Decorating Tibetan Buddhist Manuscripts: A Preliminary Analysis of Ornamental Writing Frames

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Decorated Writing Frames in Tibetan Buddhist Manuscripts: A Tentative Chronological Overview

3. Types of Decoration for Writing Frames

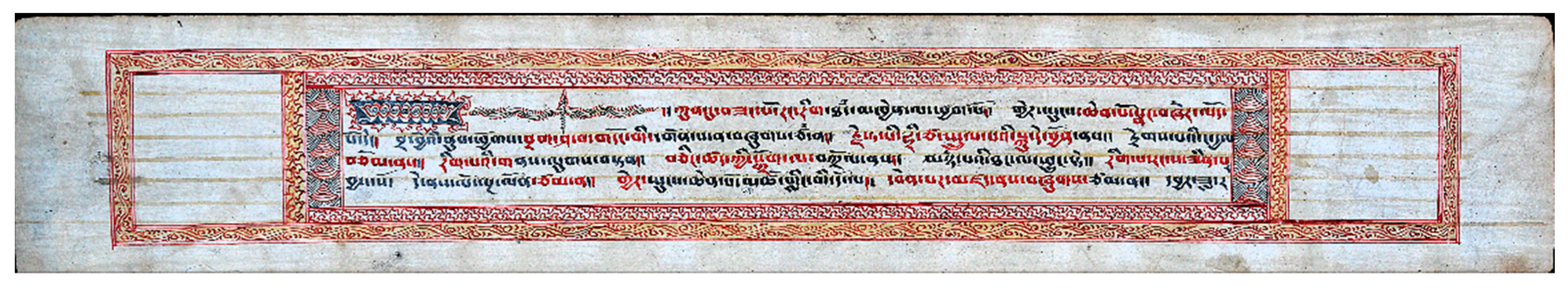

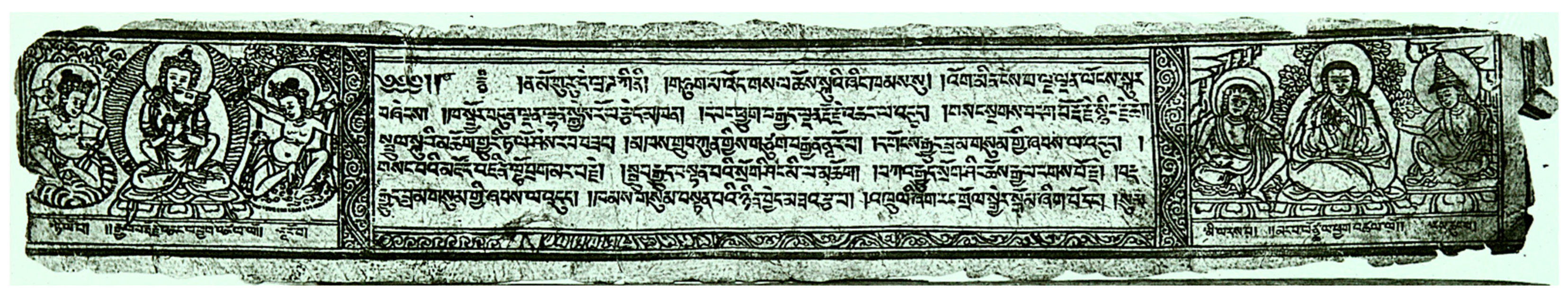

Some Examples of Entirely Decorated Writing Frames in Manuscripts from the 12th to the 18th Century

4. Concluding Remarks

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | The Tucci Tibetan Collection of the “IsIAO Library” (National Central Library of Rome) includes 22 volumes of the Tholing bKa’ ‘gyur, where it is possible to find such vertical lines. For the cataloguing entries of these volumes, see (De Rossi Filibeck 2003, pp. 437–46). |

| 2 | See, for example, the picture of the Glang dkar chag in (Heller 2009, p. 235). |

| 3 | For an example of rice-grain decorations in a writing frame, cf. Prajñāpāramitā vol. pha (N1999) in (Heller 2009, pp. 140–41). |

| 4 | On this subject, see (Clemente 2024, forthcoming). On this symbol in Tibetan culture, see (Beer 1999, pp. 38–39). |

| 5 | On this symbol, see (Beer 1999, p. 205). |

| 6 | |

| 7 | Amy Heller, who studied these manuscripts from an art-historical viewpoint and arranged the C14 analysis, was able to date them around 1100–1150. For a description of the illuminations, see (Heller 2009, pp. 94–97). |

| 8 | On these manuscripts, cf. (Heller 2009, pp. 100–1). |

| 9 | For its cataloguing entry, see (De Rossi Filibeck 2003, p. 429). |

| 10 | On this text, see The Detailed Account of the Previous Aspirations of the Seven Thus-Gone Ones/84000 Reading Room. |

| 11 | Cf. vol. 759. For its cataloguing, see (De Rossi Filibeck 2003, p. 350). On this text, see also (Sernesi 2021, pp. 157, 374–77). |

| 12 | The images of this manuscript are available in (Kapstein 2024), vol. I, pp. 42–44 (figures 1.24 and 1.25), 176–177 (figure 5.11). See also (Reynolds 1999, p. 146). |

| 13 | See, for example, a beautifully decorated writing frame found in a public ordinance issued by the regent of Tibet in 1814 preserved at the Library of Tibetan Works and Archives in Dharamsala (LTWA 158), an image of which can be found in (Schwieger 2024, p. 68). |

| 14 | See, for example, Or. 6726 and Or. 6727 preserved at the British Library. |

| 15 | See, for example, two hagiographies preserved in the Tucci Tibetan Collection: vol. 759 (described above) and vol. 770/3 (cf. (De Rossi Filibeck 2003, p. 352)). |

| 16 | See, for example, two manuscripts kept in the Tucci Tibetan Collection: vol. 1279 (described above) and vol. 1523 (cf. (De Rossi Filibeck 2021, pp. 164–65)). |

| 17 | This manuscript is preserved in the Tucci Tibetan Collection (vol. 374, cf. (De Rossi Filibeck 2003, p. 142)). |

| 18 | This manuscript is preserved in the Tucci Tibetan Collection (vol. 1457, cf. (De Rossi Filibeck 2003, p. 458); See also (Torricelli 1999)). |

| 19 | |

| 20 | For its cataloguing entry, see (De Rossi Filibeck 2003, p. 384). |

References

Primary Sources

20.495AB = ‘Phags pa shes rab kyi pha rol tu phyin pa brgyad stong pa. Manuscript. Newark Museum of Art.LTWA 158 = Public ordinance issued by the regent of Tibet in 1814, Library of Tibetan Works and Archives, Dharamsala.N192 vol. ca = ‘Phags pa shes rab kyi pha rold tu phyind pa stong phrag nyi shu lnga pa. Manuscript. Nesar Temple, Dolpo, Nepal.N331 vol. cha = ‘Phags pa shes rab kyi pha rold tu phyind pa stong phrag nyi shu lnga pa. Manuscript. Nesar Temple, Dolpo, Nepal.N405 vol. ga = ‘Phags pa shes rab kyi pha rold tu phyind pa stong phrag nyi shu lnga pa. Manuscript. Nesar Temple, Dolpo, Nepal.NGMPP L512/8 = lHa btsun Rin chen rnam rgyal, rGyud kyi dgongs pa gtsor ston pa/phyag rgya chen po yi ge bzhi pa’i ‘grel bshad gnyug ma’i gter mdzod. Microfilm of a xylograph. National Archives, Kathmandu.Or. 6726 = Shes rab kyi pha rold tu phyind pa stong phrag nyi shu lnga pa. Manuscript. The British Library, London.Or. 6727 = Shes rab kyi pha rold tu phyind pa stong phrag nyi shu lnga pa. Manuscript. The British Library, London.‘Phags pa shes rab kyi pha rold tu phyind pa stong phrag nyi shu lnga pa. Manuscript. Private collection, Nepal.Shes rab kyi pha rold tu phyind pa stong phrag brgya pa. Manuscript. Private collection. Nepal.Vol. 306 = Collected Works of Kun spangs Chos kyi rin chen. Manuscript. Tucci Tibetan Collection, “IsIAO Library”, National Central Library of Rome.Vol. 504/12 = Shes rab rgyal mtshan, sGron ma drug. Manuscript. Tucci Tibetan Collection, “IsIAO Library”, National Central Library of Rome.Vol. 759 = Sangs rgyas dar po, rGyal ba rgod tshangs pa mgon po rdo rje’i rnam thar mthong ba don ldan nor bu’i phreng ba. Manuscript. Tucci Tibetan Collection, “IsIAO Library”, National Central Library of Rome.Vol. 770/3 = Grub bzang rgyal mtshan, rJe rtse brgya ba’i rnam thar. Manuscript. Tucci Tibetan Collection, “IsIAO Library”, National Central Library of Rome.Vol. 1006 = Thugs rje chen po’i dbang chog go. Manuscript. Tucci Tibetan Collection, “IsIAO Library”, National Central Library of Rome.Vol. 1279 = De bzhin gshegs pa bdun gi smon lam gyi khyad par rgyas pa’i gzungs klags pa’i chog ga mdo sde. Manuscript. Tucci Tibetan Collection, “IsIAO Library”, National Central Library of Rome.Vol. 1315 = mTshan ldan bla ma rin chen rjes su dran pa’i mdo. Manuscript. Tucci Tibetan Collection, “IsIAO Library”, National Central Library of Rome.Vol. 1329O = Shes rab kyi pha rold tu phyind pa stong phrag brgya pa. Manuscript. Tucci Tibetan Collection, “IsIAO Library”, National Central Library of Rome.Vol. 1457 = gTsang smyon Heruka Sangs rgyas rgyal mtshan, bDe mchog mkha’ ‘gro snyan brgyud kyi man ngag gi bzhung ‘grel nor bu skor gsum. Manuscript. Tucci Tibetan Collection, “IsIAO Library”, National Central Library of Rome.Vol. 1523 = bCom ldan ′das zhi khro rab ′byams gyi tshogs la/rnal ′byor pa rnams la phyag tshal ba dang nyams chag bskang ba′i cho ga. Manuscript. Tucci Tibetan Collection, “IsIAO Library”, National Central Library of Rome.Secondary Sources

- Almogi, Orna, ed. 2016. Tibetan Manuscript and Xylograph Traditions: The Written Work and Its Media Within the Tibetan Cultural Sphere. Hamburg: Department of Indian and Tibetan Studies, University of Hamburg. [Google Scholar]

- Beer, Robert. 1999. The Encyclopedia of Tibetan Symbols and Motifs. London: Serindia Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Childs, Geoffrey. 2005. How to fund a Ritual: Notes on the Social Usage of the Kanjur (bKa’ ‘gyur) in a Tibetan Village. The Tibet Journal 30: 41–48. [Google Scholar]

- Clemente, Michela. 2016a. Different Facets of Mang yul Gung thang Xylographs. In Tibetan Manuscript and Xylograph Traditions: The Written Work and Its Media Within the Tibetan Cultural Sphere. Edited by Orna Almogi. Hamburg: Department of Indian and Tibetan Studies, University of Hamburg, pp. 67–103. [Google Scholar]

- Clemente, Michela. 2016b. The Unacknowledged Revolution? A Reading of Tibetan Printing History on the Basis of Gung thang Colophons Studied in Two Dedicated Projects. In Tibetan Printing: Comparison, Continuities, and Change. Edited by Hildegard Diemberger, Franz-Karl Ehrhard and Peter F. Kornicki. Leiden and Boston: Brill, pp. 394–423. [Google Scholar]

- Clemente, Michela. 2018. Mapping Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries Buddhist Printed Works in South-Western Tibet. A Historical and Literary Reading. In Dialectics of Buddhist Methaphysics in East Asia. Tibet and Japan: An Inedited Comparison. Edited by Donatella Rossi. Special issue. Rivista degli Studi Orientali 91: 19–41. [Google Scholar]

- Clemente, Michela, ed. 2021. Traditional Paths, Innovative Approaches and Digital Challenges in the Study of Tibetan Manuscripts and Xylographs. Rome: Scienze e Lettere-ISMEO. [Google Scholar]

- Clemente, Michela. 2024. A preliminary analysis of title frames in Bon po manuscripts and xylographs: Examples from the Tucci Tibetan collection. In Traditions, Translations and Transitions in the Cultural History of Tibet, the Himalayas and Mongolia. Edited by Donatella Rossi, Davor Antonucci, Michela Clemente and Davide Torri. Rome: Scienze e Lettere-ISMEO, pp. 87–107. [Google Scholar]

- Clemente, Michela, and Filippo Lunardo. 2017. Typology of drawn frames in sixteenth century Mang yul Gung thang xylographs. In Indic Manuscript Culture Through the Ages: Material, Textual and Historical Investigations. Edited by Vincenzo Vergiani, Daniele Cuneo and Camillo A. Formigatti. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 287–318. [Google Scholar]

- Clemente, Michela. Forthcoming. Flowering Titles: A Preliminary Analysis. Case studies from the Tucci Tibetan Collection. In Beyond Words: Object-Based Approaches to Tibetan Book Culture. Edited by Agnieszka Helman-Wazny and Markus Viehbeck. Heidelberg: Heidelberg Asian Studies Publishing. (In process)

- De Rossi Filibeck, Elena. 1994. A study of a fragmentary manuscript of the Pañcaviṃśatikā in the Ta pho library. East and West 44: 137–59. [Google Scholar]

- De Rossi Filibeck, Elena. 1996. Note on a manuscript from the tucci collection in the IsIAO library. East and West 46: 485–87. [Google Scholar]

- De Rossi Filibeck, Elena. 2002. Una nota sulle immagini decorative delle xilografie tibetane. In Oriente e Occidente. Convegno in ricordo di Mario Bussagli: Roma 31 maggio-1 giugno 1999. Edited by Chiara Silvi Antonini, Bianca Maria Alfieri and Arcangela Santoro. Pisa and Roma: Istituti Editoriali e Poligrafici Internazionali, pp. 92–103. [Google Scholar]

- De Rossi Filibeck, Elena. 2003. Catalogue of the Tucci Tibetan Fund in the Library of IsIAO. Rome: Istituto Italiano per l’Africa e l’Oriente, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- De Rossi Filibeck, Elena. 2006. Aspetti formali e contenuti del manoscritto tibetano: Esempi dal Tibet occidentale. In Scritture e Codici nelle Culture dell’Asia: Giappone, Cina, Tibet, India. Prospettive di Studio. Edited by Giuliano Boccali and Maurizio Scarpari. Venezia: Ca’ Foscarina, pp. 287–305. [Google Scholar]

- De Rossi Filibeck, Elena. 2021. Tucci tibetan collection: Addenda. In Traditional Paths, Innovative Approaches and Digital Challenges in the Study of Tibetan Manuscripts and Xylographs. Edited by Michela Clemente. Rome: Scienze e Lettere-ISMEO, pp. 137–65. [Google Scholar]

- Diemberger, Hildegard. 2012a. Holy books as ritual objects and vessels of teaching in the era of the ‘Further Spread of the Doctrine’ (bstan pa yang dar). In Revisiting Rituals in a Changing Tibetan World. Edited by Katia Buffetrille. Leiden: Brill, pp. 9–41. [Google Scholar]

- Diemberger, Hildegard. 2012b. Quand le livre devient relique. Les textes tibétains entre culture bouddhique et transformations technologiques. Terrain, Revue D’ethnologie Europeénne 59: 18–39. [Google Scholar]

- Diemberger, Hildegard, Franz-Karl Ehrhard, and Peter F. Kornicki, eds. 2016. Tibetan Printing: Comparison, Continuities, and Change. Leiden and Boston: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Diemberger, Hildegard, Mark Elliott, and Michela Clemente. 2014. Buddha’s Words. The Life of Books in Tibet and Beyond. Cambridge: Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of Cambridge. [Google Scholar]

- Dotson, Brandon, and Agnieszka Helman-Ważny. 2016. Codicology, Paleography, and Orthography of Early Tibetan Documents. Methods and a Case Study. Wien: Arbeitskreis für Tibetische und Buddhistische Studien Universität Wien. [Google Scholar]

- Heller, Amy. 2009. Hidden Treasures of the Himalayas. Tibetan Manuscripts, Paintings and Sculptures of Dolpo. Chicago: Serindia Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Helman-Ważny, Agnieszka. 2014. The Archaeology of Tibetan Books. Leiden and Boston: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Helman-Ważny, Agnieszka, and Charles Ramble. 2021. The Mardzong Manuscripts. Codicological and Historical Studies of an Archaeological Find in Mustang, Nepal. Leiden and Boston: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Helman-Ważny, Agnieszka, and Charles Ramble. 2023. Bon and Naxi Manuscripts. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Kapstein, Matthew T., ed. 2024. Tibetan Manuscripts and Early Printed Books. Volume I. Elements. Volume II. Elaborations. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Luczanits, Christian, and Markus Viehbeck. 2021. Two Illuminated Text Collections of Namgyal Monastery. A Study of Early Buddhist Art and Literature in Mustang. Kathmandu: Vajra Books. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, Dan. 2023. Earth and wind, water and fire: Book binding and preservation in pre-mongol bon ritual manuals for consecrations. In Bon and Naxi Manuscripts. Edited by Agnieszka Helman-Ważny and Charles Ramble. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 87–106. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, Valrae. 1999. From the Sacred Realm: Treasures of Tibetan Art from the Newark Museum. With contributions by Janet Gyatso, Amy Heller and Dan Martin. Munich: Prestel. [Google Scholar]

- Schaeffer, Kurtis R. 2009. The Culture of the Book in Tibet. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Scherrer-Schaub, Cristina Anna. 1999. Towards a Methodology for the study of old tibetan manuscripts: Dunhuang and Tabo. In Tabo Studies II. Manuscripts, Texts, Inscriptions, and the Arts. Edited by Cristina Anna Scherrer-Schaub and Ernst Steinkellner. Roma: Istituto Italiano per l’Africa e l’Oriente, pp. 3–36. [Google Scholar]

- Scherrer-Schaub, Cristina Anna, and Ernst Steinkellner. 1999. Tabo Studies II. Manuscripts, Texts, Inscriptions, and the Arts. Roma: Istituto Italiano per l’Africa e l’Oriente. [Google Scholar]

- Scherrer-Schaub, Cristina Anna, and Giorgio Bonani. 2002. Establishing a typology of the old Tibetan manuscripts: A multidisciplinary approach. In Dunhuang Manuscript Forgeries. Edited by Susan Whitfield. London: The British Library, pp. 184–215. [Google Scholar]

- Schwieger, Peter. 2024. A public ordinance illustrating the application of Tibet’s criminal law (Chapter 13). In Tibetan Manuscripts and Early Printed Books. Volume II. Elaborations. Edited by Matthew T. Kapstein. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, pp. 68–79. [Google Scholar]

- Sernesi, Marta. 2021. Re-Enacting the Past. A Cultural History of the School of gTsang smyon Heruka. Wiesbaden: Reichert Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Steinkellner, Ernst. 1994. A Report on the ‘Kanjur’ of Ta Pho. East and West 44: 115–36. [Google Scholar]

- Torricelli, Fabrizio. 1999. Nota su un manoscritto Tibetano nel Fondo Tucci dell’IsIAO. Rivista Degli Studi Orientali 73: 149–63. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Clemente, M. Decorating Tibetan Buddhist Manuscripts: A Preliminary Analysis of Ornamental Writing Frames. Religions 2025, 16, 582. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16050582

Clemente M. Decorating Tibetan Buddhist Manuscripts: A Preliminary Analysis of Ornamental Writing Frames. Religions. 2025; 16(5):582. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16050582

Chicago/Turabian StyleClemente, Michela. 2025. "Decorating Tibetan Buddhist Manuscripts: A Preliminary Analysis of Ornamental Writing Frames" Religions 16, no. 5: 582. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16050582

APA StyleClemente, M. (2025). Decorating Tibetan Buddhist Manuscripts: A Preliminary Analysis of Ornamental Writing Frames. Religions, 16(5), 582. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16050582