Religious Heritage Complex and Authenticity: Past and Present Assemblages of One Cypriot Icon

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Legends in Past and Present Assemblages

3. The Status of the Panagia Amirou Icon

4. Religious Heritage Complex

5. Authentication of the Icon’s Exceptional Status

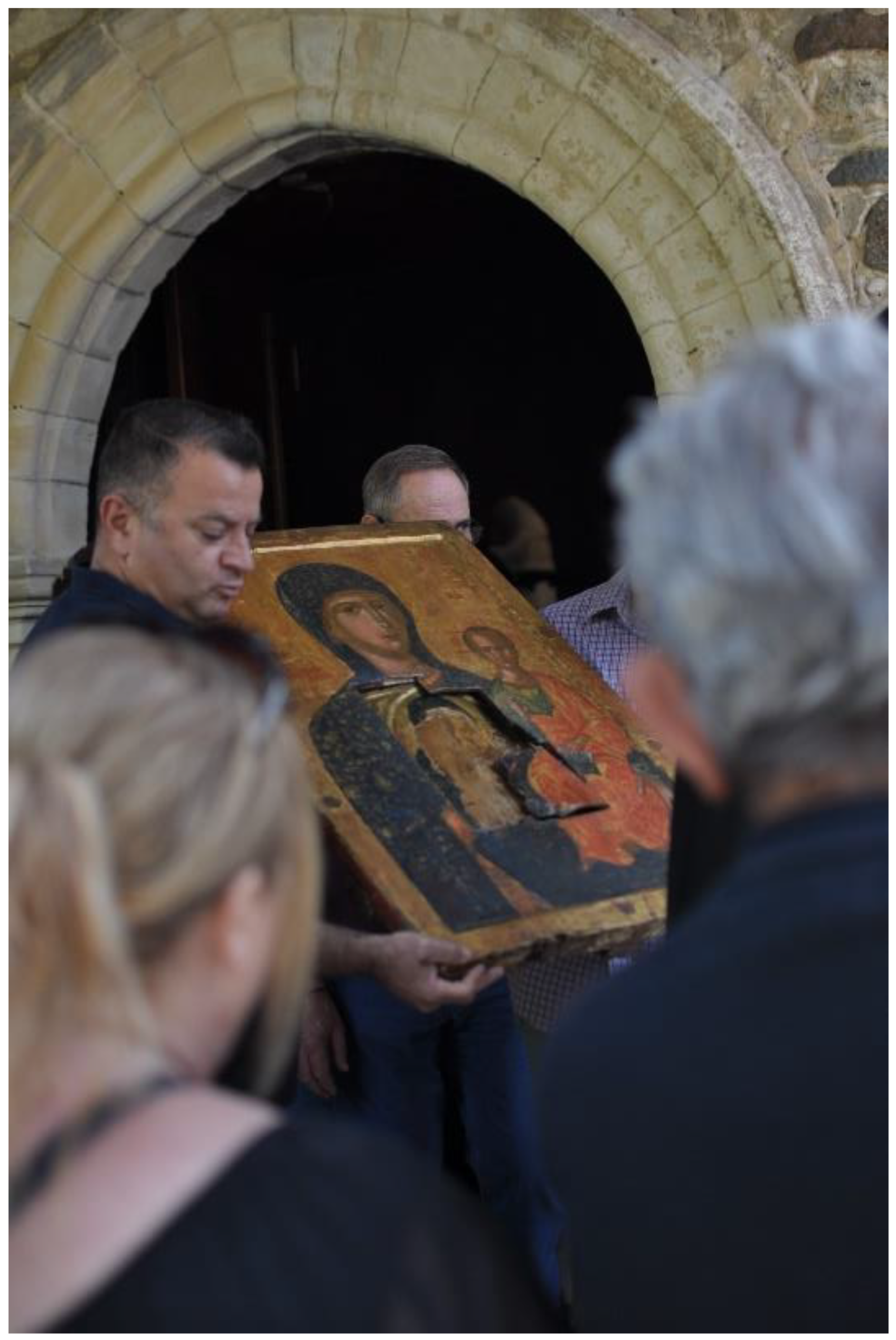

6. The Role of Processions in the Process of Authentication and Remembering

7. The Power of an Assemblage Form

8. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

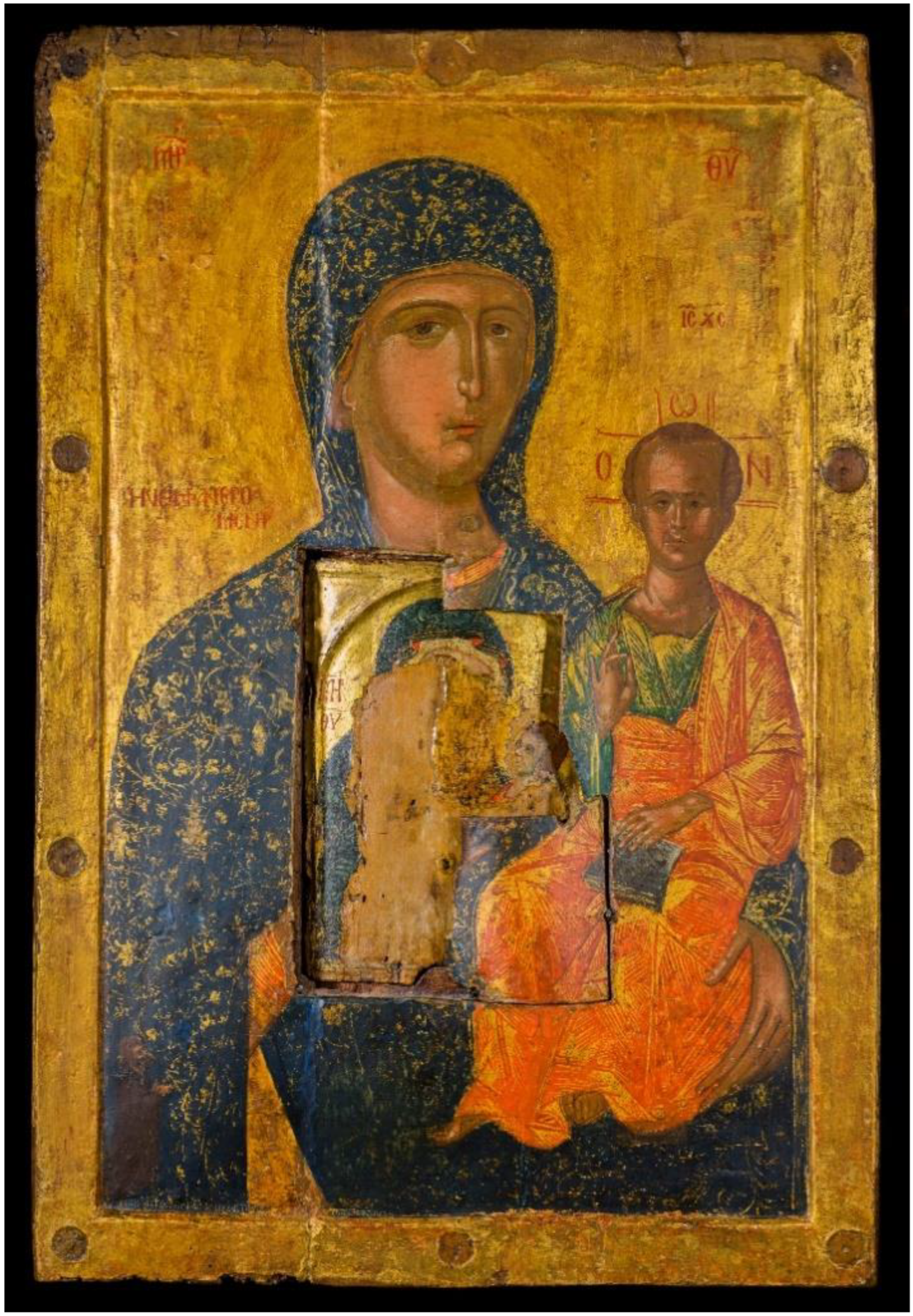

| 1 | For more on icons of this unusual type, which contain smaller, inserted icons and are known under the term “composite icons”, see: (Vocotopoulos 2000, 2002). For more on this specific composite icon, see: (Sophocleous 2006, pp. 239–40, no. 219–20). See also: (Kallē 2019, vol. 1, p. 352, no. E7α:1; Vasilios Metropolitan of Constantia and Ammochostos and Kakkoura 2020, pp. 43–44, Figure 21). |

| 2 | The exact date is not known. Athanasios Papageorgiou mentioned the 18th century (Papageōrgiou 1985, pp. 30–31). Nevertheless, Sykoutris noted in 1924 that the oldest inhabitants of Apsiou remember the last monk (Sykoutrēs 1924, p. 81); therefore, it seems plausible that the monastery was closed in the 19th c. |

| 3 | Descriptions are available in the local newspapers from the time when the monastery was still closed, see: Γιάννης Χριστοφίδης, Παναγία η Aμιρού, «Σημερινή» 23 April 1990. Γιάννης Χριστοφίδης, Παναγία η Aμιρού, «Ελευθερία της γνώμης» 24 April 1990. I would like to thank Mr. Ioannis Christofidis for sharing copies of the above-mentioned publications with me. |

| 4 | For an overview of the current state of research regarding the relationship between heritagization and religion, see: (Thouki 2022). |

| 5 | The Oral Tradition Archive is the result of years of systematic research. Cyprus Research Center undertook and conducted this specific program in order to preserve the island’s intangible cultural heritage, history, ethnography, folklore, linguistics, literature, sociology, economics, and politics. It began in 1990 by a group of researchers* at the Cyprus Research Center and was completed in 2010. The audio material of the Oral Tradition Archive consists of over eight thousand interviews, including reminiscences and testimonies of people aged eighty and over living in various parts of the island. The material is recorded on audio tapes and in digital format. *The researchers that participated in the program were: 1990–2004: Theophano Kypri, Kyprianos Louis, Georgios Matthaiou, Kyriakos Mparris, Anna Neophytou, Nasa Patapiou, Kalliopi Protopapa, Stella Spyrou; 2004–2005: Grigoris Ioannou, Maria Makri; 2007–2010: Constantina Constantinou, Constantinos Georgiou, Kyriakos Ioannou, Dimitris Kalogirou, Vasiliki Kella, Elena Matsangou, Zoe Papaconstantinou, Antonis Pericleous, Argiro Xenophontos. I would like to express my gratitude for allowing me to use the collection of the Oral Tradition Archive in my research. |

| 6 | I have elaborated on the application of Assemblage Theory for the study of icons in my paper “Assemblage Theory and Icons: Composite Icons as an Assemblage within an Assemblage” presented during the 54th Spring Symposium of Byzantine Studies: Material Religion in Byzantium and Beyond (University of Oxford, 17–19 March 2023). |

| 7 | For more on the name of the monastery, see: (Goodwin 1978, p. 643). |

| 8 | For more on the figure of Gunnis, see: (Storrs 1939, p. 512). |

| 9 | Oral Tradition Archive (Cyprus Research Centre), record no. 7230, Λεμ.-Aψ.7: Limassol—Apsiou, testimony: E. D., researcher: A. Pericleous, 11 November 2008. |

| 10 | Oral Tradition Archive (Cyprus Research Centre), record no. 7225, Λεμ.-Aψ.2: Limassol—Apsiou, testimony: A. P., researcher: A. Pericleous, 16 December 2008. |

| 11 | Oral Tradition Archive (Cyprus Research Centre), record no. 6907, Λεμ. –Aκρουν.1: Limassol—Akrounta, testimony: A. G., researcher: A. Pericleous, 4 May 2007. |

| 12 | Oral Tradition Archive (Cyprus Research Centre), record no. 6789, Λεμ. –Μαθ.1: Limassol—Mathikoloni, testimony: A. G., researcher: D. Kalogirou, 8 February 2008. |

| 13 | Oral Tradition Archive (Cyprus Research Centre), record no. 6794, Λεμ. –Μαθ.6: Limassol—Mathikoloni, testimony: L. Ch., researcher: D. Kalogirou, 6 February 2008. |

| 14 | The icon was transferred to the new church within the same monastery on 23 April 2023. |

| 15 | Rock also points out that the English term “pilgrimage” is not an exact equivalent of proskinima (προσκύνημα) and has slightly different connotations—not so closely connected to journey, but instead to veneration: “Orthodox pilgrimage, then, may be interpreted as an effort to be in the presence of—or to achieve maximum proximity to—the holy” (Rock 2015, p. 48). This understanding of pilgrimage, discussed also by other scholars (Dubisch 1995, p. 46; Gothόni 1987, pp. 12–13), offers an intriguing set of ways to think about the form of the icon as creating a spatial sense of interior and exterior and offering a further dispensation of opening and revealing with the potential of showing a usually hidden icon on a given occasion or to a special audience that can both see and touch the icon. I have elaborated on this twofold role of the concept of pilgrimage in my paper “The Inverted Pilgrimages of the Panagia Amirou icon: Medieval Connections and the Formation of Community Identity”, presented at the conference The Arts and Rituals of Pilgrimage organized by NetMAR at the University of Cyprus (1–2 December 2022). I am grateful to the organizers and participants for their valuable comments and ensuing discussion. |

| 16 | For a brief summary of the most recurrent topoi used in legend as a reformulation of a holy site’s origins, see (Bacci 2019, p. 21). |

| 17 | More on this, see: (Meyer 2009, pp. 6–11). See also (Meyer and Verrips 2008). For more on the sensory approach and the recognition of the materiality of pictures and their capacity to engage the senses, see: (Meyer 2010, pp. 105–6). For the use of the concept of aesthetic formations within the Orthodox context, see: (Lackenby 2022). |

| 18 | The importance of making physically present what is otherwise unseen and in general insensate in the context of religion is addressed, among others, by Belting while describing the term “iconic presence”, in (Belting 2016). Nevertheless, he focuses mostly on the issues of representation and visual access. See also a short note on icons by Birgit Meyer in the same issue: (Meyer 2016). For more on the iconic presence, see the special issue of Convivium 6, no. 1, 2019, especially (Belting et al. 2019). |

References

- Ammerman, Nancy T. 2016. Lived Religion as an Emerging Field: An Assessment of its Contours and Frontiers. Nordic Journal of Religion and Society 29: 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammerman, Nancy T. 2021. Studying Lived Religion. Contexts and Practices. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. 2009. Ἱερά Μονή Παναγίας Ἀμιροῦς. Θεσσαλονίκη: Μέλισσα. [Google Scholar]

- Bacci, Michele. 2019. Site-Worship and the Iconopoietic Power of Kinetic Devotions. Convivium 6: 20–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belting, Hans, Ivan Foletti, and Martin F. Lešák. 2019. The Movement and the Experience of “Iconic Presence”: An Introduction. Convivium 6: 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belting, Hans. 2016. Iconic Presence. Images in Religious Traditions. Material Religion 12: 235–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boccardi, Giovanni. 2019. Authenticity in the Heritage Context: A Reflection Beyond the Nara Document. The Historic Environment: Policy & Practice 10: 4–18. [Google Scholar]

- Chhabra, Deepak. 2010. Back to the Past: As Sub-segment of Generation Y’s Perceptions of Authenticity. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 18: 793–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLanda, Manuel. 2006. A New Philosophy of Society. Assemblage Theory and Social Complexity. London: Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- Di Giovine, Michael A., and Josep-Maria Garcia-Fuentes. 2016. Sites of Pilgrimage, Sites of Heritage: An Exploratory Introduction. International Journal of Tourism Anthropology: Special Issue on Sites of Religion, Sites of Heritage: Exploring the Interface between Religion and Heritage in Tourist Destinations 5: 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Dubisch, Jill. 1995. In a Different Place. Pilgrimage, Gender, and Politics at a Greek Island Shrine. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Eade, John. 2020. The Invention of Sacred Places and Rituals: A Comparative Study of Pilgrimage. Religions 11: 649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamberi, Valentina. 2017. Incarnations: The Materiality of the Religious Gazes in Hindu and Byzantine Icons. Material Religion 13: 206–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilchrist, Roberta. 2020. Sacred Heritage. Monastic Archaeology, Identities, Beliefs. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin, Jack C. 1978. An Historical Toponymy of Cyprus. Nicosia: The Author. [Google Scholar]

- Gothόni, René. 1987. The revival on the Holy Mountain of Athos reconsidered. Byzantium and the North: Acta Byzantina Fennica 3: 7–18. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, Brian, Gregory J. Ashworth, and John E. Tunbridge. 2005. The Uses and Abuses of Heritage. In Heritage, Museums and Galleries: An Introductory Reader. Edited by Gerard Corsane. Abington: Rutledge, pp. 28–40. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths, Maureen, and Maximiliano E. Korstanje. 2022. Issues of Authenticity in Religious and Spiritual Tourism. In The Routledge Handbook of Religious and Spiritual Tourism. Edited by Daniel H. Olsen and Dallen J. Timothy. Abingdon: Routledge, pp. 276–87. [Google Scholar]

- Gunnis, Rupert. 1936. Historic Cyprus: A Guide to Its Towns and Villages, Monasteries and Castles. London: Methuen. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, David D. 1997. Introduction. In Lived Religion in America: Toward a History of Practice. Edited by David D. Hall. Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. vii–xiii. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, David. 2008. A History of Heritage. In Ashgate Research Companion to Heritage and Identity. Edited by Brian Graham and Peter Howard. London: Ashgate, pp. 19–36. [Google Scholar]

- Hazard, Sonia. 2013. The Material Turn in the Study of Religion. Religion and Society: Advances in Research 4: 58–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, Peter. 2003. Heritage: Management, Interpretation, Identity. London: Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- Isnart, Cyril, and Nathalie Cerezales. 2020. Introduction. In The Religious Heritage Complex: Legacy, Conservation, and Christianity. Edited by Cyril Isnart and Nathalie Cerezales. London: Bloomsbury Publishing, pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Jokilehto, Jukka. 1995. Authenticity: A General Framework for the Concept. In Nara Conference on Authenticity in Relation to the World Heritage Convention. Edited by Knut Einar Larsen. Paris: ICOMOS, pp. 17–34. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, Siân. 2009. Experiencing Authenticity at Heritage Sites: Some Implications for Heritage Management and Conservation. Conservation and Management of Archaeological Sites 11: 133–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, Siân. 2010. Negotiating Authentic Objects and Authentic Selves: Beyond the Deconstruction of Authenticity. Journal of Material Culture 15: 181–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallē, Thekla. 2019. Μήτηρ Θεοῦ ἡ Νέα Φανερωμένη—Mother of God the Nea (New) Phaneromeni. In Θρησκευτικές εικόνες της Κύπρου: κατάλογος εικόνων με χορηγό συντήρησης το Ίδρυμα A. Γ. Λεβέντη/Religious Icons of Cyprus: Catalogue of Icons Restored by the A. G. Leventis Foundation. Edited by Charalampos Bakirtzis. Nicosia: A. G. Leventis Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Karlström, Anna. 2015. Authenticity: Rhetorics of Preservation and the Experience of the Original. In Heritage Keywords: Rhetoric and Redescription in Cultural Heritage. Edited by Kathryn L. Samuels and Τrinidad Rico. Colorado: University Press, pp. 29–46. [Google Scholar]

- Knibbe, Kim, and Helena Kupari. 2020. Theorizing Lived Religion: Introduction. Journal of Contemporary Religion 35: 157–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knudsen, Britta Timm, and Anne Marit Waade, eds. 2010. Re-Investing Authenticity: Tourism, Place and Emotions. Bristol: Channel View Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Labadi, Sophia. 2010. World Heritage, Authenticity and Post-Authenticity: International and National Perspectives. In Heritage and Globalisation. Key Issues in Cultural Heritage Series. Edited by Sophia Labadi and Colin Long. London: Routledge, pp. 66–84. [Google Scholar]

- Lackenby, Nicholas. 2022. Paper Icons and Fasting Bodies: The Esthetic Formations of Serbian Orthodoxy. Material Religion 18: 391–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowenthal, David. 1995. Changing Criteria of Authenticity. In Nara Conference on Authenticity in Relation to the World Heritage Convention. Edited by Knut Einar Larsen. Paris: ICOMOS, pp. 121–35. [Google Scholar]

- Lowenthal, David. 1998. Fabricating Heritage. History and Memory 10: 5–24. [Google Scholar]

- McGuire, Meredith B. 2007. Embodied Practices: Negotiation and Resistance. In Everyday Religion: Observing Modern Religious Lives. Edited by Nancy T. Ammerman. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 187–200. [Google Scholar]

- McGuire, Meredith B. 2008. Lived Religion: Faith and Practice in Everyday Life. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- McGuire, Meredith B. 2016. Individual Sensory Experiences, Socialized Senses, and Everyday Lived Religion in Practice. Social Compass 63: 152–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, Birgit, and Jojada Verrips. 2008. Aesthetics. In Key Words in Religion, Media, and Culture. Edited by David Morgan. London: Routledge, pp. 20–30. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, Birgit, and Marleen de Witte. 2013. Heritage and the Sacred: Introduction. Material Religion 9: 274–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, Birgit. 2009. Introduction: From Imagined Communities to Aesthetic Formations: Religious Mediations, Sensational Forms, and Styles of Binding. In Aesthetic Formations: Media, Religion, and the Senses. Edited by Birgit Meyer. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, Birgit. 2010, ‘There Is a Spirit in that Image’: Mass-Produced Jesus Pictures and Protestant-Pentecostal Animation in Ghana. Comparative Studies in Society and History 52: 100–30.

- Meyer, Birgit. 2016. The Icon in Orthodox Christianity, Art History and Semiotics. Material Religion 12: 233–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Meyer, Birgit. 2019. Recycling the Christian Past. The Heritagization of Christianity and National Identity in the Netherlands. In Cultures, Citizenship and Human Rights. Edited by Rosemarie Buikema, Antoine Buyse and Antonius C. G. M. Robben. London: Routledge, pp. 64–88. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, David. 2010. The Material Culture of Lived Religion: Visuality and Embodiment. In Mind and Matter: Selected Papers of the Nordik 2009 Conference for Art Historians. Edited by Johanna Vakkari. Helsinki: Helsingfors, pp. 14–31. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, David. 2021. The Thing about Religion. An Introduction to the Material Study of Religions. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press. [Google Scholar]

- Niedźwiedź, Anna, and Kamila Baraniecka-Olszewska. 2020. Religious Heritages as Spatial Phenomena: Constructions, Experiences, and Selections. Anthropological Notebooks 26: 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Niedźwiedź, Anna. 2014. Competing Sacred Places: Making and Remaking of National Shrines in Contemporary Poland. In Pilgrimage, Politics and Place-Making in Eastern Europe: Crossing the Borders. Edited by John Eade and Mario Katić. Farnham: Ashgate, pp. 79–99. [Google Scholar]

- Niedźwiedź, Anna. 2015. Old and New Paths of Polish Pilgrimages. In International Perspectives on Pilgrimage Studies. Itineraries, Gaps and Obstacles. Edited by Dionigi Albera and John Eade. New York and London: Routledge, pp. 69–94. [Google Scholar]

- Papageōrgiou, Athanasios. 1985. Aμίρους Παναγίας μοναστήρι. In Μεγάλη Κυπριακή Εγκυκλοπαίδεια. Edited by Αντρός Παυλίδης. Λευκωσία: Aρκτίνος, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Pentcheva, Bissera V. 2006. The Performative Icon. The Art Bulletin 88: 631–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pentcheva, Bissera V. 2009. Moving Eyes: Surface and Shadow in the Byzantine Mixed-Media Relief Icon. RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics 55–56: 222–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pentcheva, Bissera V. 2010. The Sensual Icon: Space, Ritual, and the Senses in Byzantium. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rock, Stella. 2015. Touching the Holy: Orthodox Christian Pilgrimage Within Russia. In International Perspectives on Pilgrimage Studies. Itineraries, Gaps and Obstacles. Edited by Dionigi Albera and John Eade. New York and London: Routledge, pp. 47–68. [Google Scholar]

- Samuels, Kathryn. 2015. Heritage as Persuasion. In Heritage Keywords: Rhetoric and Redescription in Cultural Heritage. Edited by Kathryn Lafrenz Samuels and Trinidad Rico. Colorado: University Press, pp. 3–28. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman, Helaine. 2015. Heritage and Authenticity. In The Palgrave Handbook of Contemporary Heritage Research. Edited by Emma Waterton and Steve Watson. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 69–88. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Laurajane. 2006. Uses of Heritage. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Sophocleous, Sophocles. 2006. Icônes de Chypre: Diocèse de Limassol 12e–16e siècle. Nicosie: Centre du patrimoine culturel. [Google Scholar]

- Storrs, Ronald. 1939. Orientations. London: Nicholson & Watson. [Google Scholar]

- Sykoutrēs, Iōannēs. 1924. Μοναστήρια ἐν Κύπρῳ. Ἀμιροῦ. Κυπριακά Χρονικά 2: 79–85. [Google Scholar]

- Thouki, Alexis. 2022. Heritagization of Religious Sites: In Search of Visitor Agency and the Dialectics Underlying Heritage Planning Assemblages. International Journal of Heritage Studies 28: 1036–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Hemel, Ernst, Oscar Salemink, and Irene Stengs. 2022. Introduction. Management of Religion, Sacralization of Heritage. In Managing Sacralities: Competing and Converging Claims of Religious Heritage. Edited by Ernst van den Hemel, Oscar Salemink and Irene Stengs. New York: Berghahn Books, pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Vasilios Metropolitan of Constantia and Ammochostos, and Christina Kakkoura, eds. 2020. The Living Presence of the Theotokos in Cyprus through Her Icons [Exhibition Guide, 12 February—29 March 2020, Holy Bishopric of Constantia and Ammochostos “Saint Epifanios” Cultural Academy]. Paralimni-Agia Napa: Holy Bishopric of Constantia and Ammochostos. [Google Scholar]

- Vocotopoulos, Panayotis L. 2000. Composite Icons. In Greek Icons: Proceedings of the Symposium in Memory of Manolis Chatzidakis. Edited by Eva Haustein-Bartsch and Nano Chatzidakis. Athens-Recklinghausen: Benaki Museum, Ikonen-Museum Recklinghausen, pp. 5–10. [Google Scholar]

- Vocotopoulos, Panayotis L. 2002. Σύνθετες εἰκόνες. Μιὰ πρώτη καταγραφή. In Σῆμα Μενελάου Παρλαμᾶ. Edited by Lena Tzedakē. Hράκλειο: Ε.Κ.Ι.Μ, pp. 299–319. [Google Scholar]

- Von Droste, Bernd, and Ulf Bertilsson. 1995. Authenticity and World Heritage. In Nara Conference on Authenticity in Relation to the World Heritage Convention. Edited by Knut Einar Larsen. Paris: ICOMOS, pp. 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, Barbara. 2020. A Review of the Concept of Authenticity in Heritage, with Particular Reference to Historic Houses. Collections 16: 8–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaprzalska, Dorota. 2022. Asamblaż w asamblażu: O performatywności ikon kompozytowych w kontekście liturgicznym i muzealnym. Pamiętnik Teatralny 71: 27–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Yujie. 2012. Performing Heritage: Rethinking Authenticity in Tourism. Annals of Tourism Research 39: 1495–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zaprzalska, D. Religious Heritage Complex and Authenticity: Past and Present Assemblages of One Cypriot Icon. Religions 2023, 14, 1107. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14091107

Zaprzalska D. Religious Heritage Complex and Authenticity: Past and Present Assemblages of One Cypriot Icon. Religions. 2023; 14(9):1107. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14091107

Chicago/Turabian StyleZaprzalska, Dorota. 2023. "Religious Heritage Complex and Authenticity: Past and Present Assemblages of One Cypriot Icon" Religions 14, no. 9: 1107. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14091107

APA StyleZaprzalska, D. (2023). Religious Heritage Complex and Authenticity: Past and Present Assemblages of One Cypriot Icon. Religions, 14(9), 1107. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14091107