Abstract

Philistia during the Iron Age reflects a distinct material culture, as well as a special historical background related to biblical and other texts. The Philistines occupying this region may have been immigrants from the west (Cyprus and the Aegean), bringing elements of their motherland culture to the southern Levant. In the archeological records, cult-related materials can be linked with public-temple cults and religion or domestic cults. Another possibility could be cultic activity related to industrial production and technology. This paper will discuss links between industry and cults in several Philistine sites, in particular at Tel Miqne-Ekron and Tel Ashdod. These links are mostly associated with evidence from the Iron Age II (ca. 1000–600 BCE). The olive oil production center and the Temple Complex at Ekron, as well as several installations related to pottery production at Ashdod, will be discussed. While the temple cult in Iron Age Philistia has shown mainly Canaanite cultural elements so far, with very few originating in the Aegean, the domestic cult artifacts from the early Iron Age (ca. 1200–1000 BCE) show more Aegean-related elements. The industry-related cultic activity may possibly show a different pattern, or possibly a relationship to the Neo-Assyrian domination in the region during the late Iron Age. The socio-economic and administrative significance of these links will be discussed.

Keywords:

Philistia; Tel Miqne-Ekron; Tel Ashdod; olive oil; kilns; four-horned altars; zoomorphic vessels 1. Introduction

Philistia is a region in the southern coastal plains of the Levant (modern Israel), lying between the Mediterranean sea and the Shephelah hills, and between the brook of Egypt and the Yarkon river. During the Iron Age (ca. 1200–600 BCE), this area exhibited a distinct material culture, as well as a special historical background related to biblical texts (books of the Judges and 1Sam), often illustrating the Philistines as an enemy of the Israelites, as well as Egyptian texts mentioning this group as one of the “Sea Peoples” (e.g., T. Dothan 1982; Knauf 2001). In fact, the Philistines occupying this region during the Iron Age I (ca. 1200–1000 BCE) may have been immigrants from the west (Cyprus and the Aegean), bringing elements of their motherland culture to the southern Levant (e.g., Yasur-Landau 2010). The archeological record indicates that certain elements in the material culture related to domestic cults show influences from these regions, while the more public or temple cults are less influenced (Ben-Shlomo 2019; see below).

In the archeological records, cult-related material culture can be linked with public-temple cults and religion or to domestic cults. Temple cults involve activities conducted in a designated space or temple, are assumed to represent the more official and public religion, and may include special architectural characteristics, installations, and some designated more costly artifacts. Domestic cults involve activities conducted in regular households (or other spaces) and may represent a more popular cult or religion and include mostly small artifacts, which are less costly (as clay figurines). Another category could be cultic activity related to industrial production locations and technology. In relation to the archeological record, ‘industry’ (which will be the default term henceforth used for all types of evidence of production activities) can be defined as an economic activity concerned with the processing of raw materials and production of goods and finished objects in workshops or factories. Archeologically, relationships between industry and cult could occur where cultic items or installations or spaces are located within or in relation to industrial installations; or, when there is evidence for an industrial activity in situ within temples or cultic spaces. The background for these connections involves the mythical, elite, or lucrative associations certain technologies or industries may have (for metallurgy, see, e.g., Yahalom-Mack et al. 2014; Alberghina 2023; Susnow and Yahalom-Mack 2023), or the industrial production of artifacts related to cult itself (involving the production of various ceramic vessels and artifacts used in cults). In this case, this evidence may be considered as part of a ‘temple cult’. Another link between industry and cults may be related to the need for religious, divine and/or administrative protection, blessing or controlling (and its justification) the industry (in a commercial situation). In this case, the function of the cult may resemble a domestic cult, as the function of the space where used by the cult was not designated for a cult. A combination of both can appear when a cultic structure or space is defined with or in relation to an industrial area or a workshop. Yet, as industry can have significant economic importance, and therefore be under the control of the administration, state, or ruling power, cultic activities may have a more formal or public nature.

This paper will discuss links between cult and industry in the region of Philistia during the Iron Age by focusing on several sites in Philistia, in particular at Tel Miqne-Ekron (henceforth Ekron) and Tel Ashdod. These links are mostly associated with evidence from the Iron Age II (ca. 1000–600 BCE), such as the olive oil production center and the temple complex at Ekron, and several installations related to pottery production at Ashdod. Other possible instances of cult artifacts related to industries or production installation in Philistia will also be examined.

2. The Philistines and Their Cult

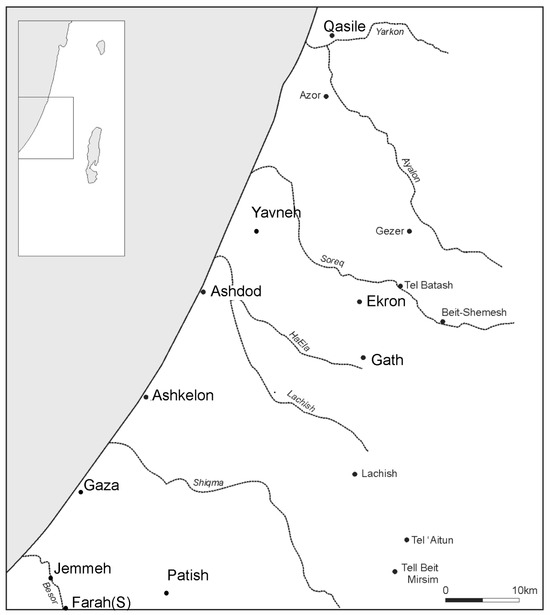

The Philistines are a group of people mentioned in the Old Testament, especially in the books of Judges and 1Sam. They are described as foreigners coming from ‘Kaphtor’ and settling in five main sites (the ‘pentapolis’): Gaza, Ashkelon, Ashdod, Ekron, and Gath, in the southern coastal plains of Israel (Figure 1; for example, T. Dothan 1982, pp. 13–20; Dothan and Dothan 1992, pp. 3–11). They are usually mentioned in relation to conflicts with the Israelites during the tribal stage and early monarchy, eventually subdued by King David (e.g., Knauf 2001). In Egyptian texts, the Philistines (Pršt) are mentioned as one of the ‘Sea Peoples’, creating disorder during the 13th–12th c. BCE, eventually subdued by Ramesses III (e.g., T. Dothan 1982, pp. 1–13; Dothan and Dothan 1992, pp. 13–28). During the Iron Age II, local kings of Philistine cities such as Ashdod and Ekron are mentioned in Neo-Assyrian texts (e.g., Tadmor 1966; Ehrlich 1996).

Figure 1.

Map of Philistia with sites mentioned in text.

Archaeological excavations were conducted in four of the five main Philistine cities (Gaza excluded) reaching Iron Age levels, as well as other smaller regional sites (Figure 1). The Philistine material culture can be considered to be a typical example of where a distinct material culture appears in a limited geographical and chronological context. This culture reflects the arrival of new population from the west, the Aegean region and/or Cyprus, to the southern coast of Israel during the early Iron Age. This is evidenced by material culture components which are not found in the local cultures of the southern Levant in the Late Bronze Age and early Iron Age, showing links to the Aegean region and Cyprus, thus probably indicating the arrival of an immigrant population during the beginning of the 12th century BCE (e.g., T. Dothan 1982; Dothan and Dothan 1992; Yasur-Landau 2010; Ben-Shlomo 2010; more references therein). During the Iron Age II, the material culture of Philistia changes, and many of the elements attesting to links with the West disappear (e.g., T. Dothan 1982). Nevertheless, the main Philistine cities known from the Iron Age I are still the major sites to be considered during Iron Age II, and display administrative independence and variable regional characteristics in their material culture during the different sub-periods of the Iron II (e.g., Ehrlich 1996; Shai 2006; for example, a distinct decorated pottery group, Ben-Shlomo 2010, pp. 174–75).

In the biblical texts, the religion, cult and gods of the Philistines are mentioned several times. This includes the temples of Dagon at Gaza (Judges 16:23) and Ashdod (1Sam 5) (see Singer 1992), while Ba’al Zebub of Ekron is also mentioned (2Kgs 1, 2–3). Cult and religion in Philistia is also evidenced in several manners in the archeological record (see, e.g., Ben-Shlomo 2019). It should be noted that there is no further evidence for the worship of the Semitic god of Dagon in Iron Age Philistia. During the early Iron Age, no clear temples in the main Philistine cities were excavated, yet, at Tell Qasile on the north edge of the region, a temple with several phases was excavated (Mazar 1980, 1985). Its architectural plan seems to follow local, ‘Canaanite’, tradition, while the finds include anthropomorphic (female) and zoomorphic depictions, mainly libation vessels and stands. At Nahal Patish in northern Negev, a similar temple with somewhat similar finds is also dated to the 11th c. BCE (Nahshoni 2009). During this period, there is, however, evidence for a domestic cult in the main Philistine cities. This includes female and zoomorphic figurines, as well as zoomorphic libation vessels and possibly other artifacts showing Aegean or Western affinities (see, e.g., Ben-Shlomo 2019, pp. 9–15). During the Iron Age II, evidence for temples comes from other sites in Philistia, such as the Yavneh favissah (Kletter et al. 2010), and a temple at Tell es-Safi/Gath (henceforth Gath, e.g., Dagan et al. 2018). The presence of domestic cults in Iron Age II Philistia are evidenced by figurines and figurative vessels and stands, mostly in the Canaanite local tradition (e.g., Ben-Shlomo 2019, pp. 15–16). Yet, the most important evidence comes from the Iron Age IIC (the Iron Age II can be divided into sub-periods: IIA: ca. 1000–800, IIB: ca. 800–700, and IIC: ca. 700–600 BCE): The 7th century BCE temple complex at Ekron, which also includes a dedicatory royal inscription mentioning a Philistine goddess (see below).

Industry and new technologies appearing in Iron Age Philistia were discussed recently in an article by Maeir and others (Maeir et al. 2019). Direct evidence includes, for example, pottery kilns and workshops appearing during the Iron Age I (e.g., Ekron, Tell Jemmeh; see Killebrew 1996) and Iron Age II (as at Ashdod, M. Dothan 1971, see below); metallurgy, which includes evidence for furnaces, slags, and the casting of copper, and certain evidence for iron smithing during the Iron Age II (e.g., Eliyahu-Behar and Workman 2018; Maeir et al. 2019, pp. 82–84); textile production, characterized by special types of loom-weights during the Iron Age I (e.g., Mazow 2006–2007; Cassuto 2018; Maeir et al. 2019, pp. 99–100); and bone and ivory working (Horwitz et al. 2006; Maeir et al. 2019, pp. 101–2); and flint (Maeir et al. 2019, p. 105). It is possible that those most relevant to this study are the industries and technologies related to agriculture, in particular, the olive oil industry at the site of Ekron, representing substantial advances in this technology and the manufacturing of olive oil on a very-large-scale industrial manner during the final Iron Age period (e.g., Gitin 1995; Faust 2011; Maeir et al. 2019, pp. 89–92; see below). As will be shown, most evidence linking industry and cult at Philistia comes from the Iron Age II.

3. Industry and Cult in Philistia

3.1. Tel Miqne-Ekron

3.1.1. Iron Age I

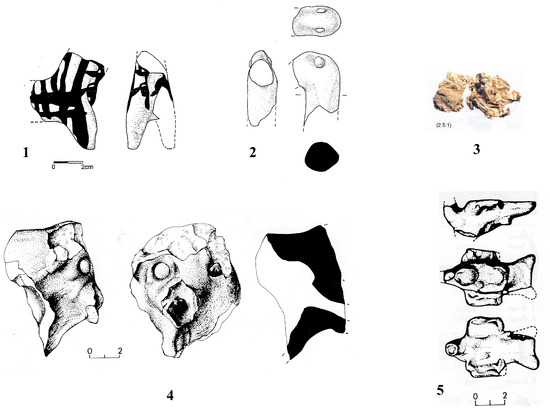

Several figurative objects, mostly fragments of zoomorphic vessels and figurines, were found in or near Iron Age I pottery kilns at Ekron (Figure 2(1–3)) (Strata VI, V; Killebrew 1996). These include a fragment of a bovine figurine, decorated in the Mycenaean IIIC monochrome style, found near Kiln 37015 in Field INE Stratum VI, upper city (Figure 2(1); Ben-Shlomo 2025, pp. 202, 462, Figure 5.19:4, Obj. No. 1739). A ceramic miniature jar, probably from a libation vessel or kernos, and a ceramic bird head (Figure 2(2), likely from a bird-bowl; Ben-Shlomo 2025, p. 459, Obj Nos. 4743, 4742, Figure 5.17:1), were both found in Kiln 3115, Field ISW, Stratum VC, the upper city. A figurine head decorated with red stripes (potentially representing a muzzle) was found near Kiln 4119 in Area INW, Stratum VIII–VII (Ben-Shlomo 2025, p. 466, Obj. No. 4451). A complete undecorated bovine figurine was found in a bathtub, possibly an installation, in Field INE, Stratum VII (Ben-Shlomo 2025, p. 462, Obj. No. 6978, L. 68047). A piece of a gold foil was found in Stratum VII kiln in Area INE (Figure 2(3); Ben-Shlomo 2006, p. 195, Figure 5.3:4, L. 37045, Obj. No. 6887); as a very rare item, it might be related to a cult. While the contexts of these findings may be coincidental, it should be noted that two of the items were found in the same spot, and also that the Aegean-style monochrome decorated bovine figurines (Figure 2(1)) are very rare (Ben-Shlomo 2010, pp. 100–4). In dealing with the contexts of Late Cypriot female and zoomorphic figurines, Begg noted that some of the Mycenaean-type bovine figurines are found in domestic contexts, while others are related to cultic contexts, mainly in relation to industrial and metallurgical installations (Begg 1991, p. 63, Type III.1). During Iron Age II, ‘Ashdoda’ figurines and libation vessels were also found near or in relation to pottery kilns in higher quantities (see below).

Figure 2.

Cultic finds from kiln contexts; Ekron and Ashdod (1—after Ben-Shlomo 2025, Figure 5.19:4; 2—after Ben-Shlomo 2025, Figure 5.17:1; 3—after Ben-Shlomo 2006, Figure 5.3:4, courtesy of Seymour Gitin; 4—after Dothan and Porath 1993, Figure 35:11; 5—after Dothan and Porath 1982, Figure 6:4).

Certain elements of metallurgic technology during the Iron Age period in Philistia were linked with cults (T. Dothan 2002). In particular, a group of bronze and iron objects from Building 350 at Field IV, Strata V–IV at Ekron. These include an iron knife, three bronze wheels, probably part of a stand or a cart, with parallels from Cyprus, possessing a cultic function, and a linchpin. Several iron knives with ivory handles and bronze rivets were found at Ekron (four handles, one related to the iron knife; one handle was reported to also have been found in an area related to industry near the fortification, T. Dothan 2002, p. 16), as well as other Iron Age I sites in the southern Levant. Also, 21 loom-weights were found in Room A of Building 350 (Ackerman 2008, p. 20). Yet, the interpretation of Building 350 at Ekron as a temple is a somewhat circular argument, since its architecture does not differ too much from domestic houses. Also, there is no clear industrial evidence in this area, save from a large iron object, possibly an ingot (T. Dothan 2002, p. 13). It is probable that some of the background for the links some scholars made between iron metallurgy and the Philistines and their cult during the Iron Age I is based on the biblical passage in 1Sam 13:19–20 (see also 1Sam 16:5–7). Metallurgy was linked with other cultic Bronze Age contexts in the Levant and Cyprus (see Begg 1991 and below). Recently, however, it has been shown that there is no special evidence for metallurgical or iron technological innovations at Philistia, neither in workshops, installations, or in objects (e.g., Maeir et al. 2019, see below).

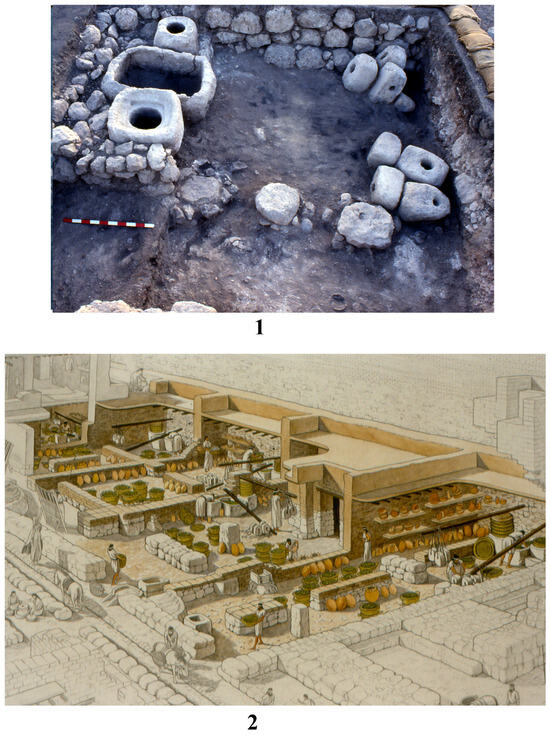

3.1.2. Iron Age II: The Olive Oil Industry

During the final phase of the Iron Age, the Iron IIC (701–604 BCE), the site of Ekron largely expanded back to the areas settled during the Iron Age I (Strata IC–IB, Fields III and IV in the lower city) to about 20 ha, and the fortifications were restored (e.g., Gitin 1995); the upper city was also rebuilt. On and around Tell 115, olive oil installations or factories were found (several were excavated in Field III, others were identified in the survey, Eitam 1996). Each factory had one olive oil installation and two other rooms (Figure 3(1)). The installations included a large stone basin flanked by a stone press and four 90 kg stone weights for crushing and pressing (Figure 3(1); mostly in Field III, Eitam 1996; Gitin 1993, p. 1056; Gitin 1993, 1995, 2003). In their vicinity, storage jars and loom-weights were found, and they are reconstructed within structures (Figure 3(2), as a reconstruction of the factory near the city gate; for example, Gitin 1995, Figure 4.3). These factories may reflect a production capacity of 500–1000 tons, making Ekron the largest industrial center for the production of olive oil in the Near East thus far excavated.

Figure 3.

The olive oil industrial area at Ekron (Field III): 1—a factory with installations; 2—reconstruction of the olive oil factory (courtesy of Seymour Gitin).

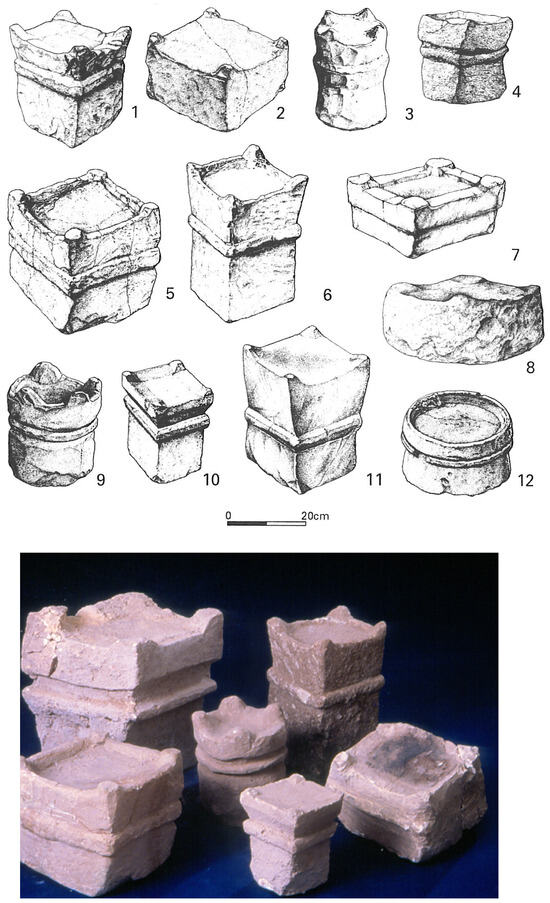

Cultic elements include an assemblage of four-horned limestone altars found in relation to these installations (Figure 4; Gitin 1989, 2002, 2009); of at least 17 items from Ekron, at least 10 were found in the industrial zone. These are carved limestone objects, with a usually cubic or nearly cubic shape and smoothed surfaces, free-standing, usually 10–30 cm in each dimension (one was bigger, 1.2 × 1.2 × 1.66 m), a concave top, and usually four horns protruding from the top (Figure 4). Their small size and weight make these a portable cultic object rather than a fixed installation. In the industrial zones, the four-horned altars were found near the entrances to the anterooms in each building in which olive oil and possibly textiles were produced (Gitin 1989, 2002). In one building, a four-horned altar was set into a niche constructed of small stones. Another building had two altars, as well as several well-hewn stones that could have been unfinished altars, perhaps indicating an altar workshop. In the northern industrial zone, two altars came from one room. Some of the altars may have been located on the roofs of buildings. Several altars found on the surface of the tell were adjacent to olive oil installations. Also, in a domestic zone, a horned altar and an altar without horns can be related to courtyards which produced coarse-ware ceramic vessels. Therefore, these stone incense altars, also appearing in other Iron Age II contexts in Judah and Israel (Gitin 1989, Table 1) were likely part of more popular cultic activities, not confined to temples. Their high number during the Iron Age IIC and their contexts link them to the olive oil industry at Ekron (see also Ben-Shlomo 2019, pp. 18–19). Note that three similar altars were found in the Ashkelon Iron Age IIC commercial area (Gitin 2009; Stager et al. 2011); this may be another link between cults and the trade of products—found here in the port distributing the produced goods.

Figure 4.

Four-horned portable incense altars from Ekron (courtesy of Seymour Gitin).

Gitin suggested that the altars were used in the administration of the industry, perhaps by the local priestly class on behalf of the royal authority, since only a strong centralized authority would have had the necessary resources and power to organize such extensive industrial facilities and to obtain such a large market and distribution system fit for the high levels of production (Gitin 1989, p. *60). This centralized authority, clearly evidenced by the contemporary Temple Complex 650 in Field IV (see below), was possibly controlled or highly influenced by the Neo-Assyrian empire authorities. Gitin also suggested that since similar altars were found at the north in the Kingdom of Israel (during the Iron Age IIA—early IIB), and since at Ekron all the finds are dated later, these artifacts at Ekron may indicate a northern influence on cultic behavior, possibly due to former Israelite workers employed in the olive oil industry (Gitin 1989, p. 61*). In any case, these portable altars could be seen as representing cultic activities carried out by workers, local work-managers or priests, probably in relation to obtaining affirmation and success from the gods in the olive oil production. The altars were probably used for burning incense. Whether the cult was also involved in using the olive oil produced is an unresolved question; yet, as will be seen, libation vessels are also linked to the olive oil production contexts at Ekron (see below).

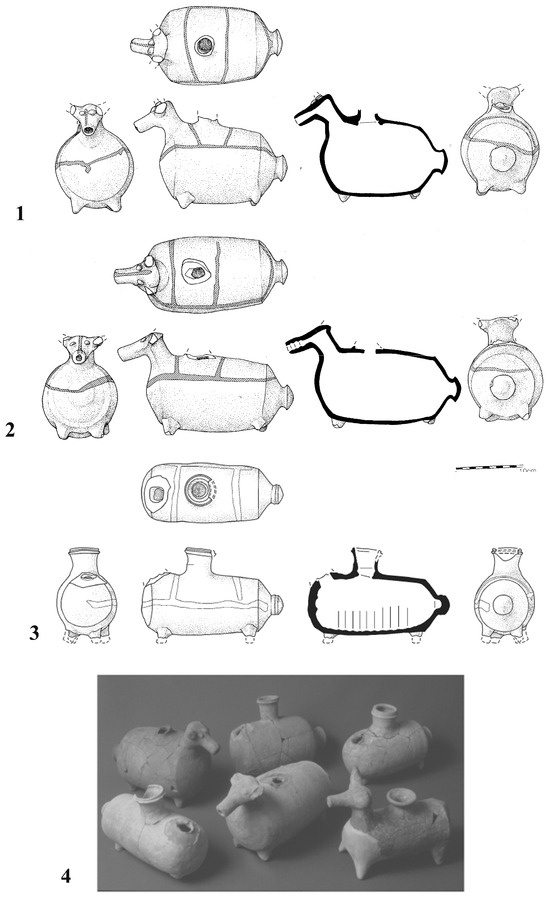

Another class of cultic items found in the olive oil industrial area is the bovine libation vessels (Figure 5; Ben-Shlomo 2010, pp. 111–14, Figures 3.58, 3.59; Ben-Shlomo 2025, pp. 193–95, 216, 445–48, Figures 5.2–5.4, 5.12, Type A.1.3). Two complete vessels (Figure 5(1,2)) and at least seventeen fragments were found in the olive oil industrial area in Field III and tills above it (in addition, thirty-six fragments of other types of zoomorphic vessels or figurines were found in Field III Iron Age IIC layers). The type is distinguished by a large barrel-shaped body, ca. 25 cm long and 16 cm high, with a capacity of ca. 1 l., an elongated snout, a wheel-coiled body, button-shaped tail, and reddish harness decoration (Figure 5(1,2)); the vessels are unslipped and have no handle. The animal is modeled rather schematically, the horned head and symbolic tail are emphasized, but the dewlap and other body details are absent. The standardized shape, style, and size of these vessels may imply that they were mass-produced. Their relatively large capacity compared, for example, to Iron Age I vessels may also indicate that they were used as both containers and libation vessels. Two complete vessels were recovered from a Stratum IB olive oil factory in Field III (Figure 5(1,2); Ben-Shlomo 2025, pp. 188, 193, Figure 5.2:1–2, Obj. No. 7663). An almost complete vessel (Figure 5(1), Obj. No. 7663) was found in a basin in Field IIINE, Stratum IB. The basin (L. 12032), under olive oil press weights, which was in secondary use and contained a mixed assemblage of artifacts. Here, as with the portable altars, on top of the circumstantial evidence, the fact that a specific type of cultic object with high standardization appears within the olive oil industry in space and time indicates a link to a cult. Therefore, there is a high probability that the objects were used in relation to it, maybe in the same context as the incense altars. In the case of the libation vessels, they were filled with liquids, and possibly with olive oil. In the case of the bovine libation vessels from Ekron, the bull may also represent an agricultural/industrial fertility symbol, a specific deity, or the deity’s vehicle (see, e.g., Ben-Shlomo 2010, p. 168; 2019, pp. 18–19).

Figure 5.

Bovine libation vessels from Ekron (after Ben-Shlomo 2025: 1—Figure 5.2:1, 2—Figure 5.2.2, 3—Figure 5.3:1; 4—group photo after Ben-Shlomo 2010, Figure 3.59; courtesy of Seymour Gitin).

3.1.3. The Temple Complex 650

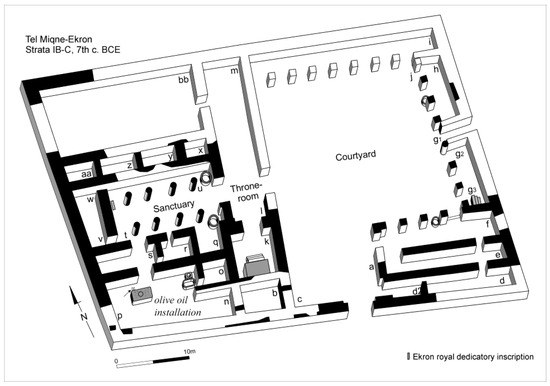

The hallmark of this period at Ekron is the temple complex in upper Field IV (Complex 650) (Figure 6; Gitin 1993, 1995, 2003; Gitin et al. 2022), built directly above a series of Iron I public buildings (Gitin 2003, pp. 284–86), in the lower city. The complex, sized 38 × 57 m, comprises a large columned courtyard, and a rectangular temple with a columned hall and an inner cella; in front of it, a ‘throne room’ is defined, while it is flanked on both sides by several storage rooms (Figure 6: rooms bb,n,x–aa). The structure was destroyed by the Babylonians in 604 BCE. There were several auxiliary buildings, also for public use, attached to it (Buildings 651–655, Gitin et al. 2017, pp. 8–26, Block Plan 2). The main building and the additional auxiliary structures contained thousands of storage jars and other vessels, caches of silver and iron, a Phoenician figurine, stone altars, silver hoards, and a large number of ivory objects, some of them very large, and probably dated to and sourced from the Late Kingdom of Egypt (Gitin et al. 2022). In the complex, in the cella of the temple, a royal dedicatory inscription of Padi, king of Ekron, was found (Gitin et al. 1997). It reads: The house (which) Akhayush (Ikausu/Achish), son of Padi, son of Ysd, son of Ada, son of Ya’ir ruler sar of Ekron, built for Pythogaia (Ptgyh), his lady. May she bless him, and protect him, and prolong his days, and bless his land.’ The royal inscription from Ekron is of primary importance, since it mentions both the Philistine king (mentioned both in Assyrian texts and 1Sam, also with the biblical tile sar [seren] = סר) and the dynasty of Ekron and the goddess of Ekron, having an Aegean name: Ptgyh, possibly related to the Aegean Potnia, meaning ‘the lady’ (e.g., Schäfer-Lichtenberger 2000). This temple complex shows possible Assyrian affinities in its plan, while the sanctuary resembles Kition’s Phoenician temple (e.g., Gitin 1995, 2009; Gitin et al. 2022). The complex probably administrated olive oil production at the site, which is estimated to be the largest of its period in the Near East. This industry may have been conducted under either the auspices or the direct control of the Assyrians in the earlier part of this period (Stratum IC, the early 7th c. BCE). During the latter part of the 7th century (Stratum IB), while the Assyrian empire fell and the Egyptians returned to control parts of Canaan, the structure and the industry continued, probably under local administration (see the Discussion section below). The fortified settlement and olive oil industry of nearby contemporary Tel Batash (Stratum II) should be understood in relation to the prosperity of Ekron (Mazar and Panitz-Cohen 2001, pp. 281–82).

Figure 6.

Schematic plan of Temple Complex 650 at Ekron (courtesy of Seymour Gitin).

In the elite zone of the temple complex (Gitin et al. 2017), two four-horned altars were next to the entrances to two rooms (the elite characteristics of this zone are also attested by its high percentage of decorated wares and small closed and open vessels, and the fact that it was the only excavation area yielding Assyrian and East Greek forms, as well as two caches of jewelry). Also, an altar without horns was found in this area, dating from an earlier period—the 11th/10th centuries BCE—at which time it was also an elite zone, as attested by the finds in Stratum IV (Gitin 1989). The Stratum IB destruction level of Temple Complex 650, containing also a sanctuary, yielded eight bovine libation vessels, one of which is a complete zoomorphic vessel (Figure 5(3), Obj. No. 9640; Ben-Shlomo 2010, Figure 3.59:1), found in a room immediately behind the cella (Figure 6: Room v). An inscription, “for Baal and for Padi”, was found on a storage jar shard in one of the side rooms of the sanctuary in Temple Complex 650 (Gitin and Cogan 1999); it reflects a dedication in the manner ‘to God and king/country’. One of the rooms (Figure 6: Room p) contained an olive oil installation—the only one found in situ outside of the industrial zone (Gitin et al. 1997, p. 7; Gitin et al. 2022, pp. 19–20, Photos 2.40, 2.46–2.48). Special finds in this room that may related to cult include an Egyptia baboon faience figurine (Gitin et al. 2022, Color Photo 6.2:1), as well as several ivory objects including a large head from an Egyptian Middle Kingdom statue or harp (Gitin et al. 2022, Photo 2.40).

The auxiliary buildings around Temple Complex 650 (Buildings 651–655, Stratum IB) yielded, as well as the massive amount of storage jars, inscriptions (Gitin et al. 2017, pp. 19–21), several four-horned altars, as well as installations related to olive oil production, and loom-weights related to textile production (Gitin et al. 2017, pp. 22–26, Photos 1.8–1.11, 1.21, 1.24–1.29, 1.31; in particular in Building 652). Altogether, 17 items related to olive oil production (sone weights and basins) were found in Buildings 651–655, and are assumed to be mostly in secondary use (Gitin et al. 2017, pp. 8–9). Yet, even if they have not been used for oil production in this context, their being carried from the industrial zone reflects the strong linkage between the industry and the temple complex. Several of the inscriptions have šmn or š for oil (shemen), and few note the volume unit bt/bat (32 l. capacity, Gitin et al. 2017, p. 23).

It should be noted that the industrial zone at Ekron and the temple complex related to it may illustrate another industry on top of olive oil: textiles (Gitin 1993, p. 1058; Ackerman 2008, p. 24; see Figure 3(2) for a reconstruction). This is due to the large number of loom-weights found. Gitin suggested that, as olive oil production is a seasonal industry (late Autumn), the spaces and maybe some installations were used for a large-scale textile industry outside of the olive season (Gitin 1993, p. 1058; Ackerman 2008, pp. 24–25).

While the Temple Complex 650 and the elite zone surrounding clearly had a cultic function on top of its administrative one, it is not technically an industrial area; yet, the links to industry at Ekron, namely the olive oil, are apparent. As noted, the justification of this large and regionally unique administrative, redistribution, cultic center is very likely related to the contemporary massive olive production in Ekron and its vicinity. The fact that olive oil production installations are scattered within and in the vicinity of the temple supports this assumption (see above).

3.2. Tel Ashdod

3.2.1. Iron Age I

As in Ekron, not much evidence linking industry and cult comes from the Iron Age I Tel Ashdod. In Area G on the top of the tell, Stratum XII, several domestic (?) structures were built adjacent to the fortification wall (Dothan and Porath 1993). In a courtyard of a house (Dothan and Porath 1993, p. 72, Plan 10), several industrial elements are present, including a kiln (L. 4136) and a basin (L. 4141); finds include basalt grinding stones, spinning bowls, and a glass ingot (Dothan and Porath 1993, Figure 35); a possibly cultic object is a zoomorphic libation vessel with a head spout (‘rython’) found in the basin (Figure 2(4); Dothan and Porath 1993, Figure 35:11). In Area H on the western slope of the tell, several domestic structures in Stratum XII–X contained various cultic artifacts such as figurines and stands (Dothan and Ben-Shlomo 2005, Buildings 5337, 5128, 5233). These structures sometimes contained installations of unknown function, possibly industrial. The Musician’s Stand was found in an open area of Stratum X, near several tabuns (baking installations) (Dothan and Ben-Shlomo 2005, pp. 180–84). However, a clear link between cult and industry was not found.

3.2.2. Iron Age II

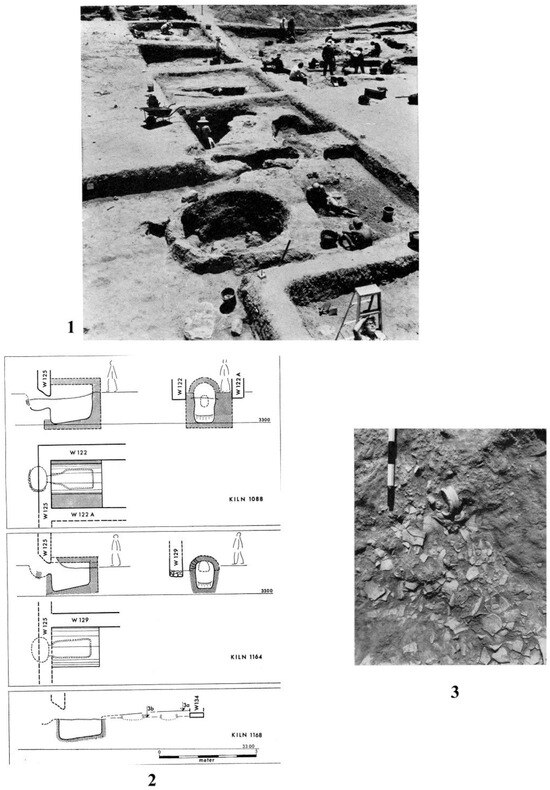

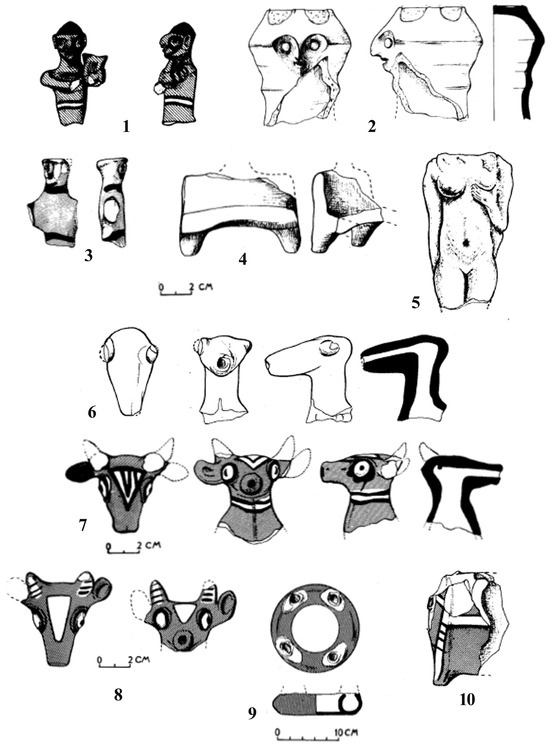

During the 8th century BCE (Iron Age IIB), Ashdod reached its peak, with remains of an industrial potter’s quarter and a possible cultic area in the southern lower city (Area D, Figure 7(1,2)). This area was destroyed during the late 8th c. BCE, specifically by Sargon II’s campaign in 712 BCE (Dothan and Freedman 1967, pp. 130–36; M. Dothan 1971, pp. 86–92), with evidence of mass burials recorded. In Strata VIII–VII of the 8th–7th c. BCE, an industrial area was located here, with several pottery kilns (Figure 7(1,2); M. Dothan 1971, pp. 88–94, Plans 11,12). Several cultic rooms were found in domestic or industrial buildings at Ashdod, Area D (Dothan and Freedman 1967, pp. 132–33, Plate xix) and Area K (Dothan and Ben-Shlomo 2005, p. 47). A large quantity of figurines and libation vessel fragments were found in the area, mostly from Strata VIII and VII (Figure 8; Hachlili 1971; M. Dothan 1971, Figures 62–73). Several pits in Stratum VII (Figure 7(3), M. Dothan 1971, Plan 8, Pits 1067, 1096, 1115, 1122) contained two or three examples of ‘Ashdoda’ figurine seat fragments each (Figure 8(4)), as well as plaque figurines of the Canaanite tradition (Figure 8(5)) and many zoomorphic head spouts possibly fromkernoi ring vessels (Figure 8(6–10); Dothan and Freedman 1967, pp. 130–36, Figures 42:17–19, 43–47, Plates 28–30, a total of 36 objects were shown in the plates; M. Dothan 1971, Figures 62–73, a total of 97 objects). Altogether, 133 figurative objects, including plaques and other figurines (including a lyre player, Figure 8(1); M. Dothan 1971, Figure 62:1), libation vessels in the shape of humans (Figure 8(2)) and animals and kernoi, were found in these contexts (Figure 8(6–10)), mostly in Stratum VII pits as well as in later and unstratified contexts. It should be noted that most of the items can be clearly typologically attributed to the Iron Age II; some are late ‘Ashdoda’ or Aegean-style figurines (Figure 8(3,4); M. Dothan 1971, Figures 63, 65:10–13). Some of the libation vessels carry the typical “Late Philistine” or “Ashdod ware” decoration (Ben-Shlomo 2010, pp. 107–9), with white and black decoration over a red slip (Figure 8(7,8,10); for example, M. Dothan 1971: Figures 68–70). Generally, the quantity and variability of figurative ceramic objects is very high, with anthropomorphic male and female figurines, anthropomorphic and zoomorphic (bovine, equine, bird) figurines and mostly libation vessels, and of Aegean (Figure 8(3,4)) and Canaanite (Figure 8(5)) styles (Hachlili 1971; Ben-Shlomo 2010). While most of the figurines and other cultic vessels came from Stratum VII, postdating the main use of the kilns, some of the kernoi (ring vessels with figurative spouts, Figure 8(9)) and spouts came from Stratum VIII, representing the industrial kiln area, in relation to the kiln or even inside them (Hachlili 1971, pp. 125, 134–35; some come from the mass burial as well). The interpretation of these contexts as indicative of a possible Iron Age IIB cultic place near the city wall (similar to the one presented in Stratum VII: Dothan and Freedman 1967, pp. 133–34, Plan 7) cannot be ruled out. Yet, note that the pits postdate the cultic room (Dothan and Freedman 1967, pp. 132–33, Plate xix) and contain many other pottery vessels as well, and thus, may not be directly associated with the cultic structure, and more likely with the industrial activities in this area. Therefore, these pits could simply be refuse pits related to the industrial area with several pottery kilns (Ben-Shlomo 2010, pp. 121, 168), thus representing material discarded from domestic contexts. These objects were either produced in the kilns or used in cultic activities related to them and the industry in this area or were both.

Figure 7.

Ashdod Area D, an industrial area with kilns and pits (after M. Dothan 1971: 1—Plate 34:1; 2—Plan 12; 3—Plate 37:2).

Figure 8.

Figurines, libation vessels, and kernoi from Ashdod Area D (after M. Dothan 1971: 1—Figure 62:1; 2—Figure 65:6; 3—Figure 65:10; 4—Figure 63:4; 5—Figure 64:1; 6—Figure 67:3; 7—Figure 68:6; 8—Figure 69:6; 9—Figure 71:3; 10—Figure 72:1).

Area M at the lower city of Ashdod also contained a potters’ workshop from the Iron Age IIA period (Stratum X, Phase a, Kiln 7202, Phase b, Kiln 7028, Dothan and Porath 1982, pp. 7–8, 52, Plan 4). Here, a bird-shaped rattle may be a cult-related object (Figure 2(5); Dothan and Porath 1982, Figure 6:4). Several kilns were found in Area K on the western slope, Stratum VI, of the 7th–6th c. BCE (Dothan and Ben-Shlomo 2005, pp. 55–60), yet no cultic artifacts were related to them.

3.3. Ashkelon

3.3.1. Iron Age I

At Ashkelon Grid 38, an Iron Age I ‘house shrine’ was reported (Master and Aja 2011, within Building 572, Stratum 20, 12th c. BCE). It was identified as such because one of the rooms contained a lime-plastered earth installation, set against the wall, with four protrusions on its upper corners, appearing as a four-horned altar (Master and Aja 2011, Room 572, Installation 539). Nearby, the installation finds included a loom-weight, a pestle, and faience objects (Master and Aja 2011, p. 140). While interpreted as an altar, this installation could have also had some household industrial function, thus attesting to some link between cult and domestic industry.

3.3.2. Iron Age II

During the Iron Age IIC, a winery and a market place were excavated in Ashkelon Grid 38 (Stager et al. 2011). Three portable four-horned altars were found in this level, yet were possibly in secondary use (Gitin 2009). The winery (Stager et al. 2011, pp. 13–29) represents an agricultural industry, similarly and as a contemporary with Ekron. Cult-related finds in the winery include a Bes figurine, seven bronze situlae, and a model offering table from Building 776 Room 312 (Stager et al. 2011, p. 23, Figure 2.20; Bell 2011, pp. 397–405, Figures 13.1–13.3), as well as an Osiris bronze statue (Stager et al. 2011, p. 24, Figure 2.21; Bell 2011, pp. 415–16) from Room 413. Note that these cultic artifacts are all Egypt-related (Bell 2011). Bell suggested that these represent cult practices in a temple complex nearby, or even that the winery was part of a temple complex dedicated to the god Osiris, who is related to vegetation and resurrection, and also associated with wine in the Egyptian culture (Bell 2011, p. 416). However, there is as of yet no archeological evidence for this temple at Ashkelon.

3.4. Tell es-Safi/Gath

At Gath Iron Age IIA, temples were found in Area D of the lower city (two Phases, Strata D4-D3, Dagan et al. 2018), while a cultic conner was identified in Area A, in the upper city (Maeir et al. 2013, pp. 22–23). Two metallurgic workshops from the Iron Age IIA were identified at Areas A and D as well (Eliyahu-Behar and Workman 2018; Maeir et al. 2019, pp. 83–84, Figures 5 and 6); these workshops were associated with both bronze and iron metallurgy and smithing. In Area D, there is a proximity between the Stratum D3 temple and the workshop, and there was possibly a relationship between them (Dagan et al. 2018, p. 31; Eliyahu-Behar and Workman 2018). Evidence for textile production was also found in this area (Cassuto 2018, p. 57, Figure 2). About 300 loom-weights were found in the 9th c. BCE destruction layer. These were unearthed in large groups alongside concentrations of complete storage vessels, or stored in a niche above a division wall; therefore, most were stored and not attached to looms. Links between weaving and sanctuaries or temples in the ancient Near East (see Ackerman 2008; Cassuto 2018, p. 57) could be related to religious activities that required the production of garments for the “deities”/statues for which weavers were recruited on a temporary basis. Some ancient texts mention that spinning and weaving were recognized as female-specific activities, which had been imparted to them by the female deities (Ackerman 2008); these possibly include Asherah in the southern Levant, as mentioned in 2Kgs 23:7, “… women weaving for Asherah”, and possibly a Philistine goddess in the case of Philistia.

A bone workshop is dated to the Iron Age IIA (Horwitz et al. 2006; Maeir et al. 2019, p. 101, Figure 24); this is a quite unique finding. Bone and ivory items are often linked with elite classes, and possibly with cults (e.g., T. Dothan 2003), but there is no direct industry–cult link here.

3.5. Other Sites in Philistia

3.5.1. Tell Qasile

At Tell Qasile, 15 loom-weights were found in Room 204, Building 225, just north of Temple 131 of Stratum X (Mazar 1980, p. 42; 1985, p. 80; Ackerman 2008, p. 20). The room was identified as a kitchen, possibly for preparing ritual meals for the temple. Eleven additional loom-weights were found in other rooms of Building 225 (Ackerman 2008, p. 20). For the links between textile industry and cult, see above.

3.5.2. Yavneh

A large Iron Age IIA favissa with hundreds of cultic ceramic and other vessels and shrine models were found at Yavneh (e.g., Kletter et al. 2010). While no workshops are evidenced (and the actual temple was not found), compositional and style analysis indicate that the vast majority of the artifacts were made in the same workshop using standardized clay (Kletter et al. 2010, pp. 113, 156–57, 185, 196–97). Thus, this could be indirect evidence for a temple-related pottery workshop, producing cult objects, as known to be the case in several Bronze Age temples (e.g., Kletter et al. 2010, pp. 196–97; Susnow and Yahalom-Mack 2023).

4. Discussion

The evidence for links between industry and cult in Iron Age Philistia include several categories:

- Artifacts interpreted as cultic within or in close proximity to industrial activity areas, structures, or installations (Ekron Iron I and II, Ashdod). These could be divided into more clear evidence of cultic activities and artifacts in clear large-scale industrial areas, as in the Iron Age II Ekron olive oil industry, and more sporadic, possibly circumstantial cultic artifacts linked with kilns or other possibly industrial isolated installations, also in domestic contexts (Ekron, Ashkelon, Ashdod, Iron I).

- Industrial installations or evidence of activity within or in proximity to temples or cultic spaces (Ekron Iron I, II [650], Gath, Qasile).

- Other, more indirect evidence as evidence for temple workshops (Yavneh), or the production of cultic artifacts elsewhere (Ashdod, Iron II).

Interestingly, the more substantial evidence comes from the Iron Age II, when the Philistines were possibly more assimilated into the local population and traditions, while during the earlier Iron Age I periods, evidence is much more sporadic. An explanation for this will be suggested below.

Two types of cultic artifacts are particularly apparent in relation to industrial contexts, and the olive oil industry at Ekron: portable limestone four-horned altars, and large, barrel-shaped bovine libation vessels (Figure 4 and Figure 5, see above; also chalices, to a lesser extent). Supporting the links between industry in general at Ekron, and, in particular, regarding these two object types, is that both portable four-horned altars and this type of bovine libation vessel, while appearing in earlier periods and other contexts, are the most abundant during the 7th c. BCE, and commonly appear in the industrial zone and temple complex at Iron Age IIC Ekron. The nature of the cultic activity or ceremonies conducted using these artifacts is not entirely clear. They may represent several different rituals: possibly one related to incense burning, the other to liquid (olive oil?) libations, or components of one ritual.

While there is much evidence suggesting links between cult and bronze metallurgy during the Bronze Age in the Levant (as at Hazor, Nahariya, and possibly other sites; see, e.g., Susnow and Yahalom-Mack 2023, with more references therein), during the Iron Age it seems that both Bronze and Iron workshops were usually not linked with temples, and some examples show they were concentrated in the gated area, which is a more commercial area (Yahalom-Mack et al. 2014). In previous research, the Philistines were linked to a military dominated culture; the Philistine culture was responsible for metallurgical innovations possibly in relation to this, and, in particular, the introduction of iron metallurgy in the Levant (see, e.g., T. Dothan 1982, pp. 18–21). Nevertheless, this is not supported by the archeological evidence in Iron Age Philistia, as very few weapons were found; neither did Philistia yield more iron items than contemporaneous ones outside the region. The analysis of metallurgic workshops and several iron tools and weapons from Tell es-Safi/Gath indicate that the date and quality and skills related to iron production and smithing in Philistia were similar to other regions in the Levant (Eliyahu-Behar and Workman 2018; Maeir et al. 2019).

As noted, most of the links between cult and industry are evident during the Iron Age II, especially in the late part of this period (late 8th and 7th c. BCE), and they do not directly reflect traditions or artifacts brought from the western homelands of the Philistines. Several reasons can be mentioned to explain this. One simple, technical reason is that Iron Age II remains were exposed and were better preserved in larger areas in the main Philistine site, since they lie on top of the Iron Age I remains in most cases. Another possibly related issue is that no Iron Age I temple was exposed in the main Philistine cities. Nevertheless, there are probably other more cultural and socio-economic reasons. Both archeological and textual evidence indicates that during the Iron Age II, local, regional, and central administrations, as well as ‘secondary, ethnic states’, evolve in the southern Levant (as Israel, Judah, Ammon, Moab etc.; see, e.g., Finkelstein 1999; Joffe 2002). Philistia is part of this process, in particular during the Iron Age IIB-C, becoming an independent and important commerce center for the entire Near East, under the Neo-Assyrian influence and control and beyond (e.g., Tadmor 1966; Ehrlich 1996). The large Philistine ports of Gaza and Ashkelon linked the eastern Mediterranean and Arabia (Master 2003).

The large-scale olive oil industry at Ekron during the 7th c. BCE was probably part of this reality. There are different views about the initiation, interest, control, and maintenance of the massive olive oil industry at Ekron (as well as other sites of the Iron Age IIB-C Shephelah). It may have been initiated as part of the Neo-Assyrian imperial vassal system, flourishing during the ‘Pax Assyriaca’, and continuing through to the days past the Assyrian control in the final decades of the 7th c BCE (e.g., Gitin 1995; Na’aman 2003). Faust emphasized the role of the local ethnic states, in particular Israel, Judah, and Philistia, in the development of the olive oil industry, and the new trade routes and markets during this period (e.g., Faust 2011; Faust and Weiss 2005, 2011). In particular, Philistia with its large ports had a central role in the Maritime international trade, together with the Phoenician cities (e.g., Master 2003; Faust 2011). The royal inscription dedicating the temple at Ekron to a goddess with an Aegean name, by a Philistine king, supports the association of the temple complex, the elite zone, and related olive oil industry during this period with a local rather than an imperial administration. Whether the large-scale olive oil production and distribution system of Ekron was initiated, influenced, or controlled by the Neo-Assyrian empire, or by an enterprise of a local relatively independent enterprise, or a balance between the two, it had to be administrated by some central ruler, due to its scale (smaller-scale olive oil industries at Samaria and Judah may have operated differently, Faust 2011, pp. 66–70). This probably generated the need or justification for the temple complex as a redistribution and control center, and its religious and cultic characteristics, and other related cultic practices.

5. Conclusions

The more substantial archeological evidence for links between industry and cults in Iron Age Philistia comes from the Philistine city of Ekron during the late Iron Age II, 7th c. BCE. This includes Temple Complex 650 and its auxiliary structures, serving as an administrative center for the large-scale olive oil industry in the site, which was the largest of its kind in the ancient Near East. Cultic artifacts were also found in the industrial area and included portable four-horned altars and bovine libation vessels. This link between industry and cult or religion seems to be primarily based on the need for religious justification and support for this economic venture. Another link between industry and cult may come from Yavneh and Ashdod, also during the Iron Age IIB, which includes direct (Ashdod libation vessel and kilns) or indirect (shrine models and other terracotta, made in the same workshop) evidence of the ‘industrial’ production of cultic ceramic artifacts. Other evidences which are more circumstantial and sporadic come from various Iron Age I and II in Philistia, and are less significant; they include some links between metallurgy and an Iron Age II Temple as Gath as well.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

I wish to thank Seymour Gitin, excavator of Tel Miqne-Ekron, for his assistance and support.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Ackerman, Susan. 2008. Asherah, the West Semitic Goddess of Spinning and Weaving? Journal of Near Eastern Studies 67: 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberghina, Dalila M. 2023. Smelting Metals, Enacting Rituals. The Interplay of Religious Symbolisms and Metallurgical Practices in the Ancient Eastern Mediterranean, Asia Anteriore Antica. Journal of Ancient Near Eastern Cultures 5: 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- Begg, Patrick. 1991. Late Cypriote Terracotta Figurines: A Study in Context. SIMA 101. Jonsered: Paul Åströms Förlag. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, Lanny. 2011. A Collection of Egyptian Bronzes. In Ashkelon 3. The Seventh Century B.C. Edited by Lawrence E. Stager, Daniel M. Master and David J. Schloen. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, pp. 397–420. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Shlomo, David. 2006. Selected Objects. In Tel Miqne-Ekron. Excavations 1995–1996, Field INE East Slope: Late Bronze II-Iron I (The Early Philistine City). Edited by Mark W. Meehl, Trude Dothan and Seymour Gitin. The Tel Miqne-Ekron Final Field Report No. 8. Jerusalem: W.F. Albright Institute, pp. 189–205. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Shlomo, David. 2010. Philistine Iconography: A Wealth of Style and Symbolism. OBO 241. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Shlomo, David. 2019. Philistine Cult and Religion According to Archaeological Evidence. Religions 10: 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Shlomo, David. 2025. Zoomorphic Terracottas. In Ekron 14/1 Tel Miqne-Ekron Objects and Material Culture Studies: Middle Bronze Age II Through Iron Age II. Edited by Seymour Gitin. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, pp. 187–253, 444–72. [Google Scholar]

- Cassuto, Deboah. 2018. Textile Production at Iron Age Tell e-Sâfi/Gath. Near Eastern Archaeology 81: 55–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagan, Amit, Maria Enuikhina, and Aren M. Maeir. 2018. Excavations in Area D of the Lower City Philistine Cultic Remains and Other Finds. Near Eastern Archaeology 81: 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dothan, Moshe. 1971. Ashdod II–III. ‘Atiqot 10–11. Jerusalem: Department of Antiquities. [Google Scholar]

- Dothan, Moshe, and David Ben-Shlomo. 2005. Ashdod VI: Excavations of Areas H and K: The Fourth and Fifth Seasons of Excavation (1968–1969). Israel Antiquities Authority Reports 24. Jerusalem: IAA. [Google Scholar]

- Dothan, Moshe, and David N. Freedman. 1967. Ashdod I. ‘Atiqot 7. Jerusalem: Department of Antiquities. [Google Scholar]

- Dothan, Moshe, and Yosef Porath. 1982. Ashdod IV: Excavation of Area M. ‘Atiqot 15. Jerusalem: Department of Antiquities. [Google Scholar]

- Dothan, Moshe, and Yosef Porath. 1993. Ashdod V. Atiqot 23. Jerusalem: IAA. [Google Scholar]

- Dothan, Trude. 1982. The Philistines and Their Material Culture. Jerusalem: IES. [Google Scholar]

- Dothan, Trude. 2002. Bronze and Iron Objects with Cultic Connotations from Philistine Temple Building 350 at Ekron. Israel Exploration Journal 52: 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Dothan, Trude. 2003. The Aegean and the Orient: Cultic Interactions. In Symbiosis, Symbolism, and the Power of the Past: Canaan, Ancient Israel, and Their Neighbors from the Late Bronze Age through Roman Palaestina. Edited by William G. Dever and Seymour Gitin. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, pp. 189–213. [Google Scholar]

- Dothan, Trude, and Moshe Dothan. 1992. People of the Sea. New York: Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlich, Carl S. 1996. The Philistines in Transition. A History from ca. 1000–730 B.C.E. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Eitam, David. 1996. The Olive Oil Industry at Tel Miqne-Ekron during the Late Iron Age. In Olive Oil in Antiquity: Israel and Neighboring Countries from the Neolithic to the Early Arab Period. Edited by David Eitam and Michael Heltzer. Padua: Sargon, pp. 167–96. [Google Scholar]

- Eliyahu-Behar, Adi, and Vanessa Workman. 2018. Iron Age Metal Production at Tell es-Safi/Gath. Near Eastern Archaeology 81: 34–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faust, Avraham. 2011. The Interests of the Assyrian Empire in the West: Olive Oil Production as a Test-Case. Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 54: 62–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faust, Avraham, and Ehud Weiss. 2005. Judah, Philistia, and the Mediterranean World: Reconstructing the Economic System. Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 338: 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faust, Avraham, and Ehud Weiss. 2011. Between Assyria and the Mediterranean World: The Prosperity of Judah and Philistia in the Seventh Century BCE in Context. In Interweaving Worlds: Systemic Interactions in Eurasia, 7th to 1st Millennia BC. Edited by Toby Wilkinson, Susan Sherratt and John Bennet. Oxford: Oxbow, pp. 189–204. [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein, Israel. 1999. State Formation in Israel and Judah. Near Eastern Archaeology 62: 35–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitin, Seymour. 1989. Incense Altars from Ekron, Israel and Judah: Context and Typology. Eretz Israel 20: *52–*67. [Google Scholar]

- Gitin, Seymour. 1993. Seventh Century B.C.E. Cultic Elements at Ekron. In Biblical Archaeology Today, 1990. Edited by Avraham Biran and Joseph Aviram. Jerusalem: IES, pp. 248–58. [Google Scholar]

- Gitin, Seymour. 1995. Tel Miqne-Ekron in the 7th Century B.C.E.: The Impact of Economic Innovation and Foreign Cultural Influences on a Neo-Assyrian Vassal City-State. In Recent Excavations in Israel: A View to the West: Reports on Kabri, Nami, Miqne-Ekron, Dor and Ashkelon. AIA Colloquia and Conference Papers 1. Edited by Seymour Gitin. Dubuque: Kendall/Hunt Pub. Co., pp. 61–79. [Google Scholar]

- Gitin, Seymour. 2002. The Four-Horned Altar and Sacred Space: An Archaeological Perspective. In Sacred Time, Sacred Space: Archaeology and the Religion of Israel. Edited by Barry M. Gittlen. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, pp. 95–123. [Google Scholar]

- Gitin, Seymour. 2003. Israelite and Philistine Cult and the Archaeological Record: The “Smoking Gun” Phenomenon. In Symbiosis, Symbolism and the Power of the Past: Canaan, Ancient Israel, and Their Neighbors from the Late Bronze Age through Roman Palaestina. Edited by William G. Dever and Seymour Gitin. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, pp. 279–95. [Google Scholar]

- Gitin, Seymour. 2009. The Late Iron Age II Incense Altars from Ashkelon. In Exploring the Longue Durée: Essays in Honor of Lawrence E. Stager. Edited by David Schloen. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, pp. 127–36. [Google Scholar]

- Gitin, Seymour, and Mordechai D. Cogan. 1999. A New Type of Dedicatory Inscription from Ekron. Israel Exploration Journal 49: 193–202. [Google Scholar]

- Gitin, Seymour, Steven M. Ortiz, and Trude Dothan, eds. 2022. Tel Miqne-Ekron Excavation 1994–1996. Field IV Upper and Field V—The Elite Zone. Volume 10, Part 1: Iron Age IIC Temple Complex Complex 650. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns. [Google Scholar]

- Gitin, Seymour, Trude Dothan, and Joseph Naveh. 1997. A Royal Dedicatory Inscription from Ekron. Israel Exploration Journal 48: 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Gitin, Seymour, Trude Dothan, and Yosef Garfinkel, eds. 2017. Tel Miqne-Ekron Field IV Lower—The Elite Zone, The Iron Age I and IIC, The Early and Late Philistine Cities Volume 9, Part 2: The Iron Age IIC Late Philistine City. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns. [Google Scholar]

- Hachlili, Rachel. 1971. Figurines and Kernoi (Areas D H, Trench C1). In Ashdod II–III, ‘Atiqot 9–10. Edited by Moshe Dothan. Jerusalem: Department of Antiquities, pp. 125–35. [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz, Liora K., Justin E. Lev-Tov, Jeffrey R. Chadwick, Stefan J. Wimmer, and Aren M. Maeir. 2006. Working Bones: A Unique Iron Age IIA Bone Workshop from Tell es-Safi/Gath. Near Eastern Archaeology 66: 16–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joffe, Alex H. 2002. The Rise of Secondary States in the Iron Age Levant. Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 45: 425–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killebrew, Ann E. 1996. Pottery Kilns from Deir el-Balah and Tel Miqne-Ekron. In Retrieving the Past. Essays on Archaeological Research and Methodology in Honor of Gus W. Van Beek. Edited by Joe D. Seger. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, pp. 135–62. [Google Scholar]

- Kletter, Raz, Irit Ziffer, and Wolfgang Zwickel. 2010. Yavneh I: The Excavation of the ‘Temple Hill’ Repository Pit and the Cult Stands. OBO SA 30. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. [Google Scholar]

- Knauf, Ernst A. 2001. David, Saul, and the Philistines: From Geography to History. Biblische Notizen 109: 15–18. [Google Scholar]

- Maeir, Aren M., David Ben-Shlomo, Deborah Cassuto, Jeff B. Chadwick, Brent Davis, A. Eliyahu-Behar, Sue Frumin, Shira Gur-Arieh, Louise A. Hitchcock, Liora K. Horwitz, and et al. 2019. Technological Insights on Philistine Culture. Perspectives from Tell es-Safi/Gath. Journal of Eastern Mediterranean Archaeology & Heritage Studies 7: 76–117. [Google Scholar]

- Maeir, Aren M., Louise A. Hitchcock, and Liora Kolska Horwitz. 2013. On the Constitution and Transformation of Philistine Identity. Oxford Journal of Archaeology 32: 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Master, Daniel M. 2003. Trade and Politics: Ashkelon’s Balancing Act in the Seventh Century B.C.E. Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 330: 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Master, Daniel M., and Adam J. Aja. 2011. The House Shrine of Ashkelon. Israel Exploration Journal 61: 129–45. [Google Scholar]

- Mazar, Amihai. 1980. Excavations at Tell Qasile, Part One. The Philistine Sanctuary: Architecture and Cult Objects Qedem 12. Jerusalem: Hebrew University. [Google Scholar]

- Mazar, Amihai. 1985. Excavations at Tell Qasile II: Various Objects, the Pottery, Conclusions. Qedem 20. Jerusalem: Hebrew University. [Google Scholar]

- Mazar, Amihai, and Navah Panitz-Cohen. 2001. Timnah (Tel Batash) II. The Finds from the First Millennium BCE. Qedem 42. Jerusalem: Hebrew University. [Google Scholar]

- Mazow, Laura B. 2006–2007. Producing a Philistine: The Philistine Textile Industry and Its Implications for Reconstructing Philistine Settlement. Scripta Mediterranea 27–28: 53–80. [Google Scholar]

- Na’aman, Nadav. 2003. Ekron under the Assyrian and Egyptian Empires. Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 332: 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahshoni, Pirhiya. 2009. A Philistine Temple in the Northwestern Negev. Qadmoniot 42: 88–92. (In Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

- Schäfer-Lichtenberger, Christa. 2000. The Goddess of Ekron and the Religious-Cultural Background of the Philistines. Israel Exploration Journal 50: 82–91. [Google Scholar]

- Shai, Itzhak. 2006. The Political Organization in Philistia during the Iron Age IIA. In “I Will Speak the Riddles of Ancient Times” (Ps. 78:2b): Archaeological and Historical Studies in Honor of Amihai Mazar on the Occasion of his Sixtieth Birthday. Edited by Aren M. Maeir and Pierre de Miroschedji. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, pp. 347–59. [Google Scholar]

- Singer, Itamar. 1992. Towards the Image of Dagon, the God of the Philistines. Syria 69: 431–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stager, Lawrence E., Daniel M. Master, and J. David Schloen. 2011. Ashkelon 3. The Seventh Century B.C. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns. [Google Scholar]

- Susnow, Matthew, and Naama Yahalom-Mack. 2023. Metalworking in Cultic Spaces: The Emergence of New Offering Practices in the Middle Bronze Age Southern Levant. Tel Aviv 50: 194–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadmor, Hayim. 1966. Philistia Under Assyrian Rule. The Biblical Archaeologist 29: 86–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahalom-Mack, Naama, Yuval Gadot, Adi Eliyahu-Behar, Shlomit Bechar, Sana Shilstein, and Israel Finkelstein. 2014. Metalworking at Hazor: A Long-Term Perspective. Oxford Journal of Archaeology 33: 19–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasur-Landau, Assaf. 2010. The Philistines and Aegean Migration at the End of the Late Bronze Age. Cambridge: University Press. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).