1. Introduction

Fu Fei 宓妃 (Consort Fu), originally the Goddess of the Kunlun Mountains in ancient Chinese mythology, first appeared in

Li Sao 離騷 by Qu Yuan 屈原 (c.340–278 B.C.) where the following is written: “I command the thunder god Fenglong 豐隆 to ride the colorful clouds, to search for the whereabouts of Consort Fu. 吾令豐隆乘雲兮,求宓妃之所在”. Over time, her image evolved into that of a local water deity governing the Luo River 洛河, a key tributary of the Yellow River in China. During the medieval period, the image of Consort Fu, the Goddess of the Luo River, merged with the historical figure of Zhen Fei 甄妃 (Consort Zhen), the wife of Emperor Wen 文帝 (r.220–226) Cao Pi 曹丕 (187–226), the famous poet Cao Zhi 曹植 (192–232)’s elder brother from the Cao Wei dynasty (220–266). This transformation marked her evolution from a deity governing the Luo River to a beautiful lady yearning for secular love. This significant shift is vividly captured in an ode titled

Luoshen Fu 洛神賦 (

Ode to the Goddess of the Luo River) by Cao Zhi, where her figure is described: “Her body soars lightly like a startled swan; Gracefully, like a dragon in flight. 翩若驚鴻,婉若游龍”. This greatly amplified her fame, inspiring Gu Kaizhi 顧愷之 (348–409) of the Eastern Jin dynasty (317–420) to create a painting bearing the same name (

Figure 1), and it also gave birth to a series of paintings with the theme of the Goddess of the Luo River, including a Qing dynasty (1616–1911) painting, in which Consort Fu is portrayed as a slender, beautiful and dignified figure. Her flowing ribbons highlight her unique temperament, and as she turns her head to look back, her expression is gentle and graceful (

Figure 2). In later periods, this romantic, vivid, passionate and beautiful figure from mythology and the literary arts, who suffered a tragic fate (drowned in the Luo River), was transformed into a deity worshipped by people.

Most existing studies on Consort Fu, the Goddess of the Luo River, focus on the literature. Wu Guanwen discusses the significance of Consort Fu in literary history (

Guanwen Wu 2021, pp. 32–42). Yang Yiting examines the image of Consort Fu during the Sui and Tang dynasties (581–907) based on the myths noted in the annotated

Wen Xuan 文選 (

Selected Works) (

Yang 2008, pp. 8–10). Dai Yan suggests that

Shennü Fu 神女賦 (

Ode to the Goddess) influenced the story structure of the

Luoshen Fu (

Dai 2016, pp. 29–47). Wang Li explores the changes in the image and identity of Consort Fu during the medieval period (

L. Wang 2013, pp. 55–60). Liu Yucan mentions the changes in the image of the Goddess of the Luo River in

Selected Works (

Y. Liu 2016, pp. 30–36). These studies are primarily discussions from the perspective of the creation of the literary work—

Luoshen Fu. There are few discussions from the perspective of belief regarding Consort Fu, the Goddess of the Luo River, with the main work being

Shui Yu Shuishen 水與水神 (

Water and Water Deities) by Wang Xiaolian, which is a compilation of Central Plains water deities from myths and legends, including a brief description of the Goddess of the Luo River (

X. Wang 1996, pp. 52–59).

Zhonguo Minjian Zhushen 中國民間諸神 (

Chinese Folk Gods) compiles fragments of information about various folk deities from classical documentation and literary works but mentions nothing of the Goddess of the Luo River (

Zong and Liu 1987, pp. 223–324). Some scholars have even made bold claims that Consort Fu, the Goddess of the Luo River, was removed from the spiritual realm, as Wang Huaiping holds that the original form of the Goddess of the Luo River, under the concealment of text and image encoding and decoding, was pushed out of the spiritual realm into the cosmos, thereby becoming a distinctive and richly connotative classic image in the world of text and images (

H. Wang 2014, pp. 187–92).

Famous American sinologist N. Harry Rothschild, in his book

Wu Zhao and Her Pantheon of Devis, Divinities, and Dynastic Mothers, mentioned that the mythology of the Luo River and the worship of the Goddess of the Luo River played significant roles in the sanctification of Luoyang as the Divine Capital and in the political ascent of Wu Zhao 武曌, or Empress Wu Zetian (r.690–705). He states, “Deifying the Luo River and worshipping its personification, the Luo River goddess, played important roles both in the sanctification of Luoyang as Divine Capital and the political ascent of Wu Zhao” (

Rothschild 2015, p. 49). Although the article primarily focuses on the era of Empress Wu Zetian, it provides insights into understanding the historical impact of Consort Fu, the Goddess of the Luo River. French poet Yves Bonnefoy believed that “in ancient Chinese mythology, some female characters play a significant role in the belief system, surpassing the expectations of their roles in this patriarchal society” (

Lu et al. 2021, p. 128). These claims can be proven and amplified by the formation and evolution of Consort Fu’s image and the belief in the Goddess of the Luo River. However, no research has focused on the belief in Consort Fu, the Goddess of the Luo River, from the perspective of belief in the deity, discussing the origin and evolution of this belief. This paper examines the evolution of Consort Fu’s image and the development of the Luo River goddess belief by reviewing myths, legends, literary works, epigraphs, ancient national administrative codes and temple materials and by combining oral interviews, field investigations and document verification. It discusses the succession and establishment of the deity of the Luo River, the political significance of the goddess Consort Fu governing the Luo River, how deities from myths and literary works become subjects of folk worship and the spatial distribution and functional shift of Fu Fei Temples 宓妃庙 (Consort Fu Temples, or Temples of the Luo River Goddess), among others, with the aim of promoting in-depth research into the relationship between belief in a deity and state power, as well as public social life.

2. From a Male Deity to a Female One: Succession of the Deity of the Luo River Amidst Changing Times

“The Luo River originates from the Huanju Mountain in Shangluo, Jingzhao”, which, today, is around the eastern Qinling Mountains in Shaanxi Province of China (

D. Li 2021, vol. 15, p. 3). It flows through Yanshi District and Gongyi City in Henan Province before merging into the Yellow River. The Central Plains, where the Luo River is located, was the geographical and political center of ancient China. Belief in the Goddess of the Luo River was prevalent in the birthplace of Chinese civilization—the Central Plains region centered around the Yellow and Luo Rivers. The first dynasty in ancient China, the Xia dynasty (c.2100–c.1600 B.C.), was established here, and it was also the location of the capitals of several subsequent Chinese dynasties.

Rituals to worship the Luo River have been held since antiquity. Historical records mention that the Yellow Emperor 黃帝 once worshipped the Luo River.

Zhushu Jinian 竹書紀年 (

The Bamboo Annals, a history record of the state of Wei during the Warring States Period, also known as

Ji Tomb Annals,

Ji Tomb Classic or

Ji Tomb Book) states, “One day in July, a phoenix arrived, and the Yellow Emperor conducted a sacrifice beside the Luo River. Another day, a dense fog lasted for three days and three nights, darkening the daytime... After the fog dispersed, the Yellow Emperor toured the Luo River, saw a great fish, and then sacrificed five domestic animals, after which a heavy rain fell for seven days and seven nights. The fish swam to the sea, and the Yellow Emperor received the

He Tu 河圖 (River Chart) and

Luo Shu 洛書 (Luo Script). 五十年秋七月庚申,鳳鳥至,帝祭于洛水。庚申,天霧,三日三夜,晝昏……霧既除,游于洛水之上,見大魚,殺五牲以醮之,天乃甚雨,七日七夜,魚流於海,得圖書焉” (

Shen 1522–1566, vol. 1).

Shuijing Zhu 水經注 (

Commentary on the Waterways Classic) cites

Shiji Yinyi史記音義 (

Phonetic Notation and Commentary of The Historical Records), stating, “The Yellow Emperor, during his eastward inspection of the river, passed by the Luo, established a sacrificial altar by the Luo River, sank a jade bi 玉璧 into the Luo River as an offering, received the

He Tu in the Yellow River, and acquired the

Luo Shu in the Luo River. 黃帝東巡河,過洛,修壇沉壁,受《龍圖》於河,《龜書》於洛” (

D. Li 2007, vol. 15, p. 373). The differences in these accounts lie in the sacrificial offerings used when worshipping the Luo River, with one mentioning the sacrifice of five animals (cattle, sheep, pigs, dogs and chickens) and the other mentioning the use of a jade bi.

Emperors Yao 堯, Shun 舜, Shang Tang 商湯 (r.1617–1588 B.C.), Qin Shi Huang 秦始皇 (r.246–210 B.C.) and other emperors in ancient legends personally conducted sacrifices to the Luo River.

Zhushu Jinian records that, in the fifty-third year of Emperor Yao’s reign, he worshipped the Luo River, mentioning, “After the great flood was pacified, Yao abdicated the throne to Shun. Yao bathed and fasted, ordered the construction of sacrificial altars by the Yellow River and Luo River, selected an auspicious day, and led Shun and others to Mount Shou for divine revelations. 洪水既平,歸功於舜,將以天下禪之。乃潔齋修壇場於河洛,擇良日率舜等升首山,遵河渚” (

Shen 1522–1566, vol. 1). The

Shuijing Zhu cites documents in

Diwang Lu 帝王錄 (

Records of Emperors), stating, “Shang Tang set up an altar by the Luo River, following the Emperor Yao’s rituals to repeatedly sink the jade bi into the Luo River for sacrifice. 殷湯東觀于洛,習禮堯壇,降璧三沈” (

D. Li 2007, vol. 15, p. 373).

Emperor Qin Shi Huang also led his ministers to worship the Luo River and the Three Mountains (Penglai, Fangzhang, Yingzhou) and performed music and songs.

Gujin Yuelu 古今樂錄 (

Collection of Past and Present Yuefu Poetry) states, “When Emperor Qin Shi Huang was offering sacrifices to the Luo River, a ‘Black-Headed Lord’ emerged from the river, shouting at Emperor Shi Huang: ‘Come and receive the heavenly treasure.’ Emperor Qin Shi Huang was overjoyed, so he heartily sang, inspired to write

Ci Luoshui Ge 祠洛水歌 (

The Song of Sacrifice to the Luo River), praising the Luo River’s vastness, powerful currents, and surging waves. The sacrificial ceremony by the water, its brilliance connecting with the sun, moon, and stars, symbolized divine protection. 秦始皇祠洛水,有黑頭公從河中出,呼始皇曰:來受天寶。乃與群臣作歌:洛陽之水,其色蒼蒼。祠祭大澤,倏忽南臨。洛濱醊禱,色連三光” (

M. Guo 1998, vol. 83, p. 1173). The “Black-Headed Lord” was probably an avatar of the deity of the Luo River. Ancient emperors leveraged national sacrificial rituals to elevate the status of the deity of the Luo River among the state-recognized pantheon of deities.

According to ancient texts, in the pre-Qin era (before 221 B.C.), the deity of the Luo River, known as Luo Bo 洛伯, like the deity of the Yellow River, He Bo 河伯, was also male. According to

Zhushu Jinian, “The God of the Luo River engaged in warfare with Feng Yi, the God of the Yellow River. 洛伯用與河伯馮夷鬭” (

Shen 1522–1566, vol. 1).

Chuxue Ji 初學記 (

The Primary Anthology) cites

Gui Zang 歸藏,saying, “In the past, the God of the Yellow River, He Bo, prepared to fight with the God of the Luo River, consulting Kun Wu for divination, which concluded, ‘It is not auspicious.’ 昔者河伯筮與洛戰而枚占,昆吾占之,不吉也” (

J. Xu 1883, vol. 20). Both

Zhushu Jinian and

Gui Zang, as pre-Qin documents, record the conflict between Luo Bo and He Bo. In classical Chinese literature, “伯” (Bo) is a term specifically used to denote males. It also has expansive meanings, such as the eldest among brothers, a way of a wife addressing her husband, or a respectful title for an older male. During the spring and autumn period (770–476 B.C.), the leader of a confederation of feudal lords was called “伯”, and it was also a title for officials governing a region. Luo Bo was a male water god who governed the Luo River.

The Yellow River originated from the Bayan Har Mountains (also the Kunlun Mountains in ancient China) in Qinghai Province in Northwest China and was already a major river during the pre-Qin era. The Luo River, a significant tributary of the Yellow River, defied the power of the Yellow River and engaged in entanglements and conflicts with it. During the reign of King Ling of Zhou 周靈王 (r.571–545 B.C.), the Luo River and a tributary on its left, the Gu River 穀水, were involved in such a conflict. From the historical records, it can be felt that the early God of the Luo River was formidable and belligerent. As stated in

Guoyu 國語, “The Gu River fought with the Luo River, causing the flow to surge and demolish the palace of the King of Zhou. 穀、洛鬭,將毀王宮” (

Zuo 2015, p. 67). Descriptions in historical documents give the message that the early deity of the Luo River was powerful, brave and aggressive.

After the Qin dynasty (221–207 B.C.), the deities of the Luo River underwent a change, and the goddess Fu Fei (Consort Fu) replaced the male god Luo Bo. During the Three Kingdoms period (220–280), Cao Zhi states in his

Luoshen Fu, “It was said by the ancients that the deity of this river was named Consort Fu. 古人有言,斯水之神,名曰宓妃” (

Xiao 1986, vol. 19, p. 896). However, the ode does not specify when or why Consort Fu became the deity of the Luo River. Nevertheless, the assertion that Consort Fu was the Goddess of the Luo River was not without foundation and was supported by an array of documentation.

3. From the Kunlun Mountains to the Luo River: Consort Fu in the Interplay between Imperial and Divine Powers

The earliest records of Consort Fu can be found in

Li Sao, where the poet Qu Yuan describes himself as the protagonist on a westward journey in search of Consort Fu by citing myths and legends from ancient classics and ritual texts: “I command the Thunder God Fenglong to ride the colorful clouds, to search for where Consort Fu resides. Unbinding my sash and preparing a letter of proposal, I ask the great minister of Fu Xi 伏羲, Jian Xiu 蹇修, to go and be my matchmaker. The clouds and rainbows gather, parting and merging, soon knowing the matter is perverse and hard to achieve. At night, Consort Fu returns to live at Qiong Shi; by morning, she goes to the banks of the Wei Pan to groom and adorn herself. 吾令豐隆乘雲兮,求宓妃之所在。解佩纕以結言兮,吾令蹇修以爲理。紛總總其離合兮,忽緯繣其難遷。夕歸次於窮石兮,朝濯發乎洧盤” (

Zhu 1979, p. 17).

According to the above-mentioned description, the protagonist in the poem visited the Kunlun Mountains twice to see Consort Fu, whose daily activities took place between “Qiong Shi 窮石” and the “Wei Pan 洧盤” (banks of Wei Pan). “Qiong Shi”, where Consort Fu resided at night, was related to Kunlun. The

Huainanzi 淮南子 states, “The Chishui River originates from the southeastern foot of Kunlun Mountains, flowing southwest into the east of Danze Lake of the South Sea. The Ruoshui River originates from Qiong Shi Mountain. 赤水出其東南陬,西南注南海丹澤之東。赤水之東,弱水出自窮石” (

He 1998, vol. 4, p. 316).

Shanhai Jing 山海經 (

The Classic of Mountains and Seas) states, “On the south side of the Western Sea, beside the flowing sands, behind the Chishui River, and in front of the Heishui River, there is a great mountain named Kunlun. There lives a god with a human face and tiger’s body, covered in white spots and a white tail, residing within Mount Kunlun. At the foot of the mountain, there is a Ruoshui Abyss surrounding it, and beyond the abyss, there is a Flaming Mountain; anything thrown onto this mountain will ignite. There is a person, wearing a headdress, with tiger-like teeth and a leopard-like tail, living in a cave on Kunlun, named Xiwangmu 西王母 (Queen Mother of the West). 西海之南,流沙之濱,赤水之後,黑水之前,有大山,名曰昆侖之丘。有神——人面虎身,有文有尾,皆白——處之。其下有弱水之淵環之,其外有炎火之山,投物輒然。有人,戴勝,虎齒,有豹尾,穴處,名曰西王母” (

Fang 2009, vol. 16, p. 255) (

Figure 3). According to

Shanhai Jing Tuzan 山海經圖贊 (

Illustrated Commentary on the Classic of Mountains and Seas) by Guo Pu 郭璞 (276–324), “Ruoshui River originates from Mount Kunlun, with very low buoyancy, even the feathers of swans will sink in it; to the north, it is obscured by flowing sand, to the south, illuminated by a forest of fire; such mysterious and unfathomable depth of the waters. 弱出昆山,鴻毛是沉;北淪流沙,南映火林;惟水之奇,莫測其深” (

P. Guo 2016, p. 333). The aforesaid documents provide two clues about the relationship between “Qiong Shi” and “Kunlun”. First, Consort Fu resided at night at the origin of Ruoshui River, namely “Qiong Shi”; second, the Ruoshui River originated from the Kunlun Mountains, the dwelling of many deities. Integrating these clues, “Qiong Shi” was part of Mount Kunlun, and Consort Fu’s activities took place in Kunlun.

“Wei Pan” was the river where Consort Fu bathed in the morning.

Yu Dazhuan 禹大傳 states, “The river of the Wei Pan originates from the Yanzi Mountain” (

Y. Qu 1571, vol. 1).

Shanhai Jing 山海經 mentions, “Three hundred and sixty li to the southwest is Mount Yanzi” (

Fang 2009, vol. 2, p. 53). The locations that the protagonist in the poem passed through in his westward search for Consort Fu were also related to Kunlun. Qu Yuan states in

Li Sao, “In the early morning, I will cross the Baishui River and tie my horse upon Langfeng Mountain. Suddenly turning back, my tears flow as I lament that no belle resides on the high mound. I drift to the Spring Palace to break off branches of the jade tree to add to my ornaments. While the blossoms on the jade branches have not yet wilted, I seek the beautiful lady who can accept this gift. 朝吾將濟於白水兮,登閬風而緤馬。忽反顧以流涕兮,哀高丘之無女。溘吾遊此春宮兮,折瓊枝以繼佩。及榮華之未落兮,相下女之可詒”. The Baishui River 白水 was a mythical river originating from Mount Kunlun, known as the “water of immortality”. Wang Niansun 王念孫 (1744–1832) believes the “Baishui River” refers to the “Danshui River” 丹水 mentioned in the

Huainanzi “(

He 1998, vol. 4, p. 325). “Langfeng” was part of Mount Kunlun, as the commentary of Wang Yi 王逸 (89–158) reads, “Langfeng is a mountain on Mount Kunlun” (

Y. Qu 1571, vol. 1).

From myths from remote antiquity and the literary depictions in the

Chu Ci, it is evident that Consort Fu’s residence and activities were in the northwest, around Mount Kunlun. Mount Kunlun, also called Kunlun Xu, Kunlun Hill or Mount Jade, is considered China’s No. 1 sacred mountain and the “ancestor of mountains”. The

Huainanzi states, “Climbing further up from Mount Kunlun, one reaches Langfeng Mountain, where ascending Langfeng Mountain grants immortality; climbing further from Xuanpu, one sees Xuanpu Mountain, where reaching its peak allows one to see deities and control the weather; continuing the climb, one reaches Heaven’s Court, where the God of Heaven resides. 昆侖之丘,或上倍之,是謂涼風之山,登之而不死。或上倍之,是謂懸圃,登之乃靈,能使風雨。或上倍之,乃維上天,登之乃神,是謂太帝之居” (

He 1998, vol. 4, p. 328). It was the dwelling and cultivation place for Chinese ancient deities. Yang Xiong 揚雄 (53–18 B.C.) writes in his

Ganquan Fu 甘泉賦, “Crossing the Ruoshui River as if it were a small creek, walking over Mount Buzhou as though it were but a winding path. He joyfully wishes longevity to the Queen Mother of the West, then avoids the Yu Nü 玉女 (Jade Maiden) and leaves Consort Fu. The Jade Maiden cannot make eyes to the man, and Consort Fu cannot have a smile on her face” (

Z. Zhang 1993, p. 62). Liu An 劉安 (179–122 B.C.), the King of Huainan 淮南王 during the Western Han dynasty (202 B.C.–8 A.D.), lists Consort Fu alongside deities like Leigong 雷公 (Thunder God), Kua Fu 夸父 and Zhi Nü 織女 (Weaver Girl) in the

Huainanzi: “As for the Taoist immortal who drifts in the realm of nothingness, roaming in the formless; riding the mythical beast Feilian 飛廉, accompanied by Dunyu 敦圄 attendants, racing beyond the mundane, leisurely within the cosmos, lighting up with ten suns, commanding wind and rain, making Thunder God a minister, Kua Fu a servant, taking Consort Fu as a concubine, marrying Weaver Girl as a wife. Between heaven and earth, what is there to linger for! 若乎真人則動溶於至虛,而遊於滅亡之野,騎蜚廉而從敦圄,馳於方外,休乎宇內,燭十日而使風雨,臣雷公,役夸父,妾宓妃,妻織女,天地之間,何足以留其志” (

He 1998, vol. 2, pp. 128–29). These records make it clear that Consort Fu, associated with the Queen Mother of the West, Thunder God, Kua Fu and Weaver Girl, was a celestial being and an important mythological figure of ancient times. As Israeli scholar Joseph Mali suggests, recognizing myth for what it is, it is a story that has passed into and become history (

Mali 2003, p. 2). Linking core snippets of information about Consort Fu from pre-Qin documentation, we believe that Consort Fu was akin to the Queen Mother of the West of Mount Kunlun, representing one of the iconic goddesses of Kunlun.

Consort Fu was also identified as the wife of He Bo, as well as the paramour or wife of Hou Yi 后羿. As recorded in

Tian Wen 天問 (

Heavenly Questions of Songs of Chu) by Qu Yuan, Luo Pin 雒嬪 (another name for the Goddess of the Luo River) was originally the wife of He Bo. Hou Yi killed He Bo and seized his wife, Luo Pin. “Emperor Yao sent Hou Yi to eliminate sufferings and appease people, but why Hou Yi shot He Bo with an arrow and seized his wife Luo Pin? 帝降夷羿,革孽夏民。胡射夫河伯,而妻彼雒嬪” (

Y. Qu 1571, vol. 3). Wang Yi, a commentator during the Eastern Han dynasty (25–220), noted, “Luo Pin is a deity of water called Consort Fu” (

Y. Qu 1571, vol. 3). He Bo was the deity of the Yellow River.

Mutianzi Zhuan 穆天子傳 (

The Biography of King Zhou Muwang) states, “The Son of Heaven went on a western expedition to Yangyu Mountain, where He Bo Feng Yi resided. 天子西征。鶩行,至於陽紆之山。河伯無夷之所都居” (

Gao 2019, vol. 1, p. 19). He Bo’s name was Wu Yi 無夷 or Feng Yi 馮夷.

Soushen Ji 搜神記 (

In Search of the Supernatural) records, “A person called Feng Yi lived in Tongxiang Village, Huayin County, Hongnong Prefecture. He drowned while crossing the Yellow River on a day of the energy of metal in the early eighth lunar month. The God of Heaven appointed him as the God of the Yellow River, that is, He Bo. 弘農馮夷,華陰潼鄉堤首人也。以八月上庚日渡河,溺死。天帝署爲河伯” (

Gan 2012, vol. 4, p. 40). As the Luo River was a tributary of the Yellow River, it makes sense in the socio-political and life logic of the time for the Goddess of the Luo River to be He Bo’s wife. The conflict between He Bo and Hou Yi is not unique to China; similar tales exist in Greek mythology, such as the duel between the hero Heracles and a river god (

Schwab 1959, p. 40). Beyond Tian Wen of the

Chu Ci, further evidence of the relationship between Hou Yi and Consort Fu exists. The aforementioned

Li Sao in the

Chu Ci mentions Consort Fu residing at night in the Qiong Shi of Kunlun. “Qiong Shi” was also the dwelling of the monarch of the state of Youqiong 有窮國 during the Xia dynasty, called Hou Yi.

Xiang Gong Sinian in Zuo Zhuan 左傳·襄公四年 (

The Fourth Year of Xianggong in Zuozhuan) cites the words of Wei Jiang 魏絳, recounting that Hou Yi lived in Qiong Shi and seized power from the king of Xia” (

Zuo 1980, vol. 29, p. 1933), indicating that Qiong Shi was a shared residence of Consort Fu and Hou Yi, confirming that the speculation of Consort Fu being Hou Yi’s paramour or wife is not without basis. Some scholars hold that Hou Yi was a demigod hero, as British scholar Andrew Lang states that, in early history, Hou Yi must be a demigod hero celebrated among the people. Marrying Luo Pin must be a love story within the Hou Yi myth, just like that of Heracles (

Mao 1999, p. 104).

Consort Fu was also regarded as either the daughter or the wife of Fu Xi. The view that Consort Fu was Fu Xi’s daughter originated from Ru Chun 如淳, a scholar during the Three Kingdoms period (220–280), who claimed that Consort Fu, Fu Xi’s daughter, unfortunately, drowned in the Luo River, after which the God of Heaven appointed her as the deity governing the Luo River (

Q. Sima 1963, vol. 117, p. 3040). His interpretation had a significant influence, with Tang dynasty historian Sima Zhen 司馬貞 (679–732) referencing Ru Chun in his

Shiji Suoyin 史記索隱 (

Commentary on the Historical Records) and Li Shan 李善 (630–689) citing this in his commentary on

Luoshen Fu at the end of the Tang dynasty. Du Guangting 杜光庭 (850–933) also mentioned in

Yongcheng Jixian Lu 墉城集仙錄 (

Yongcheng Collection of Immortals), “The Luo River’s Consort Fu, the daughter of Fu Xi, became a water immortal” (

Du 1445, vol. 5).

The proposition that Consort Fu was Fu Xi’s wife comes from Wang Yuan 汪瑗 (1522–1566), a scholar during the Ming dynasty (1368–1644), in the

Chu Ci Jijie 楚辭集解 (

Collected Annotations of the Songs of Chu) (

Y. Wang 1615, vol. 2), and this interpretation was adopted by Qu Fu 屈複 (1668–1745) during the Qing dynasty (1644–1912) in the

Chu Ci Xinzhu 楚辭新注 (

New Commentaries on the Songs of Chu) (

F. Qu 1936, vol. 1). You Guo’en 游國恩 (1899–1987) also supports this view in

Lisao Zuanyi 離騷纂義 (

Collected Explanations of Li Sao), arguing that, “since she is called a consort, it definitely signifies a wife or spouse” (

You 1963, p. 304).

Both interpretations have certain textual bases. First, Fu Xi 伏羲is also known as Fu Xi 宓羲, and the first character of Fu Xi 宓羲 and Fu Fei 宓妃 (Consort Fu) is the same in the Chinese language. Second, in

Li Sao of the

Chu Ci, the protagonist requests for Fu Xi’s minister, Jian Xiu, to act as a go-between in his pursuit of Consort Fu (

Y. Qu 1571, vol. 1), and this stands as another piece of evidence linking Consort Fu to Fu Xi. Third, according to records such as

Xi Ci II in I Ching 易經·繫辭下,

Gu Ming in Shang Shu 尚書·顧命 and

Wu Xing Zhi in Han Shu 漢書·五行志, Fu Xi derived the

bagua 八卦 (Eight Trigrams) from the

He Tu and

Luo Shu with the

Luo Shu appearing in the Luo River, showing connections between Fu Xi, Consort Fu and the Luo River. In conclusion, whether Fu Xi’s daughter or wife, both notions highlight the close relationship between Consort Fu and Fu Xi, linking them both to the Luo River.

Analyzing these myths and literary works about Consort Fu, one can sense her mystique. First, Mount Kunlun, a legendary gathering place for ancient immortals, with palaces, Jasper Lake and the Golden City, inhabited by the Queen Mother of the West, who governs life and death among humans, and numerous goddesses. In ancient perceptions, Mount Kunlun was sacred, with inscriptions on ancient bronze objects and oracle bones from the Shang and Zhou dynasties (c.1046–256 B.C.) recording worship of Mount Kunlun. Second, the context of Consort Fu’s story shifts from the heavenly central peak, Mount Kunlun, to the earthly central peak beside the Luo River, Mount Song 嵩山, still enveloped in mystery. The great mountains and rivers that originate here bestow a mystical color to the deities from this place. The Luo River has been regarded as a sacred river with mystical symbolic significance since ancient times, with China’s most famous divine texts, the

He Tu and

Luo Shu, related to the Luo River.

Xi Ci I in I Ching 易經·繫辭上 records that the

He Tu emerged from the Yellow River, and the

Luo Shu emerged from the Luo River (

B. Wang 1980, vol. 7, p. 1980).

Jade Plate in He Tu 河圖·玉版 records a dragon horse carrying the

He Tu emerging from the Yellow River and a divine turtle carrying the

Luo Shu emerging from the Luo River (

D. Li 2007, vol. 15, p. 363). The Luo River flows through the surroundings of Mount Song, with “Song Luo 嵩洛” often referring to Luoyang. Historian Sima Qian 司馬遷 (c.145–c.9 B.C.) during the Western Han dynasty (202 B.C.–8 A.D.) stated that the Xia, Shang and Zhou dynasties were all established in the Central Plains 昔三代之居,皆在河洛之間,故嵩高爲中嶽 where the Yellow River and the Luo River converged, with Mount Song being the earthly central peak corresponding to the heavenly central peak, Mount Kunlun (

Q. Sima 1963, vol. 28, p. 1371).

German philosopher Ernst Cassirer said that myth, on the one hand, shows a conceptual structure, and on the other hand, a sensory structure (

Cassirer 1985, p. 130). Consort Fu’s transition from the source of the Yellow River, Mount Kunlun, to the tributary of the Yellow River, the Luo River, becoming the deity governing the Luo River, was through an imperial appointment by the God of Heaven. The Yellow River, revered as “the No. 1 among all rivers”, is the cradle of Chinese civilization and the origin of the Huaxia people. After the Qin and Han dynasties (221 B.C.–220 A.D.), Mount Kunlun became universally seen as a symbol of imperial power. Fu Xi is regarded as the progenitor of the Chinese people, a distinguished leader of the Huaxia tribes and one of the Three Sage Kings 三皇 of ancient China. He was a historical figure and one of the earliest creator gods recorded in literature. Mythology serves as a reflection of ancient societal life, and Luoyang, being the political center of the medieval dynasties as well as a nexus and radiating center of imperial power and culture, situates the Goddess of the Luo River in a unique position compared to deities like the Deity of the Han River 漢水神 (the goddess of the Han River, a tributary of the Yangtze River in China, first appeared in the

Book of Songs 詩經) or the Deity of the Xiang River 湘水神 (the goddess of the Xiang River, a tributary of the Yangtze River in China, first appeared in Jiu Ge of the

Chu Ci). Endowed and empowered by the forces of heaven, earth and humanity, she not only possessed a noble identity but also carried a mystique and transcendental quality. Her intertwined relationships with He Bo, Fu Xi and Hou Yi blended together, making her an integral component of the Yellow River civilization’s mythological epic.

4. Consort Fu Governing the Luo River: The Political and Cultural Needs to Maintain Regime Stability in the Eastern Han Dynasty

Chronologically, Consort Fu’s residence shift to the vicinity of the Luo River began during the Western Han dynasty.

Min Ming in Jiu Tan九歎·湣命 by Liu Xiang 劉向 (77 B.C.–6 A.D.) records, “Usher Consort Fu from the Luo River into the palace, expelling sycophants and treacherous villains from the court, promoting Lu Shang and Guan Zhong from the remote countryside and wilderness. 迎宓妃于伊雒,刜讒賊於中廇兮,選呂管于榛薄” (

Y. Qu 1571, vol. 1). Yang Xiong’s

Yulie Fu 羽獵賦 states, “Illuminate the luster of the night pearl, open the clamshell resembling a bright moon, whip Consort Fu of the Luo River, compensate Qu Yuan and Peng Xian, Wu Zixu. 方椎夜光之流離,剖明月之珠胎,鞭洛水之宓妃,餉屈原與彭胥” (

Xiao 1986, vol. 8, p. 397). Eastern Han documents follow the Western Han’s portrayal of Consort Fu as a woman living by the Luo River, with Eastern Han official Zhang Heng 張衡 (78–139) describing in

Si Xian Fu思玄賦 how the Queen Mother of the West invited the Jade Maidens of Taihua and Consort Fu of the Luo River to join in joy (

Xiao 1986, vol. 15, p. 669).

Dongjing Fu 東京賦 describes the geographical location of Eastern Capital Luoyang as “backed by the Yellow River facing the Luo River, with the Yi River on the left and the Chan River on the right 泝洛背河,左伊右瀍” (

Xiao 1986, vol. 3, p. 99), then mentioning that “Consort Fu settles in Luoyang 宓妃攸館,神用挺紀” (

Xiao 1986, vol. 3, p. 100). However, upon close examination of these documents, there is no explicit identification of Consort Fu as the Goddess of the Luo River.

In fact, the fundamental transformation of Consort Fu’s identity began with Eastern Han literary scholar Wang Yi. In his commentary on the

Chu Ci, he frequently mentioned that Consort Fu was the Goddess of the Luo River, interpreting “seeking the place of Consort Fu” in

Li Sao as the goddess residing in Kunlun’s “Qiong Shi” and “Wei Pan” (

Y. Qu 1571, vol. 1). In

Tian Wen, referring the line “why shoot He Bo, seizing his wife Luo Pin”, he interpreted Luo Pin as the water deity Consort Fu, also the deity of the Luo River (

Y. Qu 1571, vol. 3). In explaining a line in

Yuan You 遠遊, “Tell the divine bird Qing Luan to fetch Consort Fu from afar”, he stated that Consort Fu is the Goddess of the Luo River (

Y. Qu 1571, vol. 5). When interpreting the line “bringing Consort Fu from the Luo River into the palace” in

Jiu Tan, he further described the divine woman Consort Fu as the spirit of the Yi and Luo Rivers, the deities of these waters (

Y. Qu 1571, vol. 16). Analyzing Wang Yi’s interpretation of Consort Fu’s identity, it underwent transformations from a goddess in Kunlun to a water deity (Luo Pin), then to a water deity in the Luo River, to the Goddess of the Luo River and, finally, to the spirit of the Yi and Luo Rivers. The Han dynasty’s interpretation of “Consort Fu as the Goddess of the Luo River” has been widely accepted by scholars in subsequent eras. For example, the Three Kingdoms period scholar Ru Chun considered Consort Fu as the deity of the Luo River (

Q. Sima 1963, vol. 117, p. 3040). Despite differences between Wang Yi and Ru Chun regarding the origins of Consort Fu, they completely agreed on the viewpoint that Consort Fu was the Goddess of the Luo River. Subsequently, the Three Kingdoms period poet Cao Zhi composed the famous poem

Ode to the Goddess of the Luo River, which greatly enhanced Consort Fu’s reputation.

Known as the Goddess of the Luo River in terms of identity and image, Consort Fu initially resided in Kunlun Mountains in the northwest, moved to Luoyang in the Eastern Han and merged with the spirit of the Luo River to become the Goddess of the Luo River. That the goddess Consort Fu took the place of the male deity Luo Bo to become the governor of the Luo River was an accidental event of the time and an inevitable result of history. We believe that the change in Consort Fu’s residence and the transformation of her identity were principally due to political and cultural considerations. From the time Emperor Guangwu 光武帝 (r.25–57) of the Eastern Han established the capital in Luoyang, the rivalry between the two capitals, Chang’an and Luoyang, never ceased. In the realm of literary writing, works like

Liangdu Fu 兩都賦 (

Ode to the Two Capitals)

Erjing Fu 二京賦 (

Ode to Dual Capitals) and

Sandu Fu 三都賦 (

Ode to the Three Capitals) detailed the geographical conditions, historical evolution, architecture, people, products, lifestyle and cultural institutions of the eastern and western capitals from various aspects and perspectives, subtly expressing the authors’ ideological inclinations and attitudes toward the rivalry. The discussion of the rivalry between the two capitals through literary writing began with the Eastern Han historian Ban Gu 班固 (32–92), who subtly criticized the extravagance of the western capital, Chang’an, in

Liangdu Fu, while lavishly praising the political education and institutional construction of the eastern capital, emphasizing the “dwelling of numerous immortals in Luoyang 館御列仙” (

Xiao 1986, vol. 1, p. 39) and its exceptional natural and cultural environment of “unity between heaven and man 統和天人” (

Xiao 1986, vol. 1, p. 39) and arguing that establishing the capital in Luoyang created a harmonious society of “amiable interaction between humans and gods, orderly relations between sovereign and subjects 人神融洽,君臣有序” (

Xiao 1986, vol. 1, p. 32).

In his

Erjing Fu, Eastern Han scholar Zhang Heng illustrated the history of the eastern capital’s establishment, described the geographical and architectural features of the city and highlighted ceremonies such as court assemblies, sacrifices and hunting activities to showcase the pragmatic fashion of Luoyang’s rulers who “shifted from extravagance to frugality 改奢即儉” and “valued simplicity 尚素樸” (

Xiao 1986, vol. 3, p. 127), emphasizing “the virtue of the Great Han resides here 大漢之德馨,咸在於此” (

Xiao 1986, vol. 3, p. 134).

Dongjing Fu 東京賦 underscored the relationship between Luoyang and Consort Fu, laying the groundwork for later scholars such as Wang Yi and Ru Chun to propose Consort Fu as the Goddess of the Luo River. Deifying Consort Fu as the deity of the Luo River, drawing from previous literature and reflecting the contemporary ideology and ruling thoughts of the Eastern Han in literary creation aimed to glorify the eastern capital, sanctify Luoyang and maintain the legitimacy and stability of the regime through the “Heaven mandate 天命” and “divine grant 神授”. It emphasized that the Eastern Han capital, Luoyang, was chosen not only for its geographical advantages but also by heavenly decree, continuing the legacy of the Xia and Eastern Zhou (770–256 B.C.) dynasties. The Luo River was divine with the legendary appearance of the

Luo Shu carried by a divine turtle. Consort Fu, combining divinity and secular monarchy—spanning the heavens (as a goddess of Kunlun), the water domain (as the wife of He Bo, the deity of the Yellow River) and the human realm (as the daughter of Fu Xi)—clearly had more qualifications to govern the divine water of the Luo River than Luo Bo, further highlighting the cultural mystique and political cohesion of the Eastern Han capital, Luoyang. This not only matched the orthodox status of the Western Han capital Chang’an but also solidified public sentiment and stabilized the realm.

5. The Development of the “Gan Zhen 感甄” Narrative: Bringing Consort Fu, the Goddess of the Luo River, into Traditional Folk Beliefs

Those literati, including Eastern Han scholar Wang Yi and official Zhang Heng, created the unique identity of Consort Fu, the Luo River Goddess, but did not complete the image shaping. Cao Zhi portrayed the beautiful, gentle and passionate literary and artistic image of Consort Fu with a picturesque pen in his Ode to Goddess of the Luo River, in which Consort Fu gradually lost the Kunlun goddess’s proud temperament with “lofty aspirations” and obvious contempt to others in Qu Yuan’s Li Sao, and she transformed into a gentle and passionate woman. Cao Zhi, in his Luoshen Fu, describes Consort Fu as follows: “Her body soars lightly like a startled swan; Gracefully, like a dragon in flight. 翩若驚鴻,婉若游龍”. Her figure is graceful—”Gaze far off from a distance; She sparkles like the sun rising from morning mists; Approach closer to examine: She flames like the lotus flower topping the green wave. 遠而望之,皎若太陽升朝霞;迫而察之,灼若芙蕖出淥波”. Her character is pure—”In her a balance is struck between plump and frail. A measured accord between diminutive and tall. 穠纖得衷,修短合度”. Her figure is delicate—”With shoulders shaped as if by carving, Waist narrow as though bound with White silk waistband. 肩若削成,腰如約素”. Her appearance is exquisite—”Her rare form wonderfully enchanting, Her manner quiet, her pose demure. 瑰姿豔逸,儀靜體閑”. Her posture is elegant—”Her expensive silk gown, dazzling and gorgeous, Her flowery earrings decorated with precious Jade. 披羅衣之璀粲兮,珥瑤碧之華琚”. Her attire is magnificent—”She treads in figured slippers fashioned for distant wandering, Airy trains of mistlike gauze in tow. 踐遠遊之文履,曳霧綃之輕裾”. These detailed, multi-dimensional descriptions of Consort Fu have become the standard image in literary and visual studies of the deity.

Cao Zhi’s

Ode to the Goddess of the Luo River inherits the depiction of Consort Fu as a faithful and beautiful goddess with virtuous nature from Qu Yuan’s

Li Sao and Wang Yi’s literary interpretation in

Chuci Zhangju 楚辭章句 (

Commentary of Sections and Sentences of the Songs of Chu), which solidified Consort Fu’s identity as the Goddess of the Luo River. Moreover, it portrays Consort Fu using secular aesthetics, transforming the goddess, originally elevated to enhance the politically orthodox status and regional superiority of Eastern Capital Luoyang, into a worldly belle prone to romantic fantasies in the literary imagination. The most significant change is the amalgamation of Consort Fu with the historical figure Zhen Fei 甄妃 (Consort Zhen), the wife of Cao Pi, Emperor Wen of Wei (r.220–226), transforming the Luo River deity into a human beauty, combining both Consort Fu and Consort Zhen. Thus, Consort Fu became an object of affection and fantasy for Cao Zhi and subsequent generations of men, which initiated the “Gan Zhen” 感甄 (Pursuing Zhen) narrative. The story of

Dufu Jin 妒婦津 (

The Ferry of the Jealous Wife), which replicated the narrative of Consort Fu drowning in the Luo River to become the Goddess of the Luo River, is documented in

Youyang Zazu 酉陽雜俎 (

Tang’s Horror Stories) by Duan Chengshi 段成式 (803–863) during the Tang dynasty (

Duan 2017, vol. 14, p. 543). In a Chuanqi novel titled

Xiao Kuang 蕭曠 in

Taiping Guangji 太平廣記 (

Extensive Records of the Taiping Era), the image of the Goddess of the Luo River as the human beauty Consort Zhen is also depicted (

Li et al. 1961, vol. 310, pp. 4259–61). In

Xixi Congyu 西溪叢語 (

Bundle of Anecdotes and Interesting stories Recorded in Xixi) by Yao Kuan 姚寬 (1105–1162) of the Song dynasty,

Luoshen Fu 洛神赋 (

Ode to the Goddess of the Luo River) was directly titled

Gan Zhen Fu 感甄赋 (

Ode to Pursue Consort Zhen) (

Yao 1993, vol. 1, p. 28). The “Gan Zhen” narrative in literature continued into the Qing dynasty, as exemplified in Zhen Hou 甄后 (Empress Zhen) in

Liaozhai Zhiyi 聊齋志異 (

Strange Stories from a Chinese Studio) by Pu Songling 蒲松齡 (1640–1715), which also uses themes around this narrative (

Pu 1995, p. 317). Besides Tang Chuanqi novels, the “Gan Zhen” narrative also appears in poetry, such as

Dai Qujiang Laoren Baiyun 代曲江老人百韻 by Yuan Zhen 元稹 (779–831) of the Tang dynasty, which explicitly identifies

Luoshen Fu as

Gan Zhen Fu (

Yuan 1999, vol. 405, p. 4528). Other related works include

Goddess of the Luo River by Tang Yanqian 唐彥謙 (?–893) (

Tang 1999, vol. 672, p. 7746) and

Privately Presented to the Wei Palace 代魏宮私贈 and

King of Dong’a 东阿王 by Li Shangyin 李商隱 (813–858) (

S. Li 1999, vol. 539 and 540, pp. 6223 and 6235).

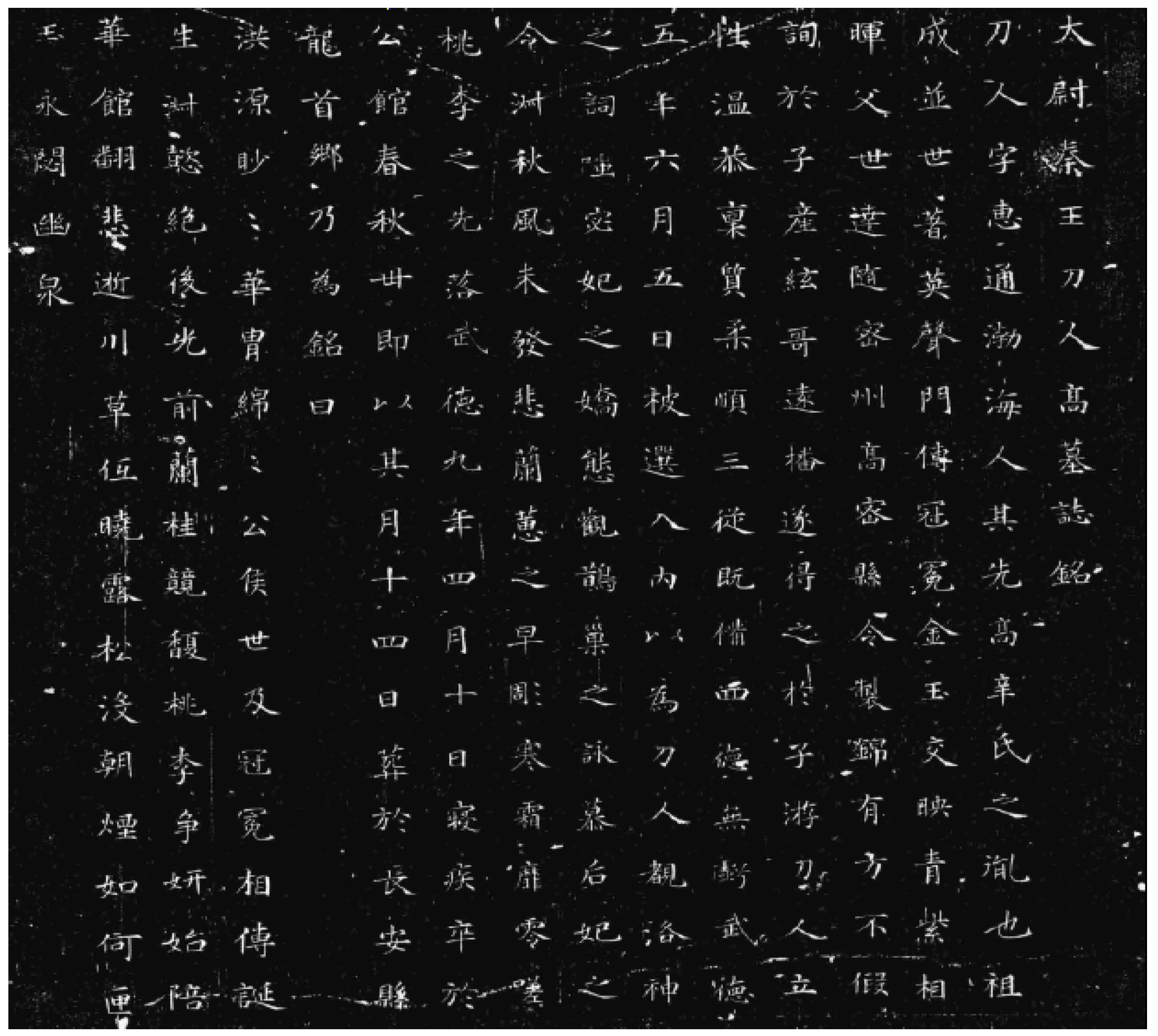

The unique identity of Consort Fu, the Goddess of the Luo River, can also be seen in medieval stele inscriptions. In the

Epitaph of Gao Huitong 高惠通墓志 engraved in the ninth year of the Wude 武德 era (626), it reads, “Viewing the verses of the Ode to the Goddess of the Luo River, sneering at Consort Fu’s charming posture. 覩洛神之詞,嗤宓妃之嬌態” (

Gang Wu 1991, vol. 3, p. 17) (

Figure 4). In the

Epitaph of Niu Xiu 牛秀墓誌銘 engraved in the second year of the Yonghui 永徽 era (651), it states, “The beauty Consort Fu was shot dead by the Luo River, and the assassin Yao Li was drowned in the river. 射宓妃於洛濱,投要離于江上” (

R. Wang 1991, vol. 1, p. 18). In the

Stone Inscriptions of Qinghe Zhanggongzhu 清河長公主碑 in the first year of the Linde 麟德 era (664), it mentions, “Following the imperial daughter by the Xiang River, accompanying Consort Fu by the Luo River. 追帝子於湘川,從密妃於洛浦” (

Zhou 2000, vol. 4 of Part 1, p. 2503) (

Figure 5), where “imperial daughter” refers to Emperor Yao’s daughter E Huang 娥皇, also the Goddess of the Xiang River, and “密妃” refers to Consort Fu, the Goddess of the Luo River. In ancient classics, the Chinese character 宓 (fu) is often miswritten as 密 (mi). Similar records can also be found in the

Epitaph of Peng Jun’s Wife Lady Hou 彭君妻侯氏墓誌 in the fourth year of the Xianheng 咸亨 era (673) (

Zhou 1992, p. 568) and in the

Epitaph of Li Junxian’s Wife Lady Liu 李君羨妻劉氏墓誌in the second year of the Shangyuan 上元 era (675) (

Zhou 1992, p. 609).

Concurrently, place names related to Consort Fu also appear in medieval epigraphs. For example, the

Epitaph of Wang Rong’s Wife Lady Liu 王榮記妻劉氏墓志in the fourth year of the Renshou 仁壽 era of the Sui dynasty (604) records “Luoshen Xian 洛神鄉” (

Wang and Zhou 2007, vol. 3, p. 116). In the twelfth year of the Daye 大業 era (616),

The Epitaph of Song Jun 宋俊墓誌 mentions “Fu Fei Li宓妃里” in Yichuan Xiang, Luoyang County (

Zhao and Zhao 2007, p. 61).

The Epitaph of Sun Jihe 孫繼和墓誌 of the third year of the Kaicheng 開成 era (838) notes, “Mi Fei Li密妃里” in the Sanchuan Township, Luoyang County” (

Zhao and Zhao 2015, p. 1168). The once unreachable ancient goddess “Consort Fu” had by the medieval period transformed into the worldly beauty “Consort Zhen”, and the unique identity information of Consort Fu, the Goddess of the Luo River, also appeared as place names in daily life scenes of the people living along the Luo River. Driven by the widespread writing and development of the “Gan Zhen” narrative, the influence of Consort Fu continued to expand, bringing her identity and image closer to the folk and deepening her presence in the hearts of people. The medieval writing and development of the “Gan Zhen” narrative have continually propelled this divine figure from legends and literary works into the realm of folk beliefs, gradually becoming an object of popular veneration and worship.

6. From National Sacrifice to Folk Worship: The Historical Continuation of the Belief in the Luo River Goddess

Belief in the Luo River Goddess reached its peak during the Tang and Song dynasties, as the government took it very seriously, not only with large sacrificial altars but also with specific hymns and poems for worshipping the Luo River Goddess. In the Tang dynasty, Empress Wu Zetian 武則天 built the Xianshenghou Temple 聖顯侯廟 for the Goddess of the Luo River. The reason was that, in April of the fourth year of the Chuigong 垂拱 era (688), a stone inscribed with “Holy Mother has come in the world, and the empire will flourish forever 聖母臨人,永昌帝業” was fished out from the Luo River. Her nephew, Wu Chengsi 武承嗣 (649–698), claimed it was a divine object bestowed by heaven, also a mandate to the true Son of Heaven on earth, whose reign would surely achieve great accomplishments and bring peace and prosperity to the nation. Wu Zetian was overjoyed, held a grand ceremony by the Luo River, worshipped the Luo River and accepted the sacred diagram. She named this stone Bao Tu 寶圖 (Sacred Diagram), conferred the title Yong Chang 永昌 (Everlasting Prosperity) on the Luo River, conferred the title of Xianshenghou 顯聖侯 (Marquis of Manifestation) upon the deity of the Luo River and established the Xianshenghou Temple (

X. Liu 1975, vol. 24, p. 925).

Zizhi Tongjian 資治通鑒 (

Comprehensive Mirror to Aid in Government) also records that Wu Zetian designated the Luo River as “Everlasting Prosperity Luo River 永昌洛水” (

G. Sima 1956, vol. 204, p. 2449), prohibited fishing and hunting and elevated its worship to the level of national rites, on par with the sacrifices made to the four major rivers and the mountain and sea spirits. Empress Wu composed 14 chapters of

Tang Daxiang Bailuo Yuezhang 唐大饗拜洛樂章 (

The Grand Sacrificial Ode to Luo River Worship) (

M. Guo 1998, vol. 6, p. 87), complete with ceremonial music, marking a period of grandeur.

Unfortunately, the Xianshenghou Temple was demolished in April of the fifth year of the Kaiyuan 開元 era (717). “In the day of Jiawu 甲午, the altar and stele inscription of Wu Zetian’s worship of the Luo River, along with the Xianshenghou Temple, originally built due to the fake auspicious stone inscription by Tang Tongtai 唐同泰, were ordered to be demolished” (

X. Liu 1975, vol. 8, p. 177). However, the worship activities of the Luo River Goddess did not cease following the temple’s demolition. During the Song dynasty,

Shengsong Mingxian Wubaijia Bofang Daquan Wencui 聖宋名賢五百家播芳大全文粹 (

Complete Works of 500-odd Sages of Song Dynasty) included

Luoyangqiaocheng Daoshui Jiluoshen Zhuwen 洛陽橋成導水祭洛神祝文 (

The Prayer Text for the Luo River Goddess upon Water Guiding Ceremony and Completion of Luoyang Bridge) as national prayer and sacrifice texts (

Wei and Ye 1985, vol. 83), indicating that, at least by the Song dynasty, the worship of the Luo River Goddess was still part of the national sacrificial system. Records of state-sponsored worship during the Tang and Song periods (618–1279) all mention the Goddess of the Luo River without mentioning Consort Fu. After the Song dynasty, there are no documentary records of the Goddess of the Luo River’s national worship, which is significantly related to the eastward shift in the political center city after the Tang and Song dynasties. Luoyang completely lost its status as ancient China’s political, economic and cultural center after the Song dynasty. As a result, the Luo River Goddess was removed from the list of deities for state-sponsored worship. Unlike records of state-sponsored worship practices, Consort Fu, the Goddess of the Luo River, is frequently mentioned in literary works. For example, a line from the poem

Mudan 牡丹 (Peony) by Tang dynasty poet Xu Ning 徐凝 (c.792–c.853) reads, “Could it be the Luo River Goddess dancing there, surpassing the splendid morning glow with her charming and varied forms. 疑是洛川神女作,千嬌萬態破朝霞” (

N. Xu 1998, vol. 474, p. 5417). Yuan dynasty poet Ya Hu 雅琥 (1271–1368) writes in the

Luo River Goddess, “Don’t say that Cao Zhi left the jade pillow used by Consort Fu, unable to hear the enchanting music and profound affection. 謾說君王留寶枕,不聞仙子和瓊簫” (

Ya 1709, vol. 49). Similar records can also be found in

Luo Shen Temple (Temple of the Luo River Goddess) by Qing dynasty poet Pan Lei 潘耒 (1646–1708) (

Pan 1710, vol. 14), Qu Fu 屈複 (

F. Qu 1742, vol. 6), etc. Literary works continue the love story between Consort Fu and Cao Zhi.

As the official Goddess of the Luo River moved toward the national altar during the Tang and Song dynasties, the folk belief in the Goddess of Luo River gradually came into being. Records of the Fu Fei Temples 宓妃廟 (Consort Fu Temple) can be found in the local chronicles of the Ming (1368–1644) and Qing (1616–1911) dynasties. For example,

Huanyu Tongzhi 寰宇通志 (

General Chorography of the World) and

Daming Yitong Zhi 大明一統志 (

The National Chorography of the Great Ming Dynasty) record that, during the Ming dynasty in Henan and other places within the jurisdiction of Chengxuan administration commission 承宣佈政使司, the Fu Fei Temples were located “outside the city on the Luo River” (

Chen 2020, vol. 85;

X. Li 1505, vol. 29).

HongzhiYanshi Xianzhi (弘治)偃師縣誌 (

Chorography of Yanshi County in Hongzhi Reign) notes that the Fu Fei Temples were in Shaowei Bao 保 (an administrative unit in ancient China) in the south of Yanshi County (

Wei and Zhang 1962, vol. 1).

Daqing Yitong Zhi 大清一統志 (

The National Chorography of the Great Qing Dynasty) supplements that Luo Shen Temple 洛神廟 (Temple of the Luo River Goddess) was south of the Luo River in Luoyang County (

Mu and Pan 2008, vol. 207).

Jiaqing Henan Tongzhi (嘉靖)河南通志 (

General Chorography of Henan in Jiajing Reign) documents that a Fu Fei Temple was built in the prefectural city during the Yuan dynasty in the sixth year of the Zhizheng 至正 era (1356), and Yanshi and Gong County also had a Fu Fei Temple (

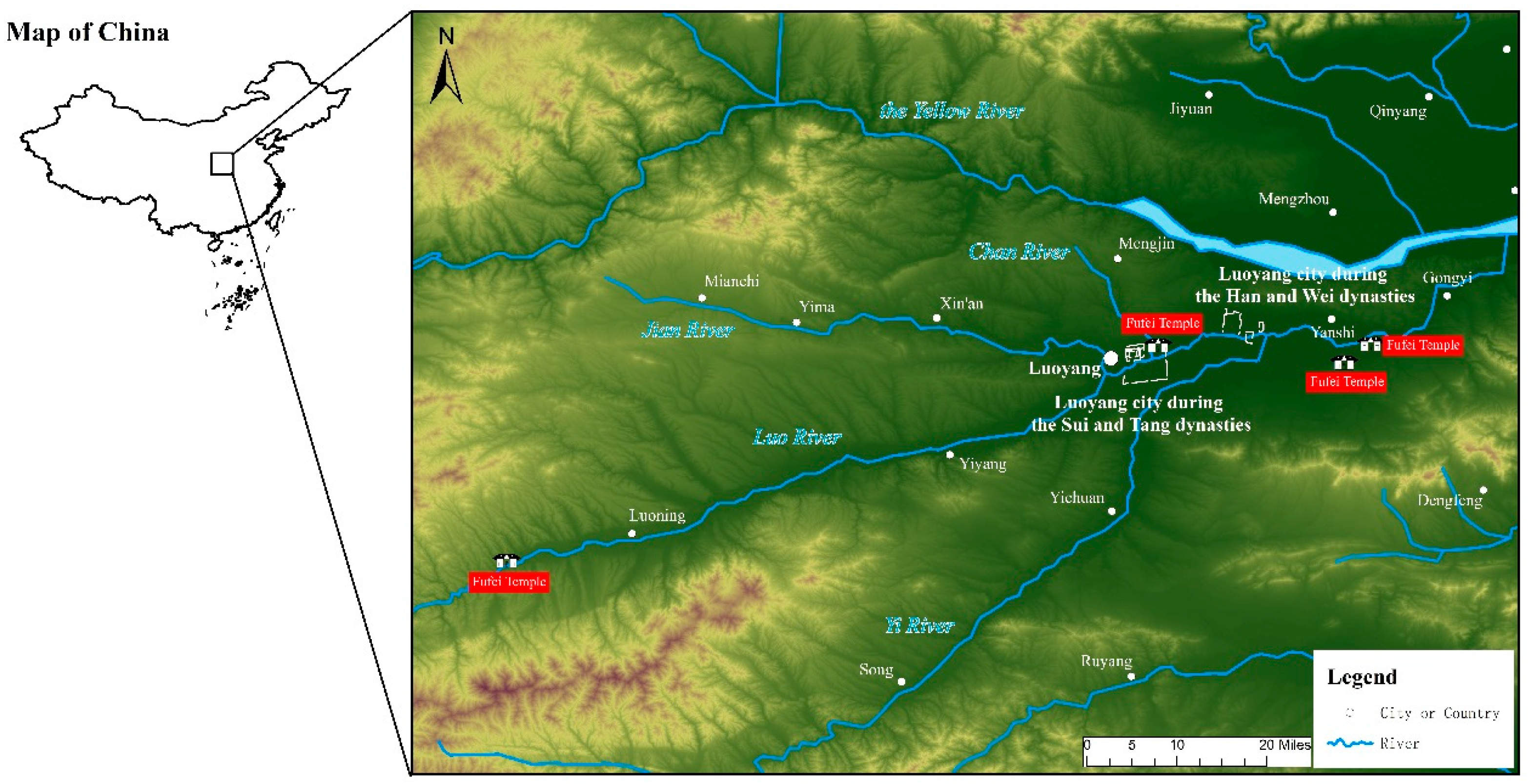

Zou and Li 1555, vol. 18). There are no records regarding who built these temples or their scale. Based on the search for official historical documents and local chorographies, we conducted field investigations and visits to the temples dedicated to Consort Fu, the Goddess of the Luo River, in and around Luoyang, identifying four such temples (

Figure 6) (

Table 1), with the only remaining one being the temple in Changshui Village 長水村, Luoning County (

Figure 7). In front of this temple, there stands a stele that is round at the top and square at the bottom and 2.1 m in height, featuring a pattern on the head that reads, “The Place Where the Luo Shu Emerged 洛出書處”, suggesting that the temple might have been established during the Han or Wei period (

J. Wang 1976, vol. 467).

Belief in the Goddess of the Luo River is prevalent in the Yellow River and Luo River region. In addition to burning incense and worship, the people often hold temple fairs and perform operas to honor the Luo River Goddess.

Luoyang Fengsu Suotanlu 洛陽風俗瑣談錄 (

Records of Luoyang Customs) documents that, during the Republic of China period (1911–1949), the Luo Shen Temple Fair was held in the city of Luoyang: “In at least dozens of temples in the city of Luoyang and its surrounding areas, plays are hosted for three days each in spring and summer. In particular, at the Luo Shen Temple, plays are performed from the second day of the first lunar month to the second day of the second lunar month, lasting an entire month” (

Hu 2008, p. 426). Play performances start from the second day of the first lunar month and continue for a whole month, highlighting the level of attention and affection the folk have for Consort Fu, the Goddess of the Luo River. The temple in Liu Village, Huiguo Town, Gongyi City, Zhengzhou, no longer exists, but the local villagers still hold the Consort Fu Temple Fair annually on the twenty-third day of the sixth lunar month, with major plays performed continuously for three days (

W. Zhang 2018, p. 214). Temple fairs and operas serve as important ways to please the deity and people themselves and offer trade and money-making opportunities. Furthermore, the way the people of Luoyang commemorate their belief in Consort Fu is also reflected in the special couplets written for the worship of the Luo River Goddess. Every Chinese New Year, the villagers in Changshui Village, Luoning County, write couplets such as “The

He Tu’s legacy illuminates, encompassing heaven and earth; The Luo lady’s renown safeguards the people 河圖遺畫明齊日月函乾坤,洛女載籍譽滿神州佑百姓” or “Emperor Fu Xi who governs the world and universe, protect land of China; the Luo River Goddess who moistens mountains and rivers blesses the people of Luoyang 羲皇封九州執掌乾坤,洛神澤山河庇佑平安”. The transition of the belief in the Goddess of the Luo River from official to folk realms, deeply intertwining with people’s lives, is a historical reflection of the eastward shift in the imperial center after the Tang dynasty and the decline of Luoyang’s political status. It also signifies a transformation in the function of the belief in the Luo River Goddess, from a political guardian deity ensuring the nation’s peace and the government’s stability to a protective deity for ordinary people’s family stability and prosperity of descendants. The Luoshen Temple, commonly known as Luochuan Nainai Temple洛川奶奶廟 (Luochuan Nanny Temple) and Luohe Niangniang Temple洛河娘娘廟 in the local area, were mainly for women praying to bear children and for blessings of safety for their kids, rather than male-dominated officials praying for national prosperity and stability. The only existing Luoshen Temple in Changshui Village has even become the most important folk belief site in the local area, providing spiritual support and religious assistance to the daily lives of the local residents, where people of different ages, genders and professions from various parts of Luoyang pray for a happy marriage, prosperous business, smooth academic progress, etc.

7. Conclusions

The mythical origin of Consort Fu, the Goddess of the Luo River, can be traced back to remote antiquity. The earliest document that mentions Consort Fu is Qu Yuan’s collection of Chu Ci poems, Li Sao, written during the Warring States period (476–221 B.C.). There are a variety of versions of stories about the original identity of Consort Fu, such as Fu Xi’s daughter, He Bo’s wife, etc. Consort Fu’s identity continuously evolved with the change in dynasties, bearing varying political and cultural implications and reflecting the expectations and aspirations of different social classes. Through a review of the myths and literary works about Consort Fu, and based on field investigations into the Fu Fei Temples (Temples of Luo River Goddess Consort Fu), we have drawn five conclusions, as follows.

First, rituals to worship the Luo River have been held since antiquity. According to ancient records, legendary emperors including the Yellow Emperor, Yao and Shun, as well as Qin Shihuang and other emperors, personally conducted rituals to worship the Luo River. Ancient emperors leveraged national sacrificial rituals to elevate the status of the Goddess of the Luo River among the state-recognized pantheon of deities. The governor of the Luo River during the pre-Qin period was the male deity Luo Bo, and in the Han dynasty and later, it was the goddess Consort Fu.

Second, as mentioned in ancient literary works such as ci 辭 (song) and fu 賦 (ode), Consort Fu, who resided in the Kunlun Mountains in Northwest China, often interacted with the Queen Mother of the West, Thunder God, Kua Fu, Weaver Girl and other gods. The various intertwined origins of Consort Fu’s identity add to her mystery and sacredness, and they highlight the uniqueness of her identity and status and, in particular, at the political and cultural level, as an amalgamation of imperial power and divine power—a witness to the “divine rights of monarchs 君權神授”.

Third, in the Eastern Han dynasty and onward, Consort Fu’s residence place shifted eastward to the Luo River, and Consort Fu, depicted as the Goddess of Kunlun, took the place of Luo Bo to become the Goddess of the Luo River. The evolution was primarily driven by the political and cultural factors of the Eastern Han dynasty. Consort Fu was depicted as a goddess that came from the Kunlun Mountains, the source of the Yellow River, and took charge of the Luo River per the order of Heaven in order to highlight the cultural mystery and political magnet of Luoyang, the capital of the Eastern Han, as a sign of “divine rights of monarchs”. This was also performed to give Luoyang the same orthodox status as Chang’an, the capital of the Western Han, and to show the legitimacy of the Eastern Han regime for the sake of strong popular support and social stability.

Fourth, the “Gan Zhen” narrative, exemplified by Cao Zhi’s Luoshen Fu, crafted a literary and artistic image of Consort Fu, the Luo River Goddess, as beautiful, gentle and affectionate. This combination of Consort Fu with the human beauty, Consort Zhen, led to a gradual reduction in her divine attributes and an increase in her human qualities. This image has been widely depicted in Tang Chuanqi novels, poetry and epigraphs, continually expanding the social influence of the Goddess of the Luo River. Consequently, she transitioned from mythological and literary art into the secular and folk realm, becoming a folk temple idol like the “Grandma of the Luo River”, protecting all beings and embodying ideals.

Fifth, Wu Zetian once personally held a sacrificial ritual honoring the Luo River, conferring upon the Goddess of the Luo River the title “ Xianshenghou” and building the Xianshenghou Temple. Luoyang completely lost its status as ancient China’s political, economic and cultural center after the Song dynasty. The Goddess of the Luo River was removed from the list of deities for state-sponsored worship, and Consort Fu had since been worshipped as a local folk belief. Thus far, four Luo Shen or Consort Fu temples with clear locations have been identified; among them, only the one in Changshui Village, Luoning County, Luoyang City, still exists today. Today, folk rituals to worship the Goddess of the Luo River primarily include holding Luo River Goddess temple fairs and writing couplets with Consort Fu elements.