From Kasaya to Haiqing: The Evolution of Monastic Robes and Identity Reformation in Chinese Buddhism

Abstract

1. Introduction

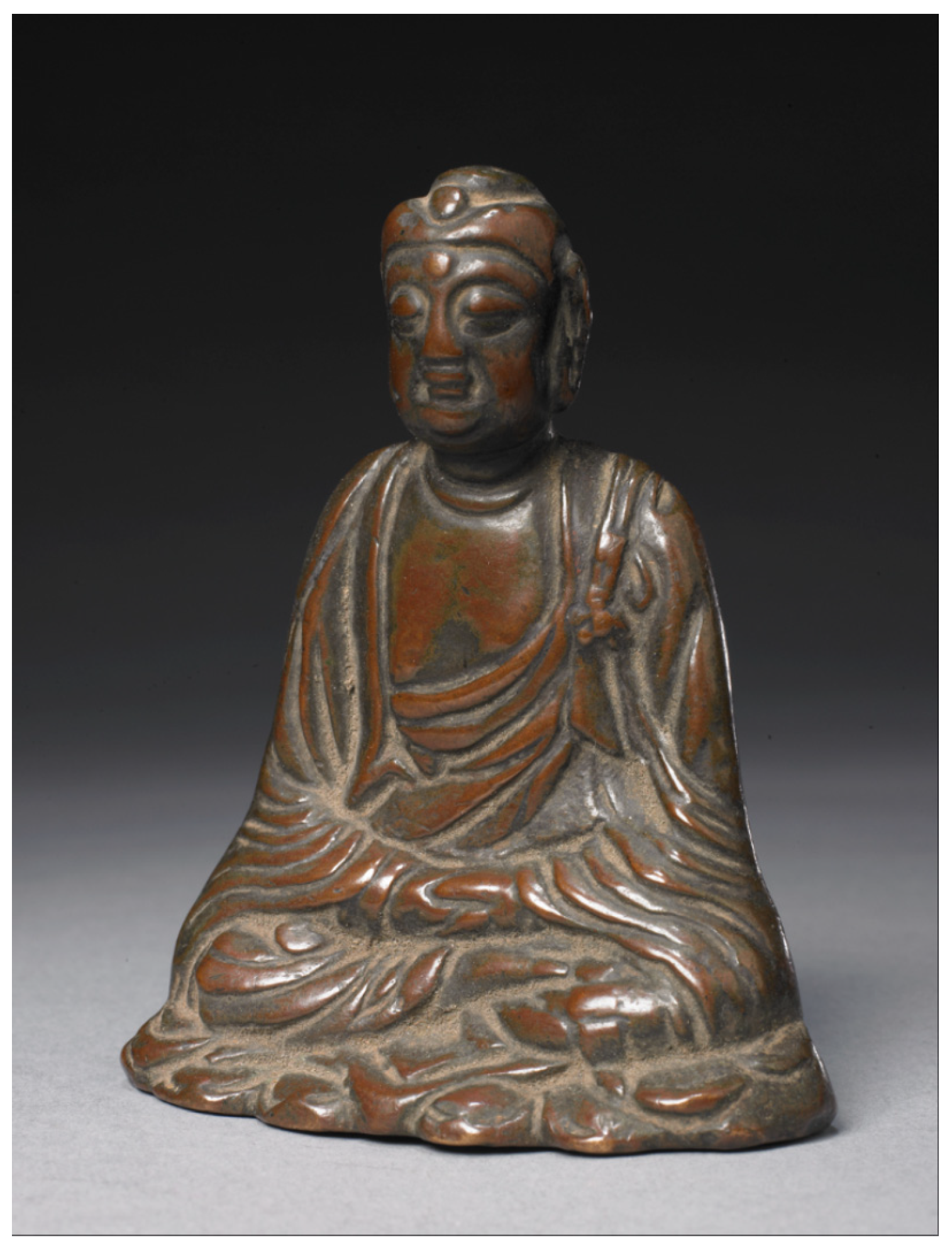

2. The Basic Regulations of Indian Buddhist Kasaya and Its Initial Adaptation in China

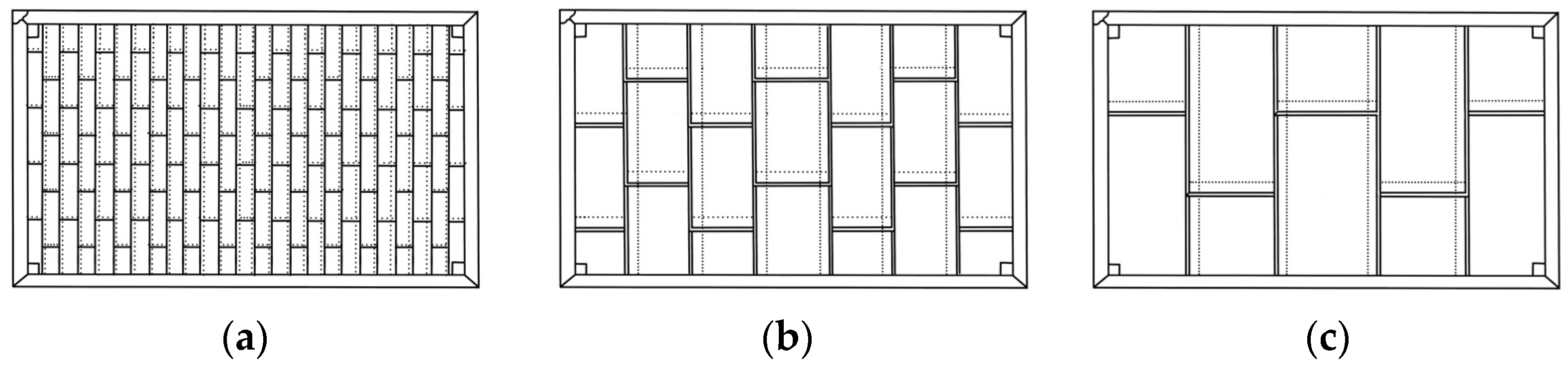

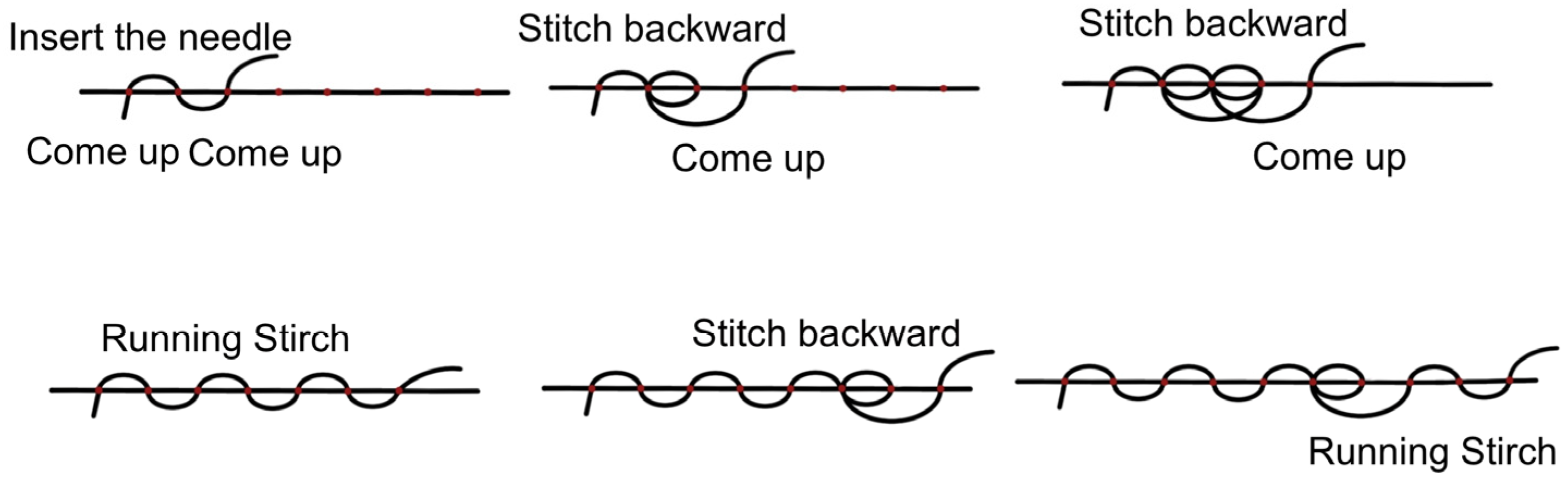

2.1. The Basic Regulations of Indian Buddhist Kasaya and Its Symbolic Meaning

2.2. The Initial Adaptation of Kasaya in China: Challenges of Climate and Culture

2.3. The Inheritance and Transformation of the “Three Robes” System in China

3. The Localized Innovation of Chinese Buddhism Monastic Attire

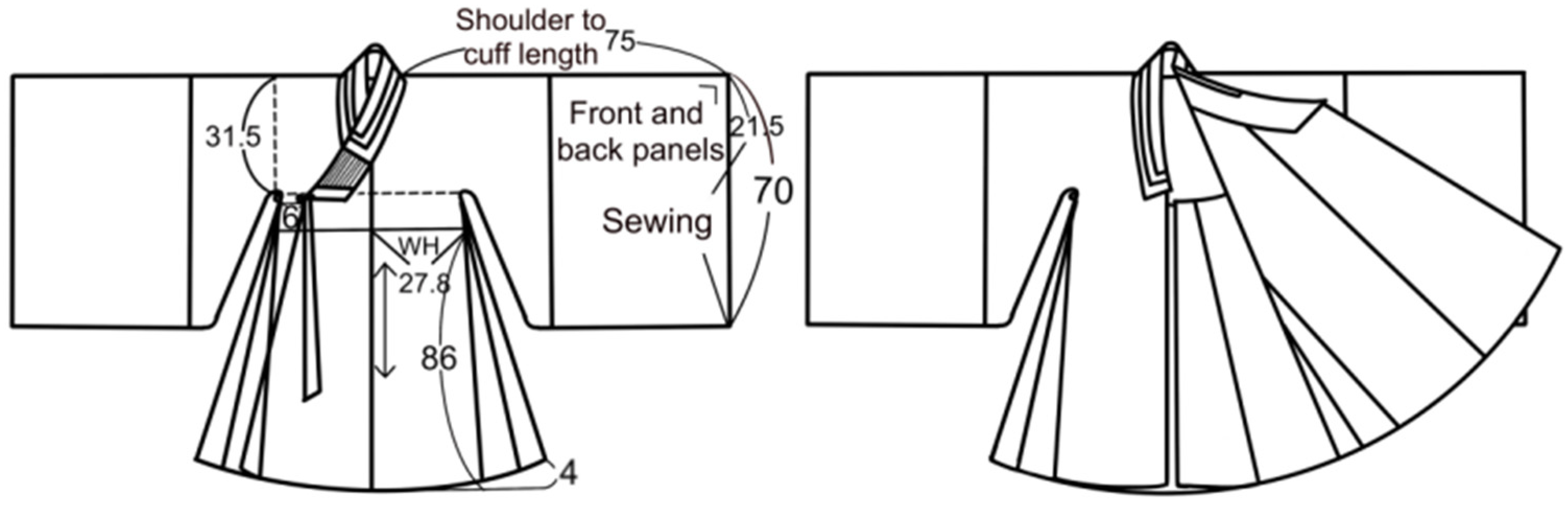

3.1. The Creation of Haiqing and Its Cultural Connotations

3.2. The Reconstruction of Monastic Robe Color System and Hierarchical Structure

3.3. Localized Transformation of Monastic Robe Materials and Manufacturing Techniques

4. Discussion: Power Relations and Identity Reconstruction in the Evolution of Monastic Robes

4.1. Harmonious Mechanisms of Cross-Cultural Adaptation and Cultural Capital Accumulation

4.2. Multi-Dimensional Power Structure Interactions in Monastic Robe Evolution

4.3. The Multi-Dimensional Construction of Chinese Buddhism Monk Identity Recognition

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | The “Ziyuan” (字苑) was an important lexicographic work compiled by Ge Hong葛洪 (approximately 283–343 or 363 CE), a famous Daoist scholar, alchemist, and medical practitioner of the Western Jin period in China. Ge Hong’s primary purpose in writing this work was believed to be correcting and supplementing the deficiencies and errors in Xu Shen’s 许慎 “Shuo Wen Jie Zi” 说文解字 from the Eastern Han period. Unlike the “Shuo Wen Jie Zi” which focused on small seal script and ancient characters, the “Ziyuan” was thought to include more characters actually used during the late Han and Wei-Jin periods, possibly including new characters, vulgar characters, variant characters, and even dialectal characters of that time, with explanations of their form, pronunciation, and meaning. |

| 2 | The Śāriputraparipṛcchā Sūtra (She Li Fu Wen Jin 舍利弗问经) is an important early Buddhist scripture belonging to the Vinaya Piṭaka literature. This sutra adopts a question-and-answer format and is an important document for studying Mahāsāṅghika vinaya thought, the history of early Buddhist precept establishment, and monastic community organizational structure. It records Buddha’s foremost disciple in wisdom, Śāriputra, asking Buddha about the origins of bhikṣu and bhikṣuṇī precepts (Vinaya), the circumstances of their establishment, specific regulations, and Saṅgha operations, with Buddha providing answers to each question. It details the historical process and reasons for how various precept regulations were gradually established in response to various events and monastic behaviors during the early development of the Buddhist monastic community. The extant Chinese translation is usually attributed to the Eastern Jin period (317–420 CE) and is catalogued as T1465 in the “Taishō Shinshū Daizōkyō” (大正新脩大藏经 Taisho Tripitaka), included in volume 24 (Vinaya section). |

| 3 | Seng Jia Gui Fan (僧伽规范 Monastic rules) refer to a comprehensive system of regulations, principles, and institutions that govern and guide the behavior, lifestyle, spiritual practice, and internal operations of Buddhist monastic communities, constituting the behavioral standards and communal order that monastics must observe. The core content primarily derives from the Buddhist Vinaya Piṭaka, which provides detailed regulations for individual monastics to uphold the Prātimokṣa as well as collective monastic life and operational procedures, such as ordination ceremonies, rains retreat, confession rituals, and other daily requirements, along with karma procedures for handling monastic affairs. The purpose of establishing Seng Jia Gui Fan is to help monastics restrain their body and mind to facilitate spiritual practice and liberation, maintain the harmony and purity of the monastic community, ensure the long-term preservation of the Dharma, and earn the respect and support of lay devotees. Due to differences in the specific Vinaya texts and interpretations upon which various Buddhist traditions rely, the specific practical details of Seng Jia Gui Fan exhibit certain diversity across different traditions. However, as the cornerstone that maintains both individual monastic practice and collective monastic life, Seng Jia Gui Fan hold fundamental importance within the entire Buddhist system. |

| 4 | Sarvāstivāda (Sa Po Duo 萨婆多), the transliteration of Sanskrit Sarvāstivāda, meaning “School That Says Everything Exists” or simply “Existence School”, was an extremely important and influential school during early Buddhism (sectarian Buddhist period). Its core doctrine advocates “the real existence of the three times, with dharma essence eternally present”, believing that the fundamental elements “dharma” constituting the world possess real, eternally unchanging self-nature (svabhāva) across past, present, and future. This school emerged from the Theravāda around the 3rd century BCE, later flourishing especially in northern India, particularly in Kashmir and Gandhāra regions, renowned for its highly developed and systematized Abhidharma philosophical system, with representative treatises including the “Jñānaprasthāna” and its authoritative commentary “Mahāvibhāṣā”, hence also called “Vaibhāṣika”. |

| 5 | “Shan cai tongzi wu shi san can” (善财童子五十三参 Sudhana’s Fifty-Three Pilgrimages) is an important story from the Buddhist scripture “Avatamsaka Sutra”, telling of the young monk Sudhana’s experiences visiting fifty-three spiritual teachers during his cultivation journey. These teachers came from different backgrounds, representing diverse wisdom and cultivation methods. |

| 6 | The “ci zi” 赐紫 was an important honorary system in ancient China, specifically referring to the qualification granted by the emperor or court to specific officials, monks, or Daoists to wear purple court robes or Dharma robes. “Purple” was regarded as a noble color in ancient China (especially from the Tang dynasty onward), associated with imperial power and high-ranking status. |

References

- Bai, Huawen 白化文. 2009. Hanhua Fojiao Sanbao Wu 汉化佛教三宝物 (The Sinicization of the Three Jewels in Buddhism). Beijing: Hualing Press. [Google Scholar]

- Batten, Alicia J. 2010. Clothing and adornment. Biblical Theology Bulletin 40: 148–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, Catherine. 1997. Ritual: Perspectives and Dimensions. Oxford: Oxford University Press, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Buddhabhadra, and Faxian, trans. 1934. Mahāsāṅghika Vinaya (摩诃僧祇律). In Taishō shinshū daizōkyō 大正新脩大藏經 (Taishō Revised Tripitaka). Tokyo: Daizō Shuppansha, vol. 22. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Shana 常沙娜. 1986. Dunhuang Lidaishi Fushi Tuxiang 敦煌历代服饰图案 (Dunhuang Clothing Patterns of Various Dynasties). Hong Kong: Wanli Bookstore. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, In Young. 1999. A Buddhist View of Women: A Comparative Study of the Rules for Bhikłuõćs and Bhikłus Based on the Chinese Prątimokła. Journal of Buddhist Ethics 6: 29–105. [Google Scholar]

- Daoxuan 道宣. 1934. Si Fen Lu Shan Fan Buque Xing Shi Chao 四分律删繁补阙行事钞 (The Sifen lü, Unnecessary Details Removed and Gaps Filled from Other Sources). In Taishō shinshū daizōkyō 大正新脩大藏經 (Taishō Revised Tripitaka). Tokyo: Daizō Shuppansha, vol. 40. [Google Scholar]

- Dehui 德辉. 1934. Chixiu Bai Zhang Qinggui 敕修百丈清规 (The Imperially Revised Pure Regulations of Baizhang). In Taishō shinshū daizōkyō 大正新脩大藏經 (Taishō Revised Tripitaka). Tokyo: Daizō Shuppansha, vol. 48. [Google Scholar]

- Droeber, Julia. 2005. Dressed to Impress? Clothes, Religiousness, and a Language of Symbols. In Dreaming of Change: Young Middle-Class Women and Social Transformation in Jordan. Leiden: Brill, pp. 256–94. [Google Scholar]

- Eicher, Joanne B., and Mary E. Higgins Roach. 1992. Definition and Classification of Dress: Implications for Analysis of Gender Roles. Oxford: Berg Publishers, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Eliade, Mircea. 2022. Patterns in Comparative Religion. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. [Google Scholar]

- Eliot, Charles. 1998. Hinduism and Buddhism: An Historical Sketch. Hove: Psychology Press, pp. 53–56. [Google Scholar]

- Erel-Koselleck, Ebru Seda. 2004. The Role and Power of Symbols in the Identity Formation of Community Members. Master’s thesis, Middle East Technical University, Ankara, Turkey. [Google Scholar]

- Fayun 法云. 1934. Fanyi Mingyi Ji 翻译名义集 (Collection of Translated Terms). In Taishō shinshū daizōkyō 大正新脩大藏經 (Taishō Revised Tripitaka). Tokyo: Daizō Shuppansha, vol. 54. [Google Scholar]

- Fotu, Baturuo, and Faxian, trans. 1934. Mahāsāṅghika Vinaya 摩诃僧祇律 (The Mahasanghika Vinaya). In Taishō shinshū daizōkyō 大正新脩大藏經 (Taishō Revised Tripitaka). Tokyo: Daizō Shuppansha, vol. 22. [Google Scholar]

- Fotu, Yeshe 佛陀耶舍, and Fonian Zhu 竺佛念, trans. 1934. Sifen Lü 四分律 (The Four-Part Vinaya). In Taishō shinshū daizōkyō 大正新脩大藏經 (Taishō Revised Tripitaka). Tokyo: Daizō Shuppansha, vol. 22. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, Yingying 葛英颖. 2011. Handi Fojiao Fushi Wenhua Yanjiu 汉地佛教服饰文化研究 (Research on Buddhist Costume Culture in Han China). Ph.D. dissertation, Jilin University, Changchun, China. [Google Scholar]

- Goossaert, Vincent, and David A. Palmer. 2011. The Religious Question in Modern China. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Harms, Ernst. 1938. The psychology of clothes. American Journal of Sociology 44: 239–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heirman, Ann. 2014. Washing and dyeing Buddhist monastic robes. Acta Orientalia 67: 467–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heirman, Ann, and Mathieu Torck. 2012. A Pure Mind in a Clean Body: Bodily Care in the Buddhist Monasteries of Ancient India and China. Cambridge: Academia Press. [Google Scholar]

- Huijiao 慧皎. 1934. Gaoseng Zhuan 高僧传 (Biographies of Eminent Monks). In Taishō shinshū daizōkyō 大正新脩大藏經 (Taishō Revised Tripitaka). Tokyo: Daizō Shuppansha, vol. 50. [Google Scholar]

- Kieschnick, John. 2003. The Impact of Buddhism on Chinese Material Culture. Princeton: Princeton University, p. 223. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Hyosook. 2025. Buddhist Robes That Are and Are Not: Clothing, Desire, and Ambivalent Renunciation in The Tale of Genji. Religions 16: 735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumārajīva, trans. 1934. Daśabhūmika-vibhāṣā-śāstra (十住毗婆沙论). In Taishō shinshū daizōkyō 大正新脩大藏經 (Taishō Revised Tripitaka). Tokyo: Daizō Shuppansha, vol. 26. [Google Scholar]

- Kuo, Huey-Jen 郭慧珍. 1999. Hanzu Fojiao Sengjia Fuzhuang Zhi Yanjiu 漢族佛教僧伽服裝之研究 (A study of costume of Chinese Buddhist monks). Chung-Hwa Institute of Buddhist Studies 3: 175–206. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, Yoon-Hee. 1991. The influence of the perception of mood and self-consciousness on the selection of clothing. Clothing and Textiles Research Journal 9: 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Yuen Ting. 2015. Wu Zhao: Ruler of Tang Dynasty China. Ann Arbor: The Association for Asian Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Lennon, Sharron J., and Leslie L. Davis. 1989a. Clothing and human behavior from a social cognitive framework Part I: Theoretical perspectives. Clothing and Textiles Research Journal 7: 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lennon, Sharron J., and Leslie L. Davis. 1989b. Clothing and human behavior from a social cognitive framework Part II: The stages of social cognition. Clothing and Textiles Research Journal 8: 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Yanshou 李延寿. 1974. Bei Shi 北史 (History of the Northern Dynasties). Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company. [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno, Hiroto 水野弘元. 1975. Bukkyō no Chūgoku-Teki Tenkai 佛教の中国的展開 (Chinese Development in Buddhism). Tokyo: Shūnju-sha. [Google Scholar]

- Perrot, Philippe. 1981. Suggestions for a different approach to the history of dress. Diogenes 29: 157–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pöllmann, Andreas. 2013. Intercultural capital: Toward the conceptualization, operationalization, and empirical investigation of a rising marker of sociocultural distinction. Sage Open 3: 2158244013486117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Zhenjie, and Limin Liu. 2025. The Historical Evolution and Indigenous Pathways of Christian–Buddhist Dialogue in China: A Perspective from Religious Dialogue Theories. Religions 16: 1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Daocheng 释道诚. 1934. Shi Shi Yao Lan 释氏要览 (Essential Survey of the Buddhist Tradition). In Taishō shinshū daizōkyō 大正新脩大藏經 (Taishō Revised Tripitaka). Tokyo: Daizō Shuppansha, vol. 54. [Google Scholar]

- Shinohara, Koichi. 2014. Spells, Images, and Mandalas: Tracing the Evolution of Esoteric Buddhist Rituals. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Silk, Jonathan A. 2008. Managing Monks: Administrators and Administrative roles in Indian Buddhist Monasticism. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Maoxia 孙茂霞. 2016. Handian Fojiao Sengyi Mantan (汉传佛教僧衣漫谈). Zhongguo Zongjiao (中国宗教) 8: 70–71. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Yijie. 2015. Confucianism, Buddhism, Daoism, Christianity and Chinese Culture. Heidelberg: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Tarlo, Emma. 1996. Clothing Matters: Dress and Identity in India. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, Victor. 2017. Roger Abrahams, and Alfred Harris. In The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure. Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Yifa. 2017. The Origins of Buddhist Monastic Codes in China: An Annotated Translation and Study of the Chanyuan Qinggui. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. [Google Scholar]

- Yijing 义净, trans. 1934a. Nan Hai Ji Gui Nei Fa Zhuan 南海寄归内法传 (A Record of the Buddhist Religion as Practiced in India and the Malay Archipelago). In Taishō shinshū daizōkyō 大正新脩大藏經 (Taishō Revised Tripitaka). Tokyo: Daizō Shuppansha, vol. 54. [Google Scholar]

- Yijing 义净, trans. 1934b. Fugen Shuoyi Yubu Vinaya Zashi 根本说一切有部毗奈耶杂事 (The Vinaya of the Sarvāstivāda). In Taishō shinshū daizōkyō 大正新脩大藏經 (Taishō Revised Tripitaka). Tokyo: Daizō Shuppansha, vol. 24. [Google Scholar]

- Yuanzhao 元照. 1934. Sifen Lv Xingshi Chao Zichiji 四分律行事钞资持记 (Commentary on the Expanded Vinaya Treatise). In Taishō shinshū daizōkyō 大正新脩大藏經 (Taishō Revised Tripitaka). Tokyo: Daizō Shuppansha, vol. 40. [Google Scholar]

- Zanning 赞宁. 1934. Dasong Sengshi Lue 大宋僧史略 (A Brief History of Monks in the Song Dynasty). In Taishō shinshū daizōkyō 大正新脩大藏經 (Taishō Revised Tripitaka). Tokyo: Daizō Shuppansha, vol. 54. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Tingyu 张廷玉, Wenyuan Xu 徐元文, Fangai Ye 叶方蔼, Yushu Zhang 张玉书, Qianxue Xu 徐乾学, Hongxu Wang 王鸿绪, Sitong Wan 万斯同, Quan Feng 冯铨, Chengchou Hong 洪承畴, Jiantai Li 李建泰, and et al. 1974. Ming Shi (明史). Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Jiajia. 2025. An Exceptional Category of Central Monastic Officials in the Tang Dynasty: A Study of the Ten Bhadantas During the Reigns of Gaozu, Empress Wu, and Zhongzong. Religions 16: 1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, H.; Han, P.; Liu, L. From Kasaya to Haiqing: The Evolution of Monastic Robes and Identity Reformation in Chinese Buddhism. Religions 2025, 16, 1463. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16111463

Chen H, Han P, Liu L. From Kasaya to Haiqing: The Evolution of Monastic Robes and Identity Reformation in Chinese Buddhism. Religions. 2025; 16(11):1463. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16111463

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Han, Peiqi Han, and Lixian Liu. 2025. "From Kasaya to Haiqing: The Evolution of Monastic Robes and Identity Reformation in Chinese Buddhism" Religions 16, no. 11: 1463. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16111463

APA StyleChen, H., Han, P., & Liu, L. (2025). From Kasaya to Haiqing: The Evolution of Monastic Robes and Identity Reformation in Chinese Buddhism. Religions, 16(11), 1463. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16111463