Abstract

New theologies developed in tandem with evolutionary biology during the nineteenth century, which have been called metaphysical evolutionisms and evolutionary theologies. A subset of these theologies analyzed here were developed by thinkers who accepted biological science but rejected both biblical creationism and materialist science. Tools from the cognitive science of religion, including conceptual metaphor theory (CMT) and blending theory, also known as conceptual integration theory (CIT), can help to explain the development of these systems and their transformation between the nineteenth and the twentieth centuries. The analysis focuses on several stable and popular blends of ideas, which have continued with some alteration into the twenty-first century. The three blends evaluated here are Progressive Soul Evolution, Salvation is Evolution, and Evolution is Therapy. Major contributors to these blends are the Theosophist and theologian Helena P. Blavatsky and psychologist Frederic W. H. Myers, both influenced by the spiritualist movement, particularly the ideas of the spiritualist and biologist Alfred Russel Wallace. The influence of these blends can be seen in the twentieth-century “Aquarian Frontier,” a group of 145 thinkers and organizations identified in 1975 by counterculture historian Theodore Roszak. Part of the appeal of these blends may be seen in their use of metaphors, including the Great Chain of Being and A Purposeful Life is a Journey. The application of the polysemic term evolution in a sense that does much of the theological work of salvation in Christianity can in part be explained by applying the principles of blending theory, including the vital relation “achieve a human scale,” as well as compressions of time and identity. These blends have been successful because they meet the needs of a population who are friendly towards science but disenchanted with traditional religions. The blends provide a satisfying new theology that extends beyond death for a subset of adherents, particularly in the New Age and spiritual but not religious (SBNR) movements, who combine the agency of self-directed “evolution” with the religious concepts of grace and transcendence.

1. Introduction

In 1975, Theodore Roszak, historian of the 1960s and 1970s counterculture movement, identified an Aquarian Frontier, a group of 145 disparate movements and thinkers developing new theologies he called “metaphysical evolutionism.” These theologies centered around the idea that humans are “unfinished animals summoned to unfold astonishing possibilities” (Roszak 1975, p. 5). Unlike creationists and Christian fundamentalists, these thinkers embraced Darwin, but believed that evolution required people to actively pursue social, cultural, and “spiritual” transformation during life. Some of them used evolution as an active verb, with the command “Evolve!” replacing “Be Saved.” The Frontier did not begin in the twentieth century; much of it drew from nineteenth-century systems, including the spiritualist and Theosophical movements. Although Roszak’s study of these groups is not well known, it provides a sampling of evolutionary theologies that had developed in the preceding century in response to Darwin.

Evolutionary theologies, which attempt to accommodate biological science, are less well-known than those that attack it. While most people are familiar with the disputes over evolution and the conflict model of the relationship between religion and science, they are less aware of the accomodationist theologies, which emerged both inside and outside of organized religion. They were developed by people who accepted biological science but believed in the need for a spiritual life on earth and the possibility it could continue after death.

Darwin had acknowledged the important role that cultural productions like religion play in natural selection (D. S. Wilson 2010). Between the 1840s and 1880s, liberal Christians, spiritualists, and Theosophists united around the embrace of science and empirical methods. But they also rejected materialism, which was a topic of contention in both science and religion (Heimann 1972; Raia 2019). Among the systems that attempted to harmonize natural selection with religious thought are Anglican natural theology and spiritualism, which came in Christian and non-Christian varieties. Scientists also participated in the development of these theologies, including the prominent biologist Alfred Russel Wallace.

In the twenty-first century, the groups and thinkers along Roszak’s Aquarian Frontier, supplemented by new arrivals, continue to develop new belief systems. Although beyond the scope of this paper, some who continued to elaborate evolutionary theologies include holistic doctor Deepak Chopra and futurist Barbara Marx Hubbard. Both are among those who in 2008 published a “Call to Conscious Evolution” (Beck et al. 2009). They envision the transformation of society in a more healthful and equitable direction, primarily through social and environmental change. They also emphasize the role of “mind–body–spirit” in health and healing and the need for a “shift in our shared field of consciousness” (Beck et al. 2009; Beckwith et al. 2008).

Although they accept biological evolution, some of the Call’s framers are also open to ideas that many scientists would find religious—life after death, divine presence or purpose, and the possibility of help from more advanced life forms (which may include traditional religious figures but also aliens and wise former humans). The Call’s signers include both religious and scientific figures. Those attracted to the religious and supernatural are generally critical of orthodox religious systems. They generally avoid speculation about the origins of life or its ultimate purpose and focus instead on personal development during life and after death, yet they are also open to outside help. Their concept of evolution does much of the work that salvation performs in religious systems.

I call these belief systems “evolutionary theologies,” though many who adhere to them deny belief in God or a Creator. Like mystical and indigenous spiritualities, these systems emphasize divine immanence, or the presence of God or spirit in this world, rather than a distant, transcendent deity. They advocate personal transformation and the use of therapeutic techniques during the present life, although they may also believe in an afterlife. They largely dispense with a vengeful God, or eternal damnation, two ideas that were already clashing with common sensibilities in the more liberal Christian denominations of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

Evolutionary theologies emerged in predominantly Christian societies but today also incorporate Asian religious concepts like karma and reincarnation. They have continued to develop in Hindu and Buddhist contexts (Nanda 2011; Heehs 2020). I write in greater detail elsewhere about this development (Prophet 2018a, forthcoming). In this article, I explore ways in which the cognitive science of religion can explain the growth and transformation of evolutionary theologies among the New Age and spiritual but not religious (SBNR) movements.

New Age religion is a diverse collection of sensibilities that coalesced during the twentieth century. Though its precise definition is contested, it remains useful as an analytic category (Kemp 2004). The presence of evolution in New Age religion has been noted, for example, by Wouter Hanegraaff, who identifies evolution as an essential aspect of New Age thought. He views the New Age as “secularized esotericism,” reinterpreting “esoteric tenets from secularized perspectives,” of which evolution is a “fundamental component” (Hanegraaff 1998, p. 520).1 However, evolutionism in the New Age is not uniform. As Hanegraaff notes, “although New Agers share a belief in ‘evolution,’ they have different ideas about what it is, how it works and where it is going” (Hanegraaff 1998, p. 515).

SBNR is a subset of those who claim to be non-religious, the so-called religious “nones,” who make up about 28 percent of the population (Smith et al. 2024). About half of the “nones,” according to a 2023 Pew poll, also claim to be spiritual, hence the SBNR label. Religious nones often adhere to some type of religious belief, and 69 percent believe in God or a higher power (Smith et al. 2024). There is overlap between the SBNR and New Age movements.

Linda Mercadante has identified a number of stable values in SBNR populations, including a common invocation of evolution, which she calls “a creative switch on Darwinian theory, because it is not humans who are evolving as much as God.” These individuals see themselves as representing a type of “post-Christian spirituality” that avoids exclusive truth claims (Mercadante 2014). Her subjects combined elements of the human potential movement with “a Western expectation of progress and a nod toward evolutionary theory” (Mercadante 2014, p. 108). The idea of God (or the Creator) evolving along with creation is a Hermetic concept related to the belief systems evaluated below.

1.1. Cognitive Science of Religion and Blending Theory

The cognitive science of religion is an interdisciplinary field that develops biological and cultural explanations for the persistence and transformation of religious ideas (see Clements 2016; Richardson 2024). Conceptual metaphor theory (CMT) makes its contribution by incorporating techniques from linguistics to identify ideas that recur cross-culturally such that they are proposed to be “a fundamental scheme of thought serving many cognitive and social/ideological functions,” as described by Raymond Gibbs. CMT holds that “significant parts of abstract thinking [such as religious ideas] are partly motivated by metaphorical mappings between diverse knowledge domains” (Gibbs 2009, p. 15).

Two metaphors in particular are useful for explaining evolutionary theologies. Life is a Journey is a common metaphor often used to express religious ideas. (In the literature on metaphor theory, the names of metaphors are commonly displayed in small capital letters.) Another important metaphor found in evolutionary theologies is the Great Chain of Being, which is not only a metaphor but also a complex philosophical concept that has influenced both biological science and religion. The idea that living beings are organized in some kind of hierarchy has been discussed in Western philosophy since Aristotle’s scale of nature. Similar ideas about the superiority of humans to non-human animals are also found in non-Western cultures. Although biological science began to erode the philosophical foundations of the great chain in the nineteenth century, it remains useful to people thinking of themselves in relationship to both divine powers and the natural world (see Lovejoy 1964; D. J. Wilson 1987; Lakoff and Turner 1989).

Blending theory arose from CMT and focuses on the development of new ideas, often called “blends.” Gilles Fauconnier and Mark Turner offer a set of principles for developing successful blends, which they argue explain why some ideas catch on (Fauconnier and Turner 2002; Turner 2014). Blends are believed to operate at unconscious levels to structure new experiences. As Mark Turner explains, “blending operates almost entirely below the horizon of consciousness” (Turner 2014, p. 18). Nevertheless, blending is a crucial part of modern cognition and, as explained by Glen Hayes, “shapes how people live and think” (Hayes 2016, p. 167). Blending theory has been fruitfully applied to the development of religious ideas, and provides new scope for understanding theological development (Hayes 2016). Unlike CMT, which looks for recurring structures, blending theory explains change and new developments. It is also known as conceptual integration theory (CIT). Although CMT and CIT have been expanded and critiqued since they were introduced, they continue to form a basis for analysis (see, for example, Charteris-Black 2004; Bache 2005; Gibbs 2009; Kövecses 2020). Lucas Keefer and Adam Fetterman summarize recent research on the role of metaphor and analogy in the development of God concepts (Keefer and Fetterman 2022).

I apply CMT and CIT to develop my argument that evolutionary theologies have been adopted because they make sense to a growing subset of people, which can be explained both by their adherence to the principles of CIT, and also by the fact that they meet social and cultural needs. Evolutionary theologies arose at a time when many educated people had become skeptical of religious truth claims and believed humans had more control over their destiny than world religions allowed. They explained the religious miracles of the past using scientific language and pointed to the phenomena of spiritualism, mesmerism, and hypnosis as non-religious and “scientific” explanations for the miracles of history. They developed a new and active lexicon of spiritual “evolution,” which combines scriptural with biological metaphors.

1.2. Historical Methodology

Evolutionary theologies represent a new type of relationship between religion and science, which goes beyond the standard conflict, independence, and dialog typology. Rather, they can be seen as an attempt to integrate science with religion along the model proposed by Barbour (2000). They seek to expand the scope for human agency while accepting the limits of knowledge. They arise out of the spiritist/spiritualist milieu of the late nineteenth century, which proposed, in the words of historian David Hess, “an empirically grounded basis for religious experience and faith” (Hess 1993, p. 19; see also Ferguson 2012).

My analysis compares two historical periods: the twentieth-century “Aquarian Frontier” identified by Roszak, and the nineteenth-century theologies of the Russian Theosophist Helena Blavatsky (1831–1891) and British psychologist Frederic W. H. Myers (1843–1901). Blavatsky’s system of “soul evolution” envisioned a vast series of progressive reincarnations that ratcheted each individual up a karmic ladder (Blavatsky 1993; Sinnett 2008; Godwin 2011). Myers argued that humans have a duty to pursue their own evolutionary development through the arts and creative practices, which would improve life on earth and lead to a better afterlife. Both systems incorporate Hermetic principles, which portray humans as working together with divine forces and powers. While Blavatsky is better known today, Myers’s system was simpler and it spread widely without his name attached. His ideas about the secondary self, art, and therapy were taken up, for example, in Jungian psychology.

My analysis sets aside the question of whether the claims of religions are true, and instead focuses on the question of theological change, which ideas took hold, and how they developed into new blends that seem commonplace in particular subcultures. I will first explore the historical development of Blavatsky and Myers’s systems before analyzing them and their later echoes in the Aquarian Frontier.

The New Age and SBNR movements and the Aquarian Frontier are not identical, but they do overlap. The Aquarian Frontier captures a moment in time during the 1970s, while the other two movements are amorphous and rapidly changing. The spiritualist and Theosophical movements of the nineteenth century influenced contemporary theologies via textual transmission and groups that have persisted to the present. Catherine Albanese has studied these currents, which contribute to what she calls American metaphysical religion, made up of “fluid and egalitarian” networks that are under-studied because they “appear especially temporary, self-erasing, self-transforming” (Albanese 2007, p. 8). The fact that these networks are less studied than evangelical movements and denominational institutions does not make them less important or influential.

2. How Evolutionary Theologies Developed over Time

The evolutionary theologies that I evaluate coalesce around the idea that “Evolution” depends on the practice of spiritual discipline and/or the development or presentation of psychic and healing powers; furthermore, that people who demonstrate such powers are templates for future human transformation into advanced or divine beings.

Evolutionary theologies engage with biological science, and it is interesting to note that since Darwin published On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection in 1859, biology itself has gone through several phases with regard to the possibility that conscious human effort and activity can influence the course of evolution. Darwin was skeptical that humans could pass along acquired characteristics (a concept that is known as Lamarckism). However, he also believed that there was an interaction between habit and instinct and speculated that humans might recover lost “vestigial” animal talents, such as the ability to move the ears (Darwin 2006b, p. 789). Darwin struggled to explain the cause of variation in animals and humans, which left more room for human effort.2

Darwin’s evolutionism was open-ended and avoided the question of the origins of life. His main goal was to demonstrate that species were not fixed. Darwin wrote that he could see “no limit to the amount of change, to the beauty and infinite complexity of the co-adaptations” of nature (Darwin 2006a, p. 519). Improvement could be identified in natural selection, as “corporeal and mental endowments will tend to progress towards perfection” (Darwin 2006a, p. 760). In spite of the pessimistic Malthusian direction his ideas could be taken (“survival of the fittest”), there were ways in which Darwinism could be conscripted into an optimistic program of human perfection, particularly when seen through the lens of Herbert Spencer, a polymath who promoted ideas of cultural evolution (Spencer 1857). Evolutionary theologians took up some of Darwin’s ideas and ignored the rest.

Wallace, who independently developed a theory of evolution by natural selection and was the catalyst for Darwin to publish his own theory, gave shape to new theologies. He proposed in 1864 that the human mind could continue to develop after death, a “progression of the fittest” (Wallace 2018, p. 43). He was updating the use of evolutionary language to describe transformation of mind on earth and after death, a usage that has continued alongside the biological parlance.

During the late nineteenth century, when spiritualism and Theosophy were developing, Darwinism faced many challenges from the scientific community, and there were a variety of theories explaining the transformation of species (Bowler 1984, 2001). In spite of his skepticism of Lamarckism, Darwin did leave open a role for social influences on biological evolution. He allowed that both the “conditions of life”, i.e., climate and geography, but also culture and human actions could influence the evolution of species, especially since he was unable to identify the cause of variation (Bowler 1984; Richards 1992). The gene-oriented neo-Darwinism of the twentieth century brought the focus solely to heredity and ignored what Darwin had called the “conditions of life.” However, today the rise of epigenetics has once again opened up the possibility that human activity interacts with genes, and that experiences and habits can be transmitted to one’s descendants (Jablonka and Lamb 2005, 2010; Cregan-Reid 2018).

Today, as before Darwin, evolution signifies different things to different people. When those on the Aquarian Frontier spoke of evolution, they sometimes meant the social or cultural evolution of groups, or the personal transformation of individuals during life. Some of the key takeaways from nineteenth-century evolutionary biology that were attractive to evolutionary theologians were that evolution offers an improved life for the group gradually in the future, and further, that individuals who undertake self-improvement can contribute to the progress of the group. But for many evolutionary theologians, spiritual evolution is also something that accrues to individuals after death, an idea that is outside the scope of biological evolution. They are seldom conscious of the fact that they use the term in a way that mirrors the concept of religious salvation. Why has this usage taken hold? Perhaps for this population, spiritual “evolution” is appealing as a more self-directed process that avoids unwanted elements of Christian theology. (Note that some evolutionary theologies incorporate a mystical version of Christianity.)

2.1. Influence of Hermeticism, Gnosticism, and Neoplatonism

Evolutionary theologians of the nineteenth century drew from many sources, including Christian scripture, but they were also deeply influenced by Hermetic, Neoplatonist, and Gnostic texts, all of which developed in the early centuries of the common era. These complex systems were popular in the ancient world, and became the topic of renewed interest in Europe after the Renaissance. Their influence was broad, including among our evolutionary thinkers.

Neoplatonism is a religious system created out of some of the theological speculations in Plato’s dialogs, which became popular in the second-century CE. Neoplatonist teachers recommended various activities, ranging from philosophical contemplation to magic, to fulfill the goal of salvation, which was for the soul to return to the One source.

Hermeticism was named after the Greek god of wisdom. It blended ideas from Egyptian and Greek religion and provided expanded scope for human agency by teaching that humans could participate in creation and that the Creator actually needed humans in order to become self-aware. Hermeticism allowed people to begin thinking of themselves as embryonic gods (see Van den Broek and Hanegraaff 1998). Another important Hermetic idea is that gods were once human and that humans can become gods. Hermeticists also believed that Gods or demigods (former humans) work with the Creator to give mind (“nous”) to humans.

After the Renaissance, as humans became more confident in their ability to dominate natural forces, the Hermetic template was stretched in new directions, including, by the nineteenth century, the incorporation of Hinduism and Buddhism. Hermeticism offers clues to the appeal of evolutionary theologies. Unlike orthodox Christianity, it allows us to think of ourselves as more than helpless creatures. We become active participants in creation, joining intermediary figures such as demigods, angels, or perfected deceased humans.

Gnosticism is a complex movement that included Jews, Christians, and pagans. Some Gnostic texts claimed to present the true and secret teachings of Jesus. Gnostic texts were suppressed by the Church, but some began to resurface in the nineteenth century and influenced evolutionary theologians. They allowed greater scope for human divinization, or transformation into the divine image, than orthodox Christianity (see DeConick 2016).

Gnosticism, Neoplatonism, and Hermeticism all contained some degree of ritual and therapeutic practice. They also for the most part promoted celibacy, wisdom, and discipline as the requirements for salvation, or oneness with God or gods. The question of sex with respect to spiritual evolution became central to some of the debates over evolutionary theologies. The idea that only the celibate could evolve spiritually clashed with the more liberal values of the twentieth century and was later deemphasized in the most popular evolutionary theologies. However, the sense of increased agency available in the systems could be grafted onto the optimistic sentiments of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

2.2. Helena Blavatsky and the Development of the Theosophical Root Race System

In February 1876, Helena Blavatsky, the Theosophical Society’s co-founder and its best-known member, wrote of a “double evolution” that entailed “spirit keeping pace with the evolution of matter” (Blavatsky 1960, vol. 1, pp. 212–13).3 She praised the spiritualist–biologist Wallace, and used him to support her theories, which also drew upon the Romantic Naturphilosophie and other influences. She saw the soul or spirit evolving in tandem with the physical transformation of the human species.

At the time, Blavatsky’s main audience was the spiritualist movement, which originated in the 1840s and included millions of members across the Americas and Europe (Lavoie 2012).4 Although it is best known for its fascination with mediums, spiritualism also developed complicated new ideas about the afterlife, which contributed to the vision of a “modern heaven,” in which people could continue to learn and improve themselves after death (McDannel and Lang 1988). Spiritualists generally accepted that there was a biological connection between humans and animals (see, for example, Davis 1852). Wallace also speculated that “higher intelligences,” perhaps advanced former humans, had originally given humans the evolutionary boost of expanded brain capacity and other unique human mental qualities (Wallace 1875; Fichman 2004; Smith 2008).

Blavatsky’s theology drew themes from spiritualism and other sources into new language by formally identifying evolution as a kind of self-directed salvation during life and after death. Theosophists saw mediumistic (psychic) talents as a marker of individuals occupying a more “advanced” phase of evolution, though they also warned of the spiritual risks that accompanied the pursuit of these talents. Blavatsky built upon earlier evolutionary theologies that also included conscious effort and striving as a component of salvation, as well as apprenticeship under wise adepts and teachers (Chajes 2019).

The meaning of spiritual evolution changes from Blavatsky’s early to later work. In her first major work, Isis Unveiled, she portrays humans as beginning their evolutionary journey out of the “spiritual part of the ether,” as “monads,” which develop through different forms (Blavatsky 1960, vol. 1, p. 340).5 The most developed form of Blavatsky’s theology was written after she visited India and broadened the scope of her audience beyond the spiritualist movement. It was published in her 1888 Secret Doctrine, which describes a sequence of seven “root races,” or bodily forms (not connected to human races) (see Prophet 2018b). It is a complex system, which also describes soul progress through reincarnation on seven continents (including the mythical Atlantis and Lemuria) and seven planetary spheres over millions of years. In this analysis, I focus on a simplified root race system and the elements that relate to personal transformation. Table 1 summarizes the components of Blavatsky’s system that are most relevant to my comparison.

Table 1.

Relevant elements of Helena Blavatsky’s root race system, 1888.

The system provides scope for human agency in that both individuals and groups may influence the course of their evolution. However, it also warns against the independent development of psychic powers, which made it difficult for some spiritualists to accept. Theosophists argued that psychic talents are dangerous and should only be developed under supervision with ascetic discipline. Some have criticized the system for incorporating elements of nineteenth-century scientific racism, but its primary focus is not on human races and it has been taken in liberating directions by non-whites (see Prophet 2024).

Another difficulty with understanding the root race system is its long time frames. It adapts deterministic elements from Hindu and Buddhist religion related to the concept of kalpas or vast cycles of time (Blavatsky 1993, vol. 1, pp. 641–42). In fact, the root race system is so difficult to understand that even Theosophists today argue about its meaning. The long time frame (especially the slow progression through planets other than Earth) has made it difficult for humans to find a place for personal striving. Nevertheless, the root race system is open-ended and, unlike the Neoplatonist system, does not include a fixed end or goal (Blavatsky 1993, vol. 1, p. 43). The system blended well with spiritualist notions of limitless human possibility and efforts to harmonize religion with a scientific spirit of inquiry, though it also contained ascetic, elitist, and deterministic elements that are beyond the scope of this study (see Prophet 2018a, 2018b, forthcoming).

2.3. Frederic W. H. Myers and Therapeutic Salvation

Myers was a Victorian poet and Cambridge-educated classicist who was influenced by spiritualism and Theosophy, but also deeply attached to Neoplatonism (see Lavoie 2015; Hamilton 2009). His evolutionary theology can be encapsulated in the sentence: “It used to be asked whether man was akin to the ape or to the angel. I reply that the very fact of his kinship with the ape is proof presumptive of his kinship with the angel” (Myers 1903, vol. 1, p. 242). However quaint this supposition may seem today, it shows Myers’s attempt to demonstrate an evolutionary progression from animal to human to something greater than human, a clear invocation of the Great Chain of Being. Myers also drew on spiritualist ideas of salvation. Spiritualists believed that angels are simply wise former humans who have grown in knowledge after death. His statement meant that just as humans have been transformed from their primate ancestors, so they will continue to “progress” during life and after death.

Myers’s mature system updated and expanded Neoplatonism, which taught that the soul’s highest good is to return to a state of original perfection with the One source. Hermetic systems allow that the return to the One may not be identical to the emanation, since human life contributes to the completeness of God. Myers builds on Hermetic themes by resisting the determinism of either Christian or Neoplatonic salvation. I provide here a summary of his theology, which was less developed than Blavatsky’s and presented only in a rudimentary sketch.6 It incorporated elements of his psychological ideas with an afterlife.

Myers aligned himself with the more body-friendly and this-worldly elements of the systems he synthesized. Where Blavatsky preached asceticism and peril in the evolutionary path, he proposed a joyful life on Earth followed by unending progress and creativity after death. He glorified human love and the erotic as a creative force that ranges from “primitive instinct” to a transformative divine mediating power. Rather than seeking to suppress or overcome instinct and emotion, he invited them into his spectrum. “Love and religion are thus continuous….. Love is the energy of integration which makes a Cosmos of the Sum of Things.”7

Myers’s evolutionary theology lacks the certainty of the Theosophical ratcheting from matter to spirit by way of the root races. He did not claim to know the future of humanity. Egil Asprem includes Myers’s approach under the umbrella of an “open-ended naturalism” (Asprem 2014, p. 302). Myers identified “spiritual evolution” as “our destiny, in this and other worlds;—an evolution gradual with many gradations, and rising to no assignable close” (Myers 1903, vol. 2, p. 281). He portrays telepathy as a talent that is both developed by advanced souls and recovered from previous evolutionary states, such as animal life.

Myers’s system, as summarized in Table 2, contains several elements that are more congenial to twentieth-century sensibilities than the Theosophical one, in the sense that it resonated with a progressive and this-worldly faith. It was also more plausible in terms of its harmony with evolutionary biology. It did not, like Theosophy, engage in fantastic speculation about past and future ages or life on lost continents, other than to suggest talents deriving from a germ planted by higher intelligences. Myers was broadly influential in his day, and his thought about the subliminal consciousness and secondary self influenced Carl Jung as well as popular spiritual writers such as Evelyn Underhill and Richard Maurice Bucke, whose ideas echoed through the counterculture of the 1960s and 1970s, and persist in today’s New Age and spiritual but not religious movements (Prophet forthcoming).

Table 2.

The evolutionary system of Frederic W. H. Myers, c. 19018.

3. Applying Conceptual Metaphor Theory and Blending Theory to Evolutionary Theologies

A pronghorn antelope running across the North American plains “learned” to run faster when chased by predators, and today “remembers” the chase even though those predators have become extinct, so argues a 1998 book by John Byers entitled American Pronghorn: Social Adaptations and the Ghosts of Predators Past. Gilles Fauconnier and Mark Turner use Byers’s theory as an example of how the imagination applies the principles of blending to alter “identity,” which is termed a “vital relation” in blending theory (Fauconnier and Turner 2002, pp. 115–19). (They set aside the debate in evolutionary biology as to whether individuals can “remember” events that happened to their ancestors, and the role of social adaptation in culture.) The example of the pronghorn chased by the ghost or memory of an extinct predator shows that even scientific minds engage in metaphorical thinking to explore the theory of evolution, as contemporary biologists find it useful to compress the identity of past and present individual members of a species.

Being able to think about evolution as salvation also requires the compression of identity—in this case the actions of multiple members of a group whose actions result in the successful propagation of a species over time are compressed and viewed as if the same individual had persisted for hundreds of thousands of years. The compression process is aided, of course, by the concept of a transmigrating or reincarnating soul.

Below is a review of the essential components of conceptual metaphor theory (CMT) and what Fauconnier and Turner call the constitutive and governing principles of blending, along with a discussion of the Great Chain of Being metaphor. The overview is followed by analysis of the components of the evolutionary systems examined in this article. Then we apply CIT, or blending theory, to three blends: Progressive Soul Evolution, Evolution is Therapy, and Salvation is Evolution.

3.1. Embodied Minds and Conceptual Integration

CMT arises from a tradition of embodied cognition going back to Aristotle and continuing through a range of thinkers including Maurice Merleau-Ponty, John Dewey, and Francisco Varela (see Lakoff and Johnson 1999; Robbins and Aydede 2009). Linguists and neuroscientists are continually refining and testing the basic assumptions of the theory, and have applied it to social and religious concepts. According to the theory, metaphors are not just literary or linguistic devices, but actually structure and constrain the way we perceive the world. They are not “arbitrary,” argue Lakoff and Johnson, but “have a basis in our physical and cultural experience,” even though they may vary from one culture to another (Lakoff and Johnson 1980, p. 14).

A conceptual metaphor is one in which we “systematically use inference patterns from one conceptual domain to reason about another conceptual domain.” The use and meaning of metaphors depend upon the “nature of our bodies, our interactions in the physical environment, and our social and cultural practices” (Lakoff and Johnson 2003, p. 246). The focus on the body marks a break from earlier philosophical systems. Lakoff and Johnson argue that “we cannot, as some meditative traditions suggest, ‘get beyond’ our categories and have a purely uncategorized and unconceptualized experience” (Lakoff and Johnson 1999, p. 19).

Lakoff and Johnson focus on the idea of a “primary metaphor” that recurs cross-culturally and forms the basis of complex metaphors such as those encountered in religion. These primary metaphors are acquired “unconsciously through everyday experience” and then develop into “universal (or widespread) conventional conceptual metaphors” (Lakoff and Johnson 1999, p. 46) The way cultures think about religious doctrines such as creation and the afterlife, according to CMT, is fundamentally shaped first by our bodies and second by our cultures. A set of primary conceptual metaphors has been identified and tested cross-culturally, such as More is Up. These are elaborated into a family of metaphors associating good qualities with position, such as Happy is Up. Primary metaphors are combined in more complex religious metaphors like Heaven and Hell. Spatial relations are central in research that deals with a vertical metaphor like the Great Chain of Being, which historically has been imagined in two ways: linking forms of life in order of complexity and indicating a vertical series of Earthly to heavenly beings. Those in a higher, or up, position are considered more advanced and closer to God.

Another important concept from cognitive science is the schema, which is a way of organizing information categories and their relationships. Our experience of life and the way we think about it (cognition) is influenced by the way our bodies process information about their location in space. It could be argued that elements of Plato’s thought were structured by the unconscious experience of having a body. For example, in the Timaeus, Plato explains the order of things by drawing an analogy between the organization of the body and the cosmos. He associated the soul with the head because it is higher than the body (seat of the unruly passions), and hence closer to the Good (Zeyl 1997, p. 1248).

Such a metaphor seems quaint today. Complex metaphors are not static. They change in response to new social and technological developments and can allow words to develop polysemy (“systematically related meanings for a single word”). As Lakoff and Johnson point out, complex metaphors allow us “to reason about the target domain in a way that we otherwise would not” (Lakoff and Johnson 1999, p. 82). Polysemy permits us to preserve “in the target domain the inferential structure of the source domain” (Lakoff and Johnson 1999, p. 91). For example, the metaphor Love is a Journey was extended in the twentieth century to incorporate new inferences, such as “driving in the fast lane,” which suggests a relationship is developing too quickly, a mapping that would have had no relevance in horse and buggy days (Lakoff and Johnson 1999, p. 67). When the term “evolution” was associated with natural selection in the nineteenth century, it opened the way for polysemic mappings in multiple areas of life.

3.2. Complex Metaphors at Work in Evolutionary Theologies

When people in certain subcultures describe self-improvement and personal transformation as evolution, they are engaging in polysemy. Metaphor theory has developed a refined approach to the subculture-specific application of metaphors. As Lakoff and Turner point out, there is nothing wrong with multiple mappings of metaphors if they are performing useful interpretive work. For example, the metaphors Life is a Journey and Life is a Precious Possession both have relevance.

A common schema relied on in evolutionary theologies is that of a path and the accompanying complex metaphor, A Purposeful Life is a Journey, which is rooted in the common linguistic Source–Path–Goal schema. Metaphors are more than just a poetic reframing of what “actually” happens in life. Rather, argue Lakoff and Johnson, they expand the “sensorimotor inferential capacity.” Therefore, the metaphor “A Purposeful Life Is a Journey lets us use our rich knowledge of journeys to derive rich inferences about purposeful lives” (Lakoff and Johnson 1999, p. 59).

Religious systems are often oriented around the solution to a problem, such as suffering or sin. “This problem-solution framework requires goal-based ways of thinking, which is one reason,” argues Peter Richardson, “why the source-path-goal schema underpins so many different types of religious language” (Richardson 2024, p. 407). The notion that life is a journey on a path towards enlightenment is common in many of the esoteric systems that contributed to both Theosophy and spiritualism. They rely on an upward path requiring effort and self-transcendence, even more so than traditional Christian salvation.

The Great Chain of Being is evaluated by Lakoff and Turner as a complex metaphor found in many cultures, which consists of several basic metaphors. They argue that it persists in a “highly articulated version” that helps us to understand “ourselves, our world, and our language,” though it has been abandoned in the philosophical history of ideas (Lakoff and Turner 1989, p. 167). They observe that “The Great Chain Metaphor is a tool of great power and scope.… It allows us to comprehend general human character traits in terms of well-understood nonhuman attributes; and, conversely, it allows us to comprehend less well-understood aspects of the nature of animals and objects in terms of better-understood human characteristics” (Lakoff and Turner 1989, p. 172).

The metaphor also helps us understand the human in terms of the nonhuman, as did Myers when he placed the human between ape and angel. The Great Chain of Being metaphor is useful in understanding evolutionary theologies because it shows that it is natural for humans to use both similarities to and differences from animals to project their destiny into the future. Myers was hardly the first to have made such a comparison. In the eighteenth century, the English poet Alexander Pope suggested that “superior beings” inhabiting other globes would probably view a scientist like Isaac Newton as humans view apes (quoted in Lovejoy 1964, p. 193). The human link with the “inferior lives” of animals suggests an analogous tie with “superior lives.” Such a metaphor does not have salience in some subcultures, such as eco-spiritualities, which have flattened the great chain to achieve greater parity with animal life. Nevertheless, the metaphor persists. My research is intended to evaluate the role of metaphor in the early development of evolutionary theologies. Another helpful tool is blending theory (CIT).

3.3. Blending Theory, also Known as Conceptual Integration Theory

Why do metaphors change over time? Blending theory, or CIT, offers insight into the process. The term evolution has been blended in all sorts of ways since 1859. Scientists have often found it useful to personify evolution in an attempt to help people better grasp a theory that is conceptually difficult, since it extends over extremely long periods of time and affects groups rather than individuals. The pronghorn chased by ghosts is just one of these types of blends.

Models of the afterlife are an interesting area of analysis for blending theory. General templates for heaven and hell have existed culturally for a long time. But by the nineteenth century, these templates were being altered by the modern heaven movement. According to blending theory, this transformation occurred in response to cultural developments through a process that Fauconnier and Turner call “running the blend,” which means the selective combining of inputs from various mental spaces into a single unit and the simultaneous elaboration of the connections between the spaces. “Running” really means to “imaginatively” modify it. It may be run multiple times by different people until it reaches a point of “equilibrium,” which they describe as “a place where the network is ‘happy.’” They describe a “flash” of comprehension that often occurs when “running” a blend (Fauconnier and Turner 2002, p. 44).

When working with an existing template, as Fauconnier and Turner describe it, “the creative part comes in running the blend for the specific case. In cultural practices, the culture may already have run a blend to a great level of specificity for specific inputs” (Fauconnier and Turner 2002, p. 72). For thousands of years, the culturally specific blend of the Western heaven has included God, Jesus Christ, the savior, angels and saints in white robes, and the souls of dead people. But during the nineteenth century, the figure of Jesus was deemphasized from savior to teacher or elder brother, and departed loved ones played a greater role. Angels began to be imagined as dressed in modern clothes. Elements of the Christian heaven were combined selectively with elements from the classroom input space, suggesting that education could continue in the afterlife.

The term “input space” will be used in the coming discussion of blending. It is derived from Fauconnier’s theory of mental spaces, which are “relatively small mental models of particular situations that have been structured by the concepts in our conceptual systems” (Lakoff and Johnson 2003, p. 261). We can view common elements of life such as family, dinner, school, etc., as each making up a “mental space” that is “framed,” or organized, in a specific cultural way. Spaces are constructed from cultural building blocks and conceptual domains. Information is selectively “mapped” from one or more input spaces into a new blended space that contains some elements of each input space. The mapping takes the form of an “integration network” that includes the optional generic space, one or more input spaces, and the blended space. Connections between the spaces can take place by analogy or the application of what are called “vital relations,” expanded on below (Fauconnier 1994).

New spaces based on an existing blend must take cultural templates into account, but they do not have to replicate them. In fact, the new blend often clashes with the template in important ways. This is where cultural creativity comes in. A particular variation in the nineteenth-century modern heaven blended space considers Earth as a schoolroom, and death as a kind of graduation into higher forms of education. In this blended space, only selective parts of the education space have been added or “compressed” into the heaven space. For example, the university cap and gown are typically omitted from arrival in the heavenly classroom. But the notion of instructors and pupils moving toward higher “degrees” is applied. When a blend is at equilibrium, or “happy,” it appears seamless and nobody notices the clashes or omission of certain elements.

3.4. Types of Networks

When we begin to consider religious and philosophical concepts, it is easy to see that multiple input spaces may contribute to a single blended space, and that some blends are more complex than others. In blending, a “network” incorporates the totality of the spaces being combined to create a new concept. Before we evaluate the specific input spaces engaged in forming the blends Progressive Soul Evolution, Evolution is Therapy, and Salvation is Evolution, let us first review the types of networks. There are four major types of networks: simplex, mirror, single-scope, and double-scope. We will be focusing on the double-scope network, which is most applicable to our current study. It combines “inputs with different (and often clashing) organizing frames as well as an organizing frame for the blend that includes parts of each of those frames and has emergent structure of its own” (Fauconnier and Turner 2002, p. 131). In a double-scope network, both frames contribute to the blend. As an example, Fauconnier and Turner cite the computer “desktop,” which selectively draws elements from office work (file folder, trash can) and computer commands (save, delete).

Although of only passing relevance to this study, Fauconnier and Turner argue that it is the capacity to perform double-scope blending that “is characteristic of human beings but not other species and is indispensable across art, religion, reasoning, science, and other singular mental feats that are characteristic of human beings.” It is also the “indispensable capacity needed for language” (Fauconnier and Turner 2002, pp. 180–81).

Double-scope blending, they argue, also plays a crucial role in category change by creating “more elaborate and richly connected networks of spaces” (Fauconnier and Turner 2002, p. 274). So when Wallace began first to argue that humans were endowed with “mind” by higher intelligences, and to equate soul progress after death (salvation) with evolution, and Blavatsky took up the narrative with proof texts from Hermetic divinization narratives, they were creating a fertile network of “input spaces” and complex networks, which eventually became what is called a recursive blend, Evolution is Therapy.

“Recursion” happens when one blended space becomes an input to another network, which ultimately allows for more plausible forms of compression (Fauconnier and Turner 2002, p. 334). I argue that recursion takes place when Salvation is Evolution becomes an input space for Evolution is Therapy, which can then be called a “hyper-blend” (Turner 2014, p. 216).

Not all blends succeed, and in fact Fauconnier and Turner use a natural selection metaphor to describe the way successful blends are selected. Our minds are like a “bubble chamber” in which new blends constantly arise; only a few will be selected for in the culture and survive for a time (Fauconnier and Turner 2002, p. 321). Creative thinkers in every culture are the ones who construct and refine networks of thought. As Fauconnier and Turner remark, “Finding optimal networks has always been a highly valued skill, for which writers, poets, statesmen, teachers, scientists, and lawyers are highly regarded” (Fauconnier and Turner 2002, p. 384). And, we might add, theologians, who are less often recognized for their creativity, given that they usually claim that new interpretations are based in divinely inspired eternal truth.

Success in blending can be predicted, according to Fauconnier and Turner, by adherence to particular “constitutive and governing principles.”9 Of these principles, the first and foremost, or the “one overarching goal driving all of the principles”, is “Achieve Human Scale.” To achieve “a human scale blend,” they write, “often requires imaginative transformations of elements and structure in an integration network” (Fauconnier and Turner 2002, p. 312). As we will see below, the unsuccessful elements of nineteenth-century blends were often those that did not achieve a human scale. Additional governing principles are as follows: compress what is diffuse; obtain global insight; strengthen vital relations (identity, uniqueness, etc., as discussed in the next section); and come up with a story. When applying the principles of blending to evolutionary theologies, we should consider that evolution developed dense polysemy at a time when values among different groups in Western culture were clashing. The ideas that succeeded, frequently, were those that told the best story and put the human at the center.

3.5. Vital Relations in Blending

A key to understanding blending and compression is a set of commonly engaged terms known as “vital relations”, identified by Fauconnier and Turner. A partial list of these relations is as follows: Change, Identity, Time, Cause-Effect, Part-Whole, Representation, Role, Similarity, Intentionality, and Uniqueness (Fauconnier and Turner 2002, p. 101). For example, the vital relation “Identity” may allow us to link children with the adults they will become.

As an example of blending with vital relations, Fauconnier and Turner describe an illustration that shows a dinosaur evolving into a bird through five different stages. The mind tends to imagine that a single dinosaur itself is transformed into a bird, which can then catch a dragonfly. The illustration strings and compresses vital relations including Time, Space, Cause-Effect, Change, Part-Whole, and Intentionality simultaneously. (Fauconnier and Turner 2002, p. 101). Even though we know that many individuals participated in the process of evolution over millions of years, the image compression allows us to more efficiently think about the process. Interestingly enough, Fauconnier and Turner argue that popular understanding of evolution has lagged because the vast time frame of billions of years does not fit well into a human scale.

Blends can bring different times and spaces and individuals together, and they can suggest causes. Intentionality is a vital relation often seen in religious thought. The compression of spaces may allow correspondences to be built between one space and another; for example, a primate on earth is linked to an angel in heaven. This is what happened when ideas from the biological chain of being became superimposed upon religious ideas about the transformation of humans into divine beings. The notion that we may eventually turn into something as “advanced” from us as we are from animals is both seductive and powerful.

Another commonly used vital relation is Uniqueness, which is at work both in the dinosaur–bird and the pronghorn chased by an extinct cheetah. A single individual is chosen to uniquely represent an entire species over thousands of years. Fauconnier and Turner propose that reincarnation is another compression into uniqueness, in that it suggests that individuals living in different time periods are the same person, without any particular element to indicate connection between the individuals (Fauconnier and Turner 2002, p. 118). Of course, believers in reincarnation would argue that there is a spiritual connection and that the individual share memories and even a soul.

An example of blending that applies vital relations was performed by the apostle Paul, who compared the Christian seeking salvation with an athlete running a race. “Do you not know that in a race the runners all compete, but only one receives the prize? Run in such a way that you may win it” (1 Cor. 9:24, NRSV). The blend applies the vital relations of Cause-Effect, Intentionality, and Uniqueness. The two input frames here are salvation through Christ, which is an abstract concept, and a contest of human speed. Paul urges steadfastness and effort by advising people to approach salvation as if they are athletes trying to win a race. The frames clash in the sense that a race has only one winner, while in the journey to salvation, each person may imagine success. Nevertheless, the blend works. In spite of the clash, it has inspired countless Christians to stalwart effort. In a similar way, we will apply vital relations to shed light on the mapping of salvation to evolution.

4. Analysis: What Survived? Comparing Evolutionary Theologies from the 19th to the 21st Century

Before evaluating the specific blends found in evolutionary theologies, I will review the elements of the systems of Blavatsky and Myers to see which persisted prominently in Roszak’s Aquarian Frontier, and what the governing principles of blending theory can explain about the success of certain blends over others.

4.1. The Aquarian Frontier and the Twentieth Century

Roszak’s 1975 Unfinished Animal provides an updated twentieth-century synthesis of various evolutionary visions, which reveals the influence a century later of both Blavatsky and Myers. He presents his study as “a survey and critique of the current religious revival in Western society, particularly with respect to its ethical and political implications” (Roszak 1975, p. 3).

He evaluates 145 groups (including 5 influenced directly by Blavatsky) and identifies broad trends. His categories range from Eastern religions to “Eupsychian Therapies,” which include Jungian, gestalt, and primal therapy. In other categories we find the Catholic paleontologist Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, the French Sufi René Guénon, the psychedelic pioneer Timothy Leary, and the Indian teacher Sri Aurobindo, as well as pioneers of the human potential movement.

The groups and thinkers along the Aquarian Frontier disagree(d) about a lot of things, most especially the question of an afterlife. One thing that unites them, however, is the agreement that mystical or extraordinary experience is important to life on Earth. Most also share a Hermetic sensibility and tend to use “evolution” to describe personal transformation. Another unifying factor Roszak identifies is the therapeutic. For the thinkers he discusses, “The way forward is inevitably the way inward” (Roszak 1975, p. 239).

Table 3 presents my summary and paraphrasing of the basic components of Roszak’s system, specifically as it relates to evolution. This list is a comparative tool to assist in our analysis. Although, admittedly, “Roszak’s system” is an arbitrary endpoint, it does provide a rough identification of the components of the most popular evolutionary theologies of the latter part of the twentieth century.

Table 3.

Roszak’s 1975 typology of metaphysical evolution on the “Aquarian Frontier” as presented in Unfinished Animal.

My summary is at best a partial condensation of Roszak’s themes, but it does provide a snapshot of the transformation of evolutionary theologies over a century. The Aquarian Frontier connects the nineteenth-century evolutionary theologies of Blavatsky and Myers with the previously mentioned, Deepak Chopra inspired, twenty-first century “Call to Conscious Evolution.” The language has been updated to accommodate twentieth-century values, yet seven of the nine elements of Roszak’s summary can be found in Blavatsky, Myers, or both. (Although Blavatsky and Myers are not the only sources of these ideas, they played a central role in creating the hyper-blend Evolution is Therapy.) Like Blavatsky and Myers, Roszak identifies deification and the pursuit of psychic powers as hallmarks of “evolution.” The marked similarity between some components of Myers and Blavatsky is a tribute to the “happiness” and stability of their blends, which means that they seem realistic and meaningful.

If we look at the individual elements of Roszak’s typology, we can see that of the nine points, the first two are common to Blavatsky and Myers. They can be seen as part of the network of religious responses to Darwin. The fourth point, the imitation of God and application of spiritual discipline, draws on Hermetic themes and is most closely related to Blavatsky’s work but can also be found in Myers’s idea of the secondary self as guide and teacher. The focus on mental discipline and training in the fifth through seventh points echoes the Theosophical tradition of adeptship, but also the psychological approach initiated by Myers.

The seventh point connects therapy with religion. According to my research, the historical origins of this narrative lie in the nineteenth century, where Blavatsky and Myers made important contributions. Blavatsky drew together common themes from Romantic nature religion and spiritualism. Myers performed ground-breaking theological work describing therapy as a religious duty, and introduced the “secondary self” as evolutive, therapeutic, and salvific.

Two elements on Roszak’s list not found in Blavatsky or Myers are the last two, ecological concerns and an overt emphasis on the erotic as a symbol of divine transcendence. These can both be explained as values that align with the hippie counterculture, with its free-wheeling attitudes towards sexuality. Though Myers did evoke the artistic eroticism of Plato, he did not explicitly identify sexuality as a gateway to transcendence. The overt connection of the erotic with evolutionary transcendence is a twentieth-century innovation, which also invokes Asian Tantric traditions. Jeffrey Kripal argues that the erotic was a hidden but essential ingredient in Myers’s work (Kripal 2010, pp. 86–91). Blavatsky did not write about sex or the erotic in a positive way, and this accounts for the clash of her blend with counterculture attitudes.

Another difference is that the system identified by Roszak is more this-worldly than that of Blavatsky or Myers. It deemphasizes—though it allows for the possibility of—both an afterlife and reincarnation. Its open-ended conclusion does not elaborate on either heaven or life after death. Thus, evolutionary theologies of the twentieth century, while clearly bearing a stamp of Blavatsky, Myers, and spiritualism, are more progressive and this-worldly. The ideas that persisted in the mainstream of Roszak’s Aquarian Frontier are those that follow the prime directive of blending theory, “achieve a human scale.”

The second governing principle apparent in evaluating the shift from Blavatsky to the twentieth century is the need for a story. Blavatsky did in fact tell more than one (conflicting) story. Her myths of the root races did have an influence outside her immediate circle, but the most theologically punitive elements, which incorporated elements of sexual guilt that clashed with twentieth-century thought, had been minimized. To the extent that they perpetuated themselves into the wider culture, they were softened in ever-more-technologically-advanced visions of the “lost” continents of Atlantis and Lemuria. Roszak calls for Blavatsky’s stories to be treated as a “mythical armature for supporting a godlike image of human nature,” and laments her “unfortunate literalism” (Roszak 1975, p. 122). This is quite a put-down for a woman who hoped to provide an alternative to biblical literalism. Nevertheless, the way she brought humans into a cosmic story was influential in a general way. She helped people to tell a new story, one that was largely in harmony with contemporary developments in geology, but which also put humans at the center.

The themes that came to dominate maintain a general harmony with principles of blending, including “compress what is diffuse,” “obtain global insight,” and “strengthen vital relations.” The connection of humans with lost talents from an animal or more primitive past, as originally framed by Blavatsky and Myers, offers a global insight that makes sense of connections between human and animal. Even though the individual may not be sure how his or her own life fits into the grand evolutionary scheme, the general notion that “evolution” can be achieved gradually in small steps by way of therapeutic techniques strengthens the vital relations of Uniqueness and Identity. An individual can imagine persisting through various “stages” of evolution and on into a transformed future state. This simplified story also resonates with the Purposeful Life is a Journey complex metaphor, which does not require a fixed endpoint, but merely motion along a path.

The Evolution as Therapy hyper-blend also opened the door to all kinds of ritual and therapeutic “technologies” or methods to be incorporated into a salvation scheme outside of organized religion. This is an idea that could only have taken root during the retreat of organized religion since it provides a rationale for practices that have been rejected by ecclesiastical authorities as magic and sorcery.

In the blend, advanced former humans sometimes take on the role of angels or Christ in Christian salvation. The notion of advanced beings providing guidance, whether former humans or extraterrestrials, has been promoted by some along the Aquarian Frontier as well as contemporary adherents of “conscious evolution” systems. In an era when many religious figures have become tainted by association with institutional religion, former humans seem more plausible guides. And yet traditional saints and divinities often do show up in personal transcendent experiences, as even a cursory read of the literature surrounding near-death experiences (NDEs) will attest. Blavatsky’s incorporation of the Hermetic divinized human into evolutionary salvation systems remains a key component because it reinforces and affirms the most basic aspects of great chain continuity. It bridges the gap between humans and divine or angelic beings, and this probably accounts for its persistence.

Finally, Roszak’s system strongly links evolution with therapy. Healing has of course been part of many religious systems. People go to religious practitioners to achieve relief from physical and mental ailments, and healing rituals abound across cultures. Yet evolutionary theologies incorporate the self as therapeutic practitioner in ways not seen in traditional religious settings. Roszak points out that Western religion abandoned the classical systems of physical culture. He includes upaya, a Sanskrit term that is used in Buddhism, to describe practices of transformation in his consensus list. Indeed, his “Aquarian Frontier” is characterized by a wide range of methodologies and techniques for approaching transformation by way of mental training and physical discipline. Some are attempting to restore Gnostic and Hellenistic rituals, which also incorporated a variety of therapeutic modalities (see DeConick 2016). The transformation of salvation into therapy by way of “evolution” has been so effective that most adherents do not stop to question it.

The seamless acceptance of a new concept demonstrates the success of blending, which can take the form of a revelation. Lakoff and Turner describe this type of sudden insight as the “power that metaphor has to reveal comprehensive hidden meanings to us, to allow us to find meanings beyond the surface, to interpret texts as wholes, and to make sense of patterns of events” (Lakoff and Turner 1989, p. 159). In the end, this power of metaphor can be used to help explain the persistence of evolutionary theologies, even though they are at odds with elements of evolutionary biology.

4.2. Network Analysis 1: Progressive Soul Evolution

Blavatsky’s evolutionary system creatively combined ideas from ancient Hermeticism, spiritualism, and biology in a blend that appealed to many of the intelligentsia of her day, including Frederic Myers.10 When the mapping is complete, what stands out in her system of progressive evolution of the soul, spirit, or monad (she was not consistent) is the following: the possibility that humans can recover lost vestigial and potential talents through steady effort and progress, and the idea that higher intelligences or advanced beings guide our transformation into godlike beings.

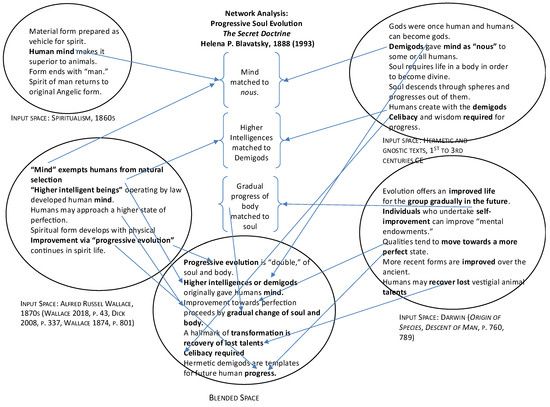

Figure 1 shows how Blavatsky performed theological transformation by three mappings (mapped terms are italicized below). First, she matched Wallace’s mind with Darwin’s mental endowments and the Hermetic mind, a philosophical concept known as nous. Of course, Blavatsky’s nous is not the same as the Hermetic nous. She was simply putting her own stamp on the tradition. In the nineteenth century, debates were raging as to which aspect of the human formed a “higher” faculty. Nevertheless, there was enough categorical similarity between the three concepts of mind that a blend could be attempted. Though Blavatsky associated mind with nous and the embodied divine spirit, she also saw salvation as the abandonment of the intellect in favor of intuition. The clashes made the blend a trifle “uneasy,”, i.e., not “happy,” in Fauconnier and Turner’s parlance, which left it open to be rerun by other thinkers in succeeding decades.

Figure 1.

Network analysis of Progressive Soul Evolution (Blavatsky 1993; Wallace 2018, p. 43; Dick 2008, p. 337; Wallace 1874, p. 801).

A second Hermetic mapping performed by Blavatsky linked Wallace’s higher intelligences with the Hermetic demigods, whom Blavatsky also associated with figures from other religions, such as the Hindu Pitris. These two mappings created a blend that feeds into later evolutionary theologies. Demigods, higher intelligences, and even extraterrestrials continue to play an important role in evolutionary theologies. One reason they persist is that they provide some of the comfort and security that a deity or savior offers, and the possibility of grace or aid when human effort fails. People who are put off by the idea of absolute dependence on a savior or God do retain elements of religious sensibilities, and may engage in prayer, ritual, and even divination (see Prophet forthcoming).

A third mapping connects ideas about gradual improvement from Darwin and biological evolution into a new complex blend of progressive soul evolution. This mapping succeeded and came to appear inevitable in later evolutionary theologies. Blavatsky’s soul evolution and root race system were attractive, but also contained enough unresolved clashes, particularly around asceticism and elitism, that they continued to be modified by future generations to improve their appeal.

4.3. Network Analysis 2: Salvation Is Evolution

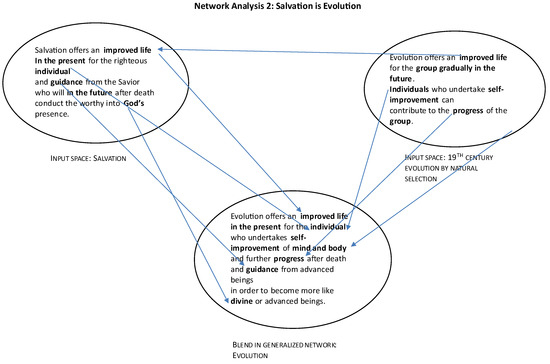

We have reviewed in this article a wide range of ideas that fed into the contemporary notion of evolution as a kind of destiny or duty that incorporates progressive and gradual self-improvement. Figure 2 looks for basic conceptual mappings from the domains of Christian salvation and nineteenth-century evolution. At work are a number of vital relations, including compressions of Time and Identity.

Figure 2.

Network analysis of Salvation is Evolution.

The first obvious mapping is improved life, which appears in both domains. In Christianity, at least in most denominations, life in the present is supposed to improve somewhat for the saved, but the real promise is in the afterlife. With nineteenth-century evolution, the improved life offered is for the species, but there is also room for individual self-improvement to gradually affect outcomes for the group. This gradual improvement maps into the generalized blend.

The mapping of self-improvement is assisted by the accessibility of notions of individual self-improvement from Lamarck and Spencer which persisted in nineteenth-century evolution. Individual self-improvement maps therefore from both nineteenth-century evolution and salvation. Another contribution that evolution makes to the blend is the notion of gradual progress, which may not be present in the salvation domain. A gradual and progressive improvement of mind and body is continued after death in the Salvation is Evolution blend.

An obvious compression of vital relations is between the individual (in the salvation input space), and the group (in the nineteenth-century evolution input space). Group improvement over thousands of years is compressed into individual improvement. Lamarckian evolution is about passing traits on to one’s children. Nevertheless, it remains useful to the Salvation is Evolution blend, when selectively mapped. Most evolutionary theologies are less about passing acquired characteristics to one’s descendants than about achieving personal improvement and transcendence for the individual in present and future lives.

Thus, what happens to the group in nineteenth-century evolution and to the individual in salvation is compressed into the individual in the evolution blend. Time is also compressed. Even if soul improvement is seen as taking place over hundreds of lifetimes, the blend folds what happens to multiple individuals over vast time spans into the individual experience over either a single lifetime or multiple lives in a shorter time span.

A final mapping from input to blended space is guidance from the savior in salvation to guidance from advanced beings in evolution. In addition, the evolution blend accepts a partial mapping of divine presence from Christian salvation, but the soul does not merely enter God’s presence but becomes more like divine or advanced beings. The evolution blend also contains elements of Hermetic and other divinization narratives, which are explored in Figure 3. However, Figure 2 shows the utility of the domain of biological evolution to enrich the more open-ended conceptions of salvation that were developing during the nineteenth century. One can see how and why the mapping came to seem automatic and even preferable to “salvation” in societies with active secularization during the twentieth century.

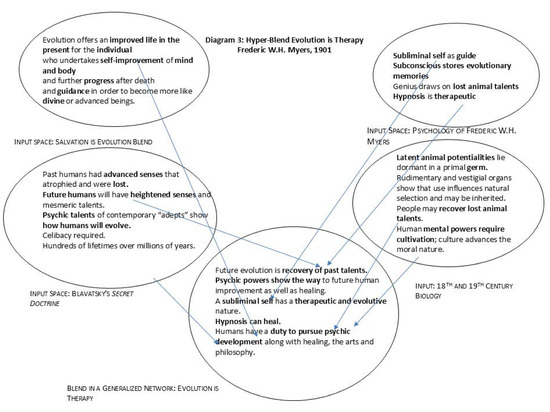

Figure 3.

Evolution is Therapy (Myers 1909).

4.4. Network Analysis 3: Evolution Is Therapy

Contemporary evolutionary theologies incorporate a wide range of modalities for improving the body, mind, and spirit. Some include rituals, contemplation, and incantation borrowed or updated from traditional religious systems. Others apply time-honored methods of trance induction, enhanced with psychotherapeutic techniques and, in the twentieth century, with psychedelics.

Figure 3 evaluates the components of the blend Evolution is Therapy as it began to emerge in the nineteenth century. Input spaces include the Salvation is Evolution blend, Blavatsky’s root race system, psychology, and nineteenth-century evolutionary biology, which also anticipated some recovery of lost animal talents. Though Blavatsky warned against developing these talents, they achieved their happiest blend in the work of Frederic W. H. Myers.

The cognitive science of religion and CMT have tended to focus on world religions, as well as God concepts. This study shows that attention can also be paid to syncretistic theologies that appeal to those who are disillusioned with organized religion.

The hyper-blend Evolution is Therapy contains elements of Salvation is Evolution together with material from the nineteenth-century psychology of Frederic W. H. Myers, who created a new blend promoting personal improvement, as well as selected elements from Blavatsky. Unlike Evolution is Salvation, it can be taken as a this-worldly practice, though Myers also thought that therapeutic evolution would continue after death. The blend requires compression of the vital relation of time and a mapping of identity from past human and animal forbears (who are seen as possessing heightened senses and psychic talents) to future humans.

Blavatsky first performed this mapping by linking past races with advanced senses to templates of future humans, and the psychic talents of contemporary adepts with a blueprint for future human development. However, Blavatsky warned that these talents should only be cultivated by a few worthy individuals. Myers enriched the blend by his own research into extraordinary human capacity, which includes artistic genius as well as the skills revealed under hypnosis. He connected the phenomena of hypnosis with healing, and postulated a subliminal self that was both therapeutic and promoted the “evolution” of the individual. Finally, he connected this evolution with a duty to pursue psychic development, the arts, and healing. He thus provided a template for the incorporation of therapeutic ritual into evolutionary religion, or religion as therapy for all, not only elites.

The metaphor spaces surrounding evolution that we have evaluated in this article could no doubt be mined further and more deeply for examples of conceptual blending. But this preliminary investigation has at least provided greater insight into the emergence of “evolution” as a form of secularized, therapeutic salvation.

5. Conclusions

This study shows that CMT and CIT can be fruitfully used to explain the nature and direction of theological change. By comparing the nineteenth-century evolutionary theologies of Blavatsky and Myers with the Aquarian Frontier of the 1970s identified by Roszak, we have engaged in a case study of the development of new theologies. We also briefly considered how these theologies have been extended into the twenty-first century through the thinkers engaged in a “Call to Conscious Evolution.” These systems remain attractive to individuals who are part of the New Age and SBNR movements, but also to the non-religious. They offer greater agency than orthodox Christianity, but still leave room for grace and a type of salvation through connection with “higher intelligences” and advanced former humans. In order to better understand the development of these theologies, we applied CMT and blending theory, or CIT. We analyzed three blends, Progressive Soul Evolution, Salvation is Evolution, and Evolution is Therapy, which encapsulate the new coinage of these thinkers. These systems can be encapsulated by the idea that “evolution” depends on the practice of spiritual discipline and/or the development and presentation of psychic and healing powers, in addition to other activities to improve life on earth. These three blends incorporate the nineteenth-century evolutionary biology of Darwin and Wallace; Blavatsky’s syncretistic root race system; Myers’s psychology and research into the phenomena of hypnosis; Wallace’s spiritualism; and ancient Hermetic texts as well as gnostic rituals.

According to the principles of conceptual metaphor theory, primary metaphors underlie complex metaphors. We have seen how two complex metaphors—The Great Chain of Being and A Purposeful Life is a Journey—were developed in a new direction by evolutionary theologies. The use of these metaphors can explain why these theologies seem reasonable and natural. For example, they allow us to imagine ourselves being transformed into future divine beings by analogy with our animal past.

Blending theory suggests why certain components of these theologies were more durable than others. The double-scope network of Progressive Soul Evolution as developed by Blavatsky was attractive but contained some elements of elitism, long time frames, and sexual guilt that were largely dropped as time went on and the blend was continually refined by later thinkers. One explanation for clashes in the blend has to do with its failure to maintain a human scale. The double-scope blend Evolution is Salvation mapped concepts from biology and theology into a new and seemingly secular type of personal transformation. The hyper-blend Salvation is Therapy proved to be the most “happy” and durable blend as it recurred along the Aquarian Frontier.

Although the analysis is interesting, it by necessity has had to ignore much historical work on the various transformations of Theosophy, psychology, and modern therapeutic salvation. There are clearly many other influences on the groups in the Aquarian Frontier and the signers of the “Call to Conscious Evolution.” However, it would be interesting to see studies from other disciplines testing neurological correlates of the use of “evolution” as a type of therapeutic salvation, and comparing it with more traditional concepts of salvation. The present study has only begun to analyze the belief systems that persist outside of the major religions, and may provide a foundation for future work in these areas.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgements

This research was begun during a graduate seminar at Rice University called The Bible and the Brain, led by April D. DeConick and sponsored by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Notes