The Africanization of Catholicism in Ghana: From Inculturation to Pentecostalization

Abstract

:1. Introduction

Africa is offering its own distinctive view to the Catholic Church. It is related to ways of being a Christian. Liturgical innovations taking place here show that there is more than one way of celebrating Eucharist. The general patterns are the same, but Africans would say it is important to celebrate according to the spirit of the people. And the way we do it in Africa is according to our spirit. In terms of music, in terms of body movements, in terms of emotions… When you are here and you enter the church you see something different [than in Europe]. You see that the liturgy is not absolutely solemn. Our liturgy sometimes seems to turn towards chaos; there is not much order. But that is the way people here celebrate things. Just in liturgy we show our culture.(Interview, 21 January 2010)

2. (Trans)Forming Ghanaian Catholicism

2.1. Early Stages

2.2. Independent Ghana and Post-Conciliar Church

2.3. Charismatic Movements

3. Returning to the Roots

3.1. National Heritage Project

3.2. Sankofaism Catholic-Style

3.3. African Tradition, Pentecostal Spirituality

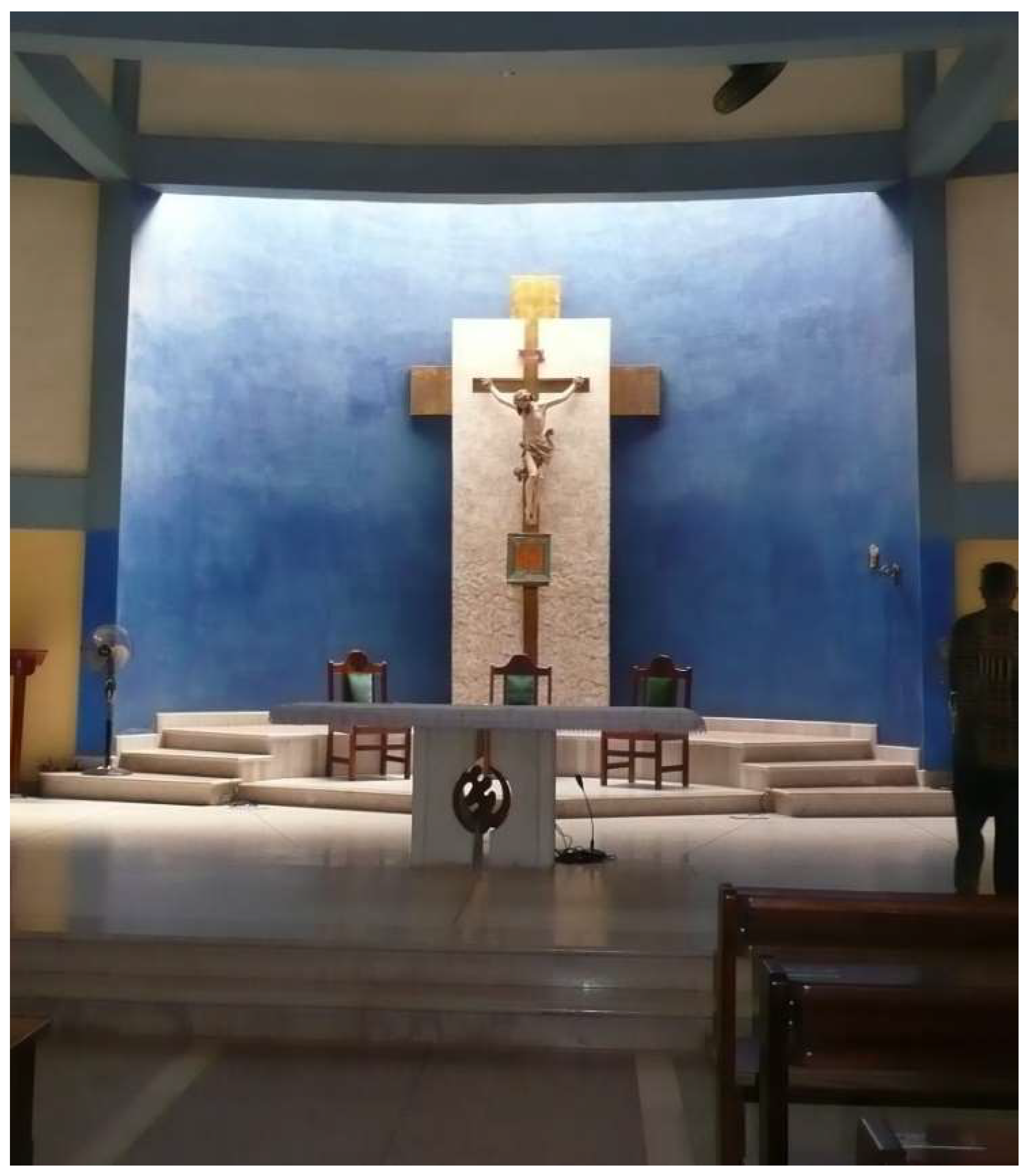

4. Corpus Christi

4.1. Dancing for the King

Here people carry their kings/chiefs [Twi ahene] on their arms and shoulders around the town. […] We carry Christ himself. It is God that we worship. And as people carry their kings, why cannot we carry our Lord? The one who is supreme king over everything. And during this procession I can pray, I can use this means of prayer and say my intentions to God. For example, some time ago we went to K. [a bigger town nearby]. And I was not feeling well, my body was not feeling well. But my colleagues [from the choir] forced me to go and join them during the procession in K. And I took part in it. I sang and danced. So, at the end of the procession I was ok. There is a belief that it is important for us to have this program. As traditionalists carry their kings/chiefs.(Interview, 18 January 2013)

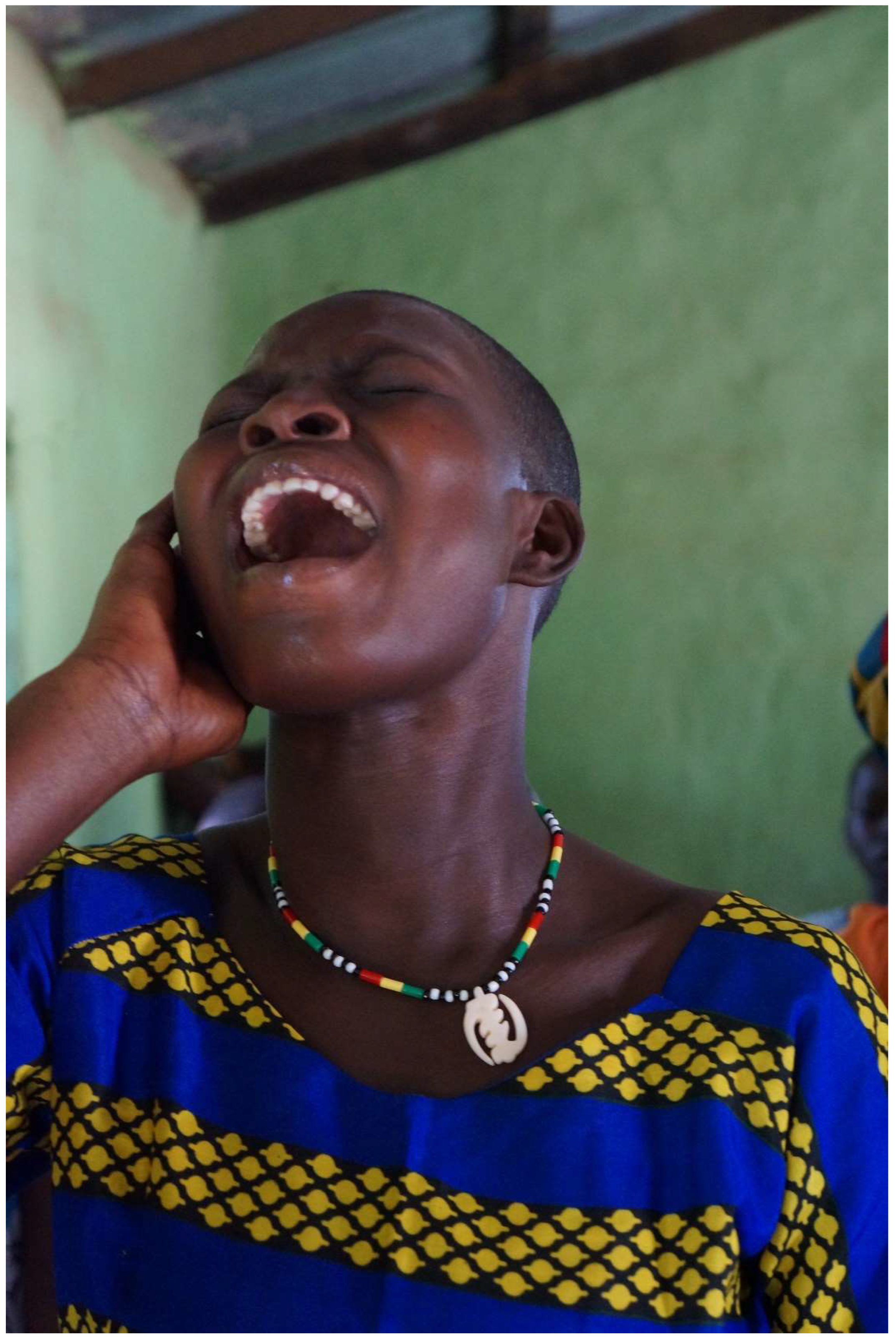

4.2. “Filled with the Spirit”

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Comparing the previous census conducted in 2010, the recent census has revealed an increase in those identifying as Pentecostal/Charismatic (from 28.3% to 31.6%) and other Christians (from 11.4% to 12.3%) as well as a decline in those identifying as Protestant (from 18.4% to 17.4%) and Catholic (from 13.1% to 10%). The 2021 census estimated followers of Islam at 19.9%, Traditionalists at 3.2%, No Religion at 1.1%, and Other at 4.5%. The labelling of the religious groups was performed by the authors of the census survey and on its own reveals an interesting discourse about various currents of Christianity and conceptualizations of religion. See: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1172414/religious-affiliation-in-ghana/ (accessed on 10 January 2023). |

| 2 | The Church of Pentecost overtook the Roman Catholic Church (comparing the previous census from 2010), with a membership estimated at 10.8% of the Ghanaian population. See https://thecophq.org/statistics/ (accessed on 5 May 2023). After the release of the census record, the leaders of the Roman Catholic Church expressed concerns about a decline in Catholic membership and the growth of Pentecostal and Charismatic Churches. |

| 3 | The Apostolic Vicariate of Lower Volta was also transformed into the Diocese of Keta. |

| 4 | Visual symbols originally connected with Asante textiles refer to exact proverbs and traditional knowledge. |

| 5 | However, an insufficient number of African clergy and a quickly growing African population meant that in the 1970s “while the great majority of Catholic bishops were Black the overwhelming majority of priests remained White” (Sundkler and Steed 2000, p. 1021; see also Hastings 1979, pp. 237–40). The situation changed in the 1980s. |

| 6 | Sankofa is also used in the context of African and black diasporas. |

| 7 | In some countries the celebration is moved from Thursday to the following Sunday. |

References

- Ad gentes. 1965. Decree on the Mission Activity of the Church. Vatican: The Holy See. [Google Scholar]

- Amanor, Jones Darkwa. 2004. Pentecostalism in Ghana: An African Reformation. Cyberjournal for Pentecostal-Charismatic Research 13: 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Asamoah-Gyadu, J. Kwabena. 2010. ‘The Evil You Have Done Can Ruin the Whole Clan’: African Cosmology, Community and Christianity in Achebe’s Things Fall Apart. Studies in World Christianity 16: 46–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asamoah-Gyadu, J. Kwabena. 2013. Contemporary Pentecostal Christianity: Interpretations from an African Context. Oxford: Regnum Books International. [Google Scholar]

- Asamoah-Gyadu, J. Kwabena. 2014. ‘God Bless our Homeland Ghana’: Religion and Politics in a Post-Colonial African State. In Trajectories of Religion in Africa: Essays in Honor of John S. Pobee. Edited by Cephas N. Omenyo and Eric B. Anum. Leiden and Boston: Brill, pp. 165–83. [Google Scholar]

- Baum, Robert M. 2016. Historical Perspectives on West African Christianity. In The Routledge Companion to Christianity in Africa. Edited by Elias Kifon Bongmba. New York and London: Routledge, pp. 79–91. [Google Scholar]

- Benedict XVI. 2009a. Africae Munus. Post-Synodal Apostolic Exhortation. Vatican: The Holy See. [Google Scholar]

- Benedict XVI. 2009b. Homily of His Holiness Benedict XVI. Eucharistic Celebration for the Opening of the Second Special Assembly for Africa of the Synod of Bishops. Vatican: Dicastero per la Comunicazione—Libreria Editrice Vaticana. Available online: https://www.vatican.va/content/benedict-xvi/en/homilies/2009/documents/hf_ben-xvi_hom_20091004_sinodo-africa.html (accessed on 5 May 2023).

- Christian, Angela. 1976. Adinkra Oration. Accra: Catholic Book Centre. [Google Scholar]

- de Witte, Marleen. 2001. Long Live the Dead! Changing Funeral Celebrations in Asante, Ghana. Amsterdam: Aksant Academic Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- de Witte, Marleen. 2009. Modes of Binding, Moment of Bonding: Mediating Divine Touch in Ghanaian Petencostalism and Traditionalism. In Aesthetic Formations: Media, Religion, and the Senses. Edited by Birgit Meyer. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 183–205. [Google Scholar]

- de Witte, Marleen. 2018. Corpo-Reality TV: Media, Body and the Authentication of ‘African Heritage’. In Sense and Essence: Heritage and the Cultural Production of the Real. Edited by Birgit Meyer and Mattijs van de Port. New York and Oxford: Berghahn, pp. 182–211. [Google Scholar]

- de Witte, Marleen, and Birgit Meyer. 2012. African Heritage Design: Enterteinment Media and Visual Aesthetics in Ghana. Civilisations 61: 43–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsbernd, Alphonse. 2000. The Story of the Catholic Church in the Diocese of Accra. Accra: Catholic Book Centre. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, Robert B. 1998. West African Religious Traditions. Maryknoll: Orbis Books. [Google Scholar]

- Hastings, Adrian. 1979. A History of African Christianity 1950–1975. Cambridge, London, New York and Melbourne: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hastings, Adrian. 1994. The Church in Africa 1450–1950. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hess, Janet. 2001. Exhibiting Ghana: Display, Documentary, and “National” Art in the Nkrumah Era. African Studies Review 44: 59–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isnart, Cyril, and Nathalie Cerezales. 2020. Introduction. In The Religious Heritage Complex. Legacy, Conservation, and Christianity. Edited by Cyril Isnart and Nathalie Cerazales. London, Oxford, New York, New Delhi and Sydney: Bloomsbury Academic, pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- John Paul II. 1995. Ecclesia in Africa. Post-Synodal Apostolic Exhortation. Vatican: The Holy See. [Google Scholar]

- Kirby, Jon P. 2012. The Power and the Glory: Popular Christianity in Northern Ghana. Accra: Regnum Africa. [Google Scholar]

- Lado, Ludovic. 2009. Catholic Pentecostalism and the Paradoxes of Africanization: Processes of Localization in a Catholic Charismatic Movement in Cameroon. Leiden and Boston: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Lado, Ludovic. 2017. Experiments of Inculturation in a Catholic Charismatic Movement in Cameroon. In The Anthropology of Catholicism: A Reader. Edited by Kristin Norget, Valentina Napolitano and Maya Mayblin. Oakland: University of California Press, pp. 227–41. [Google Scholar]

- Lindhardt, Martin. 2014. Introduction: Presence and Impact of Pentecostal/Charismatic Christianity in Africa. In Pentecostalism in Africa: Presence and Impact of Pneumatic Christianity in Postcolonial Societies. Edited by Martin Lindhardt. Leiden and Boston: Brill, pp. 1–53. [Google Scholar]

- Majawa, Clement. 2016. African Christianity in the Post-Vatican II Era. In The Routledge Companion to Christianity in Africa. Edited by Elias Kifon Bongmba. New York and London: Routledge, pp. 214–31. [Google Scholar]

- Mawusi, Emmanuel Richard. 2009. Inculturation: Rooting the Gospel Firmly in Ghanaian Culture. A Necessary Requirement for Effective Evangelization for the Catholic Church in Ghana. Ph.D. thesis, Uniwersität Wien, Vienna, Austria. [Google Scholar]

- Mayblin, Maya, Kristin Norget, and Valentina Napolitano. 2017. Introduction: The Anthropology of Catholicism. In The Anthropology of Catholicism: A Reader. Edited by Kristin Norget, Valentina Napolitano and Maya Mayblin. Oakland: University of California Press, pp. 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, Birgit. 1999. Translating the Devil: Religion and Modernity Among the Ewe in Ghana. Trenton and Asmara: Africa World Press. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, Birgit. 2006. Religious Sensations. Why Media, Aesthetics and Power Matter in the Study of Contemporary Religion. Amsterdam: Vrije Universiteit. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, Birgit. 2010. ‘Tradition and Colour at its best’: ‘Tradition’ and ‘Heritage’ in Ghanaian Video-Movies. Journal of African Cultural Studies 22: 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, Birgit. 2017. Catholicism and the Study of Religion. In The Anthropology of Catholicism: A Reader. Edited by Kristin Norget, Valentina Napolitano and Maya Mayblin. Oakland: University of California Press, pp. 305–15. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, Birgit, and Marleen de Witte. 2013. Heritage and the Sacred: Introduction. Material Religion 9: 275–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, David. 2010. Introduction: The Matter of Belief. In Religion and Material Culture: The Matter of Belief. Edited by David Morgan. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Niedźwiedź, Anna. 2012. Being Christian in Africa: Identities Lived Within a Catholic Community in Central Ghana. In Multiple Identities in Post-Colonial Africa. Edited by Vlastimil Fiala. Hradec Králové: Publishing House Moneta-FM for the University of Hradec Králové, pp. 151–61. [Google Scholar]

- Niedźwiedź, Anna. 2015. Religia przeżywana. Katolicyzm i jego konteksty we współczesnej Ghanie. Kraków: Libron. [Google Scholar]

- Obeng, Pashington. 1996. Asante Catholicism: Religious and Cultural Reproduction Among the Akan of Ghana. Leiden, New York and Köln: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Omenyo, Cephas N. 2011. New Wine in an Old Wine Bottle? Charismatic Healing in the Mainline Churches in Ghana. In Global Pentecostal and Charismatic Healing. Edited by Candy Gunther Brown. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 231–49. [Google Scholar]

- Ossom-Batsa, George, and Felicity Apaah. 2018. Rethinking the Great Commission: Incorporation of Akan Indigenous Symbols into Christian Worship. International Review of Mission 107: 261–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Premawardhana, Devaka. 2020. Reconversion and Retrieval: Nonlinear Change in African Catholic Practice. Religions 11: 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senah, Kojo. 2013. Sacred Objects into State Symbols: The Material Culture of Cheiftaincy in the Making of a National Political Heritage in Ghana. Material Religion 9: 350–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shramm, Katharina. 2000. The Politics of Dance: Changing Representations of the Nation in Ghana. Afrika Spectrum 35: 339–58. [Google Scholar]

- Sundkler, Bengt, and Christopher Steed. 2000. A History of the Church in Africa. Cambridge, New York, Port Melbourne, Madrid and Cape Town: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tengan, Alexis B. 2013. Introduction. Approaching the Cultural History of Northern Ghana. In Christianity and Cultural History in Northern Ghana: A Portrait of Cardinal Peter Poreku Dery (1918–2008). Edited by Alexis B. Tengan. Brussels, Bern, Berlin, Frankfurt am Main, New York, Oxford and Wien: P.I.E. Peter Lang, pp. 17–28. [Google Scholar]

- Woets, Rhoda. 2018. ‘Heated Discussions Are Necessary’: The Creative Engagement with Sankofa in Modern Ghanaian Art. In Sense and Essence: Heritage and the Cultural Production of the Real. Edited by Birgit Meyer and Mattijs van de Port. New York and Oxford: Berghahn, pp. 212–35. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Niedźwiedź, A. The Africanization of Catholicism in Ghana: From Inculturation to Pentecostalization. Religions 2023, 14, 1174. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14091174

Niedźwiedź A. The Africanization of Catholicism in Ghana: From Inculturation to Pentecostalization. Religions. 2023; 14(9):1174. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14091174

Chicago/Turabian StyleNiedźwiedź, Anna. 2023. "The Africanization of Catholicism in Ghana: From Inculturation to Pentecostalization" Religions 14, no. 9: 1174. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14091174

APA StyleNiedźwiedź, A. (2023). The Africanization of Catholicism in Ghana: From Inculturation to Pentecostalization. Religions, 14(9), 1174. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14091174