Shamans are spirit beings that serve as intermediaries between their people and the spirits that influence and structure life. They often use “soul flights” to visit the spirit world to gain information and favors from powerful beings as part of their duties and practices (

Eliade 1964;

Harner [1980] 1990;

Jokic 2008;

Lessa and Vogt 1979, p. 302;

VanPool and VanPool 2023). The importance of soul flights in shamanism has been noted worldwide (

Carr 2021;

Eliade 1964;

Vitebsky 2001) and in Casas Grandes Medio period shamanism, specifically (

VanPool and VanPool 2007). Soul flight typically includes feelings of spinning and vertigo during altered states of consciousness (ASC), that is often interpreted as the shaman’s spirit leaving his/her body and travelling into the lower or upper worlds (

Lewis-Williams and Pearce 2005). Building on previous research, I suggest that the Casas Grandes people associated such feelings of vertigo with soul flight and their travel as spirit beings across their version of the shamanic universe (which included an upper world, middle world that included the visible physical world normally accessible to humans, and the lower world). The Casas Grandes shamans also included other-than-human beings during their shamanic practice. This likely included some living animals (snakes and macaws), plants (tobacco), and human-made objects including animated pottery that was specifically constructed to have characteristics allowing the pot-persons (a term I will define below) to travel to different cosmological realms like their human shaman counterparts. As part of the ritual related to these pot-persons, the Medio Period shamans symbolically and, at least occasionally, literally ritually spun the pots with the intention of replicating the spinning sensation essential to human ASC experiences. In other words, I argue that animals and animated objects were viewed as going through the same ASC-based shamanic experience as humans were, and that humans actively created the conditions to allow animated objects to directly experience ASC. Material manifestations of this are provided by pottery effigies of snakes, humans, and birds that have use-wear on their bottom, indicating a repeated spinning motion, and animals molded, formed, or decorated to give the impression they are spiraling or spinning around the jars’ openings. Birds and snakes are liminal creatures that transcend the limits between the middle world of humans and the upper and lower worlds dominated by typically unseen spirits. Pots decorated with these animals, likewise, were liminal and linked by sympathetic and mimetic magic to the animating spirits of these creatures, making the pots themselves magical made beings (i.e., pot-persons). Through the process of initiating ASC, the physical pots with their animating souls could influence both seen (i.e., physical) and unseen (i.e., spirits) beings and forces to elicit changes in the various layers of the Casas Grandes cosmos.

1. ASC, Soul Flight, and Movement through the Realms

As an analytical concept, anthropologists define shamans as religious practitioners who interact directly with the spirit world through some form of ASC. ASC arenot limited only to shamanic traditions, but ASC, especially trance, is core to shamanic experiences as typically defined (

Glass-Coffin 2010;

Vitebsky 2001). Shamans in each culture have their own practices, pursue their own goals for themselves and/or their clients (e.g., healing and weather control), and are called by different names (e.g., South American curanderos) (

Freidel et al. 1993;

Freidel and Reilly 2022;

Lewis-Williams and Pearce 2005;

Vitebsky 2001). Shamanic ASC practices are found all over the globe, from Australia to the Arctic, and can range in intensity and duration from a sort of daydreaming-like state to catatonic trance states. The rituals used to initiate ASC greatly vary (e.g., Australians walking into their Dreamtime, and Siberian shamans using sound induction based on drumming), reflecting that human neurology and physiology enable people to enter ASC using various methods including fasting, chanting, drumming, sensory deprivation, extreme pain, and/or consuming psychoactive plants. Regardless of the method used, ASC is the gateway to spirits and deities who help cure the sick, bring rain, find lost objects, or otherwise help (or hurt) people medically, physically, emotionally, and/or spiritually.

Worldwide, one of the hallmarks of shamanic ASC is entoptic imagery, which includes grids, nets, dots, spirals, zigzags, arcs, honeycombs, checkerboards, tunnels, and shimmering or flashing lights that can be interpreted as stars or flickers of bird wings (

Figure 1) (

Lewis-Williams and Dowson 1988;

Siegel and West 1975). Shamans see entoptic imagery during the initial stage of ASC even when they cannot physically ‘see’ because of darkness or blindness (

Bressloff et al. 2001;

Siegel and West 1975); these entoptic images are mental manifestations that are products of the brain, as opposed to a distortion of actual vision, coming from the optic nerve. Further, shamans often experience a sensation of vertigo that may be intense enough to give the perception of falling or flying. Entoptic forms begin to overlap and integrate with each other (e.g., grids begin to overlay other grids), and then begin to rotate, forming a tunnel (

Lewis-Williams and Dowson 1988, Fig. 1;

Siegel and West 1975, Figures 6 and 13). When paired with the entoptic imagery, the falling/flying sensation is typically interpreted as the shaman’s spirit falling or being pulled through a portal. This sensation is generally called soul flight, magical flight, or out-of-body travel (

Lewis-Williams and Dowson 1988, p. 210;

Siegel and West 1975;

Vitebsky 2001, p. 6). Not all shamanic experiences include soul flight and, indeed, not all shamanic traditions incorporate soul flight (

Peters and Price-Williams 1980;

Vitebsky 2001, p. 10), but it is a common component of many traditions and has been documented extensively using ethnographic (e.g.,

Winkelman 2002), historical (e.g.,

DeConick 2017), and experiential (e.g.,

Balzer 1996) data. For example,

Figure 2 is a redrawing of a blue lattice-tunnel that Sheridan drew based on marihuana and THC intoxications (

Siegel and West 1975, Figure 6). Similar experiences are reported by groups such as the Wauja shamans and the Desana shamans of Brazil that smoke hallucinogenic tobacco to induce ASC (

Barcelos Neto 2018;

Lewis-Williams and Pearce 2005;

Wilbert 1987, p. 127). The Desana shamans’ pot stand is even designed to form the vortex seen in ASC with the “hourglass” shape symbolizing the restricted entrance/tunnel that opens between the world of the here-and-now and the spirit realm that the shamans visit (

Figure 3; redrawn from

Lewis-Williams and Pearce 2005). Experimental observation conducted by P.D. Newman (personal communication 2023) likewise reports that

N. rustica intoxication causes intense vertigo and feelings of vertigo, and soul flight is central to tobacco shamans in South America, Mesoamerica, West Mexico, and the American Southwest (

VanPool and VanPool 2007).

As the vision continues, shamans frequently report feeling as if they emerge into another realm full of creatures and spirits.

Lewis-Williams and Dowson (

1988) argue that the visions encountered in ASCs are the results of blended entoptic designs as the mind forms larger and large patterns from them, causing the mind to perceive beings and landscapes appropriate for their cultural context (e.g., the Inuit experience an underwater seascape with marine animal spirits governed by the sea goddess Takánakapsaluk (

Rasmussen 1979)). Putting the sequence of experiences together, shamans often undergo what is referred to as the

shamanic journey in the classical sense or the

classic shamanic journey of initiating ASC, entering into a trance (starting with the perception of entoptic images and possibly olfactory, audible, or tactile sensations), experiencing an intense feeling of vertigo and falling/flying, and then perceiving more complex layers of entoptic images that are interpreted as visions (which again may include olfactory, audible, or tactile components) (

Sharon 1993, p. 166; see also

Myerhoff 1976, pp. 102–3).

Goodman (

1990, p. 71) describes this tunnelling or flying experience as going through the “spirit’s doorway”, while

Lewis-Williams and Pearce (

2005) called this phenomenon transcosmological traveling.

My own participant observation in ASC replicates the general framework noted by others. Over the last four years, I have worked with the Cuyamungue Institute (established by Felicitas Goodman) to produce ASC without the use of entheogens using Goodman’s Ritual Body Posture practice (

Goodman 1990). I follow their ritual protocols and hold a posture while listening to a rapidly beating drum or rattle for 15 min. On numerous occasions, I have experienced the sensation of quickly spinning; it can be horribly dizzying and does strongly correspond to the feeling that I was moving through time/space into another realm. Sometimes, I fall deep into the earth; other times, I fly out into the cosmos. Many times, I found myself transforming into a flying bird during this journey. Spinning as an aspect of ASC is an interesting neurological phenomenon that needs more study.

2. Casas Grandes Shamans, ASC, and Soul Flights

The Casas Grandes region is along the modern US/Mexico border centered primarily in what is now northern Chihuahua, Mexico (

Figure 4).

Pailes and Searcy (

2022) provide a general overview of Casas Grandes prehistory, but, briefly, the Casas Grandes Medio Period (AD 1200–1450) religious system included a shamanic practice related to the broadly distributed Flower World cosmology common across Mesoamerica and the North American Southwest (

Hill 1992;

Mathiowetz and Turner 2021). Various entheogens are used in cultures influenced by the Flower World cosmology (e.g., the Wixárika use peyote), but current evidence indicates that the Medio Period people primarily used tobacco and perhaps datura (

VanPool and VanPool 2007).

VanPool et al. (

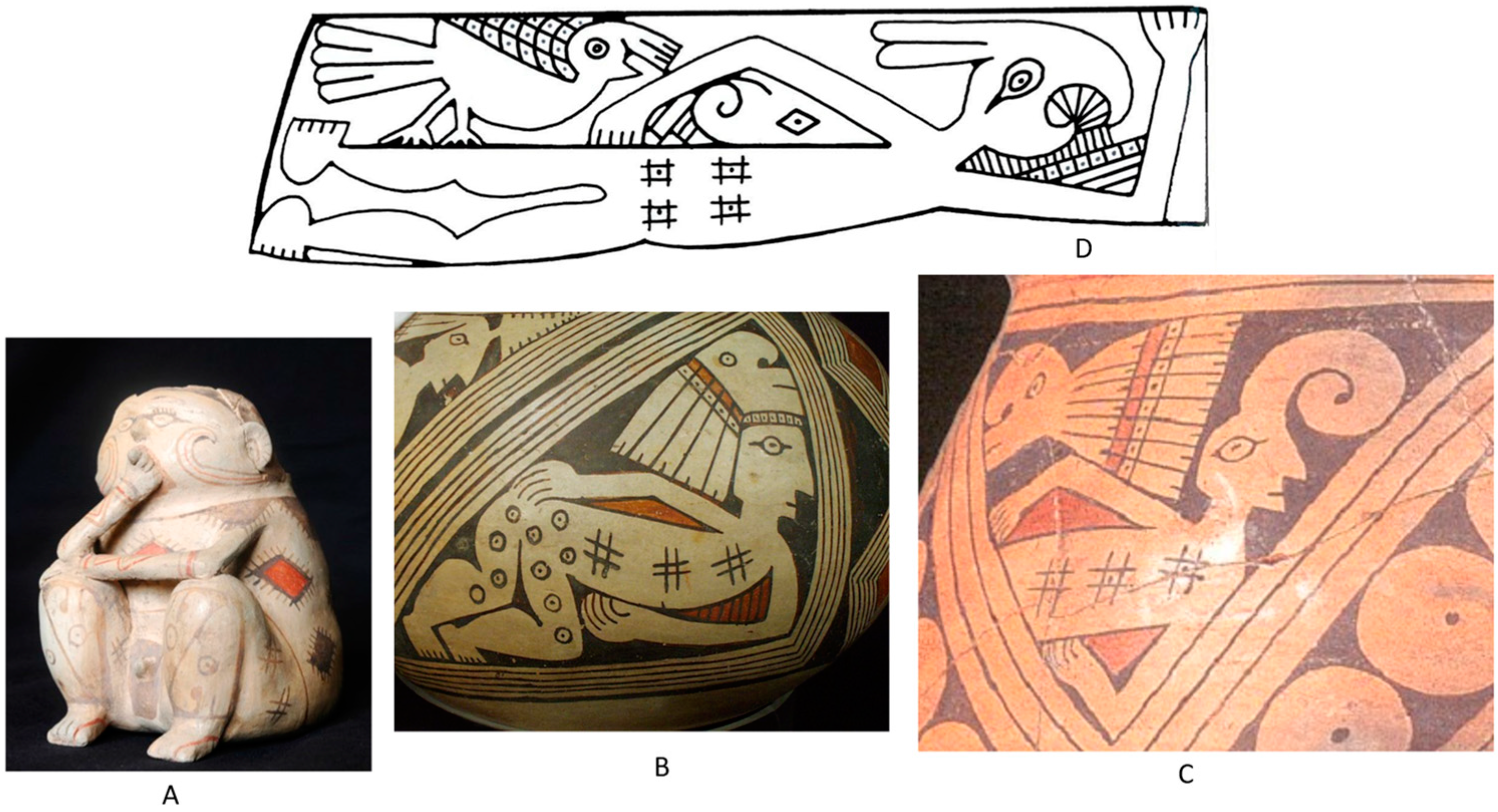

2023) have suggested that shamanic transformation using tobacco and a distinctive ritual posture was an elite activity that was an important and underlying religious theme in Medio Period architecture, pottery, and general material culture. This shamanic tradition was reflected in Medio Period polychrome pottery and can be identified using a distinctive design resembling a pound sign (hashtag) that is generally limited only to male effigies, male smoker effigies, painted figures with headdresses, painted anthropomorphs, horned-plumed serpents, and snakes (

Figure 5). In addition to the pound sign, this imagery was also linked such that male effigies were more likely to be associated with horned-plumed serpent and snake imagery than were female effigies, and the painted anthropomorphs were linked to the male effigies by design similarities and even directly on the same pot (

VanPool and VanPool 2007). The male effigies were shown smoking cylinder pipes while kneeling on one knee or simply shown sitting with both knees drawn to their chests. These male effigies also included males wearing sashes and distinctive ceremonial sandals indicative of high-status clothing (

VanPool et al. 2023). I argued, based on the repeated associations created by the pound sign and horned-plumed serpent themes, that the kneeling males were shamans beginning their shamanic journey by smoking (hallucinogenic) tobacco, dancing, and then transforming into horned and/or macaw-headed anthropomorphic spirits as they flew to the spirit world to interact directly with typically inaccessible spirit entities while in ASC (

VanPool et al. 2023). They then returned to the here-and-now as they regained consciousness and told their people of the promises, desires, and structure of the horned-plumed serpent and the other denizens of the spirit world (

VanPool and VanPool 2007; see also

Wilbert 1987 for similar tobacco-based practices in other Native American groups).

The arrival into the spirit realm was depicted in

Figure 6, a rollout from a Medio Period pot, in which the fully transformed shaman interacted with the horned/plumed serpent and a motif I call the double-headed macaw diamond.

Charles Di Peso (

1974, p. 548) noted the veneration of the horned-plumed serpent at Paquimé, the largest Medio Period settlement in the region, and across the entire Casas Grandes region (see also

Phillips et al. 2006;

Schaafsma 2001). It was a repeated theme in rock art and Medio Period imagery, as well as being represented by a 113 m-long ceremonial mound at Paquimé (

Di Peso et al. 1974, vol. 5, p. 478). Following the work of Marc Thomas (

Thompson and Brown 2006) and others (e.g.,

Parsons [1939] 1996; see also

Schaafsma 2022) that link macaws to sun imagery,

VanPool and VanPool (

2007, p. 122) suggested that the double-headed macaw diamond motif is also an important sun deity in the Casas Grandes world. Further, a distinctive bird that did not correspond to any native birds in the North American Southwest travelled on the leg of the shaman (

Figure 5 and

Figure 6). The Casas Grandes potters often depicted birds with enough detail to determine their species (e.g., horned owls,

Bubo virginianus; killdeer,

Charadrius vociferus; and macaws,

Ara macao and

Ara militaris; see

VanPool and VanPool 2007). Further, animals and humans existing in the physical world were depicted in effigy in Casas Grandes pottery (e.g., macaw effigies and human effigies) but spirit creatures like the horned-plumed serpent were depicted on pottery only as two-dimensional painted images (

VanPool and VanPool 2023). This non-natural bird was always painted and was typically associated with transformed shamans (who were also painted as opposed to being shown in effigy like the smoking males).

VanPool and VanPool (

2007) suggested, as a result, that this bird was a spirit tutelary animal that accompanied and perhaps even guided and protected the transformed shamans during their spirit flights. Based on their dual association with the transformed shaman and with female effigies,

VanPool and VanPool (

2007) also proposed that the tutelary bird was specifically a feminine spirit helper and perhaps reflected literal female helpers that watched over the shamans during their trance. The Casas Grandes shamanic transformation from human smokers to spirit anthropomorphic beings undertaking soul flight to a spirit realm fits the basic structure of the classic shamanic journey. Support for this interpretation was provided by the presence of entoptic forms as reflected by the grids and nets that were present around the transformed Casas Grandes shamans and their deities (

Figure 6). Further, entoptic imagery was integrated into both the horned-plumed serpents and the double-headed diamond macaw—the horned-plumed serpents were two large zigzags, the double-headed diamond macaws were squares, and all had entoptic images on their bodies.

Casas Grandes iconography is consistent with

Lewis-Williams and Dowson’s (

1988) argument that perceptions of spirit beings and landscapes are created by overlapping entoptic images during the trance state as mentioned above and fits the general pattern in shamanic imagery worldwide (

Bostwick 2002;

Whitley 2000,

2009). Further, the presence of these details in

Figure 5 and

Figure 6, the smoker effigies, and pots with anthropomorphic images indicate that the shamans either decorated some or all of the pots or at least described them in sufficient detail such that the potters could create nuanced representations of the ASC experience (

VanPool and VanPool 2007).

3. Other-than-Human Persons and the Shamanic Importance of Made Beings

Many animistic frameworks hold that spirit essences animate the universe, structure the world of the here-and-now, and are present in nature (e.g., the wind and thunder), in living plants and animals, and in many nonorganic objects (e.g., certain mountains, stones, and ponds) (

Swancutt 2023). In this framework, objects and physical phenomena have their own volition and agency, giving them spiritual vitality and the ability to impact the world around them (

Carr 2021;

Vitebsky 2001). The objects, consequently, are “other-than-human beings” that exist separately from humans, but that can interact with humans in co-operative or antagonistic ways (

Hallowell 1960; see also

Eliade 1964;

Vitebsky 2001, pp. 12–13). Within most animistic cultures, completing any task is fundamentally based on social/reciprocal relationships between humans and these other-than-human persons that infuse the world (

Bird-David 2018;

Eller 2007;

Halifax 1979, pp. 5–6;

1982;

Hallowell 1960). In the North American Southwest, these spiritual relationships are so central and so pervasive that researchers such as

Fowles (

2013) contend the word “religion” has no analytical meaning in Puebloan culture. For example, in the Puebloan Southwest, the springs that give water are viewed as spiritual entities as opposed to inert natural resources and the clouds are ancestors bringing needed rain. Springs, consequently, must be cared for as spiritual entities throughout the year (

Beaglehole and Beaglehole 1937;

Ford 2020) and ancestors must be honored in daily life and as part of community-wide ceremonies (

Parsons [1939] 1996). Efforts to negotiate these spiritual relationships permeate daily activity—religion, such as it is, is simply living the Puebloan way of life. This is true as well for many other Native American groups (

Lee 1951).

Many traditional North American groups conceptualize some animals as having spirits that are similar to or the same as a human soul (

Hallowell 1960) (e.g.,

Seowtewa 2022 reports that macaws are considered “society members” similar to humans among the Zuni of the American Southwest). Current and past Southwestern Native Americans also view certain objects as potent other-than-human beings. Shell trumpets and prayer sticks (ritual objects made from wood, feathers, clay, stone, and other materials) are considered animated beings by historic and modern Puebloan peoples (

Bunzel [1932] 1992, p. 485;

Mills and Ferguson 2008), and the Diné (Navajo) and Puebloan people ritually imbue their structures with spirits that protect and co-operate with the inhabitants to encourage social harmony and protection from harm and negative influences (

Mindeleff 1891;

Webster 2010). The Casas Grandes people also created

made beings (other-than-human beings that are at least in part manufactured by humans) for various purposes including shamanic rituals (

VanPool and VanPool 2023). In doing so, their practices again reflect similar patterns documented around the world.

3.1. Other-than-Human Beings: Macaws, Snakes, and the Horned-Plumed Serpent

VanPool and VanPool (

2007) have discussed the symbolic and conceptual importance of several animal species depicted in Casas Grandes effigies. Here, I focus my attention on four creatures: macaws and snakes, which are visible in the natural world, and horned-plumed serpents and double-headed macaw diamonds, which are liminal creatures that can be manifested in the natural world but are typically hidden from view for most people. Birds and snakes in general are often viewed as liminal creatures in shamanic worldviews because of their ability to transcend the middle world to interact with the upper world (birds) through flight or the lower world (snakes) given their capacity to burrow and swim in the Watery Underworld. While birds in general likely had significance within the Casas Grandes shamanic framework given their prevalence in Medio Period imagery (see

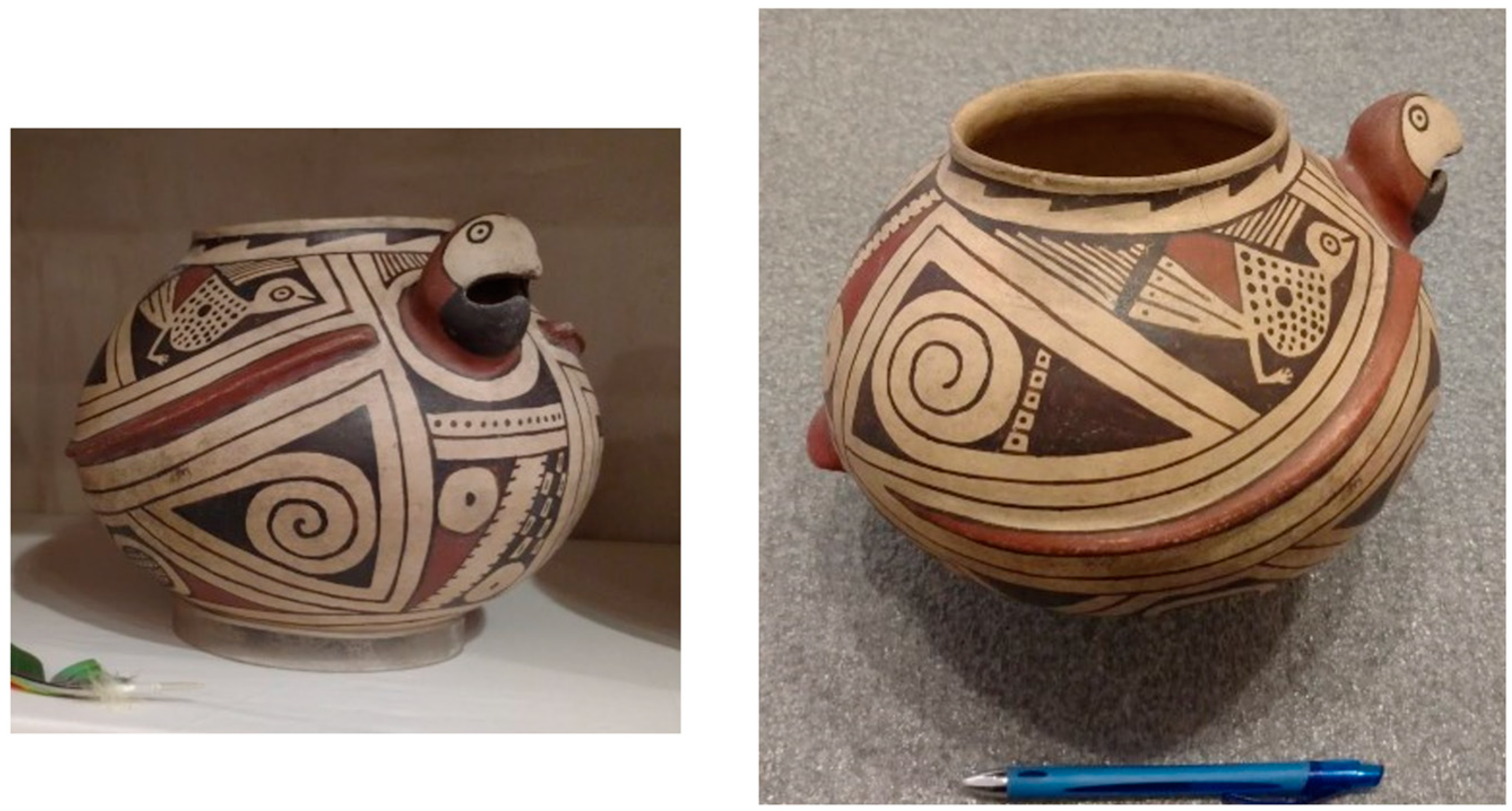

VanPool and VanPool 2007, p. 132), macaws seemed to hold special significance in Medio Period imagery and ritual practice. Macaws are also frequently depicted as effigies (

Figure 7 and

Figure 8); the double-headed macaw diamonds reflect a macaw-linked deity (

Figure 6), and over 300 macaws were found ritually sacrificed and placed in formal burials at Paquimé.

Di Peso et al. (

1974, vol. 8, p. 290) suggests that the feathers of both macaws and turkeys were used for ceremonial paraphernalia, and that the birds themselves were used as objects of sacrifice or as funeral offerings. Female pottery effigies are statistically more likely to be associated with macaws than are male effigies (

VanPool and VanPool 2007, p. 52), suggesting there may be a gendered component to macaw imagery, an association that also seems to be present in the preceding Mimbres period (AD 1000–1115) culture (

Munson 2000).

The idea of spinning and flight is often built into representations of macaws. The upward- and downward-looking macaw heads of the double-headed macaw diamond seem to reflect the concept of spinning and flipping. The Ramos Polychrome macaw effigy jar shown in

Figure 7 and

Figure 9 is formed so that the macaw head tilts upwards at a 45-degree angle with wings curling upwards from the tail to the head of the bird, giving the bird an upward trajectory as if flying. Both the actual macaw effigies and the double-headed macaw diamonds reflect shamanic traits, including entoptic designs, and, in the case of

Figure 7, wings that curve upward as spirals, and tutelary birds, which are primarily associated with shamans during their transcosmological travels and found on the chest of female effigies. Because the macaw is depicted in flight with tutelary birds on her shoulder, I suggest that the tutelary birds help guide the macaw during her soul flight, which is similar to the tutelary bird riding on the shaman’s leg in

Figure 5.

Casas Grandes shamans during their soul flights transformed into macaw-headed anthropomorphs. Given that both the macaws and tutelary birds are disproportionately associated with female effigies and that the male shamans directly adopt this feminine aspect during their transformation,

VanPool and VanPool (

2007) propose that Casas Grandes shamans are similar to other North American shamans who are considered Two-Spirits embodying both male and female spiritual aspects.

Figure 10 may directly reflect this association, in that the potter combined a macaw and human effigy (

Townsend 2005, Plate 120). Both the human face and macaw face look upward, and a zigzag ribbon band on the side of the effigy creates an upward symmetry, suggesting that the human/macaw effigy intentionally depicts the macaw–human flying upwards, which is indicative of shamanic soul flight. In many shamanic traditions from around the world, spirits are directly merged with the shaman’s own spirit by being permanently placed or fused in his/her body and/or spirit (

Eliade 1964, pp. 44–45;

Vitebsky 2001). It is plausible that macaw spirits were placed into the Casas Grandes initiates as they were trained to be shamans, which, in turn, would allow them to easily fly into other realms when necessary. Afterwards, the shaman’s spirit and identity would be replaced by a new identity that is no longer fully human (

Jokic 2008;

Vitebsky 2001).

While macaws travel between the middle and upper worlds, snakes travel between the lower and middle worlds. As with macaws, the idea of spinning is often built into representations of snakes in Casas Grandes iconography. For example, pottery snake effigies are typically portrayed as a pair or two pairs of snakes with bodies that wrap around the vessels and are angled towards the vessels’ mouths (e.g.,

Figure 11). The snakes are generally molded forms created by pushing the snake body and head out from the body of the vessel when the clay was in a plastic state. The coloration and other decoration of the snakes in

Figure 11 indicate that two are rattlesnakes and two are Sonoran Mountain Kingsnakes (

VanPool and VanPool 2007, pp. 87–90). The bodies spiral around the olla as if they are coming up out of the lower world. The heads sit above the body of the jar and the mouths are sometimes open as if they are speaking into the center of the jar.

VanPool and VanPool (

2007, p. 93) have suggested that Casas Grandes people asked snakes to deliver their prayers to the spirits of the lower world in a manner similar to historic and modern Southwestern Native Americans such as the Hopi of Arizona. Like the macaw effigies, these snakes were deliberately formed around the vessel, making the jar itself a portal, again emphasizing the likelihood that snakes were liminal creatures associated with the lower world.

As we see in

Figure 9, macaws were merged with snakes to form a composite creature that does not correspond to any known animal species. These feathered serpents are common across the New World and are viewed as liminal beings that can span all three layers of the cosmos (lower world to upper world) (

VanPool and VanPool 2007, pp. 118–21; see also

Furst 1998;

Whitley 2001). As will be emphasized further below, note that the macaw-headed serpent is also circling around the jar with an upward ascent on the olla. These macaw–serpents are more typically reflected in Casas Grandes Medio Period iconography as horned-plumed serpents, with a serpent head embellished with a forward-pointing horn and plumes. Casas Grandes shamans are depicted wearing horned-plumed serpent headdresses (

Figure 5) and actively interacting with horned-plumed serpents (

Figure 5). Male effigies are more commonly associated with horned-plumed serpents and serpent imagery in general, suggesting serpents, including horned-plumed serpents, have a masculine association (

VanPool and VanPool 2007, pp. 52–53) that, in some way, parallels the association between females and birds.

3.2. Other-than-Human Beings: Pots as Made Beings

Southwestern Native Americans often consider pots to be living entities imbued with a spiritual essence created in collaboration with the clay, the fire, and the additional other-than-human beings involved in pottery production (

Cushing 1886, pp. 510–15;

Trimble 2004).

VanPool and Newsome (

2012) argue this was also the case for the Medio Period Casas Grandes people. Pots as other-than-human beings (i.e., as pot-persons) served at least two roles, in my view. First, they worked as partners with humans to achieve important goals and to maintain life in the challenging Chihuahuan desert. This included the utilitarian tasks of cooking and storage, but also included facilitating interaction across the Medio Period shamanic universe. For example, a Playas Red jar decorated with the same sort of jewelry associated with humans was filled with shell, stone, and a bovine horn, and then placed at the bottom of Reservoir 2, the main water source for Paquimé. This was an intentional effort to use the animacy of the jar to activate (bring alive) the reservoir so that it, too, would work with humans to provide the water that was necessary for the community (

VanPool and Newsome 2012). The placement of the Playas Red pot-person in a vault under the reservoir was likely accompanied by ritual dedication and activities including singing and chanting as the reservoir was animated during the construction process (

VanPool and VanPool 2023). Thus, the Playas Red pot-person reflected multiple instances of being animate at various scales: it is itself a made being created in the form of a water-focused bundle, that was then used as an anchor and ally during the creation of another made being in the form of Reservoir 2, and, subsequently, as a focus of interaction between humans and the Watery Underworld and its denizens.

Second, made beings, including pottery, could have a special role in shamanic ritual, acting as an aid and partner as the shamans traveled during soul flight and as a means of recording the results of their travel. This is the use I have suggested implicitly at this point and will now explicitly focus on in this analysis. Many shamans suggest that most people have “spirit blindness” that is analogous to color blindness, in that the spirit-blind cannot see the spirits that are readily visible to shamans (

King 1999, p. 58;

Vitebsky 2001). To help communicate with the spirit-blind, shamans frequently materialize the hidden part of the physical world as well as the upper and lower worlds that most people cannot regularly access (

Halifax 1982;

Harrison-Buck and Freidel 2021;

Wallis and Carocci 2021). Shamanic drawings, paintings, or pecking in rock walls are, thus, more akin to a photograph of a place one visited in the past, as opposed to creative endeavors based on fanciful imagination showing unreal worlds (

Halifax 1982). As such, the images also provide doorways and maps of the spirit world and illustrate the other-than-human beings that reside there (

Halifax 1982, pp. 66–71). They, consequently, enable shamans to have some control over the powerful forces with which they interacted (

Halifax 1982, p. 11). In other words, shamanic images painted on their regalia, drums, rock art, pottery, blankets, rattles and so forth portray the underlying reality of the world that is generally hidden, and, in doing so, make these realms understandable, accessible, and controllable. For example, shamans’ regalia often contain some form of a map of the cosmos with spirits painted in the appropriate realms (

Halifax 1982). This representation anchors the shaman to the middle world and lets him/her travel across the realms with a certain level of confidence in the shaman’s ability to return home. An incorrectly drawn map would lead the shaman astray, causing his or her spirit to get lost in the spirit world, which would be catastrophic for the individual (leading to physical death, at best) and potentially for the client/community.

Ritual objects may transcend just being (largely passive) “maps” or “recordings” and instead become active participants in shaman journeys. For example, among the Altai hunters and gatherers of the Altai Mountains of central Asia, the shaman’s drum is animated, and becomes the animal used to make the leather drumhead (typically horse), or a “boat” or other container that actively carries the shaman’s spirit, lost souls the shaman encounters, and the tools the shaman needs to cross the cosmos while in soul flight (

Potapov 1999). The drum is, thus, a central, active partner in shamanic soul flight. The use of imagery and decorated objects as active shamanic agents to help successfully navigate between realms is cross-culturally common. Shamans work to ensure their other-than-human helpers properly reflect the correct ritual key and correct spirit door, and otherwise have the attributes to ensure the shaman’s success (

Goodman 1988,

1990;

Halifax 1982;

Laughlin 2004). Of course, the use of pots as other-than-human partners in the middle world (e.g., the Playas Red jar animating the reservoir) and as transitory aids in shamanic ritual (e.g., the Polychrome pots with depictions of the spirit world) is not mutually exclusive, given that the same pot could serve different functions in different contexts, just as shamans do.

4. The Magic of the Spinning Pot

VanPool and VanPool (

2023) discuss the links between the creation of pot-persons and Medio Period shamanic transformation. Here, I suggest that some Casas Grandes pots were linked to the trance states and that they had a magical framework underlying their forms and roles. Humans created pot-persons in collaboration with other-than-human beings to have specific characteristics that make the pot-persons useful for their specific roles. To state this more forcefully, pot-persons (and other made beings) are not just a class of objects that are functionally equivalent but are, instead, unique individuals that may have profound differences among themselves (see also

Zedeño 2008,

2009). They are, consequently, like humans with distinct personalities, animating agencies, capabilities, and needs. The spiraling and swirling designs on some Casas Grandes Polychromes and some Playas Red effigies are repeated commonly enough and with enough care to demonstrate they are intentionally designed to fit into shamanic practices.

VanPool and VanPool (

2007) suggest that Casas Grandes potters realistically portrayed spiritual principles and creatures in Medio Period iconography. The repeated characteristics of these pot-persons, thus, necessarily reflect the essential characteristics for these individual pots to serve as people with their specific roles in Medio Period shamanism. As other-than-human

individuals, they would be

individually imbued with the characteristics needed for them to succeed as

individual made beings.

The process of creating and using the pot-persons fits within the framework anthropologists call magic, which is defined as efforts to manipulate hidden forces (

Greenwood [2009] 2020). As illustrated by Western concepts such as lucky horseshoes or rabbits’ feet, objects are often central to magical efforts. Examples of the magical use of other-than-human persons include guardian spirits that help influence unseen forces to enrich/extend a person’s life and/or to provide resources such as clothes or horses.

Benedict (

1923, p. 11) reports that:

The animals and things which might become guardian spirits were almost limitless, including the weather, dwarfs, the nipple of a gun, horseflies, kettles, and objects referring to death. But very nearly all the natural phenomena of the world were distinctive as guardian spirits of one or other profession. Shamans, warriors, fishermen, hunters, and gamblers each had their recognizable guardians.

Parsons (

[1939] 1996) noted that magical rituals involving fetishes among Pueblo people always have their own internal logic; that is, they make sense in terms of basic cultural relationships. In her words:

In logical order we may consider the ritual of making offerings or giving pay to the Spirits; the fetishes and representations of the Spirits; those images or effigies which the Spirit invest when properly invoked, and which convey power or title, the assemblage of fetishes and other sacrosanct things to form an altar; mimetic weather or crop ritual, including running and dancing and throwing gifts, rites which express with peculiar vividness the feeling or ideation of mimetic magic [a synonym for sympathetic magic], of performing in little or representatively as a form of compulsive magic what is desired on a large scale; and finally purificatory ritual to prepare for or to conclude ceremonial, cleansing for or after contact with sacrosanct and dangerous things.

The Playas Red pot-person associated with Reservoir 2 at Paquimé is likely a form of a guardian spirit for the entire community that served as an intermediary between the Casas Grandes people, terrestrial spirits, and spirits of the Watery Underworld. It also engaged in mimetic magic for cleansing water and dealing with the dangers of the Watery Underworld. Likewise,

Mueller et al. (

2024) identify the roles that stone effigies, especially of bears (powerful spirits associated with strength and healing) and mountain lions (powerful spirits associated with hunting), play as guardian spirits during the Medio Period. Here, I suggest that specific pot-persons were formed as guardian spirits associated with shamanism. I explore two lines of evidence to illustrate their structure and use.

4.1. Effigies and Sympathetic/Mimetic Magic

First, I will discuss effigies of serpents and macaws as they relate to magic. As documented by

VanPool and VanPool (

2007), many different animals are reflected in effigy on Medio Period pottery, but birds and serpents are by far the most common. And, of these, rattlesnakes, coral snakes, and the similarly colored Sonoran Mountain Kingsnakes, and macaws are most frequently depicted. As argued above, snakes and birds are liminal creatures tied to the upper and lower worlds, and the central deities of the horned-plumed serpent and double-headed macaw diamond have deep significance in Medio Period cosmology and transcend the middle world. Here, I suggest that the bird and snake effigies shared this special link of transcending the boundaries of the physical world through the process of sympathetic or mimetic magic.

Sympathetic magic is cross-culturally common and central to magical practices in most cultures (

Hong 2022). Sympathetic magic rests on two propositions: (1) similarity magic—that “like attracts like” such that the abilities or attributes of one type of “thing” (however defined) can be transmitted to another based on shared similarities; and/or (2) contagion magic—that contact between two or more “things” (however defined) can transmit a state or character between them even when they are no longer in contact. Examples of contagion magic include the link between inadvertently stepping on the tracks of a bear or other powerful predator and Bear Sickness, a spiritual ailment that causes illness and even death among many Native Americans (

Hooper 2014;

Singh 2021). Here, the animal’s footprint retains spiritual potency that can be transmitted to humans through contact. Undoubtedly, there are cases of contagion-based sympathetic magic during the Medio Period, but my focus is on sympathetic magic based on shared similarities. Examples of this type of magic include that of the Aztec priests of Mesoamerica that held the tears of child sacrifices and their mothers could attract the tears of Tlaloc (the rain god) that fell as rain (

James 2002, p. 337), the Tohono O’Odham of the North American Southwest that held that drinking saguaro wine to the point of vomiting would cause the rain clouds to vomit rain (

Waddell 1976), and the San of southern Africa that held that dipping a person in water and letting the water drip into reed mats would bring rain that would drip across the land (

Prins 1990).

Mimetic magic is also found cross-culturally and researchers such as

Bubandt and Willerslev (

2015) suggest that it should be paired with sympathetic magic. Mimetic magic is based on mimicry, which means copying something, but also copying the behavior of something (e.g., Plains hunters that dress in wolf furs become wolves that stalk bison (

Catlin 2003, pp. 67–68)). I propose here that magical artifacts are not just a copy of the thing or person. Instead, the shaman or magician imbue the object with the feelings, thoughts, and cognitive abilities of the other-than-human person that they want the object to replicate. As made beings, artifacts can be active as other-than-human persons (

VanPool and VanPool 2023). Thus, while agreeing with

Bubandt and Willerslev (

2015) that sympathetic magic should be paired with mimetic magic, we need to consider adding an additional conceptual ingredient that includes adding an animating soul/spirit in the image or object in some cases. Magical images’ and objects’ power reside in “like attracts like”, “like acts like”, “like thinks like”, and “like has spirit of like”. Thus, magical objects are multifaceted and can be manipulated at the physical, social, emotional, and spiritual levels, often all at once. Shamans, magicians, and others are then able to make changes in both the made being and the associated other-than human persons.

In the case of the Medio Period effigies, the shared similarities between the effigies and the animals they represent provide the pot-person with the characteristics of the referenced animal. Just as snakes and birds are liminal creatures that can transcend the boundaries of the physical world, so are pots formed in their shape. Likewise, the portrayal of aspects of the spirit world (e.g., entoptic imagery and deities such as the horned-plumed serpent) on a pot necessarily create a link between that pot and the corresponding aspects of the spirit world. By portraying the animal or place, that specific pot-person itself would have special and unambiguous links and capabilities not generally shared among other pot-persons and even among other animals or humans. Thus, the effigies and decorated vessels serve as special, and, in some cases, possibly even unique, links within the Medio Period shamanic universe (e.g.,

Figure 6) that are useful to shamans as they navigated between the worlds.

4.2. Spinning and ASC

As mentioned above, many pots, including bird and macaw effigies and other pots with shamanic imagery, symbolically reflect spinning that may be related to vortexes experienced during shamanic flight.

Figure 12 depicts a Playas Red Rubbed Corrugated macaw effigy. The texturing on this vessel is deliberately formed to make a spiral and net-like structure at the same time. It is reminiscent of the blue lattice vortex previously shown in

Figure 2. The Playas Red pot was first coiled and lightly smoothed. Afterwards, a tool was used to stamp in the corrugated designs that were then lightly polished over. The stamped designs, thus, run diagonally across the pot’s coils, demonstrating that the potter intentionally created swirling designs. This is clearly seen when looking into the jar; the forming coils are visible on the interior, running parallel to the base, but the exterior has the spiraling designs that cross the coils. I further note that painted icons (which are typically of shamans or related animals/deities) and the aforementioned bird and snake effigies are designed to indicate spinning. For example, the snakes in

Figure 9 and

Figure 11 and the dancing humans in

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 are painted on the pottery with their heads to the right of their bodies, making them appear to move counterclockwise if one spins the vessels such that the heads lead the motion on the pot.

The vessels in

Figure 12 and

Figure 13 have use-wear on their bottoms, showing that the jars were mechanically spun. Spinning pots as part of ritual activity may be a long-lived practice in the Casas Grandes region and the larger Mogollon tradition (which includes the Casas Grandes tradition).

Whittlesey (

2014) argues that Mimbres Classic Black-on-white bowls decorated with geometric designs were spun using a manual turntable to produce subjective color (i.e., the spinning of black and white images causes colors to be perceived).

Whittlesey (

2014, pp. 61–62) suggests this practice may have been related to the trance states as part of shamanic rain-making ceremonies (see also

VanPool and VanPool 2007). These black and white bowls and the potters who made them date to the Mimbres Classic period (AD 1000 to 1115) of southern New Mexico and northern Chihuahua, which precedes and is historically and genetically related to the Medio Period tradition (

Morales-Arce et al. 2017;

Moulard 2005). Spinning using a turntable will not leave clear use-wear indications, but the direct evidence of the intentional spinning on at least some Medio Period effigies is reflected by use-wear. Given the symbolic evidence of rotating and the use of ritual spinning in the preceding Mimbres Classic Period, I suspect that spinning these effigies was a common practice during the Medio Period. I have not yet completed my analyses of Medio Period pottery to see if subjective color is created when they are spun, but the presence of geometric designs indicates it is possible (and even likely).

I suggest then that pots with icons (e.g., horned-plumed serpents and dancing shamans) were spun as people told stories that corresponded with the jar, and that the spinning is directly designed to be part of the ASC process the pot-persons would undergo during shamanic ceremonies. These are not mutually exclusive uses, in that the pot-persons would simultaneously embody the spirit world by making it visible in this world but would also be linked to the spirit world beyond the physical world. However, just like with human shamans, there would have to be a process that would allow the pot-person to engage with the spirit world. Again, based on sympathetic/mimetic magic, this transformation would follow a similar pattern to that which humans undergo, which would include the initiation of ASCs and the creation of a vortex corresponding to a sense of vertigo. This is even more clearly shown in a Playas Red incised human effigy with an upturned face and a facial expression indicative of ecstatic trance (

Figure 13). His whole body is spiraling as if undergoing transcosmological travel. The decorations on the pot-persons and their spinning, thus, were how they could undergo the ASC process necessary for soul flight, even as the shamans were undergoing their own form of this journey.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Cognitive archaeologists and other cognitive scientists have documented the ways human cognition impacts our view of the world, including our tendency to impart human-like characteristics onto other aspects of the world (

Birch et al. 2022;

Currie and Killin 2019;

Harrison-Buck and Freidel 2021;

Hortensius et al. 2021;

Laland and Seed 2021). Humans often rely on “natural models” in which aspects of the world are drawn together through analogy (

Whitley 2001,

2020)—tobacco’s utility as an insecticide and cleansing agent against pests in the physical world corresponds to its ability to purify places and people of unwanted spiritual pests, snakes shedding their skin reflects their potential and focus for renewal and rebirth, and caves serve as obvious entry points into the lower world, for example. Sympathetic and mimetic magic largely rests on these sorts of naturalist relationships. Shamanism and the link between particular birds and specific snakes as liminal creatures are likewise easily understood as naturalist models within a cognitive approach. Snakes can move underground and in water while birds can fly high through the air, giving these creatures straightforward relationships to the lower and upper world that are recognized by cultures around the world including during the Casas Grandes Medio Period. Medio Period shamans worked these creatures into their cosmological framework. Given the natural tendency of some birds to fly upwards and/or downwards in spirals sometimes, and snakes to coil and move in serpentine patterns, their very behavior would naturally be identified by shamans as correlating with the vertigo and spinning the shamans experienced during their soul flights. This association among shamans, birds, serpents, the spirit world, ASC, and soul flight, in turn, served as a natural model for tools used during shamanic activities.

Wallace (

1966, p. 102) notes that rituals are how a religion accomplishes what it sets out to do. In societies with animistic ontologies, the physical and spirit worlds are interwoven, such that physical objects and phenomena have inherent spiritual agencies that are not easily separated from the physical itself. The spirit of animate objects and other-than-human persons define and determine the physical manifestations of the being even as the physical components characterize the spiritual aspects. In other words, the physical and the spiritual are intertwined so that a physical action to the other-than human person (e.g., a pot-person) affects his or her spirit, and a spiritual action impacts the physical. As a result, animated objects are central to shamanic rituals, ranging from spiritually potent plant medicines to drums, rattles, and ceremonial accoutrements (e.g., blankets or containers), which are made beings.

Soul flights are dangerous, so they must be completed with the proper respect and preparation to facilitate positive interactions with the powerful spirits and forces the shaman and his or her helpers encounter. Central to this process is magic, which is present in all societies, but is an essential component of shamanic practice given the shaman’s efforts to interact with and manipulate unseen forces in the cosmos (lower, middle, and upper worlds). Shamans’ drums, crystals, tutelary animals, and plants, and, in the case of the Medio Period, pot-persons allow them to interact with hidden beings and forces during their ecstatic trances as they look for lost souls or objects, battle witches and attack enemies, plead or bargain for rain and other resources, or seek assistance to heal and aid themselves and their clients.

In this paper, I contend that pot-persons held an important role as animated shamanic helpers during the Medio Period and were directly involved in the ASC experiences of soul flight central to the shamanic practices. Some pot-persons helped physically manifest the spirit world in the physical world of the Medio Period people to record its existence, form, and influence on the middle world. This provided the Medio Period shamans with made beings that helped focus their efforts to reach other realms of the Medio Period shamanic universe while the pot-persons travelled with and anchored the shamans to this world, thereby ensuring their safety. Their ability to represent and navigate the spirit world likely helped reinforce the authority of the shamans who could see and experience the spiritual dimension of this world (i.e., middle world) and the lower and upper worlds in ways beyond what was typical for most “spirit-blind” people. However, many pot-persons seemed to serve an active role in shamanic ritual, likely becoming shamans in their own right and undergoing their own shamanic transformations that held significant similarities to their human counterparts. Using their own form of sympathetic/mimetic magic, human shamans either commissioned or directly manufactured pots that emphasized the central aspects of Medio Period soul flight. Pottery effigies of snakes and macaws shared the liminal status as they were natural links, complete with their animal counterpart’s morphology, behaviors, and souls, to the upper and lower worlds. Their placement on the vessels emphasized the entoptic images and spinning that were central to the tobacco-based ASC experiences that included intense feelings of vertigo and flying during the initial stages of soul flight.