Abstract

This paper examines local knowledge, perceptions, and responses to changing climes in the Trans-Himalayan region of Dolpa in Nepal. Rooted within the environmental humanities and shaped by emerging understandings of faith-based ecospirituality, our research partnership focuses on the experiences of the indigenous Tarali Magar people of Gumbatara and neighbouring Shaharatara in the Tichurong valley. Through place-based engagements and drawing on various disciplinary threads and intellectual traditions, we review the effects of changing cultural, climatic, and ritual patterns on the lives and livelihoods of the Tarali Magar community. We explore how (i) agricultural practices are changing and adapting in response to wider systemic transformations; (ii) in what ways physical changes in the weather, clime and climate are experienced and imagined by Taralis through the lens of the Tarali concepts of nham (weather) and sameu (time); and (iii) local knowledge and embodied understandings about the natural and cultural worlds are embedded within Tarali spiritual traditions and religious worldviews. In reckoning with shifts in ecological patterns that disrupt long-standing agricultural practices and the cultural and religious knowledge systems that guide them, we demonstrate that Taralis are indigenous environmental humanists and empirical scientists. Through our study, we uplift culturally grounded, location-specific religious practices in the Tichurong valley and show how members of the Tarali community are contributing to global imaginaries for sustainable futures in our more-than-human world.

1. Positionalities and Relationalities

Before we introduce the reader to our project, we must introduce ourselves to the reader and outline the ethical and relational basis of our collaboration. In ways that resonate with us, Chao and Enari model how “imagining climate change reflexively … demands a shift away from the positioning of Indigenous peoples as “research-subjects” and instead as joint producers of knowledge” (Chao and Enari 2021, p. 42). Considering the importance of relationships and relationality in research that engages with indigenous communities and indigenous ways of knowing, Wilson (2008) encourages scholars to center their own positionality. We accept the invitation.

Jag Bahadur Budha is an indigenous social scientist and PhD candidate from the Tarali Magar community. Budha conducted the primary ethnographic research in the Tichurong valley, and recorded, transcribed, and analyzed the conversations on which this contribution is predicated. Together with anthropologist and geographer Maya Daurio, then a PhD candidate and now a postdoctoral fellow, and anthropologist and linguist Mark Turin, an Associate Professor, the three co-authors worked together to situate Budha’s ethnographic insights in a wider theoretical and interdisciplinary frame. The dramatic ecological and political moment in which we find ourselves calls for “radical forms of imagination that are grounded in an ethos of inclusivity, participation, and humility” and for disrupting “the prevailing hegemony of secular science over other ways of knowing and being in the world” (Chao and Enari 2021, p. 34). Our contribution aims to contribute to this wider endeavor by centering indigenous ecospiritual epistemologies.

Our research design and writing process is grounded in the 4 R’s of respect, reciprocity, responsibility, and relevance, as originally outlined by Kirkness and Barnhardt (1991). These terms get to the very essence of the “collaborative, transdisciplinary, and situated thinking that we believe the planet and climate demand” (Chao and Enari 2021, p. 34) and have helped both our collaborative process of research and its output, this article. We now turn to the question of discipline and disciplinarity.

The word “discipline” exerts enormous power over our intellectual and social lives. Chao and Enari describe disciplines as “bounded and hierachised” and as manifestations of the “imperial-capitalist logic and its extractive ethos” (Chao and Enari 2021, p. 44). It is worth remembering that academic institutions are sorted by and organized into disciplines. Discipline, in both its speculative sense and in its empirical rendering, is associated with the practice of compliance with rules and behavioral codes. And at the same time, discipline hints at the use of punishment to correct disobedience and divergence. We are all, then, shaped and formed by the hegemony of discipline. Even our attempts at resistance are often disciplinary.

This contribution—and the Special Issue within which it is situated—offers us (as writers) a rare opportunity to gently “undiscipline” our thinking in ways that are generative and safe. Our goal is to be reconstituted in relation, in a more-than-human pluriverse, where we slow down enough so that we can hear the earth speak in its own voice. As the ultimate “multi-faceted problem”, the climate crisis demands a transdisciplinary response that emancipates knowledge—wherever such knowledge is located and situated—rather than simply reproducing itself through the established disciplines (Chao and Enari 2021, pp. 43–44). This article is a step towards this stated goal, showcasing how an Indigenous perspective on the climate is a critical step for realigning this area of academic inquiry.

2. Space and Place, Climate and Clime

The influential geographer and writer Yi-Fu Tuan (1977) draws a distinction between space, which he positions as abstract, and place, which entails greater specificity. What begins as undifferentiated space becomes place through our knowledge of it. This is a process of gradual meaning making, of ascribing value and specificity through location. Another way of explaining this refinement would be that place emerges from space through the engagement of our cognition and the disposition of our senses. Hubbell and Ryan offer an even simpler distillation: “space becomes place becomes home” (Hubbell and Ryan 2022, p. 75). This kind of structural comparison can also assist us in disambiguating climate and clime. Just as abstract space becomes a tangible place through “experience, memory, meaning and value” (Hubbell and Ryan 2022, p. 76), so too climate becomes clime through an analogous process of refinement and increasing specificity, as we discuss below.

Before proceeding, it is critical to establish that climate is not the same as weather. The convenient conflation of the two has been used by climate denialists who mistake (perhaps intentionally) daily variations in weather for long-term patterns in the global climate. Even though Naomi Klein helpfully reminds us that climate change has changed and is changing everything (Klein 2015), we need to move beyond pithy aphorisms like “climate is what you expect, weather is what you get” (Hulme 2009, p. 9) to arrive at more nuanced and coordinated responses. Amitav Ghosh helps us see how the climate crisis tugs at the very essence of the human condition by challenging our fixation with our own biological uniqueness. Integrating climate thinking with our shared investment in and responsibility to this earth requires a radically new posture, one grounded in humility. One way of approaching this is to think with climes.

Clime thinking is gathering momentum, thanks in large part to the foundational work of Dan Smyer Yü and Jella J.P. Wouters, who have helped to outline the analytical basis for this important intervention in two recent edited collections (2023 and 2024) that bring together rich contributions from encounters across the Himalaya, the Andes and the Arctic. The grammatical gearing of clime thinking is that it invites specificity and locality through transformations that are perceivable and observable. As Smyer Yü notes, “a clime is both a place-based embodiment and an agent of climate change” (Yü 2023, p. 8). In the same way that abstract space becomes legible place, so too intangible structures of climate change become situated and embodied when understood through locally encoded climes. In the case of Tichurong, clime is at once “geologically and ecologically concrete, terrestrially sensible, multiculturally inclusive … methodologically malleable, and fully open to affective and spiritual approaches” (Yü 2023, p. 12). Clime introduces anthropogenic agency and multipolar textuality, inviting an ecospiritual aliveness and awareness that speaks to indigenous ways of knowing that resonate with Tarali Magar realities. Or, as Wouters writes, climes are “terrestrial, affective, relational,” bringing in perspectives that are more “earth-gravitated” (Wouters 2023, p. 253). Climes emerge in “togetherness, tangles, and intertwinements” (Wouters 2023, p. 254), and like a story, they become enlivened and enacted in relation. Perhaps most importantly, climes matter. They impact how people “experience, think, and talk about … their actions and responses to climate change” (Wouters 2023, p. 256). For all of these reasons, we believe climes are both good to think with and generative to work with.

Until the emergence of clime studies, anthropological research related to climate change in Nepal mostly examined perception, knowledge, and agroecological responses to climate change in areas such as Upper Mustang, Manang, and the Everest region, respectively (Devkota 2013; Sherpa 2014; Khattri and Pandey 2021). These foundational studies are important for understanding localized responses to climate change across Nepal. A recurring theme in this earlier phase of research was the intimate relationship between religious traditions and environmental knowledge systems, a thread that more recent studies (see Dorji 2024; Yangzom and Wouters 2024, among others) have developed further. Following those who make sense of “climate-society relationships” (Chakraborty et al. 2023) and the intersection of environmental disruptions with cultural and religious narratives (Childs et al. 2021), we position our own contribution as an exploration of the specific and situated social, ecological, agrarian, and ecospiritual practices of the Tarali Magar people of Gumbatara village in the Tichurong Valley in Dolpa.

We also locate our contribution as a response to the call from (Chakraborty et al. 2021) to amplify place-based experiences of social–ecological change in the Himalaya as a way of contributing to the growing plurality of knowledge about climate and clime. We employ two concepts from the Tichurong Poike language as proxies for clime thinking and climate change, weather (nham), and time (sameu). Through these local encodings, we understand how people are experiencing and making sense of changes to their climes and climate, manifested in shifting cultural, religious, and livelihood practices.

As we show in this contribution, the terms nham and time sameu underscore the lifeworlds, values, and religious–spiritual imaginations of the Tarali people, whose ecological understandings are embedded within indigenous relationalities that connect to elevation and location. Bhutia shows how Buddhists in Sikkim incorporate their cosmologies and rituals into their understanding of how “human flourishing depends on the climate, and how other beings—including the deities and spirits of the animated landscape—are also part of this interconnected system” (Bhutia 2023, p. 123). Similarly, we make visible the local manifestations and perceptions of weather, clime, and climate change that the historically marginalized Tarali community has experienced, along with the terms that this community uses, in their own language, to refer to and decipher specific environmental changes that they experience.

The terms nham “weather” and sameu “time” are locally salient for Taralis. How time is partitioned is informed by cultural, political, symbolic, and linguistic processes within a specific community and culture (Turin and Chung 2020; Munn 1992; Morrison 2016; Natcher et al. 2007). Conceptualizations of time in Tichurong shape narrative frameworks for understanding and responding to ecological and meteorological changes. Anthropological and linguistic understandings of time reveal how impacts from changes in clime, climate, and weather change overlap with the “seasonal and everyday rhythms of communities and households” (Sørensen and Albris 2015, p. 74). As we discuss below, Tarali livelihoods are shaped by the seasons and punctuated by the sacred rituals that accompany each calendrical turn.

Anthropological, geographic, and indigenous epistemological approaches link local experiences of time (Brace and Geoghegan 2010; Murphy and Williams 2021) with attention to the material landscape (Awasis 2020, p. 832) and help to transcend the idea of a single, human-centered temporal frame (Widger and Wickramasinghe 2020; Whyte 2018). The concept of “materialist time” (Widger and Wickramasinghe 2020, p. 124) considers the role of climate and other elements enacting “a “gravitational pull” on relations in the world” (Widger and Wickramasinghe 2020, p. 137) that illuminate “human encounter[s] with geo-climatic processes” (Widger and Wickramasinghe 2020, p. 139). For Taralis, seasonal temporalities are directly related to their relationships with deities residing in specific, sacred locations who hold power and control over certain environmental conditions, such as the provision of rain. The presence and enduring power of these deities speak directly to the ecological role of religions and spiritual practices in shaping human–nature relations.

To offer some necessary background framing, since the beginning of the 21st century, climate change, as documented by the scientific community, has played an increasingly prominent role in shaping environmental conditions (Milton 2008). The change in climatic variables in our lifetimes has transformed physical aspects of the environment and has had significant cultural and social implications (Cruikshank 2001, 2005; Orlove et al. 2002; Strauss and Orlove 2003; Crate and Nuttall 2009; Orlove et al. 2008; Carey 2010, 2012; Adger et al. 2013; Dove 2014). Projections show that climate change will alter the seasonality, frequency, and amount of precipitation, accompanied by rising temperatures and increased drought around the world (Kundzewicz et al. 2008; Trenberth 2011). Social and ecological systems in the Trans-Himalayan region are no longer functioning the way they have in the past (Poudel 2018), and this region is experiencing more severe impacts than other elevations in Nepal (Upadhyay 2020). While negative impacts on Himalayan biodiversity have been well-documented (Kattel 2022; Yadav et al. 2021; Shrestha et al. 2012), scholars are now increasingly looking at how changes in temperatures and rainfall, sea-level rise, and melting glaciers and ice caps will affect settlements and agriculture (Crate and Nuttall 2009; Orlove et al. 2008; Morton 2007).

Due to Nepal’s topographical and physiographical variability, there are indications that changes in clime, climate, and weather patterns, not to mention related variations in temperature and precipitation, affect different locales heterogeneously (Shrestha and Aryal 2011; Paudel et al. 2021; Kansakar et al. 2004). While these localized impacts are difficult to capture in climate models (Talchabhadel 2021), regional climate models are being applied to provide basin-specific climate impact assessments for Nepal (Dhaubanjar et al. 2020). There is some evidence to suggest an east–west divide in Nepal in terms of precipitation changes and anomalies (Pokharel et al. 2020), with the largest variability in winter precipitation for the western and central regions of Nepal (Dawadi et al. 2023; Pandey et al. 2020). Many studies focus on the Karnali River basin, which includes Dolpa district, the site of our own research collaboration. Although for Nepal as a whole, extreme precipitation has increased significantly since the end of the 20th century—including in Western Nepal (Bohlinger and Sorteberg 2018)—the western region has also experienced a considerable decrease in seasonal mean precipitation (Pokharel et al. 2020). Nepal, and Western Nepal in particular, shows significant current and projected changes to patterns in precipitation and temperature based on the available literature. This scientifically documented and verified data reflects the increasing uncertainty and variability in certain weather patterns that have been experienced by our research participants, which affect agricultural livelihood practices and disrupt social–ecological knowledge systems.

Over the last decade, ways of knowing climate change have shifted from exclusively materially grounded approaches to more meaning-centric and symbolic approaches, through which anthropologists have become increasingly interested in the symbolic dimensions of climate change (Vedwan and Rhoades 2001; Crate 2008; Gagné 2013; Roncoli et al. 2009), including how people know and understand climate change (Hulme 2017). In a significant contribution to ethnoclimatology, Orlove et al. (2002) observed that villagers in the Peruvian and Bolivian Andes use the Pleiades constellation as the basis of ritual observation immediately after the winter solstice, forecasting the timing and quantity of rains, identifying El Niño years, and predicting the size of the harvest for the following year. Local interpretations of changes to the environment are rooted in what Berkes refers to as a “knowledge-practice-belief complexity” (Berkes 2008). Berkes shows how worldview shapes environmental perception and gives meaning to observations of the environment, religion, ethics, and more generally, belief systems, contributing to the knowledge–practice–belief complex that describes traditional knowledge. Affirming and promoting local ways of knowing the environment support a pathway for Indigenous self-determination in devising climate adaptation strategies (Whyte 2017).

3. Geographies and Seasonalities

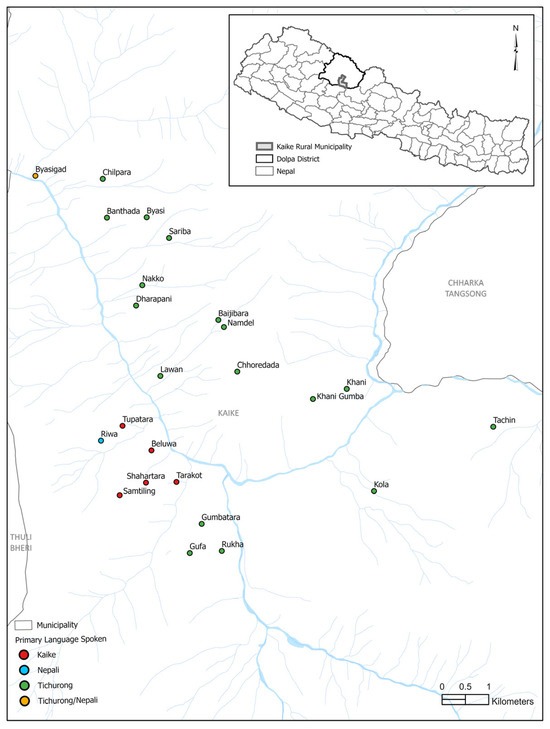

Our principal story is situated at a latitude of 28.8726 and a longitude of 82.993 in Gumbatara village of the Kaike Rural Municipality of Dolpa, which sits at an altitude of 2950 m above sea level (See Figure 1). Gumbatara is located in the foothills of Mt. Puta on a flat outcrop thought to have once been a lake. This lake also features in the origin story of the Kaike language, spoken primarily in three villages in the Tichurong valley (Fisher 1986; Daurio 2012). Gumbatara is an ethnically homogenous settlement, solely inhabited by Tarali Magar people who speak Tichurong Poike (see Budha et al. (2021) for a snapshot of this language), follow Tibetan Buddhism, and worship the local deity Chyohopata. Tarali Magars are a subgroup of one of the Indigenous nationalities of Nepal, the Magars, which comprises two other subgroups (Budha 2023). Gumbatara, along with the other twenty-three villages in the Tichurong valley, including Shaharatara, which we visit briefly below, is located within a sacred landscape. Local rituals and festivals such as Rung, Rungma, Puturungbu, and Keja are all based on the worship of local deities who reside in culturally significant geographic abodes, such as a particular tree or a glacier, as in the case of Chyohopata. These places of divine residence, encapsulating the sacred landscape of the Tichurong Valley, are both ecologically and religiously significant. Chyohopata, among the most powerful deities, resides in a glacier overlooking the Tichurong Valley for part of the year, and the melting of the glacier would both have extreme ecological consequences for Taralis and disrupt their sacred relationship with this deity. It is not a coincidence that those deities who reside in trees occupy some of the oldest or largest trees in the valley. Sacred ecologies are central to the spiritual lives of Taralis. Although our interviews and wider research took place in Gumbatara among participants who are residents of that village, we anticipate that our findings may be extrapolated to characterize experiences across the geographically distinct Tichurong valley, where many of the villages share linguistic, cultural, religious, and agricultural practices (see Fisher 1986, 2017; Budha et al. 2021; Daurio 2012).

Figure 1.

Map of the villages of the Tichurong Valley, Dolpa, Nepal. Map by Maya Daurio.

Through our ethnography, and in the context of place-based knowledge systems, we show how Taralis use nham and sameu to forecast weather patterns, plan planting and schedule harvesting, and engage in cultural and religious practices that are connected to place, seasonality, and spiritual practice. We document the ways that nham and sameu manifest in relation to Tarali agricultural livelihood practices and show how religious rituals no longer align with previous experiences and expectations. In short, our contribution speaks to the ways that Taralis are experiencing dramatic and disruptive changes to their lives and livelihoods and are drawing on faith-based environmentalisms and ecospiritual models to assist them in navigating this uncertainty as they look towards a very different future.

The lives of the Tarali Magar people of Gumbatara and Shaharatara have long followed the rhythms of four distinct seasons: spring (soeka), monsoon (yarka), autumn (tongga), and winter (kungga). Taralis depend on their highly refined agricultural livelihood systems, practices derived from deep understandings of clime, climate, and religion that are themselves calibrated to seasons, weather, and the environment. Spring, between the Nepali months of chaitra to jeth (approximately March 15 to June 15), is the primary season for preparing the hand-built, terraced agricultural fields distributed across the mountainsides surrounding Gumbatara by clearing, plowing, fertilizing, and planting crops. In late spring, usually in May, people travel to the high-altitude pastures above the village to collect yarsagumba (Ophiocordyceps sinensis), a caterpillar fungus with high cash value (Budha 2015). During the monsoon season, typically between June and September, women are especially busy weeding crops, while men have more free time on account of the highly gendered division of labor. Weeding is one among numerous tasks only performed by women, in addition to fertilizing, harvesting, and winnowing crops. The autumn months of ashoj to mangsir (approximately September 15 to December 15) are a busy time for harvesting and processing crops, followed by a period of collecting firewood and increased general leisure time in winter. The winter season starts from paush and lasts until phalgun (approximately December 15 to March 15). This is also the time when the locally significant month-long Rung festival occurs. In this way, each of the four seasons includes communal activities intricately and simultaneously linked to agriculture, livelihoods, and spirituality.

Many communities across the Hindu Kush Himalaya region revere mountains and lakes as the abodes of gods and goddesses, which Ramble refers to as a “sacred ordering of the environment” (Ramble 1995). In ways that resonate with Dorji (2024), Yangzom and Wouters (2024), and Wijunamai (2024), the same may be said for the Tarali people in the Tichurong valley, who revere the Puta glacier—visible from the valley and locally called Chyohopatai Tangra—as sacred (See Figure 2). The Taralis also venerate Sworchyung Lake, which sits at the foot of the glacier, and a powerful local deity, Chyohopata, who resides in Chyohopatai Tangra. In the Tarali imagination, Chyohopata serves as a guardian of the whole Tichurong valley, protecting its people from disease, famine, and disaster. Tarali communities perform a month-long religious festival called Rung in the winter and one called Rungma in the spring as a form of worship for Chyohopata, which we explain in more detail below. In the Tarali cultural world and ecospiritual understanding, the melting of the snow of Chyohopatai Tangra will lead to the end of the world. Such conceptions are common among Bön and Tibetan Buddhist communities who live across the Himalayan region. Understandings of the environment and rituals conducted on behalf of maintaining beneficial relationships with deities residing in sacred places constitute what Huber and Pedersen refer to as the “moral climate” (Huber and Pedersen 1997). A moral and culturally coded engagement with understandings of and adaptation to risk is rooted in both Bön and Buddhist religious traditions and worldviews and has been documented across the Himalayas (Diemberger et al. 2015; Childs et al. 2021).

Figure 2.

Chyohopati Tangra (Chyopata’s yard) Puta Glacier, a residing place of local power deity Chyohopata Photo: Jag Bahadur Budha.

That the Taralis consider the glacier and its associated lake as the abode of a deity is indicative of a deep respect for and spiritual connection with their environment, which might productively be understood as an autochthonous ecospirituality. Tarali seasonality is marked through rituals dedicated to Chyohopata. The Rung festival takes place in the winter, when it is extremely cold in the Tichurong valley. To escape the harsh cold, Taralis explain that Chyohopata migrates to the lowland valleys of Nepal (Tarai), and the Rung festival is celebrated as a way to bid farewell to Chyohopata for that season. Rungma and Puturungbu are celebrated in mid-March as a way to welcome Chyohopata back. Overall, seasonality inflects Taralis’ relationships with sacred spaces and the deities who reside in important places across the landscape.

4. Kuragraphy as Method, Making, and Taking Time

Ethnographic research for this study was conducted in Gumbatara, which is also the childhood home of co-author Budha. The fieldwork for the study was carried out in May 2022. During this period, Budha interviewed twelve people. Interviews were conducted in several ways, including through Kuragraphy, key research participant interviews, and group discussions. Kuragraphy is an ethnographic research method used in the Nepalese context (see Desjarlais 2003). In Nepali, कुरा kura means “thing, matter, voice, speech, conversation, chat,” and signifies an informal conversation in a local setting. Kuragraphy was used on occasions like a haircutting ceremony and during Rungma, the spring festival. It was also a way of ascertaining how Taralis sensed changes (Desjarlais 2003) in their environment, manifested in weather and agricultural practices. We reference, for example, how some people describe that their patterns of wearing particular shoes or going barefoot at certain times of the year had been disrupted.

All those interviewed are from Gumbatara and represent diverse and distinct livelihoods, and include those working as herders, farmers, Lamas/monks, and yarsagumba collectors. Interviews were conducted and recorded in the local language, Tichurong poike, and subsequently transcribed by co-author Budha, with translations refined by co-authors Daurio and Turin. All three co-authors helped with data analysis and editing, and co-author Turin led the writing. In the context of our study, we consider that co-author Budha’s indigenous relationship to the Tichurong Valley and prior knowledge of the Tichurong Poike language were strengths in conducting ethnographic research. The idea for this research project originated with Budha’s prior communications with people about changes to the environment and weather patterns. Budha’s familiarity with local religious traditions and sacred geographies was also critical to both data collection and analysis. Our ethnographic engagement was rooted in a curiosity about perceptions and experiences of change rather than a preconceived hypothesis about what this might represent. We were interested in asking herders about access to viable pastures and assessing clime and climate change impacts on animal husbandry. From farmers, we gathered reflections on the variation in the cropping and harvesting seasons over time. Indigenous knowledge of meteorology was also documented through conversations with elders. Those who shared their local knowledge of the environment and how it is being impacted by climate change were primarily elders aged 50 years and above. They generously exchanged ideas, information, points of view, and experiences through dialogue organized among the elders themselves in collaboration with Budha.

We used an informed grounded theory approach (Themelis et al. 2023) for analysis and to identify emergent themes within the collected data to develop a framework that builds on scholarship related to clime studies, ecospirituality, and temporality. This intellectual framework emerged organically from co-author Budha’s prior communications and experiences, which led to the conceptualization of the research project, followed by Budha’s empirical observations and experiences during fieldwork in Tichurong. Our research findings were shaped by the views of our research participants and our deep reading of the associated regional literature and aligned theory.

In seeking to understand how Taralis experience the effects of climate change, we asked participants what changes they have observed in their lives. The term sameu emerged as a way of demarcating change among participants, a word that means “time” in the Tichurong language. Tapchiki sameu refers to “present time”, while tangbui sameu indicates “past time”. This particular division of time is the measure by which Taralis notice and track environmental changes in relation to their agricultural livelihoods, weather patterns, and the efficacy of religious practices and sacred rituals to ensure the right environmental conditions for planting and harvesting. Based on how changing ecological, agricultural, and weather patterns in Tichurong are conceptualized primarily in relation to time, we situate our analysis in the indigenous, geographic, and anthropological literature that explores the relationship between temporal orientations, social–ecological systems, clime thinking, and climate change (Natcher et al. 2007; DeSilvey 2012; Carlson and Tamang 2022; Yü and Wouters 2023; Wouters and Yü 2024). In this way, in alignment with a grounded theory approach, we let the emergence of the theme of Tarail temporalities in our research data guide our engagement with certain literature.

The importance of and unique relationship to time that shapes the ecospiritual existence of the Tarali people of the Tichurong valley has echoes in indigenous ways of being in other parts of the world. Based on interviews with Anishinaabe community members, for example, the geographer Sakihitowin Awasis categorizes Anishinaabe temporalities into periodicities (i.e., seasons, election cycles); timeframes (i.e., seven generations before/after the present); kinship relations (i.e., land-based sociopolitical systems vs. “hetero-nuclear” family ties); and other than human temporalities (i.e., migration or hibernation cycles) (Awasis 2020, p. 833). Indigenous philosopher Kyle Whyte refers to a “spiraling temporality” (Whyte 2018, p. 228) to describe people’s diverse experiences of time embedded “within living narratives involving our ancestors and descendants” (229). The perception, experience, and understanding of time and its relation to faith-based environmental knowledge systems are situated within Tarali cultural contexts and place-based understandings.

In the rich literature on sense of and attachment to place, a number of scholars (Berroeta et al. 2021; Crate 2021) note how environmental changes (Schlosberg et al. 2020, p. 239) can create a “temporal rupture, manifesting as dissonance between past experiences, present realities and future ideas of sociality and sense of self in place” (Askland and Bunn 2018). The Tarali people in our study describe a similar discord between their expectations and past experiences of climate and weather and what they are currently experiencing, manifested in periods of drought, untimely rainfall, and warming temperatures. These present and future uncertainties and deviations from past experiences create a sense of time out of place and place out of time, in ways that are resonant with Bird Rose’s observation that “knowledge of the changes in seasons is land-based and is owned….such knowledge rests on the relationships between the living things within a particular area” (Rose 1996, p. 58).

5. Clime Change as Time: Tangbui Sameu and Tapchiki Sameu

In contrast to other parts of Nepal, the English terms climate change and global warming and the Nepali terms मौसम परिवर्तन and जलवायु परिवर्तन, meaning “climate change”, are not commonly used by Tarali people, even in translation. Yet, the effects of changes in weather patterns, the climate, and in very local climes are felt, observed, and viscerally experienced. Taralis notice and observe changes in their environment and ecology mainly through variations in snowfall, rainfall, temperature, cropping time, and the ways in which their local weather-forecasting systems have become increasingly less reliable.

Tarali people’s perceptions of weather and climate are connected with cultural and religious understandings in ways that reflect a deep, place-based ecospiritual awareness. While Tarali people do not have an exact term for climate change, they characterize and refer to changes to their environment as sameu, understanding and categorizing these changes temporally. In speaking with people in Gumbatara, co-author Budha used the term sameu as a proxy for talking about clime and climate change because sameu was the frame through which research participants themselves described the transformations of their more-than-human world. Importantly, participants used nham, the word for “weather”—also sometimes used for “rain”—to describe changes to typical weather patterns that they previously relied upon. Participants compared “past time” tangbui sameu with “current time” tapchiki sameu, in addition to nham, to indicate the wider changes that they were experiencing in terms of clime and climate.

Our interlocutors from Gumbatara describe vividly how they experience changes in temperature. They also describe the ways in which winters are warmer than they used to be. These place-based and embodied experiences of change align with comparative evidence showing that Nepal is, overall, experiencing warming temperatures (Khadka et al. 2023; Paudel et al. 2021), a trend projected to continue into the future (Dhaubanjar et al. 2020). As one 65-year-old community member, Sukar Budha, noted:

In the past (about 20 years before), everyone had to wear docha/somba (traditional woolen shoes) during the winter. It was very difficult without docha/somba. But these days people wear open sandals even in the winter when it is snowing. These days, winters are quite a bit warmer than in the past. There was heavy snowfall in the past but now it is a little less.

These changes impact agriculture and are reflected in variations in crop sowing and crop-harvesting time. According to two women, Kali Budha and Chhiring Budha, changes in temperature have impacted the seasonal rhythms related to crop ripening and crop harvesting. Crops are now ripening an entire week earlier than in the past. Changes in wider weather patterns and local climes have had adverse effects on agriculture in terms of the production of crops, planting time, and harvesting time for proso or common millet (Panicum miliaceum, known as chinu chaamal in Nepali), buckwheat (Fagopyrum tataricum, or phapar in Nepali), and black lentils (Lens culinaris or daal makhani in Nepali), all of which are major crops in the Tichurong valley.

Proso millet and buckwheat are dietary staples in the Tichurong valley, along with a number of other crops. The diversity of crops grown across Tichurong has historically protected Taralis from losses associated with insects, weather, and disease. In their origin story explaining how so many crops came to be grown in this valley, Taralis identify nine different varieties of grains and legumes (Daurio 2009, p. 37). In the past, people could sustain themselves with these crops and even had surplus grain, which they either stored (Fisher 1986) or sold to people in Upper Dolpo. The anthropologist James Fisher, who conducted research in the Tichurong valley over the course of a year in 1968–1969, provided extensive documentation of agricultural production and trade enterprises, offering a valuable resource for measuring change over time in relation to the changes Taralis themselves have identified. In the late 1960s, Taralis produced so much grain that they had to devise multiple strategies to cope with the surplus, which included burying it, bartering or selling it for other necessary items, or engaging in long-distance trade (Fisher 1986, pp. 74–75). Grain used to be exchanged for salt brought from Tibet through Upper Dolpo, which was then used to trade for rice in the lower elevation areas of Nepal. As recently as 2008, Daurio spoke to a woman in the village of Shahartara who said she had eaten grain which was twenty years old, although she noted that storing it for two to four years was more common (Daurio 2009).

Since the year 2000, all Tarali Magar households have purchased rice from Dunai, the district headquarters and supplement their traditional diets with this crop, which is grown at lower elevations and flown into Dolpa by the Government of Nepal. Rice consumption was documented by Fisher in the late 1960s—indeed, Taralis traded salt for rice, transporting it back to Tichurong from the plains of Nepal on pack horses—and in 2008, members from each household would retrieve an allotment of rice each month provided by the World Food Programme in Dunai (Daurio 2009, p. 39). While rice has long been a food of higher status, since co-author Budha’s childhood, it is now the main grain consumed in Tichurong. The reasons for this are twofold. First, since the emergence of the cash crop yarsagumba, which is harvested in the high-altitude meadows above Tichurong at 4000–5000 m, people are not producing as many crops (Budha 2015). Crop production is both time- and labor-intensive, and planting and harvesting times are interrupted by yarsagumba harvest times. The cash generated from selling yarsagumba can be used to purchase rice in lieu of growing other grains like proso millet. Second, the increasingly unreliable timing of rainfall has made it more difficult to consistently produce enough grain. These two factors work in concert to favor rice as a food staple and not just as a special status food.

Not only has the amount of grain production changed, but planting and harvesting times are also in flux. In the past, proso millet and black lentils were planted together on the seventh and eighth of the month of baishakh in the Nepali calendar, sometime in the latter half of April. Now, millet and lentils are planted separately. Black lentils are planted around the 15–20 of the Nepali month of asar (around the beginning of July) and harvested at the end of asoj (mid-October), while proso millet is planted around baishakh 14–15 (the beginning of May) and harvested after asoj 12 (the end of September). Lentils are now sown two months later than millet.

Buckwheat and proso millet also used to be harvested together, with buckwheat in the morning and proso millet in the afternoon. Since 2010, proso millet has been harvested a week earlier than buckwheat (in the month of asoj after the ninth day, around the latter half of September) because proso millet ripens earlier than in the past due to warmer weather conditions. There is less production of proso millet and buckwheat because the rains are not as reliable. People in Gumbatara have observed that, these days, when the crops are in need of water, there is often no rain, and that when crops do not need water, it often rains at inopportune times. Generally, the plants and crops in the Tichurong valley need rain in the middle and late spring, but disruptions to global weather patterns and local climes are making rain prediction much harder and agricultural patterns less reliable.

Since 2010, drought in the Tichurong valley has been increasingly common during periods when, in the past, it would have typically rained. Fisher reported that, during 1968–1969, it rained 98 out of 225 days during the growing season (Fisher 1986, p. 55). At that time, villages in Upper Dolpa, as well as those several miles downriver, experienced drought, causing grain deficits, but this was not the case for Tichurong. Research participants report that traditional weather patterns are less reliable and that Tichurong has been subjected to both drought and excessive rainfall. The hot sun presents an impediment to weeding crops, which used to be undertaken without shoes. In 2022, it was no longer possible to weed without shoes because the soil was too hot for bare feet, offering yet another example of how days are now warmer than in the past.

In the summer, the rains are increasingly heavy and can flood the crops. In October of 2022, Tichurong and many other parts of Nepal experienced excessive rainfall during what is normally a dry month, in the middle of the harvesting season. In the Tichurong valley, this resulted in two bridges and a school being washed away. Occurrences such as this illustrate why people feel more uncertainty around tapchiki sameu weather and are struggling to make sense of fast-changing ecological patterns.

6. Ecospiritual Embodiment: Praying for Rain While Living in Drought

Among the Aboriginal communities in Queensland, “many of the super-ordinary beings interact with people” (Rose 1996, p. 23). The same may be said of the Taralis of Tichurong, who regularly engage in the practice of asking for rain from their local deities. When there is drought in the Tichurong valley, every village appeals to the village deity, yullha, to bring rain in the valley. While the Taralis know that not everything that happens is right or good, everything that happens does have, as in other indigenous contexts, “creation as its precondition” (Rose 1996, p. 23).

The lamas of Gumbatara village travel to two lakes, Chho Phyarka and Sworchyung, where they pray and offer chinlab (a kind of medicine) and thuichyu (holy water) to the lakes. Participants report that, in their childhoods, these efforts would always bring rain. But these days, Taralis experience that when there is a drought in the village and the lamas go to pray for rain, it does not come. Thinley Lama shared the following insight:

In the past, when I was young, I used to go with my father and other lamas of the village to ask for rain at the two lakes (Chho Phayarka and Sworchung). When we prayed and offered chinlab and sacred holy water thuichhyu, it rained immediately. But these days, even when we go to ask for rain, praying and offering chinlab and thuchhyu, there is no rain. I think now the Lha ‘god’ and Lu ‘earth deities’ might be angry with us. If your internal body is dysfunctional or affected, then you become ill. Similarly, if our earth’s deities Lhalu and Siptak are polluted, they become angry and harm people by creating landslides, droughts, and famine.

Bird Rose offers a nuanced way of understanding rituals of well-being. Traditionally referred to as “increase rituals” in the anthropological literature, such practices can be better understood as being rooted in regeneration and maintenance in ways that serve to promote life, but do not promote it promiscuously (Rose 1996, p. 53). In a similar vein, focusing on west Sikkimese traditions, Bhutia outlines how “Buddhists in this region incorporate their cosmologies and rituals into their understanding of how human flourishing depends on the climate, and how other beings—including the deities and spirits of the animated landscape—are also part of this interconnected system” (Bhutia 2023, p. 123).

In the neighboring Tichurong village of Shahartara, the Tarali community worships Lachin Tanuma, a local deity located above the village in an old Himalayan Cedar (Cedrus deodara) tree (See Figure 3). When there is a drought in Shahartara village, the villagers worship Tanuma by sacrificing a goat. There is now a perception among some villagers that these rituals are no longer as effective as they used to be at bringing the rain, or as Sikkimese Buddhists might say, as a “sign that the world is out of balance” (Bhutia 2023, p. 134). As Bam Bahadur Rokaya from Tichurong reported:

Figure 3.

Lachin Tanuma is a local deity in an old Himalayan Cedar (Cedrus deodara) tree above the Shahartara village. Photo: Jag Bahadur Budha.

In the past, when there was a drought and no rain, we prayed to Lachin Tanuma. We villagers would gather at Lachin Tanuma and sacrifice a goat. Then that night it would rain. But these days, even though we worship Lachin Tanuma, there is no rain. Something has changed.

As these narratives suggest, Tarali people experience a disconnect between the ritual of praying for rain that they have always performed and the efficacy of such rituals in relieving the Tichurong valley from drought. Echoing Bhutia’s study of Sikkim, Taralis experience this imbalance to be both “material and spiritual” (Bhutia 2023, p. 134), a wider indication of non-alignment in the temporal, spiritual, and cultural dimensions.

Since 2010, Taralis have experienced that rainfall and weather have become increasingly irregular and unpredictable. Interviewees shared that, while in the past, they were able to forecast rainfall and weather, it has now become increasingly difficult to do so. Tarali people depend on adequate rainfall and snowfall at the right times for the maintenance and sustenance of their dryland agricultural livelihood systems. Taralis understand their local weather and the wider climate through diverse ecospiritual symbols and powerful locally resonant environmental indicators. Before making farming-related decisions, Taralis also observe the behavior of plants and animals and the direction of the sun and stars. For example, the flowering time of wild peaches has shifted to a week prior compared with a decade earlier on account of increasingly dry winters. The Tarali people in the Tichurong valley have their own local knowledge of meteorology and experience in weather forecasting. Chhiring Budha, 59 years old, noted:

Black clouds are a sign of rain. White clouds are signs of no rain. Red clouds are a sign of clear weather. If there is hot weather on a cloudy day, it may lead to rain. If it is normal, then it may not rain. Seeing rangja (gnats) is a sign of clouds and rain. A morning red cloud is a sign of rain (as this is a water sign) and evening red clouds are a sign of no rain (being associated with fire). But these days, even this kind of knowledge of forecasting weather does not match current weather patterns.

Chhiring Budha’s narrative describes how local knowledge of weather forecasting is increasingly incompatible with changing weather patterns and disruptions to local climes, representing “a breakdown of relations and norm-worlds, leading to social, ecological, and aesthetic ruin and despoliation” (Wouters 2023, p. 257). Similar sentiments were expressed by other elders in the village, all of whom mentioned that existing knowledge and reliance on previous forecasting signs and symbols are not working as well as they used to. Elders indicated that something was clearly changing. Along these lines, Wangkya Lama (a monk) noted that the summer migration of the demoiselle crane (Grus virgo) used to indicate a chance of rain:

Demoiselle cranes fly from the Tarai (southern plains of Nepal) to the northern mountains in the direction of Tibet. In the summer, when they fly as a flock, their movement results in clouds that bring rain. Taralis believe that god has gifted clouds and rain to the migrating demoiselle crane to protect them from attack by black eagles. So when Taralis hear the sound of migrating flocks of the demoiselle cranes between August 31 and September 30, they believe it will lead to rain. But now, even though flocks of demoiselle cranes fly high in the sky, there is no rain. Something has changed.

7. Re-Climing: Centering the Tarali Ecospiritual Imagination

We concur with Wouters when he writes, “for all its invaluable knowledge production, climate science does not inhabit actual glaciers, mountaintops, or water bodies, as indigenous climes do” (Wouters 2023, p. 263). This paper describes Tarali experiences and perceptions of changing climes, alongside transformations in wider climatic and weather conditions, and their impact on the lives and livelihoods of those in the Tichurong valley in Dolpa. Using nham “weather” and sameu “time” and understanding changes in planting and harvesting times as local, indigenous proxies for clime thinking, our research has demonstrated how the people of Gumbatara make sense of changing ecological and meteorological conditions in the context of faith-based environmental understandings. Among those that we interviewed, the majority of people perceive and experience nham and sameu as shifting, along with the ecological, cultural, and spiritual indicators that Taralis have long relied upon to guide their agricultural practices.

In this paper, we have repeatedly invoked the concept of “ecospirituality.” In our understanding, this vital term speaks to a deep philosophical and relational perspective on our relationship with the Earth and the environment, one that goes beyond viewing nature merely as a resource for exploitation, control, or human dominance. Ecospirituality has both ethical implications and the potential to reorient environmental thought toward more reciprocal and reverent modes of being with the Earth. In this, ecospirituality serves as a guiding undercurrent structuring our thinking and engagement, shaping our efforts to attend to the more-than-human world with care, humility, and attunement. We foreground ecospirituality not as a peripheral or poetic gesture, but as a substantive and radical reorientation of how we think, feel, and act in relation to the Earth.

Weather, clime, and climate affect multiple dimensions in people’s lives, from their cultural and religious systems to their agricultural practices. Considering Tarali lived experiences through the lens of their own knowledge systems sheds light on how these massive transformations impact people, their livelihoods, and their living landscapes in variable, complex, and situated ways. Local discourses of shifting weather and environmental patterns contribute to an understanding of climate change knowledge as plural, refuting a singular institutional and scientific climate change narrative (Chakraborty et al. 2021).

Clime, climate, and weather are understood among the Tarali Magar people of Dolpa, both conceptually and linguistically, using temporality and weather as ways to demarcate moments of change and inflection. Taralis perceive that changing weather patterns are affecting the physical environment and note that cultural and religious practices connected to weather-dependent livelihood systems are not as reliable as they used to be. Also changing are the sacred relationships with deities residing in culturally and ecologically significant abodes throughout the valley that once reliably influenced the climate, weather, and seasonalities. Local, indigenous knowledge of meteorology, especially in the form of climate and weather forecasting, has been impacted by climate change and shifts in weather patterns. The result is that Tarali people experience the traditional indicators of their forecasting systems to be less accurate and reliable than before.

Our research argues that local people’s experiential knowledge rooted in indigenous agroecological practices, weather-forecasting systems, and ecospiritual and faith-based understandings of sacred geography need to be recognized and incorporated into wider policy formations related to climate change. While the specific terms “clime” and “climate” are not widely used among Tarali Magars, their impacts and consequences are sensorially and experientially lived by the entire community in ways that are intellectually experienced and viscerally embodied. It is important to highlight local and indigenous temporal and climatic conceptualizations and how these exist in relationship to religious and spiritual practices. This kind of diversity of thought and lived experience is important for expanding society’s ideas of how to approach the challenges of climate change and for understanding site-specific climate change manifestations. The effects of the global climate crisis are everywhere, and helping build adaptive capacity using place-based knowledge about climate is part of supporting indigenous self-determination in pursuing climate justice (Whyte 2020). The over-exploitation of natural resources on a global scale, especially by highly industrialized countries, exacerbates the impacts on the livelihoods of people like the Tarali Magars of Gumbatara. At the same time, local, indigenous knowledge systems and experiences remain largely neglected in climate change mitigation efforts and scientific approaches. Responding to climate change globally must involve an acknowledgement of how climate change manifests and is understood and experienced locally and an engagement with indigenous theory and experience in a way that is non-extractive and genuinely respectful.

Tarali people live in a high-altitude environment, where they have, for centuries and generations, relied heavily on an intimate relationship with their environment, with the spiritual realm and the more-than-human world for their livelihoods, whether in agriculture or more recently, for yarsagumba harvesting. Changes to global weather patterns, climatic systems, and local climes are threatening the Tarali’s annual agricultural and yarsagumba harvesting seasons. While the effects of shifting climes and climate change on the physical environment have been studied in a generalized sense, the impact of changes in climes on people’s lives and livelihoods has been a lesser focus within the natural sciences and is calling out for attention (Chakraborty and Sherpa 2021; Moore et al. 2015). In highlighting the experiences, imagination, and insight of a specific community in one village in the Himalayan region of Nepal, this paper contributes to a greater understanding of how environmental transformations are being felt, lived, and understood, and showcases the resilience and adaptability of indigenous communities living on the front lines of the climate crisis.

We end as we began, by opening a “space for thinking and theorising not just about or for the natural world, but rather with it” (Chao and Enari 2021, p. 46). What we are really talking about is what others have referred to as “ecological animism” (van Dooren and Rose 2016, p. 82), a process through which recognition is respected as a mode of encounter and through which we rediscover our enchantment with a world in which all life—no matter the scale, size, or sentience—is “involved in diverse forms of adaptive, generative responsiveness” (van Dooren and Rose 2016, p. 82). Sunil Amrith and Dan Smyer Yü offer an inviting framework to conclude our contribution: “As we are ontologically entangled in the anthropocenic web of life, we join forces with those who are actively nurturing a new planetary ecological consciousness for re-embracing the maternal principle of the earth, restoring the health of the earth and building new environmental ethics for equitable, just, and sustainable living for human and nonhuman beings” (Amrith and Yü 2023, p. 48).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.B.B., M.D. and M.T.; methodology, J.B.B., M.D. and M.T.; writing—original draft preparation, J.B.B., M.D. and M.T.; writing—review and editing, J.B.B., M.D. and M.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Behavioral Research Ethics Board (BREB) of the University of British Columbia (certificate number H21-01715, approved on 28 June 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Co-author Budha is a member of the community in which this research was conducted. He received free, ongoing and informed oral consent from each of the research participants in the study and explained the implications of the research questions in the local language. In each case, Budha confirmed whether research participants wished to remain anonymous or have their names associated with their statements, and we have followed their wishes in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data used and analyzed in the study are available from the authors on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Adger, W. Neil, Jon Barnett, Katrina Brown, Nadine Marshall, and Karen O’brien. 2013. Cultural Dimensions of Climate Change Impacts and Adaptation. Nature Climate Change 3: 112–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amrith, Sunil, and Dan S. Yü. 2023. The Himalaya and Monsoon Asia: Anthropocenic Climes since the 1800s. In Storying Multipolar Climes of the Himalaya, Andes and Arctic. Edited by Dan Smyer Yü and Jelle J. P. Wouters. London: Routledge, pp. 29–51. [Google Scholar]

- Askland, Hedda H., and Matthew Bunn. 2018. Lived Experiences of Environmental Change: Solastalgia, Power and Place. Emotion, Space and Society 27: 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awasis, Sakihitowin. 2020. ‘Anishinaabe time’: Temporalities and impact assessment in pipeline reviews. Journal of Political Ecology 27: 830–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkes, Fikret. 2008. Sacred Ecology, 2nd ed. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Berroeta, Héctor, Laís Pinto de Carvalho, and Jorge Castillo-Sepúlveda. 2021. The Place–Subjectivity Continuum after a Disaster: Enquiring into the Production of Sense of Place as an Assemblage. In Changing Senses of Place: Navigating Global Challenges. Edited by Andrés Di Masso, Christopher M. Raymond, Daniel R. Williams, Lynne C. Manzo and Timo von Wirth. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 43–52. [Google Scholar]

- Bhutia, Kalzang Dorjee. 2023. Offerings from the Rivers to the Mountains: Mist and Fog as Connecting Life Force in the Sikkimese Himalayas 1. In Storying Multipolar Climes of the Himalaya, Andes and Arctic. Edited by Dan Smyer Yü and Jelle J. P. Wouters. London: Routledge, pp. 121–137. [Google Scholar]

- Bohlinger, Patrik, and Asgeir Sorteberg. 2018. A Comprehensive View on Trends in Extreme Precipitation in Nepal and Their Spatial Distribution. International Journal of Climatology 38: 1833–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brace, Catherine, and Hilary Geoghegan. 2010. Human Geographies of Climate Change: Landscape, Temporality, and Lay Knowledges. Progress in Human Geography 35: 284–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budha, Jag B. 2015. Yarsagumba and Emerging Consumption Culture Among Tarali Magar People in Dolpa District. Master’s thesis, Tri-Chandra Multiple Campus, Kathmandu, Nepal. [Google Scholar]

- Budha, Jag B. 2023. Kharche Ritual: A Soul Retrieval Ritual of Tarali Magar People of Dolpa. Magar Studies-A Journal from Magar Indigenous Peoples of Nepal 3: 41–51. [Google Scholar]

- Budha, Jag B., Maya Daurio, and Mark Turin. 2021. Tichurong (Nepal)—Language Snapshot. Language Documentation and Description 20: 189–97. [Google Scholar]

- Carey, Mark. 2010. In the Shadow of Melting Glaciers: Climate Change and Andean Society. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Carey, Mark. 2012. Climate and History: A Critical Review of Historical Climatology and Climate Change Historiography. WIREs Climate Change 3: 233–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, Dane, and Tshewang Tamang. 2022. A Landscape That Has Never Existed: Temporalities of Control and Disaster-Making in the Terai. Thresholds 50: 257–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, Ritodhi, and Pasang Y. Sherpa. 2021. From Climate Adaptation to Climate Justice: Critical Reflections on the IPCC and Himalayan Climate Knowledges. Climatic Change 167: 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakraborty, Ritodhi, Costanza Rampini, and Pasang Y. Sherpa. 2023. Mountains of Inequality: Encountering the Politics of Climate Adaptation across the Himalaya. Ecology and Society 28: 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, Ritodhi, Mabel D. Gergan, Pasang Y. Sherpa, and Costanza Rampini. 2021. A Plural Climate Studies Framework for the Himalayas. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 51: 42–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, Sophie, and Dion Enari. 2021. Decolonising climate change: A call for beyond-human imaginaries and knowledge generation. eTropic: Electronic Journal of Studies in the Tropics 20: 32–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Childs, Geoff, Sienna R. Craig, Christina Juenger, and Kristine Hildebrandt. 2021. This Is the End: Earthquake Narratives and Buddhist Prophesies of Decline. HIMALAYA 40: 32–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crate, Susan A. 2008. Gone the Bull of Winter?: Grappling with the Cultural Implications of and Anthropology’s Role(s) in Global Climate Change. Current Anthropology 49: 569–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crate, Susan A. 2021. Sakha and Alaas: Place Attachment and Cultural Identity in a Time of Climate Change. Anthropology and Humanism 47: 20–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crate, Susan A., and Mark Nuttall. 2009. Introduction: Anthropology and Climate Change. In Anthropology and Climate Change. Edited by Susan A. Crate and Mark Nuttall. London: Routledge, pp. 9–36. [Google Scholar]

- Cruikshank, Julie. 2001. Glaciers and Climate Change: Perspectives from Oral Tradition [of Athapaskan and Tlingit Elders]. Arctic 54: 377–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruikshank, Julie. 2005. Do Glaciers Listen?: Local Knowledge, Colonial Encounters, and Social Imagination. Vancouver: UBC Press. [Google Scholar]

- Daurio, Maya. 2009. Exploring Perspectives on Landscape and Language among Kaike Speakers in Dolpa, Nepal. Master’s thesis, University of Montana, Montana, MT, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Daurio, Maya. 2012. The Fairy Language: Language Maintenance and Social-Ecological Resilience Among the Tarali of Tichurong, Nepal. Himalaya 31: 7–21. [Google Scholar]

- Dawadi, Binod, Shankar Sharma, Emmanuel Reynard, and Kabindra Shahi. 2023. Climatology, Variability, and Trend of the Winter Precipitation over Nepal. Earth Systems and Environment 7: 381–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeSilvey, Caitlin. 2012. Making Sense of Transience: An Anticipatory History. Cultural Geographies 19: 31–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desjarlais, Robert R. 2003. Sensory Biographies: Lives and Deaths among Nepal’s Yolmo Buddhists. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Devkota, Fidel. 2013. Climate Change and Its Socio-Cultural Impact in the Himalayan Region of Nepal—A Visual Documentation. Anthrovision 1: 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhaubanjar, Sanita, Vishnu P. Pandey, and Luna Bharati. 2020. Climate Futures for Western Nepal Based on Regional Climate Models in the CORDEX-SA. International Journal of Climatology 40: 2201–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diemberger, Hildegard, Astrid Hovden, and Emily T. Yeh. 2015. The Honour of the Snow-Mountains Is the Snow: Tibetan Livelihoods in a Changing Climate. In The High-Mountain Cryosphere: Environmental Changes and Human Risks. Edited by Andreas Kääb, Christian Huggel, John J. Clague and Mark Carey. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 249–71. [Google Scholar]

- Dorji, Kinley. 2024. Storied Toponyms in Bhutan: Affective Landscapes, Spiritual Encounters, and Clime Change. In Himalayan Climes and Multispecies Encounters. Edited by Dan Smyer Yü and Jelle J. P. Wouters. London: Routledge, pp. 71–86. [Google Scholar]

- Dove, Michael R., ed. 2014. The Anthropology of Climate Change: An Historical Reader. Malden: Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, James F. 1986. Trans-Himalayan Traders. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, James F. 2017. Trans-Himalayan Traders Transformed: Return to Tarang. Bangkok: Orchid Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gagné, Karine. 2013. Gone with the Trees: Deciphering the Thar Desert’s Recurring Droughts. Current Anthropology 54: 497–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubbell, Andrew J., and John C. Ryan. 2022. Introduction to the Environmental Humanities. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Huber, Toni, and Poul Pedersen. 1997. Meteorological Knowledge and Environmental Ideas in Traditional and Modern Societies: The Case of Tibet. The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 3: 577–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulme, Mike. 2009. Why We Disagree About Climate Change: Understanding Controversy, Inaction and Opportunity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hulme, Mike. 2017. Weathered: Cultures of Climate. London: SAGE Publications Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Kansakar, Sunil R., David M. Hannah, John Gerrard, and Gwyn Rees. 2004. Spatial Pattern in the Precipitation Regime of Nepal. International Journal of Climatology 24: 1645–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kattel, Giri R. 2022. Climate Warming in the Himalayas Threatens Biodiversity, Ecosystem Functioning and Ecosystem Services in the 21st Century: Is There a Better Solution? Biodiversity and Conservation 31: 2017–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khadka, Nitesh, Xiaoqing Chen, Shankar Sharma, and Bhaskar Shrestha. 2023. Climate Change and Its Impacts on Glaciers and Glacial Lakes in Nepal Himalayas. Regional Environmental Change 23: 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khattri, Man Bahadur, and Rishikesh Pandey. 2021. Agricultural Adaptation to Climate Change in the Trans-Himalaya: A Study of Loba Community of Lo-Manthang, Upper Mustang, Nepal. International Journal of Anthropology and Ethnology 5: 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkness, Verna J., and Ray Barnhardt. 1991. First Nations and Higher Education: The Four R’s—Respect, Relevance, Reciprocity, Responsibility. The Journal of American Indian Education 30: 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, Naomi. 2015. This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. the Climate. London: Penguin Books. [Google Scholar]

- Kundzewicz, Z. W., L. J. Mata, N. W. Arnell, P. Döll, B. Jimenez, K. Miller, T. Oki, Z. Şen, and I. Shiklomanov. 2008. The Implications of Projected Climate Change for Freshwater Resources and Their Management. Hydrological Sciences Journal 53: 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milton, Kay. 2008. Anthropological Perspectives on Climate Change. The Australian Journal of Anthropology 19: 57–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, Frances C., Justin S. Mankin, and Austin Becker. 2015. Challenges in Integrating the Climate and Social Sciences for Studies of Climate Change Impacts and Adaptation. In Climate Cultures: Anthropological Perspectives on Climate Change. Edited by Jessica Barnes and Michael R. Dove. New Haven: Yale University Press, pp. 169–95. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison, Kathleen D. 2016. On Putting Time in Its Place: Archaeological Practice and the Politics of Time in Southern India. Cambridge Archaeological Journal 26: 619–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, John F. 2007. The Impact of Climate Change on Smallholder and Subsistence Agriculture. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 104: 19680–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munn, Nancy D. 1992. The Cultural Anthropology of Time: A Critical Essay. Annual Review of Anthropology 21: 93–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, Dan, and Daniel R. Williams. 2021. Navigating the Temporalities of Place in Climate Adaptation: Case Studies from the USA. In Changing Senses of Place: Navigating Global Challenges. Edited by Andrés Di Masso, Christopher M. Raymond, Daniel R. Williams, Lynne C. Manzo and Timo von Wirth. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 32–42. [Google Scholar]

- Natcher, David C., Orville Huntington, Henry Huntington, F. Stuart Chapin, Sarah Fleisher Trainor, and La’ona DeWilde. 2007. Notions of Time and Sentience: Methodological Considerations for Arctic Climate Change Research. Arctic Anthropology 44: 113–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlove, Benjamin S., Ellen Wiegandt, and Brian H. Luckman, eds. 2008. Darkening Peaks: Glacier Retreat, Science, and Society. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Orlove, Benjamin S., John C. H. Chiang, and Mark A. Cane. 2002. Ethnoclimatology in the Andes: A Cross-Disciplinary Study Uncovers a Scientific Basis for the Scheme Andean Potato Farmers Traditionally Use to Predict the Coming Rains. American Scientist 90: 428–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, Vishnu Prasad, Sanita Dhaubanjar, Luna Bharati, and Bhesh R. Thapa. 2020. Spatio-Temporal Distribution of Water Availability in Karnali-Mohana Basin, Western Nepal: Climate Change Impact Assessment (Part-B). Journal of Hydrology: Regional Studies 29: 100691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paudel, Basanta, Dinesh Panday, and Kundan Dhakal. 2021. Climate. In The Soils of Nepal. Edited by Roshan Babu Ojha and Dinesh Panday. World Soils Book Series; Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 15–27. [Google Scholar]

- Pokharel, Binod, S.-Y. Simon Wang, Jonathan Meyer, Suresh Marahatta, Bikash Nepal, Yoshimitsu Chikamoto, and Robert Gillies. 2020. The East–West Division of Changing Precipitation in Nepal. International Journal of Climatology 40: 3348–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poudel, Jiban Mani. 2018. Pond Becomes a Lake: Challenges Posed by Climate Change in the Trans-Himalayan Regions of Nepal. Journal of Forest and Livelihood 16: 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ramble, Charles. 1995. Gaining Ground: Representations of Territory in Bon and Tibetan Popular Tradition. The Tibet Journal 20: 83–124. [Google Scholar]

- Roncoli, Carla, Todd Crane, and Ben Orlove. 2009. Fielding Climate Change in Cultural Anthropology |5| Anthropology An. In Anthropology and Climate Change, 1st ed. Edited by Susan A. Crate and Mark Nuttall. New York: Routledge, pp. 87–115. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, Deborah Bird. 1996. Nourishing Terrains: Australian Aboriginal Views of Landscape and Wilderness. Canberra: Australian Heritage Commission. [Google Scholar]

- Schlosberg, David, Hannah Della Bosca, and Luke Craven. 2020. Disaster, Place, and Justice: Experiencing the Disruption of Shock Events. In Natural Hazards and Disaster Justice: Challenges for Australia and Its Neighbours. Edited by Anna Lukasiewicz and Claudia Baldwin. Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 239–59. Available online: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-981-15-0466-2_13 (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Sherpa, Pasang Yangjee. 2014. Climate Change Impacts among the Sherpas: An Anthropological Study in the Everest Region, Nepal. Habitat Himalaya XVIII: 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Shrestha, Arun B., and Raju Aryal. 2011. Climate Change in Nepal and Its Impact on Himalayan Glaciers. Regional Environmental Change 11: 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, Uttam Babu, Shiva Gautam, and Kamaljit S. Bawa. 2012. Widespread Climate Change in the Himalayas and Associated Changes in Local Ecosystems. PLoS ONE 7: e36741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sørensen, Birgitte Refslund, and Kristoffer Albris. 2015. The Social Life of Disasters: An Anthropological Approach. In Disaster Research: Multidisciplinary and International Perspectives. Edited by Rasmus Dahlberg, Olivier Rubin and Morten Thanning Vendelø. London: Routledge, pp. 80–95. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, Sarah, and Benjamin S. Orlove, eds. 2003. Weather, Climate, Culture, 1st ed. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Talchabhadel, Rocky. 2021. Observations and Climate Models Confirm Precipitation Pattern Is Changing over Nepal. Jalawaayu 1: 25–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Themelis, Chryssa, Julie-Ann Sime, and Robert Thornberg. 2023. Informed grounded theory: A symbiosis of philosophy, methodology, and art. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research 67: 1086–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trenberth, Kevin E. 2011. Changes in Precipitation with Climate Change. Climate Research 47: 123–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuan, Yi-Fu. 1977. Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience. Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Turin, Mark, and Benjamin Chung. 2020. Temporal Concepts and Formulations of Time in Tibeto-Burman Languages. Journal of Asian Linguistic Anthropology 1: 39–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, Prakash. 2020. Climate Change Adaptation in Mountain Community of Mustang District, Nepal. The NEHU Journal XVIII: 29–39. [Google Scholar]

- van Dooren, Thom, and Deborah Bird Rose. 2016. Lively Ethography: Storying Animist Worlds. Environmental Humanities 8: 77–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vedwan, Neeraj, and Robert E. Rhoades. 2001. Climate Change in the Western Himalayas of India: A Study of Local Perception and Response. Climate Research 19: 109–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whyte, Kyle. 2017. Indigenous Climate Change Studies: Indigenizing Futures, Decolonizing the Anthropocene. English Language Notes 55: 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whyte, Kyle. 2020. Too Late for Indigenous Climate Justice: Ecological and Relational Tipping Points. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change 11: e603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whyte, Kyle P. 2018. Indigenous Science (Fiction) for the Anthropocene: Ancestral Dystopias and Fantasies of Climate Change Crises. Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space 1: 224–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widger, Tom, and Upul Wickramasinghe. 2020. Monsoon Uncertainties, Hydro-Chemical Infrastructures, and Ecological Time in Sri Lanka. In The Time of Anthropology: Studies of Contemporary Chronopolitics, 1st ed. Edited by Elisabeth Kirtsoglou and Bob Simpson. Abingdon and New York: Routledge, pp. 123–41. [Google Scholar]

- Wijunamai, Roderick. 2024. Paddy Clime: Ecological Indigeneity in the Naga Uplands. In Himalayan Climes and Multispecies Encounters. Edited by Dan Smyer Yü and Jelle J. P. Wouters. London: Routledge, pp. 30–47. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, Shawn. 2008. Research is Ceremony: Indigenous Research Methods. Halifax: Fernwood Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Wouters, Jelle J. P. 2023. Conclusion: Multilateral Clime Studies. In Storying Multipolar Climes of the Himalaya, Andes and Arctic. Edited by Dan Smeyer Yü and Jelle J. P. Wouters. London: Routledge, pp. 253–72. [Google Scholar]

- Wouters, Jelle J. P., and Dan Smyer Yü, eds. 2024. Himalayan Climes and Multispecies Encounters, 1st ed. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Yadav, Ram R., Pyar S. Negi, and Jayendra Singh. 2021. Climate Change and Plant Biodiversity in Himalaya, India. Proceedings of the Indian National Science Academy 87: 234–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yangzom, Deki, and Jelle J. P. Wouters. 2024. Encountering Climate Change: Agential Mountains, Angry Deities, and Anthropocenic Clime in the Bhutan Highlands. In Himalayan Climes and Multispecies Encounters. Edited by Dan Smyer Yü and Jelle J. P. Wouters. London: Routledge, pp. 174–196. [Google Scholar]

- Yü, Dan Smyer, and Jelle J. P. Wouters, eds. 2023. Storying Multipolar Climes of the Himalaya, Andes and Arctic: Anthropocenic Climate and Shapeshifting Watery Lifeworlds, 1st ed. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Yü, Dan Smyer. 2023. Multipolar Clime Studies of the Anthropocenic Himalaya, Andes and Arctic: An Introduction. In Storying Multipolar Climes of the Himalaya, Andes and Arctic. Edited by Dan Smyer Yü and Jelle J. P. Wouters. London: Routledge, pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).