Elaborating Correlation with Space–Time in the Daoist Body: Following and Reversing Nature

Abstract

1. Rethinking Daoist Nature

2. Engaging the Web of Space and Time

2.1. Elaborating Resonance Systems of the Natural World

The Wind of Dictation resides in the Northeast and governs the emergence of myriad beings. … In the first lunar month, the pitch pipe is tuned to the key of “Great Cluster”. … In the twelve branches, it corresponds to yin 寅. The term yin signifies the beginning of life, likened to earthworms (yin 螾) emerging from the soil.

The Wind of Illuminating the Multitude resides in the East, … and illuminates all beings as they come forth. In the second lunar month, the pitch pipe is tuned to the key of “Intermingle and Affection”. … In the twelve branches, it corresponds to mao 卯. The term mao is derived from mao 茂, signifying the flourishing of all beings.

In the system of the ten stems, this period corresponds to jia 甲 and yi 乙. Jia signifies sprouting, as all things break through their shells and emerge. Yi 乙 signifies the struggle of life, as all things push forth with a creaking sound (yaya) as they are born.(Shiji, pp. 1245–46)

條風居東北, 主出萬物……正月也, 律中泰蔟……其於十二子爲寅. 寅言萬物始生螾然也……明庶風居東方……明衆物盡出也. 二月也, 律中夾鍾……其於十二子爲卯. 卯之爲言茂也, 言萬物茂也……其於十母為甲乙. 甲者, 言萬物剖符甲而出也. 乙者, 言萬物生軋軋也.

2.2. Celestial Markers and the Formation of Space–Time Concepts

3. Daoist Practices Aligned with the Natural Rhythm

3.1. Ritual Protocols and the Discovery of Singularity

3.2. Bodily Practices in Tune with Celestial Bodies

In the Lingbao tradition, there is a method of ingesting and controlling the Five Sprouts. The Five Sprouts are the generative qi of the Five Phases, which correspond to the original essences of the five internal organs. The scripture states, “Always, on the day of Beginning of Spring, at the dawn, enter the chamber, make nine bows to the East. Sit upright, click the teeth together nine times, and visualize the Green Numinous qi of the Florescent Forest of Pacified Treasure in the East—like the Venerable Lord Thearch and 90 million deities descending into the chamber, dense like clouds, covering your entire body. They enter through the mouth and descend directly into the liver and viscera.”(DZ402, 2: 22a–22b)15

靈寶有服御五牙之法. 五牙者, 五行之生氣, 以配五臟元精. 經云: 常以立春之日, 雞鳴時, 入室, 東向禮九拜, 平坐, 叩齒九通, 思存東方安寶華林青靈, 如老帝君九千萬人下降室内, 鬱鬱如雲, 以覆己形. 從口中入, 直下肝腑.

3.3. Collective Rituals of Rectification

4. Reversing and Rebooting the Natural Order

4.1. Internal Alchemy and the Inversion of Time

| Look upon the gate of death as the gate of life, | 但將死戶為生戶 |

| Cling not to the gate of Life, calling it death. | 莫執生門號死門 |

| One who understands the mechanism of causing death | |

| and sees the reversal, | 若會殺機明反覆 |

| Will come to realize: within harm, grace is born. | 始知害里卻生恩 |

| (DZ140, juan 6, 10a) | |

| Rising winds from the Three Mysterious [centers] | |

| bring forth the primordial green; | 揚風三玄出始青, |

| In the midst of formlessness, the pure numinous state is reached. | 恍惚之間至清靈. |

| At the Whirling Terrace, amid swirling play, red life is glimpsed | |

| —the birth of the Perfected. | 戲於飈臺見赤生, |

| Beyond all realms, true radiance shines forth, | 逸域熙眞餋華榮. |

| Nourishing the blossoms of immortal vitality. | |

| Inward gazing in silent stillness, refining the Five Forms within. | 内盼沉默鍊五形, |

| As the Three Qi revolve and circulate, | 三氣徘徊得神明. |

| Numinous clarity is attained. (DZ402, 43a-43b) | |

4.2. Cosmotechniques of Dissolution and Reconfiguration

| At this moment, purple glow enshrouds the peaks; | 於是, 紫霞靄秀 |

| Waves surge, mountains collapse. | 波激嶽頽 |

| Drifting vapors veil the forms; | 浮煙籠象 |

| Radiant chariots vanish into flight. | 淸景遁飛 |

| The Five Phases slaughter and clash; | 五行殺害 |

| The four seasons hurl and tangle. | 四節交擲 |

| Metal and earth embrace as kin; | 金土相親 |

| Water and fire lock in strife. | 水火結隙 |

| Forest and grasses fall flat; | 林卉停偃 |

| Hundreds of rivers burst and blocked. | 百川開塞 |

| Lightning rages, flashing in all directions; | 洪電縱橫而呴沸 |

| Thunder quakes the east and west, splitting the land. | 雷震東西而折裂 |

| The sign of Tun 屯 appears in the heavens, | 天屯見矣 |

| Becoming the calamity of the extreme Yang (yangjiu 陽九). | 化爲陽九之災 |

| The earth takes the form of Pi 否, closed and obstructed— | 地否閡矣 |

| Foretelling the encounter with the extreme Yin (bailiu 百六). | 乃爲百六之會 |

| (DZ1016, 6: 1b–2a) |

| There appear [the ghost army] | 爰有 |

| armored in fire and blazing cypress, | 火甲赫柏 |

| Diagrammed troops arrayed in dense formation. | 圖兵森羅 |

| Wielding halberds a hundred zhang long, | 執戈百丈 |

| They trample hills and overturn rivers. | 蹹阜傾河 |

| Heavenly guards and martial troops, | 天丁武卒 |

| Surge like countless coils of writhing snakes. | 萬萬蜲蛇 |

| Divine horse-women ride a thousand miles, | 女騎千里 |

| Dropping their feathers, drifting through the void. | 落羽浮虚 |

| Then—the Fire Bell is hurled aloft, | 仰擲火鈴 |

| Leaping into space in a burst of radiance. | 躍空晃流 |

| Flowing metal sweeps in reverse, | 流金逆激 |

| Splitting and dazzling the eight horizons. (DZ1389: 14a–14b) | 煥裂八嵎 |

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Huainanzi, Qisu xun 齊俗訓, p. 362. Besides Gengsangchu, the older explanation is found in Jingshang 經上 of Mozi 墨子, “Jiu is that which extends across different times; yu is that which extends across different places (久, 彌異時也. 宇, 彌異所也).” But here I introduced the phrase of Huainanzi, because its main theory was summarized as the words of Laozi in Wenzi文子 and was elevated to the status of a Daoist canonical scripture as the Tongxuan zhenjing 通玄眞經 in 742. |

| 2 | For a discussion on the Daoist scriptures as sacred beings and their performative activation through chanting and visualization, see Kim (2019b). For the performative characteristic of religious scriptures, see Watts and Yoo (2020). |

| 3 | For Daoist texts in general circulation (so-called “philosophical texts”) and those in internal circulation (so-called “religious scriptures” transmitted exclusively among Daoist priests) during the Tang period, see Schipper and Verellen (2004, vol. 1, pp. 283–84, 448–51). Since the Tang period, Laozi and Zhuangzi had acquired a firmly established status as canonical scriptures, bearing the formal titles Scripture of the Way and Virtue (Daode jing 道德經) and Authentic Scripture of Southern Florescence (Nanhua zhenjing 南華眞經), respectively. This canonical recognition was further reinforced during the Northern Song period. |

| 4 | Shiji 史記, Lüshu 律書, pp. 1244–48; The explanation based on phonetic similarity becomes more explicit in the Shiming 釋名, Shitian釋天 (Explanation on the Celestial Terms), juan1, 2b–3a. |

| 5 | Huangdi nejing suwen, Yinyang yingxiang dalun 陰陽應象大論 (Major Discourse on the Correlative Patterns of Yin-Yang). “天有四時五行, 以生長收藏, 以生寒暑燥濕風. 人有五臟化五氣, 以生喜怒悲憂恐. 故喜怒傷氣, 寒暑傷形. 暴怒傷陰, 暴喜傷陽.”. |

| 6 | Yang Quan, Wuli lun (Shiji, p. 1312). “歲行一次, 謂之歲星, 則十二歲而星一周天也.” Taisui tracks through twelve branches while the Jupiter tracks in reverse order. For the detailed discussion of Taisui and twelve branches, see Jung (2023, pp. 201–5). |

| 7 | Huinanzi, Tianwen xun, pp. 99–100. “斗指子則冬至; 指卯…春分; 指午…夏至; 指酉…秋分.” Chunqiu gongyang zhuan zyushu 春秋公羊傳註疏, juan 1, 8b. He Xiu 何休 commentary. “昏斗指東方曰春, 指南方曰夏, 指西方曰秋, 指北方曰冬.” See also Jung (2023, pp. 205–8). |

| 8 | Huainanzi, Tianwen xun, p. 110. “帝張四維, 運之以斗, 月徙一辰, 復反其所. 正月指寅, 十二月指丑, 一歲而匝, 終而復始.” |

| 9 | Shiji, Tianguan shu, p. 1291. “斗爲帝車, 運于中央, 臨制四鄉. 分陰陽, 建四時, 均五行, 移節度, 定諸紀, 皆繫於斗.” |

| 10 | Baopuzi neipian, Jindan 金丹 (Golden Elixir). “以王相日服之.” |

| 11 | Baopuzi neipian, Dizhen 地眞 (The Terrestrial Perfected). “受眞一口訣, 皆有明文, 歃白牲之血, 以王相之日受之.” |

| 12 | Baopuzi neipian, Xianyao 仙藥 (Immortal Medicine). “石芝者, ……擇王相之日, 設醮祭以酒脯, 祈而取之.” |

| 13 | Baopuzi neipian, Dengshe登涉 (Climbing and Crossing). “靈寶經曰, 所謂寶日者, 謂支干上生下之日也. 若用甲午乙巳之日, 是也. 甲者, 木也. 午者, 火也. 乙亦木也, 巳亦火也, 火生於木故也.” |

| 14 | Hanshu, Jiaosi zhi郊祀志, p. 1260. |

| 15 | The quotation is also found in many other Daoist texts, such as DZ1032 Yunji qiqian雲笈七籤 and DZ1017 Daoshu 道樞, juan. 8, 7b. |

| 16 | The preliminary cultivation methods belonging to the original Shangqing revelations (364–370) are preserved across multiple extant sources in the Daoist Canon. See the entry by Robinet in Schipper and Verellen (2004, vol. 1, pp. 144–46). I will mainly use DZ1377 and DZ405. |

| 17 | Also see DZ405, 9b–10b; DZ402, juan 2, 12a–13a. The method is often called as Wuchen fa 五辰法 or Wuchen xingshi jue 五辰行事訣, transmitted by Nanji yuanjun 南極元君. Haijun neizhuan summarized a different version of the Five Planets visualization (DZ1032, 105:2b). |

| 18 | It is titled as “Taishang huiyuan yindao yong chu zuiji neipian 太上迴元隱道用除罪籍内篇.” This method of the Return to the Origin is also found in DZ405, DZ423, DZ1362, DZ1377, etc. Zhengao records that Xu Hui 許翽 practiced it in 367 (DZ1061, 18:11b). “泰和二年太歲在丁卯正月, 行迴元道.” |

| 19 | DZ423, DZ1362, and the excerpted version in DZ1032 Yunji qiqian provide more than three versions of time regulation for the Nine Perfected visualization. DZ1362 uses reasonable time from the early morning to the evening (yin 寅to you 酉), in specific 2 or 3 days in the designated lunar months (1, 3, 4, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11). Yunji qiqian version (juan 30) designates only the time in one day from the dawn (dan 旦) to the midnight (zi 子). |

| 20 | DZ426, 19b–21a. The Five Penetration Days and Hours are as follows (Lunar Month-Date-Hour): 01-06-12, 02-01-15, 03-08-24, 04-09-07, 05-15-24, 06-03-12, 07-07-24, 08-04-12, 09-20-05, 10-01-05, 11-06-24, 12-12-24. On the Five Penetration days, in each of the twelve months, it is said that the deities residing in the Five Planets all ascend to the Heavens of Highest Clarity and Jade Clarity, where they meet the Supreme Lord of Dao in Ninefold Mystery Heavens (此十二月, 五星中上皇太眞道君, 俱登上清玉清, 見九玄太上道君). These days, moreover, are said to be auspicious gatherings for the elimination of sins and removal of misdeeds (夫五通者, 消罪除過之吉會). Quotation is also extant in Wushang miyao (9:3a–3b) and DZ1015 Jinsuo liuzhu 金鎖流珠, juan 12. |

| 21 | |

| 22 | |

| 23 | DZ141, Commentary of Xue Daoguang 薛道光 (1078–1191). “That which, by following [natural order], gives birth to living beings and human beings—this is the way after Heaven and Earth. That which, by opposing [natural order], leads to becoming a Transcendent or a Buddha—this is the way of the golden elixir before Heaven and Earth.” 如順則生物生人者, 是後天地之道也. 逆則成仙成佛者, 是先天地金丹之道也.” Chen Zhixu 陳致虛 (1290–1368?) “順行者, 世之常道也…逆行者, 仙之盜機也.” |

| 24 | DZ140, juan 6, 10a. “陰陽五行, 順之則生, 逆之則死, 此常道也…若能明此反覆之機, 則害裏生恩, 男兒有孕矣.” |

| 25 | |

| 26 | DZ13 Gaoshang yuhuang xinyin jing 高上玉皇心印經, 1a. “迴風混合, 百日功靈. 默朝上帝, 一紀飛昇.” For the development of whirlwind symbolism in the Song and Ming–Qing periods, see Kim (2015). In particular, the case of Yang You 楊攸 (fl. 1522–1566) illustrates the fusion of whirlwind visualization with internal alchemy (pp. 84–85). |

| 27 | Chuci 楚辭, Zhaohun 招魂. |

| 28 | DZ1016 Zhengao, juan 5, 4a. “仙道有流金之鈴, 以攝鬼神.” |

| 29 | DZ421 Dengzhen yinjue, juan 1, 9b–10a. “存明堂三君…口吐赤氣, 使光貫我身令帀, 我口傍咽赤氣, 唯多無數, 當閉目微咽之也. 須臾, 赤氣繞身者, 變成火, 火因燒身, 身與火共作一體, 内外洞光, 良久乃止. 名曰日月鍊形, 死而更生者也.” |

| 30 | Kim (2011). The text does not belong to the original fourth-century Shangqing text, nevertheless, this later work conveys the Shangqing imagination regarding the scope and transformative power of visualization. And it was certainly transmitted and practiced by Tang daoist masters (DZ1242, juan 2, 1a–1b). |

| 31 | DZ1203, 7b–8a. “瞑目内思, 己身吐炁, 炁化爲火光精流, 竟天鬱冥, 焚燒四方, 天下山林, 草木土地, 靈司人民, 悉令蕩盡. 竟天冥然, 無復孑遺, 洞達無涯, 火炁都消, 清炁鬱勃, 上則無天, 下則無地, 率天以下, 莫不歸宗於虚無.” |

References

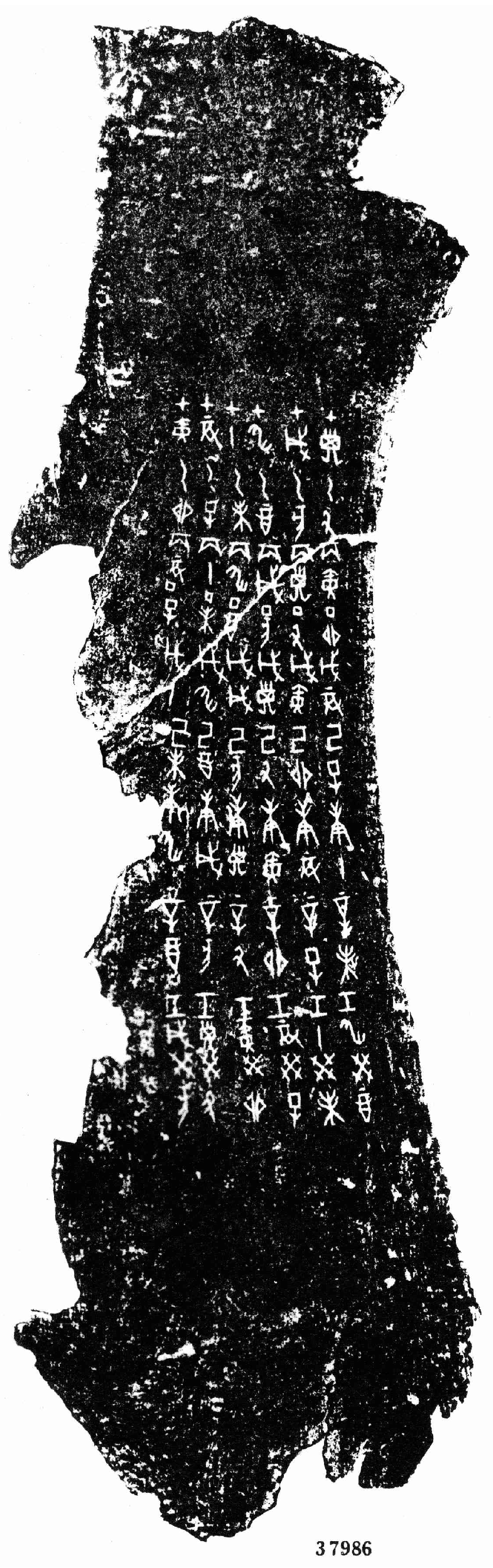

Primary Sources

Baopuzi neipian抱朴子內篇 [Inner Folios of the Master of Embrace Simplicity]. Ge Hong 葛洪. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju 中華書局.Chunqiu gongyang zhuan zhushu 春秋公羊傳註疏. He Xiu 何休 and Gong Yingda 孔穎達 (Shisan jing zhushu 十三經註疏, ed. Ruan Yuan 阮元). 1817. Taipei: Taiwan Yiwen yinshuguan 藝文印書館.Hanshu 漢書 [Book of Han]. Ban Gu 班固 et al. 1962. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju 中華書局.Huainanzi 淮南子 [Master of Huainan]. Liu An 劉安. (Huainan honglie jijie 淮南鴻烈集解 [Collected Annotations on the Huainan Honglie]. Liu Wendian 劉文典). 1989. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju 中華書局.Huangdi nejing suwen 黃帝內經素問 [Simple Questions in the Inner Scripture of the Yellow Emperor]. Commentary by Wang Bing王冰, Collated by Lin Yi 林亿, Sibuconggan四部叢刊 Edition.Jiaguwen hebian 甲骨文合編 [Collected Inscriptions on Oracle Bones] 2009. Beijing: Beijing daxue chubanshe.Shiji 史記 [Record of Grand Historian]. Sima Qian 司馬遷. 1959. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju 中華書局.Shiming 釋名 [Explanations on Terms]. Liu Xi 劉煕. Sibuconggan 四部叢刊 Edition.Wuxing dayi 五行大義 [Great Meanings of the Five Phases]. Xiao Ji 蕭吉 (Nakamura Shōhachi 中村璋八, ed. 1998. Gogyō taigi kōchū 五行大義校註, Tokyo: Kyūkoshoin 汲古書院).(DZ13) Gaoshang yuhuang xinyin jing 高上玉皇心印經 [Scripture of the Heart Seal of the Jade Emperor on High]. In Daozang 道藏 [Daoist Canon]. Shanghai: Hanfenlou Edition 涵芬楼版.(DZ140) Ziyang zhenren Wuzhen pian zhushu 紫陽眞人悟眞篇註疏 [Commentary and Explanation on the Awakening the Perfection of Ziyang Zhenren](DZ149) Xiuzhen taiji hunyuan tu 修眞太極混元圖 [Diagram of Cultivating Perfection through the Great Ultimate and Original Chaos].(DZ402) Huangting neijing yujing zhu 黃庭內景玉經註 [Commentary on the Jade Scripture of Inner Phosphors of the Yellow Court]. Commentary by Bai Lüzhong 白履忠.(DZ405) Shangqing zijing jun huangchu ziling daojun dongfang shangjing 上清紫精君黃初紫靈道君洞房上經 [The Highest Shangqing Scripture of Grotto Chamber of the Lord Dao of Purple Spirit of the First Moon and the Lord of Purple Essence](DZ421) Dengzheng yinjue 登眞隱訣 [Secret Instruction of Ascending the Perfected]. Edit. Tao Hongjing 陶弘景.(DZ426) Shangqing taishang basu zhenjing 上清太上八素眞經 [The Authentic Shangqing Scripture of Eight Purities of (the Lord) of Most High].(DZ615) Chisongzi zhangli 赤松子章曆 [Almanac for Petitions of Master Red Pine].(DZ745) Nanhua zhenjing zhushu 南華眞經註疏 [Commentary and Explanation of Authentic Scripture of the Southern Florescence]. Commentary by Guo Xiang 郭象 and Explanation by Cheng Xuanying 成玄英.(DZ1016) Zhengao 眞誥 [The Declaration of the Perfected]. Edit. Tao Hongjing 陶弘景.(DZ1017) Daoshu 道樞 [The Pivot of Dao]. Edit. Ceng Zao 曾慥.(DZ1032) Yunji qiqian 雲笈七籤 [The Seven Slips of the Cloud Bookcases]. Edit. Zhang Junfang 張君房.(DZ1203) Taishang santian zhengfa jing 太上三天正法經 [Scripture of the Orthodoxt Method for the Three Heavens of the Most High].(DZ1240) Dongxuan lingbao daoshi shou sandong jingjie falu zeri li 洞玄靈寶道士受三洞經誡法籙擇日曆 [Calendar of the Date Selection for the Daoist Transmission of the Three Cavern Scriptures and Registers in the Cluster of Cavern Mystery].(DZ1242) Chuanshou sandong jingjie falu lüeshuo 傳授三洞經戒法籙略說 [Brief Explanation of the Transmission of the Three Cavern Scriptures, Precepts, and Registers]. Zhang Wanfu 張萬福.(DZ1278) Dongxuan linbao wugan wen 洞玄靈寶五感文 [The Writs of Five Stimulations of the Numinous Treasure in Cavern Mystery]. Liu Xiujing 陸修靜.(DZ1376) Shangqing taishang dijun jiuzhen zhongjing 上清太上帝君九眞中經 [The Shangqing Scripture Central to the Nine Perfected of Lord Thearch of the Most High].(DZ1377) Shangqing taishang jiuzhen zhongjing jiangsheng shendan jue 上清太上九眞中經絳生神丹訣 [The Shangqing Instruction for the Divine Elixir of Vermilion Vitality from the Central Scripture of the Nine Perfected].(DZ1378) Shangqing jinzhen yuguang bajing feijing 上清金眞玉光八景飛經 [The Shangqing Scripture of the Eight Radiant Flights of the Golden Perfected in Jade Light].(DZ1392) Shangqing qusu jueci lu 上清曲素訣辭籙 [The Shangqing Register of (the Talismans) Incantatory Verses and the Entwined Purity].(DZ1389) Shangqing gaosheng taishang dadaojun dongzhen jinyuan bajing yulu 上清高聖太上大道君洞眞金元八景玉錄 [Jade Register of Eight Phosphors].Secondary Sources

- Ebine, Ryosuke 海老根量介. 2017. Shinkan no shakai to nissho o torimaku hitobito 秦漢の社會と「日書」をとりまく人々 [The Society of Qin and Han Periods and the People involved with Rishu]. Tōyōshi Kenkyū東洋史研究 [The Journal of Oriental Researches] 76: 197–237. [Google Scholar]

- Girardot, Norman J. 2011. Finding the Way: James Legge and the Victorian Invention of Taoism. Religion 29: 107–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girardot, Norman J., James Miller, and Liu Xiaogan, eds. 2001. Daoism and Ecology: Ways Within a Cosmic Landscape. (Religions of the World and Ecology, vol. 3). Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Harper, Donald. 2009. Daybooks in the Context of Manuscript Culture and Popular Culture Studies. In Books of Fate and Popular Culture in Early China. Edited by Mark Kalinowski and Donald Harper. Leiden: Brill, pp. 91–137. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Chun-Chieh, and Erik Zürcher. 1997. Cultural Notions of Space and Time in China. In Time and Space in Chinese Culture. Edited by Chun-Chieh Huang and Erik Zürcher. Leiden and New York and Köln: Brill, pp. 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, Jaesang. 2023. Godae Junguk ui sigan gwa gonggan gwannyeom ui hyeongseong gwa jeongae 고대 중국의 시간과 공간 관념의 형성과 전개–진辰의 의미를 중심으로 [Formation and Development of Space-Time Concepts in Ancient China: With a Focus on Chen’s Meaning]. Dogyo munhwa yeongu 道教文化硏究 [Journal of The Studies of Taoism and Culture] 58: 171–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Jihyun. 2011. Jōsei kei ni okeru mizu to hi no shinborizumu: Shugyō ron to kyūsai ron o chūshin ni 上淸經における水と火のシンボリズム—修行論と救濟論を中心に [Symbolism of Water and Fire in Highest Clarity Scriptures: Practice and Soteriology]. In Inyō gogyō no saiensu: Shisō-hen 陰陽五行のサイエンス: 思想篇 [Science of Yin-Yang and Wuxing: Thought Part]. Edited by Tokimasa Takeda 武田時昌. Kyoto: Kyoto University Institute for Research in Humanities, pp. 125–45. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Jihyun. 2014. Naiden ni okeru dōgyo syugyō no katei to sekai no kōjō 內傳にみる道敎修行の過程と世界の構造 [Daoist Practice and Structure of the World: Seen through Inner Biographies]. Jongyo wa munhwa 종교와 문화 [Religion and Culture] 26: 185–217. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Jihyun. 2015. The Invention of Traditions: With a Focus on Innovations in the Scripture of the Great Cavern in Ming-Qing Daoism. Daoism: Religion, History and Society 7: 65–117. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Jihyun. 2019a. Dogyo e yisseoseo jeombok ui jari 도교에 있어서 점복의 자리 [The Place of Divination in Daoism]. Jongyo munhwa bipyeong 종교문화비평 [The Critical Review of Religion and Culture] 36: 134–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Jihyun. 2019b. Daoist Writs and Scriptures as Sacred Beings: With a Focus on Cosmological Meaning. Postscripts 10: 122–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Jihyun. 2023. Hurunun siseon gwa gonggan seong: Dogyo jonsa rul jungsim uro 흐르는 시선과 공간성: 도교 존사存思를 중심으로. [Flowing Gaze and Spatiality in Light of Daoist Visualization]. Jongyo munhwa bipyeong 종교문화비평 [The Critical Review of Religion and Culture] 43: 231–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkland, Russel. 2001. “Responsible Non-Action” in a Natural World: Perspectives from the Neiye, Zhuangzi, and Daode jing. pp. 292–93. Available online: https://religion.uga.edu/sites/default/files/inline-files/ECO.pdf (accessed on 4 May 2025).

- Lagerwey, John. 2022. What Daoist ritual has to contribute to ritual studies. Studies in Chinese Religions 8: 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lü, Pengzhi. 2010. Daoist Rituals. In Early Chinese Religion II, Part 2: The Period of Division (220–589 AD). Edited by John Lagerwey and Lü Pengzhi. Leiden and Boston: Brill, vol. 2, pp. 1245–351. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, James. 2001. Respecting the Environment, or Visualizing Highest Clarity. In Daoism and Ecology: Ways Within a Cosmic Landscape. Edited by Norman J. Girardot, James Miller and Liu Xiaogan. Cambridge: Harvard University Center for the Study of World Religions, pp. 351–60. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, James. 2017. China’s Green Religion: Daoism and the Quest for a Sustainable Future. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pregardio, Fabrigio. 2006. Great Clarity: Daoist and Alchemy in Early Medieval China. Redwood City: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pregadio, Fabrigio. 2009. Awakening to Reality: The Regulated Verses of the Wuzhen Pian, a Taoist Classic of Internal Alchemy. Mountain View: Golden Elixir Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pregadio, Fabrigio. 2019. Taoist Internal Alchemy: An Anthology of Neidan Texts. Mountain View: Golden Elixir Press. [Google Scholar]

- Robinet, Isabelle. 1989. Original Contributions of Neidan to Taoism and Chinese Thought. In Taoist Meditation and Longevity Techniques. Edited by Livia Kohn and Sakade Yoshinobu. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan, pp. 297–330. [Google Scholar]

- Robinet, Isabelle. 1993. Taoist Meditation: The Mao-Shan Tradition of Great Purity. Translated by Julian Pas. Albany: State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Robinet, Isabelle. 2011. The World Upside Down: Essays on Taoist Internal Alchemy. Translated by Fabrizio Pregadio. Mountain View: Golden Elixir Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schipper, Kristofer. 1978. The Taoist Body. History of Religions 17: 355–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schipper, Kristofer. 1993. The Taoist Body. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schipper, Kristofer. 2001. Daoist Ecology: The Inner Transformation. A Study of the Precepts of the Early Daoist Ecclesia. In Daoism and Ecology: Way Within a Cosmic Landscape. Edited by Norman J. Girardot, James Miller and Liu Xiaogan. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, pp. 79–94. [Google Scholar]

- Schipper, Kristofer, and Franciscus Verellen, eds. 2004. The Taoist Canon: A Historical Companion to the Daozang. 3 vols. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Steavu, Dominic. 2016. Cosmos, Body, and Meditation in Early Medieval Taoism. In Transforming Void: Embryological Discourse and Reproductive Imagery in East Asian Religions. Edited by Anna Adreeva and Dominic Steavu. Leiden and Boston: Brill, pp. 111–46. [Google Scholar]

- Verellen, Fransiscus. 2004. The Heavenly Master Liturgical Agenda According to Chisong zi’s Petition Almanac. Cahiers d’Extrême-Asie 14: 291–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verellen, Fransiscus. 2019. Imperiled Destinies: The Daoist Quest for Deliverance in Medieval China. Cambridge: Harvard University Asia Center. [Google Scholar]

- Watts, James W., and Yohan Yoo, eds. 2020. Books as Bodies and as Sacred Beings. Sheffield: Equinox Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Kuang-Ming. 1997. Spatiotemporal Interpretation in Chinese Thinking. In Time and Space in Chinese Culture. Edited by Chun-Chieh Huang and Erik Zürcher. Leiden and New York and Köln: Brill, pp. 17–48. [Google Scholar]

- Yamada, Keiji 山田慶兒. 1999. Chūgoku igaku no kigen 中國醫學の起源 [Origin of Chinese Medicine]. Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten 岩波書店. [Google Scholar]

- Yamada, Keiji. 2002. Ki no shizen-shō 氣の自然相 [Natural Phase of Qi]. Tokyo: Iwanami shoten. [Google Scholar]

- Yamada, Toshiak 山田利明. 1999. Rikuchō dōkyō girei no kenkyū 六朝道教儀禮の硏究 [Studies of Daoist Rituals in Six Dynasties]. Tokyo: Tohoshoten 東方書店. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Jiyu. 2001. A Declaration of Chinese Daoist Association on Global Ecology. In Daoism and Ecology: Ways Within a Cosmic Landscape. Edited by Norman J. Girardot, James Miller and Xiaogan Liu. Translated by David Yu. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, pp. 361–72. [Google Scholar]

| Branch 干 | Direction and Month | Season | Meaning | Stem 支 | Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hai 亥 | NW 10 | Winter | [gai] Enclosure (該), Closer (閡), Storage (藏塞) | Ren 壬 | [ren] Pregnancy, Entrust (任) |

| Zi 子 | N 11 | [zi] Underneath Growth (滋) | Guai 癸 | [kui] Estimate (揆) | |

| Chou 丑 | 12 | [niu] Binding, Congestion (紐) | |||

| Yin 寅 | NE 1 | Spring | [yin] Emergence like earthworms (始生螾然). | Jia 甲 | Hatch, Sprout (剖符甲而出) |

| Mao 卯 | E 2 | [mao] Prosperity, Flourish (茂) | Yi 乙 | [yaya] Struggle to be born (軋軋) | |

| Chen 辰 | 3 | [shen/zhen] Lick (of clam’s foot), Vibration (蜄) | |||

| Si 巳 | SE 4 | Summer | [yi] Consumption of Yang qi (陽氣之已盡) | Bing 丙 | Shine, Brightness (of Yang way) (陽道著明) |

| Wu 午 | S 5 | [jiao/wu] Interaction, Interchange of Yin-Yang (陰陽交/仵) | Ding 丁 | Health (丁壯) | |

| Wei 未 | 6 | [wei] Completion, Fruition (萬物皆成, 有滋味) | |||

| Shen 申 | SW 7 | Autumn | [shen] Extension of Yin’s function to injure (陰用事, 申賊萬物) | Geng 庚 | Strengthen (by Yin qi) (陰氣庚萬物) |

| You 酉 | W 8 | Aging, Senility (老) | Xin 辛 | Stab, Renew (辛生) | |

| Xu 戌 | 9 | [mie] Quench, Extinguishment, Dying (滅) |

| Five Phases | Wood | Fire | Earth | Metal | Water | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yin-Yang | Yang | Yin | Yang | Yin | Yang | Yin | Yang | Yin | Yang | Yin |

| Ten Stems | Jia 甲 | Yi 乙 | Bing 丙 | Ding 丁 | Wu 戊 | Ji 己 | Geng 庚 | Xin 辛 | Ren 壬 | Gui 癸 |

| Twelve Branches | Yin 寅 | Mao 卯 | Si 巳 | Wu 午 | Chen 辰 Xu 戌 | Chou 丑 Wei 未 | Shen 申 | You 酉 | Hai 亥 | Zi 子 |

| Date | Opening Hour of the Celestial Gate (Three Harmonies) | Closing Hour of the Celestial Gate (Three Clashes) |

|---|---|---|

| Zi 子 | Hai 亥, Mao 卯, Wei 未 Si 巳, You 酉, Chou 丑 | Shen 申, Zi 子, Chen 辰 Yin 寅, Wu 午, Xu 戌 |

| Chou 丑 | Shen 申, Zi 子, Chen 辰 Yin 寅, Wu 午, Xu 戌 | Hai 亥, Mao 卯, Wei 未 Si 巳, You 酉, Chou丑 |

| Yin 寅 | Mao 卯, Wei 未, Hai 亥 Si 巳, You 酉, Chou 丑 | Mao 卯, Wei 未, Hai 亥 Si 巳, You 酉, Chou 丑 |

| Mao 卯 | Shen 申, Zi 子, Chen 辰 Yin 寅, Wu 午, Xu 戌 | Hai 亥, Mao 卯, Wei 未 Si 巳, You 酉, Chou 丑 |

| Chen 辰 | Mao 卯, Wei 未, Hai 亥 Si 巳, You 酉, Chou 丑 | Mao 卯, Wei 未, Hai 亥 Si 巳, You 酉, Chou 丑 |

| Si 巳 | Shen 申, Zi 子, Chen 辰 Yin 寅, Wu 午, Xu 戌 | Hai 亥, Mao 卯, Wei 未 Si 巳, You 酉, Chou 丑 |

| Wu 午 | Mao 卯, Wei 未, Hai 亥 Si 巳, You 酉, Chou 丑 | Mao 卯, Wei 未, Hai 亥 Si 巳, You 酉, Chou 丑 |

| Wei 未 | Shen 申, Zi 子, Chen 辰 Yin 寅, Wu 午, Xu 戌 | Hai 亥, Mao 卯, Wei 未 Si 巳, You 酉, Chou |

| Shen 申 | Mao 卯, Wei 未, Hai 亥 Si 巳, You 酉, Chou 丑 | Mao 卯, Wei 未, Hai 亥 Si 巳, You 酉, Chou 丑 |

| You 酉 | Shen 申, Zi 子, Chen 辰 Yin 寅, Wu 午, Xu 戌 | Hai 亥, Mao 卯, Wei 未 Si 巳, You 酉, Chou 丑 |

| Xu 戌 | Mao 卯, Wei 未, Hai 亥 Si 巳, You 酉, Chou 丑 | Mao 卯, Wei 未, Hai 亥 Si 巳, You 酉, Chou 丑 |

| Hai 亥 | Shen 申, Zi 子, Chen 辰 Yin 寅, Wu 午, Xu 戌 | Hai 亥, Mao 卯, Wei 未 Si 巳, You 酉, Chou 丑 |

| Five Phases | Conception 受氣 | Embryo 胎 | Cultivation 養 | Birth 生 | Bath 沐浴 | Garment 冠帯 | Occupation 臨官 | Peak 王 | Decline 衰 | Disease 病 | Death 死 | Burial 葬 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wood 木 | Shen 申 | You 酉 | Xu 戌 | Hai 亥 | Zi 子 | Chou 丑 | Yin 寅 | Mao 卯 | Chen 辰 | Si 巳 | Wu 午 | Wei 未 |

| Fire 火 | Hai 亥 | Zi 子 | Chou 丑 | Yin 寅 | Mao 卯 | Chen 辰 | Si 巳 | Wu 午 | Wei 未 | Shen 申 | You 酉 | Xu 戌 |

| Earth 土 | Hai 亥 | Zi 子 | Chou 丑 | Yin 寅 | Mao 卯 | Chen 辰 | Si 巳 | Wu 午 | Wei 未 | Shen 申 | You 酉 | Xu 戌 |

| Metal 金 | Yin 寅 | Mao 卯 | Chen 辰 | Si 巳 | Wu 午 | Wei 未 | Shen 申 | You 酉 | Xu 戌 | Hai 亥 | Zi 子 | Chou 丑 |

| Water 水 | Si 巳 | Wu 午 | Wei 未 | Shen 申 | You 酉 | Xu 戌 | Hai 亥 | Zi 子 | Chou 丑 | Yin 寅 | Mao 卯 | Chen 辰 |

| Seasonal Node | Celestial Palace and Perfected Beings | Duties in the Celestial Realm |

|---|---|---|

| Beginning of Spring | Palace of Grand Pole at North Pole (Beiji taiji gong 北極太極宮) and Perfected of the Grand Pole (Taiji zhenren 太極眞人) | Carving jade registers and recording the names of immortals |

| Spring Equinox | Jade Terrace in Kunlun (Kunlun yaotai 崑崙瑶臺) and Perfected of Great Simplicity (Taisu zhenren, 太素眞人) | Reviewing and correcting Daoist scriptures |

| Beginning of Summer | Purple Tenuity Palace (Ziwei gong 紫微宮) and Five Thearchs of the Highest Clarity (Shangqing wudi 上清五帝) | Evaluating the merits and faults of Daoist adepts |

| Summer Solstice | Celestial Bureau, Three Officials (Sanguan, 三官), Director of Fates (Siming 司命), and River Lords (Hehou, 河侯) | Judging the sins and blessings of all beings, adjusting lifespan and destiny registers |

| Beginning of Autumn | Yellow Chamber in Mt. Cloud Garden (Huangfang yunting shan 黄房雲庭山), Central Yellow Venerable Lord (Huanglao jun, 黄老君), and the Perfected Lords of the Five Sacred Peaks (Wuyue zhenren 五嶽諸眞人) | Determining the divine charts and spirit medicines of the human realm |

| Autumn Equinox | Numinous Gate (Palace) of Jade Clarity (Yuqing lingque 玉淸靈闕), Watchtower of Great Tenuity (taiweiguan太微觀), Great Thearch of Supreme Sovereign (Shanghuang dadi 上皇大帝), Perfect Sovereign of Nine Heavens (Jiutian zhenhuang 九天眞皇), Three Elder Lords of Most High (Taishang sanlao jun 太上三老君), The Perfected and Dukes of the North Pole (Beiji zhen gong 北極諸眞公), Great Gods of Eight Oceans (Bahai dashen, 八海大神), Revered Spirits of the Five Peaks (Wuyue zunling, 五嶽尊靈) | Deliberating the fate and blessings of all beings and evaluating the diligence of Daoist practitioners |

| Beginning of Winter | The Perfected of the Sun Terrace (Yangtai zhenren 陽臺眞人), The Perfected of Clarity and Void (Qingxu zhenren 淸虛眞人) | Deciding those newly attaining the Dao and entering the registers of immortals |

| Winter Solstice | The Grand Palace of East Florescence in Fangzhu (Fangzhu donghua dagong, 方諸東華大宮) and The Lord of Azure Youth of the Eastern Sea (Donghai qingtong jun, 東海靑童君) | Carving and confirming the registers of all immortals, inscribing celestial names in golden script |

| Ten-Days Cycle | Day | Hour | Direction | Northern Dipper | Inner Organ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ten-days starting with Jiazi 甲子之旬 | Dingmao 丁卯之日 | midnight 夜半之時 | North | The first taixing 第一太星 | heart 心 |

| Ten-days starting with Jiaxu 甲戌之旬 | Dingchou 丁丑之日 | midnight | North | The second yuan xing 第二元星 | lung 肺 |

| Ten-days starting with Jiashen 甲申之旬 | dinghai 丁亥之日 | midnight | North | The third zhenxing 第三眞星 | liver 肝 |

| Ten-days starting with Jiawu 甲午之旬 | dingyou 丁酉之日 | midnight | North | The fourth niuxing 第四紐星 | spleen 脾 |

| Ten-days starting with Jiachen 甲辰之旬 | dingwei 丁未之日 | midnight | North | The fifth gangxing 第五綱星 | stomach 胃 |

| Ten-days starting with Jiayin 甲寅之旬 | dingsi 丁巳之日 | midnight | North | The sixth jixing 第六紀星 | kidneys 腎 |

| The last day of lunar month 月晦之夕 | The first day of lunar month 月朔 | Before dawn 未雖鳴之前 | East | The seventh guanxing 第七關星 | pupils of eyes 目瞳・兩眼 |

| Six Jia days | midnight | Free | The eighth dixing 第八帝星 The ninth taixing 九尊太星 | brain 泥丸紫房 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, J. Elaborating Correlation with Space–Time in the Daoist Body: Following and Reversing Nature. Religions 2025, 16, 890. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16070890

Kim J. Elaborating Correlation with Space–Time in the Daoist Body: Following and Reversing Nature. Religions. 2025; 16(7):890. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16070890

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Jihyun. 2025. "Elaborating Correlation with Space–Time in the Daoist Body: Following and Reversing Nature" Religions 16, no. 7: 890. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16070890

APA StyleKim, J. (2025). Elaborating Correlation with Space–Time in the Daoist Body: Following and Reversing Nature. Religions, 16(7), 890. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16070890