Abstract

The “hand-waving sacrifice” is a large-scale sacrificial ceremony with more than 2000 years of history. It was passed down from ancient times by the Tujia ethnic group living in the Wuling Corridor of China, and it integrates religion, sacrifice, dance, drama, and other cultural forms. It primarily consists of two parts: ritual content (inviting gods, offering sacrifices to gods, dancing a hand-waving dance, etc.) and the architectural space that hosts the ritual (hand-waving hall), which together constitute Tujia’s most sacred ritual space and the most representative art and culture symbol. Nonetheless, in existing studies, the hand-waving sacrifice ritual, hand-waving hall architectural space, and hand-waving dance art are often separated as independent research objects, and little attention is paid to the coupling mechanism of the mutual construction of space and ritual in the process of historical development. Moreover, with the acceleration of modernization, the current survival context of the hand-waving sacrifice has undergone drastic changes. On the one hand, the intangible cultural heritage protection policy and the wave of tourism development have pushed it into the public eye and the cultural consumption system. On the other hand, the changes in the social structure of traditional villages have led to the dissolution of the sacredness of ritual space. Therefore, using the interaction of “space-ritual” as a prompt, this research first uses GIS technology to visualize the spatial geographical distribution characteristics and diachronic evolution process of hand-waving halls in six historical periods and then specifically analyzes the sacred construction of hand-waving hall architecture for the hand-waving sacrifice ritual space throughout history, as well as the changing mechanism of the continuous secularization of the hand-waving sacrifice space in contemporary society. Overall, this study reveals a unique path for non-literate ethnic groups to achieve the intergenerational transmission of cultural memory through the collusion of material symbols and physical art practices, as well as the possibility of embedding the hand-waving sacrifice ritual into contemporary spatial practice through symbolic translation and functional extension in the context of social function inheritance and variation. Finally, this study has specific inspirational and reference value for exploring how the traditional culture and art of ethnic minorities can maintain resilience against the tide of modernization.

1. Introduction

The Tujia ethnic group call themselves “pi tsi kha” and live in the Wuling Corridor area adjacent to Hubei, Hunan, Chongqing, and Guizhou in China. Since ancient times, they have been a minority with a spoken language but no written language. Their population is about 9.5877 million, ranking seventh among all ethnic minorities in China (https://www.stats.gov.cn; accessed on 15 January 2025).

The hand-waving sacrifice 摆手祭 is a large-scale sacrificial ceremony handed down from ancient times1, integrating religion, sacrifice, dance, drama, and other cultural forms. It is also the Tujia ethnic group’s most sacred traditional festival (Duan 2000, p. 8). The hand-waving sacrifice predominantly consists of two parts: one is the ceremony itself, including inviting gods, offering sacrifices to gods, and the hand-waving dance, and the other is the physical space that hosts the ceremony—the hand-waving hall 摆手堂. Its history can be traced back to the primitive community sacrifice and Wu Nuo culture of the Ba State period (11th to 3rd century BC), more than 2000 years ago. Hence, it is called the “living fossil” of the Tujia Epic (Zhao 2014). It was further developed in the Han and mid-Tang dynasties. In the Ming and Qing dynasties, it evolved into a cross-village joint sacrifice activity developed under the promotion of the Tusi system, becoming a core cultural practice to maintain ethnic identity and regulate social order (Zhao 2014). Nonetheless, with the acceleration of globalization and modernization, the current survival context of the hand-waving sacrifice has undergone drastic changes. On the one hand, the intangible cultural heritage protection policy and the wave of tourism development have pushed it into the public eye. Furthermore, the hand-waving dance has been included in the stage performance and cultural consumption system as “China’s first batch of intangible cultural heritage” (Qiu et al. 2022). On the other hand, the disintegration of the social structure of traditional villages, the outflow of young people, and the fading of religious beliefs have led to the dissolution of the sacredness of ritual space. In this context, the ritual space of the hand-waving sacrifice presents a complex tension between “sacred retreat” and “secular prominence”. Furthermore, its material form, functional attributes, and cultural significance face reconstruction. This transformation is not only about the modern adaptation of the traditional ritual space of the Tujia ethnic group but also reflects the universal fate of the cultural space of China’s ethnic minorities in the context of globalization.

Ritual space predominantly refers to a specific space used to carry out ritual activities. Early studies of ritual space concentrated on its social cohesion function. With a foundation of classical functionalism, E. Durkheim revealed how ritual spaces reinforce social integration and collective identity by demarcating boundaries between the sacred and the secular (Durkheim 1915, pp. 28–40). This perspective was further developed by T. Parsons’ structural functionalism into a systemic framework—his AGIL model posits that ritual spaces serve both as a repository of cultural value systems and as an integrative mechanism for resolving role conflicts (Parsons 1951, pp. 4–27). J. Alexander’s neo-functionalism advanced this discourse by redefining rituals as “social performances,” emphasizing how the dramatic enactment of spatial symbols reproduces social solidarity (Alexander 2004, pp. 4–12, 89–102). Corresponding to functionalist approaches is the critical power perspective. M. Foucault revealed that ritual spaces are the material carriers of disciplinary technologies, where spatial arrangements enforce bodily control (Foucault 1977, pp. 172–77). P. Bourdieu’s field–habitus theory, from a micro-power lens, deciphered the production mechanisms of cultural capital within ritual spaces. He argued that the spatial grammar of church architecture is not merely a physical layout but a spatialized expression of cultural capital (Bourdieu 1991, pp. 163–70). The transitional nature of ritual spaces finds anthropological grounding in V. Turner’s liminality theory (Turner 1969, pp. 94–130), while M. Douglas’s theory further elucidates that the sacredness of space reflects the spatial projection of societal classification systems, with liminal states embodying temporary suspensions of cultural order (Douglas 1966, pp. 35–41). H. Lefebvre incorporated the elements of human, places, objects, practical activities, and social relations into spatial analysis and established the theory of space production, which posits that “social space is a socially constructed product” (Lefebvre 1991, pp. 26–39), emphasizing a triadic dialectic among material space, mental space, and social practices (Soja 1996, pp. 50–53). However, the rise of virtual ritual spaces in the digital age disrupts this traditional tripartite structure. The dissolution of traditional placeness poses critical challenges, while the cultural resilience of local traditional cultures during contemporary adaptation has emerged as a focal scholarly concern (Verhoeff 2012, pp. 89–94; Sumiala 2021, pp. 45–48).

The hand-waving sacrifice ritual is an iconic cultural symbol of the Tujia ethnic group. Moreover, the ritual space constructed by the ritual is also a relatively independent field in Tujia society (Zhao 2014). Existing research concentrates more on the perspectives of religion, architecture, anthropology, and folklore, separating the hand-waving sacrifice ritual, hand-waving dance, and hand-waving hall architecture as relatively independent research objects. Some researchers emphasize the role of the hand-waving sacrifice ritual as a large-scale ritual in carrying the collective memory of the Tujia ethnic group (Wang and Bai 2022); some concentrate on the cultural significance and inheritance value of the hand-waving dance as one of the first instances of intangible cultural heritage in China (Qiu et al. 2022; Zhou 2021; Ma and Zheng 2004) and its driving role in the current tourism economy (He 2022); and others view the hand-waving hall as a static container for rituals, ignoring the constructive role of the space itself in the ritual process, the behavior of participants, body dance movements, and the production of meaning (Deng and Li 2013). As a result, few studies have focused on the interactive association and mutual coupling mechanism between rituals and space in diachronic development. In fact, the most significant difference between the hand-waving sacrifice and other sacrificial activities or folk dances is its reliance on a specific space (hand-waving hall). They are interdependent and indispensable.

As a consequence, this study takes the interaction of “space-ritual” as a clue to specifically analyze the transition of the Tujia people from a closed and conservative traditional society to a contemporary society characterized by the convergence of diverse cultures; the isomorphic relationship between the architectural space of the hand-waving hall and the process, path, and orientation of the hand-waving sacrifice, which contributes to the historical construction of sacredness; as well as the mechanisms underlying the ongoing secularization of the spatial domain of the hand-waving sacrifice in contemporary society. This study attempts to reveal how the Tujia ethnic group, a non-literate ethnic group, achieved the unique path of intergenerational transmission of cultural memory through material symbols (such as hand-waving halls and sacred trees) and physical practices (such as ritual paths and hand-waving dance movements), as well as the transformation process of the hand-waving sacrifice ritual from sacred space to secular space in the context of social function inheritance and variation, to explore the possibility of embedding sacredness into contemporary spatial practice through symbolic translation and functional extension.

2. Hand-Waving Sacrifice

2.1. Study Area

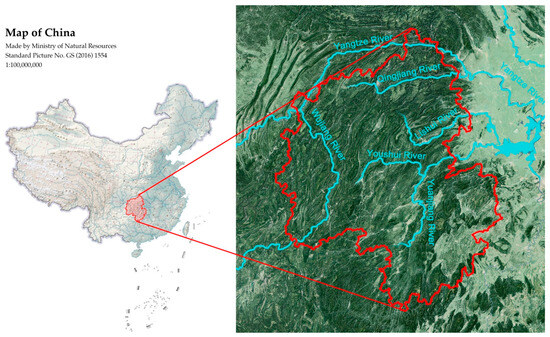

The Wuling Corridor, with the Wuling Mountains as its axis, covers Western Hunan, Western Hubei, Southeastern Chongqing, and Northeastern Guizhou (Figure 1), with a total area of about 115,400 square kilometers and a total population of about 23,120,000. The Wuling Corridor, as a fold zone where China’s terrain transitions from the second to the third terrace, is an important geographical and cultural channel from the Jianghan Plain along the Wuling Mountains and the five water systems of Qingjiang, Wujiang, Yuanshui, Youshui, and Lishui into Southwest China. It has been an essential link between the Central Plains and the Southwest since ancient times. It is also a “historical sedimentation zone” where Chinese ethnic minority cultures converge and the core area of the “Tusi cultural circle” in history (Shen 2022).

Figure 1.

The study area.

The Wuling Corridor is a geographically closed but culturally diverse mountainous area with more than 30 ethnic minorities, including the Tujia ethnic group, Miao ethnic group, and Dong ethnic group. The Tujia, a traditional ethnic group, has the largest population, accounting for about 41% (Bai 2005). As the core settlement area of the Tujia ethnic group, this ethnic group historically formed a “large, scattered settlement and small settlement” living pattern here, nurturing a belief system and sacrificial tradition represented by the “hand-waving sacrifice”. Simultaneously, the hand-waving sacrifice, as a joint sacrificial activity across villages, strengthened the regional cultural identity (Huang and Ge 2009).

2.2. Origin and Development

The origin of the hand-waving sacrifice is intertwined with the agricultural lifestyle and belief system of the Tujia ethnic group in the Wuling Corridor. Early Tujia ancestors predominantly used slash-and-burn farming, and their dependence on the natural environment gave rise to primitive sacrificial activities centered on “praying for a good harvest and warding off disasters”. The prototype of the hand-waving sacrifice can be traced back to the “community sacrifice” of the Neolithic Age. Its core function was to pray for a good harvest and drive away epidemics through collective dance and sacrifice. The ritual space at this stage was mostly based on natural sacred areas (such as sacred trees and caves), and no fixed buildings had yet been formed. Participants were blood-related families. Furthermore, the objects of worship were primarily natural gods (tree, mountain, and grain gods), reflecting the distinct characteristics of animism (Huang 2011).

Throughout the Tang and Song dynasties, with the establishment of the “control system” 羁縻制度 by the central government in the Wuling Mountain area, the Tujia ethnic group gradually formed a stable settlement form, and the hand-waving sacrifice began to be combined with ancestor worship. During this period, the spatial carrier of the hand-waving sacrifice shifted from sacred natural areas to artificial structures, and the early “hand-waving hall” prototype appeared. Its form was mostly modeled after the community altar in the Central Plains, but it retained the localized sacred tree element—an ancient tree was set up at the center of the sacrifice. Furthermore, stones were piled under the tree to form an altar, creating a vertical symbolic system of “tree-altar-people” (Zhao 2014). The ritual time was also fixed in the first month of the lunar calendar, which was tightly correlated with the farming cycle: the “opening of the community” on the third day of the first month symbolized the start of spring plowing. More importantly, the “bidding farewell to the gods” on the fifteenth day of the first month marked the beginning of farming. Throughout this period, the hand-waving dance was closer to a primitive narrative language whose movements mostly simulated farming (sowing and harvesting) and hunting. More importantly, physical practice and production knowledge were passed down through intergenerational repetition.

The period of the Ming and Qing Dynasties—the period when Yongshun Xuanweisi 永顺宣慰司 (Tusi regime) governed the Wuling Corridor region (13th–18th centuries)—was a critical stage in the transformation of the hand-waving sacrifice from an agricultural ritual to an ethnic symbol (Huang 2022). In order to strengthen the legitimacy of its rule, the Tusi regime incorporated the hand-waving sacrifice into the “official sacrificial” system and linked it to Tusi king worship through myth reconstruction. For instance, the Yongshun Peng Tusi claimed that their ancestor, Duke Peng, was a descendant of the “Eight Tribes Kings” and added a statue of Duke Peng to the hand-waving hall shrine, turning the object of worship from a natural god to a personified ruling authority (Volume 4 of Records of Yongshun Xuanweisi 永顺宣慰司志 卷四). This political transformation prompted the hand-waving sacrifice to break through the scope of a single village and develop into a cross-regional joint sacrificial activity. In accordance with Records of Chenzhou Prefecture 辰州府志 in the Wanli period of the Ming Dynasty, “the Sheba (hand-waving hall) of each village held a joint sacrifice on time, beating drums and gongs, with thousands of dancers and crowds of spectators” 各寨舍巴(摆手堂)至期共祭,击鼓鸣锣,舞者千人,观者如堵, which demonstrates that its social integration function surpassed agricultural prayers and became a cultural tool for Tusi to “rule the subordinates and unite the people”.

After the policy of bureaucratization of native officers 改土归流 was implemented throughout the reign of Emperor Yongzheng of the Qing Dynasty (1735), the political authority of the Tusi collapsed. However, the hand-waving ceremony survived because of cultural inertia, gradually shedding its political attributes and turning to expressing ethnic identity. The record in the local chronicles, that the “Tujia ethnic group danced the hand-waving, while the Han nationality was puzzled by it” 土人跳摆手,汉民观之不解 (Qianlong’s Yongshun Prefecture Chronicle 永顺府志), highlights that it became a cultural boundary that distinguished the “Tujia ethnic group” from “the Han nationality”. From the late 19th century to the early 20th century, the field notes of Western missionaries (such as Chamberlain’s Survey of Tujia ethnic group in Western Hunan 湘西土人调查) demonstrated that the recitation of the migration epic was added to the hand-waving ceremony. Furthermore, the dance movements were integrated into war simulations (such as “armor waving” 披甲摆 as well as “spear and dagger-axe waving” 矛戈摆), suggesting the reconstruction of the memory of ethnic historical trauma. Throughout this period, although the buildings of the hand-waving hall were damaged by war, their spatial symbols (such as the sacred tree, bronze bells, and the tablets of the eight great kings) were still deliberately preserved, becoming a material anchor to maintain identity in turmoil.

Contemporary intangible cultural heritage activities (2008 to the present) further accelerated the symbolic transformation of the hand-waving sacrifice. With the inclusion of the Tujia hand-waving dance in the national intangible cultural heritage list, the regional ritual originally confined to the Wuling Mountain area was promoted to a component of the “pluralistic unity” cultural pattern of the Chinese nation. Thus, the local government reshaped the hand-waving sacrifice into a “Tujia cultural business card” by rebuilding the hand-waving hall and compiling standardized dance teaching materials. It is noteworthy that in this process, the original function of agricultural prayer has tended to fade: field surveys in Shuangfeng Village, Yongshun, illustrate that the younger generation of villagers mostly regard the hand-waving sacrifice as an “art passed down by their ancestors” rather than a sacred practice associated with their livelihoods (Interview Record, 2022). Nonetheless, the core symbols of the ritual space (such as the sacred tree and the circular dance path) are still retained, suggesting the adaptive adjustment of the ethnic symbol system to the impact of modernity.

2.3. Spatiotemporal Distribution

2.3.1. Data Source

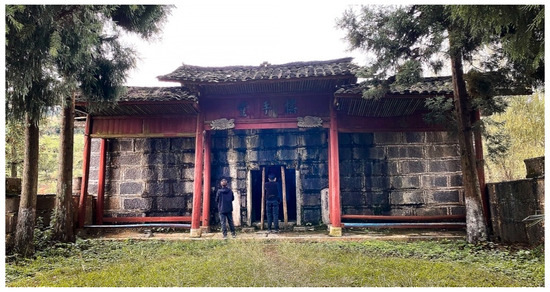

Historically, hand-waving halls have undergone two large-scale demolitions2. Furthermore, the number of historical relics has been dramatically reduced. Most existing hand-waving halls have been rebuilt in the past 30 years (Figure 2). In accordance with the records of many historical documents and local chronicles such as Yongshun Prefecture Records 永顺府志 and Xiangxi·Customs Records 湘西·风俗志, “there is one small hall in a village” 一寨一堂 and “there is a small hall every five miles, and a large hall every ten miles” 五里一小堂,十里一大堂 (Yuan 2004). This reflects the bustling scene of numerous hand-waving halls, where each Tujia village in the Wuling Corridor area had at least one. Consequently, based on field surveys and literature records, this study attempts to roughly restore the spatial geographical distribution and historical evolution of hand-waving halls rooted in the geographical distribution of traditional Tujia villages in the Wuling Corridor area.

Figure 2.

A hand-waving hall in Rebala Tujia Ethnic Village, Longshan County, Xiangxi Prefecture, Hunan Province.

Beginning in October 2020, this research team conducted in-depth investigations of 75 traditional Tujia villages and 43 hand-waving halls in Hubei Enshi Tujia and Miao Autonomous Prefecture, Hunan Xiangxi Tujia and Miao Autonomous Prefecture, Chongqing Youyang Tujia and Miao Autonomous County, Guizhou Yanhe Tujia Autonomous County, etc.; made participatory observations with respect to 12 typical hand-waving halls (Shemihu Village in Laifeng County, Hubei, Shuangfeng Village in Yongshun County, Hunan, etc.), recording the ritual process, spatial transformation, and behavior of participants; and conducted in-depth interviews with 38 key informants (Tima, intangible cultural heritage inheritors, villagers, and tourism managers) to gain an in-depth understanding of the evolution of the architectural form of the hand-waving hall and the hand-waving sacrificial ceremony. Simultaneously, 648 Tujia traditional villages (hand-waving halls) in the Wuling Corridor area were collected through historical geographic information data retrieval, historical document retrieval, and local chronicle retrieval. The data sources include the China Local Gazetteers Database, Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China (https://www.mohurd.gov.cn, accessed on 12 January 2025), the China Historical GIS (http://www.fas.harvard.edu/~chgis, accessed from 7 March 2022 to 15 January 2025), and the Chinese Historical Geography Digital Application Platform (https://timespace-china.fudan.edu.cn/FDCHGIS/homePage, accessed from 18 August 2022 to 15 January 2025).

All geoprocessing procedures in this study used the GCS_WGS_1984 coordinate system. All maps drawn during the study, as well as the administrative boundaries and national boundaries of the relevant areas, were rooted in the Ministry of Natural Resources of the People’s Republic of China (https://www.mnr.gov.cn/, accessed on 5 January 2025) provided by the National Geographic Information System. The basic geographic data on topography, landforms, water systems, transportation, etc., all stem from the National Geomatics Database (National Basic Geographic Information Database, 2018 version) and the National Natural Resources and Geospatial Basic Information Database (https://www.sgic.net.cn/portal/index.html#/Home, accessed on 5 January 2025).

2.3.2. Methods

- (1)

- Spatial distribution index

This index includes name data, location data, and coordinate data. The location data include the administrative division information of the province (municipality), region (state), city (county), town, township, and village where the Tujia village (hand-waving hall) is located, such as Lianghekou Village, Shadaogou Town, Xuanen County, Enshi Prefecture, Hubei Province 湖北省恩施州宣恩县沙道沟镇两河口村. The coordinate data include the longitude, latitude, and altitude of all Tujia villages.

- (2)

- Time period index

Based on the time when the hand-waving hall was formed, the historical background of its development and changes as recorded in local chronicles, and the distribution of information on the age of traditional Tujia villages (hand-waving halls), this study divides the development and evolution of hand-waving halls into six historical periods, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Six temporal stage indices.

- (3)

- Dot density estimation (refer to Appendix A)

- (4)

- Standard deviation ellipse analysis (refer to Appendix B)

2.3.3. Data Distribution Analysis

- (1)

- Spatial distribution characteristics of traditional hand-waving halls

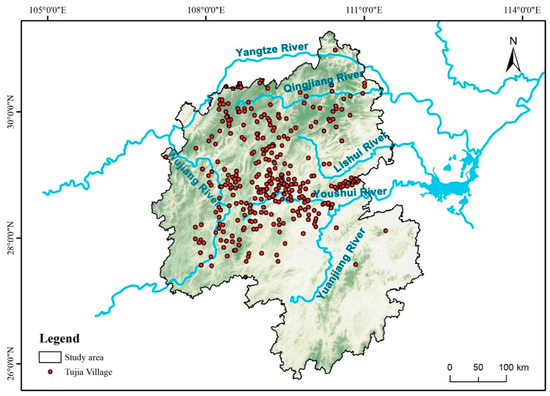

The hand-waving halls are predominantly distributed in 41 prefectures or cities under the jurisdiction of the four provincial administrative regions (including one municipality) in the Wuling Corridor. With respect to number, Table 2 shows that the top three are Longshan County and Yongshun County in the Xiangxi Tujia and Miao Autonomous Prefecture of Hunan Province, as well as Youyang County in Chongqing City, accounting for about 20.1% of the total.

Table 2.

Weighted statistics of the spatial distribution of the dot density of hand-waving halls (in terms of country).

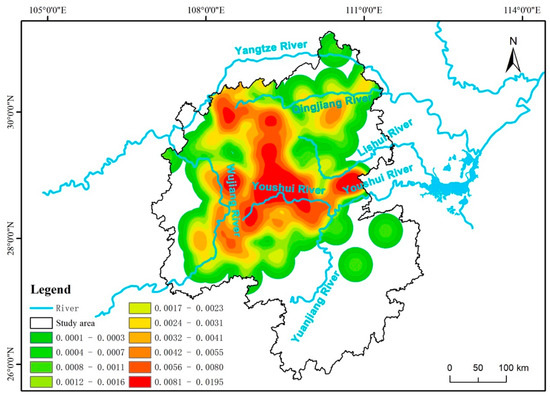

With regard to spatial distribution, Figure 3 illustrates that, historically, hand-waving halls are principally distributed in the central and northern areas of the Wuling Corridor, suggesting both a central tendency and a discrete dispersion. In line with the average of the variable series, the central tendency reflects the common nature of the distribution of hand-waving halls under certain spatial conditions—that is, the center of the data is predominantly concentrated in the Youshui River Basin, the Qingjiang River Basin, and the Wujiang River Basin. Figure 4 reveals that the most concentrated area is on both sides of the Youshui River. The birthplace of the river is linearly concentrated in Youyang County, Chongqing City, Longshan County, Yongshun County, and Yongding County, Xiangxi Tujia and Miao Autonomous Prefecture, Hunan Province; the Qingjiang River Basin is principally concentrated in Shizhu County, Chongqing City, Xianfeng County, and Lichuan County, Enshi Tujia and Miao Autonomous Prefecture, Hubei Province; and the Wujiang River Basin is principally concentrated in Yanhe County and Dejiang County, Tongren City, Guizhou Province. This concentration trend not only reflects the distribution pattern of the traditional hand-waving hall but also demonstrates that Tujia villages developed alongside rivers throughout history, and water systems became an essential factor affecting the spatial distribution of the hand-waving hall and the spatial characteristics of cultural connections through water systems. Outside of the above-mentioned areas, the spatial distribution of hand-waving halls clearly suggests a relatively discrete trend, and the numerical amplitude is large, reflecting the overall spatial characteristics of small concentration and large dispersion in areas outside of the agglomeration area.

Figure 3.

The spatial distribution of hand-waving halls.

Figure 4.

The density characteristics of the spatial distribution of hand-waving halls.

- (2)

- Characteristics of the time evolution of traditional hand-waving halls

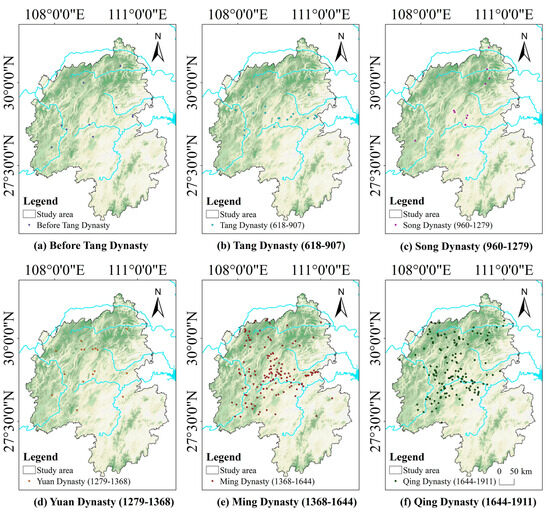

Table 3 shows that the number of hand-waving halls generally increased over time, from 54 in the Tang Dynasty (Stage II) to 648 in the early 20th century, with an average increase of about 8.22% in the six historical periods. The Ming Dynasty (Stage V) was the period with the highest number of hand-waving halls (276), and the Qing Dynasty (Stage VI) ranked second with regard to the amount of construction (267), but the construction density (0.96) was the highest.

Table 3.

The weighted statistics of the number of hand-waving halls in six historical stages.

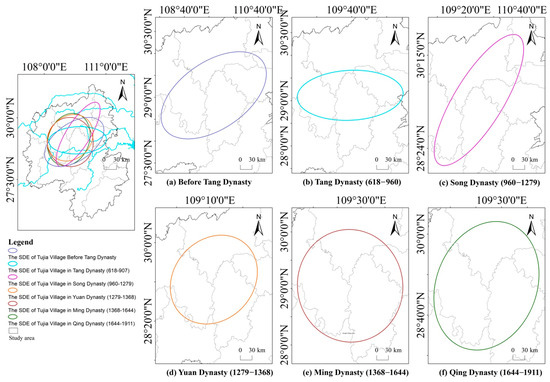

Figure 5 and Figure 6 highlight the distribution changes and propagation directions of hand-waving halls in different historical stages:

Figure 5.

The density distribution of hand-waving halls in six historical periods.

Figure 6.

Standard deviation ellipse analysis of hand-waving halls in six historical periods.

In the Tang Dynasty, as the initial stage of the material space of hand-waving halls, the spatial distribution illustrated a distinct basin dependence, principally in the Lishui River and Youshui River valleys, with a linear distribution from east to west. This is highly consistent with the migration corridors of the “Southern Barbarian” 南蛮 tribes in the Wuling Mountain area at that time and the direction of the ancient salt and tea roads. The earliest batches of hand-waving halls were mostly located at the intersection of military garrisons and folk markets on the valley terraces. Moreover, they undertook the dual functions of ethnic group sacrifices and border governance.

In the Song Dynasty, with the emergence of the Tusi system and the development of mountain agriculture, the propagation axis of the hand-waving hall changed significantly, forming a diffusion trend along the southwest–northeast direction of the main ridge of the Wuling Mountains. The surge in the number of hand-waving halls in the Qingjiang River Basin particularly highlighted the shift of the regional political center. The power game between the Rongmei Tusi 容美土司 in Western Hubei and the Peng Tusi 彭氏土司 in Western Hunan prompted hand-waving hall penetration into the military frontier as a cultural landmark. Its distribution density was positively correlated with the Tusi garrison strongholds (r = 0.63).

While maintaining the traditional development pattern along the river, the Yuan Dynasty further strengthened the cultural communication function of the water network. The number of hand-waving halls in the five major river basins of Qingjiang, Wujiang, Yuanshui, Youshui, and Lishui accounted for 82% of the entire region. Among them, in the basin of the Mengdong River, a tributary of Youshui, there was a hand-waving hall every 5 km. This model of “expanding halls by water” not only benefited from the material circulation introduced by the water transport system but also reflected the inherent logic of the Tujia cultural circle in spreading beliefs along waterways.

Throughout the Ming and Qing Dynasties, the spatially explosive growth of hand-waving halls (accounting for about 79% of the total) was ushered in. Its distribution broke through the limitation of a single basin and formed a homogenized pattern with Longshan County and Yongshun County in the middle reaches of the Youshui River as the absolute core (accounting for 33% of the total). It radially diffused along the mountain folds and secondary water systems—infiltrating to Sinan Prefecture in Northeast Guizhou through the Wujiang River in the west, extending to the edge of Dongting Lake Plain along Lishui River in the northeast, and entering the hinterland of Xuefeng Mountain along the tributary of Yuanshui River in the southeast. Even in Lichuan and Enshi in the Qingjiang River Basin in Southwestern Hubei, the cultural integration of hand-waving halls (such as the double-phoenix Chaoyang variant combined with the stilt house form) was demonstrated. This “core-periphery” dissemination trend not only confirms the cultural integration introduced by the heyday of the Tusi system in the Ming and Qing Dynasties but also reflects the adaptive expansion of Tujia cultural space under the policy of military farming and Han–Tu division, culminating in the construction of a regional cultural community across contemporary administrative boundaries in the Wuling Corridor.

3. Sacredness: The Historical Construction of Hand-Waving Sacrifice Ritual Space

3.1. The Hand-Waving Hall as the Physical Space for the Hand-Waving Sacrifice Ritual

The hand-waving hall is usually located on high ground near the village or in areas with special geographical and cultural significance, such as near ancestral cemeteries, water sources, or ancient sacred trees. For instance, a hand-waving hall built on a hillside overlooks the entire village, highlighting the solemnity of the sacred space and symbolizing the protection and surveillance of the gods on the tribe. In contrast, a hand-waving hall built by a stream implies a source of life and the spirit of the gods. The orientation of the hand-waving hall is not like the traditional Chinese architecture that faces south, but it must occupy the best local Feng Shui environment. Usually, the main axis running through the entire architectural space must face a distant mountain.

As the material carrier of hand-waving sacrifice ritual, the hand-waving hall consists of three elements: the temple, the courtyard, and the sacred tree, which are arranged in a particular spatial order to form a ritual space. Judging from the many remaining buildings distributed in the Wuling Corridor area, especially in the Youshui River basin and the Qingjiang River basin, the hand-waving hall is mostly rectangular in shape and has a “courtyard in front and temple in the back”. As the main building, the temple adopts a through-beam wooden structural frame. The eaves and wing corners of the roof present a unique flying eaves shape, reflecting the traditional wooden construction skills and aesthetic style of the Tujia ethnic group. The temple’s main hall enshrines statues or tablets of gods and ancestors, most of which are statues of the three Tujia ancestors (Duke Peng, Grand Official Xiang, and Mr. Tian). Some statues are wrapped in red cloth that has been worn over the years so that the original appearance of the Tusi king cannot be seen, which further highlights his mystery (Qiu et al. 2022). The sacrificial procedures of the hand-waving sacrifice, such as sweeping the hall, inviting the gods, and setting the tablets, are all performed in the temple. The courtyard in front of the temple is usually a vertical rectangle surrounded by a long stone wall to prevent people outside the tribe or village from watching. The courtyard is large, with a “sacred tree” in the middle, forming the center of the space and the ritual center of the hand-waving dance. The hand-waving hall serves as a medium for communication between the gods and ancestors and the secular people. Through the temple, the courtyard, and the sacred tree, the hall organically integrates Heaven, Earth, and man; strengthens the spatial field where the Tujia ethnic group are present together with the gods and ancestors throughout the hand-waving sacrifice; and reflects the material space style under the cultural concept of “harmony between man and nature” 天人合一 of the Tujia ancestors.

For instance, according to a study, the Shemihu 舍米湖 hand-waving hall (Figure 7) in Laifeng County, Hubei Province, was built in the eighth year of the Shunzhi reign of the Qing Dynasty (1651). It is located on the hillside of Xiaojigong Mountain in the south of the village, facing the water and its back to the mountain. The hall enshrines three Tujia ancestors. On the central axis of the hall is a stone corridor leading directly to the courtyard gate. The vertical rectangular courtyard covers an area of about 550 square meters (Deng and Li 2013). The site selection and spatial layout of the Shemihu hand-waving hall indicate that the hall and the courtyard are two spaces that are different but internally related. The Tujia ethnic group holds that the hall is where the gods and ancestors live. Furthermore, it is also the core place where the gods and ancestors receive worship from their descendants. It is the central space of the absolute sacred space. Even when holding ancestor worship ceremonies, the tribesmen can only stand outside the hall’s threshold to pay homage. The courtyard outside the hall is an auxiliary space of the sacred space. After the sacrificial ceremony, the waving dance activities are conducted in this space to entertain the gods and themselves. The clear division of space and the clan rules and traditions that do not cross the line are necessary for the spiritual expression of the Tujia ethnic group’s reverence and worship of their ancestors. For thousands of years, the Tujia ethnic group maintained and passed on their national beliefs and ethnic relations in this specific space.

Figure 7.

The Shemihu hand-waving hall in Laifeng County, Hubei Province.

3.2. Sacred Tree and Spatial Construction

The gods worshipped in the Tujia ethnic group’s hand-waving sacrifice have evolved from primitive worship to polytheism and from nature worship to personality worship. This not only reflects the polytheistic belief system of the Tujia ethnic group but also indicates the close association with their historical development, national psychological identity, and cultural exchange. Specifically, the first gods worshipped were natural gods (the sacred trees) and then totem gods (the tiger gods). Throughout the vassal state and county period, the worship of the eight great gods arose in confrontation with powerful forces. When agricultural production developed, the gods of grains and land were worshipped. Throughout the period of Tusi rule from the Yuan, Ming, and early Qing dynasties, the Tusi kings and cultural heroes recognized by the Tujia ethnic group were worshipped. Most of the Tusi kings we see today are worshipped in the hand-waving halls, which have been inseparable from the far-reaching influence of the Tusi rule system for more than 400 years.

Among various gods, the original worship of the sacred tree did not decline or disappear with the historical evolution of the object of faith. It has always stood in the center of the courtyard of the hand-waving hall, developed into the central symbol of the hand-waving dance space, and participated in the construction of the overall ritual space. As a mountain ethnic group living in the Wuling Mountain area for generations, the Tujia ethnic group holds that forests and trees are vital to their lives. The fuel needed for daily life and the materials for building houses are taken from the mountains and forests, and the strong vitality of trees makes them feel awe. As a consequence, all Tujia villages have the custom of worshiping big trees: they fix iron nails around the big trees to prevent people from cutting them down, they cover the big trees with colorful red decorations and offer sacrifices to them during festivals, they pray for the blessing of the ancient trees for their children, they ask the ancient trees for medicine when their family members are sick, etc. (Interview Record, 2021).

The towering sacred tree in the center of the hand-waving hall is the Pushe Tree 普舍树 (a sacred tree descended from the sky in Tujia folklore) recorded in the Huguang Tongzhi 湖广通志 during the reign of Emperor Kangxi:

There is a tree in Manshui Village, Shizhou, named Pushe Tree. Pushe means elegance in Chinese. In the past, the ancestor of the Qin family cut down a strange tree at Dongmen Pass. The tree followed the flow to Nache, where it took root and grew again, with hundreds of flowers blooming in all seasons. The descendants of the Qin family sang and danced under it, and the flowers fell by themselves, so they took them and wore them in their hairpins. When other families sang there, the flowers did not fall. It was particularly unusual. 施州漫水寨有木,名普舍树。普舍者,华言风流也。昔覃氏祖于东门关伐一异木,随流至那车,复生根而活,四时开百种花。覃氏子孙歌舞其下,花乃自落,取而簪之。他姓往歌,花不复落。尤为异也。(Tongzhi Laifeng Xianzhi·zazhuizhi 同治《来凤县志·杂缀志》 [Tongzhi Laifeng County Annals: Miscellaneous Records] 1998)

The folk tale of the Hand-waving Dance and the Pushe Tree in Laifeng County further explains this record:

Legend has it that a spring rain a long time ago caused a flood in the Youshui River Basin. One night, a strange tree floated down the river and took root in front of the door of a man named Qin. The next morning, the old man of the Qin family was surprised to see the tree with green branches and leaves and full of flower buds. He didn’t know whether it was a blessing or a curse, so he quickly summoned the old and the young to kneel down under the tree, and the flood subsided. Once the story spread, the surrounding neighbors jumped under the tree, and the flower buds on the tree grew countless red, green and white flowers, which was the Pushe Tree. The dance performed around the Pushe Tree is the hand-waving Dance. 传说很久以前的一场春雨造成酉水流域水灾。一天晚上,顺水飘来一异木,在一覃姓门前生根。次日晨,覃家老人惊见此树青枝绿叶,满树花苞,不知是福还是祸,急召老小在树下跪拜,结果洪水消退。此事一传开,周围乡邻齐拥树下跳跃,满树花苞遂生出无数红绿白花,即普舍树。围着普舍树跳的舞就是摆手舞。(Tian et al. 2007, p. 57)

In support of the idea of harmony between man and nature, the sacred tree is indispensable in the ritual space of the hand-waving hall. The Tujia ethnic group regards it as the tree of the universe and the medium for villagers to communicate with the gods. It is said that the big trees in the center of the hand-waving hall courtyards in Shemihu and other places are all remains of the early worship of sacred trees3 (Interview Record, 2021). As a vertical axis, the sacred tree connects Heaven and Earth. Its branches extend upward to symbolize connection with the world of gods, and its roots go deep into the land to metaphorically represent the roots of the ethnic group. In the plane layout, the sacred tree is located in the center of the courtyard, and the circular waving dance unfolds with the tree trunk as the center of the circle, forming a centripetal space. This spatial construction with natural objects as the carrier realizes the dual integration of the physical field and the spiritual world.

3.3. Ritual and Spatial Construction

3.3.1. Process

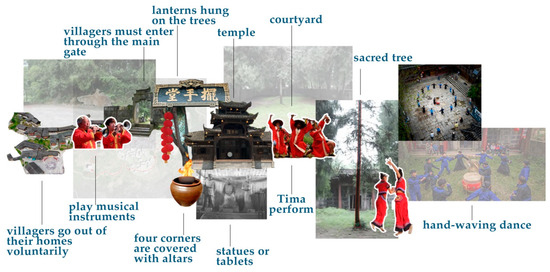

The traditional hand-waving sacrifice is a collective activity. The complete process includes four stages: “inviting gods-offering sacrifices to gods-entertaining gods-bidding farewell to gods”. It starts on the third day of the first lunar month and lasts from three to seven days and has a strict time order (Figure 8). Using the three-day period as an example, on the morning of the first day, the Tima (the master of the altar, a religious clergyman of the Tujia ethnic group—the medium between the Tujia ethnic group and the gods) led the people to the mountains to collect “sacred wood” (lilac branches). At noon, the “sacred flag” was erected in front of the hand-waving hall. At night, the “opening altar and singing ancestors” epic recitation was held; the next day, sacrificial activities and collective hand-waving dances were carried out; on the third day, after “bidding farewell to gods”, the participants shared the sacrificial meat, completing the sanctification cycle of people and gods eating together (Zhao 2014). This time structure is essentially a cultural coding system.

Figure 8.

The process of the hand-waving sacrifice.

(1) Inviting the gods: At the beginning of the hand-waving sacrifice ritual, the tribesmen, led by the Tima, set out from a specific location in the village and slowly walked along the predetermined route to the hand-waving hall. The Tima summoned the gods throughout the march by chanting incantations, singing scriptures, ringing bells, etc. The team’s steps were neat and solemn, as if crossing the secular and sacred boundaries. When the team stepped into the hand-waving hall, people entered the mysterious and awe-inspiring sacred space from the daily secular space. This spatial transformation was strengthened through the physical perception and psychological experience of the ritual participants, symbolizing the transition from the human world to the divine world (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

The process of the hand-waving sacrifice in the hand-waving hall.

(2) Offering sacrifices to the gods: The offering ceremony is held in the shrine of the hand-waving hall, which is the core of the hand-waving sacrifice ceremony. The first procedure is “sweeping the hall”, in which the Tima leads several people to draw talismans, chant spells, and use brooms to clean the hand-waving hall to prevent evil things from entering. The second procedure is “inviting the gods into the hall”. First, dozens of people present offerings, holding plates above their heads with both hands and marching forward in two rows with large strides. After the offerings are presented on the table, the Tima performs divination. If the bamboo basket divination illustrates that both sides are facing upwards or one is facing up and the other is facing down, it means that the gods have been invited successfully, indicating that the ancestors have moved to the hand-waving hall and can be placed in their tablets. The third procedure is “setting the tablets“. The Tima reports the names of various offerings to the gods and invites them to enjoy them. After the report, the Tima burns incense and paper; the ceremony participants bow and kowtow; and ox horns, trumpets, earthen flutes, gongs and drums, firecrackers, etc., sound together.

(3) Entertaining the gods: The ceremony takes place in the courtyard. First, the Tima sings ancient sacrificial songs to invite the gods and ancestors to enter the ritual area. Then, the Tima performs Tujia traditions such as stilt walking and knife climbing and sings the merits of the ancestors. The performance transforms the courtyard into a symbolic sacred space and provides a physical space for the Tima to entertain the gods. Afterward, the tribe members perform the hand-waving dance around the central sacred tree. Throughout the dance, the sacred tree in the courtyard’s center is hung with lanterns. Under the sacred tree, a big drum or a bonfire is set up, and the strong villagers take turns beating the drums to demonstrate to the gods the hard work, bravery, and love of life of the tribe members. Simultaneously, they pray for the gods to bless the weather, yield good harvests, and ensure the prosperity of people and livestock. In this process, the ritual space becomes a sacred place where people and gods coexist, and the tribe members gain a strong sacred experience and ethnic identity.

(4) Bidding farewell to the gods: This marks the end of the ceremony. The Tima again uses specific ritual movements and lyrics to pour the libation wine into the fire, burn hell bank notes, and respectfully send the gods back to Heaven. The ritual team slowly walks out of the side door of the hand-waving hall along the opposite route to the invitation of the gods. The ceremony of bidding farewell to the gods symbolizes a farewell to the gods and a return of the tribe from the sacred space to the secular space. It allows the sacredness of the hand-waving hall ritual space to be fully presented and closed and lays the foundation for the next ritual cycle.

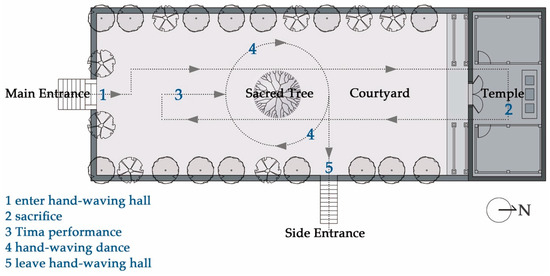

3.3.2. Path

The hand-waving hall is a ritual building in the village. Villagers only visit it during major festivals. In order to maintain the sacredness of the hand-waving hall, participants must enter from the main gate and leave from the side gate during the hand-waving ceremony. When entering, they must walk through the steps, the courtyard, and the sacred tree and wait outside the hall for the end of the ancestor worship. This ritual path is highly consistent with the central axis of the hand-waving hall. There are no extra furnishings in the courtyard where the tribesmen wait, and only two rows of ancient cypresses are placed on both sides of the courtyard. Their arrangement parallels the ritual axis, guiding the tribesmen to worship the gods and ancestors.

Throughout the hand-waving dance ceremony, as the participants’ behavior paths change, a circular ritual path centered on the sacred tree is formed in the square space of the hand-waving hall, expressing the Tujia ethnic group’s ancient spatial philosophy of “the sky is round and the earth is square” and the vast scene in a limited space. Simultaneously, dancing allows the Tujia ethnic group to express reverence for the gods. All movements are derived from the production and living methods of the ethnic group since ancient times, such as migration, farming, fishing, and hunting. They deem that every body movement can reflect the ethnic epic and ritual significance. As a ritual dance, the hand-waving dance can establish a connection with the sacred world.

3.3.3. Direction

As a remote minority in China, the Tujia ethnic group began to implement the Tusi system in the Wuling Corridor region in the late Five Dynasties (928) to strengthen the central dynasty’s rule over the southwest region. It lasted 818 years until the 13th year of Yongzheng’s reign in the Qing Dynasty (1735), when the Tusi system was incorporated into the local administrative department (Huang 2022). For this reason, the order of orientation, the order of the sacrificial personnel, and the order of the sacrificial objects in the hand-waving sacrifice ritual were influenced by the comprehensive influence of the patriarchal rituals of the Han culture in the Central Plains and local witchcraft culture. According to the data distribution analysis above, the hand-waving hall has the spatial characteristics of developing along the river and carrying out cultural contacts with the help of the water system. The influence of Han culture is also more significant in the major river basins.

The hand-waving sacrificial ritual reflects the order of respect and inferiority in Han culture. Nonetheless, unlike the cultural custom of the Central Plains region, where the east is the host, the west is the guest, the south is superior, and the north is inferior, the respect and inferiority of the hand-waving sacrificial ceremony are defined by Feng Shui 风水. After the Feng Shui master determines the location of the hand-waving hall, the orientation of the statue in the hall is determined. The statue usually faces the gate and is set along the central axis of the building in line with the sacred tree. The direction where the statue is located is the superior position, and the opposite direction is the inferior one, thus forming the unique orientation of respect and inferiority of the Tujia ethnic group.

The distribution order of the sacrificial personnel also complies with the Han ethnic rituals of hierarchy. Only the Tima and the prestigious elders in the village can enter the temple, with ancestors being respected, clan members being inferior, the elders being on top, and the young being on the bottom, forming a ritual system in which everyone has their duties within the sacrificial space.

The distribution order of the objects of worship in the temple also indirectly reflects the Tujia ethnic group’s understanding of the association between direction and power. Throughout the Ming and Qing Dynasties, the Tujia area was influenced by Confucianism and changed from nature worship to ancestor worship. Since Duke Peng was the highest in the minds of the Tujia ethnic group, the arrangement of the ancestral statues placed Duke Peng in the center. At the same time, Grand Official Xiang was a famous military general and Mr. Tian was a symbol of diligence and wisdom. Of the two, one was martial and one was civil. In accordance with the Tujia ethnic group’s ancient martial arts and “left noble and right light” cultural habitus, Grand Official Xiang was on the left and Mr. Tian was on the right. For this reason, although the temple building itself is similar to the structural system and construction method of the ethnic residential buildings, when the ancestral statues are placed here, the space is different from any other space and has a cosmological symbolic meaning.

3.4. Construction of Ritual Space Boundaries

3.4.1. Material Boundaries

The traditional ritual space is usually defined by the absolute opposition between the sacred and the secular, and its boundaries are maintained by taboo and purification rituals (Durkheim 1915, pp. 81–86). Meanwhile, as a specific “cultural field”, the access rules and behavioral norms of the ritual space constitute implicit screening mechanisms to exclude “outsiders”, wherein participants’ bodily practices serve both as embodied reinforcement of pre-existing habitus and as a process of internalizing new social norms (Bourdieu 1984, pp. 170–75).

Historically, the hand-waving sacrifice ritual space had clear material boundaries, namely, the dozens of boundary markers erected outside the hand-waving hall courtyard walls, which were set up to establish a clear and secret ritual space. In the past, when the hand-waving sacrifice ritual was held, it was strictly forbidden for people other than the tribe members to cross the boundary markers and enter the ritual space or peek in. If outsiders broke in, they would be made into “human head sacrifices” (Zhang 2011, p. 116). The reason for formulating such strict rules is that, throughout history, most Tujia ancestors were forced to migrate constantly for refuge and eventually lived in seclusion in the mountains. If the migration songs sung by the Tima during the hand-waving sacrifice were heard by outsiders, they would be hunted down by their enemies. As a result, dozens of boundary markers were erected outside the hand-waving hall as a boundary warning for the ritual space (Zhang 2011, p. 95). Although this hatred has long been diluted by time after thousands of years, the habitus of setting up boundary markers and not allowing outsiders to enter has been preserved. The material boundary established by the boundary markers delimits the scope of the ritual field outside the ritual space of the hand-waving hall formed by the courtyard, the sacred tree, and the temple. It becomes the place where the ritual stops or starts and is also the key node for the mutual transformation between the sacred and the secular.

3.4.2. Mental Boundaries

The spiritual boundary is reflected in the mutual construction of material symbols, cultural habitus, and belief systems. Material symbols are used to establish the scope of the ritual field, while the cultural habitus and belief systems of the ethnic group included in the spiritual boundary constitute the endogenous driving force of the ritual operation (Rappaport 1999, pp. 24–26).

The habitus that constructs the belief system of hand-waving sacrifice primarily includes the orthodoxy of worshipping the gods and ancestors, the authenticity of myths and legends, and the inviolability of ritual behavior. This belief system is also strengthened through the identity stratification of participants. For the general public, it predominantly includes the ceremony’s sponsors, organizers, leaders, participants, etc. In the past, a Tujia village was usually a big family. The villagers had the same surname (Peng and Tian were the most common), so they had a strong sense of collective identity and consensus of belief. In their eyes, the three ancestors worshipped in the hand-waving sacrifice ceremony are the most important rulers and protectors in the history of the Tujia ethnic group, and they must be worshipped devoutly during the sacrifice. In addition, they also firmly believe in the authenticity of ethnic epics as well as myths and legends, and they interpret various legends in a unified folk belief through a local logic and efficacy index 灵验指数 (Peng 2012), which also forms the inviolability of worshipping the gods and ancestors before the hand-waving dance celebration. In the hand-waving sacrifice ritual, once this belief system is generated, it is constantly internalized into people’s consciousness, continually shaping the ritual members within the field, who use it as a carrier to pass on ethnic culture from generation to generation.

4. Secular: Contemporary Changes in the Ritual Space of the Hand-Waving Sacrifice

4.1. Diversification of Spatial Functions and Secular Transformation

4.1.1. Publicization of Ritual Venues

Following Emperor Yongzheng’s implementation of the policy of bureaucratizing native officers in 1735, the hand-waving sacrifice persisted due to cultural habits, but the frequency of its observance and the construction of hand-waving halls notably declined. The ritual gradually shed its original political attributes, transitioning toward an expression of ethnic identity. In the 1950s, the newly established Chinese government began identifying various ethnic minorities, and the Tujia ethnic group was initially identified as part of the Miao ethnic group (Ma and Zheng 2004). In order to strive for a single ethnic identity, the local government began to organize and revive the hand-waving sacrifice ritual as a core symbol of Tujia identity. In a sense, this cultural event reflects the Tujia ethnic group’s pursuit of “ethnic identity recognition”.

For this reason, the 1950s became an important dividing line between the traditional and modern hand-waving sacrifice rituals, but until the 1990s, their restoration was intermittent. On the one hand, since most hand-waving halls were destroyed, the rituals lacked the original venues, and some were changed to open spaces or squares in the village. The change in venues led to a decrease in the villagers’ sense of identity. On the other hand, attributable to the intervention of the local county-level cultural center and the adaptation of dance movements, the hand-waving dance was separated from the original sacrificial activities and became a program that toured other places. The local villagers were relatively unfamiliar and resistant to this adapted hand-waving dance (Wang and Bai 2022). After the 21st century, with the strengthening of communication between ethnic minority areas and the outside world and the rise of contemporary social–cultural industries and tourism, local governments in the Wuling Corridor restored the authentic hand-waving sacrificial ceremony and dance movements. In 2008, the Tujia hand-waving dance was included in the first batch of China’s intangible cultural heritage list. The sacred ceremony that initially had to be held in a specific, closed space has also begun to transform into a public cultural activity, which is predominantly manifested in two aspects.

First, the function of cultural display and the tourism economy is highlighted. The hand-waving hall has gradually changed from a simple religious ceremony site to a complex functional space integrating cultural display and tourism. An exhibition area has been added to display the Tujia ethnic group’s historical relics, traditional costumes, handicrafts, and other cultural heritage (He 2022). The space in front of the hall, which was initially used for Tima performances and tribe dances, has also been extended to the village assembly square, where hand-waving dance performances and folk programs are held regularly (accommodating a large number of tourists, who watch), and has shifted from the original “entertaining gods” to “entertaining people”. This change in spatial function has made the hand-waving sacrifice hall move from a relatively closed religious holy place to a more open secular stage, becoming an important brand and image representative of local cultural tourism.

Second, it serves as an expansion of the community’s public activity space. In modern society, the social structure and lifestyle of the Tujia community have undergone significant changes. As the core public space of the community, the hand-waving hall, in addition to hosting traditional religious ceremonies and cultural exhibitions, has become a venue for various public activities by adding daily affairs functions, such as village meetings, art performances, and sports competitions. These secular public activities have enhanced the community’s cohesion and sense of belonging and have made the hand-waving hall more closely connected with the daily lives of community residents, further accelerating its transformation from a sacred to a secular space.

4.1.2. Stage-Based Ritual Space

The ritual space of the hand-waving sacrifice has taken on a stage-like character under the influence of the tourism economy, cultural consumption, and cultural reproduction, which is also a change made by traditional folk activities in adapting to the development of modern society. This change has made the local belief space public. Simultaneously, local cultural practitioners have reconstructed the traditional ritual space in order to promote cultural consumption and reproduction (DiMaggio and Useem 2017, pp. 181–201).

For the Tujia ethnic group, the hand-waving hall is a sacrificial site with cultural memory. This ritual space can provide contemporary people with a sense of “authenticity” through its “historical sense”. For this reason, to restore the “real” scene of this cultural symbol, the government has promoted the repair and restoration of hand-waving halls in some places in the Wuling Corridor.

For instance, according to a study, a hand-waving hall in the middle reaches of the Youshui River, Shuangfeng Village, Yongshun County, Hunan Province, has undergone four reconstructions. Its ultimate goal is to restore the ritual space while being more suitable for stage performance effects. After reconstruction, this ritual space (Figure 10) first broke the closed space defined by the original courtyard wall and the outer boundary monument. It changed the original longitudinal rectangular space form into a circular space more suitable for supporting the body movements involved in the hand-waving dance—the hand-waving terrace. Second, the original one-story, simple-style temple building was transformed into a three-story Tuwang Temple with a four-tiered hip roof and complex and exquisite decorations, which not only enhanced the ritual sense and importance of the building but also highlighted it as the stage background of the central hand-waving terrace. Last, a corridor-style auditorium was added to the periphery of the hand-waving terrace, facing the Tuwang Temple from a distance and breaking the mysterious rule that outsiders are not allowed to see the traditional sacrificial ceremony. This move makes the ritual performance more stage-like (Interview Record, 2023). The ceremony’s main priest and participants (performers) occupy the center of the space, and tourists and other villagers constitute bystanders outside the center. While gazing, they also invisibly reconstruct a new ritual field for the central performers and change its meaning.

Figure 10.

The rebuilt hand-waving hall, Shuangfeng Village, Yongshun County, Hunan Province.

4.2. Ritual Simplification and Symbol Translation

4.2.1. Process Simplification and Contemporary Communication

The complete process of the traditional hand-waving sacrifice carries the temporal order and spiritual beliefs of the Tujia farming society. The three- to seven-day cycle (comprising cleansing the altar to invite the gods, offering sacrifices to the gods, entertaining the gods, and sending the gods back to the mountains) is not only a religious practice but also a periodic cultural cohesion activity of the ethnic group that effectively materializes abstract collective consciousness into perceptible cultural order (Parsons 1966, pp. 55–59). With the accelerating pace of modern society and the growth of the demand for cultural communication, sacrifices generally suggest a trend of simplification. Especially as a sacrificial act for exhibition, it omits the procedures of sweeping the hall, inviting the gods, and setting the tablets. It directly jumps to raising the dragon and phoenix flags, offering tributes on trays, the main priest burning incense and paper, and everyone bowing and kowtowing. The ancestor worship ceremony ends, and then the hand-waving dance begins. Although the core part of the traditional sacrificial ceremony is retained, it also caters to the selective display of the current stage process of the ceremony, compressing the ceremony into a 1–2 h performance.

The specific logic of simplification is as follows: (1) The flexibility of the holding time: The traditional hand-waving sacrifice ceremony strictly follows the Chinese lunar calendar and is held in the first month of the lunar year. Nevertheless, modern performances are often adjusted to weekends to match the tourist schedule, and two performances are launched every day during the Golden Week (national holidays) in May and October. The flexibility of time also eliminates the sacred connotation of the original ritual periodicity. (2) The deletion of ritual links: For instance, the past animal “blood sacrifice” was canceled, and the “inviting gods” link was simplified from Tima going into the mountains alone to the inheritor taking out the pre-made god banner from the prop room. This “de-witchcraft” and “de-risking” transformation further reduced the ritual from a human–god contract to a cultural performance. (3) The functional transformation of the priest’s authority: The role of the master of the altar, Tima, was replaced by the inheritor of intangible cultural heritage, and his identity changed from “spiritualist” to “narrator”. Field surveys illustrate that some inheritors can no longer recite scriptures in the ancient Tujia language and instead use Mandarin to convey the meaning of the actions.

Although this adjustment has removed some of the tradition, it is also grounded in the realistic considerations of cultural inheritance in the contemporary context. It concurrently provides a new path for the contemporary dissemination of the hand-waving sacrifice. On the one hand, short-term performances are more adapted to the viewing rhythm of modern tourism and are more likely to attract the attention of a large number of tourists; on the other hand, the inheritors of intangible cultural heritage use standardized movements and multimedia explanations to enable the hand-waving sacrifice to break through geographical restrictions and give it the ability of universal cross-cultural dissemination. Data illustrate that the number of performances of hand-waving sacrifice in the Wuling Mountain area in 2022 increased 9.3 times compared to 10 years prior, and the audience covered expanded from a single village to an average of about 2.45 million tourists per year (statistics from the Hunan Provincial Department of Culture and Tourism).

4.2.2. Cultural Symbol Translation and Value Reconstruction

The cultural translation of the hand-waving hall focuses on the dialectical integration of traditional forms and modern functions. The “herringbone” double-slope roof, the through-beam wooden structure, and the centripetal pattern of the sacred tree of the traditional hand-waving hall are refined in the core design vocabulary. Through the innovation of architectural structure, materials, and spatial narrative, the traditional architectural language becomes an active medium to activate cultural identity and realize the regeneration of cultural symbols. The “hand-waving Cultural Center” in Laoche Village, Longshan County, Hunan Province, reproduces the curve of the traditional roof with a steel–wood hybrid structure. The top is covered with local fir tiles. The eaves retain the animal-faced tile symbols, but prestressed technology is used to expand the internal span to meet the needs of exhibitions and performances. Similarly, regarding the movement symbols of the dance in the hand-waving sacrifice—such as the “single pendulum” simulating slash-and-burn farming, the “double pendulum” reproducing the cooperation of fishing and hunting, and the “revolving pendulum” metaphor of the spiral route of tribal migration—each movement conveys the body language of the oral epic. Through technical translation and artistic innovation, it has derived multiple forms of expression. Youyang County, Chongqing, established a “hand-waving Dance Movement Gene Bank” and used motion capture technology to record 367 sets of movements of 12 hand-waving dance inheritors so that the hand-waving dance symbols can be integrated into contemporary dance art creation and transformed into digital animation and interactive games (He 2022). In addition, traditional idols can also be transformed into tangible public art symbols. Pengjiazhai in Xuanen County, Hubei Province, uses the “Eight Great Kings” idol as a prototype to design a series of cultural and creative products, such as bronze bookmarks, embroidered hanging paintings, and blind box figurines. The designer retains the core symbols of the idol, such as the tiger head pattern and flame eyebrows, while incorporating cartoon processing to attract young consumers (Interview Record, 2024).

Overall, the symbolic translation of the hand-waving sacrifice is not an isolated phenomenon but an ecosystem for cultural reproduction by linking space, body, and objects. This synergistic effect enhances the effectiveness of cultural communication; its communication effect extends beyond the historical spatial characteristics of cultural connections relying on water systems and stimulates the endogenous power of the community. Since 2021, 23 new cultural cooperation institutions associated with the hand-waving sacrifice have been created in the Wuling Mountain area, and the annual income of villagers has increased by 14% (research by the Rural Revitalization Research Institute of South-Central Minzu University).

4.3. Extension and Redefinition of Boundaries

4.3.1. Physical Expansion: Spatial Collage of New and Old Landscapes

The expansion of the physical boundaries of the hand-waving hall is essentially a spatial projection of the game between globalization and localism. When juxtaposing the newly built cultural square, tourism-supporting facilities, and the traditional hand-waving hall, the closedness of the traditional space is broken, forming a “time and space folding” landscape collage. With the assistance of functional compounding and technological innovation, the sacredness is integrated into modern society more inclusively (Harvey 1990, pp. 240–47; Debord [1967] 1994, p. 165).

In the Cultural Square of Furong Town, Yongshun County, Hunan Province (Figure 11), the ruins of the hand-waving hall, which was originally built in the Qing Dynasty, were included in the overall planning of the public cultural facilities of the “National Cultural Complex”, and a spatial collage was made with the newly built square and intangible cultural heritage exhibition hall. In the core protection area, the original hand-waving hall is the “historical core”, and the traditional sacrificial layout is retained inside. Small ceremonies are held regularly by intangible cultural heritage inheritors. In the live performance area, the square atrium reproduces the form of the traditional hand-waving hall courtyard, and young dancers perform the hand-waving dance on the first and fifteenth day of the lunar calendar every month. Unlike tourist performances, these performances strictly follow the process of “inviting gods-offering sacrifices to gods-entertaining gods-bidding farewell to gods” (Interview Record, 2021). Observation data in 2023 illustrated that about 71% of local young people re-established local cultural identity through such activities (Tan 2024). In the community service area, intangible cultural heritage exhibition halls, libraries, and elderly activity centers are set up outside the square to integrate the cultural symbols of hand-waving sacrifice into daily life. Simultaneously, digital technology has also become a new medium for supporting tradition. With the assistance of virtual reality (VR) to restore the ritual, tourists can wear VR equipment to “participate” in the entire process of the historical hand-waving sacrifice. The immersive experience provided by modern technology also allows young people to better understand the ritual itself and its deep logic. This spatial collage of new and old landscapes symbolizes a creative transformation of sacredness—when traditional space breaks through physical boundaries, its cultural energy radiates further.

Figure 11.

The cultural square in Furong Town, Yongshun County, Hunan Province.

4.3.2. Generalization of Meaning: The Public Rebirth of Sacred Values

The generalization of the meaning of the hand-waving sacrifice space is essentially the transformation of its spiritual core from ethnic belief to public cultural resource. Through community building and popularization via education, its sacredness is integrated into local public life and cultural construction in a more universal value form.

In community building, the hand-waving hall has been transformed through spatial renovation and functional expansion, such as the addition of detachable seats and multimedia equipment, to become a space for villagers to discuss public affairs, perform art performances, or utilize its square as a sports competition space. In education, the hand-waving hall space has been redefined as a “living classroom”. Its sacredness has been transformed into the cultural foundation of educational practice by building it into a university study base and participating in international cultural exchanges. For instance, in 2021, the Xuanen County Government of Hubei Province, together with the School of Architecture, Southeast University and the Università IUAV di Venezia, established the “China-Italy International Architecture Research Camp” to guide scholars in the field of architecture in enhancing the protection and regeneration research of the Tujia stilt wooden architectural heritage represented by the hand-waving hall. The researchers were invited to present their results in the official parallel exhibition of the 17th Venice International Architecture Biennale (LIANGHEKOU, a Tujia Village of Re-Living-Together) (Figure 12). Simultaneously, an intangible cultural heritage course on the traditional construction techniques of stilt houses was created to provide popular science education on Chinese traditional architectural culture for primary and secondary school students, non-architecture students, tourists, and the general public and establish a deep empathy for tradition (Min et al. 2022).

Figure 12.

Official parallel exhibition of the 17th Venice International Architecture Biennale.

The dissolution of boundaries and generalization of meaning in the hand-waving sacrifice space also demonstrate the adaptive wisdom of traditional culture in dealing with the impact of modernity from another perspective. The sacredness has not been eliminated by the expansion of space. Instead, it has gained a richer form of existence through functional integration, technological empowerment, and value translation. When the ritual space moved from a closed sanctuary to an open public domain, its spiritual core also completed the sublimation from “ethnic belief” to “human shared heritage”. This fluid rebirth proves that the vitality of traditional culture does not lie in sticking to boundaries, but in continuing genes in reconstruction with an open attitude, activating new life in transformation, and forming a “historical-contemporary” space-time dialogue.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Ritual space is never merely a static physical container; its essence is a multilayered realm embodying cultural, power, and social relations (Giddens 1990, p. 18), manifesting as a concrete, experiential product of spatial practice that mirrors societal transformations across eras (Lefebvre 1991, p. 33). As a powerful carrier of regional culture and national culture, the hand-waving sacrifice ritual provides insight into the development of the Tujia ethnic group (who have lived in the Wuling Corridor since the historical Ba State) to a minority group living in seclusion in the mountains and forests and then integrating into contemporary society through the evolution of its ritual space. This study uses the interaction of “space-ritual” as a clue to specifically analyze how the sacredness of the ritual space was constructed by the isomorphic correlation between the hand-waving hall architecture and the hand-waving sacrifice ritual in history, as well as the mechanism of the continuous secularization of the hand-waving sacrificial space in contemporary society. Concurrently, it also reveals that in the transformation from sacred to secular, from worshiping gods to entertaining people, and from sacrifice to celebration, this primitive sacrificial belief’s evolution to social art culture has become a microcosm of the survival strategy of ethnic minority regional culture in the wave of modernity. As far as local traditions are concerned, expanding the space of survival by generalizing meaning while protecting cultural genes is an issue worthy of discussion and attention.

First, for the Tujia ethnic group, who only have spoken language but lack a written system, the hand-waving sacrifice ritual space provides a unique mechanism for the intergenerational transmission of cultural memory through the conspiracy of material symbols and physical practice. This mechanism breaks through the cognitive framework centered on written records and provides a new perspective for understanding the cultural survival of non-literate ethnic groups. The architectural form and natural landscape of the hand-waving hall constitute a “memory field” (Nora 1996, pp. 1–20), transforming abstract historical narratives into tangible and perceptible material entities. This spatial coding that reflects the mapping of the directional universe makes the material environment a topological structure of ethnic group memory. The hand-waving dance was originally a narrative language that simulated farming and hunting, and each movement was a physical translation of the oral epic, embedding historical memory into physical habits. Nonetheless, in transforming from sacred to secular space, the traditional hand-waving sacrifice ritual also faces the dual challenges of the decontextualization of material carriers and the performativeness of physical practice.

Second, the transformation of the hand-waving sacrificial space from sacred to secular is essentially the adaptive reconstruction of its social function in terms of modernization (Hobsbawm and Ranger 1983, pp. 263–307). This process is not a simple functional replacement but a self-renewal of the cultural system through the superposition of functions and the replacement of meanings. The contemporary hand-waving sacrificial square, by combining religious rituals and entertainment needs, has been built into a traditional cultural education research classroom. It is a symbiotic model with multiple functions superimposed on the government-led promotion of local cultural tourism projects, presenting the composite characteristics of “sacred and secular integration”. This cultural function transformation reflects the mechanism of influence of the flexible intervention of state power and cultural capital, as well as the various demands of intergenerational differentiation, such as the elderly needing the hand-waving hall to maintain their faith and young people seeing it as a social entertainment space.

Finally, traditional culture has fluid cultural resilience under the impact of modernity, and sacredness can be embedded in contemporary cultural space practice through symbolic translation, functional extension, etc. This study confirms that “sacred-secular” is not a binary opposition paradigm. Although the sacredness of the hand-waving sacrifice space is transforming into secularity, it has not been completely replaced. Instead, it has been embedded in contemporary life in a new form through symbolic translation and functional extension. This “embedded sacredness” generation mechanism provides an ethnographic case for reflecting on the debate that “secularization inevitably leads to desacralization”. Concurrently, there is a paradox with respect to sacredness reconstruction. While this reconstruction continues cultural life, it also buries a deep crisis: When the “embedded sacredness” of hand-waving sacrifice increasingly relies on the support of external systems (such as tourism income and policy support), its cultural autonomy continues to weaken. Hence, functional transformation is dialectical. Secularization is both a survival strategy for traditional culture and a source of crisis in terms of meaning dissipation. The key lies in maintaining the stability of core functions (such as cohesive cultural identity) (Bellah 1985, p. 35). Sacredness itself also has a fluid nature. It is a correlation network that is constantly reconstructed through practice, and its survival depends on the cultural subject’s ability to adapt to a choice between tradition and modernity (Bourdieu 1977, p. 52).