Abstract

One recurrent criticism of the Madhyamaka doctrine of emptiness (śūnyatā) is its equation with a potential axiological nihilism that undermines, inter alia, the telos of Buddhist practice. Here, I speculate that Madhyamaka non-foundationalism could be compatible with the naturalized teleology of C.S. Peirce. In brief, Peirce argues on pragmatic grounds that the ‘final cause’ of events does not refer to a predetermined finis ultimis or summum bonum with any ‘intrinsic nature’ (‘svabhāva’). Rather, a final cause is a general continuum of lawfulness (‘Third’/future) that mediates between indeterminate possibility (‘First’/present) and determinate actuality (‘Second’/past). Therefore, while a continuum of ‘purposiveness’ is a rational precondition for all temporal events, its futural significance means it can only ever be asymptotically realized; indeed, the constitutively general form of each ‘final’ cause is, practically speaking, fundamentally vague and open-ended to some degree. Finally, I show that the so-called strange attractors of dynamical systems theory provide an imperfect model for this naturalized ‘groundless teleology’.

1. Introduction

While there is no dearth of interpretations of the doctrine of ‘emptiness’ (śūnyāta), the notion that Madhyamaka promotes a form of ‘nihilism’ is prevalent amongst ancient commentators, early Buddhologists, and is even upheld by some modern scholars.1 This argument often takes the form of equating the doctrine of ‘emptiness’ with the null hypothesis that ‘nothing exists’ (nāstika). Aside from the fact that Nāgārjuna himself explicitly denies that emptiness means non-existence, certain nihilistic readings of Madhyamaka metaphysics have been rightly critiqued as philosophically shallow.2 Here, then, I will not focus on metaphysical nihilism, but rather on the more probable specter of ethical and/or axiological nihilism. This amounts to the claim, not that ‘nothing exists’ simpliciter, but rather that nothing has any real normative purpose, meaning, or value. In other words, there is no teleological foundation in reality, and hence any practical judgments to that effect are purely conventional, subjective, and/or contingent—and thus ultimately ‘unreal.’ Since the dharma itself is a set of practices for the sake of the ‘final cause’ of liberation (nirvāṇa), though, a universal doctrine of ‘emptiness’ arguably evacuates Buddhist practices themselves of any karmic efficacy—in this case, Madhyamaka is not only nihilistic, but also self-defeating.

Below I speculate that the pragmatic realism of C.S. Peirce and his triadic metaphysics of events offers a naturalized teleology that is, in principle, compatible with the doctrine of emptiness.3 I take my bearings from their common contention that the causal process cannot be rationally reconstructed through any calculus of binary relations between autonomously intelligible terms. Instead, the binary relata that characterize efficient causation are themselves abstractions derived from a primary ontology of interrelated temporal events. In this context, Peirce describes a teleological ‘middle path’ that avoids the abstract reification of final causes—i.e., as substantive, predetermined, ideal states of perfection—while also rendering the causal role of general ideas irreducible in the co-dependent origination of conventional events. Specifically, in this framework, a final cause is a general continuum of lawfulness that pertains to the open future, one whose particular actualization necessarily represents an asymptotic, transitive movement towards a constitutively vague, open-ended generality. Since the continuous nature of final causes forever evades complete resolution in any finite sequence of discrete events, their own epistemic determination arises and develops in co-dependent relation to the particular actions they asymptotically legislate. The true object of teleological judgment is therefore something like a Kantian regulative ideal of practical reason—viz., a transcendental real that recedes as it is approached. To further illustrate the nature of what I call ‘groundless teleology’ in contemporary philosophy of science, I draw upon the science of strange attractors in chaos theory, which metaphorically depicts the idea of a general continuum of lawful order that nevertheless asymptotically legislates the actual behavior of natural dynamical systems.

In the next section, I briefly review the nihilistic reading of Madhyamaka and contrast it with a pragmatic interpretation in which reality is not ultimately ‘nonexistent’ (whatever that means …), but rather one where the only ‘reality’ that can be meaningfully said to exist is conventional reality.4 The third section discusses Nāgārjuna’s view of causation and time in light of this reading, and suggests that the binary relata of efficient causation are epistemic abstractions of concrete, interrelated temporal events. In the fourth section, I shift to the pragmatism of Peirce and show that he adheres to a very similar model of causation in his own triadic ontology of events. The fifth section then details how the triadic causation of events supports a ‘developmental teleology’ that is potentially compatible with the non-foundationalism of Madhyamaka. Finally, the sixth section turns to Peirce’s discussion of attractors in natural systems, which serves as a segue to the topic of ‘strange attractors’ in contemporary chaos theory; I show that these continuous mathematical forms provide an approximate model for groundless teleology. I conclude with a brief reflection upon the ethical import of this conversation for Mahāyāna Buddhism more generally.

2. Madhyamaka: Existential Nihilism or Pragmatic Realism?

The central claim of Nāgārjuna and the Madhyamaka school is that to be co-dependently originated is to be ‘empty’ (śūnyā) of intrinsic nature (svabhāva). In the prior Abhidharma context, the intrinsic nature of a dharma broadly corresponded to whatever property makes a particular dharma what it is independently of other things—i.e., its self-characterization (svalakṣaṇa). So, for instance, earth (pṛthivī) atoms (paramāṇu) are self-characterized by ‘hardness’ and ‘resistance’ (khara or kāṭhinya), while perceptual cognition (vijñāna) is self-characterized by being a “specific representation of an object” (viṣayaprativijñapti) (Arnold 2005, p. 18). Such atomic psycho-physical constituents represented both the epistemic foundation for perceptual knowledge and the ultimate level of metaphysical description. The Madhyamaka subversion of Abhidharma theory thus consists in the resolute denial that any such self-standing, essential properties exist: To exist at all, that is, just is to be co-dependently originated, and this means things exist solely in a conditional, provisional, and relational context.

From its inception, the Madhyamaka tradition recognized that the doctrine of universal emptiness could be mistakenly construed as undermining the normative efficacy of Buddhist practice. Nāgārjuna addresses this concern explicitly in Chapter 24 of the MMK. In the opening verses, he adopts the voice of a hypothetical Buddhist opponent who lambasts the apparent axiological nihilism of the Madhyamaka doctrine:

The point is rather straightforward: Since everything is co-dependently originated—and thus all conventional ‘truth’ equally empty of intrinsic nature—then the Four Noble Truths are also ultimately ‘empty’ (qua nonexistent or merely conventional). If true, a dreaded nihilistic domino effect ensues that finally obliterates the distinction between virtuous action and its ignoble counterpart. When pushed to its logical terminus, spiritual practice does not have any karmic efficacy or soteriological promise, there can be no Buddhas, and the dharma is meaningless—quite the disaster for a Buddhist!If all this is empty—neither arising nor ceasing—it follows for you that the Four Noble Truths do not exist. Due to the non-existence of the Four Noble Truths, knowledge, abandonment, cultivation and realization would be impossible…[Hence] you deny the real existence of the fruits of karma and [the distinction between] good and bad actions, and all conventional practices.

In his retort, Nāgārjuna critiques the false equivalency of emptiness and non-existence: “Here we say that you do not understand emptiness: [i.e.,] the purpose of emptiness and the meaning of emptiness. Consequently, you are hindered.”6 Candrakīrti’s commentary on this verse concisely explains:

[The] meaning of the term ‘dependent origination’ is just the meaning of the term ‘emptiness’. However, the meaning of the term ‘emptiness’ is not the meaning of the term ‘non-existence.’ Having mistakenly superimposed the meaning of ‘emptiness’ on the meaning of the term ‘non-existence’ you criticize us. Therefore, you do not understand the meaning of the term ‘emptiness.’

Candrakīrti insists that while co-dependence = emptiness, emptiness/co-dependence ≠ non-existence; to be ‘empty’ of intrinsic nature is not to be nonexistent, but rather to exist solely in a conventional, interdependent, and relational manner. And this is presumably the only way anything can exist for Madhyamaka: For if to be conventional just is to be co-dependently originated, and to be co-dependently originated just is to be empty of intrinsic nature, then, by a simple principle of transitivity, to be conventional just is to be ultimately real/empty according to the only possible intelligible standard thereof—viz., a conventional one.

Indeed, Nāgārjuna’s rebuttal of nihilism culminates at this very point in MMK 24: 18–19, verses often considered the heart of the treatise and even the quintessential dictum of Madhyamaka in general: “That which is dependently originated is explained to be emptiness. That, being a dependent designation, is itself the middle way. There does not exist anything that does not arise dependently. Therefore, there does not exist anything that is not empty.”8 Nāgārjuna insists that ‘emptiness’ itself designates the middle path that avoids the extremes of eternalism and nihilism: One the one hand, since the referent ‘emptiness’ is itself just a dependent or conventional designation, it cannot really be considered more real than anything else. Hence, any reified notion of ‘emptiness’ does not capture the metaphysical significance of emptiness, because the co-dependent manner whereby this linguistic designation emerges cannot be distinguished from its purely conventional function. On the other hand, to say that ‘emptiness’ equates merely to non-existence would be to deny the interdependent origination of the designation itself—, which is not only practically or conventionally incoherent, but also contrary to the middle-path that Nāgārjuna purports to endorse.

Of course, the gordian knot of Madhyamaka involves stipulating what exactly the identification of ‘ultimate’ and ‘conventional’ truth entails for Buddhists—and even how, or whether, a claim of this sort makes any sense. For instance, taking their bearings primarily from Candrakīrti, some scholars characterize Madhyamaka not as any kind of nihilism, but rather—quite to the contrary—as a sort of phenomenal or pragmatic realism predicated on the inherent unintelligibility of any bedrock metaphysical level of description. Jay Garfield, Mark Siderits, and Dan Arnold, to one extent or another, endorse some version of this ‘semantic interpretation.’ These scholars characteristically argue that, since ‘emptiness is itself empty’, conventional truth is the only intelligible form of truth for Nāgārjuna.9 Here it is worth considering MMK verse 7: 34 and Garfield’s commentary thereupon: “Like a dream, like an illusion, like a city of Gandharvas—in this way arising, abiding, and ceasing have been explained.”10 Garfield emphatically claims that Nāgārjuna is not saying that conventional phenomena are simply nonexistent, or that they are even ‘hallucinations’:

Indeed, it is to say the opposite. [For] existence itself must be reconceived. What is said to be ‘like a dream, like an illusion’ is their existence in the mode in which they are ordinarily perceived/conceived—as inherently existent. Inherent existence simply is an incoherent notion. The only sense that ‘existence’ can be given is a conventional, relative sense. And in demonstrating that phenomena have exactly that kind of existence and that dependent arising has exactly that kind of existence, we recover the existence of phenomenal reality in the context of emptiness.(1995, p. 177)

From this perspective, Nāgārjuna could be read as a sort of pragmatic or phenomenal realist about the nature of truth and/or reality.11 After all, if we cannot even make sense of terms like ‘ultimate reality’ and ‘emptiness’ without reference to the kind of practical situatedness presupposed in their conventional designation as such, then it follows that worldly experience—i.e., characterized by practical agents with relative means and ends—is about as ‘real’ as anything could ever possibly get. Accordingly, Siderits’ dictum for Madhyamaka reads, ‘the ultimate truth is that there is no ultimate truth’—that is to say, that there is no final, foundational theory of reality outside of the practical realm upon which we can sensibly hang our metaphysical hats.12 For something to exist conventionally just is for something to appropriate its existence from innumerable causes and conditions—inter alia, its general designation and interpretation.

In short, the primary distinction between an existential nihilist and pragmatic-realist reading of Madhyamaka is that the former holds it to be ultimately or metaphysically true that ‘nothing exists’—including the Four Noble Truths—whereas the latter denies the very intelligibility of ultimate metaphysical descriptions full stop (cf. Garfield and Siderits: 661). And yet, as we have seen, it is precisely because everything is ‘empty’ that one might also transitively deem the ‘conventional’ and ‘ultimate’ practically coextensive: To be ‘conventionally’ real just is to be co-dependently originated, which, ipso facto, just is to be ‘empty’ of intrinsic nature, and hence to be ‘ultimately’ real. On these sorts of readings, the Madhyamaka stance amounts to a principled refusal to characterize co-dependent origination in terms of any relations between autonomously intelligible terms or existents—as though emptiness were itself some ‘internal property’ of ready-made things with an intrinsic nature. Instead, there is nothing ‘more real’ than our conventional discursive practices because the co-dependent manner in virtue of which they themselves exist does not itself differ from the way anything at all can be intelligibly said to exist. Turning to the question of the conventional reality of causation, then, we will find that a pragmatic reading of Madhyamaka opens the door to a realist conception of final causation when compared with the philosophy of Peirce.

3. Causal Relata and Time in Madhyamaka

To illustrate how Madhyamaka might accommodate a certain pragmatic-realist conception of final causation, we must take cues from Nāgārjuna’s account of causation in general. For while Nāgārjuna speaks about causality at length, as far as I know, he does not systematically differentiate what distinguishes teleological concepts (i.e., those with causal efficacy) from the other forms of conceptualization (kalpanā, vikalpa) that characterize conventional reality.13 I will take my bearings from Kant, then, who provides a working definition in the Third Critique: A ‘purpose’ denotes “the object of a concept, in so far as the concept is seen as the cause of the object”, while the general form of ‘purposiveness’ is “the causality of a concept with respect to its object” (Kant 2000, §10). In other words, intentional content is judged to have ‘purposiveness’ when its semantic or general content is also identified as being the constitutive cause of its respective object.14

At several points in the MMK, Nāgārjuna claims that causes and effects mutually depend upon each other: “There is no object whatsoever without any cause … and there is no cause without any effect.”15 This seems to indicate that there is no effect without cause in the very same manner that there is no cause without effect. However, with respect to teleological judgment, this would appear to amount to the counterintuitive claim that, not only does the present oak tree depend upon a past acorn, but the present acorn likewise depends upon the future ‘tree’. Since this flatly contradicts the temporal asymmetry of causation, some scholars attempt to make sense of Nāgārjuna here with reference to the distinction between notional and existential dependence.16 The former reflects a mere semantic category of conventional association, while the latter refers to some substantial causal relation. So, for example, a father depends upon his son to be called a ‘father’, but does not depend upon his son merely to exist. One might therefore suggest that the ‘mutual dependence’ of cause and effect involves two different sorts of dependence relations: the effect depending existentially on the cause (qua substantive entities), and the cause notionally on the effect (qua formal properties of entities).17

However, since Nāgārjuna does not make this distinction himself18, we might choose to uphold the stronger reading of symmetrical existential dependence through the triadic category of a ‘causal assemblage’ or ‘causal field’ (sāmagrī).19 For in addition to the binary categories of ‘cause’ and ‘effect’, Nāgārjuna accepts the existence of an implicit background of causal factors that we require to conventionally explain the occurrence of a particular effect.20 For example, when we ask “What is the cause of this fire?”, we do not only refer to the immediately prior spark, but also, implicitly, to the kindling, air pressure, level of moisture, fire atoms, etc. In other words, there is no basis upon which to pick out the members that comprise a certain causal field without also thereby identifying some correlative effect to be explained, and vice versa.

To this extent, Nāgārjuna does not mean that the binary phenomenon of causation is unreal, but rather that the determination of particular causal relata depends upon a constitutively general level of description. As Westerhoff explains, causal relata depend upon conventional discursive practices because

it is our cognitive act of cutting up the world of phenomena in the first place which creates the particular assembly of objects that constitutes a causal field, which then in turn gives rise to the notions of cause and effect. This entails that the causal field, cause and effect are empty of svabhāva … If the objects in our everyday world owe their existence to a partly habitual, partly deliberate process of cutting up the complex flow of phenomena into cognitively manageable bits, the causal relations linking them cannot exist independently of us, since their relata do not do so either.(2009, pp. 98–99)

The discrete binary notions of cause and effect therefore represent post hoc abstractions derived from a holistic causal process. Hence no binary relation of existential dependence can describe all the causal conditions that generate a given effect, for the very designation of the latter automatically implies this general field of unstated causal factors.

Now, the significance of the sāmagrī for a Madhyamaka theory of teleology comes into relief when we consider that the mode of conceptualization that characterizes the relevant causal relata corresponds to the temporal asymmetry of the causal relation: that is to say, since a causal relation must obtain between two asynchronous relata, and each relatum is presumed to be momentary (kṣaṇika), the past ‘cause’ cannot exist once the present ‘effect’ comes into being, and the future ‘effect’ does not exist when the present ‘cause’ obtains.21 As we have seen, the Mādhyamika does not thereby reject the reality of the causal process tout court22: instead, “the missing relatum is to be supplied either by memory (if the cause is in the past) or by anticipation (if the effect is in the future). In this case, causation can still obtain, although it could no longer connect two entities ‘out there’; rather, it will always include reference to a mental entity” (Westerhoff 2021, p. 86). In other words, it does not make sense to consider the total causal constituents of a temporal event independent of their conventional determination as such, because one of the relata must necessarily come under a general conceptual description in terms of either memory (in the case of past phenomena) or expectation (in the case of future phenomena). From a purely conventional or practical perspective, then, the respective existence or non-existence of each of the causal relata corresponds to a specific form of conceptualization, and these general forms would be included as constitutive elements of the extended sāmagrī.

In terms of our teleological discussion, the most pressing observation is that, in conventional terms, the determination of a present effect and its respective causal field—viz., an entire causal event—does not only depend upon the memory of a settled past, but also expectations (apekṣā) towards the indefinite future.23 Although Nāgārjuna does not bring this distinction into his verses on causation—where he sometimes seems to treat past and future conceptualizations in a symmetrical fashion—the later Madhyamaka commentator Prajñākaramati explicitly notes that

Arnold leverages these verses to stress that the conceptual individuation of temporal events in Madhyamaka necessarily refers to general expectations apropos their futural significance:even the restriction of cause and effect to a single causal continuum cannot be considered real, because [the restriction] is conceptual (kālpanika) insofar as the effect has not arisen; given the reference (apekṣā) to the state of future phenomena, the conventional designation of things like “effects” is not actually true.

[No] causal relata can be individuated except relative to the expectations of an observer who in the first instance takes there to be some event of causation, his or her taking of which determines (inter alia) the scale at which anything will count as ‘cause’ or ‘effect.’ To say that reference to an ‘effect’ necessarily ‘depends on the state of future phenomena’ is thus to say that it depends on some perspective from which a complete, temporally extended event of causation could be in view—that it depends on there being something that is in the first instance taken, or conceived, as such an event, any reference to which remains, to that extent, “notional”…What Prajñākaramati suggests is that causal relations obtain, by temporal definition, between events—and ‘events’ do not just individuate themselves.(2021a, p. 20)

Arnold’s relevant point is that the determination of the causes of a temporal event presupposes conceptions vis-à-vis the unrealized future. Hence, while a presentist (viz., temporally symmetrical) interpretation of Madhyamaka might insist that the past and future are ‘empty’ or ‘unreal’ in precisely the same way, the realist could counter that Nāgārjuna’s point is not to deny the asymmetrical order of past, present, and future, but rather to emphasize that the conventional experience of this asymmetry is itself due to the fact that all three times arise together in the intentional determination of particular causes and effects. The temporality of causation therefore undermines the abstract view of time as either a homogeneous container or a heterogeneous concatenation of distinct moments; instead, the ordered procession of the three ‘times’ coextends with the conceptual determination of reality itself.

Accordingly, in the shortest chapter of the MMK (19), Nāgārjuna deconstructs the independent existence of the three times while also upholding their intrinsically ordered succession.25 His arguments begin with the presumption that temporal relata are determinate sorts of entities or actualities: if the present and the future depended upon the past in this fashion, he insists, then the present and future would have to actually exist in the past, in the same way that for a mereological whole to depend upon its parts, both must synchronically exist.26 Alternatively, he points out that if the three times are wholly independent, then they could not be conventionally defined relative to one another; for the past, by definition, is that which precedes the present, and the future, by definition, is that which succeeds the present.27 On Garfield’s reading, this means that “we can only understand these temporal periods, and hence time itself, as a system of relations, not as things. The kind of dependence that obtains between past, present, and future is the interdependence of events that are past, present, or future in relation to us, not the dependence between the periods themselves” (Garfield 2023, p. 885).

The rhetorical upshot, I take it, is that past, present, and future should not be regarded as objective realities that stand in respective binary relations of strict dependence and independence (pace, say, the Sarvāstivādins), but rather correspond to a general domain of order that attends the conceptual determination of conventional events. Nāgārjuna does not deny the triadic structure of temporal events, that is, but rather only that the causal nature of this order can be represented as a binary calculus of autonomously intelligible existents. As we will see below, Peirce emphasizes that the necessary conceptualization of the future in the abstract determination of binary causal relata entails that general levels of teleological description are irreducible causal factors in his own ‘logic of events’.

4. Peirce on Facts vs. Events

To recapitulate what has been discussed so far: From the perspective of a certain pragmatic-realist reading of Madhyamaka, I have shown that Nāgārjuna could be said to endorse a ‘triadic’ model of temporal causation with recourse to the notion of the ‘causal field’ (sāmagrī): that is to say, the process of causation does not make sense in terms of mere dyadic relations between a discrete succession of particular entities, but must encompass a broader ‘causal field’ of innumerable factors—chief among them, the epistemic faculties of memory and expectation that determine one of the relata, i.e., cause or effect, respectively. As discussed, according to Prajñākaramati, the temporal structure of this ‘causal field’ therefore includes the causal efficacy of general ‘expectations’ (apekṣā) with respect to unrealized events in the future.28 Insofar as ‘final causes’ amount to general concepts related to future events whose ‘effects’ nevertheless correspond to some respective present object, Nāgārjuna and Prajñākaramati can be reasonably interpreted as saying that the ‘causal field’ of each event includes teleological notions among its manifold conditions. However, since neither Nāgārjuna nor Prajñākaramati explicitly address how the causal structure of general ideas pertaining to the unrealized future fundamentally differs from other forms of conceptualization (kalpanā) that presumably lack causal efficacy (i.e., memories of the determinate past), we are left completely in the dark vis-à-vis the casual mechanisms of teleological judgment in Madhyamaka—and, more specifically, its potential (in)compatibility with the doctrine of emptiness, which, prima facie, can be construed as treating the notional status of the past and future in wholly symmetrical terms.29

This is where the pragmatism of Peirce can help shed light on the situation. For while obviously not couched in the Madhyamaka rhetoric of ‘emptiness’, we find a remarkably similar account of both the epistemic determination of causal relata and the co-dependent nature of final causation in his writings—especially in his later work. I will show that the critical relevance of Peirce for Madhyamaka is his description of ‘final causes’ as futural continuums, which avoids the essential determination of general concepts characteristic of, say, memories of the settled past. In this comparative context, we might say that no final cause bears an ‘essential nature’ (‘svabhāva’) with a determinate ground or final state of resolution, but rather represents a general form that ‘co-arises’ with the stochastic activity of particular existents in a manner that a Mādhyamika could potentially endorse.30

The first step in our argument draws upon the idea that, according to Peirce, the autonomously intelligible appearance of binary causal relata derives from a continuous temporal event that does not, strictly speaking, have a determinate beginning or end (Peirce 1998, EP I: 314–15 [1892]).31 This position derives from Peirce’s idealistic metaphysics consisting of three categories: ‘Firstness’, ‘Secondness’, and ‘Thirdness’. Put simply, Firstness corresponds to the Kantian notion of ‘objective intuition’—the vague, chaotic, and conceptually indeterminate manifold feelings in the immediate present; in causal terms, it signifies the element of pure chance or spontaneity in nature. Secondness denotes the determinacy of the already-actualized past, and hence characterizes the discrete sequence of cause and effect, predicative judgment (‘thisness’), and nominal unities; it signifies the brute mechanical force of efficient causation. Finally, Thirdness represents the domain of mentation and continuity—viz., the active mediation of the other two categories through the transcendental application of a general law/habit/rule/convention to regulate the transformation of indeterminate feelings into determinate intentional content.32 And, as we will discuss below, since Thirds are triadic relations to the open future, they also denote Peircean final causes.

In his later writings on causation, Peirce describes cause and effect—or binary ‘causality’ as distinct from triadic ‘causation’ (cf., Hulswit 2001a; 2001b; 2002)—as ‘facts’ abstracted from the concrete continuity of ‘occurrences’ or ‘events’: “A Fact … is so much of the Real Universe as can be represented in a Proposition, and instead of being, like an Occurrence, a slice of the Universe, it is rather to be compared to a chemical principle extracted therefrom by the power of thought; and though it is or may be Real, yet, in its Real Existence it is inseparably combined with an infinite swarm of circumstances, which make no part of the Fact itself” (Peirce 1967, MS 647: 00010 [1910]). In other words, a ‘fact’ denotes a certain propositional representation of a concrete event, one which stands in constitutive relations to a total complex of implicit circumstances that necessarily outstrips this propositional representation (Peirce 1976, NEM IV: 252 [1904]).33 We can already begin to appreciate, then, how the epistemic winnowing of facts from the interrelated morass of the concrete event is redolent of the Buddhist notion of the unstated relations of the entire sāmāgri that implicitly attend the conceptual designation of a ‘cause’ and ‘effect’—viz., in the strict sense that an implicit relational complex of causal factors always exceeds the binary designation of particular causal relata.

More specifically, Peirce explains in his Cambridge Lectures that the conceptual form of binary causal relata does not correspond to the ‘objective history of the universe for a short time’ (pace Mill), but denotes some subset of facts abstracted from events that exhibit a triadic continuity of inferential relations: In syllogistic terms, the ‘effect’ represents the conclusion; the ‘cause’ represents the minor premise; and the major premise represents a law from which the conclusion follows given the truth of the premises:

So far as the conception of cause has any validity … the cause and its effect are two facts. Now, Mill seems to have thoughtlessly or nominalistically assumed that a fact is the very objective history of the universe for a short time, in its objective state of existence in itself. But that is not what a fact is. A fact is an abstracted element of that. A fact is so much of the reality as is represented in a single proposition. If a proposition is true, that which it represents is a fact. If according to a true law of nature as major premise it syllogistically follows from the truth of one proposition that another is true, then that abstracted part of the reality which the former proposition represents is the cause of the corresponding element of reality represented by the latter proposition. Thus, the fact that a body is moving over a rough surface is the cause of its coming to rest. It is absurd to say that its color is any part of the cause or of the effect. The color is a part of the reality; but it does not belong to those parts of the reality which constitute the two facts in question.(Peirce 1992, RLT: p. 198 [1898])

Peirce claims that facts never represent events in their full manifold particularity, but rather correspond to the conformation of causal relata to inquiry at certain conventional levels of description—i.e., one where the presumed truth of some general law implies that valid relations of continuity obtain between certain factual propositions. For instance, when we inquire into the ‘cause’ of a volcanic eruption, we really mean “What is the fact from which, according to the principles of physics, necessarily resulted the fact that the mountain suddenly burst?” (Peirce 1967, MS 478: 00155-56 [1903]). Hulswit indirectly brings attention to the pertinent comparison with Madhyamaka: “By thus insisting that the causal relata are facts, Peirce makes clear that the general context of his discussion of the causal relata is epistemological rather than ontological. For, since a fact is defined as the correlate of a true proposition, there are no facts in and by themselves, independent of propositions. The context of facts is inherently epistemological” (Hulswit 2001a, sec. II). In other words, just as the sāmagrī represents those causal features of the world that implicitly attend the conceptual determination of a certain effect, Peirce shows that binary causal relata are not autonomously intelligible referents, but discrete propositional abstractions whose inferential relations mirror the continuous structure of concrete events.

Accordingly, even though abstracted ‘facts’ do not fully capture the relational nature of concrete reality, Peirce postulates that some isomorphism obtains between the continuous flow of events and the inferential process of reasoning: “If there is any reality … then what that reality consists in is this: that there is in the being of things something which corresponds to the process of reasoning, that the world lives, and moves, and has its being, in [a] logic of events” (Peirce 1992, RLT 161, [1898]). Thus, to the extent that Peirce’s triadic ‘logic of events’ accurately generalizes the concrete process of reasoning itself, an event does not consist merely in secondary changes to permanent substances; nor is it decomposable into isolated atomic instants. Rather, the experience of individual existents presupposes forms of lawful action that synthesize particular moments into intelligible unities: “Individual existence … only belongs to a single event which happens when and where it does and has no other being. For though we speak, for example, of Philip of Macedon as an individual, yet ‘Philip drunk’ and Philip sober’ were different. The ‘existing’ thing is only individual in the sense of being a continuous law regulating and unifying events of a series of instants” (Peirce 1967, MS 478: pp. 47–48, 1903).

In sum, Peirce’s pragmatic conception of individual terms and entities—including the discrete relata of efficient causation—consists in the transcendental legislation of spontaneous action through the application of a general rule, habit, or convention. Like Madhyamaka, Peirce would therefore concur that there is no essential, self-standing metaphysical ‘substance’ over and above the rules and conventions that govern the processual flow of events. Indeed, ‘reality’ just is the ‘co-dependent origination’ of general law and particular action—or rather, the asymptotic and imperfect actualization of general forms of being. What Peirce arguably renders more precise than Nāgārjuna, though, is that expectations are constitutive of the conceptual determination of causal relata because the semantic content of all general concepts is constitutively future-directed. In the next section, I outline in more detail how this futural directedness of general laws translates to a naturalized conception of final causation that a Mādhyamika could plausibly endorse.

5. Peirce’s Pragmatic Account of Final Causation

Given his commitment to the significance of the future, Peirce is sometimes accused of an inordinate ‘futurism’34 (quite unlike Nāgārjuna, whose symmetrical arguments often lend themselves to a problematic ‘presentism’ [cf., e.g., Westerhoff 2017, p. 96]). Whether this charge is justified or not, the explanatory premium Peirce places on the future reflects his joint commitment to scholastic realism and pragmatic semantics—which, for him, entails that “the meaning of every proposition lies in the future” (Peirce 1931/1968, CP 5.411-37, [1905]). More specifically, Peirce does not regard intentional content as an ‘image’ of some fully determinate empirical object, but rather describes mental representations (viz., ‘signs’) in terms of what we characteristically do as finite embodied agents: deploy determinate terms (Seconds) to signify an indeterminate empirical object (Firsts) for the sake of some general end (Thirds).35 Thus, as Forster puts it, “every application of a concept to an object expresses a law or habit and there is nothing to the meaning of a concept other than what is implied by its application” (Forster 2011, p. 77). The pragmatic significance of a general concept is therefore not a determinate entity, but coextends with one’s expectations apropos the effects of the object, which take the form of an implied rule, law, or convention with the counterfactual form: ‘If act A were conducted under conditions C, result R would occur.’ Using Peirce’s own example, to be ‘hard’ just means to be ‘resistant to scratches from other substances under such and such circumstances.’ The same principle holds true for all general concepts.

According to Peirce, since general concepts equate to the ascription of an anticipatory principle to some indeterminate object, they must indicate a tacit awareness of a formal continuum; for no matter how many conditions we enumerate for C, the counterfactual form of the general principle ensures that no countable number of instances could satisfy the general form of the conditional. For this reason, Peirce states that “every general is a continuum vaguely defined” (Peirce 1976, NEM 3. 929), and that “true generality is … nothing but a rudimentary form of true continuity. Continuity is nothing but perfect generality of a law of relationship” (Peirce 1931/1968, CP 6.172). To cite Forster again: “Just as a true continuum is defined by a description that delimits a space of possible elements, so a general concept is defined by a characteristic that delimits a space of possible objects” (Forster 2011, p. 60). So, for example, the ascription of the category of ‘dog’ to an object implies reference to a continuum of possible breeds. But the further specification of a breed itself refers to a continuum of possible individuals, all with their own general characters. Insofar as I must necessarily designate individual dogs in terms of general concepts, though, I will never be able to pick out an instantaneous particular dog that excludes all reference to real generality. Put simply: a general concept should not itself be viewed as a determinate image instantiated in some finite actual entity or even countable set of entities, but a real formal continuum whose ascription to an object represents its anticipated practical effects relative to the future.

Now, with respect to the naturalization of final causation, Helmut Pape emphasizes the critical point: For Peirce, “laws of nature are final causes” (p. 589)—that is, laws of nature are general continuums of order that asymptotically realize themselves in concrete events through the regulation of the ‘brute force’ of actual entities. Indeed, Peirce insists that efficient causation would not even be possible without final causation, because mechanical laws already presuppose the continuity of certain general regulative principles.36 To this extent, nature is constitutively teleological. Yet since the continuous form of general laws can only actualize themselves relative to some finite existents with causal efficacy, final causes, while necessary for eventful manifestation, are nevertheless intrinsically impotent, indeterminate, and vague when considered in themselves37:

We must understand by final causation that mode of bringing facts about according to which a general description of result is made to come about, quite irrespective of any compulsion for it to come about in this or that particular way; although the means be adapted to the end. The general result may be brought about at one time in one way, and at another time in another way. Final causation does not determine in what particular way it is to be brought about, but only that the result shall have a certain general character.(Peirce 1998, EP 2:120)

So, for example, an animal might seek out food through any number of routes, but if it is hindered along some route, it will find another way. It follows that the animal is not passively led to food in virtue of the paths it takes, but rather takes those particular paths because they lead it to food (Short 1981, p. 370). Some ideal circumstance must therefore be considered the final cause of the whole process, even though its constitutively general form entails a boundlessness of instantiations or modes of realization in the actual world. All actual instantiations of a rule or law are therefore necessarily asymptotic in their capacity to realize the vagueness and indeterminacy of the general form that they follow.38

We can therefore consider final causes as essentially habits of nature that direct otherwise spontaneous action towards some general, ill-defined fate. Peirce affirms, accordingly, that a final cause “may be conceived to operate without having been the purpose of any mind: that supposed phenomena goes by the name of fate” (Peirce 1931/1968, CP 1.204). In this sense, gravity is a ‘final cause’ because “it certainly destines things ultimately to approach the center of the earth” (Peirce 1967, MS 682 [1913]; cf. Wang 2005, p. 613). The point I want to emphasize here is that the human conception of a discrete goal-oriented ‘purpose’—as some determinate propositional fact that definitively answers the question as to why a particular artifact exists—represents a peculiar reification of the natural capacity to adopt general laws for the sake of regulating particular interactions. As Peirce notes, “it is … a widespread error to think that a ‘final cause’ is necessarily a purpose. A purpose is merely that form of final cause which is most familiar to our experience” (Peirce 1931/1968, CP 1.211).

Although analogous to the futural orientation of natural ends, then, the human sense of a discrete and final ‘purpose’ does not capture the continuous essence of teleology, which entails “more than a mere purposive pursuit of a predetermined end; it is a developmental teleology” (Peirce 1998, EP I: 331).39 This is the crucial difference between Aristotle and Peirce that opens up an avenue for a comparison with Madhyamaka; that is, Peirce did not attribute the tendency of things to evolve towards general ends to some perfect singularity of divine Goodness with an ‘essential nature’. For Aristotle, God is pure and eternal actuality—the ‘unmoved mover’ who creates the universe of forms but does not Himself change. The ideal perfection of God is thus the ontological ground of final causation for all other finite beings, who naturally yearn to manifest this divine excellence. In this context, a general type is a ‘final cause’ when the Goodness that would characterize its actualization accords with God’s ideal perfection (cf. Short, pp. 369–71). However, Peirce’s naturalized conception of teleology—i.e., as a relational continuity of lawfulness—is inherently open-ended, having no predetermined form (that is, at least in practical terms).

I have been trying to make the case, then, that the core relevance of Peirce’s pragmatic conception of teleology for Madhyamaka is this fundamental ‘open-endedness’ (Wang 2005, p. 616)—or, what practically amounts to the same thing, its lack of a determinate ‘intrinsic nature’. For the concrete ingression of all general teloi co-dependently arises through causal regulation of the interplay between total indeterminacy (Firstness or pure chance) and absolute determinacy (Secondness or brute force). Peirce therefore argues that the kind of general lawfulness that governs nature need not involve any substantive or divine ‘mind’ that envisions a predetermined perfect end for all beings, but rather reflects the ideal reality of formal continuums that legislate the spontaneous activity of actual entities. Since these continuous laws are statistical in the case of natural dynamical systems, they can be thought to implicitly contain or enfold an infinite complexity of unpredictable behavior. As we will see below, in contemporary chaos theory, the asymptotic regulation of apparently random dynamical systems comes to signify a continuous mathematical object with a fractal dimension called a ‘strange attractor’. Like Peircean final causes, these strange attractors testify to the fact that even seemingly stochastic activity can still be legislated by an implicate continuum of general order.

6. Strange Attractors and Groundless Teleology

In this section I will explain how the idea of ‘strange attractors’ in chaos theory provides a compelling model for the groundless teleology that concerns the present discussion. The reader should note, however, that this section is somewhat technical and only tangential to grasping the gist of my argument as it pertains to Buddhism. If they wish to skip this section and proceed to the conclusion—which returns to the significance of the argument for Buddhist thought—they should feel free to do so. It is my contention, though, that a grasp of the concept of strange attractors will help render more precise how a naturalized teleology differs substantially from other forms of final causation—namely, those that reify ends in a manner we deem inimical to the philosophical projects of Madhyamaka and Peirce.

We have seen that, for Peirce, the lawfulness of final causation (Thirdness) and the brute force of efficient causation (Secondness) are not in explanatory tension with one another, but rather interdependent forms of causation in both organic and inorganic processes: “Final causality cannot be imagined without efficient causality; but no whit the less on that account are their modes of action polar contraries” (Peirce 1931/1968, CP 1.213). For a general law without ‘a living reaction’ to carry it out on each separate occasion is, according to his own preferred metaphor, as “impotent as a judge without a sheriff” (Peirce 1931/1968, CP 7.532). On the other hand, “efficient causation without final causation…is mere chaos; and chaos is not even so much as chaos, without final causation; it is blank nothing” (Peirce 1931/1968, CP 1.220). This is because Peirce held that efficient causation is itself the evolutionary result of the tendency of stochastic activities to adopt lawful patterns of behavior.40 Short writes in this regard that, for Peirce, the “conformity of particular efficient causes to laws of efficient causation is itself an example of final causation”, (1981, p. 377) and concludes that “a law is not real except in the conformity of reactions to it. Hence, the sheriff is not meant to stand for an intermediary, but only for those reactions that do conform to law and which, by their conformity, give that law reality” (ibid. p. 379).

In elucidating this point, Peirce discusses irreversible processes in nature, like the diffusion of gases and biological evolution, which do not result from the brute mechanical force of any particular individual, but rather imply the reality of statistical laws that govern vast numbers of causally efficacious interactions. In the case of gaseous diffusion, the initial conditions of the molecules do not matter—merely through a statistically significant number of random interactions, they naturally adopt a lawful trajectory towards a general final state of dynamic equilibrium:

Take, for example, the phenomenon of the diffusion of gases. Force has very little to do with it, the molecules not being appreciably under the influence of forces. The result is due to the statistics of the equal masses, the positions, and the motions of the molecules, and to a slight degree only upon force, and that only insofar as there is a force, almost regardless of its character, except that it becomes sensible only at small distances. These features of a gas, that it is composed of equal molecules distributed according to a statistical law, and with velocities also distributed according to a statistical law, is an intellectual character. Accordingly, the phenomenon of diffusion is a tendency toward an end; it works one way, and not the opposite way, and if hindered, within certain limits, it will, when freed, recommence in such way as it can. Not only is an end an intellectual idea, but every intellectual idea governing a phenomenon produces a tendency toward an end. It is very easy to see by a general survey of nature, that force is a subsidiary agency in nature.(Peirce 1967, MS L75.288–298)

Peirce notes that the random motions of the gas molecules tend towards a dynamic equilibrium even though no efficient causal force ‘makes’ each one do so; instead, the state of equilibrium corresponds to the state of maximum entropy that lawfully unfolds given certain formal parameters (i.e., being a closed system consisting of molecules with a roughly equal mass and momentum). In this case, the general character of dynamic equilibrium—like the alimentary terminus for the paths of the animal mentioned above—can be achieved through any number of particular states. Yet the general character of the statistical law, by definition, entails that its full scope cannot be definitively exhausted through any finite number of countable circumstances.

Although Peirce himself did not live to see the birth of computing and the attendant science of complex systems, the irreversible tendency of gases to diffuse towards the ‘final cause’ of dynamical equilibrium with maximum entropy exemplifies what contemporary mathematicians would call an attractor. In dynamical systems theory, an attractor is a set of points in ‘phase space’ toward which a dynamical system will tend to evolve over time. Phase space is not a real space, but an abstract n-dimensional space wherein each axis corresponds to one of the coordinates required to specify the state of a dynamical system. In these models, a single point in the space corresponds to an instantaneous state of the system and the entire space represents every possible state. Thus, for example, the phase space for a single gas molecule would typically have six dimensions: three for position (x, y, z) and three for momentum (velocity in x, y, and z directions). Hence the phase space for a system of one trillion gas molecules would be (1012)6—quite large indeed!

However, not all attractors are bounded regions in phase space that bottom-out in dynamical equilibrium, and thus invariably give rise to a pattern of predictable behavior. Indeed, the shape of some subset of attractors—in particular, the ‘strange attractors’ that hypothetically legislate the activity of nonlinear, open systems far-from-equilibrium (e.g., like an organism or the weather)—are infinitely complex fractals that give rise to fundamentally unpredictable behavior. These sorts of attractors, as I will explain below, better reflect Peirce’s ‘developmental’ form of teleology, because the behavior that these laws legislate can never be completely stipulated in advance qua some predetermined end. Though in principle still computationally determinate, in practical terms, the trajectory of systems that follow these attractors can never be fully anticipated through any finite sequence of iterations of the rules that legislate their trajectories—they are essentially unpredictable.

To explain this in very schematic terms: suppose we have a real-world dynamical system whose state at a certain time can be represented by the values of n variables x1, x2 … xn.41 These variables could represent, say, the angular position and velocity of a pendulum, or the velocity and temperature gradients in the convection of a fluid, or any number of other sundry physical phenomena. Then, given proper quantities for these state variables and a system of n dynamical equations that determine the relationships between their rates of change, we can represent the dynamical behavior of a physical system evolving over time in phase space as a discrete function of the xi.42 It is clear that different trajectories in phase space cannot intersect or overlap for deterministic systems, as this would contradict the uniqueness of the solutions of the equations for a given set of inputs.

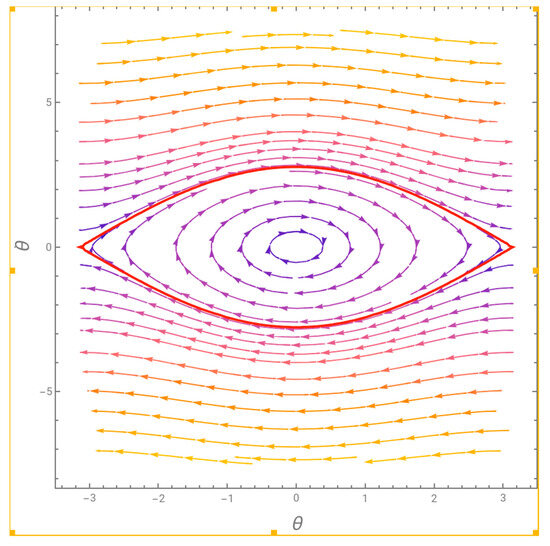

In the absolute simplest case of a deterministic system of equations with one variable x, we could represent the dynamical behavior of the system on the real number line R. In this case, there are only three possibilities for the evolution of the system: 1. Nothing happens because x always has the same value. 2. The value of x gets ever larger, and the trajectory tends towards infinity as t → ∞. 3. The trajectory is attracted to some point a, such that x(t) → a as t → ∞. Alternatively, in a very simple idealized system like a frictionless pendulum, it moves through a two-dimensional phase space that follows a predictable trajectory of perfectly cyclical motion (given that the initial conditions are constant), as in Figure 1 below:

Figure 1.

Bold red line represents the phase space trajectory for a simple pendulum.43.

The attractor of the swinging pendulum is therefore not only perfectly deterministic—in the sense that the linear relationship of the equations and the set of initial conditions will output a unique evolution of the system over some stretch of time—but also fully predictable. In other words, the Peircean ‘final cause’ of the movement of the pendulum—the rules that legislate its behavior over time—does not in principle leave room for unpredictable dynamical behavior with respect to the future evolution of the system. (Obviously, if friction is considered, the attractor would simply come to equilibrium, which is the single point in phase space where the values of its angular displacement from vertical position = 0 does not change).

Now, the notion of a ‘strange attractor’ applies to the case of ‘chaotic’ dynamical systems. Unlike pendulums, chaotic dynamical systems are characterized by nonlinear equations that exhibit a high degree of sensitive dependence on initial conditions. In common parlance, this designates the so-called ‘butterfly effect’, where the flap of a butterfly wing in China supposedly triggers a hurricane in Florida through some nonlinear feedback loops in the complex dynamical system of the atmosphere. Accordingly, the weather is a canonical example of a chaotic dynamical system, since very small changes in initial conditions end up having a profound impact on the future evolution of the system. The core insight of chaos theory is therefore that a deterministic, rule-bound system can nevertheless exhibit intrinsically unpredictable behavior, since to predict the system with perfect accuracy would require infinite specificity of the initial conditions, which is impossible. This is also the reason why the accuracy of weather forecasts will inevitably fail after a certain period, no matter how sophisticated and powerful the computer models.

Unlike the geometric attractors of a certain point (for the one-dimensional system) or circle (for the two-dimensional plane), the boundary of a strange attractor has an approximate fractal dimension between whole integers (e.g., ~2.4) that bears a global self-similar structure, but never exactly repeats on a local level. While a diffusion of gas, for example, will predictably tend towards that set of points in phase space that correspond to dynamical equilibrium, the trajectories of chaotic systems evolve towards attractors that never ‘bottom-out’ in any state of statistical equilibrium. Instead, the trajectories of the system will spiral or oscillate around an infinitely complex and dense attractor without ever settling down into a fixed point or a periodic cycle; in metaphorical terms, they are drawn into a ‘bottomless well’ that gives rise to fundamentally unpredictable behavior due to sensitive dependence on initial conditions.

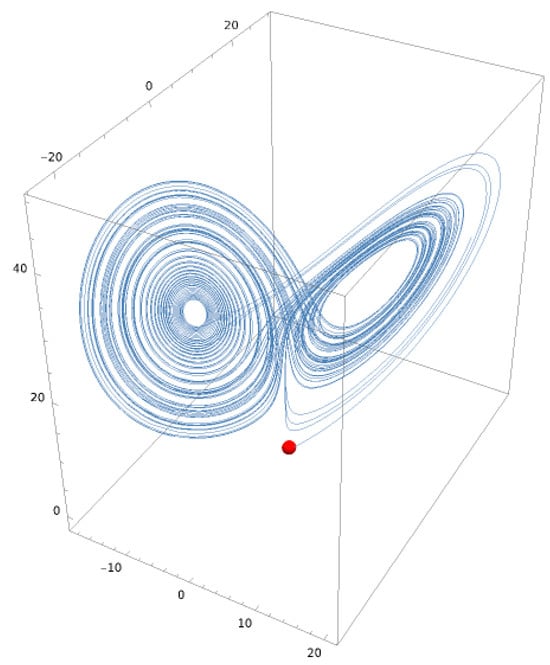

The most famous example is undoubtedly the Lorenz Attractor, named after Edward Lorenz, who discovered the attractor in 1963 while modeling the convection of the atmosphere, or when air is heated and cools in ascending and descending currents. He simplified the model into just three variables x, y, and z, along with three interlinked differential equations that specified the speed of convection flow, the horizontal temperature distribution, and the vertical temperature distribution. When he fed specific values for these equations into the computer and plotted the results in a three-dimensional phase space, Lorenz discovered that the trajectories of the system invariably settled into definite periodic cycles. These cycles oscillated between some positive values, reached a certain critical point, and then oscillated around some negative values, before switching back over to the other side. Lorenz discovered that there was no way to predict how many cycles a positive or negative trajectory would adopt before switching over to the other ‘wing’ of the attractor, and, furthermore, that two points arbitrarily close together on the attractor would quickly veer away from one another as the system evolved, as in Figure 2 below:

Figure 2.

One possible solution for the Lorenz Attractor.44.

Since the 1960s, many other geometrical attractors have been discovered, often more complex and striking than the butterfly wings of the Lorenz attractor.45 Indeed, given that natural systems often exhibit fractal structures and chaotic behavior, some scientists argue that strange attractors represent the formal laws governing the activity of organic systems as well.46 If strange attractors do indeed reflect the kind of lawful order that governs natural systems, they have important ramifications for our comparative discussion of non-foundationalist teleology. For the critical relevance of strange attractors is the manner whereby they reconcile a rule-bound domain of continuous order with the unpredictable behavior of discrete systems that are wholly deterministic. It should be emphasized that Peirce would never claim that the dynamical systems modeled on computers are natural systems, since they lack the irreducible element of chance/indeterminacy/spontaneity that metaphysical causation entails. In other words, I want to make it clear that I am not claiming that strange attractors are actual Peircean developmental teloi. Rather, I think they provide a compelling metaphor for the way that infinitely complex continuums of general order can nevertheless be thought to asymptotically govern (seemingly) random stochastic processes. What appears superficially chaotic or random, in other words, can follow general continuums of order whose natures always partly resist complete epistemic resolution.

In short, while such systems are wholly deterministic—and thus not, strictly speaking, triadic events in a Peircean sense—they nevertheless convey the idea of an infinitely complex continuum of lawful order towards which a finite system will asymptotically evolve. The strangeness of the attractor thus consists in its furnishing the dynamical system with a ‘futural’ source of order that also necessarily fails to bottom-out in any finis ultimis. The open-ended continuum of the strange attractor therefore does not provide any stable ‘ground’ of static equilibrium that would foreclose novel avenues of development—viz., a place where the full and final significance of the future gives itself over to total epistemic closure and predictability. Instead, the fractal dynamics of strange attractors asymptotically gesture towards an endless horizon of potential development for natural systems.

7. Conclusion: Buddhist Teleology and Ethics in a Groundless World

This paper proposed a speculative, constructive framework for reconciling the metaphysical non-foundationalism of Madhyamaka with the naturalized teleology of Peirce. Its purpose was primarily to offset charges of axiological nihilism that have confronted Madhyamaka since its inception through a version of teleology that avoids hypostatizing the nature of purpose—viz., as though ‘purpose’ itself possessed some ‘intrinsic nature.’ Instead, Peirce argues that the statistical laws that legislate the teleological structure of evolving natural systems do not imply any ‘final’ or ‘perfect’ state. Since they are definitionally general, and all general realities represent continuums of rule-bound order, there is an infinite number of ways in which a final cause can be potentially actualized, and no upper limit on the changing circumstances it can potentially regulate. Finally, to render the ideas in play more precise, I invoked the so-called ‘strange attractors’ of chaos theory, which provide a compelling contemporary analogue for this kind of open-ended, developmental teleology.

In sum, Peirce proposes a kind of naturalized teleology that a Mādhyamika could theoretically endorse: The general form of teloi themselves co-arise and develop in tandem with the irreducible spontaneity of the particular actions they legislate. Much like Kantian regulative principles of judgment, final causes are constitutively unrealizable sources of order in the ‘infinitely distant future’ that are nevertheless transcendentally real in the asymptotic legislation of present events. Or, as Höffe aptly puts it, the Kantian regulative principles designate ideal ends “toward which scientists always proceed but never completely reach. They are like a horizon that recedes at each forward step. One never arrives at its edge and never comes to a final stop” (Höffe 1994, p. 133). In the same way, then, a groundless telos recedes as it is asymptotically approached, forever unraveling into unforeseeable domains of novel order, yet always naturally tailored to the particular expectations and desires of finite practical agents.

I would like to end this essay with a note on the significance of this conversation for Mahāyāna Buddhist ethics and teleology more generally, which has perhaps been occluded in the preceding technical discussion. Arguably, the core of Buddhist ethics coincides with the doctrine of no-self (anātman), the Buddha’s teaching that our inner sense of an isolated, substantial, persistent identity is merely notional, and the primary source of clinging (tṛ́ṣṇā). Since clinging ultimately leads to unethical or ignoble karma that keep humans trapped in the eternal round of samsara, the false sense of self also represents the root of all suffering and dissatisfaction (duḥkha). The purpose of following the law of the dharma, then, is to awaken from this delusion and come to realize a mode of experience where the dualistic boundaries between ‘self’ and ‘other’ break down.

In the Madhyamaka tradition, the ‘emptiness’ of the dharma becomes embodied in the ideal figure of the Bodhisattva, whose cultivation of boundless wisdom and compassion instantiates the middle-path between nihilism (ucchedavāda) and eternalism (śāśvatavāda). Madhyamaka thus suggests that the ethical lawfulness of the dharma itself—which corresponds to the Bodhisattva’s unrealizable vow to attain boundless wisdom and compassion for the soteriological benefit of innumerable sentient beings—in fact coincides with the emptiness of the dharma: the true ‘emptiness’ of the dharma, in other words, is the ‘living spirit’ of Buddhahood as a never-ending process of spiritual cultivation, not a ‘dead letter’ that is eternally fixed with some self-standing ‘essential nature’ (svabhāva) of its own. The Bodhisattva is therefore one who ‘lays down a path while walking’—i.e., one who spontaneously responds in the appropriate manner to multitudinous ethical situations through the cultivation of the joint virtues of wisdom and compassion.47

Now, as we have seen, according to the pragmatism of Peirce, axiological, ethical, and teleological principles are akin to general scientific hypotheses that regulate, say, the statistical diffusion of gases, just insofar as they are similarly subject to continuous testing and refinement in light of experience and inquiry. As such, there is no final, determinate set of general laws whereby the objective structure of normative reality can be systematically hashed out. Yet, it is equally important to keep in mind that, although Peirce believed in the hypothetical open-ended evolution of ethical and teleological principles, the very nature of Thirdness-qua-continuity dictates a certain transcendental normative structure of thought itself; namely, in the human context, one based on the shared recognition that the delimited sense of mutually-exclusive personhood ultimately signifies a kind of stubbornly persistent illusion of Secondness. As Peirce himself writes apropos the ‘synechist’ (viz., one who adheres to a metaphysics of continuity):

Nor must any synechist say, ‘I am altogether myself, and not at all you.’ If you embrace synechism, you must abjure this metaphysics of wickedness. In the first place, your neighbors are, in a measure, yourself, and in far greater measure than, without deep studies in psychology, you would believe. Really, the selfhood you like to attribute to yourself is, for the most part, the vulgarest delusion of vanity.(Peirce 1998, EP II: 2 [1893])

It should be readily apparent to the reader that this sort of claim has a profound consonance with Buddhist ethical principles premised on the doctrine of anātman. More specifically, just because ethical and teleological principles are provisional and ever-evolving does not mean they do not exist—indeed, quite to the contrary: it is the very groundlessness (viz., continuity) of reality that imposes transcendental normative and teleological constraints on reason itself. This, I take it, would represent the Peircean way of expressing the Mahāyāna coextension of wisdom and compassion—the two proverbial ‘wings’ of the bodhicitta ‘bird’ that forever impels the Bodhisattva’s flight towards the salvation of innumerable sentient beings.

Accordingly, through the horizonal vision of groundless teleology, the canonical Bodhisattva vows are themselves transformed from apparently paradoxical statements—or perhaps even plain inconsistent propositions—into a coherent set of ‘strange attractors’: ‘Sentient beings are numberless; I vow to save them. Desires are inexhaustible; I vow to put an end to them. The Dharmas are boundless; I vow to master them. The Buddha Way is unattainable; I vow to attain it.’ Clearly, the unending and continuous directive of these constitutively futural teloi can never be definitively settled in any finite set of particular circumstances; and yet, they normatively regulate the present behavior of each Mahāyāna practitioner seeking to cultivate boundless wisdom and compassion for the sake of individual and collective liberation. We can therefore conclude that the boundless virtue and protean identity of the Bodhisattva figure—viz., one who spontaneously adopts bespoke forms and methods to suit the soteriological needs of individuals without themselves ever reaching the finis ultimus of Nirvāṇa—does indeed embody the living spirit of groundless teleology that I have attempted to articulate throughout this paper.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | For an overview of various classical Indian interpretations of Madhyamaka as nihilistic, see (Westerhoff 2016); for contemporary nihilistic readings, see, for example, (Wood 1994; Burton 2001; Tola and Dragonetti 1995; Oetke 1991, 1996). |

| 2 | Cf., e.g., (Westerhoff 2016; Siderits 2007). As Siderits (107) notes, there is a trivial Cartesian sense in which the thesis that ‘nothing exists’ is self-contradictory, for knowledge of the premise already disproves its purported assertoric content: after all, the very thought that ‘nothing exists’—even if it is sensible to say only ‘apparent’ as such—is still presumably something that exists (viz., the apparent nature of things). However, even more pressingly, the idea that ‘nothing exists’ sounds an awful lot like an assertion about the ultimate nature of reality as such—which a standard reading of Madhyamaka would doubtlessly disavow. For the central tenet of Madhyamaka is the idea that ‘emptiness’ does not mean that ‘nothing exists’ simpliciter, but rather only that nothing exists with intrinsic nature (svabhāva)—viz., nothing exists in a self-subsistent manner independently of everything else. Indeed, the whole spiel of Madhyamaka is its characteristic rhetorical withdrawal from any judgments about the ultimate nature of reality, opting instead for a ‘middle path’ between the binary extremes of strict existence or non-existence: e.g., astīti śāśvatagrāho nāstīty ucchedadarśanam/tasmād astitvanāstitve nāśrīyeta vicakṣaṇaḥ (MMK: 15.10); evaṃ hetuphalotpādaṃ paśyaṃstatkṣayam eva ca/nāstitāmastitāṃ caiva naiti lokasya tattvataḥ (RV 1.38; see Hahn 1982, p.5). |

| 3 | Although some comparative work has been done on Peirce and Buddhism—cf., e.g., (Lettner 2021; D’Amato 2003)—these are mostly focused on Peirce’s semiotics, which is indeed relevant to the current subject, but is ultimately beyond the scope of this paper. For a reading of Peirce that compliments my own interpretation here, see, in particular, the conclusion of Arnold’s (2021b) article. I should also note, though, that in this paper I am only interested in the general problem of final causation, and, specifically, whether any robust or modified ‘realist’ version thereof can make sense in the context of Madhyamaka’s anti-foundationalism. The other elements of Peirce’s philosophy and theology can be effectively bracketed, as I am only using his naturalized understanding of teleology to achieve clairty on this matter. |

| 4 | These sorts of constructive pragmatic readings of Madhyamaka, among other things, challenge Rortyan, anti-realist interpretations (e.g., Brons 2020). Such ‘deconstructionist’ pragmatic approaches tend to over-emphasize, I think, the anti-essentialism of Madhyamaka, such that they inadvertently reify the notion of anti-essentialism itself in a way that the Madhyamaka would balk at; for this overlooks its principal significance as a methodological commitment, not a positive predicative claim about the ‘ultimate nature of reality.’ Although Siderits does not invoke Peirce as a more compatible pragmatic realist, he notes that “Rorty’s form of antirealism is precisely the sort from which I have been at pains to distance Madhyamaka” (2015, p. 216, fn. e). See also Harris (2010) for a relevant argument to the effect that Madhyamaka avoids the ethical tensions of Rorty’s anti-foundational liberalism because the Buddhist, precisely through his recognition of the co-dependent origination of impermanence and suffering, is “motivated to adopt only identities that are committed to eliminating the suffering of self and others. Therefore, his compassion for others is not in tension with a commitment to private self-creation” (p. 71). Harris’ analysis thus directly bears on the way the Madhyamaka might offer a constructive teleology that attenuates the potential nihilism of anti-foundationalist epistemologies. |

| 5 | yadi śūnyam idaṃ sarvam udayo nāsti na vyayaḥ/caturṇām āryasatyānām abhāvas te prasajyate//parijñā ca prahāṇaṃ ca bhāvanā sākṣikarma ca/caturṇām āryasatyānām abhāvān nopapadyate…śūnyatāṃ phalasadbhāvam adharmaṃ dharmam eva ca/sarvasaṃvyavahārāṃś ca laukikān pratibādhase (MMK 24:1-2, 6; cf. Siderits and Katsura: p. 171). |

| 6 | atra brūmaḥ śūnyatāyāṃ na tvaṃ vetsi prayojanam/śūnyatāṃ śūnyatārthaṃ ca tata evaṃ vihanyase (MMK 24: 7). |

| 7 | evaṃ pratītyasamutpādaśabdasya yo ’rthaḥ sa eva śūnyatā śabdasyārthaḥ na punarabhāvaśabdasya yo’rthaḥ sa śūnyatāśabdasyārthaḥ/abhāvaśabdārthaṃ ca śūnyatārtha mityadhyāropya bhavānasmānupālabhate/tasmācchūnyatāśabdārthamapi na jānāti (La Vallée Poussin 1903–1913, sec. 491, pp. 15–17, cf. Westerhoff 2016, pp. 339–40). |

| 8 | yaḥ pratītyasamutpādaḥ śūnyatāṃ tāṃ pracakṣmahe/sā prajñaptir upādāya pratipat saiva madhyamā//apratītya samutpanno dharmaḥ kaścin na vidyate/yasmāt tasmād aśūnyo hi dharmaḥ kaścin na vidyate (MMK: 24.19). |

| 9 | See Ferraro (2013) for a criticism of this ‘semantic reading’, and Siderits and Garfield (2013) for a respective defense. |

| 10 | yathā māyā yathā svapno gandharvanagaraṃ yathā/tathotpādas tathā sthānaṃ tathā bhaṅga udāhṛtam (MMK 7: 34). |

| 11 | Huntington, for instance, draws attention to the affinity between James’ conception of truth and Madhyamaka: “His pragmatic definition is to a very great extent compatible with the Madhyamika’s analysis of truth as a function of what can be put into practice—what can be embodied in the thoughts, words, and actions that go to make up a form of life” (Huntington 1989, p. 44). Indeed, even though Huntington (2007) and Garfield (2008) disagree about the ultimate place of reason in Madhyamaka, they both concur that the kind of truth the Madhyamaka dialectic presupposes is constitutively practical. (I would even venture to suggest that the differences between the views of Huntington and Garfield apropos Madhyamaka are, respectively, analogous to the rift between James and Peirce over the ultimate place of reason itself in pragmatic philosophy). |

| 12 | Cf. Siderits (2007, p. 182) and Garfield (1995, p. 91, fn. 7; 2002, p. 99). Arnold similarly argues that Nāgārjuna’s identification of ultimate and conventional reality—and thus that even the proposition of everything as ‘empty’ must itself perforce be ‘empty’—amounts to the ‘theoretical’ prioritization of practical reason over the reifications of theoretical reason itself; for it makes no sense to theoretically distinguish ‘ultimately real’ causes from the conventional framework of existents whereby they are conceptually determined as such: “‘Emptiness’ … is not itself what there really is; rather, it characterizes what exists—specifically, as existing dependently, which is the only way that anything can—and is therefore only intelligible relative to existents … I want to suggest that we thus understand Madhyamaka arguments as meant to support a ‘theoretical’ claim whose very content is that theoretical reason cannot coherently be thought to trump practical reason—and that this may be useful in understanding what it means for Madhyamaka to propose an analysis (of existents as empty) that itself is ‘empty’” (Arnold 2008, p. 144). |

| 13 | I surmise this is likely due, inter alia, to the Abhidharma tradition he inherits that assumes a strict distinction between particulars and universals (e.g., there is nothing like Kantian ‘schemata’ in Buddhist philosophy). Of course, things are further complicated by the fact that artha in Sanskrit can mean goal/object/referent/aim., etc. The Sanskrit language therefore already suggests that, insofar as intentionality itself presupposes some practical standpoint, the mere existence of conceptual content implies that the distinction between ‘object’ and ‘objective’ is mostly a theoretical matter. |

| 14 | Famously for Kant, the attribution of causal efficacy to general ideas is afforded only in virtue of the aesthetic and teleological capacities of reflective judgment, which goes beyond a mere ‘determining’ form of judgment that subsumes empirical particulars under general forms of the understanding. Specifically, while the latter involves applying a general concept to a particular, the former involves moving from a particular to a general concept. Reflective judgment therefore involves the free play of the imagination and understanding to realize unknown universals. This is most evident in the experience of beauty, where reflective judgment bridges the gap between empirical ‘isness’ and normative ‘oughtness.’ |

| 15 | na cāsty arthaḥ kaścid āhetukaḥ kva cit … nāsty akāryaṃ ca kāraṇam (MMK: 4.2-3); also cf. pratītya kārakaḥ karma taṃ pratītya ca kārakam/karma pravartate nānyat paśyāmaḥ siddhikāraṇam; na cājanayamānasya hetutvam upapadyate/hetutvānupapattau ca phalaṃ kasya bhaviṣyati (MMK 8.12; 20.22). |

| 16 | In a pertinent series of essays, Hayes (1994), Taber (1998), Westerhoff (2009), and Arnold (2021a) debate about the apparent fallacies of equivocation (Hayes), or lack thereof (Taber, Arnold, Westerhoff) in Nāgārjuna’s argumentation in the MMK 1.3, which connects this conversation over causal dependence to the asymmetry of causation discussed further below. |

| 17 | This response would help defend Nāgārjuna against Hayes’s charge that the Buddhist authors do not distinguish between “saying that a thing exists at all and saying that it exists under a given description” (1994, p. 315). Westerhoff claims, accordingly, that “[t]he failure to distinguish between existential and notional dependence has resulted in considerable confusion in the contemporary commentarial literature, primarily in connection with the so-called principle of co-existing counterparts” (2008, pp. 28–29, fn. 40). Taber originally stated this principle with respect to a potential fallacy committed by Nāgārjuna, namely, “that a thing cannot be a certain type unless its counterpart exists simultaneously with it” (1998, p. 216). While such a definition accords perfectly well with, say, a notional form of dependence (‘North America’ mutually depends upon ‘South America’) in the case of existential dependence, this would entail a symmetry of cause and effect in “blatant contradiction of common sense” (ibid., 238). |