Abstract

Pre-modern Indian subcontinent provides a treasure trove of art historical data in the form of stone sculptures and reliefs to study dance. While significant steps towards understanding the literary and visual language of dance have been made, artistic production from Gandhāra (the ancient region broadly covering the northwestern part of the subcontinent) largely remains absent in scholarly discussions. Ancient Gandhāra readily lends itself to a global approach as an active participant alongside the so-called ancient Silk Roads connecting the Mediterranean regions with China. Furthermore, as part of the Buddhist pilgrimage routes, Gandhāra also developed ties with Buddhist sites located further east and participated in the spread of Buddhism to China. Within this context, this article discusses the most common dance depicted in Gandhāran art to understand how artists represented dance in the static medium. Using this dance as an illustration, this article also argues that the iconographic conventions of the Gandhāran artistic repertoire for dance are shared outside the region, notably in Kizil, which is located alongside the northern branch of the Silk Roads.

1. The Language of Dance in the Indian Subcontinent

It is customary to begin any systematic study on dance in the Indian subcontinent with the earliest authoritative texts codifying performances. As the most important text, the Nāṭyaśāstra or the ‘Treatise on Theater’ has been the object of dance-related studies since the 1930s.1 The Nāṭyaśāstra consists of thirty-six or thirty-seven chapters addressing different aspects of theater and can be dated roughly between the second century BCE and the second century CE. Its authorship is attributed to the mythical Bharata who introduced the art of nāṭya (sometimes translated as dance-theater, drama or play) to humans to combat the moral degradation of society. This nāṭya comprised different elements such as rituals, music, and dancing.

Dance or nṛtta is dealt with in Chapter 4 of the Nāṭyaśāstra using highly technical instructions and mythological narratives. Often placed in opposition to mimetic dance (nṛtya), nṛtta is defined as an abstract dance that does not contain narrative content.2 The Nāṭyaśāstra outlines how nṛtta consists of 108 karaṇas (units of dance) comprising limb movements and hand gestures (hasta/mudrā).3 The various combinations of the karaṇas provide larger choreutic sequences called the aṅgaharas, which consist of 32 linear measurements, poses and stances. These sequences, when they appear in other mediums, such as paintings and sculptures, can be identified as dance.4

The study of art historical evidence in the light of Nāṭyaśāstra’s karaṇas has certainly led to the development of nuanced methodological approaches. Traditionally, karaṇas were thought to be static poses; however, it is now accepted that they are part of a whole movement consisting of a beginning, the course of the movement, and an end. This is particularly useful when studying the representation of dance in sculptures where only static poses can be identified. On this understanding, Vatsyayan astutely remarked that ‘the plastic can capture only a single moment in a continuous flow of movements and only suggests through the arrested image the moment before or after’.5 If the karaṇas in plastic arts are a series of movements, then images represent a snapshot of different moments associated with dance.6 This allows for an unlimited number of representations of dance movements in sculptures that stem from the different stages of the 108 karaṇas.7

Such codified dance movements found in texts from the Indian subcontinent find a limited echo in the corpus of Gandhāran art, which is commonly associated with the ancient region of Gandhāra (Figure 1). The corpus of Gandhāran art consists mainly of schist and stucco reliefs and statues dating broadly from the first to the fourth century CE.8 The dance movements found in Gandhāran reliefs do not correspond to the descriptions found in Indic texts. However, viewing ‘petrified’ static poses of dance in art as part of dynamic performances is useful in our context where the primary source of information is stone reliefs. In order to systematically study dance, this article will show that the representation of dance in Gandhāran art was highly motivated by particular visual conventions. When studied together, reliefs belonging to diverse geographical and chronological periods present a limited repertoire of movements associated with dancing figures.

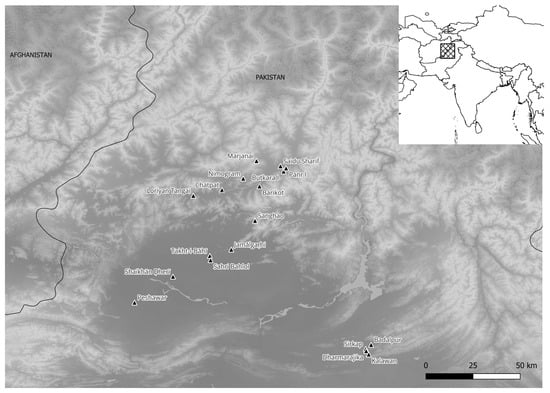

Figure 1.

Important Buddhist Sites in the Gandhāran region. Source: author (in collaboration with Adam Wijker).

As a prolegomenon to dance in Gandhāran art, the present article examines one form of dance executed by both male and female figures on schist reliefs.9 Multiple forms of dance are depicted in Gandhāran art, such as the ‘Persian snap’, and this article engages with a dance that I provisionally label as ‘Indic’.10 The iconographic conventions related to the Indic dance studied in this article have a strong relationship to dance imagery from major sites such as Sānchi and Bhārhut. In comparing the representations of our Indic dance with images from other Indian Buddhist sites, we can see that the dancing figures wear similar costumes and perform variations of the same movement.

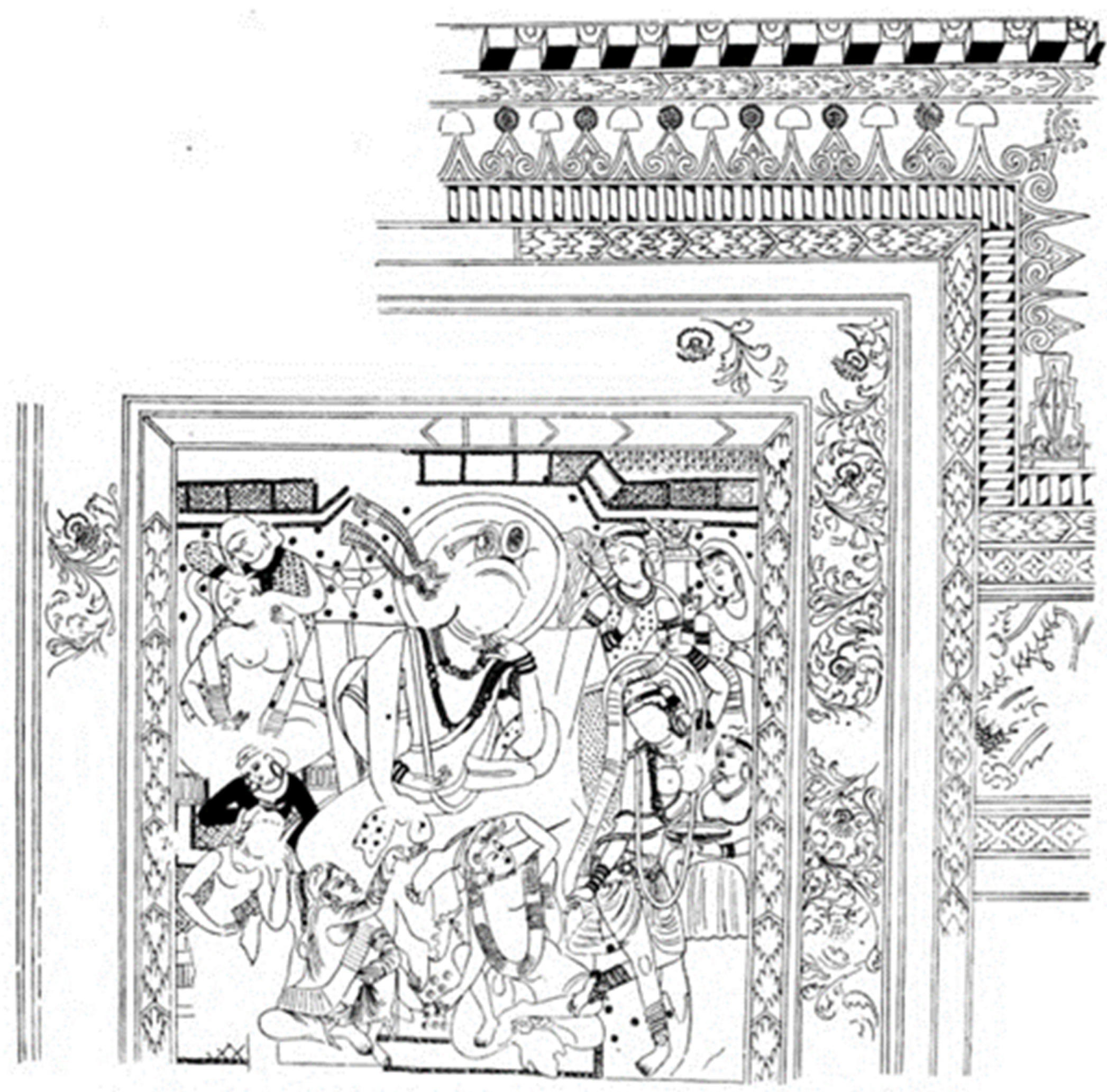

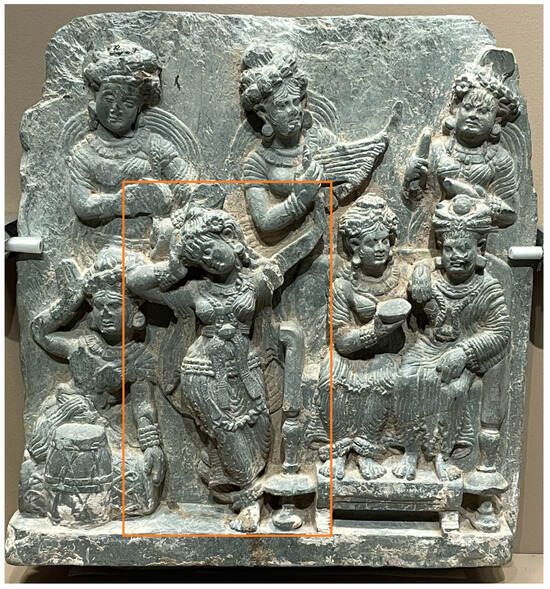

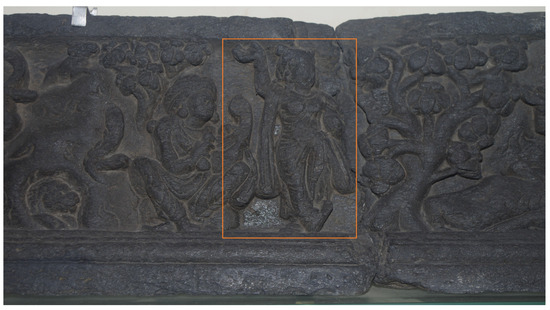

I wish to illustrate this striking similarity using two examples: Figure 2 and Figure 3. See the dancer centrally depicted in Figure 2, which is from Gandhāra, and likely from the Swāt Valley, and the two dancers on the bottom register in Figure 3, which is from the Bhārhut stūpa: these figures execute the same movement. Moreover, both these dances occur in courtly settings, although their purpose varies. In Figure 2, a female dancer performs in the palace of Siddhārtha and in Figure 3, female dancers perform in the palace of Indra. We will encounter Figure 2 once again in this article, so let us turn to an interesting detail in Figure 3. An inscription found on the dome of Indra’s palace identifies the scene as the cūḍāmaha (literally, the festival of the hair crest). It suggests that the dance is taking place as part of a festive celebration. The focus of the dance is the hair relic, indicated by Prince Siddhārtha’s turban, located under the inscription.11 Despite the different purposes of the dances, even a cursory glance at Figure 2 and Figure 3 reveals that the conventions used to depict dance in these images are nearly identical. Only stylistic and aesthetical elements related to the figures’ costume and jewelry differ, but these can be explained based on regional choices made by the artists.

Figure 2.

Siddhārtha surrounded by female musicians and a dancer, a relief likely from the Swāt Valley (c. 1st century CE). Islamabad Museum, Islamabad, Pakistan. Source: Zong Zixiao.

Figure 3.

Female figures dancing alongside male musicians around the Buddha’s turban from the Bhārhut stūpa (c. 2nd–1st century BCE). Indian Museum, Kolkata, India. Source: Author.

Due to their similarities, I have tentatively labeled the reliefs depicting the variations of this dance movement as ‘Indic’. This label does not presuppose the existence of an authentic performance group that was associated with a specific Indian ethnicity. It simply allows us to define a distinct corpus of data and contrast it with other dance forms that have already received some attention in scholarly studies. Representations of this Indic dance are the focus of the first section, and so the label should be viewed simply as a shorthand to differentiate between numerous dance movements appearing in Gandhāran art whose origin and existence cannot easily be clarified using the available data.

In the second section, Gandhāran reliefs will be compared to a wall painting found in Kizil with a dancing female figure. This section will argue that at least some iconographic conventions related to the representation of dance from Gandhāra may have also been adapted by artists along the ancient Silk Roads. This comparative study provides yet another dimension to the dynamic interactions occurring between Gandhāra and Kuča via the long-distance religious and mercantile routes.

I am aware that the scope of this article only allows me to address a handful of examples. They are not meant to be representative of all dance movements found in Gandhāran art. They can only provide a small glimpse of dance based on the visual corpus of this astonishingly multicultural region. A complete inventory of dance movements in Gandhāran art is still a desideratum. While I eagerly await such a study, my modest goal in this article is to present a preliminary analysis of selected reliefs for further exploration.

Before examining the representation of dance in Gandhāran art, it is important to establish what I mean by this term. Dance is intentional, rhythmic, and stereotypical bodily movements that can be observed and identified as a special category of behavior. In Gandhāran art, the presence of abstract dance can be detected based on the position of the body and the limbs of the figures performing it. The dancing figures in art are usually depicted frontally; however, some images present the dancer from the back, perhaps indicating turns and perspectives. In visualizing our Indic dance, the figures commonly stand with their lower limbs crossed or one of them lifted upwards. For example, in Figure 4, a female dancer performs alongside a male musician with a harp. The female dancer has her lower limbs crossed in a posture that is commonly associated with dancing figures. The dance occurs on a relief depicting the Candakinnara jātaka, in which a kinnara (mythical beings) couple’s tranquil life is tragically interrupted by a lustful king. The kinnaras harmony in their forest abode is communicated by their dance and musical performances.

Figure 4.

Detail of a relief depicting the Candakinnara jātaka with a female dancer and a male musician with a harp, from Loriyan Tangai (c. 2nd–3rd century CE). Indian Museum, Kolkata, India. Source: Author.

Regarding the upper limbs, dancing figures usually hold one or both arms away from the body. We must keep in mind that non-dancing figures also perform gestures that are similar to dancing figures. However, they are rarely accompanied by musicians, which is the case when dance is represented. Moreover, the arrangement of the dancer’s body normally deviates from its central axis based on their limb movements. Such an arrangement can be favorably compared to the tribhaṅga or the triple bend pose. With this background, we will see in the following sections how the Indic dance in Gandhāran art comprises a limited (re)combination of arm and leg movements that are repeatedly highlighted by the reliefs.12

2. Finding Dance in Gandhāra Art

The Indic dance in Gandhāran art commonly occurs as part of courtly entertainment, festive celebrations, and decorations of panels depicting the Buddha’s life story. The most common context within which this dance can be identified is the palace of Prince Siddhārtha, the future Buddha Śākyamuni. The visualization of Siddhārtha’s luxurious palace life, such as in Figure 2, often includes dancers and musicians who entertain the prince.13 Usually female dancers, accompanied by musicians, perform in front of the Siddhārtha and his wife, Yaśodharā, and form part of the sensual world that is later abandoned by the prince. Similarly, dance also occurs as a form of courtly entertainment for the nāgas (serpent divinities having a human form with a snake hood, Figure 5). Since the nāgarāja (nāga king) is a royal figure in his own realm, he is often entertained by nāginī musicians and dancers.

Figure 5.

Relief with nāginīs dancing around the nāgarāja, provenance unknown (c. 2nd–3rd century CE). Musée National des Arts Asiatiques—Guimet, Paris, France. Source: Author.

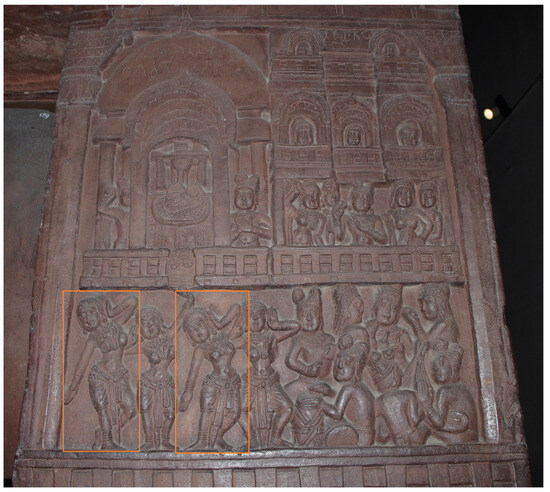

As we have already seen in Figure 3, which comes from Bhārhut, dance can also be identified in Gandhāran reliefs depicting festivals and processions. During such events, dance occurs around a range of objects such as the Buddha’s turban, stūpas (hemispherical monuments sometimes containing relics), reliquaries, and the Buddha himself (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Relief with Siddhārtha’s turban, provenance unknown (c. 2nd–3rd century CE). Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto, Canada. Source: Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto, Canada.

Besides these two contexts—courtly and festive celebrations—dancing figures also decorate architectural elements such as frames of niches and door jambs. These figures, both male and female, as we will see, perform the same variations of the Indic dance movements found in the other two contexts despite their decorative function.

Some of the datable reliefs with dancing figures in Gandhāran art come from Butkara I, one of the largest and longest-used Buddhist sites in Gandhāra. Relative dating and stratigraphy suggest that the site was used from the early third century BCE to the tenth century CE. Its foundations may have been associated with the Dharmarājikā stūpas built by the Mauryan King Aśoka (c. 304–232 BCE), and its later enlargement may be related to the Oḍirājas, a group of local Gandhāran potentates who controlled the Swāt Valley in the first century CE.14 The site, built mainly using local schist, is dominated by a large stūpa called the Great Stūpa. The systematic development of the site can be understood based on the different building periods of this Great Stūpa.15 During these building periods, the Great Stūpa was surrounded by over 227 smaller monuments including stūpas, vihāras (shrines), and columns (stambha), some of which were decorated with reliefs.

In Butkara I, at least six bas-reliefs preserve figures performing the Indic dance with relatively few variations. They can be broadly dated between the first and the third century CE based on their stylistic features. Four out of six reliefs depicting dance preserve small-sized figures within architectural settings. We will see how this architectural frame enhances the impression of the movement and restricts it to the available space. In these cases, the figures are also placed in relation to musicians either within the same architectural frame or in associated registers.

The most elaborate example of dance from Butkara I is a relief depicting two male figures under an elaborate arch (Figure 7). It is part of the category of images belonging to the stile disegnativo or drawing style. This style can be dated to the first century CE which coincides with the Saka-Parthian era as well as the local Oḍirājas.16 The main characteristics of this style are the frontal depictions of figures, flat treatment of volume, and dense lines for drapery. According to Filigenzi, these characteristics ‘show the dependence on more or less coeval Indian iconographies, evidently held as authoritative models’.17 This may further explain the striking similarity between the representations of dance in drawing style and in other Indian Buddhist sites.

Figure 7.

Musician with a harp and a dancer under an arched gateway from Butkara I (c. 1st century CE). Museo della Civiltà Romana, Rome, Italy. Source: O. Bopearachchi.

The relief depicts two male performers standing in front of an elaborate caitya arch, perhaps symbolizing a gateway. Gateways in Gandhāran art are commonly used to frame devotees, both monastic and lay, as they engage in a variety of veneration activities. They occur more frequently in the Swāt Valley, and reliefs from Butkara I and Saidu Sharif I preserve some of the most elaborate versions of these arches. However, the arches have only been identified in art and similar arches have not been unearthed at Gandhāran sites. The lack of caitya arches in the archeological record has led Brancaccio to convincingly argue that they were an imaginary space in art rather than a reference to contemporary architectural elements.18 The artists in Swāt were likely aware of central Indian architectural and artistic traditions and used certain elements to create new visual spaces with meaning. The caitya arches in Gandhāran art act as framing devices for devotional practices and make allusions to relic shrines located in the Buddha’s homeland. As zooming devices, they keep our vision focused on the figures and their actions while simultaneously placing them within a symbolic space located beyond the Swāt Valley. The figures, for their part, perform activities associated with contemporary praxis, and embed the local within the broader Buddhist landscape.

Returning to Figure 7, the two male figures are dressed similarly; they both wear a turban and a pleated lower garment.19 Their elaborate jewelry, such as the long-weighted earrings and necklaces, as well as their rich drapery, reveal their wealthy status.20 The male figure on the left holds an arched harp with a plectrum and strokes the strings of the instrument. The figure to the right performs the dance that we will also encounter in subsequent examples. Moreover, it can also be favorably compared to the representations of dance found in other Indian Buddhist sites such as the dancing figure accompanying the Bodhisattva on a relief from Amarāvatī (Figure 8). While performing this dance movement, the figure’s right arm is arched above his head and his hand reaches over his turban. His left arm is bent close to his torso and his lower limbs are crossed. His body is not haphazardly depicted but is balanced by distributing his weight to the side toward which the face is turned. Such a posture in response to music does not seem to be accidental. We will see how figures represented this way are not in the throes of movement but carefully executing a topical dance.

Figure 8.

Relief depicting scenes from the life of the Buddha, starting from the Tuṣitā heaven, the descent, and the dream of Māyā from the Amarāvatī stūpa (c. 1st century CE). Indian Museum, Kolkata, India. Source: Author.

Several relief fragments from outside of the Swāt Valley dating from roughly after the second century CE present the same dance movement. For example, a relief panel of unknown provenance depicts a musician and a dancer under an elaborate pavilion (Figure 9). The courtly setting of the dance can be inferred based on the architectural elements and the relief may be related to scenes of Siddhārtha’s sensual palace life.21 Moreover, the performance occurs in front of an audience that is also part of the figural space. The presence of well-dressed female figures observing the dance from their balconies further emphasizes that the dance was performed for members of the royal palace. When compared with Figure 7, only a few negligible differences such as the dancer’s gender and musical instrument emerge. Despite these differences between Figure 7 and Figure 9, the dance remains strikingly identical. Their similarity suggests that artists deliberately used the same iconographic conventions to visually depict dance over a long period of time.

Figure 9.

Female dancer accompanied by a female musician within an elaborate pavilion, provenance unknown (c. 2nd–3rd century CE). Musée National des Arts Asiatiques—Guimet, Paris, France. Source: Author.

The other five reliefs from Butkara I dated roughly between the second and third century CE take up the same movement, using limited variations, to depict dance. Apart from the gender and clothing of the figures, little to no difference can be identified in the arrangement of the limbs and gestures from a technical perspective. For instance, a relief panel divided into two registers depicts a dance in one of them.22 The two registers likely depict two distinct stories from the Buddha’s biography; however, the present state of the relief only allows for a tentative identification. On the upper register, figures stand around an enthroned mound in veneration. We can suggest that the mound represents the relics of the Buddha and is perhaps related to the events after the mahāparinirvāṇa. On the bottom register, a variation of the Indic dance is depicted. On the left, a seated royal couple watches female musicians and a dancer perform. This scene can be favorably identified as courtly entertainment happening in Siddhārtha’s palace. The dancer, depicted on the right, is viewed only from the back and is wearing a pleated lower garment. Based on the perspective of the scene, the dancer faces her audience, the royal couple. Despite the poor condition of the relief, we can reconstruct some aspects of the dance movement. She is depicted with her left leg slightly raised above the ground, and the position of her right shoulder suggests that her right hand was raised above her head. A strikingly similar movement occurs on a relief in which the Buddha is welcomed by a group of musicians and a dancer. Based on its stylistic and iconographic features, the relief likely comes from the Swāt Valley and can be dated to the first century CE (Figure 10). At the center of the relief, a male figure wearing a pleated lower garment performs the same dance movement found in the aforementioned relief from Butkara I. Moreover, the perspectives are also identical; both dancers are turned away from the viewer.

Figure 10.

A dancer and musicians welcome the Buddha (c. 1st century CE). Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin, Museum für Asiatische Kunst, Berlin, Germany. Source: Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin, Museum für Asiatische Kunst (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0).

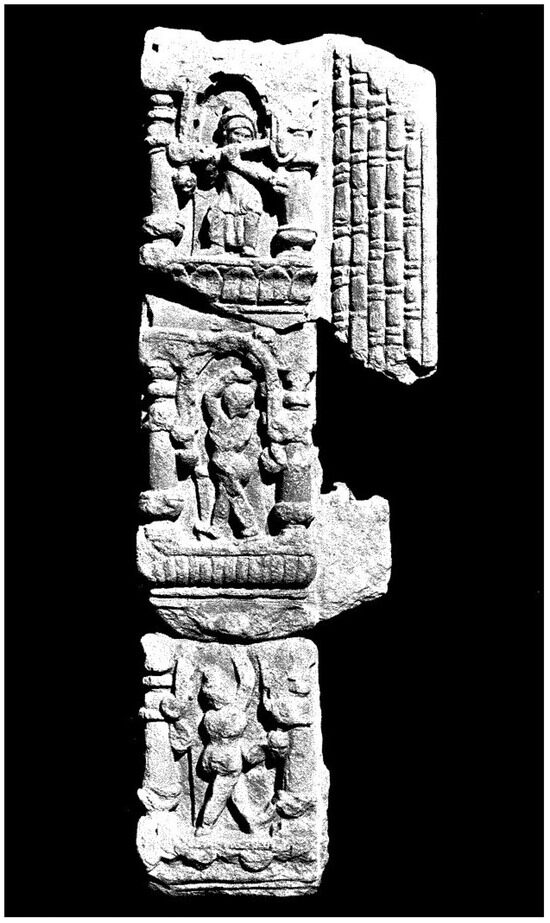

The repetitive iconography of dance can be further illustrated based on other reliefs from Butkara I such as a door jamb relief.23 In its present state, the relief preserves three pairs of figures in different registers. In the middle of the fragment, a pair of dancers perform within an elaborate architectural setting. The pair comprises a poorly preserved male figure with a half-wrapped mantle and a female dancer wearing a pleated lower garment and long earrings. The female dancer’s right hand is raised above her head and her upper body is arched by leaning towards the left. Her left hand is held close to the body. Her lower limbs are also carefully arranged, and her feet are crossed to further accentuate the gracefulness of her movement.

The variations of s this dance are numerous, for example, a door jamb relief which depicts two dancing figures from Butkara I (Figure 11). The relief is divided into three registers. A female figure plays a long flute on the upper register as two female figures perform the same dance in two consecutive registers. Despite the difference in perspective, the leg and arm positions seem to be derived from the Indic dance. To explain this, let us look closely at the actions performed within both registers. The dance, read from top to bottom, is executed by the right side followed by the left side. It is identical and the only difference between the two registers is the side of the limbs that are activated. The two figures have their feet crossed and one of their hands is raised above their head.

Figure 11.

Musician and two dancers in separate registers from Butkara I (c. 2nd century CE). Museo della Civiltà Romana, Rome, Italy. Source: Faccenna, 1962–1964, Pl. CDXCVIII (Inv. No. 4258).

The presence of the same dance in two consecutive registerssuggests some effort was made by the artists to depict a sequence. Repeating the same dance starting with the right side and then followed by the left creates the impression of bilateral symmetry. By representing it side by side, the visual language emphasizes the continuous yet uniform actions of the figures.24 In comparison, this symmetry is also highlighted by the two dancers in Figure 3, who execute the same movement on either side of the seated nāgarāja. Such representations are particularly interesting and, as in the case of Butkara I relief, reveal the existence of multiple perspectives of the same dance on smaller decorative figures.

The role of dance as a form of entertainment is evident, but why does dance appear as part of decorations? Buddhist texts identify dance as part of festivals organized to commemorate important events in the Buddha’s biographies.25 Already in the biographical texts, the use of dance to venerate the Buddha shows a blueprint for how it may have become an important element of relic rituals. Following the Buddha’s mahāparinirvāṇa, festivities (mahas) for his relics occurred and the Mallas performed sarīrapūjā26 with dance, song, music, garlands, and perfumes.27 Once his relics were interred within a stūpa, devotees were encouraged to perform similar acts of reverence and gain spiritual merit.28 The visual representation of such dances performed by the Mallas around the Buddha’s relics can also be found in Bhārhut (Figure 12). The relief uses the visual conventions for dance that we have already examined in Gandhāran art. Female figures, presumably belonging to the Malla clan dance and perform music in front of elephants transporting the Buddha’s relics. The dancers and musicians can be seen as part of an elaborate procession organized around the first distribution of relics following the Buddha’s funeral.

Figure 12.

Female figures dancing alongside the procession of relics on elephants from Bhārhut stūpa (c. 2nd–1st century BCE). National Museum, New Delhi, India. Source: O. Bopearachchi.

While images show us dance, the texts usually do not describe the dance performed by the devotees. However, they repeatedly mention it as an activity related to lay devotees during festivals. In one such festival described in the Avadānaśataka, singing and dancing were so enthusiastically conducted by the devotees that the stūpa was covered by dust after the festival and required further cleaning.29 Our Gandhāran reliefs such as Figure 7 could speak of the joyous and uplifting mood associated with such passionate performances. In light of these literary descriptions, if we consider that Buddhist sites were locations for veneration and performances, figures under arches and other architectural spaces may refer to dance as an offering albeit in a highly idealized manner. Similar to figures making offerings such as lamps and flowers, the male performers in Figure 7 and Figure 11, for instance can be viewed as making an offering of their music and dance. Through their performances, figures in stone venerate the Buddha and his relics perpetually and imbue the sacred area with a festive ambiance.

The use of such evocative festive imagery within the sacred area may also be considered as part of the broader communicative strategy used by the saṃgha. Pagel’s study of Buddhist texts such as avadānas has convincingly demonstrated that well-organized song, dance and theatrical performances as part of Buddhist festivals were also exploited for commercial reasons.30 Festivals were used as a tool to strengthen the ties between the lay and monastic communities through merriment and economic exchanges. Their success was determined by their ability to attract crowds which are usually described in the range of ‘several hundred thousand’. Merchants used the opportunity provided by the festivals to sell their goods to the gathering. Some of the goods sold in the festival markets and the resulting profit, may very well have been donated to the saṃgha. In these cases, texts emphasize the religious and commercial opportunities created by festivals that could be exploited by the saṃgha to enrich itself. Viewing our images in the light of these descriptions of festivals, one cannot help but suspect that the reliefs depicting dance recalled the substantial religious and commercial interest of the broader community that viewed them. Dance imagery in this context could have acted as a concise visual reminder of the opportunities for merry-making and merit-making created by the festivals.

3. Visual Convention of Dance at Kizil Cave 83

Even though we cannot definitively connect the dance movements depicted in Gandhāran art with contemporary praxis, other related evidence shows that the iconographic and stylistic conventions related to dance resonated within a wide geographical and cultural milieu. One such evidence comes in the form of a wall painting depicting a dance performance and found in Kizil Cave 83, the Treasure Cave or Schatzhöhle C. The square cave with a doomed ceiling is part of a compact group of grottos comprising Caves 82, 83, 84 and 85. The caves derive their name from a treasure found in a deep pit.31 Caves 83 and 84 possess paintings of the Sonderstil or Special Style due to the delicate contours, expression and slit eyes of the figures.32 This style closely follows Indic painting traditions and can be dated to the early development of the site, around the fourth century CE. The paintings also provide a consistent overlap during the period in which Buddhist activities in Gandhāra continued to develop. Keeping in mind the active role of Gandhāra and Kuča within the early trade routes connecting Central Asia and the Indian Subcontinent, it is not surprising to see the same dance depicted at Kizil in Cave 83.33

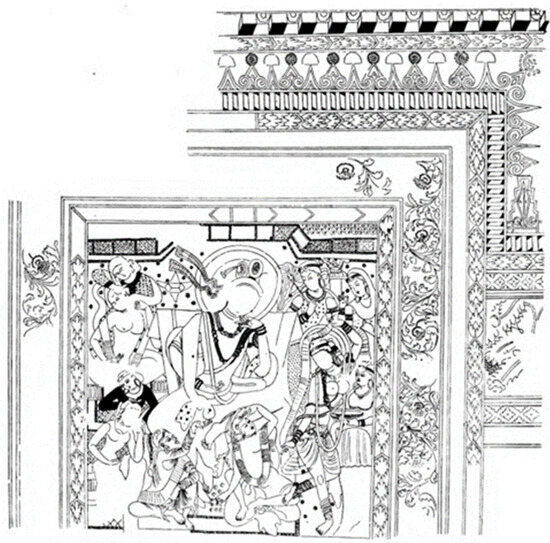

The domed ceiling of Cave 83 was destroyed, and the paintings on the side walls were poorly preserved by the time of Albert Grünwedel’s expeditions in 1906. The most well-preserved painting was on the back wall, and it depicts a dance (Figure 13). The painting, commonly interpreted as the legend of King Rudrāyaṇa, is dominated by an enthroned royal figure who watches a female dancer. The story is present in the Divyāvadāna or Divine Stories, a compendium of Indian Buddhist stories in Sanskrit that were compiled as early as the first century until the eighth century CE.34 The popularity and influential nature of individual āvadānas amongst Buddhist communities in various parts of the subcontinent is also attested by their representations in art. Moreover, the āvadānas were also included in the Mūlasarvāstivādavinaya, a Buddhist school that flourished in the Indic northwest during the first centuries CE.

Figure 13.

Wall painting depicting the dance of queen Candraprabhā, from Cave 83 (Treasure Cave C) at Kizil (c. 4th century CE). Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin, Museum für Asiatische Kunst, Berlin, Germany. Source: Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin, Museum für Asiatische Kunst (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0).

For the present study, a general synopsis of the Rudrāyaṇa-avadāna is sufficient. This avadāna consists of connected sub-stories that recount several events related to King Rudrāyaṇa ruling the great city of Roruka with his favorite queen Candraprabhā, his son Śikhaṇḍin and his chief ministers. It starts with the friendship between Rudrāyaṇa and Bimbisara in which the latter sends the former an image of the Buddha. These events are followed by Rudrāyaṇa allowing his harem women to listen to dharma talks. Every day, the dharma talks were delivered for an unknown period. One day, when the King expertly played the veena while the Queen danced, he saw a sign that foretold the imminent death of Candraprabhā. Upon hearing the signs, Candraprabhā became a bhikṣuṇī and was born in the Cāturmahārājika (Four Great Kings) heaven. After some important religious breakthroughs, she showed her divine self to the King and he decided to renounce everything including his kingdom to his son. The avadāna continues with several events related to their son Śikhaṇḍin and ends with a moral lesson against evil.

For the identification of the painting in Cave 83, one of the most important moments of the story with the Queen Candraprabhā dancing in front of the King is persuasive. Under an elaborate architectural frame often related to decorative motifs in Roman art, King Rudrāyaṇa watches as Candraprabhā dances. Several courtiers and well-dressed women surrounding the royal couple also watch the performance. The painting likely shows us the moment in which the King saw signs foretelling the Queen’s imminent death. The bodily posture of Candraprabhā is depicted in a type of tribhaṅga that we have already come across in Gandhāra art. This posture lends the body a certain flexibility and emphasizes her movement. Her left leg is bent at the knee and is lifted as it is about to be placed behind her right leg. Her left hand is also raised above her head. Her body is curved toward the right and her head is bent down. Within her palms, she holds a long garland that is undulated as she performs her dance. Her lower body is covered by a rich, transparent, diaphanous garment that further amplifies her dance. The texture of the garment also provides a glimpse of her bejeweled girdle clasped around her hip. Besides the girdle, she wears many ornaments including bracelets, earrings, anklets, and necklaces, all of them fitting for a dancing Queen in the palace.

The dance in the Kizil painting finds close parallels with dancing female figures in Gandhāran art, for example, with Figure 14. On this relief, we are confronted with a similar movement with little variation. A female figure, who is partially preserved, is depicted with an arm extended along the length of the body and another arched above her head. Despite the damage to the surface, we can trace that the figure likely held a long garland between her hands. Moreover, the lower limb movement is not fully preserved. However, based on the painting and other representations of dance in Gandhāran art, we can suggest that the dancer’s leg movements were derived from conventional imagery and so, her feet were likely crossed. She performs this dance under a pavilion supported by a Gandhāran-Corinthian column and for an audience. Besides the iconographic conventions of dance, the architectural context and the elaborately dressed figures surrounding the dancer reveal that we are looking at a performance at the court, perhaps within the palace of Siddhārtha.35

Figure 14.

Female dancer accompanied by other female figures, provenance unknown (c. 2nd–3rd century CE). Musée National des Arts Asiatiques—Guimet, Paris, France. Source: Author.

In Gandhāra and Kizil, we find the Indic dance executed within the luxurious courtly setting. Whether it was Siddhārtha’s splendid palace or King Rudrāyaṇa’s court, both the stone reliefs and the mural painting present strikingly similar bodily posture in association with this dance. Based on their similarity, we can suggest that artists in Kizil relied on a popular iconographic convention to represent dance. They may have looked for an existing iconographic model that was already established in Gandharan art within the courtly context to represent the dance of Queen Candraprabhā. Thus, the iconographic conventions typically associated with courtly dance performances in both Gandhāra and Kuča suggest, in my opinion, that some elements of the visual language related to dance were likely shared by artists over a large geographic and chronological zone. They reveal that dance imagery conformed to artistic conventions and the dancing figures were symbols for dance in general rather than an illustration of a particular dance performance. Based on the striking uniformity between Cave 83 and Gandhāran reliefs, we can identify the presence of similar conventions, and add dance imagery to the growing list of similarities between the two regions.36

4. Preliminary Conclusions

Our knowledge of dance in Gandhāra relies entirely on the iconographic record. Based on the images alone, I would not dare to conclude that dances in art were observable in reality since we lack any other type of evidence to support such a claim. However, the analysis of a specific type of dance, here associated with Indic conventions, allows us to arrive at some preliminary conclusions. The repetition of similar dance movements in visual art over four centuries and within different regions in Gandhāra and elsewhere, in my opinion, suggests that artists used specific visual conventions to represent dance. This suggestion is further strengthened by the fact that the artists focused on a limited combination of arm and leg movements to convey dancing. These movements, I suspect, became topical and began to be associated with dance as a general category of performance in visual art. The representation of such movements were likely visual cues used to evoke the world of dance performances in general, rather than a particular event, in the mind of the viewers. The devotee, as an audience familiar with the visual language and perhaps influenced by contemporary experiences, would have understood these ‘petrified’ dances despite the limited recombination of movements.

The dance imagery commonly used in Gandhāran art may have also influenced the artists at Kizil, as suggested by the mural painting in Cave 83. The painting depicting Candraprabhā’s dance reveals that the artistic conventions associated with dance in the Indian subcontinent may have also been utilised in the Tarim Basin. The use of the Indic dance at Kizil sheds light on the constructed nature of dance imagery in both sculptures and mural paintings in the early centuries CE. Their striking similarity may have stemmed from the fact that dance postures in art were part of prescribed elements, lending dance imagery a level of uniformity within a wide geographical area. The artists at Kizil may have adopted the pre-existing elements associated with dance and deployed them to enhance the courtly setting of the narrative. In the case of the painting in Cave 83, the choice made by the artists was likely facilitated by recombining a limited set of arm and leg movements that were already consistently associated with Siddhārtha’s palace in Gandhāran art.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Acknowledgments

This study was conducted as part of my École française d’Extrême-Orient (EFEO) postdoctoral project titled ‘Music and Dance in Gandhāran Art’ over the course of 10 months in 2023. I am extremely grateful to the Musée national des arts asiatiques—Guimet (Paris) and Nicolas Engel, curator of the department of Afghanistan, for allowing me access to the collection of Gandhāran reliefs and the fruitful discussions that followed. I am also honored to have the opportunity to thank several colleagues who positively impacted my postdoctoral research: Charlotte Schmid, Evelise Bruneau, Zixiao Zong, Vladyslav Sydorov, and Adam Wijker. Many thanks also to the two anonymous reviewers of this article for their suggestions. All mistakes are my own.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Later texts such as the Abhinavabhāratī by Abhinavagupta provide a wealth of information regarding Sanskrit drama and dance in Kashmir around the 11th century CE. As this is not relevant to our present context, I do not discuss this text. However, an important analysis of this text alongside the Nāṭyaśāstra can be found in (Ganser 2022), ‘Theatre and Its Other’. |

| 2 | (Iyer 1993), ‘A fresh look at nṛtta’. |

| 3 | Nāṭyaśāstra 4.30cd. The relationship between movements of dance and emotions as conceived within bhāvas and rasa is addressed in (Ganser 2020), ‘Incomplete mimesis’. |

| 4 | The dance is associated with the Śiva tāṇḍava, a cosmic dance creating a cycle of birth and rebirth. Dance also requires symmetry and balance that can be associated with practices of yoga ((Ganser 2023) ‘Dance as Yoga’). For the connection of different temple sculptures and karaṇas, see (Vatsyayan 1977), ‘Indian Classical Dance’, 106–154. |

| 5 | (Vatsyayan 1977), ‘Indian Classical Dance’, 5. |

| 6 | (Subrahmanyam 2003), ‘Karaṇas: Common Dance Codes of India and Indonesia’. A reconstruction of the karaṇas was also made by Padma Subrahmanyam and is available at https://archive.org/details/dli.pb.natyashastra.1/Natyashastra.1_1.m4v (accessed on 12 July 2023). |

| 7 | The numerous possibilities make it very challenging to identify the exact karaṇas, if they were intended to be represented in art. This issue is further aggravated when the objective of the visual program was not to represent the karaṇas systematically. This is the case in Hoysaleswara Temple in Halebid, Karnataka. The interpretation of these dance sculptures can be found in (Tosato 2017) ‘The Voice of the Sculptures’. |

| 8 | The origins of the visual language of dance, at this stage, cannot be traced to textual treatises on the theme such as the karaṇas of the Nāṭyaśāstra. However, this does not mean that dance and its associated arts such as theater were not, to some extent, codified. Some traces of codification in a text, which is now lost, are mentioned by the grammarian Pāṇini and was called the Naṭasūtras or the Aphorisms for Actors (Aṣṭādhyāyī IV.3.110). The famed Sanskrit grammarian is considered to have been born in Gandhāra, in Śalātura (near Peshawar, Pakistan), and likely lived in the region around the fifth century BCE. This presents the possibility that some type of codified performance existed within our context and was known to the author of the text. For an overview of theater in Gandhāra, see (Brancaccio and Liu 2009), ‘Dionysus and drama’. |

| 9 | One of the main problems of studying dance sculptures is that dance like music, as a performance art, is rendered through different mediums of other arts such as images and texts. On the other hand, musical instruments has been studied in some detail and notable works on this theme are (Goldman 1978), ‘Parthians at Gandhāra’; (Nettl 1991), ‘But What Is the Music?’; and (Lo Muzio 1989), ‘Classificazione degli strumenti musicali’. |

| 10 | Western iconographies in the representation of dance are examined in (Lo Muzio 2019), ‘Persian ‘Snap’. |

| 11 | Siddhārtha cuts off his hair and removes his turban before achieving enlightenment as they were a symbol of his former attachments as a prince. According to (Lüders 1963), ‘Bharhut Inscriptions’, p. 94, based on texts such as the Nidānakathā, Mahāvastu, Lalitavistara, and the Mūlasarvāstivādavinaya, it is the anniversary of this event that is celebrated by the thirty-three gods heaven as the festival of the hair-lock. |

| 12 | The formulaic representation of limb and arm movements and their combinations in Indian art is also the focus of (Fukuroi 2008), ‘Dancing Images in the Gōpuras’. |

| 13 | Similarly, dancing along with song and music as an entertainment occurs in Śuddhodana and Māyā’s court (Mahāvastu I.99), and later in Siddhārtha’s Palace (Lalitavistara XII. 33; Buddhacarita II. 30) and indeed, music and dance were used to unsuccessfully prevent the Great Renunciation (Lalitavistara XIV.1). In the Yichu pusa benqi jing 異出菩薩本起經 (Sūtra [of] the great renunciation; Sanskrit: Abhiniṣkramaṇa-sūtra), translated by Nie Daozhen 聶道真, the dancing girls were put to sleep during the renunciation by the four heavenly kings (T. no. 188. 619b-c). It is a customary part of the royal court in Mahājanaka-jātaka (539) and the nāgā court in Vidhurapaṇḍita-jātaka (545) and also appears as form of seduction in the Cullapalobhana-jātaka (263). |

| 14 | For a comprehensive introduction to the local dynasties, the Apracarājas and the Oḍirājas ruling Bajaur and Swāt respectively, see (Salomon 2007), ‘Dynastic and Institutional Connections’. |

| 15 | (Faccenna 1980–1981), ‘Butkara I (Swat, Pakistan) 1956–1962’. |

| 16 | (Filigenzi et al. 2003), ‘At the Origin of Gandhāran Art’. |

| 17 | (Filigenzi 2019) ‘Forms, Models and Concepts’. |

| 18 | (Brancaccio 2007), ‘Gateways to the Buddha’. |

| 19 | It is not farfetched to suggest that the elaborately styled musician and dancer, richly draped and wearing turbans and heavy jewelry may have been part of the performative imagery interconnected with the aristocratic habitus of the court. Indeed, the interaction between art and the court within Gandhāra using, amongst others, the representation of dance and musical performances has already been argued by (Galli 2011), ‘Hellenistic Court Imagery’ but is limited to the Graeco-Roman elements. Needless to say, the local kingdoms were substantially Indic. |

| 20 | It should be noted that the iconographic conventions related to clothing and jewelry are also part of donors and devotee figures in the Swāt Valley. The iconographic conventions of the figure and the lack of individualizing features present the possibility that they are donors (or devotees). For more on this analytical category see (Lakshminarayanan 2023), ‘Towards Investigating the Representation of Gandhāran Female Donors’. |

| 21 | For a short description of court performances see (Mehta 1999), ‘Sanskrit Play Production in Ancient India’, 286. |

| 22 | (Faccenna 1962–1964), ‘Sculptures from the Sacred Area’, Pl. CCCXCVII (Inv. No. 87). |

| 23 | Ibid, Pl. CCCLI (Inv. No. 2871). |

| 24 | This is also an element of modern Indian classical dances such as Bharatanatyam and Odissi. However, questions on their connection to historical forms of dance in India has been raised in (Ganser 2011), ‘Thinking Dance Literature’. |

| 25 | (Schopen 2014), ‘Celebrating Odd Moments’. |

| 26 | This was the funeral to worship the sarīra (body) of the Buddha. Prior to the Buddha’s nirvana, he instructed Ananda, his foremost disciple, not to be preoccupied with the sarīrapūjā and to permit the lay followers to perform them. Scholars have misunderstood this to mean that bhikṣus were entirely forbidden from performing sarīrapūjā and that such worship belonged solely in the realm of lay followers. Schopen convincingly demonstrated that this passage did not relate to relic worship and that sarīrapūjā meant the funeral ceremonies that were performed before the cremation of the body. Over time, the term sarīrapūjā began to acquire the meaning of relic worship and was no longer understood as a funeral ceremony. For more on this issue, see (Schopen 1997), ‘Bones, Stones, and Buddhist Monks’, p. 100, and (Werner 2013), ‘The Place of Relic Worship in Buddhism’. |

| 27 | Dīgha Nikāya XVI. |

| 28 | In the vinayas, the focus is commonly on the behavior of monks and nuns and not on the components of the celebration. The references and the context in which prohibitions occur are provided in (Liu 2018), ‘Reciting, Chanting, and Singing’. References to worship by performances including dance occur in the Mahāvastu (I. 268; I. 304; II. 17). Much later, in the Mahāvaṃsa, King Bhātikābhaya offered the stūpa, flowers, perfumes, lamps, water, gold jewelry of impressive sizes and plays, and dances as donations (XXXIV. 60). Similarly, his brother ascended to the throne after him and built a stūpa to which he provided various gifts to a stūpa including singing, music and dancing (XXXIV. 78). Presumably, this meant that he hired musicians, singers and dancers for the stūpa. A parallel practice in Central Asia can be confirmed by manuscript fragments found during Paul Pelliot’s excavations in 1970 in Duldur-akhur. The documents belonged to the Samantatir monastery and detail the incomes and expenses of a stūpa in coins. The fragments list the expenses of the stūpa such as perfumes and wheat milling and also include musicians. For a detailed description of these expenses, see (Ching 2014), ‘Perfumes in Ancient Kucha’. At the same time, the texts also exalt people who abstain from dance, for example, in the Mahāvastu (I. 326) and the Divyāvadāna (XXVIII. 10–20) in relation to the potter Ghaṭikāra and Vītaśoka, respectively, and in echo of Siddhārtha’s own non-enjoyment of music and dance prior to the renunciation (Mahāvastu II. 145). |

| 29 | Avadānaśataka I. 361.15f in (Speyer 1906–1909), ‘Avadānaçataka’. |

| 30 | (Pagel 2007), ‘Stūpa Festivals in Buddhist Narrative Literature’. A dance performance by yavanikās (foreign women?) also occurs as part of a post-birth ceremony in a Gāndhārī avadāna but it is likely not associated with the Buddhist cult. A translation and analysis of this text is available in (Falk and Steinbrückner 2022), ‘Avadāna Episodes’, pp. 50–51. |

| 31 | (Grünwedel 1920), Altbuddhistische Kultstätten in Chinesisch-Turkistan, p. 100 |

| 32 | (Waldschmidt 1933), ‘Über Den Stil der Wandgemälde’. |

| 33 | Some nuanced comparisons between Gandhāran art and paintings from Kuča are (Santoro 2004), ‘Gandhara and Kizil: The Buddha’s Life in the Stairs Cave’ and (Zin 2012), ‘Buddhist Narrative Depictions in Andhra, Gandhara and Kucha’. |

| 34 | (Rotman 2017), ‘Divine Stories’, pp. 287–341 |

| 35 | This last remark cannot be fully substantiated since this part of the relief is entirely missing. However, until a better interpretation can be arrived at, the courtly setting of this performance remains a valid hypothesis. |

| 36 | The close relationship between Gandhāran art and Kizil paintings in their earliest phase strengthens this possibility. For studies on this theme see (Santoro 2004), ‘Gandhāra and Kizil’ and (Lakshminarayanan 2021), ‘Globalization and Gandhāra Art’. |

References

- Brancaccio, Pia. 2007. Gateways to the Buddha: Figures under Arches in Early Gandhāran Art. In Gandharan Buddhism: Archaeology, Art, and Texts. Edited by Kurt Behrendt and Pia Brancaccio. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brancaccio, Pia, and Xinru Liu. 2009. Dionysus and drama in the Buddhist art of Gandhara. Journal of Global History 4: 219–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ching, Chao-Jung. 2014. Perfumes in Ancient Kucha: On the Word tune attested in Kuchean monastic accounts. Tocharian and Indo-European Studies 15: 39–52. [Google Scholar]

- Faccenna, Domenico. 1962–1964. Sculptures from the Sacred Area of Butkara I (Swat, Pakistan). Rome: Instituto Poligrafico Dello Stato, 2 vols. [Google Scholar]

- Faccenna, Domenico. 1980–1981. Butkara I (Swāt, Pakistan) 1956–1962. Reports and Memoirs. Rome: IsMEO. [Google Scholar]

- Falk, Harry, and Elisabeth Steinbrückner. 2022. Avadāna Episodes (Texts from the Split Collection 5). Annual Report of the International Research Institute for Advanced Buddhology at Soka University 25: 21–60. [Google Scholar]

- Filigenzi, Anna. 2019. Forms, Models and Concepts: Regionalism and ‘Globalism’ in Gandhāran Visual Culture. In Indology’s Pulse Arts in Context Essays Presented to Doris Meth Srinivasan in Admiration of Her Scholarly Research. Edited by Corinna Wessels-Mevissen and Gerd J. R. Mevissen. New Delhi: Aryan Books International. [Google Scholar]

- Filigenzi, Anna, Domenico Faccenna, and Pierfrancesco Callieri. 2003. At the Origin of Gandharan Art. The Contribution of the Isiao Italian Archaeological Mission in the Swat Valley Pakistan. Ancient Civilizations from Scythia to Siberia 9: 277–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuroi, Yuko. 2008. Dancing Images in the Gōpuras: A New Perspective on Dance Sculptures in South Indian Temples. Senri Ethnological Studies 71: 255–79. [Google Scholar]

- Galli, Marco. 2011. Hellenistic Court Imagery in the Early Buddhist Art of Gandhara. Ancient Cilvilizations from Scythia to Siberia 17: 279–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganser, Elisa. 2011. Thinking dance literature from Bharata to Bharatanatyam. Rivista Degli Studi Orientali 84: 145–61. [Google Scholar]

- Ganser, Elisa. 2020. Incomplete mimesis, or when Indian dance started to narrate stories. Asiatische Studien—Études Asiatiques 74: 349–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganser, Elisa. 2022. Theatre and Its Other. Abhinavagupta on Dance and Dramatic Acting. Gonda Indological Studies 23. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Ganser, Elisa. 2023. Dance as Yoga: Ritual Offering and Imitation Dei in the Physical Practices of Classical Indian Theatre. Journal of Yoga Studies 4: 137–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman, Bernard. 1978. Parthians at Gandhāra. East and West 28: 189–202. [Google Scholar]

- Grünwedel, Albert. 1920. Altbuddhistische Kultstätten in Chinesisch-Turkistan. Berlin: Otto Elsner Verlagsgesekkschaft. [Google Scholar]

- Iyer, Alessandra. 1993. A Fresh Look at Nṛtta (Or Nṛtta: Steps in the Dark?). Dance Research: The Journal of the Society for Dance Research 11: 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakshminarayanan, Ashwini. 2021. Globalization and Gandhāra Art. In Globalization and Transculturality from Antiquity to the Pre-Modern World. Edited by Serena Autiero and Mathew Cobb. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Lakshminarayanan, Ashwini. 2023. Towards Investigating the Representation of Gandhāran Female Donors. Arts Asiatiques 78: 5–21. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Cuilan. 2018. Reciting, Chanting, and Singing: The Codification of Vocal Music in Buddhist Canon Law. Journal of Indian Philosophy 46: 713–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Muzio, Ciro. 1989. Classificazione degli strumenti musicali raffigurati nell’arte Gandhārica. Rivista Degli Studi Orientali 63: 257–84. [Google Scholar]

- Lo Muzio, Ciro. 2019. Persian ‘Snap’: Iranian Dancers in Gandhāra. In The Music Road. Coherence and Diversity in Music from the Mediterranean to India (Proceedings of the British Academy). Edited by Reinhard Strohm. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lüders, Heinrich. 1963. Bharhut Inscriptions. Corpus Incriptionum Indicarum 2.2. Ootacamund: Government Epigraphist for India. [Google Scholar]

- Mehta, Tarla. 1999. Sanskrit Play Production in Ancient India. New Delhi: Motilal Banrsidass Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Nettl, Bruno. 1991. But What Is the Music? Musings on the Musicians at Buner. Bulletin of the Asia Institute 5: 27–33. [Google Scholar]

- Pagel, Urich. 2007. Stūpa festivals in Buddhist Narrative Literature. In Indica et Tibetica. Festschrift für Michael Hahn Zum 65. Geburtstag von Freunden und Schülern überreicht. Edited by Konrad Klaus and Jens-Uwe Hartmann. Vienna: Universität Wien. [Google Scholar]

- Rotman, Andy. 2017. Divine Stories Divyāvadāna. Somerville: Wisdom Publications, Part 2. [Google Scholar]

- Salomon, Richard. 2007. Dynastic and institutional connections in the pre-and early Kusana period: New manuscript and epigraphic evidence. In On the Cusp of an Era: Art in the Pre-Kuṣāṇa World. Edited by Doris Srinivasan. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Santoro, Arcangela. 2004. Gandhara and Kizil: The Buddha’s Life in the Stairs Cave. Rivista Degli Studi Orientali 77: 115–33. [Google Scholar]

- Schopen, Gregory. 1997. Bones, Stones, and Buddhist Monks: Collected Papers on the Archaeology, Epigraphy, and Texts of Monastic Buddhism in India. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schopen, Gregory. 2014. Celebrating Odd Moments The Biography of the Buddha in Some Mūlasarvāstivādin Cycles of Religious Festivals. In Buddhist Nuns, Monks, and Other Worldly Matters Recent Papers on Monastic Buddhism in India. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. [Google Scholar]

- Speyer, Jacob Samuel. 1906–1909. Avadānaçataka: A century of edifying tales belonging to the Hīnayāna. St. Petersburg: Imperial Academy of Sciences, 3 vols. [Google Scholar]

- Subrahmanyam, Padma. 2003. Karaṇas: Common Dance Codes of India and Indonesia. Chennai: Nrithyodaya. [Google Scholar]

- Tosato, Anna. 2017. The Voice of the Sculptures: How the ‘Language of Dance’ Can Be Used to Interpret Temple Sculptures. An Example from the Hoysaḷeśvara Temple at Haḷebīd. Cracow Indological Studies 19: 79–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vatsyayan, Kapila. 1977. Indian Classical Dance, 2nd ed. New Delhi: Ministry of Information and Broadcasting. [Google Scholar]

- Waldschmidt, Ernst. 1933. Über Den Stil der Wandgemälde. In Die Buddhistische Spätantike in Mittelasien = Ergebnisse Der Kgl. Preussischen Turfan Expeditionen, VII. Edited by Albert von Le Coq and Ernst Waldschmidt. Berlin: Dietrich Reimer. [Google Scholar]

- Werner, Karel. 2013. The Place of Relic Worship in Buddhism: An Unresolved Controversy? Buddhist Studies Review 30: 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zin, Monika. 2012. Buddhist Narrative Depictions in Andhra, Gandhara and Kucha—Similarities and Differences That Favour a Theory about a Lost ‘Gandharan School of Paintings. In Buddhism and Art in Gandhara and Kucha. Buddhist Culture along the Silk Road. Edited by Akira Miyaji. Kyoto: Ryukoku University. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).