1. Introduction

The Guyang Cave 古陽洞 is located in the southern part of the Longmen 龍門 Grottoes West Hill in Luoyang City, Henan Province, China. Its initial excavation started around the time when Emperor Xiaowen 孝文 of the Northern Wei Dynasty (386–534) relocated the capital to Luoyang (494), making it one of the earliest caves excavated at the Longmen Grottoes. The Guyang Cave’s structure is relatively regular, shaped like a horseshoe, with a domed ceiling. The cave’s back wall (west wall) features a large statue, while the side walls are densely covered with niches containing smaller statues (

Figure 1). The cave measures 11.2 m in height, 6.9 m in width, and 13.7 m in depth. The main statue on the back wall is 6.15 m tall and the base on which it sits stands 4.8 m tall (

Liu 2001, vol. 1, introduction p. 1).

In the cave, a distinctive artistic configuration emerged during the late Northern Wei period—the statue–stele combination. This innovative arrangement features a niched Buddhist sculpture paired with an adjacent inscribed stele, where the epigraphic text serves as the patron’s votive dedication. These integrated compositions embody multiple layers of significance through their dynamic interplay. Stylistically, the visual relationship between statue and stele manifests in two contrasting modes: at times achieving harmonious balance to collectively engage the viewer’s gaze, while in other instances establishing hierarchical dominance where one element supersedes the other in visual prominence. Iconographically, these dual components demonstrate both complementary and dialectical functions. They may operate in mutual reinforcement to propagate Buddhist doctrines, or alternatively maintain relative opposition, each advancing distinct ideological narratives. From the perspective of religious patronage, the commissioners’ motivations often revealed multifaceted complexity that neither medium could singularly express. The strategic combination, however, not only enabled the fulfillment of their respective ritual and commemorative functions but also generated a synergistic amplification of devotional efficacy. This artistic synthesis thus transcended mere physical juxtaposition to create profound semiotic resonance within the sacred space.

This study initiates with a stylistic analysis on these statue–stele combinations. The investigation subsequently demonstrates how artistic styles are embedded within the spatial framework of the cave temple. This spatial configuration, in turn, was shaped by the collaborative yet competitive dynamics among patrons, each driven by distinct religious and ritual objectives. However, it would be reductive to assert that ritual requirements solely dictated stylistic choices or directly generated artistic production. Instead, both artistic expression and ritual practice emerge as mutually constitutive elements within the broader process of religious and cultural formation.

3. The Style Groups

Approximately ten well-preserved steles with largely intact inscriptions survive in the Guyang Cave.

2 This paper focuses on these ten steles and their accompanying niched statues, dividing them into three groups based on stylistic characteristics (

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5).

The first group comprises four cases. Case 1 was commissioned by Monk Huicheng 慧成 for his late father, the Duke of Shiping 始平公. The stele head bears the inscription “shiping gong xiang yiqu 始平公像一軀” (One Statuary Image for the Duke of Shiping) (

Figure 6) (

Liu 2001, vol. 1, p. 74, niche no. N304, pl. 110, vol. 3, p. 55, inscription no. 1842). Case 2’s inscription records its commission by Sun Qiusheng (孫秋生) and members of his yi-group. The stele head reads “yizi xiang 邑子像” (Image for the Yi-Group Members) (

Figure 7) (

Liu 2001, vol. 1, p. 148, niche no. S106, pl. 226, vol. 3, p. 78, inscription no. 2296). Case 3 features the inscribed title “shijia xiang 釋迦像” (Shakyamuni Image), alongside the names of chief commissioners Wei Lingzang 魏靈藏 and Xue Fashao 薛法韶 (

Liu 2001, vol. 1, p. 70, niche no. N234, vol. 3, p. 66, inscription no. 2024). Case 4 displays the title “yizi xiang” with the commissioner’s name, Yan Dayan 楊大眼, in the inscription (

Figure 8 and

Figure 9) (

Liu 2001, vol. 1, p. 63, niche no. N228, pl. 87, vol. 3, p. 66, inscription no. 2023).

Within this group, all niched statues depict Shakyamuni seated cross-legged in meditation mudra. The steles are distinctly projecting from the cave wall, with their bases protruding even more substantially. Below each statue, carvings show an incense burner flanked by worshippers.

Beyond these shared stylistic features, stronger textual and visual connections emerge among group members. For instance, both the Wei Lingzang-Xue Fashao and Yang Dayan inscriptions contain the phrase “as for everyone’s appearance, there is none left underrepresented 凡及眾形, 罔不備列.” This refers to the nearly identical figural arrangements of devotees listening to the Buddha in both niches (

Figure 8 and

Figure 9).

3 Furthermore, all four cases occupy the lowest level of the Guyang Cave from its initial excavation phase, belonging to the so-called “Eight Great Niches”

4.

The second group consists of two cases. Case 5’s stele bears no title on its head, but the inscription identifies Lady Yuchi 尉遲 as the commissioner, who dedicated it to her deceased son Niu Jue 牛橛 (

Liu 2001, vol. 1, p. 50, niche no. N94, pl. 65, vol. 3, p. 55, inscription no. 1840). Similarly, Case 6’s stele lacks a title, with its inscription naming Yuan Xiang 元詳 as the patron (

Figure 10) (

Liu 2001, vol. 1, p. 48, niche no. N51, pl. 63, vol. 3, p. 55, inscription no. 1843). The text further notes Yuan Xiang’s former position as “Beihai wang 北海王” (The Prince of Beihai).

Both niches feature Maitreya in a cross-legged posture. Stylistically, this group shows significant differences from the first. The steles exhibit markedly reduced three-dimensionality, and therefore the distinction between steles and cave wall becomes less pronounced. The bases appear particularly flattened, yet display rich imagery. Positioned one level above the “Eight Great Niches,” these cases occupy a transitional zone where the vertical wall begins curving into the arched ceiling.

The third group comprises four cases. Case 7’s untitled stele bears a brief inscription naming its commissioner: “Guangchuan wang zumu taifei Hou 廣川王祖母太妃侯” (Grand Consort Hou, grandmother of the Prince of Guangchuan) (

Figure 11) (

Liu 2001, vol. 1, p. 196, niche no. D87, pl. 312, vol. 3, p. 76, inscription no. 2272). Case 8 features the title “yizi xiang” and mentions yi-group member Wei Taoshu 魏桃樹 in its inscription (

Liu 2001, vol. 1, p. 43, niche no. N85, pl. 56, vol. 3, p. 68, inscription no. 2067). Case 9’s untitled stele records its commission by Yin Aijiang 尹愛姜 and her yi-group members (

Liu 2001, vol. 1, p. 197, niche no. D89, pl. 313, vol. 3, p. 76, inscription no. 2271). Case 10 displays the title “yizi xiang” and names patron Ma Zhenbai 馬振拜 (

Liu 2001, vol. 1, p. 192, niche no. D71, pl. 307, vol. 3, p. 90, inscription no. 2521).

All statues depict Maitreya cross-legged. This group demonstrates further stylistic differences. The steles appear flatter than Group 2’s, nearly recessed into the wall. Execution of both the statues and stele appears cruder overall. Except for Case 7, most follow formulaic designs rather than unique visual programs. No subsidiary images appear below niches or steles. Most carvings in the group are located on the cave ceiling.

Please see

Table 1 for a summary of the stylistic analysis. It also contains the dating information and spatial context of each group.

4. The Guyang Steles: Case Studies

This section examines four selected steles from the three groups for close analysis. These cases were chosen for their exemplary demonstration of group-defining characteristics in style, spatial positioning, and ritual function. Their juxtaposition further reveals how patrons negotiated spatial and visual hierarchies within Guyang Cave’s crowded environment.

The first case examines Huicheng’s stele dedicated to the Duke of Shiping, exemplifying the “high-relief” approach. Rather than functioning as a mere inscribed surface, the stone has been sculpturally transformed into a three-dimensional image. This contrasts with yet complements the second case from the same group, Sun Qiusheng’s stele, which employs a “deep-carving” technique. Where Huicheng’s work projects outward from the stone surface, Sun Qiusheng’s recedes into the cave wall—yet both emphasize the stelae’s physical materiality. This shared emphasis responds to their low positioning in the cave, creating an intimate viewing dynamic that defines Group 1’s tactile aesthetic.

Yuan Xiang’s commission represents Group 2’s innovative synthesis of stele and image as ritual artifacts. Here, the carving process itself becomes performative, with the finished work crystallizing ritual moments onto the stone surface. Significantly, this group elevates its position on the cave wall while simultaneously lowering its visual focal point—the ceremonial images extend downward to merge with the statue’s base. This vertical integration marks Group 2’s distinctive spatial strategy.

The Group 3 example, Grand Consort Hou’s year-502 stele, demonstrates adaptive originality despite the group’s generally crude execution. Its exceptionally large characters—necessitated by its ceiling placement—reveal a sophisticated awareness of distant viewers. Notably, among Group 3’s typically isolated carvings, Hou’s stele uniquely maintains visual dialogue with patron competitions occurring at lower levels, reconnecting the ceiling space with the cave’s broader ritual landscape.

Each case study embodies a distinct system of ritual significance. Take Huicheng as an example: as a monastic practitioner, his act of image-making primarily manifested devotion to the Buddha. Yet by supplementing the sculpture with a stele bearing an inscription explicitly commemorating his deceased father, he skillfully integrated Buddhist devotional practice with Confucian filial rites within a single visual medium.

This personal memorial approach stands in sharp contrast to Sun Qiusheng’s stele, which employs a materially imposing framework to record a patronage list of two hundred names—constituting physical testimony to a grand collective dedicatory ceremony. Yuan Xiang’s sculptural project similarly demonstrates this collective ritual dimension, where the stone carving not only documents but materially constitutes the ritual performance itself, though with greater emphasis on visual amplification of ceremonial impact.

The visual impact of Grand Consort Hou’s stele lies in its inscription. The exceptionally large characters create its most striking visual feature when viewed from ground level. Significantly, her choice of the stele format suggests intrinsic connections among multiple steles in Guyang Cave as ritual art objects. Within this sacred space, the patron community engaged simultaneously in visual competition and ritual cooperation. Through ongoing negotiations adjusting the relationship between steles and statues, they collectively shaped the cave’s overall iconographic program while reconciling individual aspirations. This dynamic formative process reveals not only religious piety but also mutual recognition and respect among the patrons themselves.

4.1. Stele in High Relief: The Play of Light and Shadow at the Cave Entrance

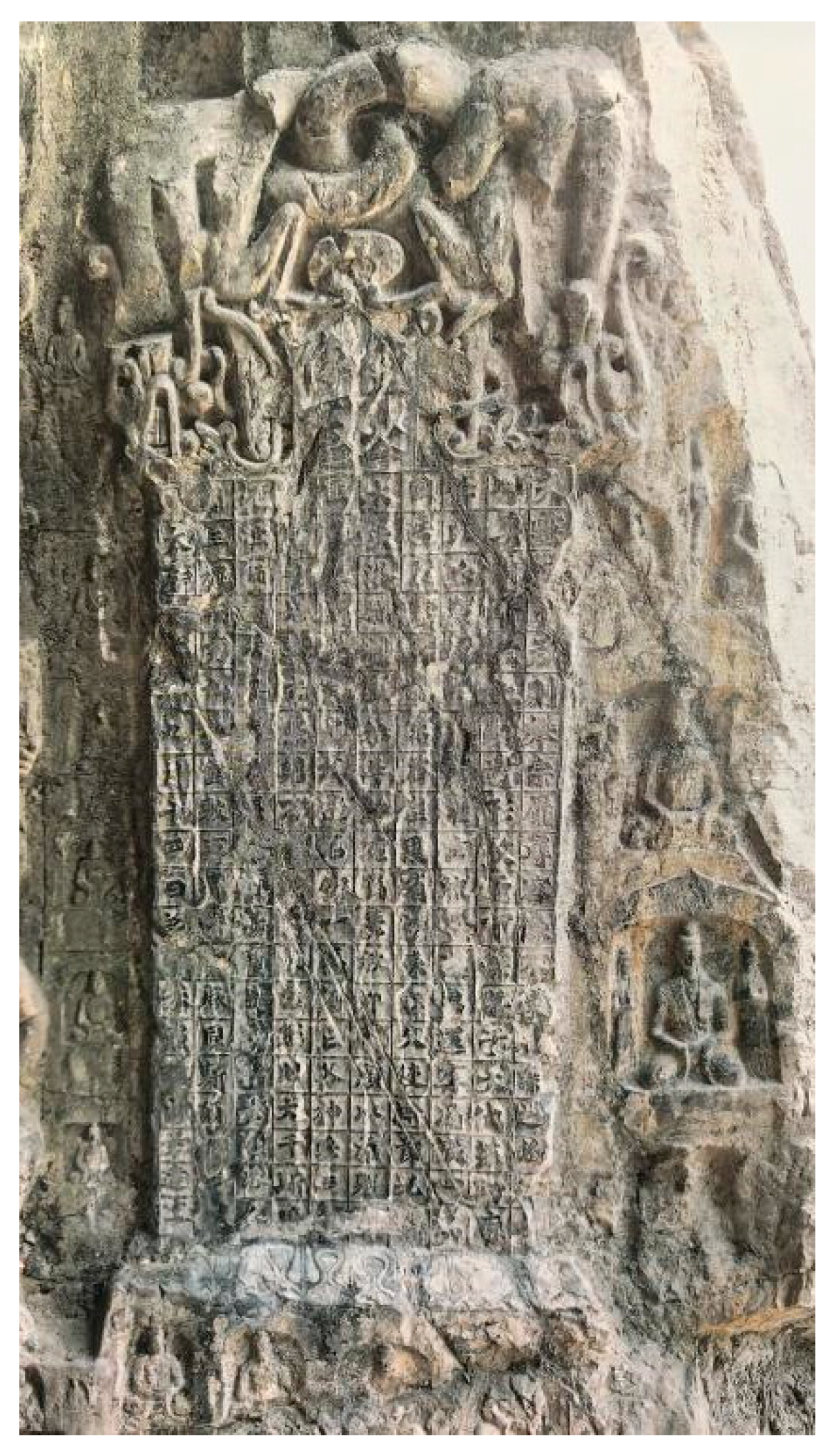

Huicheng’s carving occupies the northernmost position on the cave’s northern wall, forming one of the celebrated “Eight Great Niches.” As seen in

Figure 12, the stele is situated adjacent to the edge of Guyang Cave, where natural light filters in. The central figure is a cross-legged Shakyamuni Buddha in meditation posture (dhyana mudra). Below the statue, an incense burner, entwined by a pair of sinuous dragons, is flanked on either side by two worshippers in reverent poses. The surrounding cave wall has been meticulously recessed, enhancing the stele’s three-dimensional prominence. The stele’s crown features an intricately carved pair of intertwined dragons (

Wong 2004, p. 63),

5 their dynamic forms rendered in such high relief that they constitute a sculptural masterpiece. Below the dragons, a pointed plaque bears the inscription’s title, while the lower section consists of a protruding base adorned with floral motifs and four small niche statues. This composition exemplifies the late Northern Wei period’s sophisticated integration of sculpture, epigraphy, and architectural space, where technical virtuosity and religious symbolism converge.

Stylistically, this stele differs markedly from traditional Chinese steles dating back to the Han dynasty. Unlike conventional examples, its double-dragon crown, main body, and even the inscribed text are all executed in pronounced high relief (

Figure 12). Hyun-Sook Jung Lee addresses this distinctive feature in her doctoral dissertation, suggesting a potential connection between Huicheng’s stele and earlier or contemporaneous tomb epitaph stones (

Lee 2005, p. 304). While Lee does not explore this hypothesis in depth, its significance lies in highlighting an important parallel: the use of high-relief carving—relatively uncommon in most stele traditions—appears with greater frequency in funerary contexts, particularly on the lids of stone epitaphs.

Liu (

2002, p. 444) observes that Northern Dynasty stone epitaph lids feature a distinctive calligraphic style termed ‘bird seal script’ (niaozhuan), noting “These inscriptions predominantly employ subtly raised lines, with certain examples approximating low-relief carving techniques”. Of particular significance is Liu’s emphasis on the highly ornamental character of Northern Dynasty epitaph inscriptions, for which bird seal script serves as a paradigmatic case. He specifically references the epitaph lid of Yu Jing (dated 526), whose inscription demonstrates three characteristic features: (1) substantial stroke weight, (2) compressed character forms, and (3) meticulously rendered avian motifs—with delicate bird heads and tails adorning the terminals of principal strokes. This combination creates a striking visual effect marked by both decorative opulence and intricate complexity (

Liu 2002, pp. 443–44, Figure 12-4.15.).

Liu Tao’s important analysis illuminates the distinctive role of seal script in post-Han Chinese calligraphic history: it persisted primarily as a decorative script imbued with ritual significance. Following the displacement of seal script by clerical script as the standard writing form, its application in Han dynasty steles became largely restricted to the headings—where the main text would employ the contemporary popular script while titles retained the archaic form. This deliberate differentiation underscores the hierarchical ritual status accorded to different scripts.

Seal script’s formal qualities—its more geometric strokes, denser character structures, and inherently labor-intensive execution—rendered it particularly suitable for ceremonial contexts. In

Wu’s (

1996, pp. 1–15) theoretical framework, these characteristics endowed seal script inscriptions with heightened monumentality. When Huicheng sought to amplify this monumentality for artistic or ritual purposes (which will be examined in detail subsequently) and was willing to bear the substantial production costs, he may have deliberately extended the high-relief technique—traditionally limited to stele headings or epitaph lids—to the entire stele surface. Consequently, Huicheng’s stele transcends mere textual function to become a sculptural relief, effectively transforming writing into a three-dimensional artistic medium (

Wu 1994, pp. 58–86).

6Regarding the transformation of inscribed characters into raised-relief imagery, Gong Dazhong proposes an insightful hypothesis (

Gong 2002, p. 214). His analysis highlights that Huicheng’s niche statue and stele exhibit stylistic characteristics predating other works among the Eight Great Niches. Significantly, Gong identifies a striking stylistic parallel between these carvings and a high-relief apsara located near the small window above the entrance of Yungang Grottoes’ Cave 9. This visual correlation leads him to postulate that artisans previously employed at Yungang may have introduced this distinctive high-relief technique to the Guyang Cave workshop. Gong further contends that these craftsmen not only systematically adapted the style for the niche sculpture but extended its application to the accompanying stele as well, thereby creating a unified aesthetic program that blurred traditional boundaries between sculpted words and images.

While direct evidence to substantiate Gong Dazhong’s hypothesis may be limited, its scholarly significance remains undiminished. The late Northern Wei artisans working in the Guyang Cave primarily engaged in three fundamental techniques: (1) excavating the stone surface, (2) creating relief carvings, and (3) employing linear delineation to define forms. Their artistic focus appears to have centered on these technical processes rather than on whether the resulting play of light and shadow specifically constituted written characters or divine imagery. This interpretation finds indirect support in the frequent occurrence of orthographic errors and variant characters in Northern Dynasty religious inscriptions, suggesting that textual accuracy was often subordinate to visual and spatial considerations in these sculptural programs.

This ambiguity challenges any definitive distinction between “reading” and “viewing” a stele. Rather, these two modes of engagement appear to operate concurrently. When observed from a distance, where the textual content dominates our cognitive processing, we assume the role of readers. However, upon closer inspection, the material construction of the stele asserts itself—the demarcating grids that project the stele from the wall surface, the calligraphic strokes contained within these grids, and the sinuous contours of the intertwined dragons crowning the stele all begin to visually coalesce. This perceptual blending of structural, textual, and decorative lines transforms Huicheng’s commission from a functional stele into a meta-representation of the stele form itself. As our attention shifts to the rhythmic interplay of these linear elements, we transition from textual interpreters to visual spectators, engaging with the work primarily as an artistic image rather than an epigraphic document.

In addition, the stele’s strategic placement at the cave entrance serves to accentuate its linear elements through controlled illumination (

Figure 12). While the (possible) original eastern facade of the mountain and the man-made gate structure have not survived, we can reconstruct the intended visual effect: on sunny days with the gate opened, beams of sunlight would penetrate the cave’s darkness, dramatically illuminating the entrance area.

This hypothesized lighting scenario finds corroboration in the nearby Central Binyang Cave at Longmen Grottoes, a contemporaneous Northern Wei construction. The Central Binyang Cave features an important pair of high-relief sculptures flanking its entrance—the Emperor’s and Empress’s Processions to Worship the Buddha (

Figure 13). These figures demonstrate a sophisticated understanding of optical effects: while rendered predominantly in three-quarter profile, their noses project perpendicularly from the cave wall at exaggerated proportions. This deliberate formal distortion serves two crucial functions: first, it breaks the expected contour lines of the profiles, presenting the noses in frontal view to approaching visitors; second, these protruding elements catch the incoming sunlight, casting pronounced shadows across the faces that dramatically focus the viewer’s attention on the facial expressions and details. This careful manipulation of light and form in the Central Binyang reliefs provides compelling evidence for how Northern Wei artisans strategically employed architectural placement and sculptural technique to guide visual experience—a principle that likely informed the similar treatment of Huicheng’s stele at the Guyang Cave entrance.

Huicheng’s stele achieves remarkable visual impact through its masterful manipulation of light and shadow across each character and grid division. This innovative approach to stele design creates an immediate, tangible presence that profoundly engages viewers. For those familiar with traditional Chinese steles, the challenges of conventional inscriptions are well known: weathered surfaces, shallowly incised characters in delicate strokes, and the inevitable loss of original pigments that once enhanced legibility. Under typical viewing conditions—often in poor lighting—attempting to decipher hundreds of such faint, small characters can become an exercise in frustration. This explains the widespread preference for examining ink rubbings rather than the original steles.

Huicheng’s high-relief solution represents a radical departure from these limitations. By transforming the textual content into three-dimensional forms, the stele offers viewers dual aesthetic experiences: the intellectual satisfaction of readable content combined with the visual pleasure of calligraphic artistry. The pronounced relief ensures characters remain clearly visible even in suboptimal lighting, while the play of light across the sculpted strokes enhances appreciation of their calligraphic beauty. This harmonious integration of textual communication and visual artistry constitutes a unique achievement in the history of Chinese epigraphic art, providing an exceptionally accessible and aesthetically rewarding viewing experience.

4.2. Deep Carving: A Stele’s Presence as an Erected Stone

Sun Qiusheng and his fellow members of the yi-group commissioned a niche featuring a seated Shakyamuni Buddha, accompanied by an elaborate sculptural program. The composition includes an incense burner intricately carved with twin dragons in dynamic embrace, flanked symmetrically by pairs of worshippers (two figures on each side) in reverent poses. The accompanying stele exhibits three distinctive formal elements that reveal stylistic continuity with Case 1: (a) a pointed plaque positioned beneath the coiled dragon crown, (b) a proportionally exaggerated base that dramatically surpasses the height of the stele body proper, and (c) the overall integration of sculptural and epigraphic elements. These shared characteristics hint at the artistic dialogue between the two commissions within the cave’s decorative system.

However, a significant formal distinction emerges in Case 2 through the incorporation of two pronounced vertical grooves flanking the stele body (

Figure 7). These deep channels demarcate the stele’s boundaries, beyond which rise sculpted guardrails evoking riverbank effects. These guardrails exhibit three notable characteristics: (1) their surfaces are meticulously carved with intricate floral patterns, (2) they project more prominently than the central stele body, and (3) they function as physical and visual barriers separating the stele from adjacent carvings. This sophisticated treatment demonstrates the artisans’ acute awareness of the stele’s material presence, elevating it beyond mere textual support to become an autonomous sculptural entity within the cave’s artistic program. The deliberate emphasis on the stele’s physical form reflects a profound engagement with traditional Chinese stele aesthetics while introducing innovative spatial solutions.

Chinese steles are typically rectangular stone slabs erected vertically on the ground. For artisans working in the Guyang Cave, the challenge lay in adapting this conventional form to a vertical surface by mounting the stele directly onto the cave wall rather than placing it on the floor. This adaptation parallels the treatment of niched statues in the cave, which are essentially freestanding sculptures that have been conceptually ‘embedded’ into the wall through the preliminary excavation of cavities.

The same embedding principle applies to the steles. The two exceptionally deep grooves flanking the stele serve a crucial spatial function: they do not merely delineate the stele’s edges but actively carve out a virtual ‘niche’ for the stele within the wall. This innovative treatment achieves two important effects: (1) it heightens the stele’s three-dimensional presence by creating a distinct spatial frame, and (2) it transforms the stele from a flat inscribed surface into an independent sculptural entity with its own defined spatial boundaries. Through this solution, the artisans successfully translated the essential monumentality of ground-standing steles into a wall-mounted format while preserving the form’s traditional dignity and presence.

This enduring emphasis on the stele’s materiality can be traced to the widespread stele-erecting practices of the Eastern Han dynasty (

Zhao 2019, pp. 135–38). The inscription on Case 2’s stele exhibits a bipartite structure: the upper section contains a dedicatory text expressing the patrons’ aspirations for well-being in both present and future lives, while the lower portion comprises an extensive name list occupying approximately two-thirds of the surface area, recording nearly 200 patrons. As

Dorothy Wong (

2004, pp. 15–19) has demonstrated, these Northern Wei period “yiyi” (devotional) societies likely evolved from pre-Qin era “she” (社)—local communal organizations that similarly engaged in ritual stone erection. This connection finds further support in

Patricia Ebrey’s (

1980, p. 333) analysis of the Cao Quan Stele, which reveals that such lengthy patron lists were already conventional features on Han dynasty funerary monuments.

Collectively, these scholarly insights suggest that the patron list tradition embodied in Sun Qiusheng’s stele may have originated in pre-Qin “she” practices, been subsequently adapted in Han mortuary contexts, and ultimately transmitted to the Guyang Cave through these earlier epigraphic conventions. This lineage underscores the remarkable continuity of Chinese commemorative practices across different historical periods and religious contexts.

4.3. Images at the Base: The Crystallization of Ceremonial Moments

Yuan Xiang’s commission, Case 6, exhibits remarkable stylistic affinities with Case 5 (Lady Yuchi’s carvings), particularly in their shared iconographic program. Both compositions feature (1) a central seated Maitreya Buddha flanked by standing worshippers in symmetrical arrangement, and (2) an uninscribed, horizontally elongated pointed plaque crowning the stele. The formal similarities extend to the stele’s side grooves, which remain clearly visible in both cases. While physical evidence of the original stele base has been lost to time, its former presence can be reasonably inferred. Notably, at a level slightly below the presumed base position, within a narrow horizontal register beneath the accompanying niche, significant decorative elements have survived.

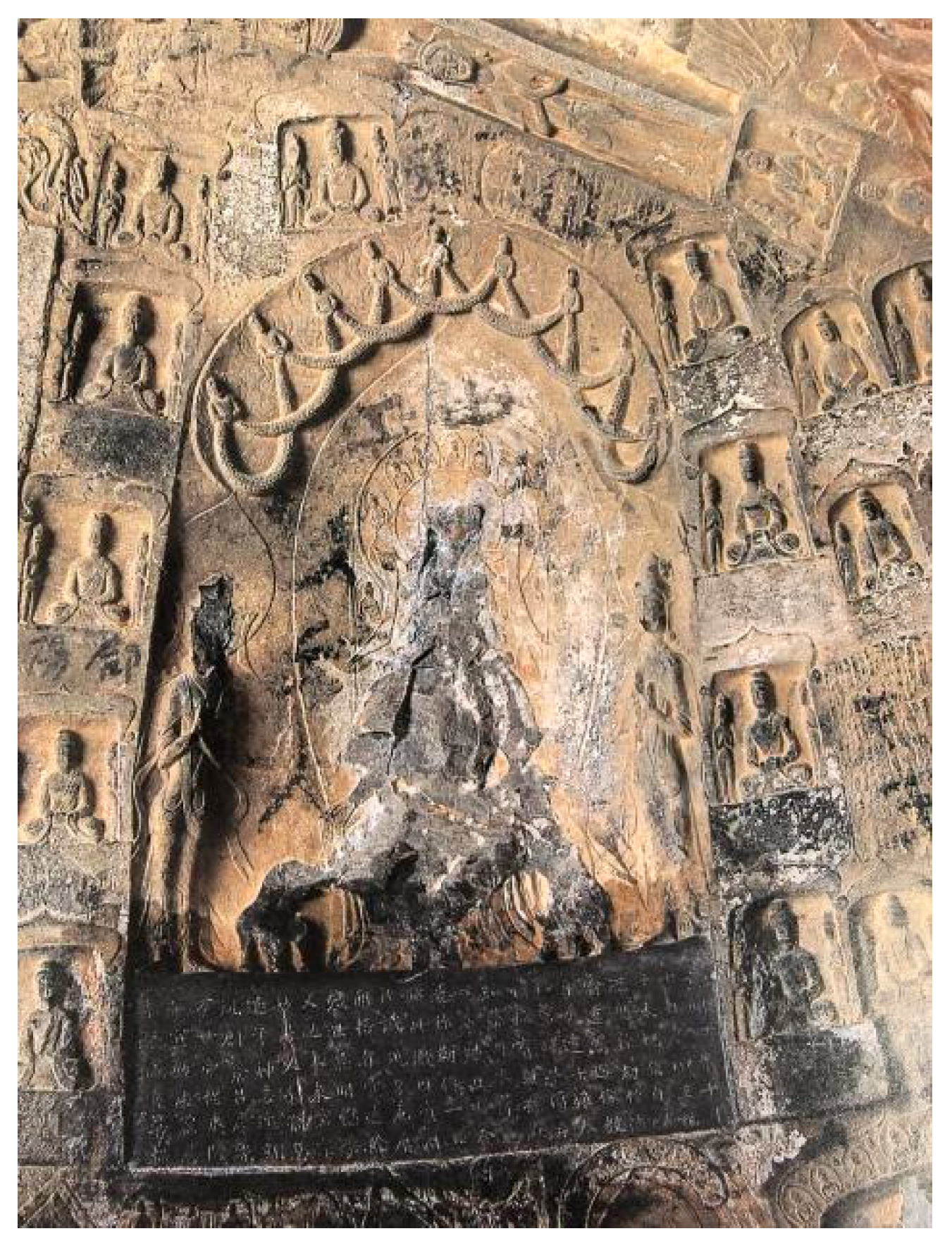

Beneath Yuan Xiang’s Maitreya statue in Case 6, the sculptural program features a distinctive bilateral procession motif—a unique configuration among the ten cases examined in this study (

Figure 14). This arrangement finds its closest parallel elsewhere in the Guyang Cave beneath the statue commissioned by Monk Fasheng on the south wall, another member of the Eight Great Niches (

Figure 15).

Kate Lingley’s (

2004) comprehensive research on Northern Wei votive processions demonstrates that such compositions were prevalent throughout Henan Province’s cave temples. Her work identifies the imperial procession reliefs flanking the entrance of Binyang Central Cave—geographically proximate to Guyang Cave and stylistically contemporaneous—as the most immediate comparanda for these ceremonial representations. This contextual evidence suggests that Yuan Xiang’s commission participated in a broader regional artistic convention while maintaining its distinctive symmetrical organization.

These Henan processional reliefs exhibit two distinctive characteristics that suggest elite patronage: (1) their substantial scale relative to other cave carvings, and (2) the meticulously rendered luxurious attire of the participants. Such features strongly associate these images with aristocratic Buddhist devotional practices. This connection finds particular relevance in Case 6, as its patron Yuan Xiang belonged to the Northern Wei imperial clan. The dedicatory inscription accompanying Yuan Xiang’s commission provides crucial contextual evidence for interpreting the ceremonial importance of these procession scenes, recording that “in the twenty-third day of the ninth month of the twenty-second year, the Buddha’s appearance was completely carved. Because of this, we made a vegetarian feast, and inscribed on the stone stele to express our hearts, restating our previous vows and wishes. We eternally wish that us mother and son would live a long life. We also wish that all beings, whether affiliated or not, inside or outside, would prosper from the beginning to the end. We wish that all sentient beings would all share this bliss. In the twenty-third day of the ninth month of the twenty-second year of the Taihe Reign, Great Wei, Yuan Xiang, who holds the titles Palace Attendant, Protector-General, Prince of Beihai, made this. 至廿二年九月二十三日, 法容剋就. 因即造齋, 鐫石表心, 奉申前誌. 永願母子長餐化年. 眷屬內外, 終始榮期. 一切群生, 咸同斯福. 維大魏太和廿二年九月廿三日, 侍中, 護軍將軍, 北海王元詳造” (

Liu 2001, vol. 3, p. 55, inscription no. 1843).

On the day of completion, between the statue’s finalization and the engraving of the commemorative stele, Yuan Xiang conducted a significant ceremonial act—hosting a vegetarian feast for monastic and lay communities. This ritual practice finds frequent documentation in Buddhist dedicatory inscriptions across the period. The feast served a crucial religious function: while the physical statue had taken form, it required ceremonial activation to transform from mere sculpture to a locus of worship. Yuan Xiang’s banquet appears to have constituted precisely this type of consecratory ritual. The bilateral processions depicted below the niche likely commemorate this pivotal moment.

The composition presents a gendered division: one procession, led by Yuan Xiang himself, comprises male attendants, while the opposing group, headed by his mother, consists of female participants. This deliberate arrangement echoes the imperial iconography of the Central Binyang Cave’s famous dual processions, simultaneously documenting a specific historical event while employing established visual conventions of aristocratic Buddhist devotion.

Further supporting evidence for this interpretation comes from the sculptural program beneath Monk Fasheng’s statue, which features imagery directly associated with Yuan Xiang and his mother (

Figure 15). Here we encounter another symmetrically arranged pair of processions, mirroring the composition in Yuan Xiang’s niche. Significantly, the space between these processions contains an inscribed frame with a dedicatory text that explicitly states the patrons’ devotional intentions. The inscription reads “Now I, Monk Fasheng, fortunately encounter that Emperor Xiaowen wholeheartedly focuses on the Three Jewels(Buddhism). I also encounter that the mother and son, who is the Prince of Beihai, devoutly hold their faith in the two capitals. During the wonderful ritual performance, I have repeatedly received their feasts... For the mother and son, who is the Prince of Beihai, I made a statue so as to express the feelings and to state their kind treatment (with my gratitude). I, Fasheng, started the work, and the Prince’s family helped complete it. From morning to night, we foster respect for and dedicate the merit to the emperor...今法生徼逢孝文皇帝專心於三寶. 又遇北海母子崇信於二京. 妙演之際, 屢叨末筵……爲孝文並北海母子造像表情, 以申接遇. 法生構始, 王家助終. 夙宵締敬, 歸功帝王……” (

Liu 2001, vol. 3, p. 78, inscription no. 2299). Fasheng personally attended a significant vegetarian feast hosted by Yuan Xiang (the Prince of Beihai) and his mother. In his dedicatory inscription, he explicitly states that the statue was commissioned to “biaoqing” (表情)—an expression that carries dual interpretive possibilities. On one level, “qing” (情) likely denotes emotional sentiment—specifically, Fasheng’s profound gratitude for the prince and his mother’s enduring patronage. However, the term may also signify “scene” or “occasion,” suggesting an alternative reading: Fasheng sought to visually commemorate the solemn ritual conducted by Yuan Xiang and his mother following the statue’s completion, including their generous hosting of the vegetarian feast.

The processional imagery thus potentially serves a dual documentary function: it both honors the patrons’ piety and preserves a visual record of the ceremonial event. Given the aristocratic status of Yuan Xiang and his mother—who were well-versed in such Buddhist rituals—it is plausible that their participation in similar processions was commemorated multiple times, reinforcing their role as exemplary patrons of the faith.

The inscription further reveals an important aspect of the project’s execution: while Fasheng initiated the work, its completion required the intervention of the Prince of Beihai. This collaborative process suggests the project’s complexity and possible interruptions during construction. Several chronological clues emerge from the inscription. References to “the fortunate coincidence of Emperor Xiaowen’s wholehearted devotion to the Three Jewels and the dedication of merit to the emperor” establish a clear connection between Fasheng’s commission and imperial patronage. Furthermore, the mention of “the mother and son, the Prince of Beihai, maintaining their devout faith in the two capitals” appears to reference the capital’s relocation from Pingcheng to Luoyang. These indicators suggest the project likely commenced around 494, contemporaneous with many other statues in the Eight Great Niches of Guyang Cave. However, the inscription records completion in the fourth year of the Jingming era (503), indicating an unusually protracted construction period of nearly a decade. While the precise reasons for this delay remain unclear, the extended timeline underscores both the project’s significance and the potential challenges encountered during its realization.

Because of this, Fasheng included the following names in his patron list: Lay Devotee Yuan Baoyi 清信士元寶意, Lay Devotee Yuan Shanyi 清信士元善意, and the Prince of Beihai Disciple Yuan Furong 北海王弟子元伏榮 (

Liu 2001, vol. 3, p. 78, inscription no. 2299). The first two, who also have the surname Yuan, appear to be senior members of Yuan Xiang’s family. The third is the Prince of Beihai (Yuan Xiang) himself. It reflects Yuan Xiang’s direct contribution to Fasheng’s statue. Here Yuan Xiang referring to himself as a “disciple,” rather than a generic “lay devotee,” shows that he had formally joined the order.

Evidence supporting the conjecture is in Monk Huile’s inscription for his statue in the Guyang Cave, which was also completed in the fourth year of Jingming. It says “we are honored that the great Prince of Beihai shaved his head and entered the monastic order 蒙北海大王落髮入道” (

Liu 2001, vol. 3, p. 56, inscription no. 1850). Monk Huile also explicitly states the great Prince’s name at the end of the inscription: “Monk Huile made this for the Prince of Beihai, Yuan Xiang, who holds the titles of Palace Attendant, Grand Mentor, Minister of Education, and Executive Director of the Imperial Secretariat 比丘慧樂為侍中太傅司徒錄尙書事北海王元詳造” (

Liu 2001, vol. 3, p. 56, inscription no. 1850). This confirms Yuan Xiang’s formal ordination in the fourth year of Jingming (503)—the same year Fasheng completed his statue commission. By this time, Yuan Xiang had served under at least two emperors and experienced significant political advancement. Following Emperor Xiaowen’s death, his career progressed from the position of “Palace Attendant and Protector-General” (held in the 22nd year of Taihe, 498) to increasingly powerful roles. As a key advisor to the newly enthroned Emperor Xuanwu, Yuan Xiang attained the influential position of “Executive Director of the Imperial Secretariat,” placing him second in authority almost only to the emperor himself.

Having reached the pinnacle of political power with no further advancement possible, Yuan Xiang ultimately chose to retire from public office and enter monastic life. This transition created a need for spiritual guidance, prompting Yuan Xiang to seek a reliable religious advisor for himself and his family. These circumstances explain both his substantial investment in Fasheng’s statue project and his invitation for Fasheng to participate in the commemorative vegetarian feast following his own statue’s completion. The feast likely served not only as a consecration ritual but also as a ceremonial affirmation of their new teacher–disciple relationship within the Buddhist community.

In the end, the inscription on Yuan Xiang’s stele reveals the historical circumstances under which he initiated the statue and the stele: “On the eleventh day of the twelfth month of the eighteenth year of the Taihe reign, the emperor personally led the six banners south to campaign against the rebellious Xiao. The military and those who stayed in the state bade farewell at the intersection between the Yi and Luo Rivers. The sounds of departure and stay were divided outside the ‘Yique’ valley. The Grand Consort, with the sagely and virtuous rules, advised us on the journey. The younger brothers and sons, with a heart full of filial piety, presented tears and words. On that day, the Grand Consort returned home and made a vow at the Yi River, praying for the safety of mother and son, and promised to erect a statue of Maitreya here if they were reunited. 維太和之十八年十二月十一日, 皇帝親禦六旌, 南伐蕭逆. 軍國二容, 別於洛汭. 行留兩音, 分於闕外. 太妃以聖善之規, 戒途戒旅, 弟子以資孝之心, 弋言奉淚. 其日, 太妃還家. 伊川立願, 母子平安, 造彌勒像一區以置於此.” (

Liu 2001, vol. 3, p. 55, inscription no. 1843). This passage depicts a touching scene of a mother and son parting in tears as the army sets out on campaign. The mother made a promise that if her son returned safely to reunite with her, she would personally erect a statue at this location (Yique/Longmen). Thus, the completed niched statue was the result of both mother and son fulfilling their vow. The accompanying stele, as a witness, meticulously records this moving historical episode.

4.4. Large Characters: Reclaiming Agency from the Ceiling

Near the cave ceiling, Grand Consort Hou commissioned two adjacent Maitreya statues within a two-year period (502–503), creating an illuminating comparative case study. (

Figure 5). The first, dated to 502 (Case 7), was dedicated to her deceased husband and is paired with an accompanying stele. Just one year later in the fourth year of Jingming (503), she sponsored another nearby statue for her grandson, but with a significant variation: it lacks a stele, instead featuring its inscription within a simple rectangular frame beneath the statue (

Figure 16) (

Liu 2001, vol. 1, p. 199, niche no. D99, pl. 315, vol. 3, p. 76, inscription no. 2273). This intentional juxtaposition—two stylistically similar statues commissioned by the same patron in close proximity and temporal sequence, yet employing different commemorative formats—provides exceptional analytical value. It offers unique insights into how patrons conceptualized the relationship between sculptural images and textual records.

The 502 inscription, carved on a stele, features remarkably large characters measuring four centimeters in height. As

Stanley Abe (

2002, p. 233) astutely observes, “The text is beautifully carved in enlarged characters, 4 cm high, a logical strategy to offset the distance from which they must be viewed, but an example that was not followed in other inscriptions in the ceiling.” This exceptional treatment demands closer examination, particularly when contrasted with Grand Consort Hou’s 503 inscription in the adjacent niche, which employs standard-sized characters within a simple rectangular frame. The dramatic discrepancy in scale between these two contemporaneous commissions by the same patron suggests deliberate ritual considerations underlying the choice of epigraphic format. The large characters of the 502 stele visibly dominate all other ceiling inscriptions from the Northern Wei period. This intentional variation implies that Northern Wei patrons like Grand Consort Hou carefully calibrated the physical presentation of inscriptions to reflect the hierarchical significance of their dedications, reserving the most visually imposing format for the most ritually important commemoration.

When Grand Consort Hou selected her niche site in Guyang Cave during the Jingming era (500–503), the prime locations at more accessible heights had already been occupied by the Eight Great Niches commissioned during the late Taihe period (477–499). This spatial constraint forced her to accept a less optimal position near the cave ceiling—a location both physically elevated and visually distant from viewers. It was precisely these challenging viewing conditions that necessitated the innovative use of dramatically enlarged characters in her 502 inscription, transforming what might have been a compromise into a distinctive visual statement.

This solution, however, came at a substantial cost. The deliberate selection of enlarged characters severely constrained the stele’s textual capacity, limiting the inscription to just two essential sentences: “On the eighteenth day of the eighth month of the third year of the Jingming era (502), the grandmother of the former Prince of Guangchuan, Grand Consort Hou made a statue of Maitreya for her deceased husband, the Palace Attendant, Commissioned with Extraordinary Powers, General-in-chief of Conquering the North, and Prince of Guangchuan, Helan Han. May he forever escape suffering and swiftly attain enlightenment 景明三年八月十八日, 昔廣川王祖母太妃侯為亡夫侍中使持節征北大將軍廣川王賀蘭汗造彌勒像. 願令永絕苦困, 速成正覺.” At a mere 48 characters, this represents the most concise dedicatory text among all cases examined in this study. The brevity becomes particularly striking when compared to contemporary examples: Sun Qiusheng’s Case 2 inscription contains over 200 patron names in its second section alone, while Yin Aijiang’s adjacent 502 stele (

Figure 5), though commissioned in the same year, manages to incorporate 222 characters despite its significantly smaller dimensions (63 cm niche height vs. Hou’s 96 cm niche height) (

Liu 2001, vol. 3, pp. 52, 76, inscription no. 2271).

This contrast highlights the exceptional nature of Grand Consort Hou’s epigraphic strategy. Where most patrons maximized textual content within their spatial constraints, Hou prioritized visibility over discursive detail—a conscious aesthetic choice that transformed spatial limitations into a bold visual statement. The resulting inscription, while brief, achieves an unparalleled iconic presence through its exaggerated scale, ensuring its commemorative power would resonate across the cave’s vertical expanse.

The enlarged characters ensured legibility even for viewers standing on the cave floor, bridging the spatial divide between ceiling and ground level. This strategic epigraphic solution accomplished three objectives: First, it restored visual parity between Grand Consort Hou’s niche and the Eight Great Niches below—many of which featured finely crafted steles—allowing her commission to compete equally for viewers’ attention. Second, it reintegrated her Maitreya image into the cave’s primary visual program centered around the ground-level niches. Most significantly, through this intervention, Grand Consort Hou symbolically reclaimed her place within Guyang Cave’s original commemorative framework, reasserting her connection to the elite patronage network that had shaped the cave’s early development. This represents a remarkable instance of spatial negotiation through epigraphic innovation—where what initially appeared as a compromised location was transformed, through deliberate design choices, into a position of visual prominence that maintained dialogue with the cave’s most prestigious commissions.

In contrast to her 502 commission, Grand Consort Hou’s 503 inscription assumes a subordinate relationship to its accompanying statue. Devoid of a framing stele and relegated to a simple rectangular panel beneath the niche, the later inscription lacks both the visual prominence of its predecessor and the enhanced legibility afforded by enlarged characters. This diminished presentation precluded the Maitreya image from participating in the visual dialogue established by the cave’s principal niches, consigning it to relative obscurity near the ceiling.

The divergent approaches between these two consecutively commissioned works likely reflect distinct devotional purposes. While the 503 statue, dedicated to the spiritual welfare of her grandson, appears to have served primarily as a private votive offering with less concern for public visibility, the 502 stele and statue combination—though fundamentally intended as a memorial for her deceased husband—unintentionally achieved significant public prominence through its innovative design. The strategic use of enlarged characters not only fulfilled its commemorative function but also ensured that among all visitors to Guyang Cave, Grand Consort Hou’s tribute to her husband would command immediate attention, while her prayer for her grandson remained a more personal, secluded devotion.

5. The Guyang Steles as Ritual Art

This study examines the Guyang steles through three central perspectives in art history: style, space, and patronage. The analysis begins with a detailed stylistic examination of three groups of steles, focusing on four key cases. This examination highlights notable innovations in sculptural technique. For instance, the statue commissioned by Huicheng and its accompanying stele both display a pronounced high-relief style. The origins of this style are diverse—potentially influenced by the slightly earlier Yungang Grottoes or contemporary epitaph stones. In this case, the techniques of stele-making and statue-carving converge, demonstrating a blending of artistic traditions.

The stylistic analysis transitions into a discussion of the spatial context from which these styles emerge. Near the cave entrance at ground level, Huicheng’s stele captures viewers’ attention by harnessing natural light to create striking contrasts between light and shadow. At higher positions on the cave wall, the procession images on the base of Yuan Xiang’s sculpture are positioned closer to the viewers, enhancing their visibility. However, for carvings on the cave ceiling, which are far from the viewers, such methods proved ineffective. Instead, an exceptionally large character size was employed on Grand Consort Hou’s stele to ensure legibility.

This spatial context, in turn, is deeply rooted in the collaborative yet competitive relationships among the patrons. Taking the Eight Great Niches as an example, the patrons’ original intent in designing these niches may not have been solely to create isolated icons of worship. Rather, individual niched statues could also function as part of a broader visual network within the cave, interconnected with other statues. On the densely packed walls of the Guyang Cave, where niches are stacked layer upon layer, the steles served to integrate their accompanying statues into a cohesive network while simultaneously highlighting each statue’s unique agenda.

Ultimately, the patrons’ grand spatial arrangements were inextricably linked to their religious and ritual objectives within the Buddhist cave temple context. However, to assert that ritual requirements alone dictated stylistic choices or directly governed artistic production would be reductive. The procession images commissioned by Yuan Xiang exemplify a more sophisticated understanding of ritual art, revealing the dynamic interplay between visual representation and ceremonial practice in sacred spaces. These depictions may visually document the vegetarian feast ceremony described by Fasheng, which served as the celebratory culmination of the statue-making process. The accompanying stele, in this context, represents the final commemorative act of this ceremonial sequence. Rather than existing as discrete, static objects, the statue, procession images, and stele collectively constitute an unfolding ritual performance. More broadly, the spatial negotiations among patrons in the Guyang Cave formed a ritual process that was simultaneously enriched and propelled by concurrent artistic endeavors. In the late Northern Wei period, artistic expression and ritual practice emerged as mutually constitutive elements in the dynamic formation of religious and cultural traditions.