Abstract

Daoist robes in the Ming Dynasty literature underwent a marked transformation from exclusive religious vestments to widespread secular attire. Originally confined to Daoist priests and sacred rites, these garments began to appear in everyday work, entertainment, and ceremonies across social strata. Drawing on a hand-coded corpus of novels that yields robe related passages, and by analyzing textual references from Ming novels, Daoist canonical works, and visual artifacts, and applying clothing psychology and semiotic theory, this study elucidates how Daoist robes were re-coded as secular fashion symbols. For example, scholar-officials donned Daoist robes to convey moral prestige, laborers adopted them to signal upward mobility, and merchants donned them to impersonate the educated elite for commercial gain. By integrating close textual reading with cultural theory, the article advances a three-stage model, sacred uniform, ritual costume, and secular fashion, that clarifies the semantic flow of Daoist robes. In weddings and funerals, many commoners flaunted Daoist robes despite sumptuary laws, using them to assert honor and status. These adaptations reflect both the erosion of Daoist institutional authority and the dynamic process of identity construction through dress in late Ming society. Our interdisciplinary analysis highlights an East Asian perspective on the interaction of religion and fashion, offering historical insight into the interplay between religious symbolism and sociocultural identity formation.

1. Introduction

Daoism, founded in ancient China with canonical texts such as Laozi’s ‘Dao De Jing’道德經 and Zhuangzi’s ‘Zhuangzi’莊子, has had a profound influence on global religious culture. The fluidity of Daoist symbols provides a lens to study interactions between religion and society (). Within Daoist culture, the Daoist robe is a tangible sign of the faith’s integration into daily life. Compared to intangible doctrines, these garments reflect how Daoist ideals permeated secular realms during the mid-to-late Ming Dynasty (1368–1644). At the same time, the shifting meanings of Daoist robes mirror broader changes in social customs, status, and cultural belonging.

In the early Ming period, Emperor Zhu Yuanzhang’s patronage stabilized Daoism; however, rising prosperity gradually enlightened public values, emphasizing fame and wealth above classic learning. Daoist robes, once the exclusive attire of priests, were also adopted by scholar officials, the empire’s most esteemed class. As a result, the robe’s usage spread beyond religious contexts into secular society (). Notably, Ming legal codes such as the Ming Shi·Yufu Zhi (明史·輿服志, History of Ming, Treatise on Ceremonial Dress) strictly reserved Daoist robes for priests, yet popular novels of the time frequently depict scholars, merchants, and even commoners wearing them. This apparent contradiction invites the question: how did a tightly regulated religious garment become a cross-class symbol of status?

Scholars have offered divergent explanations for this phenomenon. Some see it as evidence of declining religious authority in late imperial China (), whereas others regard it as a form of adaptive resilience that allowed Daoism to stay relevant during social change (). Yet most research on religion and dress focus on European Christian contexts, leaving East Asian mechanisms underexamined. Literary texts in the original vernacular, in particular, provide abundant, but under-used, material on the secularization of religious symbols. This study addresses that gap by asking, how did the Daoist robe transcend religious discipline and legal restrictions to become a cross-class tool for identity negotiation in Ming China? Drawing on symbolic interactionism (), we argue that Daoist robes were re-coded via social processes. As laypeople appropriated the garment, they shifted its meaning from purely religious authority to secular prestige and social identity. Secularizing Daoist dress was therefore a bottom-up process of social re-definition. The sections that follow describe our materials and methods, present findings from the textual analysis, interpret the results in relation to existing theories, and conclude with the study’s contributions.

2. Materials and Methods

This study is based on an interdisciplinary, qualitative, textual, and material analysis of Ming Dynasty sources. This study follows three criteria when choosing novels. First, to keep the research rigorous and the content true to Ming dynasty society, only works written in the Ming period and set in the Ming period are included; novels published in that period but telling other dynastic stories, or books from later times that merely describe the Ming, are left out. Second, the words “Daoist robe” (道袍daopao) or “Daoist garment” (道衣daoyi) must appear at least ten times, and the wearers should represent a reasonably full range of social classes. Third, each chosen text must have a well-edited, reliable edition so that citations can be made with precision. The primary corpus consists of ten novels, including Xingshi Yinyuan Zhuan醒世姻緣傳, Xingshi Hengyan醒世恆言, Yushi Mingyan喻世明言, and Erke Pai’an Jingqi二刻拍案驚奇. We examined 10 novels from the Ming period that depict Daoist robes in various social contexts. We also consulted Daoist canonical writings (e.g., Dao De Jing, ritual manuals) and visual materials such as paintings and surviving artifacts of Daoist attire.

Corpus curation and coding. Each novel mentioned “Daoist robe”, “head-scarf”, “gauze cap” and related terms were manually extracted. For every passage we recorded wearer identity, social setting, like ritual, leisure, cross-class impersonation, etc., and narrative function. Coding followed a three-tier scheme, “sacred uniform”, “ritual costume”, and “secular fashion”, that emerged inductively during close reading.

In our analysis, the theoretical framework integrates clothing social psychology and semiotics. In particular, symbolic interaction theory () informed how meanings of Daoist robes are co-constructed through social interaction. We also drew on the concept of cultural capital (), as mediated by clothing (), to understand how material attributes of dress demarcate status. Goffman’s theory of social performance () provides an additional lens to interpret robe-wearing as revealing an identity. This interdisciplinary approach allowed us to trace both the semiotic shifts and the social dynamics surrounding Daoist dress.

This combined qualitative text analysis informed by social theory, enabled us to uncover how Daoist robes transitioned from sacred symbols to secular emblems across Ming society.

3. Results

The religious symbolic meaning of Daoist robes in the Ming Dynasty was gradually dissolved by secular practice, and their form, color, and function underwent fundamental changes in symbolic meaning. The Daoist robe is rooted in Daoism (). As a religious system, Daoist doctrine, grounded in the maxim dao fa ziran (道法自然, the Way follows Nature), extols harmony between humans and the cosmos (). In the early Ming, however, Emperor Zhu Yuanzhang strategically paired strict registration of ordained priests, with Daoist robes reserved for those holding a state-issued file and selective bestowal of Daoist robes on meritorious officials and degree holders. This policy sacral licensing on the one hand, imperial gifting on the other, invested the garment with both spiritual legitimacy and courtly favor. Consequently, a Daoist robe quickly became a portable credential of prestige, coveted by anyone seeking enhanced respect in late-Ming society.

Meanwhile, the economic development of the Ming Dynasty gradually enlightened the minds of the common people, and the pursuit of fame and fortune gradually replaced the traditional society’s pursuit of knowledge. It was precisely because the Daoist robe was the attire of scholars in the Ming Dynasty and this group was highly respected and held the highest social status in the Ming society that the wearing of the Daoist robe became increasingly popular. Daoism was able to penetrate more deeply into the folk clothing culture of the Ming Dynasty, interact and influence with social culture and folk concepts, and ultimately expound the secularization trend of Daoism. In the novels of the Ming Dynasty, there were many reactions to the secularization of Daoism, mainly reflected in the use of clothing symbols.

Also, under the Da Ming Huidian大明會典, only clerics who had received an official file and were recorded by the Bureau of Daoist Register were entitled to wear the blue robe. The Bureau subordinate to the Ministry of Rites, compiled rosters to inspect. Laymen found “usurping Daoist dress” were to be fined or caned. In practice, however, by the late Wanli 萬曆reign, enforcement had largely devolved into commutable silver penalties, creating the legal and actual gap that late Ming novels exploit.

3.1. Religious Semantic Deconstruction: Breakdown of Traditional Forms

In the process of Daoism’s secularization during the Ming and Qing dynasties, deities that were highly regarded and relatively popular in folk beliefs were first incorporated into the Daoist pantheon, thereby winning the faith of the populace (). At the same time, Daoism ceased to be a lofty religion, walled off from lay society, merged into the folk sphere and became part of popular customs.

Records in Ming dynasty novels show that the Daoist robe, a traditional religious garment, underwent a complex reconstruction of meaning. Originally, the robe was worn exclusively by Daoist priests during rituals, symbolizing sacred religious authority (). Yet as society changed and secular forces intervened, its religious connotations were gradually diluted and absorbed into a broader social and cultural setting. This section traces the shift from sacred to secular, analyzing how the robe’s traditional form was dismantled, and its symbolic meaning recoded.

During the Ming period, the fundamentally religious symbolism of Daoist robes was gradually eroded by secular practice. Originally, Daoist attire was deeply rooted in Daoist cosmology, as Chapter 51 of the Dao De Jing states, “the Way ‘Dao’ gives birth to all things, virtue preserves them” (Laozi). By implication, only virtuous people should wear robes, and the robe itself symbolized lofty Daoist authority and detachment from the mundane. This is reflected in Ming legal sources, the Ming Hui Dian (明會典, Collected Statutes) stipulates that “Daoists’ everyday dress is blue,” linking the color blue to ritual propriety. Scholars and priests were thus expected to don blue robes as a mark of sanctity. In the first stage, the Daoist robe was tightly regulated by the ritual system and worn solely as liturgical attire when priests conducted ceremonies. Daoist canons state that a priest may not enter the altar or preside over sacrifices unless he first puts on the robe, underscoring both his elevated status and the ceremony’s solemnity. At this point, the robe served mainly as a marker of identity and a form of sacred protection, while its loose, flowing cut intensified the rite’s dignified atmosphere. In short, its meaning was confined to the religious sphere and closely tied to Daoism’s internal hierarchy.

However, late Ming novels show that such strict norms were breaking down. Besides scholars and Daoist clergy, some well-off farmers, merchants, and even craftsmen also began to wear Daoist robes, showing that their use was no longer limited to the groups named in the law. Tong Qi童七, the black silver smith in Xingshi Yinyuan Zhuan, inherited his father’s trade. By mixing ordinary metals with copper and selling them as pure patterned silver, the family gained both wealth and a good name in the capital. At first Tong Qi was just an apprentice living as a simple artisan, but as the business prospered, his clothes changed. He no longer wore the coarse work gear of a smith; instead, he chose finer, more elegant garments to show his wealth. When meeting officials, he would “put on a plain satin cap, a sky blue crepe Daoist robe, silk stockings, and felt shoes” ( Chapter 36). Such an outfit was refined and eye catching. The robe’s light crepe fabric was quite different from the tough, easy-to-clean hemp clothes needed at the forge. Thus, in the second stage, the Daoist robe gradually moved out of the purely religious sphere and became ceremonial dress for specific formal occasions in secular society. This shift reflects the penetration of religious symbols into everyday life.

In popular fiction, Daoist robes no longer signaled only priestly status, and they increasingly appeared on common folk. Moreover, officials were also known to wear Daoist robes in non-official settings, suggesting their symbolic resonance extended beyond institutional boundaries (Figure 1). These ordinary townsfolk were mostly lay people with a measure of cultural or financial capital. They wore Daoist robes to weddings, funerals, and other ceremonial gatherings, using ritual dress to win respect and signal status. For example, Chapter 3 of Xingshi Yinyuan Zhuan records that Chao Yuan晁源, the son of a local official, donned a “lychee-red Dashu-Meiyang satin Daoist robe ” 荔枝紅大樹楊緞道 when he went to a temple to burn incense, treating it as formal attire for seeking blessings (). People at the time generally believed that clothing was not only practical but could also elevate a wearer’s morals and fortunes. For weddings, funerals, ancestral rites, or visits to temples, proper dress was therefore expected. Motivated by this mindset, Chao Yuan chose to copy a Daoist look, donning a Daoist robe when entering the incense hall. On one level, he borrowed the robe’s religious authority and air of purity to show he was no ordinary worshipper; on another, the robe had already become an elite form of ceremonial wear in secular eyes, signaling his respect for ritual and his social standing. Thus, the act met two aims at once, securing divine protection and maintaining worldly dignity, illustrating the robe’s dual value in the second stage, as a vestige of religious sanctity and a badge of secular prestige.

Figure 1.

A Ministry of War official wearing a Daoist robe, as depicted in a Ming dynasty novel.

Although the setting was religious, the wearer was not a priest. Likewise, Chapter 9 describes him, deep in mourning, attending a funeral in a white Daoist robe. The robe’s color matches the somber mood and shows how commoners borrowed it to add gravity to a burial. This scene indicates that the robe’s sacred meaning had migrated into secular funerary rites, the use of white fits traditional mourning customs, yet, worn by a non-priest, it redefines the robe’s sacred authority as a sign of social standing and moral worth. At this point, the robe still preserved ritual dignity while gaining new uses in secular life, becoming a symbol through which laymen displayed education and rank.

By the third stage, the Daoist robe gained yet another secular meaning, it became a fashion item worn across all social classes in the mid-to-late Ming. Ye Mengzhu葉夢珠’s Yueshi Bian閱世編 records, “In earlier times, public and private dress had long hems and close-fitting sleeves, scarcely a foot wide, later, garments grew shorter while the sleeves grew ever larger”. According to Yunjian jumuchao雲間據目抄, young scholars in Jiangnan “always wore light-red Daoist robes”, and even yamen runners copied this look to show status. The robe kept its basic features, a straight collar that crossed to the right, wide sleeves gathered at the cuff, and side slits with hidden gussets, but fashion lay in the details, above all the exaggerated sleeves. In early Ming, sleeves were about one chi (≈33 cm) wide, by Wanli (萬曆) they had expanded to over three chi, so wide that when one folded one’s hands the sleeve bottoms brushed the boots. Feng Menglong馮夢龍’s notes say that stylish youths near the dynasty’s end loved wide-sleeved robes and would team a white silk tunic with peach-pink trousers for show. This bold cut became a hallmark of rebellious style (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The Shandong Museum houses a tea-brown Daoist robe brocaded with gold dragon motifs; its gilt-thread dragons highlight opulence and reveal a fashion mentality that dared to overstep sumptuary rules. (Shandong Museum).

Materials and colors also broke new ground. Although the state banned commoners from wearing yellow or purple, vivid shades such as bright red, oil green, and silver red were fashionable in practice. Some even mixed Korean paper for the outer layer with red Hangzhou silk for the lining, creating striking contrasts.

Meanwhile, novels often show young men treating the Daoist robe as trendy casual wear. Xingshi Yinyuan Zhuan gives a similar picture. In Chapter 14 a county bailiff “wore an old blue-silk Daoist robe,” showing that it had become part of everyday dress. The robe’s style and color had grown secular, worn daily by scholars, proving it was no longer limited to sacred rites. Its former sanctity had been softened by popular taste. Yet the popularization of Daoist robes did not erase clerical distinctiveness altogether. Ming ritual manuals stipulate a tripartite vestimentary hierarchy of daily dress, ritual vestment to be worn only when audiencing the gods. This internal re-stratification shows that, as lay imitation spread, priests responded by upgrading liturgical garments rich in talismanic motifs, thereby reasserting professional authority. While their overall social prestige did decline, their exclusive ritual expertise still secured their indispensability.

Chapter 3 also portrays Chao Yuan dressing for a banquet—besides the robe, he adds lavish ornaments, flaunting his wealth. Bright colors and fine fabrics had fully broken with the robe’s plain religious look and entered the realm of secular fashion. As taste in clothing became a tool for marking social strata, the robe’s evolution reflected a new definition of status symbols. Once a token of clerical merit, it now signified elegance, wealth, or trendiness. Its popularity also shows the loosening of traditional dress codes, as a garment once reserved for priests was copied and reinterpreted by the public. In late Ming China, clothing increasingly signaled social and even political position, and rich merchants, able to spend freely, challenged sumptuary rules. The vogue for Daoist robes epitomizes this change, marking the absorption of religious symbols into secular fashion and the shift in cultural power from sacred to worldly. From clerical uniform to streetwear, the robe’s meaning shed its sacred aura and was recast, bearing witness to struggles over identity and the evolving cultural psyche of the period.

Overall, the body functions as the key axis for expressing the Daoist belief system (), and the garments covering the body become its external vehicle, imbuing them with human-centered autonomy that can even transcend their original religious purpose. In Xingshi Yin Yuan Zhuan and Xingshi Heng Yan, entertainers, merchants, and peasants of lower social rank are described as wearing fine Daoist robes when visiting friends or attending funerals. These individuals often selected robes of high quality material and bright colors. Rather than facing punishment for violating sumptuary laws, they gained respect and prestige, and guests who received a visitation wearing fine Daoist robes would feel honored by their hosts. And the prevalence of lay Daoist robe does not point to wholesale legal collapse, but to the gap between symbolic statutes and pragmatic local governance.

This diffusion indicates that Ming society became more tolerant of non-priests wearing Daoist dress. The robe’s stylistic language itself evolved: it lengthened, widened, and developed more elaborate patterns, yet remained fundamentally the same garment. What changed was its symbolic meaning. The robe was no longer reserved to denote a Daoist’s inner cultivation; it became a widely borrowed symbol used to display status. In effect, the robe’s original “sacred” meaning was deconstructed. It was now reinterpreted through broader social interactions, rather than remaining an immutable marker of religious authority. At the same time, late Ming fiction often depicts Daoists cheating people out of money or having illicit affairs with priestesses. Although these stories are not necessarily historical fact, they serve as the authors’ cultural commentary on the Daoists’ public image. In official temples and grand rituals, Daoists still held ritual authority, but in folk narratives they were sometimes mocked as profit seekers. Thus, the novels provide a double perspective, they show popular approval of religious symbols while also reflecting secular doubts and satire about Daoists’ moral integrity.

In sum, during this initial stage, the Daoist robe served as a clear marker of religious authority and institutional purity. Its meaning was closely guarded within ritual boundaries, reinforcing the symbolic distinction between the sacred priesthood and the secular world.

3.2. Secular Function Reconstruction: From Transcendent to Worldly

Through symbolic interaction, Daoist robes acquired new secular functions. Daoist philosophy stresses transcendence of worldly cares and pursuit of inner stillness. Traditionally, a person wearing Daoist garments would implicitly affirm commitment to these ideals. However, by the mid Ming period, novels show the robe’s use largely detached from literal Daoist faith. It became integrated into everyday social life and rituals, affecting both religious and secular domains.

For instance, among both elites and commoners, Daoist robes began appearing in marriages, funerals, and other ceremonies. Wealthy commoners and laborers wore robes to upwardly mobile social events, even if they had no Daoist beliefs. These occasions often involved exchange of gifts or favors. A common practice was for one family to present a valuable Daoist robe to another, implicitly creating an obligation of reciprocity. In this gift economy, the robe became a social currency. If a bridegroom presented a robe, for example, the recipient would feel honored and socially indebted. Thus, wearing a Daoist robe became a performative act, not for deity worship, but to craft an identity recognized by others. In Blumer’s terms, the robe’s meaning was dynamically reconstructed through these exchanges (). The novel Xingshi Yinyuan Zhuan describes, “an elderly white-bearded man in his seventies or eighties… wearing a half-new, half-old brown Daoist robe.” () This scene occurs at a wedding reception, where a wealthy elder merchant dons a Daoist robe to welcome the bride and groom, rather than performing rites in a temple. This demonstrates that appearing in a Daoist robe at a wedding is not only socially acceptable but even appropriate and formal. From the perspective of interaction theory, this exchange in the wedding context endows the robe with new symbolic meaning, it no longer serves solely as religious vestment but becomes a symbol of family blessing and social status. Likewise, the novel mentions that Chao Yuan “wore a Daoist robe” when receiving guests, further showing that in secular social settings the robe’s meaning has been recoded as ceremonial attire conveying worldly authority and dignity. Our readings show that this pattern repeated in funeral scenes. In one novel, mourners not closely related to the deceased commonly wore Daoist robes to the ceremony, treating the funeral as a social gathering where they presented themselves in dignified attire. The classic Book of Rites insists that rituals follow the cosmic order of yin and yang, emphasizing social harmony. In this spirit, Daoist robes at funerals symbolically aligned with Daoist principles of natural order, but functionally they served status claims, and lower-status guests used them to elevate their appearance and command respect.

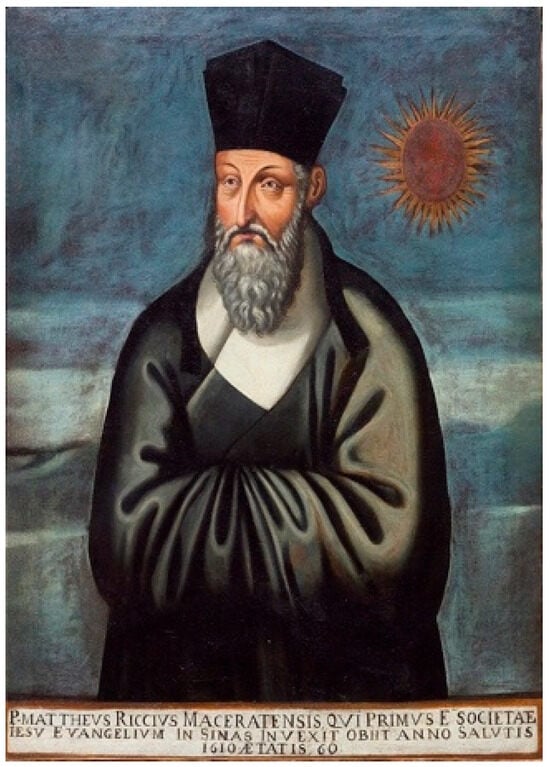

Moreover, traditional narratives often feature the Daoist robe as a gift, which further strengthens its secular role. Presenting the robe as part of reciprocal etiquette shows that people treat it as an auspicious token for blessings and longevity. In such exchanges, the robe enters a new interpersonal context and is repeatedly assigned worldly meanings of friendship and goodwill. A notable example beyond fiction is the famous image of Matteo Ricci wearing a Daoist robe, it is an act by which Catholic missionaries in late Ming China sought to appropriate local symbols of prestige and gain social legitimacy (Figure 3). Bourdieu notes that gift giving circulates cultural capital. Presenting an ornate robe is therefore not merely a material gesture, it also reinforces the giver’s social standing. Symbolic interactionism likewise suggests that, through gift exchange, the robe’s meaning is continually reworked, from a transcendent clerical garment to a social marker—thus recoding it from sacred to secular. In short, these secular scenes reveal how the robe is reinterpreted and used in social interaction, making it a composite symbol of ritual, sociability, and status.

Figure 3.

Portrait of Matteo Ricci, 1610 (Collection of the National Heritage Board, Singapore). The painting shows Matteo Ricci dressed in a Daoist robe, indicating The Catholic missionaries hoping to confer prestige in China.

In short, Daoist robes in Ming fiction became tools of social negotiation. People wore them to achieve practical ends, to signal respectability, to mark generosity, or to bridge class divides, rather than solely to express piety. The robe was fully enmeshed in everyday social rituals, blurring the line between religious garment and ceremonial costume.

Thus, in the second stage, the robe’s symbolism became more fluid and context dependent. Worn by laypeople in weddings, funerals, and gift exchanges, it evolved into a performative tool for negotiating status, virtue, and social respectability, blurring the line between religious sanctity and secular identity.

3.3. Fusion of Religious Representations: The Daoist Robe as Mediator of Inter-Religious Exchange

Late Ming novels even depict Daoist robes crossing into other religious contexts. Buddhist converts or monks are sometimes shown wearing Daoist-style robes. For example, in Chapter 3 of Xing Shi Yan (Reform of the World), a Buddhist temple gives new initiates Daoist robes to wear in the shrine, explicitly borrowing Daoist vestment symbols. Similarly, the coverlet of cloth offered to novices in Xingshi Yin Yuan Zhuan is a Daoist gown.

Ming dynasty storybooks often feature Daoist robes in non-Daoist settings, showing how the garment’s symbolism crossed boundaries and merged religious images. In Tian Couqiao天湊巧, the impoverished scholar Chen Duxian, brought low by hardship, “tied on a shabby square kerchief and threw on an iron-grey, worn cloth Daoist robe,” presenting himself in that outfit. Chuke Paian Jingqi初刻拍案驚奇likewise portrays a striking young man wearing an unusual Daoist cap, a “narrow-collared, wide-sleeved blue-velvet Daoist robe,” and red silk monk’s shoes, a mix of Daoist attire and Buddhist footwear. At folk ceremonies such as weddings, funerals, or ancestral rites, monks, Daoist priests, and laypeople could be seen swapping or combining ritual garments. During clan-hall sacrifices, for example, priests and monks might attend together and even exchange costumes, blurring once-clear religious boundaries. These scenes show that, in late-Ming society, the Daoist robe had moved beyond strictly liturgical use to become a symbolic garment adopted by many social groups.

This phenomenon can be understood through the religious market theory. In a pluralistic religious landscape, different traditions compete for adherents by attracting them with shared or prestigious symbols (). Daoism and Buddhism influenced each other, and priests of both faiths adapted to popular preferences. The Daoist robe thus became a medium of religious dialog. It shows Ming folk religion’s pragmatic integration, religious boundaries were porous, and practical concerns often overrode doctrinal purity.

The intertwining of religious garments across traditions can be further explained by drawing on religious-market theory and the theory of symbolic capital. Religious-market theory holds that in a “market” where several faiths coexist, each tradition, in order to win and attract followers, often borrows or shares one another’s symbols, creating a dynamic of competition and adaptation. As the literature shows, Ming dynasty novels frequently depict Buddhists wearing Daoist robes, suggesting that Buddhism adopted this symbol to suit believers’ tastes, an example of “pragmatic fusion” within the religious market. Meanwhile, Bourdieu’s theory of symbolic capital stresses that religious symbols carry not only spiritual meaning but can also be converted into vital resources for group rivalry and identity building (). From this angle, the Daoist robe’s sacred meaning gains social value, and different religious forces and social groups can wear it to earn respect and enhance authority. Thus, as a shared emblem that crosses religious lines, the robe acts as a “mediator” in religious interaction and negotiation, allowing wearers to draw on its symbolic power to gain prestige or status.

In summary, the robe’s symbolic process in Ming society shows a three-stage evolution. Initially, it was a distinctly sacred uniform restricted to ritual use. In the second stage, it became a borrowed attire for social ceremonies, imbuing its wearer with the aura of sanctity while also conveying secular identity. In the final stage, it transformed into a fashion statement shared across society, its sacred origins largely abstracted away. Each stage entailed a re-coding of meaning through social interaction, which we now discuss in relation to theory and scholarship. The Daoist robe, as a shared symbol, acted as a key link in the integration of folk religions during the Ming dynasty. By contrast, Buddhist monks usually wore dark kasaya or plain zhiduo, while the longevity robes used in birthday rituals were mostly red silk embroidered with the shòu壽 character and cranes. Although all three garments were wide-sleeved long robes, in practice they often borrowed each other’s patterns and ornaments, blurring the boundaries between religious dress. Thus, through the circulation and reinterpretation of shared clothing symbols such as the Daoist robe, Ming period society brought the visual expressions of Daoism, Buddhism, and even Confucianism closer together. This blending reflects the trend toward folk religious integration: by sharing dress symbols, people negotiated identity and belief, turning the Daoist robe into a cultural medium for cross boundary interaction.

In summary, the cross religious adoption of the Daoist robe not only collapsed the boundaries between Daoism and Buddhism but also catalyzed a new hybrid religious culture. The robe became a flexible symbol of shared spiritual capital, mediating both syncretic religious practices and the everyday construction of social identities in late Ming China.

4. Discussion

The present study demonstrates that Daoist ritual robes, originally confined to temple rites, evolved into secular symbols of status and identity across Ming society. As shown by Ming historical records, Daoist vestments were legally reserved for priests, yet contemporary novels are abounded with scenes of scholars, merchants, and even commoners donning these robes. This contrast motivates our analysis of how and why the robe’s meaning shifted from sacred to profane. We frame this transformation using a three-stage model of semantic change (Section 4.1), situating our findings in dialog with scholarship on religious dress and fashion (Section 4.2). Finally, we highlight the study’s original contributions, methodological insights, and broader implications before concluding the discussion.

4.1. From Religious Uniform to Secular Symbol: A Three-Stage Evolution

Daoism values “nothingness,” yet the popular use of Daoist robes recorded in Ming-dynasty novels gradually filled them with “something.” This evolution unfolds across three distinct stages. The literary evidence reveals a three-phase process by which Daoist robes lost their exclusive sacred connotation and gained secular meanings (Figure 4). In Phase 1, the robe functioned as a religious uniform. Ming ritual regulations mandated that only registered Daoist priests could officiate ceremonies, and they had to change from ordinary clothes into ceremonial robes beforehand. In effect, the robe was a legally enforced costume: it separated the worldly from the divine and lent solemnity to rites. Early Ming narratives consistently depict Daoist priests in plain wide-sleeved blue gowns as symbols of mystical authority, reinforcing the robe’s “holy” status. Thus, in Phase 1 the robe’s signification was internal to Daoism: its primary meaning was “sacred.” At this stage, wearing the Daoist robe itself “strengthened its sacredness,” drawing a clear line between laypeople and clerics (). In the literature of the time, Daoist priests in plain robes or wide-sleeved garments are often described as having “broad collars and sleeves,” conveying a solemn, otherworldly air. This highlights the robe’s role in the first stage as a symbol of Daoist authority and purity, helping to shape the hierarchy within the religion. Put simply, donning the robe during rituals is akin to wearing a sacred uniform: it signals the priest’s rank and reinforces the ritual’s sanctity.

Figure 4.

Schematic model of the “Three-Stage Semantic Flow of the Daoist Robe.” This model summarizes the three main stages in the transition of the Daoist robe from the religious domain to the secular domain, illustrating the flow and transformation of symbolic meaning across different social contexts.

Indeed, Stage 2 robes are at once profiles of institutional religion and instruments of social mobility. In Phase 2, the robe began to escape this purely religious domain and enter secular society, the Daoist robe came to be used not only by clergy but also in certain secular settings. It became a ceremonial everyday costume for special occasions. This reflects the penetration of religious symbols into daily life. The robe was no longer unique to clergy; it was appropriated by lay people who possessed sufficient cultural or economic capital. These groups began borrowing Daoist robes to attend weddings, funerals, and other ceremonial occasions.

Stage 3 occurs in the mid–late Ming, when the Daoist robe is fully ingrained as a popular fashion across classes. In Phase 3, Daoist robes had fully entered the realm of fashion. In late Ming society, they became a trendy garment admired by both elites and commoners alike. Novels describe young men, from scholar gentry to wealthy merchants, wearing bright, finely made Daoist robes as casual or festive attire. The color palettes and materials were often luxurious, completely breaking from the ascetic aesthetic of early Daoism. This corresponds to Bourdieu’s idea that taste stratifies social classes (). Cultured elites and affluent families adopted refined Daoist garments to signal their refinement, while ordinary townsfolk imitated them as a shortcut to prestige. In effect, the robe’s religious grammar was re-coded as a secular identity symbol; what once signified spiritual attainment now signified elegance, prosperity, or trendiness.

At this point, the robe’s original religious coding was recast as secular identity code. Once denoting mystical transcendence, it now signified elegance, wealth, or trendiness and Blumer’s view is confirmed; clothing meanings are not inherent but continuously created through social interaction. Indeed, some scholars note that by the late Ming, dress signified not just wealth but political or social rank (). The Daoist robe’s popularity epitomized this shift; what began as a symbol of religious office became a mirror of changing social fashion and cultural power. The robe’s journey from sacred vestment to secular fad thus illustrates the cultural transfer of symbolic authority from religious institutions to society at large.

To clarify the Daoist robe’s internal logic as it evolves over time, this study divides its trajectory into three key stages. Stage 1, Sacred Uniform, the robe functions solely as clerical garb, signifying religious authority. Stage 2, Ceremonial Dress, scholars and wealthy commoners introduce it into weddings, funerals, and ancestral rites, so it carries both sacred and status connotations. Stage 3, Secular Fashion, the robe becomes widespread, serving as a marker of taste and wealth. The timeline below illustrates the semantic shifts and paths of social diffusion across these three stages.

As the diagram shows, the Daoist robe’s symbolic center gradually shifted from the religious to the secular over time, demonstrating that its social meaning is not fixed but continually rewritten through the everyday interactions of different social strata.

4.2. Relation to Previous Research

Our findings engage in a constructive dialog with existing scholarship on religious symbols in fashion and material religion. Globally, scholars have long observed the secularization of sacred iconography. Religious symbols, crosses, stars, etc., originally tied to belief systems increasingly appear as decorative motifs in clothing and accessories, blending spiritual meaning with aesthetic trends. This commodification means a once purely sacred emblem can become a personal style statement, their functions transform. The Daoist robe’s fate follows this general pattern, just as wearers of cross necklaces today may not be devout, late Ming commoners donned Daoist robes for their social significance, not piety. Among ordinary folk, there was a gap between rich and poor, but it was far smaller than the gulf that separated them from the court. Their clothes were seldom fine; most were made of plain cotton. In () Yinyuan Zhuan, the merchant Yan Liesu 嚴列宿 has a “bright blue cotton Daoist robe” made and wears it to fetch his bride. At a scholar’s funeral, mourners likewise wear “white cotton Daoist robes.” Better fabrics do appear; Chuke Paian Jingqi mentions a merchant in a “blue velvet Daoist robe”. For most people, the point was simply to have a Daoist robe to wear, not to fuss over what kind it was.

By documenting this case in East Asia, our study broadens the comparative scope of research on secularization of religious dress, which has been dominated by Western examples. The Daoist robe follows this same trajectory. Just as a cross necklace in modern fashion does not always indicate Christian faith (), a Ming layperson wearing a Daoist robe need not be devoted; instead, the focus often lies on the robe’s social cachet. Thus, our case extends the literature’s scope, which has largely emphasized Western contexts, by providing a concrete East Asian example. In short, we offer new grounds for comparative religion and fashion studies. In the East Asian context, our study dialogs with research on material religion and transnational symbolism. Material religion scholars stress that religious meaning is embodied in objects and flows between sacred and mundane realms (). Prior work on Daoist material culture has focused on ritual implements or temple architecture, with few studies on dress. Our textual analysis shows that Daoist garments do not remain fixed in the holy sphere but are continually reinterpreted in secular life. In this sense, the Ming robe exemplifies an East Asian sacred–secular amalgam, religious artifacts are pragmatically repurposed in local society, creating new cultural contexts (). For example, some Korean records describe a “Korean Daoist gown” inspired by Ming styles, indicating that the robe’s semantic migration was not confined to China but moved across cultures, and then was redefined by local elites. Such cross-border circulation of religious dress underscores how Daoist clothing contributed to the broader East Asian material-religion landscape. By highlighting Daoist robes, we complement existing studies that have emphasized Buddhist kasaya or Christian vestments and thus broaden understanding of how Asian religious attire engages with popular fashion.

Additionally, our work resonates with the field of East Asian material religion. This perspective treats religious objects, clothing, artifacts, and temples as active media that interact with society to shape beliefs and practices. Prior material religion studies on Daoism have mostly focused on ritual implements, talismans, or temple architecture, with little attention to clothing. () detail the ritual significance of Daoist ceremonial robes, but few have traced what happens when those robes leave the temple. Ming novels provide a valuable ethnographic window, they show how the Daoist robe was “cycled” into folk life, exemplifying the distinctive East Asian feature of sacred secular fusion. Religious objects are not confined to holy spaces but are constantly re-appropriated in secular contexts, creating new cultural meanings. Our results demonstrate that clothing—as a form of material culture, can act as a carrier of religious–social interaction. The Daoist robe linked the official temple and the common world, witnessing the flow and transformation of Daoist cultural capital in Ming society. In this way, we extend material–religion research in East Asia; beyond the typical focus on Buddhist monastic robes, our case shows how Daoist attire participated in popular fashion. Interestingly, this phenomenon was not unique to China.Ming-influenced Korea developed its own “Korean Daoist robe,” indicating cross-cultural reinterpretation of Daoist symbols within the broader East Asian sphere. Thus, our case study of the robe enriches understanding of how religious dress traverses cultural boundaries.

Finally, from the perspective of fashion theory, the Ming Daoist robe’s trajectory exemplifies classic dynamics of fashion diffusion. Fashion scholarship notes that new styles often spread from an elite vanguard to the masses, and classic theories posit that fashion trends spread through a dual process of distinction and imitation (). Consistent with this, the robe became fashionable via top-down diffusion: elite literati and officials first wore it to express admiration for Daoist ideals, and later prosperous merchants and ordinary people emulated them, driving the trend to a peak. Our analysis aligns with this theoretical insight and adds nuance: unlike purely secular trends, the robe carried embedded religious authority. Its secularization involved not only a diffusion of taste but also a gradual relinquishment of sacred power. In other words, fashioning the robe meant transferring a dimension of sanctity into the secular realm. This finding broadens fashion theory by highlighting how symbols of diverse origin can become legitimate participants in secular style. Our analysis thus confirms Bourdieu’s insight that those with cultural capital shape taste, while lower classes follow. But it also advances the theory: unlike ordinary fashion items, the Daoist robe carried an inherited “sacred” origin. Its secularization thus involved not only class signaling but a transference of symbolic power from religious to lay domains. In other words, we show how fashion theory must account for the diversity of sources, as sacred symbols can enter the fashion system, a process that enriches classical accounts of taste (). Overall, the Ming robe provides a rich example of how clothing both reflects and negotiates social power relations, bridging temples and taverns, elite and commoner, confirming that apparel is a key locus for religion–society interaction ().

5. Conclusions

This case study of Daoist robes in the Ming Dynasty literature underscores the complex interplay between religion, fashion, and social identity. By carefully translating and analyzing Chinese literary sources, we have identified a clear evolution wherein Daoist attire transitioned from sacred insignia to secular status symbol. Our study offers three key contributions.

Firstly, we proposed a novel three-stage semantic transformation model (from sacred uniform to ceremonial attire, and finally to secular fashion), integrating symbolic interactionism, cultural capital, and social performance theory. This interdisciplinary approach provides a new theoretical framework that can be applied broadly to analyze how religious symbols are dynamically re-coded through social interactions.

Secondly, we provide an important non-Western, East Asian case study on religious secularization, thus significantly enriching comparative scholarship. Previous research has predominantly focused on modern, Western, or Christian contexts; our analysis demonstrates that premodern Daoist symbols underwent a similar secularization process, broadening scholarly understanding of the global phenomenon of religious symbol commodification.

Thirdly, by emphasizing clothing as a form of material religion, we reveal how garments actively mediate sacred-secular boundaries. Through detailed textual analysis, we demonstrated that Daoist robes became pivotal points where religious authority interacted and merged with popular social practice, shifting Daoist cultural capital from temples to everyday life and reflecting broader socio-cultural transformations in Ming China.

In practical terms, our findings suggest that mid-Ming sumptuary laws and religious doctrines could not permanently fix symbolic meanings. Instead, ordinary individuals creatively appropriated the Daoist robe, repurposing it into a versatile medium for performing social respectability, moral legitimacy, and economic success. This active secularization signals a broader shift in cultural power from religious institutions to the general populace, demonstrating how religious dress can become integral to secular social identity construction.

Thus, the evolution of Daoist robes during the Ming period provides rich historical evidence for understanding how clothing mediates personal and collective identities. Our findings underscore the flexibility of religious symbols and their ability to adapt to new social contexts, bridging traditional spirituality and emerging secular sensibilities. Our interdisciplinary perspective and findings also encourage future studies on other East Asian religious garments, such as Buddhist vestments, and contribute to broader scholarship exploring fashion as a cross-cultural communication medium.

However, our study does acknowledge specific methodological and contextual limitations. Firstly, this research relies primarily on literary depictions from Ming dynasty novels, which may involve exaggeration or stylistic conventions, potentially limiting direct historical generalizability. Future research could strengthen the empirical basis by systematically integrating extant garments, visual artifacts, costume annotations, and contemporaneous historical documents. Secondly, while our analysis focuses specifically on Daoist robes, it leaves unexplored the secularization of other religious garments, such as Buddhist robes and Daoist headgear. Comparative studies examining whether the identified three-stage semantic model applies universally across various religious clothing items would significantly enrich our understanding of religious dress secularization dynamics. Thirdly, regarding theoretical integration, although this research introduces a robust interdisciplinary framework, further research could explore in greater depth how Ming political ecology, state policies on religion, and control over local religious organizations specifically influenced the secular adoption of religious attire.

Based on these insights, this study suggests several promising directions for future research. Firstly, tracing the continued transmission and reinterpretation of Daoist robe imagery from the Ming and Qing dynasties to contemporary visual culture would illuminate the modern cultural memory of religious dress. Understanding how historical religious symbols are reshaped through visual media offers valuable insights into modern cultural identity processes. Secondly, from a cultural and creative industry perspective, our study proposes fresh possibilities for incorporating traditional costume elements into contemporary fashion design. The symbolic motifs, patterns, and structural forms of Daoist robes provide unique aesthetic resources that contemporary designers could reinterpret creatively. Effective interdisciplinary collaboration between historians, cultural scholars, and design practitioners will be essential to ensure meaningful cultural reinterpretation rather than superficial appropriation. Thirdly, digital humanities methodologies present exciting opportunities for further investigation. Future research might systematically develop comprehensive digital databases of Ming–Qing costume references, utilize text-mining tools to quantitatively track symbolic trends, or employ 3D modeling and virtual reality to digitally reconstruct historical garment styles and wearing contexts. Such innovative methodologies would not only enhance scholarly analyses but also significantly broaden public engagement with East Asian material religious culture.

In summary, our research on the secularization of Daoist robes contributes importantly to ongoing scholarly conversations about how religion, fashion, tradition, and modernity interact dynamically across time and cultures. By highlighting the adaptability and enduring cultural resonance of traditional religious symbols, this study provides valuable insights relevant both academically and practically within East Asia and beyond.

Looking ahead, this three-stage semantic model offers a valuable analytical framework for studying the secularization and transformation of other religious garments, such as Buddhist kasaya or Christian vestments, across different times and cultures. More broadly, our findings illuminate the dynamic role of dress as both a medium and a mirror of changing identities, beliefs, and power structures in society. By tracing the journey of the Daoist robe, we contribute to a deeper understanding of how material symbols continue to bridge tradition and modernity, the sacred and the secular, in a globalizing world.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.B.; methodology, M.T.; formal analysis, M.T.; resources, M.T.; writing—original draft preparation, M.T.; writing—review and editing, L.Z.; visualization, M.T.; supervision, L.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Xiangyang Bian for academic guidance and the editorial staff of Religions for their support and guidance during the review process.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Andersen, Poul. 2010. The Life of Images in Daoist Ritual. Paper presented at “The Chinese Art of Enlivenment: A Symposium,” East Asian Art History Program, Harvard University. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/5913592/The_Life_of_Images_in_Daoist_Ritual (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Blumer, Herbert. 1969. Symbolic Interactionism: Perspective and Method. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1984. Espace social et genèse des "classes". Actes de la Recherche en Sciences Sociales 52: 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Lesong 程樂鬆. 2017. Shenti busi yu shenmizhuyi-daojiao Xinyang de guannianshi shijiao身體、不死與神秘主義-道教信仰的觀念史視角 Daoism: Body, Immortality, and Mysticism]. Beijing: Peking University Press. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Deng, Sibo 鄧斯博. 2014. Rushen yu daoyi: Zhuyoudun shangju de sixiang yiyun儒身與道衣:朱有燉慶賞劇的思想意蘊 [Confucian Body and Daoist Garments: Zhu Youdun’s Dramatic Ideology]. Masterpiece Appreciation, 10–11. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Goffman, Erving. 1959. The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. Garden City: Doubleday. [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi, Masayoshi. 2010. Zhongguo de daojiao中國的道教 [Daoism in China]. Jinan: Qilu Shushe. [Google Scholar]

- Laozi. 2009. Tao Te Ching. Guangzhou: Zhonghua Book Company. First published ca. 4th century BCE. [Google Scholar]

- Mirola, William A., Michael O. Emerson, and Susanne C. Monahan, eds. 2015. Sociology of Religion: A Reader. San Mateo: CourseSmart eTextbook. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery, James D. 2003. A Formalization and Test of the Religious Economies Model. American Sociological Review 68: 782–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, Teresa. 2015. Roman Faith and Christian Faith: Pistis and Fides in the Early Roman Empire and Early Churches. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Neal, Sarah L. 2019. Religion in Vogue: Christianity and Fashion in America. New York: NYU Press. [Google Scholar]

- Newson, Linda, and Peter J. Richerson. 2008. Is Religion Adaptive? In The Evolution of Religion: Studies, Theories & Critiques. Edited by Joseph Bulbulia, Richard Sosis and Erica Harris. Santa Margarita: Collins Foundation Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schipper, Kristofer. 1985. Vernacular and Classical Ritual in Taoism. The Journal of Asian Studies 45: 21–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Songjiang Prefecture Records 鬆江府志. 2005. Territory Records: Customs. Beijing: Beijing Library Press, vol. 4. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Throsby, David. 1999. Cultural Capital. Journal of Cultural Economics 23: 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xizhousheng 西周生. 2019. Xingshi Yinyuan Zhuan 醒世姻緣傳. Changsha: Yuelu Academy, Chapter 23. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, Zujie. 2007. Dressing for Power: Rite, Costume, and State Authority in Ming Dynasty China. Frontiers of History in China 2: 181–212. [Google Scholar]

- Zeller, Benjamin E., and Marie W. Dallam. 2023. Religion, Attire, and Adornment in North America. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).