Shared Sounds: Using Borrowed Melodies to Create Shared Contexts in Late Medieval Saints’ Offices

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Jan Hus: A Saintly Sound

3. St Adalbert: A Common Sound

‘The Franciscan cardinal Matteo d’Aquasparta (d.1302) preached similarly when he suggested that the Virgin Mary, Mary Cleopas, and Mary Magdalen standing at the foot of the cross were themselves crucified by the compassionate agony they felt at the Crucifixion. Another Franciscan, François de Meyronnes, awarded Mary Magdalen the quadruple tiara. It will be remembered that one coronet—that of precious gemstones—was destined for martyrs. François argued that indeed Mary Magdalen herself was a martyr because she had been “impaled by the sword of the death of Christ.” Eudes de Châteauroux preached simply that the Magdalen was a martyr on account of her compassion.’28

4. St Demetrius: A Borrowed Sound

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Manuscript Sigla

| 1 | Issued with the support of the Czech Science Foundation as part of the project ‘The Use and Reception of Contrafact in Late Medieval Liturgical Chant’ (GN22-36033O) at the Masaryk Institute and Archives of the Czech Academy of Sciences. |

| 2 | For an examination of medieval Latin literacy with respect to song, see (Caldwell 2023). See also (Orme 1996; Barrau 2011). Many early reformers, including John Wycliffe, Jan Hus, Jacques Lefèvre d’Étaples, and Guillaume Briçonnet, argued for the translation of Latin church elements (such as the Gospel or chant) into the vernacular to aid lay comprehension. See, for example (Knapp 1971; Kim 2014; Reinburg 1992; Perett 2018). |

| 3 | The lack of comprehension within services and its effect on the performative aspects of the liturgy is examined in (Reinburg 1992). |

| 4 | Andrew Louth argues that sanctity is not found solely within the saints themselves, but also within the physical and spiritual surroundings of the Church (Louth 2011). |

| 5 | For examples within the Bohemian and Hungarian traditions see (Czagány 2021). |

| 6 | The Divine Office comprises daily services outside of Mass celebrations: for large feasts this often includes First Vespers, Compline, Matins, Lauds, the Little Hours (Prime, Terce, Sext, None), and Second Vespers. |

| 7 | Common chants–those from a Commune–are items from feasts that celebrate general categories (e.g., Common of a Virgin, Common of Martyrs, etc.), while Proper chants are those composed for a specific feast day (e.g., Easter, Jesus’ Nativity, St Ursula, etc.). The term properisation was coined by James McKinnon, see (McKinnon 1995). |

| 8 | Zsuzsa Czagány defines ‘Semi-Commune’ chants as those whose texts could be adapted for similar feasts through name replacement and minor textual changes (Czagány 2008, p. 154). |

| 9 | For an overview, see, for example, (Falck and Picker 2001). For an exploration of the term ‘contrafact’ and similar terminologies, see (Persico 2017; Burkholder 1994; Falck 1979). Meghan Quinlan discusses the introduction of the term ‘contrafact’ and contemporary literature in (Quinlan 2017, see especially ‘Historiographical Overview’, pp. 29–43). See also all chapters within (Pavanello 2020). For examples of contrafacta see, for example, (Bradley 2013; Derron 1999; Crosbie 1983; McIlvenna 2015; Wieczorek 2004; Chaillou-Amadieu and Rillon-Marne 2015; Deeming 2015; Hallas 2021; Bull 2022). |

| 10 | Kleinberg also discusses the changing conception of sanctity as martyr saints were joined by confessor saints, and the concern that nonsaints would be venerated in the same manner as the saints (Kleinberg 1989). |

| 11 | His followers, known as Hussites, later split into the Taborites (named after the Bohemian town of Tábor) and the Utraquists (named after the eponymous Latin phrase sub utraque specie–‘under both kinds’–which espoused the practice of celebrating the Eucharist with both bread and wine). For more information on the Hussites, see (Van Dussen and Soukup 2020). For discussions on the Hussite arguments for communion of both kinds see (Patapios 2002) and the importance of vernacular use see (Perett 2018). |

| 12 | For an examination of the Latin Office chants for Jan Hus, see (Hallas 2025; Holeton and Vlhová-Wörner 2015). For a catalogue of proper chants for Jan Hus, see (Fojtíková 1981); sources are listed on pp. 65–80 and chants on pp. 81–98. |

| 13 | In his sermon published in the Postil in 1413, Jan Hus gives only the names Martin, Jan, and Stašek: ‘a z těch Martin, Jan a Stašek byli sťati, a ve jménu Božím položení v Betlémě, a jiní potom jímáni, mučeni a žalařováni.’ (‘and of these Martin, Jan, and Stašek were beheaded, and in the name of God laid in Bethlehem [Chapel], and others were afterwards taken, tortured, and imprisoned.’) (Hus 1904, p. 60). Additional names are given by Václav Hájek z Libočan in his 1541 Kronyka Czeska: ‘nějaký Stanislav Polák, příjmím Stašek, tovaryš řemesla ševcovského … Druhý nějaký Martin, příjmím Křidélko … Třetí také nějaký Jan Hudec, příjmím Všetečka, rodem z Slaného…’ (‘a certain Stanislav Polák, surname Stašek, a journeyman of the shoemaker’s trade … The other one Martin, surname Křidélko … The third also some Jan Hudec, surname Všetečka, by birth from Slaný…’). Published by Jaroslav Kolár in (Hájek z Libočan 1981, p. 527). However, Hájek is often considered an unreliable author, and these bibliographic details cannot be confirmed. |

| 14 | For information on the use of this chant at the funeral, see (Fudge 2016, p. 151). |

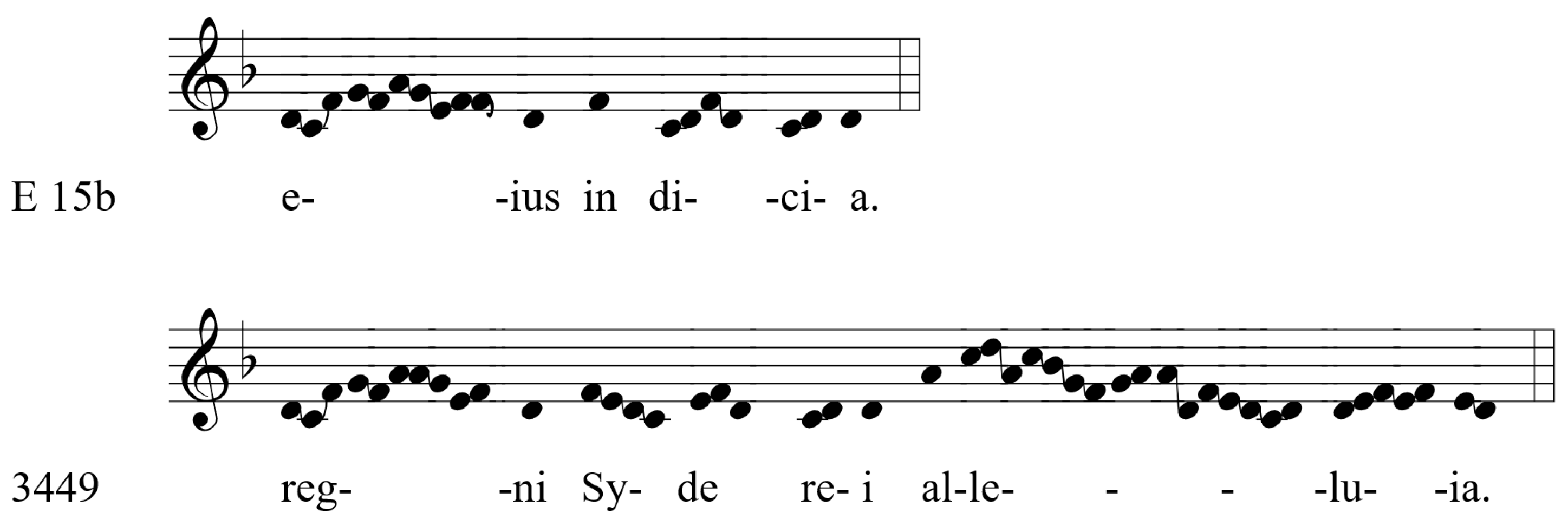

| 15 | Translation taken from (Hallas 2025, p. 73). “[A]lii pro Iohanne Huss et Ieronymo dampnatis hereticis publicis faciunt in ecclesiis coram multitudine populi exequias tamquam pro fidelibus defunctis, alii faciunt festivitates et cantant Gaudeamus et al.ia tamquam de martyribus, comparantes eosdem meritis et penis sancto Laurencio martyri…”. (Loserth 1895, pp. 386–87). |

| 16 | ‘Nonnulli scolarium rectores placere nescio cui cupientes, sed haud dubium diabolo per hoc servientes, etiamsi nescii, quorundam mundialium carminum melodias sumpserunt et illas super his, quae de potioribus sunt inter divinae laudis carmina, hoc est super hymnum angelicum Gloria in excelsis et super Symbolum Nicaenum ac super Sanctus et Agnus Dei, ut poterant, aptarunt haec sub eisdem mundialibus melodiis cantando dimissis devotis sanctorum patrum rnelodiis nobis praescriptis. Quae mundialium christifideles, ut sciens scio, scandalisent, sed etiam multos praesertim iuvenes vel carnales homines plus de domo choreae quam de regno caelorum cogitare faciunt in devotionis impedimentum non modicum, nimirum quia huiusmodi melodias vel eis similes in domo choreae saepe audierunt.’ (Gümpel 1956, p. 271). For a discussion of the use of secular materials within the Mass, see (Bloxam 2004, pp. 29–30). |

| 17 | H-Ek I.313 is digitised: https://bibliotheca.hu/scan/ms_i_313/index.html (accessed on 1 October 2025). For information on the manuscript, see (Körmendy et al. 2021, pp. 112–16). |

| 18 | Hana Vlhová-Wörner and David Holeton discovered images of the manuscript in František Michálek Bartoš’s collection in 2009 (Holeton and Vlhová-Wörner 2009). The manuscript itself was identified recently by Lucie Doležalová (Doležalová 2018). |

| 19 | The introduction of the Office for Hus is described in (Hallas 2025, p. 69). |

| 20 | For more information, see (Białuński 2002), specifically pp. 104–7. |

| 21 | See, for example, the thirteenth-century antiphoner D-Aam G 20, ff. 255v–257r. |

| 22 | For an overview of the different Offices for St Adalbert within the Bohemian, Polish, and Hungarian traditions, see (Czagány 2008, pp. 139–57; Pušova 2006). For information on the cult of St Adalbert in Central Europe, see (Kubín 2018). For the Prague Office for Adalbertus, including an edition, see (Pušová 2011). |

| 23 | For manuscripts in which the Office is found see (Kovács 2006) for the Esztergom tradition and (Kovács 2010) for the Transylvania-Varad tradition. |

| 24 | The music of the secular Matins often included the invitatory antiphon, a hymn, and three Nocturns each with three antiphons and three responsories. For some feasts and within monastic environments the number and order of chants could vary. For a detailed description of the Office services and their musical contents see (Harper 1991; Hiley 1993). |

| 25 | TR-Itks 42 also includes an Office for Adalbert’s translation, the Hungarian Ad festa pretiosi, on ff. 245v–247v. |

| 26 | See CZ-Pnm XV A 10, CZ-Pak P V1/2, and CZ-Pnm XII A 22. (Pušová 2011, pp. 95–115); the chant is transcribed on p. 108. |

| 27 | For more information on St Lambert’s Office see ‘Chapter Two: The Intersecting Cults of Saints Theodard and Lambert’ in (Saucier 2014). |

| 28 | For Matteo d’Aquasparta’s quote “Stabat unique paciens compaciens morienti commoriens crucifixo crucifixa” see I-Ac ms. 682, f.192v. The manuscript is digitised: https://www.internetculturale.it/jmms/iccuviewer/iccu.jsp?id=oai%3Awww.internetculturale.sbn.it%2FTeca%3A20%3ANT0000%3APG0213_ms.682&mode=all&teca=MagTeca+-+ICCU (accessed on 5 December 2025). For François de Meyronnes’ quote “Quia gladiata gladio mortis christi. Fuit etiam martyr propter amaricationem peccatorum quando in mente habuit.” (extended from the quote given by Jansen) see (Von Meyronnes 1493, f. 79r). The volume is digitised: https://www.digitale-sammlungen.de/en/view/bsb00036582?page=177 (accessed on 5 December 2025). For Eudes de Châteauroux’s sermon quote ‘Hec enim in litania in capite virginum ponitur quia fuit apostola, fuit et martyr compassione, fuit predicatrix ueritatis’ (not provided in Jansen) see (Bériou 1992, p. 336). |

| 29 | (Veselovská et al. 2024, p. 54). For more instances of this chant within Hungarian manuscripts, see (Hungarian Chant Database 2025). |

| 30 | For contrafact modification terminology, see (Johner 1953). |

| 31 | For an examination of the alleluia, see, for example, (Feeley 2024), especially ‘The link between Alleluia and Paschaltide’ on pp. 104–8, (Cabaniss 1964; Cochrane 1954; McKinnon 1996). |

| 32 | See, for example, the arguments for the evocation of pre-existing texts within a contrafacta in (Plumley 2003). |

| 33 | For an examination of his birth and importance to Hungary, see (Holler 2001). For a discussion of the Thessalonican/Sirmian origins of Demetrius, see (Tóth 2010). For the celebration of his cult in Hungary, see (Czagány and Tóth 2013, pp. ix–xxii). |

| 34 | Images of the crown are available online, at https://www.magyarkepek.hu/szelenyi/krone.html (accessed on 8 September 2025). |

| 35 | See the introduction to (Czagány and Tóth 2013). |

| 36 | See list on (Czagány and Tóth 2013, p. 25). |

| 37 | Manuscripts from the Szepes Chapter transmit the Esztergom (or Strigonium) rite. SK-Sk 2 is digitised: https://cantus.sk/source/6777 (accessed on 8 September 2025). A fragment of the late fifteenth-century notated Antiphonale Varadiense (H-Bn A 58) also contains sections of the Matins responsories Omnium quos celum and Inclite Dei martir. See the list of chants by fragment in (Czagány 2019, p. 53). |

| 38 | Voragine writes about this in his Legenda Aurea (de Voragine 2012, pp. 284–85). |

| 39 | In some Latin translations the incipit of Ecclesiasticus 31:8 is given as ‘Beatus dives qui inventus’, in others as ‘Beatus vir qui inventus’. |

| 40 | Following the foliation provided in the lower margin of the manuscript: according to the foliation in the upper right corner, ff. 225v–226r. PL-WRu Ms. R 503 is digitised: https://www.manuscriptorium.com/apps/index.php?direct=record&pid=ULW___-BUW___R_503_______2P0GEY6-pl (accessed on 26 September 2025). |

| 41 | The In circuitu tuo Domine text is used for a number of chants: the Commune plurimorum Martyrum antiphon; the verse of the responsory In isto loco primissio for the feast of the martyrs Pope Fabian and Sebastian (see, for example, F-Pn Latin 15181, ff. 419v–420r); the verse of the responsory O mirabile virginitatis for the feast of Gudula (in NL-Zua 6, f. 221r); and in two responsories found in multiple feasts–the most common with the verse Magnus Dominus et laudabilis, and the less common with the verse Lux perpetua lucebit. Both responsories are found in various Common Offices (Commune plurimorum Martyrum, Commune plurimorum Confessorum, Commune plurimorum Confessorum Pontificum, Commune plurimorum Confessorum non Pontificum), and where they are found in specific feasts within the Sanctorale, they are predominantly within those for martyrs and Prelates, matching their appearance within the Commune corpus. |

| 42 | A-Lib 290 is digitised: https://digi.landesbibliothek.at/viewer/image/290/1/ (accessed on 5 December 2025). |

| 43 | See Psalm 23:3 ‘Quis ascendet in montem Domini?’ and Psalm 83:6 ‘Beatus vir cuius est auxilium abs tee, ascensiones in corde suo disposuit’. |

| 44 | Andrew Louth discusses the way in which sanctity itself carries its history within it in (Louth 2011). |

References

Primary Sources

Secondary Sources

- Barrau, Julie. 2011. Did Medieval Monks Actually Speak Latin? In Monastic Practices of Oral Communication. Edited by Steven Vanderputten. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 293–317. [Google Scholar]

- Bériou, Nicole. 1992. La Madeleine dans les sermons parisiens du XIIIe siècle. Mélanges de l’Ecole française de Rome. Moyen Âge 104: 269–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Białuński, Grzegorz. 2002. O świętym Wojciechu raz jeszcze. Komunikaty Mazursko-Warmińskie 2: 95–127. [Google Scholar]

- Bloxam, M. Jennifer. 2004. A Cultural Context for the Chanson Mass. In Early Musical Borrowing. Edited by Honey Meconi. New York and London: Routledge, pp. 7–35. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley, Catherine A. 2013. Contrafacta and Transcribed Motets: Vernacular Influences on Latin Motets and Clausulae in the Florence Manuscript. Early Music History 32: 1–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bull, Andrew James Anderson. 2022. Analysis of Contrafacta Variation Found in the Inchcolm Fragments’ Office for St. Columba. Unpublished Ph.D. thesis, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, UK. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Burkholder, J. Peter. 1994. The Uses of Existing Music: Musical Borrowing as a Field. Notes 50: 851–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabaniss, Allen. 1964. Alleluia: A Word and Its Effect. Studies in English 5: 67–74. [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell, Mary Channen. 2023. Singing and Learning (in) Latin in Medieval Europe. Philomusica On-Line 22: 53–95. [Google Scholar]

- Chaillou-Amadieu, Christelle, and Anne-Zoé Rillon-Marne. 2015. Emprunter et Créer: Quelques Réflexions sur le Contrafactum. In Des Nains ou Des Géants? Emprunter et Créer au Moyen Âge. Edited by Claude Andrault-Schmitt, Edina Bozoky and Stephen Morrison. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 91–110. [Google Scholar]

- Cochrane, Marian Bennett. 1954. The Alleluia in Gregorian Chant. Journal of the American Musicological Society 7: 213–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosbie, John. 1983. Medieval “Contrafacta”: A Spanish Anomaly Reconsidered. The Modern Language Review 78: 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czagány, Zsuzsa. 2008. Adalbert-Offizien im mitteleuropäischen Raum. In Dies est leticie. Essays on Chant in Honour of Janka Szendrei. Ottawa: Institute of Mediaeval Music, pp. 139–57. [Google Scholar]

- Czagány, Zsuzsa. 2019. Antiphonale Varadinense s. XV: Vol. II Proprium de Sanctis et Commune Sanctorum. Budapest: Research Centre for the Humanities, Institute of Musicology. [Google Scholar]

- Czagány, Zsuzsa. 2021. Historiae in the Central European area: Repertorial layers and transmission in Bohemia and Hungary. In Historiae: Liturgical Chant for Offices of the Saints in the Middle Ages. Edited by David Hiley. Venice: Edizioni Fondazione Levi, pp. 273–95. [Google Scholar]

- Czagány, Zsuzsa, and Peter Tóth. 2013. Historia Sancti Demetrii Thessalonicensis. In Musicological Studies. Ottawa: Institute of Mediaeval Music, vol. LXV/20. [Google Scholar]

- Deeming, Helen. 2015. Multilingual Networks in Twelfth- and Thirteenth-Century Song. In Language in medieval Britain: Networks and Exchanges: Proceedings of the 2013 Harlaxton Symposium. Donington: Shaun Tyas, pp. 127–43. [Google Scholar]

- de Voragine, Jacobus. 2012. 69. Saint John before the Latin Gate. In The Golden Legend: Readings on the Saints. Translated by William Granger Ryan. Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. 284–85. [Google Scholar]

- Derron, Marianne. 1999. Von der Liebesnacht mit dem “burgfrowelin” zur Verehrung der Gottesmutter, Beispiel einer gründlichen Kontrafaktur. Jahrbuch für Volksliedforschung 44: 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doležalová, Lucie. 2018. The ‘Leipzig libellus’ in Zwickau. Studia Mediaevalia Bohemia 10: 255–57. [Google Scholar]

- Falck, Robert. 1979. Parody and Contrafactum: A Terminological Clarification. The Musical Quarterly 65: 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falck, Robert, and Martin Picker. 2001. Contrafactum. Grove Music Online. Available online: https://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/grovemusic/view/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.001.0001/omo-9781561592630-e-0000006361 (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Feeley, Giovanna. 2024. ‘From Praise to Practice:’ The Vocal and Musical Expression of the Alleluia as Gospel Acclamation in the Roman Rite Eucharistic Celebration: Provenance, Nature, and Function. Unpublished Ph.D. thesis, Dublin City University, Dublin, Ireland. [Google Scholar]

- Fojtíková, Jana. 1981. Hudební doklady Husova kultu z 15. a 16. století. Příspěvek ke studiu husitské tradice v době předbělohorské. Miscellanea Musicologica 29: 51–145. [Google Scholar]

- Fudge, Thomas A. 2016. Jerome of Prague and the Foundations of the Hussite Movement. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gümpel, Karl-Werner. 1956. Die Musiktraktate Conrads von Zabern. Akademie der Wissenschaften und der Literatur: Abhandlungen der Geistes- und sozialwissenschaftlichen Klasse 1–7: 260–80. [Google Scholar]

- Hallas, Rhianydd. 2021. Two Rhymed Offices Composed for the Feast of the Visitation of the Blessed Virgin Mary: Comparative Study and Critical Edition. Unpublished Ph.D. thesis, Bangor University and Charles University, Bangor and Prague. [Google Scholar]

- Hallas, Rhianydd. 2025. Between Tradition and Heresy: Fifteenth-Century Liturgical Chants for Jan Hus. In Music in Fifteenth-Century Bohemia: Between Reform and Identity Building. Edited by Hana Vlhová-Wörner and Jan Ciglbauer. Rochester: University of Rochester Press, pp. 51–81. [Google Scholar]

- Harper, John. 1991. The Forms and Orders of Western Liturgy from the Tenth to the Eighteenth Century: A Historical Introduction and Guide for Students and Musicians. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hájek z Libočan, Václav. 1981. Kronika Česká. Prague: Odeon. [Google Scholar]

- Hiley, David. 1993. Western Plainchant: A Handbook. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hiley, David. 2003. Music for saints’ historiae in the Middle Ages. Liturgical chant and the harmony of the universe. European Review 11: 475–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holeton, David, and Hana Vlhová-Wörner. 2009. A Remarkable Witness to the Feast of Saint Jan Hus. The Bohemian Reformation and Religious Practice 7: 156–84. [Google Scholar]

- Holeton, David, and Hana Vlhová-Wörner. 2015. The Second Life of Jan Hus: Liturgy, Commemoration, and Music. In A Companion to Jan Hus. Edited by František Šmahel and Ota Pavlíček. Leiden: Brill, pp. 289–324. [Google Scholar]

- Holler, László. 2001. Szent Demeter és a Magyar Király Korona. Magyar Egyháztörténeti Vázlatok Regnum 3–4: 5–17. [Google Scholar]

- Hungarian Chant Database. 2025. Available online: https://www.hun-chant.eu (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Hus, Jan. 1904. Sedmá neděle po Kristovu Narození. In Mistra Jana Husi Sebrané Spisy. Prague: Nákladem Jaroslava Bursíka, pp. 56–61. [Google Scholar]

- Jansen, Katherine Ludwig. 2001. The Making of the Magdalen: Preaching and Popular Devotion in the Later Middle Ages. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Johner, P. Dominicus. 1953. XIII. Kapitel: Veranderungen der melodischen formeln infolge kurzeren oder langeren textes. In Wort und Ton im Choral: Ein Beitrag zur Aesthetik des Gregorianischen Gesanges. Leipzig: Veb Breitkopf & Härtel Musikverlag, pp. 150–65. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Margaret. 2014. Lollardy and Political Community: Vernacular Literacy, Popular Preaching, and the Transformative Influence of Lay Power. Wenshan Review of Literature and Culture 7: 279–311. [Google Scholar]

- Kleinberg, Aviad M. 1989. Proving Sanctity: Problems and Solutions in the Later Middle Ages. Viator 20: 183–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knapp, Peggy Ann. 1971. John Wyclif as Bible Translator: The Texts for the English Sermons. Speculum 46: 713–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovács, Andrea. 2006. Corpus Antiphonalium Officii–Ecclesiarum Centralis Europae V/B Esztergom/Strigonium (Sanctorale). Budapest: Hungarian Academy of Sciences. [Google Scholar]

- Kovács, Andrea. 2010. Corpus Antiphonalium Officii–Ecclesiarum Centralis Europae VII/B Transylvania-Várad (Sanctorale). Budapest: Hungarian Academy of Sciences–Liszt Ferenc Academy of Music. [Google Scholar]

- Körmendy, Kinga, Judit Lauf, Edit Madas, and Gábor Sarbak. 2021. Az Esztergomi Főszékesegyházi Könyvtár, az Érseki Simor Könyvtár és a Városi Könyvtár kódexei (Codices of the Esztergom Cathedral Library, the Archbishop Simor Library, and the City Library). In Fragmenta et codices in bibliothecis Hungariae VII-A. Esztergom-Budapest: Esztergomi Főszékesegyházi Könyvtár, Akadémiai Kiadó, Országos Széchényi Könyvtár. [Google Scholar]

- Kubín, Petr. 2018. Le Culte Médiéval de Saint Venceslas et de Saint Adalbert en Europe Centrale. Prace Historyczne 3: 397–427. [Google Scholar]

- Loserth, Johann. 1895. Beiträge zur Geschichte der Husitischen Bewegung. V. Gleichzeitige Berichte und Actenstücke zur Ausbreitung des Wiclifismus in Böhmen und Mähren von 1410 bis 1419. Archiv für Österreichische Geschichte 82: 327–418. [Google Scholar]

- Louth, Andrew. 2011. Holiness and Sanctity in the Early Church. Studies in Church History 47: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIlvenna, Una. 2015. The Power of Music: The Significance of Contrafactum in Execution Ballads. Past & Present 229: 47–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- McKinnon, James W. 1995. Properization: The Roman Mass. In International Musicological Society Study Group Cantus Planus, Papers Read at the 6th Meeting, Eger, Hungary 1993. Edited by László Dobszay. 2 vols. Budapest: International Musicological Society, vol. I, pp. 15–22. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- McKinnon, James W. 1996. Preface to the Study of the Alleluia. Early Music History 15: 213–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moravcsik, Gyula. 1947. The Role of the Byzantine Church in Medieval Hungary. The American Slavic and East European Review 6: 134–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orme, Nicholas. 1996. Lay Literacy in England, 1100–1300. In England and Germany in the High Middle Ages. Edited by Alfred Haverkamp and Hanna Vollrath. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 35–56. [Google Scholar]

- Patapios, Hieromonk. 2002. Sub Utraque Specie: The Arguments of John Hus and Jacoubek of Stříbro in Defence of Giving Communion to the Laity under Both Kinds. The Journal of Theological Studies 53: 503–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavanello, Agnese, ed. 2020. Kontrafakturen im Kontext. Basel: Schwabe Verlagsgruppe AG Schwabe Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Perett, Marcela K. 2018. Preachers, Partisans, and Rebellious Religion: Vernacular Writing and the Hussite Movement. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Persico, Thomas. 2017. “Contrefact”, “contrafact”, “contrafactum” (secoli xiv-xv): Falsificazione, imitazione, parodia. Elephant and Castle Laboratorio Dell’immaginario 17: 5–29. [Google Scholar]

- Plumley, Yolanda. 2003. Intertextuality in the Fourteenth-Century Chanson. Music & Letters 84: 355–77. [Google Scholar]

- Pušova, Renata. 2006. Officium svatého Vojtěcha v Českých Pramenech. Unpublished Master’s thesis, Charles University, Prague. [Google Scholar]

- Pušová, Renata. 2011. Das Prager Offizium des heiligen Adalbertus. Hudební Věda 48: 95–115. [Google Scholar]

- Quinlan, Meghan. 2017. Contextualising the Contrafacta of Trouvère Song. Unpublished Ph.D. thesis, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Reinburg, Virginia. 1992. Liturgy and the Laity in Late Medieval and Reformation France. The Sixteenth Century Journal 23: 526–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saucier, Catherine. 2014. A Paradise of Priests: Singing the Civic and Episcopal Hagiography of Medieval Liège. Rochester: University of Rochester Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tóth, Peter. 2010. Sirmian Martyrs in Exile: Pannonian Case-Studies and a Re-Evaluation of the St. Demetrius Problem. Byzantinische Zeitschrift 103: 145–70. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dussen, Michael, and Pavel Soukup, eds. 2020. A Companion to the Hussites. Leiden: Koninklijke Brill NV. [Google Scholar]

- Veselovská, Eva, Eduard Lazorík, and Hana Studeničová. 2024. Catalogus Fragmentorum Cum Notis Musicis Medii Aevi e Civitate Cremniciensi. Bratislava: Institute of Musicology of the Slovak Academy of Sciences. [Google Scholar]

- Von Meyronnes, Franciscus. 1493. Sermones de Sanctis. Venice: Peregrinus de Pasqualibus. [Google Scholar]

- Wieczorek, Ryszard J. 2004. Facts about Contrafacta. Netherlandish-Italian Music in Saxo-Silesian Sources from the Late Fifteenth Century. Musicology Today 1: 16–37. [Google Scholar]

| Position | Chant Incipit | Type |

|---|---|---|

| VA | O immarcescibilis rosa | Proper |

| VR | Exora dilecte Dei v/ Dissimiles tibi moribus | Proper Contrafact |

| VH | Vita sanctorum * | Common |

| VAM | Magna vox laude | Semi-Common |

| MI | Alleluia regem martyrum | Common |

| MA1.1 | Tristitia vestra alleluia | Common |

| MR1.1 | Beatus vir qui v/ Potens in terra erit | Common |

| MR1.2 | Filiae Jerusalem venite v/ Quoniam confortavit seras | Common |

| MR1.3 | Miles Christi gloriose v/Ut caelestis regni | Semi-Common |

| LA1 | Sancti tui Domine | Common |

| LA2 | Sancti et justi | Common |

| LA3 | In velamento clamabunt | Common |

| LA4 | Spiritus et animae | Common |

| LA5 | In caelestibus regnis | Common |

| LH | Tu tuo laetos * | Common |

| LAB | Vox laetitiae in tabernaculis | Common |

| V2A | Sancti tui Domine * | Common |

| V2R | Christi martyr Adalbertus v/ Mortem autem quam | Common |

| V2H | Vita sanctorum Deus * | Common |

| V2AM | Gloria Christo Domino | Proper |

| St Lambert | St Adalbert |

|---|---|

| Magna vox laude sonora te decet per omnia quo poli chorea gaudet aucta tali compare terra plaudit et resultat digna tanto presule o sacer Lamberte martyr nostra vota suscipe. | Magna vox laude sonora te decet per omnia quo poli corea gaudet aucta tali compare terra plaudit et exultet digna tanto presule o sacer Adalberte martir nostra vota suscipe, alleluia. |

| Position | Chant Incipit | Type | Melody Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| VH | Deus tuorum militum | Common | |

| VAM | A progenie in progenies | Common | |

| MI | Pretiosi martyris Demetrii | Contrafact | Prestolantes redemptorem |

| MA2.1 | Ultimi doloris dominice | Contrafact | Nature genitor conserva |

| MR2.1 | Nestor iam renatus v/Per nomen sancti Demetrii | Contrafact | Audi Israel precepta v/Observa igitur et audi |

| MR2.3 | Beatus vir Demetrius * v/Qui potuit transgredi * | Semi-Common | |

| MA3.1 | Omnium quos celum | Contrafact | In circuitu tuo Domine |

| MR3.3 | Christi martyr gloriose v/Ut celestis regni | Common | |

| LH | Martir Dei qui | Common |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hallas, R. Shared Sounds: Using Borrowed Melodies to Create Shared Contexts in Late Medieval Saints’ Offices. Religions 2025, 16, 1585. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16121585

Hallas R. Shared Sounds: Using Borrowed Melodies to Create Shared Contexts in Late Medieval Saints’ Offices. Religions. 2025; 16(12):1585. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16121585

Chicago/Turabian StyleHallas, Rhianydd. 2025. "Shared Sounds: Using Borrowed Melodies to Create Shared Contexts in Late Medieval Saints’ Offices" Religions 16, no. 12: 1585. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16121585

APA StyleHallas, R. (2025). Shared Sounds: Using Borrowed Melodies to Create Shared Contexts in Late Medieval Saints’ Offices. Religions, 16(12), 1585. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16121585