1. Introduction

Yunnan is located on China’s southwest border, far from the central government. Many ethnic minorities inhabit this region, and have been deeply enriched by Han culture 漢文化 since the Han dynasty 漢朝 (206 BCE–220 CE). In the Jinning 晉寧 area of Kunming 昆明, the gold “Seal of the King of Yunnan” represents about five thousand bamboo slips in the first-century Chinese language. They contain two fragments of the Analects of Confucius

論語, and nearly 2000 Chinese seals have been found from the late 2nd century BC.

1 Although Yunnan was ruled by the Cuan 爨氏 family during the WeiWei 魏 (220–266), Jin 晉 (266–420), and Southern and Northern dynasties 南北朝 (386–589), from the local carved “Cuan Baozi Stela” 爨寶子碑 and “Cuan Longyan Stela” 爨龍顏碑,

2 the writing of the two inscriptions in Chinese is extremely smooth, and many places are mentioned, such as “Zhuo Er Bu Qun” 卓爾不群 and “Wan Li Gui Que” 萬里歸闕. Of note is the skilled use of ancient Chinese rhetorical devices and the use of the dating system of the Central Plains dynasties; enough to show that, in the medieval split period of China, Yunnan was still deeply embedded in Han cultural domination. After the 7th century, under the support of the Tang dynasty, Nanzhao 南詔 (738–902)—a local government in Dali 大理, Yunnan Province—was established. For geopolitical reasons, the original intention of the Tang dynasty 唐朝 (618–906) was to unify the scattered regimes in Yunnan, so as to contain the expansion of the Tubo (Tibetan) regime 吐蕃 (633–842) and reduce its threat to the Tang dynasty. However, this development led Yunnan to diverge from its original local government structure and evolve into a local indigenous regime, which undoubtedly created latent risks for the future Dali Kingdom (937–1254) of Nanzhao by contributing to the prolonged separation of local governance. Even so, Han culture had already penetrated Yunnan at this time; during the Nanzhao and Dali periods, Chinese was still the only common language in Yunnan, and Chinese culture was still the culture that the local government most respected and actively absorbed and learned. After the Yuan dynasty, Yunnan returned to China’s unified official management system, which prepared the basic political system for the comprehensive introduction of Han immigrants and Han culture after the Ming dynasty. After the Ming dynasty 明朝, the central government accelerated the speed of Sinicization of Yunnan, and Yunnan was further Sinicized, achieving comprehensive Sinicization until the early Qing dynasty 清朝.

Although the indigenous people of the Yunnan region had long been making efforts to ensure regional cultural characteristics, by the mid-16th century—at least, after the fall of the Wu Sangui regime 吳三桂政權 (1673–1681)—Yunnan had indeed been fully integrated into Chinese culture. In this process of Sinicization, Yunnan fully studied and absorbed Chinese Buddhism. In addition to the study of the Chan 禪 teachings, the system of Yixue 義學 Doctrinal studies, and the esoteric classics 密教經典, the request for printing the CBC elsewhere and the collection of the CBC are also important events worthy of attention.

2. A Summary of the Requests for the Printing of the CBC in Yunnan During the Song, Yuan, and Ming Dynasties

Buddhism in Yunnan during the Ming, Song, and Yuan dynasties was two-sided: on the one hand, local Buddhism developed and formed typical local Buddhism—Dali Esoteric Buddhism 大理密教;

3 on the other hand, Chinese Buddhism was gradually accepted, and Chinese Buddhist classics gradually spread in Yunnan. An important event of CBC dissemination was the collection and dissemination of Chinese classics in Yunnan.

The earliest known Chinese printed version of the CBC is the

Kaibao Canon 開寶藏, which was engraved in Chengdu during the Kaibao period 開寶時期 (968–976) of the Northern Song dynasty 北宋 (960–1127). Subsequent versions such as the

Qidan Canon 契丹藏, the

Jin Canon 金藏, and the

Gaoli Canon 高麗藏 were all based on the system established by the

Kaibao Canon. At the end of the Northern Song dynasty, the first privately printed Chinese CBC, the

Chongning Canon 崇寧藏 (also known as the

Dongchan Dengjue Chan Si Canon 東禪寺藏 or the

Fuzhou Canon 福州藏), was engraved in the Dongchan Dengjue Chan Temple in Fuzhou, southern China. Influenced by this CBC, the Kaiyuan Chan Temple in Fuzhou also engraved another Fuzhou version of the CBC, the

Pilu Canon 毗盧藏. These two CBC editions marked the beginning of the southern system of the Chinese printed CBC. Subsequently, the

Sixi Canon 思溪藏was completed in Huzhou, Zhejiang Province, 浙江省湖州. During the late Southern Song dynasty and the Yuan dynasty, the

Qisha Canon 磧砂藏 and the

Puning Canon 普寧藏 were engraved in the southeast of China. In the second year of the Zhiyuan period 至元二年 (1336) of the Yuan dynasty, an official version of the CBC was engraved in the Hangzhou area, which was later named the

Yuan Official Canon 元官藏 (

Tong et al. 1984). During the Ming dynasty, four major CBC collections were also engraved: the First Edition of the Southern CBC, the

Yongle Southern Canon 永樂南藏, the

Yongle northern Canon 永樂北藏, and the

Jiaxing Canon 嘉興藏. Looking back at the engraved CBC collections that have survived from the Song, Yuan, and Ming dynasties, most of them are collected in the Yunnan region. It can be said that Yunnan is one of the most remote regions in China where these collections have been disseminated and are most richly preserved. Therefore, investigating the CBC collections engraved during the Song, Yuan, and Ming dynasties and introduced in Yunnan is undoubtedly of great value.

As far as is known, more than six sets of different editions of the CBC from the Song, Yuan, and Ming dynasties have been introduced in Yunnan. Regarding the collection of the literary Chinese CBC in Yunnan, as records show, research has been carried out by scholars of previous and later generations. The main aspects involved are the earliest printing and collection of the CBC in Yunnan.

Regarding the earliest research on the printing of the CBC of Buddhism in Yunnan, it mainly focused on the “

Sixi Canon theory (思溪說)” in the mid-to-late 20th century. The Yunnan scholar Zhou Yongxian 周泳先 believed that there were 31 volumes of the CBC in the Yunnan Provincial Library of the

Sixi Canon (

Zhou 2022, pp. 422–432), which influenced subsequent judgment on this batch of the CBC. At present, it seems that this batch of the CBC should be the

Yuan Official Canon. The book

Nanzhao Unofficial History 南詔野史 mentioned that the earliest request for the printing of the CBC in Yunnan was during the reign of Duan-Zhilian 段智廉 (r. 1201–1204) of the Dali Kingdom:

“Duan-Zhilian ascended the throne in the first year of the Qingyuan era 慶元元年 of the Gengshen period 庚申年 of the Southern Song Dynasty. The name of the reign period was changed to Fengli 鳳曆 in the following year. It was changed to Yuan Shou 元壽 again. He sent people to the Song Dynasty to request 1465 works of the CBC and housed them in the Wuhua Tower.”

“段智廉,南宋庚申慶元元年即位。明年,改元鳳曆。又改元元壽。使人入宋求《大藏經》一千四百六十五部,置五華樓”

The current uncertainty lies in the fact that we are not sure when the batch of this CBC was first brought to Yunnan. In terms of time, two sets of CBCs came to Yunnan probably around the year 1202AD; namely, the

Sixi Canon completed in 1132–1138 and the

Pilu Canon 毗盧藏 completed in 1151. Among them, the

Pilu Canon has the closest completion time to this request time. According to

Nanzhao Unofficial History, the total number of CBCs requested for printing was 1465 titles. Compared with the main CBCs completed during the Southern Song dynasty, the

Chongning Canon had 1451 titles, the

Pilu Canon had 1452 titles, and the

Zifu Canon 資福藏 had 1419 titles (

Li and He 2003, pp. 171, 208). Among them, the

Pilu Canon had the closest number of units to this request number; therefore, this batch of the Great Canon of Buddhism might be the

Pilu Canon. However, the CBC that was brought back based on this request might not have been preserved. To date, no paper has been found, nor has there been any evidence of the existence of a unit of the

Pilu Canon in Yunnan. There is also no record in the existing literature. Therefore, it can only be speculated that the first batch of the CBC brought back to Yunnan was the

Pilu Canon, but this cannot be regarded as a definite conclusion.

From the Yuan to the Ming dynasty, more than 20 sets of the CBC of the Song–Yuan–Ming dynasties were possibly introduced to Yunnan. Currently, there are approximately seven extant versions, including the Qisha Canon, Puning Canon, Yuan Official Canon, Hongfa Canon 弘法藏, Yongle Southern Canon, Yongle Northern Canon, and Jiaxing Canon. These extant Canons are all in separate volumes and do not have complete sets. As far as is known, approximately three sets of the Qisha Canon, three sets of the Puning Canon, two sets of the Yuan official Canon, one set of the Hongfa Canon, one set of the Yongle southern Canon, two sets of the YongLe northern Canon, and three sets of the Jiaxing Canon have survived.

The Qisha Canon was published in the ninth year of Jiading 嘉定九年 during the reign of the Southern Song dynasty (1225) and was completed in the second year of Zhizhi 至治二年 during the reign of the Yuan dynasty (1322). According to official data, the Yunnan Provincial Library holds two titles of the Qisha Canon, and the same number of volumes and folios. The library made these announcements in 1978 and 2009, respectively. However, there are discrepancies in such numbers in the Buddhist literature, as the library announced on these two occasions. The number of surviving works is not discussed herein. It is more important to highlight that some Buddhist texts of these Canons are kept in the hands of individuals in Yunnan.

The Puning Canon 普寧藏 was engraved in the second year of Jingyan 景炎二年 in the period of the Southern Song dynasty (1277) and was completed in the 27th year of Zhiyuan 至元二十七年 in the period of the Yuan dynasty (1290), taking a total of fourteen years. The Yunnan Provincial Library announced that it has two units of the Puning Canon in its collection. In 2009, it was announced that these two units contain 808 volumes and 404 volumes, respectively. There are two incomplete units in the private collection.

The exact time of the publication and completion of the

Yuan Official Canon 元官藏 remains uncertain. The publication process might have begun in the second year of the Zhishun 至順二年 reign of the Yuan dynasty (1332) to the second year of the Zhiyuan reign 至元二年 (1336). Two works are held by the Yunnan Provincial Library, one with 12 volumes and the other with 20 volumes. There is no private collection of this CBC in Yunnan.

4Now, we discuss the Hongfa Canon. The name Hongfa Canon is only temporarily used, and has not yet been accepted by the academic community. This edition of the Buddhist Canon is catalogued according to Qianziwen 千字文 (one-thousand-character primer) in Zhiyuan fabao kantong zonglu 至元法寶勘同總錄. Any printed editions of the Buddhist Canon engraved during the Yuan dynasty that use this catalogue are possibly the Hongfa Canon. There is no private collection of this Buddhist Canon in Yunnan.

The Yongle Southern Canon was engraved in the 10th year of the Yongle 永樂 reign of the Ming dynasty (1412) and completed in the 15th year of Yongle (1417). This collection might have already begun to be printed and circulated before it was fully completed. The unit kept in the Yunnan Provincial Library is a printed version from the 8th and 9th years of Yongle. There is no private collection of this Buddhist Canon in Yunnan.

The Yongle Northern Canon was ordered to be engraved, and printing began in the eighth year of the Yongle reign (1410). It was first engraved in the 17th year of this reign (1419) and completed in the 5th year of the Zhengtong reign of Emperor Yingzong (1440). Two works of this Canon are kept in the Yunnan Provincial Library. One text is from Taihua Mountain 太華山 in Kunming and the other from Jizu Mountain 雞足山 in Dali. The details of the private collection of this CBC are currently unclear.

The

Jiaxing Canon 嘉興藏, also known as the

Wanli Canon 萬曆藏 or the

Jingshan Canon 徑山藏, was compiled over a 120-year period from 1589 in the late Ming period to 1712 during the reign of the Kangxi 康熙 Emperor of the Qing dynasty. The Jiaxing Canon may be divided into editions such as the Lengyansi edition 楞嚴寺版, Wanli Canon 萬曆藏, Mizang edition 密藏本, and Jingshan edition 徑山版. The Ming dynasty monk Mizang Daokai 密藏道開 (fl. 1560–1595) promoted its publication by means of a vow; Daokai, along with the monk Huanyu 幻豫 (fl. late-sixteenth century), initially had woodblocks engraved at Miaode Hermitage 妙德庵 on Mt. Wutai in 1589. Work on this Canon progressed in several places over many years, but, eventually, all the woodblocks were gathered together at Lengyansi in Jiaxing in Zhejiang Province. In 1620, the “main Canon” (zhengjing 正經) was published comprising 1192 titles 部 in 210 cases 函. In 1666, the “supplementary Canon” (xuzangjing 續藏經) was printed as an addendum with 237 titles in 90 cases; and in 1677, it was supplemented again with a further supplementary Canon (yuxuzang 又續藏) of 189 titles in 43 cases. This is the core of the

Jiaxing Canon. In total, there are 2195 titles in 10,332 volumes. The

Jiaxing Canon is the largest and most voluminous of the Chinese Buddhist Canons (see

Nakajima 2005).

3. A Detailed Investigation of Fragmentary Fascicles of the Song, Yuan, and Ming CBC in Private Collections in Yunnan

As scanned copies of the CBCs in the Yunnan public collections have not been made available to the public, it is common for these collections to be arranged in a disorganized manner. Hou Chon 侯衝 believes that this is “a muddled account” (

Hou and Qian 2024, pp. 3–31). Therefore, further public release of the scanned copies of the CBC collections held by the Yunnan Provincial Library is necessary before conducting in-depth research. Although the number of Song, Yuan, and Ming dynasty CBCs privately collected in Yunnan is not large, the collectors are willing to share information. Therefore, some introductions can be made to these privately collected CBC sets.

As far as we know, the private collections in Yunnan mainly consist of three types of fragmentary fascicles of the CBC; namely, the Qisha Canon, Puning Canon, and Jiaxing Canon. This article discusses these three types in detail.

3.1. Qisha Canon

In the twenty-second year of Hongwu 洪武二十二年 (1389) in the Ming dynasty, the Xinshan 信善 made a request for a set of the Qisha Canon in East China. Due to constant transfers, many volumes of this set of the Buddhist Canon were lost, and later generations became unaware of it. It was not until 2008 that some volumes were found in Tonghai County 通海縣, Yunnan Province. This discovery sparked the attention of some local people who began to collect these scriptures, thus attracting more attention.

At present, the exact number of books and the overall situation of these volumes of the Qisha Canon remain unknown. We tried to gather information on these volumes and outline their status. Hopefully, this information may provide some sources showing how the literati in Yunnan requested this set of the Qisha Canon, how it came to Yunnan, and how it was worshipped in the temple.

3.1.1. The Date

At present, the colophons in four volumes in this set of the Buddhist Canon are known: Volume 5 of Da Yuan Zhiyuan fabao kantong zonglu 大元至元法寶勘同總録, Volumes 15 and 16 of Sāgaramati-paṛipricchā-sūtra (Haiyipusa uowen jingyinfamenjing 海意菩薩所問淨印法門經), Volume 4 of Jātakamālā (Pusabenshengmanlun 菩薩本生鬘論), and Volume 493 of Mahāprajñā-pāramitā-Sūtra (Danbanruoboluomijing 大般若波羅蜜多經). The colophons of the first three kinds of Volume 5 of Da Yuan Zhiyuan fabao kantong zonglu, Volumes 5 and 6 of sāgaramati-paṛipricchā-sūtra, and Volume 4 of Jātakamālān are identical. The date recorded in these four Volumes indicates the local literati made a request for the Qisha Canon in the twenty-second year of Hongwu (1389).

Who made these requests? According to Volume 5 of Da Yuan Zhiyuan fabao kantong zonglu, Volumes 15 and 16 of sāgaramati-paṛipricchā-sūtra, and Volume 4 of Jātakamālā, we can ascertain from the names of the places where the collectors lived and the names of the monks who obtained the frontispieces that most of these collectors were inhabitants of Kunming. The colophon of Volume 493 of Mahāprajñāpāramitā Sūtra details that the requester Lady Liu and her family members were from the capital. She was probably a native of Yunnan Province based on the context of the colophon. Her husband Li Bao was an official of a minority nationality residing in Nanjing. Members of the Liu family were immigrants from Yunnan. When they surrendered to the Ming, they were taken to the capital, probably as residents under the custody of the government, but were well treated. This explains why they claimed that they lived in the capital. Therefore, it can be said that the people who requested the Buddhist Canon were devotees in Kunming.

3.1.2. The Requesters

Most of the people who joined in requesting the Buddhist Canon were devotees of Buddhism. However, the colophon of Volume 493 of Mahāprajñā-pāramitā-Sūtra indicates that the 600 Volumes of Mahāprajñā-pāramitā-Sūtra were printed with the money that Ms. Liu donated. She did this in order to give her deceased husband Li Bao 李保 relief and prayed for both her family and her husband’s family members’ safety from purgatory. Li Bao was an Assistant Director in the Yunnan Provincial Administration. Considering that Mahāprajñā-pāramitā-Sūtra is the first text in the CBC, it can be inferred that Ms. Liu and her family members were sponsors of the request for the Buddhist Canon.

Who was Li Bao? The name of Li Guanyin Bao 李觀音保 was mentioned in the colophon. It was customary for lay Buddhists in the Dali area to include a Bodhisattva’s name in their names. It is certain that Li Guanyin Bao was a disciple of Esoteric Buddhism in Dali. His life and work were recorded in

The Annals of Yunnan during the Jingtai Period 1450–1457 (Jingtai Yunnan tujing zhishu 景泰雲南圖經志書) (

Li and Liu 2002, p. 34). These records reported that Li Bao was escorted to Nanjing by Fu Youde 傅有德 (1327–1394). Li was appointed local military commander and an officer of Yongchang 永昌府 Prefecture Administration. He was given the name of Li Guan 李觀. Li, a native of Shouzhou in Hexi Corridor 河西壽州, Gansu Province, was likely to be a descendent of XiXia 西夏 (1038–1227). However, it is not known where Shouzhou was located in Xixia. Li Bao was rewarded by Zhu Yuanzhang 朱元璋 (1328–1398) for providing military support to the Ming government in the campaign to stabilize the western Yunnan area. Because of the heavy military presence in western Yunnan, it made sense for his family to stay in Yingtianfu 應天府, the capital of the Ming. The family members were held under the custody of the Ming in the capital against their will to ensure the loyalty of the generals. This ensured that the emperor felt at ease.

3.1.3. Frontispieces

The frontispieces of the Qisha Canon were re-carved following the frontispieces of the Qisha Canon constructed during the Yuan dynasty (1205–1368), with three folds plus a fold with dragon images. An inscription with a vow that the emperor would live thousands of years was printed in a frame with three sides showing dragons in one fold. In the lower right-hand part of the frontispiece, there is a line of colophon which records that the monk Fobian 釋佛辨 donated money to print the frontispiece of the woodcut illustration. Moreover, each volume was pasted with a frontispiece. Fobian was a monk in the Western Hill 西山 of Kunming (also called Taihua mountain 太華山). However, no record of his life or work has been found.

3.1.4. The Temples in Which the Qisha Canon Was Kept

At the end of Volume 493 of

Mahāprajñāpāramitā-Sūtra, there is an ink-printed, rectangular, one-sided stamp with text entitled “Buddhist Canon kept in Juezhao Temple” (Jue zhao si zangjing 覺照寺藏經). Thus, it can be inferred from this stamp that, after the Canon was printed, it was shipped to Juezhao Temple in Kunming—the oldest temple in the province. The temple was also called Eastern Temple (Dongsi 東寺) as it is located in southern Kunming. Both the

Comprehensive gazetteer of the realm (

Huanyu tongzhi 寰宇通志) and

Comprehensive Gazetteer of the Ming Dynasty (Da Ming yi tongzhi 大明一統志) mention this temple, which was built during the period of the Nanzhao State 南詔 (738–902) by chieftain Wang Cuodian 王嵯巓 (?–859). The temple remained there during the Ming dynasty. There is a pagoda of thirteen stories. Thus, when this set of the

Qisha Canon was shipped to Kunming, it was housed in this temple, known as the Buddhist Canon in Juezhao Temple. Zhou Yongxian 周泳先 thought that the Yunnan Provincial Library holds a collection of volumes of this CBC originally kept in Fazang Temple 法藏寺 in Dali (

Zhou 2022, pp. 422–32). These volumes were stamped with the seal to the effect that “Jue zhao Temple wishes the emperor a long life” (Juezhaosi zhuyanshengshou dazangjing 覺照寺祝延聖壽大藏經). It is likely that these volumes of the

Qisha Canon kept in the Yunnan Provincial Library belong to the same set of the

Qisha Canon kept in Juezhao Temple.

3.1.5. The Status of the Extant Volumes of the Qisha Canon

Volumes of the Qisha Canon are scattered in the collections of private individuals. Except for the Yunnan Provincial Library, no public institutions have any records of it. The total number of extant volumes may not exceed two or three hundred volumes.

3.1.6. Colophons

Now, we cite the colophons of four volumes. Volume 5 of Da Yuan Zhiyuan fabao kantong zonglu, Volumes 15 and 16 of sāgaramati-paṛipricchā-sūtra, and Volume 4 of Pusa Jātakamālā have shared colophons:

Buddhist devotees who lived in Kunming County, Yunnan Prefecture in the Great Ming [dynasty] donated money to request this set of the Buddhist Canon. Their names are listed as follows: Zhao Yunzhong 趙允中, Kang Fu 康福, Su Anza 蘇安札, Gao Hu 高護, Yang Zhongjie 楊仲節, Li Jingheng 李景亨, Wang Sijing 王思敬, Su Youwen 蘇友文, Yang Tianxi 楊天錫, Li Zhongyi 李仲義, Zhang Caifu 張才輔, Lü Taiheng 呂泰亨, Liu Jinde 劉進德, Li Guicai 李貴才, Yan Sicheng 閆思誠, Li Shan 李善, Zhang Yi 張益, Li Shou 李受, Su Youzhi 蘇友直, Li Zhongyuan 李仲原, Guanyin Nu 觀音奴, etc. With compassion, they donated money to request a set of the Buddhist Canon. The merits they collected will protect members of their families. “It is our wish that all obstacles for liberation will be eliminated. All souls would not be deceived. All people enjoy happiness and obtain full wisdom. The happiness and wisdom will go down from generation to generation. As parents have made perfect merits, all descendants will worship the Three Treasures: the Buddha, the Dharma and Sangha. All people will repay the fourfold of grace: the grace of the Buddha; the grace of parents; the grace of the state; and the grace of fellow beings. All people will share the merits and grace. People in the world will share the sympathy, perfection and wisdom. Twenty-second year of Hongwu (1389)”

“大明國雲南府昆明縣居住、奉佛造經信士趙允中、康福、蘇安劄、高護、楊仲節、李景亨、王思敬、蘇友文、楊天錫、李仲義、張才輔、呂泰亨、劉進德、 李貴才、閆思誠、李善、張益、李受、蘇友直、李仲原、觀音奴同發善心人等,各捨淨資,敬贖大藏尊經。所集功勳,專伸保護各人闔家眷屬等。伏願:夙障頓消,靈心不昧,福足慧聚,生生恒備。二嚴願滿功圓,世世常親三寶。更將餘利資薦各家兩門先祖內外宗親等眾,乘此良因,超升淨域。普冀上報四恩,下資三有,法界含情,同圓種智者。歲洪武二十二年 月 日謹記。”

The colophon in Volume 493 of Mahāprajñāpāramitā-Sūtra says the following:

“Buddhist devotees Mrs. Liu 劉氏, Zushibi 祖師婢, her sons (Wentong 文童, Shutong 書童), daughters (Guixiangnu 桂香奴, Tianxiangnu 天香奴, Huixiangnu 回鄉奴), and all her family members, donated money and property to request a set of Mahāprajñāpāramitā Sūtra, totaling 600 volumes. The merits she gathered would assist the soul of Li Guanyin Bao 李觀音保, her deceased husband, who was a general and a commander. The merits would assist the grand-father, father, mother, and also Mrs. Liu’s parents, and their relatives. They may ride the boat of compassion of Prajñā to the other shore of Bodhi. I wish that my family will be blessed with good fortune and that my life will be prolonged. I wish that all obstacles for liberation would be eliminated. All souls would not be deceived. All people enjoy happiness and obtain full wisdom. The happiness and wisdom will go down from generation to generation. As parents have made perfect merits, all descendants will worship the Three Treasures: the Buddha, the Dharma and Sangha. The fourfold of graces, the grace of the Buddha; the grace of parents; the grace of the state; and the grace of fellow beings the grace of parents, will be repaid. The merits I have made will be share by all people. People in the world will share sympathy, and perfection and wisdom. Twenty-second year in the reign of Emperor Hongwu (1389).”

“大明國京都應天府在城居住奉佛造經信女劉氏、祖師婢、男文童、書童、女桂香奴、天香奴、回鄉奴,洎一家善眷人等,喜捨淨財,敬贖《大般若波羅蜜多經》一大部,計六百卷。所集功德,特伸資薦故夫主明威將軍、金齒衛指揮李觀音保之靈。該薦李宅門中祖父右承昂吉、父親思蘭、母親仙氏;劉宅門中父親劉公、母親彭氏,並及內外宗親等眾,乘般若之慈舟,到菩提之彼岸。餘利家門清吉,壽算增延。伏願:夙障頓消,靈心不昧。福足慧聚,生生恒備。二嚴願滿功圓,世世常親三寶。四恩普報,三有均霑。法界含情,同圓種智。歲洪武二十二年月日謹記。”

The above two colophons often appeared at the end of the CBC. But these two colophons were unique. Among them were not only the names of indigenous officials in Yunnan, but also there were four patrons with the Chinese character “slave 奴”, and it is very likely that these people were related to the Liao 遼 (916–1125), Jin金 (1115–1234) and XiXia, which was very rare in many CBC colophons. According to the currently published literature, only Li HuiyueL 李惠月, a remnant of the Xia Xia Dynasty, was found in the

Puning Canon (

Sun and Zheng 2022).

In short, the frontispieces of these volumes of the Qisha Canon were engraved and printed with the donation from monk Fobian at Western Hills in Kunming in the twenty-second year of Emperor Hongwu (1389). Buddhist monk Xinshan made a request to print it and shipped it to Juezhao Temple in Kunming. As the years passed, part of the volumes were lost; some volumes were brought to Fazang Temple in the Dali area by a tantric monk, Dong Xian 董賢, at the beginning of the Ming dynasty, and later these volumes were brought to the Yunnan Provincial Library.

Monks in Yongjin Temple 涌金寺 in Tonghai County had obtained some volumes. Later, these volumes were scattered around and held by private individuals. Ten volumes of the Qisha Canon from Juezhao Temple recently appeared in an antique book auction in China. However, this small number of volumes does not offer a comprehensive view of the entire Canon. In other words, it was only a glimpse.

3.2. Puning Canon

The private collection of the

Puning Canon in Yunnan consists of two volumes; namely, Volume 53 of the

Abhidharma Vibasha (

Apitanpiposhalun 阿毗曇毗婆沙論) and the first volume of the

Dhammapada (

Fajujing 法句經). Neither of these two volumes is complete and they are kept in the private Yuanning Zhai 元寧齋

5 in Yunnan. Both volumes are stamped with the ink seal of “Imperial Bestowed Yuanzhao Xingzu Chan Temple” (Yuci Yuanzhaoxingzuchansi 御賜圓照興祖禪寺) (

Figure 3). This ink stamp also appears in the

Puning Canon held by the Yunnan Provincial Library (

Zhou 2022, pp. 422–32).

Yuan Ding 圓鼎 (?–?), a monk of the Qing dynasty, authored the book

Biographical Records of Yunnan Monks (

Dianshi Ji 滇釋記); it is mentioned that in the 15th year of Zhiyuan (1278), when the Chan master Daxiu 大休禪師 (1240?–1320?) came to Xingzu Temple 興祖寺 on Yuanzhao Mountain 圓照山 in Kunming to preach, he received a CBC bestowed by the imperial court. There is no record of “Xingzu Temple on Yuanzhao Mountain” in the existing literature. However, Xu Xiake 徐霞客 (1587–1641) once mentioned that he wanted to go to Qiongzhu Temple 筇竹寺 on Yuan Mountain, but ended up taking a fork in the road to the nearby Yuanzhao Temple (

Zhu 1985, p. 844). Therefore, it is possible that Xingzu Temple on Yuanzhao Mountain is located to the west of Kunming, right next to Yuan Mountain. This

Puning Canon with the ink seal “Bestowed by the Emperor to Xingzu Temple on Yuanzhao Mountain” might have been a large CBC bestowed by Kublai Khan 忽必烈 (reigned 1260–1294), the founder of the Yuan dynasty, to Xingzu Temple on Yuanzhao Mountain in Kunming, Yunnan Province, in the 15th year of the Zhiyuan era 至元十五年 (1278). At this time, the

Puning Canon was not yet fully completed when it was bestowed. This shows that bestowing the CBC does not necessarily mean bestowing the entire CBC.

The 53rd volume of the Abhidharma Vibasha has the thousand-character text number Ren three 仁三. This work has no frontispiece illustrations. The beginning is intact, but the end is incomplete. There are a total of three seals inscribed with the words “Imperial Bestow upon Xingzu Chan Temple.” This volume is currently known to be kept in the Cultural Center of Tonghai County 通海縣文化館, Yuxi City 玉溪市, Yunnan Province, along with the Qisha Canon, which was requested to be printed in the 22nd year of the Hongwu reign of the Ming dynasty. Later, it was passed down to the private Yuanning Zhai 元寧齋 in Kunming.

In the first volume of the

Dhammapada, the beginning is complete, but the end is incomplete. The former features a woodblock print of “The Buddha Preaching” 如來說法圖, and this unit is marked with three ink stamps inscribed with “Imperial bestow upon Xingzu Chan Temple.” The most valuable part of this book, apart from the stamps, lies in the print at the very beginning of the scripture. The woodcut illustration of Yuan Ning Zhai consists of two parts: on the right is a picture of Sakyamuni Buddha 釋迦牟尼佛 preaching on a high platform, and on the left is a picture of the Wanshou Hall 萬壽殿 translating scriptures. The theme of this frontispiece can be called “Translation and Preaching in Wanshou Hall 萬壽殿譯經圖” (

Figure 4). Such prints have appeared in three volumes of the Chinese CBC that have been published.

There is one volume of the Avatamsaka Sūtra (Dafangguang Fo Huayanjing 大方廣佛華嚴經) in the Qisha Canon kept in the National Library of China. The colophon in Volume 73 shows these words, “Sponsored by great Master Yongfudashi Yang Lian Zhenjia, President of Jianghuai Zhulu Buddhism” (Du Gongde zhu Jianghuaizhulu Shijiaoduzongtong Yongfudashi Yanglianzhenjia 都功德主江淮諸路釋教都總統永福大師楊璉真佳), on the far left. From this colophon, we know that Master Yangliang zhenjia, director of the Buddhist registry office in the Jianghuai area, was a donor.

One text entitled

Vimuttimagga (

Jiet uo dao lun 解脫道論, or

Treatise on the Path of Liberation) in the

Puning Canon kept in Shaanxi Provincial Library 山西省圖書館 shows a colophon: “Great Master Huizhao 慧照 (1289–1373), who was responsible for the project and engraved the woodblocks of the

Puning Canon, alongside Monk Dao’an 道安 (?–?), the abbot of Great Puning Temple in Nanshan, and Great Diamond Master Yanba 簷巴

6 (1229–1303), made a compassionate vow to make this Canon popular among people” (Ganyuan diao dazangjingban Baiyunzongzhu Huizhaodashi Nanshan da Puningsi zhuchi shamen Dao-an gongde zhu Yanba shifu jingang shangshi ciyuanhongshen puguishehua 幹緣雕大藏經板白雲宗主慧照大師南山大普寧寺主持沙門道安功德主簷巴師父金剛上師慈願弘深普歸攝化).

After comparison, it was found that the title woodcut prints of Avatamsaka Sūtra Volume 73 and Vimuttimagga Volume 1 were printed using the same woodcut board. The difference between the two woodcut prints is that the Chinese inscription on the far right is different.

Mr. Lai Tianbing 賴天兵 believes that Dao’an, Yanba, and others carved a woodblock illustration of “Translation and Preaching in Wanshou Hall 萬壽殿譯經圖.” Later, Yang Lian Zhenjia 楊璉真佳 (?–?) transferred this print to the printing house of the

Qisha Canon. On the far right of the print, he replaced the names of Dao’an and Yanba with his own name (

Lai 2013, pp. 234–42). Although the woodcut illustrations of the three volumes all belong to the same theme of “Translating Scriptures in the Wanshou Hall” 萬壽殿譯經圖, successive printed materials appear on the same woodblock, with adjustments only to the text at the beginning and end. The Yuanning Zhai edition is nearly identical to the previous two volumes, but careful comparison reveals some subtle differences. Therefore, it can be determined that it is not printed on the same engraving plate, as the previous two volumes. However, the prints in this album have become blurred. It can be seen that the woodblock is severely worn. It can be speculated that Dao’an, Danba, and others might have recreated an identical frontispiece of “Translating Scriptures in the Wanshou Hall” based on the woodblock prints of the “Yuanning zhai” edition. Since the “Yuanning zhai” version of the

Punning Canon was bestowed to Yunnan by Emperor Kublai Khan (1215–1294) in the 15th year of the Zhiyuan 至元 era (1278), this indicates that the frontispiece of the Wanshou Hall, in which monks performed the translation already appeared in the

Punning Canon at least before the 15th year of the Zhiyuan era (1278). It is possible that later on people found that the woodblock plates were severely worn. Therefore, Yanba donated funds to re-carve these woodblocks. We believe that the woodblock plates of the

Puning Canon were stored in the printing houses where the scriptures were printed and bound; there was an interactive relationship between the printing houses and the Puning Temple, which owned the wooden plates. The printing houses could randomly arrange the frontispieces at the very beginning of the scriptures. However, they must have sought approval from the monks of Puning Temple 普寧寺.

3.3. Jiaxing Canon

A private collector has kept two copies of the

Jiaxing Canon. The first one is

Mūla-sarvāstivāda-vinaya-kṣudraka-vastu (

Genben shuo yiqie youbu pinaiye zashi 根本說一切有部毗奈耶雜事), of which Volumes 1–4 are extant. A frontispiece is found at the beginning. A colophon of seven Chinese characters reads “Jingshan Huacheng Heng rui Zi” 徑山化城恒瑞梓 (

Figure 5). It is found on the lower left side of the page. These words indicate that this volume was printed by the monk Hengrui 恒瑞 in Huacheng Temple, Jingshan Mountain. Three large red stamp imprints are also found on this page. Two of them have the inscription “Canon of Baohua Chan Monastery on Shuimu Mountain” (Shuimushan baohuachanlinzangjing 水目山寶華禪林藏經), and the other one has the inscription “Transmission of the Buddha’s Heart” (Chuanyinfoxin 传印佛心) (

Figure 6). According to the seal, this collection of scriptures originated from the Baohua Nunnery on Shuimu Mountain 水目山寶華寺 in Xiangyun County 祥雲縣, Dali 大理, Yunnan Province 雲南省. Each volume of this Canon is inscribed with a mark at the end, which is consistent with the format of the

Jiaxing Canon. The following transcript marks the end of Volume 1:

“The disciple of Jintan Jingxin, Shen Ji, who donated funds to engrave the first volume, says, Mūla-sarvāstivāda-vinaya-kṣudraka-vastu, totaling 5410 characters. The amount of silver in two taels, four qian, and three fen and five fen were paid for carving. I pray for my deceased wife Wang Yanzhen and my deceased son Wang Yuankai. I hope to rely on this minor merit I have made as a cause, with the help of the divine power of the Buddha, and for all eternity, that all of us would be free from worldly ties. As a friend of the Dharma, we will ascend to enlightenment together and quickly attain enlightenment. In the early summer of the year of Guiyou (1633) of Emperor Chongzhen 崇禎 (r. 1628–1644) Mt. Gulong in Jinsha.”

“金壇淨信弟子深吉敬施資奉刻《根本說一切有部毘奈耶雜事》卷第一,計字五千四百十個,該銀二兩四錢三分五厘。超薦亡侶王彥湞、亡男王元楷。伏願仗此微因,乘佛神力,生生世世,永離塵緣。遞為法友,同登正覺,速證菩提。崇禎癸酉歲孟夏月金沙顧龍山識。”

Mt. Gulong in Jinsha 金沙顧龍山 participated in the engraving of the

Jiaxing Canon (

Li and He 2003, p. 493). It can be confirmed that this volume is one of the

Jiaxing Canon sets.

The exact time when this collection of scriptures was introduced to Baohua Chan Monastery on Shuimu Mountain is uncertain. Baohua Chan Monastery was built by Chan Master Wuzhu Hongru 無住洪如 (1589–1664) in the 11th year of the Chongzhen 崇禎 reign of the Ming dynasty (1638) (

Qiu 2003, p. 154). In the early extant literature related to Baohua Chan Monastery, there was a stone inscription on how Baohua Monastery was repaired. The inscription, however, did not provide a record of when they requested the printing of this set of the

Jiaxing Canon. As this stone has been damaged, we need to explore more materials to verify this information.

During the Chongzhen period (1628–1644), Wuzhu accompanied his teacher Cheyong Zhouli 徹庸周理 (1591–1647) to the south to request the

Jiaxing Canon, which was later placed in Deyun Temple 德雲寺 on Miaofeng Mountain 妙峰山 in Dayao County 大姚縣, Chuxiong 楚雄 (

Guo 2015, p. 103). During the 1940s, a review of this collection of scriptures revealed that 492 volumes still exist, but it did not include the scripture

Mūla-sarvāstivāda-vinaya-kṣudraka-vastu (

You 1988, pp. 846–52). It is possible that, after this

Jiaxing Canon set was transported back to Yunnan, it was not all placed in Deyun Temple; some of it was taken to Baohua Monastery on Shuimu Mountain, which had just been revived by Master Wuzhu, and became the triad of Baohua Monastery.

7 This volume of the

Jiaxing Canon, which is stamped with the red seal of “Shuimushan Baohua Chanlin Zangjing” (seal stamp of Shuimushan Baohua Chan Monastery), may belong to the same

Jiaxing Canon as the one from Deyun Temple.

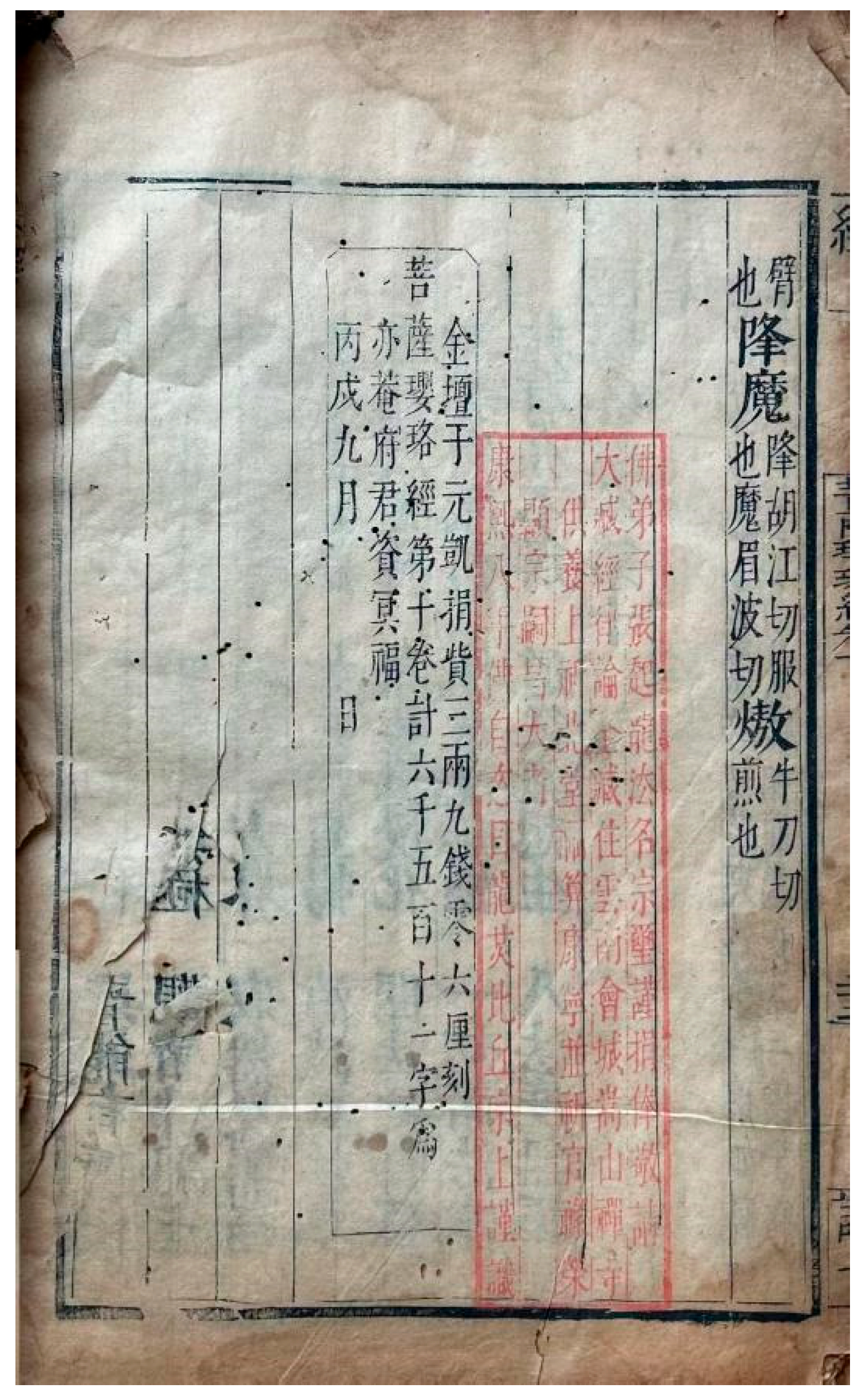

The second type is the Pusa yingluo jing 菩薩瓔珞經, which consists of Volumes 6 to 10, totaling five volumes. The title page of this scripture features a red seal inscribed with the words “Stored forever in Songshan Chan Monastery, Yunnan Province” 雲南省嵩山禪院常住. At the end there is a rectangular red seal, which reads as follows:

“The Buddhist disciple Zhang Qilong, whose Dharma name is Zongxi, sincerely offers his salary to keep the Sutras, Vinaya, and Abhidharma of the Buddhist Canon in the Songshan Chan Temple in Huicheng, Yunnan. Pray for Longevity and health for mother, as well as for official honor, prosperity and the continuation of the family. 15 July of Kangxi Eighth year, Longyan Bhikkhu zongshang record.”

“佛弟子張起龍,法名宗璽,謹捐俸敬請大藏經、律、論全藏住雲南會城嵩山禪寺供養。上祈北堂福算康寧,並祈官祿榮顯,宗嗣昌大者。康熙八年佛自恣日龍炗比丘宗上謹識。”

This

Jiaxing Canon was first briefly mentioned by Chen Zidan 陳子丹 in 1988. Later, Wang Haitao adopted it and included it in his book (

Wang 2001, p. 322). The city of Huicheng in the vermilion seal at the end of the scripture refers to Kunming. Songshan Chan Monastery, also known as Songshan Temple, is located near the Huguo Bridge 護國橋 by the Panlong River 盤龍江 in the south of Kunming City 昆明 (

Long 1949, p. 25, chapter 114).

This temple was established during the reign of Emperor Kangxi by a Chan monk named Yezhu Fuhui 野竹福慧 (1623–?) from Sichuan. He came to spread the Dharma, and thus the school’s ethos was greatly invigorated (

Yuan 2001, p. 110).

Mr. Zhang Qilong 張起龍 was responsible for the request of the Buddhist Canon. He prayed for his official rank and honor. Apparently, Zhang came from an official family in Yunnan at that time. Although there are no specific records of Zhang Qilong’s life, his general life could be roughly explored based on numerous scattered documents. He was originally from Jining Prefecture 濟寧州, and was born in the 33rd year of the Wanli reign of the Ming dynasty 萬曆三十三年 (1605). In the eighth month of the twelfth year of the Chongzhen reign 崇禎十二年 (1639), Zhang was granted the position of “Yunnan zuowei qiansuoshu shishoubaihu 雲南左衛前所署實授百戶, Actual Appointment as Hundred-Household Commander in Yunnan Left Guard Office.” The reason for his promotion was the fact that one of his ancestors named Zhang Yu 张玉 died in battle against Wusa 烏撒 in the sixteenth year of the Hongwu 洪武 reign (1383) and was highly regarded as heroic. Zhang Yu’s son, Zhang Ming 張銘, was promoted to deputy Fu qianhu 副千戶 (a thousand households) because of his father’s military achievements. This set of “Fu qianhu” was passed down all the way to Zhang Ren 張仁, the sixth descendant of Zhang Yu. After Zhang Ren passed away due to illness in the 27th year of the Wanli reign (1599), he did not continue the succession. By the time Zhang Qilong, the nephew of Zhang Ren, succeeded to his uncle’s position, the period had exceeded 42 years, and, thus, he was demoted by a half rank and could only receive the position of Baihu 百戶 (a hundred households) (

Meng 2020, p. 107). Zhang Qilong should have remained in Yunnan as an official after the fall of the Ming dynasty and under the jurisdiction of Wu Sangui 吳三桂 (1612–1678). Later, Wu Sangui rebelled against the Qing dynasty, and Zhang Qilong also became a general of Wu Sangui’s regime 吳三桂政權 (1673–1681), opposing the Qing army. On the 13th day of the 1st lunar month of the 19th year of the reign of Emperor Kangxi 康熙十九年 (1680), he fought against the Qing army and was defeated and captured alive (

Yang 1683). In the 3rd month of the 19th year of the reign of Emperor Kangxi (1680), Emperor Kangxi (1654–1722) issued an edict to the King of State Affairs requesting that Zhang Qilong be dispatched to pacify the anti-Qing personnel of Wu Sangui’s regime in Yunnan and Guizhou 貴州 regions. This would grant Zhang Qilong a capital pardon (

Qing court 1662–1722). In the

Draft History of Qing (Qingshigao 清史稿), completed during the Republic of China period, it is recorded that in the 19th year of the Kangxi reign (1680), Zhang Qilong and 17 other generals of the Wu Sangui regime who were captured were killed together. Based on this, it can be inferred that Zhang Qilong might not have accepted the demands of Emperor Kangxi. From the above, it can roughly be inferred that Zhang Qilong was born in 1605 and died in 1680. The time when he requested the printing of the “

Jiaxing Canon” at Songshan Temple in Kunming was 1669, when Zhang Qilong was 64 years old.

In addition, in the sixth year of the Kangxi reign (1667), monks in Songshan Temple also engraved and printed Vajracchedikā-prajñāpāramitā (Jingang bore boluomi jing) 金剛般若波羅蜜經. A colophon at the end of the text mentions “the devout believers under the Prince of Pingxi” 平西親王下善信. Yezhu Fuhui also prayed for Wu Sangui’s blessings four times at Songshan Temple (Jiaxing Canon Vol. 245). Therefore, there is a certain potential connection between this Jiaxing Canon and the Wu Sangui regime.

The final seal also recorded the Bhikṣu (monk) Zongshang of Longguang Monastery 龍炗比丘宗上 (?–?). He was involved in the compilation of

The Sayings of Master Yezhu of Songshan Mountain (

Songshanyezhu chanshi yulu 嵩山野竹禪師語錄), but his reputation was not prominent. Therefore, it is likely that the activity of requesting the printing of this

Jiaxing Canon was initiated by Yezhu Fuhui, with the participation of Zhang Qilong and the monk Zongshang.

8The two incomplete volumes of the Jiaxing Canon mentioned above bear collection stamps related to local Chan monasteries, monks and local officials in Yunnan. Based on the content of these stamps, it can be inferred that during the late Ming and early Qing dynasties, Chan monks and officials in Yunnan highly esteemed and revered the Jiaxing Canon. In the late Ming Dynasty, the Yaoan Tusi Gao Tiao 姚安土司高糶, the Yaoan official Tao Gong 陶珙, and monks from Jizu Mountain all went to Jiangnan to obtain the Jiaxing Canon. Most of these Jiaxing Canon are still preserved in the Yunnan Provincial Library and are very important documents that deserve further research.

It is worth noting that these two fragmentary fascicles of the Jiaxing Canon are not only closely related to Chan monks in Yunnan, but also maintain internal relations with Chan in Zhejiang 浙江. Master Wuzhu Hongru is a disciple of Cheyong Zhouli, and Cheyong Zhouli is also a disciple of Chan Buddhism monks Mizang Daokai 密藏道開 (1543–1604) and Miyun Yuanwu 密雲圓悟 (1566–1642). Moreover, Mizang Daokai is the real orchestrator of the

Jiaxing Canon engraving in the early stage. Chan Master Yezhu Fuhui is a disciple of Sichuan Chan monk Shanhui Xinghuan 山暉行浣 (1621–1687) and Poshan Haiming 破山海明 (1597–1666), and Po Shan Haiming is also a disciple of Zhejiang Chan monk Miyun Yuanwu. Therefore, we can see the potential relationship between these two

Jiaxing Canon sets in Yunnan and Zhejiang Chan Buddhism.

9 4. Conclusions

The situation of collecting CBC in Yunnan region has been mentioned by some scholars, and preliminary research has been conducted (

Table A1 and

Table A2). However, unfortunately, these studies only focused on the CBC collected by the Yunnan Provincial Library, and there were very few studies that delved into the private collections of CBC in Yunnan. During the initial investigation of the private collections of CBC in Yunnan, it was discovered that there were imperial bestowed CBC from the Yuan Dynasty and also those obtained by local officials and Buddhist believers. These were all absent from the CBC collected by the Yunnan Provincial Library that has been made public. Based on the private collections of the fragmentary fasciclen of CBC in Yunnan, it can be found that political forces had an influence on the acquisition of CBC in Yunnan. Or, the popularity of Chinese Buddhist scriptures in Yunnan might be closely related to the infiltration of national political forces into the local areas of Yunnan.

In conclusion, these fragmentary fascicles of three examples of CBCs from the Song, Yuan, and Ming dynasties, which are privately collected in Yunnan, provide valuable documentary materials for the study of the history of Buddhism in Yunnan Province, as there are no similar versions in the Buddhist literature collection of the Yunnan Provincial Library and Yunnan Academy of Social Sciences. Based on these three privately collected CBCs, we can draw the following conclusions:

Emperor Kublai Khan of the Yuan dynasty attached great importance to the Buddhist community and monks in Yunnan, and specially bestowed the Yunnan CBC upon them by imperial decree.

In the 22nd year of the Hongwu reign of the Ming dynasty (1389), Buddhists in Yunnan (including the families of officials stranded in Nanjing as residents who were well treated, but under government surveillance) initiated the printing of a set of the Qisha Canon and sent it to Kunming for worshipping. The purpose was not only to spread the Dharma and benefit sentient beings, but also to liberate the deceased and ancestors. This reveals that, in the hearts of Buddhists, the merit of printing the CBC is intrinsically linked to the liberation of deceased souls and filial piety toward ancestors.

From the fragmentary fascicles of two editions of the Jiaxing Canon requested for printing in Dali and Kunming in the early 17th century, it can be known that at that time, the Chan School in Yunnan became a supporting force of Buddhism in Yunnan. Both in the central and western parts of Yunnan, there had already been Chan school leaders initiating requests for printing the CBC.

The common feature of these fragmentary fascicles of three CBC sets is that the Chan master Daxiu of the Yuan dynasty, the Liu family who lived in Yingtianfu (Nanjing) in the early Ming dynasty, the Chan Master Wuzhu Hongru of the late Ming and early Qing dynasties, and the Chan Master Yezhu Fuhui all might have had close ties with the Buddhist communities outside Yunnan but, at the same time, promoted the rise in the CBC cause in Yunnan. From this it can be determined that, from the 13th century to the mid-17th century, there was a deep connection and frequent interactions between Buddhism in Yunnan and Buddhism in other places.

Of course, the institution in Yunnan that has the richest collection of CBC sets is the Yunnan Provincial Library. Therefore, it is necessary for the Yunnan Provincial Library to release more information about its CBC collection.