Exploring Early Buddhist–Christian (Jingjiao 景教) Dialogues in Text and Image: A Cultural Hermeneutic Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Phenomenon of Geyi in Jingjiao Translations

At the end of the Han [dynasty] and the beginning of the Wei [dynasty], the chancellor of Guangling and the chancellor of Pengcheng ‘joined the Order’ and were both able to maintain the great light (of the Doctrine). Inspired by their actions, worthy [intellectuals of the time] began to take an interest in [discussing and] lecturing on Buddhism. Thus, using ‘matching meanings’ (格義), they ‘broadened the scope’ [of the teachings], and, by ‘pairing explanations’ (配説), made them indirect and circuitous.漢末魏初, 廣陵, 彭城二相出家, 並能任持大照, 尋味之賢, 始有講次. 而恢之以格義, 迂之以配説.22

[Zhu Faya] took the ‘numerical categories’ (shishu 事數) of the sūtras and matched these with (terms from) non-Buddhist works (secular literature), as a method to make [his disciples] understand. This was called “matching meanings” (geyi).以經中事數, 擬配外書, 爲生解之例, 謂之格義.23

Prajña was not proficient in the Syriac language and did not understand the Tang (i.e., Chinese, 唐言) language; Jingjing did not understand Sanskrit (fanwen 梵文) and was unfamiliar with Buddhist doctrine (shijiao 釋教). Although he assisted Prajña in translating the scripture, he failed to grasp lit. half of the jewels (of the Buddhist teaching) (i.e., its essence) … Furthermore, the monks of the Da Qin Monastery live differently from Buddhist monks (in a jialan). Jingjing should spread the teachings of the Messiah (mishihe jiao), while the śramaṇa and Sakya-son (i.e., Buddhist monks) should propagate the Buddhist sūtras. Thus, (His Majesty wished) a clear distinction between the two traditions should be maintained so that people do not conflate the different paths. True and false teachings (should) remain different as the Jing and the Wei Rivers flow separately.時爲般若, 不嫻胡語, 復未解唐言; 景淨不識梵文, 復未明釋教. 雖稱傳譯, 未獲半珠; 圖竊虛名, 匪位副理…. 且夫釋氏伽藍, 大秦寺, 居止既別, 行法全乖. 景淨應傳彌師訶教; 沙門釋子, 弘闡佛經. 欲使教法區分, 人無濫涉; 正鄧異類, 徑渭殊流.46

- (1)

- First, in contrast to early Buddhist texts that were translated from known Sanskrit or Central Asian origins, the existing Jingjiao texts were not derived from any identifiable “Syriac” original or other Christian texts in alternative languages, such as Iranian.50 Instead, these texts were crafted to introduce the basics of Christianity to a Chinese-speaking audience, the specifics of which—such as size; composition; and social, ethnic, or religious background—are still unknown. It remains uncertain how many readers engaged with these texts and whether the audience was exclusively Chinese believers or included Iranian Christians, possibly even second or third-generation Chinese Iranians after the fall of the Persian dynasty. Nevertheless, given that Chinese served as a lingua franca, it is plausible that the texts were intended for a broader audience.

- (2)

- Second, the absence of a Syriac, Iranian, or other Christian source text has significant implications for interpretation. While Buddhist scriptures can often be elucidated by referencing the extensive corpus of Sino-Buddhist terminology and its Indian or Tibetan counterparts, Tang-period Jingjiao texts frequently leave us without clear indications of their underlying content, terminology, or doctrinal references as they existed in known Syriac-Christian languages from the Near East or Central Asia.

- (3)

- Finally, rather than directly incorporating Syriac or Iranian Christian theological vocabulary, Jingjiao texts rely heavily on the established terminological frameworks of Buddhism, Daoism, and Ruism (commonly called Confucianism). Consequently, the meaning of individual words and phrases—their syntactical structures and compound formations—is often difficult to ascertain. At that time, Abrahamic and Greek concepts were not present in Chinese. Therefore, in many instances, only by situating these terms within the broader religious lexicon of Tang China, from which they were derived, can their intended meanings be fully understood.51

3. The Borrowing of Concepts from Iconic Buddhist Images After the Spread of the Jingjiao Church to China

[The] Bodhisattva, approaching life-size, is standing slightly to [the] L[eft] with [its] head turned still further towards [the] same side; [The figure’s] R[ight] arm [is] raised from [the] elbow, and [its] hand held out palm uppermost, thumb and second finger joined; [the] L[eft] hand at [its] breast, [is] mostly broken away, but holding [a] long brown staff which [is] rested on [its] shoulder. This may have been [a] begging-staff, and [the] deity in that case might be Kṣitigarbha. [the] Dress and treatment of [the] fig[ure] are in some points unique, though [the] general style is ‘Chinese Buddhist’ […] [the] Face [is] long and comparatively thin, finely drawn, with [a] high forehead, straight eye[s], [a] slightly aquiline nose, and [a] firm well-made mouth and chin.[the] Eye[s] blue ([the] only instance of this in the Collection); [the] flesh yellowish pink outlined with dark red except [the] line of [the] eyelash[es], [the] corner of [the] nostril, and [the] dividing line of [the] lips, which are black. On [the] lip[s] and chin [the] moustache and beard seem to be painted in dark red (?), but this part is much discoloured. Details of [the] tiara and [the] top of [the] head are also much obscured, but [the] hair seems to be done in two low blue-black masses dividing to [the] R[ight] and L[eft] behind [the] two wing-shaped ornaments on [the] tiara. [The] Latter has none of [the] usual jewels or streamers, but consists chiefly of these wing orn[ament]s with lotus orn[aments] (?) at their base, and a ‘Maltese cross’ standing up in [the] middle. Behind [the] latter is seen [the] dark brown centre of [a] halo; it is oval, and consists of this brown field surrounded by rings of white, crimson, green, and an outer border of [a] creeping flame. No hair is visible below, but a line of red and yellow scrolled circles appears over [the] R[ight] shoulder (perhaps [the] hair [is] miscoloured) […]

[The] Jewellery comprises only [a] heavy necklace and bracelet, both [of which are] yellow [and] outlined with red. Small red flowers [are] scattered in [the] background. [The] Painting [is] much dimmed and discoloured, especially down [the] broken side.65

4. Dialogues with Buddhism Accelerated the Localization of the Jingjiao Church

When Emperor Taizong’s reign (627–649 CE) began, he was wise in his relations with the people. In Da Qin, there was a ‘man of great virtue’ (a bishop), known as Aluoben [A-lo-pen] [XI]76, who detected the intent of heaven and conveyed the true scripture here. He observed how the winds blew to travel through difficulties and perils, and in the ninth year of the Zhenguan era (635 CE), he reached Chang’an. The emperor dispatched an official, Fang Xuanling, as an envoy to the western outskirts to welcome the visitor, who translated the scriptures in the ‘Academy of Scholars’ (imperial library)77. (The emperor) examined the doctrines [inside] the forbidden gates (i.e., the palace/his apartments) and reached a profound understanding of their truth. He specially ordered that they be promulgated 太宗文皇帝. 光華啓運, 明聖臨人, 大秦國有上德, 曰阿[XI]羅本. 佔青雲而載真經, 望風律以馳艱險. 貞觀九祀, 至於長安. [缺/璹]帝使宰臣房公玄齡, 㧾/惣[總]78仗西郊, 賓迎入內. 翻經書殿, 問道禁闈; 深知正真, 特令傳授.79

Life is the great virtue of Heaven and Earth, and the lifespan is [but] a fleeting moment. Life, embodied in seven chi (one’s body), is limited to a hundred years. It encompasses a unique spirit and energy inherent in [a] self-existing nature beyond external control. As the Liji (Book of Rites) declares, ‘When a Ruler succeeds to his state, he makes his coffin (bì 椑),’ Zhuang Zhou observes, ‘[Heaven and Earth], my life is spent in toil on it; at death I find rest in it.’ Is this not the far-sighted wisdom of the Sages and the profound knowledge of the wise?” 夫生者, 天地之大德, 壽者, 修短之一期. 生有七尺之形, 壽以百齡爲限, 含靈稟氣, 莫不同焉, 皆得之於自然, 不可以分外企也. 是以禮記雲: ‘君即位而爲椑’. 莊周雲: ‘勞我以形, 息我以死.’ 豈非聖人遠鑒, 通賢深識?80

The previous life of the August Ruler (Your Majesty) was blessed by God, and the ‘Heaven-Honored One’ (God)81 took over the position. Is it not possible that Your Majesty is the ‘Heaven-Honored One’ himself?聖上前身福弘, 天尊補任, 亦無自乃天尊耶?82

Your Majesty is the emperor, and all living beings follow your progress and behavior. If anyone fails to respect the August Ruler’s will or disobeys your orders, that person is a rebel among all living beings.

Your Majesty is a god born into this world. Although your parents are still alive, all beings possess wisdom and plans. You should revere both the Heaven-Honored One (God) and the August Ruler, as well as honor your parents. To accept the doctrine of the Heaven-Honored One means to uphold the precepts. [According to] what the Heaven-Honored One accepts, and if one embraces the Honored teaching, one must first renounce reverence to the gods and the buddhas worshipped by other living beings, for the buddhas endure suffering. Heaven and earth were established solely through the pure power of the Heaven-Honored One. Therefore, Your Majesty should strive to eliminate outdated customs and seek the divine palace through the wisdom of the buddhas. In doing so, Your Majesty will remain forever free.85聖上皆是神生, 今世雖有父母見存, 眾生有智計; 合怕天尊及聖上, 並怕父母. 好受天尊法教, 不合破戒. 天尊所受, 及受尊教, 先遣眾生禮諸天, 佛, 爲佛受苦. 置立天地, 只爲清淨威力, 因緣. 聖上唯須勤伽習俊, 聖上宮殿, 於諸佛求得. 聖上身, 總是自由.86

…mysterious and transcendent non-action, that establish the essentials of production and completion, and are of help to the beings and of profit to mankind.玄妙無爲; 生成立要, 濟物利人.87

5. The Historical Motivation for Christian–Buddhist Dialogue in China

5.1. The Silk Roads and the Deepening of Ancient Globalization

5.2. The Cultural Gene of “Neutrality” in Chinese Civilization

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| T | Taishō shinshū daizōkyō 大正新脩大藏經 [Buddhist Canon Compiled during the Taishō Era (1912–1926)]. 100 vols. Takakusu Junjirō 高楠順次郎 and Watanabe Kaigyoku 渡邊海旭 et al., eds. Tōkyō: Taishō Issaikyō Kankōkai 大正一切經刊行會, 1924–1934. Digitized in CBETA (https://cbetaonline.dila.edu.tw/zh/, accessed on 16 February 2025) and SAT Daizōkyō Text Database (http://21dzk.l.u-Tōkyō.ac.jp/SAT/satdb2015.php, accessed on 16 February 2025). |

| X | Xinbian xu zangjing 新編卍字續藏經 [Man Extended Buddhist Canon]. 150 vols. Xin wenfeng chuban gongsi 新文豐出版公司, Taibei 臺北, 1968–1970. Reprint of Nakano Tatsue 中野達慧, et al., comps. Dai Nihon zoku zōkyō 大日本續藏經 [Extended Buddhist Canon of Great Japan], 120 cases. Kyoto: Zōkyō shoin 藏經書院, 1905–1912. Digitized in CBETA (https://cbetaonline.dila.edu.tw/zh/, accessed on 16 February 2025). |

| B | Da zangjing bubian 大藏經補編 [Supplement to the Dazangjing]. Huayu chuban she 華宇出版社, Taibei 臺北, 1985. Ed. Lan Jifu 藍吉富. |

| Eccles and Lieu Trans. Project | Eccles, L. and S. Lieu. 2023. Da Qin jingjiao liuxing Zhongguo bei 大秦景教流行中國碑 “Stele on the Diffusion of Christianity (the Luminous Religion) from Da Qin (Rome) into China (the Middle Kingdom)”, “The Nestorian Monument”. Ongoing Project (last updated: 5 November 2023). |

| Tonkō hikyū | Tonkō hikyū: keikyō kyōten yonshu 敦煌秘笈: 景教経典四種 [Dunhuang Secret Scrolls: Four Jingjiao Scriptures]. Takeda kagaku shinkō zaidan kyōu shooku hen 武田科学振興財団杏雨書屋編. Osaka 大阪: Takeda kagaku shinkō zaidan 武田科学振興財団, 2020. |

| Pelliot INS 1996 | Paul Pelliot, L’inscription nestorienne de Si-Ngan-Fou, edited with supplements by Antonino Forte. Epigraphical Series 2 (Kyoto: Scuola di Studi sull’Asia Orientale; Paris: Collège de France, Institut des Hautes Études Chinoises, 1996). (Pelliot 1996) |

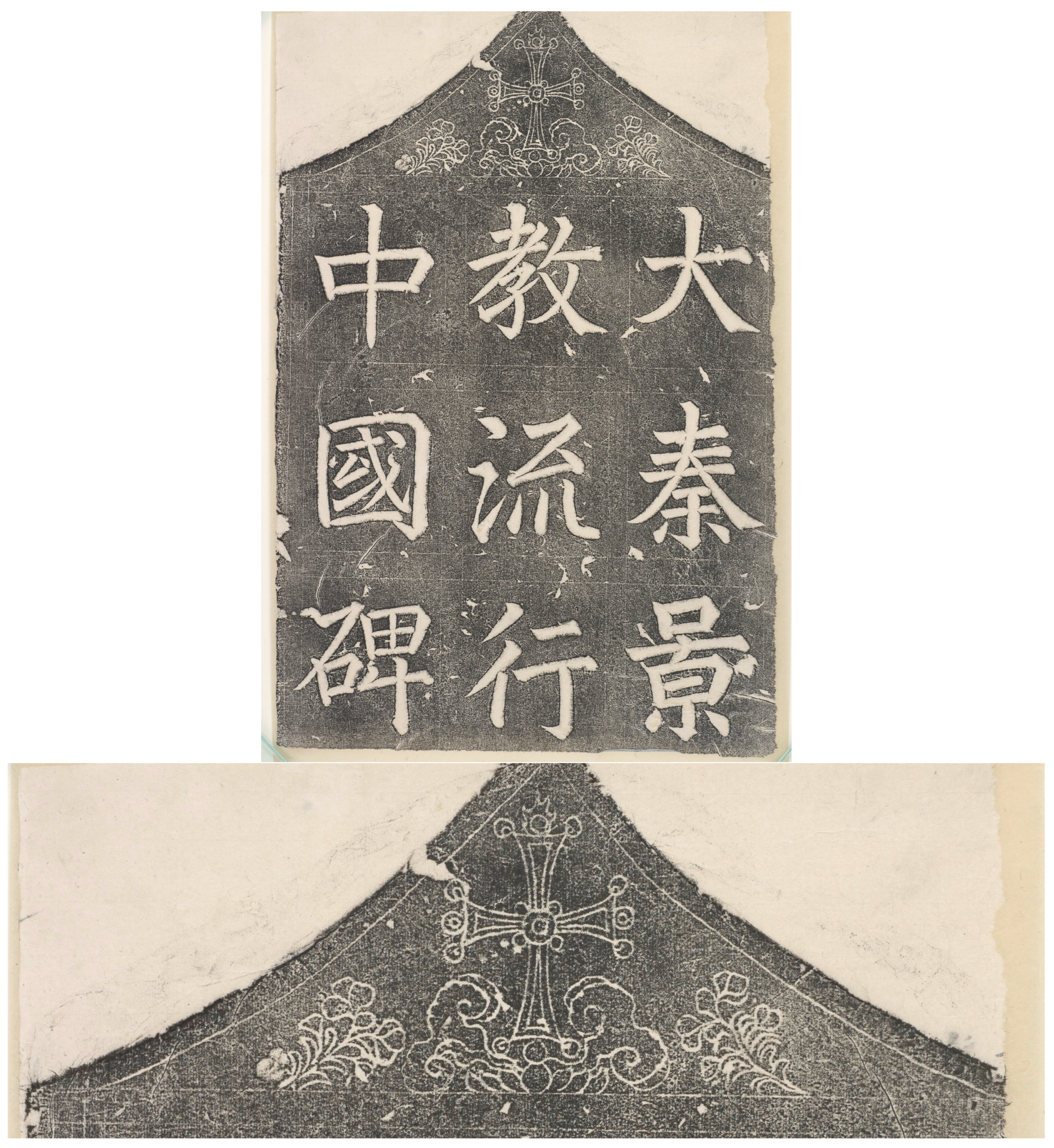

| JJB | Jingjiaobei 景教碑 = Da Qin jingjiao liuxing Zhongguo bei 大秦景教流行中國碑 [Stele of the Promulgation of the ‘Radiant Teaching’ of Da Qin in China, 781], in Pelliot INS (1996, pp. 497–503). |

| [I–XXXII] | Indicates lines of JJB, following Pelliot INS (1996, pp. 497–503) |

| HCC | Handbook of Christianity in China, Volume One: 635–1800. Edited by Standaert, Nicolas (Leiden: Brill, 2001). |

| P. 3847 | Pelliot chinois No. 3847, conserved at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France in Paris |

| Kyo-U Li | Kyōu Shooku 杏雨書屋 Library in Osaka, Japan |

| Skt. | Sanskrit |

| Ch. | Chinese |

| J. | Japanese |

| EMC | Early Middle Chinese (following Pulleyblank 1991) |

| LMC | Late Middle Chinese (following Pulleyblank 1991) |

| j. | juan 卷 |

| d.u. | Date unknown |

| * | Reconstructed |

| 1 | See (Brock and Coakley 2011, pp. 99–100). Jingjiao (景教) is a term coined during the time of the clergyman Jingjing (景淨), known as ‘Adhàm’ (Adam, fl. 8th to early 9th century), whose formal titles included priest, chorespiscopus, and papas of China” in Syriac (Hunter 2009, p. 73) and who was a key figure in the creation of the JJB. The term was adopted by Christians in 745 (lunar month 9 of the 4th year of the Tianbao reign 天寶四載九月) possibly to prevent confusion with other ‘Persian’ groups in China, notably Zoroastrians and Manichaeans, or to distinguish Christianity’s origins (cf. Tang huiyao, j. 49. 10–11; Forte 1996b, pp. 353–56; Kotyk 2024, p. 124). Often paired with the toponym “Da Qin” (大秦), it appears in the JJB inscription (see below) and other surviving texts. The labels “Nestorian” (after Nestorius, bishop of Constantinople (reigned 428–431), who had been condemned as a heretic at the Council of Ephesus in 431) and “Chinese Nestorian”, once mistakenly applied to Jingjiao, are now considered misnomers when referring to the “Church of the East” (cf. Brock 1996; Nicolini-Zani 2006, p. 23; 2023, p. 3). Syriac scholars and Sinologists now widely prefer using transliteration instead (cf. Malek and Hofrichter 2006, pp. 12, 15–16; Takahashi 2008; Deeg 2006a, 2006b). For a detailed analysis of the term “Jingjiao景教”, see (Ferreira 2014, pp. 210–11; L. Tang 2002, p. 130; Baum and Winkler 2006, pp. 228–57; Deeg 2006a, p. 92, note 4). |

| 2 | Deeg (2006a, pp. 91–92, note 6; 2023, p. 124). In Chinese, the word jing 景, which is a cognate of ying 英 (meaning “bright/brilliant”) and ying 影 (meaning “shadow/emanation”), can refer to the “iridescent emanation” by which the gods illuminate the interior of a religious adept’s (Daoist) body (cf. Kaltenmark 1969). Other scholars have suggested that jing (景) might also be a “calque” (or loan translation) for a word meaning “fear”, given that in Central Asia, Christians were historically known by the Middle Persian term tarsāg or New Persian tarsā, literally meaning “a (God) fearer” or “shaker”, which implied a “religion of fear/awe” (see Lieu 2013). The character 景 in the title is also written in a variant form with the top radical showing a “口” rather than a “日”. |

| 3 | “In the seventh month of the 12th year of the Zhenguan era (638 CE), the emperor said: ‘The Way has not a constant name, the Saints have not a constant mode; they establish the teaching to suit the region, that all living may be mysteriously save. The Persian monk Alopen, bringing texts and teachings from afar, has come to offer them to the ‘supreme capital.’ If we scrutinize their doctrinal purport, it is mysterious and transcendent non-action; it establishes the essentials of production and completion. As they are of help to the beings and of profit to men, it is proper to have time (texts and teachings) circulate ‘under the sky.’ Let the responsible authorities, therefore, in the Yining Quarter of the Capital, build one monastery, and ordain twenty-one persons” 貞觀十二年七月詔曰: 道無常名, 聖無常體; 隨方設教, 密濟群生. 波斯僧阿羅本, 遠將經教, 來獻上京. 詳其教旨, 玄妙無爲; 生成立要, 濟物利人, 宜行天下. 所司即於義寧坊, 建寺一所, 度僧廿一人. Tang huiyao 唐会要, j. 49, pp. 1011–12. Translation based on Pelliot INS 1996. For other translations, see (Legge 1888; Saeki 1911, 1916; Eccles and Lieu 2023). In addition to this recording, Du Huan 杜環, a war captive who was taken to Iraq c. 751, refers to Christianity as “the Law of Daqin” (大秦法). This account suggests that by the mid-eighth century, Christianity was also being recorded both officially at the state level and informally by the populace in connection with Daqin, See (Kotyk 2024, p. 125). |

| 4 | The initial decades during which Zoroastrianism and Christianity established themselves in China coincided with the conquests of Iran and the displacement of certain members of their royalty to China. Throughout the years, it is probable that reports would have emerged alongside the arrival of refugees and firsthand witnesses. Nonetheless, motivations such as seeking refuge from exile are not explicitly documented in the official Chinese diplomatic records. (Cf. Kotyk 2024, pp. 105–7; Nicolini-Zani 2022, p. 9; Thompson 2009). |

| 5 | cf. (Pelliot INS 1996, pp. 175, 251–52, 497–503 (JJB lines X–XI), esp. p. 499 (lines XII–XIII); Forte 1996b, p. 357; Drake 1936–1937, p. 305). |

| 6 | Cf. Edict of Emperor Wuzong 武宗 (issued Huichang 5, 8th month: 845) recorded in the “Basic Annals of Wuzong” 武宗本紀 in the Jiu Tang shu, j. 18, pp. 604–6. For an investigation on the suppression, see (Weinstein 1987, pp. 114–36). Various scenes of burning or banning Buddhist scriptures are depicted in Ennin’s 圓仁 (794–864) diary. See (Ru Tang qiufa xunli xing ji 入唐求法巡禮行記, p. 158; Reischauer 1955, pp. 332–33, 382, 388, 390). |

| 7 | While most historians interpret the imperial edict as primarily targeting Buddhism, the persecution that followed had severe consequences for Christianity. More than three thousand Jingjiao and Zoroastrian priests were forced to return to “lay” status, with many of their monasteries/churches likely having been destroyed. The Muslim scholar al-Nadim (d. 998) reports that in 987, a Christian monk made a journey to see what had happened to the Christians in China but could not find any. On the suppression’s impact on non-Buddhist communities, cf. (Weinstein 1987, pp. 89–93, 120–21, 133–34; Deeg 2006a, pp. 105–7; 2018b, pp. 50–55). |

| 8 | The authors extend their gratitude to the anonymous reviewer for highlighting that, “there exists considerable interest (implying skepticism) among Chinese scholars regarding the so-called ‘hiatus’” attributed to the Jingjiao church following the Tang dynasty. |

| 9 | Now the oldest known Christian relic in China, the stele inscription includes the original text of an edict issued by Emperor Taizong, dated to the 7th month of the 12th year of the Zhenguan 貞觀 era (=15 August to 12 September, 638): “[XII]…道無常名, 聖無常體; 随方設教, 密濟群生. 大秦國大德[*波斯僧]阿羅本, 遠將經像, 來獻上京. 詳其教旨, 玄妙無爲; 觀其元宗, 生成立要. 詞無繁説. 理有忘筌; [XIII] 濟物利人, 宜行天下. 所司即於京義寜坊. 造大秦[*波斯]寺一所. 度僧廿一人. [[XII] …The Way has not a constant name, the Saints have not a constant mode; they establish the teaching to suit the region, that all living may be mysteriously saved. The Da Qin (*Persian) monk Aluoben, bringing texts and images from afar, has come to offer them at the ‘supreme capital.’ If we scrutinize their doctrinal purport, it is mysterious and transcendent non-action; if we look at their fundamental principle, it establishes the essentials of production and completion; the words have no superfluous speech, the concepts have ‘the forgetting of the net.’ [XIII] As they are of help to beings and of profit to men, it is proper to have them (texts and images) circulate ‘under the sky.’ Let the responsible authorities, therefore, in the Yining Quarter of the Capital, build one Da Qin (*Persian) Monastery, and ordain as monks twenty-one persons.]” Concerning the edict’s reconstruction and explanation, cf. Forte (1996b, p. 349–57), with reconstruction marked (*) (see also Pelliot’s original notes in Pelliot INS 1996, esp. p. 175, and note below on the version of the edict recorded in the Tang huiyao 唐会要, j. 49). |

| 10 | Da Qin (大秦) is the Chinese term used in the JJB (781) to refer to the country from which East Syriac Christianity originated. In Chinese historical sources, it denotes the Eastern Roman (or Byzantine) Empire, see (Saeki 1916, pp. 181–84; Takahashi 2019, p. 625; Pulleyblank 1999, pp. 71–79). However, according to Forte (1996b, p. 357), an imperial edict issued in 745 ordered all “Bosi” (波斯, i.e., “Persian”) monasteries and literature to be referred to as Da Qin; thus, the appearance of Da Qin in contemporary Jingjiao literature may have originally denoted “from Persia” (cf. the reconstructed 638 edict above). Scholar Nakata Mie suggests that the term “Bosi” as in bosi seng 波斯僧 indicated the Tocharian (Tuhuoluo 吐火羅) region at the time since the Persian Sasanian Empire had already fallen in the mid-seventh century. She thus proposes that some Christian missionaries probably came from the Tocharian region; see (Nakata 2011, p. 176). From the Christian perspective, Da Qin might have referred to Byzantium or the Levant, the eastern part of the Mediterranean in this case (see Kotyk 2024, p. 106). |

| 11 | The stele is datable by its Chinese and Syriac colophones to Sunday, 4 February of the year 781 (Western calendar), the second year of the era Jianzhong 建中, first month (Taicu yue 太蔟月), seventh day Da yaosenwen(-ri) 大耀森文(日), (cf. Pelliot INS 1996, pp. 308–9). |

| 12 | See (Pelliot INS 1996, pp. 5–57, 58–94, 147–66; Saeki 1916, pp. 2–4, 53–61; L. Tang 2002, pp. 17–25; Nicolini-Zani 2023, p. 1, 6–7, notes 19 and 20). For a comprehensive list of recent research, see also Morris and Cheng (2020) and (Wu 2015a, 2015b). |

| 13 | |

| 14 | For a summary of the research undertaken by Japanese scholars, see (J. Zhang 1969; Deeg 2009, p. 143). |

| 15 | (H. Chen 2012). Chen’s study pointed out the parallelism in syntactic structure and terminology between the sūtra and the Trinitarian hymn, showing, among other things, that Christians used Buddhist literary models to transmit their teachings. |

| 16 | See also (Matsumoto 1938; Gong 1958, 1960a, 1960b; X. Luo 1966; Weng 1996; H. Chen 2006a, 2006b, 2015). For a more recent study, see (H. Chen 2006a, pp. 93–113). |

| 17 | |

| 18 | See (Deeg 2004, pp. 155–56; 2006a; 2006b, p. 120; Nicolini-Zani 2023, pp. 12–17; Wickeri 2004, p. 49). Deeg sharply critiques early Western interpretations of Jingjiao texts, highlighting their biases toward Christian theological ideologies and significant lack of familiarity with classical Chinese and the religious terminology of the Tang period, leading to numerous misreadings. He further contends that most of these scholars demonstrate a superficial understanding of the religious vocabulary of Buddhism and Daoism, both of which had a clear and profound influence on the Sino-Christian terminology of the time (Deeg 2004, p. 156). For examples of so-called “Christianized” readings, see discussions by (Saeki 1916, pp. 71–75, 118–61; Moule 1930; L. Tang 2002); for “Daoist–Christian” ideas, see (Palmer 2001, pp. 129–41). See also the records in the Datang zhenyuan xu Kaiyuan shijiao lu 大唐貞元續開元釋教錄 T 55, no. 2156, p. 756a18-28 and the Zhenyuan xinding Shijiao mulu 貞元新定釋教目錄T 55, no. 2157, p. 892a8-16 (discussed below); and by (Takakusu 1896, pp. 589–91; Deeg 2006a, pp. 97–98; 2009, p. 144; 2023, pp. 125–27; H. Chen 2006a, pp. 93–113). |

| 19 | For further discussion, see (L. Tang 2002, pp. 20–24, 105–6; Y. Zhang 2018; Deeg 2023; Forte 1996b, pp. 353–54). |

| 20 | Haneda and Saeki suggest “A-lo-pen/Aluoben 阿羅本” (Pulleyblank 1991, pp. 23, 32, 203: EMC/LMC = *ʔa-la-pən’/*pun’/*A-la-pwonX) could be a Chinese transcription of “Abraham”. See (Saeki [1937] 1951, p. 85, note (10); 1935, pp. 510, 597; Pelliot INS 1996, p. 379). The name Alouben is likely a Chinese phonetic rendering of a foreign name. 夲 is an older variant of 本, cf. (Takahashi 2008, p. 639; Deeg 2004, p. 160; 2018a, p. 239; 2009, pp. 147–49) posits a Middle Iranian origin (*Aḍ(ḍ)ābān = Ardabān). For the Chinese text of the inscription discussing Aluoben, see (Pelliot INS 1996, pp. 376, 497–503), JJB lines X–XI. Eccles and Lieu note, “[it] perhaps represents the Syriac name Yahballaha, ‘Gift of God’” (See Eccles and Lieu 2023, p. 65, note 49). |

| 21 | The JJB in Tang huiyao 唐會要, j. 49, pp. 1011–12. See also (Leslie 1981–1983, p. 282; Pelliot INS 1996, pp. 349–59). |

| 22 | Chu Sanzang jiji 出三藏記集, T no. 2145, vol. 55. Translation based on Liebenthal with amendments. Cf: (Liebenthal 1956, pp. 88–99). |

| 23 | See Gaoseng zhuan 高僧傳 T no. 2059, vol. 50 347a20–22. For further discussion, see (Itō 1996, pp. 65–91; Y. Chen 1933); English translation based on Zürcher ([1959] 2007, p. 184) with amendments. |

| 24 | Comparative Philosophy also notes the value of this methodology; see (S. Chen 2024; Cheng and Bunnin 2002, p. 354; Ouyang 2016, pp. 42–43). |

| 25 | These documents include the seven manuscripts on Jingjiao discovered at Dunhuang 敦煌 in the early 20th century (cf. Pelliot 1909, pp. 37–38; Saeki 1916, p. 65; [1937] 1951, pp. 125–319; Moule 1930, pp. 52–64), along with the stone pillar dating to the 8th day of the twelfth month of the 9th year of the Yuanhe 元和 era of the Tang dynasty (c. 814/15) excavated in Luoyang 洛陽 in 2006 (see below). The Dunhuang manuscripts, sometimes referred to as the “corpus nestorianum sinicum” (Sánchez 2019), include the following:

Scholars render these titles in various ways. Saeki ([1937] 1951) and L. Tang (2002) have published complete English translations with annotations, while Deeg has criticized several English interpretations (cf. Deeg 2004, pp. 153–56; 2006a, p. 93; 2006b, pp. 116–17; 2020b, pp. 112–16). The authenticity of these documents also remains a subject of controversy. Lin, Wushu 林悟殊 and Rong, Xinjiang 榮新江 have argued that titles (6) and (7) are modern forgeries created by book dealers (Lin and Rong 1992, p. 34; 1996, p. 13; Lin 2000, p. 81; Rong 2013, pp. 334–37; 2014, pp. 280–89)—a claim that H. Chen (1997) and Q. Feng (2007) also verified. The legitimacy of titles (1) and (2) has also been scrutinized. For an overview, see (Riboud 2001; Nicolini-Zani 2006, pp. 23–44; Yin 2024, pp. 158–62). For the purposes of this work, we refer to the titles as presented by Takahashi (2019, pp. 626–29), referencing some translations by Saeki (1916, [1937] 1951), L. Tang (2002), and Deeg (2006a, 2006b, 2009), with revisions. |

| 26 | Reproduced in Saeki ([1937] 1951, pp. 13–29). Saeki ([1937] 1951, p. 147) suggested that Xuting 序聽 is a Chinese approximation of “Ye-su” (Jesus); however, Deeg (2004, 2006a, 2006b) refutes this claim. Haneda (1918, 1958, vol. 2, p. 250) argues that Mishisuo 迷詩所 is a scribal error for Mishihe 迷詩訶 or “Messiah”. For a detailed early study, see Haneda (1958, pp. 240–69). See Palmer (2001, pp. 159–68) for an English translation. |

| 27 | Saeki ([1937] 1951, pp. 113–17) dates the text before 638; however, Deeg (2004) remains skeptical of dating. |

| 28 | Takakusu bought the original manuscript of this text from a Chinese seller in 1922. See (Q. Zhu [1993] 1997–1998, p. 118; Ferreira 2014, pp. 169–70) for a translation of the JJB, which cites the date (“the ninth year of the Zhenguan reign [i.e., 635]”). |

| 29 | See Yishen lun 一神論, The Lord of the Universe’s Discourse on Alms-giving, Part III (Shizun bushi lun disan 世尊佈施論第三). Translation based on (R. Huang 2023, p. 378), with amendments. |

| 30 | Xu ting Mishisuo jing 序聽迷詩所經, j. 1: T 54, no. 2142, p. 1286b14-15; and T 54, no. 2142. 1286c15–17: “There are living beings [who] have the need to think about the retribution of their own [actions, and] the Heaven-Honoured One welcomes hard efforts [to improve]. [When he] first created the living beings, the principles for living beings were not far from the buddhas: [he] created the human’s self with a will of his own, and good [actions] lead to good merit, [but] evil [actions] lead to bad karma 有眾生先須想自身果報, 天尊受許辛苦. 始立眾生, 眾生理佛不遠. 立人身自專: 善有善福, 惡有惡緣”. See also (L. Tang 2002, p. 131; Deeg 2023, pp. 133–36). |

| 31 | Cf. Deeg (2023, p. 136 note 61) on context. |

| 32 | Xu ting Mishisuo jing 序聽迷詩所經, j. 1, “事天尊之人, 爲説經義, 並作此經. 一切事由, 大有歎處, 多有事節, 由緒少. ...人合怕天尊, 每日諫誤, 一切眾生, 皆各怕天尊並綰攝, 諸眾生, 死活管帶, 綰攝渾神. ...眾生, 若怕天尊, 亦合怕懼聖上. 聖上前身福私, 天尊補任, 亦無自乃天尊耶? 屬自作聖上, 一切眾生皆取聖上進止. ....第三, 須怕父母, 祗承父母, 將比天尊及聖帝. 以若人先事天尊及聖上及事父母不闕, 此人於天尊得福, 不多此三事. .....一種先事天尊, 第二事聖上, 第三事父母. ... T 54, no. 2142, pp. 1286c28-1287a1, a5-10, a16-20. In this context, the term “God” is rendered through the binomial term Tian zun 天尊, which Tam (2019, p. 5) characterizes as “that which is the highest” and “that which is supremely honored”. However, this Chinese expression has its origins in Buddhism, functioning as a translation of deva or bhagavat (Hirakawa 1997, p. 335), the latter being an epithet for the Buddha. The Christian interpretation may be understood as “Lord of Heaven”, as elucidated by Saeki ([1937] 1951, p. 167); nonetheless, the term was initially borrowed from Buddhist literature. |

| 33 | Xu ting Mishisuo jing 序聽迷詩所經, j. 1, T 54, no. 2142, p. 1286c4-7.? |

| 34 | Xu ting Mishisuo jing 序聽迷詩所經, j. 1, “何因?眾生在於罪中, 自於見天尊....眾生無人敢近天尊, 善福善緣眾生, 然始得見天尊. ....天尊説云: ‘所有眾生, 返諸惡等, 返逆於尊, 亦不是孝; 第二願者, 若孝父母, 并恭給所有眾生, 孝養父母, 恭承不闕, 臨命終之時, 乃得天道”. T 54, no. 2142, p. 1286c4-7, p. 1287a27-b1; Deeg (2023, pp. 133–36). |

| 35 | Yishen lun一神論, j. 1, “Yitian lun diyi 一天論第一”, “……喻如魂魄五蔭不得成就, 此魂魄不得, 五蔭故不能成”. Cf. Tonkō hikyū, p. 32, lines 91–92. |

| 36 | Yishen lun一神論, j. 2, “Yu di’er 喻第二”, “天下萬物盡一四色”. Cf. Tonkō hikyū, p. 28, line 60. |

| 37 | See (Saeki [1937] 1951, p. 148; L. Tang 2002, pp. 131–33). Wang Ding highlights evidence in the transcriptions of Jesus’s name that indicates at least at the beginning of the Christian mission in China, an organization in translating praxis was still lacking, and missionaries were indebted to working with the central government (D. Wang 2006, pp. 153–60). |

| 38 | Chu sanzang ji ji, j. 6, 46.2.19./Cf. Chu sanzang ji ji, j. 6, 46.3.3 (Kang Senghui’s 法鏡經序): 年在齠齔. 弘志聖業, but this refers to both An Xuan and Yan Fotiao. Chu sanzang ji ji, j. 13, “安玄. 安息國人也. 志性貞白深沈有理致. 爲優婆塞. 秉持法戒豪釐弗虧. 博誦群經多所通習. 漢靈帝末. 遊賈洛陽有功. 號騎都尉. 性虛靜溫恭. 常以法事爲己務. 漸練漢言, 志宣經典. 常與沙門講論道義. 世所謂都尉言也. 玄與沙門嚴佛調. 共出法鏡經. 玄口譯梵文. 佛調筆受. 理得音正. 盡經微旨郢匠之美, 見述後代”. T 55, no. 2145, p. 96a9-16; (Liang) Hui Jiao. Gaoseng zhuan, j. 4.///T. 2059, 324b25-c7. For an English translation of most of the biography see (Tsukamoto 1985, vol. 1, pp. 496–97, n. 15). |

| 39 | Chu sanzang ji ji, T 55, no. 2145, p. 96a9-16. |

| 40 | Gaoseng zhuan 高僧傳, j. 4, “時河南居士竺叔蘭, 本天竺人, 父世避難, 居于河南. 蘭少好遊獵, 後經暫死, 備見業果. 因改勵專精, 深崇正法, 博究眾音, 善於梵漢之語. 又有無羅叉比丘, 西域道士, 稽古多學, 乃手執梵本, 叔蘭譯爲晉文, 稱爲《放光波若》”. T 50, no. 2059, p. 346c1-6; Chu sanzang ji ji, j. 7, “放光于闐沙門無叉羅執胡竺. 叔蘭爲譯言”. T 55, no. 2145, p. 48a6-9; (Zürcher [1959] 2007, p. 65). |

| 41 | According to Jingtai’s 靜泰 Datang dongjing da’ai si yiqie jing lun mu xu 大唐東京大敬愛寺一切經論目序 [Preface to the Catalogue for the Great Tang Eastern Capital Jingai Monastery’s complete Buddhist canon (or Tripiṭaka), Including all Scriptures and Śāstras], “In the years of the Xianqing reign (651–661), [based on Emperor Gaozong’s 高宗 decree] Ximing Monastery completed an imperial collection of Buddhist scriptures, and it was even more refined and sophisticated; organized to the utmost degree, and perfectly complete. The Vinaya Master Daoxuan 道宣 completed the Preface for the Catalog” 顯慶年際, 西明寺成御造藏經, 更令隱煉, 區格盡爾, 無所間然. 律師道宣又爲錄序. Zhongjing mulu 眾經目錄, T no. 2148, vol. 55: 1.181a1-3./T55, no. 2148, p. 181a1-10. |

| 42 | Chu sanzang ji ji, j.12: “《皇帝勅諸僧抄經撰義翻胡音造錄立藏等記》第二”, T 55, no. 2145, p. 93b6-7. |

| 43 | Scholars Bai Yu (Bai 2023, p. 53, note 32) and Chen Huaiyu (H. Chen 2015, pp. 52–57) have noted that Jingjing’s engagement with particular Buddhist themes like “state protection” (守護國界) (on this concept, cf. (Tsukinowa 1956, pp. 435–38)) possibly reflects his strategy of aligning Jingjiao teachings with prevailing religious and political discourses. In this case, his integration of elements established by Tang-era esoteric Buddhist teachings, including certain dhāraṇī 陀羅尼 texts (Orzech 1998, pp. 135–67), already associated with state protection and governance, reinforced the legitimacy of Jingjiao’s text in Tang China. |

| 44 | Although the extent of Jingjing’s direct interaction with Prajña remains uncertain, the similarities between their works suggest that such contact played a critical role in Jingjing’s adaptation of Buddhist elements (Bai 2023). The Zhixuan anle jing shares thematic and visual parallels with Prajña’s Dasheng bensheng xindi guan jing 大乘本生心地觀經 (Xindi guan jing), raising the possibility that Jingjing drew inspiration from Prajña’s text (Bai 2023, pp. 53–54). If this is the case, the composition of the Zhixuan anle jing would likely postdate the Xindi guan jing, and it is plausible that Jingjing participated in or was influenced by Prajña’s process of textual synthesis drawing on various other Chinese Buddhist scriptures. Chen Huaiyu also points to the potential similarities between the Xindi guan jing and Jingjing’s other text, titled San wei meng du zan 三威蒙度讚, suggesting that the structure and language of the former may have inspired Jingjing’s composition (H. Chen 2006a, pp. 93–113). |

| 45 | According to Pelliot, hu 胡 could have meant “Sogdian” in this case, implying Jingjing came from Sogdiana. Forte, however, has objected to this by recalling that Jingjing is said to be a “Persian” monk and that during the Tang period, hu frequently referred to “Persian” (Iranian). Forte (1996c, pp. 442–49, esp. p. 446, note 43). |

| 46 | Datang zhenyuan xu Kaiyuan shijiao lu 大唐貞元續開元釋教錄 j. 1, T 55, no. 2156, p. 756a18-28 and the Zhenyuan xinding Shijiao mulu 貞元新定釋教目錄 j. 17, T 55, no. 2157, p. 892a8-16; cf. also (Takakusu 1896, pp. 589–91). Prajñā retranslated the text from Sanskrit in around 788/91. The original seven-fascicle version rendered by Jingjing and Prajñā is currently missing. The extant enlarged (ten-fascicle) later version of this sūtra (T 08, no. 261, p. 865a), dated to the 4th year of the Zhenyuan reign (c. 788; cf. Forte 1996a, pp. 442, 444, note 36), is now solely attributed to tripiṭaka Prajña. |

| 47 | Contemporary accounts consistently record Buddhism’s dominance during this period. See, for example, the “Stele Inscription and Preface at Chongyan Monastery in Yongxing County, Ezhou” Ezhou yongxing xian chongyan si beiming bing xu 鄂州永興縣重岩寺碑銘並序 compiled during the Changqing 長慶 era (821–824) by Shu Yuanyu 舒元輿, preserved in the Quan Tangwen 全唐文 [Complete Tang Prose], j. 727, p. 7498. The use of Buddhist and other terminology illustrates that the early Christian mission aimed to convey its message effectively to establish a presence in the country. Moreover, as Kotyk (2024, p. 128) notes, Alopen was required to provide a comprehensive account of his teachings to the ruling authority. The urgency of this situation explains the short time frame of only about three years between his arrival and the presentation of the earliest versions of Jingjiao texts to the emperor. There was insufficient time to deliberate on vocabulary or to develop a distinct lexicon that would clearly differentiate Christian theological concepts from Buddhist ideas. |

| 48 | Cf. above (Bai 2023, p. 53 and note 32; H. Chen 2015, pp. 52–57). |

| 49 | See (Deeg 2023, pp. 127–28). |

| 50 | Some scholars have suggested that the books of the Bible were likely translated, but none still exist. The authors are grateful to Jeffrey Kotyk for bringing this detail to our attention. |

| 51 | |

| 52 | (Pelliot INS 1996, p. 231, note 98; Forte 1996b, pp. 350, 351, 352, note 7). The original text of the 638 inscription on the JJB is reconstructed as follows: “The Persian Monk Alopen, bringing texts and images from afar, has come to offer them at the ‘supreme capital’” 波斯僧阿羅本, 遠將經像, 來獻上京. Moule (1930, p. 67), Forte (1996b, p. 354, note 13) note that jing xiang (經像) is preferred to jing jiao (經教) and that such an expression concerning religious texts and images brought by monks from abroad was normal and usual. See, for instance, Xuanzang’s 玄奘 biography, Da Tang Da Ci’ensi sanzang fashi zhuan 大唐大慈恩寺三藏法師傳 6.252bl5. They posit that the version recorded in the Tang huayao (波斯僧阿羅本, 遠將經教, 來獻上京) initially omitted this sentence and was later modified. “It is possible that xiang 像 was corrected in jiao 教 on the basis of the text of the Tang huiyao, which was itself already corrupt” (Forte 1996b, p. 354, note 13). |

| 53 | (Q. Feng 2007, pp. 28–31; Z. Luo 2007, p. 30; N. Zhang 2007, p. 65; Nicolini-Zani 2013, pp. 141–60). Sixteen high-quality photos of rubbings of the Pillar from Luoyang were published in Ge (2009, Pl. I–XII). |

| 54 | Nicolini-Zani (2009). “The Tang Christian Pillar from Luoyang and Its Jingjiao Inscription a Preliminary Study”. Monumenta Serica, vol. 57, pp. 99–140. |

| 55 | Ken Parry notes that such examples showcase “additional imagery not previously seen in Christian art of the Tang period. Although it is unclear when and where the motif developed, the iconography of two flying figures flanking the cross on a lotus is highly significant. Before the discovery of the pillar (c. 814/15), this feature was known only from the Yuan period…” See Parry (2016, p. 28). |

| 56 | See, for example, Quanzhou 泉州 carvings dated to the 13th and 14th centuries. Cf. (Foster 1954; Parry 2003, 2006). |

| 57 | This cross pattée depicted in the JJB and Pillar from Luoyang, characterized by its slightly indented arms narrowing toward the center, is adorned with gems (or pearl roundels), small flowers, or flame patterns, along with a central cluster of small dots forming a circle. These elements closely resemble crosses found on contemporaneous Nestorian Sogdian coins, indicating an influence from Sassanian Persian styles, including a mixture of Buddhist and Zoroastrian motifs (Cf. Zhou 2020, pp. 58–59, 81–83, 115; Yin and Zhang 2016, pp. 1–25; Nicolini-Zani 2009; Niu 2008, p. 2). |

| 58 | Similarly shaped flying figures or apsara can be seen in carvings of the Longmen 龍門 caves (outside Luoyang, in the same area where the pillar was found), but are also frequently represented in paintings of the Dunhuang caves. (Nicolini-Zani 2009, p. 106). Nevertheless, there remains ongoing debate regarding the accurate identification of these flying figures within Jingjiao iconography. Some scholars interpret them as “angels” (Ge 2014, pp. 1–8; L. Tang 2009, pp. 109–32), while others suggest they represent devas or apsaras from Indian and Central Asian traditions (cf. Z. Luo 2007, pp. 32–44; N. Zhang 2007, pp. 65–73). Given the uncertainty, this discussion will use the term “flying figures” for convenience. |

| 59 | A similar pattern appears in the 9th century Tang dynasty fragmentary Jingjiao silk painting of a Christian figure (possibly Jesus Christ) discovered by Aurel Stein in Cave No. 17 at Dunhuang. However, the details of the image remain unclear (see discussion below). |

| 60 | Scholars note that the lotus image was used in India before the emergence of Buddhism and may have even been influenced by ancient Persian and Egyptian iconography (Ward 1952, pp. 136–37). As Coomaraswamy (1935, p. 19) states, “All birth, all coming into existence is in fact a being established in the Waters, and to be established is to stand on any ground (prthivi) or platform of existence; he who stands or sits upon the lotus”. Nonetheless, Buddhist iconography redefined the lotus into a distinctive symbol of purity, transformation–rebirth, and ultimate enlightenment. In the Chinese context, depictions of Buddhas and celestial beings in the Dunhuang murals frequently reflect the concept of the “lotus in Heaven”, symbolizing birth through transformation from a lotus into a Buddha or celestial being (Yoshimura 2009, pp. 37, 40, 127). |

| 61 | Cf. (Chen et al. 2010, pp. 21–29; Mu 2019, pp. 51–57). Nonetheless, we do not seem to find lotuses on Sasanian silver, and it is important to note that Eastern Iran was less Persian and more reflective of its own cultural sphere, namely Indo-Iranian. |

| 62 | Regarding dating, see (R. Whitfield 1982, pl. 25, Figure 76). |

| 63 | See British Museum Collection: https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/A_1919-0101-0-48 (accessed on 16 February 2025). |

| 64 | Cf. (Stein 1921, p. 866 (note)). The picture is listed Serindia, II, p. 1050. Col. 2, with the identification number Ch. XLIX. 001. |

| 65 | (Stein 1921, pp. 1050–51). “[]” indicates amendments added by the authors for readability of text. |

| 66 | (L. Tang 2020, pp. 245–46). Tang notes, given that Cave No. 17 in Dunhuang was sealed off during the 11th century and the painting was produced after the 9th century, the only form of Christianity in China of that period was the Jingjiao Church (idem p. 252). |

| 67 | |

| 68 | Cf. (Matsumoto 1980, pp. 46–47). |

| 69 | The staff depicted in the image is highly fragmentary and uncharacteristic of traditional representations of Kṣitigarbha, who is typically shown holding a staff in his right hand and a cintāmaṇi (a “wish-granting jewel” 如意寶珠) in his left. In this image, however, the figure holds the staff in its left hand, suggesting that it may intend to represent a “non-Buddhist” figure possibly borrowing from Buddhist iconography. Cf. (L. Tang 2020, p. 248). |

| 70 | |

| 71 | (Parry 1996, pp. 143–62; Ren and Meng 2024; Matsumoto 1980, pp. 46–47) argues that the figure is based on the paintings of Greek figures of the Sassan Dynasty. |

| 72 | See Maréva U (2024, pp. 112–14) for a detailed account of this Monastery’s icons’ original use in situ. |

| 73 | Cf. (Liang 2013, pp. 39–41). |

| 74 | In the postscript to the Zun jing 尊經, it states the following: “In the 9th year of the Zhenguan (635) reign, under Tang Emperor Taizong, the Great Venerable monk of the Western Regions, Alopen, arrived in China and addressed the throne in his native tongue/language. Fang Xuanling and Wei Zhang spoke as translators 唐太宗皇帝貞觀九年, 西域太德僧阿羅本屆于中夏, 並奏上本音, 房玄齡, 魏徵宣譯奏言. Cf.: T 54, no. 2143, p. 1288 c22–23; translation following (Kotyk 2024, pp. 122–23), with ammendments. |

| 75 | JJB Line XI (Pelliot INS 1996, p. 489). The reason behind Emperor Taizong’s decision to endorse the Jingjiao teachings is still uncertain. However, it might have been influenced by the perception of Alopen and other Jingjiao missionaries as refugees. |

| 76 | [I–XXXII] Indicates lines of JJB, following Pelliot INS (1996). |

| 77 | |

| 78 | JJB Line XI (Pelliot INS 1996, p. 489). |

| 79 | Inscription text: following Pelliot INS (1996, pp. 497–503); English translation based on Eccles and Lieu (2023), with adjustments. |

| 80 | “Basic Annals of Taizong” 太宗本紀 Jiu Tangshu 舊唐書, j. 1. Translation by Author(s). |

| 81 | tianzun (天尊), cf. (Deeg 2023, p. 131 and note 24, pp. 133–34). |

| 82 | Xu ting Mishisuo jing 序聽迷詩所經, j. 1: T 54, no. 2142, p. 1287a8-9. |

| 83 | Concerning the use of “”, an “honorific space” placed before the address of shengshang “聖上”, cf. (Deeg 2023, p. 136, note 61). |

| 84 | Xu ting Mishisuo jing 序聽迷詩所經, j. 1: T 54, no. 2142, p. 1287a9-11. |

| 85 | The translation of the last two lines remains obscure and inconclusive, as they appear to contain corrupted phrases—shengshang wei xu qinjia xiling, shengshang gongdian yu zhufo qiu de (聖上唯須勤伽習倰, 聖上宮殿於諸佛求得). Deeg (2023) speculates that, given the text’s overall pejorative tone toward buddhas, jia (加) should be corrected to jia (伽), and qiu (求) in the second phrase should be jiu (救), in this context, meaning “to hold back” or “to prevent”. However, this interpretation remains speculative, as some syntactical issues remain unresolved. |

| 86 | Xu ting Mishisuo jing, T 54, no. 2142, p. 1287a23–26. The term “buddha(s)” (佛) referenced here is differentiated from the binominal Tian zun (天尊) “Heaven-Honored One” (God). As noted by Kotyk (2024, p. 127), these “buddhas” seem to imply ‘angels.’ However, this represents an irregular application of the Chinese terminology. The notion that Christians might entertain could arise from a somewhat loose understanding of Mahāyāna. Buddhas, such as Śākyamuni in the current era and Amitābha in the realm of Sukhāvatī, are “emanation bodies” (Skt: nirmāṇa-kāya) of a superior transcendental body (dharma-kāya). They inherently manifest in response to the suffering experienced by sentient beings. This prompts the inquiry regarding whether they possess free will or function automatically as “emanations,” in contrast to ordinary sentient beings, who perceive themselves and others as separate entities while making deliberate choices (Kotyk 2024, p. 127). Regardless of the interpretation, their designation in this context suggests a pejorative perspective, as they do not embody an “ultimate” source of assistance or a pathway to salvation. |

| 87 | JJB Line XI (Pelliot INS 1996, p. 489). |

| 88 | Tang scholar Wei Shu 韋述 (d.u.?–757) in 720, in his “New Records of the Two Capitals” (Liangjing xin ji 兩京新記), documents that there were “once/formerly Persian and Iranian monasteries” 舊波斯胡寺 on “the north of the Eastern Ten-character Street” 十字街東之北, in the Yining Quarter 義寧坊; and on “the east of the Southern Ten-character Street” 十字街南之東, in the Liquan Quarter 禮泉坊 in Chang’an 長安. Cf. Liangjing xin ji 兩京新記 3. (6. p. 191n–192a); (Pelliot INS 1996, p. 451 and note 66). |

| 89 | See, for example, (Thundy 1989, 1993; Chartrand-Burke 2008). These similarities are sometimes explained historically, with the suggestion that the stories were transmitted along trade routes from the East to the Greco-Roman world, or from Egypt to the north, and later adapted by early Christians to fit the life of Jesus. At other times, phenomenological explanations are proposed, viewing the Infancy Gospel of Thomas as a parallel but independent development within other religious traditions. |

| 90 | Some scholars remain skeptical about these connections while acknowledging the textual and narrative similarities between the portrayal of Jesus in the Infancy Gospel of Thomas and that of the Buddha as a child. See Aasgaard (2009–2010, pp. 86–88; 2022, p. 86) and Chartrand-Burke (2001, pp. 81–82). For further details, see (ibid., pp. 37–40, 299–302). Regarding the discussions surrounding the similarities between Śākyamuni and Jesus as presented in the Gospel of Thomas, refer to (Brockman 2003). |

| 91 | |

| 92 | For instance, Wiesehöfer (2010, p. 132) observes that the Sasanians “used Christian dignitaries as ambassadors and advisers.” This aspect of diplomacy is also discussed by Kotyk (2024, pp. 106–8). |

References

Primary Sources

Chu sanzang ji ji 出三藏記集 [Compilation of Notes on the Translation of the Tripiṭaka]. Total 15 juans. Initially compiled by Sengyou 僧佑 (445–518) in 515. T no. 2145, vol. 55 [Also: Chu sanzang ji ji 出三藏記集. 1995. Beijing 北京: Zhonghua Shuju 中華書局.Datang zhenyuan xu Kaiyuan shijiao lu 大唐貞元續開元釋教錄 [Catalogue of the Teachings of Śākya[muni] (Buddhist Texts) from the Kaiyuan [Era], Continued from the Zhenyuan [Era] of the Great Tang/Supplementary Catalog of Teachings from the Kaiyuan Period in the the Zhenyuan Era of the Great Tang]. Total 3 juans. Compiled by Yuanzhao 圓照 (fl. second half of 8th century) in 794. T no. 2156, vol. 55.Gaoseng zhuan 高僧傳 [Biographies of Eminent Monks]. Total 14 juans. Compiled by Huijiao 慧皎 (497–554) between 519–520. T no. 2059, vol. 50.Jiu Tang shu 舊唐書 [Old History of the Tang]. Total 200 juans. Compiled by Liu Xu 劉昫 (888–947), et al., in 941–945. Beijing 北京: Zhonghua shuju 中華書局, 1975.Quan Tangwen 全唐文 [Complete Tang Prose]. Total 1000 juans. Compiled by Dong Gao 董誥 (1740–1818), and others. Beijing北京: Zhonghua shuju 中華書局, 1983.Ru Tang qiufa xunli xing ji 入唐求法巡禮行記 [Record of Travel to the Tang in Search of the Dharma, Jp. Nittō guhō junrei kōki]. Total 4 juans. Composed (c. 838–847) by Japanese monk Jp. Ennin (Ch. Yuanren) 圓仁 (fl. 794–864); collated by Gu Chengfu顧承甫, and He Quanda 何泉達. 1986. Shanghai上海: Shanghai guji chubanshe 上海古籍出版社.Tang huiyao 唐會要 [Institutional History of the Tang Dynasty/Essential Regulations of the Tang]. Total 100 juans. Compiled by Wang Pu 王溥 (922–982) in the Northern Song period 北宋 (960–1126), completed c. 961. Wang Pu’s work is the continuation of Su Mian’s 蘇冕 Hui yao 會要 in 40 juans (completed 804) and of the Xu Hui yao 續會要of Yang Shaofu 楊紹復 and others in 4 juans (completed 853). Collated edition: Beijing 北京: Zhonghua shuju 中華書局, 1960. Also Shanghai 上海: Shanghai guji chubanshe 上海古籍出版社, 1999.Xin Tangshu 新唐書 [New Tang History]. Total 225 juans. Compiled/Supervised by Ouyang Xiu 歐陽修 (1007–1072), Song Qi 宋祁 (998–1061) and others during 1044–1060. Submitted to the throne in 1060. Beijing 北京: Zhonghua shuju 中華書局, 1975.Xuting mishusuo jing 序聽迷詩所經 [Sūtra of Hearing the Messiah/Book of Jesus-Messiah]. Total 1 juans. Compiled by Unknown (fl. mid-late 8th century). T no. 2142, vol. 54.Yishen lun 一神論 [Discourse on (Treatise of) the ‘One God’ (Monotheism)]. Total 3 juans. In Tonkō hikyū (pp. 23–54).Zhenyuan xin ding Shijiao mi lu 貞元新定釋教目錄 [Catalogue of Revised List of the Teachings of Śākya[muni] from the Zhenyuan [Era]]. Total 30 juans. Compiled by Yuanzhao 圓照 (fl. second half of 8th century) in 799–800. T no 2157, vol. 55.Secondary Sources

- Aasgaard, Reidar. 2009–2010. The Childhood of Jesus: Decoding the Apocryphal Infancy Gospel of Thomas. Cambridge: James Clarke & Co. [Google Scholar]

- Aasgaard, Reidar. 2022. Infancy Gospel of Thomas. In Early New Testament Aprocrypha: Ancient Literature for New Testament Studies. Edited by Christopher J. Edwards, Craig A. Evans and Cecilia Wassén. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, vol. 9, pp. 78–95. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, Yu 白宇. 2023. On the Jingjiao Text Zhixuan anle jing: Its Date and Use of Imagery. Monumenta Serica 71: 43–71. [Google Scholar]

- Baum, Wilhelm, and Dietmar W. Winkler. 2006. The Church of the East, A Concise History. London: I. B. Tauris. [Google Scholar]

- Beckwith, Christopher I. 2009. Empires of the Silk Road. A History of Central Eurasia from the Bronze Age to the Present. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brock, Sebastian P. 1996. The ‘Nestorian’ Church: A lamentable misnomer. In The Church of the East: Life and Thought. Edited by Jerry F. Coakley and Ken Parry. Bulletin of the John Rylands University Library of Manchester. 78/3: 23–35. Manchester: John Rylands University Library, pp. 1–14, Reprinted in Brock, Sebastian P. Fire from Heaven. Studies in Syriac Theology and Liturgy. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2006, no. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Brock, Sebastian P., and James F. Coakley. 2011. Church of the East. In The Gorgias Encyclopedic Dictionary of the Syriac Heritage, 1st ed. Edited by Sebastian P. Brock, Aaron Michael Butts, George Anton Kiraz and Lucas Van Rompay. Piscataway: Gorgias Press, pp. 99–100. [Google Scholar]

- Brockman, John. 2003. The Politics of Christianity: A Talk with Elaine Pagels. The Third Culture. Edge Foundation. July 15. Available online: https://www.edge.org/conversation/elaine_pagels-the-politics-of-christianity (accessed on 16 February 2025).

- Chartrand-Burke, Tony. 2001. The Infancy Gospel of Thomas: The Text, Its Origins, and Its Transmission. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada. Available online: http://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/obj/s4/f2/dsk3/ftp05/NQ63782.pdf (accessed on 16 February 2025).

- Chartrand-Burke, Tony. 2008. The Infancy Gospel of Thomas. In The Non-Canonical Gospels. Edited by Paul Foster. London: T. & T. Clark, pp. 126–38. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Huaiyu 陳懷宇. 1997. Suowei Tangdai Jingjiao wenxian liangzhong bianwei bushuo 所謂唐代景教文獻兩種辨偽補説 [Supplementary Notes on the Authentication of Two So-called Tang Nestorian Documents]. Tang Yanjiu 唐研究 [Journal of Tang Studies] 3: 41–53, (English summary, pp. 52–53). [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Huaiyu 陳懐宇. 2006a. The Connection between Jingjiao and Buddhist Texts in Late Tang China. In Jingjiao: The Church of the East in China and Central Asia, 1st ed. Edited by Roman Malek. London: Routledge, pp. 93–113. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Huaiyu 陳懐宇. 2006b. 第二屆中國和中亞的景教國際學術研討會綜述 [Summary of the Second International Symposium on Jingjiao in China and Central Asia]. Dao Feng: Jidujiao wenhua pinglun 道風: 基督教文化評論 [Logos & Pneuma: Chinese Journal of Theology] 25: 281–91. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Huaiyu 陳懷宇. 2012. Jingfeng fansheng: Zhonggu zongjiao zhi zhuxiang 景風. 梵聲: 中古宗教之諸相 [Jingfeng (Lit. ‘Radiant Breeze’; i.e., Nestorianism) and Fansheng (Lit. ‘Brahman Sound’; i.e., Buddhism): Aspects of Medieval Religions]. Beijing 北京: Zhongguo zongjiao wenhua chubanshe 中國宗教文化出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Huaiyu 陳懷宇. 2015. Tangdai Jingjiao yu Fodao guanxi xinlun 唐代景教與佛道關係新論 [New Discussions on the Relationship between Jingjiao and Buddhism-Taoism in Tang Dynasty]. Shijie zongjiao yanjiu 世界宗教研究 [Studies in World Religions] 5: 51–61. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Jian’guang 陳劍光, Yuanyuan Li 李圓圓, and Zhicheng Wang 王志成. 2010. Zhongguo Yashu jiaohui de lianhua yu wan zi fu: Fojiao chuantong yihuo Yali’an yichan 中國亞述教會的蓮花與萬字符: 佛教傳統抑或雅利安遺產? [Lotus and Swastika in Chinese Nestorianism: Buddhist Legacy or Aryan Heritage?]. Zhejiang daxue xuebao (renwen shehui kexue ban) 浙江大學學報 (人文社會科學版) [Journal of Zhejiang University (Humanities and Social Sciences)] 40: 21–29. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Jichun 陳繼春. 2008. Tangdai jingjiao huihua yicun de zai yanjiu 唐代景教繪畫遺存的再研究 [Re-examination of the Remaining Jingjiao Paintings of the Tang Dynasty]. Wen Bo 文博 [Relics and Museolgy] 4: 66–72. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Shaoming. 2024. Doing Chinese Philosophy: A Focus on Philosophical Methodology. Singapore: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Yinke 陳寅恪. 1933. Zhi Mindu xueshuo kao 支愍度學説考 [An Examination of the Theories of Zhi Mindu]. In Qingzhu Cai Yuanpei xiansheng liushiwu sui lunwenji 慶祝蔡元培先生六十五歲論文集. [Collected Essays in Honor of Professor Cai Yuanpei’s 65th birthday]. Guoli ZhongyangYanjiuyuan 國立中央硏究院. Reprinted in Chen Yinke wenji zhi er: Jinmingguan conggaochubian 陳寅恪文集之二 金明館叢稿初編 [Collected Writings of Chen Yinke No. 2: Jinmingguan Drafts, Vol. 1]. Shanghai 上海: Guji Chuban 上海古籍出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Chung-Ying, and Nicholas Bunnin. 2002. Contemporary Chinese Philosophy. Hoboken: Blackwell Publishers Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Coomaraswamy, Ananda Kentish. 1935. Elements of Buddhist Iconography. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, Reprinted in 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Deeg, Max. 2004. Digging out God from the Rubbish Heap—The Chinese Nestorian Documents and the Ideology of Research [景教・マニ教・イスラム教文獻]. In Chūgoku-shūkyō-bunken-kenkyū-kokusai-shinpojiumu, Hōkokusho 中國宗教文獻研究國際シンポジアン、報告書 [Proceedings for the International Symposium of Textual Research on Chinese Religions]. Edited by Takata Tokio 高田時雄. Kyōto 京都: Kyōto Daigaku Jinbun Kagaku Kenkyūjo 京都大学人文科学研究所, pp. 151–68. [Google Scholar]

- Deeg, Max. 2006a. The “Brilliant Teaching” The Rise and Fall of “Nestorianism” (Jingjiao) in Tang China. Japanese Religions 31: 91–110. [Google Scholar]

- Deeg, Max. 2006b. Towards a New Translation of the Chinese Nestorian Document from the Tang Dynasty. In Jingjiao: The Church of the East in China and Central Asia, 1st ed. Edited by Roman Malek. London: Routledge, pp. 115–31. [Google Scholar]

- Deeg, Max. 2007. The Rhetoric of Antiquity: Politico-religious Propaganda in the Nestorian Stele of Chang’an. Journal of Late Antique Religion and Antiquity 1: 17–30. [Google Scholar]

- Deeg, Max. 2009. Ways to Go and Not to Go in the Contextualization of the Jingjiao-Documents of the Tang Period. In Hidden Treasures and Intercultural Encounters. Studies on East Syriac Christianity in China and Central Asia, Proceedings of the Second Jingjiao Conference, University of Salzburg, ed. Edited by Dietmar W. Winkler and Li Tang. Berlin and Vienna: LIT. [Google Scholar]

- Deeg, Max. 2018a. Along the Silk Road: From Aleppo to Chang’an. In A Companion to Religion in Late Antiquity, Blackwell Companions to the Ancient World. Edited by Nicholas J. Baker-Brian and Josef Lossl. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 233–53. [Google Scholar]

- Deeg, Max. 2018b. Die Strahlende Lehre—Die Stele von Xi’an. Übersetzung und Kommentar. Vienna and Berlin: LIT Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Deeg, Max. 2020a. The ‘Brilliant Teaching’: Iranian Christians in Tang China and Their Identity. Entangled Religions 11: 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Deeg, Max. 2020b. Messiah Rediscovered: Some Philological Notes on the so-called ‘Jesus the Messiah Sutra.’. In The Church of the East in Central Asia and China. Edited by Samuel N. C. Lieu and Glen L. Thompson. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 111–19. [Google Scholar]

- Deeg, Max. 2023. Chapter 4: The Christian Communities in Tang China: Between Adaptation and Religious Self-Identity. In Buddhism in Central Asia III. Edited by Lewis Doney, Carmen Meinert, Henrik H. Sørensen and Yukiyo Kasai. Leiden: Brill, pp. 123–44. [Google Scholar]

- Drake, Francis S. 1936–1937. Nestorian Monasteries of the T’ang Dynasty. Monumenta Serica 2: 293–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Qing 段晴. 2003. Tangdai daqinsi seng xinshi 唐代大秦、寺僧新釋 [Daqin Si and (Daqin-)seng of the Great Tang—An attempt of a new explanation]. In Tangdai zongjiao xinyang yu shehui 唐代宗教信仰與社會 [Religious Faith and Society in the Tang Dynasty]. Edited by Xinjiang Rong 荣新江. Shanghai 上海: Shanghai Cishu chubanshe 上海辭書出版社, pp. 434–72. [Google Scholar]

- Eccles, Lance, and Samuel N. C. Lieu. 2023. Da Qin jingjiao liuxing Zhongguo bei 大秦景教流行中國碑 Stele on the Diffusion of Christianity (the Luminous Religion) from Da Qin (Rome) into China (the Middle Kingdom) ‘The Nestorian Monument.’ Ongoing Project (last update: 5.11.2023). Translated by L. Eccles and Sam Lieu, Camilla Derard and Gunner Mikkelsen. Available online: https://www.manichaeism.de/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/Xian-Monument-5.11.2023.pdf (accessed on 16 February 2025).

- Feng, Qiyong 馮其庸. 2007. ‘Da Qin Jingjiao xuanyuan zhi ben jing’ quan jing de xianshi ji qi ta 〈大秦景教宣元至本經〉全經的現世及其他. Zhongguo wenhua bao 中國文化報 [China Culture Daily]. Published September 27 in “Guoxue Zhuanlan” 國學專欄. Reprinted in 2007. Zhongguo zongjiao 中國宗教 [China Religion] 1: 28–31. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Youlan 馮友蘭. 1989. Zhongguo zhexue shi xin bian 中國哲學史新編 [A Revised History of Chinese Philosophy]. Beijing 北京: Renmin chubanshe 人民出版社, vol. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, Johan. 2014. Early Chinese Christianity: The Tang Christian Monument and Other Documents. Strathfeild: St. Pauls. [Google Scholar]

- Forte, Antonino. 1996a. A Literary Model for Adam: The Dhūta Monastery Inscription. In Paul Pelliot. Lʼinscription nestorienne de Si-ngan-fou. Edited by Antonino Forte. Paris: Scuola di Studi sullʼAsia Orientale, Kyoto-Collège de France, Institut des Hautes Études Chinoises, pp. 473–87. [Google Scholar]

- Forte, Antonino. 1996b. The Edict of 638 Allowing the Diffusion of Christianity in China. In Paul Pelliot. Lʼinscription nestorienne de Si-ngan-fou. Edited by Antonino Forte. Scuola di Studi sullʼAsia Orientale. Paris: Kyoto-Collège de France, Institut des Hautes Études Chinoises, pp. 349–73. [Google Scholar]

- Forte, Antonino. 1996c. The Chongfu-si 崇福寺 in Chang’an. In Paul Pelliot. Lʼinscription nestorienne de Si-ngan-fou. Edited by Antonino Forte. Paris: Scuola di Studi sullʼAsia Orientale, Kyoto-Collège de France, Institut des Hautes Études Chinoises, pp. 429–61. [Google Scholar]

- Foster, John. 1939. The Nestorian Tablet and Hymn. Translations of Chinese Texts from the First Period of the Church in China, 635–c. 900. London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge. [Google Scholar]

- Foster, John. 1954. Crosses from the Walls of Zaitun. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society 86: 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Chengyong 葛承雍. 2009. Jingjiao yizhen. Luoyang xin chutu Tangdai jingjiao jingchuang yanjiu 景教遺珍—洛陽新出土唐代景教經幢研究 [Precious Nestorian Relic. Studies on the Nestorian Stone Pillar of the Tang Dynasty Recently Discovered in Luoyang]. Beiiing 北京: Wenwu chubanshe 文物出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, Chengyong 葛承雍. 2014. Jingjiao tianshi yu Fojiao feitian bijiao bianshi yanjiu 景教天使與佛教飛天比較辨識研究 [A Comparative Study of the Nestorian Angels and Buddhist Apsaras]. Shijie zongjiao yanjiu 世界宗教研究 [Studies in World Religions] 4: 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Gilman, Ian, and Hans-Joachim Klimkeit. 1999. Christians in Asia before 1500. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press. [Google Scholar]

- Godwin, Tod. 2018. Persians at the Christian Court: The Xi’an Stele and the Early Medieval Church of the East. London and New York: I.B. Tauris. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, Tianmin [K’ung, Tien-min] 龔天民. 1958. Chūgoku keikyō ni okeru bukkyō teki eikyō nitsuite 中国景教に於ける佛教的影响につぃて [About Buddhist Influences in Tang Christianity]. Indogaku bukkyōgaku kenkyū 印度學佛教學研究 1: 138–39. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, Tianmin 龔天民. 1960a. Tangchao jidujiao zhi yanjiu 唐朝基督教之研究 [Research on Christianity during the Tang Dynasty]. Hong Kong: Council on Christian Literature for Overseas Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, Tianmin 龔天民. 1960b. Tangdai jidujiao zhong de fojiao yingxiang 唐代基督教中的佛教影響 [Buddhist Influences in Tang Christianity]. Zhonyang ribao 中央日報 [Central Daily News], March 8. [Google Scholar]

- Greene, Eric M. 2018. The “Religion of Images”? Buddhist Image Worship in the Early Medieval Chinese Imagination. Journal of American Oriental Society 138: 455–84. [Google Scholar]

- Grenfell, Bernard P., and Arthur S. Hunt. 1897. Sayings of Our Lord from an Early Greek Papyrus. London: Henry Frowde. [Google Scholar]

- Halbertsma, Tjalling H. F. 2008. Early Christian Remains of Inner Mongolia. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Hamada, Naoya 浜田直也. 2005. Keikyō kyōten ‘Isshinron’ to sono shisō 景教経典『一神論』とその思想 [The Jingjiao Sutra ‘One God’ and its Thought]. Intriguing Asia アジア遊学. Special issue, Tokushū kyōsei suru kami・hito・hotoke—Nihon to Furansu no gakujutsu kōryū 特集 共生する神・人・仏–日本とフランスの学術交流 [Symbiotic Gods, People, and Buddhas: Academic Exchange between Japan and France] 79: 244–57. [Google Scholar]

- Hamada, Naoya 濱田直也. 2007. Keikyō kyōten『Isshinron』to sono bukkyōteki seikaku ni tsuite 景教經典『一神論』とその佛教的性格について [On the Keikyō Sūtra “One God” and its Buddhist Character]. Studies in Literature, Japanese and Chinese 文芸論叢 68: 61–75. [Google Scholar]

- Haneda, Tōru 羽田亨. 1918. Keikyō kyōten Isshin-ron kaisetsu [景敎經典一神論解説]. Geibun [藝文/京都文學會] 9: 141–44. [Google Scholar]

- Haneda, Tōru 羽田亨. 1958. Haneda Hakushi shigaku ronbunshū 羽田博士史學論文集 [Collection of Papers on Historical Research of Dr. Haneda Hakushi]. Kyōto 京都: Tōyōshi Kenkyūkai 同朋社. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, Valerie. 2012. The Silk Road: A New History. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, Paul. 1987. Who Gets to Ride in the Great Vehicle? Self-Image and Identity Among the Followers of the Early Mahāyāna. Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies 10: 67–89. [Google Scholar]

- Hirakawa, Akira. 1997. A Buddhist Chinese-Sanskrit Dictionary. Tokyo: The Reiyukai. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Rong. 2023. The Humanity of Christ in the Jingjiao Dunhuang Manuscript Discourse on the One God. Silk Road Traces: Studies on Syriac Christianity in China and Central Asia 21: 375–93. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Xianian 黃夏年. 1996. Jingjiao yu fojiao guanxi zhi chutan 景教與佛教關係之初探 [Preliminary Investigation of the Relationship between Jingjiao and Buddhism]. Shijie zongjiao yanjiu 世界宗教研究 [Studies in World Religions] 1: 83–90. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Xianian 黃夏年. 2000. Jingjing ‘Yishen lun’ zhi ‘hunpo’ chutan 景經《一神論》之“魂魄”初探 [Preliminary Exploration of the Hunpo in the Jingjiao text the Yishen lun]. Jidu zongjiao yanjiu 基督宗教研究 [Study of Christianity], 446–60. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter, Erica C. D. 2009. The Persian Contribution to Christianity in China: Reflections in the Xian Fu Syriac Inscriptions. In Hidden Treasures and Intercultural Encounters: Studies on East Syriac Christianity in Central Asia and China. Edited by Dietmar W. Winkler and Li Tang. Berlin: Lit Verlag, pp. 71–86. [Google Scholar]

- Itō, Takatoshi. 1996. The Formation of Chinese Buddhism and “Matching the Meaning”(geyi 格義). Memoirs of the Research Department of the Toyo Bunko (The Oriental Library) 54: 65–91. [Google Scholar]

- Kaltenmark, Max. 1969. Jing yu ba jing 「景」與「八景」[On the Jing and the Eight Jing]. In Tōyō bunka ronshū 東洋文化論集. Tokyo 東京: Waseda daigaku shuppanbu 早稻田大學出版部, pp. 1147–54. [Google Scholar]

- Kantor, Hans-Rudolf. 2010. ‘Right Words Are Like the Reverse’—The Daoist Rhetoric and the Linguistic Strategy in Early Chinese Buddhism. Asian Philosophy 3: 283–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimkeit, Hans-Joachim. 1993. Christian Art on the Silk Road. In Künstlerischer Austausch/Artistic Exchange. Akten des XXVIII. Internationalen Kongresses für Kunstgeschichte Berlin, 15-20. Juli 1992. Edited by Thomas W. Gaehtgens. Berlin: Akademie Verlag, pp. 477–88. [Google Scholar]

- Klimkeit, Hans-Joachim. 2003. Manichaeism and Nestorian Christianity. In History of Civilizations of Central Asia. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, vol. IV, Part 2. [Google Scholar]

- Kotyk, Jeffrey. 2024. Sino-Iranian and Sino-Arabian Relations in Late Antiquity: China and the Parthians, Sasanians, and Arabs in the First Millennium. Crossroads: History of Interactions Across the Silk Routes. Leiden: Brill, vol. 8. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, Whalen. 1979. Limits and Failure of ko-i (Concept-Matching) Buddhism. History of Religions 18: 238–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Coq, Albert von. 1985. Buried Treasures of Chinese Turkestan: An Account of the Activities and Adventures of the Second and Third German Turfan Expeditions, 1st ed. Edited by Peter Hopkirk. Hong Kong and London: Routledge. First published 1928. [Google Scholar]

- Legge, James. 1888. The Nestorian monument of Hsî-an fû in Shen-hsî, China: Relating to the Diffusion of Christianity in China in the Seventh and Eighth Centuries with the Chinese Text of the Inscription, a Translation, and Notes, and a Lecture on the Monument, with a Sketch of Subsequent Christian Missions in China. London: Trübner & Company. [Google Scholar]

- Leslie, Donald Daniel. 1981–1983. Persian Temples In T’ang China. Monumenta Serica 35: 275–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Ling 李翎. 2023. Jietu: Shijue Fojiao de kaiduan 借圖——視覺佛教的開端 [Borrowing Pictures—the Beginnings of Visual Buddhism]. Meishu daguan 美術大觀 [Art Panorama] 9: 116–21. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Sicheng 梁思成. 2013. Fojiao de lishi 佛教的歷史 [History of Buddhism]. Beijing北京: Zhongguo qingnian chubanshe 中國青年出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Liebenthal, Walter. 1956. A Clarification (A translation of the Yü-i Lun). Sino-Indian Studies 2: 88–99. [Google Scholar]

- Lieu, Samuel N. C. 2013. The ‘Romanitas’ of the Xi’an Inscription. In From the Oxus River to the Chinese Shores: Studies on East Syriac Christianity in China and Central Asia. Edited by Li Tang 唐莉 and Dietmar W. Winkler. Vienna and Münster: LIT, pp. 123–44. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Wushu 林悟殊. 2000. Fugang Qiancang shi cang jingjiao Yishen lun zhenwei cunyi 富冈謙藏氏藏景教〈一神論〉真偽存疑 [Doubts Concerning the Authenticity of the Nestorian Discourse on One God from the Tomioka Collection]. Tang yanjiu 唐研究 [Journal of Tang Studies] 6: 67–86. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Wushu 林悟殊. 2021. Tangdai jingjijiao yanjiu (zengding ben) 唐代景教再研究 (增訂本) [New Reflections on Nestorianism of the Tang Dynasty (an enlarged revision)]. Shanghai 上海: Shangwu yinshuguan 商務印書館. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Wushu 林悟殊, and Xinjiang Rong 榮新江. 1992. Suowei Li shi jiucang jingjiao wenxian erzhong bianwei 所謂李氏舊藏敦煌景教文獻二種辨偽 [Doubts Concerning the Authenticity of Two Nestorian Christian Documents Unearthed at Dunhuang from the Li Collection]. Jiuzhou xuekan 九州學刊 [Chinese Culture Quarterly] 4: 19–34. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Wushu 林悟殊, and Xinjiang Rong 榮新江. 1996. Doubts Concerning the Authenticity of Two Nestorian Christian Documents Unearthed at Dunhuang from the Li Collection. China Archaeology and Art Digest I 1: 5–14, Abridged English version of Lin Wushu, Rong Xinjiang 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Litvinsky, Boris Anatolevič, Zhang Guang-Da, and R. Shabani Samghabadi. 1996. History of Civilizations of Central Asia. Volume III: The Crossroads of Civilizations: A.D. 250 to 750. Paris: UNESCO Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Qingzhu 劉慶柱. 2023. Zhonghua wenming rending biaozhun yu fazhan daolu de kaogu xue chanshi 中華文明認定標準與發展道路的考古學闡釋 [The Archaeological Interpretation of the Determining Criteria and Developmental Path of Chinese Civilization]. Zhongguo shehui xue 中國社會科學 [Social Sciences in China] 6: 82–99. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Zhenning 劉振寧. 2007a. ‘Geyi’: Tangdai jingjiao de chuanjiao fanglüe jian lun Jingjiao de ‘geyi’ taishi “格義”: 唐代景教的傳教方略—兼論景教“格義”態勢 [On the Strategy of Geyi by Nestorianism for Dissemination in the Tang Dynasty]. Guizhou daxue xuebao (Shehui kexue ban) 貴州大學學報 (社會科學版) [Journal of Guizhou University (Social Sciences Edition)] 5: 19–31. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Zhenning 劉振寧. 2007b. Shiyu “guaikui” zhongyu “guaikui”: Tangdai Jingjiao “geyi” guiji tanxi 始於「乖睽」終於「乖睽」—唐代景教「格義」軌跡探析 [Examining the trajectory of Jingjiao’s geyi in the Tang Dynasty]. Guiyang 貴陽: Guizhou University Press 貴州大學出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Zhenning 劉振寧. 2009. Tangdai jingjiao ‘geyi’ lun fafan: Jian lun ‘geyi’ zhi libi” 唐代景教“格義”論發凡—兼論“格義”之利弊 [On (Geyi) of Jingjiao in the Tang Dynasty——The gains and losses of Nestorianism]. Guizhou daxue xuebao (Shehui kexue ban) 貴州大學學報 (社會科學版) [Journal of Guizhou University (Social Sciences Edition)] 4: 132–39. [Google Scholar]

- Lou, Yulie 樓宇烈. 2002. Fojing tongsu xuanjiang gaoben: Du Dunhuang yishu Zhong ‘jiangjing wen’ zhaji 佛經通俗宣講稿本——讀敦煌遺書中“講經文”札記 [The Manuscripts of Popular Lectures on Buddhist Scriptures—Notes on the ‘Sūtra Lecture Texts’ in the Lost Dunhuang Manuscripts]. In Jiechuang 戒幢, Jiechuang Foxue 戒幢佛學 [Jiechuang Buddhist Studies]. Changsha 長沙: Yuelu shushe 岳麓書社, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Xianglin [Lo Hsiang-lin] 羅香林. 1966. Tang Yuan erdai zhi jingjiao 唐元二代之景教 [Nestorianism in the Tang and Yuan Dynasties]. Hong Kong 香港: Zhongguo xueshe 中國學社. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Zhao 羅炤. 2007. Luoyang xin chutu Da Qin jingjiao xuanyuan zhiben jing ji chuangji shichuang de jige wenti 洛陽新出土《大秦景教宣元至本經及幢記》石幢的幾個問題 [Some Points on the Newly-Discovered Christian Stone Pillar Located in Luoyang City]. Wenwu 文物 [Cultural Relics] 6: 30–48. [Google Scholar]

- Malek, Roman. 2002. Faces and Images of Jesus Christ in Chinese Context. Introduction. In The Chinese Face of Jesus Christ. Edited by Roman Malek. Monumenta Serica Monograph Series 50. Sankt Augustin: Institut Monumenta Serica and China-Zentrum. Nettetal: Steyler Verl., vol. I, pp. 19–55. [Google Scholar]

- Malek, Roman, and Peter Hofrichter. 2006. Jingjiao. The Church of the East in China and Central Asia. Sankt Augustin: Institut Monumenta Serica. [Google Scholar]

- Mair, Victor H. 2012. What is Geyi, After All? China Report 48: 29–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, Eīchi [Matsumoto Eiichi] 松本榮一. 1980. Wanggubu de Jingjiao xitong ji qi mushi 汪古部的景教系統及其墓石 [Nestorian System and the Tombtones of the Öngüt tribe]. Translated by Shixian Pan 潘世憲. In Menggushi yanjiu cankao ziliao 蒙古史參考研究資料 [References of Mongolian Historical Study]. Neimenggu daxue menggushi yanjiushi bian 內蒙古大學蒙古史研究室編 14: 46–47. [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto, Eīchi [Matsumoto Eiichi] 松本榮一. 1938. Keikyō Sonkyō no keishiki nitsuite 景教「尊經」の形式に就て [About the Form of the Nestorian Zun jing]. Tōhō gakuhō 東方學報 8: 21–32. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, James Harry, and Chen Cheng. 2020. A Select Bibliography of Chinese and Japanese Language Publications on Syriac Christianity: 2000–2019. Hugoye: Journal of Syriac Studies 23: 355–415. [Google Scholar]

- Moule, Arthur Christopher. 1930. Christians in China before the Year 1550. London, New York and Toronto: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, Reprinted in Ch’eng wen, Taipei: 1972; Gordon Press, New York: 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Mu, Hongyan 穆宏燕. 2019. Jingjiao ‘Shizi lianhua’ tu’an zai renshi 景教“十字蓮花”圖案再認識 [A Recognition of Cross-Lotus Pattern in Nestorianism]. Shijie zongjiao wenhua 世界宗教文化 [The World Religious Cultures] 6: 51–57. [Google Scholar]

- Nakata, Mie 中田美絵. 2011. Hasseiki kōhan ni okeru chūō Yūrashia no dōkō to Chōan Bukkyōkai: Tokusōki Daijō rishu ropparamitta kyō honyaku sankasha no bunseki yori 八世紀後半における中央ユーラシアの動向と長安仏教界——徳宗期『大乗理趣六波羅蜜多経』翻訳参加者の分析より [Trends in Central Eurasia in the Late Eighth Century and the Buddhist Community of Chang’an—an Analysis of the Participants in the Translation of the Mahāyāna-naya-ṣaṭ-pāramitā-sūtra during the Reign of Emperor Dezong]. Kansaidaigaku tōzai gakujutsu kenkyūjo kiyō 関西大学東西学術研究所紀要 44: 153–89. [Google Scholar]

- Nattier, Jan. 2008. A Guide to the Earliest Chinese Buddhist Translations Texts from the Eastern Han 東漢 and Three Kingdoms 三國 Periods. Tokyo: The International Research Institute for Advanced Buddhology. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolini-Zani, Matteo. 2006. Past and Current Research on Tang Jingjiao Documents. In Jingjiao: The Church of the East in China and Central Asia, 1st ed. Edited by Roman Malek. London: Routledge, pp. 23–44. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolini-Zani, Matteo. 2009. The Tang Christian Pillar from Luoyang and Its Jingjiao Inscription a Preliminary Study. Monumenta Serica 57: 99–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolini-Zani, Matteo. 2013. Luminous Ministers of the Da Qin Monastery. A study of the Christian clergy mentioned in the ‘Jingjiao’ pillar from Luoyang. In From the Oxus River to the Chinese Shores: Studies on East Syriac Christianity in China and Central Asia. Edited by Li Tang and Dietmar W. Winkler. Zürich and Berlin: LIT Verlag, pp. 141–60. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolini-Zani, Matteo. 2022. The Luminous Way to the East: Texts and History of the First Encounter of Christianity with China. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolini-Zani, Matteo. 2023. The Interpretation of Tang Christianity in the Late Ming China Mission. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Niu, Ruji 牛汝極. 2008. Shizi lianhua: Zhongguo yuandai xuliya wen jingjiao beiming wenxian yanjiu 十字蓮花: 中國元代敘利亞文景教碑銘文獻研究. [The Syriac Writing System of Turkic-Uighur in Nestorian Inscriptions and Documents Found in China during 13th–14th Centuries]. Shanghai 上海: Shanghai guji chubanshe 上海古籍出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Niu, Ruji 牛汝極. 2017. Xin faxian de shizi lianhua jingjiao tongjing tuxiang kao 新發現的十字蓮花景教銅鏡圖像考 [The Study on the Newly Discovered Nestorian Cross-Lotus Bronze Mirror]. Xiyu yanjiu 西域研究 [The Western Regions Studies] 2: 57–63. [Google Scholar]

- Orzech, Charles D. 1998. Politics and Transcendent Wisdom: The Scripture for Humane Kings in the Creation of Chinese Buddhism. University Park: Penn State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang, Xiao 歐陽霄. 2016. Reflective Judgment vs. Investigation of Things: A Comparative Study of Kant and Zhu Xi. Ph.D. thesis, University College Cork, National University of Ireland, Cork, Ireland. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer, Martin. 2001. The Jesus Sutras Rediscovering the Lost Scrolls of Taoist Christianity. New York: Ballantine Wellspring. [Google Scholar]

- Parry, Ken. 1996. Images in the church of the East: The evidence from Central Asia and China. Bulletin of the John Rylands Library 78: 143–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parry, Ken. 2003. Angels and Apsaras: Christian Tombstones from Quanzhou. The Journal of the Asian Arts Society of Australia XII 2: 5–7. [Google Scholar]

- Parry, Ken. 2006. The Art of the Church of the East in China. In Jingjiao: The Church of the East in China and Central Asia, 1st ed. Edited by R. Malek. London: Routledge, pp. 321–39. [Google Scholar]

- Parry, Ken. 2010. The Iconography of the Christian Tombstones from Zayton. Li, Jingrong Trans. Maritime History Studies 2: 113–25. [Google Scholar]

- Parry, Ken. 2016. Early Christianity in Central Asia and China. In Christianity in Asia: Sacred Art and Visual Splendour, Asian Civilizations Museum. Edited by Alan Chong. Singapore: Dominie Press, pp. 24–31. [Google Scholar]

- Pelliot, Paul. 1909. La mission Pelliot en Asie centrale (Annale de la Société de géographie commerciale Monument, 65. [section indochinoise], fasc. 4. Hanoi: Imprimerie d’Extrême-Orient, pp. 37–38. [Google Scholar]

- Pelliot, Paul. 1931. Une phrase obscure de l’inscription de Si-ngan-fou. T’oung Pao XXVIII: 369–78. [Google Scholar]

- Pelliot, Paul. 1996. L’inscription nestorienne de Si-ngan-fou. Oeuvres posthumes de Paul Pelliot. Edited by Supplements by Antonino Forte (Rome: Italian School of East Asian Studies Epigraphical Series 2). Kyoto: Scuola di Studi sull’Asia Orientale. Paris: Collège de France, Institut des Hautes Études Chinoises. [Google Scholar]

- Pulleyblank, Edwin G. 1991. Lexicon of Reconstructed Pronunciation in Early Middle Chinese, Late Middle Chinese, Early Mandarin. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pulleyblank, Edwin G. 1999. The Roman Empire as Known to Han China. Journal of the American Oriental Society 119: 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reischauer, Edwin O. 1955. Ennin’s Diary: The Record of a Pilgrimage to China in Search of the Law. New York: Roland Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, Guan 任冠, and Du Meng 杜夢. 2024. Tangchaodun Jingjiao siyuan shengtai he shengtang de kaoguxue yanjiu 唐朝墩景教寺院聖台和聖堂的考古學研究 [Archaeological Investigation of Bema and Sanctuaries in the Church of the East Temple at Tangchaodun]. Xiyu yanjiu 西域研究 [The Western Regions Studies] 3: 45–55. [Google Scholar]

- Riboud, Pénélope. 2001. Tang. In Handbook of Christianity in China, Volume One: 635–1800. Edited by Nicolas Standaert. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, pp. 1–43. [Google Scholar]

- Rong, Xinjiang 荣新江. 2013. Eighteen Lectures on Dunhuang. Translated by Imre Galambos. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Rong, Xinjiang 榮新江. 2014. Dunhuang jingjiao wenshu de zhen yu wei 敦煌景教文書的真與偽 [The Authenticity of Dunhuang Jingjiao Manuscripts]. In San yi jiao yanjiu: Lin Wushu xiansheng guxi jinian lunwen ji 三夷教研究——林悟殊先生古稀紀念論文集 [Research on Sanyi Religion: Collected Essays in Commemoration of Mr. Lin Wushu]. Edited by Xiaogui Zhang 張小貴. Lanzhou 蘭州: Lanzhou daxue chubanshe 蘭州大學出版社, pp. 280–89. [Google Scholar]

- Saeki, Peter Yoshirō 佐伯好郎. 1911. Keikyō hibun kenkyū 景教碑文研究 [Research on the Stele Inscription of the Luminous Teaching]. Tōkyō 東京: Jirō shoin 待漏書院. [Google Scholar]

- Saeki, Peter Yoshirō 佐伯好郎. 1916. The Nestorian Monument in China. London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, Reprinted in 1928. [Google Scholar]

- Saeki, Peter Yoshirō 佐伯好郎. 1935. Keikyō no kenkyū 景教の研究 [Research on the Luminous Teaching/Nestorianism]. Tōkyō 東京: Tōhō Bunka Gakuin Tōkyō kenkyūsho 東方文化學院東京硏究所. [Google Scholar]

- Saeki, Peter Yoshirō 佐伯好郎. 1936. Old Problems Concerning the Nestorian Monument in China Re-examined in the Light of Newly Discovered Facts. Journal of the North China Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 67: 81–99. [Google Scholar]