1. Introduction

Among Korean traditional dances,

salpurichum (

salpuri dance), also known as the exorcism dance, is well known for representing “

han” (恨). This dance was showcased at the 1988 Seoul Olympics and played a key role in introducing the concept of

han to global audiences. In 1990, it was designated as a national intangible heritage, establishing its status as a representative traditional dance.

Salpurichum is distinct from other traditional dances in that it emphasizes the dual structure of

han and

sinmyeong (excited and enthusiastic mind/exhilaration) rather than other emotions typical of folk dances like “

heung” (excitement/joy) or “

meot” (taste/elegance).

Han signifies a particular miserable emotion mixed with sadness, remorse, resentment, grudge, and lamentation, driven by life’s tragedies in the Korean context (

Won-sun Choi 2007, p. 38). It can be linked to historical events such as colonization and the Korean war as well as personal hardships and struggles. According to Eun Go,

han is a uniquely Korean emotion, absent in other cultures, arising from and intertwined with Korean historical experiences (

Gil-sung Choi 1991, p. 14).

Yi-doo Cheon (

1993) noted, “The meaning of

han has continually shifted from a negative aspect to a positive one, reflecting our desires” (p. 41). The insistence that

han is exclusive to the Korean people has been replicated throughout modern times. This sentiment, which is considered unique, has endowed

salpurichum with its distinct Korean identity.

The belief that

salpurichum reflects

han as its core emotion has been accepted unquestionably since the 1970s, when research on

salpurichum commenced.

Han in

salpurichum was interpreted not only as the

han of the nation, but also as women’s

han discriminated against in Confucian society (

Lee and Kim 2017, p. 19). This is the meaning of

han, commonly associated with

salpurichum. Considering the original meaning of

salpurichum, which translates as “to solve”, ”untie”, or “unknot” (

puri), and refers to “cruel and severe energy that harms people”, “evil spirit”, or “harmful ghost” (

sal), it appears logical at first glance that

salpurichum originated from a negative emotion like

han. However, several photographs and drawings from the early 20th century that I recently encountered depict

salpurichum in a joyous atmosphere, which is starkly different from the solemnity of contemporary Korean traditional dance. Moreover, a video from the 1960s captured several women performing cheerful

salpurichum together, distinct from today’s somber ambiance. Considering these materials, it becomes inevitable to question whether the

han emotion was truly the driving force behind the creation of

salpurichum and was certainly the core sentiment during its initial development. This study explores when and why

salpurichum embraced

han and became a dance that represents this emotion.

Han is an emotion that emerged in modern Korean history. Yanagi Muneyoshi (1889–1961), a Japanese craft critic, characterized Joseon as the “beauty of sorrow” in a 1919 article in the newspaper

Yomiuri and later published these ideas in a book titled

Joseon to Sono Geijutsu in 1922 (

Yanagi 1922). Previously, the folk art of the Joseon Dynasty was characterized by satirical beauty and

heung in dance, but following Yanagi’s review,

han began to manifest as a Korean sentiment. From the 1980s, Yanagi’s perspective was extensively criticized in Korea for being orientalist and colonialist in its view of history (

Yu-gyung Choi 2009, p. 80). Today, there are many positive opinions regarding his assessment. Despite conflicting views—some praising Yanagi’s sharp insights into Joseon’s beauty and others criticizing him for portraying Korean people as weak from a colonial standpoint—his concept of the “beauty of sorrow” evolved into

han and gained acceptance in Korea through the 20th century. The discrepancy between the early and current forms of

salpurichum is likely linked to the evolution of

han, as

salpurichum came to incorporate the feelings of

han and gained recognition as a dance reflecting sadness at a certain point in the 20th century. To pinpoint this transition, it is imperative to explore the relationship between the periods when

han was emphasized as a national emotion and appeared in

salpurichum. Understanding the social demands and political situation that underpin these changes helps identify the context in which

han permeated

salpurichum. This exploration not only elucidates the emotional evolution of

salpurichum but also revives its diverse aspects from the past.

Therefore, this study seeks to examine the process by which han was established as a core emotion in salpurichum and uncovers the background and triggers leading to its formation. The scope of this study extends from the early 20th century, when salpurichum appeared, to 1990, when it was designated as an intangible heritage. This study utilizes a variety of literary materials, including photos, newspapers, books, and video recordings. By presenting new materials in the context of salpurichum, this study aims to re-examine and revise existing monotonous perspectives.

2. Study Trends on “Han” in Salpurichum

Research on

salpurichum began with Byeong-ho Jeong’s work in the late 1970s (

Jeong [1979] 1997). He hypothesized that

salpurichum originated from

Ssitgimgut, and despite lacking the shamanistic characteristics today, the dance inherently contains the

han of ritual properties. The

gut is a Korean exorcism ritual. Korean people believed that the soul of a deceased person continued to exist in the sky and could influence the destinies of the living. Souls harboring grudges or regrets were thought to cause harm to their living relatives. During the

gut, a shamanic dance was performed to engage with these spirits and resolve their

han. According to Jeong, this was the origin of

salpurichum. Following his research, a few studies published in the 1980s discussed the presence of

han in

salpurichum.

In-sook Moon (

1982) noted the presence of

han in the movements of

do-

salpurichum.

Hee-wan Chae (

1983) presupposed the dark aspects and

han of sadness in Korean dance and interpreted them as elements that

sinmyeong breaks through. He understood that the negative aspects of

han are encompassed by the positive force of

sinmyeong, exemplifying

salpuri as a transformation. He places the aesthetic significance of the dance on

sinmyeong. According to

Hyang Jo (

1987), the focus has shifted toward

han from

sinmyeong when understanding the emotional depth of

salpurichum. She cautiously specified this emotional characteristic of

salpurichum as

han, interpreted as a form of contraction, whereas

sinmyeong is viewed as a release. This suggests that

han is not merely associated with sadness but is a complex quality that coexists and interplays with

sinmyeong. In the mid-1980s, media coverage began to detail

han as a central sentiment in

salpurichum.

In the 1990s, research on

salpurichum intensified significantly, focusing on

han as the predominant sentiment. This surge was triggered by intangible heritage research reports on

salpurichum (

National Intangible Heritage Center 1989, No. 12;

1990, No. 13;

1991, No. 14) and the official designation of

salpurichum as a national intangible heritage in 1990. These reports were prepared for the designation of national intangible heritage, marking a turning point where

han started to be prominently associated with

salpurichum. This extensive academic survey, conducted on “

Seungmu (monk dance)” and “

Salpurichum”, involved 65 dancers from 13 regions across the country over three years from 1988 to 1990 in an effort to assess their value as intangible heritages. The scale and expertise of this study are unprecedented. Byeong-ho Jeong, a leading figure in dance theory who had been gaining recognition since the late 1970s for his research on folk arts, led this investigation. The academic impact of the findings was profound, with the added authority of the Cultural Heritage Administration. The report detailed the origin, style, formalization process, and transmission routes of

salpurichum and identified

han as the core sentiment.

Since its designation as a national intangible heritage in 1990, academic studies on salpurichum have increased significantly. Today, dozens of theses and journal papers can be easily accessed on salpurichum. These academic works usually analyze the aesthetic characteristics of salpurichum and how it manifests in performances or explore topics derived from han. Most of these studies presuppose that the form and essence of today’s salpurichum have remained unchanged since its inception and inherently originated from han. Interestingly, none of these papers critically addresses the changes in the form or sentiment of salpurichum performances over time. Given that the etymology of salpurichum dates back to shamanistic practices, the association of the term “Sal (煞)”—which connotes something deleterious or baneful—with han has seemingly been accepted without extensive re-examination.

Since 2000, English-language studies have also been published, such as those by

Won-sun Choi (

2007),

Lee and Kim (

2017), and

Maari Hinsberg (

2020), which align with earlier Korean research. Specifically, these studies assume that

salpurichum contains the emotions of

han from its inception. Lee and Kim explored the etymology of

salpurichum, the structure of

han, and the representative

salpurichum style. Based on Carl Gustav Jung’s theory of the collective unconscious, they viewed

han as a unique unconsciousness of Koreans formed over a long history marked by foreign invasions, hierarchical and status discrimination in Confucianism, and a culture of self-reflection in Buddhism.

However, recent studies have challenged this hypothesis. Since 2010, researchers such as

Ji-hye Kim (

2012),

Jeong-no Lee (

2019), and

Young-hee Kim (

2016) have observed that early and mid-20th-century portrayals of

salpurichum were joyous and entertaining. J. Kim attributed the transformation of

salpurichum into a serious expression of

han to a renewed awareness of tradition and shamanism from the 1960s to the 1970s. Hinsberg highlighted how Korea’s political situation influenced

salpurichum. The research mentions that to establish a colonially eroded national identity, the Chung-hee Park government promoted

Minjogjuui nationalism, which served as the background for national support of folklore. However, these were not the sole factors in the evolution of

salpurichum. The transformation of

salpurichum occurred during several significant historical waves. Therefore, this study aims to uncover the specific historical and cultural factors that elevated

han in

salpurichum, moving beyond established interpretations to a multifaceted understanding.

3. Various Aspects of Salpurichum in the Early 20th Century

Many articles have mentioned that Seong-jun Han’s Korean traditional dance recital in 1936 was considered the first-stage performance, formally characterized as “

salpurichum”, featuring a narrow, long silk scarf. However, according to the National Research Institute of Cultural Heritage,

gisaengs1 performed

salpurichum at the Wongaksa Theater in 1908 (

National Research Institute of Cultural Heritage 1998, p. 58). Additionally, the name “

salpurichum” as a dance appeared in 1918 in

Joseon Miin Bogam (Book about Joseon’s Beauties) (

Aoyagi 1918, pp. 62, 81).

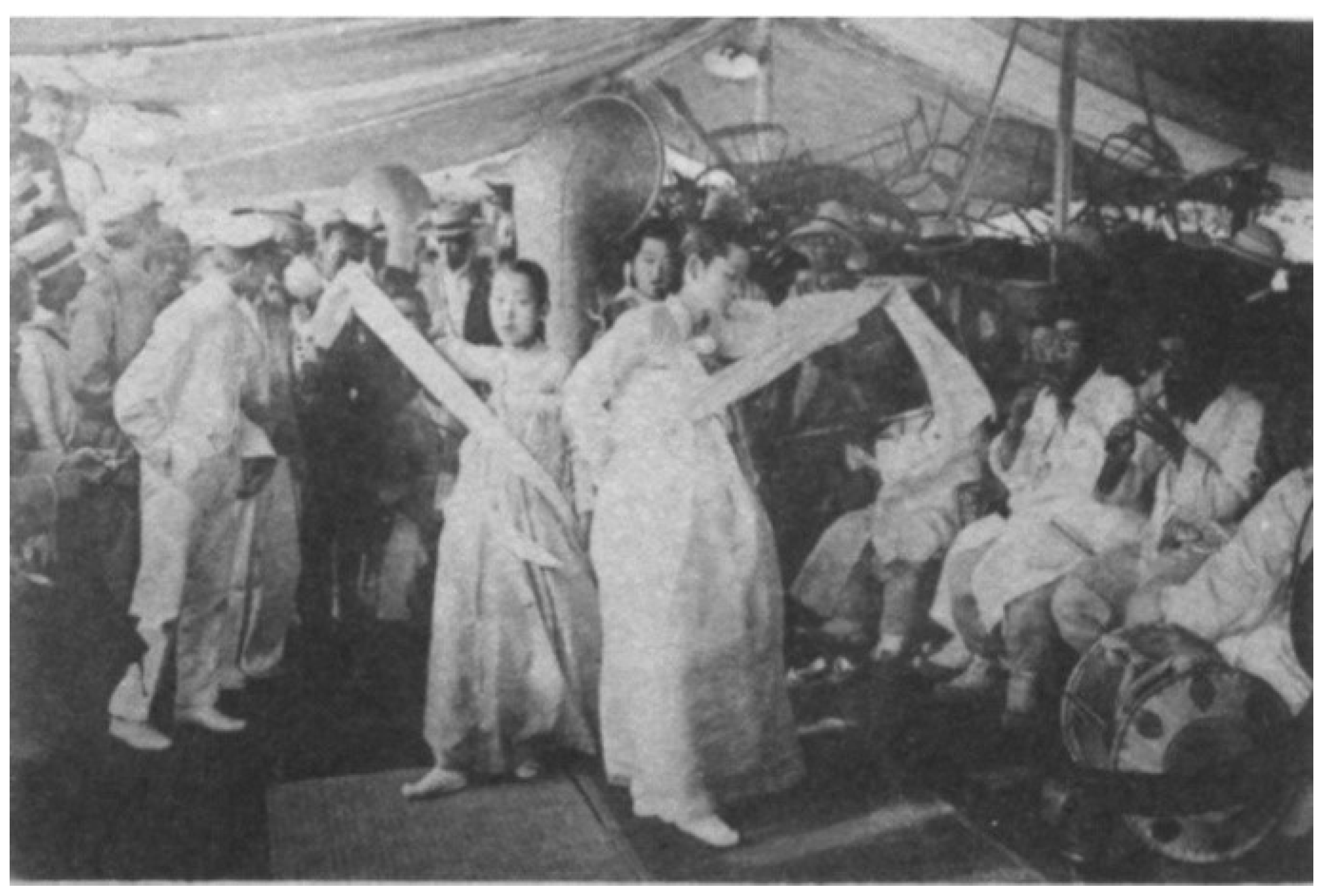

The following pictures provide a visual understanding of what

salpurichum looked like in the early 20th century: The oldest material on

salpurichum is a 1907 postcard (

Figure 1). It depicts two

gisaengs on a boat, each holding a long, narrow piece of fabric like a scarf surrounded by musicians and spectators. Although it has no title, the clothing and movements seem identical to today’s

salpurichum. The atmosphere appears somewhat chaotic, with the audience distracted and unmindful of the performance. The dancers used symmetrical movements indicative of a choreographed piece. Burton Holmes’ recording of Korea between 1901 and 1913 (

Figure 2) illustrates that several

gisaengs were seen in an unstructured formation, dancing and waving their handkerchiefs in what seemed to be an improvised style; some handkerchiefs were colored. The cover of

Singujabga Bu Gagogseon (new and old popular song collection) (

Figure 3) in 1932 depicted

gisaengs in colorful attire with yellow and white handkerchiefs. A man danced excitedly behind a woman while a

gisaeng on the right played the

janggu (hourglass-shaped drum). The scene contrasted sharply with the present mournful mood of

salpurichum, illustrating a vibrant and joyful atmosphere.

These materials exhibit a light and joyous atmosphere.

Salpurichum appeared feminine and fun, often performed with fabrics of varying length, sometimes as long as it is today and at other times shorter. The dancers performed both impromptu dances and group choreography. Although the fabric was occasionally white, colorful clothes and handkerchiefs were also used, indicating no strict adherence to color.

Ji-hye Kim (

2012, p. 11) analyzed this, stating, “before the 1960s,

gisaeng wanted to make economic profits through

salpurichum. Considering the role of the

gisaeng and the characteristics of

gwonbeon2, the dance would have been perceived as one that emphasized playfulness”. During the Japanese colonial period (1910–1945), the traditional

gisaeng system employed by government offices was abolished and replaced by the

gisaeng union, with

gisaengs performing in restaurants for profit. With the abolition of formal events for royalty and local celebrations,

gisaengs’ dancing skills diminished as their performances shifted to smaller, profit-driven venues such as restaurants (

Jeong-no Lee 2019, pp. 68–78). This shift likely influenced the atmosphere of

salpurichum.

Similar to most folk dances,

salpurichum were performed in each region by

gisaengs and

gwangdaes (clowns) according to their individual tastes, without any standard dance movements or forms. Seong-jun Han characterized this as “

Salpurichum” at his first performance held at Bumin Theater in 1936. It has since gradually been established as a stage dance. Cheon-heung Kim, a graduate of a government-affiliated music education institute, noted that

gisaengs, when excited at a drinking place, removed small handkerchiefs kept in the sleeves of their

jeogori (the upper part of the

hanbok,

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4) and gave impromptu dances. He supposed that Seong-jun Han formalized this practice and staged it, assigning the term “

salpurichum” (

Young-hee Kim 2006, pp. 141–42). This aligns with the description in the program of “

salpurichum” staged by Seong-jun Han, which stated, “It is a dance with laughter, humor, and popular beauty that properly follows the customs handed down from Joseon. Compared to classical dance, it has a unique charm as a dance form that has been passed down to the folk” (

Chosun Ilbo 1938).

From the 1910s to the 1930s, the era when

salpurichum was staged coincided with the peak of Korean resentment during the Japanese colonial period. In 1912, Japan prohibited

gut (exorcism rites) and downsized the

Jangagwon, which managed royal performances. This led to severe oppression of shamans,

gisaengs, and

gwangdaes, significantly affecting their livelihoods. Nevertheless, early 20th-century depictions and performances of

salpurichum show no trace of

han, as demonstrated by the circumstances in which

salpurichum was performed (

Figure 1), the atmosphere of the painting (

Figure 3), the video of the exciting movements (

Figure 2), and Han’s and Kim’s descriptions of the dance. The emotions associated with the dance were excitement, laughter, and humor—devoid of

han—unlike contemporary interpretations that suggest

salpurichum possesses a dual structure that transforms

han into a manifestation of

sinmyeong. The absence of

han in

salpurichum should be considered in the context of performers’ social standing. These were not classes that traditionally enjoyed affluence. During the Japanese colonial period, the primary resistance to policies aimed at eradicating traditional practices and criticism of the injustices of Japanese rule predominantly came from intellectuals. It is difficult to assert that the

gisaengs and

gwangdaes, who had a low status, experienced unprecedented oppression in an era when the official social hierarchy had been abolished. Moreover, even after Yanagi Muneyoshi’s discourse on the “beauty of sorrow”, the mournful aspects of

salpurichum have not been publicly discussed for an extended period.

The playful aspect of

salpurichum persisted at least until the early 1960s, as evidenced by the Chungnam Intangible Heritage video produced by the South Chungcheong Province Cultural Department in 1962 (

Figure 4). In this video, several women are seen performing

salpurichum. The choreography features both solo and group dances dominated by rhythmically swaying movements. The central female dancer has a coquettish smile and holds a long black fabric while wearing colorful

hanbok (Korean traditional clothes), a departure from the traditional white. Examining Han Young-sook’s

salpurichum reveals how dance costumes evolved until the mid-20th century. In the 1950s, a dark skirt and light

jeogori were worn and a short piece of fabric was used in the dance. In the 1960s, blue and pink

hanbok were worn, accompanied by a short fabric in the hand. In the 1970s, it changed to an indigo skirt and ivory

jeogori, or a jade-green combination (

Hinsberg 2020, p. 18). An article from

Chosun Ilbo (

Chosun newspaper) on 17 August 1962, praised a

salpurichum performance as a “masterpiece”, noting its “artistic atmosphere, tightly structured composition, and the expressive joyous movement of the shoulders” that showcased

heung of stylish Korean dance. Therefore, the exciting atmosphere of

salpurichum from the Japanese colonial period was maintained until at least the early 1960s and colorful costumes remained popular throughout the 1970s.

Salpurichum featured both structured choreography and improvisation, and performances without a piece of fabric were also recognized as

salpurichum. According to Seon-young Kang (

Tae-seon Choi 2006, p. 16) and several dancers in a research report (

National Intangible Heritage Center 1989,

1990,

1991), the fabric used in the dance lengthened postliberation from Japanese colonization to its current size. Ultimately,

salpurichum at that time can be understood as a “dance performed to the rhythm of

salpuri”, without strict adherence to a specific style of choreography, costumes, or props.

4. Korea’s Tragic Beauty and Rise of Han: Contradictory Narcissism (1960s and 1970s)

From the mid-1960s, the tone of salpurichum began to evolve. An article from Kyunghyang Shinmun (Kyunghyang newspaper) dated 26 April 1965 describes the accompanying traditional music and its emotional impact.

“The challenging and threatening rhythm of drums and

janggu, filled with dull pain, shakes and awakens the souls of the audience; as the delicate tremors of the flute and

tungso (six-holded bamboo flute) extend their long, mournful echoes, leaving traces of bitter sobs in the hearts of the listeners, the women begin to shyly express their wishes in the dance space. They raise the white

beoseon (traditional Korean socks) at the ends of their long skirts and the fingertips at the edges of their

banhijang jeogori3… Classical dance includes

salpurichum performed to traditional

sanjo4 music…”

The article uniformly characterizes traditional music as melancholic, reflecting the perception that it evokes sadness. It was also noted that the traditional dance was described as a woman in this type of music. Furthermore, the text highlighted that salpurichum was performed to traditional sanjo music, suggesting a flexible use of music and dance styles that were distinct from contemporary practices, where sanjo and salpurichum are distinct forms. Simultaneously, salpurichum was known by various names, including an “impromptu dance”, “heoteun dance”, and “handkerchief dance”. This portrayal aligns with the prevailing view of traditional dance as a mournful expression of femininity, as exemplified in Young-sook Han’s performances of that era.

In 1966, Young-sook Han delivered a performance of traditional dance that was highly acclaimed for its “authentic class and technique”. This performance was noted for its understated elegance, encapsulated in the observation that “It is the beauty of Korean dance that is not moving amidst a rush of music”, highlighting its restraint. During this performance, Young-sook Han presented a

salpurichum titled

Biyeonmu, which was described as “the most impressive” (

Park 1966). The term

Biyeonmu, meaning “flying swallow”, typically signifies agility. However, since Young-sook Han’s

Biyeonmu is characterized by slower movements and elegant pauses, it is interpreted as emphasizing femininity by alluding to a figure with a slim physique, like China’s Jo Bi-yeon. Originally, the dance was considered

salpurichum in that era; as the aforementioned article from

Kyunghyang Shinmun explained, a dance performed to

sanjo music was also called

salpurichum. However, it is currently classified as a

sanjo dance because it is accompanied by solo

gayageum (a Korean zither with 12 strings) music. The Biyeonmu Conservation Society described

Biyeonmu as “a dance that embraced the vitality and hope soaring amid women’s realistic hardships” (

Biyeonmu Conservation Society 2022). This shares a semantic structure with contemporary

salpurichum, which also transforms a woman’s

han into excitement. Initiated by this performance,

salpurichum transitioned from its previously joyous and playful character to being recognized as elegant and serene female artistry.

Salpurichum created a calm and sorrowful atmosphere through the 1960s and 1970s, closely aligning with a period marked by a rise in tragedy and sorrow in Korea, led by the Korean literary community. From the mid-1950s to the mid-1960s, intense discussions in the literary world focused on traditions, uniqueness, and “Koreanness”. At the significant 50th Anniversary of the New Literature Symposium in 1962, Cheol Baek identified “mournful sadness” as the defining emotional climate in the novels of writers who embodied Koreanness (

Ju-hyun Kim 2006, p. 23). He believed that this sentiment was contained in the works of authors such as Tae-jun Lee, Dong-ri Kim, Ji-seok Jeong, and Sun-won Hwang. In poetry that embraced Koreanness, this sentiment was often labeled as

han. Poet Dong-ju Lee (1920–1979), renowned for his local lyricism rooted in Korean sentiments, considered

han the essence of Korean poetry and critiqued modern intellectuals for neglecting it (

Hee-cheol Kim 1981, p. 88).

Han formed a poetic foundation. Similarly, Jae-sam Park frequently used lyrical

han in his poetry, in which the poetics of

han itself was his traditional discourse and theory (

Jo 2013, p. 129). He posited that

han was a unique Korean emotion, integral to the nation’s tradition, and inexplicable through Western binary logic (

Jo 2013, p. 131). The perspective of intellectuals led by the literary community positioned

han as a unique element of Korean tradition. During the 1960s and 1970s, these individual expressions of

han coalesced into a collective discourse, converging into a national

han by the postwar generation.

O-ryeong Lee’s column, published serially in 1963, ignited a sense of self-pity within the literary world, which spread expeditiously to the general public. Beginning in August 1963, He serialized “This is Korea”, focusing on Korean culture in the

Kyunghyang Shinmun over approximately two months. This series of self-reflective essays associated Koreans with images of “sadness”, ”misery”, and “self-affliction” (

Hong 2022, p. 425). He expressed, “I wanted to see my country like a wild animal licking its wounds” (

O-ryeong Lee 1963, p. 274), as he aimed to critique the tragic nature of Koreans from an internal perspective, distinct from Western viewpoints. O. Lee’s theory of the tragic nature of the Korean people represented the accumulated frustration of Koreans who endured Japanese colonial rule and the Korean War and was commended for its keen insight into Korean characteristics, achieving significant social consensus.

This perspective is akin to the interpretation of Joseon history through the colonial lens, which shaped oriental discourse in late Japanese colonial times. Despite Japan’s defeat seemingly severing this oriental discourse in colonial history, the acceptance of O. Lee’s views on the tragic Korean nature indicates that intellectuals themselves internalized Koreanness as a marker of inferiority.

Kwon and Cheon (

2012, p. 290) noted that “coloniality” and “ethnicity” overlapped, serving as hosts for each other. Essentially, the colonial view of history and traditional concepts became entwined with Korean identity, finding expressions through

han. In the 1960s, the Korean literary community’s quest to define Koreanness struggled to disengage from the colonial interpretation of history, but it is difficult to say whether their view of sad Koreans differed from the Japanese perception. Paradoxically, Korean people internalized Japan’s oriental perspective on Korea to differentiate themselves from Western culture. Specifically, Koreanness, embraced by Korean intellectuals in the 1960s, was identified with the late Joseon Dynasty temporally, underdeveloped and nonindustrialized rural areas geographically and socially with commoners devoid of wealth. This concept of Koreanness emerged as a form of contradictory narcissism, critiquing yet inheriting the colonial view of history.

Following this perception, it is natural that Koreanness, as recognized by academia and the arts, resonates with traditional folk arts. During the 1960s and the 1970s, the prevalence of nationalistic folklore linked many folk arts to shamanism, Korea’s unique religion, as a foundation for solidifying the national identity. Historical views from the early Japanese colonial period, which connected most artistic works to shamanistic origins to consolidate national identity, led to extensive folklore studies after the 1960s. Since the beginning of the Japanese colonial period in 1910, Korean historians began to promote

kukhon or “national spirit” in research and advance objectives to consolidate a national identity (

Tonk 2017, p. 12). Most works refer to the ancient roots of shamanism (

Tangherlini 1998, p. 130). Gil-seong Choi characterizes postliberation and, in particular, post-1960 research on shamanism as a combination of traditionalism and a reactionary “national spiritism” (

Tangherlini 1998, p. 130).

Culturally, a homogeneous, socially segmented, and politically patrimonial country has endeavored to establish and validate a colonially eroded national identity. The state would attempt this by using the available cultural, linguistic, and historical materials (

Hinsberg 2020, p. 9). This effort was evident in Korea during the 1970s. In the first five-year plan for literary revival, Chung-hee Park cultivated national pride and self-esteem, fostered a sense of subjectivity, and established a new national historical perspective that diverged from the colonial view of history. These actions aligned with nationalistic ideas (

Haeng-seon Kim 2012, p. 53). The ultimate goal was to promote national development and enhance national prestige (

Shin 1999, p. 216). A significant amount of money was invested between 1974 and 1978 to establish this national historical perspective, with 63% of the investment allocated to cultural heritage (

Shin 1999, pp. 216–17). Despite substantial criticism of the institutionalization of the traditional arts, Korean dancers of the time experienced high levels of pride and satisfaction. They were treated as VIPs with strong government support and had opportunities to participate in numerous overseas performances (

Moon-sook Kim 2005, pp. 127–70).

In the 1970s, as folklore flourished with government support,

salpurichum, stylized as stage art, was also examined as an integral part of folk art. B. Jeong, an authority on folklore, is at the forefront of this study. He began conducting field research on folk art in earnest during the 1970s and studied folk dance,

nong-ak (traditional Korean music performed by farmers),

talchum (mask dance), plays, and

gut. His research on folk dance had a significant impact. In 1978, while excavating and restoring

Ssitgimgut of southern Jeolla Province, he observed that

salpurichum used music that originated from the shamanic music of south Jeolla Province incorporated a long fabric, and shared some dance moves with shamanic practices. He asserted that when Seong-jun Han performed on stage, he held a long fabric and performed

salpurichum, shamanic music from south Jeolla Province. For this reason, the long white silk scarf of

salpurichum was thought to stem from shamans dancing in shamanistic rituals, with clothes imbued with the soul to alleviate the

han of the deceased or with

jijeon5 to cleanse and expel evil spirits from impure individuals (

National Research Institute of Cultural Heritage 1998, p. 54).

This study represents the first academic approach to

salpurichum, revealing its logical origins and acceptance as orthodoxy, although the fabric was more directly derived from a handkerchief of

gisaengs kept in the sleeves of their

jeogori. Therefore, the white scarf used in the dance holds several meanings connected to shamanism. It symbolizes purification, helping to remove bad spirits or negative energy; it expresses deep sorrow intertwined with unresolved resentment; finally, it serves as a bridge between the physical and spiritual worlds.

Salpurichum acquired religiousness, and its traditionality was recognized. However, Jeong noted that the contemporary form of the dance does not convey a religious character stating, “There is no religious form or movement in

salpurichum” (

Jeong 1981, p. 120). Despite this,

salpurichum followed his research and gradually began to emphasize shamanistic traditions using long white fabrics and white clothing. Within the larger flow of nationalist folklore,

salpurichum acquired its traditionality, with ambiguous sorrow transitioning into a shamanistic

han, thereby solidifying the emotions of

han within the dance.

5. Imprinting of Han and Standardization of Salpurichum: Binomial Opposition Usage of Tradition (1980s)

In the 1980s, the nationalistic tendency in shamanism research was criticized for its bias, which placed traditional culture at the highest value and imitated Japanese folklore. The positive perception of shamanism formed in the 1960s and the 1970s was largely influenced by political nationalism rather than academic sources. Although the recognition of the value of shamanism was criticized for these reasons, paradoxically, shamanism experienced a golden age in the 1980s as it was promoted by both the antigovernment movement and the authoritarian government, and each group viewed tradition as the root of Korean identity. From June 1987 to the Olympics in September 1988, the redefinition of the Republic of Korea was contested through the conscious enactment of traditional cultural expressions. These two groups invoked shamanism and shamanistic discursive practices as part of their political projects. The projections associated with these enactments of shamanism and the shamanistic became both an expression of Koreanness and an interpretation of the meaning of Korea. Concurrently, they emerged as an expression of political power (

Tangherlini 1998, pp. 128–29). Therefore, the shamanistic elements appropriated by the two groups were intimately linked to their political agendas. During this period,

salpurichum, which acquired religiousness through B. Jeong’s research on shamanism, symbolized

han and became central to traditional dance. As

han was emphasized in

salpurichum, music gradually incorporated a deep, mournful voice from the southern provinces. Additionally, the imagery of white clothes and fabric, similar to those used in

ssitgimgut, began to be imprinted in public as a typical image of

salpurichum. The incorporation of

han into

salpurichum can be attributed to the political agendas of nationalism promoted by two opposing groups. Tangherlini categorized these two groups of nationalism as “

minjungjuui” (ordinary people-centered) and “

jeontongjuui”. (tradition-centered).

First, let us consider “

minjungjuui” nationalism in the anti-government movement. In the 1980s, when the anti-government movement, specifically the democratization movement, reached its peak, the labor and college student movements intensified, placing tradition at the center of the antigovernment struggle. As strategic alliances between labor groups and intellectuals were formed, the democratization movement centered around university students and laborers, and university culture, which was liberal, romantic, and elite-oriented until the 1970s, rapidly shifted to socialist, realistic, and public-oriented (

Shin 1999, p. 225). The term “

minjung” became a symbol of collective resistance and empowerment, representing the disenfranchised and marginalized sectors of society (

Nam-hee Lee 2011, pp. 1–20). Groups’ identities were rooted in the ordinary people, and ordinary people’s identities were reflected in folk traditions. Koreans, who had experienced the forced severance of history and division, politically promoted nationalism as an inherent driving force while culturally projecting tradition to the public. The national cultural movement was suppressed by Japan during the colonial period because it was linked to Korean national liberation, and by the Korean authoritarian government after the division of North and South Korea because it was seen to be related to socialism. During the oppression, a national literary movement began, and subsequently, in performing arts, a national art movement expressed resistance through folk performances such as

talchum and

madanggeuk (yard theater). In the 1980s, the “ordinary people-centered character” in the university cultural movement shifted from “traditionality” to “militancy” (

Shin 1999, p. 227). Folk arts played a role in uniting people who were folklore subjects.

Salpurichum was at its center.

In July 1987, Ae-ju Lee, a Seoul National University professor, performed a

salpurichum well known as “

Sigugchum (dance about current domestic or international situations and issues)”(

Figure 5) at an event commemorating a labor agitator who died while resisting the Doo-hwan Chun government. Her dance was widely reported by foreign journalists (

Ae-ju Lee 2023, p. 243). The performance captured the

han of the oppressed and sublimated it into national

han. This event made

salpurichum famous worldwide.

Salpurichum came as a shock to dancers who had previously focused on constantly improving their artistry to establish themselves as stage artists; however, it emerged as a symbol of struggle and national resentment, often performed at protests, funerals, and memorial ceremonies for labor agitators.

Salpurichum, which had been performed solely as pure stage art, was transformed into a participatory dance. The shamanic nature, which had been regarded as having lost its function, was revived in these protest scenes, and national

han was reflected in

salpurichum, with

han becoming imprinted as the identity and core emotion of the dance. The sentiment of

han, which originated in the backdrop of the tragic Korean people, plays a role in highlighting people’s resentment at scenes of tragedy, akin to appeasing the resentment of the dead, as in

ssitgimgut.

Salpurichum, performed in white costumes, seems to represent people’s anger in a tragic atmosphere. While

salpurichum acquired theoretical religiousness through the hypothesis of shamanic origins, it also gained empirical religiousness through its performance at memorial ceremonies for the labor movement. By proving its shamanism, both theoretically and practically,

salpurichum established itself as a traditional dance form, with

han as its core sentiment.

Next, let us consider the

jeontongjuui nationalism of authoritarian governments. The government actively utilized traditional arts in the 1988 Seoul Olympics. In the 1980s, the Doo-hwan Chun government, which succeeded Chung-hee Park, actively sought national identity in shamanic traditions, placing the “white-robed nation” at the forefront. The self-defense mechanism that arose from the opening to Western culture solidified nationalism and promoted traditions during the 1988 Olympics. Shamanism was the historical foundation for Korea’s indigenous identity. Any casual observer of political events in the Republic of Korea from 1987 to 1988 could not overlook the ubiquity of the performances of traditional cultural forms that proliferated during this tumultuous period (

Tangherlini 1998, p. 128). Newspaper articles on

salpurichum, which numbered only 3–4 per year in the 1960s and about 20 per year in the 1970s, increased to 100 articles per year in the 1980s. Following Jeong’s study of

salpurichum, which secured its traditionality,

salpurichum began to be established as a representative Korean dance. Going forward,

han began to appear in

salpurichum performances. Jeong asserted that

salpurichum originated from

gut, although he emphasized that the dance did not have a religious connotation, but rather was an entertainment or artistic dance performed based on the music of

salpuri. However, he explained that performers of

gibang6 harbored

han because they were not treated as human beings and that

salpurichum was based on this resentment (

Jeong [1985] 2011b, p. 54). Following his hypothesis on the origin of

salpurichum,

han was retroactively emphasized during preparations for the 1988 Olympics.

In the 1980s, the appearance of Sook-ja Kim’s

do-

salpurichum supported Jeong’s hypothesis, and her

salpurichum received considerable attention. At the time,

salpurichum was standardized as an artistic dance using a fabric about 1.8 m long, similar to Mae-bang Lee and Young-sook Han’s

salpurichum. During this period, Sook-ja Kim’s newly-emerged

do-salpurichum featured a 3-m-long

salpurichum fabric, fully emitting a shamanistic atmosphere. Wearing white attire, she performed a dance to the music of the Gyeonggi Province

dang-gut7 with her waist tied like that of a shaman in a

gut performance. It reminds us of shamanic beliefs, although it was handed down from

gibang. Young-sook Han also often wore colored skirts until the early 1980s; however, from the mid-1980s, her costumes gradually transitioned to white with purple straps on

jeogori, similar to the style seen today. Just before the 1988 Olympics, the main style of

salpurichum in white costumes was standardized.

Meanwhile, some generations that experienced traditional dance during the Japanese colonial period maintained the character of

salpurichum based on their experiences, regardless of contemporary trends. Cheon-heung Kim danced in a simple

hanbok like in the early 20th century, and Mae-bang Lee wore colorful costumes throughout his life. Lee particularly focused on the beauty and artistry of

salpurichum itself as a stage art rather than the original meaning of the name, wearing jade-colored

durumagi8 and colorful clothes with a richly decorated

nambawi.9 I-jo Im and Sang-muk Chae, disciples of Lee, also adhered to wearing a gold topknot without being worried about the color of the costume. They are all men, and it can be seen that the male version of

salpurichum has made rapid progress since the 1980s. The emergence of male

salpurichum, despite the tradition being viewed as feminine, and

salpurichum, in particular, being interpreted as embodying women’s

han, shows that the dance was loved by both men and women, regardless of such interpretations. At that time, the dance community focused on designating it as an intangible heritage site.

Salpurichum moved away from improvisation and was refined into a high-level art amid the political support and dedication of dancers. With the

salpurichum performance at the 1988 Olympics, the image of

han was imprinted not only in Korea but also globally.

As we have seen thus far, in the 1980s, two types of salpurichum co-existed in binomial opposition. After acquiring religiousness and traditionality, han was strengthened in salpurichum during the Olympics based on the political agendas of both the antigovernment movement and the authoritarian government. Mainstream salpurichum was onstage, but wearing white clothes and emphasizing its original character first occurred in the protest scenes, which were sensitive to contemporary concerns. The love of tradition, divided between the antigovernment movement and authoritarian government, was also reflected in salpurichum, giving rise to its status as a participatory dance. Salpurichum, as a pure art, which was at the opposite end of the spectrum, was influenced by salpurichum as a participatory dance and later emphasized han. Consequently, salpurichum has come to embody not only religious and traditional aspects but also popularity, becoming standardized as an authentic Korean dance that represents han.

6. Completion of Han and Institutionalization of Salpurichum (1990s)

In 1990, salpurichum was designated a national intangible heritage. As mentioned above, it underwent a period in the 1970s and 1980s when han was formed and solidified, and its formalization as a stage dance was delayed owing to its inherently improvisational nature. Consequently, it was designated the most recent solo folk dance accredited by the Korea Heritage Service. In Korea, national certification holds great significance. Various national certification systems have been established with the national goal of achieving rapid industrialization and state-led economic development. Since the 1990s, certification has become an essential means of acknowledging individual abilities and influencing employment opportunities. In 1997, with the introduction of nationally recognized private certifications, the number of Korean qualifications in each field became one of the highest worldwide. In this environment, being designated a national intangible heritage by the Korea Heritage Service signifies recognition of the traditional and aesthetic value of dance, thereby enhancing its authority. Living human treasures, or holders of intangible heritage, recognized as the event are considered to hold the greatest honor, as they serve as strong proof of their artistic skills. For both dancers and the public, qualifications such as living human treasures, transmission instructors, and graduates serve as measures to confirm personal skills.

After

salpurichum was designated as a national intangible heritage event, its status increased and gained authority as Korea’s representative traditional dance. Academic research, which had been limited to a small number of people, became more active. The number of

salpurichum dance papers, which numbered only eight in the 1980s, more than tripled in the 1990s to nine journal papers and 17 theses. As the number of papers increased, explanations of

han were organized logically and systematically. The key catalyst for this was the publication of Yi-doo Cheon’s

Han-ui Gujo Yeongu (A Study on the Structure of Han) (

Cheon 1993). This book systematically collected explanations of

han that had previously been presented in a fragmentary and individual manner. It is evaluated as a masterpiece that reveals aspects and attributes of

han in Korean literature (

Mi-jin Kim 2022). This book serves as the foundational text for explaining

han. In the 1990s, as Western popular culture gained popularity,

han was marginalized in national sentiment. However,

han, supported by academic discourse, was often invoked when explaining Korean identity. The Movie

Seopyeonje in 1993 provides a representative example. Amid the surge of Western films, this Korean film about

pansori10 became explosively successful. Koreans found relief in the confirmation that, despite the influx of foreign culture, their own cultural heritage persisted. The relief stemmed from the belief that Koreanness could unite people across generations, class, and other divides (

Cho 2002, p. 139). The central theme of the films was the

han of tradition. The cruel narrative of blinding the heroine to achieve the perfect voice reveals a perspective that equates tradition with sorrow. The narrative structure, where a father blinds his young daughter, planting a ban (

han) in her heart that permeates into pansori, transforming her voice into a medium of salvation and release, closely mirrors

salpurichum, where

han is transcended into

sinmyeong. In

salpurichum, suppressed

han is transformed into artistic expression, elevating it beyond mere sorrow or resentment. This film strongly evoked

han sentiments among the public, who were immersed in Western culture, and

han was highlighted more broadly than

heung or

sinmyeong. The sorrowful beauty of the Korean people, which began in Yanagi, constituted the national subconscious in the 1990s, and was reproduced under the name of

han based on the selective beautification of history.

Jeong, who previously considered heung and han at the same level in salpurichum, emphasized han more in the 1990s. The following is the aesthetic sense of traditional dance described by him:

“Korean dance has a spirit of life that relieves human han and sorrow and transforms it into joy”.

“Our people have a sense of beauty that enjoys sadness, but later turns it into joy. The reason Koreans love sadness and cry a lot is not because they led hopeless lives, but because sadness is the most beautiful emotion and they enjoy it”.

“Compared with other dances, Sook-ja Kim’s do-salpurichum exudes a strong sense of han, sadness, and affection. Do-salpurichum is a concentrated form of han and sorrow”.

According to him, sadness is a beautiful expression by itself. The sadness in traditional dance and salpurichum is positively interpreted. In the 1990s, han emerged in Western culture, being portrayed as the timeless essence of the Korean people.

As the center of gravity shifted to

han, the dual structure of the serious introductory part and the plaintive climactic part of

salpurichum became standardized. The dance starts with a grieved look and then changes to a sad smile during

jajinmori11. The dual structure, overlapping grief and joy, requires complex emotional expression in the dance. Accordingly, it was believed that one could only truly perform

salpurichum after a long period of suffering and when one was old enough to understand sorrow. Today, the increasing age of dancers recognized for

salpurichum can be seen as a reflection of the imposition of

han as a core emotion.

Since the Sook-ja Kim and Mae-bang Lee styles of salpurichum were recognized as a national intangible heritage, the discovery of additional styles has been halted. This is not because the discovery of traditional dance has stopped, but because the historicity and tradition of other styles were deemed insufficient, or the experience of incomparably higher authority following designation as national intangible heritage made the process very cautious. Additionally, it was difficult to reach an agreement owing to sharp conflicts. Another reason is that the desire and interest in restoring the sense of cultural inferiority caused by the forced severance of tradition from the 1960s to the 1980s was pushed aside under the liberalization wave of the civilian government. The government, which had actively designated traditional culture as part of the restoration of sovereignty, no longer needed to rally the crowd through tradition as nationalism weakened under the wave of liberalization in the 1990s. With liberalization, the doors toward globalization were wide open, and people’s interests turned to overseas influences rather than focusing on the consciousness of the Korean people. As the labor and political movements that opposed the authoritarian government lost momentum, the resistant nature of salpurichum disappeared and was absorbed into stage dance. In the 1980s, salpurichum, which had been differentiated into stage dance and dance at scenes of protest, was reunited and unified as stage dance.

Additional designation by Korea Heritage Service has ceased, but it cannot be said that the discovery of salpurichum has ceased. Instead of a national intangible heritage, which has become a distant possibility, city or provincial intangible heritage designations have been made, such as Dong-an Lee style of Gyeonggi Province in 1991, Myeong-hwa Kwon style of Daegu Metropolitan City in 1995, and Seon Choi style of North Jeolla Province in 1996. Since 2000, other styles, such as the So-san Jeong style of Daegu Metropolitan City in 2015, the Ran Kim style of Daejeon Metropolitan City in 2012, and the Yeong-sook Han style of Seoul in 2015 have been designated as city or provincial intangible heritage. The national certification of salpurichum has continued fiercely, and the institutionalization of salpurichum has become increasingly severe. Accordingly, a hierarchy of traditional dances was formed, with national intangible heritage at the highest level, city or provincial intangible heritage at the second, and general salpurichum dance at the third level. The scarcity and authority of salpurichum, which has been selected as an intangible heritage site, increased, and those who wished to master it obtained certificates of completion to prove their artistic skills. The institutionalization of salpurichum reflects an aspect of Korea’s competitive society. Although it has expanded significantly in terms of quantity, this growth conceals the desire to prove one’s abilities through certification. The desire for tradition has shifted from nationalism to accreditation. Certifications have become important in Korea, where people experience fierce competition from an early age driven by rapid growth through short-term goal setting. This competitive mindset persists into adulthood. However, these certifications standardize and rigidify traditional dance, resulting in the alienation of traditional dancers who do not hold such titles. A hierarchy has emerged in traditional dance, leading to successors focusing on intangible heritage.

In the 1990s,

salpurichum achieved remarkable quantitative expansion as traditional dance was being taught as part of the curriculum in middle and high art schools and university dance departments. The proportion of people seeking to learn traditional dance forms has increased significantly. The institutionalization of

salpurichum had the negative effect of promoting uniformity and weakening improvisation; however, it also had the positive effect of allowing people to systematically learn standardized

salpurichum. It can be said that

salpurichum became highly refined, its techniques developed elaborately, and its aesthetic value as stage art increased. The idea that

salpurichum is “a dance that sublimates

han into

sinmyeong” was strengthened in the 1990s, and the sequences of

salpurichum were also fixed during this period and passed down to this day.

Cho (

2002) argued that the concepts of “

han” and “rapture” as uniquely “Korean” were completed in the 1990s. However, a self-definition that disregards the “First World” already dwelling within it is likely a form of self-deception and illusion (p. 150). The completion of

han and the institutionalization of

salpurichum should be viewed as the selection of

han within

salpurichum by a group of individuals sharing a distinct historical context.

7. Conclusions

This article demonstrates that the incorporation of han as a fundamental sentiment in salpurichum is a more recent development than is often assumed. In the early 20th century, salpurichum was referred to by various names, including “impromptu dance, “heoteun dance”, and “handkerchief dance”. The current name, however, was established in the mid-20th century. Until the early 1960s, salpurichum had a playful aspect. However, since the mid-1960s, it has been increasingly interpreted as an expression of women’s sorrow, reflecting the view that the entire tradition encapsulates women’s suffering. It was not until the late 1970s that the traditionality of salpurichum, based on shamanism, was explained comprehensively. It was difficult to elucidate the lineage of salpurichum compared to seungmu, which was derived from the Joseon Dynasty, or taepyeongmu, whose shamanic motifs were elucidated by Seong-jun Han. However, in the 1980s, as the shamanic origin hypothesis was accepted, the historical value of salpurichum was legitimized, establishing it as a strong traditional dance. This hypothesis of origin was never challenged; instead, the form of performance evolved toward this theory and became shamanistic. During the antigovernment movement in the 1980s, salpurichum was performed at protest scenes and was used as a shamanic dance to “dispel negative energy that harms the people”. Concurrently, the authoritarian government promoted shamanism as part of Korea’s indigenous identity during the 1988 Seoul Olympics, leading to salpurichum emerging as a representative traditional dance imbued with han.

Shamanism was the foundation of nationalism that ran through Korea’s modern and contemporary history, and among traditional dances, salpurichum was best suited. It can be said that han is a characteristic that was instilled in the process of establishing a modern national identity rather than being the fundamental basis for the birth of salpurichum. Han was embodied in salpurichum through reconstructed myths and memories that cultivated group belonging and sentiments. Han constructed the Korean unconsciousness through symbolic representation of the past. After salpurichum was designated as a national intangible heritage site in 1990, han was established in two interpretations: national han and women’s han. As salpurichum entered the national system, a hierarchy of holders, transmission instructors, and graduates emerged, and salpurichum became institutionalized. As a hierarchy has emerged in common folk dance, efforts by each style to enter this system are ongoing. In the process of explaining historicity to be recognized as intangible heritage, han was invoked almost always.

Occasionally, traditional imagery is invented because of a lack of documentation. Han can be said to be an invention of Koreans’ selective memories, according to this research. However, even if han in salpurichum was an intentional invention, the presence of han in the current salpurichum cannot be denied. This is because salpurichum has been imbued with han for half a century and functions as a tradition. When we are aware of the origin and background of han, a new tradition—a new salpurichum—can emerge at any time, breaking away from narrow values.