Abstract

Seoul systematically removed all graveyards that once lay within the city and its surrounding areas, a phenomenon notably distinct from urban development patterns in other parts of the world. After the Korean War, refugees and migrants poured into the devastated capital. In this postwar environment, cemeteries—traditionally sites of mourning and death—transformed into spaces of survival for displaced populations. With the military demarcation line preventing their return home, refugees began to envision their lost hometowns as “absent places”: unattainable utopias, idealized lands where all beauty resides—the very origin and endpoint of life. In contrast, Seoul, where they were forced to settle, became a “dystopia,” stripped of sanctity. Over time, however, the next generation reinterpreted this dystopia, gradually transforming it into a heterotopia. As Seoul’s urban landscape expanded, this heterotopia evolved into a Christian paradise. The second generation, having never experienced the trauma of displacement, found the newly constructed city comfortable and secure. Reinforced concrete buildings and asphalt roads became symbolic of paradise. The development of Gangnam—famously captured in Psy’s global hit “Gangnam Style”—represents a belated cultural revolution among younger generations in modern South Korea and exemplifies the transformation into a concrete paradise.

Keywords:

Seoul; graveyards; cemeteries; distance; refugees; migrants; descendants; utopia; dystopia; heterotopia; concrete paradise; Gangnam style 1. Introduction

This essay examines the religious epistemology of life and death among Seoul’s residents through an analysis of the spatial relationship between the city and its cemeteries. A substantial portion of this discussion is grounded in my own lived experience. As a lifelong Seoulite, I have resided in various neighborhoods, gradually moving from the city center to its peripheries. Thus, parts of this study function not only as an academic inquiry but also as an oral history from a native resident.

I was born in Euljiro, the heart of Seoul, and later moved to Mia-ri, one of its outlying districts. My experiences in Mia-ri were deeply formative. Encounters with tombs and even the body of an infant, intergenerational tensions with my refugee parents, and the evolving idea of a “concrete paradise” shape this narrative, which spans the years from 1968 to 2024.

Traditionally in Korea, the sense of “home” was closely tied to being with one’s parents and ancestors. Graveyards were typically located near villages and formed a natural part of the landscape. These were not modern public cemeteries, but family burial grounds that were intimately connected to everyday life.

In contrast, modern cemeteries—administratively regulated and spatially segregated—were introduced under Japanese colonial rule and felt unfamiliar to most Koreans. According to H. A. Lee (2014, p. 403), “In Korea, the Japanese colonial government published the Rules on Gravesite, Crematorium, Burial and Cremation (hereafter the ‘burial rules’) in 1912, marking the first modern institutional regulation of burial practices.” Japan, in its quest for imperial status, deliberately adopted modern Western values, knowledge, and technologies. At the same time, it internalized a sense of cultural superiority over fellow Asians, practicing what Kikuchi (2004) terms “oriental Orientalism.”

In Korea, the burial policy was implemented in 1912, two years after the onset of Japanese colonial rule. While grave regulation was officially justified on the grounds of sanitation and public health, it also served broader colonial goals. As Takamura (2000) argues, the Japanese found scattered gravesites to be a serious hindrance to land use planning and infrastructure development. Diplomatic correspondence between Korean and Japanese authorities reveals that unregulated burial sites were viewed as obstacles to Japan’s colonization strategy.

The Japanese constructed an extensive railway network and established military bases to support campaigns such as the First Sino-Japanese War (1894) and the Russo-Japanese War (1904). During this period, Japanese colonial authorities frequently clashed with the Korean government over the regulation and removal of gravesites (H. A. Lee 2014, p. 407). In 1900, for instance, the Japanese were compelled to revise their original plan to build a railway station near Namdaemun (South Gate) after the Korean government requested the preservation of existing graves (Chuhanilponkongsakwankirok 주한일본공사관기록 Records of Japanese legation Korea 1900, Database of Korean History). Despite such negotiations, the Japanese continued to forcibly remove graves. The compensation offered to Korean landowners was inadequate, leading to widespread protests and remonstrations (Chuhanilponkongsakwankirok 주한일본공사관기록 Records of Japanese legation Korea 1905, Database of Korean History). Beginning with the Residency-General period (1905–1910), the Japanese intensified efforts to control land in Korea, viewing unregulated gravesites as impediments to colonial development (Nahm 2009; Shin 1977).

Japan’s modernization efforts, initiated under the Meiji Restoration, were implemented rapidly and with strong state oversight. These efforts were soon extended to its colonies, including Korea. As Lee (p. 406) notes, the administrative technologies used in Japan’s colonies resembled those of Western imperial powers, though they were often less institutionally mature. Among these, burial policy played a significant role. Once cemeteries were removed from everyday spaces, Koreans gradually grew accustomed to the spatial separation between the living and the dead. Following the Korean War, this spatial severance became even more pronounced. All cemeteries within the city limits of Seoul were eliminated, a historically unprecedented phenomenon that radically transformed the urban landscape and the cultural relationship between life and death.

As refugees and migrants flooded into a war-torn Seoul, the city came to embody a dystopia for those who had lost their homes. In contrast, their former hometowns—now inaccessible due to the armistice and national division—were imagined as unreachable utopias: idealized places that no longer existed in reality but remained alive in memory.

In the immediate postwar years, Seoul was overwhelmed by housing shortages, and cemeteries—lacking ancestral ties—became objects of aversion rather than reverence. Traditionally, most Koreans had been part of agrarian communities, deeply attached to their land and ancestors. Generations lived and died without ever leaving their native soil, reinforcing a spatial continuity between life, land, and lineage. The refugee experience disrupted this relationship, displacing individuals from both home and sacred burial spaces.

As the influx of refugees stabilized, a new generation emerged—one born and raised in Seoul. Unlike their parents, they did not experience the trauma of displacement or the emotional pull of a lost hometown. For them, Seoul was not a temporary refuge, but their permanent home. Although they inherited their parents’ memories of exile, their lived reality was vastly different. Surrounded by concrete high-rises and paved roads, they found comfort and stability in the modern city. In their eyes, the once-dystopian urban landscape had transformed into a “concrete paradise.” (See Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flight of refugees across wrecked bridge in Korea1. Source: National Archives of Korea.

Waldo Tobler’s first law of geography, also known as the distance decay effect, states that “everything is related to everything else, but near things are more related than distant things” (Tobler [1970] 2023, pp. 234–40). This principle highlights the centrality of spatial proximity in shaping human experience and perception.

Building on this spatial logic, Michel Foucault distinguishes between three types of space: undifferentiated space, utopia (ideal but nonexistent spaces), and heterotopia (real but alternative spaces). Heterotopias are “other spaces” that simultaneously reflect and invert the norms of ordinary life, such as hidden lofts where children construct their own unique worlds of time and meaning (Foucault [1967] 1986, pp. 22–27).

During the 1960s and 1970s, Seoul underwent rapid and large-scale urbanization. As waves of migrants continued to arrive, the city expanded both geographically and socially, fundamentally altering its spatial structure. For the first generation—composed largely of refugees and rural migrants—the experience of exile solidified over time into a permanent condition.

In contrast, the second generation was born and raised within this newly urbanized landscape. Unlike their parents, who yearned for a lost homeland, they knew no other place but Seoul. Surrounded by concrete high-rises and sprawling infrastructure, they developed their own sense of place and identity. For them, the city was not a dystopia, but rather a “concrete paradise”—a heterotopia where stability and modernity coexisted.

This generational divide, however, gave rise to tensions. The differing emotional attachments to space—nostalgia for a vanished past versus adaptation to a modern present—reflected broader divergences in values, memories, and worldviews.

The rapid disappearance of cemeteries from Seoul’s urban landscape—and their relocation to increasingly distant outskirts—signals more than just physical neglect. It reflects a deeper emotional and cultural alienation: a collective disconnection from the processes of mourning, remembrance, and even death itself. This spatial separation between the living and the dead illustrates a broader societal struggle to meaningfully engage with both life and mortality.

Yet burial practices have not remained static. In response to this distancing, new forms of commemoration have emerged—such as columbaria, private memorial parks, and religious facilities—offering alternative modes of engaging with death (Kee 2017, pp. 128–30).

2. The Holy Graveyards vs. the Hates of the Cemeteries

Confucian tradition placed great emphasis on gwanhonsangje (冠婚喪祭), the four major rites of passage: coming of age, marriage, funerals, and ancestral rituals. These ceremonies gave concrete form to abstract notions of time, space, and sanctity, shaping the temporal and moral contours of human life. Paradoxically, however, while Confucianism ritualized nearly every aspect of daily life, it also maintained a distinct spatial and emotional separation from death. This paradox deepened in modern urban Seoul, where the cultural and physical divide between the living and the dead exceeded even that of the highly ordered Joseon Dynasty.2

Confucianism, the state ideology of the Joseon Dynasty, emphasized a strict spatial demarcation between the realms of life and death. From early on, Confucian practices dictated that graves and burial activities be situated outside the bounds of daily life, particularly beyond the urban center.

This principle is clearly articulated in classical Chinese texts such as the Zhouli (周禮, Rites of Zhou) and Kaogongji (考工記, Records of Craftsmen), especially in sections concerning city planning. According to the Zhouli, grave sites were prohibited along the city’s north–south axis, which symbolized political and ritual authority. Only ancestral shrines—such as Jongmyo (宗廟) and Sajik (社稷)—were permitted along the east–west axis, where cosmological balance was maintained.

This tradition held sway across various Chinese dynasties and in Joseon. Early Joseon thinkers such as Jeong Do-jeon and later scholars like Jeong Yak-yong upheld these principles. Under these guidelines, graves were effectively banned from areas near royal palaces. Even the suburban ring (郊, gyo), which extended up to 10 li beyond the city walls (城底十里, seongjeosipni), was considered under royal influence and therefore deemed unsuitable for graves (Dakamura 2000, pp. 132–33).

The term bukmangsan (北邙山), meaning “northern burial mountain,” originated in Luoyang (洛陽), China, where it referred to a prominent burial site located north of the city. In Korea, the term was adopted to describe communal graveyards located on hills near villages, distinguishing them from seonsan (先山)—private ancestral mountains reserved for family burials.

During the Joseon period, after funeral rites were completed, members of the aristocracy (yangban) typically transported their ancestors’ remains to seonsan sites in the countryside. In contrast, commoners often buried their dead on hills just outside the city walls. In Seoul, these included areas beyond gates such as Gwanghuimun and Seosomun, which gradually became densely populated with graves. These collective burial sites came to be colloquially known as bukmangsan (Dakamura 2000, pp. 135–37), and were regarded by Koreans as sacred places imbued with ancestral meaning.

By contrast, the modern public cemetery, introduced by the Japanese colonial administration, was based on the Western notion of sanitary, regulated burial zones deliberately placed at a distance from residential areas (Home 1997). These state-managed cemeteries were not rooted in traditional spatial relationships or cultural practices. Unsurprisingly, many Koreans viewed the system as alien and even offensive, strongly opposing what they perceived as a forced and de-spiritualized treatment of the dead (Dakamura 2000, pp. 156–58).

Goto Shimpei, a prominent Japanese colonial official, described the colonial police as “the hands and feet of the governor-general, in direct contact with the people” (Tsurumi 1943, II: 151). This statement underscores the extent to which colonial authority relied on police power to enforce its policies, including the regulation of death.

Under the 1912 burial rules, the disposal and regulation of the dead fell explicitly within the jurisdiction of the police. Articles 23 and 24 of the regulation stipulated punishments for non-compliance, most of which were carried out not by judicial courts, but directly by the police. The colonial police wielded summary powers, including corporal punishment, under the Summary Judgment Ordinance (1910) and the Joseon Flogging Ordinance (1912).

As a result, traditional Korean burial practices—which had not been considered illegal prior to colonization—were suddenly subject to criminalization. This abrupt imposition of new norms generated deep resentment among Koreans, a sentiment that would later surface during the March 1st Independence Movement in 1919 (H. A. Lee 2014).

During the early years of Japanese colonial rule, public cemeteries in Seoul were established in areas that are now central and well-known neighborhoods, such as Itaewon, Mia, Yongsan, Hannam-dong, Ahyeon, Sinchon, Hongje, Sindang, and Gaepo-dong (in present-day Gangnam). At the time, these sites were located on the periphery of the city, consistent with the colonial policy of distancing burial grounds from residential life.

However, as Seoul rapidly urbanized throughout the 20th century, these once-outlying districts became part of the city’s core. In response, cemeteries were progressively relocated to more remote locations, including Mangwoo-ri, Yongmi-ri, and Gwangju in Gyeonggi Province. Today, even these suburban burial grounds have been erased from their original urban fabric, symbolizing an ever-growing distance between everyday life and the spaces of death.

Geographer Waldo Tobler’s first law of geography—that “everything is related to everything else, but near things are more related than distant things” (Tobler [1970] 2023, pp. 234–40)—applies directly to the evolving spatial relationship between urban life and death in Seoul. In traditional Korean society, graves were often located on nearby hills or ancestral mountains, reinforcing an intimate connection between the living and the dead. However, as public cemeteries were increasingly relocated to remote outskirts, death became physically and psychologically severed from everyday urban life. This spatial dislocation produced a double exclusion: death was not only removed from the city but also from the collective consciousness of its residents.

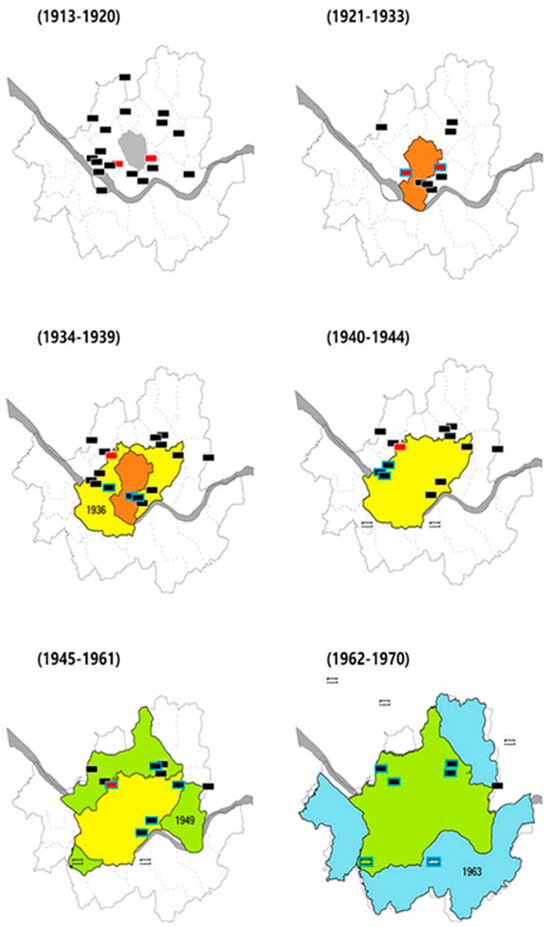

This phenomenon echoes philosopher George Berkeley’s famous dictum: “to be is to be perceived.” As cemeteries moved farther from urban centers, they also faded from cultural awareness. The distance is not trivial—walking from central Seoul to Mangwoo-ri or Byeokje (Yongmi-ri) takes roughly five hours, and to Gwangju Cemetery nearly fifteen. Although public cemeteries were initially introduced under Japanese colonial rule, the practice of pushing them ever farther away continued even after liberation. Rather than restoring proximity to ancestral land, postcolonial urban planning reinforced this separation. (See Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Expansion of Seoul and changing of public cemetery sites (E. Lee 2021, p. 111).

This stands in marked contrast to many European cities, such as Paris, where cemeteries like Montmartre and the Catacombs remain integrated into the urban fabric. Seoul’s cemetery policy, by contrast, reflects a mindset rooted in exile and displacement. For refugees and migrants, the city was never a true home, and death—like life—remained provisional and displaced (Kee 2017, pp. 57–63, 83–84; Jeong 2016).

For displaced communities, the ancestral mountains of their lost hometowns came to symbolize an unattainable utopia—a place of origin that existed only in memory. In contrast, their lived reality in Seoul, far removed from these roots, felt relentlessly bleak and alienating. Cemeteries in areas such as Mangwoo-ri, Yongmi-ri, or Gwangju were not perceived as sacred extensions of familial lineage, but as temporary waystations for displaced souls.

Lacking a connection to ancestral land, these burial grounds failed to evoke reverence. Instead, they were often viewed with discomfort or even aversion. Over time, this emotional detachment contributed to a broader dystopian ethos within refugee and migrant communities, one in which both life and death were stripped of stability, continuity, and meaning. As this sentiment deepened, cemeteries—and the very cultural imagination of death—gradually faded from public consciousness.

3. Ceasefire of the Korean War and Life in Dystopia

For many refugees, daily life after the Korean War was marked by persistent pain and despair. In contrast, their hometowns—where their parents had once lived—were imagined as paradisiacal spaces, lost to time and history. Reality itself took on dystopian qualities, while the embrace of their parents, accessible only through death, came to represent a form of utopia.

The popular modern term “Hell Joseon”3 may have its psychological roots in this postwar refugee experience. By the mid-1950s, large waves of displaced persons arrived in Seoul, soon followed by economic migrants. Amidst unfamiliar urban surroundings and acute housing shortages, songs expressing longing for lost hometowns became deeply resonant, offering emotional refuge in an alienating environment. This cultural expression reflected both a physical and emotional chasm: the hometown, idealized yet unreachable, versus Seoul, which embodied disruption, displacement, and social estrangement. Blocked by the 38th parallel from returning and haunted by painful memories, many refugees began to imagine their hometowns as “absent places”—utopias of beauty and belonging, where life was thought to have begun and where, ultimately, it should end.

These hometowns thus emerged as sacred spaces, firmly rooted in memory, yet rendered unreachable by the “Reds,” perceived as a malevolent enemy. Such memories elevated the hometown to a spiritual ideal—an imagined utopia. Conversely, Seoul—the city where refugees were forced to resettle—became a dystopia, stripped of sanctity and emotional resonance.

After the war, the “spaces of death” underwent profound transformation. For many refugees, sanctity was inseparable from tangible experiences of time and place—elements that were disrupted in the unfamiliar cemeteries of Seoul. Unlike the burial sites in their hometowns, these cemeteries lacked continuity with ancestral tradition and were perceived as alien, impersonal spaces. This spatial and emotional disjunction severed their connection to the sacred. When space is fragmented and stripped of memory, sanctity loses its physical grounding and survives only as an abstract idea. Refugees, armed with nothing more than faded photographs and fragmented memories, had no embodied sense of “home” to return to—even imaginatively.

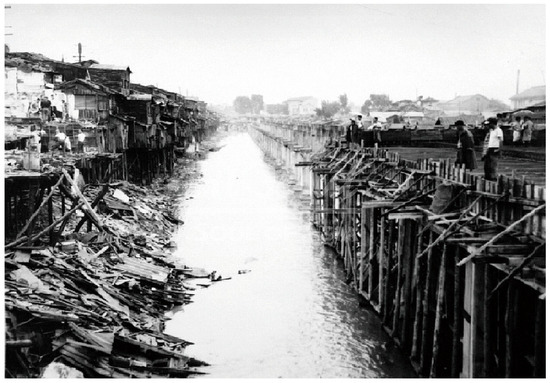

Unlike religious pilgrims, who could physically traverse landscapes imbued with meaning, refugees could engage with the sacred only through dreams or longing.4 As a result, their experience of sanctity remained incomplete, suspended in emotional and spatial exile (Kee 2017, pp. 72–76). (See Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Clapboard housing on Cheonggyecheon in 19655. Source: Seoul Museum of History.

The pervasive ethos of loss experienced by refugees became one of the most potent social forces in postwar Korea. This collective trauma did not remain confined to private memory: instead, it permeated public life, shaping both political ideologies and personal aspirations. In many cases, it gave rise to a form of utopian longing—a desire to recover or recreate what had been irrevocably lost. Within this framework, Seoul emerged not as a site of renewal, but as a dystopian space, devoid of the sacred connections, ancestral ties, and symbolic continuity that had once defined the notion of “home.” For many refugees, the capital resembled a state of limbo or even a kind of secular hell, suspended between displacement and belonging.

Refugees and migrants often remarked that contemporary Seoulites appeared “stingy” or inhospitable. These sentiments reflect mutual suspicion and social fragmentation in a rapidly expanding urban environment. Longtime residents viewed newcomers—refugees and rural migrants—with discomfort, while the displaced perceived urban society as cold and exclusionary. A popular saying of the time reflected this tension: “They’re so clever they could steal your nose while you’re still awake,” a phrase used to describe the cunning competitiveness required to survive in Seoul. This atmosphere of mutual distrust, born out of resource scarcity and spatial crowding, contributed to a cityscape shaped by social anxiety and alienation—hallmarks of an emerging urban dystopia.

But are Seoulites inherently defined by such traits? Demographic data suggest otherwise. According to the Seoul Metropolitan Government, the city’s population grew from approximately 1.5 million in the early 1950s to over 10 million by 1990. The greater metropolitan area also expanded dramatically—from around 4 million to more than 23 million today—driven largely by an influx of refugees and internal migrants.

I was born in Euljiro, then a refugee settlement area where most residents were from North Korea. Later, when my family moved to Mia-ri, I encountered people from southern provinces—migrants from rural South Korea. This personal trajectory mirrors a broader demographic reality: over 80% of Seoul’s population today consists of individuals who are not originally from the city. If one considers that the city’s population during the Joseon Dynasty was about 300,000, then up to 97% of present-day residents may be seen as relative newcomers (Son and Nam 2006, p. 23).

In this context, the so-called Seoulite is less a static identity than a product of relentless competition among migrants and refugees, each pursuing their own imagined utopia. Ironically, it is this very collision of competing dreams that has gradually shaped Seoul into the dystopia many experience today.

4. Tears in Mia-ri, the Heterotopia for Second Generations

During my childhood, I lived in Mia-ri, a district in northern Seoul that was known at the time as a shantytown. I vividly remember crossing Mia-ri Hill in the back of a moving truck, passing rows of shamanic and fortune-telling houses decorated with colorful flags. Yet what left the deepest impression were the meticulously arranged tombstones, sculpted by local stonemasons—silent reminders that this area had once served as a cemetery.

Mia-ri was a space where multiple realities coexisted: the sacred and the profane, the dead and the living, the marginal and the everyday. It exemplified a particular urban formation in northern Seoul—a chaotic, but enduring coexistence of memory, displacement, and survival.

As children, we built secret hideouts in the nearby hills, creeks, and abandoned houses that surrounded Mia-ri. The hills were scattered with graves: some marked by small tombstones, others by barely visible mounds. We often encountered skulls and bones, using them unthinkingly as props in our games of war and adventure. The creeks were heavily polluted, emitting a pungent odor. One day, a black plastic bag floating in the water drew our attention. When we opened it, we found the body of a deceased infant.

Just beyond the creek and adjacent to the public cemetery stood Mia-ri Texas, a red-light district. Even as children, we wandered through its streets, occasionally receiving candy from women dressed in traditional hanbok. The irony was not lost on us: a place of death had become a site of commercial sex, and the sacred had become intermingled with the profane.

Mia-ri’s public cemetery was established in 1912 under Japanese colonial rule following the promulgation of the Cemetery Regulations, which designated the area the official burial ground for Gyeongseong (the Japanese name for Seoul). During the colonial period, Mia-ri Cemetery marked a symbolic boundary between the living and the dead (E. Lee 2021, pp. 96–99). (See Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Mia-ri Public Cemetery in 19586. Source: Seoul Museum of History.

Later, Mia-ri Hill came to represent wartime suffering, serving as both an advance and retreat route for North Korean forces during the Korean War. The anguish of those abducted to the North was memorialized in the popular song “Heartbreaking Mia-ri Hill”,7 further cementing the district’s tragic reputation.

Starting in 1955, infrastructure development inside Seoul’s traditional city gates led to a series of “relocation settlement areas” being established in Mia-ri for residents displaced by urban redevelopment and flood damage. This influx of refugees and other displaced groups gave rise to dal-dongne (shantytowns) that spread across the surrounding hillsides. Through government-led settlement projects, Mia-ri was gradually transformed from a cemetery into a residential district.

By the early 1960s, major infrastructural changes—including the construction of bridges and roads and the concreting over of local creeks—led to the entombment of streams like Jeongneungcheon and Wolgokcheon beneath massive slabs of concrete. As public cemeteries vanished and residential development expanded, Mia-ri Texas—an adjacent red-light district—began to grow.

By the mid-1980s, following the 1985 opening of the Seoul subway system and a wave of Japanese tourists arriving for the 1988 Seoul Olympics, Mia-ri’s public image underwent a dramatic transformation: from a cemetery zone to one of Seoul’s most prominent brothel districts (Kim 2011, pp. 91–93).

Michel Foucault distinguished three categories of space: undifferentiated space, utopia (ideal but imaginary spaces), and heterotopia (real, physical spaces that exist outside normative social orders). Heterotopias, he argues, are “other spaces” that simultaneously reflect, invert, or disrupt the dominant logic of society. Common examples include cemeteries, which spatially isolate death from everyday life, and brothels, which function as “cunning heterotopias” that destabilize moral and spatial conventions (Foucault [1967] 1986; Lee and Wei 2020, p. 6).

In this light, Mia-ri can be seen as a paradigmatic heterotopia, a space where contrasting and often conflicting realities coexisted. As a site that housed both a colonial-era cemetery and later a red-light district, Mia-ri embodied what Foucault calls “evident” and “cunning” heterotopias. It was a zone where death and desire, memory and marginality, public policy and intimate life all converged in uneasy proximity.

For me personally, Mia-ri was also a childhood heterotopia. The hills, graves, polluted streams, and sex work establishments were not just fragments of a fractured city: they were the everyday backdrops of play, exploration, and unspoken cultural memory. Especially during the 1970s and 1980s, Mia-ri functioned as a layered and overlapping heterotopia: one that revealed how urban development, displacement, and sacred–profane entanglements shaped a generation’s formative spatial experience.

5. Christian Paradise

The 1960s and 1970s marked a pivotal era in Seoul’s urban development and territorial expansion. As the city rapidly grew, it attracted an ever-increasing population, driven in part by large-scale infrastructure projects, including the Gyeongbu Expressway, elevated highways, the covering of the Cheonggyecheon stream, the construction of Sewoon Sangga, and the rise of high-density apartment complexes.

Seoul’s population surged from approximately 3.7 million in 1966 to over 8.3 million by 1980. A similar trend unfolded across the surrounding metropolitan region. The city’s physical footprint expanded as well—from 135 km2 in 1936 to 713 km2 by 1963, peaking at 720 km2 in 1970—surpassing even its current land area (Son and Nam 2006, pp. 31–37).

Although many refugees initially experienced Seoul as a dystopia, they actively sought to construct an alternative vision of paradise within the city. This spiritual endeavor found material form in the rapid expansion of Protestant Christianity during South Korea’s period of industrialization and urban growth.

In 1966, Protestants accounted for approximately 900,000 people, or 3% of the national population. By 1970, that figure had surged to 3.2 million (10.2%), and by 1980, it had reached 5.34 million (14.3%) (nationwide) (Lim 2019, pp. 135–40). In a city marked by displacement, insecurity, and rootlessness, Protestant churches functioned as surrogate homelands—promising believers a “New Heaven and New Earth,” or a “New Jerusalem,” superimposed upon the alien urban landscape.

A striking facet of South Korean Protestantism during this period was the emergence of mega-churches, and Seoul was no exception. Of the world’s fifty largest congregations, twenty-three are in South Korea, with fifteen located in Seoul alone. Two prominent illustrations of these new utopian movements are Youngnak Presbyterian Church and Yoido Full Gospel Church.

The divergence between these two institutions reflects deeper social and spatial distinctions between refugees and internal migrants. Youngnak Presbyterian Church, located in central Seoul (Chungmuro), functioned as a spiritual anchor for North Korean refugees. Known for its conservative Presbyterian theology, the church embodied a vision of order, resilience, and preservation. I was born near this church and witnessed its centrality in the lives of many displaced families.

In contrast, Yoido Full Gospel Church initially emerged on the urban periphery (Eunpyeong-gu) and later moved to Yeouido, reflecting the trajectory of rural migrants seeking new identities. Associated with dynamic worship, charismatic leadership, and a theology of healing and material blessing, the church offered a vibrant, forward-looking alternative anchored in hope, prosperity, and urban adaptation (S. Lee 2017).

Founded in 1958 in Eunpyeong-gu—then a suburban area on the outskirts of Seoul—Yoido Full Gospel Church experienced extraordinary growth over the next four decades. Membership expanded from 800 in 1962 to 18,000 by 1973, 503,000 in 1986, and over 700,000 by 1997. This unprecedented expansion reflected the church’s strong appeal to Seoul’s urban poor, migrants, and aspiring middle classes.

Under the leadership of Pastor Cho Yong-gi, the church promoted a theology that blended spiritual salvation, physical healing, and material blessing, a form of prosperity gospel that resonated with individuals seeking hope and security in an uncertain urban environment. The church offered a vision of paradise made real in the here and now: not a distant heaven, but one embedded in concrete, economic recovery, and personal empowerment.

According to current Pastor Lee Young-hoon, six key factors contributed to the church’s explosive growth: positive and uplifting messages, powerful healing ministries, mountain prayer gatherings, charismatic gifts, such as glossolalia (speaking in tongues), home-based cell groups, and strategic use of mass media.

Doctrinally, this vision was undergirded by the church’s Fivefold Gospel—salvation, the fullness of the Holy Spirit, divine healing, blessing, and Christ’s second coming—and its Triple Blessing doctrine, which emphasized spiritual, material, and physical prosperity.8 Together, these offered not only theological coherence but also a practical roadmap for surviving—and thriving—in the rapidly modernizing city.

Protestantism also addressed a deeply pragmatic issue for refugees and migrants: the matter of ancestral rites. Within Protestant theology, ancestral rituals were often denounced as idolatrous practices incompatible with Christian faith (Soo 2015, pp. 112–25). For many urban newcomers—who lacked physical access to ancestral graves—this doctrinal stance offered unexpected psychological relief.

Protestant churches not only discouraged these rites but also provided institutional alternatives, such as funeral services and cemetery support. In doing so, they lifted the emotional and ritual burden traditionally associated with filial piety. Without the need to maintain ties to ancestral burial sites, congregants became more accepting of the growing physical distance between everyday life and the realm of the dead.

At the same time, sermons often depicted heaven as a distant, spiritual realm, mirroring the very remoteness of modern cemeteries. As a result, Protestant eschatology gradually replaced earlier forms of utopian longing rooted in lost hometowns. Ironically, however, this new heaven was even more distant than the physical places refugees had once left behind.

Graves symbolize not only the physical remains of ancestors but also the weight of the past. For many migrants and refugees—whose personal histories were marked by displacement and trauma—the past was a painful reminder they often wished to bury, both literally and figuratively. Although Protestant theology emphasized the forgiveness of sins and offered a sense of spiritual renewal, it had clear limitations. The emphasis on personal salvation did not always engage meaningfully with the complexities of ancestral obligation, unresolved historical memory, or the search for self-understanding in a dislocated urban context. In this sense, while Protestantism succeeded in constructing a new urban utopia for many, it also left certain cultural and existential questions unanswered: questions related to lineage, belonging, and the reconciliation of one’s past with a fragmented present.

While Protestantism provided one model of urban utopia, Buddhism also adapted to the modern secular landscape by developing alternative practices for honoring the dead. Traditionally centered in remote mountain monasteries, South Korean Buddhist temples began moving closer to urban populations in an effort to remain culturally relevant and accessible (Kee 2017, pp. 88–92). Rather than emphasizing burial and ancestral graves, Buddhist institutions offered ritual substitutes—such as the Myeongbu-jeon (ancestral tablet halls), Suryukjae (water and land rites), Saengjeonyesujae (rites for the living), and 49-day mourning rituals—that were compatible with cremation and adaptable to urban settings. These ceremonies shifted the focus from the physical grave to ritual memory and symbolic continuity. Korean Buddhism, predominantly Zen in orientation, has historically placed less emphasis on grave-centered practices. While cremation was once uncommon in traditional Korean society, this began to change after the implementation of the Family Ritual Standards Act in 1999. The act encouraged cremation and restricted burial to limited conditions (such as individuals over the age of 70). Since then, cremation has become the dominant form of funeral practice in South Korea.

Nonetheless, Buddhism’s overall influence has remained regionally concentrated. According to Gallup Korea surveys conducted between 1984 and 2021, the Buddhist population has consistently ranged between 17% and 24% of the national total, most prominently in the Yeongnam region, which was less affected by wartime displacement and refugee movement.9 Gallup pointed out that Buddhism is strong in the Yeongnam area of South Korea and has a long history. It is said that the ethos of Buddhism is not like Protestantism in Seoul. During the Korean War, Yeongnam was not occupied by the North Korean forces, so the people did not have to seek refuge elsewhere. At that time, many had to flee to Busan, the southernmost part of the Yeongnam area. In this sense, the population and composition of South Korean Buddhists are not like those of Protestantism.

As industrialization drew more people to Seoul, the Protestant church infused spiritual vitality into an ever-expanding metropolis. By offering its “threefold salvation,” it effectively transformed Seoul into a perceived material “paradise.”

6. Concrete Paradise

The dystopia described thus far was not merely the absence of hope, but the shadow of a utopia envisioned by displaced refugees and migrants. Over time, however, a second generation emerged—children born into the city of Seoul built from concrete and steel. Lacking direct experience of loss or exile, they developed their own spatial sensibilities and constructed new forms of heterotopia within the urban fabric. While the first generation consisted of North Korean refugees and rural migrants who viewed Seoul as a place of trauma and impermanence, the second generation regarded the city as home. For them, there was no “lost origin” to long for—only the present, made stable by infrastructure, apartment blocks, and asphalt roads. Their values, shaped by physical security rather than memory, diverged markedly from those of their parents.

Nowhere is this contrast clearer than in their relationship to cemeteries. Unlike their parents, who mourned the removal of ancestral graves, the second generation began to literally and figuratively pave over death: covering old graveyards with concrete and integrating them into the city’s ever-expanding surface.

For Seoul-born individuals of the second generation, the ideological construct of a “hometown”—so central to their parents’ worldview—held little tangible meaning. Unlike their elders, they had neither fled a homeland nor mourned its loss, and thus bore no burden of guilt or nostalgia.

Nevertheless, they often inherited a subtle narrative from their parents: that Seoul was not their true home, but a hostile dystopia, unworthy of genuine attachment. A proper hometown, they were told, lay far away, in rural regions accessible often only after a day-long drive, filled with wooded hills, mosquito-laden paths, and ancestral burial grounds (seonsan). These stories conjured an idealized, almost mythological past where electricity was absent and suffering was framed as “the taste of home.” Since Seoul did not satisfy these conditions, it was dismissed as an asphalt dystopia—a place devoid of natural landscapes or ancestral graves.

But for the second generation, such portrayals were abstract at best. The Seoul they knew—flattened under asphalt and ordered by gridlines—offered a different sense of belonging. Ironically, it was during national holidays, when older generations left the city to visit ancestral homes, that younger Seoulites found their paradise: empty roads, quiet neighborhoods, and the uncanny serenity of an unclaimed metropolis. They thus began to separate the conceptual “utopia” of their parents from the concrete heterotopia in which they actually lived. For the second generation, these deserted streets symbolized their true sense of home. They neither idealized their parents’ rural hometowns nor yearned for them: instead, the concrete expanse beneath their feet became their paradise.

The cemeteries, too, were eventually covered with asphalt and concrete. What once served as sacred ground—spaces of mourning, memory, and ancestral continuity—was repurposed for roads, schools, housing developments, or simply paved over into urban anonymity. This act was not merely functional. It symbolized a profound cultural shift: death was no longer a visible or integral part of urban life. Instead, it was hidden beneath infrastructure, rendered invisible and inaccessible to everyday consciousness. As reinforced concrete replaced ritual topography, the city severed its spatial and emotional ties to the dead.

In this context, the so-called concrete paradise was not just a metaphor: it became a literal environment in which the past was entombed beneath modern surfaces. For the second generation, death was no longer something to be seen or touched, but something to be walked over, unnoticed. (See Figure 5).

Figure 5.

See (Kim and Choi 2019). Source: Concrete Seoul Map. Blue Crow Media Architecture Maps—Folded Map.

7. Time and Space and Individualization of Death

7.1. Personal Sensibility Time

As Mircea Eliade observed, religious experience is deeply rooted in conceptions of time and space. Immanuel Kant similarly described time and space as the “pure forms of sensibility”—the fundamental conditions through which humans perceive the world (Stephenson and Gomes 2024, pp. 64–83). Within this framework, sanctity itself can be understood as arising from the structured interplay between spatial and temporal order.

In modern Seoul, however, this sacred structure has been disrupted. A distinctive feature of Korean temporal culture is its dual-calendar system: the coexistence of the solar (Gregorian) and lunar calendars. Individuals frequently shift between the two, selecting whichever is more convenient for a given context—a pragmatic “cheat code” that reflects both flexibility and fragmentation in temporal consciousness.

Because time and space are structurally parallel, changing one’s calendar system effectively reshapes the spatial and symbolic order of daily life. Mircea Eliade emphasized how cyclical festivals sustain “the myth of the eternal return,” a sacred rhythm that reaffirms communal identity across time and space (Eliade and Trask 1971). Throughout history, new regimes have established their own calendars to assert political and cosmological authority, demonstrating the deep interlinkage between temporal control and spatial sovereignty.

In modern Seoul, however, this unity has fractured. The widespread coexistence of the solar and lunar calendars has disrupted the shared experience of sacred time. Individuals selectively shift between them based on convenience, weakening the communal rhythms once anchored by holidays such as Chuseok and Seollal. Protestant churches in particular have adopted the solar calendar to avoid association with ancestral rites and other culturally embedded lunar practices. As a result, time in the modern city is increasingly privatized, fragmented, and stripped of its collective sanctity.

For the first generation, the lunar calendar remained the primary temporal framework for life events. Although Japan imposed the solar calendar during the colonial period, it failed to erase lunar influences, and even authoritarian leaders like Park Chung-hee could not eradicate it completely. The lunar calendar thus served as the temporal axis of the first generation’s utopian imagination, shaping holidays, ancestral rites, birthdays, and personal anniversaries. By contrast, official institutions and broader society operated on the solar calendar. This hybridization weakened the collective force of sanctity, leading to disparities in how time and space were perceived.10

7.2. Emotional Geography of Seoul

If one were to map Seoul according to the colors of personal memory, the city might appear as a mosaic of emotional topographies: early childhood spaces rendered in green, romantic memories in pink, workplaces and nightlife in blue, and sites of solitude or reflection in brown. These colors, distributed across neighborhoods and time periods, would form fragmented, yet meaningful islands of experience: an “emotional geography” where each individual navigates their own private heterotopias, imbued with personal sanctity (Song 2011).

For the second generation, this emotional geography diverged significantly from that of their parents. While the first generation’s worldview was shaped by grass and trees—that is, by natural landscapes and cyclical time—the second generation came of age amid concrete and asphalt, forged under the Saemaul Undong (New Village Movement, 1971 onward) and authoritarian modernization projects.

Virtually everything—from roads and apartment blocks to the Han River embankments and even heritage landmarks such as Gyeongbokgung and Bulguksa—was reconstructed in reinforced concrete. The Stone Pagoda at Mireuksa, a once-sacred relic, now stands as an exemplar of “rebuilt heritage” (Kim and Choi 2019). In such a world, sanctity was no longer inherited through nature or tradition, but reconstructed, resurfaced, and repurposed in concrete.

Unlike their parents, who reminisced about pastoral landscapes and ancestral villages, the second generation found comfort in concrete. Their sense of time also diverged, aligning primarily with the solar calendar rather than the lunar rhythms that had shaped earlier generations.

As a result, their urban heterotopias provided a sense of stability and belonging. No longer haunted by memories of a lost homeland, they experienced little tension between reality and utopian longing. For them, paradise was no longer imagined elsewhere: it existed directly underfoot, embedded in the concrete and asphalt of the city.

Michel Foucault notes that in pre-18th-century towns, cemeteries were central, usually adjacent to churches. Human remains were grouped collectively, reflecting a communal view of death. Ironically, as modern society became more secular or even atheistic, remains began to be individualized: people were buried in personal plots, situated ever farther from population centers. Foucault refers to this as the “individualization of death,” likening it to the isolation of disease. He regards cemeteries as heterotopias par excellence in modernity (Foucault [1967] 1986, pp. 22–27).

This concrete-based reality of the second generation fully embodies what Michel Foucault described as the individualization of death. As urban life became defined by infrastructure, efficiency, and standardization, burial practices adapted accordingly. Traditional funerals—once elaborate, time-intensive, and tied to ancestral land—were replaced by streamlined three-day ceremonies held in standardized funeral halls. Government policies, such as the Family Ritual Standards Act, promoted cremation over burial, further encouraging the removal of death from residential and familial spaces. Unlike the first generation, who wished to die at home and be buried in ancestral soil, the second generation experienced death as a managed process: from hospital mortuary to commercial funeral home to remote crematorium. Everything—attire, flowers, ashes, and resting place—became prepackaged, professionalized, and spatially outsourced.

In this way, death was no longer a communal rupture, but a logistical event. The cemetery, once a sacred landscape of memory and kinship, became a neutral facility on the urban periphery—evidence of a modern sensibility that prefers to contain, control, and ultimately distance itself from the sacred.

8. Gangnam Style Cemetery

Psy’s global hit “Gangnam Style” marked more than a viral pop phenomenon: it signaled a new generational aesthetic, a third-generation sensibility born in concrete, but draped in color, spectacle, and self-styling. Unlike the second generation, which found stability in gray infrastructure, this new cohort embraced visual exuberance and symbolic play.

Though still rooted in the concrete cityscapes of their predecessors, the third generation distinguished itself by embellishing the urban surface: vibrant graffiti, bold lighting, and curated streetwear turned the mundane into the theatrical. These “Gangnamites” transformed gray façades into flamboyant canvases—layering joy, irony, and style over structural uniformity.

In this way, even death itself began to appear susceptible to aesthetic reconfiguration. Style became not just a way of life, but a way of remembering, mourning, and ultimately distancing oneself from the gravity of loss.

Gangnam, now synonymous with affluence and urban sophistication, began as a low-lying region of wetlands and rural farmland. Prior to its transformation, it bore little resemblance to the meticulously curated landscape it is today. Between 1968 and 1970, a series of infrastructural megaprojects—including the Gyeongbu Expressway, the Third Hangang Bridge (Hannam Bridge), and Gangnam-daero—catalyzed the area’s rapid development (Kang 2015). These developments laid the groundwork for a new urban frontier: soon apartment complexes, elite schools, and corporate headquarters flooded into the region. Gangnam was deliberately designed not as a natural extension of old Seoul but as a symbolically “new” city—engineered to be modern, orderly, and forward-looking. In this design, there was no room for the past: wetlands were drained, villages disappeared, and cemeteries—if acknowledged at all—were removed, relocated, or erased.

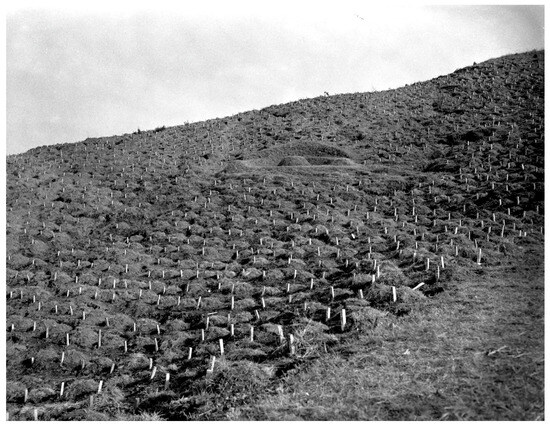

Situated south of the Han River, Gangnam emerged as a city built entirely on farmland, overlaid with concrete and asphalt—a space engineered rather than evolved. Unlike northern Seoul, which retained traces of prewar identity and refugee memory, Gangnam offered a blank slate for a new generation. The area attracted mostly second-generation newcomers who were unburdened by the ideological nostalgia for a “true” homeland, a sentiment that continued to shape the emotional landscape of first-generation refugees in the north (Kang 2015). Owing to this spatial and generational separation, Gangnam residents largely escaped the inherited melancholy of displacement. (See Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Aerial photograph of Gaepo-dong, Gangnam, cemetery in 197211. Source: Public Data Portal.

A Brand-New Type of “Protest of 1968” in Seoul

Unlike Europe—where the May 1968 protests in France ignited a sweeping cultural revolution encompassing education reform, sexual liberation, social equality, and environmental awareness—South Korea followed a different trajectory. As Russian–Korean historian Park No-ja notes, South Korea effectively missed the cultural dimension of 1968. Instead, from the 1960s to the 1980s, the nation underwent a more urgent and dangerous transformation—a political revolution. The democratization movement against military dictatorship defined this period, with many activists risking arrest, torture, or even death in pursuit of political freedom. Only by the late 20th century—after the collapse of authoritarian regimes—did South Korea begin to experience a delayed wave of cultural emancipation, akin to post-1968 Europe. Yet these expressions emerged with a distinctly South Korean flavor: filtered through global pop, digital modernity, and the stylized aesthetics of youth. “Gangnam Style” in this context was not merely a pop song, but a symbolic artifact of South Korea’s belated, but exuberant cultural revolution.12

This belated “1968-style” cultural revolution in South Korea proved to be both expansive and radical in scope. It encompassed newfound freedoms in speech, gender equality, environmental consciousness, secularism, and even animal rights—domains long marginalized under authoritarian rule. In this context, Psy’s “Gangnam Style” can be interpreted as a cultural manifesto for this phenomenon: a playful, yet incisive declaration of South Korea’s vibrant and unrestrained entry into global pop culture. The song’s explosive international success marked not merely a viral moment, but a shift in aesthetic sensibility, where satire, spectacle, and digital fluency converged to announce a new cultural voice. In its wake, K-pop and associated cultural forms surged into global prominence, with the Korean wave (hallyu) emerging as a direct extension of this delayed, but far-reaching social transformation.

Yet even Gangnam—the very embodiment of modernity, affluence, and aesthetic self-styling—was once home to multiple large-scale public cemeteries. The district originally hosted eight such burial grounds, including the Seoul Municipal Anju Cemetery in Banpo-dong (now part of Gangnam-gu), as well as others in areas like Sinsa and Hak-dong. However, as Gangnam underwent rapid urbanization in the 1970s, these cemeteries were either relocated to the outskirts or dismantled altogether to make room for apartment complexes, commercial districts, and public infrastructure (E. Lee 2021, p. 59). In a city predicated on youth, speed, and spectacle, there was little space—literally or symbolically—for death. Gangnam, like the rest of Seoul, joined in the national project of pushing death to the margins, ensuring that memory, mourning, and ancestral presence would remain invisible in the city’s forward-facing surface.

Even in stylish Gangnam, where affluence and aesthetic polish define the urban experience, death remains inescapable. Yet here too, burial practices were systematically pushed to the margins. In northern Seoul, cemeteries were concentrated in areas such as Yongmi-ri, Byeokje-ri, Manguri, and Naegok-ri, with only Manguri still within reach of the city’s edge.

In contrast, southern Seoul, including Gangnam, came to rely on newer infrastructure like Seoul Memorial Park, designed primarily for cremation and enshrinement rather than traditional burial. The near-total absence of cemeteries within Gangnam reflects more than a logistical gap: it reveals a deeper cultural aversion to death and burial, particularly among upwardly mobile migrant populations. For these communities, death was not something to be commemorated in visible, physical form, but something to be efficiently processed, spiritually reinterpreted, and spatially distanced from the living.

The transformation of burial practices in Gangnam reflects broader shifts in modern funerary culture. Revisions to the Family Ritual Standards Act restricted traditional burials to certified cemeteries, while cremation became the default, unless specific conditions—such as the deceased being over the age of 70—were met. As cremation rates surged, new forms of commemorative architecture proliferated: columbaria, landscaped memorial parks, and religious facilities tailored to urban aesthetics.

A prominent example is Seongnam Memorial Park, located near Gangnam. Surrounding areas like Gwangju and Yongin now host a dense network of memorial parks centered on columbarium complexes. Unlike traditional cemeteries, these spaces are carefully curated environments, often featuring individualized tombstones, manicured gardens, and stylized monuments that highlight personal identity and visual distinctiveness. Even the management offices resemble boutique cafés, offering visitors a sense of comfort and tasteful mourning. In this context, Gangnam has extended its signature urban style into the realm of death, recasting mourning as an opportunity for aesthetic self-expression and curated remembrance.

One of the most striking recent trends in funerary culture is the emergence of “companion burials,” the practice of allowing humans and their companion animals to be interred together. What was once unthinkable under traditional norms, where only human family members were permitted in burial grounds, is now being normalized in Gangnam’s evolving deathscape. This shift reflects a deeper cultural transformation: pets are no longer “owned,” but accompanied, redefined not as property, but as emotional kin. The language itself has changed: “pets” have become “companion animals,” a semantic shift that mirrors broader societal changes in human–animal relationships. In this way, Gangnam’s funerary culture epitomizes its late-arriving but transformative cultural revolution, extending aesthetic and emotional individualization even to death itself.13

The burial of companion animals alongside their human owners epitomizes the full realization of the individualization of death. What was once an exclusively human and family-centered practice has now expanded to include non-human loved ones, signaling a profound redefinition of kinship, grief, and remembrance.

Traditional burial norms strictly prohibited the interment of animals in human cemeteries. Burial grounds were culturally reserved for blood relations, reflecting Confucian ideals of lineage and ancestral continuity. The inclusion of animals would once have been unthinkable—considered a violation of ritual purity and social order. Yet in the wake of Gangnam’s cultural shift, this taboo has softened. Companion burials are now increasingly accepted, reflecting a broader trend in which death—like life—is shaped by personal relationships, emotional bonds, and aesthetic choices. The rise of pet funeral industries, complete with memorial parks and stylized urns, further underscores this transformation.

In this context, death has become not just an end, but a final act of identity expression—individualized, aestheticized, and emotionally curated. Gangnam-style death is no longer about ancestry or collective memory: it is about choice, style, and the curation of meaning in a world where even mortality can be made one’s own. (See Figure 7).

Figure 7.

The concrete shrine (Chung 2017) of Seoul—Cheonggye creek14. City of Seoul.

9. Conclusions: Comprehensive Reflections on Cemeteries and Burial Practices

In conclusion, Gangnam, shaped by the so-called Concrete Generation, has overlaid its utilitarian foundations with new aesthetic elements—colors, graffiti, and design—to create a style uniquely emblematic of its identity. Although this cultural revolution arrived later than similar movements elsewhere, it successfully introduced personal and aesthetic expression into the traditionally austere domain of death and cemeteries. Put differently, burial grounds—once confined to the symbolic realm of mourning—have been transformed into heterotopias infused with individuality and visual intentionality.

Seoul’s cemetery culture is particularly distinctive from a global perspective (Kee 2017, pp. 103–8). In the aftermath of the Korean War, cemeteries were systematically eradicated from urban areas, severing spatial and cultural ties to ancestral memory. These sites were relocated to the urban periphery, labeled undesirable, and largely excluded from the logic of modern urban planning.

This disappearance—and the broader public aversion to cemeteries—reflects not only spatial marginalization but also an emotional and symbolic estrangement from death. Seoul, and by extension Gangnam, offered little care or integration for the deceased throughout the 20th century.

However, these separations are not irreversible. The emergence of columbaria, private memorial parks, and religious facilities signals a gradual transformation in attitudes toward death: a move away from avoidance and toward personalized commemoration.

In contemporary Seoul—now living firmly in the era of “Gangnam style”—cemeteries are no longer just spaces of death. They have begun to incorporate stylistic trends such as cremation, pet burials, and curated memorial experiences, reflecting a departure from long-standing conventions.

It is within this transformation that the entrenched divide between life and death—between the domains of the living and the resting—may begin to soften. Through style, Seoulites are not only redefining how they live, but how they die—and ultimately, how they remember.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The author has provided details regarding where data supporting reported results can be found, including links to publicly archived datasets analyzed or generated during the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | This picture belongs to the National Archives of Korea and is publicly accessible at https://theme.archives.go.kr/viewer/common/archWebViewer.do?bsid=200200098092&dsid=000000000029&gubun=search (accessed on 24 May 2025). |

| 2 | The Joseon Dynasty was established upon the ideology of neo-Confucianism. The government banned graveyards from areas near royal palaces. Village inhabitants maintained their ancestor’s graves, which were within walking distance of the village. This was different from public cemeteries, which were further relegated and managed by Japanese government. |

| 3 | “Hell Joseon” (Korean: 헬조선; RR: Heljoseon; MR: Helchosŏn; lit. Hell Korea) is a satirical South Korean term that became popular around 2015. The term is used to criticize the socioeconomic situation in South Korea (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hell_Joseon, accessed on 24 May 2025). |

| 4 | There are many differences between refugees and religious pilgrims. According to Coffey (2020), how to handle religious dissenters and religious refugees was a pressing problem in a Europe divided by faith. Some states pursued a zero-tolerance policy toward dissenters, creating refugees in the process. Medieval Spain had been a multi-faith society comprised of Catholics, Jews, and Muslims, but early modern re-Catholicization forced hundreds of thousands of Jews and Muslims into exile. Many settled in the Islamic world, including the Ottoman Empire, which was more accommodating to Jews and other minorities than most Christian states. For example, prosecuted many religious dissenters as a threat to church and state. Under Elizabeth I, English authorities executed some separatists for sedition, burned half a dozen anti-Trinitarians for heresy, and hanged between 120 and 130 Catholic priests for treason. |

| 5 | This picture belongs to the Seoul Museum of History and is publicly accessible at https://museum.seoul.go.kr/archive/archiveNew/NR_archiveView.do?ctgryId=CTGRY328&type=A&upperNodeId=CTGRY331&fileSn=300&fileId=H-TRNS-77352-331 (accessed on 24 May 2025). |

| 6 | This picture belongs to the Seoul Museum of History and is publicly accessible at https://museum.seoul.go.kr/archive/archiveNew/NR_archiveView.do?ctgryId=CTGRY1024&type=A&upperNodeId=CTGRY1036&fileSn=586&fileId=ecb87161-66ee-4742-967d-b97a8307fc46 (accessed on 24 May 2025). |

| 7 | See https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fj-ynzx2cSw (accessed on 24 May 2025). |

| 8 | See https://yfgc.fgtv.com/y1/0401.asp (accessed on 24 May 2025). |

| 9 | See https://www.gallup.co.kr/gallupdb/reportContent.asp?seqNo=1208 (accessed on 24 May 2025). |

| 10 | Two calendar systems is a kind of “heterochronia” in Michel Foucault’s term. Michel Foucault borrowed the term heterochronie from the biological language in his 1967 Des Espaces Autres to interrogate the modern Western construction of time and its relationship with hegemonic historical narratives. Heterochronia does not refer to time as an abstract dimension of physics, but rather to time as a social and political construction. In this essay, I would like to focus on the heterotopia rather than heterochronia. |

| 11 | This picture belongs to the Public Data Portal and is publicly accessible at https://www.data.go.kr/en/index.do (accessed on 24 May 2025). |

| 12 | See https://www.hani.co.kr/arti/opinion/column/1049786.html (accessed on 24 May 2025). |

| 13 | See https://www.animal.go.kr/front/awtis/shop/undertaker1List.do?menuNo=6000000131 (accessed on 24 May 2025). |

| 14 | This picture belongs to the City of Seoul and is publicly accessible at https://mediahub.seoul.go.kr/archives/919167 (accessed on 24 May 2025). |

References

- Chuhanilponkongsakwankirok 주한일본공사관기록 Documents of the Korea-based Japanese Legation. 1900. Database of Korean History. Available online: https://db.history.go.kr/id/jh (accessed on 24 May 2025).

- Chuhanilponkongsakwankirok 주한일본공사관기록 Documents of the Korea-based Japanese Legation. 1905. Database of Korean History. Available online: https://db.history.go.kr/id/jh (accessed on 24 May 2025).

- Chung, Sujin. 2017. Cheonggye creek, the Shining shrine of Seoul. In Seoulyi Inmunhak (Humanities of Seoul). Paju: Changbi. [Google Scholar]

- Coffey, John. 2020. Pilgrims and Exiles: Leaving the Church of England in the age of the Mayflower. London: Latimer Trust. [Google Scholar]

- Dakamura, Ryohe. 2000. Gongdomgmyojireul Tonghaeseobon Sikminjisidea Seoul. The Colonial Seoul Through the Cemeteries. Seoul: The Institute of Seoul Studies XV. [Google Scholar]

- Eliade, Mircea, and Willard R. Trask, trans. 1971. The Myth of the Eternal Return: Or, Cosmos and History. Bollingen Series. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, Michel. 1986. Of Other Spaces (Des Espace Autres). Translated by Jay Miskowiec. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, vol. 16, pp. 22–27. First published in 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Home, Robert. 1997. Of Planting and Planning: The Making of British Colonial Cities. Oxford: E & PN Spon. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, Il-Yeong. 2016. The Spatial Layout and the Image Formation of the Death Spaces in the Cities in Korea during the Japanese Colonial Rule—Especially on Modern Cemetery and Crematorium. Sarim 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Myung-Gu. 2015. Development of Gangnam. Seoul: University of Seoul. [Google Scholar]

- Kee, Seho. 2017. A Study on the Change of Distance Between the Cemetery and the City Caused by Modernization—Through Comparative Analysis between Paris and Seoul. Seoul: Department of Architecture & Architectural Engineering, The Graduate School, Seoul National University. [Google Scholar]

- Kikuchi, Yuko. 2004. Japanese Modernisation and Mingei Theory: Cultural Nationalism and Oriental Orientalism. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Heesik. 2011. The People outside the Gate―History Space Life of Miari Area. Locality Humanities 6. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Hyon-Sob, and Yongjoon Choi. 2019. Concrete Seoul Map: Bilingual Guide Map to Seoul’s Concrete and Brutalist Architecture. Blue Crow Media Architecture Maps—Folded Map. London: Blue Crow Media. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Euisung. 2021. Rise and Fall of the Seoul Public Cemeteries in the Modern Urban Planning Process, Interdisciplinary Program Urban Design. Seoul: Graduate School, Seoul National University. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Hyang A. 2014. Managing the Living through the Dead-Colonial Governmentality and the 1912 Burial Rules in Colonial Korea. Journal of Historical Sociology 27: 402–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Kate Sangwon, and Huaxin Wei. 2020. Social Media as Heterotopia: Applying Foucault’s Concept of Heterotopia to Analyze Interventions in Social Media as a Networked Public. In School of Design, Archives of Design Research. Hong Kong: The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, vol. 33. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Seongwoo (Linus). 2017. A Study on the Anticommunism Impacts on the Cultural Trends of Korean Megachurches. Seoul: The Graduate School of Methodist Theological University. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, Young Bin. 2019. A Cohort Analysis of Religious Population Change in Korea. The Korean Association of Humanities and the Social Sciences 43: 123–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahm, Kihyun. 2009. Ilcheha chosŏnt’ochichosasaŏp kyehoekanŭI pyŏnkyŏng kwachŏng (The process of changes of Japanese colonial land survey). Sarim. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, Yongha. 1977. Ilchehaŭ Chosŏnt’ochichosasaŏpetaehan Ilkoch’al (Land Survey in Japanese Colonial Period). Hankuksayŏnku 15: 77–164. [Google Scholar]

- Son, Seung-Ho, and Young-Woo Nam. 2006. Changing Urban Structure of Seoul. Gwangju: Darakbang. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Kyubong. 2011. Jido 지도 Maps. Seoul: 21seki Books. [Google Scholar]

- Soo, Mok Man. 2015. Ancestor Worship, Contextualization, Worldview, and Incarnational Mission. The Korean Society of Mission Studie 40. [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson, Andrew, and Anil Gomes. 2024. Kant on the Pure Forms of Sensibility. In Oxford Handbook of Kant. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Takamura, Ryohei. 2000. Kongtongmyochirŭl t’onghaesŏ pon singminchisidae Soŭl-1910nyo˘ndaerŭl chungsimŭro (Seoul in colonial period from the view of public cemetery in 1910s). The Journal of Seoul Studies 15. [Google Scholar]

- Tobler, Waldo Rudolph. 2023. A Computer Movie Simulating Urban Growth in the Detroit Region. Economic Geography 46: 234–40. First published in 1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsurumi, Yusuke. 1943. Gotō Shimpei den (Biography of Gotō Shimpei). Tokyo: Taiheiyo Kyokai Shuppanbu. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).