Abstract

This study examines the construction of individual and collective identity in pre-Neolithic Egypt and the Levant through the post mortem manipulation of human remains. Focusing on funerary rituals and skull reuse, interpreted using recent anthropological theory frameworks, we propose a totemic framework of ontological identity, in which clans associated with specific animals structured their ritual and spatial practices. Based on archaeological, taphonomic, and ethnohistorical evidence, it is possible to identify how these practices reflect clan-based social units, seasonal mobility, and a reciprocal relationship with the environment, integrating corporeal and mental continuity. Plastered skulls in the Levant acted as intergenerational anchors of communal memory, while early Egyptian dismemberment practices predate the standardization of mummification and reveal the function of some structures of pre-Neolithic sanctuaries. By interpreting these mortuary rituals, we argue that selective body treatment served as a deliberate mechanism to reinforce totemic identity, transmit ancestry, and mediate ontological transitions in response to sedentarization and environmental change.

1. Introduction

Reconstructing the symbolic and ontological systems—that is, the identities—of prehistoric societies constitutes one of the final and most intractable challenges posed by the material basis of archaeology and by the various epistemological approaches that have been applied to the field in recent decades. The absence of writing, the fragmentary nature of the archaeological record, and the difficulty of establishing parallels between communities of divergent origin or chronology render cultural interpretation a complex endeavour, even though such interpretations should remain, ultimately, the guiding aspiration of all scholars within the human sciences. To ask how and why things came to assume the forms they did, rather than any other, must be regarded as a legitimate and necessary objective, and questions of identity are indispensable for understanding the forms, practices, and habits of ancient societies. Our knowledge of such societies can be significantly enriched when broader and more all-encompassing interpretative frameworks are applied.

The transition to the Neolithic represents, in this sense, a singular opportunity to address identities that predate sedentarization, since, for a time, older configurations became effectively petrified within the archaeological record of those societies undergoing transformation. Particularly within the Fertile Crescent—and owing to the results of excavations undertaken during the past three decades—diverse approaches have been brought to bear upon the problem of identity among these groups and upon the ontological models that underpinned their systems of belief, practice, and social configuration (Meskell 2008; Kuijt 2008; Sahlins 2014; Ibáñez et al. 2014; Santana et al. 2015; Busacca 2017; Croucher 2018; Graeber and Wengrow 2022; Nowell and Macdonald 2024; Clare 2024; Verhoeven 2025). Excavations at Göbekli Tepe and at neighbouring sites with parallel characteristics in the Upper Euphrates (Köksal-Schmidt and Schmidt 2010; Dietrich and Notroff 2015; Dietrich et al. 2019; Banning 2023; Mithen et al. 2023; Dietrich 2024), as well as the monumental ceremonial centres of the Jericho area (Hodder and Meskell 2011; Ibáñez et al. 2014; Santana et al. 2015; Haddow and Knüsel 2017; Mithen et al. 2023), have effected a veritable revolution in the interpretation of the symbolic and identity structures of communities in the course of transition toward full sedentarization and Neolithization.

For Egypt, by contrast, interpretative contributions have thus far been scarce (Wengrow and Baines 2004; Wengrow et al. 2014), in part because of the limited record available for the early Holocene societies of the eastern and western deserts of the Nile Valley, prior to the emergence of what would later be recognized as Pharaonic culture. However, the excavations of the last few decades (Wendorf and Schild 2001; Applegate et al. 2001; Bunbury et al. 2008, 2020; di Lernia 2006; Gatto 2012; Manning and Timpson 2014) nonetheless render possible the establishment of meaningful parallels with processes unfolding across the Fertile Crescent, thereby permitting more profound interpretations of the identities of the groups who were ultimately to configure one of antiquity’s greatest civilisations.

The purpose of this article is to advance a new interpretation of the ontological identities of these groups, grounded in the evidence offered by the treatment of the dead. More specifically, we attend to cases in which the body was subject to post mortem manipulation, accompanied by the secondary ritual deployment of particular body parts, as attested in both Fertile Crescent and Egyptian contexts of broadly contemporary date. In so doing, and in the absence of textual evidence that might otherwise guide interpretation, we turn to an anthropological theoretical perspective that has crystallized in recent decades and which may provide a valuable lens through which to reconsider these materials. This approach affords new interpretative possibilities by aligning the archaeological record with anthropological models of ontology, in which nature and culture are not construed as isolated spheres devoid of reciprocal contact or mutual influence. In this way, it becomes possible to hazard guesses at essential aspects of the identities of these groups.

The Ontological Turn and Descola’s Frameworks

Within the framework of the ontological turn emerging from Lévi-Strauss’s late structuralism1, a new anthropological perspective developed in the late 1990s and early twenty-first century: the so-called “ontological turn” (Latour 1993; Viveiros de Castro 2001; Descola 2012). This approach challenges conventional assumptions about what constitutes reality, offering a critical reassessment of traditional ethnography and its ethnocentric premises. It emphasizes a holistic understanding of cultures and, importantly, interrogates the presumed distinction between nature and culture from the perspective of the societies under study, rather than imposing Western conceptual frameworks (Palecek 2022; Sahlins 2014; Descola 2014).

In Par-delà nature et culture, Descola (2012), drawing on ethnological studies of Amazonian societies, reconceptualized the relationship between nature and culture, introducing a new ontological framework. His research demonstrates that the boundary between these spheres is not universal but constitutes a deeply Western construct. Across diverse temporal and geographic contexts, most societies do not perceive nature and culture as separate. Instead, there is a widespread pattern of treating the environment as populated by persons endowed with human-like attributes. This perspective, he argues, is not ecologically determined, as it appears in both Amazonian and Arctic societies; the separation of nature and culture is, in essence, a cultural product.

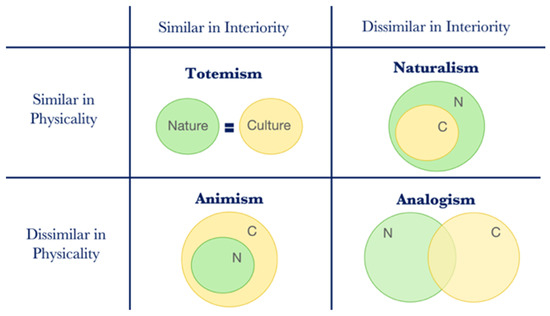

From this premise, Descola proposes a structure of relationships between humans and the world, centered on two key dimensions: identification and relation. Identification, in particular, generates two phenomena that shape the interaction between nature and culture (Figure 1):

Figure 1.

Ontological models proposed by Descola (Diagram ©Antonio Muñoz Herrera).

- Interiority, referring to beings’ internal qualities, including intentionality, subjectivity, and reflexivity.

- Physicality, encompassing not only corporeal traits but also the ways entities act in the world—their visible and tangible expressions.

From these binary distinctions emerge four ontological structures, which in turn shape cosmologies, social models, and identity theories: Animism, Totemism, Naturalism, and Analogism. Of these, the first two are most relevant to this study:

- Animism: Non-humans are attributed an interiority identical to that of humans, extending the domain of “culture” beyond the human sphere. Distinctions between humans and non-humans are primarily matters of form and mode of existence—that is, physicality.

- Totemism: Differences among species in the natural world provide a model for conceptualizing human social divisions. Continuity between physicality and interiority exists because the totem is not an individual entity with which humans interact, but rather a living embodiment of shared material and essential qualities. Both totem and human are contingent manifestations of an underlying, immutable structure.

It is important to emphasize that these four ontologies do not constitute dominant cultural models or a locally prevailing habitus; rather, they function as frameworks for integrating experience, selectively shaping perception and the relationships individuals maintain with others. Consequently, they are not mutually exclusive: all four coexist in potentiality within every human being. According to Descola, historical contingencies determine which ontology assumes prominence in a given culture. In this sense, sociological realities are ultimately subordinated to underlying ontological realities.

In this respect, both in the Egyptian case (Muñoz Herrera 2024a, 2025b, 2025c) and in that of the Levant (Verhoeven 2025; Clare 2024), a form of totemic ontological structure has recently been proposed, grounded in such aspects as the relationship to landscape, the iconography identified on reliefs and objects, and the deployment of communal sanctuaries such as that of Göbekli Tepe. In both regions—the Nile Valley and the Fertile Crescent—the final phase of sedentarization appears to register a transformation in ritual, symbolic, and funerary practices (Muñoz Herrera 2025c). What the archaeological record seems to suggest, therefore, are the last vestiges of certain cultural dynamics whose roots extend back into the Palaeolithic, allowing us not only to interpret the identities of these groups but also to project them backwards in chronological terms.

Among these cultural dynamics, the treatment of the bodies of certain deceased individuals is of particular significance, insofar as it lends support to interpretations concerning the identities of these groups. Practices such as post mortem dismemberment, the modification and subsequent ritual use of the cranium, and the secondary burial of skulls in places other than those where the remainder of the body was interred, may well indicate cultural strategies specific to groups whose identities were conceived in terms of reciprocity with the mutable natural environment in which they lived. Such practices would also have served to reinforce particular individual and collective aspects of their identity and cultural memory.

In order to reach firmer conclusions on this matter, we shall proceed to analyze the dynamics of body treatment in both the Levant and Egypt during the late pre-Neolithic phase, to examine their parallels, and to consider what form of identity structure may be inferred for those groups associated with such practices, drawing upon the anthropological theoretical models outlined above.

2. Body Treatment in Neolithic Levant

Post mortem bodily manipulation is a cultural phenomenon whose origins in the Levant may be traced back to the Natufian period (ca. 9500 BC), as attested at Hayonim Cave, and to Nativ Hagdud in the PPNA phase of the Jordan Valley (Haddow and Knüsel 2017, p. 53). In other words, the phenomenon appears to have originated in the southern Fertile Crescent, from where it may have spread northwards into the Upper Euphrates and Anatolia during the Epipalaeolithic2.

However, throughout the immediately subsequent period—the late PPNA and PPNB—when this practice reached its peak, the phenomenon continued to be documented in only a very small proportion of the population. Around 3% of bodies present evidence of some form of manipulation (Haddow and Knüsel 2017; Bonogofsky 2005), primarily the absence or modification of the skull. This distribution suggests a funerary ritual practice applied selectively to particular individuals, the reasons for which we shall attempt to disentangle below. Moreover, there is no possibility of identifying patterns based on sex or age among those individuals subjected to manipulation, since the available evidence indicates a balanced representation in this regard. The burials, generally situated beneath houses or within abandoned urban areas, display considerable heterogeneity in typology, with only this small percentage presenting signs of manipulation. Nevertheless, the archaeological contexts of these interments, together with the information derived from the remains themselves, may aid us in interpreting this funerary dynamic.

2.1. Defleshing

Among all the processes directed at the manipulation of the corpse, the one of greatest relevance to the present investigation is the post mortem extraction of the skull from the remainder of the body. Interred bodies lacking skulls exhibit signs of non-anthropic defleshing (Bonogofsky 2005, p. 124). In this respect, Mellaart (1967) already suggested the possibility that corpses were publicly exposed on platforms for defleshing by vultures. Although this theory fell into disfavor in subsequent decades owing to the lack of concrete supporting evidence, recent taphonomic studies seem to confirm Mellaart’s proposal (Pilloud et al. 2016)3.

The natural skeletonization of a body exposed to open air generally occurs within six months, with the cranium being the first part to skeletonize (Croucher 2018, p. 8). This process, however, can be drastically accelerated by animal defleshing. Experimental archaeology has demonstrated that vultures arrive within one to two days after deposition of a body, stripping it and leaving marks on approximately 22% of the bones while tendons and ligaments remain intact; a complete human body can be defleshed within around five hours. In such a case, a body might be skeletonized within one to three days following the arrival of the vultures. Taphonomic analysis carried out on the 18 decapitated bodies and 29 isolated skulls recovered at Çatalhöyük pointed to vulture-induced defleshing, without anthropic intervention or that of any other animal—in other words, a process undertaken within a relatively controlled setting organized by the community (Pilloud et al. 2016).

This ritual of defleshing and skeletonization through animal intervention, conducted within a controlled ritual environment, may also find its reflection in reliefs and statuary depicting animals and humans in which rib cages or particular parts of the body are rendered in evidently skeletonized form, as attested at Göbekli Tepe4, WF165, Karahan Tepe (See Mithen et al. 2023, p. 839), and Çatalhöyük6 (Meskell 2008).

2.2. Skulls

However, the part of the body that receives the most attention—both in the case of individuals whose remains were manipulated and in relief and three-dimensional iconography—is the head.

The process appears to have been relatively standardized across the Fertile Crescent and, although preserved to varying degrees, the cranium seems generally to have undergone the following sequence: it was initially removed from a primary burial of the complete body, usually beneath a house; it was plastered; exhibited publicly; transported and employed in rituals for a period of time; and finally buried secondarily together with other similar skulls in a new location, often serving as a foundation deposit for a new house or for the re-consecration of an abandoned urban area. These practices originated at least from the beginning of the PPNA (9500 BC) in the southern Levant and spread into the Upper Euphrates and Anatolia during the PPNB (Croucher 2018, p. 3)7. To date, some ninety plastered skulls have been excavated at different sites, offering a substantial corpus through which to understand this cultural dynamic.

Primary interment of the complete body, usually beneath the house, tended to occur within a few days of death—generally less than a week (Santana et al. 2015, p. 2). The body could be buried either already defleshed and skeletonized following its prior public exposure, as noted above, or in a preserved state for its natural decomposition underground. Burial locations were often marked by a plastered surface over the grave, and in some cases, as at ‘Ain Ghazal, the location of the skull beneath the floor was indicated by a red dot painted on the white plaster, facilitating later retrieval (Kuijt 2008, p. 176).

After some time—difficult to specify with precision—the grave was reopened and the skull was removed for reuse in public and communal ceremonies. In most cases, the skull was plastered in order to restore the facial features of the deceased, though not in a portrait-like manner but rather symbolically. The plaster was applied directly onto the defleshed cranium, reconstructing the facial features and, in some instances, reproducing the mandible, which was typically left behind in the primary burial (Goren et al. 2001). Paint, generally ochre or pinkish tones, was then applied in a schematic fashion, although in some cases—such as certain Jericho skulls—moustaches or scarification marks were painted onto the surface (Kurth and Röhrer-Ertl 1981, p. 436). The typological variety is heterogeneous and, while their symbolic function was likely the same, different local techniques and preferences are evident. Thus, at Jericho, the mandible was preserved in almost 50% of cases, the eyes were opened through the insertion of shells, and some degree of cranial deformation was evident; at Tell Aswad, by contrast, the eyes were depicted closed and plastered, the ears were reconstructed, and the mandible retained; while at ‘Ain Ghazal, mandibles and ears were typically absent, with eyes depicted either open or closed (Kuijt 2008, p. 180).

Following plastering, skulls appear to have been displayed publicly, transported to different locations, and employed as reference points in rituals and public ceremonies over extended periods. It is significant that many skulls were repaired, replastered, or repainted on several occasions during their use-life, underscoring both their long-term employment by these communities and the evidence of repeated episodes of use and maintenance8. Examples of such practices have been identified at ‘Ain Ghazal, Kfar HaHoresh, Çatalhöyük, and Tell Aswad, including a case where the nose of a skull was repaired (Croucher 2018, p. 8).

At some indeterminate moment—probably after years of ritual circulation—the skull was finally decommissioned and buried in a new location. In general, skulls have been found in collective caches beneath house floors or courtyards, suggesting joint actions involving multiple kin groups and perhaps the creation of communal caches intended to re-sacralize previously inhabited spaces (Croucher 2018, p. 8). There are, however, notable exceptions: at Tell Aswad, skulls marked the location of a necropolis; at Kfar HaHoresh they were found in burial areas alongside a wide range of animal bones (Horwitz and Goring-Morris 2004); and at Çatalhöyük a striking example was recovered within the burial of an adult woman, deposited in fetal position and holding a skull clasped to her chest (Hodder and Meskell 2011).

In any case, the emphasis on the face and human head emerges as a consistent feature of PPN cultural dynamics throughout the Fertile Crescent. The human head seems to have been conceived as a locus of a particular vitality that persisted among the living after the death of the individual (Ibáñez et al. 2014, p. 91). This would explain not only the practice of plastered skulls described above but also the remarkable proliferation of human facial iconography in all its typological variants during this period.

Until this time, iconography had been predominantly animal in character, but from the end of the PPNA and the beginning of the PPNB (8200 BC), the human face emerges as a principal iconographic motif (Ibáñez et al. 2014, p. 82). Among the more striking examples are figurines from Çatalhöyük with cavities on the crown to allow for interchangeable heads, suggesting acts of combination linked to social factors such as gender or kinship, and, in any case, enabling the transmutation of identity through the exchange of heads—emulating funerary practices in symbolic form (Meskell 2008, pp. 379–83). The fixation on the face is also visible, for example, in the wooden staff from Tell Qarassa North carved with at least two human faces in relief, probably in a funerary ritual context (Ibáñez et al. 2014, p. 83); in the disproportionate size and detail of the heads on the statues of ‘Ain Ghazal compared to their crudely modelled bodies; in the carved stones bearing human faces from WF16, Jerf el Ahmar, and Nahal Ein Gev II (Mithen et al. 2023); in the ceramic vessel shaped as a hybrid human–bovid face from area 4040 at Çatalhöyük (Hodder and Meskell 2011); and in the celebrated masks of the southern Levant found at Nahal Hemar, Horvat Duma, and the southern Judean mountains.

All these expressions attest to a particular preoccupation with the human face, which—as will become clearer below—appears to have been employed as a means of configuring and transmuting both individual and collective identities within societies undergoing profound transformation, adapting to increasingly sedentary rhythms, and facing episodes of population aggregation and growth. Let us now turn to the Egyptian case, where comparable practices and cultural dynamics can be identified, providing parallels that will later assist us in interpreting the phenomenon.

3. Body Treatment in Early Holocene Egypt

It is noteworthy that, from at least Naqada IC (ca. 3550 BC), two distinct and seemingly opposing models of body treatment in funerary rituals emerge. This period appears to represent an experimental phase, possibly reflecting either two separate cultural traditions or two developmental stages within a shifting ontological framework. At a time when the selection of grave goods and the arrangement and treatment of the body had not yet been standardized, these models may indicate a creative process in which individual identity was actively being shaped (Wengrow and Baines 2004).

The practice of dismembering specific body parts was first documented by Petrie during excavations at the Naqada and Ballas cemeteries (Petrie and Quibell 1896). Initially, the absence or deliberate displacement of skeletal remains was interpreted as the result of tomb robbery, looting, or post-depositional ground movements. However, parallels in other necropolises—such as Naga el-Deir (Girardi 2017), Adaima (Buchez 2011), Umm el-Qaab (Amélineau 1899), and Gerzeh (Tamorri 2017, p. 450)—later demonstrated that this constituted a deliberate and relatively widespread funerary practice from at least Naqada II (ca. 3500 BC). Statistical analyses indicate that at least 3.4% of bodies from this period display signs of manipulation9, comparable to patterns observed in the Levant, with 23% exhibiting disarticulation and displacement of bones—mainly skulls and long bones—either within the same tomb or to external locations (Tamorri 2017)10.

The typological treatment of these burials is diverse and complex, lacking a clear standardized pattern. For instance, in tomb A96 at Adaima, the body appears to have been dismembered prior to burial, with long bones carefully aligned alongside flint knives and diorite maceheads11. At Naqada, some skulls were replaced with pottery vessels12, while others were repositioned atop adobe piles or placed adjacent to the body13. In tomb U1 at Cemetery U of Umm el-Qaab (Abydos), bones were arranged in a rectangular formation, suggesting their original placement in a basket or organic container that subsequently decomposed (Peet 1914, p. 14). A similar configuration occurs in tomb N7244 at Naga el-Deir, where an adult and a six-year-old child were stacked, with the adult’s skull atop the smaller mound (Girardi 2017, pp. 296–307), and comparable arrangements are found in tomb S162 at Adaima (Buchez 2011).

Among these examples, tomb N7522 at Naga el-Deir is particularly notable. Dated to Naqada IID, this burial consisted of a wooden box placed within a rectangular pit, containing four skulls and two mandibles—all from adults removed from earlier burials—without other skeletal remains. A substantial quantity of ceramic grave goods accompanied the deposit (Girardi 2017, pp. 304–6). Similar “skull deposits” appear in other cemeteries, such as tomb T.5 at Naqada, where six skulls (five centrally located, one to the south) were interred alongside additional bones and rich ceramic and stone grave goods (Petrie and Quibell 1896), contrasting with numerous tombs in which the skull was entirely absent14.

This practice not only altered the body of the deceased, allowing it to decompose in the open air before further manipulation, but also involved the intentional displacement of selected remains—primarily skulls—to secondary burials, which appear to have held greater significance, as evidenced by associated grave goods. The process possessed both temporal and spatial dimensions: temporally, the investment of time in modifying the body extended the deceased’s social influence beyond death (Wengrow and Baines 2004, p. 1103); spatially, it enabled the strategic distribution of body parts across multiple graves or cemeteries, sacralizing new spaces by linking them to revered ancestors or mythical forebears.

Concurrently, a conceptually and practically contrasting funerary tradition emerged, ultimately becoming the dominant method in Egyptian civilization. Early evidence of mummification appears at the HK43 cemetery in Hierakonpolis (Friedman 2008), dating to Naqada IIB-C (3650–3500 BCE)15. Here, resins and woven mats were deliberately used to protect and preserve specific body parts, such as hands, elbows, or cervical vertebrae. Notably, tomb 85 contained a cervical vertebra with cut marks, suggesting decapitation, despite no clear evidence of broader dismemberment; the poor preservation of the record limits further interpretation.

By Naqada III, mummification had become the principal funerary practice, fully supplanting techniques involving dismemberment and skeletal displacement. Funerary complexes expanded and were increasingly constructed with mudbrick, grave assemblages became richer and more hierarchical, and both body treatment and grave goods became standardized, reducing earlier variability (Wengrow 2006)16.

This shift in funerary practice coincides with broader cultural transformations in Egyptian society, likely linked to changes in ontological structures and evolving environmental conditions, which by 3500 BCE were already significantly influencing the trajectory of Egyptian civilization (Muñoz Herrera 2025c).

Previous Cases: Nabta Playa

However, practices of dismemberment may precede what is currently visible in the archaeological record. As has been argued elsewhere (Muñoz Herrera 2025c), such practices appear to be associated with highly mobile groups of the early Holocene in Egypt, whose material traces only become archaeologically visible once more stable settlement emerges in proximity to the Nile Valley. Despite the scarcity of evidence before the fifth millennium BC, and with a few notable exceptions (e.g., Gatto 2012; Wendorf and Schild 2001; Bunbury et al. 2020; di Lernia 2006), some indications may point to the existence of such practices at an earlier stage17.

One of the most suggestive cases is Nabta Playa, located on the margins of a paleolake in the Western Desert of Egypt. Archaeological evidence has highlighted the site’s role as a ceremonial meeting place for Saharan groups (Wendorf and Schild 2001). In use between 8000 and 2500 BC, Nabta Playa was initially occupied for some 500 years without interruption, favored by the ecological conditions of the so-called “Green Sahara” (Kuper and Kröpelin 2006). With the onset of desertification, the site developed into a major ceremonial center for cattle-herding groups with seasonal rhythms of aggregation. Once a year, before the summer rains, large groups gathered around the paleolake for communal rituals—likely related to rainfall, fertility, and cattle cults widespread across the Sahara and southern Arabia (Chaix 2011)—in a way reminiscent of the aggregation sites of the Levantine Neolithic, such as Göbekli Tepe (Dietrich and Notroff 2015). The architectural evidence suggests a seasonal rather than permanent occupation: hut floors without associated storage, domestic production or complex habitation structures (Wendorf and Schild 2001).

Beyond the well-known features—the calendar circle, bovine tumuli (some lacking skulls), and megalithic alignments with celestial orientations—the so-called “complex structures” (Wendorf and Schild 2001, p. 503) are of particular relevance here. These consist of large stone tumuli covering subterranean chambers cut into the desert bedrock, up to 3–4 m deep and accessed by steps. Within the chambers, a central plinth was carved directly into the bedrock. Of the ca. 30 structures recorded, only two were excavated. Structure A, the largest, was covered by a tumulus of 71 sandstone and limestone blocks, leading into a shaft filled with clean sand. Inside, excavators found a massive sandstone sculpture (1.9 × 1.5 × 0.7 m), interpreted as either a bovine or a bird, alongside knapping debris (Wendorf and Schild 2001, p. 505). The interpretation remains debated, with suggestions ranging from commemorative monuments to elite burials (Wendorf and Schild 2001, p. 503).

Yet further evidence may illuminate their role. Although Nabta Playa was clearly not a cemetery—only three small groups of human burials have been identified over four millennia of use—one tumulus (E97-5), dated to c. 5500 BC and contemporaneous with the “complex structures”, contained a flexed and articulated skeleton deliberately deprived of its skull. The size of the tumulus, one of the largest at the site, suggests considerable communal investment, highlighting the status of the interred individual (Wendorf and Schild 2001, pp. 477–79). This case seems to represent clear evidence of intentional manipulation of the body, with the skull removed for separate deposition, at least by the mid-sixth millennium BC in Holocene Saharan societies.

Given the structural resemblance between these tumuli and those of the later Kerma culture in Nubia—both featuring a central plinth on which the body of the deceased was placed (Ambridge 2007; Honegger 2018; Kendall 1997)—it is possible that these enclosures had a funerary role directly linked to the manipulation of revered clan members’ remains during seasonal gatherings. On the exposed plinth, the deceased may have been left to desiccate and decompose, consumed by scavengers such as vultures and jackals—animals that would later hold a central position in Egyptian funerary symbolism. The remains may then have been gathered and reburied in a secondary context, thereby sacralizing the burial ground for the whole community18.

In this respect, the practices documented in the Levantine Fertile Crescent and in the Western and Eastern deserts of the Nile Valley reveal striking parallels in form, practice and symbolism. These shared dynamics provide a productive framework for exploring how such ritual treatments of the body contributed decisively to the construction of both individual and collective identities in early Holocene societies.

4. Identity Construction

Debates regarding the interpretation of body manipulation during the Pre-Pottery Neolithic (PPN) have been extensive in the Levant but almost entirely absent in Egyptology, where research has tended to remain archaeological and quantitative in scope (Tamorri 2017; Girardi 2017; Jones et al. 2014; Hassan 2004), with only limited attempts at wider cultural interpretation embedded within broader discussions of the period (Wengrow 2006; Wengrow and Baines 2004). It is therefore worth revisiting the Levantine evidence before introducing our own perspective, since these cases provide a useful comparative framework.

The discovery of the first plastered skulls initially led to an uncritical assumption that they belonged to adult males, resulting in the classic interpretation of these remains as ancestral patriarchs who received cultic veneration (Bienert 1991; Wright 1988; Cauvin 1994). Subsequent analyses, however, have undermined this model. Only 36% of the skulls can be securely identified as male, and at least 19% belonged to juveniles (Croucher 2018, p. 9). At Jericho, plastered skulls are disproportionately those of young women and children (Benz 2010, p. 254). Such data substantially weaken the notion of the venerated male elder (Bonogofsky 2003).

An alternative interpretation links the skulls to the selective commemoration of ritual leaders, their rarity reinforcing this idea (Rollefson 2000, p. 184). However, this hypothesis is challenged by the presence of children, and by evidence of cranial modification undertaken during infancy (Croucher 2018, p. 10). Could individuals have been identified from birth as future ritual figures or clan totems? While intriguing, the evidence is insufficient to sustain this claim. Other approaches emphasize the communal dimension, suggesting that the plastered skulls acted as vehicles through which personal identity was deliberately effaced, subsumed into a more diffuse and mythic ancestral presence (Kuijt 2008, p. 174). Rather than representing a specific ancestor, such skulls may have functioned as group totems, embodying lineage ties that extended far beyond immediate genealogical memory.

More violent interpretations have also been proposed, with some scholars suggesting that the skulls reflect episodes of intergroup conflict and the preservation of “trophies”, paralleling ethnographic examples of headhunting in Indonesia (Adams 2005; Testart 2008). Yet the absence of trauma in most cases renders such explanations unlikely (Hodder 2009; Özdogan 2009; Belfer-Cohen and Goring-Morris 2009), with the partial exception of Tell Qarassa North (Santana et al. 2012).

What is clear is that the individuals selected for such treatment were chosen deliberately by their communities—possibly even identified in prenatal or early life stages—and that their deaths marked moments of heightened collective engagement. Through their transformation, the corpse became a legitimizing medium of communal identity. Ethnographic parallels provide an illuminating comparative perspective. Among the Asabano of Papua New Guinea, the bodies of respected members are publicly exposed on elevated platforms until decomposition. The bones are then curated with distinctions based on gender, age and social role: the bones of skilled older men are interred in sacred houses; women renowned for pig-rearing have their skulls and clavicles separated, placed in bags, and deposited in communal houses; while children, youths and non-specialist women are discarded (Lohmann 2005).

Against this background, it becomes crucial to explore how and why such processes emerged in the Mediterranean Levant and in Egypt, and what forms of identity they materialized. The dynamics can be usefully understood as a sequence of four main stages through which the body of the selected individual—and ultimately their skull—was transformed after death.

4.1. Body Treatment: Identity Construction in Four Phases

4.1.1. Public Exposure

The first stage, likely occurring within the first week after death, appears to have centered on the public display of the body in places of marked symbolic significance to the community. Such controlled settings enabled natural decomposition, including defleshing by scavengers—above all vultures, whose prominence in both Egyptian and Levantine ritual iconography is striking. This process may provide a plausible explanation for the so-called “complex structures” at Nabta Playa, while in the Levant comparable practices could have been accommodated in communal sanctuaries such as Göbekli Tepe, WF 16, Tell Qarassa North, Jerf el Ahmar or Tell ‘Abr 3, all of which have yielded evidence of decapitated and modified skulls (Verhoeven 2025, p. 6).

Archaeological and iconographic studies of these sites have variously interpreted the communities involved as structured by animist ontologies (Yakar 2005; Benz and Bauer 2015, 2022)19, as shamanic (Schmidt 2000, 2006; Dietrich 2024), charismatic (Clare 2024)20, immanentist (Verhoeven 2025) or relational (Busacca 2017). Here, however, I suggest that these groups are more fruitfully understood within a totemic ontological framework, following Descola (2012). In this perspective, physicality and interiority are held in continuity between society and nature, making the exposure of corpses and their consumption by scavenging birds legible as reciprocal acts embedded within the ontological order.

Both in the Fertile Crescent (Clare 2024, p. 3; Verhoeven 2025, p. 4) and across the western and eastern Sahara into the Nile Valley (Kuper and Kröpelin 2006), these groups practiced highly mobile subsistence strategies, moving seasonally in pursuit of hunting, gathering and foraging opportunities. Such mobility, coupled with the absence of full sedentism, required highly developed ecological knowledge. In turn, this structured what may be described as a sensory ecology—a mode of experience in which social life and environmental processes were interwoven through reciprocity (Muñoz Herrera 2024b). It is in this light that the absence of animal sacrifice among hunter-gatherer communities becomes intelligible (Clare 2024, p. 22): animals and environments were not construed as subordinate, but as relational equals whose lives and deaths required negotiated forms of exchange21.

Ethnographic evidence strongly corroborates this pattern. Communities reliant on the harvesting of wild resources tend to articulate reciprocal relations with their environments (Brightman et al. 2012; Naveh and Bird-David 2014; Salmon 2000). From this perspective, the exposure of the corpse to vultures was not a denial of personhood but an affirmation of it: the return of a socially significant individual to the natural world, closing the cycle of reciprocity22. Within a totemic ontology, such rituals ensured continuity of physical and interior substance between humans and the non-human world. By offering the flesh of their deceased notables to scavengers, these societies enacted an exchange that reaffirmed their survival strategies—taking from the environment through hunting and gathering and returning to it through the ritualized dissolution of the human body.

4.1.2. Primary Burial

The second stage of the mortuary sequence was the primary burial, most commonly within domestic contexts in the Levant and in areas of heightened symbolic resonance in the Nile Valley. This stage appears to have been directed towards anchoring the deceased within a clearly defined sphere of kinship, while simultaneously asserting their individuality (Meskell 2003; Hodder and Meskell 2011). In the better-documented cemeteries of early Holocene Egypt, the pattern is strikingly evident: burials cluster in ways that suggest enduring clan-based structures, with evidence of grave reuse across generations. Notable examples include Gebel Ramlah (Czekaj-Zastawny and Kabaciński 2015; Kobusiewicz et al. 2009), Naqada (Campagno 2003), and Cemetery U at Abydos (Hartung 2018).

Through such practices, group identity was materially consolidated. The grouping of burials within houses or symbolically charged locales not only created long lines of descent but also materialized social memory. That these societies were structured along clan-based lines appears strongly suggested not only by the funerary evidence in Egypt but also by the iconography and spatial organization of Levantine sanctuaries. The patterned association of particular animal species with specific buildings at Göbekli Tepe23 (Verhoeven 2025, p. 11) or the conspicuous absence of the main prey animals (gazelle, wild ass) in the imagery of these structures (Clare 2024, p. 16) point to a system in which buildings embodied the domains of distinct animal-linked clans: boar, fox, snake, and so forth24.

These associations evoke a totemic framework of identity, in which kinship groups were tied to particular animal species through relations of continuity in both physicality and interiority. Within such a structure, periodic congregations of dispersed groups—likely timed to seasonal cycles of abundance—would have allowed for collective rituals and festivals that reinforced both inter-clan relations and broader social cohesion (Dietrich 2024).

In this context, primary burial emerges as a crucial mediator between the individual and the collective. On one hand, the burial contextualized the deceased within intimate genealogies of household and lineage; on the other, it inscribed them within the larger symbolic order of clan and totem. This interplay of memory and identity, individual and group, was then further elaborated in the subsequent stages of the mortuary sequence.

4.1.3. Secondary Use of the Skull

The removal and subsequent plastering of skulls for use in public rituals or communal ceremonies marks a further step in the elaboration of identity within these groups. In the Egyptian record, direct evidence for such practices is scarce; here, secondary deposits in caches remain the primary indication. In the Levant, however, the archaeological record allows a deeper interpretation of the role and significance of skulls in the construction of social and symbolic identities.

Beyond regional variations in typology and technique, plastered skulls functioned as material anchors of social interaction and remembrance. Initially embodying the individual memory of the deceased, their ritual reuse progressively dissolved this individuality into a broader cultural memory, crystallized in the form of a clan or totemic ancestor (Kuijt 2008, p. 172). The re-plastering of skulls across multiple generations points to a transformation in the nature of remembrance: from personal and experiential to abstract and referential (Kuijt 2008, p. 174). Whereas primary burial created a fixed locus of individual memory, the ritual circulation of skulls extended remembrance into the public, collective sphere—anchored in ceremonies of high visibility and reinforced by the capacity of skulls to move across spatial and social domains.

This mobility was particularly significant in the context of highly mobile societies with seasonal settlement rhythms. The transportability of skulls allowed ancestors to accompany groups across shifting landscapes, establishing portable centers of cult wherever the group resided. In this sense, the dissolution of individual identity was precisely what enabled the construction of a durable, transgenerational communal identity. By erasing the specificity of the original subject, the skull became a medium through which clan memory was perpetually renewed, ensuring continuity between past, present, and future25.

The totemic dimension of this practice is underscored by parallels with the treatment of certain animals, especially bovids. Both human and animal skulls were subject to analogous manipulations—special deposition, plastering, and subsequent reburial—suggesting that heads themselves, rather than whole bodies, functioned as privileged vehicles of memory and identity. At Çatalhöyük, for instance, human skulls and bucrania were plastered, displayed, and reburied, sometimes together within communal contexts (Hodder and Meskell 2011, p. 245). Comparable practices have been documented at Tell ‘Abr 3, where bucrania were found in association with human deposits (Yartah 2005), and at Jerf el Ahmar, where four suspended bovine skulls were embedded within a building’s walls (Hodder and Meskell 2011, p. 242)26. The symbolic equivalence of human and bovine crania is further echoed in the Nile Valley, where cattle cults emerge at an early stage (Brass 2003), with bucrania appearing in human graves even into the Old Kingdom (Dijk-Coombes 2013), and reaching massive scale in the Kerma culture of Nubia (Chaix 2011)27.

4.1.4. Secondary Burial

The final stage in this mortuary cycle is represented by the secondary burial of skulls in collective caches—such as those documented at Tell Aswad in the Levant or Tomb T.5 at Naqada in Egypt. Stratigraphic evidence suggests that these deposits were simultaneous rather than accumulative, pointing to collective acts of closure.

In the Levant, the placement of caches in abandoned urban areas suggests an intent to create foundation-like deposits: sacred wells of memory anchoring future reoccupation by members of the clan to whom the skulls belonged. In Egypt, by contrast, secondary burials were integrated into established necropolises. Here, the collective tomb created through the reburial of skulls acted as a new axis of funerary activity, structuring subsequent mortuary practices around a shared point of reference (Muñoz Herrera 2025a; 2025c).

At this stage, the individual memory embodied in the skull had long since dissipated. What remained was the ancestralized identity of the clan as a whole, materially enshrined in a collective deposit that simultaneously legitimized territorial claims and sacralized new spaces. The cache thus functioned not only as a mortuary deposit but as a totemic anchor: a ritualized concentration of ancestral potency capable of underwriting new foundations and reaffirming the continuity of the group across shifting landscapes and generations.

5. Conclusions

Based on the archaeological evidence presented and interpreted through the theoretical lens afforded by the anthropological “ontological turn,” we may tentatively assert that these groups were associated with transitional totemic identities, shaped by the sedentarization prompted by environmental change28. Both in the Levant and the Egyptian Sahara, these groups organized their lives according to cyclical seasonal settlement patterns, their survival dependent upon detailed knowledge of their environment. Ethnographic evidence demonstrates that such groups maintain reciprocal relationships with the natural world on which they depend, generating shared bonds that enable continuity between the physicality and interiority of the group and their surroundings. Practices such as exposure to scavengers, controlled hunting, and engagement with the landscape can thus be interpreted as expressions of a totemic identity grounded in reciprocity with nature.

Furthermore, iconographic evidence from large communal ceremonial centers, such as Göbekli Tepe and Nabta Playa, alongside the ritual use of plastered skulls—both during secondary circulation and final deposition—and the distribution of graves within cemeteries, whether inside houses or in open spaces, support the interpretation of these groups as clan-based, composed of small to medium units that convened annually at major ceremonial centers to mark the arrival of periods of abundance. Within these centers, each clan appears to have venerated its associated totemic animal, while plastered skulls functioned as central symbols of the mythical clan ancestor29. Recent genetic studies at Çatalhöyük (Yüncü et al. 2024) indicate that such clan-based societies may have been matrilineal and matrilocal, though comparable analyses across other sites are required to establish a more comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon.

Previous research (Muñoz Herrera 2025c) has suggested that the final sedentarization in the Nile Valley triggered profound ontological and social transformations within these groups, marking a shift from totemism to animism and from clan-based to “house” societies. For detailed discussion of the mechanisms and causes, the reader is referred to that study. Here, it is sufficient to note that the disappearance of plastered skulls in the Levantine Mediterranean may reflect a similar cultural dynamic, with the archaeological record capturing the final vestiges of funerary practices on the verge of obsolescence following sedentary settlement. Clare (2024) similarly suggests that critical religious transformations occurred during this period, reflecting a shift from totemism to analogism in the context of sedentarization.

Based on the interpretation presented above, this transition represents a movement from totemism to animism, driven by abrupt ecological changes that disrupted the continuity of physical and interior relations with the environment. Totemism presupposed such continuity, whereas animism reflects continuity of interiority amid physical discontinuity, imposed by heterogeneous landscapes resulting from climatic shifts, fundamentally reshaping identity.

While future research will undoubtedly illuminate the phenomenon further, the present study demonstrates how funerary evidence can be interpreted through novel theoretical frameworks. It also illustrates how totemic, clan-based societies employed complex mortuary rituals, including selective manipulation of individuals, to reinforce and enact the ontological foundations of their social and symbolic identities.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

I thank Teresa Aizpún Bobadilla for the kind invitation to participate in this special issue. I am also grateful to Inmaculada Vivas Sainz for their useful comments on the initial draft, which significantly improved this paper. Finally, I thank the reviewers for their support and feedback, which contributed to improvement and publication of this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Lévi-Strauss’ naturalistic turn occurred during the 1980s, when he moved away from linguistics as the leading science and replaced it with biology. Structure was no longer a method, but rather something that resided in nature itself, transcending the nature/culture dualism that had characterized all his previous work. Embracing cognitive advancements, Lévi-Strauss promoted an ontological structuralism to uncover deep laws of nature from a radical materialism in which cultural foundations are found in physical-chemical substrates (Dosse 2012). |

| 2 | In Anatolia, the earliest evidence for this period is recorded at the site of Pinarbaçi (Haddow and Knüsel 2017). |

| 3 | Since the Upper Paleolithic, birds have represented a marginal iconographic motif within these groups’ visual culture. However, during the PPNA (9800–8700 BC), bird representations appear significantly (Garfinkel and Krulwich 2023), particularly vultures, suggesting a cultural dynamic in which the vulture held special importance. This may be linked to the funerary defleshing of certain individuals, as indicated by the taphonomic evidence presented here and reflected in painted iconography within some houses at Çatalhöyük (Mellaart 1967, p. 83), the reliefs on pillar D43 at Göbekli Tepe (Dietrich and Notroff 2015; Busacca 2017; Banning 2023), seals from Tell Brak (McMahon 2016), and depictions on plaques and ceramics at Jerf el Ahmar and Körtik Tepe (Garfinkel and Krulwich 2023). Some authors (Garfinkel and Krulwich 2023) also suggest that these motifs may echo a past practice during a transitional period, reflecting the mobility of hunter-gatherer groups and the relationship between birds, annual migration, and the seasonal movements of these communities. |

| 4 | Sculptures D-DAI-IST-GT1996-DJ-A14 0051 and D-DAI-IST-GT2008-DJ-A61 0004. |

| 5 | SF1365. |

| 6 | 12041.X7. |

| 7 | It is worth noting that this dynamic is neither unique to nor characteristic of the Mediterranean Levant; similar cases can also be found in Greece, including Prodromos, Platia Magoula Zarkou, Alepotrypa Cave, and Tharrounia (Euboea) (Talalay 2004). Instances of regrouping bones from different individuals to form a single skeleton, incorporating elements from various chronological phases, have also been documented, such as in tomb 26 at Pommeroeul (Belgium) (Veselka et al. 2024). |

| 8 | The opposite scenario is also documented. At Tell Qarassa North (9th millennium BC), twelve skulls were found buried in two groups, ten or eleven of which had been deliberately mutilated on the face. This has been interpreted as an episode of violence used as a social cohesion mechanism, venerating ancestors in response to rapid population growth in the area (Santana et al. 2012). Comparable episodes of violence have also been observed in Egypt, in the urban context of Hierakonpolis, apparently occurring under similar dynamics (Muñoz Herrera 2025c). |

| 9 | In the analyzed sample, no patterns were inferred based on sex or correlation with the quality of the grave goods, although there were patterns based on age: the practice is performed on adults or adolescents. This could suggest that this practice cannot be associated with elements of distinction, marginalization, or rank. In any case, the sample seems to be neither large enough in number nor diverse enough in spatial variety to draw definitive conclusions in this regard. |

| 10 | In this regard, it is worth noting that the evidence from the archaeological record suggests prior desiccation and decomposition of the body before it was dismembered. This dynamic has parallels in cultures of the Near East in these same chronologies and even earlier (Richardson 2007; Soficaru et al. 2009; Ye et al. 2024). |

| 11 | It is important to note here the significance of minerals and mining activities in the initial sacralization of spaces throughout this period (Muñoz Herrera 2025a). Minerals are direct manifestations of divinity and, therefore, have a highly sacred connotation, beyond their functionality (Bloxam 2020; Graves-Brown 2006). |

| 12 | Tombs 37, 227, 845 (Petrie and Quibell 1896). |

| 13 | Tombs 18, 29 y 38 (for the pottery substitution) y 530, 1105 y 315 (for the skull next to the body) (Petrie and Quibell 1896). |

| 14 | As evidenced at Naga el-Deir: N 7110, 7391, 7388, 7516 o 7403 (Girardi 2017). |

| 15 | At Mostagedda, linen wrappings have been identified, dated between 4500-3350 BCE, with a resin composition in proportions and mixtures similar to those used for mummification during the Pharaonic period (Jones et al. 2014). The absence of parallels and the dating range prevent us from knowing if this could be the first record of mummification, but in any case, it is worth mentioning the possibility that the process may have originated centuries earlier or even developed entirely parallel to dismemberment. |

| 16 | It is worth noting that although mummification became the predominant funerary method for body treatment during the Old Kingdom, the plastering of the skull—and even of other parts of the body—persisted, as evidenced at sites such as Saqqara and Deir el-Bersha (Kowalska et al. 2009). |

| 17 | Most burials from earlier chronologies exhibit a fairly homogeneous typology: a shallow oval pit, the complete body placed in a fetal position on the left side, sometimes wrapped in a vegetal mat, and accompanied by a few grave goods of varying complexity (Wengrow et al. 2014). However, the overall record is too limited to assert that body manipulation practices did not occur. If we assume a 3–4% rate of manipulation, as observed in later recorded stages, it would be rare to detect such cases in this dataset given the limited number of excavations. Absence of evidence should not be interpreted as evidence of absence. |

| 18 | In this sense, some of the mounds or ‘sanctuaries’ found in the Libyan desert or in areas of the Jordanian desert (Rowan et al. 2015) could be structures with identical functionality. |

| 19 | In this regard, I believe there is a terminological confusion. All the authors cited here follow the ontological framework proposed by Sahlins (2014), which modifies Descola’s (2012) ontological structures by grouping Descola’s animism, totemism, and analogism as contingent forms of a broader, general animism. This generates theoretical confusion, and although Descola himself argued against this possibility, citing the lack of ethnological evidence to support it (Descola 2014), these authors apply the general label of “animist” to these societies, thereby preventing a clear understanding of which specific type of animism they are referring to, if any in particular. |

| 20 | What follows here, without citation, is, in a way, Dumézil’s trifunctional model. |

| 21 | Once that physical and mental equality between animals and humans is established, it is also worth recalling Descola’s (2012, pp. 25–26) anecdote with the Achuar of the Upper Amazon, illustrating how indiscriminate hunting of species by tribe members can result in physical punishment, as they exceed the boundaries of the supposed pact established with nature. |

| 22 | The production of figurines evidenced at Çatalhöyük also appears aimed at a process of translation, creating hybrid types of beings that combine nature and culture by overlaying animal and human taxonomies (Meskell 2008, p. 374). |

| 23 | Building A was associated with the snake; B with the fox; C with the boar; D with the wild boar, and so on. |

| 24 | This also appears to be evidenced in the Egyptian case through the Predynastic representations of standards topped with animals indicating specific regions, or in the toponyms used on the tags from Tomb U-j at Abydos, the earliest hieroglyphic signs in Egyptian history: the “Mountain of the Elephant,” the “Mountain of the Jackal,” the “Mountain of the Falcon,” and so on (Wegner 2007; Bard 1994). |

| 25 | In a way, it reactivates mythical time and allows the establishment of cycles of activity centered around that sacredness (Eliade 2011, 2016). |

| 26 | See Building 77 at Çatalhöyük or the previously cited ceramic piece 4040, in which bovine and human elements are combined to form a hybrid face directly carved onto the pottery. |

| 27 | In any case, the prominence of cattle cults appears to be a response, in both regions and as supported by the parallels established later (González-Ruibal and Ruiz-Gálvez 2016), to resource scarcity caused by climate change occurring in the Holocene Levant and Sahara (Maher et al. 2011; Clarke et al. 2015). |

| 28 | Although some studies question a correlation between climate change and cultural change (Maher et al. 2011), the coincidence appears clear between the abrupt desiccation of the eastern Sahara during the Early Holocene and the massive arrival of groups in the Nile Valley, driven by resource scarcity and the sedentarization produced in the Levant after the Younger Dryas. Both processes reflect a cultural shift in the archaeological record, which, as we propose here, can be interpreted as the manifestation of a change in the ontological structures of these groups, who had to adapt to new conditions, primarily by restructuring their ontological frameworks for categorizing experience in these new environments. |

| 29 | In Building D of Göbekli Tepe, a round-bodied statue of a wild boar—the primary and emblematic icon of this building—was found, apparently holding a human head between its forelegs. The statue rests on a stone bench within a niche formed by a stele featuring two anthropomorphic figures carved in relief, both missing their heads. The seated figures join their hands at the center, as if holding something, precisely where an artificial hole exists in the stele. Some researchers suggest that within this central hole, atop the boar “totem,” the encrusted skull of the clan may have been placed for ritual purposes (Clare 2024, p. 10). |

References

- Adams, Ron L. 2005. Ethnoarchaeology in Indonesia Illuminating the Ancient Past at Çatalhöyük? American Antiquity 70: 181–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambridge, Lindsay. 2007. Inscribing the Napatan Landscape. Architecture and Royal Identity. In Negotiating the Past in the Past Identity, Memory, and Landscape in Archaeological Research. Edited by Norman Yoffee. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. [Google Scholar]

- Amélineau, Emile. 1899. Les nouvelles fouilles d’Abydos 1895–1897, 1897–8. Angers: E. Leroux. [Google Scholar]

- Applegate, Alex, Achilles Gautier, and Steven Duncan. 2001. The North Tumuli of the Nabta Late Neolithic Ceremonial Complex. In Holocene Settlement of the Egyptian Sahara: Volume 1: The Archaeology of Nabta Playa. Edited by Fred Wendorf and Romuald Schild. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banning, Edward B. 2023. Paradise Found or Common Sense Lost? Göbekli Tepe’s Last Decade as a Pre-Farming Cult Centre. Open Archaeology 9: 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bard, Kathryn A. 1994. The Egyptian Predynastic: A Review of the Evidence. Journal of Field Archaeology 21: 265–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belfer-Cohen, Anna, and Adrian Nigel Goring-Morris. 2009. The Tyranny of the Ethnographic Record, Revisited. Paléorient 35: 106–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benz, Marion. 2010. Beyond Death—The Construction of Social Identities at the Transition from Foraging to Farming. In The Principle of Sharing. Segregation and Construction of Social Identities at the Transition from Foraging to Farming. Edited by Marion Benz. Studies in Early Near Eastern Production, Subsistence, and Environment 14. Lindemberg: Ex Oriente. [Google Scholar]

- Benz, Marion, and Joachim Bauer. 2015. On Scorpions, Birds and Snakes? Evidence for Shamanism in Northern Mesopotamia during the Early Holocene. Journal of Ritual Studies 29: 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Benz, Marion, and Joachim Bauer. 2022. Aligning People: The Social Impact of Early Neolithic Medialities. Neo-Lithics. The Newsletter of Southwest Asian Neolithic Research 21: 7–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bienert, Hans-Dieter. 1991. Skull Cult in the Prehistoric near East. Journal of Prehistoric Religion 5: 9–23. [Google Scholar]

- Bloxam, Elizabeth. 2020. The Mineral World: Studying Landscapes of Procurement. In The Oxford Handbook of Egyptology. Edited by Ian Shaw and Elizabeth Bloxam. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bonogofsky, Michelle. 2003. Neolithic Plastered Skulls and Railroading Epistemologies. Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 331: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonogofsky, Michelle. 2005. A bioarchaeological study of plastered skulls from Anatolia: New discoveries and interpretations. International Journal of Osteoarchaeology 15: 124–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brass, Mike. 2003. Tracing the Origins of the Ancient Egyptian Cattle Cult. In A Delta Man in Yebu. Edited by Aayko Eyma and Chris Bennett. Irvine: Universal-Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Brightman, Marc, Vanessa Elisa Grotti, and Olga Ulturgasheva, eds. 2012. Animism in Rainforest and Tundra: Personhood, Animals, Plants and Things in Contemporary Amazonia and Siberia. New York: Berghahn Books. [Google Scholar]

- Buchez, Nathalie. 2011. Adaima (Upper Egypt): The Stages of State Development from the Point of View of a “Village Community”. In Egypt at Its Origins 3. Edited by Renée Friedman and Peter Fiske. Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta 205. Leuven: Peeters. [Google Scholar]

- Bunbury, Judith, Angust Graham, and Morag Hunter. 2008. Stratigraphic Landscape Analysis: Charting the Holocene Movements of the Nile at Karnak through Ancient Egyptian Time. Geoarchaeology 23: 351–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunbury, Judith, Salima Ikram, and Corinne Roughley. 2020. Holocene Large Lake Development and Desiccation: Changing Habitats in the Kharga Basin of the Egyptian Sahara. Geoarchaeology 35: 467–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busacca, Gesualdo. 2017. Places of Encounter: Relational Ontologies, Animal Depiction and Ritual Performance at Göbekli Tepe. Cambridge Archaeological Journal 27: 313–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campagno, Marcelo. 2003. Space and Shape Notes on Pre- and Proto-State Funerary Practices in Ancient Egypt. AH 17: 13–26. [Google Scholar]

- Cauvin, Jacques. 1994. The Birth of the Gods and the Origins of Agriculture, Paperback ed. New Studies in Archaeology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chaix, Louis. 2011. Cattle Skulls (Bucrania): An Universal Symbol All around the World. The Case of Kerma (Sudan). In Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2010. Edited by Miroslav Bárta, Filip Coppens and Jaromir Krejčí. Prague: Czech Institute of Egyptology, Faculty of Arts, Charles University in Prague, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Clare, Lee. 2024. Inspired Individuals and Charismatic Leaders: Hunter-Gatherer Crisis and the Rise and Fall of Invisible Decision-Makers at Göbeklitepe. Documenta Praehistorica 51: 6–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, Joanne, Nick Brooks, Edward B. Banning, Miryam Bar-Matthews, Stuart Campbell, Lee Clare, Mauro Cremaschi, Savino di Lernia, Nick Drake, Marina Gallarino, and et al. 2015. Climatic Changes and Social Transformations in the Near East and North Africa during the “Long” 4th Millennium BC: A Comparative Study of Environmental and Archaeological Evidence. Quaternary Science Reviews 136: 96–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croucher, Karina. 2018. Keeping the Dead Close: Grief and Bereavement in the Treatment of Skulls from the Neolithic Middle East. Mortality 23: 103–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Czekaj-Zastawny, Agnieszka, and Jacek Kabaciński. 2015. New Final Neolithic Cemetery E-09-4, Gebel Ramlah Playa, Western Desert of Egypt. In Hunter-Gatherers and Early Food Producing Societies in the Northeastern Africa. Edited by Jacek Kabaciński, Marek Chłodnicki and Michal Kobusiewicz. Studies in African Archaeology 14. Poznań: Poznań Archaeological Museum Publications. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Descola, Philippe. 2012. Más allá de Naturaleza y Cultura. Buenos Aires: Amorrortu Ediciones. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Descola, Philippe. 2014. The Grid and the Tree: Reply to Marshall Sahlins’ Comment. HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 4: 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietrich, Oliver. 2024. Shamanism at Early Neolithic Göbekli Tepe, southeastern Turkey. Methodological contributions to an archaeology of belief. Praehistorische Zeitschrift 99: 9–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietrich, Oliver, and Jens Notroff. 2015. A Sanctuary, or so Fair a House? In Defense of an Archaeology of Cult at Pre-Pottery Neolithic Göbekli Tepe. In Defining the Sacred: Approaches to the Archaeology of Religion in the Near East. Edited by Nicola Laneri. Oxford: Oxbow Books. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietrich, Oliver, Laura Dietrich, and Jens Notroff. 2019. Anthropomorphic Imagery at Göbekli Tepe. In Human Iconography and Symbolic Meaning in Near Eastern Prehistory. Edited by Jörg Becker, Claudia Beuger and Bernd Müller-Neuhof. Viena: Austrian Academy of Science. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- di Lernia, Savino. 2006. Building Monuments, Creating Identity: Cattle Cult as a Social Response to Rapid Environmental Changes in the Holocene Sahara. Quaternary International 151: 50–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijk-Coombes, Renate Marian van. 2013. The Use of Bucrania in the Architecture of First Dynasty Egypt. Journal for Semitics 22: 449–63. [Google Scholar]

- Dosse, François. 2012. Histoire du structuralisme. Tome 2, Le chant du cygne, 1967 à nos jours. Paris: La Découverte. [Google Scholar]

- Eliade, Mircea. 2011. El mito del eterno retorno: Arquetipos y repetición, 3rd ed. El libro de bolsillo. Madrid: Alianza. [Google Scholar]

- Eliade, Mircea. 2016. Herreros y alquimistas, 3rd ed. El libro de bolsillo. Humanidades. Madrid: Alianza. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, Renée. 2008. The Cemeteries of Hierakonpolis. Archeo-Nil 18: 8–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garfinkel, Yosef, and Sarah Krulwich. 2023. Avian Depiction in the Earliest Neolithic Communities of the Near East. Levant 55: 133–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatto, Maria. 2012. The Holocene Prehistory of the Nubian Eastern Desert. In The History of the Peoples of the Eastern Desert. Los Angeles: Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press at UCLA. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girardi, Chloé. 2017. Diversity in Body Treatment in the Predynastic Cemetery at Naga Ed-Deir (N 7000). In Egypt at Its Origins 5, Proceedings of the Fifth International Conference “Origin of the State. Predynastic and Early Dynastic Egypt”, Cairo, Egypt, 13–18 April 2014. Edited by Béatrix Midant-reynes and Yann Tristant. Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta 260. Leuven: Peeters. [Google Scholar]

- González-Ruibal, Alfredo, and Marisa Ruiz-Gálvez. 2016. House Societies in the Ancient Mediterranean (2000–500 BC). Journal of World Prehistory 29: 383–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goren, Yuval, A. Nigel Goring-Morris, and Irena Segal. 2001. The Technology of Skull Modelling in the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (PPNB): Regional Variability, the Relation of Technology and Iconography and Their Archaeological Implications. Journal of Archaeological Science 28: 671–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graeber, David, and David Wengrow. 2022. El amanecer de todo: Una nueva historia de la humanidad. Barcelona: Ariel. [Google Scholar]

- Graves-Brown, Carolyn. 2006. Emergent Flints. In Through a Glass Darkly: Magic, Dreams and Prophecy in Ancient Egypt. Edited by Kasia Szpakowska. Swansea: The Classical Press of Wales. [Google Scholar]

- Haddow, Scott D., and Christopher J. Knüsel. 2017. Skull Retrieval and Secondary Burial Practices in the Neolithic Near East: Recent Insights from Çatalhöyük, Turkey. Bioarchaeology International 1: 52–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartung, Ulrich. 2018. Cemetery U at Umm El-Qaab and the Funeral Landscape of the Abydos Region in the 4th Millennium BC. In Desert and the Nile. Prehistory of the Nile Basin and the Sahara Papers in Honour of Fred Wendorf. Edited by Jacek Kabaciński, Marek Chłodnicki, Michal Kobusiewicz and Malgorzata Winiarska-Kabacińska. Studies in African Archaeology 15. Poznań: Poznan Archaeological Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, Fekri. 2004. Between Man and Goddess: The Fear of Nothingness and Dismemberment. In Egypt at Its Origins: Studies in Memory of Barbara Adams. Edited by Stan Hendrickx, Renée Friedman, Krzysztof Ciałowicz and Marek Chlodnicki. Orientalia Lovanensia Analecta 138. Leuven: Peeters. [Google Scholar]

- Hodder, Ian. 2009. An Archaeological Response. Paléorient 35: 109–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodder, Ian, and Lynn Meskell. 2011. A “Curious and Sometimes a Trifle Macabre Artistry”: Some Aspects of Symbolism in Neolithic Turkey. Current Anthropology 52: 235–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honegger, Matthieu. 2018. La plus Ancienne Tombe Royale Du Royaume de Kerma En Nubie. Bulletin de La Société Neuchâteloise Des Sciences Naturelles 138: 185–98. [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz, Liora, and Adrian Goring-Morris. 2004. Animals and Ritual during the Levantine PPNB: A Case Study from the Site of Kfar Hahoresh, Israel. Anthropozoologica 39: 165–78. [Google Scholar]

- Ibáñez, Juan José, Jesús E. González-Urquijo, and Frank Braemer. 2014. The Human Face and the Origins of the Neolithic: The Carved Bone Wand from Tell Qarassa North, Syria. Antiquity 88: 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, Jana, Thomas F. G. Higham, Ron Oldfield, Terry P. O’Connor, and Stephen A. Buckley. 2014. Evidence for Prehistoric Origins of Egyptian Mummification in Late Neolithic Burials. PLoS ONE 9: e103608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kendall, Timothy. 1997. Kerma and the Kingdom of Kush, 2500–1500 BC: The Archaeological Discovery of an Ancient Nubian Empire. Washington, DC: National Museum of African Art. [Google Scholar]

- Kobusiewicz, Michał, Jacek Kabacinski, Romual Schild, Joel Irish, and Fred Wendorf. 2009. Burial Practices of the Final Neolithic Pastoralists at Gebel Ramlah, Western Desert of Egypt. British Museum Studies in Ancient Egypt and Sudan 13: 147–74. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalska, Agniezska, Kamil Kuraszkiewicz, and Zbigniew Godziejewski. 2009. Old Kingdom Burials with Funerary Plaster Masks from Saqqara. In Egypt 2009: Perspectives of Research. Edited by Joanna Popielska-Grzybowska and Jadwiga Iwaszczuk. Pułtusk: The Pułtusk Academy of Humanities. [Google Scholar]

- Köksal-Schmidt, Çiğdem, and Klaus Schmidt. 2010. The Göbekli Tepe “Totem Pole”: A First Discussion of an Autumn 2010 Discovery (PPN, Southeastern Turkey). Neo-Lithics: The Newsletter of Southwest Asian Neolithic Research 1: 74–76. [Google Scholar]

- Kuijt, Ian. 2008. The Regeneration of Life: Neolithic Structures of Symbolic Remembering and Forgetting. Current Anthropology 49: 171–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuper, Rudolph, and Stefan Kröpelin. 2006. Climate-Controlled Holocene Occupation in the Sahara: Motor of Africa’s Evolution. Science 313: 803–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurth, Gottfried, and Olav Röhrer-Ertl. 1981. On the Anthropology of the Mesolithic to Chalcolithic Human Remains from the Tell Es-Sultan in Jericho Jordan. Jerusalem: British School of Archaeology. [Google Scholar]

- Latour, Bruno. 1993. Nunca Hemos sido Modernos: Ensayo de Antropología Moderna. Madrid: Debate. [Google Scholar]

- Lohmann, Roger Ivar. 2005. The Afterlife of Asabano Corpses: Relationships with the Deceased in Papua New Guinea. Ethnology 44: 189–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, Lisa A., Edward Banning, and Michael Chazan. 2011. Oasis or Mirage? Assessing the Role of Abrupt Climate Change in the Prehistory of the Southern Levant. Cambridge Archaeological Journal 21: 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, Katie, and Adrian Timpson. 2014. The Demographic Response to Holocene Climate Change in the Sahara. Quaternary Science Reviews 101: 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahon, Augusta. 2016. The Encultured Vulture: Late Chalcolithic Sealing Images and the Challenges of Urbanism in 4th Millennium Northern Mesopotamia. Paléorient 42: 169–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellaart, James. 1967. Catal Huyuk: A Neolithic Town in Anatolia. London: Thames and Hudson. [Google Scholar]

- Meskell, Lynn. 2003. Memory’s Materiality: Ancestral Presence, Commemorative Practice and Disjunctive Locales. In Archaeologies of Memory. Edited by Ruth M. Van Dyke and Susan E. Alcock. Hoboken: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Meskell, Lynn. 2008. The Nature of the Beast: Curating Animals and Ancestors at Çatalhöyük. World Archaeology 40: 373–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mithen, Steven, Amy Richardson, and Bill Finlayson. 2023. The Flow of Ideas: Shared Symbolism during the Neolithic Emergence in Southwest Asia: WF16 and Göbekli Tepe. Antiquity 97: 829–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz Herrera, Antonio. 2024a. Entre Naturaleza y cultura. Paisaje, familia y cognición en el desarrollo funerario predinástico de Abydos. In La familia en la Antigüedad. Estudios desde la interdisciplinariedad. Edited by Ana Martín Minguijón, José Nicolás Saiz López and Karen María Vilacoba Ramos. Ciencias de la Antigüedad 1. Madrid: Dykinson. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz Herrera, Antonio. 2024b. Sobre La Reciprocidad de Naturaleza y Cultura. La Cognición 4E y Su Perspectiva Arqueológica En El Paisaje. El Futuro Del Pasado 16: 455–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz Herrera, Antonio. 2025a. El Paisaje en el Antiguo Egipto. Naturaleza, Cognición y Sacralidad en los espacios funerarios. Archaeopress Egyptology 50. Oxford: Archaeopress. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz Herrera, Antonio. 2025b. Entheotopos. On A Heuristic Viewpoint Concerning Sacred Landscapes Creation in Ancient Egypt. Cambridge Archaeological Journal 35: 279–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz Herrera, Antonio. 2025c. Totem and Taboo: Dismemberment, Landscape Ontology, and Cultural Memory in Pre-Dynastic Egyptian Culture. In La Muerte En La Antigüedad. Estudios Desde La Interdisciplinariedad. Edited by Ana Martín Minguijón, José Nicolás Saiz López and Karen María Vilacoba Ramos. CIENCIAS DE LA ANTIGÜEDAD 2. Madrid: Dykinson. [Google Scholar]

- Naveh, Danny, and Nurit Bird-David. 2014. Animism, Conservation, and Immediacy. In The Handbook of Contemporary Animism. Edited by Graham Harvey. Acumen Handbooks. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Nowell, April, and Danielle Macdonald. 2024. Culturing the Body in the Context of the Neolithisation of the Southern Levant. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 55: 104478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özdogan, Mehmet. 2009. Comments. Paléorient 35: 121–23. [Google Scholar]

- Palecek, Martin. 2022. The Ontological Turn Revisited: Theoretical Decline. Why Cannot Ontologists Fulfil Their Promise? Anthropological Theory 22: 154–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peet, Thomas Eric. 1914. The Cemeteries of Abydos. Part. II, 1911–1912. Excavation Memoir—Egypt Exploration Society. London: The Egypt Exploration Fund. [Google Scholar]

- Petrie, William Matthew Flinders, and James Edward Quibell. 1896. Naqada and Ballas. 1895. London: Cornell University Library. [Google Scholar]

- Pilloud, Marin A., Scott D. Haddow, Christopher J. Knüsel, and Clark Spencer Larsen. 2016. A Bioarchaeological and Forensic Re-Assessment of Vulture Defleshing and Mortuary Practices at Neolithic Çatalhöyük. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 10: 735–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, Seth. 2007. Death and Dismemberment in Mesopotamia: Discorporation between the Body and Body Politic. In Performing Death: Social Analyses of Funerary Traditions in the Ancient Mediterranean. Edited by Nicola Lanery. Chicago: The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. [Google Scholar]

- Rollefson, Gary. 2000. Ritual and Social Structure at Neolithic ’Ain Ghazal. In Life in Neolithic Farming Communities. Edited by Ian Kuijt. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowan, Yorke M., Gary O. Rollefson, Alexander Wasse, Wael Abu-Azizeh, Austin C. Hill, and Morag M. Kersel. 2015. The “Land of Conjecture:“ New Late Prehistoric Discoveries at Maitland’s Mesa and Wisad Pools, Jordan. Journal of Field Archaeology 40: 176–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahlins, Marshall. 2014. On the Ontological Scheme of Beyond Nature and Culture. HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 4: 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]