National Identity, Religion, and Religiosity in Central and Eastern Europe: Types, Patterns, and Correlations

Abstract

1. Introduction: National Identity and Religion in the West and East

2. National Identity in Quantitative Social Research

3. The Connection Between National Identity, Religion, and Religiosity

4. Objectives, Research Questions, and Hypotheses

- Can we identify a clear common typology of national identity in Central and Eastern Europe based on categories of nationalism, patriotism, ethnic and civic concepts of national belonging?

- 2.

- To what extent are the types identified represented in the countries of the region? What differences can be observed between the countries?

- 3.

- How does a religious and denominational concept of national belonging relate to the types of national identity identified?

- 4.

- What is the relationship between the types of national identity and different forms of religiosity and spirituality?

5. Data and Methods

5.1. Data

5.2. Measures

5.2.1. National Identity

5.2.2. Religion, Religiosity, and Spirituality

5.3. Data Analysis

6. Results

6.1. A Typology of National Identity

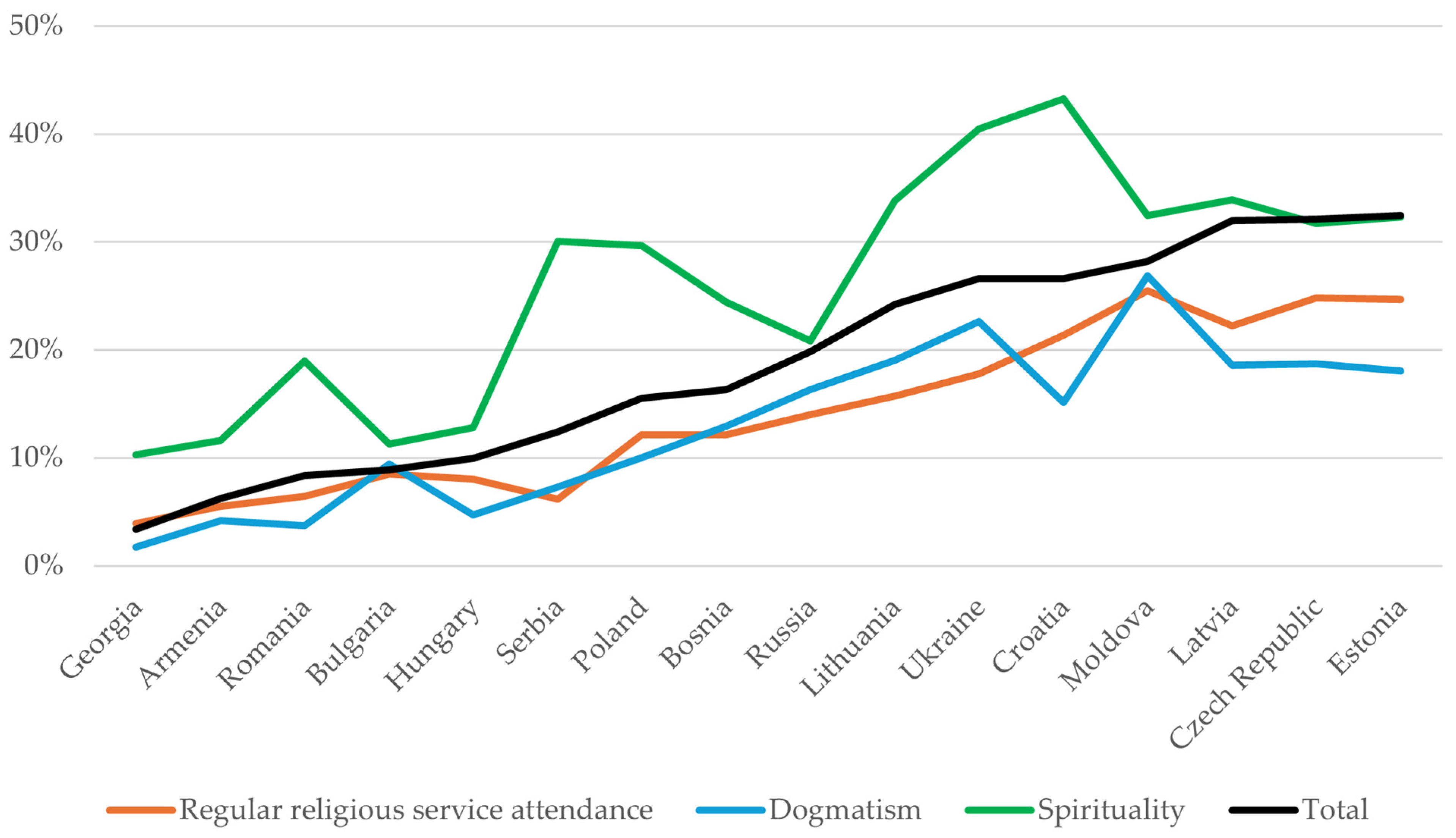

6.2. National Identity, Religion, Religiosity, and Spirituality

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CEE | Central and Eastern Europe |

| ISSP | International Social Survey Programme |

| SBNR | Spiritual but not religious |

| 1 | Russia, as the centre of the Tsarist Empire, was an exception, where the dominant Orthodox Church was also able to develop into a vital component of national identity, partly because of its traditionally close ties to the state (cf. Spohn 2012, p. 41). |

| 2 | The integrated database for the fourth wave of this module (2023) is not yet accessible and is expected to be published in early 2026. |

| 3 | In investigating whether the types found via cluster analysis form a Guttman or Mokken scale, Belarus showed much lower values than the other countries in terms of both the Coefficient of Reproducibility and Loevinger’s coefficient H. We can only guess the reason for this, but the fact that the results are difficult to comprehend might be due to the authoritarian conditions under which the survey was conducted. |

| 4 | The wording of the question is as follows: “Some people say that the following things are important for being truly [SURVEY COUNTRY CITIZENSHIP]. Others say that they are not important. How important do you think each of the following is?—To have (SURVEY COUNTRY CITIZENSHIP) family background” (4-point scale, 1 = not at all important, 4 = very important; recoded into the reversed direction). |

| 5 | For the wording of the question, see the previous note. Item text: “To respect the country’s institutions and laws”. |

| 6 | “Please tell me if you completely agree, mostly agree, mostly disagree or completely disagree with the following statement(s)?—Our people are not perfect, But our culture is superior to others” (4-point scale, 1 = completely disagree, 4 = completely agree; recoded into the reversed direction). |

| 7 | “How proud are you to be a citizen of (survey country)? Very proud, somewhat proud, not very proud, or not proud at all (4-point scale, 1 = not proud at all, 4 = very proud; recoded into the reversed direction). |

| 8 | The item comes from the same set of questions as the other items pertaining to belonging. For the wording of the question, see note 4. The item is “To be a (INSERT DOMINANT DENOMINATION OF SURVEY COUNTRY, FOR EXAMPLE RUSSIAN ORTHODOX, GREEK ORTHODOX ETC.)”. |

| 9 | The Pew study measured this with a separate question among Muslims and other respondents. While non-Muslims were generally asked about how often they participated in religious services other than weddings and funerals, Muslims were asked how often they attend the mosque for salah, the daily ritual prayers. The combined frequency of ceremony attendance was computed by combining these two questions. Question wording for non-Muslims: “Aside from weddings and funerals, how often do you attend religious services … more than once a week, once a week, once or twice a month, a few times a year, seldom, or never?” For Muslims: “On average, how often do you attend the mosque for salah? More than once a week, once a week for Friday afternoon Prayer, once or twice a month, a few times a year, especially for Eid, seldom or never?” |

| 10 | The wording of the question: “Please tell me whether the first statement or the second statement is most similar to your point of view—even if it does not precisely match your opinion” (1 = There is only one true way to interpret the teachings of my religion, 2 = There is more than one true way to interpret the teachings of my religion, 3 = neither/both equally). This question was only asked of those who have a religious affiliation. |

| 11 | In doing so, we relied on the recognition that although religiosity and the individual importance of religion are not identical concepts, they are closely related, as indicated by the strong positive correlation between the two (Huber and Huber 2012; Svob et al. 2019). The wordings of the questions from which we constructed the SBNR category are: “How often, if at all, do you feel a deep connection with nature and the earth” (4-point scale, 1 = never, 4 = often; recoded into the reversed direction); “How important is religion in your life—very important, somewhat important, not too important or not at all important?” (4-point scale, 1 = not at all important, 4 = very important; recoded into the reversed direction). We considered those who scored 3 or 4 on the spirituality question and 1 or 2 on the importance of religion to belong to the SBNR category. |

| 12 | Cluster analysis is a method of multivariate data analysis that divides objects into groups (clusters) based on several characteristics in such a way that the elements within a cluster are as homogeneous (similar) as possible, but the clusters themselves are as heterogeneous (dissimilar) as possible (Everitt et al. 2001). |

| 13 | The silhouette coefficient is an internal clustering validity index that measures how well each object lies within its assigned cluster compared to other clusters (Kaufman and Rousseeuw 1990). |

References

- Adorno, Theodor W., Else Frenkel-Brunswik, Daniel J. Levinson, and R. Nevitt Sanford. 1950. The Authoritarian Personality. New York: Harper & Brothers. [Google Scholar]

- Alemán, José M., and Dwayne Woods. 2017. Inductive Constructivism and National Identities: Letting the Data Speak. Nations and Nationalism 24: 1023–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allport, Gordon W. 1954. The Nature of Prejudice. Reading: Addison-Wesley. [Google Scholar]

- Allport, Gordon W., and J. Michael Ross. 1967. Personal Religious Orientation and Prejudice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 5: 432–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altemeyer, Bob, and Bruce Hunsberger. 1992. Authoritarianism, Religious Fundamentalism, Quest, and Prejudice. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 2: 113–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammerman, Nancy T. 2013. Spiritual But Not Religious? Beyond Binary Choices in the Study of Religion. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 52: 258–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariely, Gal. 2012. Globalisation and the Decline of National Identity? An Exploration Across Sixty-three Countries. Nation and Nationalism 18: 461–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariely, Gal. 2013. Nationhood across Europe: The Civic-Ethnic Framework and the Distinction between Western and Eastern Europe. Perspectives on European Politics and Society 14: 123–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariely, Gal. 2020. Measuring Dimensions of National Identity across Countries: Theoretical and Methodological Reflections. National Identities 22: 265–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahna, Miloslav, Magdalena Pisková, and Miroslav Tižik. 2009. Shaping of National Identity in the Processes of Separation and Integration in Central and Eastern Europe. In The International Social Survey Programme 1984–2009. Charting the Globe. Edited by Max Haller, Roger Jowell and Tom W. Smith. London: Routledge, pp. 246–66. [Google Scholar]

- Barry, David M. 2020. The Relationship Between Religious Nationalism, Institutional Pride, and Societal Development: A Survey of Postcommunist Europe. Journal of Developing Societies 36: 77–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batson, C. Daniel, Patricia Schoenrade, and W. Larry Ventis. 1993. Religion and the Individual: A Social-Psychological Perspective. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, Peter L., ed. 1999. Desecularization of the World. Resurgent Religion and World Politics. Washington, DC and Grand Rapids: Ethics and Public Policy Center/Eerdmans. [Google Scholar]

- Blank, Thomas, and Peter Schmidt. 2003. National Identity in a United Germany: Nationalism or Patriotism? Political Psychology 24: 289–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borowik, Irena. 2002. Between Orthodoxy and Eclecticism: On the Religious Transformations of Russia, Belarus and Ukraine. Social Compass 49: 497–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breskaya, Olga, and Siniša Zrinščak. 2024. Religion, Moral Issues and Politics: Exploring Profiles in CEE. In Change and Its Discontents: Religious Organizations and Religious Life in Central and Eastern Europe (Annual Review of the Sociology of Religion 15). Edited by Olga Breskaya and Siniša Zrinščak. Leiden and Boston: Brill, pp. 42–75. [Google Scholar]

- Brewer, Marilynn B. 1999. The Psychology of Prejudice: Ingroup Love and Outgroup Hate? Journal of Social Issues 55: 429–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, David. 1999. Are There Good and Bad Nationalisms? Nations and Nationalism 5: 281–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brubaker, Rogers. 1992. Citizenship and Nationhood in France and Germany. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brubaker, Rogers. 1996. Nationalism Reframed: Nationhood and the National Question in the New Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bruce, Steve. 2002. God Is Dead: Secularization in the West. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Casanova, José. 1994. Public Religions in the Modern World. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Casanova, José. 1998. Between Nation and Civil Society: Ethnolinguistic and Religious Pluralism in Independent Ukraine. In Democratic Civility: The History and Cross-Cultural Possibility of a Modern Political Ideal. Edited by Robert W. Hefner. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers, pp. 203–28. [Google Scholar]

- Citrin, Jack, Beth Reingold, and Donald P. Green. 1990. American Identity and the Politics of Ethnic Change. The Journal of Politics 52: 1124–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Citrin, Jack, Cara Wong, and Brian Duff. 2001. The Meaning of American National Identity: Patterns of Ethnic Conflict and Consensus. In Social Identity, Intergroup Conflict, and Conflict Reduction. Edited by Richard D. Ashmore, Lee Jussim and David Wilder. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 71–100. [Google Scholar]

- Coenders, Marcel. 2001. Nationalistic Attitudes and Ethnic Exclusionism in a Comparative Perspective. An Empirical Study of Attitudes Toward the Country and Ethnic Immigrants in 22 Countries. Ph.D. dissertation, Catholic University of Nijmegen, Nijmegen, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- Davidov, Eldad. 2010. Nationalism and Constructive Patriotism: A Longitudinal Test of Comparability in 22 Countries with the ISSP. International Journal of Public Opinion Research 23: 88–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Figueiredo, Rui J. P., Jr., and Zachary Elkins. 2003. Are Patriots Bigots? An Inquiry into the Vices of In-Group Pride. American Journal of Political Science 47: 171–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekker, Henk, Darina Malová, and Sander Hoogendoorn. 2003. Nationalism and Its Explanations. Political Psychology 24: 345–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doktór, Tadeusz. 2001. Discriminatory Attitudes towards Controversial Religious Groups in Poland. In Religion and Social Change in Post-Communist Europe. Edited by Irena Borowik and Miklós Tomka. Kraków: NOMOS, pp. 149–62. [Google Scholar]

- Doktór, Tadeusz. 2007. Religion and National Identity in Eastern Europe. In Church and Religious Life in Post-Communist Societies. Edited by Edit Révay and Miklós Tomka. Budapest and Piliscsaba: Loisir, pp. 299–314. [Google Scholar]

- Doob, Leonard W. 1964. Patriotism and Nationalism: Their Psychological Foundations. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ellison, Christopher G., and Marc A. Musick. 1993. Southern Intolerance: A Fundamentalist Effect? Social Forces 72: 379–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everitt, Brian S., Sabine Landau, and Morven Leese. 2001. Cluster Analysis. London: Arnold. [Google Scholar]

- Fleiß, Jürgen, Franz Höllinger, and Helmut Kuzmics. 2009. Nationalstolz zwischen Patriotismus und Nationalismus? Empirisch-methodologische Analysen und Reflexionen am Beispiel des International Social Survey Programme 2003 „National Identity”. Berliner Journal für Soziologie 19: 409–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, Robert C. 2001. Spiritual, But Not Religious: Understanding Unchurched America. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Greenfeld, Liah. 1992. Nationalism: Five Roads to Modernity. Cambridge, MA and London: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Grigoryan, Lusine K., and Vladimir Ponizovskiy. 2018. The Three Facets of National Identity: Identity Dynamics and Attitudes Toward Immigrants in Russia. International Journal of Comparative Sociology 59: 403–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzymala-Busse, Anna. 2015. Nations Under God. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Grzymala-Busse, Anna. 2019. Religious Nationalism and Religious Influence. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics. New York: Oxford University Press. 21p. [Google Scholar]

- Guglielmi, Simona, and Arianna Piacentini. 2024. Religion and National Identity in Central and Eastern European Countries: Persisting and Evolving Links. East European Politics and Societies 38: 455–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helbling, Marc, Tim Reeskens, and Matthew Wright. 2016. The Mobilisation of Identities: A Study on the Relationship Between Elite Rhetoric and Public Opinion on National Identity in Developed Democracies. Nations and Nationalism 22: 744–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschhausen, Ulrike von, and Jörn Leonhard. 2001. Europäische Nationalismen im West-Ost-Vergleich: Von der Typologie zur Differenzbestimmung. In Nationalismen in Europa: West- und Osteuropa im Vergleich. Edited by Ulrike von Hirschhausen. Göttingen: Wallstein, pp. 11–45. [Google Scholar]

- Hjerm, Mikael. 1998. National Identity: A Comparison of Sweden, Germany and Australia. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 24: 451–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjerm, Mikael, and Annette Schnabel. 2010. Mobilizing Nationalist Sentiments: Which Factors Affect Nationalist Sentiments in Europe? Social Science Research 39: 527–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochman, Oshrat, Rebeca Raijman, and Peter Schmidt. 2016. National Identity and Exclusion of Non-ethnic Migrants. In Dynamics of National Identity: Media and Societal Factors of What We Are. Edited by Jürgen Grimm, Leonie Huddy, Peter Schmidt and Josef Seethaler. London: Routledge, pp. 64–82. [Google Scholar]

- Hoppenbrouwers, Frans. 2002. Winds of Change: Religious Nationalism in a Transformation Context. Religion, State & Society 30: 305–16. [Google Scholar]

- Huber, Stefan, and Odilo W. Huber. 2012. The Centrality of Religiosity Scale (CRS). Religions 3: 710–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huddy, Leonie. 2016. Unifying National Identity Research. In Dynamics of National Identity: Media and Societal Factors of What We Are. Edited by Jürgen Grimm, Leonie Huddy, Peter Schmidt and Josef Seethaler. London: Routledge, pp. 9–21. [Google Scholar]

- Huddy, Leonie, Alessandro Del Ponte, and Caitlin Davies. 2021. Nationalism, Patriotism, and Support for the European Union. Political Psychology 42: 995–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, Philip C. 2013. Spirituality and Religious Tolerance. Implicit Religion 16: 65–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunsberger, Bruce. 1995. Religion and Prejudice: The Role of Religious Fundamentalism, Quest, and Right-Wing Authoritarianism. Journal of Social Issues 51: 113–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huntington, Samuel P. 1993. The Clash of Civilizations? Foreign Affairs 72: 22–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayet, Cyril. 2012. The Ethnic-Civic Dichotomy and the Explanation of National Self-Understanding. European Journal of Sociology 53: 65–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, Frank L., and Philip Smith. 2001a. Diversity and Commonality in National Identities: An Exploratory Analysis of Cross-National Patterns. Journal of Sociology 37: 45–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, Frank L., and Philip Smith. 2001b. Individual and Societal Bases of National Identity. A Comparative Multi-Level Analysis. European Sociological Review 17: 103–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpov, Vyacheslav. 2002. Religiosity and Tolerance in the United States and Poland. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 41: 267–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpov, Vyacheslav, Elena Lisovskaya, and David Barry. 2012. Ethnodoxy: How Popular Ideologies Fuse Religious and Ethnic Identities. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 51: 638–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasianenko, Nataliia. 2020. Measuring Nationalist Sentiments in East-Central Europe: A Cross-National Study. Ethnopolitics 21: 352–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, Leonard, and Peter J. Rousseeuw. 1990. Finding Groups in Data: An Introduction to Cluster Analysis. New York: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Kemmelmeier, Markus, and David G. Winter. 2008. Sowing Patriotism, But Reaping Nationalism? Consequences of Exposure to the American Flag. Political Psychology 29: 859–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohn, Hans. 1944. The Idea of Nationalism: A Study in Its Origins and Background. New York: Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Kosterman, Rick, and Seymour Feshbach. 1989. Toward a Measure of Patriotic and Nationalistic Attitudes. Political Psychology 10: 257–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunovich, Robert M. 2006. An Exploration of the Salience of Christianity for National Identity in Europe. Sociological Perspectives 49: 435–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunovich, Robert M. 2009. The Sources and Consequences of National Identification. American Sociological Review 74: 573–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunovich, Robert M., and Randy Hodson. 1999. Conflict, Religious Identity, and Ethnic Intolerance in Croatia. Social Forces 78: 643–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kymlicka, Will. 2000. Nation-Building and Minority Rights: Comparing West and East. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 26: 183–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kymlicka, Will. 2001. Politics in the Vernacular: Nationalism, Multiculturalism, and Citizenship. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Larsen, Christian Albrekt. 2017. Revitalizing the ‘Civic’ and ‘Ethnic’ Distinction. Perceptions of Nationhood across Two Dimensions, 44 Countries and Two Decades. Nations and Nationalism 23: 970–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latcheva, Rossalina. 2011. Cognitive Interviewing and Factor-analytic Techniques: A Mixed Method Approach to Validity of Survey Items Measuring National Identity. Quality & Quantity 45: 1175–99. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Qiong, and Marilynn B. Brewer. 2004. What Does it Mean to Be an American? Patriotism, nationalism, and American identity after 9/11. Political Psychology 25: 727–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, David. 1978. A General Theory of Secularization. New York: Harper & Row. [Google Scholar]

- Molnár, Attila K. 2006. Civil or Ethnic Religion: The Case of Hungary. In Religions, Churches and Religiosity in Post-Communist Europe. Edited by Irena Borowik. Krakow: NOMOS, pp. 279–90. [Google Scholar]

- Mußotter, Marlene. 2022. We Do Not Measure What We Aim to Measure: Testing Three Measurement Models for Nationalism and Patriotism. Quality & Quantity 56: 2177–97. [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. 2017. Religious Belief and National Belonging in Central and Eastern Europe. Report. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. 2018a. Being Christian in Western Europe. Report. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. 2018b. Being Christian in Western Europe. Dataset. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. [Google Scholar]

- Piwoni, Eunike, and Marlene Mußotter. 2023. The Evolution of the Civic-Ethnic Distinction as a Partial Success Story: Lessons for the Nationalism-Patriotism distinction. Nations and Nationalism 29: 906–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollack, Detlef, and Gergely Rosta. 2017. Religion and Modernity: An International Comparison. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ramet, Sabrina P. 2019. The Orthodox Churches of Southeastern Europe: An Introduction. In Orthodox Churches and Politics in Southeastern Europe. Nationalism, Conservativism, and Intolerance. Edited by Sabrina Ramet. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Reeskens, Tim, and Marc Hooghe. 2010. Beyond the Civic-Ethnic Dichotomy: Investigating the Structure of Citizenship Concepts across Thirty-three Countries. Nations and Nationalism 16: 579–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeskens, Tim, and Matthew Wright. 2014. Shifting Loyalties? Globalization and National Identity in the Twenty-First Century. In Value Contrasts and Consensus in Present-Day Europe: Painting Europe’s Moral Landscapes. Edited by Wil Arts and Loek Halman. Leiden and Boston: Brill, pp. 45–72. [Google Scholar]

- Roudometof, Victor. 1999. Nationalism, Globalization, Eastern Orthodoxy: ‘Unthinking’ the ‘Clash of Civilizations’ in Southeastern Europe. European Journal of Social Theory 2: 233–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roudometof, Victor. 2014. Globalization and Orthodox Christianity: The Transformations of a Religious Tradition. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Sahgal, Neha, and Alan Cooperman. 2024. Religion and Social Life in Central and Eastern Europe. Research Database. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. [Google Scholar]

- Sarkissian, Ani. 2024. Religious Nationalism and the Dynamics of Religious Diversity Governance in Post-Communist Eastern Europe. Ethnicities 24: 290–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulze Wessel, Martin. 2001. „Ost” und „West” in der Geschichte des europäischen Nationalismus. OST-WEST Europäische Perspektiven 3: 163–71. [Google Scholar]

- Sherif, Muzafer. 1966. Group Conflict and Cooperation: Their Social Psychology. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. [Google Scholar]

- Shulman, Stephen. 2002. Challenging the Civic/Ethnic and West/East Dichotomies in the Study of Nationalism. Comparative Political Studies 35: 554–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silver, Laura, Jonathan Evans, Maria Smerkovich, Sneha Gubbala, Manolo Corichi, and William Miner. 2025. Comparing Levels of Religious Nationalism Around the World. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Anthony D. 1991. National Identity. London: Penguin Books. [Google Scholar]

- Spohn, Willfried. 1998. Religion und Nationalismus. Osteuropa im westeuropäischen Vergleich. In Religiöser Wandel in den Postkommunistischen Ländern Ost- und Mitteleuropas. Würzburg: Ergon, pp. 87–120. [Google Scholar]

- Spohn, Willfried. 2012. Europeanization, Multiple Modernities and Religion—The Reconstruction of Collective Identities in Postcommunist Central and Eastern Europe. In Transformations of Religiosity: Religion and Religiosity in Eastern Europe 1989–2010. Edited by Gert Pickel and Kornelia Sammet. Wiesbaden: Springer VS, pp. 29–50. [Google Scholar]

- Stephan, Walter G., Kurt A. Boniecki, Oscar Ybarra, Ann Bettencourt, Kelly S. Ervin, Linda A. Jackson, Penny S. McNatt, and C. Lausanne Renfro. 2002. The Role of Threats in the Racial Attitudes of Blacks and Whites. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 28: 1242–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storm, Ingrid. 2011. Ethnic Nominalism and Civic Religiosity: Christianity and National Identity in Britain. The Sociological Review 59: 828–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svob, Connie, Lidia Y. X. Wong, Marc J. Gameroff, Priya J. Wickramaratne, Myrna M. Weissman, and Jürgen Kayser. 2019. Understanding Self-Reported Importance of Religion/Spirituality in a North American Sample of Individuals at Risk for Familial Depression: A Principal Component Analysis. PLoS ONE 14: e0224141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, Henri. 1982. Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations. Annual Review of Psychology 33: 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, Henri, and John C. Turner. 1979. An Integrative Theory of Intergroup Conflict. In The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations. Edited by William G. Austin and Stephen Worchel. Monterey: Brooks/Cole, pp. 33–47. [Google Scholar]

- Tižik, Miroslav. 2012. Religion and National Identity in an Enlarging Europe. In Crossing Borders, Shifting Boundaries. Edited by Franz Höllinger and Markus Hadler. Frankfurt am Main: Campus, pp. 101–24. [Google Scholar]

- Tomka, Miklós. 2006. Is Conventional Sociology of Religion Able to Deal with Differences between Eastern and Western European Developments? Social Compass 53: 251–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomka, Miklós, and Paul M. Zulehner. 2000. Religion im Gesellschaftlichen Kontext Ost(Mittel)Europas. Ostfildern: Schwabenverlag. [Google Scholar]

- Tomka, Miklós, and Réka Szilárdi. 2016. Religion and Nation. In Focus on Religion in Central and Eastern Europe. Edited by András Máté-Tóth and Gergely Rosta. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 75–109. [Google Scholar]

- Triandafyllidou, Anna. 2024. Religion and Nationalism Revisited: Insights from Southeastern and Central Eastern Europe. Ethnicities 24: 203–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trittler, Sabine. 2017. Explaining Differences in the Salience of Religion as a Symbolic Boundary of National Belonging in Europe. European Sociological Review 33: 708–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warhola, James W., and Alex Lehning. 2007. Political Order, Identity, and Security in Multinational, Multi-Religious Russia. Nationalities Papers 35: 933–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weil, Patrick. 2001. Access to Citizenship: A Comparison of Twenty-Five Nationality Laws. In Citizenship Today: Global Perspectives and Practices. Edited by T. Alexander Aleinikoff and Douglas Klusmeyer. Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, pp. 17–35. [Google Scholar]

- Westle, Bettina. 1999. Collective Identification in Western and Eastern Germany. In Nation and National Identity. The European Experience in Perspective. Edited by Hanspeter Kriesi, Klaus Armingeon, Hannes Siegrist and Andreas Wimmer. Zürich: Ruegger, pp. 175–98. [Google Scholar]

- Westle, Bettina. 2012. European Identity as a Contrast or an Extension of National Identity? In Methods, Theories, and Empirical Applications in the Social Sciences. Festschrift for Peter Schmidt. Edited by Samuel Salzborn, Eldad Davidov and Jost Reinecke. Wiesbaden: Springer VS, pp. 249–54. [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox, Clyde, and Ted G. Jelen. 1990. Evangelicals and Political Tolerance. American Politics Quarterly 18: 25–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, Matthew. 2011a. Diversity and the Imagined Community: Immigrant Diversity and Conceptions of National Identity. Political Psychology 32: 837–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, Matthew. 2011b. Policy Regimes and Normative Conceptions of Nationalism in Mass Public Opinion. Comparative Political Studies 44: 598–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, Matthew, Jack Citrin, and Jonathan Wand. 2012. Alternative Measures of American National Identity: Implications for the Civic-Ethnic Distinction. Political Psychology 33: 469–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wulff, David M. 1991. Psychology of Religion: Classic and Contemporary Views. New York: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Zinnbauer, Brian J., Kenneth I. Pargament, Brenda Cole, Mark S. Rye, Eric M. Butter, Timothy G. Belavich, Kathleen M. Hipp, Allie B. Scott, and Jill L. Kadar. 1997. Religion and Spirituality: Unfuzzying the Fuzzy. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 36: 549–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type | Our People Are Not Perfect, But Our Culture Is Superior to Others | How Important Do You Think—Family Background | How Proud Are You to Be a Citizen of Country | How Important Do You Think—To Respect the Country’s Institutions and Laws | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nationalist | 3.49 | 3.62 | 3.54 | 3.60 | 11,008 |

| Ethnic | 1.68 | 3.52 | 3.31 | 3.52 | 5339 |

| Patriotic | 2.16 | 1.71 | 3.06 | 3.31 | 3771 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Müller, O.; Rosta, G. National Identity, Religion, and Religiosity in Central and Eastern Europe: Types, Patterns, and Correlations. Religions 2025, 16, 1527. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16121527

Müller O, Rosta G. National Identity, Religion, and Religiosity in Central and Eastern Europe: Types, Patterns, and Correlations. Religions. 2025; 16(12):1527. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16121527

Chicago/Turabian StyleMüller, Olaf, and Gergely Rosta. 2025. "National Identity, Religion, and Religiosity in Central and Eastern Europe: Types, Patterns, and Correlations" Religions 16, no. 12: 1527. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16121527

APA StyleMüller, O., & Rosta, G. (2025). National Identity, Religion, and Religiosity in Central and Eastern Europe: Types, Patterns, and Correlations. Religions, 16(12), 1527. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16121527