Abstract

On the level of fundamental didactic decisions and hermeneutic clarifications, this article examines the possible orientations of Shared Religious Education. The prerequisite for this is the assumption that in such lessons, the opportunity should be used to empower children and young people to become personally and creatively involved in teaching and learning when different denominations, religions, and worldviews come together in education. Against this background, four modes of possible activation are proposed as a structuring aid for didactic decisions: Pupils can (a) plan appropriate forms of encounter themselves and develop ways of dealing with mutually experienced foreignness and with bridges and gaps between traditions; (b) they can be activated to engage in existential discussions about ultimate questions, (c) they can carry out small-scale “research” projects into each other’s religious practices and concepts; and (d) they can get involved in joint (ethical, ecological, neighbourly) projects that have an impact on the region around the school that may also have global applications. The model of these four modes can be represented graphically and this helps to analyse and locate existing concepts and approaches to RE. The article concludes with a closer look at the underlying concept of religion and current research.

1. Introduction

In “Shared RE”, groups of pupils from different religious and ideological backgrounds come together in order to work on joint projects identifying commonalities on the one hand and, on the other, considering differences. Variations in the experiences can be found in Northern Ireland, Germany, South Africa, and many other places around the world and are described in many different ways in this special issue.

Regardless of the respective contexts, there are opportunities for encounters in such religious education for pupils not only to see and recognise each other, but to interact and work together on common and divisive topics, either on an extended or confined scale. Beyond individual format issues, which can differ significantly from country to country (see the descriptions in this volume), self-organised cooperation can become the basis and foundation of teaching. In order to make didactically reflective decisions and to support appropriate teaching and learning processes, it is advisable to differentiate the modes on which this can and should be done and learnt. Four such basic modes are presented in this article, which are briefly mentioned here in advance. Their differentiation can serve as a tool for a didactic clarification process, both as an instrument for planning and as a heuristic tool to assess historical as well as present-day debates in RE. The use of the modes does not anticipate any results but categorises different possible approaches and emphases. These are (1) pupils as sensitive “Bridge and Rift Managers” in religious encounters, (2) pupils as “Researchers in Religious Studies”, (3) pupils as communicative “Existential Thinkers”, and (4) pupils as “Glocal Actors” in the neighbourhood and beyond. The wording emphasises the creative potential of pupils and the centrality of their contribution to the learning process. The primary aim of all four modes is therefore to ensure that the pupils will not adopt a passive–receptive attitude to Shared RE but will adopt an active attitude to working on religious themes and developing constructive relations between adherents of the different traditions.

This is consistent with the findings of cognitive psychology, as the experience of both working independently and as a member of a group leads to increased motivation and confidence (cf. Deci and Ryan 2000). The acquisition of background information and specialised knowledge thus takes place in the course of self-determined learning and joint activities, in which knowledge is achieved in the process of working and seeking to complete educational tasks. This approach also supports conceptual developments and ideas being remembered and internalised more successfully. This pedagogical principle of self-determined learning in a social environment and related methods is not new. Corresponding approaches were developed in the reforming pedagogical literature of the late 19th and early 20th century in various European countries and can be found in the works of John Dewey (1916, pp. 179–92), Maria Montessori ([1950] 1993, pp. 132, 135, etc.) and Célestin Freinet [1949] 1993). Precursors include Pestalozzi (with the ultimate goal of independence “Freiheit und Selbständigkeit in der Darstellung … [der] Fertigkeiten”—PSW 28, p. 73), Fröbel (1863, developing his concept of kindergarten alongside free activities “freithätigen Beschäftigungen” p. 275), and many others.

This article will now explore the different ways it is possible and beneficial through the four modes to encourage pupils to interact independently in Shared RE. In terms of religious education, I draw on British and German literature as helpful background material and give particular attention to both the “Gift to a Child” approach and the “ethnographic approach”.

Firstly, I present the didactic model and explain the modes in detail. This is linked to individual examples for illustrative purposes (Section 2). The model is localised with regard to the research literature of recent decades (Section 3) and graphically illus-trated in Section 4. This is followed by a brief look at the understanding of religion that is presupposed (Section 5), concluding with a specific example of classroom applica-tion (Section 6) and with current research projects and the limitations of the model (Section 7).

3. Points of Reference in the Literature on Religious Education

As already explained in the Introduction, the general educational literature on activity-centred learning extends far back into the 19th century and will not be presented further here. Instead, we will focus on the specific literature on religious education of the last few decades.

For historical reasons, we will start with the third mode, existential thinking and discussions. In the 1960s, Harold Loukes developed a model for religious education in the UK, which while still Christian at the time, also provided for independent work on existential topics (Loukes 1961, 1965). This orientation was not abandoned even when multifaith models were introduced but was generally integrated into them so that a dual orientation emerged in many frameworks and guidelines: an orientation towards religious phenomena and an orientation towards existential questions (City of Birmingham 1975). In connection with this, Michael Grimmitt at Westhill College in Birmingham developed the distinction between “learning about” and “learning from” religion (first in Grimmitt 1977, p. 7f, cf. later Grimmitt 1981, p. 47). The third mode of the Existential Thinker picks up on this and aims to learn from the impulses of others for one’s own worldview and for the clarification of ultimate questions. In Germany and Austria, the hermeneutic approach and the discussion of existential questions also date back to the 1960s, although it was not until the end of the 1960s that it was broadened to incorporate a problem-solving orientation. As a next step, lines of development of the second mode (the Researcher) can also be identified historically. The phenomenological approach in England stands out, although it did not provide a theoretical basis for pupils’ own active research. In the 1970s, there was much talk in England of bracketing out one’s own prejudices when looking at “foreign phenomena” (following Edmund Husserl), but there was hardly any talk of how to activate discussions on one’s own prejudices among the pupils (see Barnes 2014, pp. 94–125). A wider approach that incorporated both theoretical and practical material was first developed by Robert Jackson in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Referring back to the ethnographer Clifford Geertz, he suggested that pupils should develop linguistic bridges to the concepts of other religions and thus to proceed in an interpretive-researching manner. This resulted in a series of book projects. In Germany and Austria, this approach had limited influence (cf. Bauer 1996). Individual projects have only recently been pursued in Germany (adopting a “religious studies” approach: Koch et al. 2013, e.g., pp. 172–81; Frank 2016) and Switzerland (Helbling et al. 2021).

Variations of the first mode of the Bridge and Rift Manager have so far remained much more limited. Different directions can be identified, all capable of being developed. One proposal is for intercultural learning and encounters to take a close look at so-called “critical incidents”, i.e., situations of intercultural misunderstanding (cf. Brislin 1986; and in particular Willems 2011a, 2011b). Another is to find the right balance between closeness and distance to religious objects, both for oneself or for others, for example, dealing with an object that is sacred to others. To what extent is it acceptable to touch it? Can you put on a religious garment, for example, or is that going too far? To what extent can you get involved without offending others? Where are your own boundaries when you “use” another person’s sacred object? In order to clarify this, distance and closeness must be discussed with believers and non-believers and negotiated in the group. In their “A Gift to the Child” approach, John Hull, Michael Grimmit, Julie Grove, and Louise Spencer proposed approaching spiritually charged objects of different religions with particular caution due to their religious and transcendental content and connotations (Grimmitt et al. 1991). They differentiated between sensitive “entering devices” and deliberately staged “distancing devices” (ibid., pp. 9–11) in order to also make clear to younger pupils that both bridges to an encounter with an object as well as continuing distance exist (cf. Meyer 2012, pp. 220–44). Older pupils can discuss together how objects of different religions are dealt with in Shared RE in such a way that their special dignity and sacredness, with their associated lasting strangeness for others, become clear.

The fourth point of the glocal effectiveness is emphasised in particular in the local agreed syllabuses of various English local authorities and in national educational guidelines. For example, the UK Department for Children, Schools and Family (DCSF) states: “The global community—RE involves the study of matters of global significance recognising the diversity of religion and belief and its impact on world issues. … [RE] prompts pupils to consider their responsibilities to themselves and to others, and to explore how they might contribute to their communities and to wider society.” (DCSF 2010, p. 8) “[A]s citizens, … taking appropriate action, putting principles into action” (DCSF 2010, p. 33). These formulations have often been included in many English syllabuses. In Germany and Austria, the so-called ESD projects (Education for sustainable development, e.g., Gärtner 2020) could be utilised here. In-depth theoretical pedagogical analyses that also explore the possibilities of Shared RE would be welcome in the future.

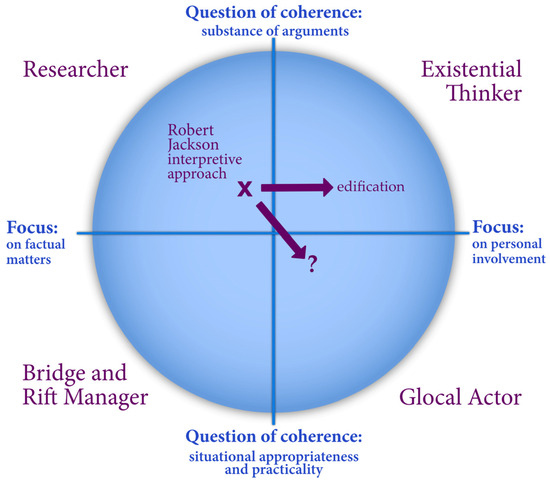

4. A Scheme and Overlaps between the Modes

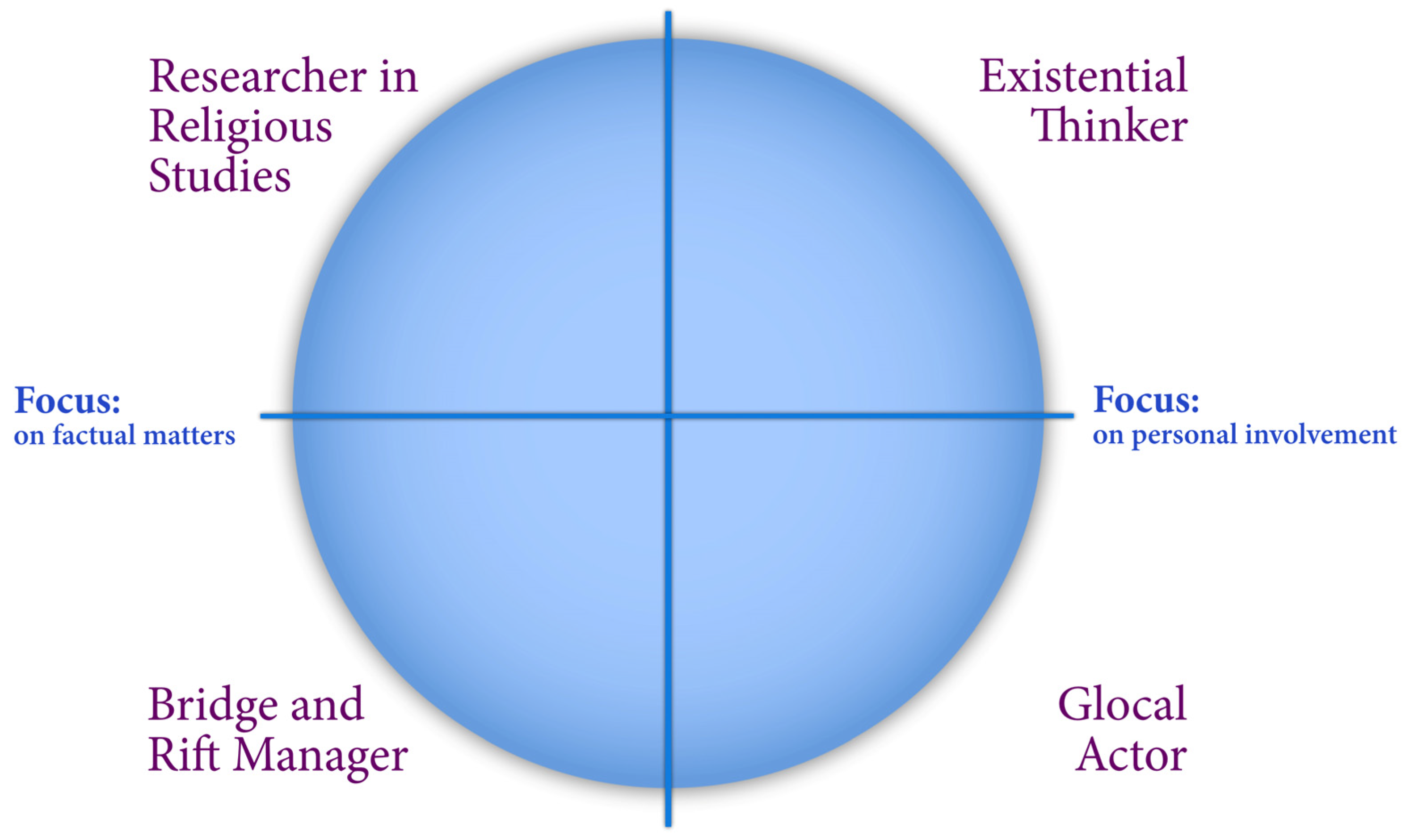

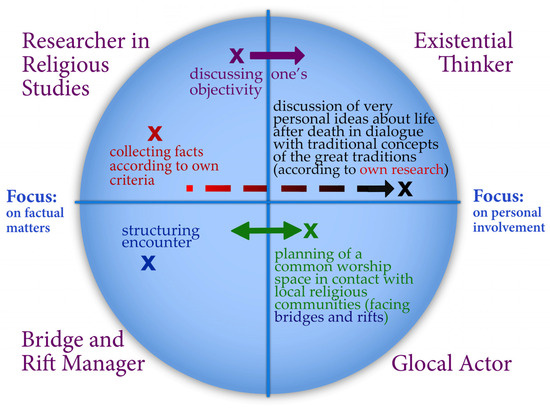

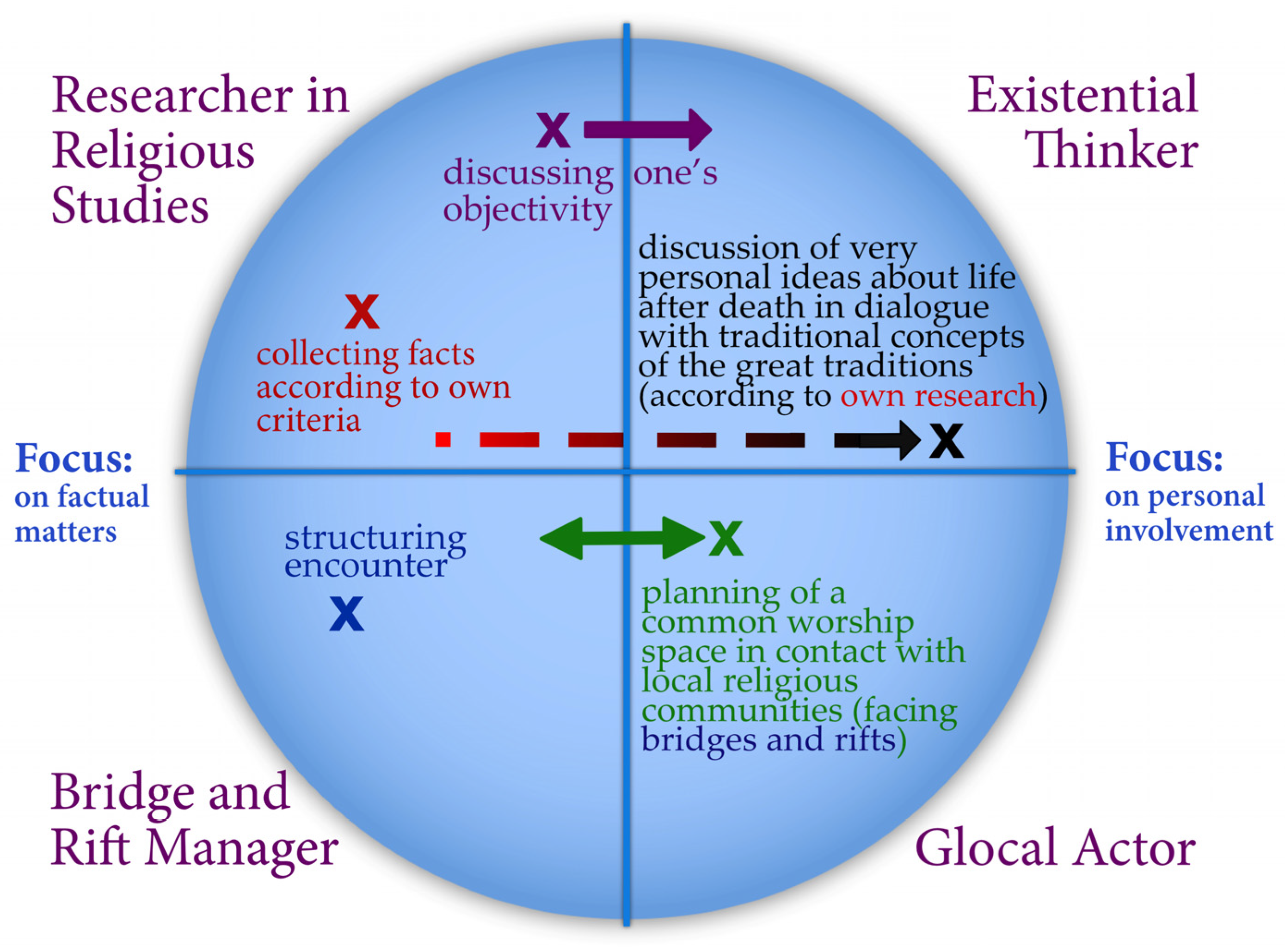

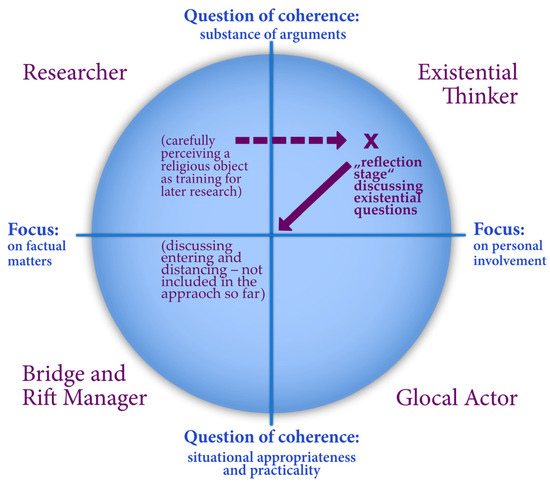

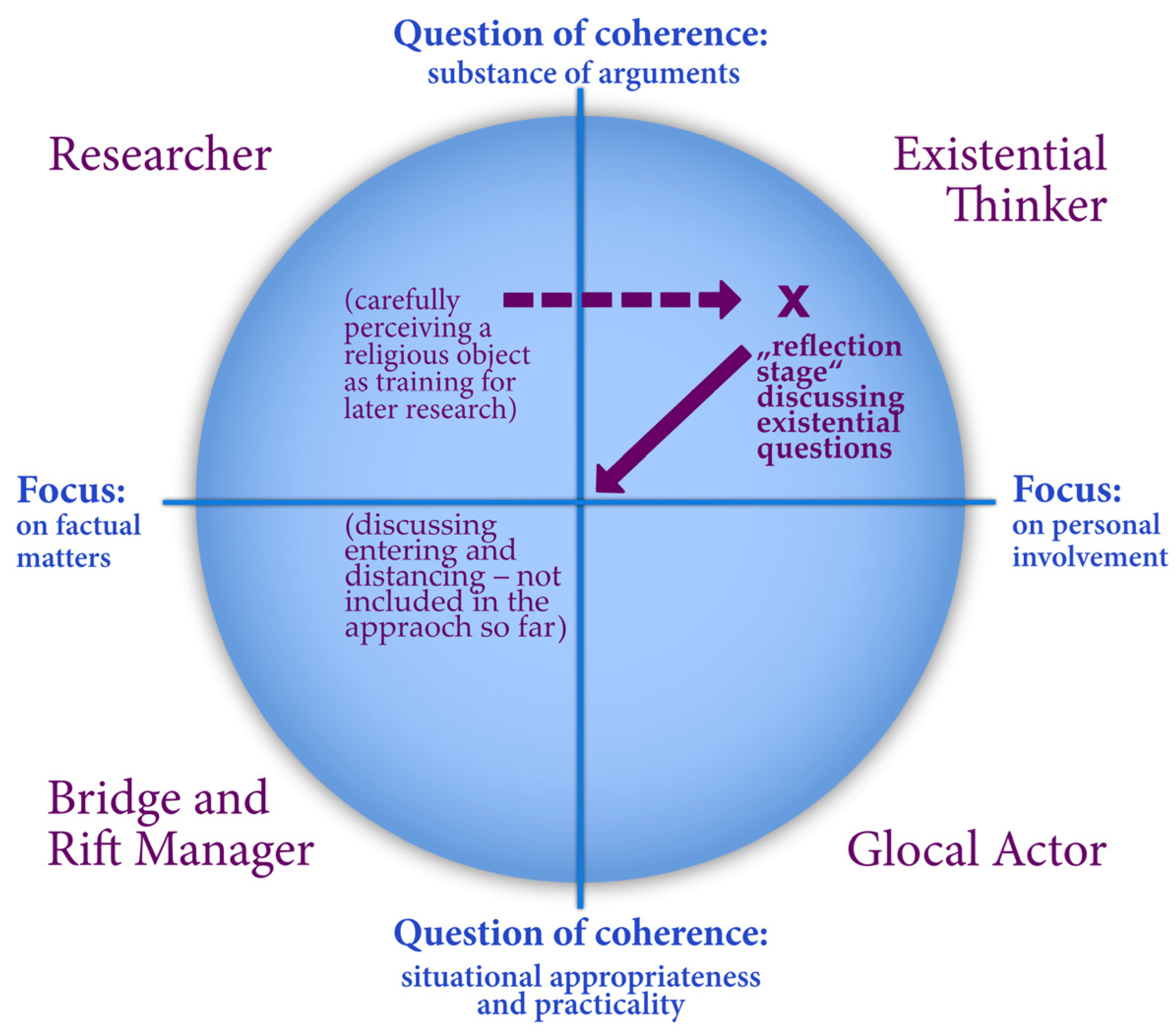

The graphic with four quadrants presented in Figure 1 can better illustrate that different modes overlap in the reality of teaching than the distinction between four isolated modes. Religious education practitioners and theorists can locate themselves in the diagram and, if necessary, visualise further references using connecting lines. This can be illustrated by the following examples (Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4).

Figure 1.

Four modes of discovering and comprehending religious traditions.

First, a few words about the graphic and its arrangement: The second mode (Researcher in Religious Studies), but also the first mode (Bridge and Rift Manager) can be considered in such a way that personal views and positions play no particular role in interpreting (mode 2) or arranging an encounter (mode 1). Therefore, the left side of the graphic model has a focus on factual matters. In contrast, the focus on the right hand involves personal interpretation and involvement. This side includes how the individual feels about an issue and identifies with it. Ideally, this is part of existential discussions (mode 3: Existential Thinker) as well as neighbourhood initiatives (mode 4: Glocal Actor).

We begin with some thematic and then consider conceptual examples: With regard to the pupils’ own small-scale research (mode of “Researcher”), the type of clarification (how to proceed together in collecting facts) is located at the top left (red note of Figure 2). At higher levels of schooling, the question of one’s own objectivity can also be discussed. In this case, it is then about one’s own involvement; accordingly, the positioning of this discussion can be further to the right and, depending on the intensity, can extend into the area of the Existential Thinker (see the violet arrow at the top centre of Figure 2). Furthermore, existential questions (top right) can also be discussed in dialogue with traditional concepts from the religious communities that were identified in the pupils’ research (top left, see black arrow from left to right). With regard to the lower quadrants, the pupils can become personally involved in the planning of a common worship space in consultation with local religious communities (bottom right). Nevertheless, fundamental questions about the encounter need to be clarified in the mode of the Bridge and Rift Manager (bottom left to the right; green note in Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Four modes—horizontal transitions.

Figure 2.

Four modes—horizontal transitions.

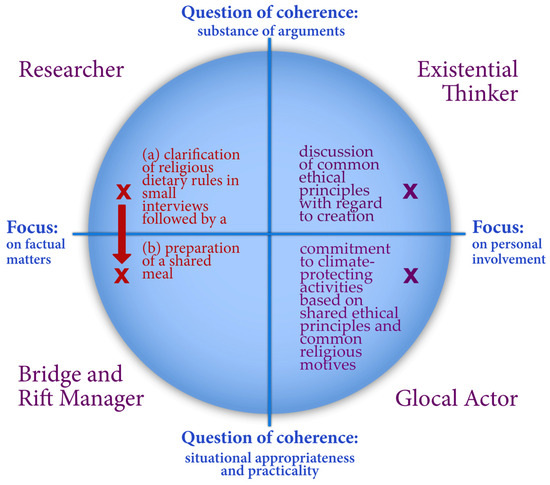

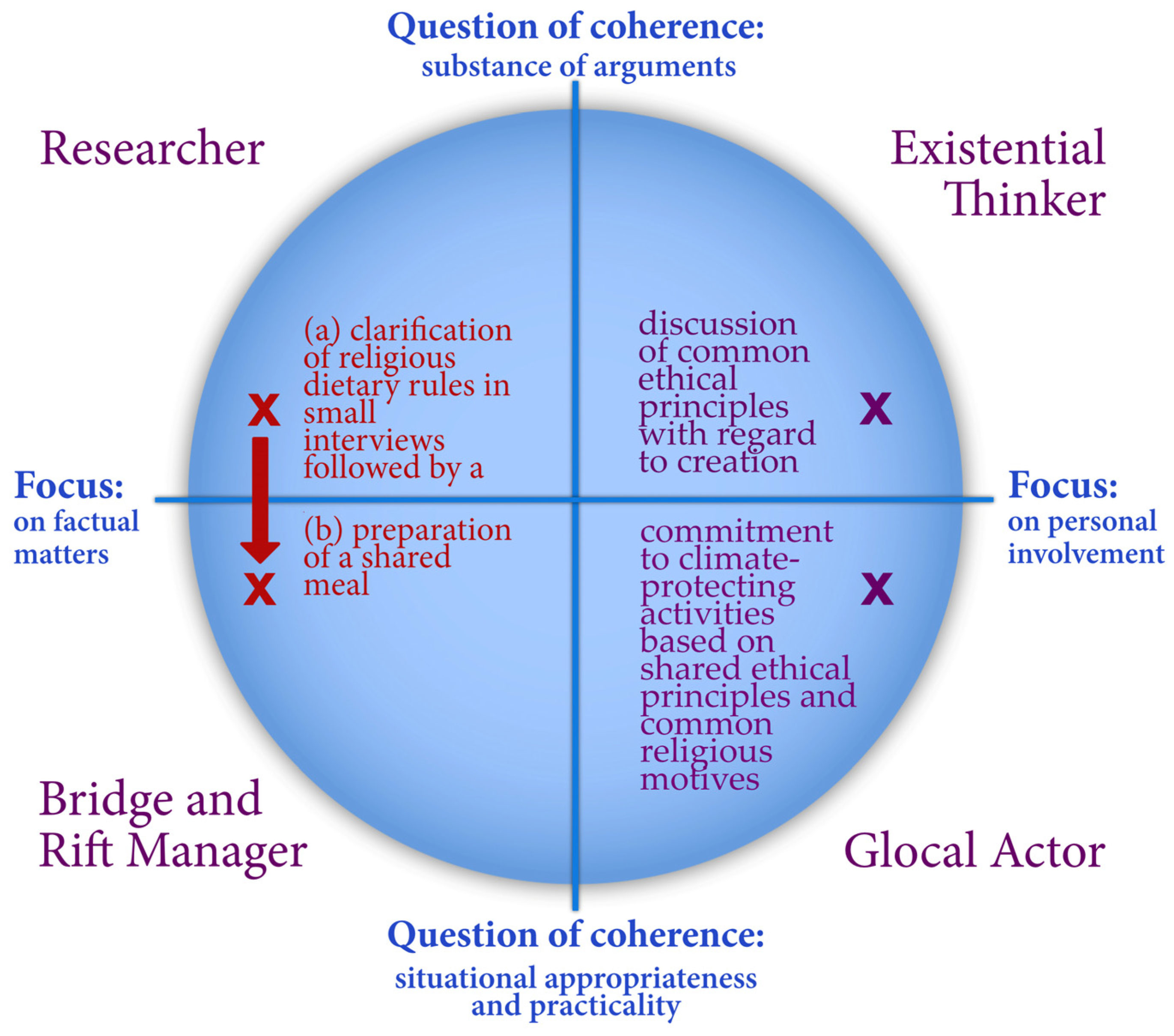

While the previous examples are related to the left and right sides, overlaps can also be found between the upper and lower quadrants (Figure 3 below). In the two upper modes, communicative attention is paid to internal coherence and argumentative conclusiveness (see below “coherence of method and substance of arguments”).

In contrast, the two lower modes tend to emphasise questions of concrete (sensitive) action and thus “external coherence”, situational appropriateness, and orientation towards practical implementation options (see below “question of coherence: situational appropriateness and appropriateness of action”).

Overlaps between the upper and lower modes can become apparent when planning a joint celebration: In self-developed interviews, community members can be asked about dietary rules, and the results can be methodically recorded (top left). For the celebration itself, it is also important to organise the meeting appropriately with regard to bridges and rifts (red note in the transition between the upper and lower areas in Figure 3). With regard to regional commitment to environmental protection (in the Glocal Actor mode), fundamental ethical questions should first be discussed (in the Existential Thinker mode) in order to (then) plan local activities (top and bottom right violet note).

Figure 3.

Four modes—vertical transitions.

Figure 3.

Four modes—vertical transitions.

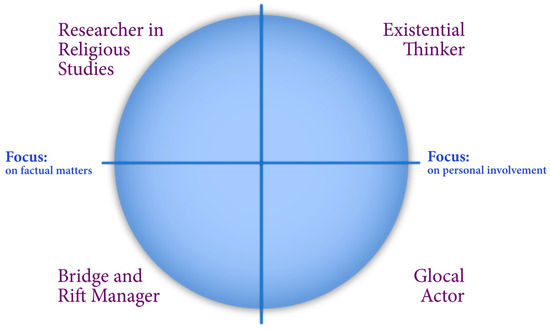

In addition to these more thematic and methodological examples, the model also makes it possible to locate further, conceptually grounded approaches in the literature. This can be briefly explained using the example of the Birmingham “A Gift to the Child” approach mentioned above (Grimmitt et al. 1991). The authors suggest a distinction between phases of engagement, exploration, contextualisation, and reflection. The approach concludes with a reflection phase, in which discussions about existential questions are initiated towards the end of the unit. With regard to the latter, one can speak of an emphasis on the mode of the Existential Thinker. The other three modes of activation remain limited in this teaching potential.

In the first step of the “Gift” approach, e.g., introducing a religious artefact, the perception of the “foreign object” plays a role. Precise and exact perception can be understood as an early phase that prepares for later activities in the mode of the Researcher. This can be visualised below with a connection to the Researcher’s quadrant (broken yellow arrow), the results of which then lead to existential discussions. However, it should be noted that the pupils (due to their age) may not develop their own independent ways of understanding religion.

Considering the Bridge and Rift Manager, questions of distance, gaps, and bridges may be raised in the textbook to be considered by the teacher but not to be discussed by the pupils. Nevertheless, the “A Gift to the Child” approach by Grimmitt and Hull could be used to consider how children can develop their own approaches to encounters (unbroken yellow arrow; see Section 3 above). To summarise: In terms of emphasis, the approach is clearly located in the top right quadrant, with opportunities to expand the Bridge and Rift Manager mode, as already explained. This is visualised in Figure 4:

Figure 4.

Four modes locating Grimmitt’s and Hull’s “A Gift” approach.

Figure 4.

Four modes locating Grimmitt’s and Hull’s “A Gift” approach.

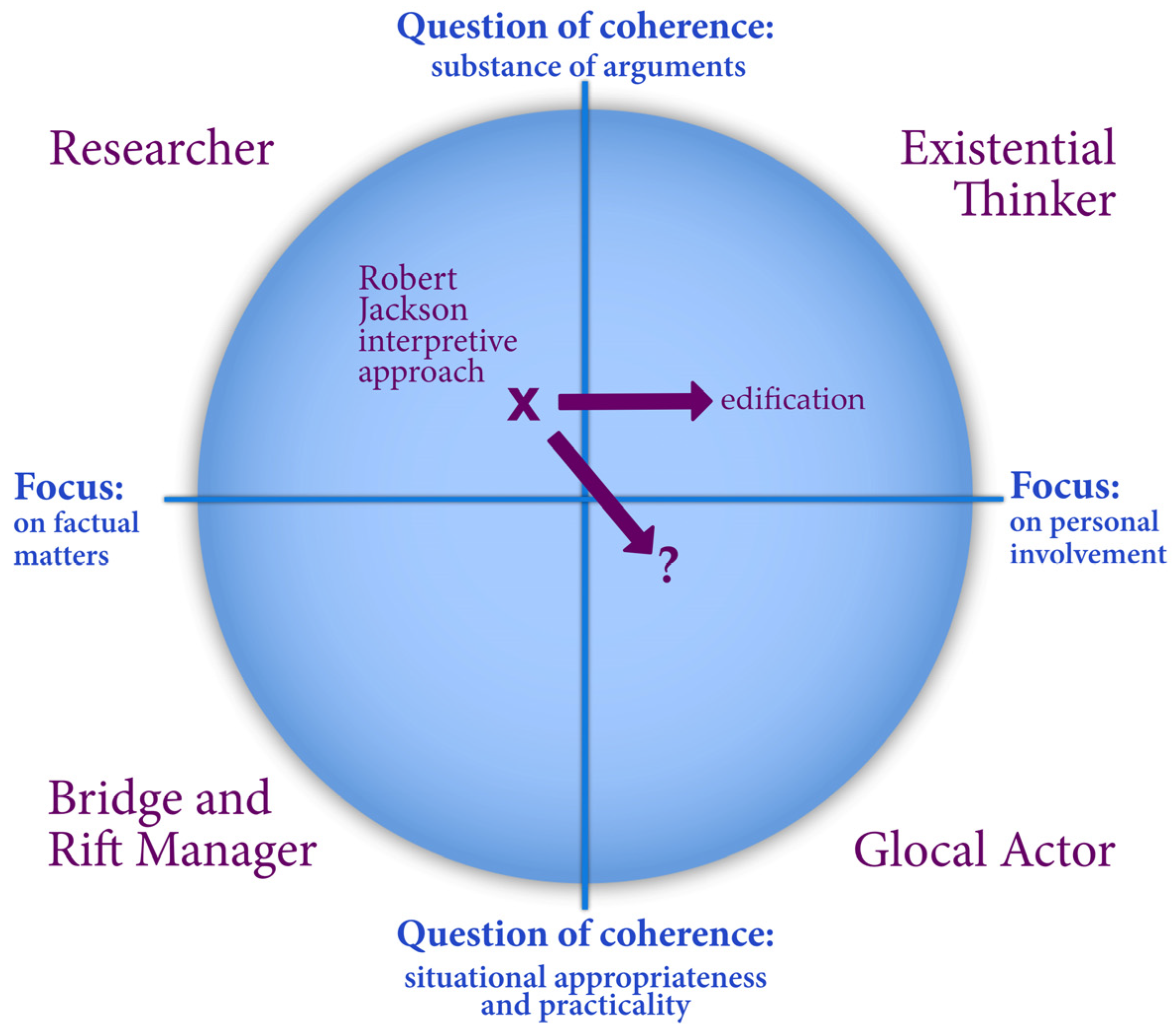

Robert Jackson’s ethnographic approach could be analysed in a similar way as a second example (Figure 5). The mode of the Researcher is immediately apparent here. Jackson has developed his position in line with Clifford Geertz and emphasised the students’ own religious-interpretative abilities. He speaks explicitly of the “interpretive approach” (Jackson 1997). With his later reference to the concept of “edification”; however, he also emphasises questions related to the mode of the Existential Thinker (Jackson 2008, pp. 174–76). This approach can therefore be located more in the two upper modes, with a clear emphasis on the “Researcher”. Jackson’s original local research on Hindu communities in Coventry (Jackson and Nesbitt 1992) could have also included aspects of the local (and global) context.

Figure 5.

Four modes locating Jackson’s interpretative approach.

As the examples show, our four-quadrant model enables an initial categorisation of Grimmitt and Hull’s “A Gift” approach and Jackson’s “interpretive approach”. Moreover, possibilities can be found that are not yet taken into account in the respective approaches but have the potential to be developed.

At this point, a brief comparison should be made with the classic English distinction between “learning from” and “learning about”, which M. Grimmitt developed at Westhill College in Birmingham in the 1970s.

Grimmitt is concerned with going beyond the necessary teaching of facts, e.g., “about” the diversity of religions—he calls this “learning about religion” to also include an interest in pupils being able to learn “from” different religious material for their own spiritual development. He calls this additional aspect “learning from religion” (Grimmitt 1977, p. 7f). At the centre of the debate is the question of whether teaching about religions to which the pupil does not belong can contribute to promoting the pupils’ development. Grimmitt’s distinction lies transverse to the model described here. In all four modes, the acquisition of background knowledge in the sense of “learning about religion” is always part of the process. Facts are necessary for existential discussions, clarification of bridges and rifts, etc. The Researcher mode is undoubtedly the closest to “learning about”, as it involves the collection of religious materials. However, our Researcher mode deliberately emphasises something quite different. It does not simply involve “about” in the sense of the accumulation of knowledge or “fact-gaining” but the “how” of acquiring knowledge: in the Research mode, pupils work out for themselves how to gain and interpret knowledge “about”. However, Grimmitt’s formulation does not consider the role of students’ own research.

In contrast, “learning from religion”, as already indicated above, is often associated with the Existential Thinker mode: Here, students learn in discussions about their own spiritual development. In general, however, the term “learning from” could also be used more broadly, for students can learn “from” encounters about their own social competence and about coping with religious challenges and the experience of foreignness in religious matters. In the mode of the Glocal Actor, they can learn “from” their engagement as citizens with religious (and ethical) issues. The difference between Grimmitt’s terminology and our distinction between modes is that other levels are addressed: While Grimmitt’s distinction with the two prepositions “from” and “about” asks what religious teaching material is for (considering knowledge or spiritual development), the four modes model distinguishes levels concerning the autonomy and dynamism of the pupils.

5. A Dynamic Concept of Religion

The model is based on a dynamic concept of religion. While single religious traditions (such as fundamentalists in Judaism, Protestantism, Catholicism, and Islam) claim that their respective traditions and views have been immovable and unchanging for the most part for centuries, if not millennia, a look at the history of religion makes it impossible to overlook contextual influences and changes throughout. While many textbooks (at least in Germany) tend to fixate on certain beliefs and actions, a look at the reality of life shows how diverse the real life of faith is. Religious traditions are in a constant state of flux, both diachronically and synchronously. The model presented here therefore assumes that in Shared RE, groups and contexts vary again and again and that the participants must each renegotiate what is in the foreground for them. The emphasis on activation makes room for this. In the mode of the Researcher, it is therefore not first and foremost about ready-made knowledge but about being able to collect it (again and again), e.g., in the respective neighbourhoods. In the Existential Thinker mode, it is not a question of a table providing an overview of possible existential approaches to ultimate questions but rather of pupils developing their own questions. Similarly, bridges and rifts must be negotiated anew, etc. All of these clarifications and negotiation processes can refer to the four modes described above and at the same time differ from year to year, depending on the group.

The underlying dynamic concept of religion is based on theoretical considerations such as those formulated by Wilfred Cantwell Smith in the 1960s. He coined the term “cumulative traditions” in a slightly different context (W.C. Smith 1962, p. 154ff). Similarly to our case, he drew attention to the fact that religion is not something static but is linked to change, transformation, and “continuing development” (W.C. Smith 1962, p. 199). The concept of religion should subsequently be understood in this fluid sense. Shared RE therefore requires not only fixed worksheets and book pages for clarification but above all dynamic approaches that can be developed to take account of changing religious and educational contexts.

6. Methodological Experience and Specific Feature: Belief of Pupils through Individuals Presented in the Teaching Media

In line with an understanding of a fluid concept of religion, a methodological proposal can be added, even though it does not necessarily emerge from the model but can nevertheless be linked to it.

In both the English and German contexts, the presentation of individuals in school materials can relieve the burden on pupils, as they themselves do not initially have to be the centre of attention within their respective traditions. Experience has shown that, depending on their class composition, most pupils are not immediately able to provide information on issues relating to their own tradition. Even for those who do have background knowledge, it can be stressful to have to answer questions or explain things about a specific matter. A pedagogical “game about the gang” is helpful here. By using media and materials to introduce other children and young people of relevant religions, the pupils of these religions can relate to them in class, agree with them, or distance themselves from them. The initial emphasis of the presentation is therefore on the media representatives rather than the children in the room. A series of media images of children were included in the Birmingham “Gift” approach of the early 1990s, described above, and in the materials of the Warwick Project, produced under the direction of Robert Jackson (cf. the series “Bridges to Religions”, Jackson et al. 1994; cf. Jackson 1989a, 1989b). The “A Gift to the Child” (Grimmitt et al. 1991), following the presentation of a selected element of religion, a sequence of photographs is presented in which this element is put into use by children in the Birmingham area. Pupils from the classroom who belong to that religion can relate to it. A discussion around existential questions, in the Existential Thinker mode described above, can also arise from this.

The team at Warwick University, led by Robert Jackson, takes a slightly different approach to the media presentation of religious children in the Coventry area. However, as described, the mode of the Researcher takes centre stage. Using accompanying texts, the pupils in the classroom can interpret the material themselves. The children in the classroom are therefore not the object of research themselves but initially the material about other children. In Germany, I have included this use of visual material with children and young people in various publications (Meyer 2006a, 2006b, 2008, 2015). As with the two English originals, I have focused on German contexts that are familiar to the pupils (e.g., a cemetery in northern Germany and not somewhere in the Middle East for the topic of “burials”; see Meyer 2015).

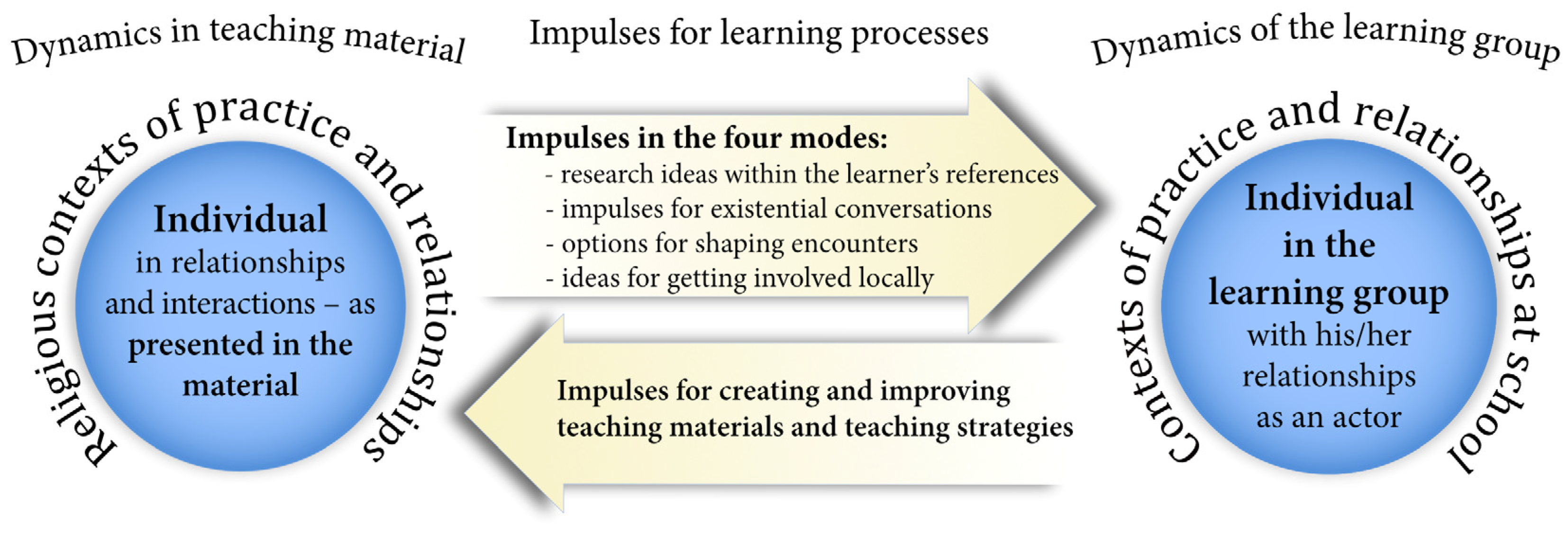

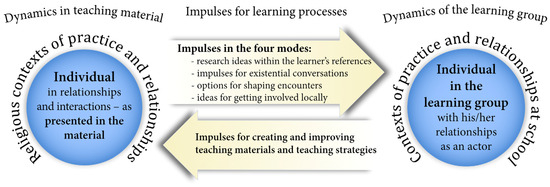

Considering the effects of this methodological approach, I have introduced the concept of “double individual referentiality” (Meyer 2021, pp. 241–62). On the one hand, I associate this with the fact that media-staged individuals are particularly suitable for giving pupils material for discussions or research (similar to the English models). On the other hand, I also suggest that students can be encouraged by the material to create their own lesson templates or picture series. In this way, they can help to provide locally relevant material for future groups, which can of course be varied, anonymised, and expanded later by the teacher. Pupils can also contribute individual ideas for questions and discussions that can be taken up by the next generation of pupils. In this way, a double movement is created from an individually focused picture series to the pupils’ personal views and lifeworld to new material for future pupils (see Figure 6). The term double individual referentiality expresses this reciprocal process.

Figure 6.

Dynamics of double individual referentiality (Meyer 2021, p. 273).

7. Current Research Projects, Opportunities, Limitations, and Conclusions

The model of the four modes is currently being adopted in different contexts and used for scientific analyses. Stefanie Lorenzen (Bamberg University) uses the scheme to differentiate possible competences in religious education in view of the ambiguity of many religious phenomena. The ambiguity of religious phenomena should not be dissolved into unambiguity in the classroom either but should be left for pupils to consider. She illustrates this with the four modes:

The phenomenon of ambiguity can be treated very differently in lessons. Lorenzen sees an opportunity to structure other fields of religious education with this model.“[The mode of] ‘The researcher’ has the ability to perceive vagueness, incompleteness, etc. of religious phenomena, using scientific (e.g., ethnographic) methods. These methods help to capture these ambiguous phenomena, and to differentiate them, thereby working out their fuzziness. [The mode of] ‘The thinker’ has the competence to use ‘the unfamiliar’ or ‘the other’ as impetus for self-reflection, knowing that there is no clear answer. …[The mode of] ‘The manager’ is able to perceive and accept mental reservation about different, ‘unfamiliar’ behaviour, attitudes, etc., to emphasise other, positive attitudes and emotions and then use them constructively to ‘build bridges’ between conflicting parties. ‘The glocal actor’ has the ability to recognise the over-complexity of glocal phenomena …”.(Lorenzen 2022, p. 41)

Jasmin Suhner (Zurich University) takes up the model in an article in this volume (Suhner, forthcoming). In particular, she sees it as a way of structuring and categorising empirical results. A similar project, albeit in a different field, is being pursued by Johanna Hock at the University of Frankfurt.

The opportunities and limitations of the model should also be addressed in this context: The potential of the model lies in the fact that it is equally suitable for lesson planning, lesson analysis, and empirical research analyses. It does not replace methodological clarifications and does not set learning objectives, but it structures a broader framework in which methods and objectives can be localised and blind spots can be identified. Each mode has its own limitations and thus invites interaction with the others (Meyer 2021, pp. 116–18). In this respect, as mentioned above, it is an auxiliary tool for a didactic clarification process and does not anticipate results. In emphasising the autonomy and creative potential of pupils, this approach makes an indispensable contribution to Shared RE. It therefore takes the negotiation processes between people and the dynamics of religious traditions in different milieus and meeting places seriously. It goes without saying that this is not compatible with an approach that aims to provide a quick overview of the religious background of another group in the shortest possible time. In a Shared Religious Education context, sufficient time must be allowed to give the dynamics and creativity of the pupils their own weight.

Shared Religious Education should emphasise interactions with others and with religious phenomena and provide space for pupils to develop through encounters.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Barnes, L. Philip. 2014. Education, Religion and Diversity: Developing a New Model of Religious Education. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, L. Philip. 2020. Crisis, Controversy and the Future of Religious Education. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, Jochen. 1996. Ethnographie im Religionsunterricht. Ein Interpretativer Ansatz. Feuervogel 1996: 20–23. [Google Scholar]

- Brislin, Richard W. 1986. A culture general assimilator: Preparation for various types of sojourn. International Journal of Intercultural Relations 10: 215–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- City of Birmingham District Council Education Committee. 1975. Agreed Syllabus of Religious Instruction. With Foreword, Introduction, Details of the Conference and Sections from the Education Act. Birmingham: City of Birmingham Education Committee, Birmingham. [Google Scholar]

- Deci, Edward, and Richard M. Ryan. 2000. Self-Determination Theory and the Facilitation of Intrinsic Motivation, Social Development, and Well-Being. American Psychologist 55: 68–78. [Google Scholar]

- Department for Children, Schools and Family (DCSF). 2010. Religious Education in English Schools: Non-Statutory Guidance. Nottingham: DCSF Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Dewey, John. 1916. Education and Democracy. An Introduction to the Philosophy of Education. New York: Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Frank, Katharina. 2016. Skizze eines religionswissenschaftlichen Kompetenzmodells für die Religionskunde. ZFRK/RDSR 2016: 19–33. [Google Scholar]

- Freinet, Célestin. 1993. Education through Work. A Model for Child-Centered Learning. Lewiston: The Edwin Mellen Press. Original title: Célestin Freinet. 1967. L’Education du Travail. Paris: Delachaux et Niestlé. First published 1949. [Google Scholar]

- Fromme-Seifert, Viola M., and Naciye Kamcili-Yildiz. 2022. Betül und Nele erleben eine Beerdigung und fragen nach dem Tod. Kamishibai Bildkartenset. (Entdecken—Erzählen—Begreifen: Interkulturelle Geschichten). München: Don Bosco. [Google Scholar]

- Fröbel, Friedrich. 1863. Gesammelte Schriften 1,2: Die Menschenerziehung und Aufsätze verschiedenen Inhalts. Edited by Wichard Lange. Berlin: Verlag Th. Chr. Fr. Enslin. [Google Scholar]

- Gärtner, Claudia. 2020. Klima, Corona und das Christentum: Religiöse Bildung für nachhaltige Entwicklung in einer verwundeten Welt. Bielefeld: Transcript. [Google Scholar]

- Grimmitt, Michael H. 1977. Teaching Christianity in R.E. A Companion to the Two Photo Packs Christianity Today. Essex: Kevin Mayhew Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Grimmitt, Michael H. 1981. When is ‘Commitment’ a Problem in Religious Education? British Journal of Educational Studies 29: 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimmitt, Michael H., Julie Grove, John Hull, and Louise Spencer. 1991. A Gift to the Child. Religious Education in the Primary School. Teachers’ Source Book. London: Nelson Thornes Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Helbling, Dominik, Petra Bleisch Bouzar, and Urs Schellenberg. 2021. Fachdidaktik, religionswissenschaftlich. WiReLex. Available online: https://doi.org/10.23768/wirelex.Fachdidaktik_religionswissenschaftlich.200872 (accessed on 7 August 2024).

- Husmann, Bärbel. 2016. Ein Raum der Stille für alle? Zur Arbeit mit Texten von Dreizehnjährigen. Loccumer Pelikan 2016: 198–99. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, Robert. 1989a. Hinduism. Religions through Festivals. London: Longman. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, Robert. 1989b. Religious Education: From Ethnographic Research to Curriculum Development. In Humanities in the Primary School (Contemporary Analysis in Education Series 28). Edited by Jim Campbell and Vivienne Little. London: Falmer Press Ltd., pp. 171–91. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, Robert. 1990. Children as ethnographers. In The Junior RE Handbook. Edited by Robert Jackson. Cheltenham: Nelson Thornes Ltd., pp. 200–13. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, Robert. 1997. Religious Education. An Interpretative Approach. London: Hodder and Stoughton. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, Robert. 2008. Teaching about Religions in the Public Sphere: European Policy Initiatives and the Interpretive Approach. Numen 55: 151–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, Robert, and Eleanor Nesbitt. 1992. Hindu Children in Britain. Stoke-on-Trent: Trentham Books. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, Robert, Margaret Barratt, and Judith Everington. 1994. Teacher’s Resource Book. Bridges to Religions (The Warwick RE Project). Oxford: Heinemann. [Google Scholar]

- Koch, Anne, Petra Tillessen, and Katharina Wilkens. 2013. Religionskompetenz. Praxishandbuch im multikulturellen Feld der Gegenwart. Münster: Lit. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzen, Stefanie. 2022. Engaging Ambiguity in Concepts of Religious Education. Socio-Ethical and Aesthetic-Theological Perspectives. Theo-Web. Academic Journal of Religious Education 21: 30–44. [Google Scholar]

- Loukes, Harold. 1961. Teenage Religion. An Enquiry into Attitudes and Possibilities Among British Boys and Girls in Secondary Modern Schools. London: SCM Press. [Google Scholar]

- Loukes, Harold. 1965. New Ground in Christian Education. London: SCM Press. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, Karlo. 2006a. Lea fragt Kazim nach Gott. Christlich-Muslimische Begegnungen in den Klassen 2 bis 6. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, Karlo. 2006b. Menschen, Räume und Rituale in Bildmaterialien zu fremden Religionen. Zur Auswahl von Bildern nicht-christlicher Religionen in Büchern für den Religionsunterricht. Theo-Web. Academic Journal of Religious Education 5: 67–95. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, Karlo. 2008. Fünf Freunde fragen Ben nach Gott. Begegnungen mit jüdischer Religion in den Klassen 5–7. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, Karlo. 2012. Zeugnisse fremder Religionen im Unterricht. “Weltreligionen” im deutschen und englischen Religionsunterricht, 2nd ed. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. First published Neunkirchen: Neukirchener Verlag 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, Karlo. 2015. Glaube, Gott und letztes Geleit. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, Karlo. 2019. Grundlagen interreligiösen Lernens. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, Karlo. 2021. Religion, Interreligious Learning and Education. Oxford: Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Montessori, Maria. 1993. Kinder Sind Anders, 8th ed. München: DTV. Original title: M. Montessori (1950), Il segreto dell’infanzia. Milano: Garzanti. First published 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Pestalozzi, Johann Heinrich. 1927–1996. Sämtliche Werke. Kritische Ausgabe (PSW). Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Wilfred Cantwell. 1962. The Meaning and End of Religion. Foreword by John Hick. Minneapolis: Augsburg Fortress. [Google Scholar]

- Suhner, Jasmine. forthcoming. From shared RE to a shared digital RE strategy: Navigating the post-digital transformation of RE organizations. Results of a Swiss participatory research project. Religions.

- Tautz, Monika. 2017. Kultur der Anerkennung. Katechetische Blätter 142: 172–77. [Google Scholar]

- Willems, Joachim. 2011a. Interreligiöse Kompetenz. Grundlagen—Konzeptualisierungen—Unterrichtsmethoden. Wiesbaden: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Willems, Joachim. 2011b. Überschneidungssituationen—Überlegungen zu Ausgangspunkten einer lebensweltlich orientierten interreligiösen Didaktik. Theo-Web. Academic Journal of Religious Education 10: 180–98. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).