Abstract

The “Wawa Pampay” is an Andean funeral ritual that allows Quechua-speaking communities to collectively process grief over the death of a child, integrating ancestral beliefs and symbolic practices that have been passed down over generations. This study aimed to understand the cultural and emotional significance of this ritual, as well as to document its symbolic elements in light of the risk of its disappearance due to sociocultural changes. A qualitative approach integrating ethnographic methodology was used, combining participant observation, in-depth interviews in the Quechua language, and photographic and audiovisual recording, while always respecting the beliefs and privacy of the participants. The fieldwork was carried out in a rural community in the Peruvian Andes, with extended visits and cohabitation with the families. The findings show that the “Wawa Pampay” not only bids farewell to the deceased child but also reaffirms social cohesion and strengthens collective memory. Its preservation is key to keeping local cultural identity alive.

1. Introduction

Cultural expressions in the Andean communities of Peru share similarities with other South American cultures, although they retain unique characteristics within their local structures. The traditional conception of the life cycle—birth and death—is deeply rooted in these practices. Within this framework, marriage customs play a fundamental role in changes in reproductive patterns, as they reflect tensions and transformations in social relations. Those accompanying mourning express the expectation that the marriage will bring more children; therefore, the death of a child should be met with joy. As Balán (1996) points out, “the broader relevance of marriage customs for the fertility transition becomes more evident when intergenerational relations and gender relations are considered separately” (p. 70). This highlights the need to analyze these dynamics independently in order to understand the demographic transition surrounding Wawa Pampay (the burial of a deceased infant).

The Andean communities of Peru, which are located mainly in the highlands, preserve symbolic and spiritual structures that organize their collective life. This research was conducted in the village of Magnupampa, located 2300 m above sea level in the Torobamba Valley, La Mar Province, Ayacucho region. This settlement functioned as a hacienda until the arrival of the armed movement Sendero Luminoso, whose members expelled the landowners but left the manor house intact, unlike other haciendas that were completely burned down. At present, the manor house remains abandoned, and the population is primarily engaged in avocado exporting. In the 1980s, the community was struck by a yellow fever epidemic that caused the death of numerous children, a situation compounded by the violence of the armed movement, which further decimated the population.

In this cultural context, “the apus or wamanis (very tall mountains) are organized in a pyramidal hierarchy in which the deities are ranked according to their importance” (Leoni 2005, p. 154). This organization reflects a worldview in which guardian deities occupy hierarchical positions linked to their spiritual and territorial power, structuring the relationship between the sacred and the community. However, since “the 1960s, Huamanga and its surroundings have undergone a rapid process of urbanization and migration from the countryside to the city, which intensified in the 1980s with the internal armed conflict, altering the traditional social organization” (Gutiérrez Martínez and Rojas Porras 2021, p. 376). These transformations have generated tensions between modernity and tradition, although a notable Andean cultural resistance persists.

Andean societies in Peru face various grievances from sectors of the capital, including terruqueo and discrimination based on their culture and origin. As has been noted, “political accusations against farmers in the Peruvian highlands are common, in the sense that anyone who protests against the government in power is branded a terrorist (terruqueo) by the Peruvian press, which is mainly owned by large corporations” (Gutiérrez-Gómez et al. 2023, p. 5). Ancestral expressions linked to burials in Andean villages are manifested through rituals that reinforce local identity and have become collectively widespread. On the cultural level, rituals similar to those addressed in this research are recognized within Andean communities. One of its variants is the Andean marriage proposal, known as Warmi urquy, which “presents rituals similar to the llumchuy waqachi potato test” (Gutiérrez-Gómez et al. 2024, p. 4). This ritual expresses emotional bonds through symbolic practices that reinforce gender roles and cultural belonging, in close relation to Wawa pampay.

In the Peruvian Andes, the existential dimension is articulated through rituals and beliefs passed down orally, which express conceptions about life and death. These beliefs are communicated mainly in Quechua, an ancestral language that is still used in several regions. According to Andrade Ciudad and Howard (2021), “when speaking in one’s own indigenous language, runasimi is also sometimes used in the Peruvian regions of Ayacucho, Huancavelica, Apurímac, and Cuzco, and runasimi in Ecuador” (p. 8). This use of Runasimi (the speech of the man) reflects a cultural continuity that transcends national borders. However, today’s everyday speech combines Quechua and Spanish spontaneously, without a standardized linguistic structure.

In this research, this hybrid form of expression was respected during data collection, considering its cultural and communicative value. In the rituals of Andean communities, expressions of religious syncretism persist, evidenced in the practice of worshiping “Catholic saints, while internally continuing to worship their own, thus giving rise to the second process of transculturation” (Baby-Ramírez et al. 2025, p. 225). This strategy allowed them to keep their traditional deities alive, hidden under Christian symbols, generating a profound transculturation between both worldviews.

Generational changes, together with access to information and formal education, substantially transform perceptions of ancestral cultural practices. In this sense, it is understood that “in our modernity they would be at the very least complicated to intertwine, such as the mountains, Marian devotion, labor exploitation, and the end of times with the succession of different humanities” (Amuedo and Vilte 2019). This statement reflects a cultural complexity that intertwines religiosity, nature, labor exploitation, and apocalyptic visions, highlighting the tensions between modernity and tradition.

The death of newborns was considered an isolated phenomenon, so a simple ritual was performed: “take a jar of pure water, recite a Christian prayer, make the sign of the cross, pour the water over the head of the dying child, and name them after the civil name of the saint of the day” (Alberdi Vallejo 2010). This act reflects the fusion between Andean and Christian rituals, showing how symbolic baptism integrates faith, identity, and the spiritual farewell of the child. It is important to consider that, according to García Miranda and Leiva Ochoa (2019), “the causes of mortality are countless, and due to their short life in this world and their innocence, they occupy a special place, being the clearest link between this world and the other.” This highlights that deceased children, because of their innocence and brief lives, act as spiritual bridges between worlds.

Quechua songs also occupy a central place in community life: “they correspond to the songs of the life cycle (marriage, wasichakuy—house blessing—new home, aya taki—song of the dead, and wawa pampay—children’s burial)” (Montoya 1996). This indicates that certain Quechua songs accompany life-cycle rituals, from marriage to children’s funerals, marking social and spiritual stages. In these rituals, the family fulfills important roles: “godfather or godmother of the child, who are obligated to pay for the shroud and the coffin. The wake is reduced to a proper celebration accompanied by jarahuis and taquis danced to the rhythm and beat of the harp and violin” (Cavero Carrasco 1985). Thus, the infant funeral ritual combines family responsibility, community tradition, and musical celebration, integrating culture, economy, and socialization.

2. Results

2.1. Symbolic Meaning of the “Wawa Pampay” Ritual

Andean communities interpret childbirth and infant death from their own worldviews, which are transmitted orally and differ depending on the territory. Unlike homogeneous views, each group of people expresses unique rituals and meanings regarding life and death. In this context, Dubois (2012) argues that “most of the graves belong to adults, but a good number of enchytrisms have been excavated, as well as graves of older children” (p. 41), reflecting a diversity of funeral practices based on age and possibly social status. This diversity is also expressed in the oral testimony of an informant: “Before, there were no vaccines, that’s why the children died, from whooping cough, also from measles, more died from measles, it took ten, you see?” Freely translated, this points out that vaccines did not exist in the past, and many children died from whooping cough or measles, even in groups of ten. This account reinforces the understanding of high infant mortality and its symbolic meanings in pre-modern Andean contexts.

The “Wawa Pampay” ritual (burial of a deceased baby) is a deeply symbolic practice in the Peruvian Andes. In the community studied, this rite represents an essential moment of emotional transformation. This type of attention to infant bodies is not exclusive to the Andes; distinctive funeral practices were also recorded in Roman contexts: “firstly, with the group of premature babies around the bathhouse in the late Roman phase, and secondly, with the burial of the cremated remains of some children alongside adults” (Millett and Gowland 2015, p. 183). This arrangement shows a possible symbolic and social hierarchy of children’s bodies, which suggests different ideas about childhood and death. Even so, these findings need more historical and archeological interpretation. In the Andean worldview, this meaning is expressed in the testimony of a community member: “When the little boy died, we buried him with new clothes, with much joy; when my older brother died, it was sad, that was our custom, you see?”; that is, when the child died, he was dressed in white and buried with joy, without sadness, as part of an ancestral practice that reinterprets death from a ritual and collective experience.

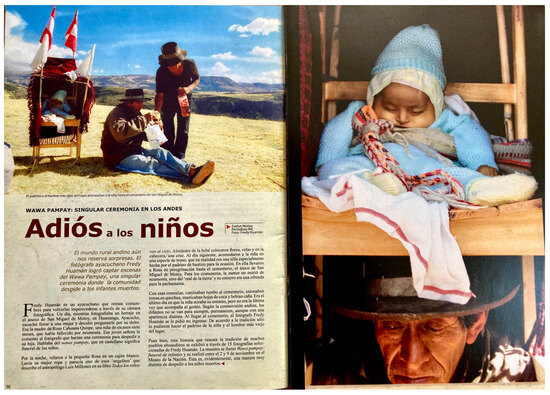

The Andean ritual of burying a deceased baby is experienced as a local festival. A special chair decorated with flowers is prepared, in which the child is carried to the cemetery accompanied by dancing and singing. In this process, the godfather who performed the baptism plays a fundamental role, as Catholic baptism is considered essential for the child’s soul to attain eternal glory. As can be seen in Figure 1, the ritual symbols are arranged in a particular way Fredy Huamán (2007).

Figure 1.

The documentary photo depicts Wawa Pampay, a children’s funeral held in the community of San Miguel de Motoy, Chiara district, Ayacucho department, Peru. Diponible: https://www.fredyhuamanmallqui.com/wawa-pampay-infants-funeral.html (accessed on 5 May 2025). Note. Source: Fredy Huamán (2007). Wawa Pampay (Baby’s Funeral).

In various regions of the world, children’s funerary rituals may be associated with practices of sacrifice and agricultural fertility—“Ideology of child sacrifice present in the region. Rituals often associated with agriculture and harvest” (Crandall et al. 2012, p. 3). In contrast, the Andean community of Magnupampa has developed a different understanding of child death, viewing it not as a sacrifice but rather as a natural event caused by illness or accident. One of the study participants recalls the funeral of a child as follows: “Watching the songs we were performing: ‘Goodbye, bid me farewell, now I am leaving; goodbye, bid me farewell, now I am moving away, wuayyyy!’ We kept vigil for only one day. If on this day the child died, we buried them the next.” This experience recounts how the community accompanies the burial with farewell songs, expressing the definitive departure of the child’s soul. The wake usually lasts one day, but if the death occurs during the day, the burial may take place at dawn the following day. It is a spiritual experience where sadness is transformed into a collective act of singing, remembrance, and transition.

In the village cemetery, deceased children are buried without a specific space; the place is communal, and the location is defined by local authorities according to the family. This practice is related to Amuedo’s (2015) observation: “in the case of infant burials, there is a clear separation from other subadults and adults, who are buried in cists with the same mortuary treatment” (p. 98). Thus, although infants received similar treatment to other groups, their burial in special cists indicates a symbolic or cultural differentiation. One interviewee comments the following: “When a child dies, I feel sad, but it is part of the tradition and that is why we dance at children’s funerals. We cannot oppose it because visitors like to see this type of activity.” This response reveals a tension between the feeling of sadness and the need to maintain a traditional ritual that also serves as a cultural attraction.

There is a persistent tension between preserving ancestral customs and modifying those that retain ancient components now disconnected from the present context. “It can be re-signified, dignified, and above all, made evident in the daily struggle of Indigenous peoples and peasant communities that resist the extractive model of accumulation and dispossession” (Alvira Briñez 2017). It emphasizes cultural resistance, identity revalorization, and community dignity in the face of extractivist dispossession, highlighting the daily struggle for social justice.

2.2. Participants’ Emotional Experience During the Ritual

During the data collection process, one resident expressed her emotional experience in relation to the child funeral ritual with the phrase “Tradicioniyku kara riqui,” which she defines as an ancient tradition of the people. Participation in the ritual of burying children has changed in recent times. In addition, participants noted that infant mortality is now rare, unlike in the past, when a lack of medical care for mothers was common. In this context, it is argued that “understanding the sequences of ritualized activities for these children can be significantly improved by taking diachronic data into account” (Wilson et al. 2013, p. 13323). Regarding ways of coping with the death of children, some residents mention the possibility of seeking professional help before joining in the festive ritual of mourning. However, one interviewee states the following: “Manan chayqa existirachu, ñuqallaykum,” which means that this type of care did not exist and still does not exist in rural areas.

Epidemics, according to the testimonies of adults, when vaccines did not yet exist and when many mothers rejected their use out of ignorance, were some of the most difficult periods in terms of infant mortality. Today, in most cases, this situation is remembered as an emotional experience from the past. In this context, it is noted that “demographic concentration and growth were reflected in certain changes in mortuary practices, as segregated areas for the burial of the deceased appeared in the case of two cemeteries” (Seldes 2015, p. 96). Regarding the ritual of the children’s wake, one interviewee said the following: “We kept vigil on the day of death drinking cane liquor and also until the fifth day. There was no ritual.” According to this witness, the wake consisted of drinking pure cane during the day of death and also on the fifth day; no other special rituals were performed, as this was the traditional way of accompanying the bereaved.

The structural transformation of Andean tradition has gradually changed certain cultural practices that shaped community identity. This transition is evident in the following testimony: “In the 1980s, children were dying from epidemics, and we buried them while dancing with harps and violins. Now children no longer die, and we no longer practice our tradition. I don’t remember well, but I think we just buried them anywhere, dressed in their white robes, because of the epidemic pe chay sarrampion nisqampas kara riqui, which killed more children. Now they bury the dead just like that, so we bury them that way too. Recently, a child died of leukemia. I think he was 13 years old. He was the butler’s son. When I went there, they buried him with great sorrow. Others say that the boss punished him. I don’t know if that’s true or not.” This account highlights the transition from a time characterized by high infant mortality and collective rites accompanied by traditional music to a present in which deaths are less frequent, rituals tend to fade, and beliefs in divine punishment or tragic destiny still persist. This perspective emerges from interviews and participant observation at a recent funeral of an adolescent who died of natural causes, where parents and attendees faced dilemmas between rituals of celebration and those of mourning. See Supplementary Materials.

In various cultures around the world, children were selected as ritual offerings. This study analyzes how each Andean community conducts the burial of its deceased children, a practice traditionally known as Wawa Pampay. This ceremony, considered representative and carrying festive overtones, even included special invitations for its performance. Unlike other contexts, in which “children were selected for sacrifice because of their purity and were offered by their parents or specifically chosen by religious authorities” (Kawchuk 2019, p. 3), the Andean Wawa Pampay corresponds to natural or accidental deaths and is expressed through a distinctive burial with its own special ritual, bearing no relation to sacrifice.

By contrast, one testimony reveals the following: “When babies died, the custom was to carry the coffin from the house to the cemetery, singing, dancing, and drinking. They dressed the child in white clothes, and this custom was observed everywhere. When my daughter, a one-and-a-half-year-old baby, died, we followed the same custom as my fellow villagers. The godfather came to my house and took care of organizing everything, and the godmother got white clothes for the burial. Then all my neighbors came to my house to accompany us in our mourning, and after the mourning we began to sing, dance, and drink. Losing a baby is painful, but at the same time it is a joy because my daughter went to heaven without any sin. She is my little angel who always watches over me and my wife”. This story highlights a communal ritual practice in which the mourning of a child is accompanied by music, dancing, and drinking. The loss is reframed: suffering is mitigated by the belief in the purity of the child’s soul and its direct passage to heaven.

2.3. Role of the Community in Providing Emotional Support to the Bereaved

The community and local authorities play an important role in supporting the bereaved family of a deceased infant. Their presence in the family’s home, regardless of economic status, is essential, as “the accumulation of individual but anonymous voices provides an outlet for the articulation of collective trauma and public mourning” (Yi 2023, p. 75). Multiple anonymous voices, when united, allow for the expression and release of shared pain, functioning as a channel to transform individual traumatic experiences into a collective testimony that makes social mourning visible and validates it. It is a way of compensating for emotional pain, as one testimony recounts: “The wake began when the deceased was already dressed in white and the attendees lit the candle and gathered with the bereaved, chewing coca and drinking liquor as a sign of respect and solidarity. At the cemetery, a farewell ceremony was held where attendees chewed coca, drank, and danced in honor of the deceased.”

At all wakes for children and adults in Andean communities, it is customary to toast with cane liquor—a pure cane distillate—smoke unfiltered cigarettes, and chew coca leaves. These products are usually donated by the godfather and visitors, which helps reduce burial costs and alleviate emotional pain. Another testimony states the following: “The babies in the village mostly died of measles. At the wake, all the neighbors, parents, and godparents were cheerful. They had a coffin made to bury the child. We all got together and sang the qarawis. We also danced and drank, and that’s how we spent the wakes. We accompanied the family all night until the burial, dancing and singing, and when it was time to return, we accompanied the family, dancing and drinking. The day after the burial, the children pass from earth to heaven, so when a baby dies, God rejoices in receiving someone without sin.” It is necessary to consider that “shared grief is not simply about recovering from loss, but is an opportunity to commit to life and to others with a clarity and depth that can only be achieved through suffering” (Venema et al. 2023, p. 2258).

The news of a death is communicated by the ringing of the village bell, whose sound varies depending on the case, prompting the population to wonder about the identity of the mourner and decide to visit them, always bringing something to help the grieving family. The testimony, mostly in Quechua, is narrated as follows by an interviewee: “When the sun was about to rise, we buried, or at 3 or 4 in the morning, with harp and violin that the godmother brought, you see, we danced with fish, even little children danced, tied with a belt until the earth was well leveled, you see, there were many kinds. We kept vigil all night, at dawn we buried, and then, on the fifth day, we did like with fruits. At night we buried the little children too; if a child died without eating, we buried with sadness. It seems the godparents worked, you see, we did it like that; when someone died on the main road, we buried right there, you see.” In general terms, this translates to the burial taking place at night and dancing until dawn, accompanied by a harp and violin hired especially for the occasion.

In Andean communities, public health care is limited, especially when it comes to mental health. Farmers, most of whom are Quechua speakers, hold ancestral beliefs about emotional pain. According to Abel et al. (2023), “a public health approach to grief care highlights the inadequacy of policies that focus exclusively on the provision of professional services, whether through state funding or the charitable sector” (p. 822). This approach shows that addressing grief from a public health perspective exposes the limitations of policies focused solely on professional services and highlights the need for more comprehensive and community-based strategies. One interviewee recounts the following: “Since I was little, I was afraid to participate in the traditions of the wawa pampay. Now I could participate, but that custom no longer exists because the butler’s son recently died and they buried him normally, like anywhere else.” The testimony reveals childhood fear of the Wawa Pampay and sadness at its disappearance, evidencing cultural changes in funeral practices.

Although modern science and mental health tend to view changes in ancestral customs negatively, these gradual processes are allowing for the incorporation of new ritual forms in both the burial of a child and the accompaniment of mourners. This is evidenced through participant observation and interviews conducted with grieving families, both in recent cases and in past experiences within their own family circles. In this context, “with stressful workloads and a professional culture that emphasizes emotional suppression, employees will often sacrifice their own needs to continue helping others” (Funk et al. 2018, p. 25). One interviewee recounts the following: “With qarawi and with dance, when that death occurred, we kept vigil and carried him, you see? Likewise, the compadre carried his sash in front, resting little by little while they carried him; in the patio they also danced a lot, they made the father and the mother dance so that they would not cry too much. Nowadays, those things no longer exist.” This testimony indicates that, to avoid the suffering of the parents of the deceased child, a dance was first organized, motivating the hope that they would have more children and that the dead child would bless them from heaven.

2.4. Ritual Components and Their Therapeutic Function

In the burial of children, particular attention is paid to Andean rituals passed down through generations in the Quechua language. These practices have a therapeutic component: “with children’s graves (rituals, markers, or topography), the role of age in funeral practices and the relative importance of funeral objects in their ritualized expression are highlighted” (Dubois 2012, p. 30). Children’s graves, through their rituals, location, or characteristics, reveal how age influences funeral practices and how associated objects play a significant role in their ritual expression. A father’s testimony notes the following: “The traditions of the Wawa Pampay used to be different. They buried their children with great joy, with harps and violins, and even sought out godparents so that they could buy or give them land, I think that’s how it was said. As I am only a son-in-law, I don’t know much about it, but that’s what my mother-in-law told me. My son is the one who died recently. He had leukemia, but we didn’t bury him that way. We just did it the way they normally do it now, so I don’t know how it was before.” This account contrasts the festive and ritualized Wawa Pampay of the past with current practices, influenced by cultural changes and personal experiences.

In Andean communities, cases of psychological problems resulting from the loss of a child are rarely addressed, a situation that also occurs in most families. It is essential to address this emotional problem in a different context, such as “the loss of a baby or a child after birth. The gap lies in the fact that, in this case, the grieving process is rarely or never addressed, and often becomes pathological” (Nel 2007, p. 1324). The loss of a baby or newborn child is often neglected in the grieving process. Moreover, a child is considered as such until puberty, since they have not yet attained citizenship, and it depends on each family how the burial is carried out under communal pressure. The ritual constitutes a form of family therapy in which the community participates, as described in an interview: “Velakuq kaniku tawa pichqampi achikiallnimpim pichqa punchawman riqui, yupaq kaniku wañukusqa punckawmanta.” It is a wake that culminates on the fifth day, helping the family cope with their emotional grief.

Community support through rituals plays a fundamental role in alleviating emotional pain, especially when neighbors from different communities actively participate, as it provides comfort and a sense that the soul of the deceased was more valued. However, “in most cases, healthcare professionals do not advise women on the emotional or spiritual aspects of the experience” (McIntyre et al. 2022, p. 1), which implies a lack of attention to key dimensions for comprehensive well-being and psychological recovery. The change in custom is interpreted as a positive transformation in the face of emotional pain, as reflected in an interview: “At the beginning it was fine, mama, now they already bury with orchestra music, those things of the child’s burial are no longer done, they have already been lost. Even the qarawi is now sung more at weddings and at the warmi qurlluy.” This account describes how, over time, the music and songs of sadness in Quechua disappeared during the farewell to a child.

In the Andean world, funeral rites are essential and reflect a view of life and death that integrates Christian faith with beliefs in mountain deities. In the past, it was customary to bury the dead underground, without concrete niches, and to dance on the grave as a form of therapy for the parents. This tradition has changed over time, although the idea persists that “during the funeral rite, the corpse still represents the living person, who has died but has not left” (Delgado Antolín 2005, p. 51). In this way, the corpse retains a symbolic value that prolongs the emotional and spiritual bond, delaying the feeling of definitive separation. One testimony states the following: “Wawachakuna wañuruptinqa cieloman rin riqui, chaymi kusisqa pampaqkaniku. Nuñaqku taytankunaqa waqaq kaniku, challmantaqa kusispa pampaqkaniku.” This account indicates that when a child dies, it is believed that he or she goes to heaven, which brings joy to the parents, who enthusiastically bury the child to alleviate their emotional pain.

2.5. Tensions and Continuities Between Ancestral Rituals and Current Religious Beliefs

In the community of Magnupampa, as in other Quechua-speaking Andean villages, the growth of various religious congregations has generated tensions around funeral rituals. In particular, the evangelical congregation, which lacks ritual practices in its burials, questions the ways in which Catholics express their grief. Generational change allows us to understand that “the funeral rites developed in their honor, their identity and family and social position, the acts celebrated in their memory, or the changes that may have occurred after their burial, both in the short and long term” (Chapa Brunet 2023, p. 135). These rites, together with the identity and social position of the deceased, as well as the commemorative acts and changes after the burial, reflect their cultural and social importance at different times. One testimony states the following: “Manan igualchu riki, wawachakunaqa manam quchapichu wañuqku, chami pampaq kaniku alegriawan, tusuykunawan. Hatun wañurptinqa llakim.” This statement highlights the great difference between the burial of an adult and that of a child, where joy and sadness intermingle.

Religious beliefs play a central role in the burial rituals of both children and adults. In this study, the focus is on the burial of children, who are considered by peasants to be little angels of God. The influence of modernity and commercial economic movements has gradually changed the meaning of ancestral rituals. In this context, “rituals and traditions are powerful and versatile devices that can both convey and generate meaning, and performative rituals, such as processions and customs” (Bowman 2006, p. 36). These rituals and traditions function as versatile tools capable of transmitting and creating meaning, reinforcing cultural identity and community cohesion through shared symbolic actions. One interviewee mentions the following: “There was a godfather and a godmother for the chicken meal, and also for all the visitors.” This reflects that, in the ritual, it is necessary to eat chicken broth offered by the godparents.

Quechua-speaking peasants assimilated the Christian religion in their own way, integrating it into their worldview and adopting syncretism as a way of life. In this context, interviewees believe that deceased children are free from sin, innocent, and very close to God. This belief gives rise to the use of white clothing, a symbol of purity and innocence. Likewise, a close relationship is maintained with Mother Earth, to whom the child’s body is entrusted through ancestral rituals: their body remains underground, while their soul or spirit rises to heaven as a sign of purity and absence of sin. For this reason, it is essential that children be baptized according to the Catholic religion before their death or, failing that, blessed by a believer when no priest is present. Otherwise, it is believed that their soul could remain in limbo, in darkness. According to the testimonies collected in the research, saving the souls of children is an essential act of faith and spiritual salvation.

The presence of new religious congregations and the influence of modernity are transforming ancestral rituals linked to the burial of children. This has generated tensions between families and residents who defend traditional beliefs, motivated by the deep-rooted identity of the peoples. In this sense, “although evangelization placed considerable emphasis on funeral practices and the treatment of the dead, the veneration of ancestors and the creation of historical memory extended beyond these practices” (Murphy and Boza Cuadros 2016, p. 63). Despite evangelization and its emphasis on funeral rituals and the care of the dead, the veneration of ancestors and the construction of historical memory transcended these limits, becoming integrated into broader cultural and community expressions. This practice was valued, as one interview points out: “Chay tradicioniyku kamptinqa mana llumpay llakipas kammanchu, qarawichaykunapas kanman riqui, kunan tiempopiqa manañam kamchu riqui, runakunaqa qunqarunku.” The ancestral tradition meant less sadness due to the particular forms of burial.

In an Andean community, characterized by its small population and simple organizational structure, attending funeral rituals is a moral obligation. Absence from these ceremonies is often interpreted as indifference to the emotional pain of the bereaved family and is considered a lack of communal reciprocity. The presence of the community offers relief to the bereaved, as “the physicality inherent in these practices raises questions related to the body and how it is understood and perceived by those participating in the ritual” (Chénier 2009, p. 28). Such rituals integrate symbolic and physical dimensions, inviting reflection on the experience and meaning of the body, as well as its cultural and emotional significance. In the words of one interviewee, “Only we cried when our little child died; my husband, my brothers-in-law, and also our neighbors came to visit us to console us, you see? There were no psychologists in those times,” reflecting the resilience of families and communities without the intervention of mental health professionals.

3. Discussion

The “Wawa Pampay” ceremony constitutes a social phenomenon and an Andean practice that reflects the emotional and social consequences of infant death within the community. Various studies on the death of newborns or young children show that, depending on the community, such events are not considered an individual tragedy; rather, they are phenomena with social, spiritual, and emotional dimensions (Alberdi Vallejo 2010). The infant ritual, which includes symbolic baptism, the purification of the child’s soul, and Christian prayers, reflects a syncretism between Andean and Christian traditions. According to testimonies from community members who have witnessed and experienced the loss of their children, in some situations—when the child is of preschool age and has not been baptized—it is possible to perform an immediate baptism with a local religious figure during the illness, with the purpose of saving the child’s soul and ensuring its passage to a celestial life.

Rituals around the world present diverse ways of coping with grief, and in many cases they include practices that differ considerably from Andean traditions. As Crandall et al. (2012) note, some cultures even incorporate child sacrifice into their rituals, highlighting significant differences between traditions. In the case of this study, the ritual focuses on children who have died from incurable illnesses or accidents, according to the testimonies of the participants. Many community members refer to these children as “God’s little angels” and bury them with white garments, a symbol of childhood purity. These children are considered “the clearest link between this world and the other” (García Miranda and Leiva Ochoa 2019). The ritual functions as a spiritual mediation, in which death is mourned but also ritualized in a joyful manner in the Andes, involving the entire community. In this way, it becomes a structured process of emotional transformation that integrates cultural, spiritual, and social dimensions.

The research was based on testimonies and participant observation by the researchers during their childhood, which allowed them to gain an in-depth understanding of the Quechua culture and language. The presence of musicians is essential in the ritual, as Quechua songs, such as the “qarawi,” serve a healing function, according to the testimonies. These songs have their own narrative, specifically adapted for the infant burials of the “Wawa Pampay.” The musical ritual creates a special space during the children’s funerals, as noted by Montoya (1996). Furthermore, during the Wawa Pampay, musical elements such as jarahuis and taquis, performed to the rhythm of the harp and violin, accompany the wake, transforming grief into a collective expression and providing emotional catharsis (Cavero Carrasco 1985). In this way, the ritual functions as a community-based therapy that helps parents cope with the loss of their child, integrating the cultural, emotional, and social dimensions of mourning.

The burial of deceased children, known in Quechua as Wawa Pampay, is an ancestral tradition and a special ceremony, which is even recreated in theatrical performances and in cinema. In this practice, feelings of sorrow and joy are expressed within the community: “because there is a belief that she dies like a little angel without sin. The wawa pampay (burial of the infant) is performed with qarawis, huayno songs, and the deceased child is adorned with many flowers” (Velapatiño Marca 2019). The community celebrates the purity of the child’s soul, and her death inspires songs, flowers, and rituals that symbolize innocence and divine return. This ceremony is performed in different Andean regions of Peru and still persists in the high Andean villages, where ancestral rituals are maintained.

There are mixed feelings among community members regarding the ritual of children’s burial. Some consider it a custom that helps parents cope with grief, while others believe it would be necessary to involve mental health professionals to support the bereaved. In remote communities, where such professionals are unavailable, Quechua-speaking farmers place more trust in their traditions than in conventional medicine. It is important to consider both individual trauma and collective support in the grieving process, as Yi (2023) notes, especially in the context of infant death. The research takes into account both the existing literature and the testimonies of community social actors, as well as the experiences of the oldest community members, to understand the relevance and effectiveness of the ritual in facilitating emotional transformation during mourning.

4. Conclusions

In the Andean communities of Peru, especially among Quechua-speaking adults who are mostly illiterate, there is a lingering nostalgia for the joyful ritual of burying children. This act is remembered with fondness as a way of passing on to new generations how to emotionally cope with the loss of a loved one, especially a child. In the absence of mental health care, the participation of the entire community was essential to coping with the crisis. Over time, child funeral rituals have undergone changes, and today, child deaths are rare thanks to the availability of vaccines and medicines for newborns, resources that did not exist at the time when most of the interviewees in this research were still alive.

The relevance of this study lies in the scarcity of systematic research on the Wawa Pampay ritual, an ancestral Quechua tradition. Elements such as the use of white clothing, special flowers, preparations for the transfer to the cemetery, the wake, the fifth day, the dance, the music, and the qarawi (a sad farewell song in Quechua) have gradually lost their rigor. Access to modern information and the professionalization of many residents have driven a shift toward more modern burials, similar to those of adults, with only the use of white clothing throughout the ritual process remaining. Most of the interviewees, who spoke mainly in Quechua, agree that mutual aid is essential in the community, regardless of economic power, cultural level, or religious beliefs. Although there are discrepancies between Catholics and Evangelicals, both denominations coexist in the community, offering courtesy visits to the mourners even when they do not share certain aspects of the ritual, especially the consumption of cane—an alcoholic derivative—and the chewing of coca, practices that are indispensable in Catholic wakes.

The ancestral beliefs of the farmers of the Peruvian Andes condition their interaction with outside professionals, especially when the latter do not speak Quechua or understand the local worldview, which is based on a harmonious relationship with nature. In this cultural context, illness and misfortune are often interpreted as divine punishment from the Earth. The lack of systematized information on these practices and beliefs reveals the need for ethnographic work that, through prolonged coexistence with Quechua-speaking communities, allows for the recording and preservation of their rituals, preventing their disappearance into historical anonymity. The intergenerational transmission of knowledge is crucial, as younger generations are unaware of traditional funeral practices, in which infant mortality was a recurring event due to limited state medical coverage. Among the main limitations of this study are the lack of systematized records on child burial rituals, as well as the progressive disappearance of the social actors who lived through these experiences, resulting in the loss of a valuable cultural and emotional heritage linked to mourning the loss of a child.

In Andean communities, the emotional pain following the loss of a child does not end with the closing of the wake. When the mourners leave, each family returns to their home, often located miles away, in the middle of an open landscape where houses are scattered according to the rhythm of agricultural life. In this silence, mourning becomes an intimate experience, sustained by memory, belief, and community strength. For many families, the arrival of a child was the result of long waits and difficulties, and their departure, often caused by epidemics or untreated illnesses, left a wound that time cannot heal. The testimonies of survivors from past eras reveal a history of shared losses, learned resignation, and rituals that have accompanied grief for generations.

In the most remote areas of the city, the lack of access to medical or psychological information reinforces supernatural beliefs and ritual practices that remain almost intact, passed down from generation to generation as a way of making sense of death. Documenting these experiences and living alongside Quechua-speaking communities not only allow us to understand how they cope with grief but also preserve a cultural heritage that, without documentation, risks being lost in the anonymity of history.

5. Materials and Methods

This research was conducted using a qualitative approach, employing ethnographic methods to understand the cultural significance of the child burial ritual (Wawa Pampay) in Quechua-speaking communities in the Peruvian highlands. The fieldwork was carried out in the community of Magnupampa itself, alternating between extended stays in the community and periodic visits to families, in order to observe and participate in ritual practices related to mourning.

In-depth interviews and open conversations were conducted with elders, parents, and community leaders, favoring the Quechua language as the primary means of communication to ensure the authenticity of the stories and the trust of the participants. Participant observation was a key technique, allowing us to document not only the visible actions during the rituals but also the gestures, silences, and expressions that reveal the emotional and spiritual background of the practice.

The record was supplemented with detailed field notes, audio recordings, photographs (with prior authorization), and faithful transcriptions of testimonies, always ensuring respect for privacy and local beliefs. Data collection focused on capturing both verbal discourse and symbolic elements, with special attention to generational changes and adaptations of the ritual in response to declining infant mortality and the introduction of health services. The language used was limited to Quechua and Spanish, respecting the interference inherent in their communication.

In the Andes, the definition of a child or baby varies according to each family and community. In this context, a child is understood to be up to approximately twelve years old, although the ritual for an adolescent differs if they have not yet reached citizenship. During the funeral of an adolescent who died of natural causes, mixed feelings were observed: on one hand, the evocation of traditional forms of burial and their rituals; on the other, the current changes in the way mourners are accompanied. This setting served as a space for gathering information, in which one of the researchers—belonging to a generation that experienced the older rituals—recalled the presence of music, dances, jokes about “having another child right away,” and the conviction that the bereaved should not suffer but rather be accompanied by the entire community.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/rel16111462/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.G.-G. and Y.M.T.-Q.; methodology, R.C.G.-R.; software, S.B.M.-P.; validation, V.A.-A., Y.M.T.-Q. and G.P.-R.; formal analysis, E.G.-G.; investigation, Y.M.T.-Q.; resources, G.P.-R.; data curation, R.C.G.-R.; writing—original draft preparation, S.B.M.-P.; writing—review and editing, V.A.-A.; visualization, G.P.-R.; supervision, E.G.-G.; project administration, G.P.-R.; funding acquisition, E.G.-G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Funded by PROCIENCIA-CONCYTEC “Social Science Research Projects” CONTRACT No. PE501096666-2025-PROCIENCIA.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declara-tion of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of the National Autonomous University of Huanta (CERTIFICATE No. 001-2025/CEI-VPI-UNAH–HUANTA, 3 September 2025).” for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abel, Julian, Allan Kellehear, and Samar M. Aoun. 2023. Bereavement care reimagined. Annals of Palliative Medicine 12: 816–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberdi Vallejo, Alfredo. 2010. Wawa Pampay: Tanatología Infantil Quechua. Runa Yachachiy: Revista Electrónica Virtual. Available online: https://www.alberdi.de/wapamtacalb301010.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Alvira Briñez, Yamile. 2017. Resistencias andinas y “Buen Vivir/Vivir Bien” frente al extractivismo minero: Quimsacocha (Ecuador) y Conga (Perú). Revista de Estudos em Relações Interétnicas 20: 49–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amuedo, Claudia. 2015. Las vasijas y su potencial como sujetos estabilizadores de seres incompletos: Prácticas mortuorias de infantes durante el período tardío en el valle calchaquí norte. Estudios Atacameños 50: 85–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amuedo, Claudia Gabriela, and Liliana Vilte. 2019. El Cerro de la Virgen: Tramas de humanos y no-humanos en torno al culto mariano y a los cerros en el departamento de Cachi, Salta, Argentina. Antípoda. Revista de Antropología y Arqueología 37: 31–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade Ciudad, Luis, and Rosaleen Howard. 2021. Las lenguas quechuas en tres países andino-amazónicos: De las cifras a la acción ciudadana. Káñina 45: 7–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baby-Ramírez, Yousy, Edgar Gutiérrez-Gómez, Hubner Janampa-Patilla, and Sonia Beatríz Munaris-Parco. 2025. Sociocultural Context of the Yoruba Religion in Cuba: Cultural Legacy of the Transculturation Process. Millah: Journal of Religious Studies 24: 213–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balán, Jorge. 1996. Stealing a bride: Marriage customs, gender roles, and fertility transition in two peasant communities in Bolivia. Revista de Transición En Salud 6: 69–87. Available online: https://repositorio.cedes.org/handle/123456789/3282 (accessed on 4 May 2025).

- Bowman, Marion. 2006. Power play: Ritual rivalry and targeted tradition in Glastonbury. Scripta Instituti Donneriani Aboensis 19: 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavero Carrasco, Jesús Armando. 1985. El Qarawi y su función social. Allpanchis 25: 233–70. Available online: https://www.example.com/ALL025_Cavero_ELQarawi-web_menorT.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2025). [CrossRef]

- Chapa Brunet, Teresa. 2023. Muerte, ritos y tumbas: Una perspectiva arqueológica. Vínculos de Historia Revista del Departamento de Historia de la Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha 12: 125–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chénier, Ani. 2009. Bones, people and communities: Tensions between individual and corporate identities in secondary burial ritual. NEXUS: The Canadian Student Journal of Anthropology 21: 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crandall, John J., Debra L. Martin, and Jennifer L. Thompson. 2012. Evidence of Child Sacrifice at La Cueva de los Muertos Chiquitos (660–1430 AD). Landscapes of Violence 2: 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado Antolín, Juan Carlos. 2005. La fuerza terapéutica del rito funerario. Cultura de los Cuidados Revista de Enfermería y Humanidades 17: 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Dubois, Céline. 2012. Des objets pour les bébés ? Le dépôt de mobilier dans les sépultures d’enfants en bas âge du monde grec archaïque et classique. In L’enfant et la Mort Dans l’Antiquité III. Le Matériel Associé aux Tombes D’enfants. Edited by Antoine Hermary and Céline Dubois. Aix-en-Provence: Publications du Centre Camille Jullian, pp. 329–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funk, Laura M., Sheryl Peters, and Kerstin Stieber Roger. 2018. Caring about dying persons and their families: Interpretation, practice and emotional labour. Health & Social Care in the Community 26: 519–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Miranda, Elsa Cira, and E. Pompeyo Leiva Ochoa. 2019. Wawa pampay: Costumbres funerarias de niños en los Andes centrales del Perú. In XX Encuentro de Cementerios Patrimoniales: Los Cementerios Como Recurso Natural, Turístico y Educativo. Málaga: Comité Español de Historia del Arte. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=7952207 (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Gutiérrez-Gómez, Edgar, Jesús Wiliam Huanca-Arohuanca, Ketty Marilú Moscoso-Paucarchuco, Manuel Abraham Paz y Miño-Conde, and Diana Luján-Pérez. 2023. The Evangelical Church as an Extirpator of Idolatry in the Water Festival in the Andes of Peru. Religions 14: 965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Gómez, Edgar, Ketty Marilú Moscoso-Paucarchuco, Diana Luján-Pérez, Jaime Carmelo Aspur-Barrientos, and Eugenia Rocío Quispe-Medina. 2024. The native potato, a symbol of macho expression in the Quechua culture of Peru. Frontiers in Sociology 8: 1268445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutiérrez Martínez, Juan B., and Claudio Rojas Porras. 2021. Territorialización del miedo e inseguridad en el distrito de Ayacucho. Antropología Experimental 20: 365–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huaman, Fredy. 2007. Wawa Pampay (Infant’s Funeral). Fredy Huaman Portfolio. Available online: https://www.fredyhuamanmallqui.com/wawa-pampay-infants-funeral.html (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Kawchuk, Olenka. 2019. Children of Heaven. USURJ: University of Saskatchewan Undergraduate Research Journal 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leoni, Juan B. 2005. La veneración de montañas en los andes preincaicos: El caso de ñawinpukyo (ayacucho, perú) en el período intermedio temprano. Chungará 37: 151–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntyre, Lynne, Bruna Alvarez, and Diana Marre. 2022. “I Want to Bury It, Will You Join Me?”: The Use of Ritual in Prenatal Loss among Women in Catalonia, Spain in the Early 21st Century. Religions 13: 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millett, Martin, and Rebecca Gowland. 2015. Infant and Child Burial Rites in Roman Britain: A Study from East Yorkshire. Britannia 46: 171–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoya, Rodrigo. 1996. Música chicha: Cambios de la canción andina quechua en el Perú. Cosmología y Música en los Andes 55: 483–96. Available online: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/304707932.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Murphy, Melissa Seldes, and María Fernanda Boza Cuadros. 2016. Convirtiendo a los vivos, disputando a los muertos: Evangelización, identidad y los ancestros. Boletín de Arqueología PUCP 21: 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Nel, Johan. 2007. Pre-natale sterfte en ritueel: Die behoefte aan ’n betekenisvolle ritueel in die hantering van ’n miskraam of aborsie. HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 63: 1319–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seldes, Verónica. 2015. El transcurrir del tiempo y las prácticas mortuorias: Quebrada de Humahuaca (Jujuy, Argentina). Revista Española de Antropología Americana 44: 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velapatiño Marca, Ramiro, dir. 2019. Wawa Pampay [Documental]. Ñawinchik. Available online: https://centrocultural.pucp.edu.pe/cine/item/2758-wawa-pampay.html (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Venema, Marnie, Derrick Klaassen, Janelle Kwee, and Larissa Rossen. 2023. Grieving in community: Accompanying bereaved parents. Journal of Community Psychology 51: 2246–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, Andrew S., Emma L. Brown, Chiara Villa, Niels Lynnerup, Andrew Healey, María Constanza Ceruti, Johan Reinhard, Carlos H. Previgliano, Facundo Arias Araoz, Josefina Gonzalez Diez, and et al. 2013. Archaeological, radiological, and biological evidence offer insight into Inca child sacrifice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 110: 13322–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, Ivanna Sang Een. 2023. Communal Mourning and Contemporary Elegy in Korean Poetry: Kim Hyesoon’s Autobiography of Death. Journal of World Literature 8: 62–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).