The Wall Painting of “Siddhārtha Descending on the Elephant” in Kizil Cave 110 †

Abstract

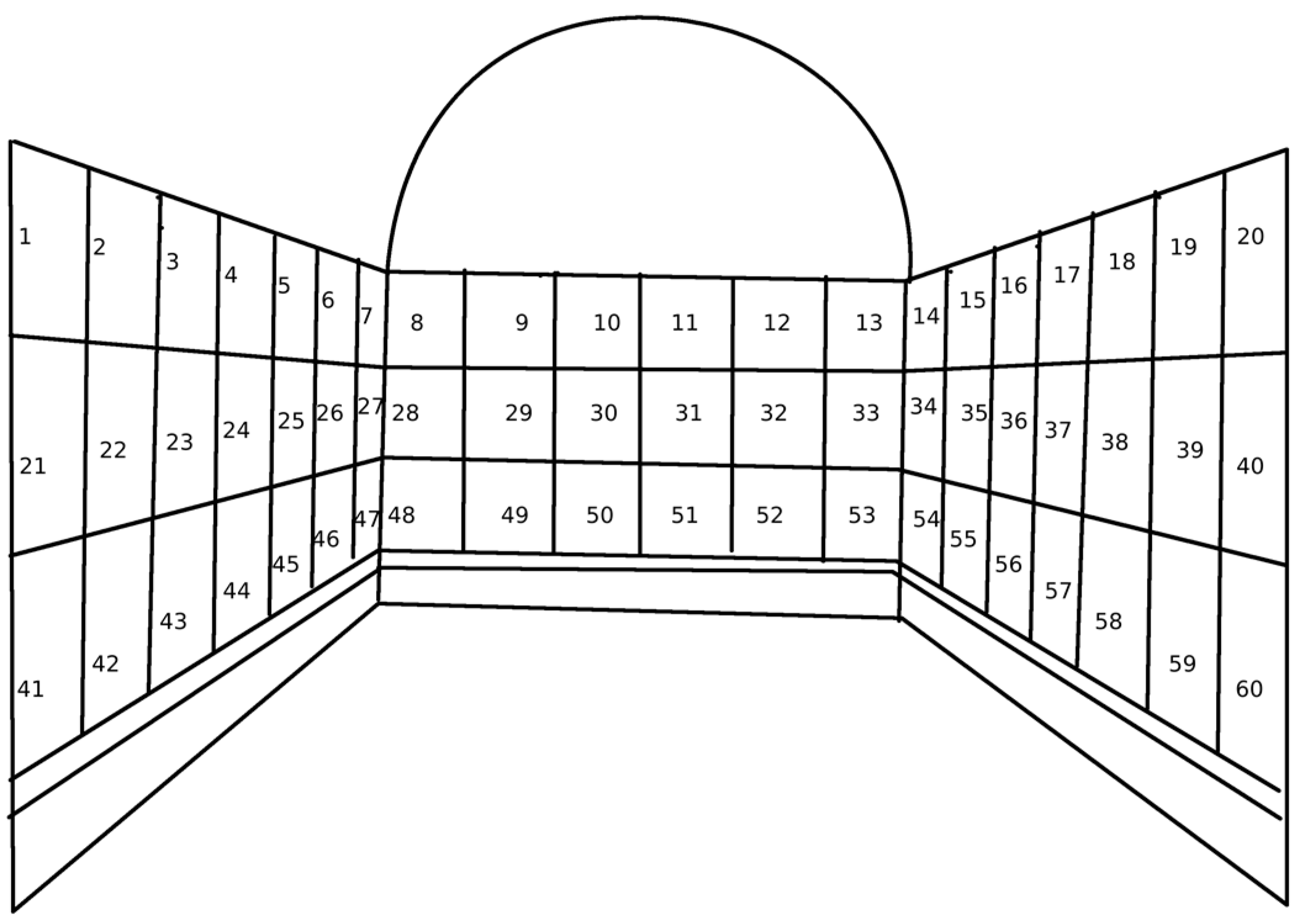

:1. Introduction

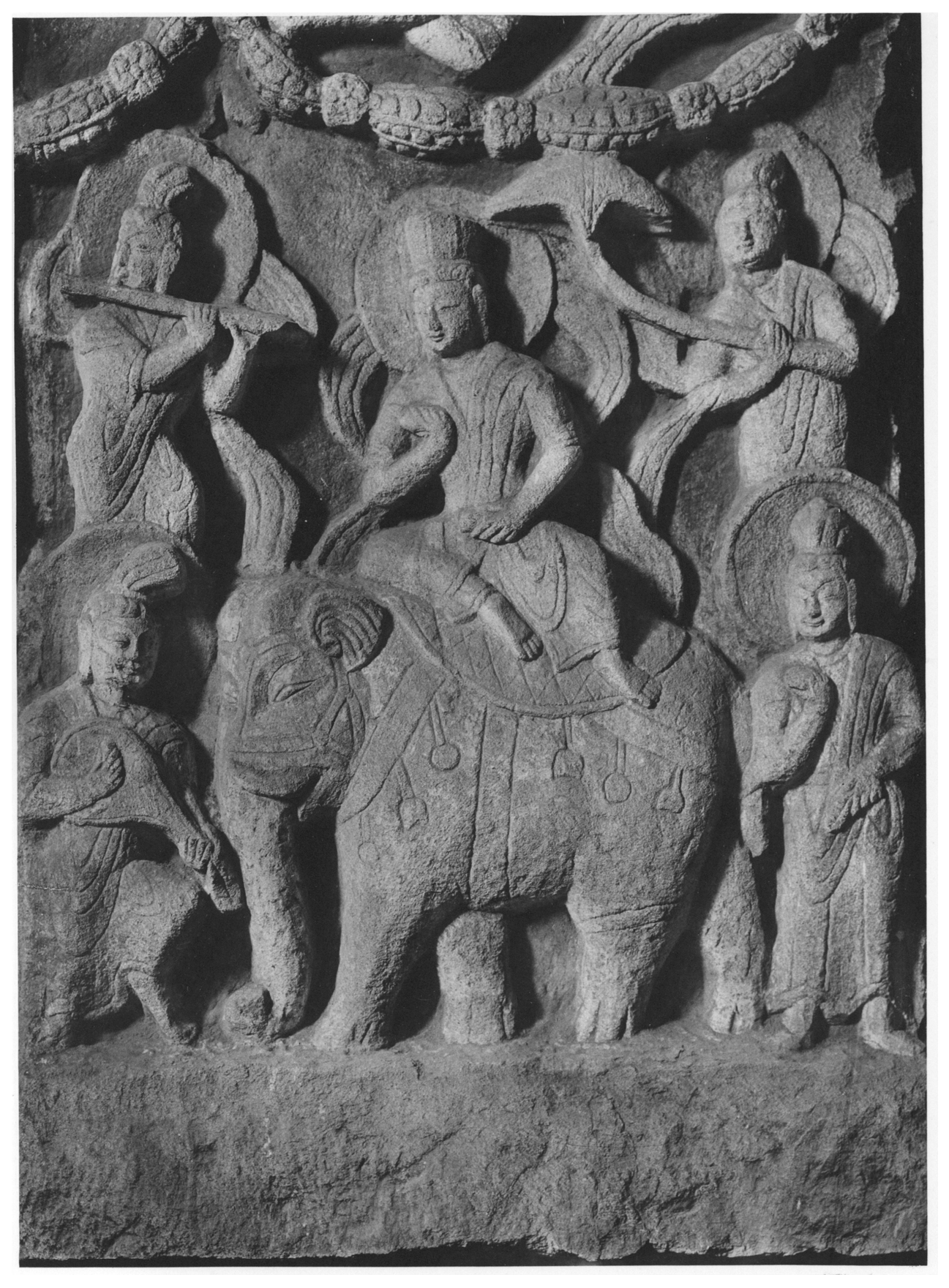

2. Siddhārtha Descending as an Elephant in Indian Art

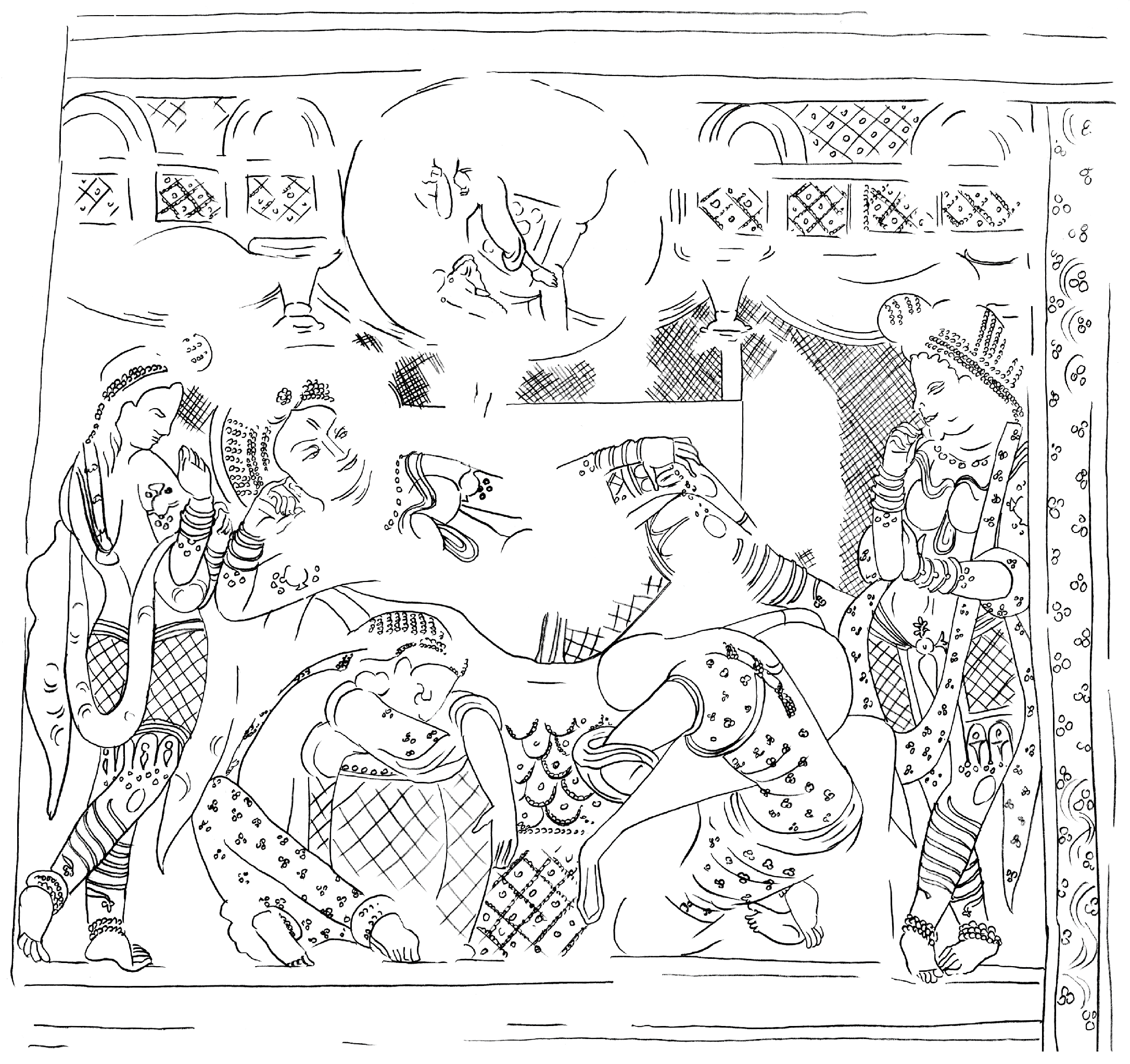

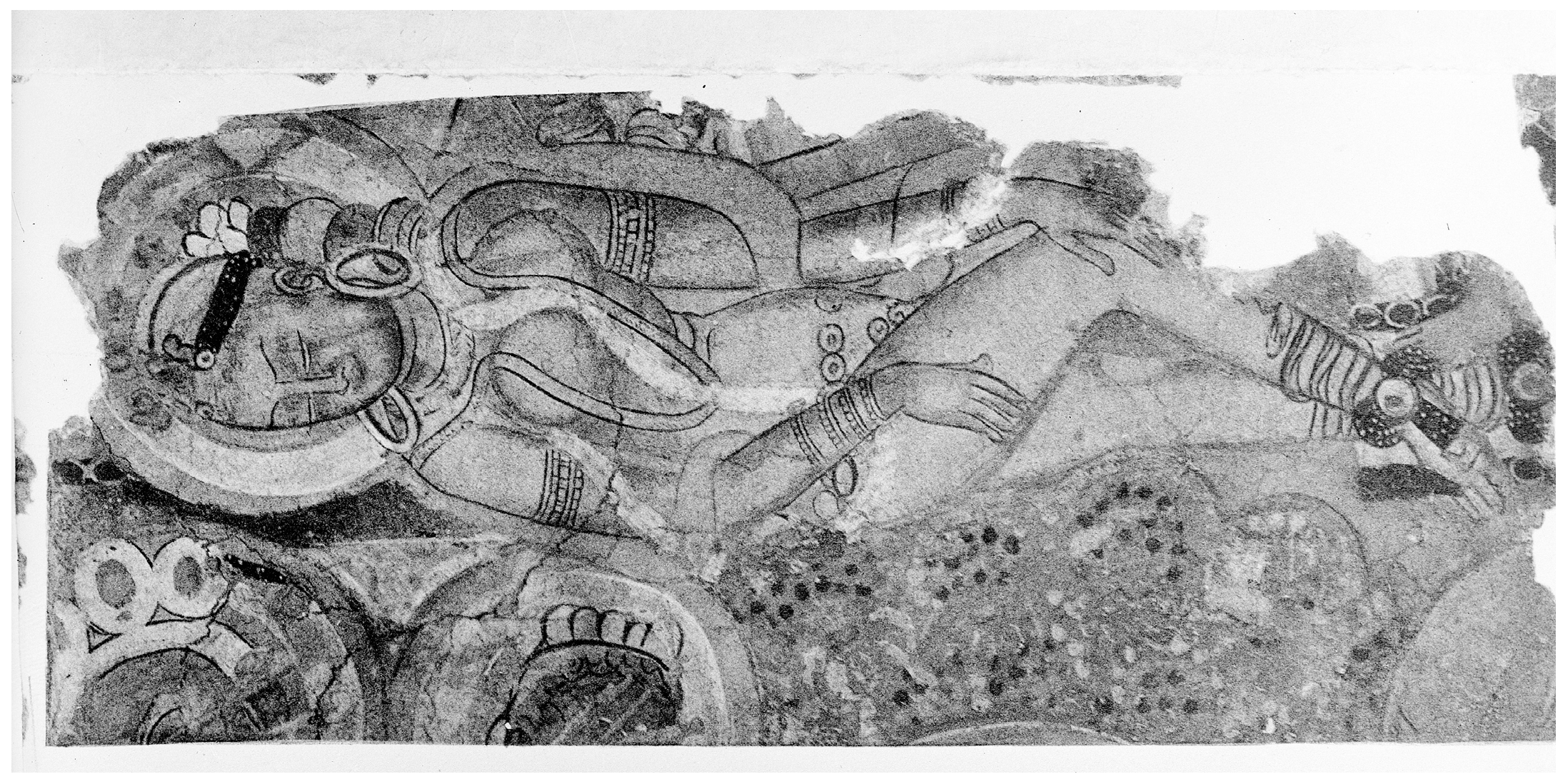

3. Siddhārtha Descending on the Elephant

Da zhidu lun, T no. 1509, 25: 418c28–29: “處胎成就”者,有人言:菩薩乘白象,與無量兜率諸天圍遶、恭敬、供養、侍從,入母胎. Concerning the accomplishment of the conception of the Bodhisatva, according to some, the Bodhisatva mounted on a white elephant, surrounded, venerated, respected, esteemed and served by innumerable Tuṣita gods, penetrated along with them into the womb of his mother.(Revised translation after Migme Chödrön 2001, vol. 5, p. 2024)

4. Hybrid Versions in Literature

5. Summary

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | The main relevant sources are listed as follows:

|

| 2 | For the references of major research, see (Foucher 1949, p. 38; Fischer 1980, pp. 229–95; Miyaji 1987, pp. 189–214; 1988, pp. 255–93; Schlingloff 2000, 2013, vol. 1, pp. 307–13, 376–79; Quagliotti 2009, pp. 349–416; Deeg 2010, pp. 93–128; Zin 2015, pp. 178–205). |

| 3 | For the references of western expeditions in Xinjiang, see (Dabbs 1963). |

| 4 | The assessment of the chronology of Kizil Cave 110 and its murals is a multifaceted undertaking. The methodology and supporting arguments employed in this regard are extensively expounded upon in the forthcoming doctoral dissertation of the present author to be submitted to Institute for South and Central Asian Studies, Leipzig University, 2023. As regards the epigraphical analysis of the Tocharian B inscriptions found in the cave and the hypothesis positing their dating to approximately 600 CE, I am grateful to Dr. Michaël Peyrot for his insights shared in his report Dating Kuchean: Usefulness and uselessness of chronological clues from the Tocharian B language, script and texts on 25 July 2018: Workshop “Archaeology and Vinaya Precepts”, Leipzig. |

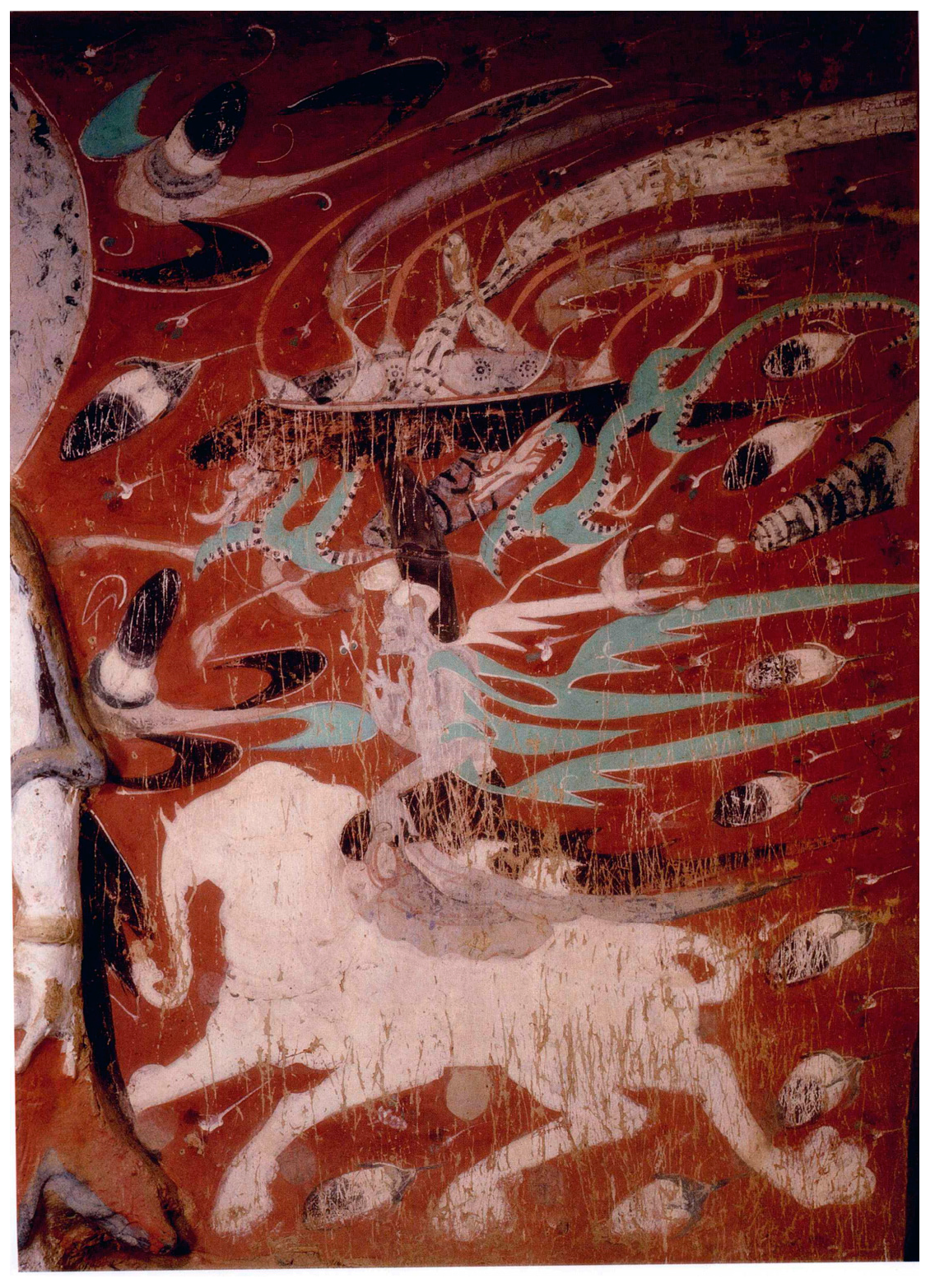

| 5 | (Grünwedel 1912, p. 118); in English (translated by the current author): “Dream of the Māyā. The companions of the sleeping Māyā are reminiscent of Indian prototypes. One figure from the picture is now in the museum. The white elephant is represented floating in the air above the lying Māyā but its image is badly destroyed”. He did not notice the boy figure riding the elephant. |

| 6 | Schmidt (2010, p. 843) deciphered the Toch. B verb ḵa[calñe] (meaning “put, set (down)”) in the inscription. Dr. Pan, Tao suggests a new revision of kä[tkalñe] “entering” in his private correspondence with the current author, 15 September 2019. Pan’s decipherment recalls the Bharhut inscribed caption bhgavato ūkramti “the conception of the Bhagavan” (Hultzsch 1885, nos. 10–11. Pali. okkami, Skt. upakrānti, see Lüders 1963, pp. 89–92), or the Sanskrit word avakrānti or avakram in the biographical literature of the Buddha. |

| 7 | The “pensive” posture named by art historians denotes a contemplative or in-trance state; for the pictorial references, see (Quagliotti 1996, pp. 97–115). |

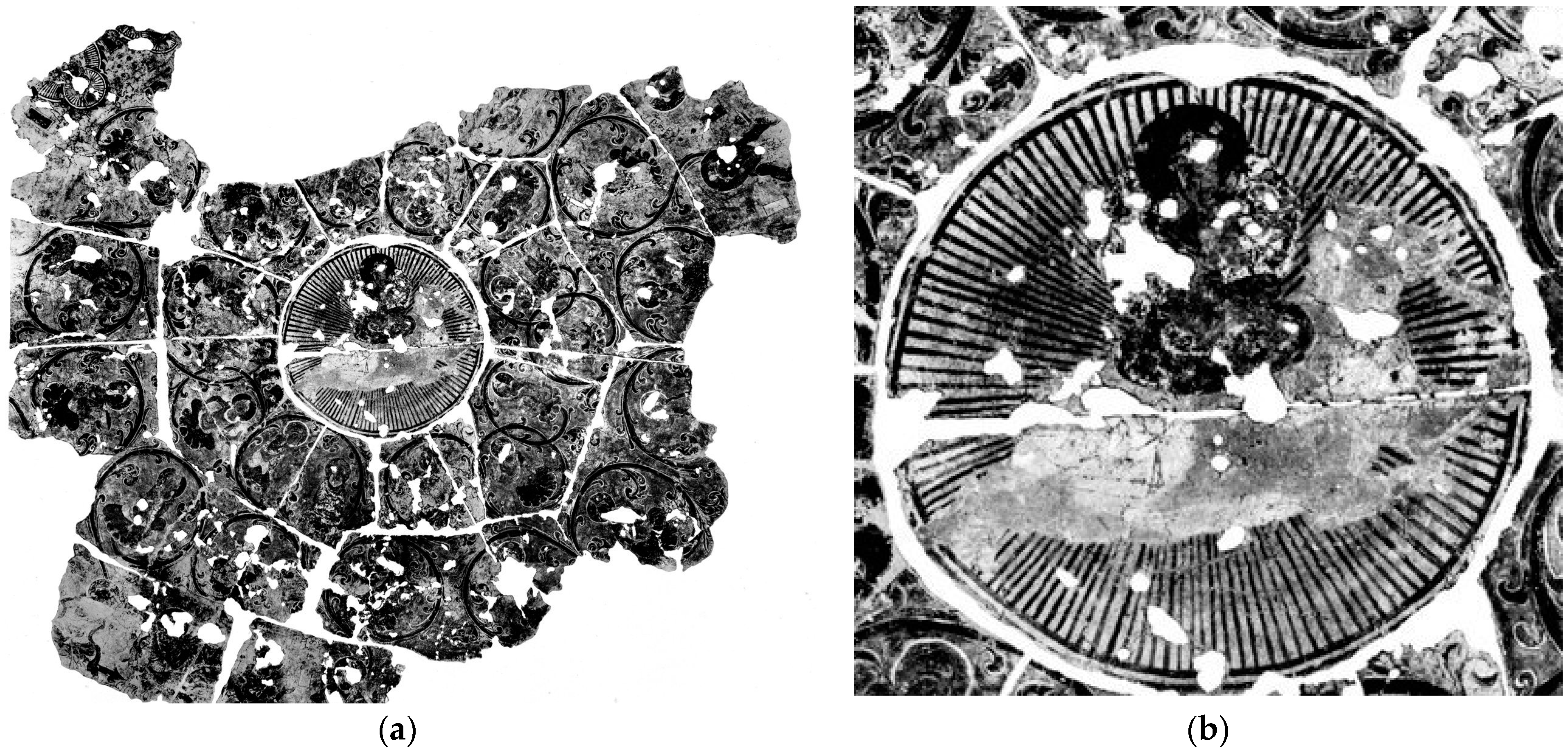

| 8 | The fragment III 8444a is nowadays housed in Museum für Asiatische Kunst, Berlin, cf. (Grünwedel 1920, II 90, Figure 4 (drawing), pls. 32, 33; Mural Paintings in Xinjiang of China: Kucha 2008, p. 39). The girl was identified by Grünwedel (1920, II 64) as Śrīmatī, the sister of Jīvaka and a devout Buddhist who fell in love with a monk and suddenly passed away, and the Buddha made a sermon in front of her corpse. |

| 9 | See (Lüders 1963, pl. 35; Schlingloff 2000, 2013, vol. 2, no. 64(2) [1] (drawing)). It is necessary to pay attention of the two fundamental traditions of Indian Buddhist art concerning the representations of the Buddha and Bodhisatvas, that is, “aniconic” and “iconic”. The former tradition avoids depicting the human form of the Buddha in physical or anthropomorphic form, but by means of symbols, and proceeding to it, the latter tradition comes to represent the human form of the Buddha or Bodhisatva, for the references, see (Seckel 1976; Seckel and Leisinger 2004). |

| 10 | The 13th Aśokan Edict from Girnar: … [sa]rvaśveto hasti sarvalokasukhāharo nāma, literally: “…the entirely white elephant bringing indeed happiness to the whole world”, see (Windisch 1908, p. 7; Hultzsch 1885, pp. 26–27). Schlingloff (2000, 2013, vol. 1, p. 311) quoted the common descriptions in the biographical literature of the Buddha, including Nidānakaṭhā: setavara-vāraṇo hutvā; MSV Saṅghabhedavastu: gajanidarśanena; Mahāvastu: gajarūpi ṣaḍdanto; Lalitavistara: pāṇḍuro gajapoto bhutvā ṣaḍdanta. In addition, scholars assume the two engraved elephant images at Dhauli and on the Saṃkīsa pillar in the 2nd century BCE are metaphorical representation of the descending Bodhisatva to earth, cf. (Verardi 1999–2000, p. 70; Quagliotti 2009, p. 404, fn. 2). |

| 11 | Lalitavistara, ed. 28: gajavaramahāpramāṇaḥ ṣaḍdanto hemajālasaṃkāśaḥ suruciraḥ suraktaśīrṣaḥ. Interestingly, the older Chinese translation, Puyao jing (普曜經) includes another episode with the tale about an elephant, a horse, and a rabbit crossing the river to stress the superiority of the elephant shape, which sheds light on the Mahāyana Buddhism, T no. 186, 3: 488b17–26. “又問:“以何形往?”答曰:“象形第一。六牙白象頭首微妙,威神巍巍、形像姝好,梵典所載其為然矣,緣是顯示三十二相。所以者何?世有三獸:一、兔,二、馬,三、白象。兔之渡水,趣自渡耳;馬雖差猛,猶不知水之深淺也;白象之渡盡其源底。” Translation by the present author: “(It was) replied, ‘Of all, the elephant shape is most superior. The head of the six-tusk elephant is so fine and beautiful, full with splendour and majesty, extraordinary in the shape and form, as recorded in Brahmanical scriptures. The elephant shape demonstrates the 32 lakṣanas.’ Why would one say so? As for the (following) three animals in the world: the first is a rabbit, the second is a horse and the third is a white elephant; on the occasion of crossing the river, the rabbit can only deliver itself to the other bank; the horse is powerful but it does not know about the depth of the water; only the white elephant can cross by completely touching the river bed.” |

| 12 | Faxian zhuan jiaozhu (Zhang 2008, p. 70): 白淨王故宮處,作太子母形像,乃太子乘白象入母胎時. Translation by the present author: “At the ancient palace of King Śuddhodana, a statue of the mother of the prince was erected, which indicated the moment of the prince riding on an elephant and entering his mother’s womb.” |

| 13 | The first analysis of the pictorial detail was published in Saiiki Bijutsuten edited for the exhibition “Central Asian Art from the Museum of Indian Art, Berlin” held at Tokyo Kokuritsu Hakubutsukan, 2 April–12 May 1991; see also (Nakagawara 1994, p. 26; Schlingloff 2000, 2013, vol. 1, p. 313; Li 2004, pp. 89–90). |

| 14 | It is noteworthy that later on in the early 6th century, Yungang Cave 37 provided a local development of a human figure riding the galloping elephant and carrying the infant Bodhisatva in his arms as he brings the Bodhisatva down to the future mother, which is an innovation beyond textual sources. For references to the picture, see (Yun-Kang 1951–1956, vol. 6, p. 15, pl. 74b; Li 2004, Figure 6). For more examples from Northern China, see (Li 2004, pp. 77–95). |

| 15 | Deeg (2010, p. 114) argued that the earliest Chinese scriptures containing such recounts (T no. 184, T no. 185) corresponded with the late Han Dynasty; while contemporary mural depictions of a human figure on a white elephant in tombs already existed in Shandong Province and Inner Mongolia, which are related to the conception of the Buddha. However, in the beginning phase of Chinese Buddhism, the Chinese natives absorbed only unsystematic Buddhist elements into their funerary customs, which disobeyed the orthodox Buddhist doctrines, and such imagery, deprived of the necessary story-telling context of the Buddha’s life, was more likely painted to cater to native funerary beliefs of ascending to heaven. |

| 16 | Hameed (2015) provides a corpus of miniature portable shrines from Gandhāra and Kashmir with his own numbering. The two examples containing the conception episode are the shrine cat. no. 5 housed in The Metropolitan Museum of Art and the ivory diptych cat. no. 17 found in Yulin and housed in National Museum of China, Beijing (acc. no. 1952 ICL). The latter scene shows Queen Māyā sleeping in bed, the maiden crouching on ground and two deities, with damaged heads, witnessing the event with palms held together in añjalī. The elephant is absent due to the limited space. However, the whole diptych, when closed, depicts the form of a man riding the elephant; this has been identified by Yan (1955, pp. 80–88) as the descending Bodhisatva riding the elephant. The idea was later repudiated by Soper who argued that the carriage elephant is loaded with a reliquary, cf. (Soper 1965, p. 222; Rowan 1985, pp. 251–304). |

| 17 | In the mural décor of Kumtura Cave 16, main chamber, southern wall, there is a depiction of the Bodhisatva riding on a six-tusked white elephant, heading for a roofed building, but it belongs to a Mahāyānist paradise illustration of wall paintings in the Tang Manner of the so-called Third Style, rather than the narrative of the Buddha’s life; nor does it represent Mañjuśrī, cf. (Liu 2017, pp. 155–57). |

| 18 | The Book of Zambasta gives an account of the descent of the Bodhisatva: “Because of this great compassion, he at once gave up life with the gods among the Tuṣita-gods. Then, in the form of an elephant-foal, he then filled the whole world with light. He made worthy of the Śākya-race those who were Ikṣvākus, his father Śuddhodana, his mother Queen Māyā. As a sunbeam (enters) a room, so by night he entered the side of Queen Maya on the right. Why did he appear in the form of a white elephant? So that wise men knew him before. With every excellence, he is pure, well tamed. Since he has white tusks, pure, he will practise śila. He has six tusks because he will proclaim the six great, good anusmṛtis, which remove all kleśas. Those arose great light in all directions: he will remove all dark, black ignorance. With his trunk, he touched his mother’s right side: he will instruct all other beings in pradakṣiṇā.” (Translation by Emmerick 1968, pp. 378–79). |

| 19 | The craftsmen working for the Kumtura Caves must have known about the tale, for they painted the three animals together on the zenith of the vaulted ceiling as part of the “city of nirvāṇa” iconography in Kumtura Cave 28, cf. (Yang 2017, pp. 76–86; Konczak-Nagel 2020, pp. 49–51). |

| 20 | For an overview of scholarly opinion, see (Zhou 2000, pp. 155–65). Moreover, Chang (2020) has proven certain exclusive connections between some jākata representations in Kuchean murals and the text T no. 1509. |

| 21 | Guanfo sanmei hai jing, T no. 643, 15: 667b11–12: 一一日光有金色象,菩薩化乘,乘象之時,萬億瑞應不可宣說. Translation by the current author: “In every ray of the sunlight, there is an elephant of the golden color. When the Bodhisatva shows himself as descending on the elephant, there are thousands of billions of auspicious miracles beyond description.” |

| 22 | Fo shuo shi’er you jing, T no. 195, was translated by Kālodaka迦留陀伽 in 392 CE and speculated to be apocryphal; for the analysis of the mixed identity of the text, cf. (Pu 2019, pp. 93–121). |

| 23 | Fo ben xing jing, T no. 193 was traditionally ascribed to Baoyun 寶雲 (died in 449 CE), who was a fellow pilgrim monk with Faxian 法顯 to India. Radich (2019, pp. 229–79) checked the phraseology of T no. 193 and suggested the translation should be in a tightly interrelated group with T no. 7, T no. 189 and T no. 192 established in the 5th century. The English title Vajrapāni-Buddhacarita of T no. 193 is adopted from the forthcoming collaboration essay of Pan/Loukota, who gave their oral presentation on the 34th DOT (Deutscher Orientalistentag, Freie Universität Berlin, 12–17 September), and I am grateful for the kind information they provided. |

| 24 | Fo benxing jing, T no. 193, 4: 57c24–58a2: 菩薩乘象王,如日照白雲;諸天鼓樂舞,普雨雜色花。日精之明珠,光照耀王宮;降神下生時,現瑞甚微妙. Translation by Deeg (2010, p. 112): “…(he) had his vehicle appear to be let everybody know: (it is) an elephant white as a silver mountain. The bodhisatva is sitting on the king of the elephants (who) looks like a white cloud upon which the sun is shining. All gods (deva) beat the drum, performed music and danced; a rain of multicoloured flowers spread; like a bright pearl of the essence of the sun he illuminated the royal palace. When he descends to be born (i.e.,: conceived) miraculously, magnificent omens appear”. |

| 25 | Fo benxing jing, T no. 193, 4: 58a11–14: 妙后寐寤尋憶夢,諸根寂然喜踊躍;舉目四向遍察視,玉顏怡悅蓮華色。即啟王曰:唯願聽,夢中所見甚吉祥:大白象王有六牙,忽然來至在我前. Translation by the present author: “Queen Māyā woke up and remembered the dream, feeling pacified and joyful. She looked around, with the beautiful and delightful face of the lotus colour, and spoke to the king: ‘May thou listen to me, I had a dream with the auspicious vision that a great, white elephant king with six tusks instantly came to me’”. |

| 26 | Zhongxu mohedi Jing, T no. 191, is highly regarded due to the high-quality translation and its strong affinities to the Mūlasarvāstivādin School. The translator Faxian (Dharmabhadra 法賢, also named Tianxizai 天息災) from Kashmir was ordained in Nalada Temple in India, and came to the capital of Northern Song Dynasty in China in 982 CE; there he took charge of the translation work until his death in the year of 1000 CE; cf. (Lin 2007, pp. 43–47). |

| 27 | As summarized in Ji et al. (1998), the work is not preserved in any Indian or Chinese language and it has three parallel versions of the provenance in Tarim Basin, with one Tocharian A script from Karashar (roughly in the 7th or 8th Centuries) and two Old-Uyghur scripts separately from Sangim (roughly in the 8th or 9th centuries) and from Hami. The Hami Maitrisimit written in 1069 CE as stated in its colophon has the longest corpus in preservation; for a whole edition, see Geng (2008). Compared to the fragmentary Karashar and Sangim parallels, the Hami Maitrisimit provides a lengthy account in terms of the life story of Maitreya Buddha, despite here being unavoidable lacuna due to the damage. |

| 28 | (Geng et al. 1988, pp. 322, 341; Geng 2008, p. 283). Prof. Peter Zieme suggests to give a new reading and interpretation concerning the passage of four dreams in the private correspondences with the present author (6 January 2022), and the forthcoming academic fruit is awaited. |

| 29 | Hami Maitrisimit, ch. 11, folio 3a24–28, transliteration and the German translation in (Geng et al. 1988, p. 341, fn. 32): “Diejenigen Frauen, die träumen, daß im Traum ein Jüngling einen Elefanten besteigt, diese Frauen werden einen Sohn gebären, der sicherlich ein Buddha-cakravartin-König wird”; I attempts to give the English translation here: “Those women who dream that a boy in the dream mounts an elephant, they will give birth to a son who will surely become a Buddha-cakravartin king”. For the emendation in Chinese translation, see (Geng 2008, pp. 283, 314). |

References

Primary Sources

- Pali:

- Nidānakathā, in: Jātaka, ed. Fausbøll, V. (1877), vol. 1, London: 1–94; transl: Jayawickrama, N.A. (1990) The Story of Gotama Buddha, The N° of the Jātakaṭṭhakathā. Oxford.

- Sanskrit:

- Buddhacarita. The Buddhacarita or Acts of the Buddha (Cantos I to XIV), Edited and Translated by Edward Hamilton Johnston. transl. from the original Sanskrit supplemented by the Tibetan version, Lahore 1936 (repr. New Delhi 1972). Johnston, Edward Hamilton, The Buddha’s Mission and Last Journey, Buddhacarita, Cantos XV to XXVIII transl. from Tibetan and Chinese versions. Acta Orientalia 15. Leiden 1937, pp. 26–62, 85–111, 231–92 (repr. both parts, Delhi 1984).

- Lalitavistara, ed. 2001. Lefmann, Salomon. Lalita Vistara. Leben und Lehre des Çâkya-Buddha. Textausgabe mit Varianten-, Metren- und Wörterverzeichnis. Halle an der Saale: Verlag der Buchhandlung des Waisenhauses 1902, 1908; translation with Notes, Goswami, Bijoya, Kolkata he Asiatic Society, 2 vols.

- Mahāvastu, ed. Senart, Émile. Le Mahāvastu: Mahavāstu avadānaṃ, texte sanscrit publié pour la première fois et accompagné d’introductions et d’un commentaire. 3 vols. Paris: Imprimerie nationale, 1882–1997; transl. Jones, John James, The Mahāvastu. London: Lizac, 1949–1956, Sacred Books of the Buddhists 16, 18, 19.

- Mūlasarvāstivādavinaya, Saṅghabhedavastu, ed. Gnoli, Raniero, The Gilgit Manuscript of the Saṅghabhedavastu, Being the 17th and Last Section of the Vinaya of the Mūlasarvāstivādin. 2 vols. Rome 1977–1978.

- Saundarananda, ed. Johnston, Edward Hamilton, The Saundarananda of Aśvaghoṣa. London, 1928; transl. Johnston, Edward Hamilton, The Saundarananda or Nanda the Fair, translated from the original Sanskrit of Aśvaghoṣa. Oxford 1932.

- Chinese:

- T = Taishō shinshū daizōkyō (see 3. Secondary Sources, Takakusu & Watanabe, et al.)

- Takakusu Junjirō 高楠順次郎, and Watanabe Kaigyoku 渡邊海旭, eds. 1924–1932. Taishō shinshū daizōkyō 大正新修大藏經 [Buddhist Canon Compiled under the Taishō Era (1912–1926)]. 100 vols. Tokyo: Taishō issaikyō kankōkai 大正一切經刊行會.

- Xiuxing benqi jing 修行本起經 [Cāryanidāna]. Transl. Mahābala 竺大力 and Kang Mengxiang 康孟詳 in 197 CE. T no. 184, vol. 3, 461a–472b.

- Taizi ruiying benqi jing 太子瑞應本起經 [Sūtra on the Origin of the Lucky Fulfilment of the Crown-Prince] Transl. Zhi Qian 支謙 between 223–253 CE. T no. 185, vol. 3, 472c–483a.

- Puyao jing 普曜經 [Skt. Lalitavistara]. Transl. Dharmarakṣa竺法護 in 308 CE. T no. 186, vol. 3, 483a–538a.

- Fangguang da zhuangyan jing 方廣大莊嚴經 [Skt. Lalitavistara]. Transl. Divākara 地婆訶羅 in 683 CE. T no. 187, vol. 3, 539a–617b.

- Guoqu xianzai yinguo jing 過去現在因果經 [Scripture on Past and Present Causes and Effects]. Transl. Guṇabhadra 求那跋陀羅 between 435–443 CE. T no. 189, vol. 3, 620c–653b.

- Fo benxing jijing 佛本行集經 [Skt. Abhiniṣkramaṇasūtra]. Transl. Jñānagupta 闍那崛多 between 587–591 CE. T no. 190, vol. 3, 655a–932a.

- Zhongxu mohedi jing 眾許摩訶帝經 [Skt. Mahāsammatarājasūtra]. Transl. Faxian 法賢 in 989 CE. T no. 191, vol. 3, 932a–975c.

- Fo benxing jing 佛本行經 [Skt. *Vajrapāni-Buddhacarita]. Transl. Baoyun 寶雲 between 423–453 CE. T no. 193, vol. 4, 54a–115b.

- Foshuo shi’er youjing jing 佛說十二遊經 [Sutra of the Twelve-year Travel of the Buddha]. Transl. Kālodaka 迦留陀伽 in 392 CE. T no. 195, vol. 4, 146a–147b.

- Guan fo sanmei hai jing 觀佛三昧海經 [Sutra on the Ocean-Like Samādhi of the Visualization of the Buddha]. Transl. Buddhabhadra 佛陀跋陀羅 between 420–423 CE. T no. 643, vol. 15, 645c–697a.

- Da zhidu lun 大智度論 [Skt. Mahāprajñāpāramitopadeśa]. Transl. Kumārajīva 鳩摩羅什 between 402–405 CE. T no. 1509, vol. 25, 57a–756c. French transl.(Lamotte 1944–1980) Lamotte, Etienne. Le traité de la grande vertu de sagesse de Nāgārjuna: Mahāprajñāpāramitāśāstra, 5 vols. Louvain: Institute Orientaliste, 1944–1980. English transl. (Migme Chödrön 2001) Gelongma Karma Migme Chödrön, The Treatise on the Great Virtue of Wisdom of Nagarjuna (Mahāprajñāpāramitāśāstra), 5 vols, 2001. Available online: https://www.wisdomlib.org/buddhism/book/maha-prajnaparamita-sastra (last accessed on 14 March 2023).

- Gaoseng Faxian zhuan 高僧法顯傳 [Record (on the Journey) of Faxian ] By. 法顯 Faxian in 405 CE), T no. 2085, vol. 51, pp. 857a–866c.= Zhang, Xun 章巽 (ed.), Faxian zhuan jiaozhu 法顯傳校注 [Annotations on Biography of Faxian the Venerable]. 北京: 中華書局 Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 2008.

- Khotanese:

- The Book of Zambasta: A Khotanese Poem on Buddhism. 1968. Edited and Translated by Ronald E. Emmerick. London: Oxford University Press.

Secondary Sources

- Andrews, Frederick H. 1948. Wall Paintings from Ancient Shrines in Central Asia, Recovered by Sir Aurel Stein. 2 vols. London: Oxford University Press, Published online, last access on 2023.5.17, NII “Digital Silk Road”/Toyo Bunko. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrendt, Kurt A. 2007. The Art of Gandhara in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Wen-ling 張文玲. 2020. Feststellung der literarischen Vorlagen der jātaka Darstellungen in Höhle 17 in Kizil. Ph.D. dissertation, Freie Universität, Berlin, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- Coomaraswamy, Ananda Kentish Muthu. 1928. Yaksas. Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections. Washington, DC: The Smithsonian Institution, vol. 80. [Google Scholar]

- Coomaraswamy, Ananda Kentish Muthu. 1965. History of Indian and Indonesian Art. New York: Dover. [Google Scholar]

- Dabbs, Jack Autrey. 1963. History of the Discovery and Exploration of Chinese Turkestan. The Hague: Mouton. [Google Scholar]

- Deeg, Max. 2010. Why Is the Buddha Riding on an Elephant? The Bodhisatva’s Conception and the Change of Motive. In The Birth of the Buddha: Proceedings of the Seminar Held in Lumbini, Nepal, October 2004. Edited by Christoph Cueppers, Max Deeg and Hubert Durt. LIRI Seminar Proceedings Series; Lumbini: Lumbini International Research Institute, vol. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Dunhuang shiku quanji. 1999–2004. Dunhuang shiku quanji 敦煌石窟全集 [Corpora Catalogue of Dunhuang Grotto Caves]. 26 vols. Edited by Dunhuang yanjiu yuan敦煌研究院. Hongkong 香港: Commerial Press 商務印書館. [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson, James. 1873. Tree and Serpent Worship. London: India Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, Klaus. 1980. Zu erzählenden Gandhara-Reliefs. Mit einem Exkurs über den Hengst Kathaka. Allgemeine und Vergleichende Archäologie 2: 229–95. [Google Scholar]

- Foucher, Alfred. 1949. La vie du Bouddha, d’après les textes et les monuments de l’Inde. Paris: Payot. [Google Scholar]

- Geng, Shimin 耿世民, Hans-Joachim Klimkeit, and Jens Peter Laut. 1988. Das Erscheinen des Bodhisatva: Das 11. Kapitel der Hami-Handschrift der Maitrisimit. Altorientalische Forschungen 15: 315–66. [Google Scholar]

- Geng, Shimin 耿世民. 2008. Huihu wen hami ben <mile huijianji> yanjiu 回鹘文哈密本《弥勒会见记》研究/Study on the Uigur Maitrisimit (Hami Version). Beijing 北京: Zhongyang Minzu Daxue Chubanshe 中央民族大学出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Grünwedel, Albert. 1912. Altbuddhistische Kultstätten in Chinesisch-Turkistan: Königlich Preussische Turfan Expeditionen. Berlin: Reimer. [Google Scholar]

- Grünwedel, Albert. 1920. Alt-Kutscha: Archäologische und Religionsgeschichtliche Forschungen an Tempera-Gemälden aus Buddhistischen Höhlen der ersten acht Jahrhunderte nach Christi Geburt. Berlin: Elsner. [Google Scholar]

- Hameed, Muhammad. 2015. Miniature Portable Shrines from Gandhara and Kashmir. Ph.D. dissertation, Freie Universität, Berlin, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- Hultzsch, Eugen. 1885. The Sunga inscription of the Barhut stupa. Indian Antiquary XIV: 45–48. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, Xianlin 季羡林, Werner Winter, and Georges-Jean Pinault. 1998. Fragments of the Tocharian A Maitreyasamiti-Nāṭaka of the Xinjiang Museum, China. Berlin and New York: Mouton de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Kijiru, Senbutsudō (Tan Shutong) 谭树桐, and Chunyang An 安春阳, eds. 1981. Shinkyō no hekiga: Kijiru senbutsudō 新疆の壁画:キジル千仏洞 Murals for Xinjiang: The Thousand-Buddha Caves at Kizil. 2 vols. Kyoto: Binobi. [Google Scholar]

- Kizil Grottoes = Chūgoku sekkutsu: Kijiru sekkutsu 中国石窟: キジル石窟/The Grotto Art of China: The Kizil Grottoes. 1983–1985. 3 vols. Shinkyō Uiguru jichiku bunbutsu kanri iinkai/Haijō ken Kijiru senbutsudō bunbutsu hokanjo新疆ウイグル自治区文物管理委員会/拝城県キジル千仏洞文物保管所, ed. Tokyo: Heibonsha. [Google Scholar]

- Knox, Robert. 1992. Amaravati: Buddhist Sculpture from the Great Stupa. London: British Museum Publisher. [Google Scholar]

- Konczak-Nagel, Ines. 2020. Representations of Architecture and Architectural Elements in the Wall Paintings of Kucha. In Leipzig Kucha Studies Volume 1: Essays and Studies in the Art of Kucha. Edited by Eli Franco and Monika Zin. New Delhi: Dev Publishers & Distributors, pp. 11–106. [Google Scholar]

- Le Coq, Albert von. 1924. Die buddhistische Spätantike in Mittelasien. Ergebnisse der Kgl.-Preussischen Turfan-Expeditionen, III, Die Wandmalereien. Berlin: Reimer und Vohsen. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Jingjie 李静杰. 1996. Zaoxiangbei bensheng benxing gushi diaoke 造像碑佛本生本行故事雕刻 [Carvings of Buddha’s life and Jātaka Stories on Statue Steles]. Palace Museum Journal 故宫博物院院刊 4: 64–83. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Jingjie 李静杰. 2004. Beichao fozhuan diaoke suojian fojiao meishu de dongfanghua guocheng---yi dansheng qianhou de changmian wei zhongxin 北朝佛传雕刻所见佛教美术的东方化过程—以诞生前后的场面为中心 The Process of Chinese Acculturation in the Buddhist Fine Arts as Seen from Northern Dynasties’ Carvings in Stone Recounting Buddhist Tales; A Focus on Pre-Natal and Post Natal Scenes. Palace Museum Journal 故宫博物院院刊 4: 76–95. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Shundao 林顺道. 2007. Song mingjiao dashi Faxian kao宋明教大师法贤考. Zhejiang xuekan 浙江学刊 2: 43–47. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Tao 刘韬. 2017. Tang yu Huihu shiqi qiuci shiku bihua yanjiu 唐与回鹘时期龟兹石窟壁画研究 [Researches on Murals of Kucha Grottoes during Tang Dynasty and Old-Uyghur Period]. Beijing 北京: Wenwu chubanshe 文物出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Lüders, Heinrich. 1963. Bharhut Inscriptions = Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum 2.2. Ootacamund: Government epigraphist for India. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, John H., and Alfred Foucher. 1940. The Monuments of Sāñchī. 3 vols. Calcutta: Government of India Press. [Google Scholar]

- Miyaji, Akira 宮治昭. 1987. Indo butsuden zuzō no kenkyū (1) ‘tosotsu tenjō no bosatsu’ ‘ hakuzō kōka’ インド仏伝図像の研究(一)-「兜率天上の菩薩」「白象降下」-[Survey on Indian Iconography of Buddha’s life I: ‘The Bodhisatva on Tuṣita Heaven’ ‘Descent of the White Elephant’]. Nagoya daigaku bungaku bu kenkyū ronshū 名古屋大学文学部研究論集 99: 189–214. [Google Scholar]

- Miyaji, Akira 宮治昭. 1988. Indo butsuden zuzō no kenkyū (2) taku hara reimu インド仏伝図像の研究-2-託胎霊夢-[A Survey on Indian Iconography of Buddha’s life II: ‘Dream of Conception’]. Nagoya daigaku bungaku bu kenkyū ronshū 名古屋大学文学部研究論集 102: 255–93. [Google Scholar]

- Mural Paintings in Xinjiang of China: Kucha = Xinjiang Quici Shiku yanjiusuo新疆龟兹石窟研究所, ed. 2008. Zhongguo Xinjiang bihua: Qiuci 中国新疆壁画:龟兹 Mural Paintings in Xinjiang of China: Quici [Kucha]. Urumqi: Xinjiang Meishu Sheying Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawara, Ikuko 中川原育子. 1994. Kizil dai 110 kutsu (Kaidankutsu) no Butsudenzu ni tsuite キジル第110窟(階段窟)の仏伝図について [On the murals about the life of Buddha at Cave 110 (Treppenhöhle) in Kizil]. Mikkyō Zuzō 密教図像 13: 19–38. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, Tao 潘涛, and Diego Loukota. 2022. A Forgotten Life of the Buddha: The *Vajrapāṇi-Buddhacarita” in its Tocharian B and Chinese Versions. Paper presented at the 34th DOT (Deutscher Orientalistentag), Freie Universität, Berlin, Germany, September 12–17. [Google Scholar]

- Pu, Chengzhong 蒲成忠. 2019. Some Research Notes on Sutra of the Twelve [-year] Travel [of the Buddha] (十二遊經). International Journal of Buddhist Thought and Culture 29: 93–121. [Google Scholar]

- Quagliotti, Anna Maria. 1996. Pensive Bodhisatvas on ‘Narrative’ Gandharan Reliefs. A Note on a Recent Study and Related Problems. East and West 46: 97–115. [Google Scholar]

- Quagliotti, Anna Maria. 2009. Māyā’s Dream from India to Southeast Aisa. In The Indian Night: Sleep and Dreams in Indian Culture. Edited by Claudine Bautze-Picron. New Delhi: Rupa & Co., pp. 349–416. [Google Scholar]

- Radich, Michael. 2019. Was the Mahāparinirvāṇa-sūtra 大般涅槃經 T7 Translated by ‘Faxian’?: An Exercise in the Computer Assisted Assessment of Attributions in the Chinese Buddhist Canon. Hualin International Journal of Buddhist Studies 2: 229–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowan, Diana P. 1985. Reconsideration of an Unusual Ivory Diptych. Artibus Asiae 46: 251–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saiiki Bijutsuten = Tokyo Kokuritsu hakubutsukan, ed. 1991. Saiiki Bijutsuten: Doitsu, Turfan Tankentai 西域美術展:ドイツ・トゥルファン探検隊 [Exhibition of the Art of Silk Road: The German Turfan Expeditions]. Tokyo: Asahi Shinbunsha 東京朝日新聞社. [Google Scholar]

- Santoro, Arcangela. 2003. Gandhara and Kizil: The Buddha’s Life in the Stairs Cave. Rivista degli Studi Orientali 77: 115–33. [Google Scholar]

- Schlingloff, Dieter. 2000. Ajanta—Handbuch der Malereien/Handbook of the Paintings 1. Erzählende Wandmalereien/Narrative Wall-Paintings. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. [Google Scholar]

- Schlingloff, Dieter. 2013. Ajanta—Handbook of the Paintings 1. Narrative Wall-Paintings. New Delhi: IGNCA. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, Klaus T. 2010. Die Entzifferung der westtocharischen Überschriften zu einem Bilderzyklus des Buddhalebens in der „Treppenhöhle“ (Höhle 110) in Quizil/Interdisciplinary research on Central Asia: The decipherment of the West Tocharian captions of a cycle of mural paintings of the life of the Buddha in cave 110 in Quizil. In From Turfan to Ajanta: Festschrift for Dieter Schlingloff on the Occasion of his Eightieth Birthday. Edited by Eli Franco and Monika Zin. Lumbini: Lumbini International Research Institute, pp. 835–66. [Google Scholar]

- Seckel, Dietrich. 1976. Jenseits des Bildes—Anikonische Symbolik in der buddhistischen Kunst. Abhandlungen der Heidelberger Akademie der Wissenschaften: Philosophisch-historische Klasse, Jahrgang 1976, 2. Heidelberg: Abhandlung. [Google Scholar]

- Seckel, Dietrich, and Andreas Leisinger. 2004. Before and Beyond the Image. Aniconic Symbolism in Buddhist Art. Translated by Andreas Leisinger. Edited by Helmut Brinker and John Rosenfield. Zürich: Artibus Asiae Publishers, New Delhi: Agam Kala Prakashan, suppl. 45. [Google Scholar]

- Sivaramamurti, Calambur. 1974. L’Art en Inde. Paris: Mazenod. [Google Scholar]

- Soper, Alexander. 1965. A Buddhist Travelling Shrine in an International Style. East and West 15: 211–25. [Google Scholar]

- Spiro, Audrey. 2001. Hybrid Vigor: Memory, Mimesis, and the Matching of Meanings in Fifth-Century Buddhism. In Culture and Power in the Reconstitution of the Chinese Realm, 200–600. Edited by Scott Pearce, Audrey Spiro and Patricia Ebrey. Cambridge: Harvard University Asia Center, pp. 125–48. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, Aurel. 1921. Serindia: Detailed Report of Explorations in Central Asia and Westernmost China. 5 vols. London and Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stern, Philippe, and Mireille Benisti. 1952. Evolution du Stupa Figure dans les Sculptures D’Amaravati. Bulletin de la Societe des Etudes Indochinoises 27: 375–80. [Google Scholar]

- Verardi, Giovanni. 1999–2000. The Buddha-Elephant. In Silk Road Art aud Archaeology. = Papers in honour of Francine Tissot. Edited by Elizabeth Errington and Osmund Bopearachchi. Kamakura: The Institute of Silk Road Studies, vol. 6, pp. 69–74. [Google Scholar]

- Waldschmidt, Ernst. 1933. Die buddhistische Spätantike in Mittelasien. Ergebnisse der Kgl.-Preussischen Turfan-Expeditionen, VII, Neue Bildwerke III. Berlin: Reimer und Vohsen. [Google Scholar]

- Windisch, Ernst. 1908. Buddhas Geburt und die Lehre von der Seelenwanderung. Leipzig: Kessinger Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Yaldiz, Marianne. 1987. Archäologie und Kunstgeschichte Chinesisch-Zentralasiens (Xinjiang) = Handbuch der Orientalistik 7.3,2. Leiden: E.J. Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Yamabe, Nobuyoshi 山部能宜. 1999. The Sūtra on the Ocean-Like Samādhi of the Visualization of the Buddha: The Interfusion of the Chinese and Indian Cultures in Central Asia as Reflected in a Fifth Century Apocryphal Sūtra. Ph.D. dissertation, Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Wenru 阎文儒. 1955. Tan xiangya zaoxiang 谈象牙造像 [On a Statue in Ivory]. Wenwu cankao ziliao文物参考资料 Cultural Relics 10: 80–88, 137. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Bo 杨波. 2017. Qiuci shiku bihua zhong de pizhifo xingxiang kaobian 龟兹石窟壁画中的辟支佛形象考辨 Research on the Images of Pratyekabuddha in Kucha Caves. Xiyu yanjiu 西域研究 The Western Regions Studies 1: 76–86. [Google Scholar]

- Yun-Kang = 雲岡石窟: 西暦五世紀における中國北部佛教窟院の考古學的調査報告 Yun-Kang The Buddhist Cave-Temples of the Fifth Century A.D. in North China. 1951–1956. 16 vols. Mizuno, Seiichi 水野清一, and Toshio Nagahiro 長廣敏雄, eds. Kyoto: Jimbunkagaku Kenkyusho Kyoto University, Kyoto University Research Information Repository (KURENAI). Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/2433/139069 (accessed on 20 March 2023).

- Zhou, Bokan 周伯戡. 2000. <Da zhidu lun> lueyi chutan 《大智度論》略譯初探 A Preliminary Study of the Abbreviated Translationof the Da zhidu lun. Zhonghua foxue xuebao 中華佛學學報 The Journal of Chinese Buddhist Studies (JCBS) 13: 155–65. [Google Scholar]

- Zin, Monika. 2015. Nur Gandhara? Zu Motiven der klassischen Antike in Andhra (incl. Kanaganahalli). In Tribus, Jahrbuch des Linden-Museums. Heidelberg: Vowinckel, vol. 64, pp. 178–205. [Google Scholar]

- Zwalf, Wladimir. 1996. A Catalogue of the Gandhāra Sculpture in the British Museum. 2 vols. London: British Museum Publisher. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, F. The Wall Painting of “Siddhārtha Descending on the Elephant” in Kizil Cave 110. Religions 2023, 14, 677. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14050677

Wang F. The Wall Painting of “Siddhārtha Descending on the Elephant” in Kizil Cave 110. Religions. 2023; 14(5):677. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14050677

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Fang. 2023. "The Wall Painting of “Siddhārtha Descending on the Elephant” in Kizil Cave 110" Religions 14, no. 5: 677. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14050677

APA StyleWang, F. (2023). The Wall Painting of “Siddhārtha Descending on the Elephant” in Kizil Cave 110. Religions, 14(5), 677. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14050677