Recasting Antiquarianism as Confucian Orthodoxy: Wang Zuo’s Expanded Essential Criteria of Antiquities and the Moral Reinscription of Material Culture in the Ming Dynasty

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Confucian Foundations: Gewu Zhizhi and the Moral Formation of Wang Zuo’s Scholar-Official Identity

2.1. Gewu Zhizhi as Object Inquiry: A Neo-Confucian Ontology of Things

2.2. Moral Self-Cultivation and Bureaucratic Identity: The Career of Wang Zuo

The compilation began in the middle of the fourth lunar month of the seventh year of the Jingtai reign (1456), when I obtained the old editions from Lords Li and Sun. By the seventh lunar month of the same year, the work of collation and supplementation had reached completion. Nevertheless, it was not until the early fourth lunar month of the third year of the Tianshun reign (1459), when preparations for publication commenced, that the punctuation and collation was finally brought to fruition

是編自景泰七年丙子夏四月中旬,得李、孫二公舊本,至其秋七月考校增完。又至天順三年己卯夏四月上旬,欲命工梓,點校始完。.

In the sixth year of the Tianshun reign (1462), Prefect Wang Zuo oversaw the construction of an Apricot Altar (xing tan) and an archery field (she pu)

天順六年,知府王佐築杏壇、射圃。.

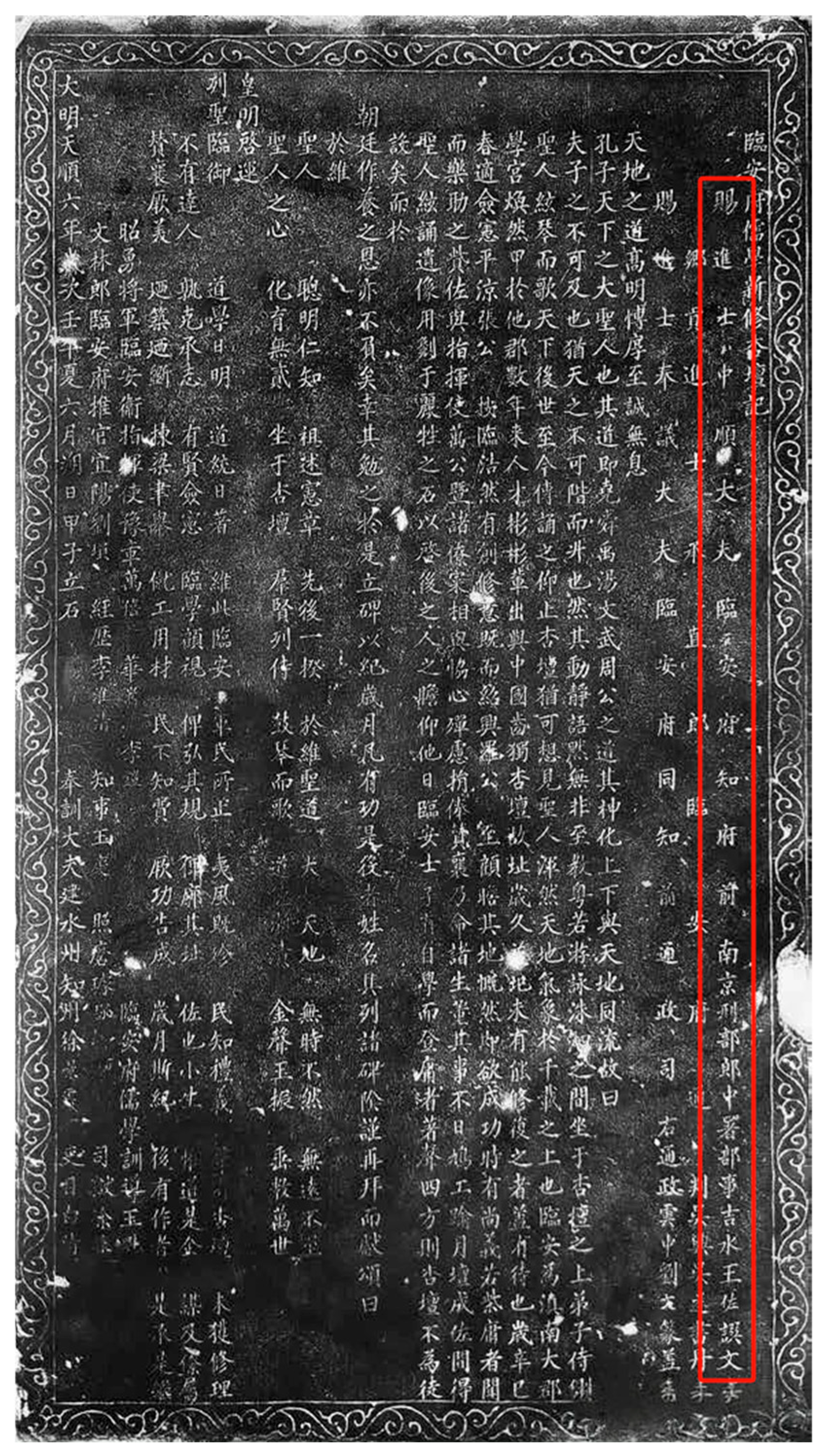

“Composed by Wang Zuo from Jishui, holder of the jinshi degree, zhongshun dafu, Prefect of Lin’an, and langzhong in Nanjing Ministry of Justice, temporarily serving as acting head of the ministry”

賜進士、中順大夫、臨安知府、前南京刑部郎中署部事、吉水王佐撰文。.

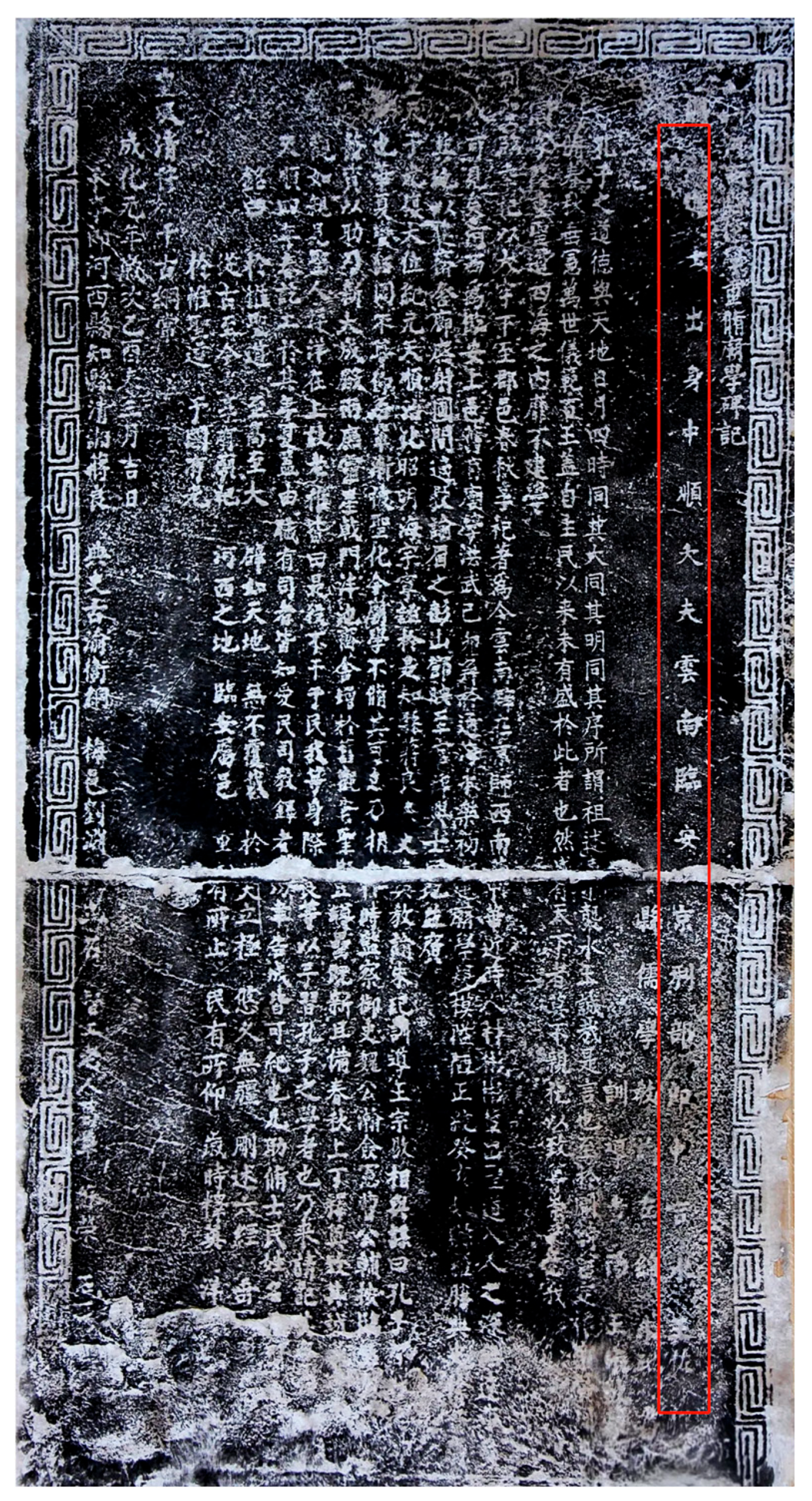

“Composed by Wang Zuo from Jishui, holder of the jinshi degree, zhongshun dafu, Yunnan Lin’an… langzhong in the Nanjing Ministry of Justice”

賜進士出身、中順大夫、雲南臨安□□□南京刑部郎中王佐。.

3. Rewriting Antiquarian Knowledge: Confucianization and Moral Revaluation in XZGGYL

“For continued additions to existing entries, I note ‘hou zeng’ (later addition); for entirely new entries, I note ‘xin zeng’ (new addition), or simply ‘zeng’ (addition). The original text is left unmarked”

其續增者,注曰“後增”。其新增者,注曰“新增”,或只注“增”字。舊本則不注。.

3.1. Reordering Material Hierarchies: Ritual Logic and Confucian Classification

The two earlier editions differed in their arrangement of categories. I hold that nothing is more ancient than the guqin and calligraphy, and they should be scholars’ foremost concern. I have therefore corrected this by placing the guqin and calligraphy at the beginning, and by moving painting to follow the sections on inscriptions on bronze and stone, as well as colophons appended to model calligraphy

二本目錄,始末不同。佐謂物莫古於琴、書,在學者所當先務。今是正之,以琴、書列於卷首,而以畫次於金石遺文、法帖題跋之後雲。.

3.2. Extending Antiquarian Boundaries: Ritual and Political Supplementation

After Emperor Gaozong of Song relocated the court to the south, bureaucratic order gradually declined, and inconsistencies in institutional memory became increasingly pronounced. Some officials had already become close confidants of the emperor. However, they had not yet been promoted to the rank of the “Eight Seats” (bazuo)—[senior posts at the central governance]. According to official regulations, such figures were entitled only to gold belts (jindai) and were not permitted to wear fish-shaped tally pouches (yudai). Nevertheless, upon receiving titles or honors, they were often granted purple-gold fish pouches (zijin yudai), which they did not dare refuse or remove. These cases exemplify a broader phenomenon of borrowed ceremonial forms: individuals who lacked formal entitlement to the regalia of high office nonetheless received its symbols, thereby setting precedents in which name and reality diverged—contributing, in turn, to the erosion of institutional clarity. Although appointments and promotions were typically issued through edicts from the Central Secretariat or by the Ministry of Personnel, such documents often followed inherited templates without proper verification. As a result, they ceased to be critically examined, and scholar-officials gradually abandoned the collective practice of scrutiny

高宗南渡而後,掌故散訛之失也。又有位登法從而未至八座者,於法止賜金帶,不覆佩魚,而每於官職封賜金銜,猶帶賜紫金魚袋,被賜者亦不敢削去,則是借服本有佩魚不得入銜,賜袋雖無佩魚,迺循誤例,名實有無,於是舛矣。蓋凡除授,率中書關尚書賜敕,或下天官給告,因襲前此,不覆檢核,士大夫亦忽而不考雲。.

Nowadays, some subprefectures and counties maintain towers from which drums and horns are sounded, but such installations should only exist at the prefectural level and above. For subordinates lacking delegated regional authority to construct drum-and-horn towers constitute an act of usurpation

今州郡有樓以置鼓角,必會府而後可,非受方面之任而置鼓角,皆僭也。.

“Alas! To favor petty men and estrange virtuous ministers—was not the fall of the Song already inevitable? Must one wait for the future to recognize it? This is what I find most lamentable”

嗚呼!親小人,遠賢臣,宋之不覆振,豈待他日而後見哉?此余所以為深慨者也。.

“The flourishing of the state depends on the collective efforts of many gentlemen, whereas its downfall may be brought about by the actions of a single petty man”

天下國家以眾君子興之而不足,以一小人敗之而有余。.

The relationship between rulers and ministers is inherently delicate. During a time of continuous unrest, Emperor Gaozong of Song relied heavily on Yue Fei. Had he not died, would the Central Plains have fallen? Would the emperor have been compelled to accept a strategy of limited security, ruling from a limited base in the South?

君臣之際難矣!方天下多故,高宗之於武穆,倚藉之如此。使其不死,中原豈有淪沒,主空當至幹偏安乎?.

3.3. Moralized Objects: Replacing Aesthetic Value with Ethical Judgment

Yu the Great was conferred a xuan gui 玄圭 (a black jade scepter), whose color symbolized water. The gui 圭, formerly written as “珪,” is an auspicious jade artifact. Its form is rounded at the top and squared at the bottom, symbolizing the unity of heaven and earth; it was employed in the investiture of feudal lords. The bi璧 is a circular jade object, with its outer roundness representing heaven and its inner squareness representing earth. The cong 琮 is an auspicious jade artifact, approximately eight inches in height and shaped like the hub of a chariot wheel. According to Rites of Zhou, a yellow cong was used in sacrifices offered to the Earth. The zhang 璋 constitutes half of a gui. As recorded in Rites of Zhou, a red zhang was used to perform sacrifices to the south, symbolizing the flourishing of life during summer. The hu 琥 is an auspicious jade artifact. According to Rites of Zhou, a white hu, shaped in the form of a tiger, was used in sacrifices to the west, where its fierce form symbolized the austere spirit of autumn. The huang 璜 is half of a bi. According to Rites of Zhou, a black huang was employed in rituals dedicated to the north, symbolizing the closure and concealment of life, when the earth lay barren and only half the heavens were visible. The heng 珩, dang 璫, pei 珮, and huan 環 are all types of jade ornaments worn on the body. The hu 瑚 and lian 璉 are jade vessels used in ancestral temple rituals during the Yin [Shang] dynasty. The cong 璁 refers to a stone that closely resembles jade. Wufu 珷玞 denotes stones that resemble jade in appearance but differ in substance. In the state sacrifices of the present dynasty [the Ming dynasty], a blue-green bi 蒼璧 is used for offerings to Heaven, a yellow cong for offerings to Earth, and a blue-green bi again for offerings made to Renzu 仁祖 [the father of Zhu Yuanzhang, who was the founding emperor of the Ming dynasty]

禹玄圭,象水色。圭,古作珪,瑞玉也。上圓下方、以象天地,以封諸侯。璧,圓玉。外圓象天,內方象地。琮,瑞玉,八寸,形似車缸,《周禮》以黃琮禮地。璋,半珪。《周禮》以赤璋禮南方,象夏物榮盛。琥,瑞玉。《周禮》以白琥禮西方,為虎形,虎猛,象秋聲。璜,半璧。《周禮》以玄璜禮北方,象多閉藏,地上無物,惟天半見也。珩、璫、珮、環俱佩玉。瑚璉,殷宗廟玉器。璁,石次玉者。珷玞,石似玉者。國朝郊祀天用蒼璧,祀地用黃琮,祀仁祖配天用蒼璧。.

A true lover of antiquity should first consider whether the individual in question is worthy of respect, then whether the event is worth remembering, and only after that whether the calligraphy merits imitation. If none of these qualities are present, then age alone does not make the inscription worthy of respect

好古者先當以其人之可尊,次當以其事之可傳,又其次始以其字之可法耳,三者咸無焉,雖古不足貴也。.

At most, it may serve as a vehicle for expressing one’s feelings. Yet even those who devote themselves to its study must remain aware of this limitation

愚以為書學之工,亦小道耳,誠不必畱意於此,要當寓意以適情興,志於臨池之學者又當知之。.

Emperor Huizong ruled at a time when the state was prosperous and the military strong, yet he gave himself over completely to extravagant pleasures, which only intensified over time. In the end, he brought disgrace upon himself, lost his empire without showing any remorse, and died in the northern deserts. In my view, this was a fitting outcome. Therefore, I have included it here as a warning to future rulers about the dangers of excessive luxury and uncontrolled desire

徽宗當國富兵強之時,肆窮極侈靡之欲,日增月盛,以致辱身喪國而不知悔,其死朔漠也宜矣。吾故索聯書於此,以為後世人主窮奢極欲者戒。.

4. Consolidating Scholar-Official Community: Network, Identity, and Confucian Solidarity in XZGGYL

4.1. Asserting Confucian Orthodoxy: Scholar-Officials and Moral Authority in the Mid-Ming Crisis

4.2. Networks and Distinctions: Scholar-Official Solidarity in Connoisseurial Practice

The examinations had effects other than turning out bureaucrats. They put young scholars into contact with others of the same social background and ambition at ever higher levels all over the country. Sitting for the provincial exam involved more than the isolating exercise of mastering a common body of knowledge, showing up, writing your answers in your sealed cell, and then going home. It was a highly social experience that involved sharing accommodations with other aspirants often for weeks at a time, eating and drinking together, sometimes forging deep bonds. If you passed, those who passed with you became your cohort with whom you could expect to associate, and for whom you could be called upon to do favors, for the rest of your life.

“A literatus, am I? The principles of Heaven and Earth remain elusive—yet I strive to exhaust them and bring them into form. Do I truly belong among the literati?”

吾文人乎哉?天地之理,欲窮之而未盡,欲凝之而未成也。吾文人乎哉?.

Few Confucians refrain from writing poetry. Yet among them, there are clear gradations: the most esteemed are those devoted to moral cultivation, while those who merely recite literary compositions were referred to by our predecessors as vulgar Confucians

儒者鮮不作詩。然儒之品有高下。高者,道德之儒;若記誦詞章,前輩君子謂之俗儒。.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| XZGGYL | Xinzeng Gegu yaolun 新增格古要論 Expanded Essential Criteria of Antiquities |

| GGYL | Gegu yaolun 格古要論 Essential Criteria of Antiquities |

| 1 | Wu Mingdi and Chang Naiqing studied the art market in Beijing during the Ming Dynasty (Wu and Chang 2022, pp. 115–19). Clunas also studied the art of regional aristocracy across the Ming Empire (Clunas 2013). Whether referring to the art market in Beijing (which was, in fact, closely linked to Jiangnan) or to princely collections, both were closely tied to imperial patronage. This paper, however, focuses on scholar-officials who were not directly influenced by imperial will and maintained a certain distance from Jiangnan. |

| 2 | GGYL used in this study is the early Ming edition previously collected by Sir Percival David and currently housed at the SOAS Library, University of London. This edition was also appended to Sir Percival’s work Chinese Connoisseurship (David 1971, pp. 295–344). |

| 3 | Recent studies have predominantly concentrated on GGYL due to its exceptional significance in Chinese art history, while XZGGYL has often been treated as a secondary topic. The relationship between these two texts—including both their continuities and divergences—has been explored by several scholars. Meng offers a comparative synthesis of GGYL and XZGGYL (Meng 2006b, pp. 81–94), whereas Zhu examines the textual lineage and transmission history of the two editions (Zhu 2006, pp. 81–88). Huang further investigates how the evaluative standards applied to objects shifted between the original and expanded editions (Huang 2020, pp. 69–70). Unless otherwise indicated, all citations from XZGGYL refer to the modern edition published by Zhejiang People’s Fine Arts Publishing House in 2019. This edition is based on the Xiyin xuan congshu edition 惜陰軒叢書本 as its base and is collated with: (1) the Ming edition by Zheng Pu 鄭朴刻本 reproduced in Xuxiu siku quanshu 續修四庫全書 and (2) the 1462 Xu shi shande shutang edition 天順六年徐氏善德書堂本, as recorded in Congshu Jicheng chubian 叢書集成初編. |

| 4 | Chu’s work on the intellectual history of the fifteenth century is foundational and provides crucial historical and ideological context for this study. Following the Tumu Crisis—during which Emperor Yingzong of Ming was captured and the empire confronted a direct Mongol threat—the scholar-official class underwent a profound intellectual transformation. Many began to question the efficacy of Cheng-Zhu Neo-Confucianism in state governance and sought alternative solutions. As Chu observes, some turned to the “cultivation of mind,” emphasizing the supremacy of mind, while others turned to the “learning of statecraft,” advocating the pursuit of practical and administratively relevant knowledge (Chu 1989, pp. 1–33). In addition to Chu, Bol also regards the Tumu Crisis as a significant historical juncture. In its aftermath, certain scholars began to question the foundational assumptions of Neo-Confucianism—such as the notion of equal moral potential in all individuals. They turned instead to pursuits that could be carried out independently yet still bore social and ethical significance (Bol 2008, pp. 97–98). |

| 5 | Li Zhuang is the son of the former Marquis Luanchen Li Jian 李堅 (d. 1401), who was married to Princess Da-ming 大名公主 (1368–1426), a daughter of the first Ming Emperor Zhu Yuanzhang. Li Zhuang, who was only seven years old when Li Jian passed away, succeeded as Marquis (David 1971, p. 7). Wang also noted in the section of “Colophon on the Yu Zhen Orchid Pavilion Preface” 跋玉枕蘭亭序 that he “recently saw this in Li Zhuang’s house in Nanjing” 近在南京李莊家見之, referring to the same person (Wang 2019, p. 48). |

| 6 | XZGGYL records a wide range of objects appreciated by Wang, including guqins 古琴 (e.g., Liezi style ancient guqin 列子樣古琴, guqin table made by Guogong brick 郭公磚琴卓), ancient paper (e.g., Goryeo paper 高麗紙), stele calligraphy tablets (e.g., Colophon on the Yu Zhen Orchid Pavilion Preface 玉枕蘭亭帖, stone original Shiqi tie 石本十七帖, Linjiang xiyutang Calligraphy 臨江戲魚堂帖, Ode to the Confucius hand-planted cypress 孔子手植檜讚, Mencius statue tablet 孟子像碑, statues for emperors and sages 帝王聖賢將相像), paintings (e.g., dragon painted by Chen Suoweng 陳所翁 [fl. 12th c.], colored landscape painting by Qian Xuan 錢選 [1239–1301]), precious objects (e.g., round jade agate crystal 園塊玉瑪瑙水晶, crane top red 鶴頂紅, the full-color red gold 足色赤金), rare stones (e.g., Yong stone 永石, turtle pattern stone 龜紋石), ancient porcelain 古窯器 (e.g., Dashi ware 大食窯), and ancient brocade canopies 古錦帳 (Wang 2019, pp. 10, 11, 14–15, 48, 56, 58–59, 85, 86–87, 112–23, 188, 191, 200, 210–11, 211–12, 240, 244, 250–51, 260). |

| 7 | Further evidence appears in Gazetteer of Ji’an Prefecture 吉安府志, Wang Zuo’s birthplace, compiled in the thirteenth year of the Wanli reign (1585), which contains the following entry:

|

| 8 | Wang Zuo witnessed both the flourishing and the subsequent decline of the Jiangxi scholar-official group during the mid- to early-late Ming period. As Dardess notes in his study of Taihe County in Jiangxi, the 1457 Coup—commonly known as the “Restoration of Nangong”—marked the end of Taihe natives’ half-century dominance over the Ming central government. As a native of Jishui, a neighboring county of Taihe, Wang Zuo was part of this broader Jiangxi official network. Wang’s regional identity also shaped his intellectual production. In XZGGYL, he frequently cites the writings of Jiangxi scholars, highlights the superior quality of Jiangxi-produced objects, and regularly documents connoisseurial exchanges with other officials originally from Jiangxi. Due to limitations of space and scope, a detailed discussion of this aspect will be pursued in another paper. For a case study of the Jiangxi official cohort during the Ming dynasty, see Dardess’s analysis of Taihe County (Dardess 1996, pp. 179–95). |

| 9 | The original stele is preserved at the Jianshui Confucian Temple in the Honghe Autonomous Prefecture of Yunnan Province. Yunnan University Anthropology Museum holds a rubbing of the stele. The image and text can be found in the seventh exhibit of the exhibition: https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s?__biz=MzIzMTU1NjM0Mg==&mid=2247488102&idx=1&sn=c6949e44592a27bb2cca891a679a1e5c&chksm=e8a307ffdfd48ee90b82bfd0061911c0ad7d56a81c6b1137d744f68a7a9a2f0093c00e90ffa4&scene=27 (accessed on 10 May 2025). |

| 10 | The original stele is preserved at the Hexi Confucian Temple in Tonghai County, Yuxi City, Yunnan Province. The Tonghai County Museum holds a rubbing of the stele. The image and text of the rubbing can be found here: https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s?__biz=MzIzMTU1NjM0Mg==&mid=2247486663&idx=1&sn=9bdefb7e43ba2efa301b60077f5972e2&chksm=e8a3195edfd490484206f28bcd2aeb99121d88eaa5bf40c4fac7958b6c87681815f5baf411ab&scene=27 (accessed on 10 May 2025). |

| 11 | The earliest extant edition of XZGGYL is published by the Xu shi shande shutang 徐氏善得書堂 in 1462. Sir Percival David argues that Wang Zuo had passed away prior to the publication of this edition, estimating his death between 1459 and 1462, and provides three supporting reasons for this claim (David 1971, pp. lv–lvi). However, the Jianshui inscription suggests that Wang Zuo was still alive in 1462 and remained active in local public affairs. |

| 12 | According to the author’s statistics, Wang Zuo consulted more than thirty works, including standard histories such as Jinshu 晉書 (Book of Jin) and Songshi 宋史 (History of Song); anecdotal and miscellany collections such as Rongzhai sibi 容齋四筆 (Essays from the Rong Studio), Youyang zazu 酉陽雜俎 (Miscellaneous Morsels from Youyang), Tieweishan congtan 鐵圍山叢談 (Collected Discussions from Mount Iron Enclosure), and Nanbu xinshu 南部新書 (New Book of the Southern Division); encyclopedic compendia such as Shilin guangji 事林廣記 (Vast Record of Varied Matters) and Jujia biyong shilei quanji 居家必用事類全集 (Complete Classified Essentials for Household Use); connoisseurial texts such as Fashu yaolu 法書要錄 (Essential Records of Calligraphy), Shushi huiyao 書史會要 (Essential Compendium of Calligraphy History), and Lidai zhongding yiqi kuanzhi fatie beiben 歷代鐘鼎彝器款識法帖碑本 (Model Inscriptions and Rubbings of Ritual Bronzes from Successive Dynasties); object-specific treatises such as Yanpu 硯譜 (Inkstone Manual) and Zhupu 竹譜 (Bamboo Manual); geographical and gazetteer works such as Fangyu shenglan 方輿勝覽 (Survey of Scenic Places) and Guangxi fangyu 廣西方輿 (Topography of Guangxi); literary collections such as Ouyang gong waiji 歐陽公外集 (Supplementary Works of Master Ouyang); and technical or professional texts such as Tang zhilin 唐職林 (Bureaucratic Registry of the Tang) and Shizu qaquan 氏族大全 (Complete Genealogy of Surnames). |

| 13 | The table is compiled with reference to the 2019 edition of XZGGYL published by Zhejiang People’s Fine Arts Publishing House (Wang 2019). |

| 14 | This literary privileging and the relative devaluation of painting were prevalent among Ming intellectuals. According to Clunas, the realm of writing served as the primary source of cultural capital, and mastery of literary expression was fundamental to their identity. A junzi (gentleman) was expected to compose poetry, but there was no equivalent expectation for him to be skilled in painting (Clunas 2006, p. 164). |

| 15 | Zhu notes that historical writings on the Song dynasty in the fifteenth century often reflected a deep concern with political issues. Such texts frequently used past events as allegories or admonitions aimed at the Ming political situation (Chu 1989, p. 13). Wang Zuo’s addition of content related to Yue Fei’s resistance against the Jurchens in XZGGYL appears to follow the same rationale. |

| 16 | Meng has provided an overview for the political situation of the mid Ming dynasty. For more detailed study of the political history of the seven years following the Tumu Crisis, which constituted the Jingtai reign, see The Care-taker Emperor (de Heer 1986). |

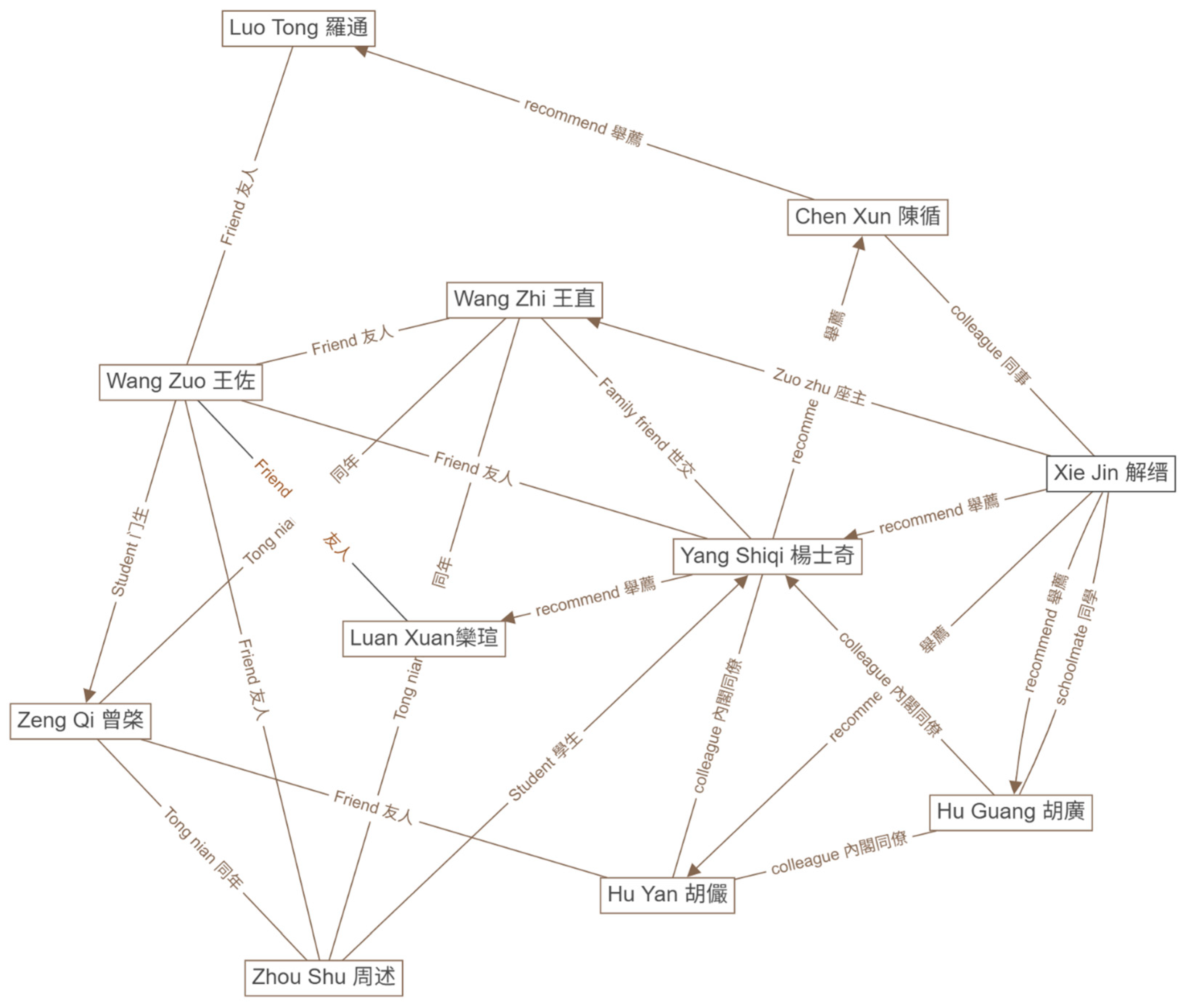

| 17 | Alongside connoisseurship manuals such as XZGGYL, pictorial works similarly functioned as instruments for articulating the social networks and shared identity of scholar-officials. Yin, in his study of the Xingyuan yaji tu 杏園雅集圖 (Elegant Gathering in the Apricot Garden), pointed out that this painting reveals the power of the Jiangxi scholar-official community led by Yang Shiqi. At this elegant gathering, nine officials participated, seven of whom were from Jiangxi: Yang Shiqi, Wang Zhi, Chen Xun 陳循 (1385–1462), Zhou Shu, Qian Xili 錢習禮 (1373–1461), Li Shimian 李時勉 (1374–1450), and Wang Ying 王英 (1376–1450). Except for Wang Ying, who was from Fuzhou 撫州, the other six were all from Ji’an prefecture. The painting functions much like a modern group portrait, capturing both the social occasion and the network of scholar-officials involved (Yin 2016, pp. 6–39). |

| 18 | All individuals represented in the diagram are referenced in XZGGYL. Some were contemporaries with whom Wang Zuo maintained documented personal or official ties; others appear solely as authors of essays excerpted and incorporated by Wang. With the exception of Luan Xuan, all figures in this diagram are natives of Jiangxi. Solid lines indicate peer relationships [e.g., colleagues or friends]. Single-directional arrows represent hierarchical relationships: the direction of the arrow points from the initiator to the receiver. For example, an arrow from Wang Zuo to Zeng Qi labeled “student” indicates that Wang Zuo was Zeng Qi’s student; an arrow from Yang Shiqi to Chen Xun labeled “recommendation” shows that Yang recommended Chen. The diagram was made by the author. |

References

- Bol, Peter K. 2008. Neo-Confucianism in History. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Asia Center. [Google Scholar]

- Brook, Timothy. 2010. The Troubled Empire: China in the Yuan and Ming. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Baoliang 陳寶良. 2001. Mingdai wenren bianxi 明代文人辨析 [Ming Literati Analysis]. Hanxue Yanjiu 漢學研究 19: 187–218. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Baoliang 陳寶良. 2016. Mingdai shidafu de jingshen shijie 明代士大夫的精神世界 [The Spiritual World of Ming Dynasty Scholar-Officials]. Beijing: Beijing shifan daxue chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, Hung-Lam. 1989. Intellectual Trends in the Fifteenth Century. Ming Studies 1: 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, Shen. 1979. Ming Antiquarianism: An Aesthetic Approach to Archaeology. Journal of Oriental Studies 8: 63–78. [Google Scholar]

- Clunas, Craig. 2004. Superfluous Things: Material Culture and Social Status in Early Modern China. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press. [Google Scholar]

- Clunas, Craig. 2006. Pictures and Visuality in Early Modern China. London: Reaktion Books. [Google Scholar]

- Clunas, Craig. 2013. Screen of Kings: Royal Art and Power in Ming China. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dardess, John W. 1996. A Ming Society: T’ai-ho County, Kiangsi, in the Fourteenth to Seventeenth Centuries. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- David, Percival. 1971. Chinese Connoisseurship: The Ko Ku Yao Lun. Essential Criteria of Antiquities. London: Faber and Faber Limited. [Google Scholar]

- de Heer, Ph. 1986. The Care-Taker Emperor: Aspects of the Imperial Institution in Fifteenth-Century China as Reflected in the Political History of the Reign of Chu Ch’i-yü. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, Shilong 鄧士龍, ed. 1993. Guochao dian’gu 國朝典故 [Anecdotes of the Present Dynasty]. Edited and Collated by Daling Xu 許大齡 and Tianyou Wang 王田有. Beijing: Beijing daxue chubanshe, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Du, Lianzhe 杜聯喆, ed. 1977. Mingren zizhuan wenchao 明人自傳文鈔 [Anthology of Ming Autobiographies]. Taipei: Yee Wen Publishing Co, Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Farmer, Edward L. 1995. Zhu Yuanzhang and Early Ming Legislation: The Reordering of Chinese Society Following the Era of Mongol Rule. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Haohua 胡昊華. 2018. Chonggou gegu yaolun: 12 dao 15 shiji zhongguo wenren jiancang zhong de quwei yu pindi 重構《格古要論》:12到15世紀中國文人鑒藏中的趣味與品第 [Reconstructing Essential Criteria of Antiquities: Hierarchy, Taste and Identity in 12th–15th Century China]. Ph.D. thesis, China Academy of Art, Hangzhou, China. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Dequan 黃德荃. 2020. Cong gegu yaolun xinzeng gegu yaolun kan mingdai pinwu zhifeng de fazhan liubian 從《格古要論》《新增格古要論》看明代品物之風的發展流變 [From Gegu yaolun to Xinzeng Gegu yaolun: The Changing Discourse of Object Appraisal in the Ming Dynasty]. Art Observation 美術觀察 8: 69–70. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Jingde 黎靖德, ed. 1986. Zhuzi Yulei 朱子語類 [Classified Conversations of Master Zhu]. Collated by Xingxian Wang 王星賢. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Wai-Yee. 1995. The Collector, the Connoisseur, and Late-Ming Sensibility. T’oung Pao 2: 269–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Yun 龍雲, and Zhongyue Zhou 周鍾岳. 1949. Xinzuan Yunnan Tongzhi 新纂雲南通志 [Newly Compiled General Gazetteer of Yunnan]. Kunming: Yunnan Renmin Qiye Gufen Youxian Gongsi, vol. 132. [Google Scholar]

- Lü, Dalin 呂大臨, Wang Qiu 王俅, Zhang Lun 張抡, Zhao Jiucheng 趙九成, and Zhu Derun 朱德潤. 2016. Kao gu tu (wai wu zhong) 考古圖(外五種) [Illustrated Investigations of Antiquity (and Five Other Works)]. Shanghai: Shanghai shudian chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Laiping 馬來平. 2019. Gewu zhizhi: Ruxue neibu shengzhang chulai de kexue yinzi 格物致知:儒學內部生長出來的科學因子 [Gewu zhizhi as an Indigenous Mode of Scientific Inquiry in Confucianism]. Wen Shi Zhe 文史哲 3: 87–97. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, Sen 孟森. 2006a. Mingshi jiangyi 明史講議 [Lectures on Ming History]. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, Yuanzhao 孟原召. 2006b. Caozhao gegu yaolun yu wangzuo xinzeng gegu yao lun de bijiao 曹昭《格古要論》與王佐《新增格古要論》的比較 [A Comparison between Cao Zhao’s Gegu yaolun and Wang Zuo’s Xinzeng gegu yaolun]. Palace Museum Journal 故宮博物院院刊 6: 81–94. [Google Scholar]

- Moser, Jeffrey. 2023. Nominal Things: Bronzes in the Making of Medieval China. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, Shengfang 彭聖芳. 2009. Cong gewu dao wanwu-mingdai qiwu jianshang de zhuanbian 從格物到玩物——明代器物鑒賞的轉變 [From Investigating Things to Appreciating Objects: The Transformation of Material Connoisseurship in the Ming Dynasty]. Art Exploration 藝術探索 5: 33–35. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, Jinchun 邱進春. 2007. Mingdai jiangxi jinshi kaozheng 明代江西進士考證 [A Study of Jinshi Degree Holders from Jiangxi during the Ming Dynasty]. Ph.D. thesis, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, Jun 丘濬. 1621. Chong xiu qiongtai shiwen huigao 重修瓊台詩文會稿 [Recompiled Anthology of Poetry and Prose Gatherings at Qiongtai]. Edition from the first year of the Tianqi reign 明天啟元年刊本. vol. 9. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, Jiyu 任繼愈. 2001. Zhuxi gewu shuo de lishi yiyi 朱熹格物說的歷史意義 [The Historical Significance of Zhu Xi’s Theory of Gewu]. Journal of Nanchang University (Humanities and Social Sciences) 南昌大學學報(人文社會科學版) 1: 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Van Gulik, Robert Hans. 1940. The Lore of the Chinese Lute. Tokyo: Sophia University. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Zhi 王直. 1991. Yan’an wenji 抑庵文集 [Collected Works of Yi’an]. Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Zuo 王佐. 2019. Xinzeng gegu yaolun 新增格古要論 [Expanded Essential Criteria of Antiquities]. Hangzhou: Zhejiang renmin meishu chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Mingdi 吳明娣, and Naiqing Chang 常乃青. 2022. Mingdai beijing yishu shichang de yangmao yu fanrong 明代北京藝術市場的樣貌與繁榮 [The Landscape and Flourishing of the Art Market in Ming-Dynasty Beijing]. Meishu 美術 1: 115–19. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, Jinan 尹吉男. 2016. Zhengzhi haishi yule: Xingyuan yaji he xingyuan yajitu xinjie 政治還是娛樂:杏園雅集和杏園雅集圖新解 [Politics or Entertainment: A New Interpretation of the Elegant Gathering in the Apricot Garden]. Palace Museum Journal 故宮博物院院刊 1: 6–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Zhizhen 余之禎, ed. 1989. Jiangxi sheng ji’an fushi 江西省吉安府志 [Gazetteer of Ji’an Prefecture, Jiangxi Province]. Taipei: Cheng Wen Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Tiexian 張鉄弦. 1962. Mingdai de wenwu jianshang shu gegu yaolun 明代的文物鑒賞書《格古要論》 [The Ming Dynasty Connoisseurship Book Gegu yaolun]. Wenwu 文物 1: 43–48. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Xihu 趙希鹄, and Jixu Chen 陳繼儒. 2016. Dongtian qinglu (wai er zhong) 洞天清錄(外二種) [Record of the Pure Registers of the Cavern Heaven (and Two Other Texts)]. Hangzhou: Zhejiang Renmin Meishu Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Xi 朱熹. 1983. Sishu jizhu zhangju 四書集注章句 [Collected Commentaries on the Four Books]. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Zhongyue 朱仲岳. 2006. Guge yaolun banben bianxi 《格古要論》版本辨析 [An Analysis of the editions of Gegu yaolun]. Journal of National Museum of China 中國歷史文物 1: 81–88. [Google Scholar]

| Chapter | Part | xin zeng | hou zeng | xin zeng and hou zeng | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chapter 1 | Ancient zithers Guqin 古琴論 | 6 | 2 | 8 | 14 |

| Chapter 2 | Ancient calligraphy(A) 古墨蹟論(上) | 0 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| Ancient tablets and rubbings 古碑法帖 | 20 | 1 | 21 | 22 | |

| Chapter 3 | Ancient calligraphy(B) 古墨蹟論(下) | 14 | 7 | 21 | 33 |

| The stones tablets of Shaanxi 新增陝西碑帖 | 35 | 0 | 35 | 35 | |

| Tablets in various places 新增各地碑帖 | 154 | 0 | 154 | 154 | |

| Chapter 4 | Inscription on metal and stone 金石遺文 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| Essay of the Song dynatsy 宋金石遺文 | 15 | 0 | 15 | 15 | |

| Colophons on rubbings 法帖題跋 | 30 | 0 | 30 | 30 | |

| Chapter 5 | Ancient painting 古畫論 | 20 | 13 | 33 | 48 |

| Chapter 6 | Precious objects 珍寶論 | 2 | 8 | 10 | 48 |

| Ancient bronzes 古銅論 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 8 | |

| Chapter 7 | Ancient ink-stines 古硯論 | 6 | 0 | 6 | 19 |

| Rare stones 異石論 | 3 | 5 | 8 | 21 | |

| Ancient porcelain 古窯器 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 17 | |

| Chapter 8 | Ancient lacquer 古漆器 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 6 |

| Ancient textles 古錦論 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 10 | |

| Rare woods 異木論 | 5 | 9 | 14 | 19 | |

| Bamboo 竹論 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | |

| Chapter 9 | Studio objects 文房論 | 27 | 0 | 27 | 27 |

| Chapter 10 | Epilogues to imperial patents 古今誥敕題跋 | 30 | 0 | 30 | 30 |

| Chapter 11 | Miscellaneous(A) 雜考(上) | 7 | 0 | 7 | 7 |

| Chapter 12 | Miscellaneous(B) 雜考(中) | 9 | 0 | 9 | 9 |

| Chapter 13 | Miscellaneous(C) 雜考(下) | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Account of the palaces of Song dynasty 宋宮殿記 | 10 | 0 | 10 | 10 | |

| Total | 399 | 55 | 454 | 594 | |

| Proportion | 67.17% | 9.26% | 76.43% | 100% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, Z.; Wang, H. Recasting Antiquarianism as Confucian Orthodoxy: Wang Zuo’s Expanded Essential Criteria of Antiquities and the Moral Reinscription of Material Culture in the Ming Dynasty. Religions 2025, 16, 778. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16060778

Chen Z, Wang H. Recasting Antiquarianism as Confucian Orthodoxy: Wang Zuo’s Expanded Essential Criteria of Antiquities and the Moral Reinscription of Material Culture in the Ming Dynasty. Religions. 2025; 16(6):778. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16060778

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Ziming, and Hanwei Wang. 2025. "Recasting Antiquarianism as Confucian Orthodoxy: Wang Zuo’s Expanded Essential Criteria of Antiquities and the Moral Reinscription of Material Culture in the Ming Dynasty" Religions 16, no. 6: 778. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16060778

APA StyleChen, Z., & Wang, H. (2025). Recasting Antiquarianism as Confucian Orthodoxy: Wang Zuo’s Expanded Essential Criteria of Antiquities and the Moral Reinscription of Material Culture in the Ming Dynasty. Religions, 16(6), 778. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16060778