1. Introduction

In the late Eastern Jin, the political order underwent drastic upheavals: first with Huan Xuan’s 桓玄 usurpation, followed by Liu Yu’s 劉裕 replacement of the Jin dynasty. Many members of the imperial Sima 司馬 clan suffered persecution and calamity. Facing a crisis of survival, most of the Sima clan chose to flee northward, where they eventually found refuge and reestablished their lineages under the Northern Dynasties. Existing research on the northward-fleeing Sima clans has largely been conducted from the perspectives of political history and family history, with particular focus on the branch of Sima Chuzhi 司馬楚之. Scholars have conducted comprehensive studies on this lineage through genealogical reconstruction (

Luo and Zhou 2015), analyses of family fortunes (

Horiuchi 2010;

Guo 2011;

Cheng 2014), ethnic integration (

X. Zhang 2014), and the materiality of epitaphs (

Fan 2020). As for other branches of the clan, research has mainly relied on epitaphic evidence to reconstruct the identities and lives of individual members (

Zheng 1979;

Ma 1993;

H. Zhang 2012;

Sun 2020;

Lan 2019).

Nevertheless, existing research has paid relatively little attention to the religious practices of the Sima clan within the social networks of the Northern Dynasties, particularly their engagement with Buddhism. It is worth noting that some women who married into the Sima family were already adherents of Buddhism—for example, Yuan Huaguang 元華光, wife of Sima Yi 司馬裔, whose case has received preliminary scholarly attention (

Fu 2019;

Zhou and Wang 2019, pp. 7–9). Although some scholars have studied branches of the Sima clan during the Eastern Wei and Northern Qi (

K. Su 2022;

J. Liu 2022), they overlooked the figure of Yuan Nanzi 垣南姿, the sister-in-law of Sima Zunye 司馬遵業. Instead, Yuan Nanzi has received occasional mention in Buddhist studies concerned with bhikṣuṇīs (

S. Shi 2013;

Y. Wang 2019;

F. Shi 2024). To date, there has been no specialized research focusing on Yuan Nanzi. As a member of the northward-fleeing Sima clan, however, she provides a new perspective for understanding the development of the family during the Eastern Wei and Northern Qi.

Moreover, as a Buddhist bhikṣuṇī, her ordination process, religious practices, and burial arrangements diverged markedly from those of most contemporaries. In addition to studying women’s motivations for joining the monastic community (

Huang 2002, pp. 91–92;

M. Wu 2002, pp. 257–63;

Li 2011, pp. 59–61;

Le Zhang 2013, pp. 21–42;

C. Chen 2016, pp. 19–30), researchers have taken interest in the unusual practice of “faith at home” (

Hao 2010, pp. 82–89;

J. Chen 2002, pp. 51–85;

G. Zhang 2002, pp. 242–47;

S. Su 2003, pp. 84–88;

Yang 2004, pp. 22–26;

Q. Liu 2010, pp. 108–11;

M. Zhang 2012, pp. 46–58). Explanations for this include insincere motives for taking vows, the diminishing privileges of the Buddhist establishment (

Zhu 2013, pp. 65–79), Confucian filial piety (

Wei 1985, pp. 20–22;

Lu 2002, pp. 70–92;

Duan 2010, pp. 80–82), and the family-oriented ethical teachings within Buddhism itself (

Shao 2016, pp. 19–20). Nevertheless, many prior studies remain generalized, and the particularities of individual lives are often lost in statistical aggregates and sweeping narratives.

Drawing on the Epitaph of Yuan Nanzi 垣南姿墓誌, this paper thereby investigates her personal life history and her family’s development, analyzing the tensions and decisions arising from the interplay between her secular and religious role. Through this case study, this paper aims to reassess the varied forms of belief and life practices among bhikṣuṇīs during the Northern Dynasties and the subsequent Sui and Tang Dynasties.

The

Epitaph of Yuan Nanzi was unearthed in 1957 approximately one mile north of the Jiangwucheng 講武城, Ci County 磁縣, Hebei 河北. In 1959, the inscriptions on the epitaph cover and the front side of the epitaph stone were published, though the image was relatively unclear (Hebei Provincial Cultural Relics Management Committee 1959, p. 25). In 2021, the

Nanbeichao Muzhi Jicheng 南北朝墓誌集成 included the text on the front side of the epitaph (

L. Wang 2021, pp. 704–6). In the same year, the

Cixian Beichao Muqun Chutu Beizhi Jishi 磁縣北朝墓群出土碑誌集释 presented the complete texts of the front and both lateral sides, along with annotations and a clear rubbing featured in

Figure 1 (

Ma et al. 2021, pp. 187–91).

The epitaph cover is in the form of a gabled roof (luding 盝頂), inscribed in intaglio with regular script showing the influence of the clerical style, comprising 4 lines with 16 characters in total. The epitaph stone is square, measuring 67 cm on each side, and bears inscriptions on the front and on both lateral sides. The calligraphy exhibits clerical script traits with elements of regular script. The front inscription consists of 33 lines, each containing up to 32 characters, arranged in vertical and horizontal grids. Each lateral side comprises 6 lines but is badly eroded. The elegiac text was composed by Wei Shou 魏收, while the biographical section is narrated from the perspective of Sima Yingzhi 司馬膺之, Yuan Nanzi’s second son. The content is detailed and holds considerable historical value, offering opportunities for mutual verification with transmitted texts and other epitaphs. The transcribed text of the epitaph is presented below:

1Epitaph Cover 誌蓋:

Late Qi Epitaph of the Sima’s Grand Matron Bhikṣuṇī Yuan 齊故司馬/氏太夫人/比丘尼垣/墓誌之銘.

Text on the front side of the epitaph 墓誌正面文字:

Late Qi Epitaph of the Grand Matron Bhikṣuṇī Yuan 齊故比丘尼太夫人垣氏墓誌並銘/

The grand matron Nanzi, whose monastic name was Daoxin, was a native of Huandao, Lüeyang. A remote ancestor, General-in-Chief Qi, earned merit during the Qin dynasty. Her eighth-generation grandfather, Palace Attendant Hun, established virtue in the Jin dynasty. Her grandfather Tong served as Governor of Wuwei Commandery and was renowned for his Confucian scholarship. Her father Rui held the post of Aide to the Pingbei General and was praised for his virtuous character. 太夫人諱南姿,法諱道信,略陽狟道人。上將軍騎立功於秦世,殿中郎渾樹德於晉朝,/中郎即太夫人八世祖也。祖通,武威太守,儒術見稱。父叡,平北司馬,德素歸美。

The grand matron was serene by nature, virtuous in spirit, wise and graceful, gentle and compliant. Though not broadly studied in youth, she later delighted in Buddhist scriptures, mastering whatever she set her mind to. At sixteen, she was married to our father. Our grandmother was her second paternal aunt. Despite their close kinship, she never let it diminish her wifely devotion, serving with devout reverence and never neglecting her domestic duties. She matched the mother of Wenbo in household management and equaled the mother of Mencius in cutting the loom and admonishing us. By the will of heaven, we brothers were orphaned young, bereft of our father’s protection. It was through mother’s rearing that we reached adulthood and secured official posts, upholding our family’s honor—all to her credit. Our younger uncle, the Defender-in-Chief and Duke Wenming, bore a weighty mandate from the court and stood at the pinnacle of the ministerial hierarchy. Yet, the mutual propriety between our mother and himself was observed by both without fail. The tailoring of garments and preparing of household meals were all entrusted to the great matron; only then was he content. 太夫人/禀質沖和,資神懿淑;貞明婉敏,温恭柔順。雖少不外學,晚好釋典,留心之處,輒即受持。/年十六歸于先君。先大太夫人即太夫人第二姑也。虔奉至謹,箕箒靡違,不以子/姪私思而蹔虧婦道。及效績爲業,情均文伯之親;斷織厲訓,志齊孟軻之母。膺之等行/悟靈祇,夙傾乾蔭,兄弟孤藐,實緣鞠粹。爰逮成人,並荷通宦,名義未墜,仰稟斯由。季/父太尉,文明公,任隆朝寄,位極台衮。至於嫂叔之禮,敬事無闕。裁製衣裘,調品中饋,皆/委太夫人,然後安焉。

The great matron’s sincere and devout faith was innate. Though living in wealth and honor, she did not take them to heart: how could the glamor she witnessed occupy her thoughts? She had long resolved to devote her entire life to the Three Jewels. Yet we brothers, bound by long-held ignorance, did not understand karmic causation and for years persuaded her to remain. But her insight grew ever deeper, and her devotion ever more ardent. She even declared: “If you do not permit me to enter the monastic life, I shall secretly shave my hair, leaving you with endless regret.” Having repeatedly received such earnest petitions, we dared resist no longer. On the fifteenth day of the ninth month in the tenth year of Tianbao (559), she lavished the family resources to prepare a great vegetarian feast, gathering eminent monks and venerable elders. In the central hall of her residence, a Dharma platform had long been established, which she adorned with the utmost decorum and where she worshiped daily with reverence. It was in this context that she respectfully undertook the formal ordination. At that time, the great matron was seventy-three years old. Although her years advanced, her will and practice grew only loftier. Whenever Dharma events were held on the new and full moons, she would personally ascend the high seat to expound the precepts for the assembly with solemn demeanor and harmonious voice. All who attended these gatherings could not but praise her. Throughout her life, she continually gave away her clothing and possessions as alms. From the official salaries of we brothers, she often set aside portions to increase merit. Our fourth brother, Youzhi, served in office in Jinyang; as Recorder to the Counselor-in-Chief, he was appointed Governor of Yangping Commandery. Having been separated for many years, he welcomed great matron to his commandery. 太夫人精誠信向,出自天骨。雖處富貴,不以介懷;所見榮華,寧將/在意?久以一生,歸付三實。但膺之等積習愚迷,不識緣果,共生惑障,勸戀多年。而妙解/逾深,篤向弥初。又言:汝輩若不許我出家,我必闇自剔落,使汝等後悔無及。既頻奉誠/勅,不敢更違。以天保十年九月十五日,傾竭家資,奉營齋供,名僧碩德,罔不雲萃。中堂/院内,素置道塲,妙盡莊嚴,躬常頂禮,仍以此辰,敬披法服。于時太夫人春秋已七十有/三矣。年力轉高,志行逾峻。及於法事與設,晦望説誡,常親昇高座,爲衆敷陳,儀貌肃愸,/音止和穆。凡預下莚,莫不讚美。平生衣物,随有散施。及膺之等俸幹,率多抽减,迥用崇/福。第四弟幼之從宦晋陽,以大丞相主簿,蒙授陽平太守。違離歲久,奉迎之郡。

The great matron was advanced in age and had long suffered from dizziness and fatigue. Our third brother, Zirui, Concurrently Minister of Sacrifices, was stricken by illness last spring which lingered through the winter. But heaven did not grant goodness, and his illness proved incurable. The sudden news of his death brought the great matron wailing and grief. After this, her vitality daily waned; within ten days, she entered her final decline. On the twenty-seventh day of the intercalary twelfth month in the first year of Daning (561), in the official residence of the commandery, she passed away at the age of seventy-five. Yingzhi, constrained by official duties and burdened by guilt and remorse, rushed as if by starlight, howling on the road; mother’s kindly visage was gone, and his mourning was without end. On the twenty-seventh day of the first month in the following year (562), the funeral carriage departed the commandery and returned to the capital, proceeding to the old residence. Though her spirit journeyed to the Pure Land, her passing was mourned as shared sorrow. All the officials and commoners, near and far, monastics and laypeople mourned her as if losing their own kin. The great matron often said she would keep herself frugal, as ancient valued; plain skirts and simple shoes were her true intent. Moreover, now she following the Buddhist teachings, it was even more necessary to be reverent and cautious. Hence, she urged frugality: for her funeral, she desired only simplicity; even a fitting coffin was not her wish. How could we brothers dare disobey her lofty will? They relied upon her noble model to guide their descendants. On the twentieth day of the second month in the second year of Daning (562), she was interred seven miles northwest of Ye at Zimo. Her boundless love and compassion cannot be fully told; the grief and calamity is too heavy to record. Grasping at what breath remains, I set down this truthful record. Wei Shou of Julu, Commander Unequalled in Honor, Secretariat Supervisor, and Right Grand Master for Splendid Happiness, a comprehensive scholar of his generation whose literary brilliance crowned the age. Both with the living and the departed of the family, had long been connected; respectfully entrusted with this inscription, to express our grief. Its inscription reads: 太夫人/年高,舊有勞眩。第三弟,兼祠部尚書子瑞,去春婴患,綿曆冬中,天不與善,無救所疾。凶/書忽至,舉哭增傷。因此之後,神力日退,隔有一旬,遂就大漸。大寧元年閏十二月,廿七/日戊辰,在郡官舍,奄致無常,时年七十有五。膺之既限官守,加以誠行信負,星駕馳奔,/長嗥在路,慈顔冥遠,崩慕無及。以正月廿七日,靈輿發郡還都,將旋舊宅。雖神遊浄/土,而遷謝同哀。合郡吏民,遠近道俗,莫不攀嗥追慕,若喪己親。太夫人每言約己儉身,/古賢所尚,帛帬鳥履,實會宿心。况今依承内教,弥須祇慎,其後送终之具,務從约省,棺/槨周驅,亦非所願。膺之等何人敢違高旨。方憑雅範,貽厥孫謀。粵以大寧二年二月辛/丑朔廿日庚申,窆於鄴紫陌西北七里。至愛鴻慈,既言不知盡;巨毒深殃,亦書何能載?/貪及餘喘,辄䟽實録。開府儀同三司、中書監、右光禄大夫鉅鹿魏收,一代通人,文華冠/世。昆季存亡,並蒙交結,敬託爲銘,少申哀疚。其辭曰:/

Far away in the western lands, she was born of a noble lineage. Merit established, words renowned; traces lofty, talents eminent. Like pearls hidden in pure waters, like jade concealed in flourishing woods. Since things are thus, the family is likewise ancient. Grace and refinement did not perish, but resounded through the generations. Men succeeded in their age; women were known for their repute. Gentle and serene, she possessed natural grace and charm. Skilled in letters and propriety, accomplished also in practical arts. With these […] her mind grew even broader. Discerning doubts like a trigger, responding to words like an echo. Filial piety came from the heart, humaneness not externally urged. Matched to a worthy husband, her guest-like respect was admirable. Her husband […], […] orphaned sons. Affairs beset by family thorns, the times traversed dangerous paths. She taught with the resolve of Mencius’ mother, and moved like Tian Su’s mother. Her sons rose in office and reputation, fulfilling her noble plan. Generations received her exemplary model, […] splendid array. Amid honor she remained humble, her nature ever pure. Reflecting on emptiness, she saw clearly that life must end. Shedding dust, removing fetters, the Way lofty, conduct peerless. Amidst the mundane, she served as a master, guiding disciples toward the profound gate of Dharma. She elucidated its principles with nuance, all while engaging with the prevailing Confucian teachings. Like a wine vessel in the crossroads, sharing brilliance that outshone others. The Triple World does not retain; the Four Assemblies increase their mourning. From toil returning to ease, […] spirit moving beyond. Planting these lush fruits, […] excellent karmic causes. The wondrous terrace now towers high; the dark hall knows no dawn. Her fame has its heirs, and on this day her kin are honored. 逷矣西土,世家之胄。功立言揚,迹高才秀。珠藏水潔,壁潛林茂。物既有之,門亦雲舊。風/流不殞,代振其聲。男爲時後,女則知名。柔閑獨得,婉嫕天成。文義咸舉,工藝兼精。以兹/□□,令心逾廣。辯惑猶機,應言如響。孝由衷至,仁非外獎。君子作合,賓敬可仰。良人不/□,□尔諸孤。事嬰家棘,時逕險途。訓弘孟母,遊致田蘇。宦通名立,㯹此令圖。世承徽範,/□□懿列。在榮能降,體真逾潔。懸鑒空有,深昭假滅。落塵去累,道高行絶。素里作師,玄/門斯導。抑揚風旨,沈浮名教。衢罇待酌,輸輝掩照。三界不留,四部增悼。自勞歸逸,反□/遷神。植兹茂果,□□勝因。妙臺方峻,玄堂弗晨。揚名有屬,是日榮親。/

Text on the right side of the epitaph 墓誌右側文字:

Our father, posthumously honored as Unequaled in Honor and Governor of […] Province (illegible below). Second son, Yingzhi, courtesy name Zhongqing, (illegible below). Li clan of Longxi; her father Jin held posts as Senior Recorder for Comprehensive Duty and Governor of […] Province. […] son Jingze, aged twenty-seven, Administrator to the Minister over the Masses. (illegible below). Jingze’s younger brother Keseng, aged ten-something. His wife was from Lu clan of Fanyang; her father […], belonging to […], Governor of Rencheng Commandery. Keseng’s younger brother (illegible below), aged nine. […]su’s younger brother Jingwei, aged thirteen. Yingzhi’s daughter Zhaonan, aged twenty-five, married to Wei Xianggui, Unequaled in Honor and […] General. Next daughter (illegible below), aged six. Next daughter Xiangyou, aged three. (illegible below). (illegible above) wife, Lu clan of […]nan. (illegible below) Supervisor. 皇考,魏故贈儀同三司、□州刺史。(下泐)/第二息膺之,字仲慶,(下泐)隴西李氏,父瑾,通直散騎、□州刺史。/□□息敬則,年廿七,司徒參軍。(下泐)則弟客僧,年十□,妻范陽盧氏,父子/□,□徒屬、任城太守。□僧弟(下泐)年九。□素弟敬微,年十三。膺之之女招男,年廿五,/適尉相貴,儀同三司、□□將軍。次女(下泐),年六。次女相遊,年三。(下泐)/(上泐)妻□南陸氏,(下泐)監。/

Text on the left side of the epitaph 墓誌左側文字:

His son Tongyou, aged thirty-something, (illegible below). His wife from Li clan of Dunqiu, (illegible below). Tongxian, aged twenty-four. Tongxian’s younger brother Tonghui, aged ten-something. Tonghui’s younger brother Tong[…], aged thirteen. Zirui’s eldest daughter Yigui, aged twenty, married to Zheng Zheng of Xingyang. Next daughter Yining, aged thirteen. Next daughter Yi[…], aged seven. Fourth son, Youzhi, courtesy name Jiqing, aged forty-seven, served as Governor of Yangping Commandery and Founding Viscount of Pinggao County. His wife from Lu clan of Fanyang; her father Daoqian held posts as President of the Section for Justice and Founding Duke of […] County. Youzhi’s son Gangqi, aged thirteen. Gangqi’s younger brother Wen[…], […]. […]’s younger brother […], aged five. Fifth son, Jichong, aged forty-five, served as Reader-in-Waiting to the Crown Prince. His wife from Yuan clan of Henan; her father (illegible below). Guangzong, aged seventeen. Guangzong’s younger brother […]shi, aged nine. […]shi’s younger brother […]dao, aged eight. […]dao’s younger brother Wenshi, aged three. (illegible below). Next daughter De[…], aged twenty-four, […]seng’s son Zuzhou, aged three. 息同遊,年卅(下泐)軍,妻頓丘李氏,(下泐)同憲,年廿四。憲弟同迴,年十□。/迴弟同□,年十三。瑞大女宜歸,年廿,適滎陽鄭拯。次女宜寧,年十三。次女宜□,年七。/第四息幼之,字季慶,年卌七,陽平太守、平臯縣開國子。幼之妻范陽盧氏,父道虔,都官尚書、/□縣開國公。幼之息剛器,年十三,器弟文□,□□□,□弟□□,年五。/第五息季沖,年卌五,太子洗馬,妻河南元氏,父(下泐)廣宗,年十七。宗弟□士,年九。/士弟□道,年八。道弟文師,年三(下泐)。次女德□,年廿四,□僧息祖胄,年三。

Figure 1.

Epitaph of Yuan Nanzi 垣南姿墓誌, engraved in the second year of Daning 大寧 era (562), unearthed in Ci County 磁縣, Hebei 河北 Province (

Ma et al. 2021, p. 188).

Figure 1.

Epitaph of Yuan Nanzi 垣南姿墓誌, engraved in the second year of Daning 大寧 era (562), unearthed in Ci County 磁縣, Hebei 河北 Province (

Ma et al. 2021, p. 188).

2. Wifely Virtues

Yuan Nanzi, whose monastic name was Daoxin, was a native of Huandao 桓道, Lüeyang 略陽. She was born in the eleventh year of the Taihe 太和 era of the Northern Wei (487) and died on the twenty-seventh day of the intercalary twelfth month in the first year of the Daning 大寧 era (561) of the Northern Qi at the age of seventy-five. She was buried northwest of Ye 鄴 on the twenty-seventh day of the first month in the following year.

The ancestors recorded in the epitaph—her eighth-generation grandfather Hun, her grandfather Tong, and her father Rui—are all absent from transmitted historical texts. The Yuanhe Xingzuan 元和姓纂 records under the surname Yuan 垣: “Descendants of Yuan Gong, Governor of Xihe Commandery during the Han dynasty. Yuan Chang, Minister of Personnel under Murong De of the Southern Yan, was among those relocated from Lüeyang to Ye by Shi Jilong. Yuan Chang, along with his sons Zun and Miao, surrendered to the Jin dynasty. Yuan Chang was commissioned General of Longxiang, Zun was appointed Cavalier Attendant-in-Ordinary, and Miao was made Commandant of Garrison Cavalry. Miao sired Huzhi and Xun 漢西河太守垣恭之後。南燕慕容德吏部尚書垣敞,石季龍略陽地徙之于鄴,敞與子遵、苗並降晉,敞拜龍驤將軍,遵散騎常侍,苗屯騎校尉,苗生護之、詢.” The annotation notes that the character “Zhi 之” is missing after “Xun 詢” (Yuanhe Xingzuan 1994, pp. 456–57). Yuan Chang’s descendants were frequently involved in the conflicts between the Southern and Northern dynasties: his son Yuan Miao long defended Luodang 洛當 Castle against Northern Wei advances; his grandson Yuan Huzhi campaigned against Sima Xiuzhi 司馬休之 and participated in the northern expeditions of Dao Yanzhi 到彥之 and Wang Xuanmo 王玄謨; his great-grandson Yuan Gongzu 垣恭祖, following Shen Youzhi’s 沈攸之 northern campaign, was captured by Northern Wei forces after defeat; another great-grandson Yuan Chongzu 垣崇祖also fled to the Northern Wei after a defeat in a power struggle, but returned south soon. The surname Yuan does not appear in the transmitted historical records of the Northern Dynasties. Considering Yuan Chang’s relocation to Ye and his descendants’ experience, Yuan Nanzi was likely one of his descendants.

According to the epitaph, Yuan Nanzi’s mother-in-law was her paternal aunt. Nevertheless, she served her parents-in-law with utmost care and strictly observed the wifely virtues. Shi Shaoxin 石少欣 identified Yuan Nanzi as the wife of Sima Zuan 司馬纂 (

S. Shi 2013, pp. 86–87). Yin Xian 殷憲 based on his study of the

Epitaph of Sima Jichong 司馬季沖墓誌 and the

Epitaph of Sima Jichong and His Wife Yuan Kenü 司馬季沖暨妻元客女墓誌, proposed that Sima Jichong was the youngest son of Sima Zuan (

Yin 2016, pp. 26–27). Other scholars also concur with this view (

Zhou and Wang 2019, pp. 405–6). However, they overlooked the fact that there were two contemporaneous individuals named Sima Zuan during the Northern Dynasties, mistakenly identifying the one mentioned in the epitaphs as the second son of Sima Jinlong 司馬金龍.

Sima Jinlong did indeed have a son named Sima Zuan, who had two sons named Cheng 澄 and Zhongcan 仲粲 (

Weishu 2018, pp. 949–50). Furthermore, the

Epitaph of Yuan Tan’s Wife Sima 元譚妻司馬氏墓誌 reveals that this Sima Zuan also had an eldest daughter who married Yuan Tan, a clansman of the Northern Wei imperial family (

L. Wang 2021, pp. 212–13). These details, however, do not correspond to the information concerning Yuan Nanzi’s descendants as recorded in her epitaph. Instead, they align perfectly with the known descendants of the Sima Zuan who was the elder brother of Sima Zunye, as corroborated by transmitted historical records and the

Epitaph of Sima Zunye 司馬遵業墓誌 (

L. Wang 2021, p. 640). Consequently, Yuan Nanzi must have been married to Sima Zuan, the eldest son of Sima Xinglong 司馬興龍 and the elder brother of Sima Zunye.

Transmitted historical sources offer only a glimpse of Sima Zuan, likely due to his premature death: “Ziru’s elder brother Zuan died early; when Ziru became prominent, Zuan was posthumously awarded the title of Governor of Yue Province 子如兄纂,先卒,子如貴,贈岳州刺史” (

Bei Qi Shu 1972, p. 261). A discrepancy appears in The

Epitaph of Sima Jichong, which records Sima Zuan’s titles as Unequaled in Honor and Governor of Qing 青 Province (

Yin 2016, p. 206). The

Epitaph of Yuan Nanzi refers to him as “Unequaled in Honor and Governor of […] Province”. Unfortunately, the crucial character for the province name is illegible, making it difficult to ascertain which account is correct. Another plausible possibility is that Sima Zuan held both governorships in succession.

3. Maternal Role

As a mother, Yuan Nanzi’s devoted nurturing of her sons stemmed not only from maternal instinct but also from the reality of being left alone to sustain the family after her husband’s untimely death. Moreover, the crisis triggered by her eldest son’s involvement in rebellion further transformed this duty into an inescapable mission. As recorded in transmitted historical texts, Yuan Nanzi had four sons: Shiyun 世雲, Yingzhi 膺之, Zirui 子瑞, and Youzhi 幼之. The Epitaph of Yuan Nanzi, however, reveals the existence of a fifth son, Jichong 季沖. The epitaph provides the courtesy names of Yingzhi (Zhongqing 仲慶) and Youzhi (Jiqing 季慶), allowing us to infer that Shiyun’s was Boqing 伯慶 and Zirui’s was Shuqing 叔慶. Notably, Shiyun alone is omitted from the epitaph. A clue is provided by the line in the eulogy, “Affairs beset by family thorns, the times traversed dangerous paths.” Shiyun had joined Hou Jing’s 侯景 rebellion. After its failure, his brothers were spared execution and merely exiled to the northern frontier, thanks to Gao Cheng’s 高澄 regard for their uncle Sima Zunye (Beishi 1974, p. 1950). Shiyun, however, was killed by Hou Jing for his disloyalty, leading to his erasure from the epitaph. Having endured these tribulations, the widowed Yuan Nanzi found her sole purpose in educating her children to revive the family. Her sons subsequently secured official positions under her guidance.

The second son, Yingzhi, was enfeoffed as Duke of Xuchang 須昌 County, a title he obtained from his uncle. Sima Zunye treated his sister-in-law with propriety and cared for his nephews with kindness (

Bei Qi Shu 1972, p. 260), and in return, Yingzhi and his brothers served him as a father. It is fair to say that the survival and status of Sima Zuan’s family in the Eastern Wei and Northern Qi were largely attributable to Sima Zunye’s patronage. Yingzhi’s official career saw him appointed as Grand Master for Splendid Happiness towards the end of the Heqing 河清 era (562–565). Unfortunately, he suffered from chronic dysentery that confined him for years. During the Wuping 武平 era (570–576), he was honored at home with the title of Unequaled in Honor, but ultimately succumbed to the illness. His wife was from the Li 李 clan of Longxi 隴西, daughter of Li Jin 李瑾. Li Jin, celebrated for his handsome appearance and literary talent, won the admiration of Prince Qinghe 清河, through whose support he entered government service. Li Jin, alongside Wang Zunye 王遵業 and Lu Guan 盧觀, oversaw court rituals. Their collaboration prompted the jest that “the three elites jointly administer the imperial ceremonies, truly a state of uncles and nephews 卿等三俊,共掌帝仪,可谓舅甥之国” (

Weishu 2018, p. 982). Li Jin was also commissioned to draft the posthumous honorific for Emperor Xiaoming (r. 515–528). Yingzhi’s second son, Keseng 客僧, married a woman from the Lu 盧 clan of Fanyang 范陽, a leading Han aristocratic family. Yingzhi’s daughter, Zhaonan 招男, married Wei Xianggui 尉相贵, of the Yuchi 尉遲 clan—a prominent Xianbei lineage that had sinicized its surname to Wei 尉. Wei Xianggui’s father, Wei Biao 尉摽 (尉㯹), was a meritorious general from Huaihuo 懷朔 who followed Gao Huan 高歡 in his campaigns. He was posthumously enfeoffed as Duke of Haichang 海昌, a title Wei Xianggui inherited (

Bei Qi Shu 1972, p. 281;

Beishi 1974, p. 1910;

L. Wang 2021, pp. 690–91). These marriages demonstrate that the Yingzhi family was firmly integrated into the highest echelons of both Han and Xianbei aristocracy.

The third son, Zirui, rose to the position of Censor-in-Chief and was recognized by the court for his impartial investigations and recommendations. He later left office due to illness and was subsequently appointed as the Minister of Sacrifices. After his death, he was posthumously granted as the Governor of Ying 瀛 Province. His wife was the younger sister of Lu Lingxuan 陸令萱, the wet nurse of Emperor Gao Wei (r. 565–577). Owing to Lu Lingxuan’s favor with the emperor, Zirui was posthumously granted, for a second time, the title of Governor of Huai 懷 Province. His sons all held prominent positions: “Tongyou served as Gentleman-Attendant at the Palace Gate towards the end of the Wuping era; Tonghui was Chamberlain for the Palace Revenues; and Tongxian held the title of Senior Recorder for Comprehensive Duty 同遊,武平末給事黃門侍郎。同迴,太府卿。同憲,通直常侍” (Bei Qi Shu 1972, p. 262). Another historical source records Tong Hui’s office as Vice Chamberlain for Ceremonials (Beishi 1974, p. 1951). Although the historical texts do not explicitly indicate the birth order of the brothers, their sequence in the record—typically following seniority—suggests that Tongyou was the eldest, followed by Tonghui and Tongxian. This assumption is overturned by the Epitaph of Yuan Nanzi, which reveals that Tongxian was in fact older than Tonghui. Furthermore, the epitaph shows that Zirui had a fourth son, whose name is illegible due to erosion on the stone. Zirui had three daughters: Yigui 宜歸, Yining 宜寧, and a third whose name is indecipherable. Yigui was married to Zheng Zheng 鄭拯 of Xingyang 滎陽.

The fourth son, Youzhi, is only briefly described in transmitted texts with the phrase: “held high office from a young age 少曆顯位” (

Bei Qi Shu 1972, p. 262). The epitaph, by contrast, specifies his actual titles as Governor of Yangping 陽平 Commandery and Founding Viscount of Pinggao 平臯 County, thereby filling a gap in the historical record. His diplomatic career included missions to the Northern Zhou and Southern Chen. After the Northern Zhou conquered the Northern Qi, Emperor Wu (r. 560–578) included Youzhi among a group of eighteen eminent scholars and officials, who were compelled to relocate to Chang’an 長安 (

Beishi 1974, pp. 1727–28). With the rise of the Sui dynasty, Youzhi was appointed Governor of Si 泗 Province. In 584, he was reprimanded for the excessively ornate style of his official documents. He eventually died in office while serving as Governor of Mei 眉 Province. His wife, from the Lu clan of Fanyang, was the daughter of Lu Daoqian 盧道虔. The

Epitaph of Yuan Nanzi lists his three sons, although the third son’s name is illegible. The puzzle is solved by the

Epitaph of Sima Shenwei 司馬慎微墓誌, which records “Great-grandfather Youzhi… Grandfather Dezhang… Father Anshang 曾祖幼之……祖德璋……父安上” (

Zhao and Zhao 2012, p. 478), thereby allowing us to identify the third son as Dezhang. This epitaph further confirms that Youzhi’s lineage continued to flourish during the Tang dynasty (

H. Zhang 2012).

Beyond the four sons previously discussed, the

Epitaph of Yuan Nanzi reveals the existence of a fifth son, Jichong 季沖. This finding is corroborated by two other sources: the

Epitaph of Sima Jichong, which records his lineage as follows: “Grandfather Long, Minister over the Masses under the Northern Wei; Father Zuan, Unequaled in Honor and Governor of Qing Province… appointed Reader-in-Waiting to the Crown Prince… His wife, from the Yuan clan of Henan, Commandery Mistress of Zhongshan, was fifth daughter of Yuan Man, who served as Minister of Works 祖龍,魏司徒公。考纂,儀同三司、青州刺史……除太子洗馬……夫人河南元氏,中山郡君,司空公蠻第五女也” (

Yin 2016, p. 206), and the

Epitaph of Sima Jichong and His Wife Yuan Kenü, which provides further details about his wife (

Yin 2016, p. 159). The discrepancy in his grandfather’s name—recorded as “Long 龍” instead of “Xinglong 興龍” in the former epitaph—can be explained by the common practice in Northern Dynasties epitaphs of using abbreviated names, possibly for parallel structure with the father’s monosyllabic name or to distinguish between formal and courtesy names. Jichong began his career as an Administrator to the Minister over the Masses. During the reign of Emperor Wenxuan (r. 550–559), he was selected to serve on the staff of the Crown Prince and was later appointed as the Governor of Hejian 河間 Commandery. His epitaph praises his clear administration and, as the tropes go, states that “savage tigers turned back and disaster locusts went away 暴虎逆移,災蝗自去.”

2 The section following the mention of Jichong’s wife in the

Epitaph of Yuan Nanzi is severely eroded. From the legible fragments, it can nonetheless be determined that Jichong had at least four sons and two daughters.

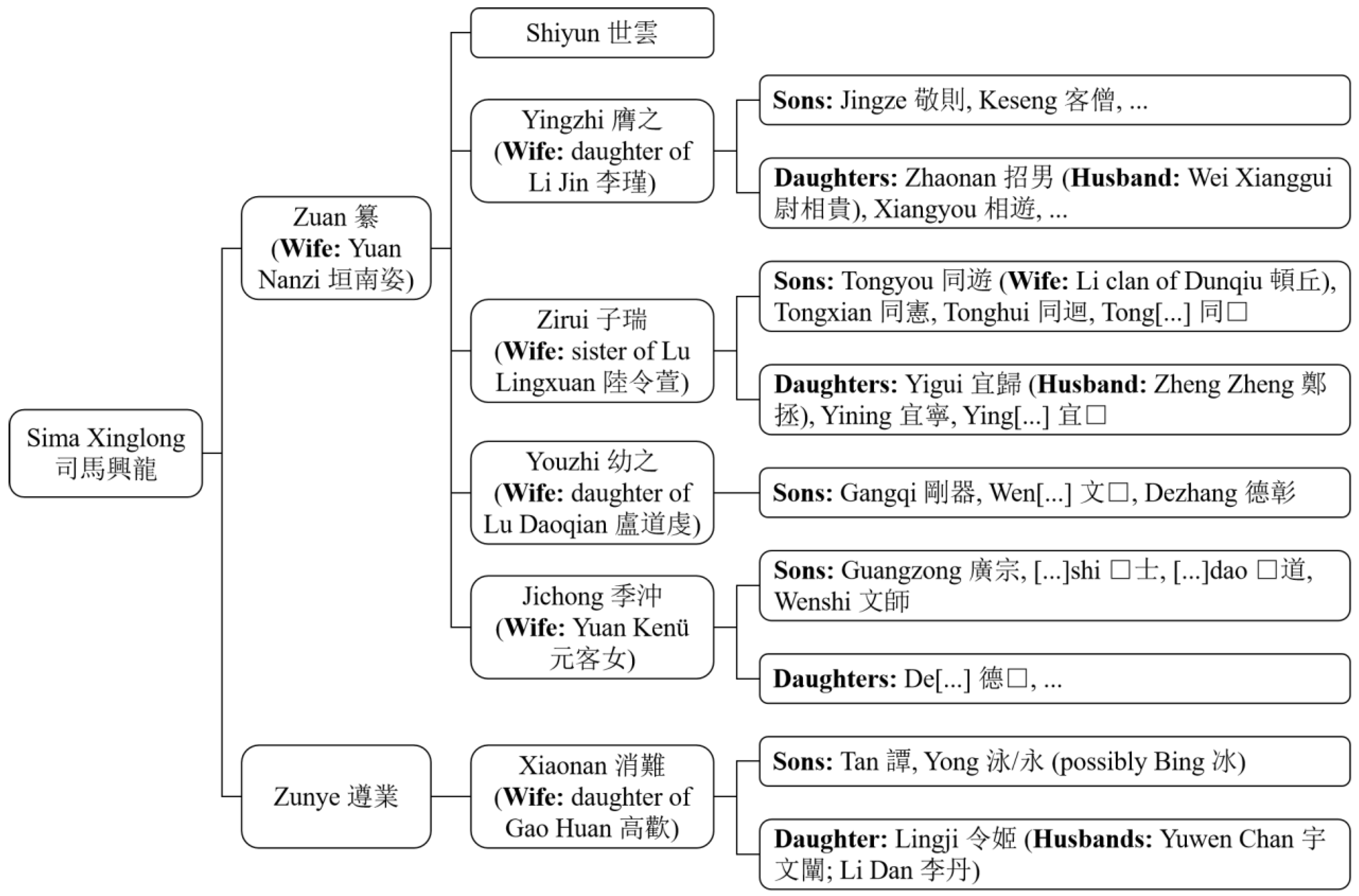

Accordingly, the lineage of Sima Xinglong’s family has been graphically reconstructed in

Figure 2. As the analysis of her sons’ careers has shown, Yuan Nanzi was a profoundly successful mother, having guided them to restore the family’s status through high-ranking positions and strategic marriages into the Han and Xianbei aristocracy, thereby establishing their prominence in the Eastern Wei and Northern Qi. It was this success, however, that created a central conflict in her life. It fostered a set of implicit social norms and pressures that made it difficult for her to readily renounce her familial responsibilities, thereby obstructing her path to becoming a bhikṣuṇī. This tension highlights the struggle between her social role as a mother and her personal religious aspirations. To fully comprehend this struggle, we must explore her inner world and personal Buddhist practice, seeking to understand how she resolved this fundamental dilemma.

4. Buddhist Faith

Beyond supplementing transmitted historical records and clarifying the lineage of Sima Xinglong’s descendants, the

Epitaph of Yuan Nanzi is also remarkable for highlighting Yuan Nanzi’s identity as a bhikṣuṇī. This implies the Yuan clan had a background in Buddhist faith. Supporting evidence comes from the Northern Qi

Votive Inscription by Jingming and Others 靜明等造像記, created in 557 to record the repair of a pagoda and the creation of a statue (

L. Wang 2025, pp. 805–7). The inscription lists 246 names, among which are 38 donors surnamed Yuan. This is, to the best of our knowledge, the only source from the early medieval China that records a significant concentration of individuals from the Yuan clan. Discovered at Mount Song 嵩山, Luoyang 洛陽, the inscription suggests that these Yuan clan were likely members of a local Buddhist pious society. Names such as “Yuan Arhat” (Yuan Luohan 垣羅漢) and “Yuan srāmaṇera” (Yuan Shami垣沙彌) more directly reflect the depth of Buddhist influence. Although a direct connection between Yuan Nanzi and these specific individuals cannot be confirmed, the inscription remains valuable as it attests to the Yuan clan’s established presence and Buddhist affiliations in the Northern Qi.

3 4.1. A Vow in Later Life

A variety of factors shaped a bhikṣuṇī’s decision to pursue ordination. Given that most Northern Dynasties epitaphs offer limited biographical detail, this study divides the reasons for bhikṣuṇī ordination into three categories: ordination in youth, husband’s death, and political changes.

4 As shown in

Table 1, among the 17 bhikṣuṇīs from the Northern Dynasties to the Sui dynasty, 9 took vows following their husband’s death or political changes, 4 were ordained in youth, and 4 remain unknown.

Ordination after a husband’s death may seem normal, but analysis shows that five of these bhikṣuṇīs were from the imperial harem, and their ordination was often linked to political change. Gao Ying, Empress to Emperor Xuanwu of Northern Wei (r. 499–515), was forced to become a bhikṣuṇī by the powerful Empress Dowager Ling 靈太后—a political outcome, not a voluntary religious choice. Wang Zhong’er was also compelled by politics to seek ordination (

Zhou 2016). Li Nansheng, Empress to Emperor Fei of Northern Qi (r. 559–560), took the tonsure to escape suffering after her husband was deposed and killed (

Liya Zhang 1997). Cao Daohong was selected for the palace due to her beauty and virtue. Based on her lifespan, she was between 9 and 37 years old during Emperor Xiaowen’s lifetime (467–499), making it highly probable she was his consort who entered the monastic life after his death. Great Consort Jia (494–544) was recorded as “Grandmother of the Prince of Langya 琅邪.” During the Eastern Wei, the only Prince of Langya was Yuan Chuo 元綽 (

Weishu 2018, p. 349); Jia was likely the wife of his grandfather Yuan Yue (476–511). She probably took vows after her husband died young. For the first three, ordination was a political necessity; for the latter two, the role of politics is less clear. This pattern is corroborated by transmitted texts. A study identifies 17 such cases, with 5 entering the order due to loss of favor or political sidelining, 8 due to an emperor’s death, deposition, or the dynasty’s collapse, and 3 for unknown reasons (

Li 2011, pp. 130–32). This evidence fully supports Chen Huaiyu’s conclusion that such ordinations were never genuine spiritual choices but a “slightly preferable alternative” to a worse fate, offering a dignified end to lives upended by power struggles (

H. Chen 2012, p. 174).

In contrast to the imperial consorts, four other bhikṣuṇīs were ordained after their husbands died under normal circumstances, without political involvement. Yuan Chuntuo, Northern Wei imperial descent, was widowed twice. After her first husband’s death, she was pressured to remarry. When her second husband also died, she eventually abandoned worldly cares and chose to become a bhikṣuṇī. Yuan Huaguang, another imperial clanswoman, was widowed in her thirties or forties (

Zhou and Wang 2019, p. 9). After experiencing the turmoil of the late Northern Wei, she went to Chang’an, where she realized the impermanence of suffering and entered the Dengjue Monastery. Similarly, Xiufan’s epitaph states that she aroused the bodhi mind after her husband’s premature death.

Yuan Nanzi constitutes a distinct variation within this group. The puzzle of her extremely late ordination at seventy-three, despite early widowhood, is resolved by her epitaph. It reveals a decades-long family conflict: resistance from her children ironically intensified her determination, culminating in her threat to secretly shave her hair. This compelled her family’s compliance, leading to her ordination in 559.

Sima Yingzhi and his brothers were not alone in opposing female ordination; many Northern Dynasties scholars shared this view. A prominent opponent was Liu Zhou 劉晝, he vehemently argued: “Bhikṣuṇīs and upāsikās essentially are wives of bhikṣus. It is indescribable how they cause miscarriages and kill infants. Currently, there are about two million bhikṣus and bhikṣuṇīs, and including lay women, the total exceeds four million. If each woman has one miscarriage every six months, then two million households are lost annually. This proves that Buddhism is a demon of abortion, utterly unlike a sage 有尼有優婆夷,實是僧之妻妾,損胎殺子,其狀難言。今僧尼二百許萬,並俗女向有四百餘萬。六月一損胎,如是則年族二百萬戶矣。驗此佛是疫胎之鬼也,全非聖人” (Guang Hongming Ji 1991, p. 133). Zhangqiu Zituo 章仇子陀, another Confucian scholar, submitted a petition during the Wuping era to restrict the number of bhikṣus and bhikṣuṇīs (Guang Hongming Ji 1991, p. 137). Confucians opposed female ordination primarily because of the large number of women involved and the perceived threat to social morality. It is important to note that as a vulnerable group, bhikṣuṇīs sometimes transgressed norms under duress. For example, when Yaoguang Monastery was invaded, the bhikṣuṇīs were violated by soldiers at the end of the Northern Wei (Luoyang Qielanji Jiaojian 2006, p. 47). Whether such violations of monastic discipline were active or passive, behavior deemed improper by secular standards easily became a target for condemnation. As officials, Sima Yingzhi and his brothers likely opposed their mother’s ordination partly due to this prevalent negative perception of bhikṣuṇīs.

In Buddhism, ordination requires more than personal determination; it must comply with the Vinaya rules. One of the “Sixteen Light Obstructing Conditions 十六輕遮” explicitly forbids ordaining anyone “without parental permission”. According to the Mahāsāṃghika Vinaya 摩訶僧祇律, translated into Chiese between 416 and 418 CE, this rule originated from the Buddha’s father, King Śuddhodana, who, heartbroken by his son’s departure, begged him to institute such a rule to spare other parents similar grief. The Buddha agreed (Mahāsāṃghika Vinaya, T22, no. 1425, p. 421). The core of this rule lies in the profound love parents bear for their children. Ordaining someone against their parents’ wishes would cause the parents great suffering, invite censure from both family and society, and thus hinder the spread of the Dharma. Although the Buddhist canon does not explicitly stipulate a rule against ordaining someone “without the permission of one’s children,” when an elderly person wishes to ordain, strong opposition from their children presents a similar ethical dilemma. From the perspective of the Mahāyāna bodhisattva path, which emphasizes “constant accommodation of sentient beings” and avoiding the creation of family discord, it is both wise and necessary to properly address the children’s concerns. Forcibly proceeding with ordination could lead the children to harbor resentment towards the Dharma. This was likely a significant concern for Yuan Nanzi, explaining why she patiently sought her family’s understanding for years. It was only when decades of persuasion failed that she issued her forceful threat, finally securing their necessary, albeit reluctant, consent.

Age constitutes another regulatory factor for ordination. Beyond the well-known minimum age of twenty for full ordination, Buddhist texts specify other age-based disqualifications. The Mahāsāṃghika Vinaya stipulates that individuals over seventy were generally barred from ordination, as they were deemed incapable of serving the community and required care from others. An exception was made only for those who, despite reaching this age, were exceptionally healthy and capable of religious practice (Mahāsāṃghika Vinaya, T22, no. 1425, p. 418). The story of Subhadda 須跋陀羅, preserved in the Mahāparinibbāna Sutta 大般涅槃經 and the Saṃyukta Āgama 雜阿含經, offers a scriptural example that transcends normative age limits. Subhadda, a brilliant Brahmin ascetic of Kuśinagara, had attained the five spiritual powers yet remained tormented by a lingering unrest. When news arrived that the Buddha was nearing parinirvana, the 120-year-old man resolved to seek his final teaching. Deeply moved by the elder’s determination, the Buddha ordained him that night (Mahāparinibbāna Sutta, T1, no. 7, pp. 203–204; Saṃyukta Āgama, T2, no. 99, p. 254). This case presents a notable exception to the age restriction: Subhadda’s arduous journey proved his physical competence, while his intelligence and devotion affirmed his capacity for practice, justifying his ordination as the Buddha’s final disciple.

At 73, Yuan Nanzi undoubtedly exceeded this age limit. Her epitaph, however, confirms that she was mentally sharp and devout, justifying an exception. Female ordination in later life was rare in this period. A study of 152 bhikṣuṇīs with 39 known ages found only two over 60 (

Le Zhang 2013, pp. 21–22). Fasheng 法盛, originally from Qinghe, sought ordination after being displaced south by warfare, finding in Buddhism a way to dispel sorrow and forget the burdens of old age (

Biqiuni Zhuan Jiaozhu 2006, p. 48). Pei Zhi’s 裴植 mother Xiahou 夏侯 also ordained after the age of seventy (

Weishu 2018, p. 1706). Adding Yuan Nanzi, who was not in the study, makes her the oldest known bhikṣuṇī from that era. Research indicates that religious belief can significantly enhance well-being for the elderly (

Argyle 2000, p. 21). This likely motivated Yuan Nanzi. After a hard life of early widowhood and raising five sons alone, she probably sought spiritual comfort in Buddhism to fill the existential void of her later years.

The Epitaph of Yuan Nanzi reveals that her ordination was not only ceremonially grand but also canonically impeccable. She underwent the “dual-saṃgha ordination 二眾戒,” a rigorous procedure requiring the participation of ten bhikṣus and ten bhikṣuṇīs to confer full monastic precepts. Only through this process can one be considered to have strictly received the upasaṃpadā 具足戒. Jing Jian 淨檢 of the Eastern Jin dynasty is often considered the first bhikṣuṇī in China. In fact, as there were no bhikṣuṇīs at that time, she received her precepts “from a single saṃgha 從一眾”, meaning she was ordained by ten bhikṣus only. Consequently, some regard Hui Guo 慧果 of the Southern Song dynasty as the first true bhikṣuṇī. By Yuan Nanzi’s era, Buddhism’s established presence made convening the requisite twenty ordinators a simple matter. Thus, her ordination unequivocally met the highest Vinaya standard, underscoring its legitimacy and the formal recognition of her monastic status.

4.2. Faith at Home

As a religion that emphasizes renunciation of the world, Buddhism requires that fully ordained bhikṣus and bhikṣuṇīs abandon secular life, leave their families, and devote themselves to practice within monastic communities. Early Indian Buddhism posited an irreconcilable dichotomy between the monastic life and secular obligations (

Gross 1993, p. 274). By the medieval period in China, however, there existed fully ordained bhikṣus and bhikṣuṇīs who chose to reside with their secular families. This phenomenon should be distinguished from both the committed lay Buddhists (upāsakas and upāsikās), who observe the Three Refuges 三皈依 and the Five Precepts 五戒 while maintaining their familial and social duties, and from ordinary devotees who engage in domestic piety such as maintaining a vegetarian diet and chanting. Since these lay categories do not undergo formal ordination, they fall outside the focus of this study.

The Epitaph of Yuan Nanzi offers a pertinent case study, documenting a bhikṣuṇī who engaged precisely in such home-based monastic practice. Yuan Nanzi’s fierce vow—“If you do not permit me to enter the monastic life, I shall secretly shave my hair, leaving you with endless regret”—and the formal ordination that ensued demonstrate her sincere determination to leave secular life. Nevertheless, the rite took place in her family’s central courtyard rather than a monastery, and she does not seem to have resided later in a monastery. On the contrary, after years of separation from her fourth son, Youzhi, she was received into his commandery. Such evidence points to an unresolved tension in Yuan Nanzi’s life: though determined to ordain, she was still entangled in worldly bonds, practicing a hybrid path that blurred the lines between a bhikṣuṇī and an upāsikā—fully ordained, yet faith at home.

This apparent contradiction was, in fact, a common pattern at the time. For instance, Yuan Chuntuo died in a detached lodge in Xingyang Commandery, and her funeral was arranged by her secular children, indicating that she likely practiced at home in her later years. Yuan Huaguang and her niece ordained at a monastery close to their family home (

Fu 2019, p. 419), suggesting they probably did not reside permanently in the monastery but frequently returned home. A study of 23 epitaphs shows that in over 60% of cases, bhikṣuṇīs lived near their homes, reflecting the enduring influence of Confucian family values (

M. Zhang 2012).

It is true that the Buddhist advocacy of leaving home and abandoning familial ties was fundamentally at odds with the traditional Chinese values like filial piety. Recognizing that reconciliation was essential for Buddhism’s widespread acceptance, early monks translated Buddhist texts to align with Confucian ethics (

Fang 1988, pp. 259–63). Consequently, this process of sinicization gradually mediated the inherent contradiction between monastic renunciation and secular engagement. The

Vimalakīrti Nirdeśa Sūtra 維摩詰經, an immensely popular Buddhist text during the Six Dynasties—especially among powerful aristocratic families—helped dissolve the rigid dichotomy between Nirvana and the mundane world (

Vimalakīrti Nirdeśa Sūtra, T14, no. 475, p. 551). The sutra teaches that once one’s understanding is elevated to the wisdom of Mahayana, Nirvana and the secular world cease to be distinct (

Yao 1998). This provided the theoretical justification for bhikṣus and bhikṣuṇīs to practice “faith at home”. Yuan Nanzi’s domestic practice represents the practical resolution of this theoretical synthesis. Her advanced age and need for care made residence in a monastery impractical, while the years of family opposition made a compromise necessary. Her home-based religious life thus stands as a vivid illustration of the negotiated settlement between Buddhist ideals and Chinese familial imperatives.

Despite her late ordination, Yuan Nanzi was deeply committed to Buddhist rites. Her epitaph records that “Whenever Dharma events were held on the new and full moons, she would personally ascend the high seat to expound the precepts for the assembly”, which refers specifically to the Buddhist poṣadha 布薩 ceremony. The

Sarvāstivāda Vinaya 十誦律 states the following:

“The Buddha instituted the poṣadha so that monks, gathering fortnightly, may examine their conduct—asking what offenses they committed by day or by night—and confess any transgressions to a pure-vinaya fellow monk or resolve to do so later if one was unavailable. Why then did the Buddha institute this practice? The answer is that it enables the monks to abide in wholesome Dharma, abandon the unwholesome, and thereby attain purity. This is the poṣadha method 半月半月諸比丘和合一處,自籌身量,晝作何罪?夜作何罪?從前說戒以來,將不作何罪耶?若有罪,當向同心淨戒比丘如法懺悔。若不得同心淨戒比丘,當生心,我後得同心淨戒比丘,當如法懺悔。問何以故佛聽作布薩? 答令諸比丘安住善法中,舍離不善離不善法得清淨故,是名布薩法.”

(Sarvāstivāda Vinaya, T23, no. 1435, pp. 414–15)

Thus, poṣadha refers to the fortnightly assembly of fully ordained monastics who examine their conduct against the precepts. By insisting on participating in the poṣadha ceremony, the aged Yuan Nanzi demonstrated an exceptional level of dedication that commanded admiration.

Furthermore, her commitment extended beyond personal discipline into active compassion. The epitaph notes that she distributed her worldly goods, which reflects a life shaped by the Buddhist virtues of the Mahayana ideal, including selfless giving and the pursuit of merit. The Mahāprajñāpāramitā Śāstra 大智度論 points out: “Great loving-kindness gives to sentient beings through the cause of joy; great compassion gives to sentient beings through the cause of relieving suffering 大慈以喜樂因緣與眾生,大悲以離苦因緣與眾生” (Mahāprajñāpāramitā Śāstra, T25, no. 1509, p. 256). The motivation for Buddhist devotees to actively engage in philanthropy stems precisely from this ideology of taking the salvation of all beings as their responsibility. They believe that by contributing to social welfare activities to the best of their ability, they both accumulate merit and enhance their own karmic fortune.

4.3. Burial in the Clan Cemetery

The localization of Buddhist practice in China extended to funerary rites. Although Indian tradition mandated monastic funerals organized by the saṃgha, in early medieval China, bhikṣuṇīs could be buried either by the monastic community or the secular family (

X. Shi 2023, pp. 30–33), reflecting a hybrid of imported and native customs. Yuan Nanzi’s burial epitomizes the Sino-Buddhist synthesis. Her death from grief following her son’s passing affirms her Confucian familial bonds. However, her epitaph records a final wish for an ascetic burial without a coffin, a practice grounded in Buddhist tenets. Her sons’ adherence to these wishes, despite their unconventionality, demonstrated that her biological family, not the monastic disciples, held ultimate responsibility for her funeral, thereby highlighting the complex negotiation between Buddhist ideals and Confucian familial duty.

The Epitaph of Yuan Nanzi reveals her deep ties to her secular family not only through the narrative tone of the text, authored by her sons, but also in its formal title. Northern Dynasties epitaphs for bhikṣuṇīs typically followed a “Monastic Name + Monastery Name” format, such as Wei Epitaph of the Bhikṣuṇī Ciyi of Yaoguang Monastery 魏瑤光寺尼慈義墓誌銘, Epitaph of the Bhikṣuṇī Farong of Zhenglu Monastery 征虜寺比丘尼法容銘, Epitaph of the Bhikṣuṇī Hua of Dengjue Monastery in Yong Province 雍州等覺寺比丘尼僧華墓誌, and Sui Epitaph of the Bhikṣuṇī Nati of Zhenhua Daochang大隋真化道場尼那提墓誌之銘. Sometimes the monastery name was omitted, such as Sui Epitaph of the Bhikṣuṇī Yuan Huaguang 隋比丘尼元華光墓誌 and Late Epitaph of the Bhikṣuṇī Shi Xiufan 故比丘尼釋修梵石室志銘並序. Those who held the office of bhikṣuṇī directress would include that title, such as Late Wei Epitaph of the Bhikṣuṇī Directress Master Shi Sengzhi 魏故比丘尼統法師釋僧芝墓誌銘. As for Yuan Nanzi, however, her epitaph is titled: Late Qi Epitaph of the Sima’s Grand Matron Bhikṣuṇī Yuan 齊故司馬氏太夫人比丘尼垣墓誌之銘. This pattern creatively merges the standard Chinese epitaph format for elite women—which prefaced her surname with her husband’s clan—with her religious identity, inserting “bhikṣuṇī” between the two. Thus, a unique formulation “Husband’s Clan + Bhikṣuṇī + Deceased’s Surname” was produced, representing a tangible compromise: a hybrid identity crafted by her family that acknowledged her religious vows without erasing her foundational role within the Sima lineage.

Three other epitaphs share this distinctive formulation: Late Wei Epitaph of the Chariot and Horse General and Duke of Pingshu Wending Xing’s Successor Wife Bhikṣuṇī Yuan of Dajue Monastery 魏故車騎大將軍平舒文定邢公繼夫人大覺寺比丘元尼墓誌銘並序, Wei Epitaph of Minister of Works, Chief Minister for Imperial Sacrifices and Duke of Pingyi Jianmu’s Second Daughter Bhikṣuṇī Yuan 魏司空公尚書令馮翊簡穆王第二女比丘尼元之墓誌, and Late Qi Epitaph of Prince of Jinan Mindao’s Consort Bhikṣuṇī Li 齊故濟南湣悼王妃李尼墓銘. Though the second example replaces the husband’s information with the father’s, it still emphasizes the woman’s natal family. Both bhikṣuṇīs of the Yuan shared the common feature of practicing at home, suggesting that this titling style was characteristic of bhikṣuṇīs who did not reside in a monastery. The exception, Li Nansheng, is explained by her unique background as a former imperial consort, highlighting the couple’s imperial identity was necessary. This explanation is reinforced by the contrasting case of Gao Ying, another bhikṣuṇī consort who lacked the imperial identity; having been deposed from her rank and buried with Buddhist rites (Beishi 1974, p. 502), she was thereby rendered ineligible for such a designation.

In India, the primary funeral methods for Buddhists were cremation and open-air burial. After Buddhism was transmitted to China, these two funerary practices also gradually became popular among Chinese Buddhists. Open-air burial, which entailed exposing the body in nature or water without a coffin, was based on the doctrine of dāna 布施. In India, open-air burial included forest burial and water burial, in early medieval China, forest burial emerged as the predominant form. The subsequent treatment of the bones followed one of three modes: collection for burial or stūpa interment; cremation followed by burial or stūpa interment; or the scattering of ashes (

S. Liu 2008, pp. 183–93). The statement that “even a fitting coffin was not her wish” confirms that Yuan Nanzi also adopted open-air burial. Certainly, her sons collected and buried her remaining bones, though it remains unclear whether this aligned with the first or the second method. During early medieval China, the prevalent practice of forest burial was closely associated with the Three-stage School of Buddhism 三階教, a Buddhist branch potentially originating in Ye during the Northern Qi (

Tokiwa 1938, pp. 181–98). A distinctive feature of this group was its non-discrimination between monastics and laity, or men and women (

Tsukamoto 1975, pp. 209–50). Precisely because women were a primary focus of its missionary efforts, female Buddhist devotees in this era often adopted open-air burial, particularly among the high nobility. Yuan Nanzi serves as an example of this trend.

Apart from funerary methods, bhikṣuṇīs also had relatively fixed burial locations in this period, typically near monasteries or famous mountains. Burial within a monastery indicated that the bhikṣuṇī was a revered master, who was interred there after death in order to receive veneration from the saṃgha. For instance, Daorong 道容 of Xinlin 新林 Monastery was honored by Emperors Ming (r. 323–325), Jianwen (r. 371–372), and Xiaowu (r. 372–396) of the Eastern Jin. Records note that “during the Taiyuan 太元 era (376–396), she suddenly disappeared, and her whereabouts were unknown. The emperor ordered her robe and alms bowl to be buried; hence, there is a tomb mound beside the monastery 太元中,忽而絕跡,不知所在。帝勅葬其衣缽,故寺邊有塚云” (

Biqiuni Zhuan Jiaozhu 2006, p. 28). Those buried near famous mountains were typically interred at Mount Mang 邙山 in the north and Mount Zhong 锺山 in the south, which signified high esteem and connections to the court (

X. Shi 2023, pp. 33–34). These practices demonstrate that bhikṣuṇīs had already established distinctive burial grounds by that time.

Yuan Nanzi, however, was buried neither in a monastery nor on a famed mountain, but “seven miles northwest of Ye at Zimo”. This area was likely the Sima clan cemetery of the Eastern Wei-Northern Qi branch. Evidence for this includes the burial of Sima Zunye, who was interred “to the left of the hill, fifteen miles northwest of Ye” (

L. Wang 2021, p. 640). Furthermore, Zunye relocated his father Xinglong’s remains to “the southern side of the earthen hill at Pinggang 平岡, fifteen miles northwest of Ye and five miles southwest of Fuyang 釜陽 City” (

L. Wang 2021, p. 532). Yuan Kenü, who predeceased her husband Jichong, was initially laid to rest “three miles west of Zimo and north of Wucheng 武城” (

Yin 2016, p. 159). This conscious choice to be laid to rest among her husband’s kin—whether directly instructed by her or willingly executed by her sons—serves as the ultimate earthly confirmation of her unique religious path, representing the final chapter of her monastic practice as “faith at home.”

A similar case is that of the aunt-niece pair Yuan Huaguang and Yuan Yuanrou. Yuan Huaguang was first buried in Jiqian 吉遷 Village, Honggu 鴻固 District, Wannian 萬年 County, Jingzhao 京兆 Commandery. In 582, she was reinterred, and her epitaph was re-engraved when she was jointly buried with her niece Yuan Yuanrou in the Duling 杜陵 Plain. Yuan Huaguang’s sister-in-law, Li Zhihua 李稚華, had been buried in the Xiaoling 小陵 Plain in 564. The Duling Plain, Honggu Plain, Xiaoling Plain, and Shaoling 少陵 Plain all refer to the same area (

Fu 2019, p. 419), meaning their burial sites lay in close proximity. This deliberate clustering of tombs underscores how their monastic lives remained in continuous dialog with their familial identity.

Some bhikṣuṇīs, however, who practiced “faith at home” were nevertheless buried separately from their families. A case in point is Yuan Chuntuo. Her epitaph records: “On her deathbed, she was clear-minded and entrusted her final wishes, instructing that she be buried separately to fulfill her desire for cultivating the Dao. Her children respectfully complied, not daring to disobey her command. On the seventh day of the eleventh month, they interred her in the sunny side of the small Saddle Hill, southwest of Mount Mang, fifteen miles northwest of Luoyang City 臨終醒寤,分明遺托。令別葬他所,以遂修道之心。兒女式遵,不敢違旨。粵以十一月戊寅朔七日甲申,蔔窆於洛陽城西北一十五裏芒山西南,別名馬鞍小山之朝陽” (

L. Wang 2021, p. 392). The epitaph of her husband, Xing Luan, has also been unearthed, stating he was “reburied and joined with the ancestral tomb” (

L. Wang 2021, p. 122).

Epitaph of Xing Wei 邢偉墓誌 notes that they were buried on the same day “to the right of the tomb of the Duke of Chariot and Horse (i.e., Xing Luan) in the Chongren 崇仁 Village, Yonggui 永貴 District, Wuyuan 武垣 County” (

L. Wang 2021, p. 121). The location was clearly the Xing clan’s ancestral cemetery. This confirms that Yuan Chuntuo was indeed buried apart from her husband. Such a decision can be read as a definitive renunciation of secular bonds, born from a life she herself described as full of hardship.

These divergent choices in burial practice highlight a fundamental duality. For bhikṣuṇīs living in the world, the funeral became the final arena where the balance between monastic detachment and familial attachment was negotiated. Whether integrated into the clan cemetery or set apart in a solitary grave, the decision, made by herself or her family, mirrored the complex negotiation between her religious renunciation and her secular embeddedness.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Yuan Nanzi’s life was inextricably linked to the rise and fall of the Sima clan in the Eastern Wei and Northern Qi. Her early marriage into the clan was followed by severe adversities: her husband’s premature death and her eldest son’s rebellion. Facing these crises, she displayed superb managerial abilities, sustaining the household and guiding her sons to adulthood, thereby reviving the family’s standing. Although she fulfilled her aspiration to become a bhikṣuṇī in her later years, her choices—such as taking vows in later life, practicing her faith at home, and being buried in the clan cemetery—collectively present a distinctive pattern of “having left the household yet not the secular world.” Yuan Nanzi’s case demonstrates that the religious life of a bhikṣuṇī in the Northern Dynasties was not confined to the model of residing in monasteries and severing worldly ties; it also encompassed a path that integrated religious pursuits with familial responsibilities.

By the Tang dynasty, Li Yuan 李淵, Emperor Gaozu (r. 618–626), issued an edict to purify the Buddhist and Daoist communities, stating that “all bhikṣus, bhikṣuṇīs, Daoist priests, and Daoist priestesses who are diligent in practice and uphold the precepts shall be permitted to reside in major temples and monasteries, provided with clothing and food, and shall not be left in want. Those who cannot be diligent, whose conduct is deficient in precepts, and who are unworthy of support, shall all be defrocked and sent back to their native places 諸僧、尼、道士、女冠等,有精勤練行、守戒律者,並令大寺觀居住,給衣食,勿令乏短。其不能精進、戒行有闕、不堪供養者,並令罷遣,各還桑梓” (

Jiu Tang Shu 1975, p. 17). This reveals the imperial intention to restrict sanctioned monasticism to those who could rigorously uphold its discipline. Similarly, one of the primary aims of Emperor Taizong’s (r. 627–649)

Regulations for the Daoist and Buddhist Clergy 道僧格 was to limit clerical engagement in secular life, reinforcing the expectation that they should conduct their devotions within temples and monasteries (

Weinstein 1987, p. 21). Despite these state-sanctioned ideals, the model of “faith at home” that had developed since the Northern Dynasties became even more prevalent. Some bhikṣuṇīs not only participated in family affairs and commissioned statues to transfer merit for deceased relatives but also, like Yuan Nanzi, resided with their natal families and were buried in the clan cemetery. Building upon existing research, this study classifies three representative patterns below to reveal the spectrum of variation within this practice.

The first pattern consists of bhikṣuṇīs whose practice was defined by the principle of locational freedom. They held that true devotion was a matter of inner purity, not physical seclusion in a monastery, thus justifying their choice of domestic monasticism. A prime example is Zhengxing 正性. Although she had been fully ordained for twenty-three years, she passed away at home and was buried in the clan cemetery. Her epitaph makes this doctrinal justification explicit: she often stated that “purity is of the mind, and a mind that is pure is always liberated. Therefore, in life, I do not reside in a monastery 清淨者心,心常解脫,故生不居伽藍之地” (

Zhou and Zhao 1992, p. 1858). This belief that sincere piety transcends geographical constraints directly resonates with the ideals found in Buddhist scriptures such as the

Vimalakīrti Nirdeśa Sūtra, as discussed previously.

The second pattern identified is that of bhikṣuṇīs who practiced “faith at home”— which, as in the case of Yuan Nanzi, appears to have been a compromise between their religious commitment and family responsibilities. Consider the case of Kongji 空寂. Her epitaph records that she took the tonsure and robes at fifteen against her father’s wishes, died at home at fifty-two, and was later buried beside her father’s grave (

Zhou and Zhao 2001, p. 569). While it is uncertain whether she received full ordination, the paternal opposition she faced mirrors Yuan Nanzi’s circumstances. This suggests that her domestic life and burial arrangement were similarly a practical compromise between her faith and her family. The challenges these women faced are echoed in the

Mūlasarvāstivāda Vinaya Kṣudrakavastu 根本說一切有部毘奈耶雜事, translated into Chinese in the early 8th century, which contains the story of Fayu 法與, who persevered through an arranged marriage and intense familial opposition to become fully ordained (

Mūlasarvāstivāda Vinaya Kṣudrakavastu, T24, no. 1451, pp. 366–69). By enshrining such stories, the Vinaya provided normative support and a powerful narrative for medieval women seeking liberation despite societal and familial obstacles.

The third pattern of bhikṣuṇīs demonstrates how their initial motivations for ordination were deeply rooted in familial obligations, thereby making it inevitable that their post-ordination lives remained closely tied to their families. This is vividly illustrated by Bianhui 辯惠, who was ordained specifically to generate posthumous merit for her deceased grandmother (

Zhou and Zhao 2001, p. 657). Thus, it is entirely reasonable that she maintained strong connections with her natal family after ordination and eventually died at home. Another illustrative example is Yixing 义性, who returned home to care for her orphaned siblings and manage the household after her parents’ death (

Zhou and Zhao 1992, p. 1942). Such cases were nurtured by the unique social environment of the Sui and Tang dynasties, characterized by the deepening fusion of filial piety with Buddhist doctrine. The

Classic of Filial Piety 孝經 was required reading for the imperial examinations, and offenses such as “contumacy 惡逆”, “lack of filial piety 不孝”, “discord 不睦”—which were included in Ten Abominations 十惡—were treated as grave crimes. Emperor Taizong condemned clerics who “arrogantly exalt themselves and accept obeisance from their parents 妄自尊崇,坐受父母之拜” as corrupting customs and violating the classical rites (

Zhenguan Zhengyao 2011, p. 498). Emperor Gaozong (r. 650–683) subsequently issued an edict compelling clerics “to fully observe the rites and bow to their parents 盡禮致拜其父母” (

Jiu Tang Shu 1975, p. 83). In response, Buddhists reconceptualized monastic discipline as the ultimate expression of filial devotion. They posited a critical distinction between a “lesser filiality,” which involved supporting one’s parents materially, and a “greater filiality,” which sought to liberate them from suffering in the Six Realms 六道 through spiritual means. This ideological fusion found explicit expression in texts such as Li Shizheng’s 李師政

Essay on Inner Virtue 內德論, which proclaims, “the teaching of the Buddha encourages ministers to be loyal, sons to be filial, states to be well-governed, and families to be harmonious 佛之為教也,勸臣以忠,勸子以孝,勸國以治,勸家以和” (

Guang Hongming Ji 1991, p. 195). The promotion of this hybrid virtue was further advanced through apocryphal scriptures like the

Mātpitguānupālanasūtra 父母恩重難報經 and the

Brahmajāla-sūtra 梵網經. Consequently, the Confucian ethos of filial piety left a deep imprint not only on Buddhist doctrine but also on literature, painting, music, sculpture, and other art forms (

Wei 1985, p. 21).

When we compare Yuan Nanzi with the three types of Tang bhikṣuṇīs, it becomes evident that she embodied a direct prototype for the diverse motivations—whether practicing regardless of location, negotiating compromises, or fulfilling filial duties—that would later manifest as distinct patterns. Her lifetime in the late Northern Dynasties coincided with a pivotal phase of synthesis between Buddhist philosophy and indigenous Chinese clan-based ethics. This synthesis gave rise to a sinicized Buddhism that fundamentally shaped ordained women’s perspective on family, compelling them to maintain strong familial ties despite their formal renunciation. This reflects what scholars term the “sentimentalization and rationalization” of Buddhist precepts in China, where monastic rules were flexibly applied to accommodate traditional norms (

Yan 2004, p. 101). Consequently, Yuan Nanzi’s religious life represents an early and successful adaptation of Buddhism to the powerful familial structure of Chinese society. Her case not only presaged the broader clerical secularization of the Tang dynasty but also served as a pivotal case study for observing both the continuities and the distinctive phases of Buddhist secularization from the Northern Dynasties through the Sui and Tang eras.