Liquid Spirituality in Post-Secular Societies: A Mental Health Perspective on the Transformation of Faith

Abstract

1. From Church to Couch: The Rise of Secular Spirituality and Its Psychological Hopes

1.1. Rise of Alternative and Secular Spirituality

1.2. “Liquid Spirituality” in the Liquid Age

Fluids travel easily … unlike solids, they are not easily stopped–they pass around some obstacles, dissolve some others, and bore or soak their way through others still … These are reasons to consider ‘fluidity’ or ‘liquidity’ as fitting metaphors when we wish to grasp the nature of the present, in many ways novel, phase in the history of modernity.

Cloakroom communities need a spectacle which appeals to similar interests dormant in otherwise disparate individuals and so bring them all together for a stretch of time when other interests—those which divide them instead of uniting—are temporarily laid aside, put on a slow burner or silenced altogether. Spectacles as the occasion for the brief existence of a cloakroom community do not fuse and blend individual concerns into ‘group interest’; by being added up, the concerns in question do not acquire a new quality, and the illusion of sharing which the spectacle may generate would not last much longer than the excitement of the performance.(p. 200)

2. A Case Study of Religiosity, Spirituality, and Mental Health in Six Highly Secular European Countries

2.1. Religious Profiles

2.2. The Societal Trends in Religiosity and Spirituality

2.3. Incorporation of Spirituality in Mental Care

- Denmark: The state church framework supports a chaplaincy model that provides optional spiritual care but excludes evangelism. For non-religious Danes, secular practices—such as mindfulness, meditation, and nature- or forest-bathing—have become prominent tools for holistic well-being.

- Sweden: The Church of Sweden continues to supply chaplains across hospitals, hospices, and the military, focusing on emotional and existential support. Standard practice includes respecting a patient’s worldview and offering access to imams, rabbis, or humanist counselors upon request. Sweden was also among the first to officially include humanist chaplains—nonreligious professionals who address existential concerns without invoking religious doctrine.

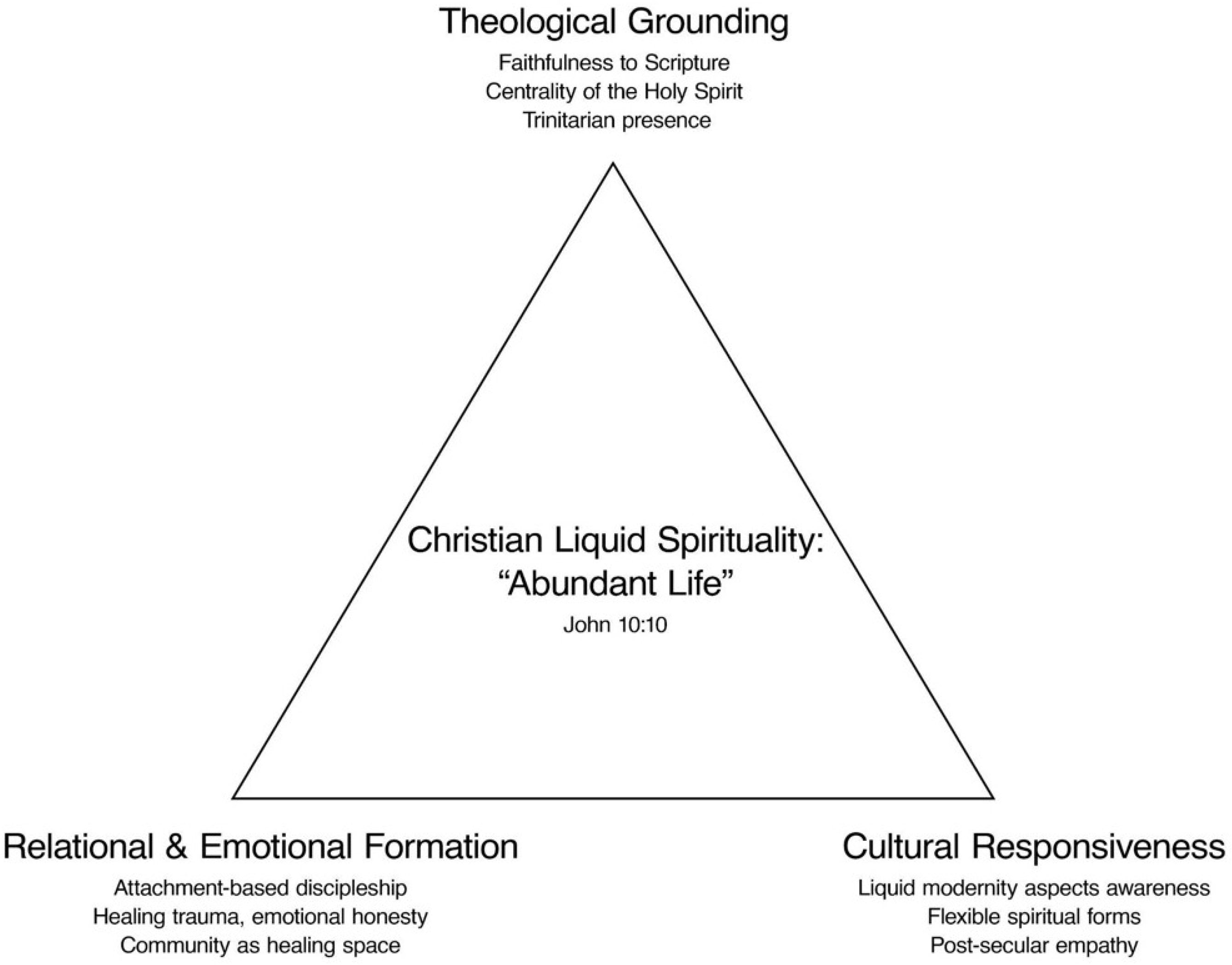

3. From Fragmentation to Formation: Toward a New Christian Liquid Spirituality

If we can show that we are concerned for the well-being of other people, not because we are seeking cultural or institutional dominance, but because working for the common good is a facet of participating in the abundant life offered through Christ, we can open a new door of engagement with the culture … we can find ways of building credibility even in a secular context.

- Emotional and psychological healing as integral to discipleship (not peripheral to it), including honest engagement with trauma, loss, attachment wounds, and unmet needs.

- Experiential and existential engagement with Scripture, through practices such as lectio divina, biblical storytelling, and therapeutic hermeneutics that read texts not just for information but for transformation.

- Embodied worship and contemplative practices, such as silence, Christian meditation, music, and movement, offering forms of encounter that transcend rational explanation and speak to the heart. Embodied practices help in inner healing and thus increase the well-being level by connecting the explicit (rational) knowledge to the implicit (gut-level, emotional, Spirit-led) knowledge, as proposed by Hall (Hall and Hall 2021).

- Community as a healing space, where belonging is not based on doctrinal conformity but on shared vulnerability, mutual care, and Spirit-shaped relational dynamics. We urge for open Christian communities that are in their core deeply missional, and therefore not judgmental but offering a space for transformative encounter with God.

- A theology of the Spirit that empowers agency without radical individualism—where the Spirit calls and equips people not just for church work but for inner healing, ethical living, and mission in the world.

- A missional expression of faith that does not start with propositional truth and ends with baptism, but starts and continues with presence, compassion, empathy, and discernment of spiritual hunger in others. Then this process of spiritual growth, in which we are “loved into loving” (Hall and Hall 2021) by God through others, and others are “loved into loving” by God through us, never ends.

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bauman, Zygmunt. 2000. Liquid Modernity. Cambridge: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Beláňová, Andrea. 2022. ‘The Core of My Work Is in Being with People Who Do Not Practice Faith in Any Way’: The Self-Perception of Czech Hospital Chaplains. Sociologický časopis/Czech Sociological Review 58: 285–308. Available online: https://www.soc.cas.cz/images/drupal/publikace/csr_000063_fin-0003.pdf (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- Berger, Peter L. 1967. The Sacred Canopy: Elements of a Sociological Theory of Religion. New York: Doubleday. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, Peter L. 1999. The Desecularization of the World: Resurgent Religion and World Politics. Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co. [Google Scholar]

- Blankholm, Joseph. 2022. The Secular Paradox: On the Religiosity of the Not Religious. New York: NYU Press. [Google Scholar]

- Braam, Arjan W., and Harlod G. Koenig. 2019. Religion, Spirituality and Depression in Prospective Studies: A Systematic Review. Journal of Affective Disorders 257: 428–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castillejos-Anguiano, Ma Carmen, Paloma Huertas, Paloma Martín-Guerrero, and Berta Moreno-Küstner. 2019. Prevalence of Suicidality in the European General Population: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Malga: Universidad de Malga. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/10.1080/13811118.2020.1765928?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%20%200pubmed (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- Census. 2021. Religious Belief. Available online: https://scitani.gov.cz/religious-beliefs (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- CNE.News. 2022. Most Dutch People Do Not Belong to a Church. Christian Network Europe. December 26. Available online: https://cne.news/article/2287-most-dutch-people-do-not-belong-to-a-church (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- Czech Republic, Ministry of Health. 2019. Minister of Health and Church Representatives Signed the First Annually Agreement on Spiritual Care in Health Care. Available online: https://mzd.gov.cz/tiskove-centrum-mz/ministr-zdravotnictvi-a-zastupci-cirkvi-podepsali-historicky-prvni-dohodu-o-duchovni-peci-ve-zdravotnictvi/ (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- Činčala, Petr. 2024. The Missing Blue in Adventism: A Gap in Discipleship and Mission. Journal of Adventist Mission Studies 20: 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, Richard J., and Alfred W. Kaszniak. 2015. Conceptual and Methodological Issues in Research on Mindfulness and Meditation. American Psychologist 70: 581–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobbelaere, Karel. 1981. Secularization: A Multi-Dimensional Concept. Current Sociology 29: 1–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estonia Counts. 2022. Population Census. The Proportion of People with a Religious Affiliation Remains Stable, Orthodox Christianity Is Still the Most Widespread. Statistics Estonia. November 2. Available online: https://rahvaloendus.ee/en/news/population-census-proportion-people-religious-affiliation-remains-stable-orthodox-christianity-still-most-widespread (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- Eurobarometer. 2007. Intercultural Dialogue in Europe. Brussels: European Commission. Available online: https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/browse/all/series/8929 (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- Eurobarometer. 2023. Mental Health. Brussels: European Commission, October, Available online: https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/detail/3032 (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- Evans, Jonathan. 2017. Unlike Their Central and Eastern European Neighbors, Most Czechs Don’t Believe in God. Washington: Pew Research Center, June 19, Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2017/06/19/unlike-their-central-and-eastern-european-neighbors-most-czechs-dont-believe-in-god/ (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- Evans, Jonathan, and Chris Baronavski. 2018. How Do European Countries Differ in Religious Commitment? Use Our Interactive Map to Find Out. Washington: Pew Research Center, December 5, Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2018/12/05/how-do-european-countries-differ-in-religious-commitment/ (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- Frankl, Viktor E. 2006. Man’s Search for Meaning. Boston: Beacon Press. [Google Scholar]

- General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists, Office of Archives, Statistics, and Research. 2023. Global Church Member Survey 2023. Silver Spring: General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists. [Google Scholar]

- Habermas, Jürgen. 2006. Religion in the Public Sphere. European Journal of Philosophy 14: 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habermas, Jürgen. 2008. Notes on a Post-Secular Society. Available online: http://print.signandsight.com/features/1714.html (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- Hackett, Conrad, Marcin Stonawski, Yunping Tong, Stephanie Kramer, Anne Shi, and Dalia Fahmy. 2025. How the Global Religious Landscape Changed from 2010 to 2020. Washington: Pew Research Center, June 9, Available online: https://doi.org/10.58094/fj71-ny11 (accessed on 14 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- Hadden, Jeffrey K. 1987. Toward Desacralizing Secularization Theory. Social Forces 65: 587–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, Todd W., and M. Elizabeth L. Hall. 2021. Relational Spirituality: A Psychological-Theological Paradigm for Transformation. Downers Grove: IVP Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Heelas, Paul. 1996. The New Age Movement: The Celebration of the Self and the Sacralization of Modernity. Oxford: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Heelas, Paul, and Linda Woodhead. 2005. The Spiritual Revolution: Why Religion Is Giving Way to Spirituality. Malden: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- International Association for Suicide Prevention (IASP). 2025. New WHO Suicide Data Reaffirms Urgent Need for Global Prevention Efforts. June 2. Available online: https://www.iasp.info/2025/06/02/who-suicide-data/ (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- Kasen, Stephanie, Priya Wickramaratne, Marc J. Gameroff, and Myrna M. Weissman. 2012. Religiosity and resilience in persons at high risk for major depression. Psychological Medicine 42: 509–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koenig, Harold G., Linda K. George, and Bercedis L. Peterson. 1998. Religiosity and Remission of Depression in Medically Ill Older Patients. American Journal of Psychiatry 155: 536–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koenig, Harold G., Michael E. McCullough, and David B. Larson. 2001. Handbook of Religion and Health. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lesage, Kirsten, Kelsey Jo Starr, and William Miner. 2025. Around the World, Many People Are Leaving Their Childhood Religions. Washington: Pew Research Center, March 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucchetti, Giancarlo, Harold G. Koenig, and Alessandra L. G. Lucchetti. 2021. Spirituality, religiousness, and mental health: A review of the current scientific evidence. World Journal of Clinical Cases 9: 7620–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lynn, Sarah, and Julia C. Basso. 2023. Effects of a Neuroscience-Based Mindfulness Meditation Program on Psychological Health: Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Formative Research 7: e40135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayer, Jean-François. 2015. Estonia not religious, but still spiritual? Religion Watch Archives. July 1. Available online: https://www.rwarchives.com/2015/07/estonia-not-religious-but-still-spiritual/ (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- Nešpor, Zdeněk, and David Václavík. 2008. Současná česká religiozita: Sociologická perspektiva. Prague: Malvern. [Google Scholar]

- Partridge, Christopher H. 2004. The Re-Enchantment of the West: Alternative Spiritualities, Sacralization, Popular Culture and Occulture. London: T&T Clark International, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Partridge, Christopher H. 2005. The Re-Enchantment of the West: Alternative Spiritualities, Sacralization, Popular Culture and Occulture. London: T&T Clark International, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. 2017. Religious Belief and National Belonging in Central and Eastern Europe. May 10. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2017/05/10/religious-belief-and-national-belonging-in-central-and-eastern-europe/ (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- Robertson, Roland. 2007. Global Millennialism: A Postmortem on Secularization. In Religion, Globalization, and Culture. Edited by Peter Beyer and Lori Beaman. Leiden: Brill, pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Scazzero, Peter. 2017. Emotionally Healthy Spirituality: It’s Impossible to Be Spiritually Mature, While Remaining Emotionally Immature. Grand Rapids: Zondervan. [Google Scholar]

- Sherwood, Harriet. 2018. ‘Christianity as Default Is Gone’: The Rise of a Non-Christian Europe. The Guardian. March 20. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/mar/21/christianity-non-christian-europe-young-people-survey-religion (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- Smith, Timothy B., Michael E. McCullough, and Justin Poll. 2003. Religiousness and Depression: Evidence for a Main Effect and the Moderating Influence of Stressful Life Events. Psychological Bulletin 129: 614–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Statistics Netherlands (CBS). 2024. The Netherlands in Numbers: What Are the Major Religions? Available online: https://longreads.cbs.nl/the-netherlands-in-numbers-2024/what-are-the-major-religions/ (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- Svenska kyrkan [Church of Sweden]. 2021. Svenska Kyrkans Medlemsutveckling år 1972–2020 [Church of Sweden’s Membership Development in 1972–2020]. Available online: https://www.svenskakyrkan.se/filer/d0a30387-feff-48b3-810e-2c8225f2fb54.pdf?id=2705246 (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- Taylor, Charles. 1991. The Ethics of Authenticity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Teasdale, Mark R. 2022. Participating in Abundant Life: Holistic Salvation for a Secular Age. Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press. [Google Scholar]

- van Dierendonck, Dirk. 2012. Spirituality as an Essential Determinant for the Good Life, Its Importance Relative to Self-determinant Psychological Needs. Journal of Happiness Studies 13: 685–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Walach, Harald. 2014. Secular Spirituality: The Next Step Towards Enlightenment. Cham: Springer. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- WHO (World Health Organization). 2025. Depressive Disorder (Depression). Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression (accessed on 13 September 2025).[Green Version]

- Wikipedia. 2024. Irreligion in the Czech Republic. Wikipedia Foundation. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Irreligion_in_the_Czech_Republic (accessed on 6 December 2024).[Green Version]

- Wikipedia. 2025a. Religion in Belgium. Wikipedia Foundation. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Religion_in_Belgium (accessed on 4 September 2025).[Green Version]

- Wikipedia. 2025b. Religion in Denmark. Wikipedia Foundation. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Religion_in_Denmark (accessed on 4 September 2025).[Green Version]

- Wikipedia. 2025c. Religion in the Czech Republic. Wikipedia Foundation. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Religion_in_the_Czech_Republic (accessed on 4 June 2025).[Green Version]

| Country | Population 2021 | Main Historic Religion | Non-Religious/Unaffiliated (Approx.) | Actively Religious (Approx.) a* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belgium | 11,521,238 b | Catholic | ~30% c | 10% * |

| Czechia | 10,524,167 d | Catholic (historically) | ~72% unaffiliated e | 11% f |

| Denmark | 5,840,045 g | Lutheran (state church) | ~30% unaffiliated h | 10% * |

| Estonia | 1,331,824 i | Lutheran (nominal); Orthodox minority | ~54% unaffiliated j | 9% k |

| Netherlands | 17,337,403 l | Mixed Protestant/Catholic (historically) | ~57% unaffiliated m | 15% * |

| Sweden | 10,415,811 n | Lutheran (former state church) | ~52% unaffiliated o | 9% * |

| Country | SDA Church Membership and % of Population 2021 | Average Annual Growth Rate (2012–2021) | Number of Citizens per 1 Seventh-day Adventist |

|---|---|---|---|

| Belgium | 2979 (0.03%) | 3.29% | 3867 |

| Czechia | 7349 (0.07%) | −1.57% | 1430 |

| Denmark | 2379 (0.04%) | −0.53% | 2445 |

| Estonia | 1287 (0.10%) | −2.31% | 1035 |

| Netherland | 5996 (0.03%) | 2.13% | 2891 |

| Sweden | 2911 (0.03%) | 0.53% | 3578 |

| Country | Prevalence of Depressive Disorders 2021 a | Depression or Anxiety 2023 b | Age-Standardized Suicide Rate 2021 c |

|---|---|---|---|

| Belgium | 5% | 37% | 14% |

| Czechia | 5% | 48% | 10% |

| Denmark | 5% | 34% | 8% |

| Estonia | 6% | 50% | 13% |

| Netherland | 5% | 35% | 9% |

| Sweden | 6% | 55% | 12% |

| Country | SDA GCMS 2023 Sample Size | Little Interest or Pleasure in Doing Things | Feeling Down, Depressed, or Hopeless | Suicidal Thoughts |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belgium | 9 | 33.3% | 33.3% | 0% * |

| Czechia | 110 | 43.6% | 43.9% | 8.9% |

| Denmark | 21 | 33.3% | 33.3% | 0% * |

| Estonia | 40 | 59.0% | 47.5% | 7.5% |

| Netherland | 48 | 26.8% | 25.5% | 4.5% |

| Sweden | 58 | 25.9% | 25.9% | 5.2% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Eder, P.; Činčala, P. Liquid Spirituality in Post-Secular Societies: A Mental Health Perspective on the Transformation of Faith. Religions 2025, 16, 1308. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16101308

Eder P, Činčala P. Liquid Spirituality in Post-Secular Societies: A Mental Health Perspective on the Transformation of Faith. Religions. 2025; 16(10):1308. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16101308

Chicago/Turabian StyleEder, Pavel, and Petr Činčala. 2025. "Liquid Spirituality in Post-Secular Societies: A Mental Health Perspective on the Transformation of Faith" Religions 16, no. 10: 1308. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16101308

APA StyleEder, P., & Činčala, P. (2025). Liquid Spirituality in Post-Secular Societies: A Mental Health Perspective on the Transformation of Faith. Religions, 16(10), 1308. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16101308