1. Introduction

The

Yongle Nanzang (hereafter cited as

Nanzang) 永樂南藏—carved in Nanjing from the 11th to the 18th year of the Yongle reign (1413–1420) under Emperor Zhu Di 朱棣, of the Ming Dynasty—was the second Imperial Buddhist Canon of the Ming Dynasty. It was officially expanded twice during the Jiajing 嘉靖 (r. 1522–1566) and Wanli 萬曆 (r. 1573–1620) eras, incorporating additional sutras (

Li and He 2003, pp. 406–13). It survived dynastic changes and continued to be expanded and printed in the early Qing Dynasty.

The Nanzang was housed at Da Bao’en Temple 大報恩寺 in Nanjing during the Ming dynasty (1368–1644) and Qing dynasty (1644–1911). The Director of the Bureau of Sacrifices (Cijisi langzhong 祠祭司郎中), serving in the Nanjing Ministry of Rites, was the administrative authority that managed the printing of the Nanzang during the late Ming Dynasty. Following the Ming–Qing transition, the Six Ministries (liubu 六部) in Nanjing were abolished by the Qing court. Thus, the printing of the Nanzang temporarily fell into an unmanaged state. Nevertheless, the demand for the Nanzang was not eliminated. Those who wanted the printing of the Nanzang had to face the first problem, “Which bureaucratic agency manages this matter?”

This study focuses on the substantive connections between the printing of the Nanzang during the Shunzhi 順治 (r. 1644–1661) reign and the functions of the Thirteen Yamen (Shisan yamen 十三衙門). The Thirteen Yamen managed inner court affairs during the 10th to 18th year of the Shunzhi reign (1653–1661), with its officials including eunuchs and Manchu Officials of the inner circle (Manzhou Jinchen 滿洲近臣).

The process discussed in this paper—during which Hengming Xingmei 恒明性美, the abbot of Guangji Monastery (Guangjisi 廣濟寺) in Beijing, printed the Nanzang successfully during the 13th to 16th year of the Shunzhi reign (1656–1659)—is a case study on how monks requested the printing of the Nanzang during this period. Whose possible support did Guangji Monastery seek? How did the inner court engage in the event? What role did the Nanzang play in the Shunzhi reign? These questions concern the continuation of the Nanzang during the Ming–Qing transition. This study aims to tackle these rarely discussed questions by examining the Thirteen Yamen’s activities relative to the printing of the Nanzang during the Shunzhi reign.

Previous studies have noted the printing of the

Nanzang in the early Qing Dynasty.

Yukei Hasebe (

1983) 長谷部幽蹊 stated that woodblocks of the

Nanzang appear to have survived the turmoil of the Ming–Qing transition without being destroyed. Currently, at least four editions of the

Nanzang printed in the Qing Dynasty have been preserved and are housed at the Kaiyuji 快友寺 in Yamaguchi, Japan (

Nozawa 1998, pp. 361–70); the Cultural Relics Museum in Ningwu 寧武文物館, Shanxi, China (

Li and He 2003, p. 432); the Yongquan Temple 湧泉寺in Fuzhou, China (

Lin and Su 2006); and Xingyuan Library in Yulin 榆林星元圖書樓, Shaanxi, China (

Lang 2019).

However, the process of printing the

Nanzang in the early Qing Dynasty is difficult to trace. Fortunately, the event during which Hengming printed the

Nanzang is recorded in “Jinling yin

zang xu 金陵印〈藏〉序”, written by Zhou Tiancheng 周天成 (

Tianfu 2006, pp. 173–82). “Jinling yin

zang xu” reveals that Hengming brought the letter issued by Zhang Jiamo 張嘉謨, the Seal-holding official of the Personnel Department (Siliyuan Zhangyinguan 司吏院掌印官), to Zhou Tiancheng, the chief of the Jiangning Weaving Bureau 江寧織造. The letter played a significant role in the

Nanzang’s printing.

Regarding the officials involved,

Nozawa (

1998, p. 328) suggested that Zhou was dispatched to assume the position of chief of the Jiangning Weaving Bureau in the 15th year of the Shunzhi reign (1658) while serving as Vice Minister of Works (Gongbushilang 工部侍郎). Moreover, Zhou took charge of printing the

Nanzang, with the assistance of Zhang, the vice chief of the Jiangning Weaving Bureau (

Nozawa 1998, p. 329). The term “Vice Minister of Works,” raised by Nozawa, was derived from the type in the extant edition of the

Nanzang, which reads “qinchai zhizao gongbu shilang Zhou Tiancheng 欽差織造工部侍郎周天成.” However, this term was carved in the 10th year of the Shunzhi reign (1653), when Zhou served as Vice Minister of Works in the Imperial Household Department (Neiwufu 内務府) and was dispatched to assume the chief of the Suzhou Weaving Bureau 蘇州織造.

Lepneva (

2024) suggested that Zhang and Zhou could have established professional ties through their service in the Jiangning Weaving Bureau. However, this opinion fails to consider the system of the Thirteen Yamen, in which both Zhang and Zhou served together during the mid-to-late Shunzhi reign. According to a historical document, Zhou was appointed to the chief of the Jiangning Weaving Bureau while serving in the Personnel Department (Siliyuan 司吏院), a Yamen of the Thirteen Yamen. Simultaneously, Zhang, the Seal-holding official of the Personnel Department, was Zhou’s superior. By clarifying Zhang Jiamo’s and Zhou Tiancheng’s concurrent senior roles within the Personnel Department of the Thirteen Yamen, this study revises the understanding of their collaboration from a simple shared assignment at the Jiangning Weaving Bureau to a hierarchical action within the central inner court apparatus.

Regarding the Thirteen Yamen, earlier studies primarily focused on eunuchs, with little attention paid to Manchu officials (

Zheng 1946;

Li 1991). Some pointed out that the power of the Thirteen Yamen was in the Manchu officials’ hands, and eunuchs were always not permitted to advance above the fourth rank (

Jiang 1991). However, this viewpoint is inconsistent with the documented conditions of the Thirteen Yamen’s initial establishment.

Kutcher (

2018) examined the role of eunuchs in the Shunzhi period based on Wang Jinshan’s (王進善)

Nei quan zou cao 内銓奏草, which also can be regarded as first-hand evidence for studying the Thirteen Yamen during the 12th to 13th years of the Shunzhi reign (1655–1656). However, this material remains unexplored in existing scholarship on the Thirteen Yamen. Thus, based on

Nei quan shu cao, this paper analyzes the official positions of Zhang, Zhou, and others, laying the foundations for discussions regarding the Thirteen Yamen’s involvement with the

Nanzang.

Building on these studies, this paper aims to explore the involvement of the inner court, especially the Thirteen Yamen, in the printing of the Nanzang. This involvement casts new light on the printing of the Nanzang in the early Qing Dynasty. It guides us to observe how the Shunzhi court inherited the Nanzang from its Ming predecessor from a printing perspective. In addition, this paper employs previously underutilized archival materials, Wan Jinshan’s Nei quan zou cao, which could shed light on the bureaucratic organization and roles of key personnel within the Thirteen Yamen at that time (1655–1656, for events in 1658). More importantly, its value lies in firmly establishing the contemporaneous official capacities and networks of the individuals who later facilitated the printing of the Nanzang. This study reveals that the Thirteen Yamen were deeply involved in the printing of the Nanzang and that the Shunzhi Court inherited the Nanzang from its Ming predecessor.

Combined with the historical fact uncovered in this study—that

Wudenghuiyuan Zuanxu 五燈會元纘續 and

Miyun Yuanwu Chanshi Yulu 密雲圓悟禪師語錄 were successively canonized into the

Nanzang by imperial decree in the 14th and 17th years of the Shunzhi reign (1657 and 1660)—this study concludes that the

Nanzang was one of the Imperial Buddhist Canons during the Shunzhi reign, altering the opinion that the

Nanzang was ultimately identified as a private canon during the Ming–Qing dynastic transition (

Hasebe 1983). Furthermore, scholarship has long examined the history of the Qing Imperial Chinese Buddhist Canon predominantly from the periods of the Emperor Yongzheng 雍正 (r. 1723–1735) and Emperor Qianlong 乾隆 (r. 1736–1795) onward, with the Shunzhi and Kangxi 康熙 (r. 1662–1722) periods remaining underexplored (

Li and He 2003). This study enhances the historical study of the Chinese Buddhist Canon during the early Qing period.

Identifying the Nanzang as an Imperial Chinese Buddhist Canon during the Shunzhi reign is of critical importance for the following reasons. First, the dynastic transition did not invalidate the Nanzang’s official status, reflecting some degree of continuity between the Ming and Qing regimes in the transmission of the Buddhist canon. Studies on the reception of the official Buddhist canon from the previous dynasty remain rare, partly due to the destruction of woodblocks during wartime. This paper thus offers an important reference on this issue. Second, the Qing regime’s continued recognition of the Nanzang as an Imperial Buddhist canon effectively established a buffer zone between the Qing court and those who refused to submit to it, creating a shared discursive foundation through the veneration of the Buddhist canon. This reflects the Qing regime’s attempt to create an opening for implementing its new rule by inheriting the Imperial Buddhist Canon of the Ming Dynasty.

Historical–institutional methodology is employed to reconstruct the administrative processes and interpersonal networks that facilitated the printing of the Nanzang during the Shunzhi reign. We draw upon primary sources, including (1) official memorials from Nei quan zou cao; (2) colophons such as “Jinling yinzang xu”; (3) local gazetteers; and (4) documents recorded in the Nanzang edition of Miyun Yuanwu Chanshi Yulu. As Nei quan zou cao has been largely overlooked in the study of Buddhism in the Qing Dynasty, this paper represents the first study to utilize this document for research on the Nanzang. Moreover, prosopographical analysis is applied to trace the networks of eunuchs and officials.

2. The Relationship Between the Guangji Monastery and the Former Ming Eunuchs in the Qing Palace

In the 13th year of the Shunzhi reign, Hengming left Beijing and traveled to the south (

Tianfu 2006, pp. 103–4). Two years later, when Zhou Tiancheng, the chief of the Jiangning Weaving Bureau, took charge of the restoration of the canon-storing pavilion (cangjingdian 藏經殿) at Da Bao’en Temple, Hengming happened to request the printing of the

Nanzang. After the printing was completed, Zhou documented the printing process in “Jinling Yin

zang Xu”, as described below:

When collecting building materials and gathering laborers, the Vinaya master Hengming, the abbot of Guangji Monastery in Beijing, along with other associates, held letters and funding from Zhang Jiamo, the Seal-holding official of the Personnel Department, and Feng Xiangong, Zhang Qixiang, Liu Dengke, and Sun Jiru. In a letter, I was entrusted with the responsibility of overseeing the printing of the Nanzang. The officials exerted efforts collectively to participate in this enterprise. 正在庀材鳩工,忽有都門廣濟寺住持律師恒明等,持司吏院掌印理事官張公嘉謨暨馮公顯功、張公起祥、劉公登科、孫公繼儒等書併捐資,屬予印《藏》全經,以董其事。此衆宰官之願力相濟.

As recorded at the end of the “Jinling Yinzang Xu”, this documentation was written during the 8th month of the 16th year of the Shunzhi reign (1659). The Guangji Monastery shifted to a Vinaya monastery (lvsi 律寺) during the Shunzhi reign; thus, Hengming was called “the Vinaya master.” Other associates included several monks in charge of carrying the canon.

The roles in the printing of the

Nanzang performed by Feng Xiangong, Zhang Qixiang, Liu Dengke, Sun Jiru, and Zhang Jiamo must be clearly differentiated. Feng Xiangong, a patron of Guangji Monastery (

Tianfu 2006, pp. 101–2), and Zhang Qixiang and Liu Dengke were famous benefactors in Beijing. These three individuals provided donations to restore the Medicine King Hall (Yaowangdian 藥王殿) during the 8th year of the Shunzhi reign (1651),

1 and 2 years later they donated to Jingang Temple 金剛寺.

2 Sun Jiru, a booi 包衣of the Manchu Bordered Yellow Banner, served as the District Magistrate (zhixian 知縣) in the Xiushui District of Jiaxing Prefecture, Zhejiang Province, during the 7th to 8th year of the Shunzhi reign (1650–1651) (

Ren and Fan 2011, p. 845). He provided donations to restore the Guan Di temple 關帝廟 in the 8th year of the Shunzhi reign.

3 It seems plausible to assume that the funding Hengming held was mostly from these four benefactors.

The roles in the printing of the

Nanzang performed by Feng Xiangong, Zhang Qixiang, Liu Dengke, Sun Jiru, and Zhang Jiamo must be clearly differentiated. Feng Xiangong, a patron of Guangji Monastery (

Tianfu 2006, pp. 101–2), and Zhang Qixiang and Liu Dengke were famous benefactors in Beijing. These three individuals provided donations to restore the Medicine King Hall (Yaowangdian 藥王殿) during the 8th year of the Shunzhi reign (1651),

1 and 2 years later they donated to Jingang Temple 金剛寺.

2 Sun Jiru, a booi 包衣of the Manchu Bordered Yellow Banner, served as the District Magistrate (zhixian 知縣) in the Xiushui District of Jiaxing Prefecture, Zhejiang Province, during the 7th to 8th year of the Shunzhi reign (1650–1651) (

Ren and Fan 2011, p. 845). He provided donations to restore the Guan Di temple 關帝廟 in the 8th year of the Shunzhi reign.

3 It seems plausible to assume that the funding Hengming held was mostly from these four benefactors.

The letter that played an important role in the printing of the

Nanzang was from Zhang Jiamo, the Seal-holding official of the Personnel Department. Zhang, a booi 包衣of the Manchu Bordered Yellow Banner (

Qianlongwushiyinian Chizhuan 2008, p. 330), had already served as a Company Commander (niulu zhangjing 牛錄章京) in the 8th year of the Shunzhi reign

4 and was the chief of the Jiangning Weaving Bureau in the 13th year (

Yin and Huang 2016, p. 64). In the 9th month of the 15th year of the Shunzhi reign, he served as an imperial commissioner (qinchai 欽差) in the Personnel Department within the Thirteen Yamen and summoned Yulin Tongxiu 玉林通琇 to Beijing (

Huishi 2015, p. 98). Zhang Jiamo was called “the Seal-holding official of the Personnel Department” in “Jinling Yin

zang Xu;” therefore, the letter should have been written during his tenure in this position.

It is puzzling how Hengming, being merely an abbot, was able to obtain the letter from the Personnel Department and succeeded in printing the Nanzang.

It is highly likely that Hengming made use of the Guangji Monastery’s ties with the former Ming eunuchs in the Qing Palace to obtain official support. During the late Ming to early Qing era, Hengming and eunuchs in the inner court sustained close relationships, as can be inferred from their experiences.

In the 1st year of the Chongzhen 崇禎 (r. 1628–1644) reign, Hengming stayed in Ersheng Chapel (Ersheng’an 二聖庵), a subbranch (xiayuan 下院) of the Guangji Monastery. After Hengming demonstrated effective management skills in the chapel, officials from the Ministry of Personnel and War, censors, and eunuchs came to visit frequently. Wang Yongzuo 王永祚, the eunuch of the Directorate of Ceremonial (silijian 司禮監),

5 showed particular reverence towards Ersheng Chapel and donated 10 mu of land for vegetable farming. Hengming also invited Dharma master Manyue Qing 滿月清 of the Wofo Monastery (Wofosi 卧佛寺) to deliver sutra lecturers in Ersheng Chapel. Soon, Manyue received patronage from Empress Zhou 周皇后 (1611–1644) and had several lay disciples who took Buddhist refuge from him, including Li Guozhen 李國禎, Earl of Xiangcheng (Xiangchengbo 襄城伯), and Wang Zhichen王之臣 and Cao Huachun 曹化淳 (1589—1662)

6, both of whom were eunuchs of the Directorate of Ceremonial.

After the death of Emperor Chongzhen, Ma Hualong 馬化龍, the former Ming eunuch, invited Hengming to preside over Guangji Monastery in the 1st year of the Shunzhi reign (1644). The Gazette of Guangji Monastery (Guangji Si zhi 廣濟寺志) recorded the following:

In the 1st year of the Shunzhi reign, Li Zicheng李自成 (1606–1645), the leader of the rebel army, assaulted Beijing suddenly, bringing endless suffering and devastation to all living things. The imperial army entered Shanhaigua 山海關and chased them out. The Eight Banners (baqi 八旗) resided in the dwellings of the Ming Dynasty people, causing great panic in the Buddhist monastic community about losing temples. Although Monk Leshan 樂山僧was a venerable elder in Guangji Monastery, he could not hold on any more. Ma Hualong donated 12 qing of land located in Liulin Village 柳林村to Guangji Monastery as a gift for meeting with Hengming. He came to Ersheng Chapel and invited Hengming back to Guangji Monastery. Consequently, Hengming returned to Guangji Monastery. 世祖章皇帝順治元年,賊目李自成突犯闕下,荼毒生靈殆盡。皇師入關,逐之。八旗所處皆故明宅第,叢林未免築薛之恐。樂山僧為廣濟耆宿,不能支。馬化龍捨柳林地十二頃,作贄見禮,迎師於二聖庵,師復如廣濟。

Leshan, a monk of Guangji Monastery, served as the subprior (fusi 副寺) after Hengming, presiding over Guangji Monastery. Ma Hualong, the Eunuch-in-Charge in the Imperial Treasury (chengyunku zhangkushi 承運庫掌庫事), served in the Directorate of the Imperial Stables (yumajian 御馬監) during the Chongzhen reign (

G. Zhang 2000, p. 134).

In the 5th month of the 1st year of the Shunzhi reign, the Manchu army entered Beijing City, establishing regulations that dictated that the people of the Eight Banners should live in the eastern, western, and central parts of the city while Han Chinese lived in northern and southern parts, in addition to the vacant lands of the eastern, western, and central parts (

H. Zhao 2013). Guangji Monastery, located in the western city,

7 was occupied by people of the Eight Banners, causing panic among the monks. At this time, Ma Hualong offered them help. He not only donated 12 qing of land located in Liulin Village, Changping county 昌平縣, to Guangji Monastery but also went to Ersheng Chapel personally to invite Hengming to preside over the monastery. In the same year, Hengming invited Manyue to shengzuo 陞座 and preached sutras in Guangji Monastery. Manyue delivered lectures on the

Huguo renwang jing 護國仁王經. The Eight Princes (bawang 八王) arrived and behaved courteously towards Hengming (

Tianfu 2006, p. 111).

Until the 8th month of the 5th year of the Shunzhi reign (1648), the Imperial Court stipulated that the monks and Daoist priests who lived in temples within the inner city of Beijing should not be disturbed (

Qing Shilu 1985, vol. 3, p. 319), alleviating Guangji Monastery from pressure amidst the turmoil caused by the division of residential areas between the people of the Eight Banners and Han Chinese. However, during the 2nd to 4th years of the Shunzhi reign (1645–1647), the people of the Eight Banners occupied residential lands three times. The occupation included counties affiliated with Shuntian Superior Prefecture 顺天府, which was located close to Beijing City at first but then expanded outward (

L. Zhao 2001).

During the 1st to 5th years of the Shunzhi reign (1644–1648), the relocation policy concerning monks and Daoist priests living in temples within the inner city had not yet been formally promulgated. Ma Hualong was able to donate a large tract of land in Changping county and save Guangji Monastery from relocation. The Eight Princes came to Guangji Monastery afterwards. These events reveal that Ma Hualong remained in office, retaining a certain rank and level of power in the royal court of Shunzhi after the establishment of the Qing Dynasty, although it is difficult to obtain more detailed information about Ma Hualong’s activities in the inner court of Shunzhi.

However, what motivated Ma Hualong to provide so much support for Guangji Monastery? It is possible that his patronage continued the prevailing practice of mutually beneficial collaboration between eunuchs and monks, a phenomenon that had been ongoing since the late Ming dynasty.

8 However, whether Ma Hualong was a dependent (mingxia 名下) of Wang Yongzuo, Wang Zhichen, or Cao Huachun still requires further investigation.

Cao Huachun was another potential figure from whom Hengming might have sought support. Cao, the eunuch of the Directorate of Ceremonial during the Chongzhen reign, held overwhelming influence in both the Imperial Court and the administration. After the young Emperor Shunzhi came to real power, Cao gained his favor and became his private tutor, regularly presenting lessons to him on both Chinese classics and Buddhist sutras (

Xie 2009). In the 8th month of the 14th year of the Shunzhi reign (1657), Hanpu Xingcong 憨璞性聰 entered the royal court of Shunzhi. He praised Cao, “You once received entrustment (zhufu 囑咐) from Master Lingfeng, today become the stand-by of Buddhist monastic community 昔日靈峰親囑咐,今時法社賴維屏.” It can be observed that Cao contributed to protecting the Dharma during the Ming–Qing dynastic transition. In addition, as mentioned before, he sought Buddhist refuge from Dharma master Manyue. Therefore, Cao Huachun was another eunuch of the Ming Dynasty in the Qing Palace who was very likely to have provided help for Hengming in printing the

Nanzang.

Eunuchs under the Shunzhi emperor maintained their favorable positions in society and at court. Moreover, some former Ming eunuchs held power stemming from connections built before the conquest (

Kutcher 2018, p. 51). It is evident that Ma Hualong and Cao Huachun were two of these former Ming eunuchs. It is worth mentioning that Emperor Shunzhi personally visited Guangji Monastery shortly after Hengming’s departure from Beijing. In the winter of the 13th year of the Shunzhi reign, Emperor Shunzhi went to Guangji Monastery after hearing that the Vinaya master Yuguang Kuanshou 玉光寬壽 had achieved an advanced stage of Buddhist cultivation. Yuguang failed to greet Emperor Shunzhi, subsequently submitting the

Fanwang jing 梵網經 to justify his conduct. Emperor Shunzhi was convinced and summoned him to the inner court to deliver sutra lectures. After this, Emperor Shunzhi instructed officials undertaking the classic mat lecture (jingyan 經筵) to deliver the daily lecture (rijiang 日講) on the

Fangang jing, and funds were sent to Guangji Monastery. (

Tianfu 2006, p. 120)

Evidence suggests that Emperor Shunzhi demonstrated particular attentiveness towards Guangji Monastery, a phenomenon potentially attributable to the intermediary roles of the former Ming eunuchs in the Qing Palace. It also shows that Guangji Monastery had established a relatively close connection with the Imperial Court of Shunzhi before Hengming left Beijing, which was an important precondition, for Hengming could obtain the letter from the Seal-holding official of the Personnel Department.

3. Materials on the Thirteen Yamen as Recorded in Nei quan zou cao

During the Ming–Qing dynastic transition, Guangji Monastery and the former Ming eunuchs in the Qing Palace maintained close contact. Before Hengming left Beijing, some eunuchs in the Qing Palace and Manchu Officials of the inner circle served among the Thirteen Yamen, which managed court affairs during the 10th to 18th years of the Shunzhi reign (1653–1661).

A Yamen of the Thirteen Yamen comprised the Personnel Department. According to the document that announced its formation, the Thirteen Yamen were established on the 29th day of the 6th month in the 10th year of the Shunzhi reign, when the Personnel Department was named the Ceremonial Directorate (

W. Zhang 1986). In the 18th year of the Shunzhi reign, after the death of Emperor Shunzhi, the Thirteen Yamen were dissolved (

Qing Shilu 1985, vol. 4, p. 49). Because of variations in the organizations, the circumstances surrounding the Thirteen Yamen’s situations before Hengming’s departure from Beijing are not easily known. Fortunately,

Nei quan zou cao includes memorials dating to the 12th to 13th years of the Shunzhi reign (1655–1656) submitted by Wang Jinshan, the Chengyuan 承院 of the Personnel Department, which offer previously unexamined evidence regarding the role of the Thirteen Yamen in the printing of the

Nanzang (

Wang 1988).

On the 16th day of the 6th month in the 13th year of the Shunzhi reign, Wang Jinshan submitted his eleventh memorial, documenting personnel affairs related to the throne. He wrote the following:

Man-guan and Han-guan are serving together in all departments in the inner court. The chiefs of Man-guan and Han-guan are in charge of affairs, and their deputies assist. 竊照内庭諸司,各設滿漢官員,既有滿漢首領以挈綱,復設滿漢佐貳以分參贊。

After Yuan, Jian, Si, and Ju were reorganized, among the Man-guan, four Assistant Administrators (fulishiguan 副理事官) were established, besides the Seal-holding officials. 曩自改設院、監、司、局、舘衙門,满官除掌印之外,每設副理事官肆員。

Han-guan were promoted according to positions, while Man-guan were never promoted. This demonstrates a discrepancy between penalties and incentives, which constitutes the second debatable issue. 漢官則循職擢陞,而滿官則從未遷轉,是懲勸懸别,此其可議者二。

In this context, the term “Man-guan” refers to the Manchu Officials of the inner circle, while the term “Han-guan” denotes the Han Chinese eunuchs serving in the inner court. The Personnel Department was reorganized from the Ceremonial Directorate shortly after the establishment of the Thirteen Yamen. Each Yamen of the Thirteen Yamen comprised two leaders, Man-guan and Han-guan, and their corresponding subordinates. The chief of Man-guan, with four Assistant Administrators, was called the Seal-holding official. During the 12th to 13th years of the Shunzhi reign, in the Personnel Department, the chief of Han-guan was Wang Jinshan, serving as Chengyuan, while the chief of Man-guan was Zhang Jiamo, serving as the Seal-holding official (

Wang 1988, p. 172). Zhou Tiancheng was one of the Assistant Administrators under Zhang’s supervision (

Wang 1988, p. 157).

At the same time, Cao Huachun also served in the Thirteen Yamen. On the 19th day of the 1st month in the 13th year of the Shunzhi reign, Wang Jinshan was impeached for accepting bribes from Cao Huachun in exchange for recommending Cao’s promotion. Lu Tianshou 盧添壽, serving in Shangfang Yuan 尚方院, alleged the following:

At first, I thought the recommendation of Cao Huachun and others by Yuanchen was a behavior of recommending talents for the Imperial Court. Who can expect that he accepted gifts from Cao? Cups and plates were included, and silver was very likely included in the gifts. 初院臣之疏舉曹化淳等,臣固以其爲國薦才也。詎期其受化淳等餽送之禮?盃盤等物,受之最真,白鏹朱提,勢所必有。

Shangfang Yuan, a Yamen of the Thirteen Yamen, was institutionally in charge of investigating and impeaching misconduct. Wang Jinshan refuted the allegations, asserting that his recommendation of Cao was not contingent upon any financial compensation. In the prosecution and defense process, it is evident that Wang Jinshan recommended Cao Huachun, and they maintained a close contact. In the 1st month of the 13th year of the Shunzhi reign, Cao served as a keeper of imperial brushes (bingbi 秉筆) in the Thirteen Yamen (

Wang 1988, p. 104), a position for which Wang Jinshan’s recommendation was probably responsible. Although it is not clear whether Ma Hualong served in the Thirteen Yamen, it can be observed that the former Ming eunuchs in the Qing Palace should have played an important role in connecting Guangji Monastery and the Thirteen Yamen.

4. The Thirteen Yamen Were Deeply Involved in the Printing of the Nanzang

Another point is that the Guangji Monastery must have turned to the Personnel Department for help in printing the Nanzang because it had established a certain connection with the Imperial Court of Shunzhi. In other words, in order to request the printing of the Nanzang, Hengming had to request instructions from the Personnel Department and obtain its approval.

From the perspective of the management organization, the Depository of Chinese Classics (Hanjingchang 漢經廠) of the Ceremonial Directorate took charge of the carving of Buddhist scriptures in the inner court of the Ming Dynasty (

Liu 1994, p. 157). As the Personnel Department was reorganized from the Directorate of Ceremonial (

Zheng 1946, p. 71), the Palace Buddhist Office was likely to be under its management.

The remaining woodblocks of the Yongle Northern Canon (

Yongle Beizang 永樂北藏) housed in the Palace Buddhist Office were seriously damaged during the Ming–Qing transition and remained unrestored in the 13th year of the Shunzhi reign,

9 a practical reality that Hengming must have taken into account. Therefore, Hengming requested that the

Nanzang be printed in Jiangnan rather than the

Yongle Beizang in the inner court.

The Jiangning Weaving Bureau was in charge of printing the

Nanzang after receiving instructions from Zhang Jiamo, the Seal-holding official of the Personnel Department, through a private letter instead of an official document, illustrating a semi-official method for conducting official business. The Personnel Department’s authority over the

Nanzang woodblocks was not regulated institutionally by the Shunzhi court. In addition to Zhang jiamo’s instructions having been conveyed through a private letter, this can also be deduced from a dialogue between Emperor Shunzhi and Daomin 道忞 in the 17th year of the Shunzhi reign.

10Emperor Shunzhi asked, “Where is the Nanzang housed? Which officers were responsible for managing it?” Daomin replied, “The woodblocks of the Nanzang are housed at the Da Bao’en Temple. Management responsibility used to be under the Nanjing Ministry of Rites. Since our current dynasty does not have such an official position, perhaps the responsibility lies with the monastic authorities. 上曰:“《南藏》收藏何處?甚麼官員職掌?”師曰:“版藏大報恩寺,明朝管屬禮部,我朝不設此官,或責在僧司也。”

According to Daomin’s response, the Personnel Department’s authority over the Nanzang woodblocks had not been established institutionally in the Shunzhi court. Thus, a few years later, it was suggested that the Nanzang was perhaps under the Central Buddhist Registry’s (senglusi 僧錄司) management. Considering the fact that the Personnel Department was reorganized from the Ceremonial Directorate during the Ming Dynasty, it seems safe to say that the Personnel Department’s authority over the Nanzang woodblocks was an implicitly inherited responsibility from the Ming Ceremonial Directorate rather than a newly asserted one. Moreover, its authority was an informal responsibility due to the administrative vacuum left by the abolishment of the Nanjing Ministry of Rites.

The main reason why the Personnel Department instructed the Jiangning Weaving Bureau rather than other officials to take charge of the printing was that the chief of the Jiangning Weaving Bureau had been dispatched from the Thirteen Yamen during the 13th to 15th years of the Shunzhi reign (1656–1658). The following is recorded in Kangxi Jiangnan Tongzhi 康熙江南通志:

The Imperial Commissioners who were dispatched to supervise the Jiangning Weaving Bureau are listed as follows. Zhang Yuanxun, a native of Liaodong, was incumbent in the 5th year of the Shunzhi reign. Yang Wenke. Zhang Jiamo, Manchu, was incumbent in the 13th year of the Shunzhi reign. Yang Binggong, a native of Beizhi. Liu Zhiwu, Manchu, was incumbent in the 14th year of the Shunzhi reign. Zhou Tiancheng, Manchu, was incumbent in the 15th year of the Shunzhi reign. Cao Xi, Manchu, was incumbent in the 2nd year of the Kangxi reign. 督理江寧織造府:張元勲,遼東人,順治五年。楊文科。張嘉謨,滿洲人,順治十三年任。楊秉恭,北直人。劉之武,滿洲籍,順治十四年任。周天成,滿洲人,順治十五年任。曹璽,滿洲人,康熙二年任。

The Jiangning Weaving Bureau was established in the Ming Dynasty, with the office of the Prince of Han appointing eunuchs to oversee its operations. At the beginning of the Qing Dynasty, Hong Chengchou from the inner court submitted a memorial stating that the Jiangning Weaving Bureau should maintain its original functions. Officers from the Ministry of Revenue were dispatched to manage this organization in the 5th year of the Shunzhi reign. Until the 13th year of the Shunzhi reign, officers from the inner Thirteen Yamen were dispatched with a tenure of 1 year, which changed to 3 years in the 15th year of the Shunzhi reign. In the 2nd year of the Kangxi reign, officers in charge served as the Imperial Commissioners with permanent tenure. 江寧織造衙門,自有明設立,漢府用太監管理。國初内院洪承疇題奉照舊織造。順治五年始差戶部官董理。至十三年改差内十三衙門官,一年一換。至十五年,改三年一換。康熙二年遂定專差久任。

Considering the cases of Zhang Jiamo and Zhou Tiancheng, the above quote is credible, stating that officers from the Thirteen Yamen were to be dispatched to supervise the Jiangning Weaving Bureau during the 13th to 15th years of the Shunzhi reign.

11Building upon the aforementioned analysis of Zhang Jiamo’s position, we can conclude that Zhang assumed the chief of the Jiangning Weaving Bureau while serving as the Seal-holding official of the Personnel Department.

As for Zhou Tiancheng, Kangxi Wenxi Xianzhi 康熙闻喜縣志 documents his official career as follows:

Zhou was appointed as the Imperial Procession Guard (Luanyiwei 鑾儀衛) at first, then the Qixin Minister of Justice (Xingbu qixinlang 刑部啓心郎), a Vice Minister of Works (Gongbu shilang 工部侍郎), a Chief Secretary (Suitang 隨堂) in the Personnel Department, and the Weaving Bureau in Suzhou, Hangzhou, and Jiangning. 初授鑾儀衛,歷刑部啓心郎,轉工部侍郎,調司吏院隨堂,織造蘇、杭、江寧。

In the 10th year of the Shunzhi reign, Zhou assumed a position in the Suzhou Weaving Bureau while serving as Right Vice Minister of Works (Gongbu youshilang 工部右侍郎) in the Imperial Household Department (neiwufu 内務府) (

Sun 2015, p. 504). This means that the “Vice Minister of Works” quoted above was an official role within the Imperial Household Department. The Weaving Bureau was abolished in the 11th year of the Shunzhi reign (1654) and restored 2 years later. Then, Zhou was appointed to the position in the Hangzhou Weaving Bureau while serving as the Assistant Administrator (

Ma and Yang 1686, vol. 19, p. 43) in the Personnel Department (

Wang 1988, p. 157).

During the 15th year of the Shunzhi reign to the 2nd year of the Kangxi reign (1658–1663), Zhou Tiancheng was dispatched to the position in the Jiangning Weaving Bureau (

Qing Shilu 1985, vols. 3, 4, pp. 170, 522). The term “Chief Secretary” quoted above was a rank-denoting sinecure established after the 6th month of the 13th year of the Shunzhi reign (

Wang 1988, pp. 227–28). It can be observed that Zhou served in the Personnel Department while assuming the position in the Jiangning Weaving Bureau in the 15th year of the Shunzhi reign.

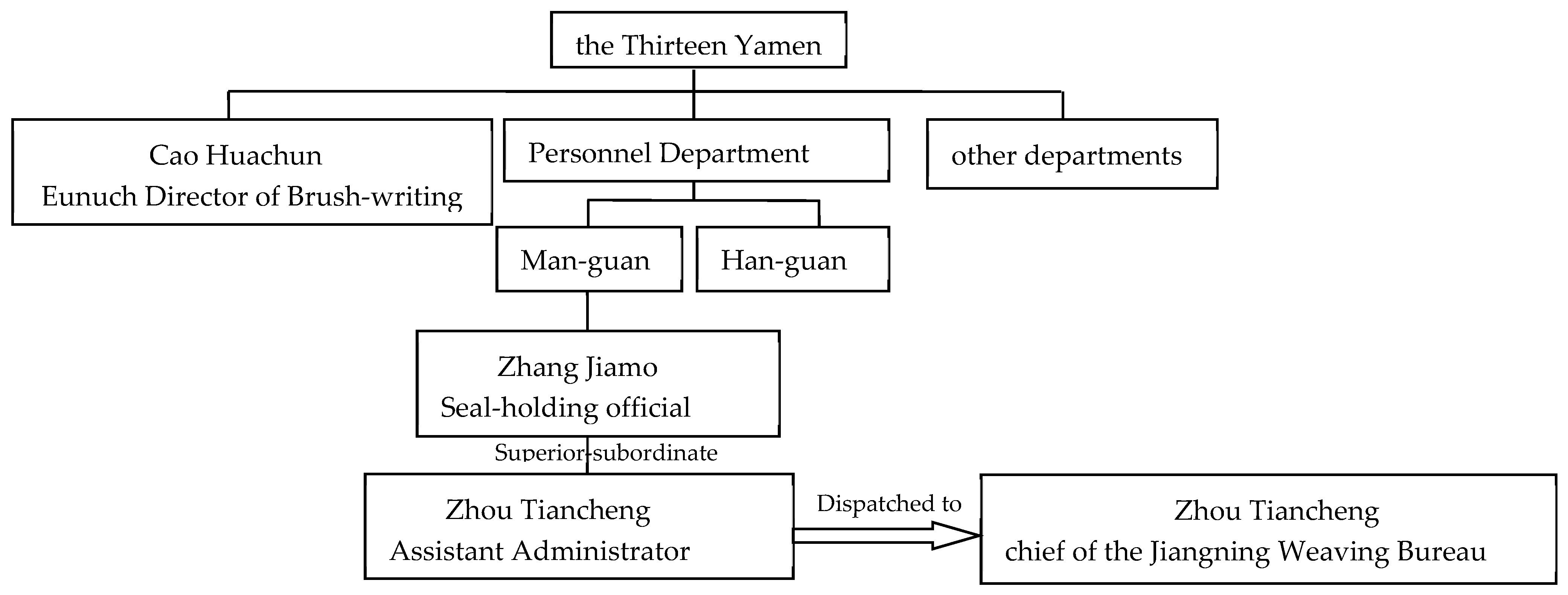

An integrated analysis of these documentary sources demonstrates that Zhou Tiancheng served in the Personnel Department in the 13th to 15th years of the Shunzhi reign. Moreover, his substantive position was most probably Assistant Administrator. The institutional relationships among the Thirteen Yamen, the Personnel Department, and the Jiangning Weaving Bureau can be visually presented in the following

Figure 1.

Based on the aforementioned analysis, Zhang Jiamo, the Seal-holding official of the Personnel Department, instructed the Jiangning Weaving Bureau to take charge of printing the Nanzang; this act indicates that he effectively commanded his subordinates to undertake specific affairs in the department. Although the Jiangning Weaving Bureau oversaw the actual printing, the authority to manage the woodblocks of the Nanzang belonged to the Personnel Department.

In addition, Ma Pian’e 馬偏俄, who was “the Imperial Commissioner dispatched to supervise the Suzhou Weaving Bureau while serving as the Seal-holding director of the Palace Regalia Service (Sisheju 司設局)”, was a patron in the printing of the

Nanzang (

Tianfu 2006, p. 180). In the 15th year of the Shunzhi reign, Ma Pian’e assumed a position in the Suzhou Weaving Bureau while serving in the Palace Regalia Service (

Sun 2015, p. 504). The Palace Regalia Service was also a Yamen of the Thirteen Yamen.

12The Personnel from the Thirteen Yamen participated in the Nanzang’s printing process, including management, supervision, and sponsorship. It is evident that the Thirteen Yamen were deeply involved in the printing of the Nanzang.

6. The Printing and Storing of the Nanzang in Various Regions in the Early Qing

In addition to Guangji Monastery, various regions requested the printing of the Nanzang in the early Qing Dynasty. Printing continued at least until the Yongzheng reign. Other records of the Nanzang’s printing in the early Qing Dynasty are as follows.

In the 12th month of the 1st Shunzhi reign (1644), Zuxin Hanke 祖心函可, the dusi 都寺 of Huashou Monastery (Huashousi 華首寺) at Mount Luofu in Boluo, arrived in Nanjing (Jinling) to request the printing of the Nanzang but seemingly failed (

Zuxin 2016, p. 263).

In the 9th year of the Shunzhi reign (1652), Yongjue Yuanxian 永覺元賢, the abbot of Yongquan Monastery (Yongquansi 湧泉寺) at Gushan 鼓山in Fuzhou, sent his disciples Jinghui Dengzhao 淨輝等炤 and Taijing 太靖 to Nanjing to request the printing of the

Nanzang. This printing of the

Nanzang was patronized by Huang Zhisan 黃植三, a lay Buddhist from Quanzhou, and was housed in Zhengfa-zang Hall 正法藏殿. A portion of this copy has survived and is housed in Yongquan Monastery (

Huang 2006, pp. 530, 543).

During the 10th to 16th years of the Shunzhi reign (1653–1659), Zhuang Jiongsheng 莊冏生, a native of Wujin, patronized a copy of the

Nanzang. He achieved jinshi 進士 status in the imperial examination during the 4th year of the Shunzhi reign (1647) and served as a Hanlin Bachelor (Hanlinshujishi 翰林庶吉士) and then a Hanlin Historiography Examining Editor (Hanlinjiantao 翰林檢討). After the printing was completed, this copy of the

Nanzang may have been housed in Yushan Monastery (Yushanan 與善庵) in Wujin. (

Nozawa 1998, pp. 367–70).

In the 10th year of the Kangxi reign (1671), Xiangguo Monastery (Xiangguosi 相國寺) in Kaifeng also attained a printed copy of the

Nanzang from Nanjing, which was patronized by Xuhuacheng 徐化成, the Left Provincial Administration Commissioner of Henan (Henan zuobuzhengshi 河南左布政使) (

Zhou 2021, p. 264).

In the spring of the 13th year of the Kangxi reign (1674), Azi Jinwu 阿字今無, the abbot of Haizhuang Monastery (Haizhuangsi 海幢寺) in Guangzhou, temporarily resided in Nanjing and requested the printing of the

Nanzang, subsequently returning south with a printed copy at the end of the same year (

Azi 2017, p. 251).

In the 14th year of the Kangxi reign (1675), Guoyifeng 郭一鳳, the Assistant Prefect (Tongpan 通判) of Ningbo Prefecture, patronized a copy of the

Nanzang and bestowed it on Tiantong Monastery (Tiantongsi 天童寺) (

Dejie 2006, pp. 136–37).

In the 23rd year of the Kangxi reign (1684), Yu’e Zhaoyu 與峨照裕 of Fuhu Monastery (Fuhusi 伏虎寺) at E’mei Mountain went to Nanjing and brought back a printed copy of the

Nanzang (

Xu 2006, p. 248).

During the reign of Emperor Yongzheng, Zhaoxiu 照秀 and Zhaoding 照鼎 of Dinghui Monastery (Dinghuisi 定慧寺) in Yulin county printed a copy of the

Nanzang in Nanjing, a portion of which has survived and is currently housed in Xingyuan library 星元圖書樓, Yulin City, Shaanxi Province (

Lang 2019).

In addition, after the 18th year of the Shunzhi reign (1661), Jinshan Monastery (Jinshansi 金山寺) in Quanzhou, Guangxi, had a printed copy of the

Nanzang, most of which also survived and is currently housed in the Ningwu county Exhibition Hall 寧武縣文物館 (

Li and He 2003, p. 432).

Based on the aforementioned descriptions, we constructed a table named “the Printing of the

Nanzang in the Early Qing Dynasty” (see

Appendix B).

Although additional materials may exist, preliminary analysis can be conducted based on the currently available corpus. As listed in “Jinling yinzang xu”, the patrons of printing the Nanzang for Guangji Monastery included twenty officials and four lay Buddhists. Judging from the source of patronage, at least four printed copies of the Nanzang were patronized vigorously by officials of the Qing Imperial Court.

After the success of printing the

Nanzang, construction soon began at the monasteries that were to house the Buddhist Canon. Weilin Daopei 為霖道霈, the new abbot of Yongquan Monastery, instructed monks to solicit donations to build a canon-storing pavilion, which started being built at the end of the 16th year of the Shunzhi reign and was completed the following fall (

Huang 2006, p. 543). The Great-Canon-storing Pavilion of Guangji Monastery, of which Emperor Shunzhi had heard, was constructed by Hengming in the 2nd year of the Kangxi reign (1663). Its title was written by Shenquan 沈荃, the former Junior Compiler in the Historiography Academy (Hanlin guoshiyuan bianxiu 翰林國史院編修) (

Tianfu 2006, pp. 62–63, 130). The reconstruction of the canon-storing pavilion of Xiangguo Monastery was led by Lang Tingxiang 郎廷相, Grand Coordinator in Henan (Henan xunfu 河南巡撫), in the 10th year of the Kangxi reign. Chen Weisong 陳維崧 composed a subscription letter, “Xiangguosi chongjian cangjingge mushu 相國寺重建藏經閣募疏”, to solicit funds (

W. Chen 2010, p. 453). The canon-storing pavilion of Haizhuang Monastery started construction, which was completed in the 17th year of the Kangxi reign (1678). Wangling 王令, the Surveillance Commissioner in Guangdong (Guangdong anchashi 廣東按察使), composed a subscription letter to solicit funds and led the construction (

Zhou 2018, p. 207). It can be observed from these cases that the construction of the canon-storing pavilions of the Guangji, Xiangguo, and Haizhuang monasteries also gained strong support from the official government of the Qing Dynasty.

The reason why Qing officials vigorously patronized the printing of the Nanzang and the building of canon-storing pavilions was pointed out by Zhou Tiancheng, the Imperial Commissioner. He argued that from the perspective of the Imperial Court, the governance of a country and the stabilization of a society could benefit from activities that resulted from the printing of the Nanzang. A Buddhist Canon stored in a temple is an object to be worshipped (gongfeng 供奉) rather than to be read by the general public. The public reveres this monumental canon through ritual worship and makes donations for its preservation, cultivating virtue in a religious atmosphere. As appointees of the new regime, regional officials in the early Qing Dynasty needed to deliberate carefully on how the local community could be engaged with, particularly with respect to those who retained memories of the Manchu conquest. At that moment, religion functioned as a trans-dynastic medium capable of facilitating communication between the two parties. The regional officials supported the Nanzang project, an action that perpetuated the local community’s mnemonic and emotional connections to the Buddhist canon of the preceding dynasty. Consequently, the political tensions between the old and new regimes could be relaxed in the worship of the Nanzang. In fact, the dynastic transition remained an abstract concern for the general public, while ritual worship constituted their vital daily activities, through which regional officials could exert subtle governance. Evidently, regional officials’ support for the Nanzang project can be deemed as a political strategy that allowed the new regime to stabilize local social order.

“Jinling yin

zang xu” also reflects that Emperor Shunzhi, through top-down patronage of Buddhist Dharma, guided popular devotion toward moral cultivation, thereby fostering a socioreligious environment of peace and harmony (

Tianfu 2006, pp. 178–79). Buddhism advocates doctrinal principles, such as wholehearted commitment to moral cultivation, compassion in the heart, karmic retribution, etc. Under the enlightenment and guidance of Dharma, the public can realize good and evil, as well as karma, and they subsequently pursue virtue during their daily lives, which is an act that the laws and rewards of the imperial court cannot achieve. This is particularly essential for the governance of the new dynasty. The reasons for Han Buddhism’s propagation were twofold; it was necessary for the public to address their fundamental concerns regarding life, and it was a necessary tool used by the Qing Dynasty to govern Han Chinese society. Objectively, Buddhism, transcending the change of dynasties, contributed to the establishment of common beliefs in the ruling class and the public.

The Qing Court officers’ support of the printing of the Nanzang and the construction of canon-storing pavilions shows that the preservation and dissemination of the Nanzang transcended dynasties during the Ming–Qing transition, forming a bridge connecting the Ming and Qing Dynasties. While the officers’ purpose of supporting the printing and storage of the Nanzang was to stabilize local morale and cultivate a culture of philanthropy, the monks’ purpose of devoting to the printing and storage of the Nanzang was to resume the dissemination of Dharma and revitalize Buddhist teachings in the aftermath of war. The cultural program of the Nangzang comprised favorable cooperation between civil and official sectors, further providing consensus among disparate political factions.

7. Conclusions

After the establishment of the Qing Dynasty, demand for the Nanzang still existed. From the case of Hengming’s successful printing of the Nanzang, we learn that regulations for requesting the printing of the Nanzang had not been enacted at the inception of the Qing Dynasty, when the Thirteen Yamen became responsible for this undertaking. The Personnel Department managed the woodblocks of the Nanzang, while the chief of the Jiangning Weaving Bureau, who was dispatched from the Thirteen Yamen, oversaw the actual printing process. By employing this method, the inner court addressed the administrative gap that had meant the woodblocks of the Nanzang remained in Nanjing without specialized official oversight.

Following the transfer of the Nanzang management jurisdiction from Nanjing back to Beijing, monasteries maintaining close relations with the inner court enjoyed distinct privileges with respect to the Nanzang’s printing. During the late Ming to early Qing era, Guangji Monastery and eunuchs in the inner court sustained close relationships. It is highly likely that Hengming made use of Guangji Monastery’s ties with the former Ming eunuchs in the Qing Palace, such as Cao Huachun and Ma Hualong, in order to obtain official support. More significantly, Cao Huachun’s position as a keeper of imperial brushes in the Thirteen Yamen allowed him to provide direct support for Hengming’s printing request.

In addition, regarding the case that Wudenghuiyuan Zuanxu and Miyun Yuanwu Chanshi Yulu were canonized into the Nanzang by imperial decree, it can be concluded that the Nanzang was one of the Imperial Buddhist Canons in the Shunzhi Reign. The involvement of the Thirteen Yamen in the printing of the Nanzang implicitly embodied the imperial order. The Shunzhi Court inherited the Nanzang from its Ming predecessor and recognized it as an Imperial Buddhist Canon rather than a private one. Through the lens of the Nanzang’s printing during the Ming–Qing transition, this study interpreted how “the Qing Dynasty inherited the institutional framework of the Ming 清承明制”.

Various regions during the early Qing Dynasty requested the printing of the Nanzang. A portion of these requests originated from the Qing officials’ proposals. The Qing officials’ support of the printing of the Nanzang and the construction of canon-storing pavilions functioned not only as tools for public moral edification and social stabilization but also as a strategy to assert their administrative presence in local society.

Therefore, this study reveals that the preservation and dissemination of the Nanzang, transcending the change of dynasties, continued into the early Qing Dynasty. Fortunately, quite a few printed Qing Dynasty editions of the Nanzang are now housed in libraries, temples, and museums, providing materials for research on this topic.