Formation of a Sacred Urban Landscape: Study on the Spatial Distribution of Pagodas in Mrauk-U, Myanmar

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Overview of Study Area

1.3. Literature Review

2. Methodology

2.1. Research Objects

2.2. Theoretical Framework

2.3. Materials and Methods

- (1)

- Kernel Density tool

- (2)

- Buffer tool

- (3)

- Space Syntax

3. Distribution of the Pagodas in the Urban Space

3.1. Relationship between the Pagodas and the Urban Structure

3.2. Relationship between the Pagodas and the Mountains

3.3. Relationship between the Pagodas and the Historical Water Systems

3.4. Relationship between the Pagodas and the Open Space

4. Discussion

4.1. Formation of a Sacred Urban Landscape

4.2. Landscape-Shaping Ideas and Cultural Meaning

4.3. Limitations and Insights for Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Mandala (Sanskrit for ‘sacred circle’) is a Hindu-Buddhist religious diagram, which derives from ancient Indian beliefs in cosmic power entering the figure at the center of a sacred space (Dellios 2003). It also represents a cosmogram that related to cosmic order (Rykwert 1976, p. 173). |

| 2 | A small stone image of a Fat Monk, which can be dated to around the beginning of the Christian era, was found about three miles east of the old Vesali site in 1922 (San Thu Aung 1979, p. 15). |

| 3 | Arakan reached the height of its power in the Bay of Bengal, as the Arakanese fleet conquered Pegu or Hanthawaddy, the royal capital of the Burmese empire under the Toungoo dynasty in the year 1600 (Chan 2012, p. 11). The cultural heritages of the Mon, Thai, and Burmese, including four White Elephants, filtered through into the Arakanese civilization (Collis 1973, p. 185; Okkantha 1990, p. 195; Chan 2012, p. 11). |

| 4 | Due to the continuous interactions between Sri Lanka and Arakan in the 16th and 17th centuries, the performance of religious ceremonies and higher ordinations was preserved abroad, which crucially contributed to the re-establishment and restoration of Theravada Buddhism in Sri Lanka (Raymond 1999, p. 98; Okkantha 1990, p. 197). |

| 5 | Emanuel Forchhammer (1851–1890) was a pioneer in Burmese Archaeology. He was a Swiss Indologist, Pali specialist, orientalist and the first professor of Pali in Rangoon College. In 1882, he became an Archaeological Inspector for British Burma, engaging in excavations and the decipherment of ancient inscriptions in Pali, Mon, and Burmese, particularly in the ancient cities of Arakan and Pagan. |

| 6 | According to Yoshinobu Ashihara’s “Exterior Design in Architecture”, the basic scale of urban exterior space is 20–25 m. Based on this, 48–60 m is a suitable distance to observe architectural details such as facade texture, and the building volume becomes the dominant element in the visual landscape observed from 120 m away (Ashihara 1971). |

| 7 | We believe that the Wheel of the Law likely refers to the dharmachakra, considering the Buddhism cultural identity of Arakan kingdom. The dharmachakra points to the central Indian idea of “Dharma”, which refers to the eternal cosmic law, universal moral order (Issitt and Main 2014, p. 186). The Buddha is said to have set the dharmachakra (wheel of dharma) in motion when he delivered his first sermon (Pal 1986, p. 42). Buddhism adopted the wheel as a symbol from the Indian mythical idea of the ideal king, called a chakravartin (“wheel-turner”, or “universal monarch”) (Beer 2003, p. 14; Pal 1986, p. 42). |

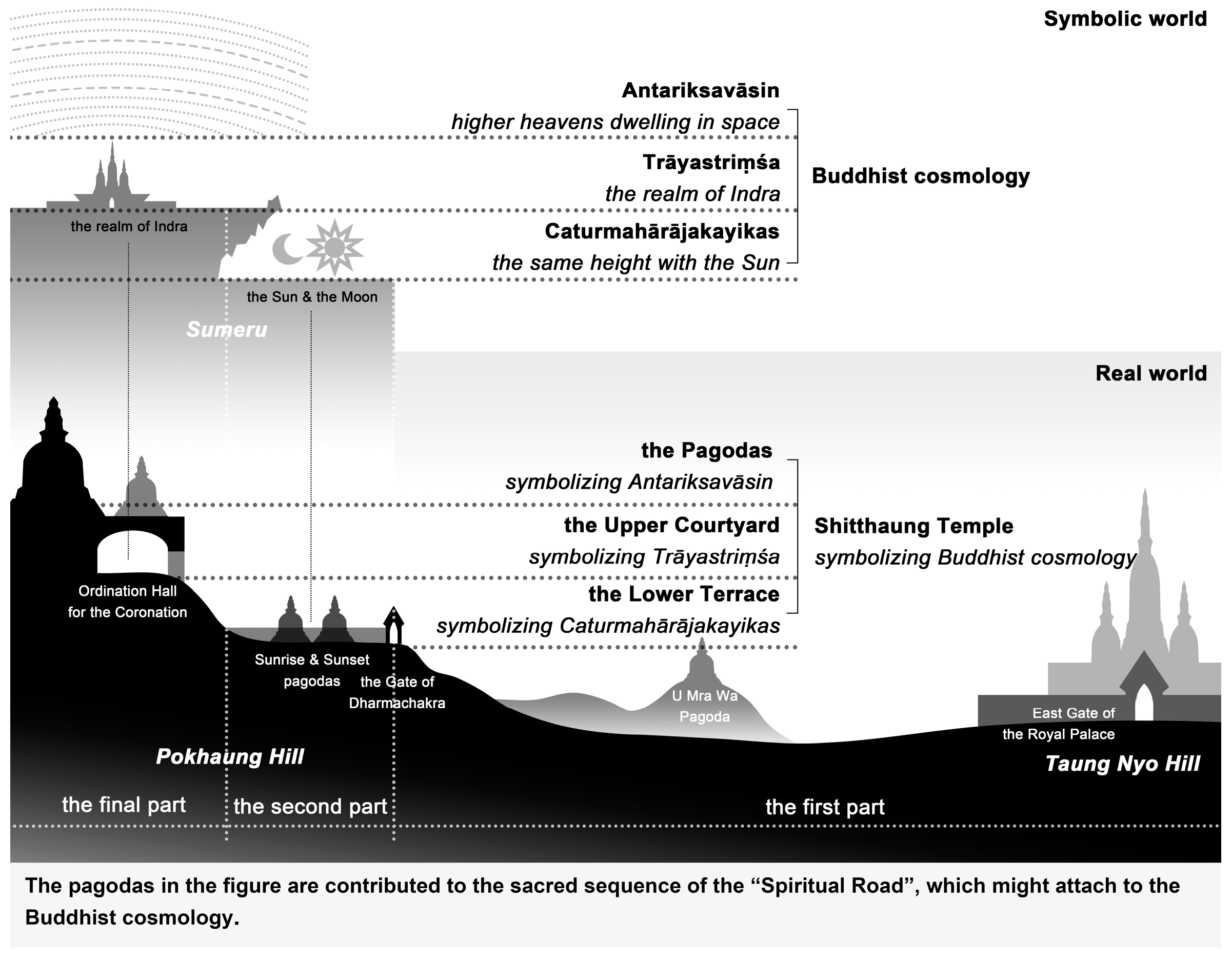

| 8 | The Shitthaung Pagoda includes a lower terrace and an upper courtyard. The lower terrace stands sixteen feet above the level of the road, with the main gate, called the Wheel of the Law. The upper courtyard is thirty feet higher, where the main dome stands (Collis 1973, pp. 269–71). According to Shwe Zan, the Sunrise and Sunset temples are on the lower terrace, indicating that those two small temples are thirty feet lower than the main dome, where the coronation took place (Shwe Zan 1997, p. 35). |

| 9 | This spatial relationship conforms to the spatial imagination that Indra lived on the top of Mount Meru above the sun and the moon in the Buddhist cosmology. |

| 10 | Watching from the ridge between the capital and Bandel, the gilded spires and roofs of the capital were shining in the sunlight, which greatly impressed Schouten and his companions in 1725 (Raymond 2002, pp. 187–88). |

| 11 | As Brigadier General Morrison described in 1825, Mrauk-U’s defenses were carefully designed, including a series of high conical hills, deep intrenchments and a broad river. The high conical hills, surmounted by pagodas, and surrounded by entrenchments, served as numerous citadels. (Wilson 1827, p. 130). |

References

- Ashihara, Yoshinobu. 1971. Exterior Design in Architecture. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold Inc., Translated by Peitong Yin 尹培桐. 1985. As 外部空间设计. Beijing: China Architecture Publishing & Media Co. Ltd., pp. 33–38. [Google Scholar]

- Bafna, Sonit. 2003. Space syntax: A brief introduction to its logic and analytical techniques. Environment and Behavior 35: 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beer, Robert. 2003. The Handbook of Tibetan Buddhist Symbols. Chicago: Serindia Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Bonnier, Anton, Martin Finné, and Erika Weiberg. 2019. Examining Land-Use through GIS-Based Kernel Density Estimation: A Re-Evaluation of Legacy Data from the Berbati-Limnes Survey. Journal of Field Archaeology 44: 70–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, Aye. 2012. The Kingdom of Arakan in the Indian Ocean Commerce (AD 1430–1666). SUVANNABHUMI 4: 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Chaturawong, Chotima, Tawan Weerakoon, and Pongpon Yasi. 2018. Ayutthaya and Burma. NAJUA: Architecture, Design and Built Environment 33: A27–A54. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Xi, and Xuebin Liu. 2021. Quantitative Analysis of Urban Spatial Morphology Based on GIS Regionalization and Spatial Syntax. Journal of the Indian Society of Remote Sensing 51: 1855–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collis, Maurice. 1973. The Land of the Great Image. New York: New Directions Publishing Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe. 2000. European Landscape Convention. CETS No.176. Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publishing Division. [Google Scholar]

- Dellios, Rosita. 2003. Mandala: From Sacred Origins to Sovereign Affairs in Traditional Southeast Asia. Centre for East-West Cultural and Economic Studies No. 10. Gold Coast: Bond University. [Google Scholar]

- ESRI (Environmental Systems Research Institute). 2021. Kernel Density (Spatial Analyst). Available online: https://desktop.arcgis.com/en/arcmap/latest/tools/spatial-analyst-toolbox/kernel-density.htm (accessed on 16 May 2024).

- Forchhammer, Emmanuel. 1891. Arakan I: Mahamuni Pagoda. Yangon: Superintendent Government Printing, pp. 10–11. [Google Scholar]

- Fritz, John. M. 1986. Vijayanagara: Authority and meaning of a South Indian imperial capital. American Anthropologist 88: 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funo, Shuji. 2009. History of Asian City and Architecture. Beijing: China Architecture & Building Press, pp. 192–204. [Google Scholar]

- Gil-Mastalerczyk, Joanna. 2016. The place and role of religious architecture in the formation of urban space. Procedia Engineering 161: 2053–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, Daniel P. S., and Peter van der Veer. 2016. Introduction: The sacred and the urban in Asia. International Sociology 31: 367–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutman, Pamela. 2001. Burma’s Lost Kingdoms: Splendours of Arakan. Bangkok: White Orchid Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gutman, Pamela. 2002. Towards a History of the Architecture of Mrauk U. In The Maritime Frontier of Burma. Edited by Jos Gommans and Jacques Leider. Amsterdam: Koninklijke Nederlandse Akademie van Wetenschappen, Leiden: KITLV Press, pp. 163–76. [Google Scholar]

- He, Shengda. 1991. A Preliminary Study on the Characteristics of Burmese Feudal Society. Social Science in Yunnan 6: 96–103. [Google Scholar]

- Heidegger, Martin. 1971. Building, Dwelling, Thinking. In Poetry, Language, Thought. New York: Harper and Row, p. 149. [Google Scholar]

- Hillier, Bill, and Julienne Hanson. 1984. The Social Logic of Space. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hoskins, William George. 1955. The Making of the English Landscape. London: Hodder & Stoughton, p. 14. [Google Scholar]

- Hudson, Bob. 2005. Ancient Geography and Recent Archaeology: Dhanyawadi, Vesali and Mrauk-u. “The Forgotten Kingdom of Arakan” History Workshop. Bangkok: Chulalongkorn University. [Google Scholar]

- Hudson, Bob. 2020. Using Magic, Religion and Architecture to Ward Off the Enemies of Mrauk-U, Old Arakan, Myanmar. Working Paper. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/344382392_Using_magic_religion_and_architecture_to_ward_off_the_enemies_of_Mrauk-U_old_Arakan_Myanmar_working_draft_may_be_cited_comments_welcome (accessed on 11 November 2023).

- Hudson, Bob. 2023. The Unique “Basket-Buildings” of Mrauk-U. Working Paper. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/341781911_The_unique_basket-buildings_of_Mrauk-U_in_Press_2023 (accessed on 11 November 2023).

- Issitt, Micah, and Carlyn Main. 2014. Hidden Religion: The Greatest Mysteries and Symbols of the World’s Religious Beliefs. New York: ABC-CLIO, p. 186. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Hong, and Yan Zhou. 2023. Evolution of the “Golden Royal City”: Analytical study on urban forms of ancient capital cities in Myanmar. Frontiers of Architectural Research 4: 714–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostof, Spiro. 1992. The City Assembled: The Elements of Urban form through History. London: Thames and Hudson, vol. 2, p. 86. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, Peirce F. 1979. Axioms for reading the landscape. In The Interpretation of Ordinary Landscapes. Edited by Donald W. Meinig. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 11–32. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Jinyi. 2019. The Primary Study on Buddhist Architecture of Mrauk-U, Rakhine, Myanmar. Master’s thesis, Southeast University, Nanjing, China, May 16. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Jeffrey, and Ziling Wan. 2022. The Making of a Sacred Landscape: Visualizing Hangzhou Buddhist Culture via Geoparsing a Local Gazetteer the Xianchun Lin’an Zhi 咸淳臨安志. Religions 13: 711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manrique, Sebastien. 1927. Travels of Fray Sebastien Manripue 1629–1643 (Itinerario De Las Missiones Orientales). Edited and Translated by Lt Col Ekford and Father Hosten. London: Hakluyt Society, pp. 217–18. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, Jeffrey F. 1976. Peking as a Sacred City. Taipei: The Chinese Association for Folklore. [Google Scholar]

- Okkantha, Ashin Siri. 1990. History of Buddhism in Arakan. Ph.D. thesis, University of Calcutta, Calcutta, India. [Google Scholar]

- Pal, Pratapaditya. 1986. Indian Sculpture: Circa 500 B.C.–A.D. 700. Oakland: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Raymond, Catherine. 1999. Religious and Scholarly Exchanges between the Singhalese Sangha and the Arakanese and Burmese Theravadin Communities: Historical Documentation and Physical Evidence. In Commerce and Culture in the Bay of Bengal, 1500–1800. Edited by Om Prakash and Dennis Lombard. New Delhi: Manohar, pp. 87–105. [Google Scholar]

- Raymond, Catherine. 2002. An Arakanese Perspective from the Dutch Sources: Images of the Kingdom of Arakan in the Seventeenth Century. In The Maritime Frontier of Burma. Edited by Jos Gommans and Jacques Leide. Amsterdam: Koninklijke Nederlandse Akademie van Wetenschappen, Leiden: KITLV Press, pp. 177–97. [Google Scholar]

- Rykwert, Joseph. 1976. The Idea of a Town: The Anthropology of Urban form in Rome, Italy and the Ancient World. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- San Thu Aung. 1979. The Buddhist Art of Ancient Arakan; Directed by General Department of Higher Education. Ragoon: Ministry of Education, pp. 14–15.

- Schouten, Wouter. 1676. Oost-Indische Voyagie. Amsterdam: Meurs. [Google Scholar]

- Shrotriya, Alok. 2023. The Indian Stupa and Pagoda of Myanmar. Paper presented at the 2nd International Conference on Kalinga & Southeast Asia: The Civilisational Linkages, Bhubaneswar, Odisha, India, July 27–29. [Google Scholar]

- Shwe Zan. 1997. The Golden Mrauk U _An Ancient Capital of Rakhine. Yangon: Nine Nines Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shwe Zan, San Kyaw Tha, Kyaw La Maung, and Tha San Aung. 1984. Rakhine State Gazetteers, vol. 1. Sittwe: Rakhine State Peoples Council, Translated by Mou Li 李谋. 2007. As 缅甸若开邦发展史. Southeast Asian Study 南洋资料译丛 4: 25–43. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, Ken. 2009. Cultural Landscapes and Asia: Reconciling International and Southeast Asian Regional Values. Landscape Research 34: 7–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tun Shwe Khine (M.A). 1992. A Guide to Mrauk-U: An Ancient City of Rakhien, Myanmar. Yangon: Nine Nines Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Beili. 2019. Study on the Spatial Form and Development of Ancient City of Mrauk-U, Myanmar (1–18 A.D.). Master’s thesis, Southeast University, Nanjing, China. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, Horace Hayman. 1827. Documents Illustrative of the Burmese war: With an Introductory Sketch of the Events of the War and an Appendix. Calcutta: The Government Gazette Press, p. 130. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Changming. 2004. Research on Minority Architectural Cultures in Southeast Asia and Southwest China. Tianjin: Tianjin Universitu Press, p. 154. [Google Scholar]

- Yun, Jiayan, Wenbo Yu, and Hao Wang. 2021. Exploring the Distribution of Gardens in Suzhou City in the Qianlong Period through a Space Syntax Approach. Land 10: 659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Yi, Chaoran Xu, and Tingfeng Liu. 2022. The Connection between Buddhist Temples, the Landscape, and Monarchical Power: A Comparison between Tuoba Hong (471–499) from the Northern Wei Dynasty and Li Shimin (626–649) from the Tang Dynasty. Religions 13: 833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type | Name | Detail | Photo |

|---|---|---|---|

| Individual pagodas | Thin Kyi Taung | Constructed by King Min Saw Mon in 1430 |  |

| Yadanarsan Ye | Constructed by King Narabu in 1446 |  | |

| Ratana Theinkha Shwegu | Constructed by King Min Yan Aung in 1482 |  | |

| Shwe Kyar Thein | Constructed by King Min Phalaung in 1591 |  | |

| Pann Thee Taung Ceti | Constructed by King Sanda Thudhamma Razar in 1658 |  | |

| Pagoda temples | Lemyathna Temple | Constructed by King Min Saw Mon in 1430 |  |

| Anndaw Thein Temple | Constructed by King Min Khaung Razar in 1521 |  | |

| Ratanabon Temple | Constructed by King Min Khamoung in 1612 |  | |

| Htukkant Thein Temple | Constructed by King Min Phalaung in 1571 |  |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhou, Y.; Jiang, H.; Lu, T.; Shen, X. Formation of a Sacred Urban Landscape: Study on the Spatial Distribution of Pagodas in Mrauk-U, Myanmar. Religions 2024, 15, 719. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15060719

Zhou Y, Jiang H, Lu T, Shen X. Formation of a Sacred Urban Landscape: Study on the Spatial Distribution of Pagodas in Mrauk-U, Myanmar. Religions. 2024; 15(6):719. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15060719

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Yan, Hong Jiang, Tianyang Lu, and Xinjie Shen. 2024. "Formation of a Sacred Urban Landscape: Study on the Spatial Distribution of Pagodas in Mrauk-U, Myanmar" Religions 15, no. 6: 719. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15060719

APA StyleZhou, Y., Jiang, H., Lu, T., & Shen, X. (2024). Formation of a Sacred Urban Landscape: Study on the Spatial Distribution of Pagodas in Mrauk-U, Myanmar. Religions, 15(6), 719. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15060719