Commanding the Defilement Master: Materiality and Blended Agency in a Tibetan Buddhist Mdos Ritual

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materiality and the Discourse of Agency

3. The Ubiquitous Mdos Ritual

4. Grib Mdos: A Subtype of Mdos

5. The Ultimate Action of the Defilement Destroying Diamond: A Very Concise Grib Mdos Ritual (Grib ʼjoms rdo rje pha lam gyi las mthaʼ grib mdos shin tu bsdus pa): Sources and Historical Context

6. Ritual Analysis: A Translation and Discussion of Agency and Materiality

6.1. Preparation—Building the Ritual Microcosm

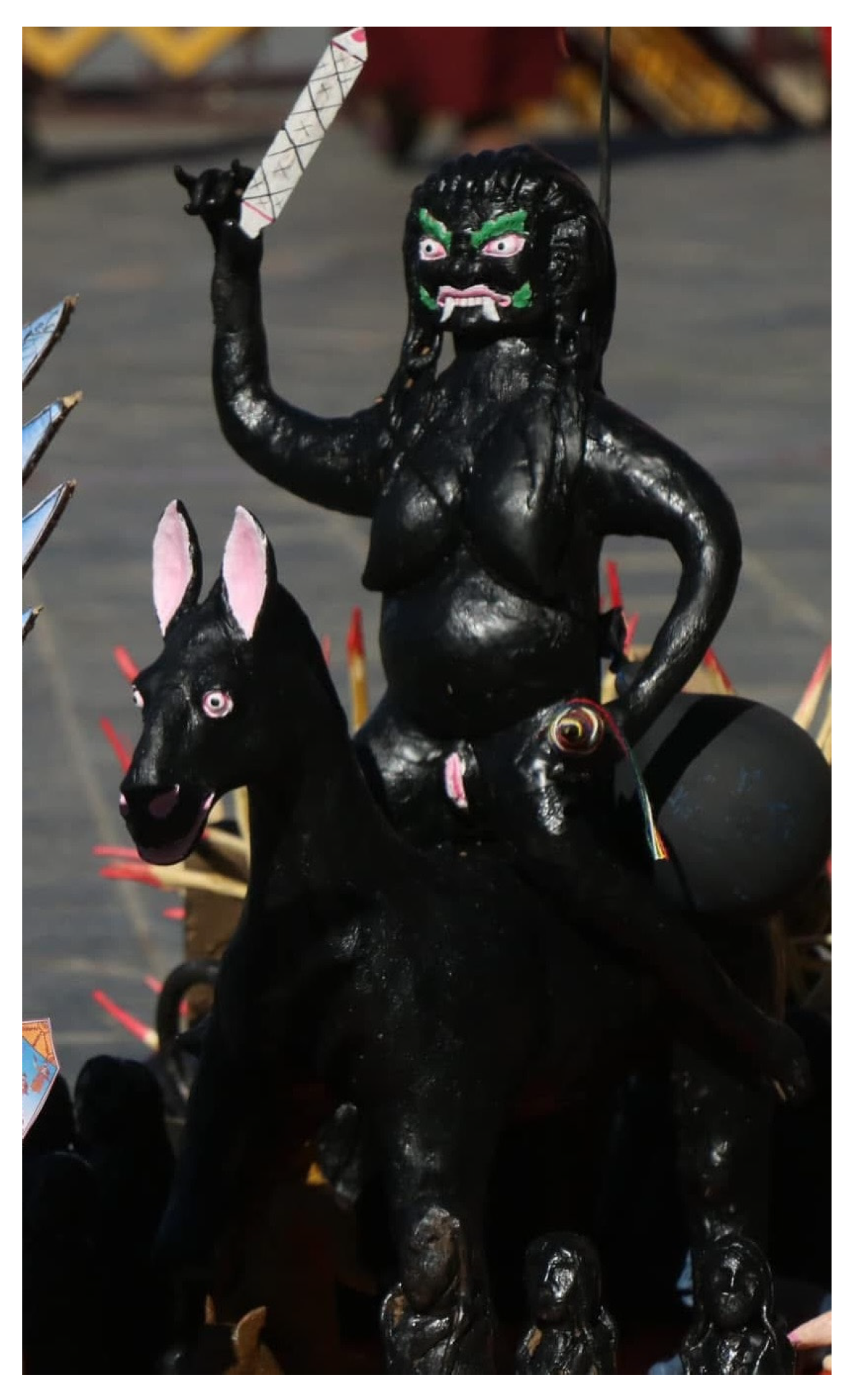

“Homage to Yamāri! {Regarding The Ultimate Action of the Defilement Destroying Diamond, A Concise Grib Mdos Ritual: Knead the black dough (zan) [made] from the roasted flour (tshig phye) of black grains (ʼbru) of buckwheat (bra) and pulses (sran). Inside an iron vessel, for instance, make a four-tiered, four-sided Mount Meru. On the first tier, place a black man with a black crest (ʼphru) on his head, mounted on a black horse. A black bird soars above. He leads a black dog at his side. He is dressed in black garments. He brandishes a black silk in his hand, [and] carries behind on his back, a shell (skogs) of an egg (sgong) [laid] by a black hen. In the four directions of the second tier, place four human forms possessing the heads of a bird, snake, pig, and frog/tortoise (sbal). On the third tier, make (byas) and arrange [on] the upper east a tiger, and so forth, either all black or each appearing in its own color. On the fourth tier, make butter lamps, offering morsels (bshos bu), squeezed dough (chang bu), spherical gtor ma (ril bu), and flattened dough (ong skyu)26 equal in number to the age of the patron, all in black color, and arrange on top of the black base in front of oneself. Altogether in a pot, gather the substances of slander (mi kha): buckwheat (braʼo), alpine bistort (ram bu), beer-making residue (sbang ma), guinea pepper (g.yer ma), bone (rus pa) and so forth. Arrange the thumb-length dough substitute effigies (ngar glud), equal in number to the age of the patron in one vessel.”27

6.2. Preparation—Deity Offerings, Visualizations, Power of Truth, and Summoning

“In addition, one must gather (ʼdu bya) the offering gtor ma for Yamāri and Bhurkuṃkūṭa (Sme brtsegs), the [standard] offerings (mchod pa), the amṛita and rakta, the music offering (rol mo), the black silk streamer (g.yab dar), and so forth. Visualize oneself as Yamāri with Bhurkuṃkūṭa clearly at the heart. In accordance with the vase treatise (bum pa gzhung), visualize Bhurkuṃkūṭa; perform recitations and so forth in accordance with the defilement destroying diamond. Afterwards, circle the black silk streamer over the head of the patron. And having spoken the power of truth (bden stobs) of Yamāri and others,32 summon the Defilement Master and dissolve (bstim) him into the figure (gzugs). Following that, regarding the chant (gyer ba) by melody (dbyangs):}”33

6.3. The Deity–Human Complex Commands the Defilement Master and His Minions

6.3.1. The Command

“Hūm; I, Yamāntaka! I, the wrathful king, Bhurkuṃkūṭa! Destroyer of conceptuality, King Heruka! All the haughty spirits of worldly appearances and all the defilement masters (grib bdag), listen to me! Kyai! Beyond the direction of the setting sun, in the deep womb (gting rum) of the Mun pa nag po,38 deep within the black castle of defilement, is the Great King Defilement Master. His body is colored black, the color of darkness (mun pa). Underneath, he mounts a black defilement horse; a black defilement bird soars above him. He wears on his body a black defilement garment and brandishes in his hand a black defilement silk. Stuck on his head is a black defilement crest. He carries on his back a defilement egg sack (snod sgong) and leads at his side a black defilement dog. [I] summon you to this place. Gather in oath (dam). Great Defilement Master, accept (longs) the defilement. Kyai! The four attendant (bkaʼ nyan) minions (las byed) of that [Master] (namely): desire (ʼdod chags) having a head of a black bird, aversion (zhe sdang) having the head of a black snake, delusion (gti mug) having a head of a black pig, and ignorance (ma rig) having the head of a black frog/tortoise (sbal). All of you Defilement Masters, [I] summon you to this place! Gather in oath! Defilement Master, accept the defilement. Kyai!”39

“The Great King Defilement Master and [your] four attendant (bkaʼ nyan) officials (blon po), you all are the defilement masters. You all are the masters of the basis (gzhi) and differentiation (byes) [of defilement]. Upon myself along with the surrounding sponsors (rgyu sbyor)—food defilements, defilement from clothes,40 the defilement of wealth; living (gson) defilement, death defilement, corpse defilement; vow-breaker (dam nyams) defilement and familial murder (rme)41 defilement, and; leprosy defilement, resentment (ʼkhon) defilement, widow (yug) defilement, and; defilement from the eight classes of spirits, that is, the gods (lha), serpent deities (klu), gnyan spirits, and so forth; the defilement of confused discursive thought (rnam rtog ʼkhrul ba), etc.; the three poisons, the five poisons, the defilement of action; afflictions (nyon mongs), previous karma (sngon las), and sudden difficulties (ʼphral rkyen) defilement; defilements like that and accumulations of wrong doing (nyes pa)—defilement masters, now accept (longs) and cleanse our defilements. Kyai!”42

6.3.2. The Retinue of Astrological Antagonists:

“Regarding the servants (bkaʼ ʼkhor) of the Great Defilement Master: The upper east has the head of a tiger; the upper west has the head of a monkey. You two seventh-edge opponents (bdun zur)43 that enemy pair (dgra gshed)44 is encircled by a retinue of a hundred thousand minor obstructing spirits (bgegs). All of you, defilement masters, now accept our defilements and perform the pacification of the harmful seventh edge. The lower east has a head of a rabbit; the lower west has a head of a bird. You two dividing ones (bye bral), that enemy pair is encircled by a retinue of a hundred thousand minor obstructing spirits. You all, defilement masters, accept now our defilements, and perform the pacifying of harmful dividing ones. The upper south has the head of a snake; the upper north has the head of a pig. You two, that enemy pair of resentment (ʼkhon) is encircled by a retinue of a hundred thousand minor obstructing spirits. You all, defilement masters, accept now our defilement and perform the pacification of the harmers of resentment. The lower south has the head of a horse; the lower north has the head of a rat. You two, that enemy pair that causes division (ru gcod) is encircled by a retinue of a hundred thousand minor obstructing spirits. You all, defilement masters, accept now our defilement and perform the pacifications of the harmers of enmity (ʼkhon). The southeast has the head of a dragon; the northwest has the head of a dog. You two, that enemy pair which trample (thog rdzis) is encircled by a retinue of a hundred thousand minor obstructing spirits. You all, defilement masters, accept now our defilement and perform the pacification of harmers who trample. The southwest has the head of a sheep; the northeast has the head of an ox. You two, that enemy pair of disastrous quarrels (phung gyod) is encircled by a retinue of a hundred thousand minor obstructing spirits. You all, defilement masters, accept now our defilements and perform the pacification of harmers of disastrous quarrel. The twelve great abiding malevolent spirits (gdon chen gnas pa), at this moment, accept our (along with that of the retinue of sponsors) defilements and harming impurities (mi gtsang gnod pa) and unions of inauspicious enemy pairs (dgra gshed skag ngan sbyor ba), and perform the pacification. In regard [to the twelve], differentiated in fives, the five: wood, fire, earth, iron, and water, they revolve by sixty, along with a retinue of a hundred thousand minor obstructing spirits; the enemies of time, the year, month, day, and the defilements of the four seasons, and the five elements, and so forth, and the impurities and the emerging nine inauspicious omens (ngan dgu byung ba), the great malevolent spirits now accept and purify our defilements. {Thus, uttered; the substitute effigies (glud) are blessed by six mantras and six mudrās.}45 Kyai!”46

6.4. Crafting a Material Agent and Placating the Earth Spirits

“Who exists that does not listen to the speech of the Three Jewels—the buddha, dharma, and saṅgha? No one exists on a long travel path (skya ring) without going. No one exists in the falling rain without drinking. No one exists on a supportive ground without abiding. No one exists with a life of sustenance without cherishing it. No one exists with sincere speech without hearing it. No one exists who has rewards and gift offerings (rngan sbyin yas), without considering [giving them]. Regarding our body along with [that of] the sponsors—the flesh and blood are impure substances. Regarding the speech, it is the sound of an empty echo. Regarding the mind, like the wind it is free from substantiality (dngos po). Because of that, what is there for you all to do? [For] this substitute effigy (ngar glud), which is superior to the human, gather all [of these]: the five kinds of grain48 and the precious medicine, fine silks, various foods, the necessary wealth, completing the sense faculty (dbang po) and sense-spheres (skye mched).49 Regarding the body, it performs beautiful dance movements. Regarding the speech, it sings a pleasant song. Regarding the mind, it possesses friendly thoughts. Offer this substitute effigy that is more joyous than a human. This flesh substitute effigy (glud) of ours (and the sponsor retinue) is cast on the ground. The gods and the demons dwelling in the ground, receive this suitable great effigy (glud). {If it is for one’s own benefit, say for oneself; if it is for the benefit of another:}50 And, do no harm to this retinue (ʼkhor)! This blood substitute effigy is cast into water. The gods and demons dwelling in the water, receive this suitable great effigy. And, do no harm to this retinue! This bone substitute effigy is cast at the cliff. The gods and demons dwelling on the cliff receive this suitable great effigy. And, do no harm to this retinue! This substitute effigy of bodily heat (drod) is cast in the fire. The gods and the demons dwelling in the fire accept this suitable great effigy. And, do no harm to this retinue! This substitute effigy of breath is cast in the wind. The god and the demons dwelling in the wind accept this suitable great effigy. And, do no harm to this retinue! This substitute effigy of head-hair (skra) and pore-hair (ba sbu)51 is cast on wood. The gods and the demons dwelling in the wood accept this suitable great effigy. And, do no harm to this retinue! This substitute effigy of entrails is cast in the narrow passage (ʼphrang). The gods and demons dwelling in the narrow passage accept this suitable great effigy. And, do no harm to this retinue! This substitute effigy of the mind (sems) is cast into the sky (nam mkhaʼ). The gods and demons dwelling in the sky accept this suitable great effigy. And, do no harm to this retinue! Effigy masters (Glud bdag rnams) accept the substitute effigy. Offering Masters (Yas bdag rnams) take the offerings. Defilement Masters (Grib bdag rnams) accept the defilement. Accept this suitable great effigy. For us, along with the retinue of sponsors, let go of the hold and loosen the bindings; relax control and lift the suppression. Perform the pacifications of unfavorable conditions (mi mthun phyogs), such as great sudden misfortune (chag che) and anxiety (nyam nga).”52

6.5. Mantras and Casting the Defilements to the Defilement Master

“{Thus, offer the effigies inside the mdos vessel of the Defilement Master. Then, regarding casting out the farewell offering (rdzongs btab pa): Mix together the contaminants (dri ma), for example, the liquid (khu ba) that cleanses the patron by vase water (which is achieved with deity mantras), and the water that cleanses the mouth (kha bshal) of the patron, and the hair, and the nails. And, put in the egg shell, roasted flour of black grains of buckwheat and pulses, and a small black ritual cake (gtor ma), the substitute effigy (ngar mi), and squeezed dough (chang bu) and [recite]:} OṂ YA MĀNTA KA HŪṂ OṂ BHUR KUṂ MA HĀ PRĀ ṆĀ YA BHUR TSI BHURKI BI MA LE U TSUṢMA KRO DHA HUṂ PHAṬ. BADZRA BHUR KUṂ RI LI SHU THA RA SHA HUR SHE BI MA LE U TSUṢMA KRO DHA HŪṂ HŪṂ PHAṬ PHAṬ SWĀ HĀ. OṂ BADZRA SATWA HŪṂ. GRIB GNON NAG PO ZHI ZHI MAL MAL SWĀ HĀ. OṂ ĀḤ HŪṂ E E HOḤ A DUṂ Ā SWĀ HĀ. A DUṂ Ā SWĀ HĀ. ỌM E HO SHUDDHE. BAM HO SHUDDHE. RAṂ HO SHUDDHE. LAṂ HO SHUDDHE. WAṂ HO SHUDDHE. E BAṂ RAṂ LAṂ YAṂ SHUDDHE SHUDDHE A AḤ SWĀ HĀ. {Having casted (the mantras), thus:} Kyai! The mantradhara (sngags ʼchang) master and patron (yon mchod), now offer (rdzongs btab) the departing drink (gshegs skyems) to the Great Defilement Master along with his retinue. Roasted flour of black grains of buckwheat and pulses, and the black defilement ritual cake, the sacred substances (dam rdzas), and the substitute effigy (ngar mi), the provisions (lam chas), squeezed dough (chang bu) and various kinds of defiling (grib) substances are cast out (rdzongs btab) to you, Defilement Master. Furthermore, [we] cast out to you as a farewell offering (rdzongs btab) [the following]: Cast out sickness and evil spirits (dgon)! Cast out of idleness (dal) and infectious disease (rims)! Cast out of bad auguries (than) and omens (ltas)! Cast out quarrels (gyod) and gossip (kha smras)! Cast out slander (mi kha) and disputes (kha mchu)! Cast out bad dream omens (rmi ltas) and signs (mtshan)! Cast out negative mo and pra divination! Cast out enemy retribution (la yogs gshed)! Cast out previous karmic debt that must be atoned for (lan chags bu lon)! Cast out returning vengeance (sha khon skyin)! Cast out antagonisms (mi mthun) and obstacles (bar chad)! Cast out inauspicious star enemies (skag ngan gshed)! Cast out the sorcerer’s ritual dagger and [his] sorcery (byad phur rbod gtong)! Cast out ill intent (bsam ngan) and acrimonious unions (sbyor rtsub)! Cast out poisonous weapons (dug mtshon) [sent] by curses (dmod pas)! Cast out retribution (la yogs) and blame (kha nyes)! Cast out defilement (grib) and impurity (mi gtsang)! Cast out all unfavorable conditions (mi mthun phyogs kun)!”55

6.6. The Departing of the Defilement Master

“Now carry off what has been cast to you as the farewell offering. I offer the departing drink (gshegs skyems) for which now, depart! Swiftly, swiftly now depart! Without delay, quickly, now depart! {Thus, uttered. Regarding the path instruction: Place the mdos, turned outward, in kindle blazing brilliantly}. Kyai! Now, Grib kha57 along with the retinue, who are shown the path of departure—depart on that path! Beyond the direction of the setting sun, in the center of black darkness (mun pa nag po),58 is that blissful abode of the Great Defilement Master. The black castle (mkhar) of defilement sways back and forth (ldems se ldem). The black castle of defilement is a powerful fortress (rdzong re btsan). Within the inner region of the black castle of defilement, the fog of defilement becomes thicker and thicker. The thick darkness (mun pa) is overwhelmingly majestic (brjid re che). Great Defilement Master now depart inside of the castle (mkhar) of majestic darkness! Now depart, the four which have the faces [of animals]! The twelve abiders (gnas pa bcu gnyis), now depart to the palace of the five elements (wood, fire, soil, iron, and water) in the cardinal and intermediary directions! All the maleficent spirits (gdon) and obstructors (bgegs), now depart to each of your own pleasant (nyams dgaʼ ba) dwelling place! Regarding this abode of the mantradhara master: you all are not inclined (mi spro) to dwell [here]. Here, your abode does not exist. Here, there are no central depths of darkness. Here, there is no black castle of defilement. Here, there is no fog of defilement. The things that please you do not exist [here]. Therefore, like a cross (rgya gram) lifted by the wind, Defilement Master and your retinue, return (songs)59 to the abodes of each defilement master. Like being driven by karmic wind, return to the abodes of each defilement master. Like being greeted by frightening darkness, return to the abodes of each defilement master. Like masses of clouds dispersing in the sky, return to the abodes of each defilement master. How delightful, content, the abode of each! The Defilement Master, along with the defilements: to the men, transform [them]—to the right, bhyoḥ! To the women, transform [them]—to the left, bhyoḥ! To the youth (chung), transform [them]—to the front, bhyoḥ! To the negative thoughts of neighbors, bhyoḥ! To whatever obstructors (bgegs) encountered, bhyoḥ! Bhyoḥ! Repel! Transform! Samaya, hoḥ!”60

6.7. The Colophon—Chos kyi grags pa Establishes Legitimacy via Atiśa’s Precedent

“{Thus, having uttered: Carry the (mdos) without looking back, and point it away toward an inauspicious direction (phyogs ngan) or demon cutting (bdud gcod) [place] or in the direction of the five spirits (ʼdre) or toward the great river, or toward a large path, then dispatch [it]. The mdos bearer and his companions along with the dwelling place are cleansed by water from a vase. In accordance with that, this Ultimate Action of the Defilement Destroying Diamond: A Concise grib mdos ritual also, like the small grib mdos permitted to practice by Atiśa, also as the ultimate action of Blue-Green Bhurkuṃkūṭa, this as well, having been perceived not unsuitable as the ultimate action of Bhurkuṃkūṭa, was composed by the monk of the end times (dus mthaʼi dge slong) who lived (son pa) as a descendent of the ʼBri gung skyu ra [clan] in the upper region of Dbu, the mantradhara, vajradhara, Thugs kyi rdo rje (Chos kyi grags pa), on the first red rgyal61 (dmar poʼi rgyal ba dang po) of the first month (mchu zla) of the fire pig year (1647), in the supreme place Sra brtan rdo rje at Rtse ba estate (gzhis ka).}”62

7. Final Analysis: Blended Agencies Form the Functional Material

7.1. Construction Effort

7.2. Cognitive Correspondence

7.3. Text Creation

8. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Wylie Transliteration of the Ritual Text

[635] grib ʼjoms rdo rje pha lam gyi las mthaʼ grib mdos shin tu bsdus pa bzhugs so[636] ya mā ri na mo {note: grib ʼjoms rdo rje pha lam gyi las mthaʼ grib mdos bsdus pa ni/bra sran ʼbru nag dang tshig phye la zan nag brdzis te lcags snod la sogs paʼi nang du ri rab gru bzhi bang rim bzhi pa byas paʼi bang rim dang por mi nag po mgo la ʼphru nag po btsugs pa/rta nag zhon cing klad na bya nag lding ba/rol du khyi nag khrid pa/gos nag gyon pa/lag na dar nag ʼphyar ba/rgyab tu bya mo nag mos sgong skogs khur ba bya/bang rim gnyis paʼi phyogs bzhir mi gzugs bya sprul phag sbal paʼi mgo can bzhi bzhag/bang rim gsum par shar stod stag sogs rang rang ʼbyung baʼi mdog gam thams cad nag po byas la bkod/bang rim bzhi par/mar me/bshos bu/chang bu/ril bu/ong skyu rnams bsgrub byaʼi lo grangs dang mnyam pa thams cad kha dog nag po byas la rang gi mdun du gzhi ma nag poʼi steng du bsham/snod gcig tu braʼo/ram bu/sbang ma/g.yer ma/rus pa sogs mi khaʼi rdzas bsag/snod gcig tu bsgrub byaʼi lo grangs dam mnyam paʼi ngar glud chang bu mtheb skyu rnams bsham/gzhan yang ya mā ri dang sme brtsegs la dbul gtor/mchod pa/sman rak/rol mo/g.yab dar nag po sogs ʼdu bya/rang ya[637] mā rir gsal baʼi thugs kar sme brtsegs bskyed/bum pa gzhung ltar bcas la sme brtsegs bskyed bzlas sogs grib ʼjoms rdo rje pha lam ltar byas rjes g.yab dar nag po bsgrub byaʼi mgo la bskor zhing/ya mā ri sogs kyi bden stobs brjod nas grib bdag bkug nas gzugs la bstim/de nas dbyangs kyis gyer ba ni} hūṃ/nga ni ʼjam dpal gshin rjeʼi gshed/nga ni khro rgyal sme ba brtsegs/rtog ʼjoms rgyal po he ru kaḥ/snang srid dregs pa thams cad dang/grib bdag tshogs rnams nga la nyon/kyai/nyi ma nub phyogs pha gi na/mun pa nag poʼi gting rum na/grib mkhar nag poʼi nang shed na/grib bdag rgyal po chen po ste/sku mdog nag po mun paʼi mdog/ʼog tu grib rta nag po zhon/steng du grib bya nag po lding/grib gos nag po lus la gyon/grib dar nag po lag na ʼphyar/grib ʼphru nag po mgo la btsugs/grib snod sgong nag rgyab tu khur/grib khyi nag po rol tu khrid/gnas[638] ʼdir ʼbod do dam la ʼdu/grib bdag chen po grib longs shog/kyai/de yi bkaʼ nyan las byed bzhi/ʼdod chags bya nag mgo bo can/zhe sdang sbrul nag mgo bo can/gti mug phag nag mgo bo can/ma rig sbal nag mgo bo can/khyed rnams grib kyi bdag po ste/gnas ʼdir ʼbod do dam la ʼdus/grib kyi bdag po grib longs shig/kyai/grib bdag rgyal po chen po dang/de yi bkaʼ nyan blon po bzhi/khyed rnams grib kyi bdag po yin/khyed rnams gzhi byes bdag po yin/bdag dang rgyu sbyor ʼkhor bcas la/zas grib gos grib nor gyi grib/gson grib shi grib ro yi grib/dam nyams grib dang rme grib dang/mdze grib ʼkhon grib yug grib dang/lha klu gnyan sogs sde brgyad grib/rnam rtog ʼkhrul baʼi grib la sogs/dug gsum dug lnga las kyi grib/nyon mongs sngon las ʼphral rkyen grib/de ʼdraʼi grib dang nyes paʼi tshogs/grib bdag rnams kyis da longs la/bdag cag grib rnams sangs gyur cig/kyai/grib bdag chen poʼi bkaʼ ʼkhor ni/shar stod stag gi mgo bo can/nub stod spreʼuʼi mgo bo can khyod gnyis bdun zur dgra[639] gshed de/ʼkhor du bgegs phran ʼbul gyis bskor/khyed rnams grib kyi bdag po ste/bdag cag grib rnams da longs la/bdun zur gnod pa zhi bar mdzod/shar smad yos kyi mgo bo can/nub smad bya yi mgo bo can/khyed gnyis bye bral dgra gshed de/ʼkhor du bgegs phran ʼbum gyis bskor/khyed rnams grib kyi bdag po ste/bdag cag grib rnams da longs la/bye bral gnod pa zhi bar mdzod/lho stod sbrul gyi mgo bo can/byang stod phag gi mgo bo can/khyed gnyis ʼkhon paʼi dgra gshed de/ʼkhor du bgegs phran ʼbul gyis bskor/khyed rnams grib kyi bdag po ste/bdag cag grib rnams da longs la/ʼkhon gyi gnod pa zhi bar mdzod/lho smad rta yi mgo bo can/byang smad byi baʼi mgo bo can/khyed gnyis ru gcod dgra gshed de/ʼkhor du bgegs phran ʼbum gyis bskor/khyed rnams grib kyi bdag po ste/bdag cag grib rnams da longs la/ʼkhon gyi gnod pa zhi bar mdzod/shar lho ʼbrug gi mgo bo can/nub byang khyiʼi mgo bo can/khyed gnyis thog rdzis dgra gshed de/ʼkhor du bgegs phran ʼbum gyis[640] bskor/khyed rnams grib kyi bdag po ste/bdag cag grib rnams da longs la/thog rdzis gnod pa zhi bar mdzod/lho nub lug gi mgo bo can/byang shar glang gi mgo bo can/khyed gnyis phung gyod dgra gshed de/ʼkhor du bgegs phran ʼbum gyis bskor/khyed rnams grib kyi bdag po ste/bdag cag grib rnams da longs la/phung gyod gnod pa zhi bar mdzod/bdag cag rgyu sbyor ʼkhor bcas kyi/grib dang mi gtsang gnod pa dang/dgra gshed skag ngan sbyor ba rnams/gdon chen gnas pa bcu gnyis po/da lta longs la zhi bar mdzod/de la shing me sa lcags chu/lnga lngar phye ba drug cus bskor/ʼkhor du bgegs phran ʼbum dang bcas/lo zla zhag dus dgra gshed dang/dus bzhi khams lngaʼi grib la sogs/mi gtsang ngan dgu byung ba rnams/gdon chen rnams kyis da longs la/bdag cag grib rnams sangs gyur cig/{note: ces brjod/glud rnams sngags drug phyag rgya drug gis byin gyis brlabs la}/kyai/sangs rgyas chos tshogs mchog gsum gyi/bkaʼ la mi nyan su zhig yod/skya ring lam la mi ʼgro med/ʼbab pa chu la mi ʼthung med/brtan paʼi gzhi la mi gnas med/[641] ʼtsho baʼi srog la mi gces med/drang poʼi tshig la mi nyan med/rngan sbyin yas la mi sems med/bdag cag rgyu sbyor bcas pa yi/lus ni sha khrag mi gtsang rdzas/ngag ni brag cha stong paʼi sgra/yid ni rlung ltar dngos po bral/des ni khyod rnams ci byar yod/mi las lhag paʼi ngar glud ʼdi/ʼbru sna lnga dang rin chen sman/dar zab zas sna mgo dguʼi nor/kun bsdus dbang po skye mched tshang/lus ni mdzes paʼi gar stabs bsgyur/ngag ni snyan paʼi glu dbyangs len/yid ni mdzaʼ baʼi blo sems can/mi las dgaʼ baʼi glud ʼdi ʼbul/bdag cag rgyu sbyor ʼkhor bcas kyi/sha yi glud ʼdi sa la gtong/sa la gnas paʼi lha ʼdre rnams/mthun paʼi glud chen ʼdi bzhes la/{note: rang don yin na bdag la zhes dang/gzhan don yin na}/ʼkhor ʼdir gnod pa ma byed cig/khrag gi glud ʼdi chu la gtong/chu la gnas paʼi lha ʼdre rnams/mthun paʼi glud chen ʼdi bzhes la/ʼkhor ʼdir gnod pa ma byed cig/rus paʼi glud ʼdi brag la gtong/brag la gnas paʼi lha ʼdre rnams/mthun paʼi glud chen ʼdi bzhes la/ʼkhor ʼdir gnod pa ma byed cig/[642] drod kyi glud ʼdi me la gtong/me la gnas paʼi lha ʼdre rnams/mthun paʼi glud chen ʼdi bzhes la/ʼkhor ʼdir gnod pa ma byed cig/dbugs kyi glud ʼdi rlung la gtong/rlung la gnas paʼi lha ʼdre rnams/mthun paʼi glud chen ʼdi bzhes la/ʼkhor ʼdir gnod pa ma byed cig/skra dang ba sbuʼi glud ʼdi shing la gtong/shing la gnas paʼi lha ʼdre rnams/mthun paʼi glud chen ʼdi bzhes la/ʼkhor ʼdir gnod pa ma byed cig/nang khrol glud ʼdi ʼphrang la gtong/ʼphrang la gnas paʼi lha ʼdre rnams/mthun paʼi glud chen ʼdi bzhes la/ʼkhor ʼdir gnod pa ma byed cig/sems kyi glud ʼdi nam mkhar gtong/nam mkhar gnas paʼi lha ʼdre rnams/mthun paʼi glud chen ʼdi bzhes la/ʼkhor ʼdir gnod pa ma byed cig/glud bdag rnams kyis glud bzhes shig/yas bdag rnams kyis yas khyer cig/grib bdag rnams kyis grib longs shig/mthun paʼi glud chen ʼdi bzhes la/bdag cag rgyu sbyor ʼkhor dang bcas/bzung ba thong la bcings pa khrol/bsdams pa lhod la mnan pa khyog/chag che nyam nga la sogs paʼi/mi mthun phyogs rnams zhi[643] bar mdzod/{note: ces grib bdag gi mdos snod kyi nang du glud rnams ʼbul lo/de nas rdzongs btab pa ni/lha sngags kyis bsgrubs paʼi bum chus bsgrub bya bkrus paʼi khu ba dang/bsgrub byaʼi kha bshal baʼi chu dang/skra dang sen mo sogs dri ma bsres pa dang/bra sran ʼbru nag tshig phye dang/gtor chung nag po/ngar mi/chang bu rnams sgong skogs su blugs shing}/oṃ ya mānta ka hūṃ oṃ bhur kuṃ ma hā prā ṇā ya bhur tsi bhurki bi ma le u tsuṣma kro dha hūṃ phaṭ/badzra bhur kuṃ ri li shu tha ra sha hur she bi ma le u tsuṣma kro dha hūṃ hūṃ phaṭ phaṭ/swā hā/oṃ badzra satwa hūṃ/grib gnon nag po zhi zhi mal mal swā hā/oṃ āḥ hūṃ e e hoḥ a huṃ ā swā hā/a duṃ ā swā hā/oṃ e ho shuddhe/baṃ ho shuddhe/raṃ ho shuddhe/laṃ ho shuddhe/yaṃ ho shuddhe/e baṃ raṃ laṃ yaṃ shuddhe shuddhe a aḥ swā hā/{note: zhes btab cing}/kyai/grib bdag chen po ʼkhor bcas la/sngags ʼchang bdag dang yon mchod kyis/de ring gshegs skyems rdzongs btab bo/bra sran ʼbru nag tshig phye dang/grib gtor nag po dam rdzas dang/ngar mi lam chas chang bu dang/grib rdzas rnam pa sna tshogs kyis/grib bdag khyod la rdzongs btab bo/gzhan yang khyod la rdzongs btab la/nad dang gdon gyi rdzongs btab bo/dal dang[644] rims kyi rdzongs btab bo/than dang ltas ngan rdzongs btab bo/gyod dang kha smras rdzongs btab bo/mi kha kha mchuʼi rdzongs btab bo/rmi ltas mtshan ngan rdzongs btab bo/mo pra rtsis ngan rdzongs btab bo/la yogs gshed kyi rdzongs btab bo/lan chags bu lon rdzongs btab bo/sha ʼkhon skyin gyi rdzongs btab bo/mi mthun bar chad rdzongs btab bo/skag ngan gshed kyi rdzongs btab bo/byad phur rbod gtong rdzongs btab bo/bsam ngan sbyor rtsub rdzongs btab bo/dug mtshon dmod pas rdzongs btab bo/la yogs kha nyes rdzongs btab bo/grib dang mi gtsang rdzongs btab bo/mi mthun phyogs kun rdzongs btab bo/rdzongs su btab bo da khyer cig/gshegs skyems ʼbul gyi da gshegs shig/rings par rings par da gshegs shig/ma ʼgor myur du da gshegs shig/{note: ces brjod/lam bstan pa ni/mdos kha phyir bsgyur dpal ʼbar sbar la btsugs}/kyai/da ni gshegs paʼi lam bstan gyi/grib kha ʼkhor bcas lam der gshegs/nyi ma nub phyogs pha gi na/mun pa nag poʼi klong dkyil na/grib bdag chen poʼi gnas de bde/grib mkhar nag po ldems se ldem/grib mkhar nag po rdzong[645] re btsan/grib mkhar nag poʼi nang shed na/grib kyi na bun thibs se thib/mun pa thibs pa brjid re che/brjid ldan mun paʼi mkhar nang na/grib bdag chen po da gshegs shig/gdong can bzhi po da gshegs shig/phyogs mtshams shing me sa lcags chu/ʼbyung ba rnam lngaʼi pho brang na/gnas pa bcu gnyis da gshegs shig/rang rang bzhugs gnas nyams dgaʼ bar/gdon bgegs thams cad da gshegs shig/sngags ʼchang bdag gi gnas ʼdi ni/khyed cag bzhugs pa dang mi spro/ʼdi na khyod kyi gnas ma mchis/mun paʼi klong rum ʼdi na med/grib mkhar nag po ʼdi na med/grib kyi na bun ʼdi na med/khyod la dgyes paʼi yo byad med/de bas grib bdag ʼkhor dang bcas/rgya gram rlung gis bteg pa ltar/grib bdag so soʼi gnas su songs/las kyi rlung gis ded pa ltar/grib bdag so soʼi gnas su songs/ʼjigs paʼi mun pas bsus pa ltar/grib bdag so soʼi gnas su songs/nam mkhar sprin tshogs dengs pa ltar/grib bdag rang rang gnas su gshegs/bdeʼo skyid do rang gi gnas/grib bdag[646] grib dang bcas pa rnams/pho la bsgyur ro g.yas su bhyoḥ mo la bsgyur ro g.yon du bhyoḥ chung la bsgyur ro thad du bhyoḥ khyim mtshes bsam pa ngan la bhyoḥ gang dang ʼphrad paʼi bgegs la bhyoḥ bhyoḥ zlog bsgyur ro sa ma ya hoḥ/{note: zhes brjod cing mdos phyi mig mi lta bar khyer la phyogs ngan nam bdud gcod dam/ʼdre lngaʼi phyogs sam/chu chen nam/lam chen por kha phar la bstan la bskyal/mdos skyel mi dang rang ʼkhor gnas khang bcas pa bum chus khrus byaʼo/de ltar grib ʼjoms rdo rje pha lam gyi las mthaʼ grib mdos bsdus pa ʼdiʼang/sme brtsegs ljang sngon gyi las mthar jo bo rjes kyang grib mdos chung ngu mdzad gnang ba ltar ʼdiʼang sme brtsegs kyi las mthar mi rung ba ma yin par mthong nas/dbur stod ʼbri gung skyu raʼi rigs su son pa dus mthaʼi dge slong sngags ʼchang rdo rje ʼdzin pa thugs kyi rdo rjes/me phag mchu zlaʼi dmar poʼi rgyal ba dang por/rtse ba gzhis ka sra brtan rdo rjeʼi gnas mchog tu sbyar baʼo/sarba manga laṃ}

| 1 | Kimmerer (2013) specifically shows how some Indigenous American languages contain verbal constructions (thus implicating that this thing “does” something) related to objects that in English are relegated to inanimacy; e.g., the Ojibwe language contains a verbal construction “to be a bay” (pp. 54–55). |

| 2 | Barad’s ideas of entanglement and intra-action intend to collapse the categories of natural realism and cultural construction, dissolving any apparent, objective dualities into interdependent (i.e., not solely dependent on human perspective or language) practices of boundary reification. Interestingly similar to Buddhist ideas of dependent arising (Skt. pratītyasamutpāda), as noted by Garrison (2021), Barad argues that “phenomena are the ontological inseparability of agentially intra-acting components”. In this way, there is no singular, discrete subject acting upon an object, only emerging entanglement of agencies (Barad 2007, pp. 33–34). Relatedly, note the complex discourse within the Buddhist tradition itself on reality and perception, e.g., emptiness (śūnyatā) and subject/object non-duality. |

| 3 | See especially pp. 21, 222–23, 140–41, 153–54. |

| 4 | See especially pp. 18–20. |

| 5 | Blondeau ([1990] 2022) points out that mdos rites are employed even more generally for apotropaic purposes (p. 9). |

| 6 | Orosz’s dissertation is written in Hungarian; however, an English outline is available (Orosz 2019b). |

| 7 | For example, Nebesky-Wojkowitz ([1956] 1996). |

| 8 | For a more thorough treatment of this differentiation, see Orosz (2019a) and Blondeau ([1990] 2022). |

| 9 | For a discussion of the possible differences among these variantly termed rites, see Blondeau ([1990] 2022). |

| 10 | See Kalsang Norbu Gurung (2009) for a discussion of the role of Confucius in Bon sources. |

| 11 | See Ramble’s (2019) website: https://kalpa-bon.com/texts/mgo-gsum/srid-pa-gto-mgo-gsum, accessed on 12 December 2024. |

| 12 | Douglas ([1966] 1984), especially pp. 36–41. Schicklgruber (1992), suggesting the synonym “chaos”, also describes grib as designating something outside the normal social and religious order (p. 723). |

| 13 | For a discussion on Tibetan discourses (particularly Sangs rgyas gling pa) on the cause of grib, see Orosz (2019a), pp. 164–69. Also see Epstein (1977), pp. 89–95; Lichter and Epstein (1983), pp. 242–46; Millard (2002), pp. 241–44; and Schicklgruber (1992), pp. 723, 728, 733–34. |

| 14 | A similar figure is described by Karmay ([1997] 2009) in the context of a bla bslu ritual from Padma gling pa’s Bla bslu tshe ʼgugs (p. 335). |

| 15 | The ritual text appears in Chos kyi grags pa Gsung ʼbum vol. 12, pp. 635–46 (Chos kyi grags pa 1999a). |

| 16 | For further details on the life of Chos kyi grags pa, see Sobisch (2020). Both lineages continue today. The current Che tshang (07), Dkon mchog bstan ʼdzin kun bzang ʼphrin las lhun grub (b. 1946) who is the thirty-seventh throne-holder of the sect’s lineage, presides over the ʼBri gung Bkaʼ brgyud Institute in Dehradun, India. Meanwhile, the current Chung tshang (08), Bstan ʼdzin chos kyi snang ba (b. 1942), who is the thirty-sixth throne-holder, remains in the Tibetan Autonomous Region. |

| 17 | |

| 18 | See FitzHerbert (2018) on Chos kyi grags pa’s role in war magic. |

| 19 | Buddhist Digital Resource Center: MW22082, pp. 635–46. See Appendix A for Wylie transliteration. |

| 20 | Volume 28 in (Chos kyi grags pa 1976–1980) BDRC: MW20578, pp. 41–51. The preface of volume twenty-seven names this section the ʼJam dpal nag po Yang zab thugs kyi tshal pa revelations. The preface of volume twenty-eight gives the title ʼJam dpal nag po Thugs kyi yang zhun (a.k.a ʼJam dpal nag po Thugs kyi nying khu). In another version of the Rin chen gter mdzod (Chos kyi grags pa 2007–2008); BDRC: MW1KG14, this rite is found in a section called the Zab rgya gsum pa ʼJam dpal nag po (volume 18, pp. 409–19); this is noted as the Sangs rgyas gling pa section classified as the wrathful version of Mañjuśrī body Mahāyoga sgrub thabs. Arguillère (2024) describes this deity as a “one-faced, two-armed dark blue figure, with a club ending in a skull in his right hand and a skull-cup in the left”. During my fieldwork, interlocutors have relayed to me that the phrase “rdo rje pha lam” is commonly associated with the Yang zlog meʼi spu gri Yamāntaka, as is attested in many text titles. However, this Yamāntaka in the Sangs rgyas gling pa text is clearly iconographically different from the main Yang zlog Yamānaka who has three faces and six hands. More research must be conducted in order to unravel these associations. |

| 21 | This line appears in the Tibetan and English versions as follows: ʼJam mgon kong sprul Blo gro mthaʼ yas (1973), Gter ston brgya rtsa’i rnam thar, pp. 221–22; ʼJam mgon kong sprul Blo gro mthaʼ yas (2011), The Hundred Tertöns (2011), p. 156. |

| 22 | |

| 23 | BDRC: MW3KG218, (Chos kyi grags pa 2021/2022a) vol. 41 (overall text volume number) pp. 209–22; (Chos kyi grags pa 2021/2022b) vol. 57 (overall text volume number) pp. 543–54. |

| 24 | This refers to the loose-leaf pages of the Tibetan-style dpe cha. Each side of a typical leaf in Chos kyi grags pa Gsung ʼbum (BDRC: MW22082) contains six lines with approximately seventy characters per line (each orthographic stack counted as one character, excluding spaces and punctuation marks). |

| 25 | See, for example, the tripartite structures (1. preliminaries [includes self-visualization, invitation to guests, offerings, etc.]; 2. principal section [includes explanation, exorcism, reversal, etc.]; and the 3. concluding action delineated in Kelényi (2012), pp. 17–18; and also, Beyer (1978) describes a “thread-cross” rite (1. preliminaries; 2. ritual [includes self-generation, front-generation, offerings/praises/gtor ma, dispatching substitutes, averting with the strength of the truth etc.]; and the 3. concluding acts (pp. 324–59). Likewise, Orosz’s (2019b) comparative study identifies seven common units in the mdos rituals he examines: 1. a list of ritual ingredients; 2. purification of the offerings; 3. summoning the harmful entities; 4. dedication of the offerings; 5. transferring the diseases onto the effigy; 6. gift of the dharma; and 7. sending the harmful forces home. |

| 26 | According to interlocutors, this small gtor ma is made by flattening a round piece of dough and placing a spherical gtor ma in the middle. |

| 27 | Translated from Chos kyi grags pa Gsung ʼbum (Chos kyi grags pa 1999a), pp. 635–36.6. |

| 28 | The ritual he cites is titled Gnam chos bdud rtsi ʼkhyil paʼi las tshogs lto ʼgong dbul sri dkar baʼi man ngag zhes bya ba bzhugs so (Unknown n.d.; Nebesky-Wojkowitz [1956] 1996, p. 590). A digital copy of this text can be found in the digital collections of the Leiden University Libraries (https://digitalcollections.universiteitleiden.nl/view/item/328711, accessed on 12 December 2024). |

| 29 | Orosz (2019a) shows that similar rituals require these four animal-headed forms that represent what he terms “tudati mérgek” (mental poisons). These are often part of the enumerations of the three poisons (dug gsum) or the five afflictions (nyon mongs lnga); here, interestingly, the delusion and ignorance are separate, whereas in other lists, one is usually listed rather than the other. Millard (2005/2006) describes ma rig pa as the fundamental ignorance that drives saṃsāra which leads to the three “mental poisons” of gti mug, ʼdod chags, and zhe sdang (p. 9). Orosz (2019a) also notes that the animal corresponding to each of these poisons sometimes varies and some rites instruct to make female and male versions of each (pp. 188–92). |

| 30 | See Feldt (2012) on the “fantastical” and religion, and see Mikles and Laycock (2021) on the monstrous and religion, particularly in the context of reinforcing categorical norms (especially, pp. 3–16). |

| 31 | I asked interlocutors whether the increased number of dough pieces corresponding to age indicated that individuals who were older had more “grib” to eradicate, but this does not seem to be the case. Rather, as noted above, it is related to forming a connection through aspects of one’s identity at the time of ritual performance. |

| 32 | Perhaps this indicates Bhurkuṃkūṭa and/or other deities in the visualization sequence not explicitly listed here but present in the other texts mentioned in the previous line. |

| 33 | Translated from Chos kyi grags pa Gsung ʼbum (Chos kyi grags pa 1999a), pp. 636.6–37.2. |

| 34 | See Lokesh Chandra (2000), vol. 2, pp. 573–75. Based on Chos kyi grags pa’s description of Bhurkuṃkūṭa in his Gsung ʼbum (see note 35), he is likely the second form listed in this dictionary. However, the mantra from the text translated in this article more closely matches the third type’s dhāraṇī. Also, see Jeff Watt’s (2025) entry on the Himalayan Art Resources website (https://www.himalayanart.org/search/set.cfm?setID=564, accessed on 12 December 2024). |

| 35 | Chos kyi grags pa’s text entitled Rdo rje rnam ʼjoms dang sme ba rtsegs paʼi lo rgyus bsdus (Chos kyi grags pa 1999b) provides a fascinating history of the Bhurkuṃkūṭa teachings, beginning with a tale of two male and female vicious rudras. These rudras were killing and eating all people in the land. In response to their unwholesome activity, the Buddha emanates a son for them, and that son eventually kills his two parental rudras. The teaching is thus related to cleansing the grib of the son’s parricide (vol. 5, pp. 264–65). The lineage is given as Rdzogs paʼi sangs rgyas (Buddha), Lag na rdo rje (Vajrapāṇi), Atiśa, Nag tsho, Rong pa phyag sor, Bya ʼdul ba ʼdzin pa, Chos kyi byang chub, Mkhan po Zul phu pa, Slob dpon Dkon mchog seng ge, Mkhan chen Tshul rin, Bla ma Dar ma bzang po, Gzhon nu rgyal mtshan, Rgyal mtshan don grub, Gtsang pa rin rgyal, Bya btang Boddhisattva, ʼJam dbyangs rin grags, Bsod nams lha dbang, Ngag dbang chos grags, Chos rje byams pa ba, Mtshungs med Rin chen dpal, Drin can Buddha Ratna, and Dharmakīrti (Chos kyi grags pa) (vol. 5, pp. 266–67). The subsequent text, Rnam ʼjoms dang sme brtsegs kyi sgrub thabs rjes gnang khrus chog shin tu bsdus pa (Chos kyi grags pa 1999c), gives the following description of the deity: His middle face and body are dark green. His right face is blue and his left face is white (three in total). His nine eyes blaze like the fires of the end times. He has twelve clenching fangs. An orange mass of eyebrows, mustache, and beard [hair] flows upwards; his two feet are stretched out and all limbs are adorned by emanations. His first two hands are crossed making a wrathful gesture at the heart. In his remaining hands, he holds in the second right, a golden rdo rje; in the third right, an iron hook; in the second left, a dril bu; and in the third left, a noose (vol. 5, pp. 273–74). The lineage list here (vol. 5, p. 283) parallels the one found in the previous text. More research must be conducted to determine the exact relationships between these texts and the one examined in this article. |

| 36 | |

| 37 | |

| 38 | Nebesky-Wojkowitz ([1956] 1996), p. 307 identifies the Mun pa nag po as the mother of the King of the Masters of Pollution (Grib bdag rgyal po). This could also mean something more metaphorical like in the hidden depths (gting rum) of black darkness (mun pa nag po). |

| 39 | Translated from Chos kyi grags pa Gsung ʼbum (Chos kyi grags pa 1999a), pp. 637.2–38.2. |

| 40 | Interlocutors relayed that these defilements should be understood as impurities caused by the ill intent of others. For example, if someone were to attempt black magic by contaminated clothes or food. |

| 41 | Interlocutors relayed that this is usually a reference particularly to killing someone of familial relation, perhaps a misspelling of dme. Otherwise, it could be greed (rme) defilement, but given the context, the former is more likely. |

| 42 | Translated from Chos kyi grags pa Gsung ʼbum (Chos kyi grags pa 1999a), pp. 638.3–38.6. |

| 43 | Ramble (2019) translates this as the “Seventh-year edge” (https://kalpa-bon.com/texts/mgo-gsum/srid-pa-gto-mgo-gsum, accessed on 12 December 2024), the seven years away from your birth year that is deemed inauspicious (counted with the initial year as one). These astrological antagonisms are illustrated in Cornu’s Tibetan Astrology (Cornu 2002, p. 73); the twelve astrological signs are placed in a circle, lines connecting those appearing across from one another (which are antagonistic). Also note, the seven must be calculated by counting the first “edge” as one. Each matches the pairs enumerated in this section. Also see Gyurme Dorje (2001), pp. 229–31. |

| 44 | This is a phrase indicating an inauspicious relationship, seemingly related to specific antagonistic time periods. Gyurme Dorje (2001, p. 231) translates dgra gshed as “adversarial circumstances” in the context of divinations of obstacle years described in the White Beryl by the Fifth Dalai Lama’s regent Sangs rgyas Rgya mtsho (1653–1705). |

| 45 | Interlocutors relayed that the mantras are general tantric mantras that any sect’s practitioner would utilize, whereas the mudrā used here is specific to the ʼBri gung Bkaʼ brgyud tradition. For purification one would recite OṂ SWA BHĀ WA SHUDDHAḤ SARBA DHARMAḤ SWA BHĀ WA SHU DDHONYAHAṂ, making a hollow cavity with one’s palms and affixing them to one’s heart. |

| 46 | Translated from Chos kyi grags pa Gsung ʼbum (Chos kyi grags pa 1999a), pp. 638.6–40.6. |

| 47 | A similar Bon gto ritual that uses an effigy of a three-headed man (Srid pa gto mgo gsum), translated by Charles Ramble (2019) on the website Kalpa Bon, enumerates directions with corresponding animals. Interestingly, here the instructions do not highlight the same opposite pairs as the ritual above, and some sections show the animal–human hybrids singly averting obstacles. |

| 48 | The Dung dkar tshig mdzod chen mo (Dung dkar blo bzang ʼphrin las 2002), p. 1568 enumerates at least two lists: barley (nas), rice (ʼbras), wheat (gro), pulses (sran ma), sesame (til), or alternatively wheat (gro), barley (nas), pulses (sran ma), buckwheat (bra bo), unhusked grain (so ba). |

| 49 | The six sense faculties (dbang po drug) are roughly equivalent to the five familiar senses (seeing, hearing, smelling, tasting, and touching), adding a special mind-sense. The sense-spheres then are those faculties and that which is perceived by each of them, i.e., the seeing faculty of the eye correlates to visual form, and so forth. |

| 50 | Translated from This is another component that suggests this ritual is often employed privately, simply for one person (either the performer himself) or an individual (or small group of individuals like an immediate family) who approaches a ritualist for help. |

| 51 | Most likely a misspelling of ba spu. |

| 52 | Translated from Chos kyi grags pa Gsung ʼbum (Chos kyi grags pa 1999a), pp. 640.6–43.1. |

| 53 | On Tibetan magic, see Bailey and Wenta (2024). |

| 54 | If something is dngos po, a thing or entity, it exists not because it inherently exists but because it has the ability to perform a function (don byed nus pa). See Dung dkar tshig mdzod chen mo (Dung dkar blo bzang ʼphrin las 2002), p. 756. |

| 55 | Translated from Chos kyi grags pa Gsung ʼbum (Chos kyi grags pa 1999a), pp. 643.1–44.4. |

| 56 | Translated from Douglas ([1966] 1984), especially pp. 115–29. |

| 57 | Perhaps a scribal error (grib bdag), or alternatively a name alluding to the consumption of defilement (“Defilement Mouth”). |

| 58 | Here, this context seems more like a place rather than his mother’s womb (as mentioned above in the context of Nebesky-Wojkowitz’s translation of this term in relation to the grib bdag). |

| 59 | If this means “to leave/go/return” (ʼgro), it must be a misspelling of song. An alternate possibility is that this is a misspelling of the past form, which is also song. Otherwise, this could be an imperative of bsang ba meaning “to clear” but this does not fit the structure of the simile very well, nor the previous patterns of commands. |

| 60 | Translated from Chos kyi grags pa Gsung ʼbum (Chos kyi grags pa 1999a), pp. 644.4–46.2. |

| 61 | The days of the months in the Tibetan lunar calendar are divided into subsections. The first rgyal is either the 3rd or 18th day of the month, according to whether the moon is waxing (the beginning of the month) or waning (the end of the month). Dictionaries mark the white as the waxing and the black as waning; however, informants have indicated this red is the waning, which here corresponds to the 18th. Further research must be conducted to determine the calendrical system specifically used here. |

| 62 | Translated from Chos kyi grags pa Gsung ʼbum (Chos kyi grags pa 1999a), pp. 646.2–46.5. |

| 63 | I use “perceived” intentionally here to suggest complexity in cognitive formation of categories. For example, see Lakoff (1987) (who builds upon previous theories such as the prototype theory of Eleanor Rosch and the “family resemblances” of Ludwig Wittgenstein) on the embodied and experiential basis of categorical formation that challenges the objectivist view of categorization based in absolute similarity. For a general evolutionary cognitive science discussion on human cataloguing systems, see Boyer (2001), who argues that human brains are primed for certain templates that govern reasonable inferences about items of a category. Both approaches suggest that humans possess systematic ways of categorizing items, concepts, experiences, etc., thereby creating frameworks for understanding and acting in the world. |

| 64 | |

| 65 | See Gell (1998), especially pp. 21, 153–54. Also see Diemberger (2012), who specifically discusses the Tibetan book and distributed personhood. |

References

- Arguillère, Stéphane. 2024. Yamāntaka Among the Ancients: Mañjuśrī Master of Life in Context. Revue dʼEtudes Tibétaines 68: 294–380. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, Cameron, and Aleksandra Wenta, eds. 2024. Tibetan Magic: Past and Present. New York: Bloomsbury. [Google Scholar]

- Barad, Karen. 2007. Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett, Robert. 2012. Notes on Contemporary Ransom Rituals in Lhasa. In Revisiting Rituals in a Changing Tibetan World. Edited by Katia Buffetrille. Leiden: Brill, pp. 273–374. [Google Scholar]

- Bentor, Yael. 1994. Tibetan Relic Classifications. In Tibetan Studies: Proceedings of the 6th Seminar of the International Association for Tibetan Studies, Fagernes, 1992. Edited by Per Kvaerne. Oslo: The Institute for Comparative Research in Human Culture, vol. 1, pp. 16–30. [Google Scholar]

- Beyer, Stephan. 1978. The Cult of Tārā: Magic and Ritual in Tibet. Berkeley & Los Angeles: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Blondeau, Anne-Marie. 2004. The mKhaʼ klong gsang mdos: Some questions on ritual structure and cosmology. In New Horizons in Bon Studies (Bon Studies 2). Edited by Samten Gyeltsen Karmay and Yasuhiko Nagano. Delhi: Saujanya Publications, pp. 249–87. [Google Scholar]

- Blondeau, Anne-Marie. 2022. Some preliminary questions regarding the mdos rituals. Translated by Urmila Nair. European Bulletin of Himalayan Research 59. First published 1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1977. Outline of a Theory of Practice. Translated by Richard Nice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Boyer, Pascal. 2001. Religion Explained: The Evolutionary Origins of Religious Thought. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Chandra, Lokesh. 2000. Dictionary of Buddhist Iconography. New Delhi: International Academy of Indian Culture and Aditya Prakashan, vol. 2, pp. 325–679. [Google Scholar]

- Chos kyi grags pa. 1976–1980. Grib ʼjoms rdo rje pha lam gyi las mthaʼ grib mdos shin tu bsdus pa. In Rin chen gter mdzod chen mo. Compiled by ʼJam mgon kong sprul Blo gro mthaʼ yas. Paro: Ngodrup and Sherab Drimay, vol. 28, pp. 41–51, BDRC: MW20578. [Google Scholar]

- Chos kyi grags pa. 1999a. Grib ʼjoms rdo rje pha lam gyi las mthaʼ grib mdos shin tu bsdus pa. In Chos kyi grags pa Gsung ʼbum. Kulhan: Drikung Kagyu Institute, vol. 12, pp. 635–46, BDRC: MW22082. [Google Scholar]

- Chos kyi grags pa. 1999b. Rdo rje rnam ʼjoms dang sme ba rtsegs paʼi lo rgyus bsdus. In Chos kyi grags pa Gsung ʼbum. Kulhan: Drikung Kagyu Institute, vol. 5, pp. 261–68, BDRC: MW22082. [Google Scholar]

- Chos kyi grags pa. 1999c. Rnam ʼjoms dang sme brtsegs kyi sgrub thabs rjes gnang khrus chog shin tu bsdus pa. In Chos kyi grags pa Gsung ʼbum. Kulhan: Drikung Kagyu Institute, vol. 5, pp. 269–84, BDRC: MW22082. [Google Scholar]

- Chos kyi grags pa. 2007–2008. Grib ʼjoms rdo rje pha lam gyi las mthaʼ grib mdos shin tu bsdus pa. In Rin chen gter mdzod chen mo. Compiled by ʼJam mgon kong sprul Blo gro mthaʼ yas. New Delhi: Shechen Publications, vol. 18, pp. 409–19, BDRC: MW1KG14. [Google Scholar]

- Chos kyi grags pa. 2021/2022a. Grib ʼjoms rdo rje pha lam gyi las mthaʼ grib mdos shin tu bsdus pa. In ʼBri lugs bang mdzod skor lnga. Compiled by ʼBrong sprul 07 Dkon mchog lhun grub snyan grags rnam rgyal. Khrin tu: Khrin tu rgyas par ʼdebs las gnyer ʼgan ʼkhri tshad yod spyi gnyer khang, vol. 41, pp. 209–21, BDRC: WA3KG218. [Google Scholar]

- Chos kyi grags pa. 2021/2022b. Grib ʼjoms rdo rje pha lam gyi las mthaʼ grib mdos shin tu bsdus pa. In ʼBri lugs bang mdzod skor lnga. Compiled by ʼBrong sprul 07 Dkon mchog lhun grub snyan grags rnam rgyal. Khrin tu: Khrin tu rgyas par ʼdebs las gnyer ʼgan ʼkhri tshad yod spyi gnyer khang, vol. 57, pp. 543–54, BDRC: WA3KG218. [Google Scholar]

- Cornu, Philippe. 2002. Tibetan Astrology. Translated by Hamish Gregor. Boston: Shambhala Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Czaja, Olaf. 2007. The Making of the Blue Beryl—Some remarks on the Textual Sources of the Famous Commentary of Sangye Gyatsho (1653–1705). Soundings in Tibetan Medicine 10: 345–71. [Google Scholar]

- Diemberger, Hildegard. 2012. Holy Books as Ritual Objects and Vessels of Teaching in the Era of the ‘Further Spread of the Doctrine’ (Bstan pa yang dar). In Revisiting Rituals in a Changing Tibetan World. Edited by Katia Buffetrille. Leiden: Brill, vol. 31, pp. 9–41. [Google Scholar]

- Dorje, Gyurme. 2001. Tibetan Elemental Divination Paintings: Illuminated Manuscripts from The White Beryl of Sangs-rgyas rGya mtsho: With the Moonbeams Treatise of Lo-chen Dharmaśrī. London: John Eskenazi in association with Sam Fogg. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, Mary. 1984. Purity and Danger: An Analysis of Concepts of Pollution and Taboo. London: Routledge. First published 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Dung dkar blo bzang ʼphrin las. 2002. Dung dkar tshig mdzod chen mo. Pecin: Krung Goʼi Bod Rig Pa Dpe Skrun Khang. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein, Lawrence. 1977. Causation in Tibetan Religion: Duality and Its Transformations. Ph.D. thesis, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Feldt, Laura. 2012. The Fantastic in Religious Narrative from Exodus to Elisha. London: Equinox. [Google Scholar]

- FitzHerbert, Solomon George. 2018. Rituals as War Propaganda in the Establishment of the Tibetan Ganden Phodrang State in the Mid-17th Century. Cahiers d’Extrême Asie 27: 49–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrison, Jim. 2021. Buddhism, Barad, and Materialism. Symplokē 29: 475–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gell, Alfred. 1998. Art and Agency: An Anthropological Theory. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gentry, James. 2017. Power Objects in Tibetan Buddhism: The Life, Writings, and Legacy of Sokdokpa Lodrö Gyeltsen. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Gurung, Kalsang Norbu. 2009. The Role of Confucius in Bon Sources: Kong tse and his Attribution in the Ritual of Three-Headed Black Man. In Contemporary Visions in Tibetan Studies: Proceedings of the First International Seminar of Young Tibetologists. Edited by Brandon Dotson, Kalsang Norbu Gurung, Georgios Halkias, Tim Myatt and Assist Paddy Booz. Chicago: Serindia Publications, pp. 257–79. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, David Paul. 2015. Painting Traditions of the Drigung Kagyu School. New York: Rubin Museum of Art. [Google Scholar]

- ʼJam mgon kong sprul Blo gro mthaʼ yas. 1973. Gter ston brgya rtsa’i rnam thar. Tezu: Tibetan Nyingmapa Monastery, pp. 257–79, BDRC: MW20539. [Google Scholar]

- ʼJam mgon kong sprul Blo gro mthaʼ yas. 2011. The Hundred Tertöns: A Garland of Beryl, Brief Accounts of Profound Terma and the Siddhas Who Have Revealed It. Translated by Yeshe Gyamtso. Woodstock: KTD Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Karmay, Samten Gyeltsen. 2009. The Arrow and the Spindle: Studies in History, Myths, Rituals and Beliefs in Tibet. Kathmandu: Mandala Book Point. First published 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Keane, Webb. 2018. Perspectives on Affordances, or the Anthropologically Real: The 2018 Daryll Forde Lecture. HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 8: 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelényi, Béla. 2012. Analysis of a Mdos Ritual Text Connected with the Rlung rta Tradition. In This World and the Next: Contributions on Tibetan Religion, Science and Society: PIATS 2006: Tibetan Studies: Proceedings of the Eleventh Seminar of the International Association for Tibetan Studies, Königswinter 2006. Edited by Charles Ramble and Jill Sudbury. Andiast: IITBS, International Institute for Tibetan and Buddhist Studies GmbH, pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Kimmerer, Robin Wall. 2013. Braiding Sweetgrass. Minneapolis: Milkweed Editions. [Google Scholar]

- Lakoff, George. 1987. Women, Fire, and Dangerous Things: What Categories Reveal about the Mind. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Latour, Bruno. 2005. Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lichter, David, and Lawrence Epstein. 1983. Irony in Tibetan Notions of the Good Life. In Karma: An Anthropological Inquiry. Edited by Charles F. Keyes and Errol Valentine Daniel. Berkeley: University of California Press, pp. 223–59. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Shen-yu. 2005. Tibetan Magic for Daily Life: Mi pham’s Texts on gTo-rituals. Cahiers d’Extrême-Asie 15: 107–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, Dan. 1994. Pearls from Bones: Relics, Chortens, Tertons and the Signs of Saintly Death in Tibet. Numen 41: 273–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikles, Natasha L., and Joseph Laycock, eds. 2021. Religion, Culture, and the Monstrous: Of Gods and Monsters. Lanham: Lexington Books. [Google Scholar]

- Millard, Colin. 2002. Learning Processes in a Tibetan Medical School. Ph.D. thesis, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Millard, Colin. 2005/2006. sMan and Glud: Standard Tibetan Medicine and Ritual Medicine in a Bon Medical School and Clinic in Nepal. The Tibet Journal 30/31: 3–30. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, Daniel. 2005. Materiality: An Introduction. In Materiality. Edited by Daniel Miller. Durham: Duke University, pp. 1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Nebesky-Wojkowitz, Réne de. 1996. Oracles and Demons of Tibet: The Cult and Iconography of the Tibetan Protective Deities. Kathmandu: Pilgrims Book House. First published 1956. [Google Scholar]

- Orosz, Gergely. 2019a. Buddhista váltság szertartások (mdos glud) Mongóliában: Az MTA Könyvtára Keleti Gyűjteményében őrzött tibeti nyelvű szövegek filológiai vizsgálata. Ph.D. thesis, Eötvös Loránd Tudományegyetem, Budapest, Hungary. [Google Scholar]

- Orosz, Gergely. 2019b. Doctoral Dissertation Summary–Buddhist Ransom Rituals (mdos glud) in Mongolia: A Philological Analysis of the Tibetan Texts Kept in the Oriental Collection of the Library of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. Budapest: Department of Humanities. [Google Scholar]

- Ramble, Charles. 2004. The secular surroundings of a Bonpo ceremony: Games, popular rituals and economic structures in the mDos rgyab of Klu-brag monastery (Nepal). In New Horizons in Bon Studies (Bon Studies 2). Edited by Samten Gyeltsen Karmay and Yasuhiko Nagano. Delhi: Saujanya Publications, pp. 249–87. [Google Scholar]

- Ramble, Charles. 2019. Srid pa gto mgo gsum. Kalpa Bön. Available online: https://kalpa-bon.com/texts/mgo-gsum/srid-pa-gto-mgo-gsum (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- Schicklgruber, Christian. 1992. Grib: On the Significance of the Term in a Socio-Religious Context. In Tibetan Studies: Proceedings of the 5th Seminar of the International Association for Tibetan Studies (Narita 1989). Edited by Ihara Shōren and Yamaguchi Zuihō. Tokyo: Naritasan Shinshoji, vol. 1, pp. 723–34. [Google Scholar]

- Sobisch, Jan-Ulrich. 2020. The Buddha’s Single Intention: Drigung Kyobpa Jikten Sumgön’s Vajra Statements of the Early Kagyü Tradition. Somerville: Wisdom Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Steinmann, Brigitte. 2011. rNyingmapa Rituals in Sikkim and Nepal: Divining the Future, Worshiping Ancestors with “mdos”: The Selection of Salient Features in Individual Biographies in Order to Frame the Vicissitudes of Social Life. In Buddhist Himalaya: Studies in Religion, History and Culture, vol. II: The Sikkim Papers. Edited by Anna Balikci-Denjongpa and Alex McKay. Gangtok: Namgyal Institute of Tibetology. [Google Scholar]

- Szabóová, Linda. 2024. The Three-headed Black Man: Analysis of a Ritual Text from the Gto Collection (Gto ʼbum). Master’s thesis, Charles University, Prague, Czechia. [Google Scholar]

- Tucci, Giuseppe. 2007. The Religions of Tibet. Translated by Geoffrey Samuel. Berkeley: University of California Press. First published 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, Victor. 1967. Betwixt and Between: The Liminal Period in Rites de Passage. In The Forest of Symbols: The Aspects of Ndembu Ritual. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Unknown. n.d. Gnam chos bdud rtsi ʼkhyil paʼi las tshogs lto ʼgong dbul sri dkar baʼi man ngag zhes bya ba bzhugs so. Leiden: Leiden University Libraries. Available online: https://digitalcollections.universiteitleiden.nl/view/item/328711 (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- Van Dyke, Ruth, ed. 2015. Materiality in Practice: An Introduction. In Practicing Materiality. Tucson: The University of Arizona Press, pp. 3–32. [Google Scholar]

- Watt, Jeff. 2025. Buddhist Deity: Bhurkumkuta Main Page. Himalayan Art Resources. Available online: https://www.himalayanart.org/search/set.cfm?setID=564 (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- Wenta, Aleksandra. 2024. The Vajrabhairavatantra: Materia Magica and Circulation of Tantric Magical Recipes. In Tibetan Magic: Past and Present. Edited by Cameron Bailey and Aleksandra Wenta. New York: Bloomsbury, pp. 61–84. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Brown, A.N. Commanding the Defilement Master: Materiality and Blended Agency in a Tibetan Buddhist Mdos Ritual. Religions 2025, 16, 1067. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16081067

Brown AN. Commanding the Defilement Master: Materiality and Blended Agency in a Tibetan Buddhist Mdos Ritual. Religions. 2025; 16(8):1067. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16081067

Chicago/Turabian StyleBrown, Amanda N. 2025. "Commanding the Defilement Master: Materiality and Blended Agency in a Tibetan Buddhist Mdos Ritual" Religions 16, no. 8: 1067. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16081067

APA StyleBrown, A. N. (2025). Commanding the Defilement Master: Materiality and Blended Agency in a Tibetan Buddhist Mdos Ritual. Religions, 16(8), 1067. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16081067