2. Financial Stability—Introduction to the Issue

The concept of financial stability most often appears in macroeconomic terms and is identified based on the stability of the financial system. The concept of financial system stability can be defined from the point of view of the functions performed by the financial system. In this context, financial system stability indicates “a state in which the financial system performs its functions continuously and effectively, even in the event of unexpected and unfavorable disturbances of a significant scale” (

Narodowy Bank Polski 2023). In turn,

Mitrović Mijatović (

2013) perceives the stability of the financial system through the stability of its elements, i.e., financial markets and institutions.

Some authors define the stability of the financial system as opposed to the concept of “financial instability”. For example,

Allen and Wood (

2006) describe financial stability as a situation with a low probability of financial instability, which

Davis (

2003) defines as an increased risk of a financial crisis.

Mishkin (

1997) goes a step further by defining the instability of the financial system in relation to the financial sphere and the real economy. Financial instability in this approach means a situation in which shocks occurring in the financial system disrupt the flow of information in such a way that the financial system is unable to perform its key function, i.e., the effective allocation of capital.

In the literature on this subject, one can find definitions of financial stability from a microeconomic perspective.

Gorczyńska (

2013) describes a financially stable company as one that operates on purpose despite disruptions. It is able to withstand shocks without deviating from the path of development. Financial stability allows the enterprise to fully implement economic functions related to raising capital; dividing it; and using it appropriately in operational, investment, and financial activities.

Pikhotskyi et al. (

2019) understand the concept of the financial stability of a company in a similar way. They describe financial stability as the ability of an enterprise to function and develop in a changing business environment, despite disruptions. A stable company is therefore able to achieve its goals and meet its obligations through the effective use of financial resources.

From the microeconomic perspective, financial stability is also identified based on possession and a constant ability to generate a surplus of revenues over expenses in an amount that allows an entity to function freely and achieve its goals. A financially stable company is therefore able to maintain financial liquidity at an appropriate level and properly manage its debt. The determinants of the level of an entity’s financial stability are therefore the sizes and types of revenues, the scopes and structures of expenses, and the sources and costs of obtaining external capital.

In the case of the Catholic Church, the issue of financial stability may concern the church as a whole or its individual organizational units (e.g., parishes).

3. Model of Financing the Catholic Church in Germany in the Context of Its Stability

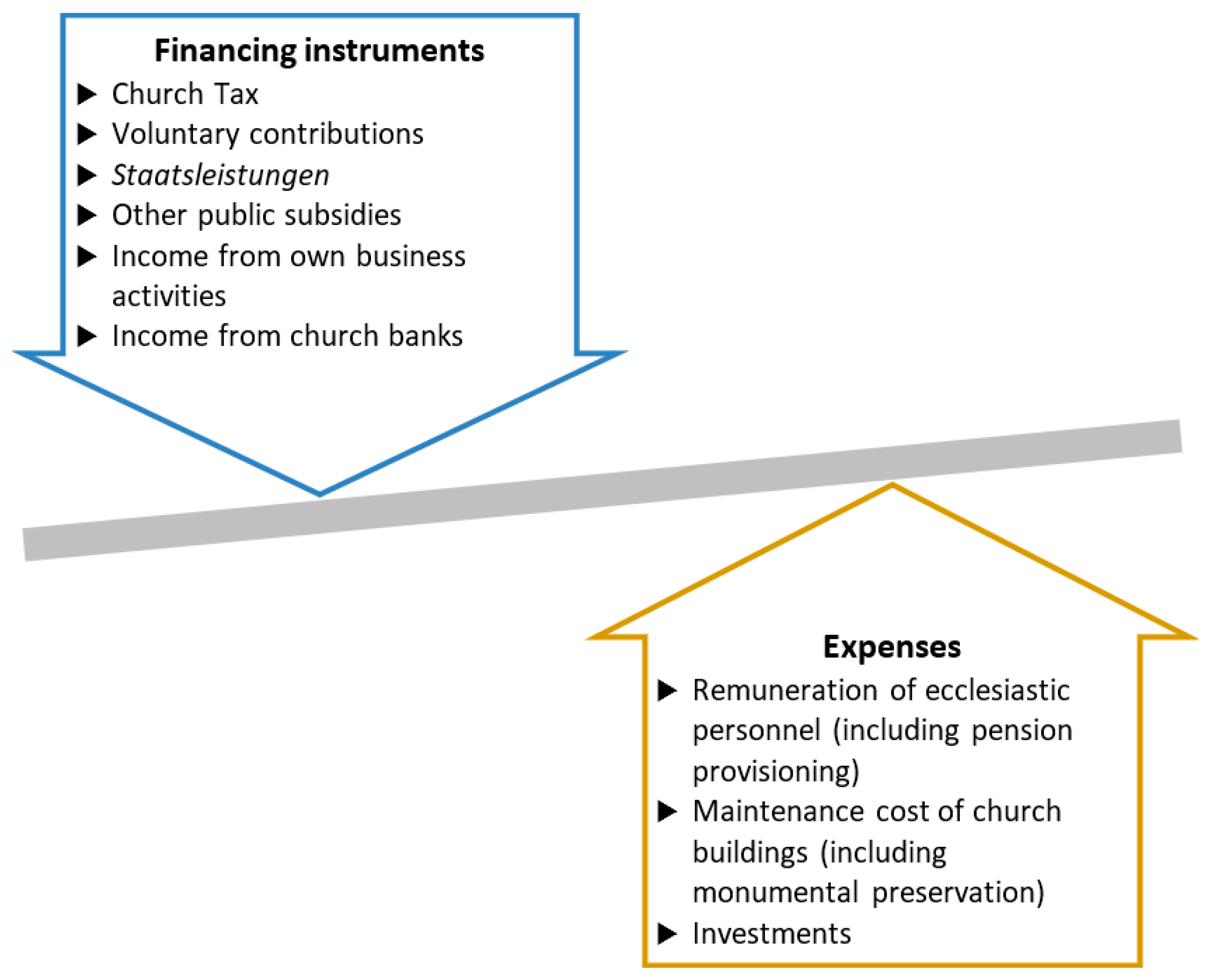

The description of the financing system of the Catholic Church in Germany will begin with the identification and characterization of its main sources of financial resources. Next, the main directions for spending the available financial resources will be discussed. The stability of the church financing system depends on the ability to ensure a constant inflow of financial resources in an amount higher than the expenses (

Figure 1).

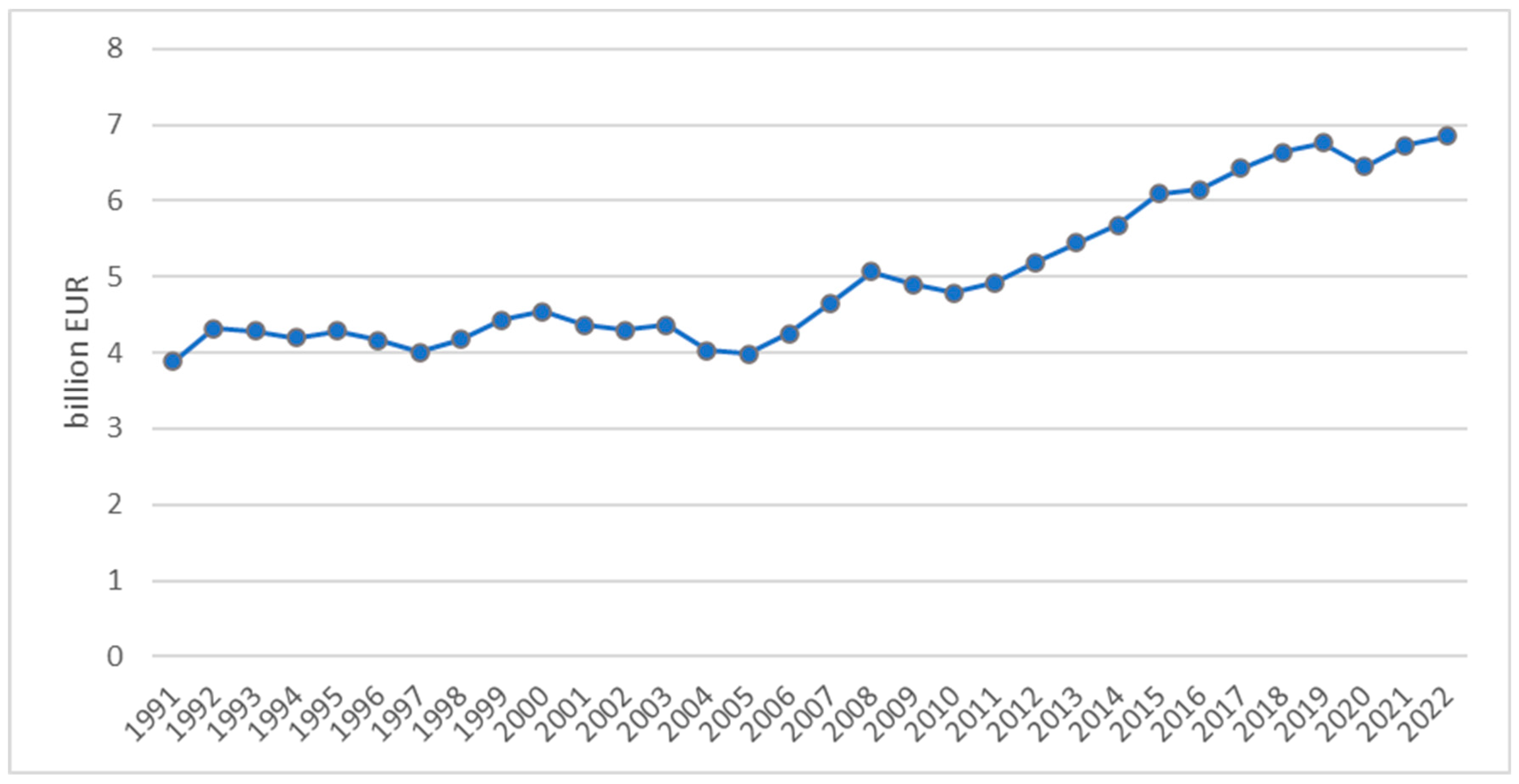

The main source of financing for the Catholic Church in Germany is the church tax. This tax is calculated from the payroll tax or income tax of members of the community. Churches inform the relevant registration offices about the commencement of church tax obligation, and they forward this information to employers (if the church tax is withheld via payroll). The church tax is also levied on capital gains. In this case, since 1 January 2015, this tax has automatically been collected by the relevant credit institutions. Each federal state has its own legislative bodies that regulate the collection of church taxes. This tax is determined in the form of a percentage rate. The tax rate varies depending on where you live; e.g., in Bavaria and Baden-Württemberg it is 8%, while all other states charge 9%. Almost all of Germany (except Bavaria) has an upper limit on the amount of church tax (the so-called kappung), which means that the tax burden cannot exceed a certain percentage of the taxable income. This ceiling varies depending on the federal state and ranges from 2.75% to 4%. This tax is collected through the tax office and is then transferred to churches. For this service, the state receives about three percent of church tax revenues. The net revenue from the Catholic church tax is presented in

Figure 2.

It should be noted that the impact of the revenue from the church tax is influenced by the demographic structure of believers and their incomes. Children and young people, elderly people with low pensions, and the unemployed do not receive salaries or pay income tax and therefore do not pay the church tax. In total, this group constitutes almost half of Catholics in Germany (

Katholische Kirche in Deutschland: Zahlen und Fakten 2022/23 2023).

Another source of financing is voluntary contributions, i.e., all kinds of resources donated to the church. The resources in question may be monetary or non-monetary, i.e., in the form of material goods or volunteering. Documented donations are tax-deductible, but only at the congregational level. This type of financing constitutes a small share in the structure of church revenues. It is also unstable and unpredictable.

The third source of financing for the Catholic Church in Germany is Staatsleistungen, i.e., benefits from the German state resulting from the expropriation of the church carried out during the Napoleonic secularization period. The proceeds are transferred to the salaries of bishops and employees of the diocesan chapter and are also used for the maintenance and renovation of church buildings (

Hartmann 2014). Although this source’s share of the church’s finances is small, due to its nature it is the subject of many political debates.

Another source of financing is state subsidies. They take the following forms (

Biermeier 2019):

Tax relief on donations made to the church.

Direct sponsorship and subsidies, i.e., earmarked funds that can only be spent for previously defined purposes. They are directed, for example, to church academies (Bildungshäuser), schools, kindergartens, community centers, sheltered workshops, and other social institutions to cover running costs related to the operation of these institutions.

Financial support in performing social welfare tasks, e.g., subsidies for drug clinics and mobile nursing services.

Financial support for the process of teaching religion and pastoral care by financing the remuneration of teachers of Catholic religious education in public schools; running theological schools and faculties at universities; and paying for pastoral care in institutions such as the army, hospitals, and prisons.

The remaining state aid is provided on a one-off basis, depending on emerging needs.

The church also obtains revenues from its property resources and its own business activities. Owned properties bring profits to the church in the form of dividends, interest payments, capital gains, and income from rents and leases. Church institutions also conduct business activities. Examples of such activities include media companies (

www.Katholisch.de), television (

www.kirche.tv), and broadcasting agencies as well as breweries (Bischofshof) and wineries (Bischöfliches Weingut Rüdesheim).

Currently, 14 banks in Germany and Austria are owned by church institutions or orders (

Biermeier 2019). These banks, called church banks (Kirchenbanken), offer their services exclusively to ecclesiastical and social welfare institutions and to church employees. The exception is clients who, although not employed by the church, have proven their commitment to the church and religion. Most church banks operate as cooperative banks (registered cooperatives), with regional churches and related institutions being members and clients at the same time. They are focused on supporting religion, the religious community, and humanity, unlike other banks, which are focused on profit maximization.

Among the church banks in Germany, five are Catholic banks owned by dioceses. Four of them, namely the Darlehnskasse Münster, the Bank für Kirche und Caritas, the Bank im Bistum Essen, and the PAX-Bank, are located in North Rhine-Westphalia, which is connected with a number of Catholics in this area. The fifth bank, the LIGA Bank, is located in Bavaria. In addition to the above-mentioned church banks, there are also two Catholic monastery banks. The first is Steyler Bank, which is managed by the Confraternity of the monks ‘Society of the Divine Word’. The second is Bank für Orden und Mission, which is run by the Franciscan Order and serves its members throughout Europe. This bank is in fact a branch of the secular bank VR Bank Untertaunus.

Church banks, by definition, are predisposed to ethical and responsible investments. Their offerings could be attractive to clients interested in sustainable investing. However, as mentioned above, their clients are limited to church institutions and their employees. This limitation is sometimes criticized because opening up to clients from outside church organizations could contribute to the dissemination of faith-related values in the financial area. Although churches have their own banks, they sometimes also use the services of secular banks, whose offerings are sometimes more favorable.

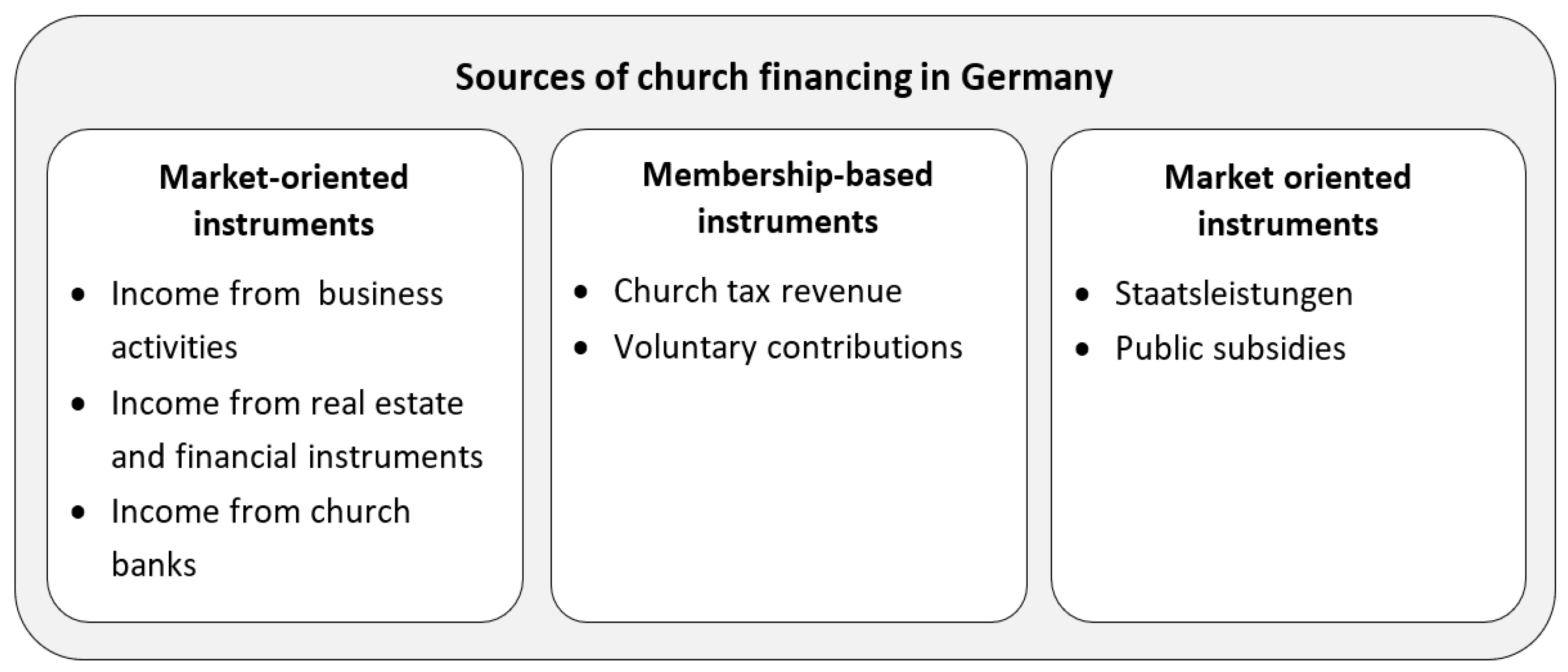

From the point of view of stability and the possibility of predicting the financial resources that will be received, it is worth dividing the sources of financial revenues into those of a market nature, those based on contributions from community members, and those coming from the state. The first group includes income from business activities, income from real estate and financial instruments, and income from church banks. The second group includes church tax revenue and voluntary contributions. The last group includes

Staatsleistungen and public subsidies (

Figure 3).

Financial resources are used to finance current expenses related to the church’s activities, including employee salaries, expenses related to pastoral service, and the maintenance of church buildings, or are used for investments. It is important that the amounts spent are adjusted based on the financial capabilities of the church, i.e., that the money is used effectively and the costs of acquired foreign capital are optimized.

The stability of the financing system requires the adjustment of expenses based on the revenues generated and a guarantee of the stability of the sources of revenues. In the context of fulfilling the church’s mission, this requirement poses a great challenge to church institutions. Expenditures are determined by the needs reported by the faithful, both in terms of church services and helping those most in need. Therefore, it is the sizes and scopes of the requirements that determine the need to obtain revenue. This is a reversal of the budgeting principle, where the revenues obtained determine the expenses. From this point of view, the following question arises: how important are economic calculations in implementing the mission and tasks of the church? It seems obvious that the ability to operate a church effectively requires knowledge and the ability to manage its financial resources. However, in the implementation of the church’s tasks, the long-term nature of the undertaken activities is important. Therefore, guaranteeing stable sources of income is necessary for the efficient functioning of the Catholic Church.

Socio-demographic changes have caused a change in the structure of revenues, i.e., tax revenues are decreasing. Undoubtedly, this is one of the most important and difficult challenges for church authorities, who, observing the changes taking place, should consider whether the implementation of tasks requires an increase in the state’s share (e.g., through subsidies) or whether the church’s economic assets should be used to a greater extent (development of economic activities).

When considering the sources of church financing, it is worth paying attention to the importance of their stability in the context of the most important mission of the church, which is to create a church community and strengthen the bond of the faithful with God. This is possible through the provision of pastoral services by clergy as well as through their presence in the lives of the faithful through conversation and praying together.

Prayer is the foundation of the religious and moral lives of believers. The importance of prayer as a way of meeting God was pointed out by St. Paul. “Therefore faith comes from what is heard, and what is heard comes from the word of Christ” (Rom 10:17).

Prayer is individual and direct communication with God based on love. In one case, it serves to consider the provisions of the Holy Scripture and deepen the understanding of the truths conveyed in it, and in another it is a way to share with God the joys, worries, hopes, and doubts that abound in our lives.

The content of prayer can be diverse. In prayer, standing in the presence of God, we discover our innermost feelings. Depending on the current needs and the mental and physical condition of the faithful, it may take the form of a prayer of supplication, thanksgiving, or an expression of appreciation and praise.

In the Holy Scriptures, you can often find references to prayer of supplication. Jesus Christ not only actively uses such prayer but also encourages it. He emphasizes the value of simple, sincere, and trusting prayer. Prayer can also be a way to express gratitude for receiving a wonderful thing and God’s mercy. This type of prayer results from recognizing the totality of all events and experiences, both favorable and unfavorable, as God’s gift.

An important part of prayer is also praising the greatness and benefaction of God. This type of prayer results from seeing God in his unlimited and infinite perfection. “Praise is that form of prayer in which man most directly acknowledges that God is God. It praises Him for His own sake, it gives Him glory not because of what He does, but because HE IS” (Catechism, 2639).

The importance of prayer can be considered not only in a religious context but also in a social context. Various sciences, i.e., the psychology of religion, psychiatry, and nursing, study the impact of prayer on human health and indicate that in a psychotherapeutic context, prayer can support the treatment of patients and deepen the bond between a psychotherapist and a person seeking help. For many people, prayer is becoming a particularly effective way of dealing with the challenges of everyday life, which is why it is so important for it to be present in the lives of believers.

4. The Most Important Challenge in the Process of Ensuring the Stability of the Catholic Church Financing System

Beyond historical precedent, the financial support of the church by the state serves as a conduit for fostering social cohesion and preserving cultural identity. Religious institutions often play a pivotal role in shaping societal values and norms (

Putnam and Campbell 2010). By providing financial assistance, the state reinforces the pivotal role of the church in shaping the moral fabric of society, thereby contributing to a sense of unity and shared cultural identity.

This support is not solely rooted in history but is a contemporary phenomenon observed in various countries worldwide. For example, in countries with a predominant religious identity, the state’s financial backing of religious institutions aligns with a broader effort to fortify the national identity and cultural cohesion (

Putnam and Campbell 2010).

The intertwining of state and church finances carries significant economic ramifications, often sparking debates about resource allocation and economic efficiency (

Gornick 2002). Critics argue that funneling public funds to religious institutions may divert resources away from essential public services, leading to potential economic inefficiencies. The argument here is that public money should be directed towards sectors that directly contribute to the well-being and development of society, such as education, healthcare, and infrastructure.

For instance,

Gornick’s (

2002) examination of the role of religion in welfare-to-work programs underscores the potential economic trade-offs. When state funds are allocated to religious institutions that provide social services, there is a risk that resources are not distributed optimally, potentially hindering the overall economic development of a society. This perspective emphasizes the need for a careful balance between supporting religious institutions and ensuring the efficient allocation of resources for broader societal needs.

On the contrary, proponents of state support for the church argue that the economic benefits arising from a stable and cohesive society, facilitated by state-supported religious institutions, far outweigh any potential drawbacks (

Iannaccone 1998). This viewpoint suggests that the stability and cohesion fostered by religious institutions contribute to an environment conducive to economic growth.

Moreover, tax exemptions granted to religious organizations often contribute to their financial stability, allowing them to engage in charitable activities that might otherwise burden state resources (

Iannaccone 1998). By encouraging charitable work, religious organizations can play a direct role in addressing social issues, such as poverty and homelessness, thus lessening the burden on the state to provide these services directly.

For example, research by

Iannaccone (

1998) delves into the economics of religion, emphasizing the positive externalities associated with religious activities. When religious institutions engage in charitable work, they often serve as an extension of the state in providing essential services to the community. This collaborative effort can lead to a more efficient allocation of resources, with religious institutions playing a complementary role in addressing social and economic challenges.

The economic implications of the intricate relationship between the state and the church are further illuminated by

Sandberg’s (

2008) exploration of church–state relations in Europe. This interdisciplinary approach delves into legal models and provides valuable insights into the economic dynamics at play in various European contexts.

Sandberg’s (

2008) work highlights the importance of legal models in shaping church–state relations. Different legal frameworks influence the degree of financial entanglement between the state and religious institutions. For instance, in countries where there is a closer legal integration of church and state, financial support may be more explicit and institutionalized. Understanding these legal nuances is crucial for comprehending the economic implications of state support for the church.

Critics, drawing on

Sandberg’s (

2008) interdisciplinary perspective, argue that the economic implications of state support for religious institutions can vary significantly based on the legal models in place. For example, in countries where the legal model mandates a strict separation of church and state, the allocation of public funds to religious institutions may face stronger opposition. This resistance is often grounded in concerns about the misuse of public resources and potential violations of the principle of secularism.

Conversely, in countries where the legal models allow for a more integrated relationship between the state and the church, proponents argue that the economic benefits are more evident.

Sandberg’s (

2008) research underscores the importance of considering legal frameworks when assessing the economic implications of state support for religious institutions. The legal context shapes the extent to which financial support is provided, and understanding this dimension is crucial for finance professionals navigating the complexities of church–state relations.

Additionally,

Sandberg’s (

2008) interdisciplinary approach prompts us to consider the broader societal and economic consequences of state support for the church. Beyond the immediate financial transactions, the stability and cohesion fostered by religious institutions underpin societal well-being and, consequently, economic development. This holistic view encourages a nuanced understanding of the economic dynamics involved, recognizing that financial support for the church is embedded in a complex interplay of legal, cultural, and economic factors.

The economic implications of state support for the church take on added depth when considering insights from Nick Haynes’ research report on church–state relationships in selected European countries, which was commissioned by the Historic Environment Advisory Council for Scotland (HEACS) in June 2008. Haynes’ research provides a nuanced understanding of how state support influences economic dynamics, particularly in the context of historic buildings and cultural heritage.

The report by

Haynes (

2008) underscores the intricate relationship between the state and religious institutions, emphasizing the historical and cultural dimensions that shape financial interactions. In many European countries, state support for the church extends beyond contemporary economic considerations; it is deeply rooted in the preservation of historical and cultural assets, including religious buildings.

One economic implication highlighted in Haynes’ research is the role of the state in funding the maintenance and restoration of historic church buildings. These structures often carry significant cultural and historical value, contributing to the identity of a nation or region. State financial support for the upkeep of these buildings not only serves a cultural purpose but also generates economic activity through heritage tourism and related industries.

Moreover, the economic implications of state support for the church, as revealed in the research report, extend to the broader historic environment. Churches and religious sites are integral components of the cultural landscape, and state support often translates into the preservation of a nation’s heritage. This preservation, in turn, contributes to the tourism sector, promoting economic growth and generating revenue for local communities.

However, Haynes’ report also highlights challenges in the economic aspects of church–state relations. Financial strains on the state, particularly during economic downturns, may lead to reduced funding for the preservation of historic religious buildings. This raises questions about the sustainability of relying on state support for the long-term maintenance of cultural heritage.

The stability of the church’s financing system requires a guarantee of the ability to generate a surplus of financial revenues over incurred expenses. This process requires analyzing the structure of revenues and expenses to determine the expected revenues from each of the individual sources.

The church tax has the largest share in the structure of financial revenues. The amount of annual revenue from this tax is determined by the demographic structure of the church members and the changes taking place therein; the general economic situation of the country, especially the pace of economic development; and the state’s fiscal policy. The church tax is levied on top of payroll tax or income tax. Therefore, it is only paid by those members of the church community who work. The aging of the population and the overrepresentation of older people mean that the amount of revenue obtained from this may decrease. The second disturbing phenomenon is secularization, i.e., people leaving the church. Over the last decade, this phenomenon has become increasingly important and, unfortunately, particularly affects younger social groups, which in practice may lead to a deeper decline in tax revenues.

Another important factor influencing the amount of revenue from the church tax is the general economic situation of the country, including the pace of economic development and changes (i.e., increases) in employment. The report Katholische Kirche in Deutschland: Zahlen und Fakten 2022/23 (2023) shows that the increase in church tax revenues in the recent period was mainly influenced by the very good level of economic development that indirectly resulted from growing employment and an increase in customs duties. At the same time, there were slight adjustments to wage and income tax rates, which contributed to an increase in the number of church-tax payers. It is in this aspect that decisions regarding fiscal policy translate into the amount of revenue from the church tax.

From the point of view of the certainty of financial revenues, public subsidies are an important source of financing. Predictability as to the amount and timing of receipt of funds allows the church to fulfil socially important functions, such as education, healthcare, and charitable activities. Moreover, the funds received can be allocated more effectively.

It is also worth looking at the issue of financial stability from the point of view of expenses and adapting them to the needs and capabilities of church units in a given period. The available financial resources should be used effectively, and the cost of obtaining external financing should be optimized. The forecast of a probable decline in the number of church-tax payers and the resulting decrease in tax revenues should make church authorities think about future investments and, for example, develop the church’s economic activities.