Tibet made him a famous and respected figure. In his spiritual career, he reached the rank of senior bagshi—akh bagshi—which granted him the authority to oversee all the khuruls (Buddhist monasteries) of the Maloderbetovsky ulus, numbering 41 in total.

Baaza Bagshi actively participated in public life. In the Report of the Russian Geographical Society for 1903, he is listed as a member-employee. The report notes that his narratives, “in addition to the interest aroused by the simple description of the places traveled, are also significant as the first example of descriptive Kalmyk works for Europeans and represent an excellent example of the living language of modern Kalmyk literature” (Otchet imperatorskogo Russkogo geograficheskogo obshchestva za 1903 god 1904, p. 7).

Baaza Bagshi actively participated in the 1902 exhibition Historical and Modern Costumes, held at the Tauride Palace in St. Petersburg. For this exhibition, he sent several personal items: a gebko26 hat, a gebko robe, a red belt (orkomji), a tangka of Burkhan Bagshi27, and a Dorjin Jodva28 (Diamond Sutra) prayer book. After the exhibition, he donated many of his exhibits to the Russian Museum, for which he was awarded a silver medal “For Diligence” (Bembeev 2013, p. 9).

While in St. Petersburg, Baaza Bagshi became acquainted with the renowned Finnish orientalist G. J. Ramstedt, who later visited him in Kalmykia in March 1903, by which time Baaza Bagshi was already bedridden (Ramstedt 1978, p. 105). There is evidence that Baaza Bagshi and his closest associates convened a council of Kalmyk bagshis and gelungs in 1900 at the summer quarters of Dundu Khurul, in the Umantsy tract. Apparently foreseeing a crisis facing the Kalmyk people and seeking to prevent the fragmentation of the uluses, he proposed a program titled the “Unification of the Khurul Space” aimed at consolidating the monastic network across all Kalmyk nomadic encampments (Bembeev 2013, p. 11).

When Baaza Bagshi fell ill in 1903, Prince Tseren-David Tundutov arranged for his medical treatment. However, all efforts proved ineffective, and Baaza Menkedjuev died later that year. Noyon Tundutov brought his body to a site known as Oran Bulg—meaning “Spring of the Upland”—where a khurul complex had been planned. At the site of his cremation, a suburgan (stūpa) was erected as a cult monument in his honor (Ibid. p. 11).

Photographs of Baaza Bagshi and his suburgan were later published by G. J. Ramstedt in his book Seven Journeys Eastward, 1898–1912: Among the Cheremis, Kalmyks, Mongols, and in Turkestan, and to Afghanistan (Ramstedt 1978, p. 243).

Since Baaza Bagshi’s travelog has not yet been translated into English, below, we offer extensive quotations from the original to acquaint readers with his work and to facilitate comparison with information found in the biography of the 13th Dalai Lama. It is our hope that, one day, his travelog will be translated into English in its entirety.

2. Information from the Biography of the 13th Dalai Lama

The biography of the 13th Dalai Lama, Thubten Gyatso, titled Necklace of Amazing Jewels (Tib. ngo mtshar rin po che’i phreng ba), was composed in two volumes by the 4th Phurchok Thubten Jampa Tshultrim Tendzin (Tib. phur lcog thub bstan byams pa tshul khrims bstan ‘dzin; b. 1902–?) (Phur lcog 2010). This biographical work contains a wealth of historically significant detail.

Of particular note is its reference to the conferral of both a round and a square seal upon tsenshab29 Agvan Dorzhiev30 and Ganjurva Gegen Danzan Norboev31—an event that underscores their elevated status and the formal recognition of their roles within the Tibetan and broader transregional Buddhist hierarchies (Mitruev 2024).

In his own account, Baaza Bagshi describes only four personal audiences with the Dalai Lama, though it is possible he met with him as many as six times. Notably, while Baaza Bagshi’s travelog makes no mention of receiving a diploma or the conferral of round and square seals, such honors are mentioned in the Dalai Lama’s biography.

It should be noted that although, according to A. M. Pozdneev, the Kalmyk Month of the Dog corresponds to August of the Western calendar, the Month of the Pig to September, the Month of the Mouse to October, and the Month of the Cow to November (Pozdneev 1897, p. XIV), there is no fixed correlation between the Kalmyk and Western calendars. These correspondences may vary from year to year.

We do know, however, that in the Kalmyk calendar, the festival of Zul (the Anniversary of Lama Tsongkhapa) falls on the 25th day of the month of the Cow. From the biography of the 13th Dalai Lama, it is also known that in 1892, the 25th day of the Kalmyk month of the Cow coincided with the anniversary of Lama Tsongkhapa—celebrated on the 25th day of the 10th month of the Tibetan calendar—which, in that year, fell on December 13. Thus, in 1892, the Kalmyk Month of the Cow corresponded to December in the Western calendar, the Month of the Mouse to November, the Month of the Pig to October, and the month of the Dog to September.

Moreover, it is important to keep in mind that Russia transitioned from the Julian to the Gregorian calendar only in 1918, with a difference of 12 days. This further complicates date conversions and calendar synchronization.

3. Account of Baaza Bagshi’s First Audience with the Dalai Lama

The description of Baaza Bagshi’s first audience with the Dalai Lama is as follows:

“Then, when on the morning of the 3rd of this Month of Dog32 we came on foot from Hlasa33 to Norbu Lingka34, the worshippers had already assembled and about 300, 400 people were bowing at the worship of that day. They were brought in first and permitted to prostrate before us. These worshippers are usually forced to pass directly behind each other, and the gatekeepers who bring them in and accompany them hold long, very long whips in their hands, and they are brought in and accompanied by people of tall, very tall stature. Having led us through the middle of the servants standing before Gegen35, who were arranged in the manner described above, and having placed us before the Gegen, they made us bow three times, touching our foreheads to the ground; and when we presented the mandal36 given to us with our own hands, the Gegen deigned to accept it with his own hands and handed it to the soibun standing nearby. I also brought the gusun-tuk37, in due order: one burkhan38, one religious book and one suburgan, and then I placed on the table a long khadak39, 5 liang40 of white silver and a gold coin of our Russian Tsar; then, when, taking off my hat, I wanted to receive a blessing, the Gegen deigned to place his hands on my head in blessing. Immediately, without delay, I was led further and the next person was admitted to the hand. (Meanwhile) the soibun twisted a piece of red or yellow silk for the previous worshiper, blessed it with a breath and presented him with such a cord, called “zangia”41. We were all seated in front of the Gegen and honored with the remains of tea and rice from the Gegen’s meal. At the same time, the interpreter who was with the Gegen approached us and said to us in Mongolian: “The Gegen asks whether you have all arrived in good health and whether the faith and civil government of each (country you passed through) are at peace?” We, sitting, answered that we had arrived safely and the countries were at peace. We then bowed. The interpreter conveyed this response to the Gegen, who asked nothing further. Then the Gegen graciously gave to the people who had come to this worship an oral transmission (lung) for two small sacred books: Ganden Lha Gyama (dga’ ldan lha brgya ma) and Phak Tö (‘phags stod).”(Pozdneev 1897, pp. 208–9)

It appears that at the time of their first audience, Baaza Bagshi and his companions had not yet made the acquaintance of Agvan Dorzhiev—referred to in the travelog as “Buryat Akban”—and, accordingly, had not been formally introduced to the Dalai Lama. For this reason, Baaza Bagshi’s initial meeting with the Dalai Lama is not separately recorded in the Dalai Lama’s biography.

Later, however, Baaza Bagshi did meet Agvan Dorzhiev. He provides the following account of their interaction:

“…Already on the way to Tibet, we heard reports that there (in Hlasa) lives a soibun42 of the Gegen43, a Mongol named Buryat Akban. It was said that if one were to become acquainted with this person, it would be highly beneficial for a Mongol visitor. Knowing this, we introduced ourselves to him immediately upon our arrival in Hlasa. He received us warmly and honored us greatly. We became very good friends with him, conversed often, and he guided us in all our affairs. During our audiences with the Dalai Lama and the Nomuyin Khan44, this Akban advised and accompanied us with great skill. As for the residence of this soibun, he lived in the state baishin45 of the Gegen and, according to stories, from among the people speaking the Mongolian language, there has not yet emerged a person who would rise so high in Tibet as he did, no other Mongolian-speaking individual had ever risen so high in the Tibetan hierarchy. We reported to this Akban soibun the intentions we had formulated back in our native nomad camps, the details of our journey, and everything else. We asked him not only to guide us, but also to assist those from our homeland who might come in the future to make pilgrimage to Zū46. He graciously agreed to help both them and us—the people of a country from which no one had come to Tibet for many years.”(Pozdneev 1897, pp. 211–12)

4. Account of Baaza Bagshi’s Second Audience with the Dalai Lama

The second meeting between Baaza Bagshi and the Dalai Lama is described in the Dalai Lama’s biography as follows:

“When the Dalai Lama turned 17, in the seventh month47 of <…> the Water Dragon year (1892—B.M.) <…> the Dalai Lama accepted an offering to establish an auspicious connection through a lavish prayer for long life through the Uṣṇīṣavijayā ritual. The offering was made by the envoy of the Derbet Dalai Taiji, the abbot of Sangak Choinkhorling Lobsang Sharab, who having invited the designated number of monks from Namgyal Monastery made an offering to them48.

From this passage, we learn that Baaza Bagshi is referred to by the Tibetan title mkhan po—abbot—of the Sangak Choinkhorling monastery. Russian archival documents also confirm that Baaza Bagshi held the title of Bagshi of the Sangak Chonkhorling khurul. Therefore, we may conclude that the Kalmyk title Bagshi functioned as the equivalent of the Tibetan mkhan po (abbot). Among the Mongols, similar designations include shireet lam (Mong. siregetü blam-a, lit. “holder of the throne”) and khambo (Mong. qambu, “abbot”).

Furthermore, Baaza Bagshi is identified in the Tibetan biography as the envoy of the Derbet Dalai Taisji. Although the titles taishi (Chinese: 太师, tàishī) and taiji (Chinese: 太子, tàizǐ) originate from distinct Chinese terms, Tibetan sources often failed to differentiate between them. The title Dalai Taishi appears in Baaza Bagshi’s own narrative as well (Pozdneev 1897, p. 121). However, in this context, the reference is most likely to the nobleman noyon David Tsandjinovich Tundutov—a descendant of the historical Derbet Dalai Taishi—since the original Dalai Taishi lived in the second half of the 17th century and could not have been a contemporary of the 13th Dalai Lama.

The account of the second audience with the Dalai Lama, as presented by Baaza Bagshi himself, is as follows:

On the 9th day of this Month the Dog [we] brought the tribute maṇḍala to the Gegen. The outward form of presenting this tribute maṇḍala was similar to the previously described ritual of offering the gusun-tuk mandal, but with the, but with this extra addition.In Bodal49 there is a datsan50 with approximately 400 khuvaraks, known as Namjal Datsan51, whose duty it is to perform khuruls at the Gegen. According to the resources of the one making the offering, a number of khuvaraks from this datsan are invited to serve the tribute khurul before the Gegen. Upon completing the khurul, they are permitted to pay homage in the manner described earlier.For our tribute, we invited one hundred khuvaraks to serve the khurul52; Demu Khutukhtu53 and Yongzang Jamba Rinboche54 also attended this khurul and sat down before the Gegen. Of the tribute offerings, one third was presented to Demu Khutukhtu, and Yongzang Jamba Rinboche was presented with 15 liang of silver. Following established custom, we were seated before the Gegen, offered the remains of his meal, and honored by having a white khadak hung around our necks by his own hand. We also received generous gifts from the Gegen’s treasury: fifty liang of silver, three pieces of Tibetan cloth, two bast baskets of Tibetan tea (the same used by the Dalai Lama), and one bundle of thick incense candles. From the treasury of the Nomyin Khan, we received a khadak, one piece of cloth, a bast basket of tea, and 25 liang of silver. From Yongtsang Jamba Rinpoche, we received a khadak, along with—individually from each dignitary— rilu55 (sacred pills), sacred cords wearing around the neck, and holy water. After we had been honored with such favors, we left and were invited to attend the midday meal. There, in the large audience hall where the Gegen confers blessings, we partook—together with his attendants—of boiled meat, millet, and dzamba56. The Gegen ate the same food in a special room. We were again honored with the remains of his food.(Pozdneev 1897, pp. 212–13)

5. Account of Baaza Bagshi’s Third Audience with the Dalai Lama

During the third audience, Baaza Bagshi received a long-life initiation of Amitāyus from the Dalai Lama. This is what he tells about it:

“On the 8th57, having gone to Norbu Lignka, I introduced myself and paid my respects to the Buryat Akban. Even before my above-described departure from Hlasa, I reported to this Akban-soibun of my wish to receive the Ayukain Tsewang from the Gegen. After our departure, he informed the Gegen about this and it was decided that this tsewang would be conferred on the 15th day of the current month. Having heard about this, I returned home with joy.”(Pozdneev 1897, p. 223)

“On the 15th58, when the Dalai Lamain Gegen conferred the initiation known as Ayukhayin Tsewang, the ceremony, headed by the Demu Khutukhtu ruling the Tibetan civil government, was attended by the Tibetan Gegens, princes, spiritual and secular, as well as the Mongols; Altogether, two to three thousands of us were present and honored.

Starting from the 16th, when the Gegen graciously bestowed the lung59 on Jad-domba, we—together with the 21 soibuns who had also come to the Gegen—received this transmission over the course of five days.”(Pozdneev 1897, pp. 225–26)

The same initiation is described in the Dalai Lama’s biography:

“From the 14th <…> of the eighth month60 <…> at Nyiod [residence], he [the Dalai Lama] gracefully placed his two feet upon the offering platform. Immediately thereafter, all those who carry out his commands—from the Regent down to the stablemen—as well as the superior, middling, and common attendants, the [abbots of] various monastic seats, and the great lamas and incarnations—all those sustained by his unceasing kindness—offered a vast array of clouds of auspicious offerings. He bestowed blessings and enjoyed the secular and religious feast of delight with sixfold manner.

In response to the fervent supplications of Gelong Lobsang Shadrub61, Khenpo of [monastery] Sangngag Chonkhorling [that belongs to] Torgud62 Derbets—one of the separate tribes of Mongols living in the Northern direction—who are people under command [of the Dalai Lama], bound by the rope of his compassion from previous lifetimes of the supreme guide of the three realms, the incomparable lord lama (the Dalai Lama—B. M.), graciously agreed to bestow the boundless stages of empowerment and blessings of the Bhagavan Lord Amitāyus to suitable disciples. Among countless stages of empowerments and blessings of this deity the most renowned and endowed with particularly powerful blessing is the Single Deity, Single Vase Longevity Empowerment transmitted from the sole Powerful Lady of Yogis, the Sole Mother, Siddharājñī. He promised to grant these longevity empowerments and blessings.”63

6. Account of Baaza Bagshi’s Fourth Audience with the Dalai Lama

The fourth audience took place on 13 December 1892. This meeting is not mentioned in the Baaza Bagshi’s Narrative the Journey to the Tibetan Country, but it is recorded in the Dalai Lama’s biography:

“In the tenth month <…> [the Dalai Lama] took part in the traditional celebration of Lama Tsongkhapa’s anniversary64. He bestowed blessings on the abbot of Chonkhorling [monastery] in Derbet region and on fifty other people, and gave oral transmission of the Prajñāpāramitā Heart Sutra and the mantras of the Protectors of the Three Families.65”

7. Account of Baaza Bagshi’s Fifth Audience with the Dalai Lama

The fifth and final audience described by Baaza Bagshi occurred on 19 February 1893. His own narrative contains only a brief mention:

After this, on the 5th66 (of the Kalmyk month of Dragon—B. M.) we went to Bodala for the New Year and paid homage to the Dalai Lamain Gegen.(Pozdneev 1897, p. 246)

However, the Dalai Lama’s biography gives a much more detailed account:

When [the Dalai Lama] reached the age of eighteen, in the year of the Water Snake (1893—B.M.) <…> on the third day [of the first Tibetan month], <…> [the Dalai Lama] bestowed a blessing with his hand on the abbot [of the monastery] of Chonkhorling of the Derbet Nutuk of the Torgud [Khanate], Lobsang Sharab, who had arrived for a farewell visit, together with his entourage, [the Dalai Lama] also gave tea, instructions on temporary and permanent virtue, and lavish farewell gifts. In particular, as an expression of recognition of the achievements accomplished through the power of supreme intention, [the Dalai Lama] bestowed a complete set of abbot’s robes, a square and round seal, a charter with the title, and many types of samaya substances67 and blessed images. As a farewell instruction, [the Dalai Lama] with great joy gave the oral transmission of the Exposition of the Stages of the Path68, “The Essence of Molten Gold.”69

Notably, Baaza Bagshi’s own narrative does not mention receiving either the charter or the two seals. However, Shamba Balinov writes in his article On the Princely Family of the Tundutovs: “…The Dalai Lama himself, as a sign of his special favor, gave Tundutov his special seal (“eternal visa”) by which the gates of Lhasa would be opened at any time.” (Balinov 1936, p. 42). This remark may refer to one of the seals originally given to Baaza Bagshi. It is plausible that upon returning home, Baaza Bagshi gave one or both seals to Prince Tseren-David Tundutov. The subsequent fate of the seals is unknown.

It is also conceivable that Baaza Bagshi chose to omit mention of the charter and seals from his narrative to avoid scrutiny from the Russian imperial authorities, who actively monitored and sought to control any interactions between Russian subjects and foreign spiritual or political leaders.

8. Account of Baaza Bagshi’s Sixth Audience with the Dalai Lama

It is possible that Baaza Bagshi met with the Dalai Lama for the sixth time immediately before his departure. Baaza Bagshi describes a brief meeting with the Gegen, the title previously used to refer to the Dalai Lama:

“…Then on the 28th (March 3rd) I introduced myself and bowed to the Gegen, and was honored to receive holy water, a blessing, an idol of Buddha Shajamuni70, a sacred book in one volume, etc.”(Pozdneev 1897, p. 247)

This meeting is not recorded in the Dalai Lama’s biography, possibly due to its brevity.

9. Conclusions

This study highlights the mutual importance of Tibetan and Kalmyk historical sources. Not only does it contribute to the understanding of Kalmykia’s religious and political history, but it also demonstrates the necessity of cultural and linguistic contextualization in interpreting Tibetan sources—especially those pertaining to non-Tibetan pilgrims. Accurate translation of the relevant passages in the Dalai Lama’s biography requires a nuanced knowledge of Kalmyk terminology, social structures, and historical realities of the late 19th century.

The figure of Baaza Bagshi emerges as a devoted and resilient pilgrim, undeterred by the hardships of his long and difficult journey. His mission, undertaken on behalf of Prince Tseren-David Tundutov, can be seen as one of the final expressions of Kalmyk agency in international Buddhist diplomacy before the consolidation of Russian imperial control. The likely deliberate omission in Baaza Bagshi’s narrative of receiving seals and a diploma from the Dalai Lama—items which are mentioned in the Dalai Lama’s own biography—suggests a desire to avoid scrutiny by the Russian authorities. Further evidence of Prince Tundutov’s efforts to maintain ties with the Dalai Lama can be found in his later correspondence with the Tibetan leader (Ishihama and Takehiko 2022).

Baaza Bagshi’s account, published by A. M. Pozdneev and long overlooked, is one of the earliest surviving travelogs of a Russian subject visiting Tibet. The present analysis brings forward not only a new reading of this journey from the host’s perspective—through the Dalai Lama’s biography—but also a valuable contribution to the little-studied history of Kalmyk–Tibetan relations.

In a broader sense, the recovery of such narratives supports the preservation of Kalmyk historical memory and cultural identity. As a small ethnic group currently residing in the Republic of Kalmykia within the Russian Federation, the Kalmyks face the challenges of globalization and cultural assimilation. Documenting and analyzing their historical engagements with the wider Buddhist world help maintain a sense of continuity and agency, ensuring that such stories remain part of both scholarly discourse and communal self-understanding.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Bagshi: A Kalmyk word meaning “teacher” or “an abbot”. |

| 2 | Gelung (Oir. gelüng; Tib. dge slong): A fully ordained Buddhist monk who holds 253 vows. |

| 3 | Ulus: An administrative unit of Kalmykia in the Russian Empire, analogous to a district. A Kalmyk ulus consisted of several aimaks (clans), and an aimak was divided into khotons (families). Maloderbetovskiy Ulus existed in the Russian Empire as part of the Astrakhan Governorate from 1788 to 1920. |

| 4 | Khurul (Oir. xurul): A Buddhist monastery. |

| 5 | See note 3. |

| 6 | Zaisang and noyon—members of the upper class in the Kalmyk society. |

| 7 | (Bembeev 2013, p. 9). The initial stage of monastic ordination within the Kalmyk–Tibetan Buddhist tradition. NA RK (National Archive Republic of Kalmykia, Elista, Russia). File I-9. Inventory 11. Act 1410. List 52. |

| 8 | Derbet is an ethnic group of Kalmyks. |

| 9 | Galdan Tseren was eldest son of Derbet lord Laban Donduk. After his father’s death in 1749 Galdan Tseren became the lord of Derbets. He passed in 1764 leaving a son, Tsebek Ubushi, who died in 1774. |

| 10 | Information about this embassy from the biography of the 7th Dalai Lama is discussed in detail by us in another article (Mitruev 2022). |

| 11 | NA RK. File I-9. Inventory 11. Act 1410. List 52. |

| 12 | All Kalmyk names of Tibetan origin are written according to Kalmyk pronunciation. |

| 13 | Soibon or soibun (Oir. soibon; Tib. gsol dpon): a servant of a noble cleric in Mongolia and Kalmyk Steppe. |

| 14 | We were unable to identify the Tibetan name of this lama. |

| 15 | Gegen (Oir. gegēn) one of the highest ranks of the Buddhist clerical hierarchy. |

| 16 | Suruktszan dzujik (Tib. srog ‘dzin bcu gcig): A Tibetan herbal medicine. Its ingredients are Aquilaria agollocha, Myristica fragrans, Melia composita, Bambusa textilis, Shorea robusta, Saussurea lappa, Terminalia chebula, Mesua ferrea, Eugenia caryophyllata, yak heart, and Ferula jaeschkeana. Its properties: This compound has a strong analgesic effect on pain caused by the accumulation of rlung (“wind”). It is used to treat the accumulation of wind in the heart and srog rtza (pulsating streams of life—literally “life channels,” defined as srog rtsa dkar po [spinal cord] and srog rtsa nag po [main artery]). This condition may lead to acute mental and emotional disturbances, such as constant fear and anxiety, insomnia, loss of consciousness, difficulty breathing and swallowing, bodily trembling, increased sweating, and pain in the upper chest and right hypochondrium. |

| 17 | Bogdo Gegen or 8th Jebtsundamba Khutuktu Agvaanluvsanchoyjinyamdanzanvaanchigbalsambuu (Tib. rje btsun dam pa ngag dbang blo bzang chos rje nyi ma bstan 'dzin dbang phyug; 1870–1924), was the secular and spiritual head of Mongolia. |

| 18 | Ikh Khüree (Mong. Их хүрээ), “The Great Monastery”, refers to the monastic-city complex that evolved in to the modern-day capital of Mongolia, Ulaan Baatar. |

| 19 | Yonzon Khambo Luvsankhaimchig (Mong. Ёнзон-хамбо Лувсанхаймчиг; Tib. yongs 'dzin mkhan po blo bzang mkhas mchog; 1872–1937) principal Tibetan tutor of Bogdo Gegen VIII. |

| 20 | (Idid., p. 201). The month of Horse approximately corresponds to May of 1892. |

| 21 | Ganden (Tib. dgal ldan): One of the “great three” Gelug university monasteries located near Lhasa in Tibet. The other two are Sera and Drepung. Ganden was founded in 1409 by Je Tsongkhapa Lobsang Dragpa, the founder of the Gelug school of Tibetan Buddhism, which is the primary tradition followed by the Kalmyks. |

| 22 | Kumbum (Tib. sku 'bum) is a large Buddhist monastery in the Tibetan region of Amdo. |

| 23 | Ökön Tengri (Tib. Lha mo bla mtsho): A sacred lake located in southern Tibet, in present-day Gyatsa County. It is associated with the female deity Palden Lhamo (Tib. dpal ldan lha mo), the protectress of the Dalai Lama lineage. |

| 24 | Kangyur (Tib. bka’ ‘gyur) and Tengyur (Tib. bstan ‘gyur): The two main divisions of the Tibetan Buddhist canon, representing the core texts of Tibetan Buddhism. The Kangyur contains the translated words of the Buddha (sūtras and tantras), while the Tengyur comprises commentaries and treatises by Indian and other Buddhist masters. |

| 25 | Month of the Hen approximately corresponds to August 1893. |

| 26 | Gebko (Tib. dge bskos; Oir. gebgüü) disciplinarian or a proctor in a monastery. |

| 27 | Burkhan Bagshi (Oir. Burqan baγši) translates from Kalmyk as Teacher Buddha (Burkhan). Tanka (Tib. thang kha; Oir. tangxa) is Tibetan word meaning a scroll painting on cloth. |

| 28 | Dorjin Jodva (Sanskr. Vajracchedikā; Tib. rdo rje gcod pa)—the Diamond Cutter Sūtra, a Mahāyāna Buddhist sūtra from the genre of Prajñāpāramitā (‘perfection of wisdom’) sūtras. |

| 29 | Tsenshab (Tib. mtshan zhabs)—partner of the Dalai Lama in a philosophical debate. |

| 30 | Buryat Agwan Dorjiev also known as Ngawang Lobzang (Tib. ngag dbang blo bzang) was appointed as one of the Dalai Lama's assistant tutors (Tib. mtshan zhabs) in debating practice. He established a close relationship with the young Dalai Lama XIII and was a visible political figure. |

| 31 | Ganjurva Gegen Danzan Norboev (1888–1935), a Buryat scholar-lama, 6th reincarnation of the Ganjurva gegen from Dolonnor, Inner Mongolia. |

| 32 | This corresponds to August or September of 1892. |

| 33 | Hlasa is an alternative spelling of the name of the capital of Tibet, Lhasa. |

| 34 | Norbu Linka or Norbulingka (Tib. nor bu gling ka) literally “Jeweled Park” is a palace and surrounding park in Lhasa, built from 1755. It served as the traditional summer residence of the successive Dalai Lamas. |

| 35 | Though Kalmyk and Mongolian word Gegen may mean one of the highest ranks of the Buddhist clergy or Bogdo Gegen the secular and spiritual head of Mongolia here and on in the work of Baaza Bagshi it denotes the Dalai Lama XIII. |

| 36 | Mandal or maṇḍala is a Sanskrit word that here means symbolical offering of the entire universe to the Buddha or deity, often using a physical maṇḍala plate and various symbolic items. |

| 37 | Gusun-tuk (Tib. sku gsung thugs), offering three images of the body, speech and mind of the Buddha: a statue, a Buddhist text and a stupa (Oir. suburγan). |

| 38 | See note 37. In this case, it refers to a statue of Buddha. |

| 39 | Khadak (Tib. kha btags; Oir. xadaq) Tibetan ceremonial scarf that serves as a traditional item of offering. |

| 40 | Liang (Chin. 两; liǎng) or tael is a monetary unit containing about 37.3 grams of pure silver. |

| 41 | Zangia (Oir. zangya; Tib. srung mdud) protecting cord which is tied on the neck. |

| 42 | See note 13. |

| 43 | Here and further under this name Gegen Baaza Bagshi means the Dalai Lama. |

| 44 | Nomuyin Khan or Nomun Khan (Oir. nom-un xan; Tib. chos kyi rgyal po) is Oirat name for Dharma King (Sanskr. dharmarāja). Here it means Demo Khutukhtu the regent of Tibet (See note 53). |

| 45 | Baishin (Oir. bayišing) house, residence. |

| 46 | Zū (Oir. zuu)—Kalmyk name for Tibet that originates from Tibetan Jowo (Tib. jo bo), “lord” that means Jowo Rinpoche, the holiest statue of Lhasa, which by metonymy also designates the city itself (Cf. Mong. Juu, Baraγun juu) or whole of Tibet. |

| 47 | The seventh lunar Tibetan month of the Water Dragon year approximately corresponds to August of 1892 in the Western calendar. |

| 48 | (Phur lcog 2010, p. 359). dgung lo bcu bdun zhes pa chu 'brug 353 <…> zla ba bdun pa'i nang <…> dur bed dA las tha'i ji'i mi sna gsang sngags chos 'khor gling gi mkhan po blo bzang shes rab nas rnam grwa grangs bcad bsnyen bkur gyis sbran te rnam rgyal ma'i sgo nas zhabs brtan gyi rten 'byung gzab rgyas 'bul bzhes dang / |

| 49 | Bodal (Oir. bodali)—the Potala, palace of the Dalai Lama in Lhasa. |

| 50 | Datsan (Tib. grwa tshang; Oir. dacang): A Buddhist monastery or a monastic college. |

| 51 | Namjal Datsan (Tib. rnam rgyal grwa tshang): Privet monastery of the Dalai Lama in Potala Palace in Lhasa. |

| 52 | Khurul (Oir. xurul): Religious service. |

| 53 | Demu Khutukhtu or Demo Qutuqtu Ngawang Lobzang Trinle Rabgye (Tib. de mo hu thug thu ngag dbang blo bzang ‘phrin las rab rgyas; 1855–1899) was the ninth Demo Rinpoche and the regent of Tibet before the rule of the Thirteenth Dalai Lama. In 1886, when the Thirteenth Dalai Lama was 11 years old, Demo became Tibet’s regent. Demo was the head of the Tengyeling Monastery (Tib. bstan rgyas gling). In the Wood Sheep year (1895), Demo stepped aside and the Dalai Lama was enthroned as the spiritual and political ruler of Tibet. He was convicted of plotting against the Dalai Lama and executed in 1899. |

| 54 | Yongzang Jamba Rinboche or Yongdzin the Third Purchok Phurchok Lobsang Jampa Gyatso Rinpoche (Tib. yongs ‘dzin phur lcog blo bzang byams pa rgya mtsho; 1825–1901) was one of the official tutors of both the 12th and the 13th Dalai lamas. |

| 55 | Rilu (Tib. ri lu/ril bu) are sacred pills blessed by the Dalai Lama. |

| 56 | Dzamba (Tib. rtsam pa): Roasted barley flour mixed with Tibetan milk tea, a staple Tibetan food. |

| 57 | The 8th day of the Kalmyk month of the Pig approximately corresponds to September of 1892. |

| 58 | Here, we see a discrepancy of one day between the dates given in Baaz Bagshi’s work and the Dalai Lama’s biography. |

| 59 | Lun (Tib. lung): Oral transmission from a teacher to disciples by recitation of the Buddhist texts. |

| 60 | The 14th of the eighth Tibetan month corresponds to the 5th of October of 1892. |

| 61 | Baaz Bagshi’s monk name Lobsang Sharab (Tib. blo bzang shes rab) is mistakenly spelled here as Lobsang Shadrub (Tib. blo bzang bshad sgrub). |

| 62 | In Tibetan biographies and historical works, Kalmyks are called Torguds because their khans belonged to this tribe. Therefore, Torgud Derbet here means Derbets of the Kalmyk people. |

| 63 | (Phur lcog 2010, p. 362). zla ba brgyad pa’i <…> tshe bcu bzhi <…> nyi ‘od du dkar spro’i sar zhabs zung bde legs kyi mdud rgya bcings ‘phral srid skyong nas/ chibs ra ba yan bka’i drung na spyod pa drag ‘bring dkyus gsum dang /grwa sa khag/ bla sprul che khag sogs rnam kun bka’ drin gyi zho shas ‘tsho ba mtha’ dag nas rten ‘byung gi mchod sprin spros par phyag dbang dang / lugs gnyis kyi dgyes ston la tshim pa drug ldan du rol bar mdzad do// sa gsum gyi ‘dren mchog mtshungs med rje bla ma gang nyid kyi sku’i phreng ba sngon ma nas thugs rje’i dpyang thag gis nye bar bzung ba’i bka’ ‘bangs su gyur ba byang phyogs mong+gol gyi bye brag thor rgod dur bed gsang sngags chos ‘khor gling gi mkhan po dge slong blo bzang bshad sgrub nas gsol ba phur tshugs su btab pa la brten nas bcom ldan ‘das mgon po tshe dpag med kyi dbang bskur byin rlabs kyi rim pa mtha’ yas pa yod pa las/ kun la grags che zhing / byin rlabs kyi tshan kha khyad par ‘phags pa rnal ‘byor gyi dbang phyug ma gcig grub pa’i rgyal mo nas brgyud pa rgyal ba tshe mtha’ yas pa lha gcig bum gcig la brten pa’i tshe’i dbang bskur byin rlabs rnams snod ldan gyi gdul bya’i bgo skal du stsal bar zhal gyis bzhes te / |

| 64 | Lama Tsongkhapa’s anniversary falls on the 25th day of the 10th Tibetan month. |

| 65 | (Phur lcog 2010, p. 366). zla ba bcu pa’i nang <…> ‘char can lnga mchod chen mo’i mdzad sgo/ dur bed chos ‘khor gling gi mkhan po sogs mi grangs lnga bcur byin rlabs dang / shes rab snying po/ rigs gsum mgon po’i gzungs ljags lung / |

| 66 | Here, we see a discrepancy of two days between the dates given in Baaz Bagshi’s work and the Dalai Lama’s biography. Though both sources cite the same month, Baaza Bagshi’s work gives the 5th day and Dalai Lama’s biography gives the 3rd day of the same month. Although A. M. Pozdneev in his translation gives the date as 9th February, according to Dalai Lama’s biography, this meeting took place on 19th February 1893. |

| 67 | The samaya substances (Tib. dam rdzas): The various substances blessed by the mantra. |

| 68 | Exposition of the Stages of the Path, “The Essence of Molten Gold” (Tib. lam rim gser zhun ma), is a structured presentation of the Buddhist path to enlightenment written by the Third Dalai Lama, Sonam Gyatso (Tib. bsod nams rgya mtsho; 1543–1588). |

| 69 | (Phur lcog 2010, p. 368). dgung lo bco brgyad bzhed pa chu sbrul <…> tshes gsum 367 <…> thor rgod dur bed shog chos ‘khor gling gi mkhan po blo bzang shes rab ngo ‘khor phyir log gi thon phyag tu bcar bar phyag dbang dang / ja gral/ ‘phral phugs dge ba’i bka’ mchid/ thon rdzongs gzab pa dang / khyad par khong pa lhag bsam byas rjes mi dman pa’i bzos sgor mkhan chas cha tshang dang / tham ga gru sgor/ cho lo’i bka’ shog dam rdzas byin rten le tshan du ma/ ‘gro chos su lam rim gser gyi yang zhun ma’i lung bcas dgyes pa chen po stsal / |

| 70 | Shajamuni (Oir. Šajamuni): Buddha Śākyamuni. |

References

- Balinov, Shamba N. 1936. O kniazheskom rode Tundutovykh [On the princely family of the Tundutovs]. Kovyl’nye volny 13–14: 41–45. [Google Scholar]

- Bembeev, Evgenii V. 2013. Nasledie Baaza-Bagshi v kontekste vozrozhdeniia buddizma v Kalmykii [The legacy of Baaza Bagshi in the context of the revival of Buddhism in Kalmykia]. In Baaza-bagshi i ego dukhovnoe nasledie. Elista: ZAO NPP Dzhangar. [Google Scholar]

- Ishihama, Yumiko, and Inoue Takehiko. 2022. A Study of three Tibetan letters attributed to Dorzhiev held by the St. Petersburg Branch of the Archive of the Russian Academy of Sciences. In The Early 20th Century Resurgence of the Tibetan Buddhist World. Studies in Central Asian Buddhism. Edited by Ishihama Yumiko and Alex McKay. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mitruev, Bembya. 2022. One Seal of Donduk-Dashi Reviewed [Pechat’ Donduk-Dashi]. Biulleten’ Kalmytskogo nauchnogo tsentra RAN 2: 39–69. [Google Scholar]

- Mitruev, Bembya. 2024. About the seals of Agvan Dorzhiev and Danzan Norboev. The Tibet Journal XLIX: 59–79. [Google Scholar]

- Otchet imperatorskogo Russkogo geograficheskogo obshchestva za 1903 god [Report of the Imperial Russian Geographical Society for 1903]. 1904. Saint Petersburg: Printing house of M. M. Stasyulevich.

- Phur lcog. 2010. Phur lcog thub bstan byams pa tshul khrims bstan ‘dzin. sku phreng bcu gsum pa thub bstan rgya mtsho’i rnam thar. stod cha [Biography of the 13th Dalai Lama Thubten Gyatso. Part I]. Rgyal dbang sku phreng rm byin gyi mdzad rnam. Beijing: Krung go’i bod rig dpe skrun khang. (In Tibetan) [Google Scholar]

- Pozdneev, Aleksei M. 1897. Skazanie o khozhdenii v tibetskuiu stranu Maloderbetovskogo Baza-bakshi [The Narrative of the Journey to the Tibetan Country of Maloderbet’s Baaza Bagshi]. Saint Petersburg: Faculty of Oriental Languages, St. Petersburg University. [Google Scholar]

- Ramstedt, Gustaf J. 1978. Seven Journeys Eastward, 1898–1912: Among the Cheremis, Kalmyks, Mongols, and in Turkestan, and to Af-ghanistan. Bloomington: The Mongolia Society. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).