A Study of the Initial System of the Yongle Nanzang 永乐南藏 Based on Phonological Correlations and Their Relationship with the Qishazang 磧砂藏

Abstract

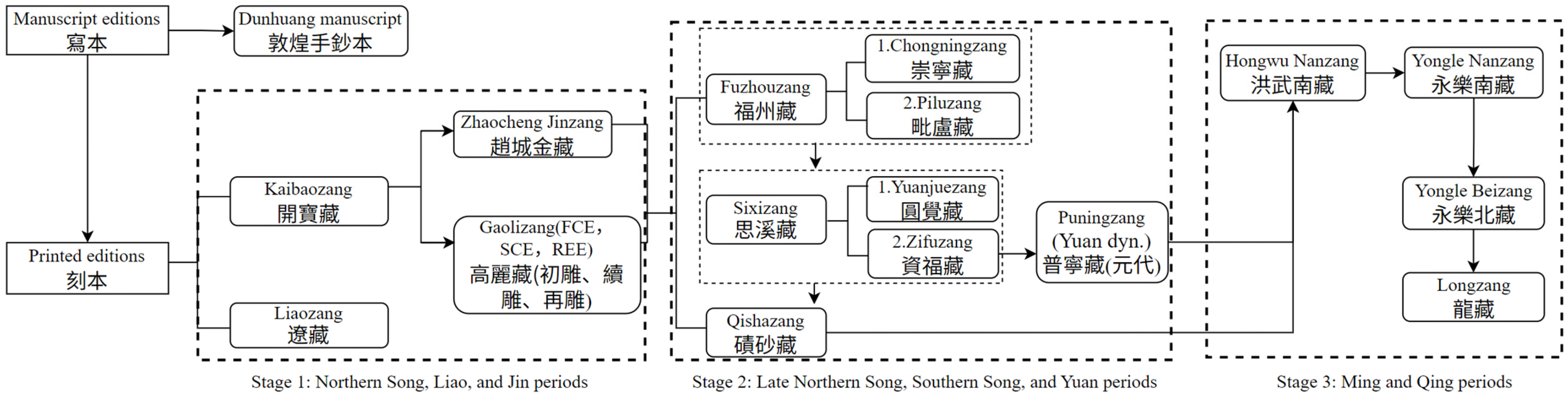

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Materials and the Construction of the Yongle Nanzang Phonological Corpus

2.2. Quantifying Initial Relationships in the Yongle Nanzang’s Suihan Yinyi

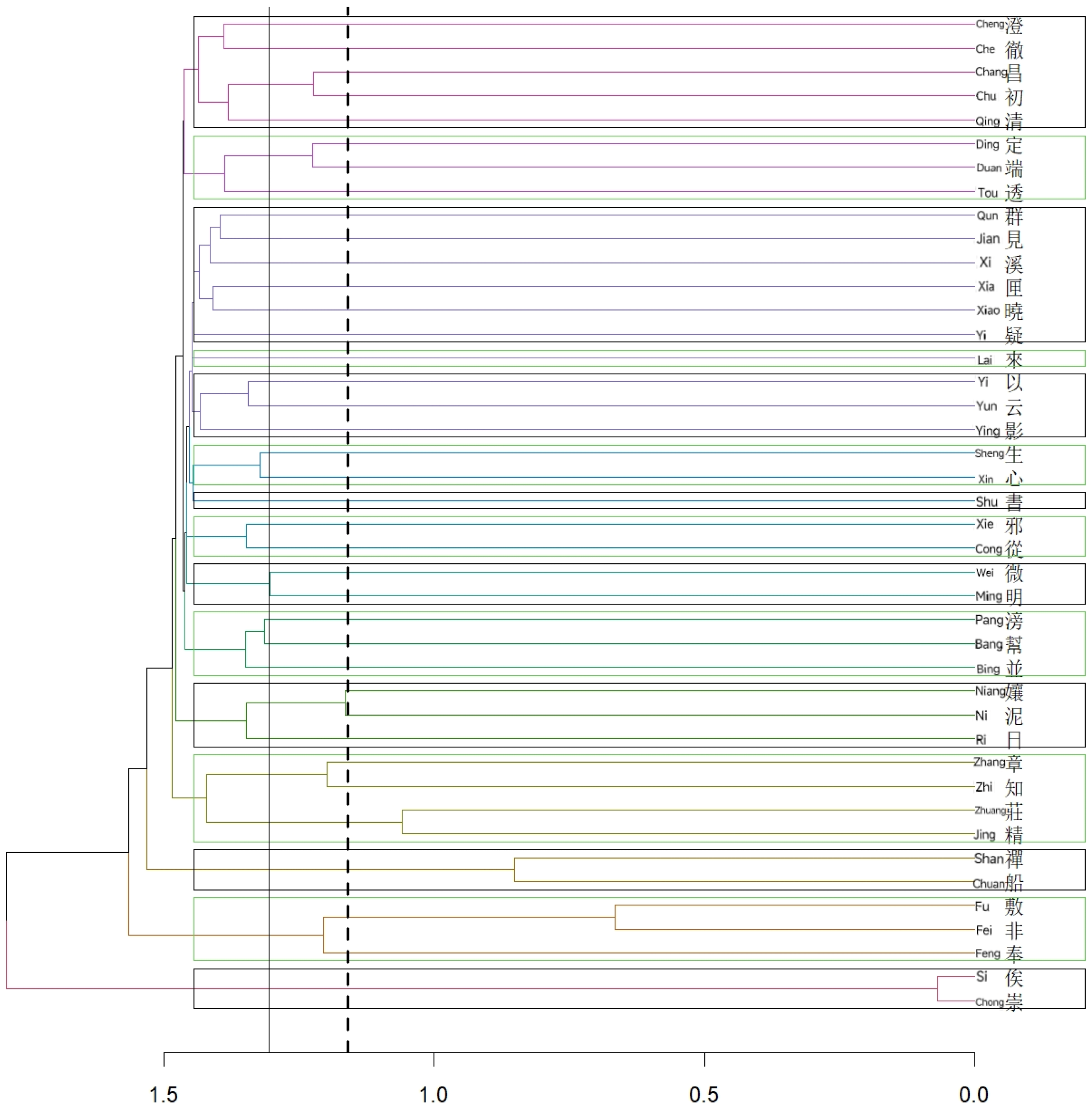

2.3. Hierarchical Clustering of Initial Consonants in the Yongle Nanzang’s Suihan Yinyi

3. Results

3.1. Results and Analysis of Correlation Coefficients

3.2. Results and Analysis of Hierarchical Clustering

4. Discussion

4.1. Affinity Characteristics of the Phonological System in the Yongle Nanzang

4.2. Examining the Relationship Between the Yongle Nanzang and the Qishazang

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | To ensure terminological consistency and stylistic clarity, Chinese characters are provided only at the first occurrence of each technical term; this principle is applied throughout the entire text. |

| 2 | The term Zhongyuan Yayin (中原雅音) in this context does not refer to the now-lost rhyme book of the same name. Understanding its relationship to the Zhongyuan Yinyun (《中原音韻》) requires attention to the preface of the Hongwu Zhengyun (《洪武正韻序》), historical records, and scholarly interpretations. According to Song Lian’s preface, the compilation “faithfully followed the imperial decree, engaged in careful deliberation, and adopted Zhongyuan Yayin as the standard. …Upon submission, it was granted the title Hongwu Zhengyun, and My Majesty ordered me to compose its preface.” Wu Chen wrote that “Zhongyuan speech represents the true and correct sounds of Heaven and Earth.” The Mingshi (《明史》) notes that, in the eighth year of the Hongwu reign, the emperor, finding southern rhymes inadequate, instructed the court to consult Zhongyuan Yayin in correcting them, resulting in the completed Hongwu Zhengyun. Similarly, the Veritable Records of Emperor Taizu (《太祖實錄》) records the following: “This month, the Hongwu Zhengyun was completed… [the emperor] commanded Yue Shaofeng and Hanlin officials to revise it according to Zhongyuan Yayin. It was then named Hongwu Zhengyun and published.” These sources confirm that the Hongwu Zhengyun was compiled based on Zhongyuan Yayin. However, the precise phonological identity of Zhongyuan Yayin remains debated. At least six major interpretations exist: (1) the pronunciation familiar to Zhu Yuanzhang (Ning 2003, pp. 3–4); (2) a system modeled on the Zhongyuan Yinyun (Qian 1999, p. 142); (3) a hybrid of northern and southern phonological features (Zhang 1936, p. 224); (4) a reflection of Southern Mandarin (Guanhua) (Dong 2001, p. 75); (5) a system based on early Nanjing dialect (Karlgren 1940, p. 426; Ning 1985, p. 352); and (6) a representation of early Ming supraregional reading pronunciation (Li 1986, p. 74). |

| 3 | Ning Jifu notes that the Yongle Dadian was compiled according to the Hongwu Zhengyun’s rhyme categories and structure: “Each entry is arranged in sequence according to the rhyme category, sub-rhyme, and rhyme character of the Eighty Rhymes system. Explanations and fanqie spellings for the rhyme characters are recorded accordingly.” He also discusses the broader influence of the Zhengyun in contexts such as the Joseon dynasty of Korea and the Qing dynasty. See (Ning 2003, pp. 14–15). |

References

- Chia, Lucille. 2015. The Life and Afterlife of the Qisha Canon (Qishazang 磧砂藏). In Spreading Buddha’s Word in East Asia: The Formation and Transformation of the Chinese Buddhist Canon. New York: Columbia University Press, pp. 181–218. [Google Scholar]

- Chikusa, Masaaki 竺沙雅章. 2000. Sō Gen ban Daizōkyō no keifu 宋元版大藏經の系譜 [A Genealogy of the Song–Yuan Editions of the Buddhist Canon]. In Studies in the Cultural History of Song–Yuan Buddhism 宋元佛教文化史研究. Tokyo: Kyūko Shoin, pp. 271–362. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, Feng 丁鋒. 2021. Fuzhouzang Wuzhong Jingben Suihan Yinyi Suozhu Zhiyin Fanying de Beisong Yunyin Yanbian Xianxiang 《福州藏》五種經本隨函音義所注直音反映的北宋音韻演變現象 [Phonological Evolution of the Northern Song Dynasty Reflected in Direct Sound Annotations in Five Suihan Yinyi Editions of the Fuzhou Canon]. Research for Folklore, Classics and and Chinses Characters, 171–188+266. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Jianjiao 董建交. 2004. Hongwu Zhengyun Yinxi Yanjiu 洪武正韻音系研究 [Research on the Phonological System of Hongwu Zhengyun]. Ph.D. dissertation, Fudan University, Shanghai, China. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Tonghe 董同龢. 2001. Hanyu Yinyunxue 漢語音韻學 [Chinese Historical Phonology]. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, Guangchang 方廣錩. 2006. Zhongguo Xieben Dazangjing Yanjiu 中國寫本大藏經研究 [Research on Chinese Manuscript Versions of the Buddhist Canon]. Shanghai: Shanghai Century Publishing Co. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Longkui 高龍奎. 2007. Hongwu Zhengyun de Yanjiu Huigu ji Qianzhan 《洪武正韻》的研究回顧及前瞻 [A Review and Prospect of Research on Hongwu Zhengyun]. Journal of Linyi University, 62–65. [Google Scholar]

- He, Guanyin 何觀蔭. 1961. Guanyu Gao Benhan de Qieyun Gouni Xueshuo 關於高本漢的《切韻》構擬學說 [On Bernhard Karlgren’s Reconstruction Theory of the Qieyun]. Journal of Peking University (Philosophy and Social Sciences), 35–46. [Google Scholar]

- He, Mei 何梅. 2005. Ming Yongle Nanzang Yanjiu 明《永樂南藏》研究 [A Study on the Ming Yongle Nanzang]. Chinese Classics & Culture Essays Collection, 52–73. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Yongchao 姜永超, and Renxuan Huang 黄仁瑄. 2024. Cong Qinshudu Lun Guchao Ben Yupian Shengmu Xitong Tezheng Ji Fenhe Guanxi 从亲疏度论古钞本《玉篇》声母系统特征及分合关系 [The Systematical Characteristics and Relationship of the Initial Consonants of Codex Yupian by Proximities]. Yuyan Kexue 2: 184–98. [Google Scholar]

- Karlgren, Bernhard 高本漢. 1940. Zhongguo Yinyunxue Yanjiu 中國音韻學研究 [Studies on Chinese Phonology]. Chinese Translation. Shanghai: Commercial Press. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Fuhua 李富華, and Mei He 何梅. 2003. Hanwen Fojiao Dazangjing Yanjiu 漢文佛教大藏經研究 [Research on the Chinese Buddhist Canon]. Beijing: Zongjiao Wenhua Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Guangkuan 李廣寬, and Yan Lu 陸燕. 2021. Cong Qishazang Suihan Yinyi Kan Tang Song Shiqi Zhi Zhuang Zhang San Zu Shengmu de Yanbian Lujing 從《磧砂藏》隨函音義看唐宋時期知莊章三組聲母的演變路徑 [A Study on Evolutionary Path of Zhi-Zhuang-Zhang Initials in Tang-Song Dynasties from Qishazang’s Suihan Yinyi Perspective]. Studies in Language and Linguistics 41: 54–60. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Xinkui 李新魁. 1986. Hanyu Yinyunxue 漢語音韻學 [Chinese Phonology]. Beijing: Beijing Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Zhouyuan 李周淵. 2021. Qishazang Yanjiu Bainian Zongshu 《磧砂藏》研究百年綜述 [A Century of Research on the Qishazang]. Buddhist Studies 1: 93–123. [Google Scholar]

- Long, Darui. 2015. Managing the Dharma Treasure: Collation, Carving, Printing, and Distribution of the Canon in Late Imperial China. In Spreading Buddha’s Word in East Asia: The Formation and Transformation of the Chinese Buddhist Canon. New York: Columbia University Press, pp. 219–45. [Google Scholar]

- Long, Darui 龍達瑞. 2022. Yongle Beizang de Tiji, Paiji Yanjiu 《永樂北藏》的題記、牌記研究 [The Yongle Northern Canon: Its Colophons and Inscriptions]. Fo Guang Journal of Buddhist Studies 8: 81–144. [Google Scholar]

- Lü, Cheng 呂澂. 2014. Nanzang Chu Ke Kao 南藏初刻考 [An Examination of the First Printing of the Nanzang]. In Collected Works of Ouyang Jingwu, Volume 1 歐陽竟無著述集(上). Beijing: People’s Oriental Publishing & Media Co., Ltd. First published 1938. [Google Scholar]

- Miyazaki, Tenshō 宮崎展昌. 2019. Daizōkyō no rekisho: Naritachi to denshō 大蔵経の歴史ー成り立ちと伝承 [The History of the East Asian Buddhist Canon: On Its Development and Transmission]. Kyoto: Hōjōdō shuppan Okutaabu (Octave) 方丈堂出版オクターブ. [Google Scholar]

- Ning, Jifu 寧繼福. 1985. Zhongyuan Yinyun Biaogao 中原音韻表稿 [Draft Tables of the Zhongyuan Yinyun]. Changchun: Jilin Literature and History Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ning, Jifu 寧忌浮. 2003. Study of the Hongwu Zhengyun《洪武正韻研究》. Shanghai: Shanghai Lexicographical Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Pulleyblank, Edwin G. 1984. Middle Chinese: A Study in Historical Phonology. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, Xuantong 錢玄同. 1999. Qian Xuantong Wenji 錢玄同文集 [Collected Works of Qian Xuantong]. Beijing: Renmin University of China Press, vol. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, Rui 邵睿. 2012. Yingyin Songban Qishazang Suihan Yinyi Shenglei Yanjiu 影印宋版《磧砂藏》隨函音義聲類研究 [A Study on the Phonological Categories of the Facsimile Song Edition of the Qishazang]. Master’s thesis, Nanjing Normal University, Nanjing, China. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, Cui 譚翠. 2015. Qishazang Suihan Yinyi Suojian Song-Yuan Yuyin 《磧砂藏》隨函音義所見宋元語音 [Song-Yuan Period Phonological Features Reflected in the Qishazang Suihan Yinyi]. Research in Ancient Chinese Language, 70–74. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Baohong 王寶紅. 2001. Hongwu Zhengyun Yanjiu 《洪武正韻》研究 [Research on the Hongwu Zhengyun]. Ph.D. dissertation, Shanxi Normal University, Xi’an, China. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Jiang. 2015. The Chinese Buddhist Canon Through the Ages: Essential Categories and Critical Issues in the Study of a Textual Tradition. In Spreading Buddha’s Word in East Asia: The Formation and Transformation of the Chinese Buddhist Canon. New York: Columbia University Press, pp. 15–45. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Shiyi 徐時儀. 2006. Jinzang, Lizang, Qishazang Yu Yongle Nanzang Yuanyuan Kao: Yi Xuanying Yinyi Wei Li 金藏、麗藏、磧砂藏與永樂南藏淵源考——以《玄應音義》為例 [A Study on the Origins of the Jin Zang, Li Zang, Qishazang, and Yongle Nanzang—Taking the Xuanying Yinyi as an Example]. Studies in World Religions, 18–31. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Chang 楊嫦. 2014. Hongwu Zhengyun yu Guangyun Yinxi de Bijiao Yanjiu 《洪武正韻》與《廣韻》音系的比較研究 [A Comparative Study of the Phonological Systems of Hongwu Zhengyun and Guangyun]. Master’s thesis, Hunan Normal University, Changsha, China. [Google Scholar]

- Zacchetti, Stefano. 2015. Notions and Visions of the Canon in Early Chinese Buddhism. In Spreading Buddha’s Word in East Asia: The Formation and Transformation of the Chinese Buddhist Canon. New York: Columbia University Press, pp. 81–108. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Shilu 張世祿. 1936. Zhongguo Yinyunxue Shi 中國音韻學史 [A History of Chinese Historical Phonology]. Shanghai: Commercial Press, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

| ID | Target Character | First Fanqie Character | Second Fanqie Character | Zhiyin | Sutra Title |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11111211_33-000032 | Jiu 糺 | Ji 吉 | You 酉 | Da Bore Boluomiduo Jing 大般若波羅蜜多經 (600 volumes) (001) | |

| 11111211_33-000032 | Qi 賾 | Qi 七 | e 萼 | Da Bore Boluomiduo Jing (600 volumes) (001) | |

| 11111211_33-000032 | Chen 齓 | Chu 初 | Juan 䚈 | Da Bore Boluomiduo Jing (600 volumes) (001) | |

| 11111211_33-000032 | Zu 足 | Zi 子 | Yu 遇 | Da Bore Boluomiduo Jing (600 volumes) (001) | |

| 11111211_33-000032 | Luan 孿 | Ban 闆 | Yuan 員 | Da Bore Boluomiduo Jing (600 volumes) (001) | |

| 11111211_33-000032 | Pi 嫓 | Pi 匹 | Yi 詣 | Da Bore Boluomiduo Jing (600 volumes) (001) |

| Fanqie | Initial | Initial Type | Voicing | Rhyme | Rhyme Group | She | Hu | Deng | Tone |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jiu 糾 Ji 吉/You 酉 | Jian 見 Jian 見/Yi 以 | 牙 牙/喉 | 全清 全清/次濁 | You 黝 Zhi 質/You 有 | You 幽 Zhi 質/You 尤 | Liu 流 Zhen 臻/Liu 流 | Kai 開 Kai 開/Kai 開 | SanA三A SanC三C/SanA三A | Shang 上 Ru 入/Shang 上 |

| Ze 賾 Shi 士/Ge 革 | Chong 崇 Chong 崇/Jian 見 | 正齒 正齒/牙 | 全濁 全濁/全清 | Mai 麥 Zhi 止/Mai 麥 | Mai 麥 Zhi 之/Mai 麥 | Geng 梗 Zhi 止/Geng 梗 | Kai 開 Kai 開/Kai 開 | er 二 SanA三A/er 二 | Ru 入 Shang 上/Ru 入 |

| Chen 齔 Chu 初 /Juan 䚈 | Chu 初 Chu 初 /Jian 見 | 正齒 正齒/牙 | 次清 次清/全清 | Chen 櫬 Yu 魚/Xian 線 | Zhen 臻 Yu 魚/Xian 仙 | Zhen 臻 Yu 遇/Shan 山 | Kai 開 He 合/He 合 | SanD三D SanA三A/SanC三C | Qu 去 Ping 平 /Qu 去 |

| Zu 足 Zi 子/Yu 遇 | Jing 精 Jing 精 /Yi 疑 | 齒頭 齒頭/牙 | 全清 全清/次濁 | Yu 遇 Zhi 止/Yu 遇 | Yu 虞 Zhi 之/Yu 虞 | Yu 遇 Zhi 止/Yu 遇 | He 合 Kai 开/He 合 | SanA三A SanA三A/SanA三A | Qu 去 Shang 上 /Qu 去 |

| The Initial of the First Fanqie Character | The Initial of the Target Character | The Initial of the Target Character | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bang 幫 | Pang 滂 | Bing 並 | Ming 明 | Bang 幫 | Pang 滂 | Bing 並 | Ming 明 | |

| Bang 幫 | 782 | 27 | 42 | 1.000 | 0.071 | 0.049 | −0.027 | |

| Pang 滂 | 13 | 334 | 16 | 1.000 | 0.044 | −0.030 | ||

| Bing 並 | 20 | 17 | 852 | 1.000 | −0.028 | |||

| Ming 明 | 604 | 1.000 | ||||||

| Notes | Co-occurrence | Correlation Coefficients | ||||||

| Bang 幫 | Pang 滂 | Bing 並 | Ming 明 | Fei 非 | Fu 敷 | Feng 奉 | Wei 微 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bang 幫 | 1.000 | 0.071 | 0.049 | −0.027 | −0.005 | −0.035 | −0.019 | −0.028 |

| Pang 滂 | 1.000 | 0.044 | −0.030 | −0.030 | −0.004 | −0.031 | −0.031 | |

| Bing 並 | 1.000 | −0.028 | −0.025 | −0.034 | 0.003 | −0.027 | ||

| Ming 明 | 1.000 | −0.029 | −0.038 | −0.031 | 0.078 | |||

| Fei 非 | 1.000 | 0.534 | 0.214 | −0.021 | ||||

| Fu 敷 | 1.000 | 0.156 | −0.026 | |||||

| Feng 奉 | 1.000 | −0.002 | ||||||

| Wei 微 | 1.000 |

| Duan 端 | Tou 透 | Ding 定 | Ni 泥 | Zhi 知 | Che 徹 | Cheng 澄 | Niang 孃 | Ri 日 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duan 端 | 1.000 | −0.001 | 0.135 | −0.034 | 0.013 | −0.023 | 0.001 | −0.032 | −0.031 |

| Tou 透 | 1.000 | 0.046 | −0.033 | −0.024 | −0.028 | −0.026 | −0.030 | −0.025 | |

| Ding 定 | 1.000 | −0.032 | −0.026 | −0.026 | −0.008 | −0.029 | −0.025 | ||

| Ni 泥 | 1.000 | −0.037 | −0.035 | −0.031 | 0.181 | −0.023 | |||

| Zhi 知 | 1.000 | 0.014 | −0.001 | −0.032 | −0.030 | ||||

| Che 徹 | 1.000 | 0.021 | −0.029 | −0.026 | |||||

| Cheng 澄 | 1.000 | −0.030 | −0.027 | ||||||

| Niang 孃 | 1.000 | −0.028 | |||||||

| Ri 日 | 1.000 |

| Jing 精 | Qing 清 | Cong 從 | Xin 心 | Xie 邪 | Zhuang 莊 | Chu 初 | Chong 崇 | Sheng 生 | Si 俟 | Zhang 章 | Chang 昌 | Chuan 船 | Shu 書 | Shan 禪 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jing 精 | 1.000 | −0.004 | 0.044 | −0.021 | −0.027 | 0.261 | −0.027 | −0.027 | −0.026 | −0.024 | −0.022 | −0.028 | −0.036 | −0.026 | −0.033 |

| Qing 清 | 1.000 | −0.013 | −0.010 | −0.028 | −0.025 | 0.049 | −0.027 | −0.018 | −0.024 | −0.028 | 0.009 | −0.021 | −0.028 | −0.033 | |

| Cong 從 | 1.000 | −0.027 | 0.050 | −0.008 | −0.034 | 0.026 | −0.030 | −0.027 | −0.031 | −0.029 | −0.038 | −0.029 | −0.034 | ||

| Xin 心 | 1.000 | −0.011 | −0.036 | −0.033 | −0.029 | 0.065 | −0.026 | −0.024 | −0.026 | −0.036 | −0.024 | −0.032 | |||

| Xie 邪 | 1.000 | −0.038 | −0.034 | −0.022 | −0.029 | −0.021 | −0.030 | −0.028 | −0.036 | −0.028 | −0.031 | ||||

| Zhuang 莊 | 1.000 | −0.027 | −0.009 | −0.033 | −0.007 | 0.117 | −0.037 | −0.050 | −0.037 | −0.043 | |||||

| Chu 初 | 1.000 | 0.008 | −0.017 | −0.026 | −0.032 | 0.137 | −0.038 | −0.027 | −0.025 | ||||||

| Chong 崇 | 1.000 | −0.030 | 0.998 | −0.021 | −0.029 | −0.030 | −0.029 | −0.012 | |||||||

| Sheng 生 | 1.000 | −0.027 | −0.030 | −0.029 | −0.037 | −0.016 | −0.034 | ||||||||

| Si 俟 | 1.000 | −0.028 | −0.026 | −0.034 | −0.026 | −0.028 | |||||||||

| Zhang 章 | 1.000 | −0.019 | −0.034 | −0.013 | −0.014 | ||||||||||

| Chang 昌 | 1.000 | −0.031 | −0.020 | 0.002 | |||||||||||

| Chuan 船 | 1.000 | −0.018 | 0.408 | ||||||||||||

| Shu 書 | 1.000 | −0.020 | |||||||||||||

| Shan 禪 | 1.000 |

| Jian 見 | Xi 溪 | Qun 羣 | Yi 疑 | Ying 影 | Xiao 曉 | Xia 匣 | Yun 云 | Yi 以 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jian 見 | 1.000 | 0.009 | 0.013 | −0.019 | −0.020 | −0.008 | 0.009 | −0.028 | −0.025 |

| Xi 溪 | 1.000 | −0.009 | −0.021 | −0.021 | −0.017 | −0.020 | −0.029 | −0.029 | |

| Qun 羣 | 1.000 | −0.018 | −0.026 | −0.025 | −0.022 | −0.029 | −0.027 | ||

| Yi 疑 | 1.000 | −0.021 | −0.024 | −0.021 | −0.020 | −0.027 | |||

| Ying 影 | 1.000 | −0.013 | −0.016 | −0.002 | −0.023 | ||||

| Xiao 曉 | 1.000 | 0.004 | −0.027 | −0.025 | |||||

| Xia 匣 | 1.000 | −0.009 | −0.005 | ||||||

| Yun 云 | 1.000 | 0.051 | |||||||

| Yi 以 | 1.000 |

| Place of Articulation | Yongle Nanzang Initial System | Qishazang Initial System |

|---|---|---|

| Labials | Bang 幫, Pang 滂, Bing 並, Ming 明 | Bang 幫, Pang 滂 (Bing 並), Ming 明 |

| Fei 非 (Fu 敷), (Feng 奉), Wei 微 | Fei 非, Fu 敷 (Feng 奉), Wei 微 | |

| Tongues/ Coronals | Duan 端, Tou 透, Ding 定, Ni 泥 | Duan 端, Tou 透 (Ding 定), Ni 泥 (Niang 孃) |

| Zhi 知, Che 徹, Cheng 澄, Niang 孃, Lai 來 | Zhi 知, Che 徹 (Cheng 澄), Lai 來 | |

| Teethes/ Dentals | Jing 精 (Zhuang 莊), Qing 清, Cong 從, Xin 心, Xie 邪 | Jing 精, Qing 清 (Cong 從), Xin 心 (Xie 邪) |

| Chu 初, Chong 崇 (Si 俟), Sheng 生 | Zhuang 莊, Chu 初, Chong 崇, Sheng 生/(Zhang 章, Chang 昌, Chuan 船, Shu 書, Chan 禪, Ri 日) (Si 俟) | |

| Zhang 章, Chang 昌, Chuan 船, Shan 禪, Shu 書, Ri 日 | ||

| Velars | Jian 見, Xi 溪, Qun 羣, Yi 疑 | Jian 見, Xi 溪 (Qun 羣), Yi 疑 |

| Gutturals | Ying 影, Xiao 曉, Xia 匣, Yun 云, Yi 以 | Ying 影, Xiao 曉 (Xia 匣), Yu 喻 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jiang, Y.; Wang, B.; Huang, R. A Study of the Initial System of the Yongle Nanzang 永乐南藏 Based on Phonological Correlations and Their Relationship with the Qishazang 磧砂藏. Religions 2025, 16, 838. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16070838

Jiang Y, Wang B, Huang R. A Study of the Initial System of the Yongle Nanzang 永乐南藏 Based on Phonological Correlations and Their Relationship with the Qishazang 磧砂藏. Religions. 2025; 16(7):838. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16070838

Chicago/Turabian StyleJiang, Yongchao, Boxuan Wang, and Renxuan Huang. 2025. "A Study of the Initial System of the Yongle Nanzang 永乐南藏 Based on Phonological Correlations and Their Relationship with the Qishazang 磧砂藏" Religions 16, no. 7: 838. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16070838

APA StyleJiang, Y., Wang, B., & Huang, R. (2025). A Study of the Initial System of the Yongle Nanzang 永乐南藏 Based on Phonological Correlations and Their Relationship with the Qishazang 磧砂藏. Religions, 16(7), 838. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16070838