From Shared RE to a Shared Digital RE Strategy: Navigating the Post-Digital Transformation of RE Organizations—Results of a Swiss Participatory Research Project

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Welcome to a Culture of Networking and Sharing: (Inter-)Religious Adult Education in a Post-Digital Culture

2.1. Recent Development Lines in Digital Society: A Narratological Ramp to the Present Day

2.2. The Consequences of Digital Culture for Religious Adult Education

- The religion-related (theological, sociological, psychological) field: particularly the transforming dimensions of power distribution and positionality;

- The general educational field: fundamental transformations of teaching and learning processes in a digital society;

- The (educational) organizational and organizational psychology field: the organizational level of digital transformation.

2.2.1. The Religion-Related Perspective: Redistribution of Power and “Diversification of Religious Substance”

2.2.2. The General Educational Perspective: Digital Education as Its Own Didactic Form

2.2.3. The Organizational Level of Education-Related Digital Transformation: A Research Gap

3. Results from a Swiss Participatory Research Project

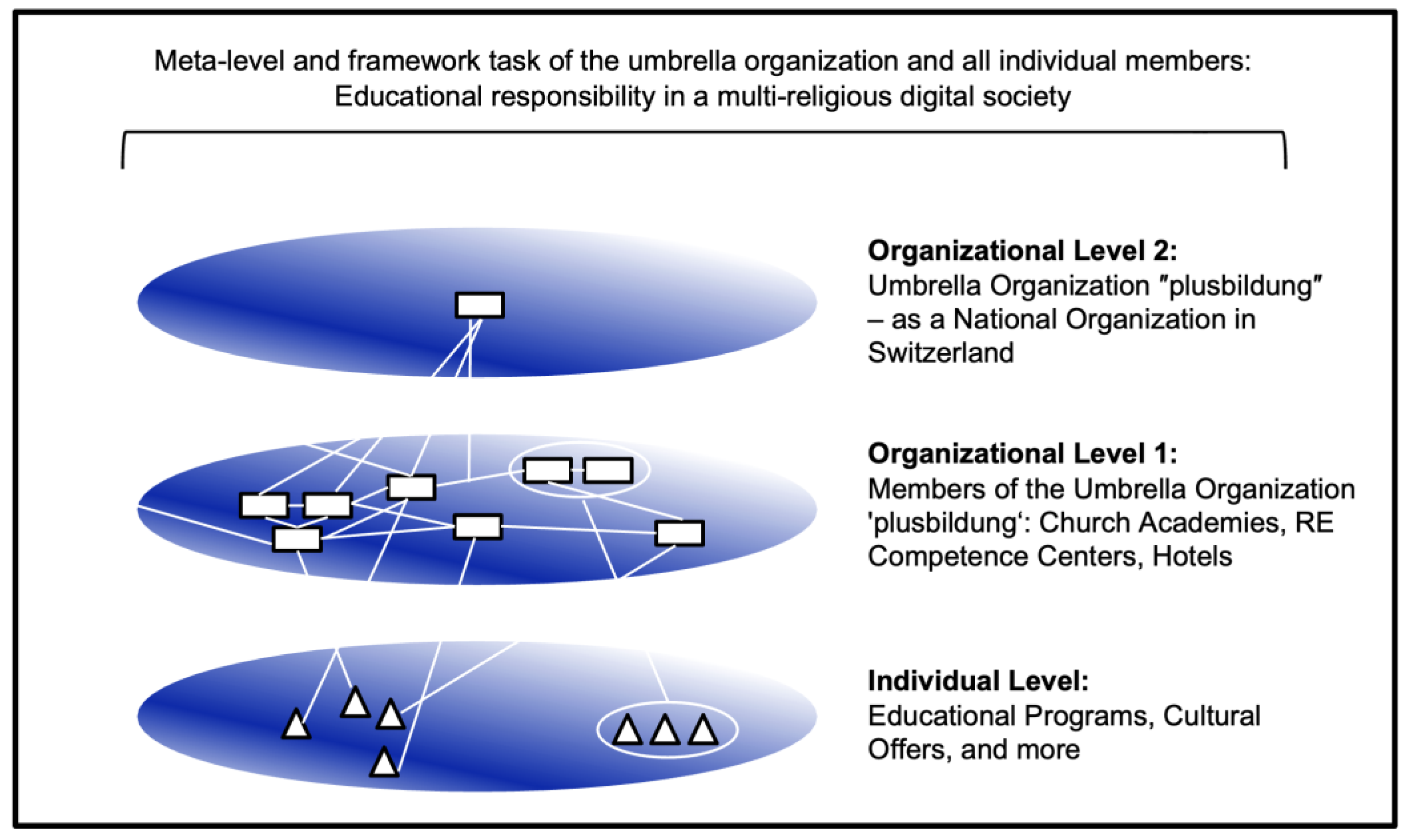

3.1. The Umbrella Association “Plusbildung”

- The individual level of action pertains to the specific cultural and educational offerings of the individual organizations. Here, the primary actors are the teachers and learners.

- The organizational level of action is relevant to the umbrella association “plusbildung” in two respects:

- ○

- Firstly, the members of the umbrella association are independent organizations (organizational level 1);

- ○

- Secondly, the umbrella association itself is a national organization (organizational level 2).

3.2. Research Design and Progress

- A case study at a representative member organization, specifically focusing on one of its digital education modules (participant observation and individual interviews with participants of this educational module);

- A quantitative-exploratory online survey;

- Qualitative expert interviews with teachers and leaders of the member organizations;

- Web scraping and topic modeling of all websites of the member organizations of the umbrella association “plusbildung” (Schneider 2024).

3.3. Research Questions

- What are the most significant factors influencing the intent to offer/use religiously themed digital educational offerings? That is, who uses and who offers digital RE services at “plusbildung”? Why?→ The dual focus of this question illustrates that motivations for digital educational offerings shall be analyzed by comparing “offering” and “using”. The operationalization of this research question considers both specifically digital aspects and the content orientations of the educational offerings.

- What are the influencing factors for good practice experiences with digital/hybrid RE offerings? That is, which digital offerings are perceived as successful by teachers and learners? Why?→ The focus here lies on the quality of learning processes, the experience, or the assessment thereof with regard to digital educational offerings. There was significant interest from co-researchers in how learning through encounter and dialogical learning in digital settings may be perceived as successful, given that this type of education particularly applies to the umbrella association (regarding dialogical learning as a specific feature of religious education cf. Nelson 2018). This question again has a dual focus, as it captures the experiences and assessments of both providers and users. The operationalization of this research question incorporates different aspects of both successful and unsuccessful practical experiences.

- What are the factors influencing the willingness of individual member organizations to see digitalization as a call for shared strategies and further joint development? That is, what next?→ This research question focuses on the assessments of “experts by experience” regarding potential future opportunities for a joint, shared strategy. Organizational action levels 1 and 2 and their interplay are considered here.

- The term “digital” also includes hybrid offerings. For pragmatic reasons, the study does not explicitly distinguish between different forms of digital teaching and learning processes.

- The questions illustrate that three different perspectives are included: This decision was based on recent research findings and the interest of the umbrella organization’s members, to collect the voices of three groups: learners, teachers, and leaders.

- Three languages: The quantitative survey was conducted in three languages (German, French, and Italian).

- Ecumenical approach: The study is both personnel-wise and content-wise ecumenically oriented: Both researchers and co-research partners belong to different denominations (and in some cases different religions); the theoretical background of the study and the umbrella association are ecumenically grounded. This decision does not deny denominational differences but reflects the willingness of denominations to cooperate and the perceived necessity by the co-researchers for ecumenically shared strategies.

3.4. Online Survey Results

3.4.1. Questionnaire Design

- For the Employees: A comprehensive version (duration: approx. 25 min) intended for employees of the member organizations of the umbrella group, targeting the two stakeholder groups, leaders and teachers. A specific question at the beginning of the questionnaire facilitated an additional distinction between these groups in data analysis

- For the Learners: A shorter version (duration: approx. 12 min) intended for participants in educational modules, i.e., the learners. This abbreviated version mirrors the comprehensive one but leaves out several questions. Additionally, some of the phrasings in the shorter version were modified to focus on the utilization of an educational offering rather than its provision.

- Part I: Sociodemographic data including religiosity, church proximity, and educational intentions in educational settings in general. The items on religiosity and church proximity were derived from validated instruments for religiosity (Bertelsmann Stiftung 2009).

- Part II: Digital competencies and educational intentions as well as experiences in digital contexts. The items on digital competencies were adapted from validated instruments for assessing the digital competencies of teachers (Vuorikari et al. 2022; Redecker and Punie 2017) and tailored to the context of RE. Educational intentions in Parts I and II were captured using various items (see operationalization notes below).

- Part III: Reasons for cooperation and future assessments concerning adult RE. These items were developed in reference to recent research findings (Bröckling et al. 2021) and in collaboration with various members of the umbrella organization “plusbildung”.

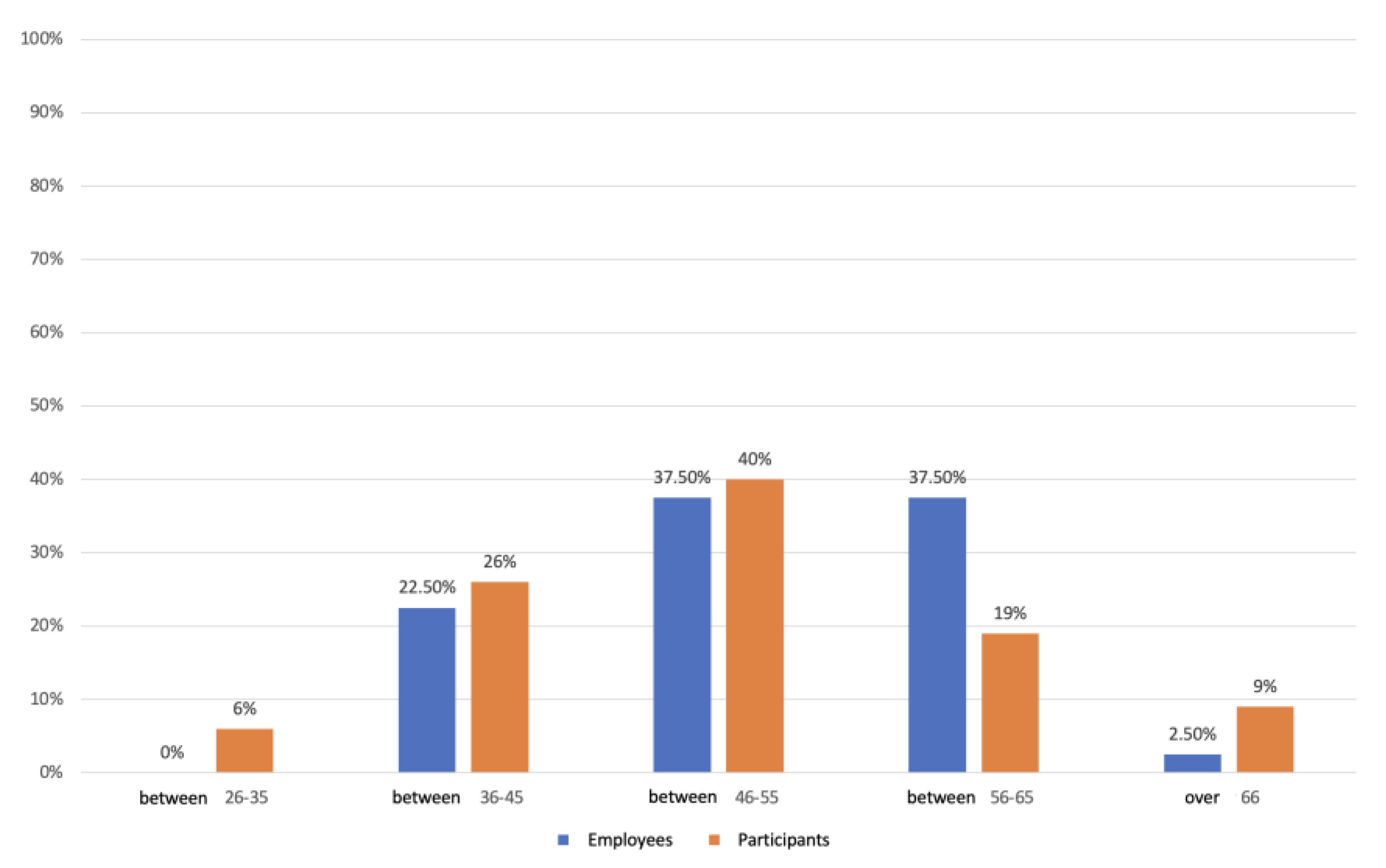

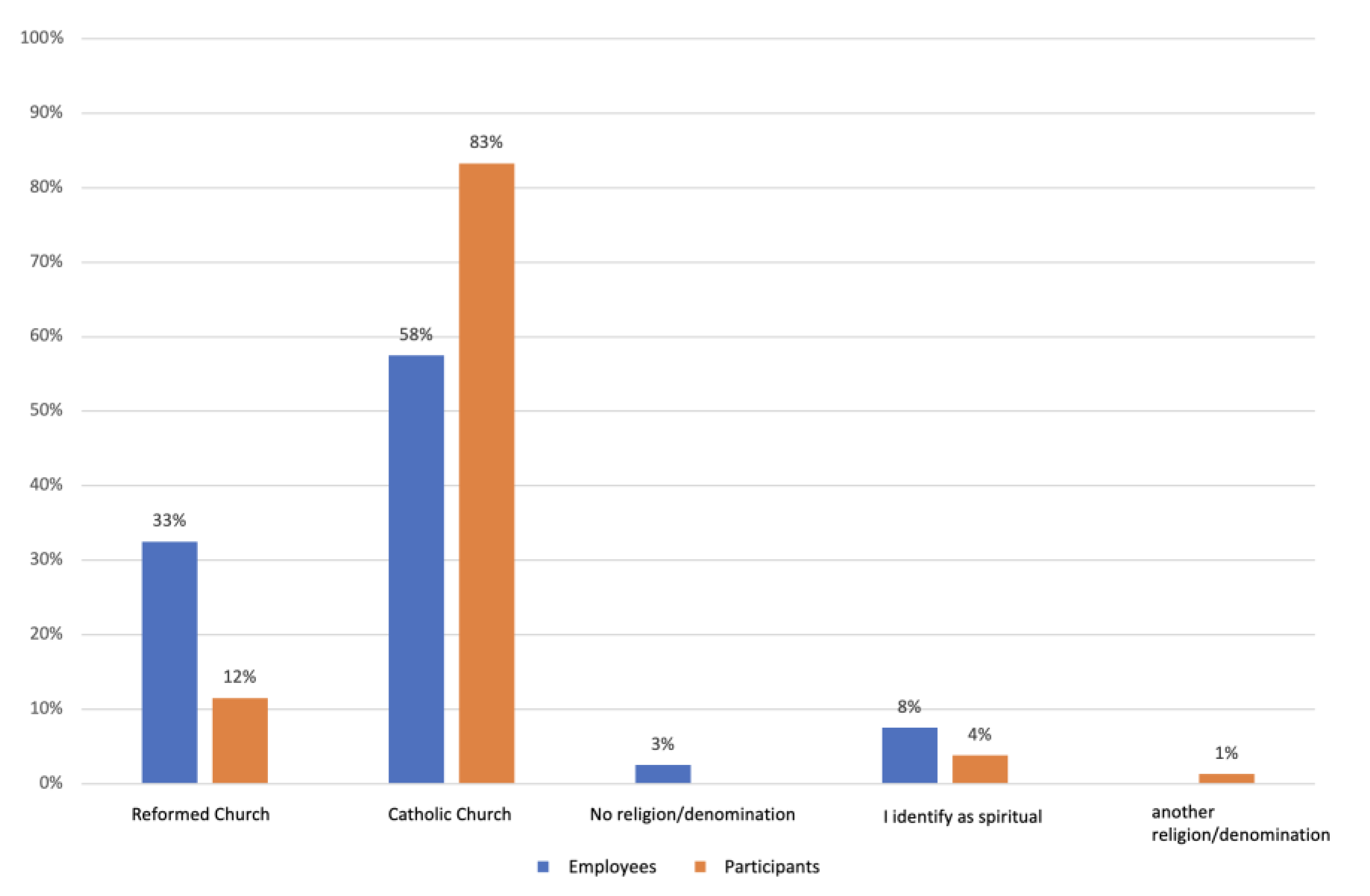

3.4.2. General and Sociodemographic Results

3.4.3. Mind the Gap: Between Encounter-Based and Digital Learning

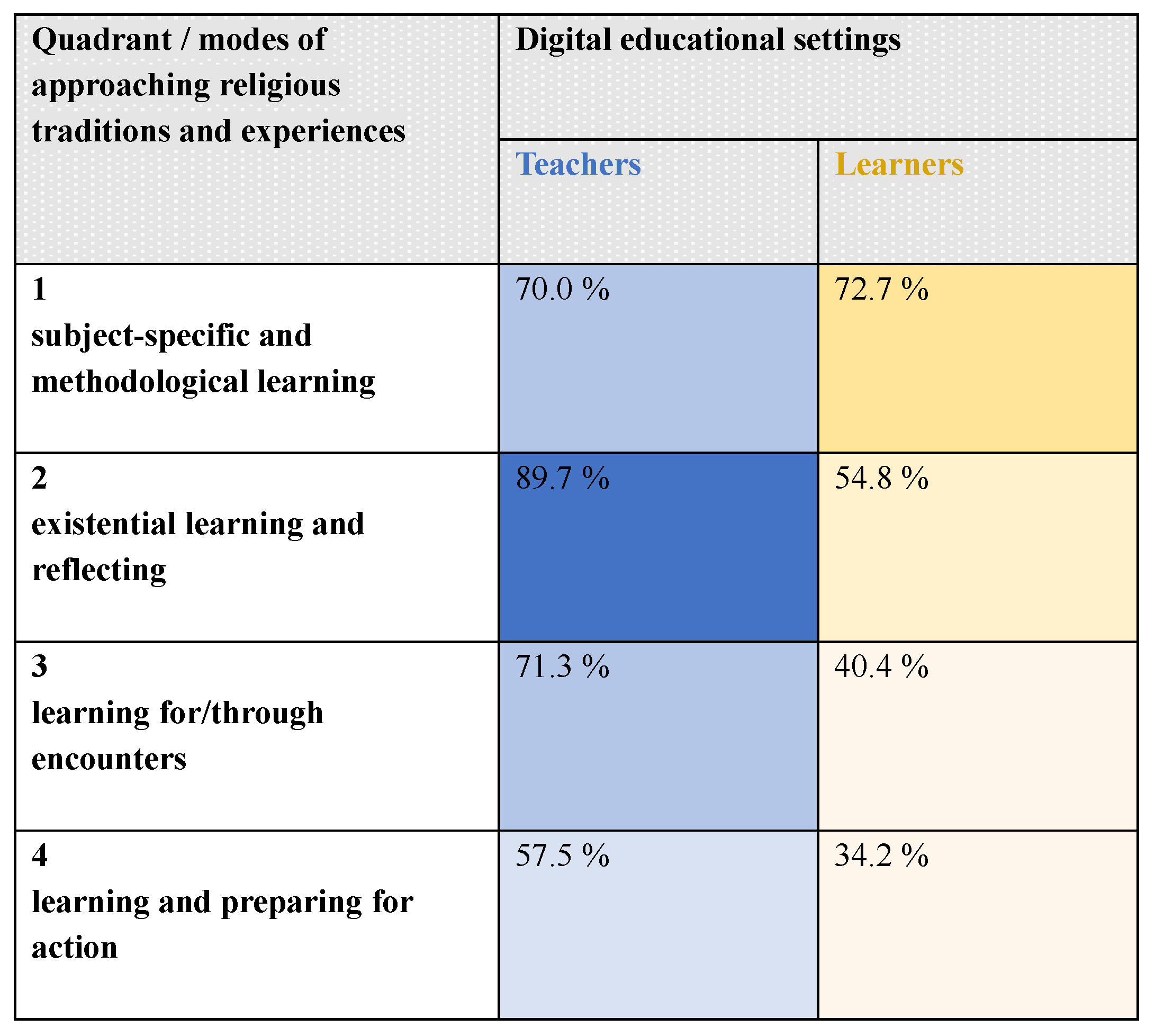

- The first mode, hereafter referred to as “subject-specific and methodological learning”, refers to the ideal profile of a scholar of religious studies, initially concerned with the objective perception and interpretation of phenomena, statements, and sources in general. The particular hermeneutic emphasis is on scientific objectivity.

- The second mode, hereafter referred to as “existential learning and reflecting”, puts the focus on the ideal profile of the existential thinker. The particular hermeneutic emphasis is on personal reflection, which leads to the reconsideration or first emergence of one’s own positioning and is expressed verbally or otherwise creatively.

- The third mode, hereafter referred to as “learning for/through encounters”, refers to a situation-sensitive, socially and ethically justified handling of religion-specific situations. It encompasses both socio-practical and hermeneutical skills that are to be developed. This mode includes not only encounters in everyday situations where religious topics play a role but also behavior in “indirect” encounters with religious representatives and religious artifacts in the classroom. This mode also applies to general religious education; however, it should be specified here that the term encounter-based learning—learning through encounter, in dialog—is important, that is, not only in contact with traditions but also with experiences.

- The fourth mode focuses on the “‘glocal”’ actor, hereafter referred to as “learning and preparing for action”. The particular hermeneutic focus is on understanding social interactions between one’s personal world—school, region, entire environment—and (inter-)religious challenges and implies a regional or geographically broader interest that also intersects with sociopolitical issues. Regarding general RE, this mode can be divided into religious-community-specific engagement and general engagement.

- The primary focus of the teachers is on Quadrant 3, with a strong tendency of agreement at 90.8%. The second-highest focus is on Quadrant 1, with a 78.2% tendency of agreement. Quadrants 4g (72.5%), 2 (64.1%), and 4e (54.1%) show lower levels of agreement.

- The primary focus of the learners is on Quadrant 1, with a strong tendency of agreement at 87.1%. The second-highest focus is on Quadrant 3, with a 78.3% tendency of agreement. Quadrants 4e (69.3%), 2 (64.4%), and 4g (60.5%) show lower levels of agreement.

- The primary focus of teachers here is on Quadrant 2, with a strong agreement of 89.7%. The second highest focus is on Quadrant 3, with a 71.3% agreement. Quadrants 1 (70%) and 4 (57.5%) have lower ratings.

- According to learners’ perception, the primary focus is on Quadrant 1, with a strong agreement of 72.7%. The second highest focus is on Quadrant 2, with a 54.8% agreement. Quadrants 3 (40.4%) and 4 (34.2%) have lower ratings.

- In digital teaching and learning settings, the aforementioned general result for teachers shifts significantly (consciously or not): from encounter-based learning (90.8%) and academic-methodical learning (78.2%) to existential learning (89.7%) and, to a lesser extent, encounter-based learning (71.3%).

- There is also a clear difference in the perception between teachers and learners: The two modes primarily mentioned by employees (leaders and teachers) as their intention in digital settings are precisely those that learners rate significantly lower than employees (existential learning: 54.8%; encounter-based learning: 40.4%).

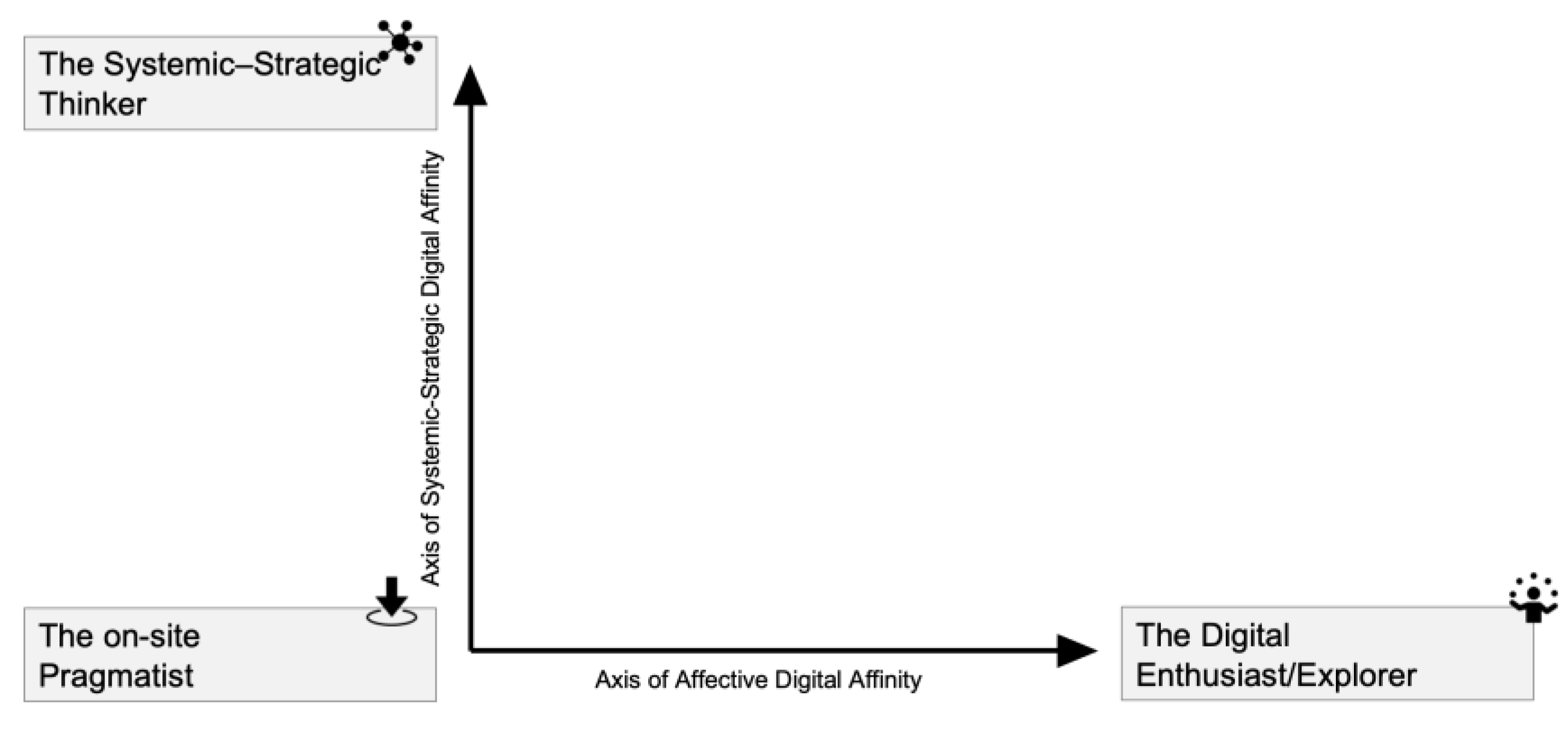

3.4.4. Two Axes of RE-Related Digital Affinity

- The On-Site Pragmatist: Digital education? “It is a hassle”. But where it is necessary, I will do it. Until I can return to in-person activities, which is the real thing.

- The Digital Enthusiast/Explorer: I enjoy “using digital tools, media, and platforms”. So, I experiment with them in education as well.

- The Systemic–Strategic Thinker: “Digital education? It is essential, not only today but also for the future. This means we must plan systematically and strategically, also conduct research and accompanying studies”.

4. Conclusions and Outlook

4.1. Conclusions

- At the individual level: Here, it is evident that the general main concern of encounter-based, dialogical learning, from the teachers’ perspective, loses relevance and potential in digital spaces, and from the learners’ perspective, it is only marginally successful. Interestingly, this concerns the mode among the four “modes of approaching religious traditions and experiences” that can operate most effectively through “sharing”; encountering is fundamentally about the willingness to share and to enable participation. How this “sharing in digital RE” functions best will continuously need to be assessed, depending on contexts such as digital tools, teacher personality, and other relevant factors. A digital strategy for digital religious adult education, as pursued by the umbrella association “plusbildung”, must, in any case, specifically provide and promote methods and tools for this purpose—unless the strategy consciously decides to forgo this primary concern in digital educational settings.

- At a broader level, it was examined what motivates teachers and learners, after the COVID-19 pandemic, to appreciate digital educational settings and consider them a relevant part of future digital religious adult education. More than other expected factors (financial cost, time resources, age, years of professional experience, digital competence), the affective dimension—joy and experimental enthusiasm for digital tools—is a significant predictor of whether digital educational settings will be offered or used in the future. This affective factor primarily influences actions at the “individual level” within specific educational settings. At the organizational level, it also seems to depend, additionally, on the type of employees and whether their forward-thinking is systemic. This relationship requires additional investigation from the perspectives of individual psychology (systemic thinking as a personality feature) and organizational psychology (strategy and cooperation willingness) (Church et al. 2015) and needs then to be adapted to RE contexts.2

4.2. Sharing as a Specific RE and Theological Task

- At the methodological-didactic level, examine the relationship between non-actively initiated but existing digital RE, the proclaimed goals of intentional digital RE processes, and the actual outcomes of the latter, as well as the consequences of potential discrepancies;

- Also at the methodological-didactic level, identify the interplay between non-digital media and digital media and explore which RE goals and competencies are promoted by the use of each;

- At the public-religious-educational level, determine which criteria, from the perspective of “traditional authorities”, are essential for a future-proof RE in digital culture to sharpen one’s profile in the growing market of digitally ubiquitous religious didactic presence;

- At the RE organizational level, determine which criteria, from the perspective of “traditional authorities”, are essential for a future-proof RE to consciously decide, based on which criteria and with which actors, “shared RE” should be actively pursued;

- At the practical-theological level, consider what a proactive theologically responsible stance looks like regarding the possibilities and impossibilities of sharing in the digital space, especially regarding power dynamics in the digital space (Müller and Suhner 2023; Müller and Suhner 2023);

- At the theological level, address the normative question of what future is desirable for humanity and which spaces theology, as a critical humanities discipline, must and can occupy; also, determining by what spirit a theologically, pedagogically, inter-religiously responsible RE is carried—and how this spirit may be credibly expressed.

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | The direct quotes for these typology concretizations are items from the quantitative data collection, while the subsequent formulations are paraphrases from the interviews with the teachers. |

| 2 | In this regard interesting in intention—though unfortunately less in execution—e.g., (Bashori et al. 2020). |

References

- Aigrain, Philipp. 2012. Sharing. Sharing Culture and the Economy in the Internet Age. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Barlow, John Perry. 1996. A Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace. Available online: https://www.eff.org/cyberspace-independence (accessed on 11 August 2024).

- Bashori, Bashori, Muhammad A. M. Prasetyo, and Edi Susanto. 2020. Change Management Transfromation (sic!) in Islamic Education of Indonesia. Social Work and Education 7: 72–84. [Google Scholar]

- Bergold, Jarg, and Stefan Thomas. 2012. Participatory research methods: A methodological approach in motion. Historical Social Research/Historische Sozialforschung 37: 191–222. [Google Scholar]

- Bertelsmann Stiftung. 2009. Woran glaubt die Welt? Analysen und Kommentare zum Religionsmonitor 2008. Gütersloh: Verlag Bertelsmann Stiftung. [Google Scholar]

- Bhabha, Homi K. 1990. Interview with Homi Bhabha. In Identity: Community, Culture, Difference. Edited by Homi K. Bhabha. London: Lawrence and Wishart, pp. 207–21. [Google Scholar]

- Bröckling, Guido, Julia Behr, and Julian Erdmann. 2021. #ko.vernetzt: Digital Transformation of an Educational Organization from a Media Educational Viewpoint. In Digital Transformation of Learning Organizations. Edited by Dirk Ifenthaler, Sandra Hofhues, Marc Egloffstein and Christian Helbig. Cham: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, Heidi. 2007. Who’s Got the Power? Religious Authority and the Internet. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 12: 43–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, Heidi. 2012. Understanding the Relationship between Religion Online and Offline in a Networked Society. Journal of the American Academy of Religion 80: 64–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castells, Manuel. 2000. The Rise of the Network Society. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Castells, Manuel. 2010. The Information Age: Economy, Society and Culture. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Cheong, Pauline Hope, Shirlena Huang, and Jessie P. H. Poon. 2011. Cultivating Online and Offline Pathways to Enlightenment. Information, Communication & Society 14: 1160–80. [Google Scholar]

- Church, Allan H., Christopher T. Rotolo, Alyson Margulies, Matthew J. Del Giudice, Nicole M. Ginther, Rebecca Levine, Jennifer Novakoske, and Michael D. Tuller. 2015. The Role of Personality in Organization Development: A Multi-Level Framework for Applying Personality to Individual, Team, and Organizational Change. In Research in Organizational Change and Development. Edited by Abraham B. (Rami) Shani and Debra A. Noumair. Leeds: Emerald Group Publishing Limited, vol. 23, pp. 91–166. [Google Scholar]

- Cloete, Anita L. 2016. Mediated Religion: Implications for Religious Authority. Verbum et Ecclesia 37: a1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dachverband “plusbildung”. 2019. Jahresbericht 2019. Available Directly from the Umbrella Organization Upon Request. Available online: https://plusbildung.ch/d/ueber-uns/was-ist-plusbildung/ (accessed on 11 August 2024).

- Dachverband “plusbildung”. 2024. Was Ist ‘Plusbildung’? ‘plusbildung’—Ökumenische Bildungslandschaft Schweiz. Available online: https://plusbildung.ch/d/ueber-uns/was-ist-plusbildung/ (accessed on 11 August 2024).

- Deleuze, Gilles, and Félix Guattari. 2004. A Thousand Plateaus. London and New York: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dörner, Olaf, and Stefan Rundel. 2021. Organizational Learning and Digital Transformation: A Theoretical Framework. In Digital Transformation of Learning Organizations. Edited by Dirk Ifenthaler, Sandra Hofhues, Marc Egloffstein and Christian Helbig. Cham: Springer, pp. 61–76. [Google Scholar]

- Duffy, Gavin, and Tony Gallagher. 2017. Shared Education in contested spaces: How collaborative networks improve communities and schools. Journal of Educational Change 18: 107–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evolvi, Giulia. 2020. Materiality, Authority, and Digital Religion. Entangled Religions 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floridi, Luciano. 2015. Die 4. Revolution. Wie die Infosphäre unser Leben verändert. Berlin: Suhrkamp Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Flusser, Vilém. 2009. Kommunikologie Weiter Denken. Frankfurt a. Main: Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Global Data. 2022. Education Technology (EdTech) Market Size, Share and Trends Analysis Report by Region, End User. Available online: https://www.globaldata.com/store/report/edtech-market-analysis/#:~:text=The%20Education%20Technology%20(EdTech)%20market,16.0%25%20during%202022%2D2026 (accessed on 11 August 2024).

- Grant, Aj. 2020. Digital tribalism and the internet of things: Challenges and opportunities. Issues in Information Systems 21: 213–20. [Google Scholar]

- Green, Laurie. 2009. Let’s Do Theology. London and New York: Bloomsbury Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Byung-Chul. 2016. Die Austreibung des Anderen. Frankfurt a. M.: S. Fischer Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Haraway, Donna. 1985. Manifesto for Cyborgs: Science, Technology, and Socialist Feminism in the 1980’s. Socialist Review 80: 65–108. [Google Scholar]

- Ifenthaler, Dirk, and Marc Egloffstein. 2020. Development and implementation of a maturity model of digital transformation. TechTrends 64: 302–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kergel, David. 2020. The History of the Internet. In Handbook of Theory and Research in Cultural Studies and Education. Edited by Peter Pericles Trifonas. Cham: Springer, pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Kołodziejska, Marta, and Anna Neumaier. 2017. Between individualisation and tradition: Transforming religious authority on German and Polish Christian online discussion forums. Religion 47: 228–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kümmel, Elke, Johannes Moskaliuk, Ulrike Cress, and Joachim Kimmerle. 2020. Digital Learning Environments in Higher Education: A Literature Review of the Role of Individual vs. Social Settings for Measuring Learning Outcomes. Education Sciences 10: 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leirvik, Oddbjørn. 2020. Pluralisation of Theologies at Universities. Approaches and Concepts. In Pluralisation of Theologies at European Universities (Religions in Dialogue 18). Edited by Wolfram Weisse, Julia Ipgrave, Oddbjørn Leirvik and Muna Tatari. Münster and New York: Waxmann Verlag, pp. 25–34. [Google Scholar]

- Mercer, Calvin, and Tracy J. Trothen. 2021. Religion and the Technological Future. An Introduction to Biohacking, Artificial Intelligence, and Transhumanism. Cham: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, Karlo. 2021. Religion, Interreligious Learning and Education. Berlin: Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, Sabrina, and Jasmine Suhner. 2023. Jenseits der Kanzel. (M)achtsam Predigen in Einer Sich Verändernden Welt. Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirchner Verlag, (English version: Müller, Sabrina, and Jasmine Suhner. 2024. Beyond the pulpit. Leiden: Brill. t.b.p.). [Google Scholar]

- Müller, Sabrina, Sarah Demmrich, and Ulrich Riegel. 2021. New monasticism: Accountability in Christian communities. Research on Religious and Spiritual Education 14: 115–30. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, James. 2018. The Case for Dialogical Learning as a Signature Pedagogy of Religious Education. In Values, Human Rights and Religious Education. Edited by Jeff Astley, Leslie J. Francis and David Lankshear. Oxford: Peter Lang, pp. 91–108. [Google Scholar]

- Noller, Jörg. 2022. Didaktik der Digitalität: Philosophische Perspektiven. In Philosophiedidaktik 4.0? Chancen und Risiken der Digitalen Lehre in der Philosophie. Edited by Minkyung Kim, Tobias Gutmann and Sophia Peukert. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 33–44. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. 2016. Innovating Education and Educating for Innovation: The Power of Digital Technologies and Skills. Paris: OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- OSCE. 2020. The Power of Digital Technologies Must Be Harnessed to Counter Hatred Based on Religion or Belief, ODIHR Says. In OSCE News and Press Releases. Available online: https://www.osce.org/odihr/461140 (accessed on 11 August 2024).

- Passey, Don, Denise Leahy, Lawrence Williams, Jaana Holvikivi, and Mikko Ruohonen, eds. 2022. Digital Transformation of Education and Learning—Past, Present and Future. Cham: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Puschmann, Thomas, and Rainer Alt. 2016. Sharing Economy. Business & Information System Engineering 58: 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reckwitz, Andreas. 2006. Das hybride Subjekt. Weilerswist: Suhrkamp Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Redecker, Christine, and Yves Punie. 2017. European Framework for the Digital Competence of Educators: DigCompEdu. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar]

- Rifkin, Jeremy. 2014. The Zero Marginal Cost Society: The Internet of Things, the Collaborative Commons, and the Eclipse of Capitalism. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, Robin. 2020. Post-digitale Bildung. In Was macht die Digitalisierung mit den Hochschulen? Einwürfe und Provokationen. Edited by Marko Demantowsky, Gerhard Lauer, Robin Schmidt and Bert te Wildt. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter Verlag, pp. 57–70. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, Gerold. 2024. Text Analytics for Corpus Linguistics and Digital Humanities. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Serpa, Sandro, Maria José Sá, and Carlos Miguel Ferreira. 2022. Digital Organizational Culture: Contributions to a Definition and Future Challenges. Academic Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies 11: 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shonfeld, Miri, Megan Cotnam-Kappel, Miriam Judge, Carolyn Yeehan Ng, Jean Gabin Ntebutse, Sandra Williamson-Leadley, and Melda N. Yildiz. 2021. Learning in digital environments: A model for cross-cultural alignment. Educational Technology Research and Development 69: 2151–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solahudin, Dindin, and Moch Fakhruroji. 2020. Internet and Islamic Learning Practices in Indonesia. Religions 11: 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stalder, Felix. 2016. Kultur der Digitalität. Berlin: Suhrkamp Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Suhner, Jasmine. 2023. Jugendtheologie und Digitalisierung: Was ist das – und wenn ja, wie viele? In “…dann nützen wir sie auch: Digitalisierung first – Bedenken second“?! Jugendtheologie und Digitalisierung. Edited by Thomas Schlag and Jasmine Suhner. Calw: Kohlhammer, pp. 153–65. [Google Scholar]

- Suhner, Jasmine. 2025. Thinking Hybrid – Thinking Ahead. Der Dachverband ‘Plusbildung’ in Digitaler Gesellschaft. Ein interdisziplinäres Begleitforschungsprojekt im Kontext (inter-)religiöser Erwachsenenbildung. Zürich: t.b.p. [Google Scholar]

- Tracy, David. 1983. Talking about God: Doing Theology in the Context of Modern Pluralism. New York: Seabury Press. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, Fred. 2008. From Counterculture to Cyberculture. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Van Acker, Frederik, Hans van Buuren, Karel Kreijns, and Marjan Vermeulen. 2013. Why Teachers Share Educational Resources: A Social Exchange Perspective. In Open Educational Resources: Innovation, Research and Practice. Edited by Rory McGreal, Wanjira Kinuthia and Stewart Marshall. Vancouver: Commonwealth of Learning and Athabasca University, pp. 177–91. [Google Scholar]

- van Dijck, José, Thomas Poell, and Martijn de Waal. 2018. The Platform Society: Public Values in a Connective World. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Vuorikari, Riina, Stefano Kluzer, and Yves Punie. 2022. DigComp 2.2. The Digital Competence Framework for Citizens—With New Examples of Knowledge, Skills and Attitudes. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar]

- Welsch, Wolfgang. 1999. Transculturality—the Puzzling Form of Cultures Today. In Spaces of Culture: City, Nation, World. Edited by Mike Featherstone and Scott Lash. London: Sage, pp. 194–213. [Google Scholar]

- Welsch, Wolfgang. 2020. Transkulturalität—Realität und Aufgabe. In Migration, Diversität und kulturelle Identitäten. Edited by Hans Giessen and Christian Rink. Berlin: Springer, pp. 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Wittel, Andreas. 2011. Qualities of Sharing and their Transformations in the Digital Age. The International Review of Information Ethics 15: 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Quadrant/Modes of Approaching Religious Traditions and Experiences | Example Item from the Employee Questionnaire |

|---|---|

| 1 subject-specific and methodological learning | How important is the following goal in your educational offering: Participants should be able to view religion from a scientific standpoint. |

| 2 existential learning and reflecting | How important is the following goal in your educational offering: Participants should be able to develop their own religious identity. |

| 3 learning for/through encounters | How important is the following goal in your educational offering: Participants should learn to approach members of different religions openly. |

| 4 Learning and preparing for action In this quadrant, the study made an additional differentiation beyond Meyer between:

| How important is the following goal in your educational offering: Participants should learn to engage with (inter-) religious issues in society. |

| Using digital tools, media, and platforms brings joy. | Feeling more present in digital events | Memory of digital events is less vivid | ||

| Using digital tools, media, and platforms brings joy. | Pearson Correlation | 1 | 0.491 ** | −0.423 ** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| Feeling more present in digital events | Pearson Correlation | 0.491 ** | 1 | −0.499 ** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| Memory of digital events is less vivid | Pearson Correlation | −0.423 ** | −0.499 ** | 1 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Suhner, J. From Shared RE to a Shared Digital RE Strategy: Navigating the Post-Digital Transformation of RE Organizations—Results of a Swiss Participatory Research Project. Religions 2024, 15, 1000. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15081000

Suhner J. From Shared RE to a Shared Digital RE Strategy: Navigating the Post-Digital Transformation of RE Organizations—Results of a Swiss Participatory Research Project. Religions. 2024; 15(8):1000. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15081000

Chicago/Turabian StyleSuhner, Jasmine. 2024. "From Shared RE to a Shared Digital RE Strategy: Navigating the Post-Digital Transformation of RE Organizations—Results of a Swiss Participatory Research Project" Religions 15, no. 8: 1000. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15081000

APA StyleSuhner, J. (2024). From Shared RE to a Shared Digital RE Strategy: Navigating the Post-Digital Transformation of RE Organizations—Results of a Swiss Participatory Research Project. Religions, 15(8), 1000. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15081000