A Forgotten Eminent Buddhist Monk and His Social Network for Constructing Buddhist Statues in Qionglai 邛崍: A Study Based on the Statue Construction Account in 798

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. An Overview of the Statue Construction Account in 798

2.1. Research History of the Statue Construction Account

2.2. The Summary of the 798 Account

3. The Initiator Sengcai 僧采

3.1. Who Was Sengcai?

[=隸]此州花置寺). Then, he was summoned into the Zhangjing Temple by Daizong in 769. In 798, Sengcai wished to go back to Qiongzhou and planned to construct the Buddhist niches in person (方欲再踐鄉園, 躬宏制 度). Regretfully, he did not receive Dezong’s approval (大師尋有表辭,/△恩

[=隸]此州花置寺). Then, he was summoned into the Zhangjing Temple by Daizong in 769. In 798, Sengcai wished to go back to Qiongzhou and planned to construct the Buddhist niches in person (方欲再踐鄉園, 躬宏制 度). Regretfully, he did not receive Dezong’s approval (大師尋有表辭,/△恩 [旨]未許).

[旨]未許).3.2. The Background of Zhangjing Temple in 767–805

3.2.1. Important Events at Zhangjing Temple between 768–805

3.2.2. Monks at Zhangjing Temple and Their Activities in 767–805

- Faqin 法钦 (715–793), residence from 768 onward for a period of unknown length;

- Biancai 辯才 (724–778), 768–778 residence;

- Fengguo 奉國 (d.u.), 768–771 residence;

- Huilin 惠林 (d.u.), residence in 771;

- Sengcai 僧采 (d.u.), 769–798 residence;

- Fazhao 法照 (d.u.), residence at the end of the Dali era (766–779);

- Yuanying 元盈 (d.u.), residence in 773;

- Youze 有則 (d.u.), 777–778 residence;

- Xizhao 希照 (d.u.), 778–780 residence;

- Puzhen 普震 (d.u.), 778–781 residence;

- Lingming 令名 (d.u.), residence in 779;

- Daoxiu 道秀 (active in 770s–800s), 777–779 residence;

- Biankong 䛒空 (d.u.), residence in 788;

- Zhitong 智通 (d.u.), residence in 789;

- Wukong 悟空 (731–?), residence in 790;

- Weiya惟雅 (d.u.), residence in 790;

- Daocheng道澄 (?–803), 781–803 residence;

- Jianxu 鑒虛 (?–813), 796–798 residence.

3.3. Sengcai’s Situation at Zhangjing Temple between 769–798

In the fourth year of the Dali 大曆 era (769), Emperor Daizong’s feelings turned profound as time went by (or Emperor Daizong felt endless grief for his deceased mother), [to the point that His Majesty decreed] the construction and renovation of Zhangjing Temple. By virtue of this [background], the emperor Daizong bestowed the great master (i.e., Sengcai) to reside at the temple. Because of [Sengcai’s] virtue, the emperor decreed to appoint him the Administrator (gangwei 綱維) [of the temple]. [Sengcai’s] wisdom exceeded that of his fellow monks [and his] words became the norm of public opinions. 大曆四年, 代宗感深日(=罔?)極, 創修章敬, 籍△勅賜大師. 懿德以故, 主授綱維. 智出緇流, 言成方物.

The person who newly built the stone niches and statues at Huazhi Mountain Temple in Qiongzhou was the imperially appointed shangying 上應 (=shangzuo 上座 [Head-seat]) of Zhangjing Temple in the Upper Capital (i.e., Chang’an). 邛州花置山寺新造石龕像者,△御賜勅授上京章敬寺上應(=座?).

4. Supporters and Sponsors

4.1. Emperor Dezong

4.2. The Commissioner of Merit and Virtue

4.3. Sengcai

4.4. Yuanrong 元戎 and Fangbo 方伯

5. Sengcai and Daoying 道應 as Project Co-Managers

(旨)未許). Here, the character ci 辭 either means leaving or resigning. But, if Sengcai was only away from the capital for a few months for Qiongzhou to manage the statue construction project at Huazhi Temple, he would not have felt the need to officially submit a memorial to request a short-term leave. Before Sengcai presented his memorials, the 798 Account also mentioned that Buddhist believers in Chang’an, out of their admiration for him, were reluctant to let him go and begged him to stay. So, the meaning of the character ci 辭 should be understood as resigning. That is, Sengcai submitted a memorial to Dezong requesting his resignation from his role as the Zhangjing Head-seat and leave for Huazhi temple in Qiongzhou. Same as the characters of yuan qin jiacai, Sengcai’s intension of resignation also indicates his determination at the Huazhi project.

(旨)未許). Here, the character ci 辭 either means leaving or resigning. But, if Sengcai was only away from the capital for a few months for Qiongzhou to manage the statue construction project at Huazhi Temple, he would not have felt the need to officially submit a memorial to request a short-term leave. Before Sengcai presented his memorials, the 798 Account also mentioned that Buddhist believers in Chang’an, out of their admiration for him, were reluctant to let him go and begged him to stay. So, the meaning of the character ci 辭 should be understood as resigning. That is, Sengcai submitted a memorial to Dezong requesting his resignation from his role as the Zhangjing Head-seat and leave for Huazhi temple in Qiongzhou. Same as the characters of yuan qin jiacai, Sengcai’s intension of resignation also indicates his determination at the Huazhi project.6. The Author of the 798 Account

7. Concluding Remarks

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| B | Dazang jing bubian 大藏經補編. See Secondary Sources, Lan (1985) (comp.). |

| T | Taishō shinshū daizōkyō; see Takakusu and Watanabe (1924–1934). |

Appendix A

(=靈), 實亦宏開夫教化.

(=靈), 實亦宏開夫教化. 90(=隸)此州花置寺, 為碩德焉. 而識通化洽, 理造音操. 誠玄境之玉潔貞姿, 得釋家之如來密諦. 三明教內, 引離小/乘;四部衆91中, 常演大法. 故得聲馳92上國, 名重神都. 大曆四年, 代宗感深日(罔?)93極94, 創修章敬, 籍△勅賜大師. 懿德以故, /主授綱維. 智出緇流, 言成方物.

90(=隸)此州花置寺, 為碩德焉. 而識通化洽, 理造音操. 誠玄境之玉潔貞姿, 得釋家之如來密諦. 三明教內, 引離小/乘;四部衆91中, 常演大法. 故得聲馳92上國, 名重神都. 大曆四年, 代宗感深日(罔?)93極94, 創修章敬, 籍△勅賜大師. 懿德以故, /主授綱維. 智出緇流, 言成方物. (=兼)請所舊居蘭若之額, 以“淨法般/若”為名. △上允所祁(=祈?), 廣以“貞元”二字101. 仙毫乍拂, 覩鵉鳳之遺文; 御牓 遙飛, 動江山之喜氣. 乃曰: “詔功德使、開府寶(=竇?)102, /誥103宣揚, 仍將錫助.”大師志存丹懇, 願罄家財. 方欲再踐鄉園, 躬宏制 度, 而都城仰恋(=戀), 法衆104請

(=兼)請所舊居蘭若之額, 以“淨法般/若”為名. △上允所祁(=祈?), 廣以“貞元”二字101. 仙毫乍拂, 覩鵉鳳之遺文; 御牓 遙飛, 動江山之喜氣. 乃曰: “詔功德使、開府寶(=竇?)102, /誥103宣揚, 仍將錫助.”大師志存丹懇, 願罄家財. 方欲再踐鄉園, 躬宏制 度, 而都城仰恋(=戀), 法衆104請 (=留). 大師尋有表辭, /△恩

(=留). 大師尋有表辭, /△恩 (旨)未許. 乃仗本州白鶴寺臨壇大德沙門道應講論、同製規模. 元戎105、方伯等, 各竭真誠, 以資其事.

(旨)未許. 乃仗本州白鶴寺臨壇大德沙門道應講論、同製規模. 元戎105、方伯等, 各竭真誠, 以資其事. (=於)是千億萬佛, 尊容儼/然; 三十二相、毫光普照. 釋侶瞻仰, 州人護持. 天107皷(=鼓)時鳴, 不憚怒雷之震;法雨常潤, 無憂劫火108之焚. 資國祚以延長, /濟羣生而何極? 能事已畢, 寧無記焉!

(=於)是千億萬佛, 尊容儼/然; 三十二相、毫光普照. 釋侶瞻仰, 州人護持. 天107皷(=鼓)時鳴, 不憚怒雷之震;法雨常潤, 無憂劫火108之焚. 資國祚以延長, /濟羣生而何極? 能事已畢, 寧無記焉!| 1 | In this article, Sichuan refers to both Sichuan province and contemporary Chongqing municipality. |

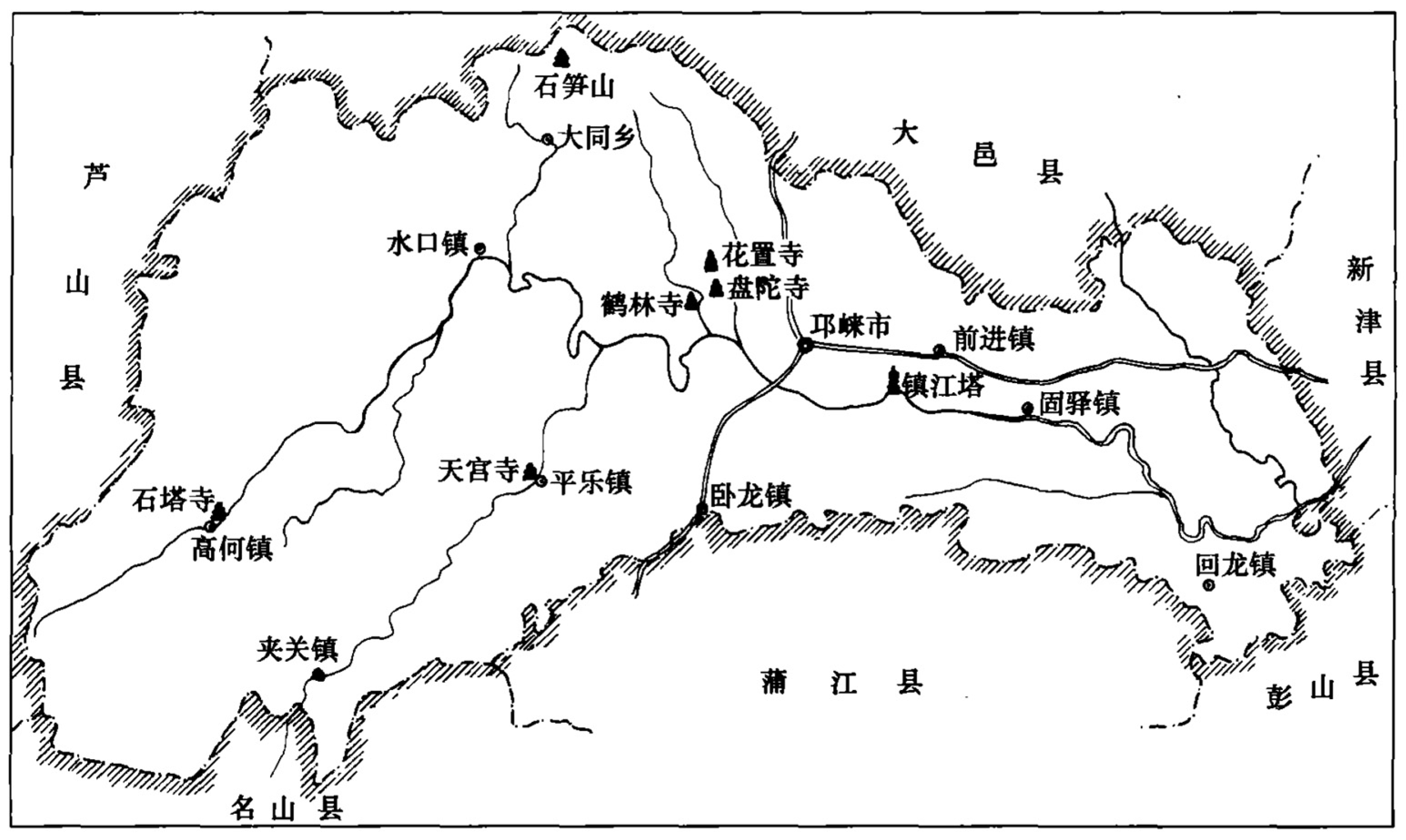

| 2 | For further insight into the reports on the Buddhist carvings at Mount Shisun, see (Sichuan daxue yishu xueyuan et al. 2005b, pp. 506–25). |

| 3 | For further insight into the reports on the Buddhist carvings at Helin Temple, see (Sichuan daxue yishu xueyuan et al. 2005c, pp. 526–50). |

| 4 | For the complete report of the cliff statues at Pantuo Temple and Huazhi Temple in Qionglai, see (Sichuan daxue yishu xueyuan et al. 2005a, pp. 489–505). The serial numbers of Huazhi Temple niches cited in this article are taken from this report. In addition, several other studies that refer to the cliff statues at Huazhi Temple are also referred to: (Huang 1987, pp. 10–14; Huang 1990, pp. 146–52; Lu et al. 2006, pp. 343–58; Hu 1994, pp. 25–26; Hu and Hu 2015, pp. 407–8). The material on Huazhi Temple in Hu’s two books are almost identical, and so my discussion will be focused on the main points in (Hu 1994). |

| 5 | The report on the Buddhist carvings at Tiangong Temple is (Sichuan daxue yishu xueyuan et al. 2006, pp. 485–509). |

| 6 | I conducted fieldwork at the Huazhi Temple in 2013. |

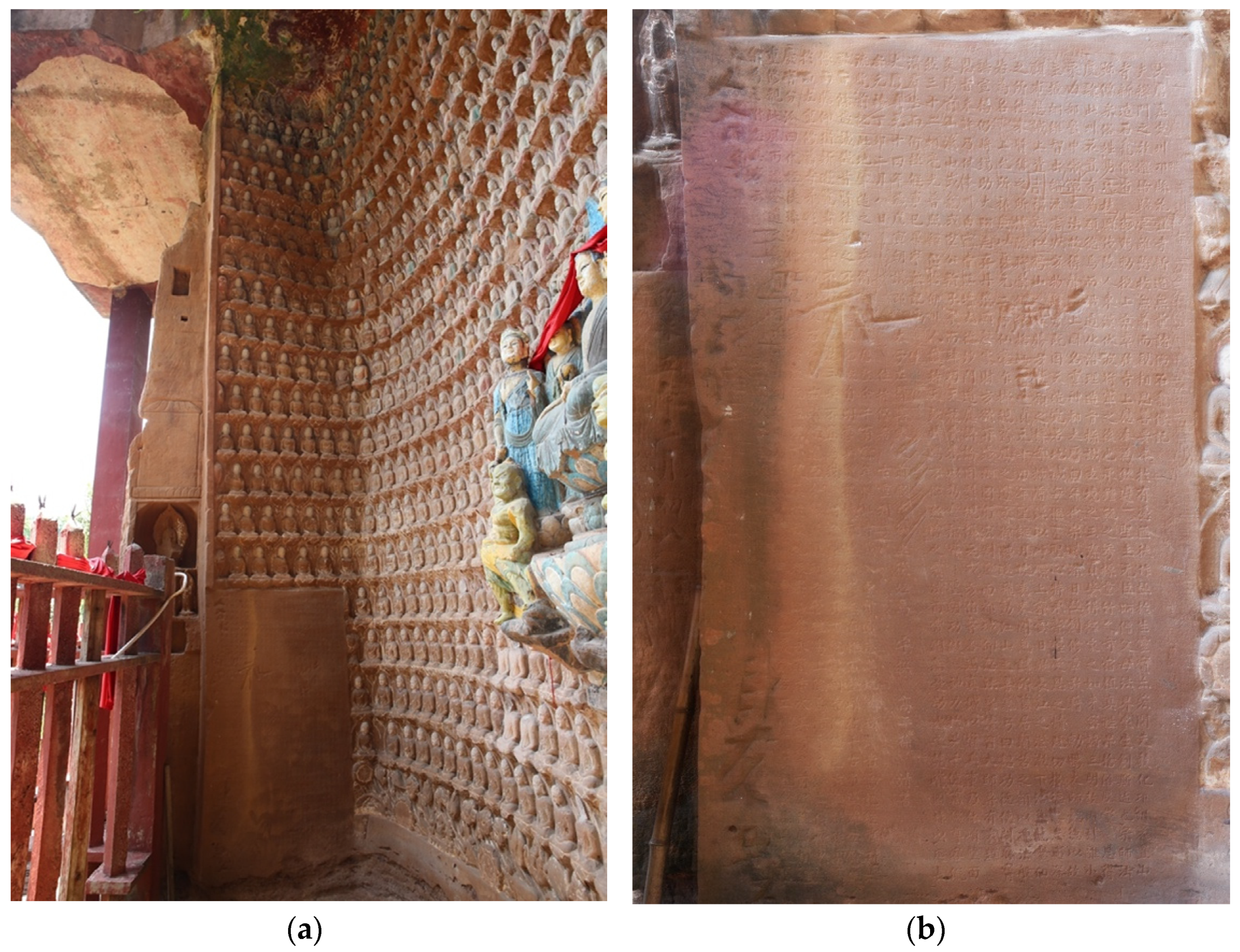

| 7 | Both Niche 5 and Niche 6 at the Huazhi Temple are in two layers. Niche 5 is of 675 cm height, 520 cm width and 50 cm depth (of the outside niche) and is of 640 cm height, 485 cm width and 200 cm depth (of the inside niche). Niche 6 is of 670 cm height, 490 cm width and 4cm depth (of the outside niche) and is of 620 cm height, 455 cm width and 132 cm depth (of the inside niche). These measurements are taken from (Lu et al. 2006, pp. 349–50). |

| 8 | For the research of the Niche 3 at Huazhi temple, see (Hamada 2016, pp. 75–83). I am grateful to Hamada Tamami for sharing this paper with me. |

| 9 | The completed texts of the inscription of the stone tablet on the right wall inside of Niche 6 at Huazhi temple (without punctuation), see (Sichuan daxue yishu xueyuan et al. 2005a, pp. 501–2; Lu et al. 2006, pp. 351–2). The text in 2005a contains many mistakes; while some characters were corrected in the latter report (Lu et al. 2006), the text is still problematic. For the punctuated text of inscriptions deriving from the Tang and Song Dynasties, see (Huang 1987, pp. 13–14) (hereafter “Huang’s 1987 text ”) and (Huang 1990, pp. 150–2) (hereafter “Huang’s 1990 text”). |

| 10 | In this article, “right” and “left” refer to the directions of the niches and statues. |

| 11 | (Hida 2005, pp. 73–90). Hida’s research on the 798 Account is also included in Section 3 (“Hanaki ji Magai zōzō no kaisaku to Chōan Bukkyō” 花置寺摩崖造像の開鑿と長安仏教) of (Hida 2007, pp. 194–205). The Tang Dynasty’s text account from Hida 2007 is slightly revised on the basis of Hida 2005 for the sake of accuracy (e.g., “jide zhi zhi” 扱德之志 is changed to “baode zhi zhi” 报德之志). But there are no major differences in terms of the research contents on the 798 Account between these two articles. Hida’s Tang Dynasty’s textual account was much improved in accuracy, when compared with the texts from Lu et al. (2006, pp. 351–2), as mentioned in note 9. I therefore consult the text of the 798 Account from (Hida 2007, p. 197) (hereafter “Hida’s 2007 text ”) and Hida’s research in (Hida 2005). |

| 12 | Dezong was born on the guisi (nineteenth) day of the fourth lunar month of the first year of Tianbao 天寶 era (Tianbao 1.4.19). See Cefu yuangui 2.22. This lunar date translates to May 27, 742. |

| 13 | The 798 Account was carved inside Niche 6 and Niches 5 and 6 were connected as a whole niche. It is beyond all doubt that Niches 5 and 6 of the Thousand Buddha statues were in Sengcai’s statue construction project at Huazhi temple. However, some other niches at this site could possibly belong to Sengcai’s statue construction project as well. So, I will use Buddhist statues and (or) niches in a broad way, instead of Thousand Buddha Niches, to refer to the contents of Sengcai’s statue construction project at Huazhi temple. |

| 14 | Gaoping might be Xu Qing’s ancestral home, which implied that Xu Qing was from the Xu family of Gaoping in Shanxi. This does not mean that Xu Qing was based in Gaoping when he performed the calligraphy for the 798 Account. |

| 15 | See (Liu 2007, pp. 252–3) for the details of her argument. |

| 16 | Jiu Tangshu 184. 4764; Tang huiyao 48. 847; Zizhi tongjian 224. 7195. |

| 17 | Cefu yuangui 52. 547. |

| 18 | Cefu yuangui 52. 546; Zizhi tongjian 224. 7198; Cefu yuangui 459. 5179. |

| 19 | |

| 20 | Cefu yuangui 2. 19–20; Song Gaoseng zhuan, T no 2061, 50: 10. 767c26–768a6. As Daizong died on the twenty-first day of the fifth lunar month of the fourteenth year of Dali era (June 10, 779) (Jiu Tangshu 12. 319), the last time to celebrate his birthday would be in 778. |

| 21 | Datang Zhenyuan xu Kaiyuan Shijiao lu, T no. 2156, 55: 2.758b21-c19. |

| 22 | Daizong chao zeng sikong Da bianzheng Guangzhi sanzang heshang biaozhi ji, T no 2120, 52: 6. 856c20-857b24; (Wang 2022, pp. 363–6). |

| 23 | Jiu Tangshu 133. 3669; (Wang 2009, p. 41). |

| 24 | Tang huiyao 49. 860. |

| 25 | Song Gaoseng zhuan, T no 2061, 50: 16. 806b16-25. |

| 26 | Cefu yuangui 52. 548. |

| 27 | Datang Zhenyuan xu Kaiyuan Shijiao lu, T no. 2156, 55: 1. 757b3-6. |

| 28 | Jiu Tangshu 13.372; Cefu yuangui 114. 1243. |

| 29 | Song Gaoseng zhuan, T no 2061, 50: 10.767c25-768a6. |

| 30 | Song Gaoseng zhuan, T no 2061, 50: 9.764b14-c13; Lü Wen 呂溫 (771–811), “Nanyue Mituosi Chengyuan heshang bei” 南嶽彌陀寺承遠和尚碑 [Epitaph for Preceptor Chengyuan of Mituo Temple on Nanyue], Quan Tangwen 630.6355: “大曆末, 門人法照辭謁五台, 北轅有聲, 承詔入覲, 壇場內殿, 領袖京邑”. |

| 31 | Li Jifu 李吉甫, “Hangzhou Jingshan si Dajue chanshi beiming bing xu” 杭州徑山寺大覺禪師碑銘并序 [Epitaph, with a Preface, for Chan Master Dajue of Jingshan Temple in Hangzhou] (dated 793), Quan Tangwen 512.5206-5208: “(法欽) 尋求歸山, 詔允其請, 因賜策曰‘國一大師’, 仍以所居為徑山寺焉”. |

| 32 | Cefu yuangui 52.548. |

| 33 | Song Gaoseng zhuan, T no 2061, 50: 16.806b16-25. |

| 34 | Datang Zhenyuan xu Kaiyuan Shijiao lu, T no. 2156, 55: 2.765b28-c4. |

| 35 | See Note 33 above. |

| 36 | Liu Zongyuan 柳宗元 (773–819), “Nanyue Mituo heshang bei” 南嶽彌陀和尚碑 [Epitaph for the Monk at Nanyue Mituo], (Zhou 2000: bu 3, vol. 2: 20). |

| 37 | Jingtu wuhui nianfo lüe fashi yizan, T no. 1983, 47: 1.474 c19-23. |

| 38 | Nittō guhō junrei gyōki no kenkyū, B no. 95, vol. 18: 3.88a 13–16 (Kaicheng 開成 6.2.8 = Huichang 1.2.8 = March 4, 841). |

| 39 | (Tao and Tao 2019, pp. 54–55; cf. Zhou 1987, p. 519). For more information on Jianxu and the debating event of three religions on Dezon’s birthday in 796, see (Chen 2004, pp. 137–9). |

| 40 | Quan Tangwen 916.9544. |

| 41 | Zhenyuan Xinding Shijiao mulu, T no. 2157, 55: 16.887a27-888c13. |

| 42 | Zhenyuan Xinding Shijiao mulu, T no. 2157, 55: 16.887a27-888a11. |

| 43 | “Qing Huilin fashi yu Baoshou si jiang biao yishou” 請惠林法師於保壽寺講 表一首 [A Memorial on Inviting Dharma Master Huilin to Lecture at Baoshou Temple], Daizong chao sikong Da Bianzheng Guangzhi sanzang heshang biaozhi ji, T no. 2120, 52: 2.838a17-b1. |

| 44 | “Qing Jingcheng liangjie gezhi yisi jiang zhi yishou” 請京城兩街各置一寺講 制一首 [A Decree on the Entreating to Select a Temple in Each of Two Precincts of the Capital to Lecture (on the Xukongzang pusa suowen jing)], Daizong chao sikong Da Bianzheng Guangzhi sanzang heshang biaozhi ji, T no. 2120, 52: 3.842a15-25. |

| 45 | “Xie enming ling Youze fashi yu Xingshan si kaijiang biao yishou (bingda)” 謝恩命 令有則法師於興善寺開講 表一首(并答) [A Memorial (with an Imperal Response) from Dharma Master Youze to Express Gratitude to the Imperial Order of Opening Lectures at Xingshan Temple], Daizong chao sikong Da Bianzheng Guangzhi sanzang heshang biaozhi ji, T no. 2120, 52: 6.859b29-c16. |

| 46 | Da Tang Zhenyuan xu Kaiyuan Shijiao lu, T no. 2156, 55: 2.760a18-762c7. |

| 47 | Dacheng liqu liu boluomiduo jing, T no. 261, 8: 1. 865b4-12. Wang Shenbo 王申伯, “Tang gu nei gongfeng fanjing yijie jiang lülun fashi Biankong heshang taming” 唐故内供奉翻經義解講律論法師䛒空和上塔銘 [Stupa Epitaph for the Late Preceptor Biankong of the Tang, Who was a Palace Chaplain, a Translator, a Commentator, a Vinaya and Śāstra Lecturer and a Dharma Master], Quan Tangwen 614.6205-6206. |

| 48 | Da Tang Zhenyuan xu Kaiyuan Shijiao lu, T no. 2156, 55: 2.764a15-c24. |

| 49 | Da Tang Zhenyuan xu Kaiyuan Shijiao lu, T no. 2156, 55: 1.757b3-6. |

| 50 | Da fangguang fo huayan jing, T no. 293, 10: 40.848c14-849a8. |

| 51 | (Yu 2019). Lidai minghua ji 3. 53–54: “千福寺 (在安定坊, 會昌中毁寺後, 却置不改舊額) ...... 向裏面壁上碑 (吴通微書, 僧道秀撰)”. |

| 52 | Jiu Tangshu 153. 4089–4090; Xin Tangshu 162. 5002; Zizhi tongjian 239.7700. |

| 53 | Yuanzhao, “Foshuo shili jing Da Tang Zhenyuan xinyi shidi deng jing ji“ 佛說十力經大唐貞元新譯十地等經記, in Foshuo shili jing, T no. 780, 17: 717a21-28. |

| 54 | When Hida summarized the 798 Account, she also speculated that shangying 上應 might have been an error for shangzuo 上座; however, she did not elaborate on her hypothesis. See (Hida 2005, p. 83). |

| 55 | Tang liudian 4.125: “凡天下寺,總五千三百五十八所 (三千二百四十五所僧,二千一百一十三所尼). 每寺上座一人, 寺主一人, 都維那一人, 共綱統衆事”. |

| 56 | See Note 42 above. |

| 57 | Zhenyuan Xinding Shijiao mulu, T no. 2157, 55: 16.888b16-c13. |

| 58 | For the biography of Huaihui, see Quan Deyu 權德輿 (759–818), “Tang gu Zhangjing si Baiyan dashi beiming bing xu” 唐故章敬寺百巖大師碑銘并序 [The Inscription, with a Preface, for the Late Master Baiyan of Zhangjing Temple of the Tang Dynasty], Quan Tangwen 501.5103-5104; Song Gaoseng zhuan, T no 2061, 50: 10. 767c26-768a12. |

| 59 | Zhenyuan Xinding Shijiao mulu, T no. 2157, 55: 16.887c25-888a7. |

| 60 | For another example of Dezong adding the two-character reigning name of “Zhenyuan” to a Buddhist edifice, see the following record in Tang Huiyao 48.998: “In the fourth month of thirteenth year of Zhenyuan era (797), it was decreed that it is fit to bestow on the Maitreya pavilion 彌勒閣 in the south of Qujiang 曲江 the name of ‘Zhenyuan Puji si’ 貞元普濟寺 (貞元十三年四月勅: “ ‘曲江南彌勒閣’宜賜名‘貞元普濟寺’”). |

| 61 | On the fifth day of eleventh lunar month of nineteenth year of Zhenyuan era (Zhenyuan 19.11.5 = December 22, 803), Wei Gao reported in his “Jiazhou Lingyun si da Mile fo shixiang ji” 嘉州凌雲寺大彌勒佛石像記 [The Record of the Stone Statue of Giant Maitreya Buddha at Lingyun Temple in Jiazhou]: “During the Kaiyuan era, there was further an imperial edict of bestowing the revenues of linen and salt to defray the construction costs” (開元中, 又有詔賜麻鹽之稅, 實資修營) (Long 2004, p. 45). |

| 62 | Scholars debate on the overall height of the “Leshan Colossal Buddha”, ranging from 58.2 m to 71 m. See (Hu and Hu 2015, pp. 438–39). |

| 63 | For a study of the monastic lands, see (Gernet 1995, pp. 94–141). |

| 64 | (Gernet 1995, pp. 43, 45) (with Wades romanizations converted into the pinyin). |

| 65 | Song Gaoseng zhuan, T no 2061, 50: 24. 864c28-865a4. |

| 66 | For researches of the Commissioner of Merit and Virtue, see (Tsukamoto 1975, pp. 252–84; Tang 1985, pp. 60–65; Goble 2022, pp. 66–86). |

| 67 | Da Tang Zhenyuan xu Kaiyuan Shijiao lu, T no 2156, 55:2. 764a18-c16. |

| 68 | See Note 105. |

| 69 | https://www.zdic.net/hans/元戎; https://www.zdic.net/hans/方伯 Visited on 24 August 2021. Shijing 詩經, “Liuyue” 六月, in Taiwan Kaiming Shuju (ed.) 1991: 45: “元戎十乘,以先啓行.” Sangguo zhi 30.591: “且今州牧郡守,古之方伯諸侯,皆跨有千里之土,兼軍武之任.”. |

| 70 | For the complete inscription of this lampstand, see (Cheng 1983, p. 28). |

| 71 | According to Liu Shufen’s research, hui 會 or yihui 邑會 were new names that appeared in the Tang Dynasty, whose characteristics were similar to she 社 or yi 邑. The example she cited is “Baijia yan si yiji” 百家巖寺邑記 [The Records of Association at Baijia Peak Temple] dated to the fifth year of Xiantong 咸通 era (864), which recorded that this Buddhist organization was constituted by a Commander, Administrative Assistant, and so on. See (Liu 2007, pp. 274–75). The identities of the members who constituted the association mentioned by Liu were similar to those of the members who set up the lampstand at Longxing Temple in Qionglai. |

| 72 | Jiu Tangshu 11.271. |

| 73 | Xin Tangshu 222.6317. |

| 74 | In regard to Wei Gao’s support for Buddhism, see (He 2012, pp. 154–59). |

| 75 | As noted above, Wei Gao’s “Jiazhou lingyun si da Mile fo shixiang ji” was dated December 22, 803. See (Long 2004, p. 45). As per the record of Wei Gao himself, Wei Gao started to renew the Giant Maitreya buddha at Lingyun Temple once after he took office in Jiannan Xichuan in 785, and did this by selecting craftsmen and raising money (貞元初, 聖天子命我守茲坤隅, 乃謀匠石, 籌厥庸, 從蓮花座上, 乃至於膝, 功未就者, 幾乎百尺). Then, in the fifth year of the Zhenyuan era (789), Emperor Dezong issued an edict to amend old temples and rebuild abandoned temples (貞元五年有詔, 郡國伽藍, 修舊起廢). It was against this historical backdrop that Wei Gao offered 500,000 cashes to make the “Leshan Giant Buddha” more magnificent by adding color and gold to it (遂命工徒, 以俸錢五十萬佐費, 或丹彩以章之, 或金寶以嚴之). The Chinese texts here are from (Long 2004, p. 45), but punctuations are mine. |

| 76 | Wei Gao wrote “Baoyuan si chuanshou pini xinshu ji” 寶園寺傳授毗尼新疏記 [The Record of New Commentary on the Vinaya Instructed at Baoyuan Temple] on the first day of the eleventh month of the eighteenth year of Zhenyuan era (Zhenyuan 18.11.1 = November 29, 802). See (Long 2004, pp. 43–44). |

| 77 | Wei Gao also wrote “Baoli si ji” 寶曆寺記 [An Account of Baoli Temple]; see (Long 2004, pp. 47–48). On the basis of Wei Gao’s official position, Li Dongmei and Long Xianzhao deduced that “Baoli si ji” was written during the seventeenth year to twentieth year of the Zhenyuan era (801–804). In addition, Ōshima Sachiyo, inferred that Baoli Temple was built in the twentieth year of the Zhenyuan era (804). See (Ōshima 2007, pp. 246–68). |

| 78 | Da fangguang fo huayan jing, T no. 293, 10: 40.848c14-849a16: 大唐貞元十四年, 歲在戊寅, 四月辛亥朔, 翻經沙門圓照, 用恩賜物, 奉為皇帝聖化無窮, 太子諸王福延萬葉, 文武百官恒居祿位. 伏願先師考妣上品往生, 法界有情同霑斯益. 手自書寫此新譯經, 填續西明寺菩提院東閣一切經闕. 本願千佛出世, 隨侍下生, 同出苦源, 齊登正覺; 又願三寶增明, 法輪恒轉, 長留鎮寺, 永冀傳燈, 有情界窮, 茲願無盡. |

| 79 | For more information of the drought disaster in Chang’an in 798, see Xin Tangshu 35.917, Jiu Tangshu 129.3603-3604. Lü Wen also composed a poem titled “Zhenyuan shisi nian hanshen jian quanmen yi shaoyao hua” 貞元十四年旱甚, 見權門移芍藥花 [When there was a drought in the 14th year of the Zhenyuan era, I saw Peony Blossoms Moving in Mansions], Quan Tang shi 371.4188: 綠原青壟漸成塵, 汲井開園日日新. 四月帶花移芍藥, 不知憂國是何人. |

| 80 | For more infomation on the Buddhist statue tablets from the Southern dynasties in Chengdu which represent a jar in the central bottom, see (Sichuan bowuyuan et al. 2013, pp. 102–10, 160–67, 180–82, 205–8; Dong and Yan 2021, pp. 188–213). |

| 81 | |

| 82 | Cui Yan 崔郾 (768–836), “Li Yi muzhi” 李益墓志 [The Epitaph of Li Yi], in (Zhao and Zhao 2012, p. 931). |

| 83 | Xin Tangshu 58.1484. |

| 84 | Tang huiyao 36.771; Cefu yuangui 556.6379. |

| 85 | “Mishu shaojian shiguan xiuzhuan majun muzhi”, Quan Tangwen 639.6452. |

| 86 | Yin and Han eds. 2013. Liu Zongyuan ji jiaozhu 16.1144-1146. See (Yin and Han 2013). |

| 87 | Huang’s 1987 text & Huang’s 1990 text: “虽”;Hida’s 2007 text: “雖”. 雖 doesn’t seem making sense. |

| 88 | Huang’s 1987 text, Huang’s 1990 text, and Hida’s 2007 text: “无”. Seems not right. |

| 89 | Huang’s 1987 text: “永”;Huang’s 1990 text & Hida’s 2007 text: “承”. |

| 90 | Huang’s 1987 text: “  ”; Huang’s 1990 text: no word recognized; Hida’s 2007 text: ”; Huang’s 1990 text: no word recognized; Hida’s 2007 text:  . Neither Huang nor Hida recognized the standard character of this word. I appreciate Ji Yun’s 紀贇 help in deciphering this character. . Neither Huang nor Hida recognized the standard character of this word. I appreciate Ji Yun’s 紀贇 help in deciphering this character. |

| 91 | Huang’s 1987 text & Huang’s 1990 text: “象”; Hida’s 2007 text: 衆. |

| 92 | Huang’s 1987 text & Huang’s 1990 text: “驰”; Hida’s text: “馳”. When I conducted field survey at Huazhi Temple in 2013, this character did not exist. Referring to Huang’s and Hida’s texts, “shengchi shangguo” 聲馳上國 is in line with the context. So, I have adopted Huang’s and Hida’s reading and accepted this character as chi 馳. |

| 93 | In Classical Chinese, wangji 罔極 indicates boundless parental love and kindness towards their children and also one’s endless grief for the passing of one’s parent(s). In the seventh month of Dali 3 (August 17–September 15, 768), Daizong, honoring his deceased mother, decreed that ullambana bowls be sent to Zhangjing Temple, which was then newly completed (七月, 特賜章敬寺盂蘭盆. 時寺宇新成, 帝增罔極之思, 敕百官詣寺行香). See Cefu yuangui 52:547 and Chen 2010, p. 197. In addition, Xingtang Temple興唐寺 in Chang’an was originally named Wangji Temple 罔極寺. It was built by Princess Taiping 太平 (?–713) for the posthumous well-being of her mother Empress Wu, in accordance with a decree Zhongzong issued on April 9, 705 (Chen 2010, p. 188). Given that Zhangjing Temple was named after Daizong’s mother, I suspect that riji 日極, which makes no sense in the context, is probably an error for wangji 罔極. It was likely that the character wang 罔 was somewhat mistakenly carved as ri 日 when this stone tablet was re-engraved after the Tang dynasty. As mentioned before, the characters of shangzuo 上座 were likely mis-carved as shangying 上應. |

| 94 | Huang’s 1987 text: “报”; Huang’s 1990 text: “极”; Hida’s 2007 text: “極”. |

| 95 | Huang’s 1987 text: “无”;Huang’s text 1990: “天”; Hida’s 2007 text: “天”. |

| 96 | Huang’s 1987 text: “报”;Huang’s text 1990: “极”; Hida’s 2007 text: “报”. |

| 97 | Huang’s 1987 text: “惬”;Huang’s text 1990 & Hida’s 2007 text: no word recognized. |

| 98 | Huang’s 1987 text & Huang’s 1990 text: “插”; Hida’s 2007 text: no word recognized. |

| 99 | Huang’s 1987 text & Huang’s 1990 text: no word recognized; Hida’s 2007 text: “  ”. ”. |

| 100 | Huang’s 1987 text & Huang’s 1990 text: “何”; Hida’s 2007 text: no word recognized. |

| 101 | Huang’s 1987 text & Huang’s 1990 text: “字”; Hida’s 2007 text: no word recognized. |

| 102 | Huang’s 1987 text & Huang’s 1990 text: “宝”; Hida’s 2007 text: “竇”. On the pictures of stone tablets, indeed this character is shown as bao 寶 nowadays. But according to the context, I agree with Hida’s recognition of this character as dou 竇. It was very likely possible that dou 竇 was the original character in the Tang Dynasty and it was mistakenly carved as bao寶 in the later dynasties. |

| 103 | Huang’s 1987 text: “诏”;Huang’s 1990 text: “诰”; Hida’s 2007 text: “誥”. |

| 104 | Huang’s 1987 text & Huang’s 1990 text: “象”; Hida’s 2007 text: “衆”. |

| 105 | Huang’s 1987 text: “戎”; Huang’s 1990 text: “戏”; Hida’s 2007 text: “戒”. Huang first presented this character as rong 戎, but later changed it to xi 戏, showing that Huang did not know that yuanrong 元戎 is a fixed term. So, both Huang and Hida failed to read the character rong 戎 and further to capture the meaning of yuanrong 元戎. |

| 106 | Huang’s 1987 text, Huang’s 1990 text and Hida’s 2007 text: no word recognized. |

| 107 | Huang’s 1987 text: “无”; Huang’s 1990 text & Hida’s 2007 text: “天”. |

| 108 | Huang’s 1987 text: “火”; Huang’s 1990 text: “灭”; Hida’s 2007 text: “火”. |

References

Primary Sources

Cefu yuangui冊府元龜 [The Prime Tortoise of the Record Bureau]. 1000 juan. Compiled by Wang Qinruo 王欽若 (962–1025) and others between 1005–1013. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju中華書局, 1994.Da fangguang fo huayan jing 大方廣佛華嚴經 [Skt. Avataṃsaka Sūtra]. 40 juan. Translated by Prajñā 般若 (?–?) between 795–798. T vol. 10, no. 293.Da Tang Zhenyuan xu Kaiyuan Shijiao lu 大唐貞元續開元釋教錄 [Extended Zhenyuan Catalog of Buddhist Texts of Great Tang Dynasty]. 3 juan. Compiled by 圓照 (727–809) between 794–795. T vol. 55, no. 2156.Daizong chao zeng Sikong Dabianzheng Guangzhi sanzang heshang biaozhi ji 代宗朝贈司空大辨正廣智三藏和上表制集 [Collected Memorials of the Tripiṭaka Master of Guangzhi, Dabianzheng, Grand Minister, under Daizong’s Reign]. 6 juan. Compiled by 圓照 (727–809) between 778–793. T vol. 52, no. 2120.Foshuo shili jing 佛說十力經 [Scripture on the Ten Powers]. 1 juan. Translated by Wutitixiyu 勿提提犀魚 (Utpalavīrya; d.u.). T vol. 17, no. 780.“Hangzhou Jingshan si Dajue chanshi beiming bing xu” 杭州徑山寺大覺禪師碑銘并序 [Epitaph, with a preface, for Chan Master Dajue of Jingshan Temple in Hangzhou]. By Li Jifu 李吉甫 (758–814). Wenyuan yinghua 865.4563–4565.Jingtu wuhui nianfo lüe fashi yizan 淨土五會念佛略法事儀讚 [Ritual Praises for the Dharma Ceremony Outlining the Five Stage Progression for Chanting the Buddha’s Name of Pure Land]. 1 juan. Dictated by Fazhao法照 (747–821) between 767–777. T vol. 47, no. 1983.Jiu Tangshu 舊唐書 [Old Tang History]. 200 juan. Compiled by Liu Xu 劉昫 (887–946). Beijing: Zhonghua shuju 中華書局, 1975.“Mishu shaojian shiguan xiuzhuan Majun muzhi” 秘書少監史館修撰馬君墓誌 [The Epitaph of Mr. Ma who was the Vice Director of the Palace Library and Senior Compiler in the Historiography Institute]. By Li Ao 李翱 (774–836). Quan Tangwen 639.6452.“Nanyue Mituo si Chengyuan heshan bei” 南嶽彌陀寺承遠和尚碑 [Epitaph for Preceptor Chengyuan of Mituo Temple at Nanyue]. By Lü Wen 呂溫 (771–811). Quan Tangwen 630.6354-6356.Nittō guhō junrei gyōki no kenkyū 入唐求法巡禮行記 [The Record of a Pilgrimage to China in Search of the Law]. 4 kan, by Ennin 圓仁 (793–864). B no. 95,vol. 18.Quan Tangwen 全唐文 [Complete Tang Prose Writings]. 1,000 juan. Compiled by Dong Gao 董誥 (1740–1818) and others between 1808–1814. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju 中華書局, 1983.Quan Tangshi 全唐詩 [Complete Tang Poems]. 912 juan. Compiled by Peng Dingqiu 彭定求 (1645–1719) and others. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju 中華書局, 1999.Sangguo zhi 三國志 [Records of the Three Kingdoms]. 65 juan. By Chen Shou 陳壽 (233–297). Beijing: Zhonghua shuju 中華書局, 1959.Shunzong shilu 順宗實錄 [The Veritable Record of Emperor Shunzong]. 5 juan. By Han Yu 韓愈 (768–824).Song Gaoseng zhuan 宋高僧傳 [Biographies of Eminent Monks Compiled during the Song Dynasty]. 30 juan. By Zanning 贊寧 (919–1001) and others. T vol. 50, no. 2061.“Tang gu Zhangjing si Baiyan dashi beiming bing xu” 唐故章敬寺百巖大師碑銘并序 [Epitaph, with a Preface, for the Late Great Master Baiyan of Zhangjing Temple in the Tang Dynasty]. By Quan Deyu 權德輿 (759–818). Quan Tangwen 501.5103-04.Tang huiyao 唐會要 [Essentials of the Tang]. 100 juan. Compiled by Wang Pu 王溥 (922–982). Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe 上海古籍出版社, 2016.Wenyuan yinghua 文苑英華 [The Flower of the Garden of Letters]. 1000 juan. Compiled by Li Fang 李昉 (925–996) and others. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju 中華書局, 2003.Xin Tangshu 新唐書 [New History of Tang]. 225 juan. Compiled by Ouyang Xiu 歐陽脩 (1007–1072), Song Qi 宋祁 (998–1061) and others between 1043–1060. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju 中華書局, 1975.Zhenyuan xinding Shijiao mulu 貞元新定釋教目錄 [A Catalogue of the Buddhist Teachings Newly Established in the Zhenyuan Era]. 30 juan. Compiled by 圓照 (727–809) between 799–800. T vol. 55, no. 2157.Secondary Sources

- Cao, Erqin 曹爾琴. 1991. “Tang Chang’an Zhangjingsi de weizhi” 唐長安章敬寺的位置 [Location of Zhangjing Temple in Chang’an of the Tang Dynasty]. Zhongguo lishi dili luncong 中國歷史地理論叢 [Journal of Chinese Historical Geography] 2: 147–50. [Google Scholar]

- Cen, Zhongmian 岑仲勉. 1948. “Hanlin xueshi bi ji zhubu” 翰林學士壁記注補 [Supplementary Annotations on the Notes Left on the Walls of Hanlin Academicians]. Lishi yuyan yanjiu suo jikan 歷史語言研究所集刊 [Bulletin of the Institute of History and Philology, Academia Sinica] 15: 49–223. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Qing 常青. 2016. “Shaanxi Lingyou xian Lamamao shan Qianfo yuan Fojiao zaoxiang diaocha” 陝西麟遊縣喇嘛帽山千佛院佛教造像調查 [An Investigation of Buddhist Images in Qianfo Yuan on Mount Lamamao in Linyou County in Shaanxi]. Kaogu yu wenwu 考古與文物 [Archaeology and Cultural Relics] 3: 34–46. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Jinhua. 2004. The Tang Buddhist Palace Chapels. Journal of Chinese Religions 32: 101–73. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Jinhua. 2010. Crossfire: Shingon-Tendai Strife as Seen in Two Twelfth-Century Polemics, with Special References to Their Background in Tang China. Tokyo: The International Institute for Buddhist Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Enyuan 成恩元. 1983. “Qionglai Tang Longxing si yiwu de faxian yu yanjiu (jieyao)” 邛崍唐龍興寺遺物的發現與研究 (節要) [The Discovery and Research on the Relics from the Tang Dynasty Longxing Temple in Qionglai: An Abridgement]. In Qionglai xian wenwu zhi (diyi ji) 邛崍縣文物志 (第一集) [The Record of the Relics in Qionglai County]. Edited by Qionglai xian wenwu zhi bianweihui 邛崍縣文物志編委會 (in-house literature). vol. 1, pp. 21–34. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Huafeng 董華鋒, and Yuexin Yan 閆月欣. 2021. “Sichuan Nanchao shike “Guan sheng liantai” tuxiang yanjiu” 四川南朝石刻“罐生蓮臺”圖像研究 [Iconographical Study on the Lotus Thrones Emerging from Jars on the Stone Carvings from the Southern Dynasties in Sichuan]. Kaogu xue jikan 考古學集刊 [Collected Essays of Archaeological Studies] 24: 188–213. [Google Scholar]

- Gernet, Jacques. 1995. Buddhism in Chinese Society: An Economic History from the Fifth to the Tenth Centuries. Translated by Franciscus Verellen. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Goble, Geoffrey C. 2022. The Commissioner of Merit and Virtue: Buddhism and the Tang Central Government. In Buddhist Statecraft in East Asia. Edited by Stephanie Balkwill and James A. Benn. Boston: Brill, pp. 66–86. [Google Scholar]

- Hamada, Tamami 濱田瑞美. 2016. “Chūgoku shisen-shō Kyōrai shi Hanaoku ji Magai daisan gan no zuzō ni tsuite: Amida gojūsan butsu no sonzō kōsei o megutte” 中国四川省邛峽(sic)市花置寺摩崖第3龕の図像について:阿弥陀五十三仏の尊像構成をめぐって [The Images of Niche 3 at Huazhi Temple Cliff, Qionglai City, Sichuan Province, China: Focusing on the Composition of the Statues of Amitabha and Fifty-three Buddhas]. Yokohama bijutsu daigaku kyōiku kenkyū kiyō 横浜美術大学教育·研究紀要 [Bulletin of Yokohama College of Art & Design] 6: 75–83. [Google Scholar]

- He, Xiaorong 何孝容. 2012. “Lun Wei Gao yu Fojiao” 論韋皋與佛教 [A Discussion on Wei Gao and Buddhism]. Xi’nan daxue xuebao (Shehui kexue ban) 西南大學學報 (社會科學版) [Bulletin of Xi’nan University: The Social Sciences Pages] 38: 154–9. [Google Scholar]

- Hida, Romi 肥田路美. 2005. “Shisen-shō Kyōrai Hanaoku ji Magai no Senbutsu gan: Sawaji in Nyorai zō no imi o chūshin ni” 四川省邛崍花置寺摩崖の千仏龕——触地印如來像の意味を中心に [The Thousand Buddha’s Niche at Huazhisi in Qionglai, Sichuan: Focusing on the Meaning of the Buddha Performing the Earth-touching Gesture]. Nara bijutsu kenkyū 奈良美術研究 [Nara Fine Arts Studies] 3: 73–90. [Google Scholar]

- Hida, Romi 肥田路美. 2007. “Shisen bonchi Seitan kyō Shū Chiku Magai Zō-zō” 四川盆地西端邛州地区の摩崖造像—立地と内容—[Cliff Statues in Qiongzhou Area, West End of Sichuan Basin: Landmarks and Contents]. In Ajia chiiki bunka-gaku sōsho 5: Bukkyō bijutsu kara mita Shisen ryūiki アジア地域文化学叢書5——仏教美術からみた四川流域 [Asian Regional Cultural Series 5: Buddhist Art Seen from River Basins in Sichuan]. Edited by Nara Bijutsu Kenkyūsho 奈良美術研究所 [Nara Research Institute of Arts]. Tokyo: Yuzankaku 雄山閣, pp. 173–218. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Ji 胡戟, and Xinjiang Rong 榮新江, eds. 2012. Da Tang Xishi bowuguan cang muzhi (zhong) 大唐西市博物館藏墓誌 (中) [Epitaphs collected in Datang Xishi Museum], Vol. 2 (of 3). Beijing: Beijing daxue chubanshe 北京大學出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Wenhe 胡文和. 1994. Sichuan Daojiao Fojiao shiku yishu 四川道教佛教石窟藝術 [The Grotto Art of Daoism and Buddhism in Sichuan]. Chengdu: Sichuan renmin chubanshe 四川人民出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Wenhe 胡文和, and Wencheng Hu 胡文成. 2015. Bashu Fojiao diaoke yishu shi (zhong) 巴蜀佛教雕刻藝術史 (中) [The Art History of Buddhist Carvings in Bashu], Vol. 2 (of 3). Chengdu: Bashu shushe 巴蜀書社. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Weixi 黃微羲. 1987. “Huazhi si shike zaoxiang” 花置寺石刻造像 [The Stone Carvings at Huazhi Temple]. Chengdu wenwu 成都文物 [Cultural Relics of Chengdu] 1: 10–14. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Weixi 黃微羲. 1990. “Huazhi si Fojiao shike zaoxiang” 花置寺佛教石刻造像 [The Buddhist Stone Carvings at Huazhi Temple]. Qionglai wenshi ziliao 邛崍文史資料 [Reference on Qionglai’s Culture and History] 4: 146–52. [Google Scholar]

- Lan, Jifu 藍吉富 comps. 1985. Dazang jing bubian 大藏經補編 [Buddhist Canon: Supplementary Sections]. 36 vols. Taipei: Huayu chubanshe 華宇出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Jingjie 李靜傑. 2023. “Yindu Manping lianhua tuxiang jiqi zai Zhongguo de xin fazhan” 印度滿瓶蓮花圖像及其在中國的新發展 [The Iconography of Full Vase Lotus Flower of India and Its New Development in China]. In Zhonggu zhongxi wuzhi wenhua jiaoliu luncong 中古中西物質文化交流論叢 [Symposium on the Interchange of Chinese and Western Material Culture in the Medieval Times]. Beijing: Kexue chubanshe 科學出版社, pp. 177–212, This article is modified on the basis of the same artile in Dunhuang yanjiu yuan 敦煌研究院 eds. 2016. 2014 Dunhuang luntan: Dunhuang shiku yanjiu guoji xueshu yantaohui lunwenji (xaice) 2014 敦煌論壇——敦煌石窟研究國際學術研討會論文集(下冊) [2014 Dunhuang Forum - Proceedings of the International Symposium on the Research of Dunhuang Caves (Volume 2)]. Lanzhou: Gansu jiaoyu chubanshe 甘肅教育出版社, pp. 783–828. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Jinxiu 李錦綉. 2001. Tangdai caizheng shigao (xiajuan) 唐代財政史稿 (下卷) [The Financial History of the Tang Dynasty (Volume II)]. Beijing: Beijing daxue chubanshe 北京大學出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Yunrou 林韻柔. 2018. “Tangdai siyuan zhiwu jiqi yunzuo” 唐代寺院職務及其運作 [The Positions and Their Operations in the Monasteries of the Tang Dynasty]. In Weijin Nanbeichao Sui Tang shi ziliao 魏晉南北朝隋唐史資料 [Information on the History of Wei, Jin, North and South Dynasties, Sui and Tang Dynasty]. Edited by Wuhan daxue Zhongguo san zhi jiu shiji yanjiusuo 武漢大學中國三至九世紀研究所. Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe 上海古籍出版社, pp. 166–201. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Shufen 劉淑芬. 2007. “Zhonggu Fojiao zhengce yu sheyi de zhuanxing” 中古佛教政策與社邑的轉型 [State Policies and Changes in Medieval Chinese Buddhist Associations]. Tang Yanjiu 唐研究 [Journal of Tang Studies] 13: 241–99. [Google Scholar]

- Long, Xianzhao 龍顯昭. 2004. Bashu Fojiao beiwen jicheng 巴蜀佛教碑文集成 [The Corpus of Buddhist Inscriptions in Bashu]. Chengdu: Bashu shushe 巴蜀書社. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Ding 盧丁, Yuhua Lei 雷玉華, and Romi Hida 肥田路美, eds. 2006. Zhongguo Sichuan Tangdai moya zaoxiang: Pujiang, Qionglai diqu diaocha yanjiu baogao 中國四川唐代摩崖造像——蒲江、邛崍地區調查研究報告 [The Cliff Reliefs of the Tang Dynasty in Sichuan, China: A Research Survey in the Pujiang and Qionglai Areas]. Chongqing: Chongqing chubanshe 重慶出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Ōshima, Sachiyo 大島幸代. 2007. “Seito Takara-reki tera no sōken to hatten” 成都宝暦寺の創建と発展 [Establishment and Development of Baoli Temple in Chengdu]. In Ajia chiiki bunka-gaku sōsho 5: Bukkyō bijutsu kara mita Shisen ryūiki アジア地域文化学叢書5——仏教美術からみた四川流域 [Asian Regional Cultural Series 5: Buddhist Art Seen from River Basins in Sichuan]. Edited by Nara Bijutsu Kenkyūsho 奈良美術研究所 [Nara Research Institute of Arts]. Tokyo: Yuzankaku 雄山閣, pp. 246–68. [Google Scholar]

- Sichuan bowuyuan 四川博物院, Chengdu wenwu kaogu yanjiusuo 成都文物考古研究所, and Sichuan daxue bowuguan 四川大學博物館, eds. 2013. Sichuan chutu Nanchao Fojiao zaoxiang 四川出土南朝佛教造像 [Buddhist Statues of the Southern Dynasties Excavated in Sichuan]. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju 中華書局. [Google Scholar]

- Sichuan daxue yishu xueyuan 四川大學藝術學院 [Art College of Sichuan University], Chengdu shi wenwu kaogu yanjiusuo 成都市文物考古研究所 [Chengdu Antique Archaeology Institute], Riben Zaodaotian daxue wenxuebu 日本早稻田大學文學部 [School of Humanities at Waseda University in Japan], and Qionglai shi wenguansuo 邛崍市文管所 [Institute of Culture Relic Administration in the Qionglai City]. 2005a. “Qionglai Pantuo si he Huazhi si moya zaoxiang diaocha jianbao” 邛崍磐陀寺和花置寺摩崖造像調查簡報 [A Brief Report on the Cliff Statues at Pantuo Temple and Huazhi Temple in Qionglai]. In Chengdu kaogu faxian (2003) 成都考古發現 (2003) [Chengdu Archaeological Discoveries (2003)]. Edited by Chengdu Antique Archaeology Institute 成都市文物考古研究所. Beijing: Kexue chubanshe 科学出版社, pp. 489–505. [Google Scholar]

- Sichuan daxue yishu xueyuan 四川大學藝術學院, Chengdu shi wenwu kaogu yanjiusuo 成都市文物考古研究所, Riben Zaodaotian daxue 日本早稻田大學, and Qionglai wenguansuo 邛崍文管所. 2005b. “Qionglai Shisun shan Moya shike zaoxiang diaocha jianbao” 邛崍石荀(sic)山摩崖石刻造像調查簡報 [A Brief Investigation of Stone Carving Images on Mount Shisun Cliffs in Qionglai]. In Chengdu kaogu faxian (2003) 成都考古發現 (2003) [Chengdu Archaeological Discoveries (2003)]. Edited by Chengdu Antique Archaeology Institute 成都市文物考古研究所. Beijing: Kexue chubanshe 科学出版社, pp. 506–25. [Google Scholar]

- Sichuan daxue yishu xueyuan 四川大學藝術學院, Chengdu shi wenwu kaogu yanjiusuo 成都市文物考古研究所, Qionglai wenguansuo 邛崍文管所, and Riben Zaodaotian daxue 日本早稻田大學. 2005c. “Helinsi Moya shike zaoxiang” 鶴林寺摩崖石刻造像 [Stone Carvings on the Helin Temple Cliffs]. In Chengdu kaogu faxian (2003) 成都考古發現 (2003) [Chengdu Archaeological Discoveries (2003)]. Edited by Chengdu Antique Archaeology Institute 成都市文物考古研究所. Beijing: Kexue chubanshe 科学出版社, pp. 526–50. [Google Scholar]

- Sichuan daxue yishu xueyuan 四川大學藝術學院 [Art College of Sichuan University], Chengdu shi wenwu kaogu yanjiusuo 成都市文物考古研究所 [Chengdu Antique Archaeology Institute], and Riben Zaodaotian daxue wenxuebu 日本早稻田大學文學部 [School of Humanities at Waseda University in Japan]. 2006. “Qionglai Tiangong si moya shike diaocha jianbao” 邛崍天宮寺摩崖石刻調查簡報 [A Brief Report on the Cliff Carvings at Tiangong Temple in Qionglai]. In Chengdu kaogu faxian (2004) 成都考古發現 (2004) [Chengdu Archaeological Discoveries (2004)]. Edited by Chengdu Antique Archaeology Institute 成都市文物考古研究所. Beijing: Kexue chubanshe 科学出版社, pp. 485–509. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Mingli 孫明利. 2016. Sichuan Tang Wudai moya fudiao Guan Wuliangshou jing bian fenxi 四川唐五代摩崖浮雕觀無量壽經變分析 [An Analysis of the Transformation Tableaux of the Sutra of Visualizing Amitayus Buddha as Carved on the Cliffs in Sichuan Area from the Tang and Five Dynasties]. In Shiku yishu yanjiu 石窟藝術研究 [Study on the Grotto Arts] 1. Edited by Maijishan shiku yishu yanjiusuo 麥積山石窟藝術研究. Beijing: Cultural Relics Press 文物出版社, pp. 174–239. [Google Scholar]

- Takakusu, Junjirō 高楠順次郎, and Kaigyoku Watanabe 渡邊海旭, eds. 1924–1934. Taishō shinshū daizōkyō 大正新脩大藏經 [Buddhist Canon Compiled during the Taishō Era (1912–26)]. Tōkyō: Taishō Issaikyō Kankōkai 大正一切經刊行會, Digitized in CBETA (v. 5.2) and SAT Daizōkyō Text Database.

- Tang, Yijie 湯一介. 1985. “Gongdeshi kao: Du Zizhi tongjian zhaji” 功德使考——讀《資治通鑒》札記 [An Investigation of the Gongde shi (Commissioner of Merit and Virtue): A Research Note on Zizhi tongjian]. Wenxian 文献 [Journal of Literature] 2: 60–65. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, Min 陶敏, and Hongyu Tao 陶紅雨, collated and annotated. 2019. Liu Bingke jiahua lu 劉賓客嘉話録 [Complete Collection of Books from [Various] Collectanea] (by Wei Xun 韋絢). Beijing: Zhonghua shuju 中華書局. [Google Scholar]

- Teiser, Stephen F. 1988. The Ghost Festival in Medieval China. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tsukamoto, Zenryū 塚本善隆. 1975. “Tō chūki irai no Chōan no kudokushi” 唐中期以来の長安の功德使 [The Commissioner of Merit and Virtue of Chang’an since the Mid-Tang Dynasty]. In Tsukamoto Zenryū chosaku shū 塚本善隆著作集 [Collected Works of Tsukamoto Zenryū], vol. 3, Chūgoku Chūsei Bukkyō-shi ronkō 中國中世佛教史論考 [An Investigation of Buddhist History of Medieval China]. Tokyo: Daito shuppansha 大東出版社, pp. 255–60. [Google Scholar]

- Tsukamoto, Zenryū 塚本善隆. 1976. “Tō chūki no Jōdokyō: Toku ni Hōshō zenji no kenkyū” 唐中期の浄土教——特に法照禅師の研究 [Teaching of Pure Land in Mid-Tang Dynasty: With a Focus on Dharma Master Fazhao]. In Tsukamoto Zenryū chosaku shū 塚本善隆著作集 [Collected Works of Tsukamoto Zenryū], vol. 4, Chūgoku Chūsei Bukkyō-shi ronkō 中國淨土教史研究 [A Study of the History of the Pure land Teaching in China]. Tokyo: Daito shuppansha 大東出版社, pp. 209–510. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Jing 王靜. 2009. “Chengmen yu dushi: Yi Tang Chang’an Tonghua men weizhu” 城門與都市——以唐長安通化門為主 [City Gates and Cities: With a Focus on the Tonghua Gate in Chang’an of the Tang Dynasty]. Tang Yanjiu 唐研究 [Journal of Tang Studies] 15: 23–50. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Jing 王靜. 2022. “Tang Daizong shiqi de Chang’an zhuyao siyuan yu fojiao huguo” 唐代宗時期的長安主要寺院與佛教護國 [Major Monasteries and Nation Protection of Buddhism in Chang’an Under Emperor Daizong’s Reign of the Tang Dynasty]. In Fojiao de kua diyu kua zongjiao chuanbo——Fu Andun xiansheng bashi mingdan jinian wenji 佛教的跨地域、跨宗教傳播——富安敦先生八十冥誕紀念文集 [Transmission of Buddhism in Asia and Beyond: Essays in Memory of Antonino Forte (1940–2006)]. Edited by Jinhua Chen 陳金華. Singapore: World Scholastic Publishers, pp. 363–67. [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein, Stanley. 1987. Buddhism under the T’ang. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Gang 吳鋼, ed. 1996. Quan Tangwen buyi 全唐文補遺 [Addenda on the Complete Tang Prose Writings]. Xi’an: Sanqin chubanshe 三秦出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Weizhong 楊維中. 2018. “Tang chu fosi ‘san’gang’ mingcheng de queding jiqi paixu ” 唐初佛寺“三綱”名稱的確定及其排序 [Confirmation and Ranking of the Three Cords’ Names in Buddhist monasteries in the Early Tang Period]. Zongjiaoxue yanjiu 宗教學研究 [Religious Studies] 3: 76–83. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, Zhanhua 尹占華, and Wenqi Han 韓文奇, eds. 2013. Liu Zongyuan ji jiaozhu 柳宗元集校註 [Collation and Annotation of Liu Zongyuan’s Collected Works]. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju 中華書局. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Jianhua 俞劍華 collated and annotated. 2019. Lidai minghua ji 歷代名畫記 [A Record of the Famous Paintings of All the Dynasties]. Hangzhou: Zhejiang renmin meishu chubanshe 浙江人民美術出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Huaqing 余華慶, and Tinghao Zhang 張廷皓, eds. 2006. Shaanxi beishi jinghua 陝西碑石精華 [The Quintessence of Tablets and Stones in Shaanxi]. Xi’an: Sanqin chubanshe 三秦出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Junping 趙君平, and Wencheng Zhao 趙文成. 2012. Qin Jin Yu xinchu muzhi souyi 秦晉豫新出墓誌搜佚 [The Collection of New Unearthed Epitaphs from Qin (Shaanxi), Jin (Shanxi) and Yu (He’nan)]. Beijing: Guojia tushuguan chubanshe 國家圖書館出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Shaoliang 周紹良, ed. 2000. Quan Tangwen xinbian 全唐文新编 [New Compilation of Tang Prose Writings]. 22 vols in 5 bu 部 (Series); Changchun: Jilin wenshi chubanshe 吉林文史出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Shaoliang 周紹良, and Chao Zhao 趙超. 2001. Tangdai muzhi huibian xuji 唐代墓誌彙編續集 [A Sequel Compilation of the Epitaphs in the Tang Dynasty]. Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe 上海古籍出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Xunchu 周勛初, collated and annotated. 1987. Tang Yulin jiaozheng 唐語林校證 [Tang Yulin (Forest of discussions about the Tang Period): Collated and Verified]. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju 中華書局. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sun, M. A Forgotten Eminent Buddhist Monk and His Social Network for Constructing Buddhist Statues in Qionglai 邛崍: A Study Based on the Statue Construction Account in 798. Religions 2024, 15, 412. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15040412

Sun M. A Forgotten Eminent Buddhist Monk and His Social Network for Constructing Buddhist Statues in Qionglai 邛崍: A Study Based on the Statue Construction Account in 798. Religions. 2024; 15(4):412. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15040412

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Mingli. 2024. "A Forgotten Eminent Buddhist Monk and His Social Network for Constructing Buddhist Statues in Qionglai 邛崍: A Study Based on the Statue Construction Account in 798" Religions 15, no. 4: 412. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15040412

APA StyleSun, M. (2024). A Forgotten Eminent Buddhist Monk and His Social Network for Constructing Buddhist Statues in Qionglai 邛崍: A Study Based on the Statue Construction Account in 798. Religions, 15(4), 412. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15040412