Abstract

Bagan, the imperial capital of the Burmese Empire (11th–14th centuries CE), was situated in what is now known as Myanmar’s “dry zone”, Southeast Asia’s most arid region. This setting necessitated the development of a subtle, yet extensive rain-fed water management system that channeled water from the Tuyin mountain range in the southeast to the walled and moated royal city in the northwest. Nat Yekan tank, a rock-cut reservoir located on the western edge of the summit of the Thetso–Taung portion of the Tuyin range, played significant utilitarian and spiritual roles in collecting, sacralizing, and then channeling waters down into the vast Mya Kan reservoir, which, in turn, fed the water management system that redistributed this valuable resource across the Bagan plain. The iconographic elements carved into the stone walls of the Nat Yekan tank attest to its spiritual importance and tie it to an ideological program of kingly legitimacy grounded in guarantees of fertility and prosperity for all.

1. Introduction

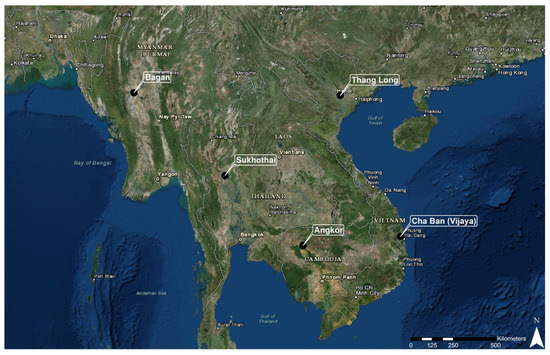

Today, the remains of 4000 monuments, including temples, monasteries, and reservoirs, mark the location of Bagan, the imperial capital of the Burmese Empire from the 11th to the 14th century CE (Figure 1). Straddling the east bank of the Ayeyarwady River, Bagan is situated in Myanmar’s dry zone, the most arid region in Southeast Asia (Figure 2). Water management was, and continues to be, a major concern for anyone living in the area, although the citizens of the old imperial capital may have benefitted from the climate amelioration known as the Medieval Climate anomaly (900–1300 CE; Lieberman and Buckley 2012). Be that as it may, like its contemporaries in South and Southeast Asia (e.g., Anuradhapura, Sri Lanka, and Angkor, Cambodia), Bagan still had to develop a means to collect, store, and distribute water to service its agricultural sector and satisfy the needs of its resident population. Donation records from across the old capital indicate that Bagan’s kings were particularly active with respect to the construction of reservoirs, dams, and canals, with 78% of such features being built between 1030 and 1200 CE (Macrae et al. 2022). Indeed, it is quite clear that kingly participation in the creation of Bagan’s water management system was a quintessential ideological endeavor with religious (the building of Buddhist merit and presentation of oneself as the spiritual guarantor of societal prosperity and fertility), political (demonstration of the legitimacy to rule through one’s generosity and organizational skills), and economic (contributions to agricultural productivity and the health of the citizenry) implications for aspiring leaders.

Figure 1.

View across the Bagan cityscape.

Figure 2.

Map of mainland Southeast Asia showing the location of Bagan, along with some of the other key polity capitals of the time.

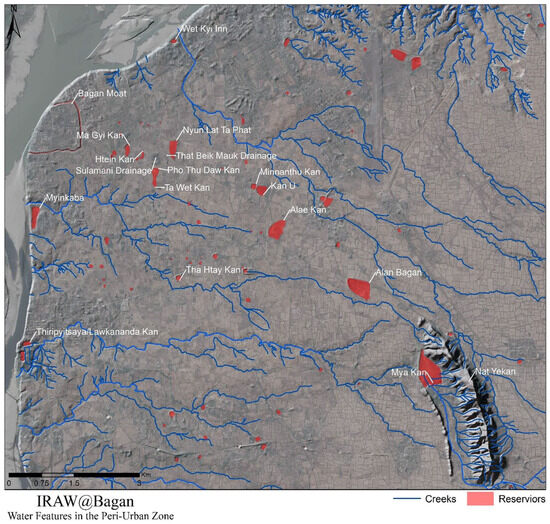

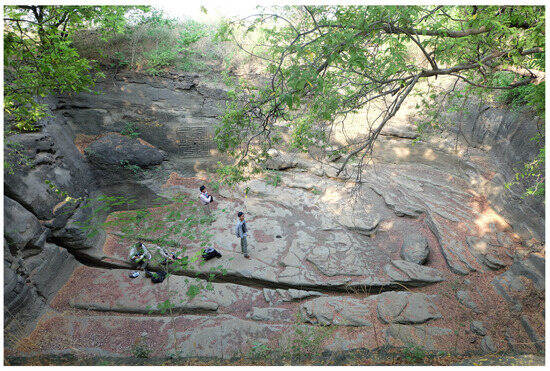

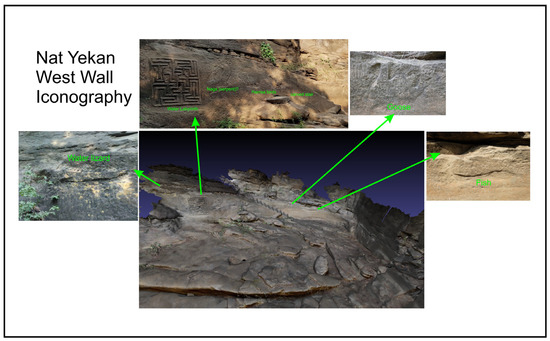

Although more subtle than its counterparts found at places like Angkor, Bagan’s water management system was still effective at collecting and redistributing water from the monsoon rains. Reconstruction of the system indicates that it began in the southeastern sector of the city’s peri-urban zone, where a series of water tanks and diversion canals on top of the Tuyin mountain range served to channel water into the Mya Kan reservoir—located at the foot of the northwestern part of the range (Figure 3)—after which time it flowed through a series of canals and reservoirs in a northwesterly direction until it ultimately entered the moat surrounding Bagan’s royal city enclosure (Macrae et al. 2022; Moore et al. 2016; Win Kyaing 2018). Integral to this system was a large rock-cut tank with three stairways and a series of auspicious base-reliefs carved into its walls (Figure 4 and Figure 5). Located on the western edge of the Thetso–Taung portion of the Tuyin range, the Nat Yekan tank first collected runoff from the surrounding uplands, and when filled, diverted the overflow into what is now a seasonally dry water fall that once fed the Mya Kan reservoir (Iannone et al. 2019; Macrae et al. 2022).

Figure 3.

Main components of Bagan’s water management system, with the walled and moated royal city zone to the northwest, and the Mya Kan reservoir and the Nat Yekan tank to the southeast (map by Scott Macrae).

Figure 4.

Interior of the Nat Yekan tank, looking west; note the hole for a pillar in the center.

Figure 5.

3D scan of the tank interior showing the three major stairways and a minor, “symbolic” stair.

There is no specific inscription that refers to the construction and/or usage of Nat Yekan tank, although the Pawdawhmu Pagoda Inscription discusses the “digging” of a tank on Thetso–Taung in 1082 CE (Aung–Thwin, personal communication, 10 October 2018). The epigraphic record also confirms that the “Pagan Hills” (Tuyin Range) were already established as one of Bagan’s most sacred places as early as the 11th century CE, and a chronicle-based date for the construction of Nat Yekan has been provided, given its likely role as a quarry for the sandstone blocks that were used to construct the Shwezigon Pagoda in 1086 CE (Iannone et al. 2019, pp. 10–12). Shortly after the quarrying project, Nat Yekan was likely converted into a water tank with a spillway that channeled water to the Mya Kan reservoir. This conversion likely occurred sometime before 1098 CE, under the direction and financial support of King Kyansittha (1084–1112/13 CE)—the builder of both the Shwezigon Pagoda (1086 CE) and the Mya Kan reservoir (before 1098 CE; Iannone et al. 2019, pp. 13–27). The posited relationship between Nat Yekan and the Mya Kan reservoir is captured in an entry in the retrospective Glass Palace Chronicle, where it is stated that King Kyansittha:

“dammed the water falling from the foot of Mt. Tuywin [Tuyin] and made a great lake. He filled it with the five kinds of lotus and caused all manner of birds, duck, sheldrake, crane, waterfowl, and ruddy goose to take their joy and pastime therein. Near the lake he laid out many tā of cultivated fields; it is said he ate [produced] three crops a year. Hard by the lake he built a pleasant royal lodge, and took delight in study seven times a day”.(Luce 1969, p. 345; Pe Muang Tin and Luce 1923, p. 156; emphasis ours)

Beyond its mundane role in collecting and distributing water, Nat Yekan’s iconographic inventory implies that it held a significant role in spiritually purifying and sacralizing water prior to sending it down to the agricultural fields, citizens, and eventually, the royal city itself. For this reason, the tank was also a key element in the ideology of kingship at Bagan. The following analysis of the tank’s iconography expands on this assertion, with an overt emphasis on the physical and historical contexts of the images and their potential “functional” intent (e.g., Faure 1998).

2. The Iconography of the Nat Yekan Tank

The iconography carved into Nat Yekan’s sandstone walls provides insight into the water tank’s possible ideological and ritual significance. In total, 15 individual bas-reliefs adorn the inside of the tank (Tut 2013; Lynn 2017; Win Kyaing 2018, p. 283). These symbols are organized within three informal horizontal “registers” (high, medium, and low), spanning the west, south, and north sides of the tank interior, with the eastern wall being made of sandstones bricks. This iconographic corpus has the following general characteristics: (1) all images are related to water; (2) many of the symbols are associated with each other within the traditional South and Southeast Asian Buddhist canon; (3) these iconographic elements are part of classical Bagan’s artistic corpus, and most appear—in one form or another—in the city’s painted murals, bas-reliefs, stucco façades, decorative plaques, and statuary; (4) the depictions, as indicated above, loosely fall into three elevational “registers” (high, medium, and low), and their different heights may have some symbolic significance (i.e., they are entities that live below, on top of, or above the water); and (5) the various entities seem to reference various narratives within the body of Buddhist literature, such as the Jātaka stories documenting Gotama Buddha’s 550 previous incarnations and the events associated with his last life. These Jātaka stories have long been known to dominate the iconography associated with Bagan’s temples (Luce 1956; Bautze-Picron 2003, p. 2).

Regardless of the aforementioned patterning, it remains difficult to pull the various symbols in the Nat Yekan tank into a single narrative that makes sense, as one is able to do with the terracotta plaques adorning the outsides of some of the temples at Bagan or the mural registers decorating the interiors of many of the temples. Indeed, it may be that there is no narrative to uncover at Nat Yekan. Nevertheless, by assessing the possible significance of each of the symbols depicted on the tank’s walls, one can get a sense of the broader themes that may underlay the iconography, and in doing so, reach some level of understanding concerning the possible meanings inherent within the Nat Yekan tank as a whole. In other words, it may be a case of the whole being greater than the sum of its parts. From this perspective, it is significant that the range of symbols can be classified as “auspicious” icons, not only because they connote water, but also notions of creativity, purity, fertility, good weather (productive rains), productivity, abundance, and prosperity. It was likely these meanings that helped framed perceptions of the Tuyin–Thetso range (i.e., Pagan Hills), the Nat Yekan Tank, and the broader water management system of which it was part.

3. The Three Walls

3.1. The Western Wall

The western side of the Nat Yekan tank has a single stair carved into its wall that leads from the top of the tank to its bottom. To the left of the stair, four bas-reliefs have been carved into the wall (Figure 6): a water lizard/dragon, labyrinth, nāga-serpent, and two haṃsa birds (geese). To the right of the stairs, two additional bas-reliefs exist, a goose and a fish. With the exception of the lizard, all of these symbols are located in what can be deemed the “medium register”, which may relate to creatures or objects associated—in symbolic terms—with the surface of the water. All of the animal symbols on the west wall are facing south, the direction from which much of the water would have entered the tank.

Figure 6.

Nat Yekan’s western wall and its bas-reliefs.

3.1.1. Water Lizard/Dragon

The southwestern corner of the Nat Yekan tank exhibits a poorly preserved bas-relief that appears to depict a spiny lizard, likely a Chinese (Eastern/Asian) Water Dragon (Physignathus cocincinus). This species lives in trees above water sources, and fitting with this preference, the bas-relief is situated in the highest “register”, nearest the top of the tank. Such lizards figure prominently in three Jātaka stories from Gotama Buddha’s previous lives. In Godha–Jātaka (#138), we are told that the Bodhisattva (Buddha from a previous life) was living as a lizard. We are also informed that lizards emerged during an “unexpected storm in the dry season” (Cowell 1895a, p. 297). The Daddara–Jātaka (#304) tells of two nāga-serpent brothers being expelled from the Nāga World for three years because one of them was abusing the nāga maidens, the other brother being the Bodhisattva who tried to intervene. At one point in the story, these brothers are referred to as “water lizards with big heads and tails like needles” (Cowell 1897, p. 12). Finally, we are told that the Bodhisattva was again born as a lizard who lived in the forest in the Godha–Jātaka (#325; Cowell 1897, pp. 56–58).

These three Jātakas confirm that the lizard can be used as a symbol for Gotama Buddha—or more specifically, for some of his previous iterations as a Bodhisattva—in addition to being indicative of the watery Nāga World and even auspicious storms that unexpectedly occur during the dry season.

3.1.2. Water Labyrinth

To the right (north) of the Water Dragon and down from it—in the medium elevation register—is a base relief depicting a labyrinth, undoubtedly the most famous symbol at Nat Yekan. We specifically use the term “labyrinth” as opposed to “maze” when discussing this image. This is because, although they are often utilized in a similar manner, the two terms are usefully employed to refer to different patterns (Kern 2000, p. 25). According to Kern (2000), a path containing twists and turns but leading more or less directly into and out of a central point is best referred to as a labyrinth. In contrast, a path that not only has many twists and turns but also bifurcations and dead ends should be referred to as a maze. The labyrinth is meant to prolong what is essentially a guided journey towards a goal, whereas a maze serves to confuse and confound, thereby protecting the goal. Indeed, mazes have long been connected to the idea of defense and security in Europe and South Asia (Brooke 1953), and they may also manifest as city walls in some contexts (Brooke 1953, p. 470). The latter idea may be a fitting interpretation for the extensive earthen ramparts at some of the moated centers in Southeast Asia dating back to the latter half of the 1st Millennium BCE, in particular Co Loa, located in northern Vietnam (Kim 2013, pp. 248–49).

In contrast, labyrinths tend to have mythological connotations. In India and Europe, for example, the symbol has long been considered sacred and connected to the sun, and it is therefore associated with beliefs relating to solar worship (Brooke 1953, p. 468). Indeed, an association has been found between labyrinths, temples, and palaces dedicated to sun worship, as in the Pāṇḍava legends of the five sons of the King Hastinapur of the Kuru Kingdom in Northern India (Brooke 1953, p. 471). That said, when it comes to the actual meaning of a specific labyrinth symbol in a particular context, Brooke 1953, p. 471 is forced to conclude that, in reality: “All that we can say is that the labyrinth became the nucleus of various mythologies, which in their turn supported and preserved the memory of this symbol in various parts of the World”. This means that each representation of this symbol must be fully contextualized in order to ascertain what it may be signifying in the particular setting under investigation.

Returning to classical Bagan and Nat Yekan tank, the image on the west wall is clearly a labyrinth and not a maze, as one can easily trace a single path from outside-in or inside-out, with no confusion along the way. In other words, the path leads you into and out of the center of the image. The pattern near the center forms a right-facing swastika, an auspicious icon meant to invoke happiness, prosperity, and protection (Karlsson 2006, p. 81). This suggests that the symbol has mythological significance.

Our ability to ascertain the meaning behind the labyrinth symbol in Nat Yekan is enhanced by the existence of two murals with strikingly similar images at Bagan, one from the early 12th century Lokahteikpan Pagoda (1125 CE), and the other from the early 13th century (1223 CE) Le-myet-hna Pagoda (Figure 7). These murals both appear to depict a water tank, given that Bagan-style water symbols are found inside the labyrinth symbols. The water tank interpretation is lent credence by the fact that the labyrinths are surrounded by shrubs and trees. Additional information can be derived from the pictorial contexts of these symbols, which are murals depicting episodes from the Jātakas, stories of Gotama Buddha’s previous lives as a Bodhisattva (one seeking to be awakened). Considering this context, it appears that the labyrinth symbols are depicting an artificial lake discussed in the Mahosadha–Jātaka (#564; Duroiselle 1921, p. 56; Luce 1956, p. 294, 301). In this Jātaka, we are told that the young Mahosadha—the Bodhisattva of the time—commissioned a water tank “with a thousand bends in the bank and a hundred bathing places. The water was covered with the five kinds of lotuses and was as beautiful as the lake in the heavenly garden Nandana”, which was the Garden of Paradise (Cowell 1907, p. 159). At Bagan, the Jātaka plaque at the Ānanda temple references the Mahosadha Jātaka and the “tank with a thousand bends and one hundred bathing places [employs a] zigzag figure” that may be a stylized labyrinth (see Duroiselle 1921, p. 56, Plate 125).

Figure 7.

Labyrinth in a mural from Le-myet-hna (#447) pagoda, representing the water tank with many bends and bathing places from the Mahosada–Jātaka #546.

The “labyrinth-as-water-tank” interpretation receives additional support from the fact that there is a conical hole near the center of Nat Yekan’s labyrinth symbol. If we consider this image, along with those found in the murals and Jātaka plaques, as plan views of water tanks, it is possible that this hole once held a scaled-down version of a lotus pillar, a feature still found in reservoirs in traditional villages and some of the temple complexes at Bagan to this day (Figure 8). Although such pillars, including the one suggested to have extended out of the Nat Yekan labyrinth, may have served the mundane purpose of measuring water levels, they also have symbolic connotations, as will be discussed later in this treatise. Considered in unison, the labyrinth symbol on Nat Yekan’s wall appears to be an auspicious icon depicting a sacred water tank, one that is likely linked to the idea of prosperity.

Figure 8.

Lotus pillars in the water tanks at the Dhamma-yazika temple (left), and Minnanthu Village (right).

3.1.3. Nāga-Serpent

To the immediate right of the Labyrinth symbol and still in the medium register (symbolic of the water surface), is what appears to be a nāga-serpent image. Nāgas are mythological serpents consistently associated with water and the underworld in South and Southeast Asia (Karlsson 1996, pp. 196, 208). In Myanmar Buddhist thought, water-dwelling nāga serpents—who sometimes take on human form—serve as protectors of both the Buddha and cosmic law and order, or dhamma (Thidar 2016; see also Andaya 2016, p. 245; Bloss 1973, p. 49, 1978, p. 169). Buddhist cults focusing on nāga worship—including the Ari School—developed in Myanmar during the Pyu and Bagan periods (Béguin 2009, p. 193). In these early cultural traditions—and those that developed from them—nāgas are generally considered benevolent beings (Thidar 2016). That said, on the regional scale—encompassing South and Southeast Asia—these water-dwelling, underworld beings also have malevolent aspects (Béguin 2009, p. 49).

Given their perceived importance in the Buddhist world, it is not surprising that nāga imagery is so common in the related artistic and literary traditions. Beyond the myriad sculptural and mural depictions, literary sources tell us that the Gotama Buddha was bathed by two nāgas shortly after his birth (Karlsson 1996, p. 197). There is also a story about a nāga living as an ordained monk for some time before he was found out and subsequently expelled by Gotama (Karlsson 1996, p. 197). In the previously discussed Daddara–Jātaka (#304), two Nāga-serpent brothers—referred to as water lizards—were expelled from the Nāga World for three years because one of them was abusing the Nāga maidens—the other being the Bodhisattva who tried to intervene (Cowell 1897, p. 12). Elsewhere, in the Campeyya–Jātaka (#506), the Bodhisattva lived under the water in a jeweled pavilion as the Serpent King, Campeyya (Cowell 1901, pp. 281–90). Finally, one of the most commonly depicted moments in Gotama Buddha’s life is when he was protected by the Nāga King (Mucalinda) while meditating, during the 6th week following his enlightenment. The significance of this episode will be discussed in greater detail below, in relation to the Nāga–Buddha or Mucalinda–Buddha image located in the northwest corner of Nat Yekan tank.

In terms of symbolism, nāgas are closely connected to other water-related symbols, such as lotus stalks (Wolters 1999, p. 85). As creatures of the water (Cowell 1895a, p. 77), nāgas gain both their significance and popularity in Buddhist iconography precisely because of where they reside (Ward 1952, p. 144). They are believed to have power over rainfall and fertility, and thus agricultural productivity and prosperity (Bloss 1973, p. 172; 1978, p. 169; Karlsson 1996, p. 197; Wolters 1999, p. 80). Given these powers, it is not surprising that nāgas are closely tied to the institution of kingship and notions of wealth and power (Karlsson 1996, pp. 196, 208). For example, inscriptional evidence from the classical Khmer of Cambodia connects the institution of kingship to the “glory” that resulted from constructing large water tanks, in addition to emphasizing the ties that exist between water tanks and the underworld, the home of the aquatic nāga-serpents who are closely associated with fertile soils, and hence productivity and prosperity (Wolters 1999, p. 80). Amongst the Khmer, this fertility and resulting productivity were believed to be a direct result of the “beneficent” union of a king and a serpent princess (nagi) who lived beneath the soil (Karlsson 1996, p. 196; Wolters 1999, p. 85).

In summary, the Nat Yekan nāga image likely gains its significance because of this being’s association with water, fertility, productivity, and prosperity, characteristics that are fitting for a water tank believed to be so crucial to Bagan’s broader water management system, and its kingship governance structure (e.g., DeCaroli 2019).

3.1.4. Geese or Haṃsa Birds

Associated with the labyrinth and nāga icons on Nat Yekan’s west wall are two geese or haṃsa birds, with the left image being less well-preserved but still clearly distinguishable as to form. Referred to as a hintha or hangsa in Burmese (Moore and Maung (Tampawaddy) 2018, p. 142), such birds have been identified as Ruddy Shelducks/Brahminy Ducks (Tadorna ferruginea), geese that migrate from the Himalayas through India and into Myanmar (Stadtner 2011, p. 134). These birds prefer rivers, lakes, and reservoirs and normally have one mate for life (Seekins 2017, p. 248). Various Jātaka stories document past lives of the Buddha when he was born as a goose that lived on a lake or pool, including the Uluka–Jātaka (#270; Cowell 1895b, pp. 242–43), Cakkavaka–Jātaka (#434; Cowell 1897, pp. 310–11), Palasa–Jātaka (#370; Cowell 1897, pp. 137–38), Neru–Jātaka (#379; Cowell 1897, pp. 159–60), Cakkavāka–Jātaka (#451; Cowell 1901, pp. 44–46), Java Na-Haṃsa–Jātaka (#476; Cowell 1901, pp. 132–36), and Haṃsa–Jātaka (#502; Cowell 1901, pp. 264–67).

In Myanmar, depictions of haṃsa birds are often associated with the sacred geese that were used as the symbol of the kingdom of Pegu. These birds also represent the founding legend of this kingdom (Galloway 2006, p. 173), the formal name for which was Haṃsavati (Aung-Thwin and Aung-Thwin 2012, p. 133). In Hindu mythology, haṃsa birds also serve as the vehicle of Brahmā (Aung-Thwin and Aung-Thwin 2012, p. 134), who has traditionally been depicted as a deity that holds instruments of sacrificial nature, including a scepter, a lotus flower, a string of beads, and the ancient Sanskrit texts known as Vedas (Lwin 2017, p. 3). The haṃsa, when mounted by Brahma, is a symbol that represents creative power (Pathak 2010, pp. 3–4). Importantly, the importance of the haṃsa bird in Hindu beliefs is not only related to the fact that it serves as the vehicle of Brahmā but also because “it is a symbol of sovereign freedom through stainless spirituality” and an iconic element strongly tied to water cosmology (Ward 1952, p. 145). This broad significance, relating to water cosmology and creative powers, may explain why the haṃsa birds were depicted in the Nat Yekan tank within a Buddhist religious context.

3.1.5. Goose (Swan)

A third goose, or possibly a long-necked swan, appears to the right of the western stairs. This moderately well-preserved image differs in form compared to the two previously discussed haṃsa bird depictions and thus likely represents a different species of bird. If the bird is a swan, rather than a goose, it may relate to Suvannahaṃsa–Jātaka (#136; Cowell 1895b, pp. 292–94). In this story, the Buddha lived as a goose or swan—referred to in the story as a golden mallard—whose feathers helped support his human family until they became too greedy. Is this the story and lesson invoked by the third bird image on Nat Yekan’s west wall? One cannot be sure because it is impossible to determine with certainty which bird species is being depicted. For this reason, we cautiously group this symbol with the aforementioned haṃsa bird icons, keeping in mind that haṃsa bird imagery varies considerably. In doing so, we presume similar intentionality and symbolism relating to water cosmology and the powers of creation.

3.1.6. Fish

A large fish is located to the right of the previously discussed bird image. Once again, this icon is moderately well-preserved. Although clearly a fish, the species cannot be discerned from the generic profile rendered on the wall. That said, all fish are water species, so the connection to ponds, lakes, rivers, and oceans is obvious. Beyond that, we can learn something about how fish were viewed in Buddhist thought in the Bagan era from their appearance in the Jātaka tales. Various stories tell us that in his past lives, the Buddha often lived as a fish, as in the Maccha–Jātaka (#75; Cowell 1895a, pp. 183–84) and Baka–Jātaka (#236; Cowell 1895b, pp. 161–62). In the latter story, the Buddha lived as a fish that was hunted by a crane. Alternatively, the Buddha’s previous lives sometimes connected him to fish—although he himself was not a fish—as in the Uluka–Jātaka (#270), wherein Ānanda was the king of the fish and the Bodhisattva lived as a golden Goose, the king of the birds (Cowell 1895b, pp. 242–43). This may tie the fish image to the previously discussed “goose” image on the western wall. Alternatively, the Cakkavaka–Jātaka (#434) discusses a lotus-tank inhabited by fish, tortoises, and two golden Geese—one male and one female—the Bodhisattva being the male goose (Cowell 1897, pp. 310–11).

Noteworthy is the fact that fish and tortoises are often associated with each other in the Jātakas, including in the Vikannaka–Jātaka (#233; Cowell 1895b, pp. 157–58), Mahā-Panāda-Jātaka (#264; Cowell 1895b, p. 230), Mahā–Ukkusa-Jātaka (#486; Cowell 1901, p. 184), Mahā-Mora–Jātaka (#491; Cowell 1901, p. 212), Dasa–Brāhmaṇa-Jātaka (#495; Cowell 1901, p. 230), and Bhallātiya–Jātaka(#504; Cowell 1901, p. 272). In some Jātakas, we are told that fish and tortoises bury themselves in the mud during droughts—as in the Maccha–Jātaka (#75; Cowell 1895a, pp. 183–84) and the Kacchapa–Jātaka (#178; Cowell 1895b, p. 55)—and they are also said to instinctively know when it will rain, as documented in the Kacchapa–Jātaka (#178; Cowell 1895b, p. 55). Intriguingly, we are also told that fish—including fish identified as the actual Bodhisattva—have the ability to make it rain. For example, in the Maccha–Jātaka (#75), the Buddha lived as the King of Fish, and because he had the ability to make it rain, he brought an end to the drought (Cowell 1895a, pp. 183–85).

In broader terms, fish are often associated with fertility and a long life within Southeast Asia. Within this region, the depiction of fish has been associated with Matsya, a reincarnation of Visnu (San 2014, p. 70). According to the story, Visnu appeared in the form of a large fish in order to rescue Manu, an individual chosen for his piety, from a flood. Manu was chosen as the progenitor of the new race of humans that would repopulate the world (San 2014, p. 78). The significance of fish in this context can be associated with concepts of fertility because it represents the beginning of life (San 2014, pp. 70, 77). In this context, the contrasting properties of water can also be identified. The fish is associated with the life-giving capabilities of water. However, through flooding, water is also linked to the destruction of life.

It is interesting to note that the connection between fish and fertility, rather than being limited to the idea of an abundance of fish, has also been associated with fertility in the form of abundant crops and childbearing capacities (Van Der Kroef 1954, p. 848; Wessing 2006, p. 221). In Indonesia, farmers seeking to increase the productivity of their fields eat fish when they are about to sow their land. Powers of fertility are thus gained by consuming fish. Such powers are also believed to be transferable to barren women through a cloth worn by a person who has consumed fish (Van Der Kroef 1954, p. 848). Ethnoarchaeology conducted in villages near the archaeological site of Bagan by our IRAW@Bagan project indicated that fried fish was consistently brought to the field as an offering to the spirits in order to increase the productivity of the land. Similarly, fried fish is brought to and consumed in front of nat shrines by couples who have recently gotten married. It is likely that the couples believe that eating fish in front of the shrine increases their fertility and chances of conceiving.

In summary, the depiction of fish in the Nat Yekan water tank, rather than simply indicating the desire for an abundance of fish and water, may have been an attempt to increase the fertility capacities of the water within the tank. It was believed that this capacity could subsequently be transported from the tank to the agricultural fields on the plain below. There is also a strong connection between fish symbolism and the ability to predict or even initiate rainfall, which may be conflated with the ability of a water tank to provide water even during the dry season.

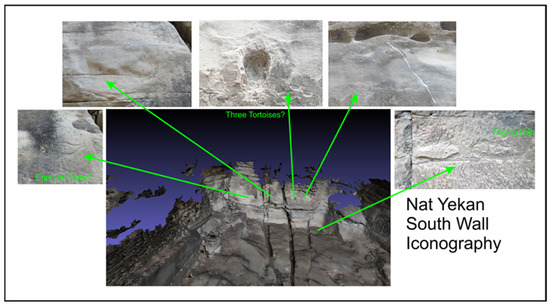

3.2. The Southern Wall

The southeast and southwest corners of Nat Yekan are where water entered the reservoir. There is no stairway on the southern side of the tank. There are, however, numerous symbols carved into the wall (Figure 9). The majority of these are found in the medium register—including an egret or crane, and three tortoises—with the remaining icon comprising two facing fish situated in the lowest register (possibly symbolic of being below the water surface). All the bas-reliefs are poorly preserved compared to those on the western wall, due to water running across the face of the south wall on a regular basis. The possible iconographic significance of these symbols is discussed below.

Figure 9.

Nat Yekan’s southern wall and its bas-reliefs.

3.2.1. Egret or Crane

A very lightly incised water bird with long legs, facing east—likely an egret or crane—is situated below the southeastern corner of Nat Yekan tank. This symbol is moderately well-preserved and positioned in the medium register, symbolically associated with the water surface. Beyond the obvious relationship to watery environments, it is noteworthy that in Buddhist literature, “cranes are conceived at the sound of thunder” (Cowell 1895b, p. 249; 1897, p. 149). This belief connects such birds to the type of good weather associated with rainfall. Although comparatively rare, long-legged water birds are also discussed in the corpus of Jātaka stories. For example, in the Baka–Jātaka (#236), the Buddha lived as a fish that was hunted by a crane (Cowell 1895b, pp. 161–62). The Asanka–Jātaka (#380) also discusses a crane that lived near a lotus-pool (Cowell 1897, pp. 161–64). Nevertheless, this symbol is clearly not as auspicious as many of the others depicted on Nat Yekan’s walls, given the paucity of references to such birds in the texts consulted for this study.

3.2.2. Tortoises

Three highly weathered images are situated in the center of the south wall, in the medium register. Given their positioning, they appear to be related to each other as part of a single iconographic montage. Although poor preservation inhibits our ability to identify these symbols with absolute certainty, they seem to represent three tortoises in various swimming poses. On a basic level, tortoises certainly adhere to the watery focus of Nat Yekan’s iconography. For example, in the Maha–Ukkusa-Jātaka (#486), a tortoise is said to have lived on an island in the middle of a lake (Cowell 1901, pp. 183–87). In the Jātaka stories, tortoises are also regularly associated with some of the other water-related creatures carved on the tank’s walls, including geese or haṃsa birds, as seen in the Kacchapa–Jātaka (#215; Cowell 1895b, pp. 123–24) and Cakkavaka–Jātaka (#434; Cowell 1897, pp. 310–11); and fish, as documented in the Maccha–Jātaka (#75; Cowell 1895a, p. 183), Kacchapa–Jātaka (#178; Cowell 1895b, pp. 55–56), Gaṅgeyya–Jātaka (#205; Cowell 1895b, pp. 104–5), Vikannaka–Jātaka (#233, Cowell 1895b, pp. 157–58), Maha–Panada-Jātaka (#264, Cowell 1895b, p. 230), Cakkavaka–Jātaka (#434, Cowell 1897, pp. 310–11), Maha-Ukkusa–Jātaka (#486, Cowell 1901, p. 184), Maha-Mora–Jātaka (#491, Cowell 1901, p. 212), Dasa-Brahmana–Jātaka (#495, Cowell 1901, p. 230), and Bhallatiya–Jātaka (#504, Cowell 1901, p. 272).

Most relevant to understanding the rationale behind carving tortoise images on Nat Yekan’s walls may be the Maccha–Jātaka (#75), in which we are told that fish and tortoises bury themselves in the mud during droughts (Cowell 1895a, p. 183), and the Kacchapa–Jātaka (#178), wherein tortoises and fish are said to know instinctually when the season will be rainy and when there will be drought (Cowell 1895b, pp. 55–56). In the latter story, we are again informed that if there is a drought, a tortoise will search for water, but if none can be found, they will bury themselves in the mud. These Jātakas underscore that tortoises are sensitive to changing weather conditions, especially rainfall and drought. For this reason, the depictions of them swimming on Nat Yekan’s south wall may be viewed, in symbolic terms, as an effort to underscore the tank’s importance as a reservoir that was not only meant to collect water during the rainy season but also store it for at least part of the dry season.

3.2.3. Facing Fish

The last set of images on the south wall is located close to the southwest corner, in the lower register suggested to be situated below the symbolic water surface. This bas-relief depicts two facing fish which, based on their proximity, size, and orientation, are meant to be considered in unison. The significance of singular fish has already been discussed in terms of the icon carved into the west wall. For this reason, and due to the fact that the two fish on the south wall are meant to be contemplated as part of the same symbol, we only review epigraphic and thematic evidence relating to paired fish imagery. In the Mitacinti–Jātaka (#114), two lazy fish are saved by a third fish (Cowell 1895a, pp. 256–57). Elsewhere, in the Gangeyya–Jātaka (#205), we are told that two fish meet and compare their beauty, after which they ask a tortoise to judge who is more beautiful; the tortoise ultimately concludes that he is the most beautiful (Cowell 1895b, pp. 104–5). Neither of these stories tells us much about the possibly symbolic meaning behind the paired fish carving at Nat Yekan, beyond the fact that fish are water dwellers. However, if we shift our attention to the broader study of Buddhist iconography, we learn that pairs of golden fish—often depicted facing each other—are believed to symbolize fertility, abundance, and prosperity (Beer 2003, p. 5). This theme, we argue, fits nicely with the broader symbolic intent of Nat Yekan’s iconographic inventory.

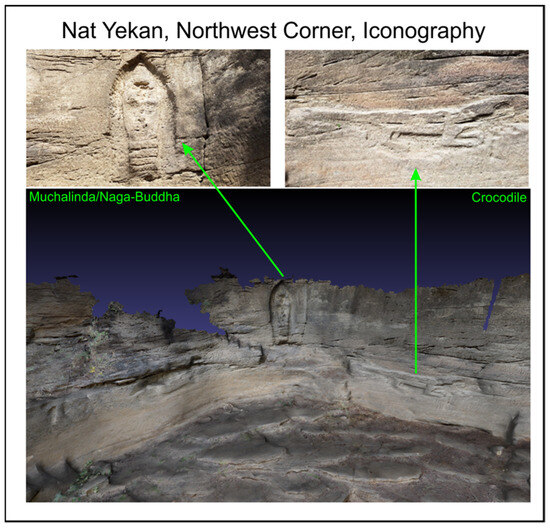

3.3. The Northern Wall

Nat Yekan’s northern wall has stairways in both its northeast and northwest corner, with the latter leading down to a crude altar situated at the base of a Mucalinda–Buddha image (Figure 10). To the right and below the Mucalinda–Buddha—but still in the medium register that symbolically represents the surface of the water—is a crocodile or makara image. Both bas-reliefs are moderately well preserved, although some of the details of the Mucalinda–Buddha relief are quite eroded and thus hard to discern. The significance of the latter image relates not only to its content but also to the fact that it is situated just below and in axial alignment with the Nat Yekan spillway area, meaning water would have had to flow over the image on its way out of the tank and downslope towards the Mya Kan reservoir, and subsequently, the agricultural fields, water management features, religious buildings, royal compounds, suburban residences, and peri-urban neighborhoods of the Bagan Plain.

Figure 10.

Nat Yekan’s northern wall and bas-reliefs and its associated northwest stairway (to the immediate left of the Mucalinda–Buddha).

The following discussion of the Mucalinda–Buddha image is long and somewhat complicated, but this extended consideration of the image is required because it is arguably the most important piece of iconography in the Nat Yekan tank. Be that as it may, it is not a common image at Bagan, and variations of this iconographic representation in both South Asia and Southeast Asia require us to explore why this particular representation was given such a prominent position inside the tank. We believe that the use of this precise rendition of the Mucalinda–Buddha image was purposeful and that it was the key element that sacralised the water at the liminal point where it left the tank and entered the wider Bagan world. As the water flowed over the Mucalinda–Buddha’s head, it was symbolically purified, imbued with the qualities of fertility, and intricately connected to the institution of kingship and the notion of kingly guarantees of health and prosperity.

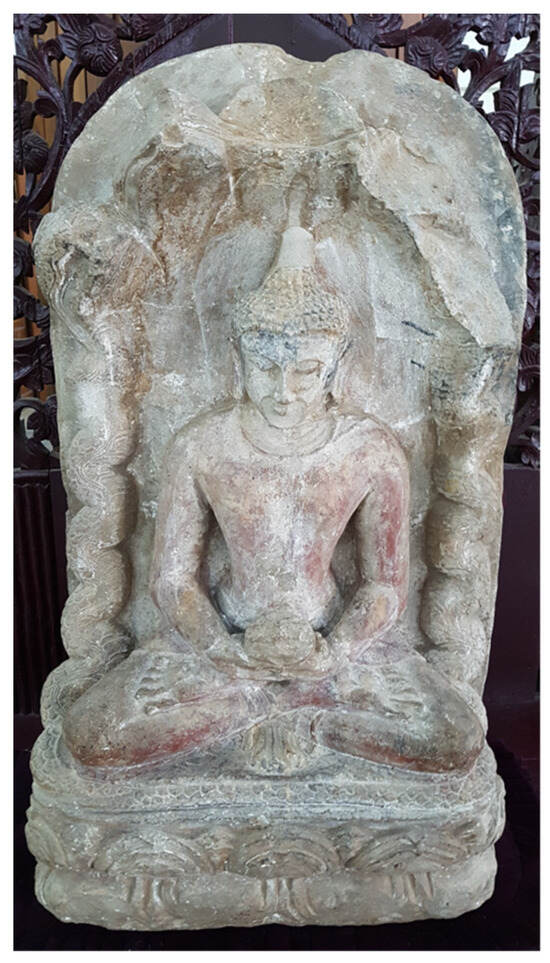

3.3.1. Mucalinda–Buddha or Nāga–Buddha

Nat Yekan’s Mucalinda–Buddha image depicts Gottama Buddha sitting on 5–6 coils of a nāga’s tail, in dhyānamudrā (meditation) pose (hands folded in the lap and facing upwards), with a 5–7 headed nāga hood protecting him from above (Figure 11). The middle head of the nāga hood appears larger than the others. The Buddha element is smaller in size than one would expect, at least when compared to the size of the nāga tail and hood elements. The reasoning behind this discrepancy is unclear, but it is interesting, especially considering the fact that in Bagan’s mural corpus, the Buddha is often portrayed as exceptionally large in size compared to the other elements in the scene, likely an artistic convention meant “to signify his elevated status” (Poolsuwan 2014, p. 31).

Figure 11.

Close-up of the eroded Mucalinda–Buddha image in the Nat Yekan tank (left) and a similar Dvāravatī-style image from the 8th—10th centuries CE (right), the latter currently in the National Museum in Bangkok.

3.3.2. The Mucalinda–Buddha Story

Beyond the relatively small size of the Buddha component vis-à-vis the nāga elements, the Nat Yekan bas-relief is a comparatively orthodox rendition of the Mucalinda–Buddha image, which refers to the 6th week after enlightenment, when the Nāga King or Nāgarāja—conventionally referred to as Mucalinda—rose up from the underworld to protect the meditating Gotama Buddha during a torrential downpour that lasted seven days. The Nāga King accomplished this goal by wrapping seven coils of his tail around Gotama’s body and covering the Buddha’s head with his wide hood (Gaston-Aubert 2010, p. 118; see also Galloway 2006, p. 250; Karlsson 1996, p. 197; Thidar 2016). Traditional Pāli sources regularly describe the Mucalinda hood as consisting of a single, albeit very large head, although later texts often refer to the hood as being polycephalous, with seven separate heads (Gaston-Aubert 2010, pp. 118–19; see also Galloway 2006, p. 250).

3.3.3. Development of the Iconography

A polycephalous nāga hood serving to protect the head of a deity is a common iconographic element in many of the religions that emerged in South Asia—including Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism—and this element may also be accompanied by depictions of the serpent’s coils (Gaston-Aubert 2010, p. 117; Luce 1969, pp. 171–72). Indeed, it is likely in the artistic traditions of South India where the roots of the Mucalinda–Buddha image are to be found (Gaston-Aubert 2010, p. 120; Thidar 2016). In South India, the image can be traced back to 2nd to 5th century CE bas-reliefs used to embellish stūpas (Gaston-Aubert 2010, pp. 116, 124; Murphy 2010, p. 275). Nevertheless, Mucalinda–Buddha imagery was never popular in India, being described by some as a “marginal” iconographic element (Béguin 2009, p. 149) and relating to what others refer to as an interesting but comparatively insignificant episode in Gotama Buddha’s life (Karlsson 1996, p. 197). That said, the relationship between deities and a multi-headed nāga is a significant symbol in India, and includes not only the Mucalinda–Buddha but also representations of Visnu-reclining-on-Ānanta and Jina protected by a polycephalous serpent’s hood (Coomaraswamy 2006, pp. 14, 24, 27; see also Luce 1969, pp. 171–72). For this reason, it has been suggested that the Buddhists borrowed the idea of the “serpent umbrella” from the Hindus (Coomaraswamy 2006, p. 24).

In terms of sculptural renditions, the roots of the Mucalinda–Buddha iconography can be traced back to Sri Lanka during the 6th to 8th centuries CE, and the Dvāravatī art of Thailand (Figure 11), dating to between the 7th and 10th centuries CE (Gaston-Aubert 2010, pp. 116, 125; Karlsson 1996, p. 198; Luce 1969, pp. 171–72; Murphy 2010, p. 275). It was among the Khmer of 10th to 13th-century Angkor where the Nāga–Buddha image took on its greatest significance as the preeminent state symbol, especially during the reign of Jayavarman VII, who transformed the empire into a Vajrayāna Buddhist state following centuries of Śaivite–Hindu religious dominance (Béguin 2009, p. 149; Gaston-Aubert 2010, pp. 117, 130, 135; Guthrie 2004, p. 152; Karlsson 1996, p. 198; Murphy 2010, p. 275). That said, it has been suggested that the Nāga–Buddha image at Angkor was, at the time of its greatest popularity, no longer referencing the Mucalinda story but rather had become symbolic of a “supreme” Buddha deity of unknown identity (Gaston-Aubert 2010, pp. 135–36, 140).

The most orthodox iconographic rendition of the Mucalinda episode depicts the Buddha in dhyānamudrā pose (mediation), seated on the coils of the nāga, with the latter’s polycephalous hood extending over the top of Gotama’s head in order to protect him from the falling rains (Gaston-Aubert 2010, p. 117; Karlsson 1996, p. 194; see also Galloway 2006, pp. 159, 287). In some of the earliest Mucalinda images in South Asia, the nāga hood is depicted with five heads, although seven-headed versions also occur (Gaston-Aubert 2010, p. 119). In 6th to 8th-century Sri Lanka, seven heads were initially common, but nine heads eventually began to dominate (Gaston-Aubert 2010, p. 125). Five heads are also common in the Dvāravatī art of the 7th to 10th centuries CE, although seven become the norm over time (Gaston-Aubert 2010, pp. 126–29). In Thailand’s Khorat Plateau, one Sema (boundary) stone dating back to the 8th—9th centuries CE depicts a five-headed nāga hood (Murphy 2010, p. 274), while another exhibits a Mucalinda hood with eight heads (Murphy 2010, pp. 274–75). In post-Dvāravatī renditions from northeastern Thailand, dating back to the second half of the 10th century, three, five, and seven-headed examples occur (Gaston-Aubert 2010, pp. 131–32, 138). In the Angkorian region, during the mid-10th to early-11th centuries CE, three, five, and seven-headed examples were also present (Gaston-Aubert 2010, pp. 133–34, 138). By the 11th century, however, the Khmer examples became standardized, with the nāga hood regularly exhibiting seven heads (Gaston-Aubert 2010, p. 134). In terms of other variations in hood style, the heads comprising the hood are all the same size in 6th to 8th-century Sri Lanka (Gaston-Aubert 2010, pp. 120, 125), but in other instances, the central head is larger, as in some of the latest examples in the Dvāravatī corpus (Gaston-Aubert 2010, p. 128).

Also noteworthy is a noticeable divergence from the textual entries documenting the Mucalinda story, specifically the fact that rather than being wrapped in the nāga’s coils—which is the case in one of the earliest South Asian reliefs from Gandhāra (Gaston-Aubert 2010, p. 120)—most symbolic representations depict Gotama Buddha sitting on the serpent’s coils, which form a type of pedestal or throne (Gaston-Aubert 2010, p. 116). This may simply be an insignificant deviation, or it may signify that some other meaning is being represented, one that is not restricted to the Mucalinda–Buddha narrative (Gaston-Aubert 2010, p. 116). Alternatively, it may also imply that covering the Buddha’s body with coils was considered “inauspicious” (Gaston-Aubert 2010, p. 120), and it was thus a portrayal that was simply not favored by pious artists.

There is also variation in terms of the number of serpent coils making up the Buddha’s throne. In 6th to 8th-century CE Sri Lanka, one to three coils were used, but over time, three coils became the norm (Gaston-Aubert 2010, p. 125). Three coils are also found in the Dvāravatī art of Thailand dating back to the 7th to 10th centuries CE (Gaston-Aubert 2010, pp. 126–27). That said, stucco examples with five to seven coils have also been found in the Dvāravatī region (Gaston-Aubert 2010, p. 129). Post-Dvāravatī renditions from northeastern Thailand, dating back to the second half of the 10th century, include examples with what appear to be single-coil thrones (Gaston-Aubert 2010, pp. 131–32), although generally, the number of coils depicted in the corpus from this region is “inconsistent” (Gaston-Aubert 2010, p. 138). Among the Khmer, examples of the Nāga–Buddha image dating back to the mid-10th to early-11th centuries CE exhibit one to three coils (Gaston-Aubert 2010, pp. 133–34), but with the onset of the 11th century, three coil renditions became the standard (Gaston-Aubert 2010, pp. 134–35). In summary, it appears quite common for Mucalinda–Buddha images to have far fewer than the seven coils referred to in the traditional South Asian Buddhist texts (Gaston-Aubert 2010, p. 118).

It is also generally acknowledged that, to be true to the Mucalinda story, Gotama Buddha should be seated and positioned in the dhyānamudrā or meditation pose, with hands folded in the lap and facing upwards (Gaston-Aubert 2010, p. 121; Murphy 2010, p. 274). It is therefore interesting that there is also significant variability when it comes to how the Gotama Buddha is positioned and which mudrā (hand gesture) is depicted. In the early South Indian artistic corpus, one can see examples of the abhayamudrā (fearlessness and reassurance) pose in association with a clear representation of the Mucalinda–Buddha episode (Gaston-Aubert 2010, pp. 121, 124). That said, South Indian Mucalinda depictions eventually began to adhere to the expected dhyānamudrā or meditation pose, in addition to showing the Buddha sitting on the Nāga king’s coils and beneath his multi-headed hood (Gaston-Aubert 2010, pp. 121, 123). Elsewhere, the teaching gesture or vitarkamudrā appears in Mucalinda depictions of the artwork from the 7th to 10th century CE Dvāravatī (Gaston-Aubert 2010, p. 126). In Thailand’s Khorat Plateau, Sema (boundary) stones dating back to the 8th—9th centuries CE also depict the Buddha in vitarka mudrā (discussion and/or teaching), a common rendition in the Dvāravatī art corpus, and thus one that “should come as no surprise” when considering its inclusion in the Mucalinda–Buddha artistic corpus from the region (Murphy 2010, p. 274). Murphy even posits that the Dvāravatī artists may have been attempting to blend together two parts of the Mucalinda story: (1) the beginning of the story, when Mucalinda served as the Buddha’s protector when faced with a torrential storm (represented by the coil throne and nāga hood); and (2) the second part of the story, when Mucalinda took on a human form to listen to the Buddha’s teachings (represented by the vitarka mudrā).

Guthrie (2004, pp. 153–54) posits that in the Angkorian realm, there was a shift away from the traditional Mucalinda–Buddha iconography in the early 13th century—which had previously seen the Buddha in the orthodox and expected dhyānamudrā or meditation pose—after which time, the Buddha in bhūmisparśamudrā (aka māravijayamudrā) or earth-touching (calling the earth to witness) pose became more common. The bhūmisparśamudrā specifically refers to the episode wherein, prior to enlightenment, the Buddha reaches down with his right hand to touch the ground and call up the Earth Goddess, Vasundharā (aka Bhūmidevī), from the underworld to bear witness to all his good deeds. Through this act, he is able to defeat the evil Māra (Karlsson 1996, p. 195). In the Thai version of the story—commonly depicted in Cambodia and Myanmar—the Earth Goddess, Torani, wrings out her long hair, causing a flood that washes away Mara and his army (Karlsson 1996, pp. 195–96). This bhūmisparśamudrā symbolism at Angkor has therefore been interpreted as a conflation of two events: the defeat of Mara, which occurred prior to enlightenment, and the Mucalinda–Buddha episode that occurred in the 6th week after enlightenment (Guthrie 2004, pp. 153–54).

Finally, there is considerable variation in terms of how the Gotama Buddha is seated on the nāga’s coils. One 6th to 7th-century North Indian image depicts the Buddha in the full-lotus or vajrāsana position (Gaston-Aubert 2010, p. 124). In contrast, 6th to 8th-century CE Sri Lankan depictions initially favored the “loose half-lotus” position, with ankles crossed, but eventually switched to the standard half-lotus or cross-legged position, alternatively referred to as the vajrāsana or full paryaṅkāsana (Gaston-Aubert 2010, p. 125). The “loose” half-lotus position (vajrāsana) has also been documented in the 7th and 10th centuries CE Dvāravatī artistic corpus (Gaston-Aubert 2010, pp. 126–29). In Thailand’s Khorat Plateau, one Sema (boundary) stone dating back to the 8th—9th centuries CE also depicts the Buddha sitting on the nāga coil throne in the “loose half-lotus” position, ankles crossed (Murphy 2010, p. 274). A contemporaneous Sema stone from the same area shows the Buddha seated on the coils in full-lotus or vajrāsana position (Murphy 2010, p. 274). In the post-Dvāravatī period in northeastern Thailand (i.e., the second half of the 10th century), the loose half-lotus position with ankles crossed was preferred over the vajrāsana or full payaṅkāsana (Gaston-Aubert 2010, p. 138). Among the Khmer, the body position became standardized overtime, generally conforming to the vajrāsana or full payaṅkāsana by the beginning of the 11th century CE (Gaston-Aubert 2010, p. 138).

3.3.4. The Mucalinda–Buddha Image in Myanmar

Some have suggested that the Mucalinda–Buddha image first appeared in mainland Southeast Asia as part of the Pyu and Mon artistic corpus (Guthrie 2004, p. 152; c.f., Luce 1969, pp. 171–72). Others, however, note that Mucalinda–Buddha images have only been carved in Myanmar since the 11th century CE, based on early representations from India (Thidar 2016). In Myanmar, Mucalinda–Buddha images are generally referred to as “Nagāyon Pharā”, and both ancient and contemporary renditions can include one, three, five, or seven-headed hoods (Thidar 2016).

3.3.5. The Mucalinda–Buddha Image at Bagan

The Mucalinda–Buddha story was clearly known at Bagan (Luce 1969, pp. 171–72)—showing up in a small range of depictions—and it remains a relatively popular image in Myanmar today (Galloway 2006, p. 65; Karlsson 1996, p. 200–1), albeit in a wide range of iconographical representations (Thidar 2016). Nevertheless, the story seldom shows up in Bagan-era inscriptions (Galloway 2006, p. 61), and the Mucalinda–Buddha image was infrequently used at classical Bagan (Karlsson 1996, p. 198), especially when compared to the plethora of Buddhas shown in bhūmisparśamudrā or “earth-touching” pose (Karlsson 1996, p. 196). This is significant from a regional perspective because, although the earth-touching pose has been suggested to be the “most frequently represented episode in Buddhist art” (Béguin 2009, p. 48), and it is commonly depicted in the epigraphic and artistic traditions of Myanmar and Thailand, it was rarely utilized in Cambodia until the 12th century CE (Karlsson 1996, p. 196).

The Mucalinda–Buddha motif first appears at Bagan in conjunction with the late 11th-century brick and stucco, high-relief image located in the western corridor of the Myinpyagu temple (Monument #1493; Karlsson 1996, p. 200; Luce 1969, pp. 139, 171–72, 292–293, Plate 152c). The Buddha is framed by nāga coils and protected by a five-headed hood (Luce 1969, pp. 171–72). Interestingly, this image sits on a lotus throne instead of nāga coils (Karlsson 1996, pp. 200, 209), and it also exhibits the bhūmisparśamudrā pose (earth-touching) rather than the “deep meditation” dhyānamudrā pose (hands folded in the lap and facing upwards; Karlsson 1996, p. 194; see also Galloway 2006, pp. 159, 287). This has led some to suggest that the image may not be specifically referring to the Mucalinda–Buddha story of the 6th week following enlightenment (Galloway 2006, p. 287).

Another early Mucalinda–Buddha image from Bagan can be found in King Kyanzittha’s aptly named Nāgayon pagoda (Monument #1192; Thidar 2016; Luce 1969, pp. 171–72). Dating back to the early 12th century, this image is again not exactly true to the Mucalinda story, given that the Buddha figure is standing upright in abhaya-vara mudrā pose—conveying fearlessness and reassurance, as well as charity and compassion—rather than seated in dhyānamudrā or deep meditation.

At the Kyauk-ku-umin pagoda (Monument #154), also dating back to 11th century CE, there is a stone sculpture depicting the Mucalinda–Buddha episode (Figure 12). The Buddha is seated in the full-lotus (vajrasana) position on a single serpent coil, holding an alms bowls in dhyānamudrā meditation pose, and protected by a nāga hood with five heads (Galloway 2006, p. 156; Thidar 2016; Luce 1966, p. 5; 1969, pp. 139, 171–72, Plate 142c). The alms bowl may indicate that the scene is referencing the pre-enlightenment episode, wherein, after fasting for 49 days and receiving sustenance from the maiden Sujata, Gotama Buddha castes the golden bowl he ate from into the river, where it eventually sank and settled alongside the bowls of the previous three Buddhas, thereby alerting the Nāga king that Gotama was on the verge of becoming the next Buddha (Galloway 2006, pp. 65, 272). In other words, this iconography suggests that the image may not be symbolic of the torrential storm that occurred during the 6th week following enlightenment.

Figure 12.

Mucalinda–Buddha image from the Kyauk-ku-umin pagoda.

In terms of portable sculpture, a small bronze Mucalinda sculpture with a five-headed hood and two coils, and the Buddha in bhūmisparśamudrā (earth touching/calling the earth to witness) pose, is said to have come from the Shwezigon Monastery (Karlsson 1996, pp. 200–1). A small, unprovenanced Mucalinda–Buddha sculpture, possibly made from a combination of slate and sandstone, is also displayed in the Bagan Museum. Interestingly, this image adheres closely to the orthodox iconography associated with the Mucalinda story, as Gotama Buddha is seated in dhyānamudrā pose (deep meditation), on a single nāga coil, beneath a seven-headed nāga hood (the central head being larger than the others). The Mucalinda–Buddha image is also regularly found in the corpus of andagu sculptures from Bagan. These are small (<30 cm high), portable tablets dating from the 11th to 13th centuries CE. Made from a tan colored pyrophyllite and depicting multi-tiered registers containing images of the Buddha’s life, these tablets may have been placed inside niches within pagodas (Bautze-Picron 2003, p. 14; Luce 1969, p. 154; e.g., Fraser-Lu and Stadtner 2015, pp. 144–45). The Mucalinda–Buddha image also shows up as a component of the iconic tableau on Bagan’s terracotta votive tablets from the 11th to 12th centuries CE (Fraser-Lu and Stadtner 2015, pp. 140–41).

The Mucalinda–Buddha image also appears in some of the mural art associated with Bagan’s temples, including on the Mon Gu (Monument #418) temple’s south wall, west side (Luce 1969, pp. 349–50), and in the 11th-century CE Phato-hta-mya temple (Monument #1605; Bautze-Picron 2003, p. 41). A Mucalinda–Buddha image is similarly depicted in a mural within the Maung-yon-gu temple, dating back to the 13th century CE (Monument #600; Bautze-Picron 2003, p. 41, Plate 40). The Gotama Buddha in this image is seated in the full-lotus (vajrasana) position, possibly on a stone throne, in dhyānamudrā meditation pose, holding what appears to be an alms bowl. The Buddha is protected by a nāga hood with fifteen heads, the central head being substantially larger than the others.

3.3.6. Summary

In summary, the nāga-related depictions—especially those from 11th-century Bagan—do not portray the Buddha in the precise pose discussed in the Mucalinda story, wherein Gotama Buddha was seated on the nāga’s coils, sheltered by his hood (normally adorned with seven heads), in the meditating dhyānamudrā pose, with the hands resting in the lap and facing upwards. Significantly, this is what appears to be depicted on the wall of the Nat Yekan tank. For this reason, the Nat Yekan image is one of the only motifs at Bagan that faithfully follows the textual narrative and conventions of Buddhist art when it comes to depicting the Mucalinda event. To reiterate, although the Mucalinda image with a coiled tail and nāga hood has long been depicted in Myanmar—albeit less often than in Cambodia—it is the divergent bhūmisparśamudrā or “earth-touching” pose that dominates the Myanmar tradition (Karlsson 1996, pp. 201, 209). On one hand, this hybrid motif may represent an effort to connect with the combined underworld forces (the nāga and the Earth Goddess) that had aided the Buddha during times of duress, and in doing so tap into the collective font of the supernaturally based “fertility, wealth, and power” that formed the basis of classical kingship and kingly legitimacy in Southeast Asia (Karlsson 1996, pp. 208, 215). A variation of this interpretation sees the image as a hybrid of the original enlightenment (1st week) and the Mucalinda story (6th week), although there is little support for this explanation for the divergence from the orthodox artistic convention (Karlsson 1996, p. 212). Ultimately, “The making of Buddha images is…a very conservative form of art”, and the bhūmisparśamudrā-style Mucalinda motif must make sense with this consideration in mind (Karlsson 1996, p. 214).

That said, it has also been suggested that the early hūmisparśamudrā-style Mucalinda motif in the Myinpyagu temple at Bagan was simply rendered incorrectly and that it mistakenly provided a newly accepted archetype for the rendering of future images at Bagan and beyond (Karlsson 1996, pp. 209, 214). It is also plausible that the bhūmisparśamudrā-style Mucalinda image may not depict Gotama Buddha at all, but rather a Buddha other than Gotama, an amalgam or “general Buddha”, a local Buddha figure, or possibly even a “supreme Buddha”, although all of these interpretations remain highly speculative (Karlsson 1996, pp. 209–211). Finally, it has also been postulated that the nāga hood motif is essentially derived from depictions of the branches of the Bodhi tree, which would throw the entire Mucalinda designation into question if there were more support for the original assertion (Karlsson 1996, p. 211).

In considering all of the variations inherent in the depiction of the Nāga–Buddha imagery across South and Southeast Asia, it does seem plausible that the various renditions that have been interpreted as depictions of the Mucalinda episode may not necessarily always be symbolic of that specific event. In fact, it seems that as time went on, the Nāga–Buddha image in Southeast Asia came to signify many different things, above and beyond the original Mucalinda–Buddha episode associated with the torrential storm that arrived in the 6th week following enlightenment (Guthrie 2004, p. 153). For example, Gaston-Aubert (2010, p. 121) posits that this iconography might, at times, also have been used to represent “the proselytizing power of Śākyamuni [aka Gotama] over indigenous godlings”, or it might even be symbolic of a “transcendental, cosmic Buddha”. Indeed, the Khmer adoption of the Mucalinda–Buddha image, an iconographic representation that had initially developed in South Asia and Thailand, may have been stimulated more by long-standing local traditions relating to nāga worship and nāga-related ancestor veneration than by a desire to connect with the original Mucalinda episode and its associated iconography and cosmological significance (Gaston-Aubert 2010, pp. 137–38, 140; Guthrie 2004, pp. 154–55).

More broadly, Marcus (1965, p. 189) posits that by achieving enlightenment, Gotama Buddha had gained a new monarchical status. This status, although known to be much greater than the status of a king, resembles the rights that kings possess over their realms. The depiction of the Nāga King protecting the Buddha is thus seen as a type of royal recognition in which the Nāga king acknowledges the ownership of the land that the Buddha, in a similar manner to that of a king, has gained through the attainment of enlightenment. Through enlightenment, Gotama Buddha has therefore achieved a new status and gained, through the coils formed by the Nāga under him, his proper throne (Marcus 1965, pp. 189–90). This interpretation is supported further by the idea that the Nāga King who protected the Buddha is considered the son of the earth and, more importantly, the protector and guardian of people of royal descent (Marcus 1965, p. 189).

Finally, in more “folk” interpretations of the Mucalinda–Buddha image, the association between the Nāga King and the Buddha is considered a crucial alliance based on notions of fertility and an abundance of water. According to Bloss (1973, p. 37), the Nāga King is represented as a powerful being capable of supplying the land with the gifts of nature. These gifts bring wealth and, through rainfall, an abundance of crops. A comparable alliance is also believed to exist between a king and the Nāga King, the latter being a guardian of both the land and the watery realm (Bloss 1973, p. 42). Through this alliance, the powers of the Nāga King are provided to the populace through the authority and status of the king. However, given that they were prone to sensuousness, the Nāga was required to follow the law of the Buddha in order to attain greater self-control and provide the benefits of water to the community (Bloss 1978, p. 172). According to this folk perspective, by following the law of the Buddha (Bloss 1973, p. 46)—a law that possessed the greatest status and could be used to circumscribe all other powers—the Nāga King, through his alliance with the king, was able to channel his beneficial powers into the land for the well-being of the community (Bloss 1973, pp. 40, 175).

3.3.7. The Mucalinda–Buddha Image at Nat Yekan

Given the popularity of the bhūmisparśamudrā-style Mucalinda image in Myanmar, and the broader variability exhibited by Nāga–Buddha imagery across South and Southeast Asia, the adherence to the more orthodox dhyānamudrā-style motif at Nat Yekan becomes all the more interesting and significant. Specifically, the depiction of the Mucalinda–Buddha in the more accurate yet uncommon dhyānamudrā (meditation) pose in the Nat Yekan tank must have been purposeful, likely reflecting the close connection the traditional image has to rainfall and flooding (i.e., an abundance of water). Indeed, at its very base, the Mucalinda story, and its associated iconography, not only reflects the fundamental relationship between nāga serpents and water cosmology (Ward 1952, p. 144) but also the critical alliance connecting the Nāga King to Gotama Buddha, and thus the ideological entanglement between rainfall, fertility, and abundance (Bloss 1973, p. 37). In other words, it is plausible that the depiction of the Mucalinda sheltering the Buddha that was carved into Nat Yekan’s wall was meant to reflect how the Nāga King, by abiding by the law of the Buddha, was able to focus his powers of rainmaking, fertility, and abundance to provide well-being to the broader Bagan community. The location of this image, directly beneath the tank’s spillway, supports the idea that the Buddha, in agreement with the Nāga, will infuse the exiting waters with the power of fertility, and in doing so make the plain of Bagan productive, and its people both healthy and prosperous.

3.3.8. Crocodile or Makara (Water Monster)

To the east, and roughly at the same level as the altar area beneath the Mucalinda–Buddha, is a bas-relief depicting a large crocodile that faces to the east. As it is situated in the medium registry, this image is symbolically associated with the surface of the water. In assessing the significance of this symbol, it is worth noting at the outset that the crocodile can appear as a somewhat mundane beast in the Jātaka stories. For example, in the Vanarinda–Jātaka (#57) a crocodile (Devadatta) pretends to be a rock in order to catch and eat the Bodhisattva/Buddha, who has been born as a monkey (Cowell 1895a, pp. 142–43). Elsewhere, in the Susumāra–Jātaka (#208), another crocodile tries to eat the Bodhisattva/Buddha, who once again has been born as a monkey (Cowell 1895b, pp. 110–12). These stories aside, given the corpus of auspicious symbols carved into Nat Yekan’s walls, it is unlikely that the crocodile image is meant to reference such ordinary events.

In our view, the significance of the crocodile image likely relates to the fact that this beast is often conflated with the makara, a mythological beast with a crocodile’s head and a long tail that resembles that of a fish (Karlsson 2006, pp. 82–83). More broadly, crocodiles, makaras, and nāgas are often employed as interchangeable symbols across Southeast Asia (Guthrie 2004, p. 139). As such—not unlike nāga-serpents—when makaras and crocodiles are depicted in the iconography, they are often meant to be interpreted as auspicious symbols associated with both water and fertility (Karlsson 2006, pp. 82–83). The connections that these beasts have with both water and the earth are worth discussing in more detail.

Makaras are often viewed as “celestial monsters” (Béguin 2009, p. 66), but in South Asia, they also served as the vehicle of Gaṅgā, the River Goddess (Guthrie 2004, p. 139), who is associated with prosperity, well-being, and the benefits brought by rivers (Robins and Bussabarger 1970, pp. 42–43). In other words, whereas the River Goddess celebrates the fruitful and productive capacities of the river, the makara—as her vehicle—emphasizes the contrasting capacities of water, including its fearful and destructive connotations (Darian 1976, p. 34).

In Cambodia, crocodiles are also found in symbolic images associated with a local earth deity called Romsay Sok, who wrings water from her hair like the Earth Goddess, Vasundharā (aka Bhūmidevī), but who should not be conflated with the latter, and whose story is not connected to the latter deity’s defeat (māravijaya) of the demon Mara (Guthrie 2004, p. 136). To confuse the situation even more, Cambodian murals are also known to depict the crocodile attacking Mara’s soldiers in the flood waters caused by the Earth Goddess wringing water from her hair during the māravijaya (Guthrie 2004, p. 136). The artistic association between the crocodile, Earth Goddess, and the māravijaya event is believed to have its roots in the Ayutthaya kingdom (Giteau 1975, p. 24; Guthrie 2004, p. 136). Be that as it may, across Southeast Asia, the Earth Goddess, Vasundharā, has long been conceived, to use Guthrie’s words (2004, p. 137), as “the hair-wringing, crocodile-taming instigator of cosmic floods”. Not surprisingly, there are many local manifestations of this deity across the region.

The earliest inscriptions in Southeast Asia referring to the Earth Goddess, Vasundharā, come from Bagan in the 12th–13th centuries CE, where the Goddess is summoned to bear witness to the pouring of water during the act of making donations or oaths (Guthrie 2004, p. 186). Iconographic representations relating to the Earth Goddess also appear at Bagan, Angkor, and Arakan during the same time period (Guthrie 2004, p. 186). Vasundharā remained important across Southeast Asia after the 13th century because she was, in both theory and practice, readily connected to: (1) local and regional traditions concerning water and earth; (2) the mythology of the ancestral nāgī princess as well as the mythical “nāga/crocodile” beasts; (3) the Nāga–Buddha “protector” story and the various nāga cults derived from it; (4) Buddhist consecration rituals, especially those that involved water and calling the earth to witness; and (5) the story of the Buddha’s life—in particular the hair-wringing and māravijaya episode—which was widely disseminated (Guthrie 2004, p. 187). In summing up the significance of Vasundharā in Southeast Asia, Guthrie (2004, p. 188) concludes that: “When respected and propitiated, this omnipotent deity can protect the Buddha, temples, houses, wealth, agriculture, good fortune, an individual’s private body, and by extension, the national body, from attack or invasion by external forces. With a twist of her hair, Vasundharā halts the forces of chaos and dissolution, and sets the world to rights again”.

The crocodile/makara image at Nat Yekan is likely symbolic of these broader themes, particularly those relating to rainfall, fertility, wealth, and prosperity. That said, it is equally possible that the depiction of a crocodile within the Nat Yekan water tank—beyond being a mere reflection of the many virtues of water—represented the duality of water and its destructive qualities. Similar to the conceptions of the nàga-serpent, the crocodile image in the Nat Yekan tank may have served as a reminder that through the powers of the Buddha, the capacities that emerge from water could be subdued, controlled, and channeled for the well-being and the prosperity of the broader Bagan community.

4. Lotus-Bud Pillar

Finally, although it is not a bas-relief, the lotus-bud pillar postulated to have once stood at the center of the Nat Yekan reservoir is worth considering in terms of its potential symbolic meaning (see Figure 4 and Figure 13). Such lotus-bud pillars can be found in various water tanks at Bagan today (see Figure 8). Although they probably serve the practical purpose of measuring water levels, it is also worth considering their potential symbolic significance, especially given the cosmological charged corpus of symbols that would have surrounded the pillar in Nat Yekan tank.

Figure 13.

Nat Yekan’s central pillar hole and support stone.

Lotus flowers are one of the earliest symbols used in Buddhist religious iconography (Karlsson 2006, pp. 74–75). In Buddhist beliefs, the lotus is a multifaceted symbol that relates not simply to water (Coomaraswamy [1935] 1998, p. 33) but also broader notions of creation, purity, and the earth in general (Coomaraswamy [1935] 1998, pp. 19–21). The lotus also represents both the sun and Lord Buddha and can be considered a version of the tree of life (Ward 1952, pp. 136–37) or the “Axis of the Universe” connecting the Earth and the Heavens (Coomaraswamy [1935] 1998, p. 34). In Buddhist teachings, the lotus also gains significance as a symbol of transcendence and enlightenment because: “the lotus flower grows in mud, in slime, but pushes its blossoms up through the mud and the water, thus coming to full bloom above the waters the clean, white color coming from the mud of the earth but never touching it” (Ward 1952, p. 137; see also Bodhi 2005, pp. 71, 145, 252; Ñaņamoli 2001, p. 188).

In both South and Southeast Asia, the lotus has long been considered a symbol of birth, creation, reproduction, purity, and prosperity, and it is thus an icon that is also strongly associated with life-giving and life-sustaining waters (Ward 1952, pp. 136–38, 146). In the South Asian tradition that informed the institution of kingship in classical Southeast Asia, lotus stalks were symbolic of both the creation of the world and the life-giving “amṛta” or ambrosia that continued to sustain the world (Wolters 1999, p. 81). In other words, lotus stalks were symbols of “life risen from waters” (Bosch, as quoted in Wolters 1999, p. 81; see also Ward 1952, pp. 138–45), and they could therefore be used to represent the glory—and thus life-sustaining powers—of the king, as has been demonstrated for the classical Khmer (Wolters 1999, p. 81). It is these broader ideologically charged meanings that—to a large extent—likely stimulated the installation of the central pillar that once stood in the center of the Nat Yekan tank. Also noteworthy is that in the Hindu and Buddhist ideology and water cosmology of South and Southeast Asia, there are strong associations between lotuses, birds—including the haṃsa—fish, and mythical creatures such as the makara (Ward 1952, p. 146). Thus, the lotus pillar fits perfectly with the broader iconography exhibited by the Nat Yekan tank.

5. Conclusions

Nat Yekan’s iconographic corpus makes the most sense if it relates to the period when it served as a collection tank with a spillway that directed overflow water into the Mya Kan reservoir, a time frame that likely spans the 11th to 14th centuries CE. All the symbols carved into Nat Yekan’s walls relate very directly to water and water cosmology. This symbolism supports the idea that Nat Yekan was indeed a water management feature, rather than simply a quarry. It is also true that these various symbols are often associated with each other in the various stories documenting Gotama Buddha’s previous lives (Jātaka stories), and many appear to be specific references to episodes in his ultimate life, wherein he achieved enlightenment. This corpus of auspicious symbols—considered in conjunction with the geographic and cultural contexts in which they were employed—also suggests that Nat Yekan was a particularly sacred water tank, one with extraordinary ideological significance. The various symbols carved into its walls—evaluated both individually and in unison—speak to the tank’s role in the sacralization of water. Specifically, as the water flowed into and out of the tank, the cosmological powers of the various icons imbued it with propitious characteristics encapsulating notions of purity, creativity, fertility, productivity, and prosperity. As this ritually charged water poured out of the tank and ran downslope towards the Mya Kan reservoir and then, beyond—into Bagan’s vast water management network—it carried these life-giving, life-sustaining properties with it, thereby benefiting all the city’s residents. These inhabitants could, at any point in their busy day, look up from their work to see the Tuyin–Thetso range—the most prominent topographic feature on the landscape—and be comforted by the fact that it was from this sacred place that their blessed waters emanated from. King Kyansittha—the builder of the Shwezigon Pagoda and Mya Kan reservoir, likely patron of the Nat Yekan sacred water tank, and proliferator of nāga-serpent and Mucalinda–Buddha iconography (as found in contexts such as the Shwezigon, Nāgayon, and Kyauk-ku-umin pagodas)—was also able to gaze up at the sacred water mountain, knowing that his legitimacy as the guarantor of prosperity for his kingdom had been solidified through his water-related infrastructure projects and associated religious initiatives (e.g., Stargardt 1968).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.I. and R.S.R.; methodology, G.I.; software, G.I.; validation, G.I., R.S.R., S.T.L. and N.C.S.; formal analysis, G.I., R.S.R., S.T.L. and N.C.S.; investigation, G.I., R.S.R., S.T.L. and N.C.S.; resources, G.I.; data curation, G.I.; writing—original draft preparation, G.I. and R.S.R.; writing—review and editing, G.I.; visualization, G.I.; supervision, G.I.; project administration, G.I.; funding acquisition, G.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the NATIONAL GEGRAPHIC SOCIETY, grant number NGS-187R-18.

Institutional Review Board Statement

No institutional ethics board approval was required.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Detailed field reports for this project can be found at https://irawbagan.wordpress.com/ (accessed on 1 January 2024).

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to the Ministry of Religious Affairs and Culture and the Department of Archaeology and the National Museum for allowing us to carry out our field work at Bagan, and for facilitating our research visas. Particularly noteworthy is the encouragement and assistance provided by Archaeology, U Kyaw Oo Lwin, and of International Relations, Daw Mie Mie Khaing. In Bagan, the project benefited from discussions with, and support from, General, U Thein Lwin, U Aung Aung Kyaw, of the Bagan Archaeology Branch, and both Ye Lwin and Nyein Lwin of the Department of Archaeology. The Department of Archaeology in Bagan also provided housing for some of the IRAW@Bagan team members at their compound in Old Bagan, and U Aung Aung Kyaw and his GIS team graciously shared GIS resources useful for our hydrological and settlement studies. We extend our appreciation to U Nandavamsa, Tuyin Monastery, for assisting with our preliminary investigations at the Nat Yekan sacred water tank in 2017, and for helping us with lodging, food, and storage space during our 2018 investigations. Nyi Lynn Seck, of 3xvivr—Virtual Reality Productions (Yangon, Myanmar) donated his time and equipment to help us generate the high-resolution, 3D representation of the interior of the tank. A number of experts in the archaeology of Myanmar also provided us with useful insights and inspiration, including Michael Aung-Thwin, Bob Hudson, Elizabeth Moore, and Janice Stargardt. We graciously acknowledge the generous financial assistance of the National Geographic Society, which funded our 2018 research though an Explorer Grant. Finally, G.I. extends his thanks to Trent University for providing seed funds for the 2017 research program as part of the Vice-President of Research Strategic Initiatives Grant program.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Andaya, Barbara Watson. 2016. Rivers, Oceans, and Spirits: Water Cosmologies, Gender, and Religious Change in Southeast Asia. Trans–Regional and –National Studies of Southeast Asia 4: 239–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]