1. Introduction: Qusayr Amra Patron and Bathhouse

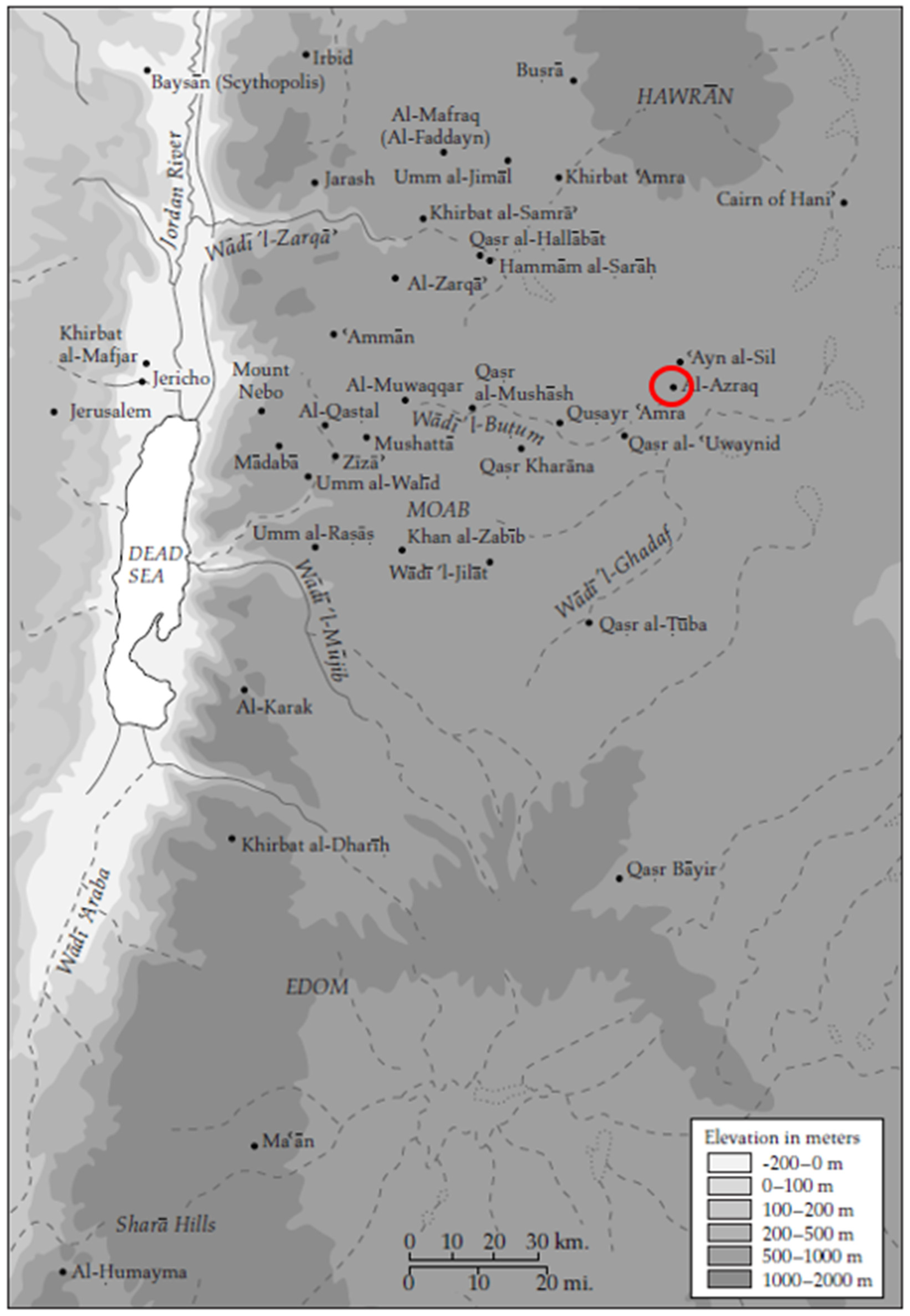

Qusayr Amra (قصر عمرة), which translates to “the Palace of Amra,” is a complex constructed during the Umayyad dynasty (660–749 CE). Located in the heart of the Jordanian desert, approximately 85 km east of Amman, within the oasis surrounding Al-Azraq (

Figure 1) (

Ali and Guidetti 2018), the site is notable for its profound history and cultural significance. The site is particularly renowned for its bathhouse, which is adorned with an extraordinary assemblage of frescoes. A substantial corpus of literature, including numerous books and articles, has been published to elucidate the intricacies and distinctive ornamental system of the frescoes. These publications aim to shed light on the visual and figurative interpretations of Amra’s culture, religion, and historical context.

The seminal research on Qusayr Amra, conducted by the Moravian-Czech traveler Aluis Musil (d. 1944), who first visited the site in 1898 (

Fowden 2004), established a distinctive framework for interpreting the frescoes. This framework has exerted a significant influence on subsequent scholarship. Musil’s analysis, further supported by contributions from scholars such as Garth Fowden, has led to the predominant hypothesis that the hedonistic character of its patron, Walid ibn Yazid—more commonly known as Walid II—serves as the primary explanation for the richness and diversity of the depicted scenes (

Ali 2017;

Fowden 2004). While the figure of the patron undoubtedly plays a central role in shaping the complex’s ornamental program, this line of interpretation risks oversimplifying the cultural and visual dynamics at play.

It is therefore essential to expand the inquiry beyond the patron’s personality and to ask how the identities of the artists, the intended audiences, and the broader Umayyad context shaped the visual program. This essay argues that the representations of women at Qusayr Amra are not merely reflections of a decadent court culture but rather deliberate adaptations of pre-Islamic artistic traditions, reworked to express evolving Umayyad ideals of beauty, gender, and hierarchy. By examining the interplay between visual imagery and textual sources, I aim to move beyond established narratives and offer a more nuanced understanding of how female figures at Qusayr Amra navigated the boundaries of belief, power, and identity during a pivotal period for Islamic social and religious conventions.

Despite ruling for a relatively brief period in Bilad al-Sham (Greater Syria), the Umayyad dynasty had a profound impact on the region’s cultural landscape. The visual evidence from this era indicates accelerated cultural evolution, underscoring the caliphs’ ambitious endeavor to establish a distinct cultural identity as a hallmark of their rule. Examining the visual findings of this period, it is essential to recognize the Umayyads’ profound engagement with established cultures, an engagement widely regarded as a seminal influence on the evolving Islamic esthetic. Scholars note that the architecture of desert palaces such as Qusayr ‘Amra reflects a court culture characterized by sensuality, luxury, and elite leisure activities. These elements, seen in the iconography, bath complexes, and overall design, have been associated with the lifestyles and preferences of patrons such as Walid II. They are frequently interpreted as manifestations of a refined and hedonistic aristocratic ethos (

Fowden 2004;

Hamilton 1988).

Umayyad rulers innovatively constructed numerous complexes designed to meet the diverse needs of the Muslim community. These included both public and private structures located in urban centers and the surrounding natural landscapes. Consequently, the architectural output can be roughly categorized into four types: public-religious (mosques), public-secular (administrative offices such as Dar al-Imara), private-secular (palaces), and private-religious (prayer areas within rural estates). In Qusayr Amra, excavation findings from 2001 show that the eastern and southern walls of a mosque, together with its mihrab, were still visible, suggesting that it could be interpreted as an open-air mosque (musalla) from the early 8th century. This indicates that despite the private secular tendency of the complex, there was a need for religious space within the site. The latter category is based on localized evidence (e.g., Hallabat) and should not be taken to suggest a rigid division between religious and secular spheres. Instead, it facilitates a more nuanced understanding of the diverse functions these spaces fulfilled. In many cases—such as Qusayr Amra—the overall design appears to have centered on crafting an intimate, personalized environment for the patron, integrating multiple aspects of elite life, including leisure, authority, and spiritual reflection. Desert spaces were also recognized as sites for negotiation and delineation of political boundaries, shaping the character of the prince and his capacity to contribute to his dynasty (

Grabar [1963] 2005;

Genequand 2006;

Hillenbrand 1982). Among these complexes, one of the most significant was the Umayyad bathhouse.

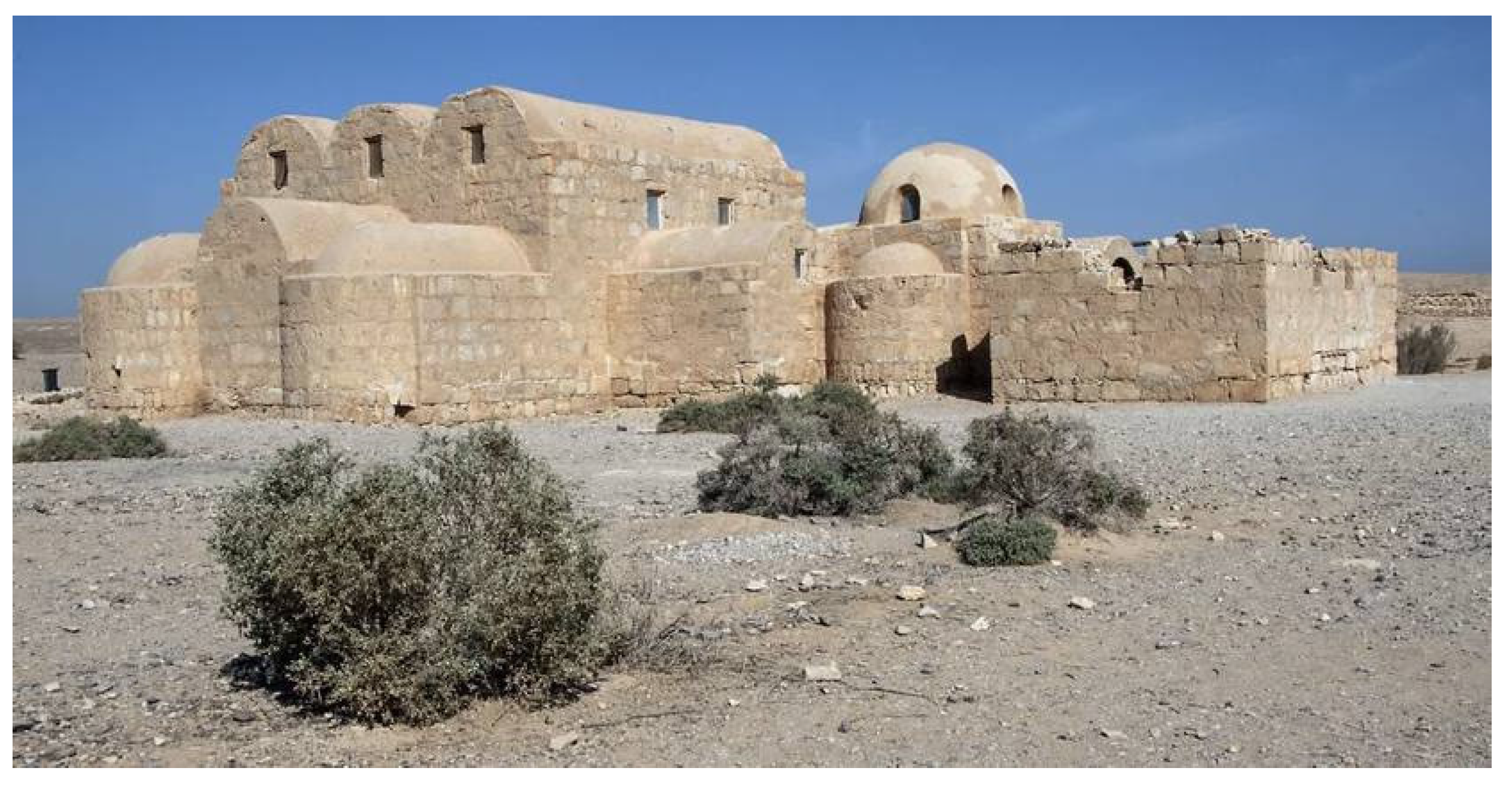

Like other desert complexes built during the Umayyad dynasty’s rule in Greater Syria, the complex at Qusayr Amra comprises numerous buildings designed for leisure, habitation, agriculture, and religious purposes (

Grabar [1963] 2005;

Genequand 2006). Built from local limestone, the structure suits the desert climate (

Figure 2). The absence of architectural ornamentation on its exterior facades and its remote location in the Jordanian desert have complicated efforts to ascertain its construction date. Furthermore, the architectural layout, characterized by a basilical ground plan influenced by Roman bathhouses, led early researchers to theorize that it was constructed during late antiquity (

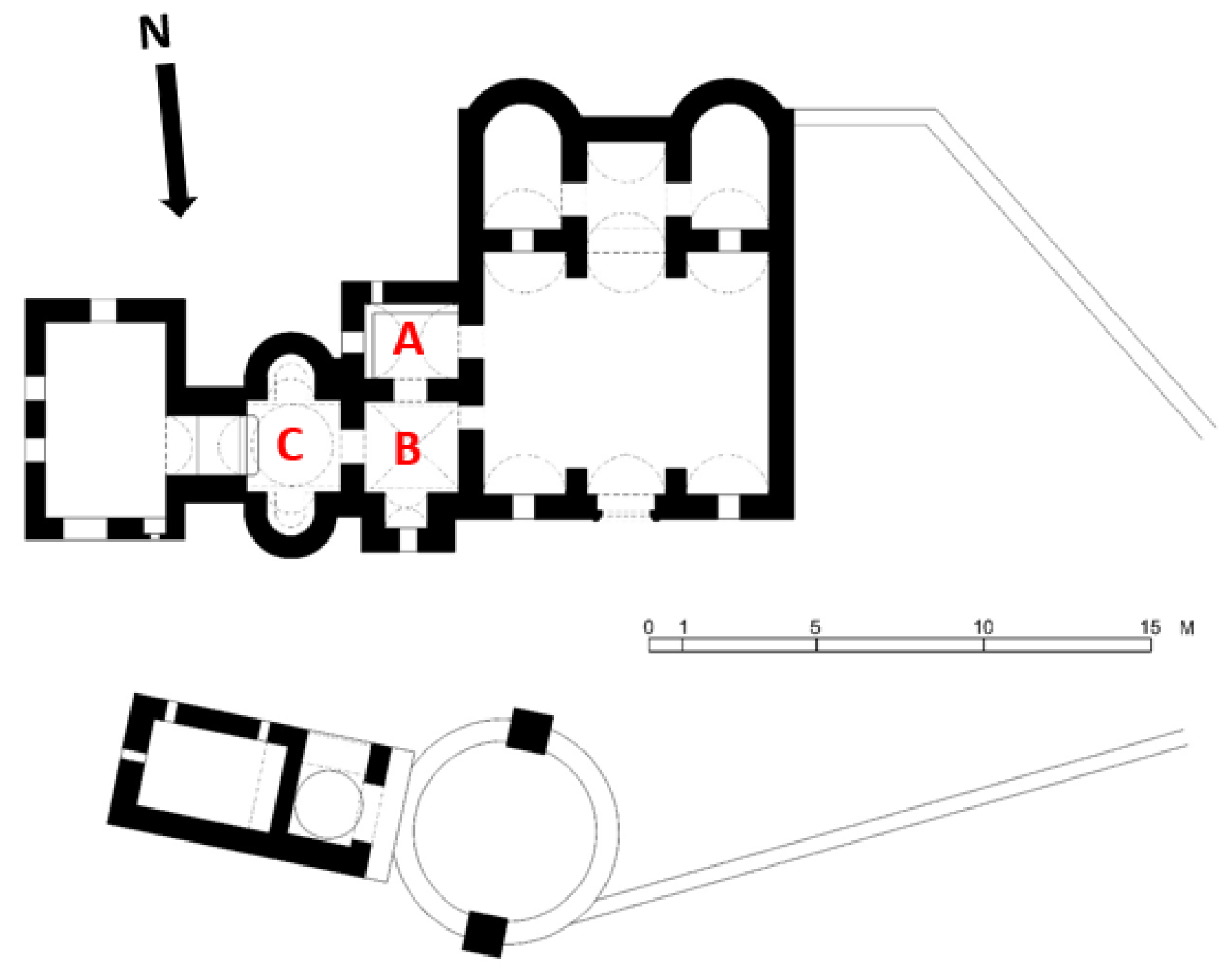

Guidetti 2016). In his 2004 publication, Garth Fowden thoroughly examines the site’s geographical context and its arrangement, emphasizing how these elements influenced the design of the complex. The eastern side of the site features the bathhouse, the most well-preserved structure, which Fowden assesses in terms of its architectural form and function. The bathhouse features a basilical rectangular nave, divided by triple barrel-vaulted ceilings from south to north. To the east of the nave lies the bathing area, which draws inspiration from classical bathhouses and comprises three distinct rooms: the Apodyterium (dressing room), the Tepidarium (warm room), and the Caldarium (hot room) (

Figure 3) (

Fowden 2004). Fowden hypothesizes that the isolated bathhouse functioned as a retreat for hunting expeditions in the desert. This may explain the absence of protective walls or fortifications commonly found in other Umayyad structures (

Mavroudi 2006).

In the spring of 2012, an Italian excavation team uncovered an inscription located in the upper section of the southern wall in the western aisle of the nave. The inscription, composed of three rows written in white Kufic script against a blue background, is attributed to Walid Ibn Yazid and indicates that he commissioned the construction of the structure between 743 and 744 (

Figure 4). The restoration work enables a partial translation of the inscription, which is as follows: “O God, make al-Walîd b. Yazîd, virtuous, the way you did with your pious servants! Surround him with the freshness of mercy, O Lord of the worlds and for your community, eternal … the religion the day of … all the…” (

Atzori and Palumbo 2006). The inscription’s notable absence of conventional, official, or authoritative titles such as “the one” or “the Khalifa” suggests the possibility of Walid’s involvement with the structure during his princely years (

Atzori and Palumbo 2006). This discovery resolves the long-debated question of the patron’s identity and invites a more complex view of Walid II’s persona and ambitions. As previously mentioned, interpretations of Walid II’s character have often been negative, influenced by his non-traditional and extravagant lifestyle. Numerous poets populated Walid’s court, and he composed many verses that openly expressed his desires without any attempt at moderation. One of his poems encapsulates this sentiment: “God and the holy angels hear me speak, and all the righteous worshippers of God. These are my heart’s desires: a cup of wine, the sound of music, and a pretty cheek to bite; a noble friend to drink with me, a nimble serving man to fill my bowl, a man of wit to talk, an artful minx with round young breasts in jeweled necklaces” (

Fowden 2004). However, such portrayals contributed to the perpetuation of preconceived notions about Walid, particularly during the Abbasid dynasty, which overthrew the Umayyads and sought to establish itself as the preeminent Islamic dynasty (

Hamilton 1988;

Ali 2017). Steven Judd has shown how political interests shaped these portrayals and should be approached critically. Rather than dismissing al-Walid II as a decadent figure, Judd suggests that his actions and esthetic preferences were part of a deliberate and provocative strategy of self-fashioning and elite leadership (

Judd 2008).

At this point, it is important to move beyond these established narratives and consider how the visual program at Qusayr Amra can be understood through a broader lens. In Qusayr Amra, several questions arise regarding the extent of Walid’s involvement in selecting the ornamental themes depicted in the bathhouse and the messages they convey. Research on his character has unduly influenced interpretations of the frescoes. Few attempts have been made to analyze the frescoes from a neutral, non-stereotyped perspective, with minimal consideration given to his lifestyle and character. The scenes in Qusayr Amra feature controversial representations that can be interpreted in various ways. These representations raise questions about whether the frescoes reflect the patron’s character or whether there are connections between the ornamental assemblage in Qusayr Amra and those found in other Umayyad palaces. Moreover, the question remains of whether Walid II should be primarily regarded through the lens of his personality or as a historical agent who played a role in shaping the visual and cultural languages of the Umayyad court. The fundamental question that must be addressed is whether Walid’s choices and character merely reflected existing Umayyad traditions or whether he actively contributed to redefining the dynasty’s cultural legacy through visual and architectural means. This complexity in interpreting Walid II’s role and the frescoes at Qusayr Amra calls for a nuanced methodological approach that moves beyond fixed historical narratives and opens space for multiple, sometimes contradictory, readings of the visual program.

In this context, Shahzad Bashir’s reflections provide a valuable framework for understanding the visual program of Qusayr Amra. In his chapter “Frescoes in the Desert,” from

A New Vision for Islamic Pasts and Futures, Bashir discusses the permeability of religious and cultural ideas expressed in the visual evidence, which often go unacknowledged in textual sources (

Bashir 2022). This approach mirrors a growing scholarly tendency to resist monolithic or schematic interpretations of Umayyad art, emphasizing the complexity of meanings embedded within visual forms. This article aligns with such a perspective by analyzing the representations of women in Qusayr Amra not only through symbolic or textual associations but also through their stylistic, spatial, and contextual features.

2. Figurative Representation in the Qusayr Amra Bathhouse: Between Imitation and Creative Adaptation

At the core of the Umayyad dynasty’s visual expression lies a deliberate process of drawing inspiration from and adapting earlier imagery. The intelligent and precise combination of existing images enabled their adaptation and transformation into a unique, original Umayyad representation. However, there is a systemic tendency in research to view the Umayyad images as mere variations or imitations of earlier imagery. This perspective implies a deficiency in skill or quality and reduces the Umayyad visual regime to a byproduct of imitation, rather than recognizing its role in shaping an Islamic worldview. This standpoint corresponds with Nadia Ali’s observation regarding the scholarly tendency to exclude Islamic imagination, which defects the analysis of the frescos (

Ali 2017, pp. 426–27). Rather than perceiving these works as mere imitations, it is more productive to approach them as a visual dialog shaped by the interaction of three participants: the patron, the creator, and the viewer. Assuming that at least the commissioner and the viewer were likely Muslim and perceived the imagery through a religious lens, it becomes necessary to ask: What meanings were negotiated through these images, and how did they coexist with Islamic values?

While the Muslims knowingly adopted traditions from earlier cultures, they simultaneously limited these to those preserving and honoring Islamic values. A notable example of this is the Muslim avoidance of figural imagery in explicitly religious contexts like mosques, Qur’ans, and holy precincts. A doctrine later interpreted as ‘Aniconism,’ stemming from the belief that the creation of living beings is a divinely exclusive capacity. This distinction between human figures and other types of imagery is important to consider when analyzing the frescos, which include both historical figures, such as the six kings, and more allegorical or possibly imagined female figures. In the Quran, God is depicted as Al-Musawwir (

المصور), or “the creator and the shaper”: “He is God: the Creator, the Originator, the Shaper. The best names belong to Him. Everything in the heavens and earth glorifies Him: He is the Almighty, the Wise.” [Surah 59:24, The Gathering (of Forces)].

1 While the idea that the creation of living beings is reserved for God is rooted in the Qur’anic portrayal of God as Al-Musawwir, more explicit prohibitions on figural imagery appear primarily in the Hadith literature. Although the Hadith collections were compiled in the 9th century, many oral traditions they preserve reflect theological concerns and practices already circulating during the Umayyad period. (e.g., Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī 5954; Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim 2108; Jāmiʿ al-Tirmidhī 2806).

As with numerous other religions, Islam interprets those forbidden acts in various ways in different locations and eras. Consequently, while the aforementioned objection likely influenced religious architecture and art—which are characterized by their floral patterns and abstract geometric forms—in certain dynasties, the figurative representation flourished in the “secular” space (

Allen 1988, p. 20). The figurative representation in Islamic art does not aim to offend or blaspheme; rather, it can be understood as a representation of the promised afterlife, which is believed to await pious believers as a reward. The two-dimensionality of the frescos compels the observer to detach from everyday life, situating the frescos in an imaginary paradise reserved only for true believers. To comprehensively understand the aniconism observed in Islamic art, one must first grasp the iconographic sources employed and the historical context in which these works were created (

Allen 1988, p. 20).

2Nadia Ali challenges the notion, initially posited in early research, that early Islamic representations are derived from earlier cultures, suggesting that they contain a combination of already known representations. Ali contends that rejecting the Muslim imagination and creativity results in a flawed analysis of the frescos. This flawed analysis, she argues, stems from the common misconception that understanding is primarily dependent on auditory perception, as seen in Judaism and Islam, as opposed to observational learning, characteristic of Greek and Latin cultures (

Ali 2017, p. 426). In order to validate her argument, Ali examines the Umayyad dynasty, which is known for its establishment of secular-courtly art characterized by a diverse array of figurative images and anthropomorphic representations. These artistic expressions were crafted to present the Islamic narrative. Ali’s approach highlights the need to recognize the creative agency of Umayyad artists and patrons. Building on this, my analysis explores how these figurative programs actively shaped, rather than merely reflected, evolving Islamic identities.

The visual and material evidence, based on both archeological and written sources, demonstrates the existence of a powerful and influential dynasty that managed to incorporate the traditions of earlier cultures while also adapting them to Umayyad needs. This is evident in the secular-courtly art depicted in the desert palaces built during the Umayyad dynasty. The palaces, constructed under the patronage of the princes, contained princely assemblages that depicted the king’s joyful life (

Allen 1988, pp. 17–37). These assemblages serve as a testament to the privileged pastimes of the princes, including drinking, watching women sing and dance, and hunting, which represent the leisure activities of the princes, their guests, and their entourage. The figurative frescoes in these palaces symbolically represent the prince’s success, wealth, cultural vitality, and political stability. Consequently, the frescoes serve as a secular space in a peripheral region, distinct from the daily lives of believers residing in urban centers.

In his seminal work on the subject of Islamic art, Grabar posited that we need to avoid the negative connotations of “secular art,” which can be complex and rich yet simultaneously have obvious boundaries, similar to religious art (

Grabar 1973, p. 141). The creation of such art under patronage allowed the patron to convey a message that was not necessarily detached from religious or dynastic values. Rather than merely copying existing traditions (mimesis), this art form was motivated by creating integrated, original iconography that served the dynasty’s values and ideals. These values included respect for the dynasty’s heritage and a desire to rise above it. In Grabar’s perspective, the Umayyad palace and the art that adorns it serve as visual chronicles of royal life, conveying the sensual pleasures of the patron. He asserts that these representations collectively fostered a distinctive ambiance, thereby distinguishing the Umayyad patron court and conceptualizing the Umayyad palaces as “breakout zones” situated beyond the public’s view (

Grabar 1955, pp. 3–4;

Fowden 2004, p. 690;

Ali 2017, p. 429).

The bathhouse in Qusayr Amra Palace, constructed as a separate architectural element, features an intricate and elaborate decorative scheme. The prevailing hypothesis posits that the majority of the figurative representations within the bathhouse depict secular activities, thereby offering insights into the multifaceted nature of life within the complex. In the context of early Islamic art, the characters depicted are not characterized by their divine attributes, as seen in earlier cultures, but rather by their roles in ancient narratives, familiar characters from pre-Islamic poetry, or depictions of everyday life, which the observers can recognize without the need for interpretation. Therefore, examining how the figurative representations in the palace, particularly in the bathhouse, may have been perceived in relation to notions of patronal behavior and etiquette is essential. While some scholars have interpreted these scenes as expressions of rebellion or transgression, particularly about al-Walid ibn Yazid’s reputation, this article seeks to explore alternative readings that consider their cultural and esthetic functions within early Islamic visual culture. Contrary to the common perception—especially outside the academic discourse—of early Islamic art as governed by a meticulous form of aniconism, recent scholarship has provided compelling evidence that calls for a more nuanced understanding. This reevaluation arises not only from the potency of visual representation but also from a critical re-reading of textual sources and a careful examination of their historical contexts (

Ali 2017, p. 427).

2.1. Negotiating Classical Heritage in the Qusayr Amra Bathhouse

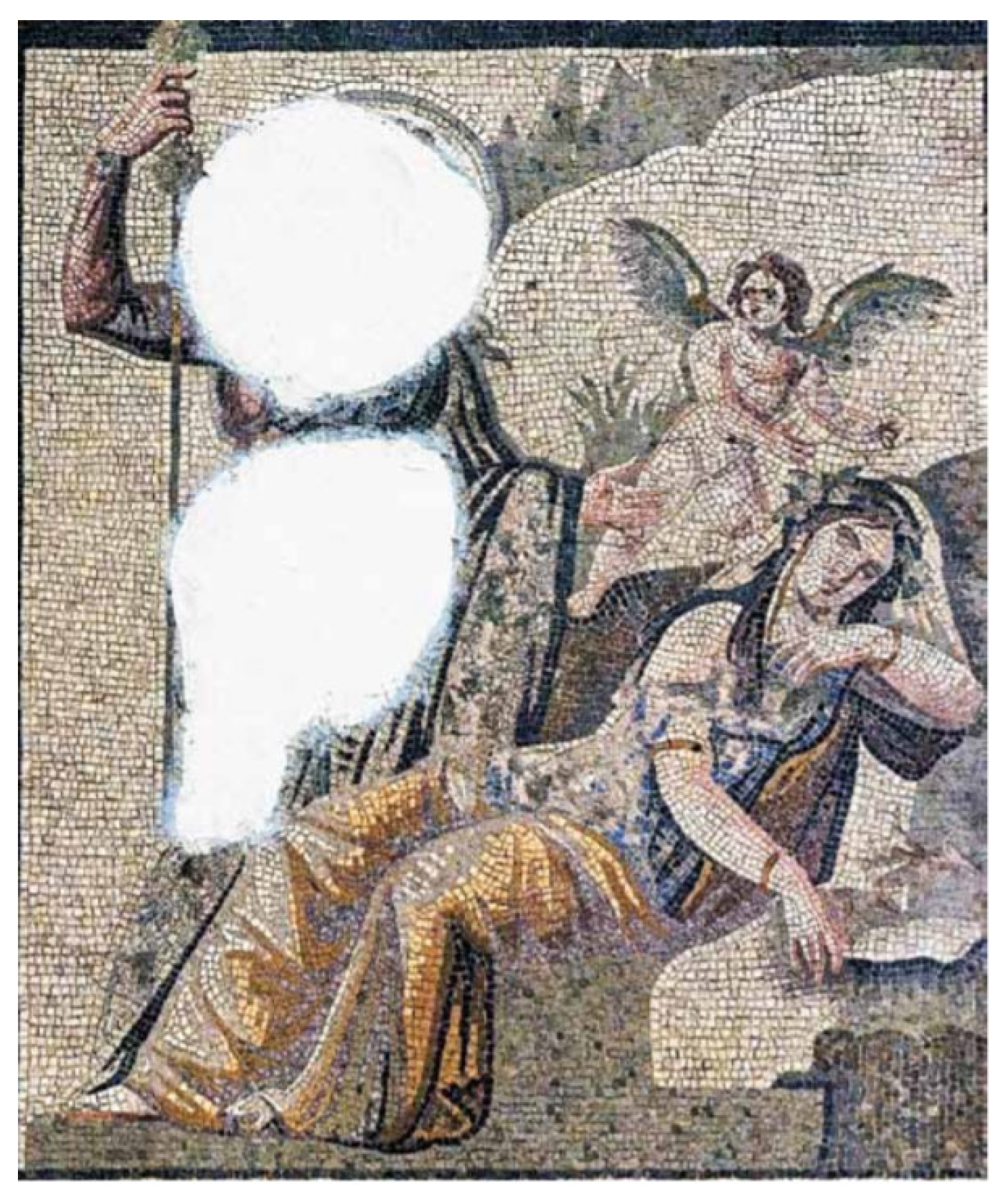

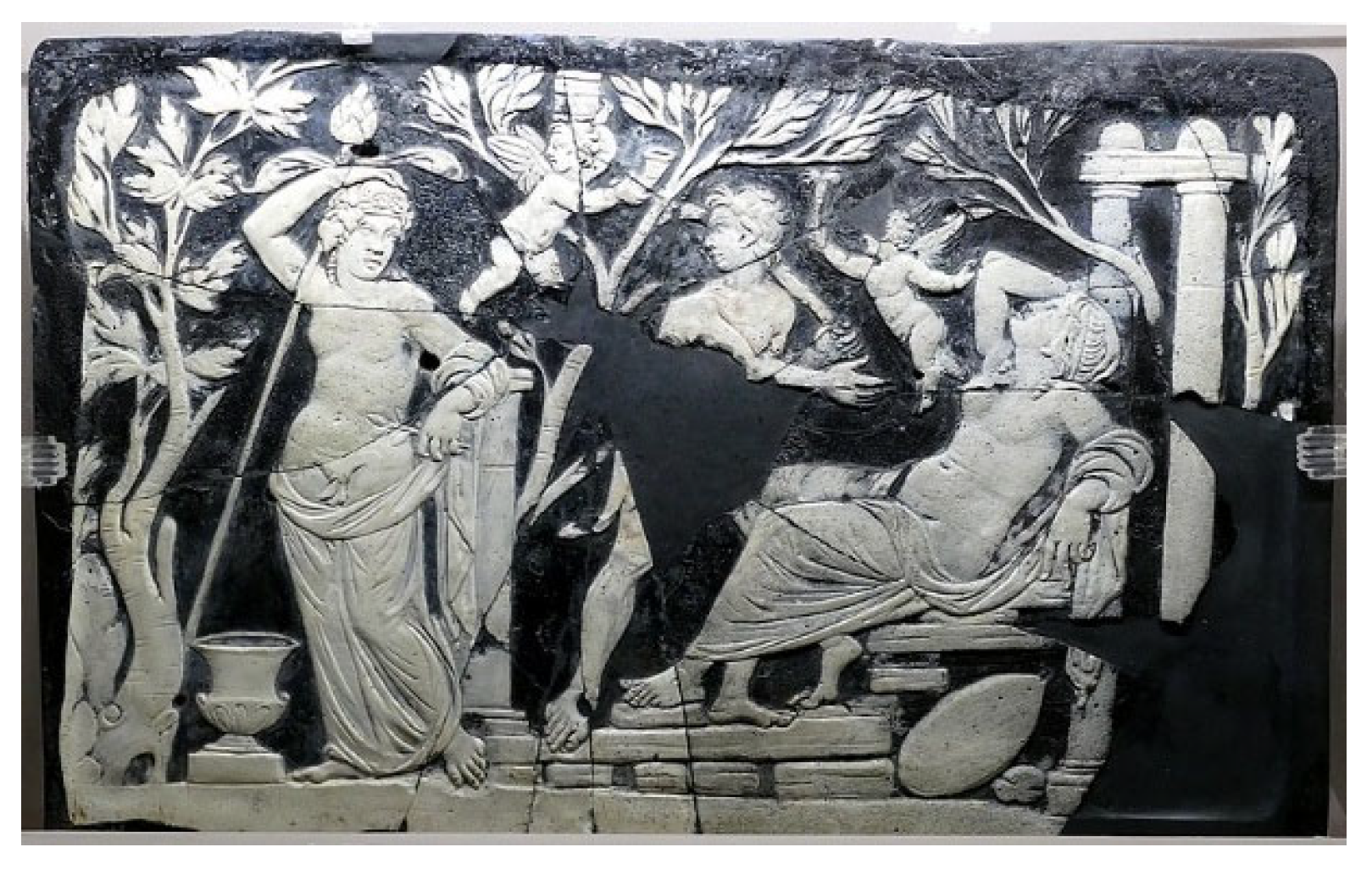

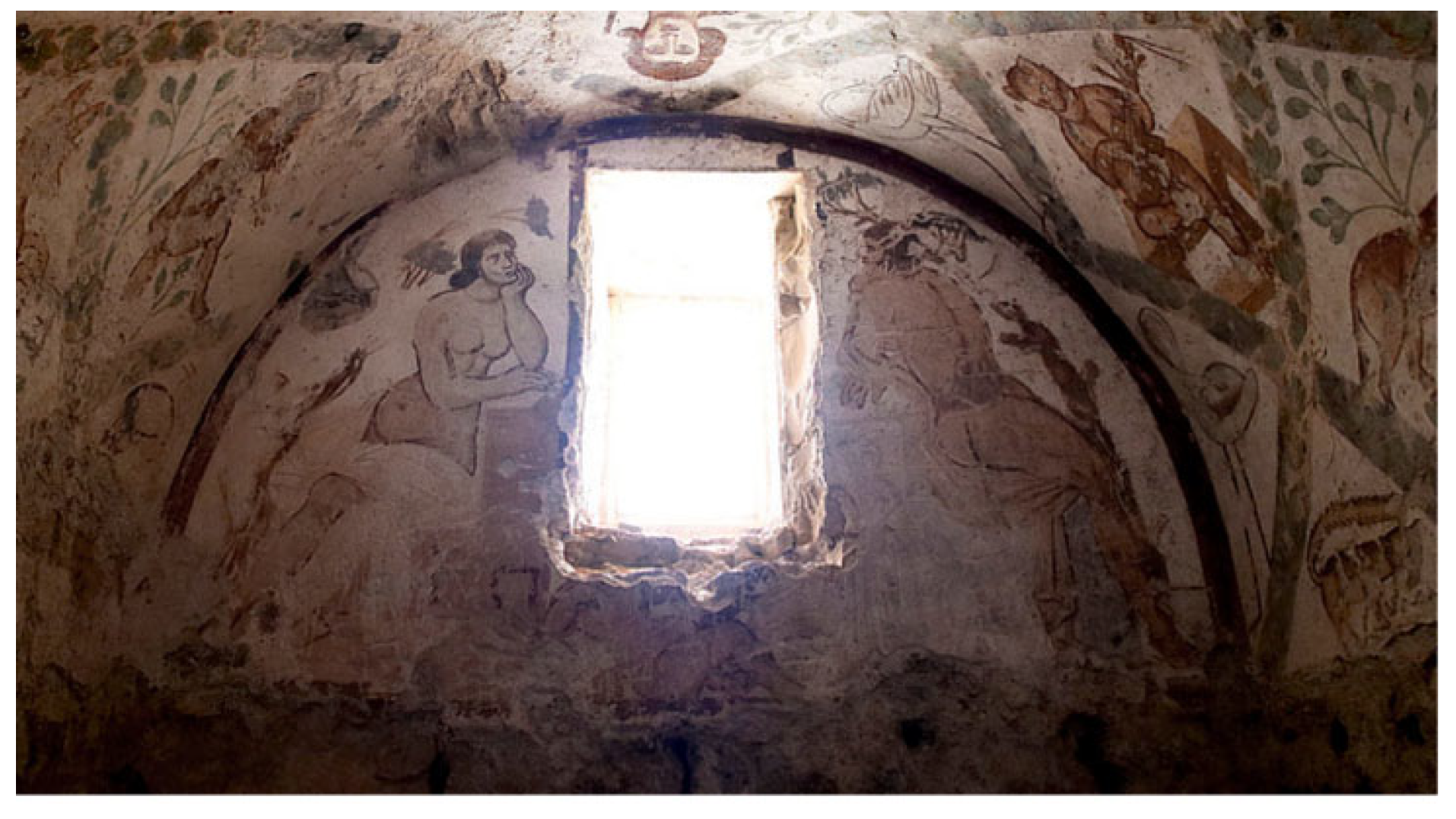

In order to enhance comprehension of the figurative representation in the complex, as well as to explore the influences and adaptation of certain elements from earlier cultures, both Fowden and Ali examined the image in the western lunette of the entrance door to the apodyterium (

Figure 5). The strategic placement of the image, which adorns a prominent architectural element situated between the primary social space of the complex and the dressing room, is indicative of its significance. This deliberate positioning prepares the observer for the intimate environment that awaits within (the tepidarium and caldarium). Additionally, despite the fresco’s location above the apodyterium entrance, visitors likely observed it with clarity upon exiting the heated rooms and turning back. This approach enables us to comprehend the fresco’s experience within the bathhouse environment.

The image features a landscape of rounded rocks, accompanied by a water source in the background. A young male is depicted leaning on one of the rocks, his head resting on his right hand. His gaze is directed towards a figure positioned at the lower portion of the lunette, situated within the forefront of the image. This figure, depicted in a state of repose, serves as a focal point for the composition. Adjacent to the figure’s feet, positioned to the left of the man, is a rectangular stone table or stand, upon which a water vessel is placed. On the opposite side of the figure, within the rounded lunette, is the trunk of a palm tree. Its branches are compressed, allowing for its complete depiction within the confines of the rounded lunette. Above the aforementioned figure, to the man’s left, a naked winged figure hovers, gesturing with its hands and pointing to the man. The resting figure is positioned diagonally and recumbent over layers of rounded fabric, appearing to be covered.

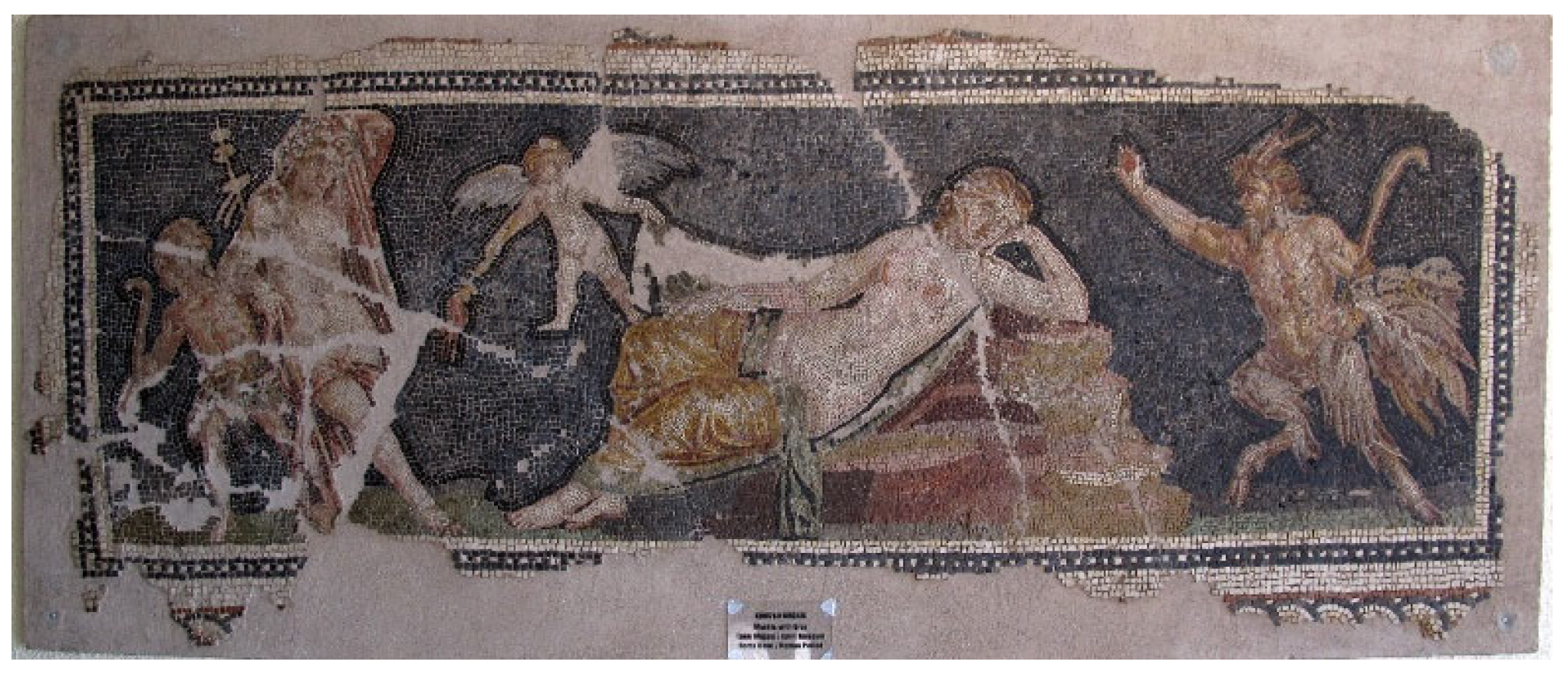

The image’s preservation and restoration have led to its association with Greek mythology, specifically the myth of Dionysus discovering Ariadne asleep on the shores of Naxos. This myth was frequently depicted in sixth-century miniatures, textiles, ivories, and ceramics (

Ali 2017, p. 432). These portable and mobile art objects played a crucial role in transmitting iconographic, stylistic, and compositional conventions across regions and periods, influencing immobile artworks such as frescoes. The portable nature of such artifacts suggests the possibility that the Umayyads may have been familiar with this image and its portrayal, even if they did not fully comprehend its significance. While Fowden and Ali underscore the importance of contemporary portable arts, they offer no evidence to substantiate their assertion. Ali’s analysis focused on a 4th-century immobile mosaic from Antioch, a subject also addressed by Fowden (

Figure 6) (

Fowden 2004;

Ali 2017).

A comparison of the fresco from Qusayr Amra to this 4th-century immobile mosaic reveals not only the similarities between them but also the differences between the Umayyad depiction and the well-known depictions from the Greek and Roman legacies. This comparison demonstrates that the Qusayr Amra artists were selective, deliberately modifying classical models to align with evolving notions of gender, propriety, and power, rather than passively replicating earlier traditions. First, while in Qusayr Amra, the man is depicted leaning over the rocks while contemplating; in contrast, Dionysus is usually depicted standing with his characteristic attributes, escorted by his entourage. Furthermore, a departure from the Greek and Roman legacies is evident in the depiction of Ariadne, who typically appears unclothed or partially unclothed but seems to be covered in this instance (

Ali 2017, p. 433). The decision to compare the fresco from Qusayr Amra to this 4th-century immobile mosaic should be understood as an interpretive exercise rather than as a straightforward comparison. This juxtaposition underscores the process of visual transformation, whereby a familiarity with earlier traditions is retained. At the same time, the imagery is modified to reflect evolving sensibilities regarding gender, propriety, and the gaze. The contour lines, the figure’s colors, and the effort to address female depictions and nudity contribute to the piece’s distinctiveness, marking it as a site of negotiation between classical esthetics and early Islamic norms.

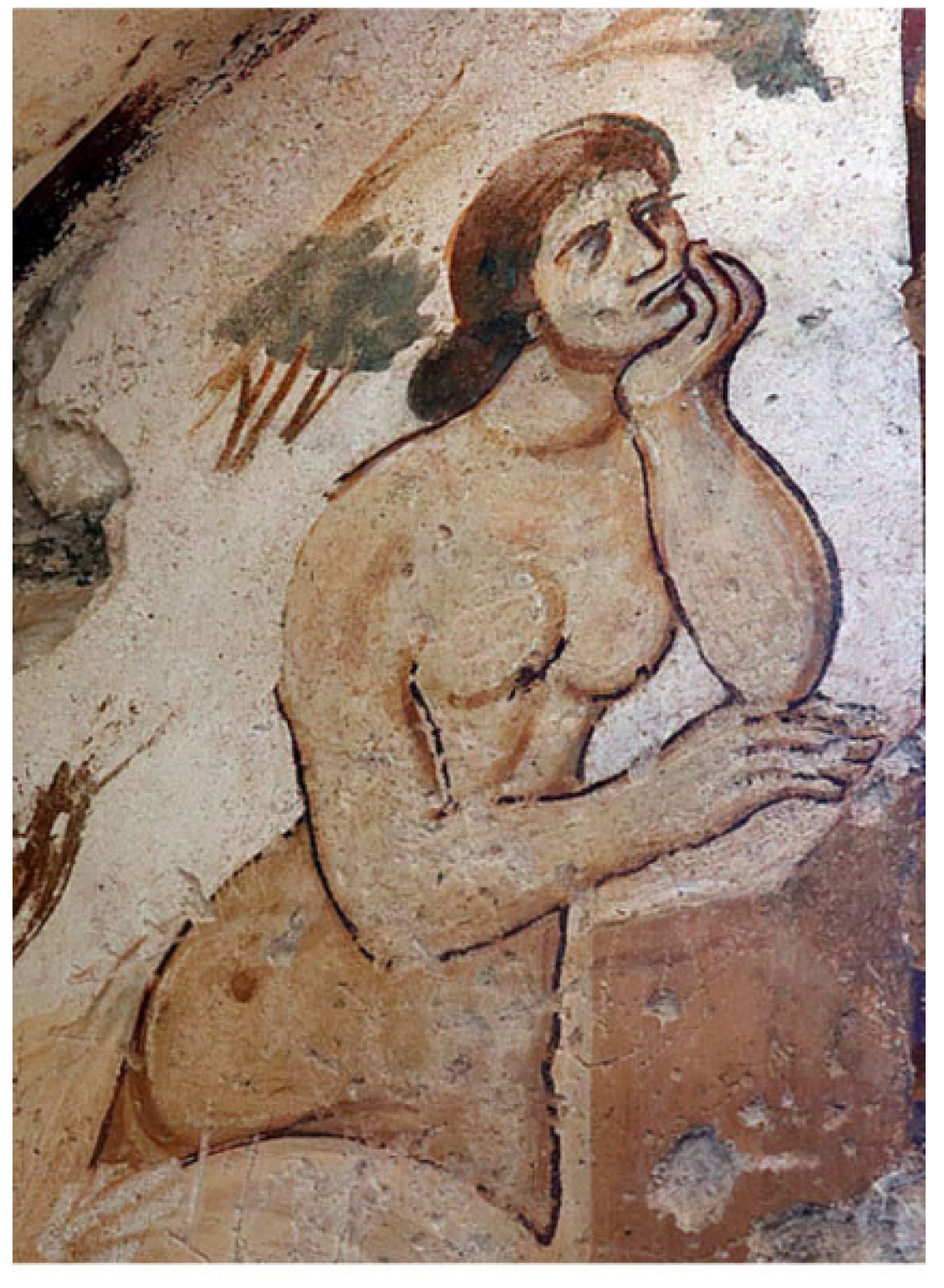

A thorough examination of the fresco reveals that the female figure, situated centrally and positioned on a white rug, is depicted with remarkable precision. However, given the passage of time and the restoration efforts undertaken at the site, the accuracy of these details is subject to uncertainty. The image is visually ambiguous—the contours of the female body are unclear, and certain areas, including her upper body, are indistinct. However, a close examination of the right side of the image, which encompasses the upper body, reveals that the female figure is draped in a second layer of fabric (darker brown) that gracefully envelops her legs, extending up to the area of her genitalia and continuing up to her head, underneath her upper body. The presence of this darker fabric suggests that her upper body is either naked or draped in a light fabric, thereby drawing attention to her silhouette. This tension between concealment and exposure animates the image and creates an erotic charge that relies not on explicit nudity but on visual suggestion. The contour lines of her body underscore the female curvature and the body, particularly at the waist. The figure’s orientation suggests a position of repose, with its left side facing the observer and its back turned towards the male figure. The remaining outlines appear to represent the figure’s right hand, which is positioned in a manner that suggests it is covering its breast and providing support for its head in a state of repose. The element that suggests the figure is dressed is likely the presence of a head covering or veil.

The decision to focus on this particular image is not merely due to its location in the bathhouse but also because it is one of the rare frescoes in the complex where the woman appears largely covered. Furthermore, when considering the influence of early imagery on the development of the Umayyads’ visual language, it is important to note the deliberate choice to differentiate the colors of the fabric, particularly in the depiction of the female genitalia. This motif may draw on ancient traditions of depicting Ariadne partially nude. Examining additional representations of Dionysus and Ariadne in the region thus offers valuable context for understanding the Umayyad adaptation.

This sophisticated reuse and reconfiguration of classical iconography invites reflection not only on the thematic content but also on the artistic agency behind it. Despite the limited knowledge regarding the identities of the artists who painted these scenes, their technical proficiency and their capacity to adapt well-known Greco-Roman motifs to a new cultural and architectural context suggest a high level of training, likely from workshops with experience in late antique visual traditions. Whether or not these artists were Muslims, they operated within a visual culture shaped by Umayyad tastes and expectations. The decision to place a scene, such as the sleeping Ariadne—modeled on Dionysian cycles—above the entrance to the apodyterium and in a position that required the viewer’s bodily movement to perceive it fully, indicates an intentional engagement with the sensory and symbolic experiences of elite male visitors. These men would likely recognize the allusion and its transformation. This is not a passive reception of classical heritage but an active, even playful, reworking that grants the patron a voice within a long visual genealogy. This act of re-staging a recognizable myth within a Umayyad leisure setting may reflect not only the patron’s cultural ambitions but also a subtle effort to assert dynastic prestige through visual wit and continuity with classical grandeur. In this context, we must consider how such artistic choices resonate with al-Walid II’s reputation as a controversial yet culturally refined figure. His distinct personal character—pleasure-seeking, cosmopolitan, and at times at odds with orthodox expectations—may have shaped the environment of Qusayr Amra as much as it shaped him. When examined through this particular lens, al-Walid II is not merely depicted as a passive hedonist but rather as an active patron engaged in curating a space that embodied his ideals, pleasures, and vision of rulership. The esthetic choices of the artist, which encompass poetry, architecture, and visual imagery, can be understood as strategic tools used to challenge religious and political expectations and to assert an alternative caliphal identity (

Judd 2008).

While the significance of this particular fresco is evident, it is important to contextualize it within the broader artistic repertoire of the complex, particularly in relation to its depictions of female figures. The bathhouse is replete with numerous representations of naked and semi-naked women, which prompts a crucial question: How do these portrayals align with the woman depicted in the Umayyad “Dionysus and Ariadne” scene? This inquiry explores the symbolic meaning attributed to the women depicted in Qusayr Amra and the Umayyad conception of female nudity. Are these images a reflection of desire, authority, mythology, or ritual? It is crucial to determine whether these images represent the relationships that could have been observed between the men who gazed at the wrapped women on the opposite side of the room or whether the female figure serves as a visual mediator to establish a connection between the apodyterium and the rest of the complex. Alternatively, perhaps the image should be read as a visual hinge—connecting the classical past to the Islamic present, myth to sociability, eroticism to restraint.

2.2. Stylistic Negotiation and Narrative Intent in the Apodyterium Ornamentation

In the opening pages of her article, Ali asserts that her objective is to investigate the historical approach and the manner in which interpretations are presented in the image. She examines the iconographic motifs from the region and the written sources that exert indirect influence on the image. A notable absence in the article is a stylistic analysis and an examination of how the image corresponds with other images in the complex, particularly in the apodyterium. Such comparison illuminates the narrative strategies employed by the craftsman and patron, revealing their intentions in shaping the visitor’s experience. The images in the complex are not merely random representations; they intend to foster contemplation and create an atmosphere that will accompany the visitors in the bathhouse.

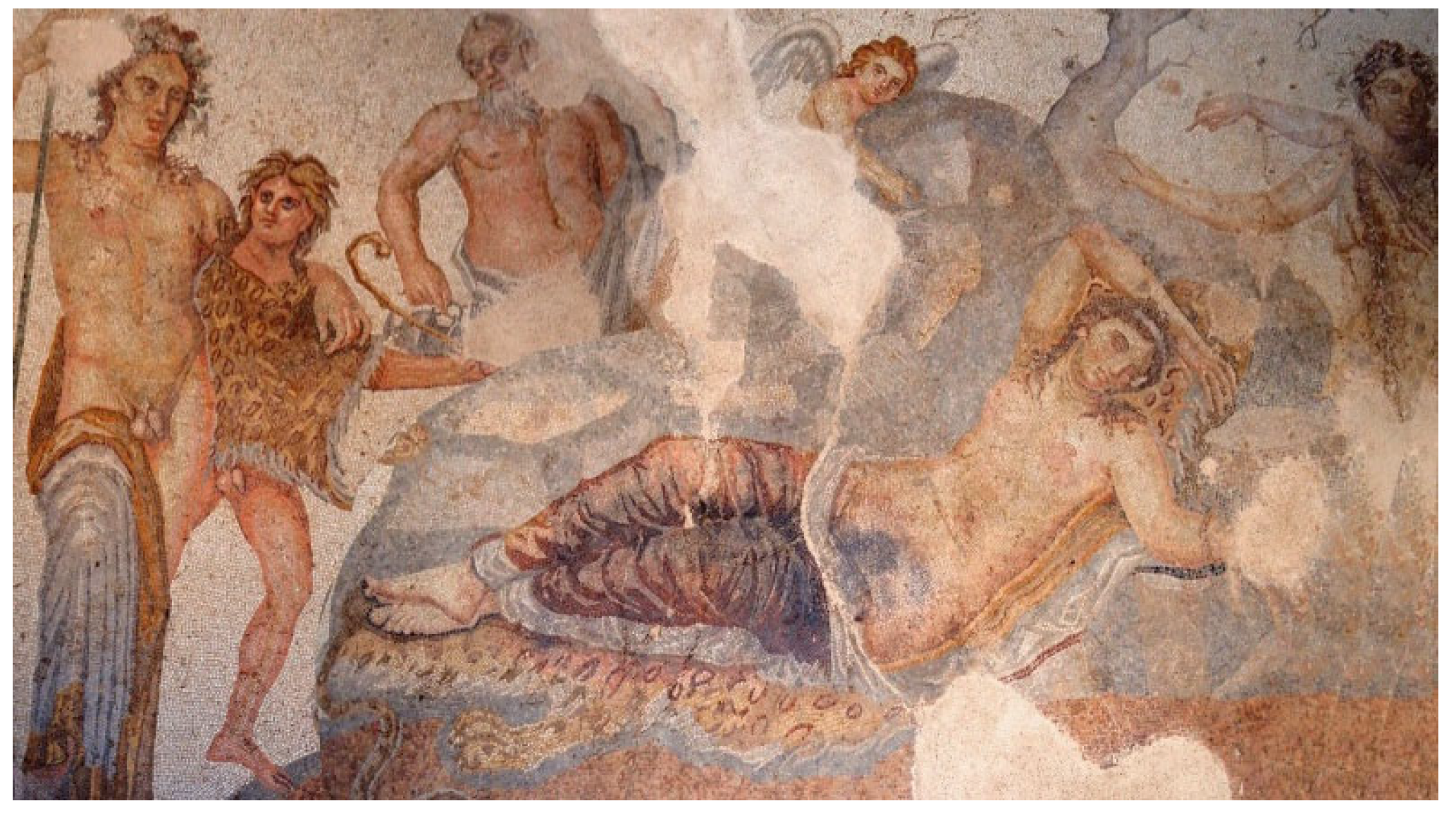

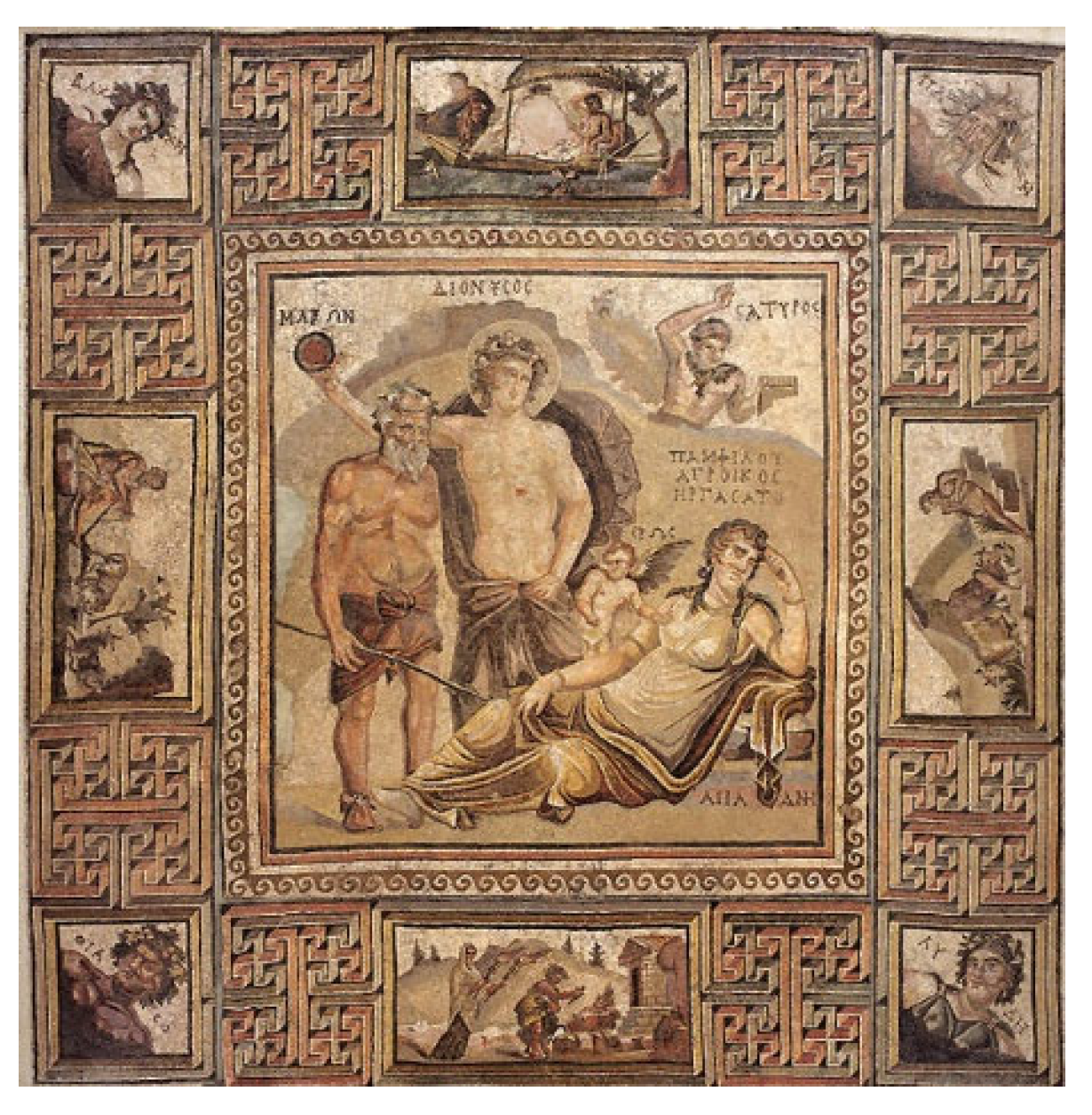

Alongside these, another central issue is the necessity of examining additional representations of Dionysus and Ariadne found in the region, most of which are depicted in portable art forms. These would likely have been familiar to the artist responsible for adorning Qusayr Amra bathhouse. If so, it means that he holds the responsibility to carefully adopt style or iconography from portable art found in the region. Those choices, which might demand the patron’s approval, were important for the process of identifying the Umayyad visual language and identity. While both Fowden and Ali acknowledged the significance of contemporary portable art, their arguments lack substantiating evidence. The mosaic in question portrays a dressed Ariadne, while the naked or semi-naked Ariadne is more suited to the bathhouse scene, as evidenced by several images from various locales. These images depict the well-known scene, and in most cases, wherein Ariadne is depicted semi-naked, she is also recumbent. In contrast, images depicting Ariadne in attire reveal her seated or reclining on rocks or sand (

Figure 7,

Figure 8,

Figure 9 and

Figure 10). A notable motif, evident in the image from Qusayr Amra, involves the placement of the fabric covering the lower body, starting at the genitalia and ending in a pointed or partially hidden manner. This gesture echoes a broader iconographic tradition, contributing to the sensual undertone of the image. A further analysis reveals another significant motif, namely the depiction of winged Eros. In Qusayr Amra, the direction of both his hand gesture and his “gaze” is oriented towards the male figure. In contrast, in other depictions, the gesturing of Eros’s hands is directed towards Ariadne, as if to guide Dionysus to her figure and his discovery thereof.

Although Fowden and Ali do not discuss the significance of the man’s pose, particularly his inclination over his hand, the implications of this artistic choice become especially meaningful when considered alongside the other ornamentations within the complex. A thorough examination of the early images depicting the myth (

Figure 7,

Figure 8,

Figure 9 and

Figure 10) reveals that the depiction of the head resting on the hand, supported by it, is predominantly attributed to Ariadne. The subject’s head is obscured by her hand or rests thereon, in a pose that exudes femininity and sexuality. The artist in Qusayr Amra made a conscious choice in depicting the female figure lying over her right hand, her head relaxed, and her eyes closed, leaving her body curves and the voyeurism motif as hints of her sexuality. In doing so, the artist separates the resting head from the female figure and transfers it to the male figure. This artistic choice resonates with the contemplative pose depicted in the adjacent wall of the apodyterium (

Figure 11), further emphasizing the thematic continuity within the artistic repertoire of Qusayr Amra.

At the core of the lunette and the focal point of the examined image is a window. On its right side, a man leans over his left hand, his body depicted in rotation so that his back is oriented towards the observer, and the left side of his face is visible. White fabric wraps the lower part of his figure, yet it does not obscure his unclothed body. On the opposite side of the window is a half-naked woman, her entire body oriented towards the observer. Her gaze is averted to the right, directed towards the man, while her head leans over her left hand (

Figure 12 and

Figure 13). The lower portion of her body is also wrapped in white fabric, evoking the imagery of Ariadne’s figure and other goddesses from Greek mythology. While her body contours emphasize her curves, as seen in the other female representation in the complex (see below), her body is not adorned similarly; instead, her pose connects her to the men beside her.

The window separates them, partly awakening them from the fantasies and the thoughts in which they are engaged and partly giving them an opening to manifest those fantasies. The presence of another unclothed figure below the window, which Fowden refers to as a “naked baby,” alludes to the intimate relationship between the man and woman above it (

Fowden 2004, p. 57). But a close analysis of this figure reveals contours that recall those of the woman, suggesting the possibility of it being a depiction of a naked woman rather than a baby. This prompts the following questions: What was the intended meaning of depictions of women in Qusayr Amra? What was the Umayyad conception of female nudity? Do these images depict the relationships that could have occurred between the men gazing upon the enrobed women on the other side of the room? Or does the female presence aim to connect the apodyterium to the rest of the complex? While not all of these questions can be fully answered, the discussion throughout this article opens a space to reflect on these issues and consider their broader cultural and visual implications.

As previously mentioned, Bashir’s critique of conventional textual-centered readings paved the way for more nuanced approaches to early Islamic art. Building on this, he notes that Nadia Ali’s recent research presents a novel perspective on the Qusayr Amra frescoes, highlighting the presence of agricultural imagery on the central ceiling panels and suggesting a more complex function and meaning for the site than the conventional interpretation of royal luxury alone (

Bashir 2022). These readings allow us to challenge longstanding assumptions by situating the frescoes within their specific cultural and contextual frameworks, as this research aims to do. Therefore, the aforementioned questions contribute to a broader, more pluralistic understanding of Umayyad material culture. By situating the apodyterium images within their broader visual and cultural context, this article moves beyond conventional interpretations and foregrounds the complexity of Umayyad material culture.

2.3. Female Nudity and the Negotiation of Modesty in Early Islamic Art

Female nudity played a central role in the iconography of bathhouses during late antiquity, and neither Christianity nor Islam immediately altered these established visual traditions. However, in the case of the bathhouse in Qusayr Amra, the interpretation of existing iconography necessitates a re-reading of its meaning. The female figures depicted in the bathhouse stand as a testament to the distinctive and innovative artistic style that characterizes the complex. The dark, wide contours that define these figures are prominent in all the characters depicted, yet the artists also make an effort to create movement by depicting the body half-turned. This results in a distortion of the correct anatomy and the proportions of the organs; however, the figures contain fascinating, gentle sensitivity, revealing the artists’ technical abilities, their use of color, and their ability to create convincing volume. The artists’ ingenuity is further highlighted by their use of the human body to convey abstract concepts, such as femininity and sexuality, exemplified by the rounded breasts, and fertility, symbolized by the rounded belly. This artistic approach melds clean linear depiction with underlying eroticism.

Building on this visual heritage, the imagery at Qusayr Amra should not be understood merely as a survival of pagan motifs, but as a deliberate and nuanced visual strategy. The erotic representation of women should not be read solely as a reflection of the personal tastes of the Umayyad patron, specifically Walid II, but rather as part of a broader artistic approach that engages with symbolic and allegorical meanings. Elements such as the rounded belly and breasts, while seemingly sensual, serve to articulate notions of fertility, beauty, and femininity in ways that merge classical references with local visual traditions. This interpretive framework calls for expanding the discussion beyond stylistic analysis and toward cultural and theological contexts. For instance, examining the depiction of female figures within the context of Qur’anic representations of women may shed light on how these images negotiate religious and esthetic paradigms in early Islamic art. This plurality of influences underscores the need for a contextual, rather than monolithic, approach to early Islamic visual culture.

An examination of the depictions of women in the Quran suggests several approaches to understanding women’s position in contemporary society. The verses that state women should be covered are detailed and restricted regarding both women’s clothing and conduct: “[Prophet], tell believing men to lower their glances and guard their private parts: that is purer for them. God is well aware of everything they do. Furthermore, tell believing women that they should lower their glances, guard their private parts, and not display their charms beyond what [it is acceptable] to reveal; they should let their headscarves fall to cover their necklines and not reveal their charms except to their husbands, their fathers, their husbands’ fathers, their sons, their husbands’ sons, their brothers, their brothers’ sons, their sisters’ sons, their womenfolk, their slaves, such men as attend them who have no sexual desire, or children who are not yet aware of women’s nakedness; they should not stamp their feet so as to draw attention to any hidden charms. Believers, all of you, turn to God so that you may prosper.” [Surah 24:30–31, The Light]

The commandment of a certain degree of invisibility of the female body is reflected in very few cases in the bathhouse complex, the main one being Dionysus and Ariadne. Is Ariadne “Qur’anized” in the sense that her figure has been visually adapted to reflect Islamic moral expectations regarding modesty? Is she depicted as per a moral standard? If so, is this standard just Qur’anic? Or is it also Judaeo-Christian? The emphasis on her covered and passive posture—especially when compared to classical representations of Ariadne—suggests a visual strategy that aligns with Qur’anic ideals of female propriety, even if it is not exclusively Islamic. An examination of the image, based on the Dionysus and Ariadne myth and its reflection of Quranic discourses, thus substantiates the artist’s commitment to the Quranic text and underscores its pivotal role in shaping and legitimizing Islamic thought within the Umayyad dynasty’s architectural framework. Therefore, the secularity that characterizes the images in the complex should be regarded in a positive light, as Oleg Grabar argued (

Grabar 1973, pp. 139–41).

The Quran frequently employs imagery that evokes the concept of ideal female physiques to describe paradise. Notably, the Quran offers no explicit description of the female form, except for the eyes. Thus, the imagery is derived from the Quran’s use of rhetorical means, which employ figurative language to stimulate the believer’s imagination, thereby fortifying their faith and motivating them to strive for paradise. This rhetorical approach draws upon pre-Islamic poetic traditions, highlighting the Quran’s utilization of figurative language to reinforce spiritual devotion and encourage the pursuit of righteousness: “everlasting youths will go round among them with glasses, flagons, and cups of a pure drink that causes no headache or intoxication; [there will be] any fruit they choose; the meat of any bird they like; and beautiful companions like hidden pearls: a reward for what they used to do. They will hear no idle or sinful talk there, only clean and wholesome speech. Those on the Right, what people they are! They will dwell amid thornless lote trees and clustered acacia with spreading shade, constantly flowing water, abundant fruits, unfailing, unforbidden, with incomparable companions We have specially created—virginal, loving, of matching age—for those on the Right, many from the past and many from later generations.” [Surah 56:17–40, That Which is Coming]

In these verses, the term “We have specially created” (

إِنَّآ أَنشَأْنَـٰهُنَّ إِنشَآءًۭ) is interpreted as signifying women created for the exclusive purpose of inhabiting the afterlife, or as wives of the faithful in this life. In the latter interpretation, the term “created” has also been understood to mean “recreated” or “renewed,” suggesting that God has restored the wives’ youth and virginity to appease their husbands in the afterlife. This understanding draws on traditional Qur’anic exegesis, particularly al-Ṭabarī’s commentary (

Al-Ṭabarī 1879–1901, 56:36), which emphasizes the women’s new, virginal state in Paradise—an idea further supported by the continuation of the verse, “and made them virgins” (

فَجَعَلْنَـٰهُنَّ أَبْكَارًا). The depiction of women in the Quranic text is intricately linked to the portrayal of paradise, suggesting that imagery depicting women in a state of undress can be interpreted as a partial representation of the rewards that await believers in the afterlife: “But those mindful of God will be in a safe place amid Gardens and springs, clothed in silk and fine brocade, facing one another: so it will be. We shall wed them to maidens with large, dark eyes. Secure and contented, they will call for every kind of fruit.” [Surah 44:51–55, The Smoke] “We have specially created—virginal. loving, of matching age—for those on the Right, many from the past, and many from later generations. [Surah 56:35–40, That Which is Coming]

If so, can we define the scenes in Qusayr Amra as a paradisiac utopia that combines Qur’anic descriptions and is completed by the look of real-life contemporary women? The tension between Qur’anic directives of modesty and the sensual pleasure in paradise is not resolved at this stage. However, Walid’s choices of images overrule the distinction between earthly and heavenly appearances. As the divinely appointed deputy (Khalifa) in this world, Walid sought to unite the realms of heaven and earth through artistic expression, particularly evident in the bathhouse paintings. The juxtaposition of secular and religious iconography serves to reinforce his assertion of authority, underscoring his claim to power. Ultimately, the Qusayr Amra bathhouse paintings exemplify the dynamic negotiation between inherited traditions and new Islamic ideals, offering a visual language that is both innovative and deeply rooted in its historical moment.

2.4. Visual Innovation Through the Bathing Beauty: Umayyad Art Between Tradition and Change

The depictions of the female figure in the complex violate the laws of physics in the material world, thereby giving form to the fantastical descriptions informed by the Islamic religion’s limitations and prohibitions. These descriptions are further empowered by their presence in the visual world of the surrounding empires. In his book, Fowden focuses on the bathing beauty in the main hall (

Figure 14). The artist’s decision to portray the bathing beauty as more significant than the Khalifa confers upon her a divinity that draws from pre-Islamic visual languages, particularly strong and empowered goddesses. Aphrodite, the Roman goddess of love, is a notable example, frequently depicted naked and adorned. Fowden made reference to a statue that may have served as a primary source of influence for the depiction of the bathing beauty figure: a statue of Aphrodite depicted in a state of nudity, with her hands positioned on the front of her body, adorned with ornaments and jewels (

Figure 15). Aphrodite played a significant role in the ornamentation of Roman bathhouses. The statue in question, discovered in Amman, was likely not only familiar to the artists who decorated the bathhouse in Qusayr Amra but also served as a source for the complex’s overall female representation. This analysis reveals how Umayyad artists selectively transformed classical motifs to articulate a culturally specific ideal of feminine beauty and power, reflecting broader social and religious dynamics.

The approach of the Qusayr Amra artisans and artists to the depiction of the ‘bathing beauty’ was influenced by certain elements of divinity that characterized Aphrodite and other myths. Building on this connection, the depiction of the ‘bathing beauty’ exemplifies the Umayyad reinterpretation of classical motifs within an Islamic artistic framework. The details that reflect the influences manifested by the jewels that empower the sexuality of the female body are well represented. Throughout Qusayr Amra, the following elements are evident: the pendants that bisect the body, the diversity of jewels, the styled hair, and the rising hands. The combination of diverse traditions and the introduction of movement in the figures, achieved through distortion of anatomical depiction, serves to render the figures more tangible. This approach underscores the fundamental disparity between ancient beauty standards and those that emerged during the Umayyad period. The Umayyad artistic style, characterized by its distinctiveness from the art of the larger empires, is evident in the depiction of the ‘bathing beauty’. While Greek and Roman art idealized a specific type of female beauty characterized by eroticism and elegance, as evidenced by the depiction of small breasts and proportional hips, Umayyad art depicted women with large, rounded breasts, thus creating an identifying mark of their supposed character. Furthermore, the Greek facial features of Aphrodite embody the archetype of noble beauty, characterized by a refined nose, delicate lips, and subtle eyebrows. In contrast, the Umayyad women are distinguished by their prominent eyes, accentuated by long, thick eyelashes and blackened eyebrows. This juxtaposition illustrates how Umayyad art both draws from and transforms classical iconography to articulate a culturally specific ideal of feminine beauty and power.

The portrayal of women as escorting figures or dominant figures, as exemplified by the ‘bathing beauty’ in Qusayr Amra, serves to obscure the distinction between the spiritual sphere and the tangible world, thereby reinforcing the Quranic depiction of heaven. However, it is also crucial to consider the likelihood that these depictions are influenced by contemporary women of that era. It is therefore important to consider whether the depictions in Qusayr Amra represent the sole manifestation of such imagery or if they are connected to other artistic creations of the Umayyad period. Exploring these interrelations is key to understanding the complex visual language that navigates between symbolic and real-world female representations. These stylistic choices, possibly reflecting contemporary ideals of womanhood, likely influenced the patron’s and artists’ motivations in portraying female visibility.

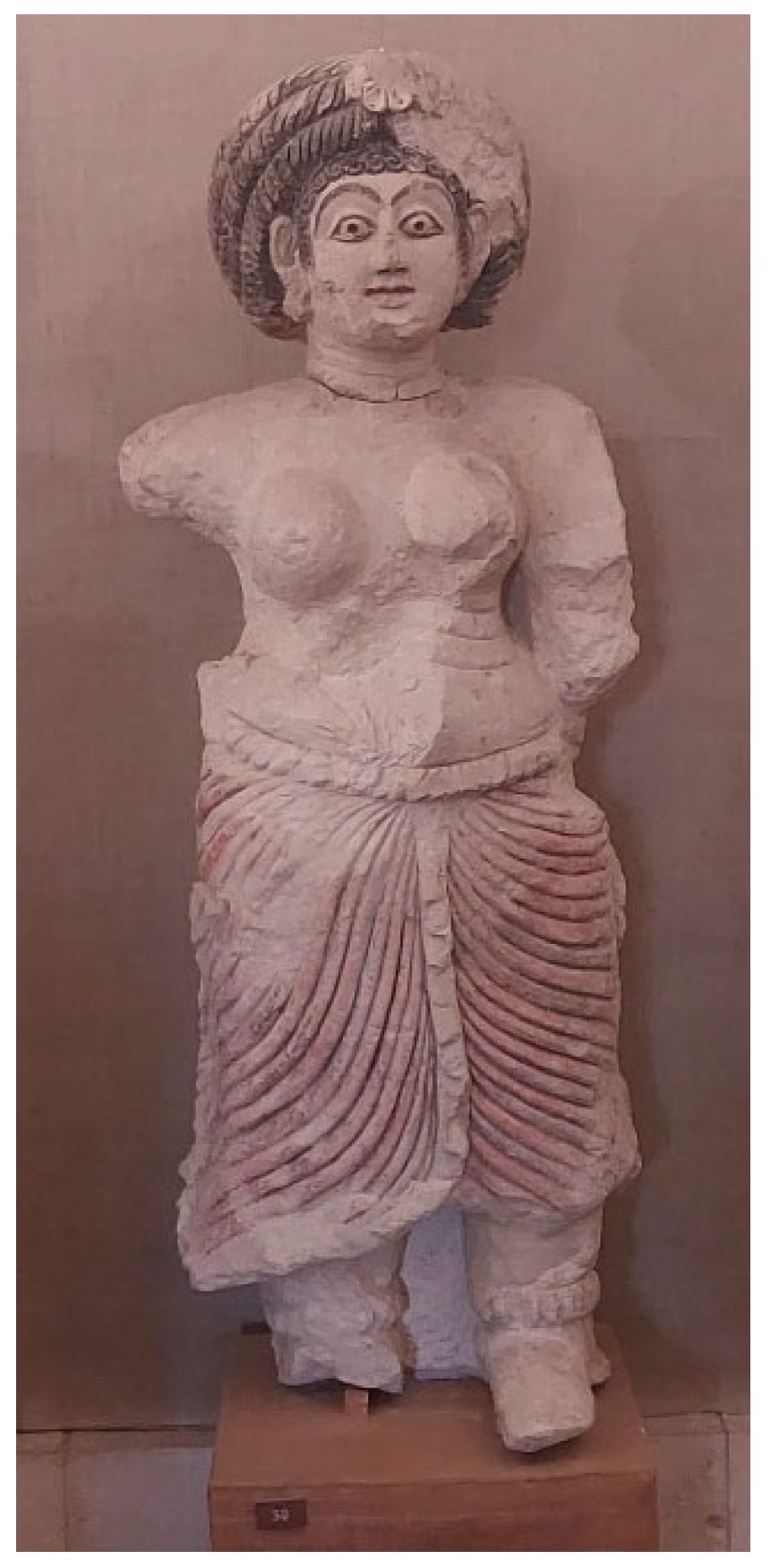

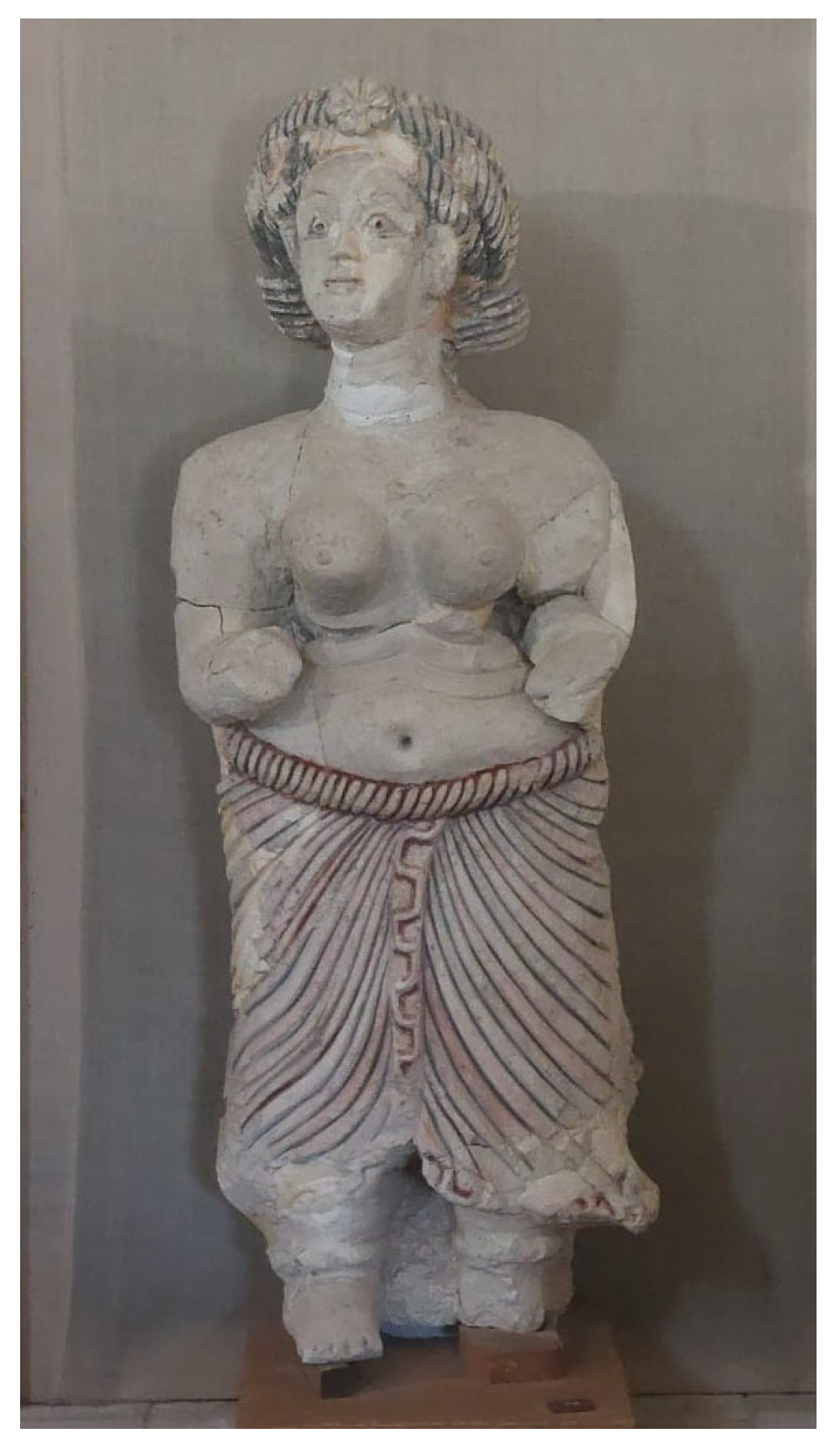

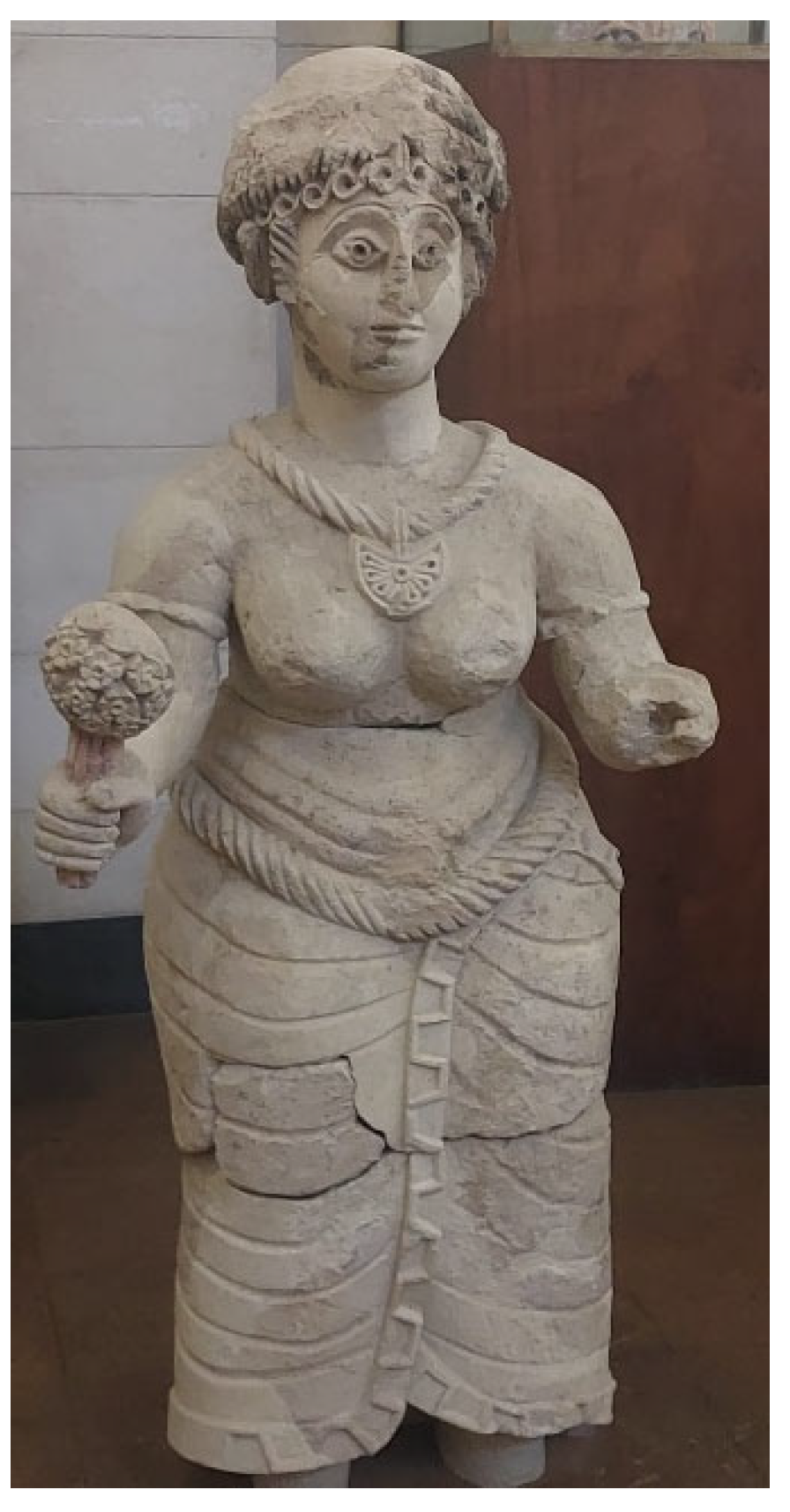

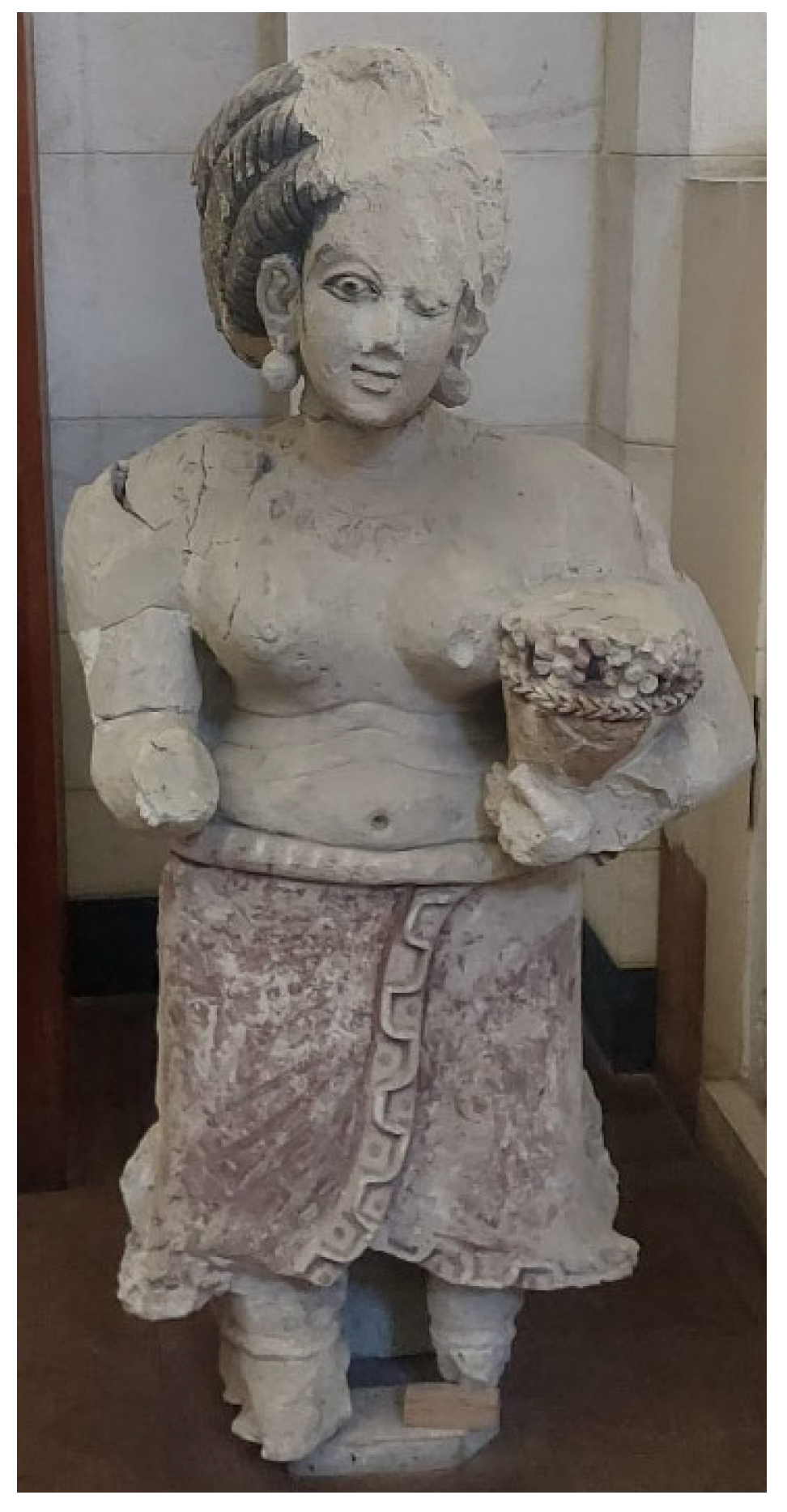

In order to achieve a more comprehensive understanding of the visual representation of women in Islamic art, it is necessary to consider not only the influence of external cultures but also the various female representations found in the visual arts of the Umayyad dynasty. An examination of the female depictions in the Umayyad palace at Khirbat al-Mafjar (Jericho) by Hanna Taragan, an Islamic art researcher, revealed a diversity in the portrayal of Umayyad women. Taragan’s analysis focused on four well-preserved female figures, stucco statues from the Umayyad palace in Mafjar, and she proposed reasonable sources that influenced their creation. The sculptures (

Figure 16,

Figure 17,

Figure 18 and

Figure 19) depict women with rounded breasts, three folds adorning the belly area, and a fabric rope encircling the hips to accentuate the narrow waist and broad hips that are characteristic of Umayyad women. The figures’ attire consists of a long, tight skirt that encloses their legs, their hair is designed and bound with braids that wind around the head, and they are decorated with numerous jewels that accentuate their sensuality (

Taragan 2001, p. 69).

Taragan’s argument asserts that, despite the uniqueness of each female figure, they bear a “family resemblance” that is primarily evident in their body structure and plump facial features. This resemblance is further accentuated by the prominence of their eyes and eyelids, which sweep over the eyeballs, forming a distinctive black eyebrow. A pivotal issue that Taragan addresses in her article is the relationship between the varied interpretations of female representation and their alignment with contemporary Umayyad women. Taragan presents numerous examples from different geographical areas that contribute to the contemporary understanding of how women were described and why they were depicted in this manner. While comparing these representations to the female figures in Qusayr Amra, such as the bathing beauty, there are several resemble feminine elements that are prominent. The shape of the hair, the jewelry, the round breast and the wide hips are all parallel. These stylistic choices that might be a presentation of contemporary women and womanhood, can explain the motivation behind the patron or the craftsmen’s depictions of this external visibility is a subject of interest.

An important example in Taragan’s article comes from Coptic art, which flourished in Egypt, one of the areas the Umayyads conquered. Coptic art was a local expression of the clash between Orientalist and classic art. Within this artistic milieu, women are predominantly depicted in textile products. The Coptic fabrics examined by Taragan, dating to the 5th–6th centuries, feature female figures positioned within arches (

Figure 20). These figures are characterized by prominent, rounded breasts, defined waists, and broad hips. Some figures exhibit crossed legs, while others hold one hand up and the other down. The depiction of stomach folds is subtle, and all figures are adorned with necklaces bearing oversized medallions. Taragan’s hypothesis suggests that female figures accompanied by floral attributes correspond with the depiction of the Maenads escorting Bacchus, as found in Hellenistic tradition (

Taragan 2001, p. 72). The presentation of women as escorting figures or as dominant figures, as seen in the bathing beauty depicted in Qusayr Amra, serves to blur the distinction between the spiritual sphere and the real world, thereby reinforcing the connotation of heaven. Additionally, it establishes an alternative, valid association with the Dionysus (Bacchus in Roman mythology) scene cycle.

Fowden’s writing regarding the statue of Aphrodite from Amman contains only references to the body description. However, a more thorough examination of this founding might elucidate the significance of Islamic textual sources and their impact on the anatomical descriptions in Qusayr Amra. Taragan’s seminal work highlighted the predominance of passages from the Quran and Hadith, particularly those concerning women and the female body, within descriptions of Paradise (

Taragan 2001, p. 75). Building upon this seminal work, Taragan further explores the depiction of contemporary women in Hadith and Jahallic poetry, underscoring the sensuous and erotic appeal attributed to women in these sources. The Hadith provides elaborate descriptions of the women’s faces: “Their faces are fair, their complexion is radiant, their teeth are dazzling like the divine light. Their hair is emphasized, as are their arched black eyebrows and alluring long lashes. Diaphanous fabrics reveal the sinuous outlines of their bodies, and they are anointed with the scents of saffron, must, camphor, and amber. Their arms are adorned with gold bracelets, their fingers with rings, and their toes with precious stones and pearls.” (

Taragan 2001, p. 75, citing El Saleh 1986, pp. 38–39).

The literal description of Taragan’s examination is of particular importance in understanding the representation of the female figure in Qusayr Amra. This historical contrast between visual traditions is not merely descriptive; it reveals a deeper cultural transformation in how femininity, sensuality, and power were imagined in the Umayyad period. This representation can be understood on two levels. First, it highlights the fundamental difference between ancient beauty standards and those constructed during the Umayyad period. The Aphrodite statue, when combined with the aforementioned descriptions, creates an essential difference between early Islamic art and Umayyad art. This contrast underscores not only a divergence in bodily esthetics—from the harmonious proportions and subdued eroticism of Greco-Roman goddesses to the voluptuous, adorned, and sensually described Umayyad women—but also a shift in the theological and cultural values embedded in those representations. Secondly, these descriptions reveal more details regarding women’s social status. These nuances render the description erotic, thus highlighting the male gaze and the requirement for women to participate in the narrative.

This representation is found in Qusayr Amra and the Umayyad palaces, prompting numerous inquiries concerning the depiction of the female body. Modern theories addressing the male gaze and its variations based on cultural, geographical, and environmental factors can offer insights into the portrayal of women in the palaces. Taragan’s use of John Berger’s seminal work ‘Ways of Seeing’ (1972) is particularly illuminating. Berger’s assertion that “Men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at” underscores the power dynamics at play. This dynamic affects not only the relations between men and women but also the relationship between women and themselves. The male gaze, Berger contends, becomes the surveyor of the woman in herself, and the surveyed female becomes an object of vision, a sight. This quote examines the relations between the men in the complex and the women in it, as well as the women’s relationship to themselves. The women are unaware of their power and body and act as sexual objects in the hands of the patron. This declaration unsettles women’s social status rather than talking about professional women: dancers, singers, or even enslaved people. The depiction of women in the palace serves as direct evidence of the patron’s ownership of women and the patriarchal perception that characterizes descriptions in the complex.

3. Conclusions

The depictions of female figures within the Qusayr Amra bathhouse complex provide a rich tapestry for understanding the complex interplay between artistic tradition, religious symbolism, and societal norms in early Islamic art. These representations reflect a blend of influences from Greco-Roman mythological traditions and Islamic religious texts, offering a nuanced perspective on the relationship between the spiritual and the physical worlds. The deliberate distortion of anatomical proportions, combined with motifs of divine adornment and sensuality, signals a conscious engagement with contemporary ideals of beauty, femininity, and sexuality. However, these depictions are not merely esthetic; they are also culturally and politically charged, reinforcing the Umayyad rulers’ authority and their vision of the afterlife, as reflected in the Quranic descriptions of paradise. The incorporation of secular and divine elements within the visual narratives of Qusayr Amra ultimately serves to blur the lines between religious and worldly power, presenting an image of the female form that is both a symbol of divine beauty and a projection of male desire.

Furthermore, these portrayals contradict contemporary conceptions of modesty and purity as delineated in the Quran and Hadith. Yet, certain figures—such as the clothed and passive Ariadne—appear to incorporate visual elements aligned with emerging Islamic ideals. This particular adaptation of classical motifs is indicative of a multifaceted engagement with prior artistic traditions, as well as a deliberate reshaping of these motifs in accordance with the evolving religious and cultural ethos. This tension suggests that the patron of Qusayr Amra sought to establish a paradisiacal vision where the female form simultaneously embodied divine allure and satisfied the desires of the male gaze. Consequently, the bathhouse functions as a space where visual pleasure, spiritual longing, and political imagination intertwine in a utopian fantasy.

A renewed examination of the central image that draws on the myth of Dionysus and Ariadne reveals its significance within the fresco assemblage. This image adeptly synthesizes two elements, the Islamic practice of modesty and the Umayyads’ deliberate selection of artistic motifs, including erotic depictions of women, to create a layered narrative that contrasts earthly pleasures with the imagined pleasures of the afterlife. While Walid II’s lifestyle was public knowledge, it did not negate his adherence to Islamic beliefs. The thoughtful integration of Quranic verses into the visual language of the bathhouse artist reveals a masterpiece that honors religious texts and values. However, modern interpretation of the frescoes at Qusayr Amra remains contentious, as it is shaped by diverging scholarly methodologies and interpretive frameworks.

As previously discussed, Walid II’s character and influence are central to understanding the iconography of Qusayr Amra. While his unconventional lifestyle undoubtedly influenced the decoration of the complex, it is important to note that the diversity of the subjects depicted cannot be reduced to an expression of his personal tastes. Instead, Walid II’s patronage must be viewed as a period that expanded the boundaries of artistic possibilities, drawing on a broad range of visual traditions influenced by cultural exchanges. Walid II’s patronage is known to have encouraged experimentation among the artists, marking the Umayyad adaptation to diverse influences. However, this experimentation may have initially led to feelings of alienation among Muslim observers, particularly given the fusion of these innovations with established artistic traditions.

This sense of foreignness could have led some to believe that the artists of Qusayr Amra were of Western origin. However, a thorough examination of the iconographic resources prevalent in the Umayyad period reveals that the artists were not only well-versed in Islamic texts but also strategically selected motifs that defined the Umayyad Khalifah as the legitimate heir to the region. Consequently, Qusayr Amra presents a complex world of multiple pleasures—earthly and heavenly. While these pleasures were grounded in reality, the bathhouse’s uniqueness lay in its ability to transcend mere representation and engage with a visionary realm of possibilities.

This article opens many avenues for further research, especially with regard to how the images in the complex interact with one another and the broader social, religious, and artistic contexts. Future investigations could integrate modern theories on gender, nudity, identity, and Muslim history, providing insights into how Umayyad art preserved ancient traditions while also pioneering new visual language. A more sustained focus on the female figures—clothed and unclothed alike—can illuminate how these representations functioned within a shifting visual culture, shaped by religious, poetic, and pre-Islamic traditions alike. The bathhouse of Qusayr Amra, with its sophisticated blend of cultural and religious elements, stands as a testament to remarkable artistic intelligence and imagination. Given the complexity of these images and their connections, further research is essential to fully uncover their meaning and significance within the broader context of Umayyad art.