2. Introduction

In his seminal study of the Old Man in Maya religion, Simon Martin advances the notion of theosynthesis, the “pictorial convergence of a deity with some other deity, creature, object, or material” (

Martin 2015, p. 210). While he claims this neologism as descriptive rather than analytical, he proceeds to review the many substantive cases of such convergence not only in Mesoamerican thought and depiction but also in other ancient religions, such as that of Egypt. The case for theosynthesis is affirmed by generations of anthropological and archaeological study of Maya beliefs (

Tedlock 1982;

Vogt 1976), as he notes, and in his work, it is convincingly illuminated in the case of the Old Man, Itzam. A small black stone unprovenanced Middle Preclassic (900–350 BCE) figure of a bearded old man in the collection of the Dallas Museum of Art is probably this primordial creator (

Freidel 1996,

2017;

Freidel and Reilly 2010). This essay proposes that it depicts an old woman/man, a pervasive contemporary Maya trope for ancestor but here a figural form, giving birth from his vagina to his penis. In Martin’s terms, it is the “whole” person who engenders the universe, and if it is indeed authentic, and experts Kent Reilly who made the original publication of it possible and

Karl Taube (

[2004] 2020) affirm this judgement, it is the earliest known depiction of Itzam, the creator.

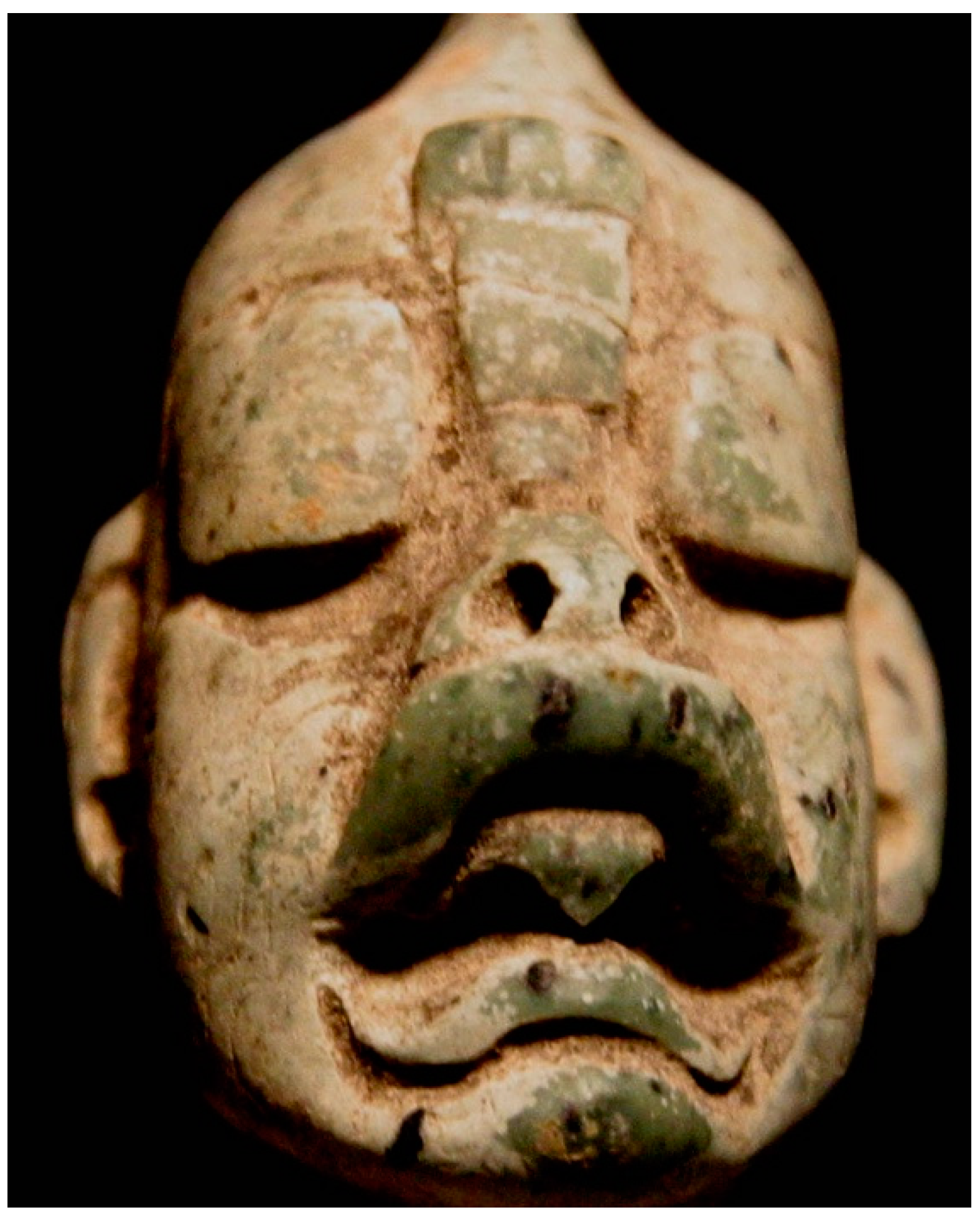

The Dallas Old WomanMan (

Figure 1) expresses an original, pervasive, and enduring focus in Mesoamerican cosmology and symbolism on the creators as not just a pair of old magicians and diviners, but as a singularity expressing the capacity for sexual engendering.

Carolyn Tate (

2012) has explored extensively the focus of this understanding in the emergence of Olmec religion and, anchoring into

Kent Reilly’s (

1994) convincing assertion and iconographic exegesis that Olmec people articulated a vision based on careful observation of nature, she argues that male and female genetalia, the sexual ambiguity of the human fetus until late in gestation, and engendering were pervasive and central themes in Olmec cosmology. She says:

“Formative Mesoamerican visual culture may be the first to explore so thoroughly a ‘macrobiology.’ Not only were people looking at and thinking about conception and gestation, but they related these processes to much larger ones—to agricultural cycles, to specific configurations of the landscape that seemed especially potent, and to celestial cycles… The earliest answers to such questions were grounded in people’s empirical observations of a world in perpetual flux. What is life, and how do humans share that quality with the rest of the shifting world? They wondered about the relationships between humans and other creatures”.

The Dallas figure was created in the context of ambient Mesoamerican Olmec religion if not by an Olmec craftsperson of the Gulf Coast. The idea of engendering as a way of understanding the ontological relationship between mindful and sentient persons, be they human, animal, divine, or other animate things, is a focus of the Classic Maya, and later Maya, in the diphrastic kenning Ch’ab’ Ak’baal (or

chab akab’), “generation and darkness” (

Knowlton 2002,

2010;

Stuart 2005b,

2021;

Harrison-Buck 2021;

Martin 2020). In this essay I will argue that this idea, act, and incantation were central to Mesoamerican thought long before the Classic Maya, and that, commensurate with Tate’s theses regarding Olmec religion, engendering was a primary focus of the materialization of power through what Harrison-Buck (

Harrison-Buck 2018;

Harrison-Buck and Freidel 2021) terms relational ontology, the co-creation of the world through attentive and affective engagement. It is traditional among her cohort of like-minded scholars to reiterate the burgeoning literature of the last several decades on this way of thinking about things and one refers readers to her recent synthesis (

Harrison-Buck 2018) for a detailed and clear summary of that literature. This essay anchors directly into material symbol systems. With deference and respect for those experts in theory, one turns to the subject at hand.

3. The Birthing Pose

The finely carved Old WomanMan depicts a squatting and grimacing old person arching his back while he draws his legs up with his hands. This pose is a variant of a birthing pose, often depicted in Mesoamerica with the legs splayed to release the child as in an unprovenienced Classic Maya scene of the Moon Goddess giving birth to the rabbit. The Maya, like peoples elsewhere, see in moon shadows (

Justin 2023).

Peter David Joralemon (

1974, Figure 12), in his study of penitential genital bloodletting, discussed an unprovenienced vase from Huehuetenango, Guatemala, which shows men in this birthing pose using animate triple-knotted ritual bloodletters. The overlap of engendering, birth, and auto-sacrifice is an important theme (

Harrison-Buck 2021) discussed below. Finally, there is an unprovenienced Olmec style greenstone figurine in the Dumbarton Oaks Library and discussed by

Karl Taube (

[2004] 2020, entry 17 Dumbarton Oaks Figure PC B 018) that displays the same pose as the Dallas figurine. This jadeite and albite figure shows, like the Dallas figure, a bearded and grimacing man crouching with his legs drawn up. He wears the trefoil maize sprout of rulership, as identified by

Virginia Fields (

1989), on top of his head and his crown is the Feathered Mirror, a major magical portal from Olmec symbolism onwards, as identified by

Kent Reilly (

1994, Freidel in prep.).

Taube (

[2004] 2020, Figure 17.12) identifies this crouching pose as an early version of the pose of the Old Fire God (Huehueteotl among the Aztecs) particularly prominent in the art of Early Classic Teotihuacan but found in the Gulf Coast lowlands and elsewhere. He proposes that the Dallas figure is another very early example of this deity and illustrates other unprovenanced examples.

The most famous of these figures in his Figure 17.2 (

Taube [2004] 2020), with the Kan Cross marked vessel as a headdress, is also bearded. The Fire Gods of Teotihuacan are regularly depicted as old and wrinkled like the Dallas figure. Several of the comparative figures illustrated by

Taube (

[2004] 2020) in his discussion of the Dumbarton Oaks greenstone figure also have the hands grasping legs pose. Generally, the Fire God images are crouching and grimacing old men, but they are usually depicted with crossed legs and not with the splayed legs of the birthing pose. Again,

Taube (

[2004] 2020) provides examples with the splayed-legs pose, including one with a disc suggesting the bowl of the Old Fire God. There may well be the connection Taube draws between the Classic Huehueteotl and the deity portrayed on the Dallas and Dumbarton Oaks figures, but the fact that there are at least two Middle Preclassic figures in the birthing pose, and possibly more, is significant in appraising authenticity of the unprovenanced Dallas figure. A Late Preclassic wrinkle-faced Old Man may be depicted on a stucco façade at Holmul according to

Martin (

2015, Figure 26, Holmul Group II Str. B-1st mask) positioned in the maw of a jaguar mountain mask. The recently discovered Late Preclassic God mask discovered at Ucanha in Northern Yucatan (

Olvera et al. 2019) and being drafted and studied by Jacob Welch looks like it could be a bearded Old Man with three typical jewels in his beard. So, the Old Man is evidently present in that era of the Maya world.

The Dumbarton Oaks figure described above, in contrast to the Dallas figure, lacks genitalia. This is unsurprising in that the majority of presumably male figures in the known Olmec corpus, including the famous La Venta Cache 4 (

Drucker et al. 1959, Plates 33-3) figures in good archaeological context, have sketched celtiform loin clothes, floating celts over the groin, or lack obvious male genitalia. Several of the La Venta Cache 4 figures could be read as having female genitalia as seen in the Heizer record photographs in the Smithsonian Museum collections (see

Tate 2012 on identifying such Olmec figures as female).

The Olmec transformation figure in the Princeton Museum (

Reilly 1990, Figure 1) is a bearded man in a variant of the splayed pose, with no genitals. In Reilly’s discussion of this and related figures, this individual is undergoing magical transformation into a jaguar. That is to say, he is a shaman, sorcerer, or magician like Itzam. This lack of genitals is clearly a deliberate and pervasive depiction of important men in the Middle Preclassic or Formative period.

4. The Dallas Figure’s Genitalia

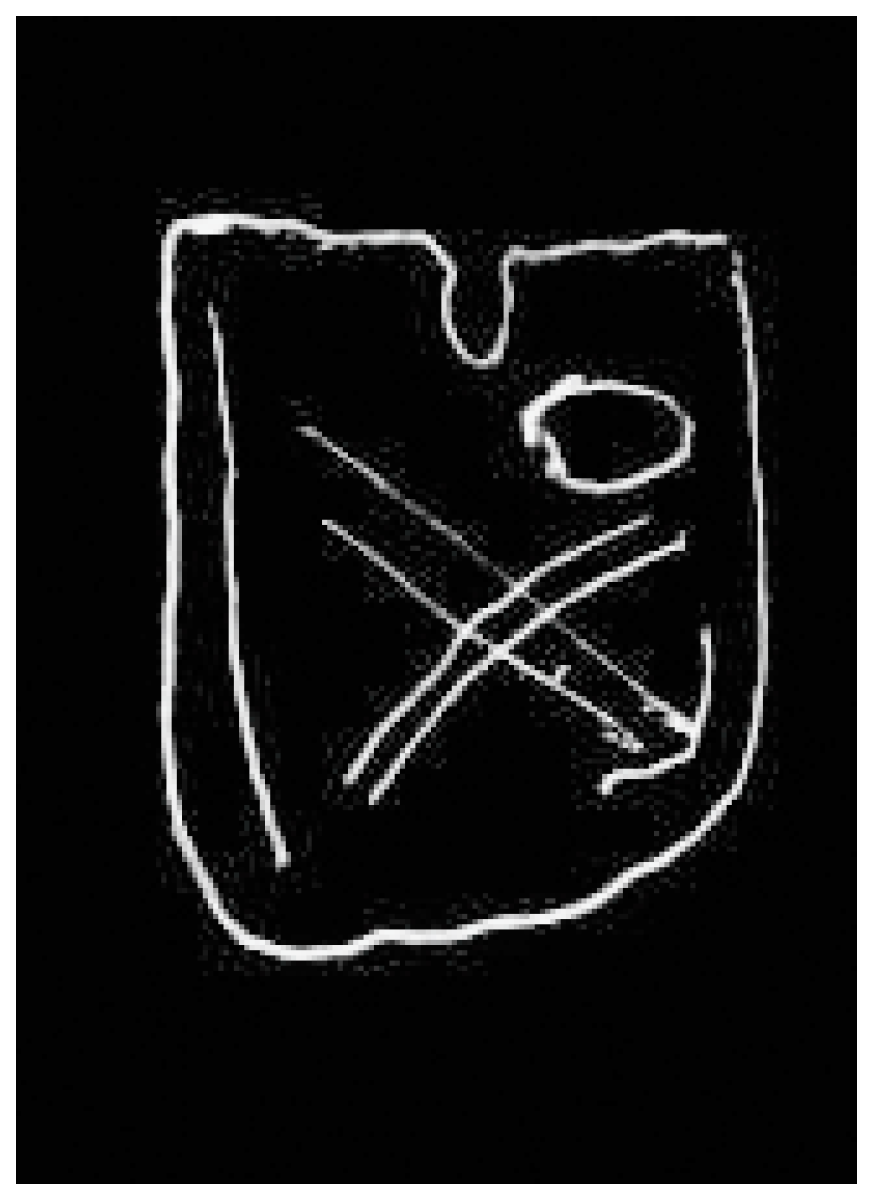

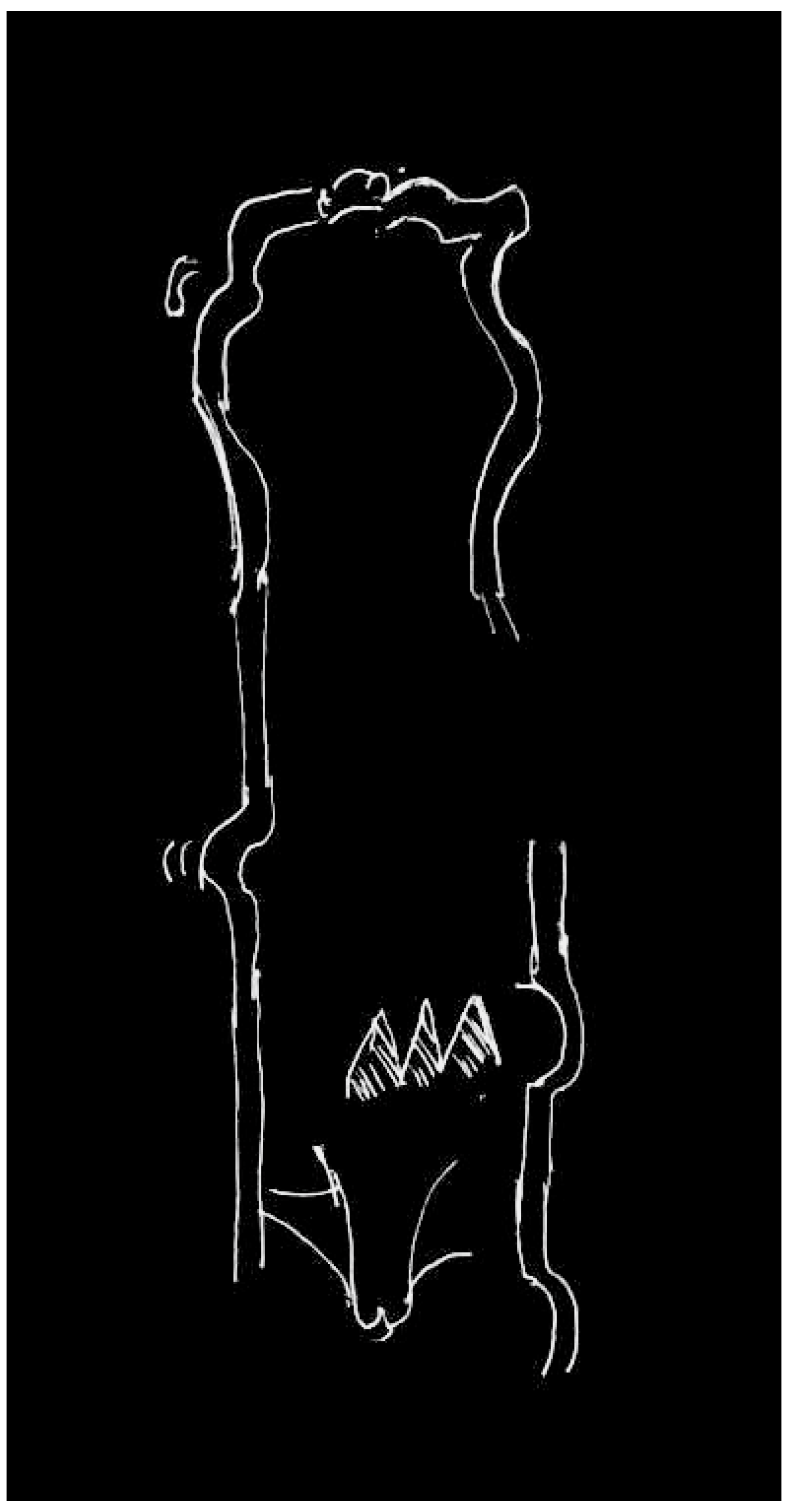

The explicit and detailed male genitalia on the Dallas figure (

Figure 2) was what first brought attention to it in light of the rarity of Olmec or Middle Formative figures with genitalia. The circumcised penis, glans defined by lighter incised lines observable against the darker shaft, is delineated by a wide excised groove on three sides that is explicitly pointed at the bottom, suggesting that it is a vagina. In personal communication, curator

Michelle Rich (

2023, February 5) suggests that this v-shaped carving might depict semen. The Middle Preclassic depiction of falling raindrops is, in the Chalcatzingo mountain wall bas-reliefs in Morelos, highland Mexico, for example (

Grove 1987), an exclamation point that closely resembles the circumcised penis of this figure, so liquid is conceptually implicated. However, here liquid is not the v-shaped excision but rather what it frames: the penis. The grooving flares at the top on both sides extend in two incised horizontal lines across a triangular raised dark surface identifiable as a clitoris (

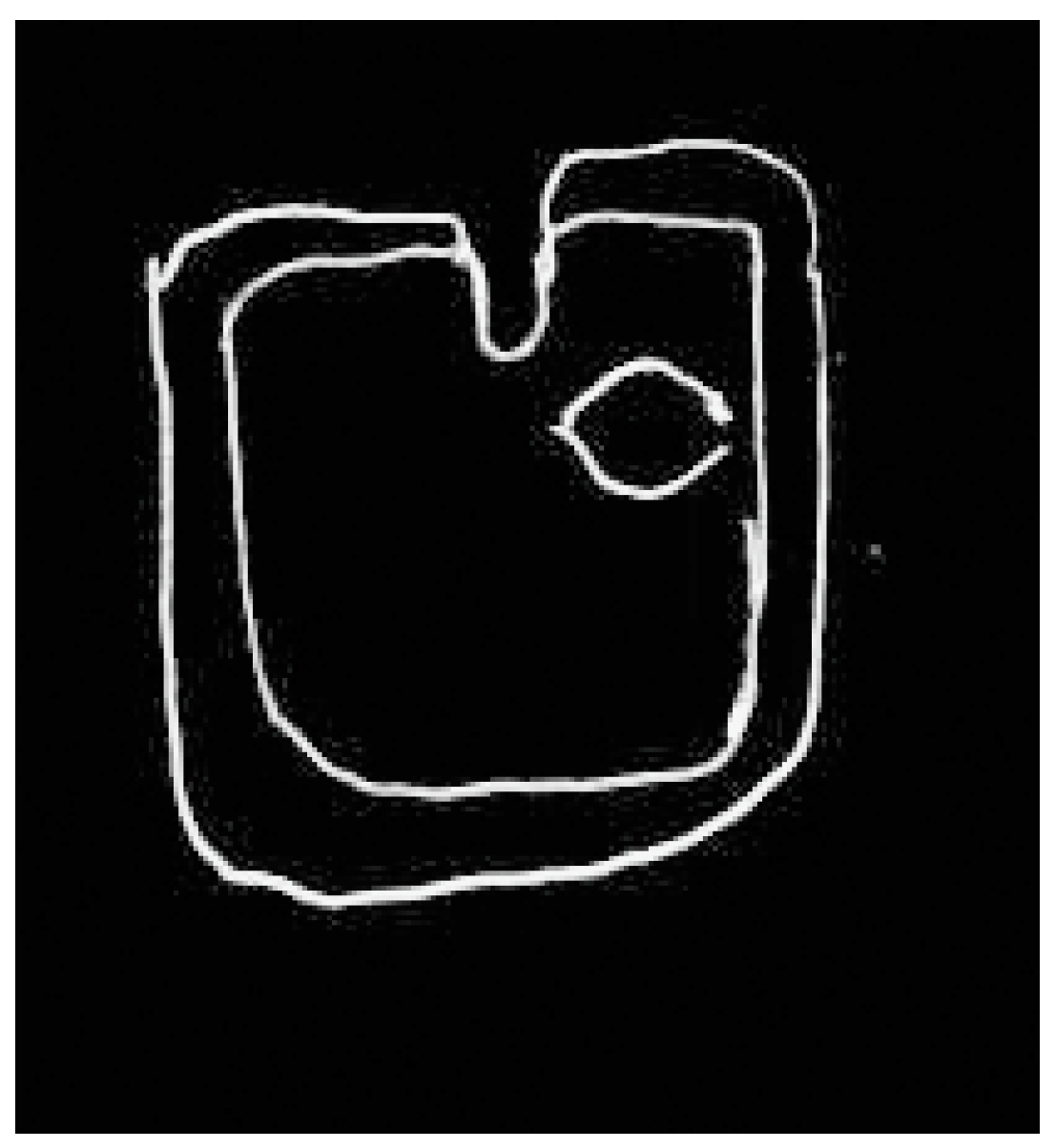

Freidel 1996). The vulva is not only shaped around the penis emerging from it but also distinguished by raised shaping of the mons pubis distinguishing it from the scrotum below it (

Figure 3).

The Dallas figure is of the same masterful quality of carving as found in the case of many other Middle Preclassic Olmec era lapidary works. This shaping of the vulva and the distinguishing of the mons pubis from the scrotum is deliberate and defined, as is the delineation of the scrotum with incised lining around it. Careful observation of the buttocks of the figure, discernable in

Figure 3, reveals an incised circle on each one. Together, the scrotum and the two incised circles form a triangle.

Kent Reilly (

1994) identifies three circles forming a triangle in Olmec symbolism as the cosmic hearth, seen twice, for example, on the famous Humboldt Axe (

Freidel and Reilly 2010, Figure 17). The three stones of the hearth are also depicted as an in-line triad in the opened bundle arrangement (

Reilly 1994;

Freidel and Reilly 2010, Figures 10 and 14;

Rich 2023, plate 32, p. 96), seen on the Creation Plaque in the Dallas Museum).

One returns to these two elaborately incised pictographic “reading” stones below as both reference the creation of the universe like the Dallas figure. The distinguishing of the vulva and mons pubis from the scrotum, and the incised delineating of the scrotum as a “stone” in the triangular cosmic hearth, signal that this birthing is taking place in the context of creation (

Freidel et al. 1993). Further affirming this suggestion (

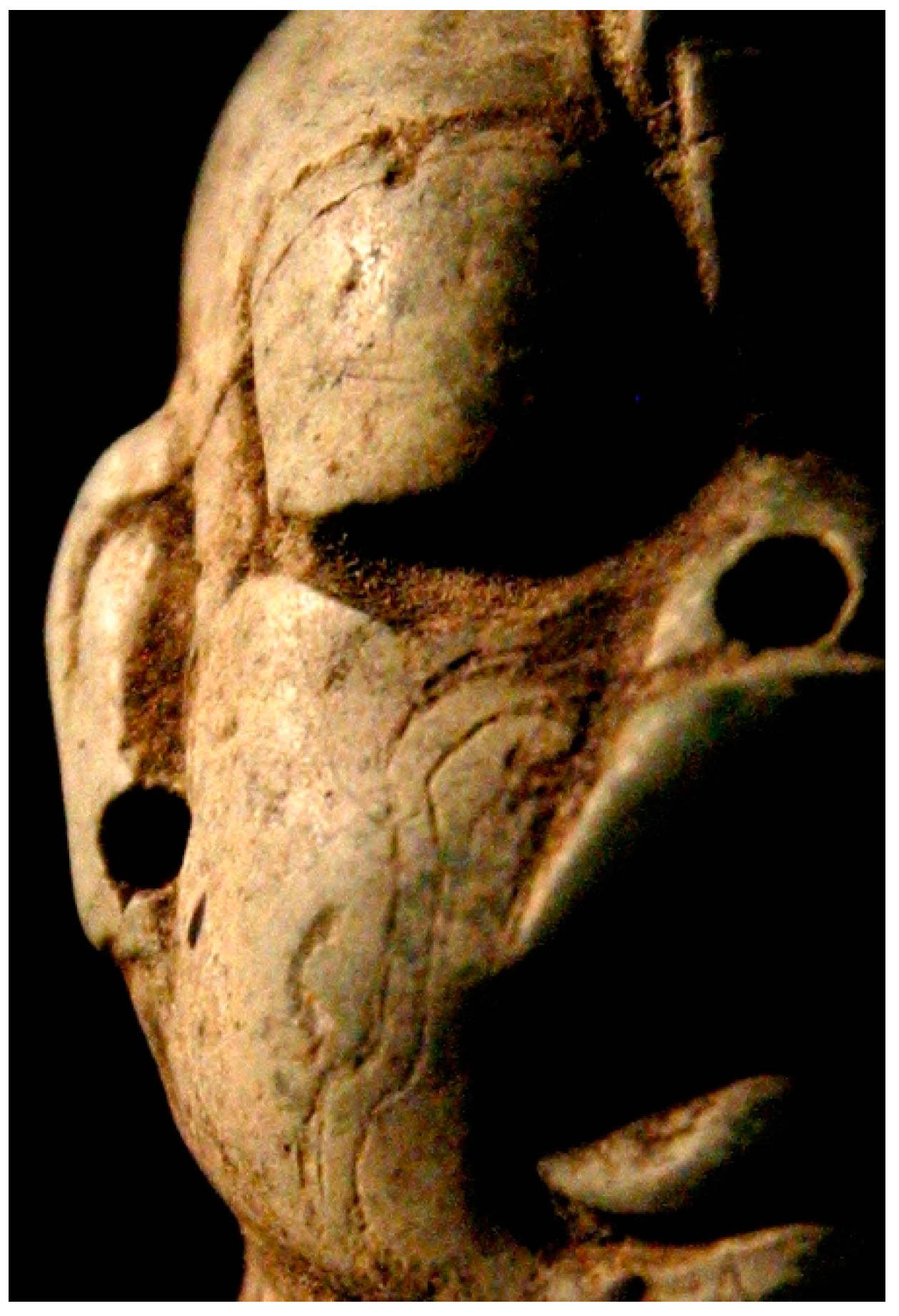

Figure 4), six circles are incised into horizontally defined squares, symbolic vertebrae, of the spine of the figure. In Mayan languages the word for six, wak, generally is homophonous with words for standing up, establishing, as in the term wak chan ajaw, stood up sky lord (

Freidel et al. 1993, p. 73). In turn, stood up sky lord is directly implicated in creation stories. This homophony evidently does not occur in Mixe-Zoque languages. If the Dallas figure was carved and polished in Maya country, it is likely that it would reveal distinct techniques from those used in the Olmec heartland following the scanning electron microscope research on surface finish of

Juan Carlos Melendez (

2019).

It is also notable that the scapulae of the figure are delineated by incising. When reading the figure’s back as a whole, there are the two circles on the upper buttocks and the two incised zones on the shoulders framing the central column of the spine with its six circles reading, in Mayan, stood up, established. This is the Bar and Four Dots motif, the Olmec axis mundi, as discussed by Karl Taube, Kent Reilly, and other scholars, and seen with a maize fetish axis on an unprovenienced celt in the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (

Taube [2004] 2020, Figure 12b).

Reilly (

1996, Figure 7) would see this as a bloodletter, as discussed in the next section.

5. The Old WomanMan Figure as Diphrastic Kenning

The Dallas Old WomanMan is clearly an example of Simon Martin’s theosynthesis, here male and female human-form gods conflated. But, it is apparently also an example of diphrastic kenning before that transcendent idea took written form in Mesoamerica.

Timothy Knowlton (

2002,

2010, p. 23) defines diphrastic kennings as “couplets that equal more than the sum of their parts”. The Dallas figure is a visual and iconographic expression of a diphrastic kenning, mother–father, as implied by Simon Martin in his summary contemplation of the Old Man. In this case, however, the mother–father is explicitly depicted as a singularity becoming a duality. The ambiguity of the gendered roles here is clearly depicted as a wrinkle-faced bearded person with a vulva, an Old Man, one could say THE Old Man, giving birth as a fecund young woman. The logic of this creation sequence is clear enough: all old men were born of fertile women. As

Martin (

2015) reviews, the documented consort of the Old Man is an old woman, Chak Chel, and this couple remains central to Maya thinking for the rest of history. There are young goddesses who are spouse to old gods in Classic Maya storytelling, and possibly these contain further contemplation of this diphrastic kenning. Knowlton (

Knowlton 2010, Figure 2.1) boldly proposed that a key diphrastic kenning in Maya thought and performance, in his orthography

chab akab’, “genesis and darkness”, is a complementary dualism, male and female seen in its glyphic visual expression. Regarding this phrase,

Martin (

2020, p. 146) speaks of it as perhaps representative of” mystical essence” of Classic rulers and

Stuart (

2005b, p. 278) as procreative power.

Harrison-Buck (

2021) suggests that Knowlton’s reading may allude to sexual intercourse.

The T712 glyph (

Thompson and Stuart 1962)

chab is a flaccid penis and scrotum (see

Stross and Kerr 1990, p. 352) and the

akab” Knowlton sees as the inside of a human mouth, a visual play on

ak’, tongue, following the work of

Victoria Bricker (

1986, pp. 73–74). He advances that hypothesis by noting that

ak’ in Classical Yucatecan means clitoris as well as tongue. The exegesis of

chab akab’ is extensive and thematic in his book, citing both Classic period examples and those from his principal era of interest in the Colonial period. The crux of the matter here is the identification of the Creator figure as a bearded old person giving birth to his male genitalia, specifically his penis. The productivity of this hypothesis lies not only in explaining a uniquely explicit depiction of male genitalia on a Middle Preclassic Olmec era figurine, but also explaining why that uniqueness is the case. There is a substantial corpus of nude or nearly nude Middle Preclassic figural men—that is, individuals not endowed with obvious breasts and otherwise with male physical appearance (see

Tate 2012 for discussion of the depiction of sex and gender in Olmec imagery).

Some nearly nude figures have narrow loin clothes over the groin, sometimes fixed with waistbands. Others have celt-like forms that can be read as phalluses or mons pubis.

Taube (

[2004] 2020) suggests some of these might be ballplaying gear like Classic period

palmas. The nude figures either lack genitalia all together or have ambiguous genitalia that can be read as vulvas or penises, as in the case of the Burial 39 heirloom Middle Preclassic figure from El Peru-Waka’ discussed below. There is an example of a figure in the Cleveland Museum of Art (

Milliken 1958, cat. No. 357) in the splayed position and with ambiguous genitalia closer to a mons pubis than any alternative. These male figures are clearly distinguishable from Olmec era stone and ceramic depictions of females, which have skirts, breasts, or explicit female genitalia (

Tate 2012). At La Venta, there is a monumental stone sculpture of female genitalia (

Tate 2012, Figure 8.38).

The men without penises are woman-like. But they are not women; the absence of genitalia, or the studied ambiguity of genitalia, on men conveys the same diphrastic kenning seen in the explicit male/female genitalia of the Dallas figure. That is, these are depictions of men as mother–fathers. The significant difference is that the Dallas Old WomanMan figure is the specific Itzam, the original one, birthing his essential being,

itz, the magic imminent in the universe and his name. A flaccid penis and testicles, remarkably similar to the chab glyph, are one way to spell his name in Mayan glyphic (

Martin 2015, p. 209, Figure 35).

Itz (

Freidel et al. 1993, pp. 50–51) in the context of contemporary rain ceremonies at Yaxuna, is composed of the usually liquid excretions that are realized from the imminent (

Sahlins 2022) and pervade the world, coming through the sky portal of the altar onto the table, the metaphorical field, of the shaman. The circumcised penis of the Dallas Old WomanMan is the image of rain drops in Olmec relief scenes at Chalcatzingo (

Grove 1984;

Reilly 1996). Rain nurtures the seeds in the earth as semen engenders a baby in the womb in the Mixteca Alta today (

Monaghan 1999). The womb, and its aperture, the vulva, are the “darkness” in the diphrastic kenning. Knowlton’s reasoning is that the

ak’ references tongue and clitoris, but iconographically, and in keeping with the mouth image, the Middle Preclassic depiction of a prominent tooth in the upper gum, referencing

Michael Coe’s (

1973) image of death as a shark (

Joralemon 1971), is another darkness associated with penitential bloodletting and with

akab’.

Philip Arnold (

2005, Figure 5) in his study of the Olmec shark and its tooth illustrates a wooden scepter discovered in the Early Preclassic sacred pond of El Manati that resembles an erect penis with a shark’s tooth fixed on the end. Painted red and placed between two concentrations of wooden effigy ancestor bundles, this might well be another materialization of the male and female principles of this diphrastic kenning. Indeed, he suggests that all of the Olmec “scepters” might be tooth-tipped.

David Stuart’s take on

ch’ahb ak’baal in “Ways of Witchcraft” (

Stuart 2021, pp. 200–1) is that

ak’baal refers to darkness populated with creatures associated with witchcraft and sorcery. The

akab’ side of this diphrastic kenning is pursued below, but as Knowlton and Stuart suggest, it is certainly associated with darkness. The mouth allusion of Victoria Bricker is also the primordial cave.

Vail and Hernández (

2012, p. 299), in their study of female ritual in Balankanchen Cave in Yucatan, reference to

Karen Bassie-Sweet’s (

1991) note that the word for cave in Tzotzil Mayan also references vagina. They suggest that rain was produced by a symbolic sexual act. To summarize,

chab akab’, in Knowlton’s reading, is engendering, conjuring, in

Stuart’s (

2021, pp. 200–2) “generation and darkness”. Itzam, in

Martin’s (

2015) reading is “shaman, magician, wizard”.

The Oxtotitlan cave mural depiction of an Olmec ruler engendering a magical jaguar from the maw of a serpentine creature emanating from his scrotum (

Coe 1972, p. 10;

Grove 1970, p. 18) is, like the Dallas figure, a unique expression in my view of

chab akab’’. The cave itself, if the Middle Preclassic sages had the conjuring trope explored here, is

akab’’’ and the ruler himself is pronouncedly

chab in his large scrotum and flaccid penis. This youthful king gestures while he births. The penis and scrotum are the

chab generation and the vision serpent is a further expression of the

akab’ mouth/vulva on the tail/birth canal here quite separated and coming out of the king’s scrotum. The penis is not circumcised, another exception proving a rule, and bears a resemblance to the flaccid penis of the Classic T712 glyph as discussed by Knowlton. This is the most explicit Olmec depiction of a mother–father giving birth to the jaguar spirit companion, an idea pervasive in the were-jaguar baby complex rendered in Olmec stone figures (

Coe 1972). The hypothesis that caves symbolized

akab’, pursued below, and that natural caves were used as performance places for

chab akab’ conjuring and sacrifice, may be further represented in a mural depiction of an Olmec lord and what appears to be a captive in Juxtlahuaca Cave (

Grove 1969;

Gay 1967), also in the southern highlands of Mexico. Here the element depending on the tunic of the lord could be read as a jaguar tail (

Gay 1967) but also as a flaccid circumcised penis (as apparently read it for Coe 1972, p. 10). The lord is wielding what appears to be a sharp instrument in his right hand, similar to those of the Classic period that were used for sacrifice. The Olmec era cave paintings suggest that, already in the Middle Preclassic dark caves, were settings for the kind of conjuring implied in the genesis darkness diphrastic kenning. They also affirm unequivocally that artists of this era were perfectly capable of depicting male genitals when they wanted to do so. The decision not to in the corpus of stone figures was deliberate.

6. The Waka’ Child, Embodied Akab’, and the Chab Talisman

In the Spring of 2006, Michelle Rich and her team discovered a figural masterwork of Olmec style carving inside a mid-seventh century royal tomb at El Peru-Waka’ (

Figure 5) (

Rich et al. 2010). It depicts the body of a softly modeled dancing child (right foot lifted,

Grube 1992). Her right arm was snapped off in antiquity, a commonplace in Olmec art. Here, given the evidence for a mons pubis, she is termed the Waka’ child. Her left arm is arched widely and horizontally across her chest as if she were cradling an invisible or perishable object. Rich (

Rich et al. 2010) has suggested that this child is cradling a perishable talisman of the kind identified by

Reilly (

1996) as a bloodletter and

Taube (

2000,

[2004] 2020, PC.B. 016) as a maize fetish. One can seriate the circumcised penis of the Old WomanMan to stone effigies of phallic versions of this talisman such as might have been embraced by this child.

A large ceramic effigy of this phallic talisman discovered in the Preclassic cemetery of Tlatilco Mexico with an identified shaman there, has incised on the glans the face of the oval-eyed Olmec Maize God with the death shark tooth in the upper gum (

Coe 1973) and wearing the mirror diadem crown (

Taube [2004] 2020;

Reilly 1996). Hands holding so-called knuckledusters (

Andrews V 2005) frame the face. These may represent sources of rain as argued by

Taube (

[2004] 2020). Here one argues that they are cave and womb-like and reference

akab’, darkness, like the death shark. This then evidently is another materialization of the diphrastic kenning of conjuring, here with reference to the Olmec maize god (

Taube 1996). Another sculpture, in the Cleveland Museum of Art (

Milliken 1958, cat. No. 375), depicts a seated man with the tassel-topped phallic talisman in his right hand and a “knuckleduster” in his left hand. This display of the phallic talisman and the vulva “knuckleduster” is, in this argument, the complete Olmec version of the diphrastic kenning of conjuring. As discussed,

Karl Taube (

[2004] 2020, PC.B. 016) analyzed a standing Olmec figure in the Dumbarton Oaks collection that is also wielding the phallic talisman in one hand and the knuckleduster in the other. Both of these figures are devoid of overt genitalia and are ambiguous men identifiable as conjurors.

As explained by

Reilly (

1994, Figure 7) “Slim”, an unprovenanced monumental portable sculpture of an Olmec youth, is cradling a stiff animated version of the talisman, a triple knotted bundle he identifies as the ritual bloodletter, in his right arm. This right-side gesture resembles that of the Waka’ child. “Slim” cradles another phallic talisman in his left arm. As

Knowlton (

2012, p. 24) and others (

Proskouriakoff 1973, p. 352) have suggested, the Classic Maya T712 glyph resembles not only a penis (

Stross and Kerr 1990, p. 352) but also has been seen (

Schele 1985) as a bloodletter. The phallic talisman described here evidently has engendering vegetal references, including maize and bloodletting, in addition to rain and liquid magic as in the Old WomanMan’s penis. Here, one proposes that it is the Middle Preclassic iconic expression of

chab, “genesis” in Knowlton’s understanding (

Knowlton 2010, p. 24), “generation” in

Stuart’s (

2021).

Kent Reilly, in his reading of the Creation plaque in the Dallas Museum (

Reilly 1996;

Freidel and Reilly 2010, Figures 10 and 14), shows that the exclamation shaped raindrop phallus here identified as the Middle Preclassic precursor of

chab is erect and moving upwards from the three stone hearth shown to be incised on the bottom of the Dallas Old WomanMan figure. The

chab raindrop moves upwards through a down-turned crescent aperture of the animate world, and inseminates a mountain cave,

akab’. This water mountain, in turn, is sprouting a cruciform vegetation he suggests is the axis mundi maize plant.

Another iconographic expression of this diphrastic kenning, the bas-relief at Chalcatzingo in Morelos Mexico, Monument 1 (

Grove 1984, Figure 5), depicts the

chab phallic rain drops falling from

akab’ knuckleduster shaped clouds

Taube (

[2004] 2020) identifies as bloodletting instruments fertilizing vegetation growing on and around the mouth of a living quatrefoil mountain cave (

Guernsey 2010), again the Middle Preclassic

akab’. The knuckleduster shaped clouds seem to again signal

akab”, the female source of the male rain. Inside the cave of Chalcatzingo Monument 1 sits a deity dressed in female attire, a goddess or queen, cradling a “lazy-S” bundle, an infant rain cloud (

Reilly 1996). She is evidently the source of the falling rain. She is seated upon another lazy-S cloud as her throne. This famous bas-relief is carved on a cliff wall of the Chalcatzingo mountain that is itself paired with a second prominent hill to form what can be discerned visually as a giant v-shaped vulva. Rainwater was channeled past the bas-relief in a carved trough. The conjuring of rain was the evident purpose of Chalcatzingo and its sages.

7. Olmec Akab’: The Mouth and the Tooth

The Waka’ child is wearing a mask of the Olmec death shark (

Figure 6). The open mouth of the child, singing or declaiming, has a single prominent shark’s tooth in the upper gum. In his exegesis on

chab akab’,

Knowlton (

2002,

2012) makes the case for Victoria Bricker’s identification of the Classic Maya

akab’ as a play on

ak, tongue, a near homophone. He points to the clear evidence that royal women in particular practiced tongue perforation as autosacrifice. They draw long spiked cords through their tongues, a serpentine phallic symbol discussed below in the context of the incised symbols on the front of the Waka’ child.

Ak, as he notes, is also a term for clitoris in Classical Yucatecan. Ancient Maya clearly link the mouth with the vagina and anus as framing the axial interior pathway of human and other beings (

Freidel et al. 1993;

Martin 2015;

Stuart 2005a). Having shown why the living mountain aperture, the cave mouth, might be the precursor of

akab’, the

ak clitoris is represented not just as a tongue but as a cave tooth—as it is in the mouth of the Late Preclassic creation mountain cave on the north wall mural of the Pinturas shrine at San Bartolo (

Saturno et al. 2005;

Taube et al. 2010).

The tooth of prominence in Classic Maya art is the shark’s tooth, and while there are many other depictions of fangs, teeth, and tongues in Middle Preclassic art, the shark’s tooth is a particular signature of darkness and death. The Waka child’s face is that of the Olmec death shark, a striking juxtaposition of youth and death. The shark is easily identifiable by its sagittal fin, its crescent moon eyes, and its prominent single sharp tooth in the upper gum.

Coe (

1973) associates this death shark with darkness and the crescent eyes are rendered as dark. There are variants of this

akab’ death face. An unprovenienced Middle Preclassic greenstone pendant in the Cleveland Art Museum (

Handbook of the Cleveland Museum of Art/1969, page 290) depicts the crescent eyed head of a dead ruler or God. The sagging mouth and bundle knot below the severed head make clear that this is a death image. The mouth is toothless, but the individual wears the mirror diadem seen in other Olmec depictions like the Dumbarton Oaks seated ruler (

Reilly 1996;

Taube [2004] 2020) and the on the mask incised on the Chalcatzingo Vase discussed below.

The body and the face of the Waka’ child iconographically signal diphrastic kenning here if one accounts for the phantom talisman cradled by the child. The prominent shark’s tooth is not unique; there many other fanged (as well as toothless) Olmec grimacing faces, but it is a focus of attention on this dancing child. The shark’s tooth remains a major image in later Maya art particularly associated with the watery eastern sun God (

Stuart 2005a), and it is, along with the stingray spine, evidently a bloodletter in autosacrifice. In another important depiction of the Olmec death shark’s head, the Chalcatzingo Vase (

Freidel and Reilly 2010, Figure 11), the central image of a mask of the deceased is framed by four shark’s teeth. The Chalcatzingo Vase is a famous Middle Preclassic pyriform vessel thought to be from the Mexican highlands, probably Morelos. Its rich symbolism is a source of sustained discussion regarding Olmec cosmology (

Reilly 1994).

As in the case of the Cleveland pendant mentioned above, the feathered mirror diademed Chalcatzingo mask is bundle knotted at the bottom. Here, an additional knot fastened at the back of the head suggests it is a bundle mask of a dead person or deity. The three knots vertically framing the bundle head (

Reilly 1994;

Freidel and Reilly 2010, Figure 11) harken to the three knots of the bloodletter of the Olmec and Maya (

Joralemon 1974), an allusion to the Olmec version of

chab. Framing the open bundle and establishing the four-fold space of the cosmos, are shark’s teeth bloodletters, referencing the extension of tongue to tooth and clitoris as argued above. Outside of them are hands of this animate ceramic effigy bundle, one holding a knuckleduster,

akab”; and the other the

chab talisman that

Taube (

[2004] 2020) identifies as a feather bundle and maize fetish.

Reilly (

1994) discerns this as the three knotted bundle/bloodletter associated with self-sacrifice of men (see

Joralemon 1974) connoting the male principle in the diphrastic kenning genesis. As to the knuckleduster, Taube gives a long and insightful review of this artifact, citing

E. Wyllys Andrews V’s (

2005) equally substantial discussion, and concludes that it is a weapon used in boxing, which is to say, another means of letting blood (from the nose and face) and possibly a

chab allusion. However, the shell is cave and womb-like (

Tate 2012) and it is thus an

akab’ reference.

Taube (

[2004] 2020, Figure 12) also notes that this enchanted instrument generates the penis-shaped rain in the scene of El Rey at Chalcatzingo, making it like-in-kind to the animated cave of the rain-bringer identifiable as female. So, the knuckleduster is female, darkness, the source of rain. In this reading of the Chalcatzingo Vase,

chab akab’ conjuring of the animate ceramic effigy bundle pyriform vase frames

akab’ clitoris teeth, further framing the

akab’ mouth of the dead personage, whose fontanel is sprouting new growth, a cruciform being like the Dallas Creation plaque, and a feathered sky band, elements of the maize fetish/bloodletter

chab. The overall reading of the pyriform vase is that it is shaped like a royal bundle effigy personifying and animating the deceased symbolized by the mask and that it is being placed in the

akab’ cave reliquary shrine signaled by the stalactite-like shark’s teeth.

The crescent shaped Chalcatzingo El Rey and other clouds (Grove and Angulo V. Chapter 9 in

Grove 1984) presage the downturned basins of Early Classic Teotihuacan imagery, particularly the genital basin of the Tepantitla Mural (

Pasztory 1976) with its liquids and precious enchanted objects flowing out. That basin, turned right-side up, is what

Karl Taube (

1983) identifies as the mirror bowl of the Goddess (Spider Woman) and what indeed is evidently a general icon of location or firmament at Teotihuacan as seen in the Atetelco palace murals (

Nielsen and Helmke 2008). The up-turned basin on the Tepantitla Mural is manifest as the sombrero-shaped bowl with the rhomboid eyes of the Old Fire God. That up-turned basin is the firmament, the mountain side, and base of the axis mundi world trees. This up-turned mirror bowl is discernable at the base of the vertically read incised pictographic story on the Humboldt Celt (

Freidel and Reilly 2010, Figure 17b).

Directly above the bowl on the Humboldt Celt is the shark’s tooth bloodletter. The positioning of the shark’s tooth pointing upwards, in contrast to the Chalcatzingo Vase depictions, suggests a conflation of its references to clitoris and penis (upright as in the phallic raindrops on the Dallas Creation plaque) both

chab and

akab’. Above this is the Kan Cross marked mirror of the mirror bowl motif suggested by

Taube (

[2004] 2020)—there are several other Olmec era mirror bowls—here in this celt framed by symbols that include the Olmec crown (

Stuart 2015, Figure 11) and the sky scaffold (

Reilly 1996). Above this mirror is a hand setting the hearth stones, and above that arms in receptive embrace of royal insignia and weapons. The central image in that array is of a bound headscarf that resembles what

Martin (

2015, Figure 35) identifies in the Classic Maya script as a brief symbol of Itzam. The provisional reading of the Humboldt Celt here suggests that there are more opportunities to study the iconography of Middle Preclassic diphrastic kenning.

Like the Chalcatzingo Vase mask, the mask of the Waka’ child has allusions to rebirth in the fine-line incised symbols on its eyebrows (

Figure 7,

Figure 8,

Figure 9 and

Figure 10).

Michelle Rich observed that these effigy tattoos, while eroded, look like those on the hands of the Olmec young lord slim. What is clear is that they are clefted at the top and oval-eyed like the Olmec maize God (

Taube 1996). Framing a trefoil sprout diadem, they constitute a royal crown symbolizing rebirth. The fine-line incising is found elsewhere on the child, and while worn, it forms a discernable pattern on the front (

Figure 7,

Figure 8,

Figure 9 and

Figure 10). Kent Reilly observed that the double-line incised motifs emanate from the nostrils and form the upper half of a quatrefoil portal (

Figure 11 and

Figure 12) (

Guernsey 2010), as seen in the famous Chalcatzingo portal monument (

Grove 1984). That animated portal monument, which David Grove suggested was used for performing rulers to enter and exit a chamber on the summit of a pyramid at the base of the clefted mountain, references the half quatrefoil cave of Chalcatzingo Monument 1 and

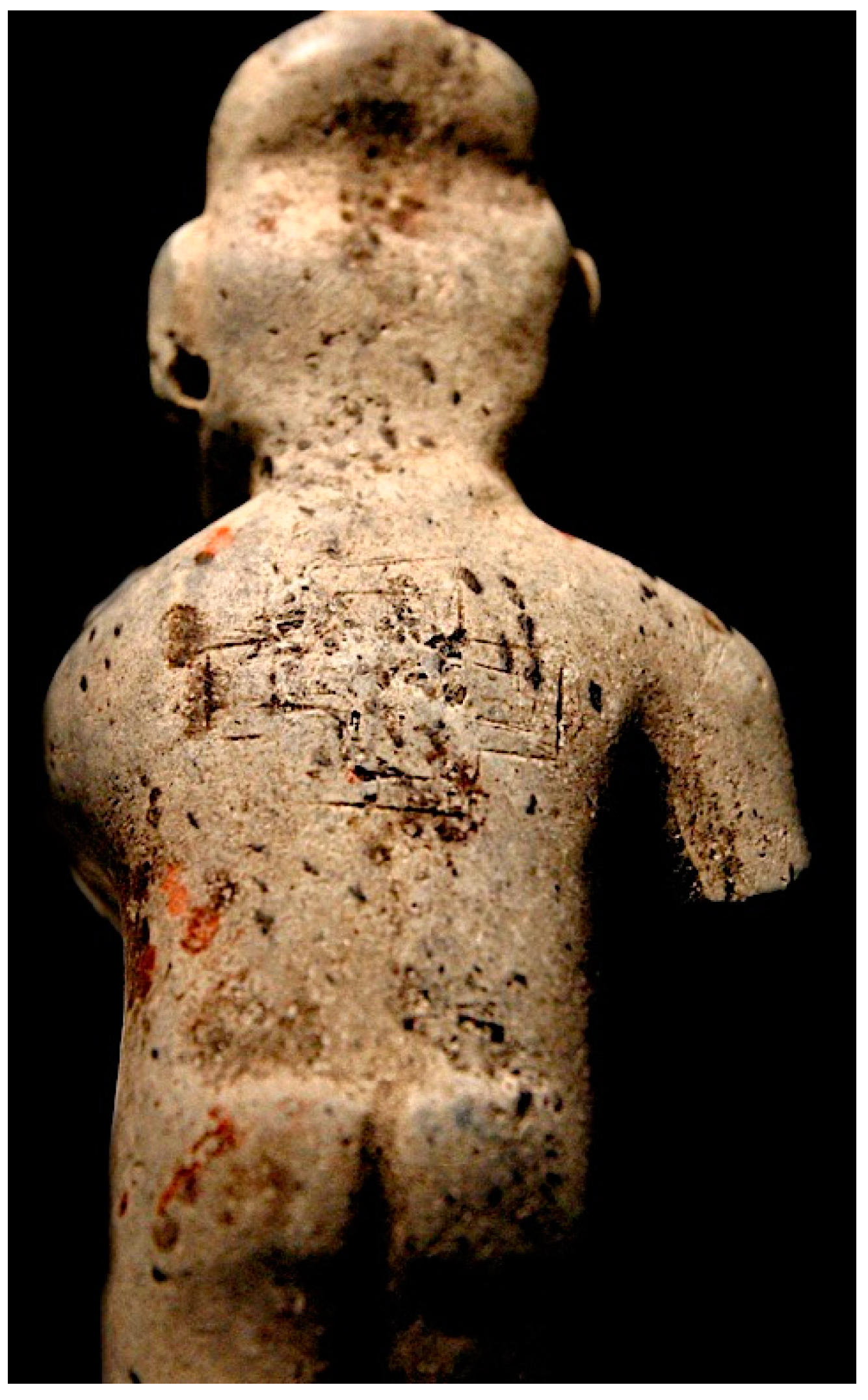

akab’. Incised on the back of the child (

Figure 13) is a full image of the rectilinear quatrefoil portal, underscoring the intention of the portal framing the mouth on the front. The child is, in its entirety, the

akab’ portal.

Michelle Rich identifies the undulating extending cords on the child’s front (

Figure 11 and

Figure 12) as possibly depicting a round edged mountain such as those found on the Late Preclassic San Bartolo mountain on the north wall of the Pinturas Shrine (

Saturno et al. 2005), Classic Maya Mountain masks (

Stuart 1997), and characteristic of Classic and Postclassic highland Mexican depictions. The cords on the front of the child are animate, as they are framed by occasional brow elements associated with Olmec serpents. The dancing child, in this view, is the mountain of the cave mouth,

akab’. Sketched on the belly (

Figure 12), the area of the womb on a female, are three triangles in a line. While three circles would seem to symbolize the hearth stones on the Dallas Creation plaque, these three points have the shark’s tooth shape, and they point up like the teeth on the Chalcatzingo Vase. In the cave womb, they would be stalagmites pairing with the stalactite tooth in the mouth of the child. However, there may also be a

chab allusion here: their location, and upward facing direction, resembles the inseminating exclamation point raindrops on the Dallas Creation plaque referenced earlier.

Finally (

Figure 14), the ambiguous genitals of the child come as no surprise given the discussion here.

The Old WomanMan figure is an exception that defines the Olmec rule: the phallus is usually not depicted explicitly—the other exceptions notably being paintings inside caves. On figures, the narrow loin cloth, the floating celt, can convey the idea of male genitalia. But as argued here, the Olmec phallus, like the Maya phallus, when explicitly depicted as on the Old WomanMan, is usually circumcised, or otherwise displays the glans penis. The Waka’ child does not have a glans penis explicitly delineated at its top to form the “explanation point” image. What it does have is the triangular incision at the tip that signals the aperture of a girl’s narrow mons pubis. The narrowness of this mons pubis sustains the deliberate ambiguity cultivated by Middle Preclassic artists in depicting the sex of mother–father figures. The Waka’ child is seemingly a girl, a young goddess before the breasts develop. She is the

akab’, the cave womb where all life must be created or reborn. She embraces the ephemeral and here invisible

chab, the genesis liquid

itz in its talisman (aspergillum?) bundle form. The notion of the progenitor as girl, seen in the young goddess figure in Tomb 1 at La Venta (accompanied by a fossil giant shark’s tooth, Drucker et al. 1959), prevailed with the adolescent Goddess of Burial 2 of the Moon Pyramid at Teotihuacan in the Early Classic period (

Sugiyama and López Luján 2007), and was remembered at Waka’ with the placement of the Waka’ Child, a thousand years after her crafting, in the eastern eternal conjuring place of a king whose seventh century funeral was presided over by another powerful girl, Lady K’abel (

Rich et al. 2010), who would rule in the name of the Moon goddess and her aegis, the stalactite tooth effigy of the war god Akan Yaxaj (

Navarro-Farr et al. 2020).