1. Setting the Framework

Religious diversity is a widespread phenomenon in contemporary societies. Census data and scientific research indicate the increasing pluralization of religious affiliations in these societies. Whether due to the greater migratory flows or due to the dynamics of the religious field itself, there is a plethora of empirical evidence that reflects the greater heterogeneity of religious identities and greater visibility of various religious expressions in the public space.

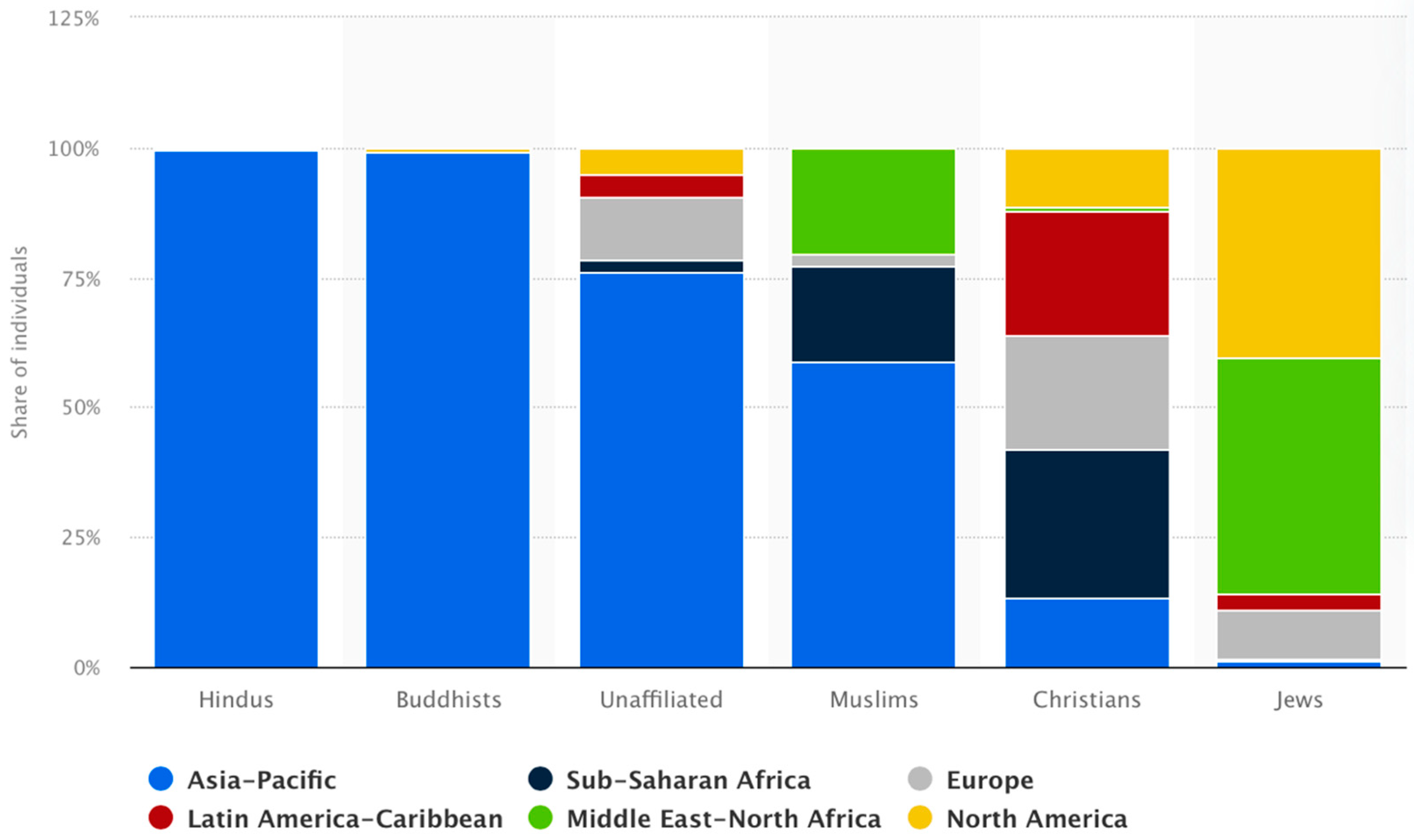

Although Christianity remains the majority religion in Europe, America, Oceania and sub-Saharan Africa, in recent decades, there has been not only a process of diversification in terms of religious affiliations within Christianity itself (for example, evangelical growth in Latin America), but also an increase in followers of Islam in Europe and in the religiously unaffiliated in the Western world [

Figure 1].

According to a study carried out by the

Pew Research Center (

2015), the trend toward religious pluralization in Europe will be consolidated by 2050, taking into account the fertility rate of people belonging different religions, age differences, migratory movements and flows from one religion to another or to none [

Figure 2].

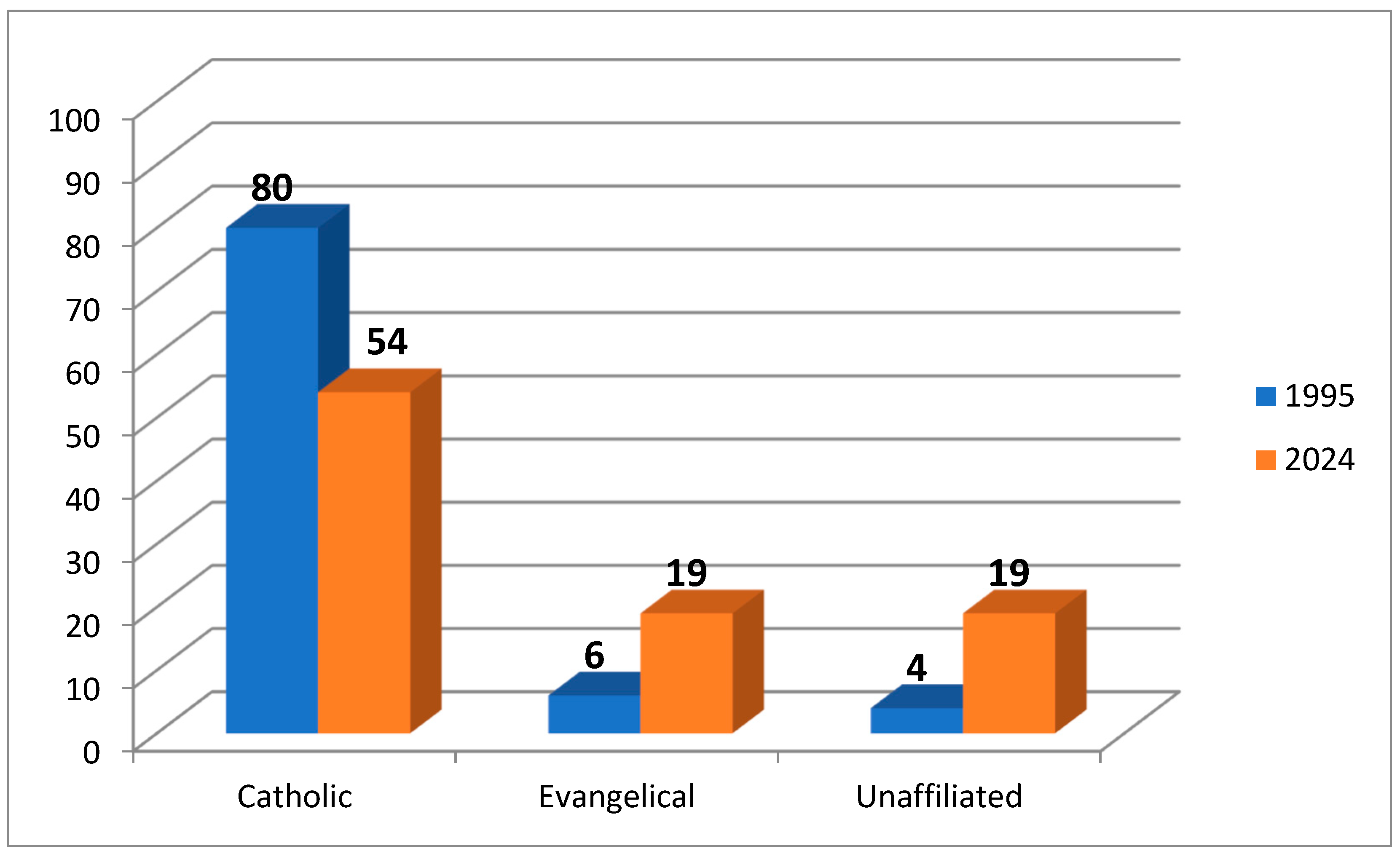

A diachronic analysis of the data collected by Latinobarometro in Latin America reflects the magnitude of changes in religious affiliations. In thirty years, Catholicism has lost 32.5% of its religious affiliations, while religiously unaffiliated communities and the evangelical population have grown by 375% and 217%, respectively, in the same period [

Figure 3].

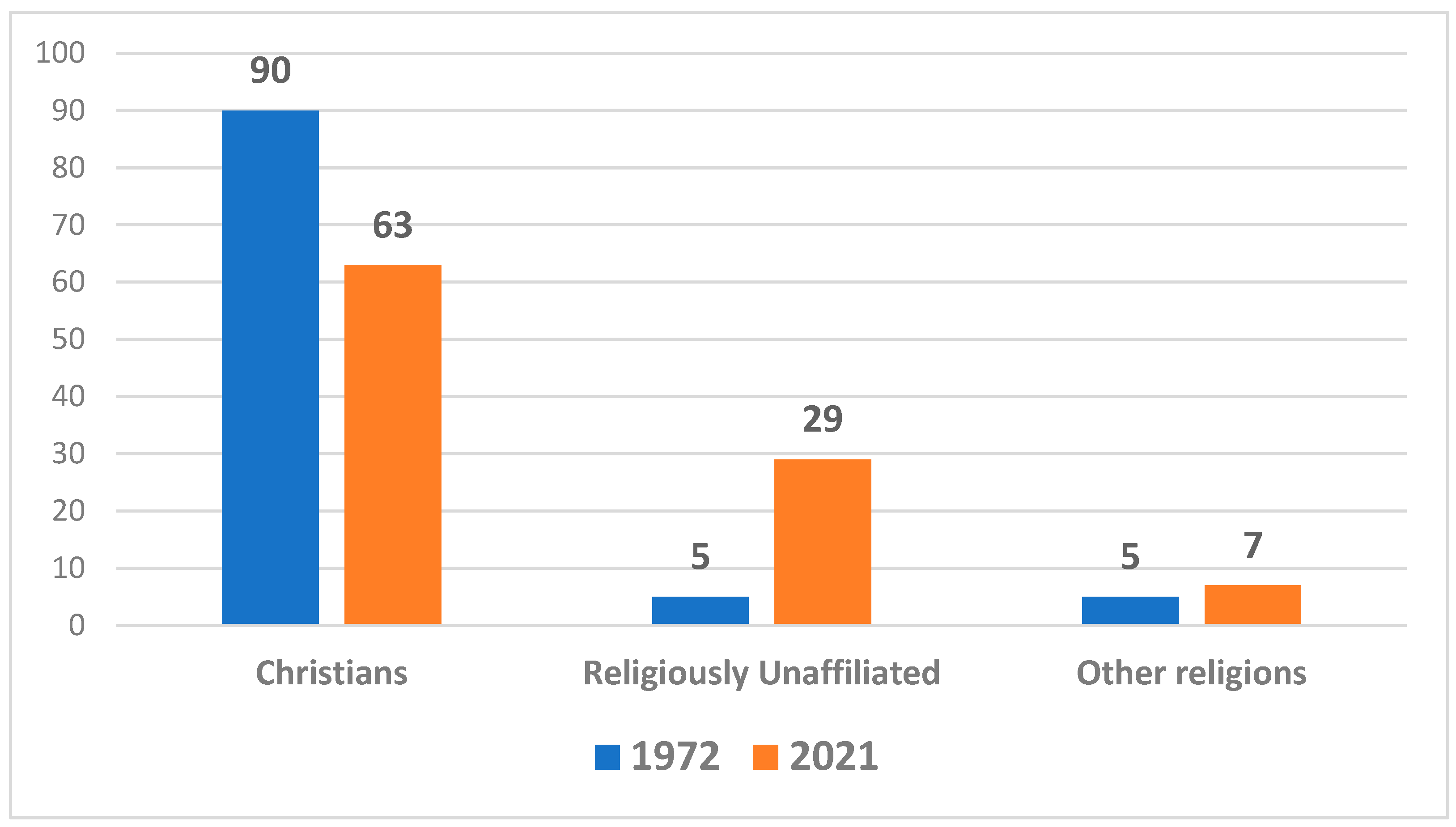

In the United States, “the change in America’s religious composition is largely the result of large numbers of adults switching out of the religion in which they were raised to become religiously unaffiliated” (

Pew Research Center 2022). The religiously unaffiliated grew by 480% over half a century [

Figure 4].

This scenario challenges the States in their policies to manage requests dealing with religious affairs, from building a new church, mosque or temple, to introducing special dietary requirements in public schools, taking into account religious identities from those in jail to priests, imams or monks, allowing religious organizations to use public spaces for religious rites, etc.

2. Changes and Continuities in a Multi-Religious World

The questions that motivated us to organize this Special Issue are centered on how the process of regulating religion is configured in a context of greater diversity, and on considering what the responses are in the state management of religious diversity in different latitudes, considering the historical, political, cultural and religious particularities in each place on the map. The call “Management of religious diversity. Comparing and contrasting experiences across the world” was aimed at encouraging reflections that derive from research at the local level, because it is here where the processes of regulating religion can materialize and the range of interactions between state agents and religious actors are reflected.

Although the regulation of religious phenomena by state agencies is not new—historically, the State has intervened by reinforcing asymmetries within the religious space, with the consequent formation of dominant and subordinate positions (

Giumbelli 2002)—the reconfiguration of religious identities and beliefs has challenged the traditional logic of managing religious diversity. The dynamism and visibility of new religious actors redefines the terms of otherness by imposing citizenship conditions and demanding state recognition.

Governance and regulation are two interrelated concepts that refer to different analytical approaches. The governance of religious diversity requires a multidimensional approach that is legal, institutional and, at the same time, informal and interpersonal in everyday territorial life. It involves the observance of state management in different areas of social life. It also encompasses the relationship between religious organizations and the functioning of chaplaincies in the armed forces and security forces, including the teaching of religion in the educational system and the ways of processing the diversity of beliefs in the health field (abortion, euthanasia, dignified death, etc.).

We can anticipate that the regulation of religion is not limited only to state action. And it does not occur primarily at the national level. Society, the media, and specialists also influence the regulation of religion, constructing definitions that demarcate the thresholds of religious legitimacy. From this perspective, regulation goes far beyond the normative framework. It reflects “

a set of mechanisms that establish the place of the ‘religious’ in a social formation” (

Giumbelli 2016, p. 17). What are these mechanisms? How are they established in each historical context? The exploration of these questions leads us to a fertile sociological field for empirical research and theoretical stakes.

We start here from a certain premise: we subscribe to the idea of a relational perspective. We ask who and in what way the religious actors themselves participate in the definition and redefinition of the state regulation of religion. We are not seduced by unidirectional and deterministic perspectives, in which social actors are passive recipients of state actions. On the contrary, it seems more appropriate to contemplate this relational network of exchanges and incidences from one to another, without ignoring the correlations of force and the different capacities of gravitation of each religious actor, or the legal framework that defines the field of action and the conditions of possibility.

3. Differences Across the Atlantic: The European Side

The management of religious diversity in Europe necessarily involves analyzing the relationships between state administrations and the range of organizations related to migrant communities, especially those which are linked to Islam.

As Ricucci has pointed out (2021), despite claims of increasing religious pluralism, research in Europe has focused on the growing Muslim presence (Cesari 214;

Bolden and Kymlicka 2016), observing with examining different points of view: Beliefs and practice, the hoped-for society (secular versus Islamic), the definition of identity (religious, Italian, cosmopolitan), orientations in terms of children’s education and mixed marriages, the demands of different European societies (recognition of festivals, and religious education in schools). In addition, attention to the religious variable is often linked to attention to work (are Muslims discriminated against in terms of access to the labor market compared to those of other religious affiliations?), school (does the increase in Muslim students lead to demands for secularization and changes in education?), timetables and spaces in the city, specific dietary requirements, and places of worship and burial (

Ferrari 2016).

At the same time, immigration countries in Europe are confronted with a change in their immigrant populations: thanks to waves of migration from Central and Eastern Europe, an increasing number of Catholics—and other Christians—can be seen on the migration front (

Hagan and Ebaugh 2003). On the other hand, the ethnic–religious composition is being reshaped by an influx of asylum seekers. In a more pluralistic religious scenario, the almost exclusive focus on the Islamic component of migration has meant that the increase in the Christian component in the wake of immigration from Eastern Europe or South America has not been investigated, and studies on other religious organizations are scarcely carried out (

Byrnes and Katzenstein 2005;

Furseth et al. 2014;

Butticci 2016).

The presence of Islam reflects challenges in religious integration, but also cultural and migratory ones (

Pace and Da Silva Moreira 2018). In this sense, recognition policies are permeated by their multidimensionality. The interfaith councils that the States have established in the continent, with the participation of representatives of various religions, are, undoubtedly, devices for regulating religion. Insights into their participants and those who have been excluded tell us about the actors of interlocution who are legitimized by the State, those who are not, and, ultimately, the scope of state recognition of religious minorities (

Martínez Ariño 2016).

At the national level, it is easy to observe the problems and internal tensions experienced by various followers of Islam and the political stalemate when it comes to an issue that touches the exposed nerve of identity. At the local level, on the other hand, the concrete demands of Muslim communities are weighed up and discussed, and become the subject of political and administrative action.

The comparison between the central level, which issues general directives, draws up fact-finding documents and sets up consultative bodies, and the local level, which intervenes, is part of the great dialectic that defines the entire integration process in several Southern European countries, and religious integration is one of the most sensitive issues (

Ricucci 2021).

The local level is therefore the privileged observatory from which to see how Islam is governed and if/how it changes in the transition from the first to the second generation of immigrants. At the local level, one can analyze the specific requests for recognition that Muslims make to public institutions in order to protect the culture to which they belong and their life practices.

There are three tricky problems in this debate:

1. Representation. Several authors (

Di Stasio et al. 2021;

Fox 2019) emphasize how important it is for the State and the authorities to have interlocutors who represent and communicate the needs, especially the cultural needs, of their members. It is crucial to understand “who represents whom”. It is not easy to understand the true meaning of religious associations and their connection to the whole community of believers, especially at the local level, where negotiations take place in a climate of increasing competition between civil society organizations for increasingly scarce public resources. Diversity, historical presence, diffusion in the socio-economic fabric of different contexts and active participation in cultural and charitable initiatives promoted by institutions and associations help to ensure that the demands of Muslims are heard, even if they are not officially represented, unless they have European citizenship. However, there is also an informal side to representation, reflected in the promotion of forms of organization closer to the public sphere: from debates in neighborhoods to community meetings, and from the association of natives and immigrants to relations with “interest groups”.

2. Religious freedom. The debate is wide open and belongs in the realm of lawyers. It would be interesting to show the social implications of these considerations. Both are part of the arguments with which citizens’ committees, political representatives and parties react both to the free profession of faith and to the call for the public practice of religion (just think of the polemic over the provision of premises for the festival at the end of Rhamadan). In the eyes of these groups, religious freedom is linked to the country’s religious identity—an identity that is questioned by Muslims—and should therefore be restricted; a public referendum should also be held on the construction of places of worship (

Brescaya et al. 2021).

3. “Immigrated” places of worship. It proves difficult to get rid of the label. For the first generations, the connection is clear because they have it in the back of their minds as it influences their appeals for recognition. For the second generation, born and living in Italy, the matter becomes a paradox: although they are not migrants themselves, they are considered (and sometimes treated) such. The Muslim–foreigner binomial leads the public debate on certain issues (e.g., the ceding of cemetery plots) of the general immigration debate: employment competition, welfare forecasts, and social assistance guarantees. In other words, there is a cognitive shift that revives the position of those who want to defend, with all their might, the national identity as monolithic and once and for all taken for granted, and who see Muslims in particular as unwelcome guests (even if they are European citizens) who should be sent home (

Eurostat 2024).

4. The Other Side of the Atlantic—The Strong Knot Between Religion and Politics

In Latin America, it is not possible to understand this relational dynamic without considering the relationship between religion and politics and what we have called ‘subsidiary laicity’ (

Esquivel 2017). The State’s management model that challenges religious groups as legitimate spaces for the implementation of public policies has not lost its validity and is rooted in political culture. For decades, Catholicism and its network of parishes and territorial organizations were the exclusive interlocutors; the growth and visibility of evangelicals in the territory in recent years has not undermined the foundations of this relational format; it has only strengthened that muscle, diversifying the exchange and complementarity with other actors. The growing negotiation that evangelical organizations engage in with state administrations shows new configurations of these ties between the political and the religious and, ultimately, the widening of the legitimized margins for the action of non-majority religious groups.

The regulatory framework is another dimension to consider. The legal system is different in each country, even contrasting in the same region, due to the historical and political configurations of each nation. The existence of a state register of worship is a central element of the process of regulating religion, not only because in some cases it is differential and obligatory (in Argentina, for example, Catholicism does not need to be registered, while other religions must be as a precondition for action), but because it formats, in some sense, a model of a centralized and hierarchical religious institution.

When a decision is made to erect a monument for the Bible in a central location in a Latin American city, there is an underlying synthesis of the regulatory process at the local level. The actions of certain religious actors promoting this initiative are condensed, translated into an ordinance that crystallizes the influence of these religious actors, and, ultimately, the State’s positioning in the public space, validating an icon of a religion or of some religions over the symbols of others. Actors learn and accumulate knowledge about the procedures required to be protagonists of the regulatory process.

In short, legal recognition is not alien to the menu of activities offered by state actors in their relationship with religious referents in the territory. Here, there is an interesting point: the vocation to register and the vocation to be registered as a dialectic between recognition and social legitimation. It is clear that it is not a phenomenon that reflects the actions of all religious groups; rather, the demands of religious organizations are more about the state recognition of their religious organization than about eliminating the obligation of registration.

5. Transversal Traits and Issues Beyond the Socio-Historical–Cultural Contexts

Delving into the regulation of religion, some economic tools present heuristic potential for thinking about the interrelations between state and religious actors.

Although the theory of regulation initially drew upon Marxism, it developed a novel conceptual framework as an institutional model of the State within the capitalist system. The idea of regulation is associated with the imperative to guarantee universal access to resources, intervening in excessive competition and the so-called “failures” of the market (

Rivera Urrutia 2004). These are discussions that do not lose validity in contemporary agendas.

There are also deterministic and unidirectional perspectives that consider regulation as a power device constructed by the State, and others with relational approaches which focus on the social nature of regulation and, therefore, on its transformations based on the dynamics of the relations between the State and the organizations and actors of civil society at each historical moment. Logically, this theory (Robert Boyer, Michel Aglietta and Alan Lipietz are some of its references) is applied in the field of economics and refers to the close link between regulation and the accumulation regime.

One of them, Alan Lipietz, risks a definition of regulation that we can assume to analyze the functioning between the State and religious groups. He defines it as “

the set of institutional forms, networks, explicit or implicit norms, which ensure the compatibility of behaviours within the framework of an accumulation regime, in accordance with the state of social relations, through the contradictions and the conflictual nature of the relations between agents and social groups” (

Lipietz 1987, p. 82).

The regulation then contemplates a normative framework, a minimum repertoire of shared values (clearly, the valuation of religious diversity and the paradigm of coexistence rather than tolerance represent this threshold of common values), commitments assumed by the agents themselves and, at the same time, contradictions and conflicts due to divergent interests as well (

Hernández and Doncel Ramallo 2020).

Addressing regulation as a dynamic and relational construction and not merely as a power device of the State guides us to identify those spaces of interaction between the State and religious groups as far as the aspects of state regulation are concerned. It encourages us to think of the State as a field of dispute in which agents, with different capacities of influence, try to shape and format the devices for regulation. The councils for dialog or religious diversity that have been created in different countries in Europe and Latin America are emerging instances in which, in some sense, the mechanisms of regulation are put into play. Which actors are called upon and which actors participate in these instances also tell us about the scope of the management of religious diversity.

Since regulation, almost like an imperfect puzzle, attempts to make interests that often do not coincide fit together, and, at the same time, harmonize them with the legal framework and the axiological corpus, it is evident that it is much more than a mere state intervention. Instability is constitutive of regulation, Jessop warns us, as long as we conceive of regulation as a space of confluence of diverse interests that, in turn, vary according to the agendas of the State and religious groups. The channeling of the evangelical demand to equate Catholic chaplaincies in the security forces with evangelical chaplaincies in some Latin American countries, for example, has to do with this instability, the product of the permanent negotiation between religious actors and state agents.

However, at the same time, regulation with its formal and informal norms (legislations and municipal ordinances) contributes to the accumulation of those who manage state resources and the main beneficiaries of those provisions. Beyond the relational dialectic, as in the economy, there is also an asymmetric distribution of power in the religious field that allows for the consolidation of hegemonic groups that we cannot ignore, given that regulation generally tends to reinforce this asymmetry. The directionality of regulation is undoubtedly permeated by the power relations within the religious field. There is a kind of

“strategic selectivity structurally inscribed” (

Jessop 2008, p. 46) by the State, whether due to the historical prominence of certain religious institutions or due to the processes of religious socialization that state agents go through. Therefore, distancing ourselves from the deterministic and unidirectional perspective of state regulation does not imply a naive view in which the State is an empty space in which the actors are on an equal footing and agree on the meaning and rules of regulation.

The relational analytical viewpoint involves a double register: the observation of how the State models and regulates, and, in turn, how the intervening actors influence this modeling and regulation. We must also point out that the mechanisms of regulation and even this strategic selectivity are not ahistorical or invariable; they transmute according to the social dynamics and power relations of each historical moment. From this perspective, we must comprehend the models of management of religious diversity as a “negotiated order” (

García Canclini 1995): temporary and changing, With structural conditions determined by the legal framework and certain principles rooted in the dominant political cultures, but at the same time, permeable to the transformations of each political and social context.

To make matters even more complex, state regulation is not necessarily identical at THE national, provincial and municipal levels. Although they are not contradictory, the norms, the repertoire of values and the commitments do not always coincide. Effectively, this is because the actors’ capacities to influence differ according to the levels of state we are considering. This statement does not cause us to lose sight of the fact that regulatory modalities at higher levels have greater influence. A national law, logically, has an impact at the provincial and municipal levels.

If we recognize that the instruments of state regulation do not determine but condition religious accumulation, we must problematize the regulation process sociologically. As a research agenda, we must observe who the leading actors that influence regulation at each historical moment are, which actors are in a position of subordination, what variations or alterations are noted from a diachronic perspective, what the interests that the different religious actors put on the table are, which of these interests manage to be channeled and which are left behind, what normative devices are part of the regulatory spectrum and how the principle of regulation is materialized in public management acts. This comprehensive analysis provides us with powerful evidence to understand the scope of the recognition of religious diversity in a given context.

The theory of regulation also refers to the design of incentives, again in the economic sphere, to stimulate the efficiency and productivity of companies. It is worth asking, without falling into reductionism, what these incentives would be in the religious field. The creation of state offices for religious affairs in Mexico, Chile, Colombia and Argentina as interfaces for recognition and integration appears to be a powerful device, although it is also in many cases reserved by some religious groups.

Other authors, such as Viscusi, Vernon and Harrington, critics of the idea of regulation, perhaps from a more deterministic perspective, maintain that it is a state imposition to restrict the freedom of action of agents. It is interesting to delve deeper into this line of argument, because it is integral to a central question. With the insignia of regulation, does the State guarantee rights or reduce freedoms?

The truth is that, at its core, regulation brings into debate the relationships between the State, institutions and individual, particularly for a state that is not a univocal entity, that is not neutral and that shows capillarity and permeability to the action capacities of the groups and actors with which it interacts.

6. An Attempt to Grasp the Topic from Local and National Experiences

In this Special Issue, we want to discuss how and to what extents the increasing religious pluralism requires states, at the national or—more frequently—at local levels to rethink the set of governmental devices, legal, symbolic, and practical, that public authorities put into play in their relationship with religious institutions.

It is interesting to reflect on the experiences of managing religious diversity in the institutional relationship between local/national administrations and religious organizations, as well as in the educational, health, penitentiary and labor spheres.

This analytical strategy involves the regulatory framework, the identification of leading institutional and religious actors, the spaces in which the management of religious diversity is condensed (schools, hospitals, prisons, public spaces, and the media) and the public practices and policies themselves in religious diversity management.

This cross-sectional and comparative analysis will allow us to not only build a situation statement on the subject in question, but also to identify good state practices for the integration of religious minorities.

Despite the emerging publications in recent times on the pluralization of the religious field, there is no bibliography that brings together empirical and comparative studies on the management of religious diversity.

The confluence of the two co-editors in this proposal is the result of a joint project on “differences and similarities in the public management of religious diversity in Argentina and Italy”. It is a comparative study on the policies of recognition of religious minorities, funded by the Italian University Consortium for Argentina (CUIA, Italy) and the National Council of Scientific and Technical Research (CONICET, Argentina).

In The Regulation of Religion through National Normative Frameworks: A Comparative Analysis between Italy and Argentina, Luca Bossi and María Pilar García Bossio comparatively analyze the regulation of religion in Italy and Argentina from a legal perspective, focusing on equal or differentiated treatment by the State. The authors note dissimilar scenarios of religious governance, despite a common Catholic matrix.

The article by Gabriela Irrazábal and Ana Lucía Olmos Álvarez, entitled Spiritual Articulation and Conscientious Objection: Dynamics of Religious Diversity Management in Healthcare Practices in Argentina, addresses the links between individual beliefs and practices in the health field as a novel strategy for analyzing the management of religious diversity. They warn about the plurality of worldviews among both professionals and “users” of the health system and the need to design inclusive models on health, illness and well-being.

In We are not one, we are legion. Secular state in Mexico, local dynamics of a federal issue, Felipe Gaytán Alcalá warns about the growing presence of churches in public spaces at the local level and analyses their implications for the management of secularism by subnational governments. In this way, the author delves into eight subnational state administrations in order to characterize the legal and political transformations and the new governance frameworks.

Nelson Marín Alarcón and Luis Bahamondes González focus on the management of religious diversity at the municipal level in Chile. In “Management of religious diversity in Chile: Experiences from local governments”, they take as a point of reference the promulgation of the 1999 Cults Law and scrutinize the daily functioning of the Municipal Offices of Religious Affairs. The authors pay attention to the tensions emerging from the greater incidence of evangelical groups.

Mariela Mosqueira and Marcos Carbonelli go beyond the legal framework to analyze the state management of religion at the local and intermediate levels in the province of Buenos Aires, Argentina. In Religious governance in interaction. A network study on the state management of religion in Buenos Aires, the authors undertake a network analysis based on the interactions between the directors of religious affairs at the local and provincial levels, as well as the profile of the political decision-makers.

Javad Fakhkhar Toosi explores the compatibility of liberal citizenship with Twelver Shia jurisprudence. In Liberal Citizenship Through the Prism of Shia Jurisprudence: Embracing Fundamental over Partial Solutions, the author analyses whether it is possible to harmonize liberal citizenship with Islamic jurisprudence, through the lens of Shia legal thought. The article highlights the theories that refer to the acceptance of laws from non-Islamic states and the circumvention of potential conflicts with liberal citizenship in the absence of the twelfth Imam.

From a phenomenological perspective, in From Existence to Being: Reflections on the Transformation of Personal Identity Through Confrontation with Cultural, Religious, and Spiritual Diversity, Martin Dojčár and Rastislav Nemec explore the intersections between cultural, religious, and spiritual diversity in order to analyze the transformations of individual identities. They delve into the philosophical foundations for understanding the existential experience of the “unknown”.

In conclusion, this Special Issue aims to reflect on the scope of state regulation, the logic that surrounds it and the impact it generates on society. And this analytical approach includes the religious dimension but also transcends it because, ultimately, it invites an analysis of the State, power and the organizations—in this case religious—that interact with it.