1. Introduction

According to the latest 2022 Australian Bureau of Statistics, the Muslim population in Australia has seen significant growth, rising from 1.7% to 3.2% of the total population between 2006 and 2021, with projections suggesting it could surpass 1.5 million by 2050. This signifies that the Muslim community in Australia remains the fastest-growing faith community, along with the Sikhs moving into second position.

This growth inadvertently led to greater ethnocultural and ethnoreligious contact in an increasingly atheistic Australian demography. Scholarly interest over the past two decades has focused on how the faith community globally is affected by various facets of society, such as the media (

Melnykova-Kurhanova et al. 2022), family institutions (

Hunter et al. 2012), health institutions (

Weiss 2021), and the education system (

Hemming 2018;

Saada 2022), and how they affect the perception and attitude of Muslims in general. Representation of Muslims as a threat resurfaces, especially when there is a shortage of scapegoats, when ethnocultural and ethnoreligious conflicts emerge (

Aziz and Esposito 2024;

Velasco González et al. 2008).

Recent research has shown that majority and minority status groups differ in their focus during intergroup interactions (

Barlow and Sibley 2018). First, whereas the majority group members are aware of their own prejudices towards the minority groups in contact situations, minority group members tend to be more concerned about being the targets of such prejudice. Second, minority group members tend to think of themselves in terms of their own group membership more than majority group members do and tend to be aware of their group’s devalued status (

Habtegiorgis et al. 2014). Third, the intergroup attitudes of minority group members are often based on the anticipation of prejudice from the majority group, whereas intergroup attitudes of majority group members tend to be based on their own perceptions and beliefs (

Ata 2020;

Koenig 2005;

Sherman et al. 2009). The importance of context, therefore, cannot be underplayed.

Present literature has established that attitudes towards religious and ethnic minorities in Australia are, at best, inconsistent and highly dependent on the various circumstances at play (

Ata 2020;

Ata et al. 2009;

Lee et al. 2013;

Yip et al. 2019). Therefore, intergroup contact and relations are dynamic and require in-depth contextualization, as with any studies looking into the positioning and projection of the Muslim community in the larger Australian populace. Despite being a major world religion, Islam is not well understood nor accepted, often treated with suspicion and a sense of exoticism (

Kende et al. 2018;

Vezzali et al. 2020). Despite the many shared theological roots and tenets that Islam shares with Christianity, these similarities rarely facilitate closer interfaith relations (

White et al. 2014). As with many other minority groups, Muslims remain sidelined in the periphery, which in turn reinforces attitudes and perceptions towards them that impede greater societal integration.

It makes sense that in Australia and other Western countries, the separation between one’s religious and public identities is a cultural and political given. Australians may have been influenced by Christian values, but, unlike citizens of Muslim countries, their identity is not interchangeable with their religious affiliation. That said, significant differences between the two religions, Christianity and Islam, are not to be side-stepped. This could lead to a false sense of security. Differences in interpretation of social values and way of life, individual accountability, consensual decision-making, and attitudes towards implementing moral imperatives do exist. It is feasible that we should be able to acknowledge them, respect them, and address them without necessarily aiming for compromise.

2. Appraisal of the Research Objectives and Associated Questions

Significant attention was devoted to describing the intergroup interactions of majority and minority groups. Most interactions were negatively characterized by discriminatory undertones that the dominant group exhibits. In contrast, the minorities were conscious of being the recipients of said undertones, leading to a defensive positioning of the self and, by extension, of the minority community within the larger populace (

Habtegiorgis et al. 2014). The intergroup attitudes of the dominant group, on the contrary, are largely driven by both their own beliefs and perceptions of minorities (

Lee et al. 2013).

What makes these positions intriguing is the socio-psychological factors that catalyze them. Mass and social media are often cited as some of the most influential modifiers of intergroup attitudes, perception, and knowledge (

Pettigrew et al. 2007;

Schumann et al. 2014). They have often contributed to negative perceptions of religious and ethnic minorities, such as the portrayal of Islam and Muslims following the 9/11 attacks and the Bali bombings in 2004. Yet, their treatment and definition of religious or faith-driven atrocities were biased; for instance, Western media (Australia notwithstanding) received strong rebuke for their habitual reporting on the 2019 Christchurch shooting, focusing on the background and upbringing of the perpetrator (

Ellis and Muller 2020;

Every-Palmer et al. 2021;

Hunt et al. 2019). Such biased ethnic and religious representation by the mass and social media inadvertently inhibits a more prevalent social integration of Muslim minorities in Australia, which is something this study was keen to investigate.

Also, there is limited work investigating the role that religious knowledge plays concerning interfaith attitudes and perceptions. Misguided religious facts perpetuate negative attitudes, justify subtle and blatant discrimination, and calcify social distance, which are commonly accepted views (

Ata et al. 2009), although recent studies have also suggested that their role is insignificant among highly educated individuals (

Teh and Ata 2022), where knowledge does not predict intergroup contact. One emerging theory, resulting from the findings of (

Teh and Ata 2022), is that religious knowledge, be it extensive, limited, or non-existent, is more pronounced in the layperson, where their tolerance and acceptance are more dependent on the awareness of the existence of the “other”. This theory consolidates the proposition to introduce greater heterogeneity of topics and themes in religious and civic studies in primary and secondary education (

Preger and Kostogriz 2014). However, religious knowledge is far from fundamental for individuals in tertiary institutions.

Therefore, this study captures responses from university non-Muslim and Muslim students, an area that is rarely discussed. These tertiary education institutions are also one of the few places in which individuals of different faith communities congregate together, thus becoming a microcosm of the larger Australian society. Though unable to fundamentally represent the general populace, this presents an interesting starting point on which to orient towards highly educated participants whose input may prove insightful and relevant moving forward. In a way, the current participants were asked how Muslims were perceived and portrayed by non-Muslims and Muslims alike as mediated by various factors such as mass media, educational secular institutions, and religious knowledge. Also, it is pertinent to see if interfaith contact, also known as social distance, is affected by said perception and portrayal.

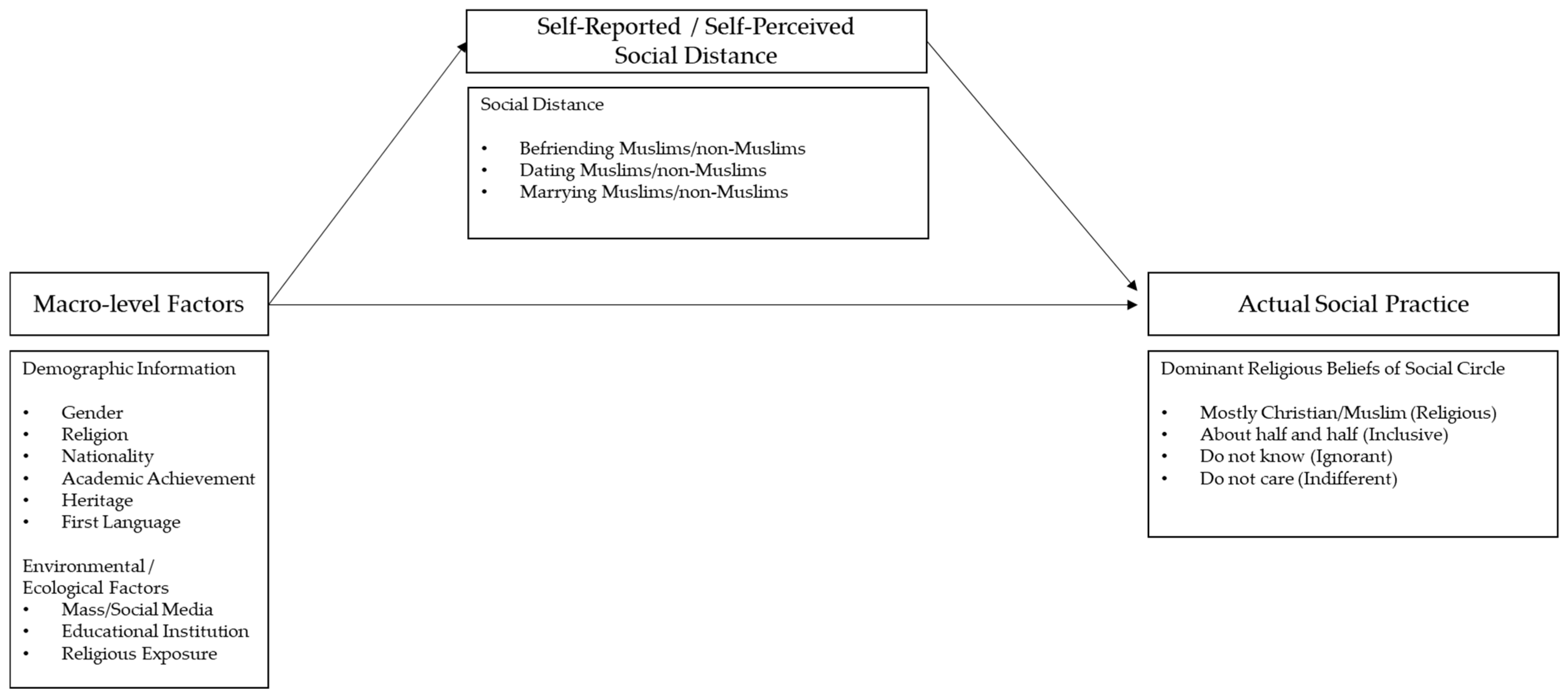

The main objective of this study is, therefore, to extrapolate the various potential demographic and environmental factors of non-Muslims and Muslims towards each other and how they manifest themselves in actual social practice. This study seeks to conceptualize how these macro-level factors (namely, demographic and ecological factors) translate into perceived social distance towards “others” and how this is expressed in real-life social practice. Therefore, the research objectives and questions of this study were developed to determine if any inherent relationship exists between macro-level factors and social distance. Answering research questions 3, 4, and 5 will require rejecting their corresponding null hypotheses:

Research Objectives:

To determine if macro-level factors influence self-perceived social distance and actual social practice with individuals of different faith communities among tertiary students in Australian universities.

Research Questions:

- (1)

What is the self-reported/self-perceived social distance of tertiary students in Australian universities with individuals of different faith communities according to their demographic and ecological background?

- (2)

What is the actual social practice of tertiary students in Australian universities with individuals of different faith communities?

- (3)

Do self-perceived social distance, perceived media influence on intergroup contact, and perceived influence of educational influence vary according to the respondents’ demographic background?

3H Self-perceived social distance, perceived media influence on intergroup contact, and perceived influence of educational influence vary according to the respondents’ demographic background.

3H0 Self-perceived social distance, perceived media influence on intergroup contact, and perceived influence of educational influence do not vary according to the respondents’ demographic background.

- (4)

Does self-perceived social distance of tertiary students from different faith communities in Australian universities mediate socio-ecological background and their actual social practice?

4H Self-perceived social distance of tertiary students from different faith communities in Australian universities mediates socio-ecological background and their actual social practice.

4H0 Self-perceived social distance of tertiary students from different faith communities in Australian universities does not mediate socio-ecological background and their actual social practice.

- (5)

Are there any macro-level factors that significantly mediate the socio-ecological background of tertiary students of different faith communities in Australian universities and their actual social practice?

5H There are macro-level factors that significantly mediate the socio-ecological background of tertiary students from different faith communities in Australian universities and their actual social practice.

5H0 There are no macro-level factors that significantly mediate the socio-ecological background of tertiary students from different faith communities in Australian universities and their actual social practice.

Figure 1 below depicts the conceptual framework that guides the investigation of this study.

3. Survey Method and Sample Characteristics

The current study provides a unique position where the intricate relationship between religious beliefs and their impact on socialization is empirically and statistically scrutinized. It is part of a larger investigation where (i) non-Muslim Australians’ attitudes and perceptions of Muslims and (ii) Muslim Australians’ attitudes toward and perceptions of non-Muslim Australians were explored. Where previous studies analyzed interfaith relations from a homogenous perspective, this paper embraces a heterogenous position, looking at how non-Muslim and Muslim Australians, as a collective, perceive and behave towards each other.

The present study investigated the macro-factors against the non-Muslim and Muslim Australians’ self-reported social distance, which transpired in social distance, and how this translates into real-life, concrete social practices. This study is a rare attempt to depict the intricate effect of macro-level factors on the individual’s self-perceived social distance and actual social practice, which no other studies have attempted before. A multifaceted questionnaire that reflects the proposed conceptual framework (

Figure 1) was utilized to capture a quantitative and descriptive analysis of tertiary students from six major universities in Victoria and New South Wales, Australia. The responses collected were direct and anonymous, which are reflective of present undercurrents of intergroup interaction and contact, where interethnic and interfaith relations and policies on immigration and hate speech began dominating sociopolitical discourses (

Ewart et al. 2017;

Rabasa and Benard 2015). Anchoring the study in academia among tertiary students provides an alternative understanding of how they reacted to said undercurrents. Considering the significance of these respondents as future leaders in politics, economics, and STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics), their responses could be far more telling and indicative of future intergroup contact and needs, something that many other studies in non-academic settings are ill-equipped to achieve.

Table 1 below depicts the demographic information of the respondents (N = 331).

A structured questionnaire was the primary data collection instrument for this comparative study. The questionnaire contained 40 items capturing demographic information, attitudes toward and perceptions of religious knowledge, and social practices of the respondents. The questionnaire was distributed randomly at various on-campus locations before being digitized and computed into Excel Worksheet and JASP version 0.19.3 (

JASP Team 2025). The items were worded so that the respondents reported their attitude, perception, and social distance with people of different religious affiliations than themselves, depending on whether they declared themselves non-Muslims or Muslims. In particular, the items measuring the respondents’ Social Distance are derived from Bogardus’ Social Distance Scale (

Bogardus 1933).

The questionnaire contains a total of four different domains, namely: (a) Demographic information, (b) perceived media portrayal of Islam and Muslims, (c) perceived educational influence on interfaith relations, and (d) self-reported social distance. The respondents provided information about themselves and rated how Islam and Muslims were depicted in mass and social media. Then, they evaluated the efforts of various educational institutions in fostering interfaith contact and relations. Finally, they reported the perceived social distance they harbor against the “other”; non-Muslims rated their willingness to befriend, date, and marry Muslims and vice versa. Potentially significant relationships between domains emerged and were investigated, which ultimately helped to address the research questions of this study.

4. Results

4.1. RQ1: What Is the Self-Perceived Social Distance of Tertiary Students in Australian Universities with Individuals of Different Faith Communities According to Their Demographic and Ecological Background?

Table 2 below illustrates the descriptive statistics concerning the respondents perceived ecological factors and self-reported social distance towards individuals of different faiths.

A quick reading of the descriptive statistics indicated a willingness to befriend (M = 2.74), date (M = 2.812), and marry (M = 2.653) individuals of another religion (MOverall = 2.734). This willingness was despite a slightly negative assertion of how Islam and Muslims were portrayed in mass and social media (M = 3.147) and how schools and universities had unsuccessfully promoted better interfaith relations (M = 3.408).

4.2. RQ2: What Is the Actual Social Practice of Tertiary Students in Australian Universities with Individuals of Different Faith Communities?

However, how macro-level factors and perceived social distance manifest in actual social practice remains abstract.

Table 3 depicts the dominant religious beliefs of their social circle, where their choice of social circle represents their actual social practice (in befriending individuals of different faiths).

The crosstab analysis showed that the respondent’s choice of friends is significantly distinct between non-Muslim and Muslim respondents, x2(4) = 166.23, p < 0.01. What is immediately apparent is a tendency for the respondents to associate themselves with individuals of similar faith (Mostly Christians, n = 64; Mostly Muslims, n = 49). The corresponding Cramer’s V indicated a large effect size (V = 0.739). One key difference lies in non-Muslim respondents’ tendency to be indifferent towards their associates’ faith beliefs (Do not care, n = 73), whose frequency surpassed that of befriending fellow non-Muslims (Mostly Christians, n = 64). This means that Muslim and non-Muslim respondents befriend individuals of similar faith backgrounds, although non-Muslims were far more likely to be indifferent towards the religious beliefs of their immediate social circle.

Considering the significant effect of the respondent’s religious beliefs on their choice of associates, the Chi-Square Test of Independence and Spearman’s rho correlation analysis were conducted as a measure of association between variables.

Table 4 illustrates the results of the analysis. Of the many demographic factors, only the respondents’ academic qualification is not significantly independent of their choice of social circle. Likewise, the respondent’s perceived social distance was similarly negatively associated with their choice of association (

r = −0.179,

p < 0.01), though a detailed breakdown analysis indicated that only befriending Muslims/non-Muslims (

r = −0.195,

p < 0.01) and marrying Muslims/non-Muslims (

r = −0.177,

p < 0.01) were significantly associated with their social group type.

The correlational findings were used as a form of exploratory analysis to inform the subsequent investigation. Following this, a multinomial logistic regression investigated the relationship between these significant correlations. The dominant religious belief of the respondents’ social group was designated as the dependent variable, with the demographic variables of educational influence and religion as independent variables. The social distance variables of befriending were computed as covariates. The generated findings are displayed in

Table 5.

The multinomial logistic regression analysis, x2(28) = 278.488, p < 0.01, indicated that the demographic variables religion, gender, and home language, along with covariates and social distance, significantly predict the social circle type. The reported McFadden pseudo-R2 value is 0.294, indicating that the predicted model is a relatively excellent improvement over the null model. This analysis confirms that these demographic variables and their preference for or against befriending, dating, and marrying individuals of other faiths are potentially reliable predictors of their actual social practice, evident from their choice of social circle. The subsequent step is to scrutinize the exact relationships between these variables.

4.3. RQ3: How Do the Tertiary Respondents’ Self-Perceived Social Distance, Perceived Media Influence on Intergroup Contact, and Perceived Influence of Educational Influence Vary According to Their Demographic Background?

To address research question 3, tests of mean differences, paired sample

t-tests, were conducted involving several demographic variables, of which several significant findings emerged. The independent

t-test analysis between religion and social distance (

Table 6) demonstrated significant differences in social distance reported by respondents of different religious beliefs. Here, we observed greater heterogeneity in the self-perceived social distance. Non-Muslim respondents indicated greater willingness to befriend (m = 2.438, SD = 1.209) and marry individuals of other faiths (m = 2.029, SD = 1.035) compared to Muslim respondents (m = 3.457, SD = 1.373; m = 4.202, SD = 1.035). On the contrary, they (m = 2.900, SD = 1.299) were less willing to date individuals of other faiths compared to their Muslim counterparts (m = 2.468, SD = 1.299). Overall, non-Muslim respondents (m = 2.453, SD = 1.025) reported a closer social distance with the “other” compared to Muslim respondents (m = 3.376, SD = 0.710).

Other noticeable differences were detected between the respondents’ religion and their perceived media portrayal of Islam, t(304) = −3.122, p < 0.01, and educational influence on intergroup contact, t(304) = −4.574, p < 0.01. Unsurprisingly, Muslim respondents tend to agree that media portrayal of Islam remains largely negative and disconnected from reality (m = 2.947, SD = 1.009) more than non-Muslims (m = 3.233, SD = 0.585). The disparity between Muslim and non-Muslim respondents’ perception of educational influences on their intergroup contact is slightly less pronounced, t(304) = −4.574, p < 0.01. Muslim respondents (m = 3.173, SD = 0.676) are of the opinion that their universities had better programs to facilitate intergroup contact compared to their non-Muslim counterparts (m = 3.515, SD = 0.567).

The independent

t-test analysis between gender and social distance (

Table 7) also showed that there are significant differences in social distance reported by respondents of different genders. Across the board, the male gender seemingly was more open towards befriending,

t(327) = −2.219,

p < 0.05, dating,

t(326) = −2.453,

p < 0.05, and marrying individuals of different faith groups,

t(327) = −4.515,

p < 0.01. Comprehensively speaking, the male respondents (m = 2.404, SD = 0.098) reported closer social distance with the “Other” compared to their female counterparts (m = 2.897, SD = 0.980),

t(327) = −4.239,

p < 0.01.

ANOVA tests involving demographic variables such as heritage and home language against social distance also yielded some interesting findings. There are significant differences in the respondents’ social distance when grouped according to their heritage,

f(2, 324) = 17.569,

p < 0.01,

η2 = 0.098 (see

Table 8), and home language,

f(2, 327) = 38.085,

p < 0.01,

η2 = 0.189 (see

Table 8). Post Hoc Tests reported significant differences in social distance between (i) Australian and mixed-heritage Australians (M

1 − M

2 = −0.430, 95% CI [−0.855, −0.025]) and (ii) Australian and non-Australian groupings (M

1 − M

3 = −0.717, 95% CI [−1.051, −0.433]). Likewise, there are also significant differences between respondents: (i) From English language only households compared to from non-English language households (M

1 − M

2 = −0.834, 95% CI [−1.340, −0.329]), and (ii) English language only households compared to multilingual households (M

1 − M

3 = −0.896, 95% CI [−1.143, −0.649]).

Considering these findings, the 3H0 null hypothesis is, therefore, rejected, and the alternate hypothesis, 3H, is accepted.

4.4. RQ4: Does Self-Perceived Social Distance of Tertiary Students from Different Faith Communities in Australian Universities Mediate Socio-Ecological Background and Their Actual Social Practice?

To answer research question 4, a null hypothesis was framed and tested via a mediation analysis. The analyses were conducted on the variables identified from the regression analysis in tandem with the proposed conceptual framework (

Figure 1) using JASP Version 0.19.3 (

JASP Team 2025). This mediation analysis was conducted to examine whether the effects of the macro-level factors (i.e., choice of religion) on their actual social practice (i.e., befriending individuals of other faiths) were mediated by their perceived social distance (self-reported willingness to befriend individuals of other faiths). Bootstrapping with 5000 samples was used to generate confidence intervals for the indirect effects.

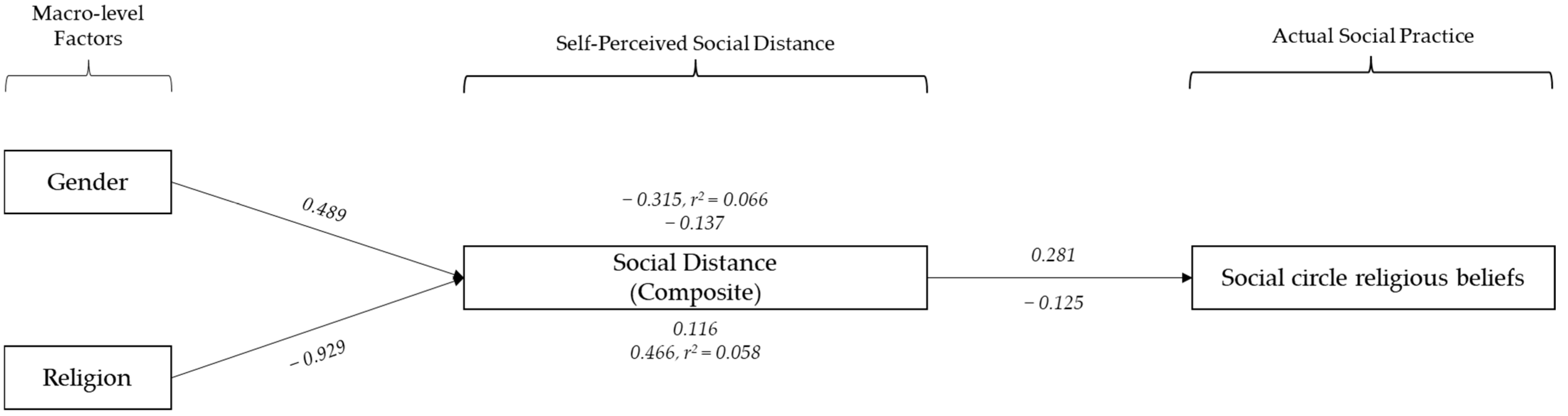

Two significant mediation models emerged.

The first mediation model demonstrated that the self-perceived social distance fully mediates one’s religion and the religious composition of their actual social circle. The respondents’ religion does not significantly predict their actual social circle, b = 0.350, SE = 0.225, p > 0.05. It is, however, a significant predictor of the respondents’ self-perceived social distance, b = −0.929, SE = 0.144, p < 0.01. Likewise, said social distance also significantly predicts the composition of their actual social circle, b = −0.125, SE = 0.060, p < 0.05. Bootstrapping further revealed a significant indirect effect of the respondents’ religion on their actual social circle mediated by their tendency to befriend individuals of other faiths, b = 0.116, SE = 0.056, 95% CI [0.006, 0.226], indicating full mediation. This model explains 5.8% of the variance in their choice of intergroup association, b = 0.466, SE = 0.217, p < 0.05.

The second mediation model also resonates with the first mediation model, where the respondents’ self-perceived social distance fully mediates their gender and the religious composition of their actual social circle. While gender is not a direct predictor of their actual social circle, b = −0.177, SE = 0.163, p > 0.05, it significantly predicts their social distance with individuals of other faiths, b = 0.489, SE = 0.121, p < 0.01. Concurrently, said association also likely predicts the religious composition of their actual social circle, b = −0.281, SE = 0.067, p < 0.01. Bootstrap analysis confirmed a significant indirect effect between gender and their actual social circle mediated by their choice of association with individuals of other faiths, b = −0.137, SE = 0.049, 95% CI [−0.274, −0.065], again demonstrating full mediation. This model explains up to 6.6% of the variance in their choice of association, b = −0.315, SE = 0.151, p < 0.05.

In short, the mediation analysis assessed the relationship between the respondents’ socio-ecological factors, such as religion (Muslim or non-Muslim) and gender (male or female), and their actual social practice (represented by the dominant religious beliefs of their social circle), which are fully mediated by their self-perceived social distance (represented by their tendency to befriend individuals of other faiths). The 4H0 null hypothesis is subsequently rejected, confirming that self-perceived social distance (namely, the tendency to associate with individuals of other faiths) of tertiary students from different faith communities in Australia fully mediates their socio-ecological factors (namely, religion and gender) and their actual social circle.

Figure 2 represents the synthesized mediation model along with its key statistics.

4.5. RQ5: What Other Variables Significantly Mediate the Socio-Ecological Background of Tertiary Students of Different Faith Communities in Australian Universities and Their Actual Social Practice?

To answer research question 5, a null hypothesis was framed and tested via a mediation analysis. Other socio-ecological variables are used to mediate other macro-level factors and actual social practice.

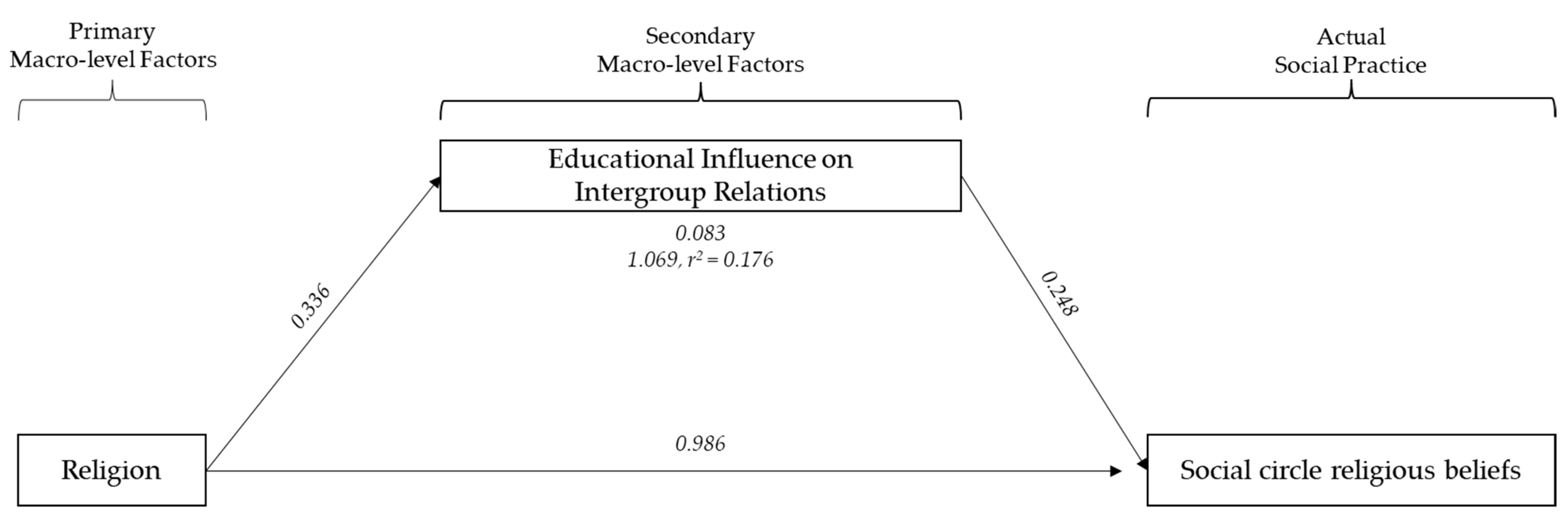

One significant mediation model emerged.

The mediation model demonstrated that the educational influence on intergroup relations partially mediates one’s religion and the religious composition of their actual social circle (see

Figure 3). The respondents’ religion significantly predicts their actual social circle,

b = 0.986, SE = 0.140,

p < 0.01, and their perceived educational influences on intergroup relations,

b = 0.336, SE = 0.083,

p < 0.01. Conversely, the respondents’ perceived educational influence on intergroup relations significantly predicts the composition of their actual social circle,

b = 0.248, SE = 0.107,

p < 0.05. Bootstrapping further revealed a significant indirect effect of the respondents’ religion on their actual social circle mediated by their perceived educational influence on intergroup relations,

b = 0.083, SE = 0.041, 95% CI [0.022, 0.205], indicating partial mediation. This model explains 17.6% of the variance in their choice of friends,

b = 1.069, SE = 0.118,

p < 0.01. In this model, the respondents’ faith, compounded with the educational influence, directly affects their social circle composition, though at the expense of social distance.

The small p-value signifies a lesser chance that the data support the null hypothesis. The 5H0 null hypothesis is therefore rejected, confirming that educational influence is a significant partial mediator of one’s religion and their actual social circle, thereby displacing social distance as a full mediator.

5. Discussion

The findings of the mediation analysis indicate that the proposed conceptual framework can significantly describe the relationship between extrinsic factors and the respondent’s choice of friends as mediated by social distance. They verify the initial assumption that demographic factors are potent instigators of actual social practice, whose relationship is also partially mediated by self-perceived social distance with a target group. This stance is observed and well established: widespread negative stereotypes in various media forms and ecological spheres have resulted in alienating Muslim communities away from positive images (

Ata and Sambol 2022).

In addition, the findings also suggest the possible existence of primary and secondary socio-ecological factors and the need to taxonomize socio-ecological factors as progenitors and moderators of actual social practice. The model predicts that socio-ecological factors can manifest as potent mediators of one’s religion and their actual social circle. This reinforces the important role that educational institutions play in mediating tertiary students’ relationships with the “other”, to the point that social distance no longer plays a significant role in intergroup contact.

Kahu and Nelson (

2018) proposed an educational interface combining intricate exchanges between students and institutions that influence engagement and success. They point out several social constructs that are crucial in the interactions between them, such as well-being, self-efficacy, and belonging. Advocating for the students’ psychosocial characteristics and engagement in such institutions is bound to provide an enriching focus on various programs that would nurture students’ abilities and learning outcomes. (See also

Gunness et al. 2023).

Of this paper’s many demographic and ecological factors, only the respondents’ religion and gender significantly influenced their self-perceived social distance and actual social practice. Respondents with highly religious social circles reported a clear preference against associating with individuals of different faiths. Take intergroup friendship, for instance. Muslims were mainly reluctant to befriend non-Muslims (M = 4.13), whereas non-Muslims were slightly less apprehensive (M = 4.00). However, non-Muslim respondents who were less concerned about the dominant religious beliefs of their social group registered a greater willingness to befriend Muslims (

r = −0.137,

p < 0.05). This observation highlights the religious differences as an existing and persisting threat to national identity and cultural continuity (

Smeekes and Verkuyten 2014), as the instinct towards in-group essentialism naturally overpowers the desire for intergroup contact. In actual practice, a minority of Muslim respondents befriend non-Muslims (N = 8), whereby one non-Muslim respondent reported a Muslim-dominated social group (N = 1). The independent sample

t-test analyses (

Table 6) had indicated that the perceived social distances were significantly different among different faith groups, where non-Muslim respondents (M = 2.44) were more likely to befriend Muslims (M = 3.46) rather than the other way around. This observation was despite Muslim respondents (M = 2.95) perceiving the media portrayal of Islam,

t(304) = −3.122,

p < 0.01, more positively than non-Muslim respondents (M = 3.23). Concurrently, the promotion of interfaith relations in educational institutions,

t(304) = −4.574,

p < 0.01, was rated less negatively among Muslim respondents (M = 3.17) compared to non-Muslim respondents (M = 3.52). Likewise, the male gender (M = 2.50) was more likely to befriend someone of another faith (

Table 7) than the female gender (M = 2.84). Non-Muslim male respondents largely fall into two extreme categories; they either stick to a religiously homogenous social group (31.53%) or they simply do not care (39.64%). Female respondents have a more even distribution, though they largely sought social circles that are more inclusive than being segregators. Instead of social distance, the choice of social circle is more likely influenced by the exposure to the “other” via their academic pursuits in educational institutions.

These findings suggest that actual social practice may not always reflect the individual’s perceived social distance, as many studies had previously implied (

Smeekes and Verkuyten 2014). This discrepancy is largely due to how previous studies treated social distance as a measurement of the respondent’s willingness to befriend others. This study has also demonstrated that socio-ecological factors, such as exposure to religious beliefs of the “other” via learning institutions, have an equally important effect in influencing intergroup contact, if not more. However, these were self-reported, and so a certain degree of bias exists. What is less subjective is the respondents’ actual social group composition, which this study had ascertained as a more reliable and valid reflection of how demographic and ecological factors may influence their choice of association. This methodological gap has also become the primary justification for the mediation analysis; we theorized that those other factors at play contributed to such a phenomenon. The mediation analysis thus showed that willingness to befriend Muslims/non-Muslims is a full mediator for one’s religion and his/her choice of social circle. However, the analysis has also indicated that educational influence on intergroup contact can replace social distance, which, in the case of this study, partially mediates between gender and the religious composition of their social circle.

This study made a conscious distinction between an individual’s perceived social distance and his/her actual social practice of befriending individuals of different religious beliefs. One’s willingness to befriend others is an intrinsic and innate desire subject to cognitive and affective processes. In the same manner, it is proposed that one’s religion strongly influences their choice of association, regardless of their social distance with others (

Atran and Norenzayan 2004;

Cao et al. 2019;

Hermans et al. 2007;

Wilcox and Wolfinger 2008). However, outliers that defy this observation also exist, where individuals associate themselves with individuals of different religious beliefs despite their professed faith. This outlying observation indicates that religion, an external and rule-governed institution, significantly influences the individual’s choice of friends (

Baral 2023;

Liu and Zhang 2013;

McCullough and Willoughby 2009;

Tariq and Adil 2020;

Tong et al. 2021). This study did not differentiate between religious and non-religious non-Muslims, but non-religious communities, atheistic and agnostic beliefs notwithstanding, are arguably an institution of their own, defined by their unique characteristics and principles, hence dogma-driven and highly regulated. Therefore, one’s religious beliefs will influence his/her desire to befriend and the actual act of befriending individuals of other faiths. In turn, the individual’s perceived social distance may further influence their actual act of befriending people of different faiths and beliefs. This paper argues that this, to a certain extent, represents the manifestation of the individual’s perceived social distance.

However, several key contentions remain:

Firstly, the data demonstrated that one’s perceived social distance is a full mediator of one’s professed religion and gender with their choice of social circle. This observation means that these factors are critical considerations when individuals bond with and befriend, date, and marry individuals of other beliefs. The best assumption at hand is that individuals’ socio-cognition, that is, the decision-making involved in perceived social distance, remains at the behest of socio-ecological factors, giving rise to the potential suppression of their (un)willingness to associate themselves with people of different faiths. These factors may combine with other due considerations such as career progression, ethical requirements, equity policies, etc. However, this study is not equipped to address these postulations with confidence.

Secondly, educational influence is a key socio-cognition factor, albeit one that is slightly less critical than social distance. This observation meant that educational influence on intergroup contact potentially overwrites or supersedes existing perceived social distance. Concurrently, this relationship suggested a causal relationship between religious and educational institutions. A positive take on this causality is the important role that educational (and secular) institutions play in counterbalancing or enhancing religious indoctrination of the church. A half-glass-empty interpretation of this observation casts a shadow on the inherent incompatibility of these two (secular and spiritual) institutions in encouraging and maintaining healthy and positive intergroup contact.

6. Conclusions

The findings presented in this study demonstrate the complexity and dynamism of intergroup contact, traditionally termed social distance, that has distinct implications for social integration. Whereas negative attitudes provide insight into the affective evaluation of a particular group, measures of social distance directly assess the impact of contact on the structural integration of groups. Given its inherently relational focus, this is an important direction for work on intergroup contact.

In relation to the response from mainstream (non-Muslim) Australian tertiary students, it was premised that significant differences would occur between gender and religious subgroups regarding all measurement tests. This observation was, unsurprisingly, present in this current study. The findings reveal that religion and gender are reliable indicators of one’s personal perception of individuals of other faiths, broadly termed as ‘the Other’. A supplementary finding, though no less important, also suggests that the religious (spiritual) and educational (secular) institutions are engaged in a causal relationship, potentially because religious upbringing tends to commence at home when formal education is usually a few years away. The perceived norms and out-group perceptions by tertiary students clearly play a pivotal role in explaining their relationship with members from other faith communities and the ease or retardation of integration of members of religious minority communities into the mainstream society.

Additionally, the survey found that respondents were not entirely convinced of the degree to which their educational institution is appropriately educating students about the faiths of various communities, hence why it has also emerged as a key socio-ecological mediator. However, it is also telling that this did not significantly predict their preference to befriend individuals of other faiths, though it also does shift the ethnoreligious makeup of their social circle according to their religious beliefs. Lastly, although the ecological factors may not significantly influence intergroup contact, future studies may want to investigate how and if these factors modify religious beliefs and views, which in turn may influence preferences for or against befriending individuals of other faiths and the religious makeup of their immediate social circle.