Adab al-Qāḍi: Shared Juridical Virtues of Judaic and Islamic Leadership

Abstract

1. Exposé—Introduction to the Books on Judges’ Duties in Geonic Literature

2. Geniza Fragments and the Literature on Judges’ Duties

3. The Genre of Adab al-Qāḍī

4. Kalam Theology in Legal Literature

5. Discoveries of the Books Belonging to the Jewish Branch of the Genre Etiquette for Judgeship

- Kitāb lawāzim al-ḥukkām (“Book of the judges’ duties”), Rav Samuel ibn Ḥofni Geon Sura (d. 1013)

- 2.

- Kitāb Adab al-qaḍāʾ (“Book of good manner for legal procedure”), Rav Hai Gaon Pumbedita (939–1038)

- 3.

- Faṣl fī ādāb al-dayyanin (“Chapter on the judges’ good manners”), Rav Yosef, son of Yehuda Ibn Aknin al-Barceloni

6. Ethical Character and Adjudicative Process

7. Socio-Political Context and Judicial Integrity

8. Comparative Insights and Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

וקד ג̇מע רבינו שמואל הכהן בן חפני גאון ז"ל פיהם עשר אוצאף: והו אן יכון אלחאכם (1) מן ישראל (2)רגלא (3) עאקלא (4) חרא (5) עאלמא (6) עאדלא (7) עפיפא. ((ידפע)) (8) לא תכון בינה ובין אלמתחאכמיןקראבה מכצוצה, (9) ולא יגר אלי נפסה בחכמה נפעא, (10) ולא ידפע בה ענה צ̇ררא

وقد جمع ربنا شموئل ابن حوفني غاون ز"ل (= عليه السلام) فيهم عشر اوصاف وهو ان يكون الحاكم مناسرائيل رجلا, عاقلا, حرا, عالما, عادلا, عفيفا, لا تكون بينه وبين المتحكمين قرابة مخصوصة ولا يجر الى نفسهبحكمه نفعا ولا يدفع به عنه ضررا.

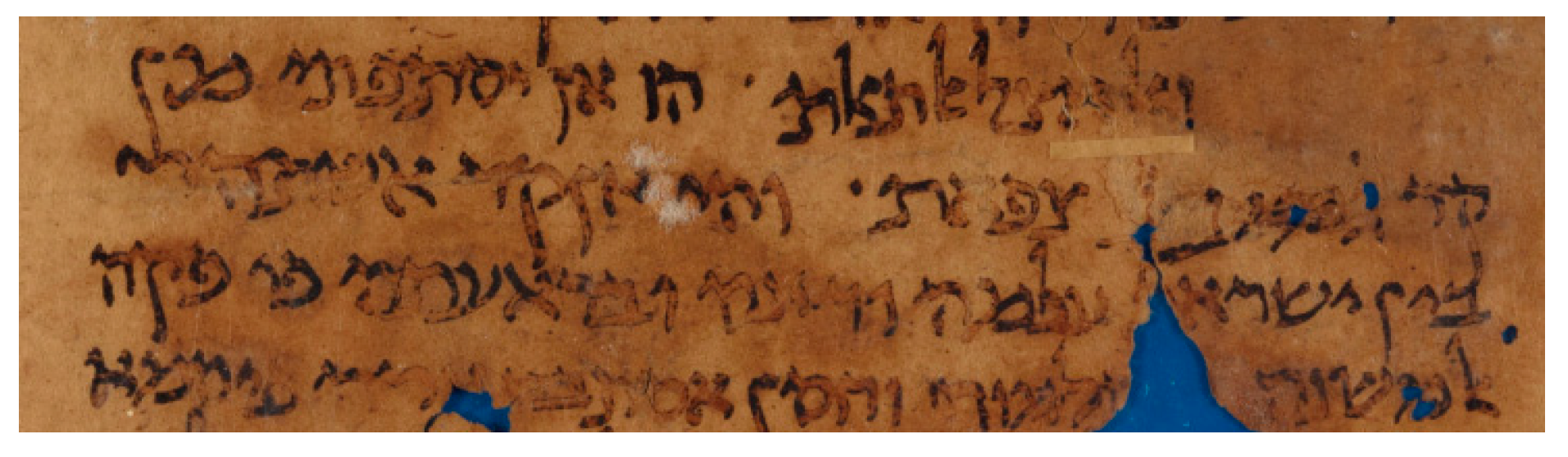

,ואלאצל אלתאלת. הו אן יסתפתי מן קד ג̇מע י צפאת. והי אן קד אשתהר בין ישראל עלמה ודינה ובראעתה פי פקה אלמשנה <ואל>תלמודוחסן אסתכ?<ב?>ארה פיהמא

في صفة القاضي وما يعتبر فيه من شروط: شرائط القضاء عشرة: (1) الاسلام، (2) والحريه، (3) والذكورة، (4)…والتكليف، (5) والعدالة، (6) والبصر، (7) والسمع، (8) والنطق، (9) والكتابة، (10) والعلم بالأحكام الشرعيةوشرط صحة تولية القضاء على مذهب إمامنا رضي الله عنه الاجتهاد المطلق، وهو ان يكون عالماً بالكتاب والسنةوالإجماع، والقياس وأقاويل الناس، ولسان العرب. 21

| 1 | The term “Gaon” stands for the Terminus Technicus Rosh Yeshivat Geon Yaacov, the head of the Babylonian academy. It is relevant because the individual so titled was a spiritual-theological guide for the Diaspora and, for this reason, a halakhic authority as well (Brody 1993, 2013, 2015; Malter 1921, pp. 157–67, 341–51). |

| 2 | See (Ariel 2019). For preliminary remarks, see (Ariel 2017). In my post-doctoral studies, I now concentrate on the comparative legal aspects of this genre and the pursuit of my Habilitationsschrift in the field: The Dawn of Judaeo-Islamic Jurisprudence: Adab al-Qāḍī as a Reconstruction of Comparative Legal History (Bar-Ilan University and the Freie Universität Berlin, forthcoming). |

| 3 | See (Ben-Shammai 2011). It is common to differentiate between this geniza and the misleading term “geniza” that is used mistakenly for Hebrew fragments in Europe; see (Keil 2016, pp. 15–18). Almost all the Geniza fragments that I studied may be viewed at https://fjms.geniza.org/ (accessed on 17 January 2024), except for some fragments of the Mosseri Collection and St. Petersburg (scans are available upon personal request). The Bodleian Library collection—among other collections of Geniza sources at Princeton, Cambridge, and JTS—is now available at http://bav.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/ (accessed on 17 January 2024). |

| 4 | See (Griffel 2011): Kalām is a genre of theological and philosophical literature in Arabic that was actively pursued between the eighth and nineteenth centuries. In its early period, the genre employed a particular type of argumentative techniques and developed a distinct method that is also referred to as kalām. First produced by Muslim authors in Iraq, the genre and its method was also employed by Jewish and to a lesser degree Christian Arab theologians. A practitioner of kalām is known as a mutakallim and, in plural, as mutakallimūn. Often translated as “rationalist theology”, kalām is in Islam among the most important genres of theological literature. |

| 5 | For a preliminary discussion, see (Masud 2007; Schneider 1990; Masud et al. 2006). The translation of the name of the genre is Powers’ (see p. 16) and also, recently, (Rafii 2019). |

| 6 | See Note 2 above. |

| 7 | On complications with this name, see (Libson 1999). For further research, see (Ariel 2023b). |

| 8 | In my forthcoming book, pursuant to my PhD dissertation, and in my aforementioned forthcoming article, I provide the basis for the literary background of this identification. Although it is uncertain whether this fragment is part of Rav Samuel ibn Ḥofni’s book, it is quite evident this kind of literature was available to both professional and lay theologians. In this regard, see (Sklare 2014). |

| 9 | Several bear mentioning here: (a) Kitāb Adab al-qaḍā of Ibn Abi al-Dam (1187–1244); see (Krauss-Sánchez 2010). Accessed July 16, 2018, http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/2213-2139_emc_SIM_01369; (b) Kitāb adab al-qaḍī of al-Khassaf. (c) Regarding al-Mawardi’s contribution to the understanding the theme of Judges’ characteristics, see (Jackson 1996). Further discussion appears in my forthcoming article (n. 4 above). There are also remnants of this genre in the Karaite literature; they will be discussed in an additional paper: “Adab al-Qāḍī–Jurisprudential Genre—Beginnings of a Comparative Case Study” (Ariel 2020a). |

| 10 | See Note 2 above. |

| 11 | Worth mentioning are the extensive Ktiv—The International Collection of Digitized Hebrew Manuscripts (http://web.nli.org.il/sites/nlis/en/manuscript, accessed on 17 January 2024); and Ozar HaḤochma (http://jewishhistory.huji.ac.il/Internetresources/databases_for_jewish_studies.htm, accessed on 17 January 2024), among many other digital tools (e.g., https://bibliothek.univie.ac.at/fb-judaistik/datenbanken.html, accessed on 17 January 2024). |

| 12 | To mention the most central: (Blau 2006; Friedman 2016b) and also dialectal dictionaries: (Piamenta 1990). |

| 13 | For a critical edition that contains this chapter, further legal discussion, and a detailed bibliography, see (Ariel 2023a). |

| 14 | (Halkin 1944), published Greek aphorisms transmitted by Ibn Aknin into Judeo-Arabic. Another chapter on education is provided by (Güdemann 1873). |

| 15 | The staff at the Izhak Ben-Zvi Institute kindly provided a preliminary list, preliminary in the sense of not differentiating among categories. Ordering these materials constituted a substantial part of the work; see Introduction to Ariel, Manuals. |

| 16 | Such comparative studies are rare because the preconditions for pursuing them entail well-integrated interdisciplinary knowledge. Several comparative works bear mentioning here: (Zellentin 2022; Brann 2000; Cohen 2017; Jany 2012; Kaufhold 1984; Libson 1980, 1991, 1996, 1999, 2003; Montgomery 2007; Shahar 2008; Simonsohn 2011; Sinai 2010; Sklare 1996; Stampfer 2008; Stroumsa 2003; Yagur 2017; Yaffe 1981, 1982). For further bibliographical notes, see (Rakover 1975). |

| 17 | Aaron Greenbaum, The Biblical Commentary of Rav Samuel Ben Hofni Gaon According to Geniza Manuscripts, (Jerusalem 1978, p. 57) (with Heb. translation); (Greenbaum 1962). |

| 18 | (Blau 2005; Friedman 2016a) with the meaning:משך ממון מן הקופה or משך ממון על חשבון. |

| 19 | Fragments: CUL T-S.8.236+ T-S 8K 11; (Assaf 1944, 1945). Further discussion in this fragemnts in (Ariel 2020b, 2020c). |

| 20 | d. 643 Hijra (1246). |

| 21 | Ibn Abi AlDam,كتاب ادب القضاء , Beyrouth 1987, pp. 33–36. |

| 22 | The human rational deliberation is expressed with the term Ijtihad. More about this concept and about the shafii development (Schacht and MacDonald 2018). It is to mention, that this term is also connected to Qada, which is also compared to the godly rationality (Campanini 2006). |

| 23 | Ijmāa is the third origin for legal decision in Islam and is based on the agreement of the general Islamic community (Bernand 2018). |

| 24 | In a concrete case the judge will apply Qiyās as a Syllogism or Analogy of the holy scriptures (Tsafrir 2017). |

| 25 | This would be translated as it appears in the lyrical language of the Mussaf prayer for Yom Kippur according to the Ashkenazi rite: ומעורב בדעת עם הבריות (whose disposition is pleasing to his fellow-men). Regarding the Judge as a שליח ציבור (which normally implies Cantor/Ḥazan and literally means the messenger of a congregation in a public prayer, representing the public before God), see (Reiner 2008). For a general discussion on attributes on graves, see (Baumgarten 2018). For further information about databases of this sort, see http://www.steinheim-institut.de/cgi-bin/epidat (accessed on 17 January 2024). |

| 26 | Namely the mad̲h̲āhib. |

| 27 | This is not only visual condition but rather a mental or conceptual capacity. |

| 28 | In the islamic law: adjudication of a certain case based on personal opinion, where there are no further support in Qurʾān or Hadith. |

| 29 | To other options: Sufi meaning of ecstasy or like we find in the Qur’an 65:6 financial ability. In the second case this would be like Mekhilta “baalei Mamon” (Ariel 2023a). |

| 30 | It seems that the meaning of this addition is hierarchical: the good fortunes are more decisive for the appointment than the genealogy. |

References

Primary Sources

al-Khassāf, Aḥmad ibn ʿUmar. 1978. Kitāb Adab al-Qaḍī. Edited by Farḥāt Ziyādah. Cairo: Dār al-Kutub al-ʿIlmiyya.Ibn Abī al-Dam, Ibrāhīm ibn ʿAbdallāh. 1982. Kitāb Adab al-qaḍāʾ. Edited by Muḥammad Muṣṭafā al-Zuhaylī. Damascus: Dār al-Fikr.Ktiv—The International Collection of Digitized Hebrew Manuscripts. Available online: http://web.nli.org.il/sites/nlis/en/manuscript (accessed on 17 January 2024).Geniza Fragments. Available online: https://bibliothek.univie.ac.at/fb-judaistik/datenbanken.html (accessed on 17 January 2024).Geniza Fragments. Available online: https://fjms.geniza.org/ (accessed on 17 January 2024).Geniza Fragments. Mosseri Collection and St. Petersburg (Scans are Available upon Personal Request).Geniza Fragments. The Bodleian Library Collection. Available online: http://bav.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/ (accessed on 17 January 2024).Ozar HaḤochma. Available online: http://jewishhistory.huji.ac.il/Internetresources/databases_for_jewish_studies.htm (accessed on 17 January 2024).Secondary Source

- Abramsohn, Shraga. 1972. Qeta hadash mi-mekhilta de-Rabbi Shimon bar Yohai. Tarbiz 4: 361–72. [Google Scholar]

- Ariel, Neri Y. 2017. Discovery of a Lost Jurisprudential Genre in the Genizah Treasures. Judaica 7: 299–309. [Google Scholar]

- Ariel, Neri Y. 2019. Manuals for Judges ادب القضاة)): A Study of Genizah Fragments of a Judeo-Arabic Monographic Legal Genre. Ph.D. dissertation, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Jerusalem, Israel. [Google Scholar]

- Ariel, Neri Y. 2020a. Adab al-Qāḍī–Jurisprudential Genre—Beginnings of a Comparative Case Study. In Festschrift for the Prof. Joshua Blau Centenary—Proceedings of the 19th SJAS Conference, 1–4 July, Antwerp 2019. Leiden: Brill, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Ariel, Neri Y. 2020b. Ein Fragment aus der Einführung zum »Kittāb Lawāzim al-Ḥukkām« von Rav Shmu’el Ben Ḥofni Gaon. Frankfurter Judaistische Beiträge (FJB) 43: 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Ariel, Neri Y. 2020c. Fußspuren eines gaonäischen Midrasch zu Hiob (32:11) in Samuel b. Ḥofnis neu entdecktem Fragment (CUL T-S Ar. 46.156)—Kitāb lawāzim al-Ḥukkām. JUDAICA: Neue Digitale Folge (JNDF) 1: 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariel, Neri Y. 2023a. Annotated Edition with Commentary of Faṣl fī ādāb al-dayyanin from Ṭibb al-Nufūs by Ibn Aknin. Sefunot 28: 13–89. [Google Scholar]

- Ariel, Neri Y. 2023b. Rav Hai Gaon’s Jurisprudential Monograph Kitāb adab alqaḍā Reconstructed from the Cairo Genizah. Jewish History 37: 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Assaf, Simḥah. 1944. Mi-shayare sifrutam shel ha-geonim. Tarbiz 15: 27–35. [Google Scholar]

- Assaf, Simḥah. 1945. Shelosha sefarim niftahim la-Rav Shemuel b. Ḥofni Gaon—Kittāb Lawazim al-Ḥukkām. Sinai 17: 113–18. [Google Scholar]

- Baumgarten, Elisheva. 2018. Reflections of Everyday Jewish Life: Evidence from Medieval Cemeteries. In Les Vivants et les Morts dans les Sociétés Médiévales: XLVIIIe Congrès de la SHMESP. Paris: Éditions de la Sorbonne, pp. 95–104. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Shammai, Haggai. 2011. Is ‘the Cairo Genizah’ a Proper Name or a Generic Noun? On the Relationship between the Genizot of the Ben Ezra and the Dār Simḥa Synagogues. In From a Sacred Source—Genizah Studies in Honor of Professor Stefan C. Reif. Edited by Siam Bhayro, Ben M. Outhwaite and Geoffrey Khan. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Bernand, M. 2018. Id̲j̲māʿ. In Encyclopaedia of Islam, 2nd ed. Edited by Peri Bearman, Thierry Bianquis, Clifford Edmund Bosworth, Emeri Johannes van Donzel and Wolfhart Peter Heinrichs. Leiden: Brill Online. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, Joshua. 1980. A Grammar of Mediaeval Judaeo-Arabic, 2nd ed. Jerusalem: The Magnes Press, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem. [Google Scholar]

- Blau, Joshua. 2006. A Dictionary of Mediaeval Judaeo-Arabic Texts. Jerusalem: Academy of the Hebrew Language. [Google Scholar]

- Blau, S. Yehushua. 2005. מילון לטקסטים ערביים-יהודיים מימי הביניים. Jerusalem: The Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanitie, p. 81. [Google Scholar]

- Brann, Ross. 2000. The Arabized Jews. In The Literature of Al-Andalus. Edited by Maria Rosa Menocal, Raymond P. Scheindlin and Michael Sells. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brody, Robert. 1993. Mif’alo ha-hilkhati shel Rav Se’adya Gaon. Peamim 54: 82–92. [Google Scholar]

- Brody, Robert. 2013. Sa’adyah Gaon. Oxford and Portland: The Littman Library of Jewish Civilization. [Google Scholar]

- Brody, Robert. 2015. Hibburim hilkhati’im shel Rav Se’adya Gaon. Jerusalem: Yad HaRav Nissim. [Google Scholar]

- Campanini, Massimo. 2006. Qada’/Qadar. In The Qur’an: An Encyclopedia. Edited by Oliver Leaman. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Mark R. 2017. Maimonides and the Merchants―Jewish Law and Society in the Medieval Islamic World. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, Mordechai A. 2016a. מילון הערבית-היהודית מימי הביניים לתעודות הגניזה של ספר הודו ולטקסטים אחרים. Jerusalem: Machon Ben Zvi, p. 119. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, Mordechai Akiva. 2016b. A Dictionary of Medieval Judeo-Arabic: In the India Book Letters from the Geniza and in Other Texts. Jerusalem: Izhak Ben-Zvi Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Greenbaum, Aaron. 1962. “שרידים בכתבי יד מפירושו של ר’ שמואל בן חפני על התורה”. In The Leo Jung Jubilee Volume. Edited by Menaḥem Kasher, Norman Lamm and Leonard Rosenfeld. New York: The Jewish Center, pp. 221–22. [Google Scholar]

- Griffel, Frank. 2011. Kalām. In Encyclopedia of Medieval Philosophy. Edited by Henrik Lagerlund. Dordrecht: Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güdemann, Moritz. 1873. Das Jüdische Unterrichtswesen Während der Spanisch-Arabischen Periode—Nebst Handschriftlichen Arabischen und Hebräischen Beilagen. Vienna: C. Gerold’s Sohn. [Google Scholar]

- Halkin, Abraham Shlomo. 1944. Classical and Arabic Material in Ibn Aknin’s ‘Hygiene of the Soul’. Proceedings of American Academy of Jewish Research 14: 25–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, Sherman A. 1996. Islamic Law and the State: The Constitutional Jurisprudence of Shihāb Al-Dīn al-Qarafi. Leiden, New York, and Köln: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Jany, Janosh. 2012. Judging in the Islamic, Jewish and Zoroastrian Legal Traditions: A Comparison of Theory and Practice. Farnham and Burlington: Catholic University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufhold, Hubert. 1984. Der Richter in den syrischen Rechtsquellen: Zum Einfluß islamischen Rechts auf die christlich-orientalische Rechtsliteratur (The judge in the Syriac legal sources: Regarding the influence of Islamic law and the Christian-oriental legal literature). Oriens Christianus 68: 91–113. [Google Scholar]

- Keil, Martha. 2016. Zeugen von Gewalt. Mittelalterliche hebräische Fragmente in niederösterreichischen Bibliotheken. In Quellen zur jüdischen Geschichte Niederösterreichs. Edited by Martha Keil and Elisabeth Loinig. St. Pölten: NÖ Institut für Landeskunde, pp. 13–36. [Google Scholar]

- Krauss-Sánchez, Heidi R. 2010. Ibn Abī al-Dam. In Encyclopedia of the Medieval Chronicle. Edited by Graeme Dunphy and Cristian Bratu. Leiden: Brill Online. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libson, Gideon. 1980. The Structure, Scope and Development of the Halakhic Monographs of Rav Shemuel Ben Ḥofni Gaon. In Te’uda XV: A Century of Genizah Research. Edited by Mordechai Akiva Friedman. Tel Aviv: Tel Aviv University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Libson, Gideon. 1991. Islamic Influence on Medieval Jewish Law? ‘Sefer ha’arevuth’ (Book of Surety) of Rav Shmuel ben Ḥofni Gaon and Its Relationship to Islamic Law. Studia Islamica 73: 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libson, Gideon. 1996. Halakha and Law in the Period of the Geonim. In An Introduction to the History and Sources of Jewish Law. Edited by Neil Hecht, B.S. Jackson, S.M. Passamaneck, D. Piattelli and A.M. Rabbelo. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Libson, Gideon. 1999. Terumat ha-geniza le-heqer ha-monografiot ha-hilkhatiot shel Rav Shemuel b. Ḥofni Gaon—mivnan heqefan ve-hitpat’hutan. Te’uda 15: 189–239. [Google Scholar]

- Libson, Gideon. 2003. Jewish and Islamic Law—A Comparative Study of Custom During the Geonic Period. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Malter, Henry. 1921. Saadia Gaon—His Life and Works. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society. [Google Scholar]

- Masud, Khalid Muhammad. 2007. Adab al-Qāḍī. In Encyclopaedia of Islam, 3rd ed. Edited by Kate Fleet, Gudrun Krämer, Denis Matringe, John Nawas and Everett Rowson. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masud, Khalid Muhammad, Rudolph Peters, and David S. Powers, eds. 2006. Qāḍīs and Their Courts: An Historical Survey. In Dispensing Justice in Islam—Qāḍīs and Their Judgments. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery, James E. 2007. Islamic Crosspollinations. In Islamic Crosspollinations―Interactions in the Medieval Middle East. Edited by Annas Akasoy, James E. Montgomery and Peter Portmann. Cambridge: Gibb Memorial Trust. [Google Scholar]

- Piamenta, Moshe. 1990. Dictionary of Post-Classical Yemeni Arabic. 2 vols. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Rafii, Raha. 2019. The Judgeship and the Twelver Shīʿī Adab Al-Qāḍī Genre, 11–14th Centuries C.E. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Rakover, Nahum. 1975. A Bibliography of Jewish Law—Modern Books, Monographs and Articles in Hebrew. Jerusalem: Harry Fischel Institute for Research in Jewish Law, vols. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Reiner, Rami. 2008. ‘A Tombstone Inscribed’: Titles Used to Describe the Deceased in Tombstones from Würzburg between 1147 and 1346. Tarbiz 77: 123–52. [Google Scholar]

- Schacht, Joseph, and Duncan B. MacDonald. 2018. Id̲j̲tihād. In Encyclopaedia of Islam, 2nd ed. Edited by P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C. E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel and W. P. Heinrichs. Leiden: Brill Online. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, Irene. 1990. Das Bild des Richters in der Adab al-Qāḍī Literatur. Frankfurt am Main, Bern, New York and Paris: Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Shahar, Ido. 2008. Legal Pluralism and the Study of Shari’a Courts. Islamic Law and Society 15: 112–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonsohn, Uriel I. 2011. A Common Justice—The Legal Allegiances of Christians and Jews under Early Islam. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sinai, Yuval 2010. The Religious Perspectives of the Judge’s Role in Talmudic Law. Journal of Law and Religion 25: 357–77.

- Sklare, David. 1996. Samuel ben Ḥofni Gaon and His Cultural World. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Sklare, David. 2014. The Reception of Mu’tazilism among Jews Who Were Not Professional Theologians. Intellectual History of the Islamicate World 2: 18–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stampfer, Y. Zvi. 2008. Laws of Divorce (Kitāb al-Ṭalāq) by Samuel ben Ḥofni Gaon. Jerusalem: Izhak Ben-Zvi Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Stroumsa, Sarah. 2003. Saadya and Jewish Kalam. In The Cambridge Companion to Medieval Jewish Philosophy. Edited by Daniel H. Frank and Oliver Leaman. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tsafrir, S. Nurit. 2017. Law and Jurisprudence. In Islam–History, Religion, Culture. Edited by Meir M. Bar-Asher and Meir Hatina. Jerusalem: Magnes Press, pp. 233–37. [Google Scholar]

- Yaffe, Hava Lazarus. 1981. Ha-yahas le-meqorot ha-halakha ba-Islam be-hashva’a la-Yahadut. In Proceedings of the World Congress of Jewish Studies. Jerusalem: World Union of Jewish Studies, vol. 8. [Google Scholar]

- Yaffe, Hava Lazarus. 1982. Ben halakha ba-Yehadut la-halakha ba-Islam: ‘Al kama hevdelim ‘iqariim u-mishni’im. Tarbiz 51: 207–25. [Google Scholar]

- Yagur, Moshe. 2017. Religious Identity and Communal Boundaries in Genizah Society (10th–13th Centuries): Proselytes, Slaves, Apostates. Ph.D. dissertation, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Jerusalem, Israel. [Google Scholar]

- Zellentin, Holger M. 2022. Law Beyond Israel–From the Bible to the Qur’an. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ariel, N.Y. Adab al-Qāḍi: Shared Juridical Virtues of Judaic and Islamic Leadership. Religions 2024, 15, 891. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15080891

Ariel NY. Adab al-Qāḍi: Shared Juridical Virtues of Judaic and Islamic Leadership. Religions. 2024; 15(8):891. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15080891

Chicago/Turabian StyleAriel, Neri Y. 2024. "Adab al-Qāḍi: Shared Juridical Virtues of Judaic and Islamic Leadership" Religions 15, no. 8: 891. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15080891

APA StyleAriel, N. Y. (2024). Adab al-Qāḍi: Shared Juridical Virtues of Judaic and Islamic Leadership. Religions, 15(8), 891. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15080891